Public Law for Everyone

by Professor Mark Elliott

1,000 words / Parliamentary sovereignty

Since writing this post, I have written a longer piece examining the the constitutional implications of the UK’s membership of, and departure from, the European Union, with particular reference to the principle of parliamentary sovereignty. An overview of the paper can be found here ; the full text can be downloaded here .

On the surface, at least, parliamentary sovereignty — a phenomenon that applies to the UK, or Westminster, Parliament, but not to the UK’s devolved legislatures — is a simple concept. To paraphrase Dicey, Parliament has the legal authority to enact, amend or repeal any law, and no-one has the legal authority to stop it from doing so. But this notion is as extravagant as it is simple: it means, as Stephen famously put it, that a law directing the killing of all blue-eyed babies would be valid. The fact that such laws remain unenacted is thanks to “political constitutionalism” as opposed to “legal constitutionalism”: it is political, not legal, factors — including, one hopes, legislators’ own sense of morality — that operate as the restraining force.

It is often assumed that the sovereignty of Parliament follows from the absence in the United Kingdom of a written constitution, the existence of such constitutions generally being associated with legislatures that have only limited powers. Within such legal systems, the written constitution usually performs two functions (which are in truth flip sides of one coin) that rule out anything like parliamentary sovereignty. The constitution confers authority on the legislature; and the constitution restricts the legislature’s authority (by omitting to confer the power to do certain things). Within this type of constitutional framework, the legislature only has those (limited) powers that the constitution grants: and if the legislature attempts to make laws beyond the powers granted to it, then (often) courts can intervene by quashing unconstitutional legislation (or simply refusing to apply it, on the ground that it is not really “law”).

In the UK, however, in the absence of a written constitution, there is nothing to tell us what powers Parliament has : and there is equally nothing to tell us what powers (if any) Parliament lacks . It appears, therefore, that the constitution fails to perform the twin functions — of allocating and limiting authority — that usually result in something other than legislative sovereignty. But while this seems to follow from the absence of a written constitution, it does not necessarily follow. The fact that there is no written constitution performing the functions mentioned above does not automatically mean that there is no constitution performing those functions.

In other words, it is conceptually possible for an unwritten constitution to ascribe power to — and circumscribe the power of — the legislature. The constraining capacity of a constitution derives not from the fact that it is written; rather, it derives from the fact that it enjoys a legal status superior to that of regular law, with the result that enacted laws are valid only to the extent that they respect the terms of the legally superior constitution. The question then becomes whether — for all that it is unwritten — the UK’s constitution may enjoy the kind of legal superiority more readily associated with textual constitutions, such that it — like its written counterparts — may claim some sort of constraining force in relation to the legislature.

The principle of Parliamentary Sovereignty means neither more nor less than this, namely, that Parliament … has, under the English constitution, the right to make any law whatever; and, further, that no person or body is recognised by the law of England as having a right to override or set aside the legislation of Parliament. — Professor AV Dicey, An Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution

There is no definitive answer to this question; what evidence there is is circumstantial. The ability of Parliament to enact law — and its claim to unconstrained law-making capacity — is rooted in the constitutional settlement reached in the aftermath of the Glorious Revolution at the end of the 17th century. Unusually, however, that settlement was never cemented by means of being recorded in a superior constitutional text. It is for this reason that writers such as Wade argue that the sovereignty of Parliament is ultimately secured not by law, but by a “political fact”: a consensus that emerged in the wake of the Glorious Revolution and that remains in place unless and until it breaks down as a result of a “technical legal revolution”.

There is a certainly a good deal of evidence to suggest that that consensus — and so the sovereignty of Parliament — remains in place today; no judgment of a UK court specifically rejects the notion of parliamentary sovereignty. That said, there are dicta , perhaps most notably in Jackson v Attorney-General , that call into question the idea that Parliament has unlimited legislative power. There are, for instance, suggestions in that case that if Parliament were to attempt to remove the courts’ powers of judicial review, the courts might refuse to recognise such legislation as valid. This implies — as, perhaps paradoxically, Wade himself suggested — that judicial review is a “constitutional fundamental” that even Parliament cannot disturb.

However, it would be a very brave judge who actually went through with threats of the type made — or at least hinted at — in Jackson . Without a written constitution, there is no roadmap that tells us what would happen if a court were to refuse to apply an Act of Parliament: and it cannot be taken for granted — particularly if the legislation concerned were generally popular, albeit perhaps oppressive to a minority — that the courts would prevail. Nor, in the absence of a written constitution, do judges have the luxury of a text that identifies fundamental constitutional values and legitimises judicial protection of them. Judges who were to enforce such values over and above democratically enacted legislation would thus find themselves in a very exposed position.

It is unsurprising, therefore, that courts do not seek out conflict with Parliament, preferring instead to confer a degree of protection on fundamental constitutional values by interpreting legislation — in cases like Anisminic and Witham — consistently with them, rather than refusing to apply it on the ground that it infringes such values. This sort of interpretative approach, of course, must have its limits: if legislation is sufficiently explicit, then there is little, if any, room for interpretative manoeuvre. However, just as courts are not eager to provoke a constitutional crisis, so Parliament is not anxious to do so. As a result, both sides, for the most part, exercise a degree of self-restraint born of healthy concern as to how the other might react in the event of an excessive use of legislative or judicial power. It is this sort of constructive institutional tension — together with the restraining effect of democratic politics — that forms the context in which the practical significance of parliamentary sovereignty falls to be understood. It follows that even if we accept the Diceyan orthodoxy that Parliament possesses unlimited legislative power, this does not mean that Parliament is in a position to exercise the full width of that authority.

Further reading

- Elliott and Thomas, Public Law (OUP 2014), 3rd edition , pp 228–256

- Elliott, “Parliamentary sovereignty in a multidimensional constitution” (2013) Public Law For Everyone

- Wade, “The Basis of Legal Sovereignty” [1955] Cambridge Law Journal 172

- Jackson v Attorney-General [2005] UKHL 56

- Anisminic Ltd v Foreign Compensation Commission [1969] 2 AC 147

- R v Lord Chancellor, ex parte Witham [1998] QB 575

This post is part of my 1,000 words series . Other questions concerning parliamentary sovereignty — including the implications of membership of the European Union and the relationship between parliamentary sovereignty and the rule of law — are considered in other posts in the series.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Should Parliament’s legal sovereignty be understood as a statutory rule, common law rule, or political fact?

- by Lawprof Team

Model Essay

Introduction.

At the outset, it will be recognised that our understanding of Parliamentary Sovereignty (PS) may be governed by two considerations. Logical coherence of such understanding, as well as normative consequences which flow from the particular view one adopts. It is submitted that PS cannot be understood as a statutory rule – it is not a defensible logical position though there are certain illuminating elements relating to a “self-embracing” form of Sovereignty which are considered in turn when one engages with this debate.

On the other hand, understanding PS as a common law rule or a political fact are both logically defensible positions. This essay will argue that while understanding Parliament’s legal sovereignty as a political fact is useful in explaining the political ‘power-generative’ realities of constitutional change, it does not adequately account for the legal characteristics of the rule. Instead, as Loughlin argues, a proper understanding of the doctrine of Parliamentary sovereignty requires an appreciation of its intertwined political and legal aspects.

Statutory Rule

Lord Salmond’s argument offers a succinct summary of the flaws of viewing PS as a statutory rule. Were PS to be considered as such, it would be conferring Parliament authority on the basis of the very authority it was attempting to confer. The circularity of this logic does not lend itself well to intellectual honesty. A further implication which would flow from understanding PS as a statutory rule would be the implication that it could be removed at will by a Parliamentarian majority, albeit likely requiring express repeal, given the introduction of constitutional statutes by Laws LJ in Thoburn . This is a ludicrous concept, given the controversy raised in Factortame 2 regarding the subjugation of Parliament-made statute to EU law. However, this is not to say the analysis is devoid of any value. The outcome of the Factortame case, where Lord Bridge states that there was “nothing novel in any way to according supremacy to community law in areas which they apply”, and the subsequent issuing of injunctive relief for the Spanish Fishermen has been seen by academics such as Heuston and Jennings as a “manner and form” binding of sovereignty. Similarly, in the case of Jackson , the Parliaments Act 1911/49 were seen to create a new “manner and form” for Parliament to pass primary legislation without the House of Lord’s consent by suspending the upper House’s veto powers. Trethowan demonstrates the “manner and form” conception to its most extreme degree in a jurisdiction outside the UK – where NSW was legally bound by an antecedent Parliament in the Constitution Act 1902 to not abolish the legislative council without a referendum. However, these are generally moderate alterations to the doctrine, if they are to be accepted as such at all, and cannot be said to support a view of PS as a statutory rule – they merely aid us in understanding the minor “manner and form” alterations to its own sovereignty Parliament may make from time to time, if the Judiciary approves. The rule of judicial actors in shaping the doctrine through the common law iwll now be discussed.

Common Law Rule

Allan’s argument suggests that the understanding of Parliamentary Sovereignty as a common law rule stems from the fact that its nature and scope are questions to be resolved by the courts in contested and doubtful cases. Lord Steyn in Jackson explicitly states that PS is a “construct of the common law”. We have seen this through the development of the hierarchy of laws -Allan cites Laws LJ’s invention of the concept of the constitutional statute to affirm this view of Parliamentary Sovereignty and it’s requirement for “express words” in the context of repealing constitutional statutes. Sovereignty has thus been demonstrated to be qualified in a modest sense. The HS2 case has further demonstrated the court’s role. While strictly obiter given that the EU directive was not held to require scrutiny of the Parliamentary process, Lords Neuberger and Mance alluded to higher constitutional principles encased within Article 9 of the Bill of Rights which may take primacy over constitutional statute – in this case the ECA 1972. By this view, the constitutional nature of statute should not be taken to establish that it prevails over an established common law principle, the fundamentality of which may outstrip that of constitutional statute. This creation of a normative hierarchies of statute display a derogation from the Diceyan Orthodox view that all statutes be equal in measure and ultimate in authority.

Paul Craig further illuminates the courts’ role in determining Parliamentary Sovereignty in his commentary over the Factortame 2 case. Sharing Professor Allan’s belief, Paul Craig states that the legislative supremacy of Parliament is to be decided by the courts through normative arguments of legal principle, the content of which can and will vary across time. Craig asserts that there is is no a priori reason why Parliament must be regarded as legally omnipotent. On this view, this disapplication of an Act of Parliament in that case was justified by Lord Bridge’s argument of volition, along with the doctrine of the Supremacy of EU law established in cases such as Costa v Enel and Van Gend En Loos – without subjugation of national law, the Economic Union between countries would not be truly meaningful. On this view, a normative consequence which flows from understanding Parliamentary Sovereignty as a common law rule is that it must be justified through well reasoned normative and legal arguments.

This further reconciles obiter dicta comments in Jackson relating to the proposed total ouster in the Asylum and Immigration act – with Lord Hope stating that “Parliamentary Sovereignty is no longer, if it ever was, absolute”, and that instead, the “rule of law as enforced by the courts is the ultimate controlling factor on which our constitution is based”. Understanding PS as a common law rule has the advantage of accommodating the changing nature of this doctrine. However, it may not explain its origins. For that we must turn to the analysis of political fact.

Political Fact

The understanding of Parliamentary Sovereignty as a political fact is an argument advanced by Wade, where the explanation that disapplication of the Merchant and Shipping Act(MSA) in Factortame 2 has triggered a “constitutional revolution” triggered by the entry of the United Kingdom into the EU. Further, constitutional writers often refer to the principle of devolved autonomy when discussing the political constraints which the devolution settlements have placed on Parliament. Whether or not one agrees with this, the notion that political factors can affect HLA Hart’s rules of recognition pose a further question – can they create the initial rule of recognition? Applying elements of Wade’s reasoning, we may come to understand the origins of Parliamentary Sovereignty and track its evolution in the early stages.

In the 16th century, the statute of proclamations subjugated Parliament to the monarch, before Sir Edward Coke restored the primacy of Parliament-made statute through Proclamations, stating that Parliament instead of the monarch had the sole right to legislate. This was later followed by the Stuart Period and the English civil war, where there was turmoil over the King’s right to exercise tyranny through taxation of the people. Parliamentary Sovereignty thus arose The Bill of Rights then removed much of the royal prerogative and the monarch;s ability to disapply statute, with the Earl of Shaftesbury declaring that Parliament was the “Supreme and Absolute power which gave life to English Government”. Parliamentary Sovereignty thus has its origins through the political struggle of a people for self-determination.

However, it must be noted that the implication of such an understanding of Parliamentary Sovereignty makes it a relatively inflexible concept, and does not account for the development of the doctrine through the common law, in cases such as Thoburn, HS2 , Factortame and arguably Jackson . It would appear that a complete understanding of the doctrine of PS can only be achieved by a dualist one.

The Dualist Understanding of Parliamentary Sovereignty

The flexibility which the common law understanding of Parliamentary Sovereignty affords as well as its principled basis account for the challenges the doctrine has faced. However, this should be cemented by the political account, which offers a valuable exposition as to the origins of the doctrine as well as the values which underlie it’s existence. This makes for a more complete and wholesome understanding of this principle.

While brevity precludes further discussion, an additional dimension which critical academics would look to examine are the normative implications of understanding Parliamentary Sovereignty in a legalistic as opposed to a political doctrine – arguments of representative democracy, its validity and fundamental rights abound.

Now out: model 1st class 🏆 examination answers from Oxford

1 Introduction

This book is a collection of essays with four main themes. The first is criticism of the theory known as ‘common law constitutionalism’, which holds either that Parliament is not sovereign because its authority is subordinate to fundamental common law principles such as ‘the Rule of Law’, or that its sovereignty is a creature of judge-made common law, which the judges have authority to modify or repudiate (Chapters 2, 3, 4 and 10). The second theme is analysis of how, and to what extent, Parliament may abdicate, limit or regulate the exercise of its own legislative authority, which includes the proposal of a novel theory of ‘manner and form’ requirements for law-making (Chapters 5, 6 and 7). This theory, which involves a major revision of Dicey’s conception of sovereignty, and a repudiation of the doctrine of implied repeal, would enable Parliament to provide even stronger protection of human rights than is currently afforded by the Human Rights Act 1998 (UK) (‘the HRA’), without contradicting either its sovereignty or the principle of majoritarian democracy (Chapters 7 and 8). The third theme is a detailed account of the relationship between parliamentary sovereignty and statutory interpretation, which strongly defends the reality of legislative intentions, and argues that sensible interpretation and parliamentary sovereignty both depend on judges taking them into account (Chapters 9 and 10). The fourth is a demonstration of the compatibility of parliamentary sovereignty with recent constitutional developments, including the expansion of judicial review of administrative action under statute, the operation of the HRA and the European Communities Act 1972 (UK), and the growing recognition of ‘constitutional principles’ and perhaps even ‘constitutional statutes’ (Chapter 10). This demonstration draws on the novel theory of ‘manner and form’, and the account of statutory interpretation, developed in Chapters 7 and 9.

The English-speaking peoples are reluctant revolutionaries. When they do mount a revolution, they are loath to acknowledge – even to themselves – what they are doing. They manage to convince themselves, and try desperately to convince others, that they are protecting the ‘true’ constitution, properly understood, from unlawful subversion, and that their opponents, who wear the mantle of orthodoxy, are the real revolutionaries. 1 They appear certain that their cause is not only morally righteous, but also legally conservative, in that they are merely upholding traditional legal rights and liberties.

Today, a number of judges and legal academics in Britain and New Zealand are attempting a peaceful revolution, by incremental steps aimed at dismantling the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty, and replacing it with a new constitutional framework in which Parliament shares ultimate authority with the courts. They describe this as ‘common law constitutionalism’, ‘dual’ or ‘bi-polar’ sovereignty, or as a ‘collaborative enterprise’ in which the courts are in no sense subordinate to Parliament. 2 Or they claim that the true normative foundation of the constitution is a principle of ‘legality’, which (of course) it is ultimately the province of the courts, rather than Parliament, to interpret and enforce. 3 But they deny that there is anything revolutionary, or even unorthodox, in their attempts to establish this new framework. They claim to be defending the ‘true’ or ‘original’ constitution, ‘properly understood’, from misrepresentation and distortion. 4 And they sometimes accuse their adversaries, the defenders of parliamentary sovereignty, of being the true revolutionaries. 5

The fictions of the courts have in the hands of lawyers such as Coke served the cause both of justice and of freedom, and served it when it could have been defended by no other weapons … Nothing can be more pedantic, nothing more artificial, nothing more unhistorical, than the reasoning by which Coke induced or compelled James to forego the attempt to withdraw cases from the courts for his Majesty’s personal determination. But no achievement of sound argument, or stroke of enlightened statesmanship, ever established a rule more essential to the very existence of the constitution than the principle enforced by the obstinacy and the fallacies of the great Chief Justice … The idea of retrogressive progress is merely one form of the appeal to precedent. This appeal has made its appearance at every crisis in the history of England and … the peculiarity of all English efforts to extend the liberties of the country … [is] that these attempts at innovation have always assumed the form of an appeal to pre-existing rights. But the appeal to precedent is in the law courts merely a useful fiction by which judicial decision conceals its transformation into judicial legislation. 6

In an earlier book, I set out to refute various philosophical errors and dispel several historical myths concerning the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty. 7 Prominent among these errors and myths are the beliefs that the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty: (a) is a relatively recent development, no older than the eighteenth century; (b) supplanted an ancient ‘common law constitution’ that had previously limited Parliament’s authority; (c) is a creature of the common law that was made by the judges and can therefore be modified or even repudiated by them. But it is possible, as Ian Ward has observed, that even if I was right, ‘truth matters little in a politics of competing mythologies’. 8 I take him to mean that lawyers and judges who find the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty morally objectionable, and are committed to bringing about its demise, are unlikely to be either able or willing to assess objectively the historical evidence and jurisprudential analysis that I presented – or perhaps even to acknowledge their existence. The mythology of common law constitutionalism is indeed very difficult to dispel. Scholarly works continue to perpetuate it while ignoring the weighty arguments and evidence to the contrary. 9

The desire to clothe legal revolution in the trappings of legal orthodoxy is not, of course, peculiarly British. Constitutional debates reminiscent of those in Britain today took place in France between 1890 and the 1930s. Before 1890, the French legal system was firmly based on the principle of legislative sovereignty, which had been established during the French Revolution and the rule of Napoleon. But after 1890, leading public law scholars began to revive natural law ideas, arguing that the legislature was bound by an unwritten higher law, which the judges were capable of discerning and ought to enforce. According to a recent account, these neo-natural law ideas were ‘functionally equivalent to rule of law notions in Anglo-American legal theory’. 10 These scholars waged a persistent campaign to convince judges, first, ‘that they were juridically required to exercise … substantive judicial review’, and secondly, ‘that the judges had already begun doing so, but apparently did not yet know it’. 11 The basis of the second claim was that a number of judicial decisions supposedly made complete sense only if higher, unwritten constitutional principles were assumed to exist. As one of these scholars argued in 1923, the judges ‘without expressly admitting it, and perhaps without even admitting it to themselves, have opened the way to judicial review’. 12 This campaign was making headway until the publication of a book that explained how the American Supreme Court had stymied democratic social reform by reading laissez faire principles into its Constitution, and warned that French judges might follow suit. This book had an enormous impact, and routed the campaign in favour of judicially imposed, higher law principles. 13

The most obvious reading is that certain judges are staking out their position for future battles. They do fear that Parliament and governments cannot be trusted in all circumstances to refrain from passing legislation inconsistent with fundamental rights, the rule of law or democracy. When a case involving such ‘unconstitutional legislation’ arises they want to be in a position to strike it down without appearing to invent new doctrine on the spot. They want to be able to say that they are applying settled constitutional doctrine. Jackson may then be a useful precedent … Jackson may [also] be viewed as a shot across the government’s bows. 17

The claims of the dissenters could prove self-fulfilling if they are repeated so often that enough senior officials are persuaded to believe them. And this could happen even if these officials are persuaded for reasons that are erroneous (such as that common law constitutionalism was true all along). If that happens, original doubts about their correctness will be brushed aside as irrelevant, and the law books will be retrospectively rewritten. After revolution, as after war, history is written by the victors. If the legal revolution succeeds, it will not be acknowledged to have been a revolution. It will be depicted either as a judicial rediscovery of ‘hitherto latent’ restrictions on Parliament’s powers that the law always included, 22 or as the exercise of authority that the judges always had to continue the development of the ‘common law constitution’.

This book includes further efforts to resist the legal revolution sought by the common law constitutionalists. Chapter 2 presents historical and philosophical objections, and Chapters 3 and 4 respond to arguments based on the political ideal known as ‘the rule of law’. The first section of Chapter 10 is also relevant to this theme. I attempt to show that Parliament has been for centuries, and still is, sovereign in a legal sense; that this is not incompatible with the rule of law; and that its sovereignty is not a gift of the common law understood in the modern sense of judge-made law. It is a product of long-standing consensual practices that emerged from centuries-old political struggles, and it can only be modified if the consensus among senior legal officials changes. Furthermore, it ought not to be modified without the support of a broader consensus within the electorate. The recent Green Paper titled The Governance of Britain ends on the right note: constitutional change in Britain as significant as the adoption of an entrenched Bill of Rights or written Constitution requires ‘an inclusive process of national debate’, involving ‘extensive and wide consultation’ leading to ‘a broad consensus’. 23 Such changes should not, and indeed cannot, be brought about by the judiciary alone.

If radical change is to be brought about by consensus, legislation will be required. Chapters 5, 6 and 7 discuss problems relating to Parliament’s ability to abdicate or limit its sovereignty, or to regulate its exercise through the enactment of requirements as to the procedure or form of legislation. Chapter 5 reviews all the current theories of abdication and limitation, and advocates an alternative based on consensual change to the rules of recognition underlying legal systems. The theories of A.V. Dicey, W. Ivor Jennings, R.T.E. Latham, H.W.R. Wade and Peter Oliver are all subjected to criticism. Chapter 6 is a detailed account of the influential decision in Trethowan v. Attorney-General (NSW) , 24 which is often misunderstood and misapplied in discussions of ‘manner and form’. This account reveals the difference between the ‘manner and form’ and ‘reconstitution’ lines of reasoning that were first propounded in that case, and shows that much of the majority judges’ reasoning was dubious. Chapter 7 draws on the previous two chapters to propose a novel theory of Parliament’s power to regulate its own decision-making processes, by enacting mandatory requirements governing law-making procedures or the form of legislation. In passing, it discusses the somewhat different issues raised in Jackson v. Attorney-General , 25 which involved what is called in Australia an ‘alternative’ rather than a ‘restrictive’ legislative procedure. The novel theory of restrictive procedures that is proposed differs from the ‘new theory’ propounded by Jennings, Latham and R.F.V. Heuston, and from the neo-Diceyan theory of H.W.R. Wade. It rejects a key element of Dicey’s conception of legislative sovereignty, and the popular notion that the doctrine of implied repeal is essential to parliamentary sovereignty. Chapter 7 concludes with the possibly surprising suggestion that a judicially enforceable Bill of Rights could be made consistent with parliamentary sovereignty by including a broader version of the ‘override’ or ‘notwithstanding’ clause (s. 33) in the Canadian Charter of Rights, which enables Canadian parliaments to override most Charter rights. Chapter 8 examines this topic in more detail, analysing the relationship between the judicial protection of rights, legislative override, legislative supremacy and majoritarian democracy.

Chapter 9 is a detailed account of the relationship between parliamentary sovereignty and statutory interpretation, which argues that legislative intentions are both real and crucial to avoiding the absurd consequences of literalism. It also describes and criticises the alternative ‘constructivist’ theories of interpretation defended by Ronald Dworkin, Michael Moore and Trevor Allan. It acknowledges the frequent need for judicial creativity in interpretation, including the repair or rectification of statutes by ‘reading into’ them qualifications they need to achieve their purposes without damaging background principles that Parliament is committed to. The intentionalist account is further developed in Chapter 10, where it is shown to be crucial to the traditional justification of presumptions of statutory interpretation, such as that Parliament is presumed not to intend to infringe fundamental common law rights, and also crucial to the defence of parliamentary sovereignty against other criticisms.

Chapter 10 is a lengthy defence of parliamentary sovereignty against recent criticisms that it was never truly part of the British constitution, or is no longer part of it, or will soon be expunged from it. The Chapter begins with some historical discussion, and then considers at length the consequences of recent constitutional developments, including the expansion of judicial review of administrative action under statute, the operation of the European Communities Act 1972 (UK) and the HRA, and the growing recognition of ‘constitutional principles’ and possibly even ‘constitutional statutes’. It argues that none of these developments is, so far, incompatible with parliamentary sovereignty.

The once popular idea of legislative sovereignty has been in decline throughout the world for some time. ‘From France to South Africa to Israel, parliamentary sovereignty has faded away.’ 26 A dwindling number of political and constitutional theorists continue to resist the ‘rights revolution’ that is sweeping the globe, by refusing to accept that judicial enforcement of a constitutionally entrenched Bill of Rights is necessarily desirable. To be one of them can feel like King Cnut trying to hold back the tide.

This book does not directly address the policy questions raised by calls for constitutionally entrenched rights. For what it is worth, my opinion is that constitutional entrenchment might be highly desirable, or even essential, for the preservation of democracy, the rule of law and human rights in some countries, but not in others. In much of the world, a culture of entrenched corruption, populism, authoritarianism, or bitter religious, ethnic or class conflicts, may make judicially enforceable bills of rights desirable. Much depends on culture, social structure and political organisation.

I will not say much about this here, because the arguments are so well known. I regret the contemporary loss of faith in the old democratic ideal of government by ordinary people, elected to represent the opinions and interests of ordinary people. 27 According to this ideal, ordinary people have a right to participate on equal terms in the political decision-making that affects their lives as much as anyone else’s, and should be presumed to possess the intelligence, knowledge and virtue needed to do so. 28 Proponents of this ideal do not naively believe that such a method of government will never violate the rights of individuals or minority groups. But they do trust that, in appropriate political, social and cultural conditions, clear injustices will be relatively rare, and that in most cases, whether or not the law violates someone’s rights will be open to reasonable disagreement. They also trust that over time, the proportion of clear rights violations will diminish, and ‘that a people, in acting autonomously, will learn how to act rightly’. 29 Strong democrats hold that where the requirements of justice and human rights are the subject of reasonable disagreement, the opinion of a majority of the people or those elected to represent them, rather than that of a majority of some unelected elite, should prevail. On this view, the price that must be paid for giving judges power to correct the occasional clear injustice by overriding enacted laws, is that they must also be given power to overrule the democratic process in the much greater number of cases where there is reasonable disagreement and healthy debate. For strong democrats, this is too high a price.

What explains the loss of faith in the old democratic ideal? I am aware of possible ‘agency problems’: failures of elected representatives faithfully to represent the interests of their constituents. In many countries this is a major problem. But I suspect that in countries such as Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, the real reason for this loss of faith lies elsewhere. There, a substantial number of influential members of the highly educated, professional, upper-middle class have lost faith in the ability of their fellow citizens to form opinions about important matters of public policy in a sufficiently intelligent, well-informed, dispassionate, impartial and carefully reasoned manner. Even though the upper-middle class dominates the political process in any event, the force of public opinion still makes itself felt through the ballot box, and cannot be ignored by elected politicians no matter how enlightened and progressive they might be. Hence the desire to further diminish the influence of ‘public opinion’.

If I am right, the main attraction of judicial enforcement of constitutional rights in these countries is that it shifts power to people (judges) who are representative members of the highly educated, professional, upper-middle class, and whose superior education, intelligence, habits of thought, and professional ethos are thought more likely to produce enlightened decisions. I think it is reasonable to describe this as a return to the ancient principle of ‘mixed government’, by re-inserting an ‘aristocratic’ element into the political process to check the ignorance, prejudice and passion of the ‘mob’. By ‘aristocratic’, I mean an element supposedly distinguished by superior education, intellectual refinement, thoughtfulness and responsibility, rather than by heredity or inherited wealth.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

4 Parliamentary Sovereignty: Authority and Autonomy

- Published: July 2013

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Dicey's absolutist conception of parliamentary sovereignty should be rejected in favour of an account of legislative supremacy compatible with the rule of law. Conventional accounts of the ‘rule of recognition’, treating sovereignty as legal or political fact, are erroneous. We need not choose, therefore, between ‘continuing’ and ‘self-embracing’ accounts, which are only broad generalizations, extraneous to legal analysis. Legislative supremacy has a moral foundation within a general theory of British government: it authorizes only the legitimate use of state power. Matters of fundamental rights and the primacy of European law alike pose a challenge to absolutist conceptions of sovereignty. Goldworthy's legal positivist account is rejected. The important judgments in Jackson , Factortame , and Thoburn are closely considered. A protestant approach to interpretation, giving a critical role to personal conscience and commitment, has implications for the limits of sovereignty (limits implicit in Dworkin's theory of law, when correctly understood).

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Help and information

- Comparative

- Constitutional & Administrative

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Environment

- Equity & Trusts

- Competition

- Human Rights & Immigration

- Intellectual Property

- International Criminal

- International Environmental

- Private International

- Public International

- IT & Communications

- Jurisprudence & Philosophy of Law

- Legal Practice Course

- English Legal System (ELS)

- Legal Skills & Practice

- Medical & Healthcare

- Study & Revision

- Business and Government

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

The Changing Constitution (9th edn)

- Preface to the ninth edition

- Table of Cases

- Table of Primary Legislation

- Table of Secondary Legislation

- Table of European Legislation

- Table of International Treaties and Conventions

- List of Contributors

- 1. The Rule of Law

- 2. Parliamentary Sovereignty in a Changing Constitutional Landscape

- 3. Human Rights and the UK Constitution

- 4. Brexit and the UK Constitution

- 5. The Internationalization of Public Law and its Impact on the UK

- 6. Parliament: The Best of Times, the Worst of Times?

- 7. The Executive in Public Law

- 8. The Foundations of Justice

- 9. Devolution in Northern Ireland

- 10. Devolution in Scotland

- 11. The Welsh Way/Y Ffordd Gymreig

- 12. The Relationship between Parliament, the Executive and the Judiciary

- 13. Information: Public Access, Protecting Privacy and Surveillance

- 14. Federalism

- 15. The Democratic Case for a Written Constitution

p. 29 2. Parliamentary Sovereignty in a Changing Constitutional Landscape

- Mark Elliott

- https://doi.org/10.1093/he/9780198806363.003.0002

- Published in print: 24 July 2019

- Published online: September 2019

Parliamentary sovereignty is often presented as the central principle of the United Kingdom’s constitution. In this sense, it might be thought to be a constant: a fixed point onto which we can lock, even when the constitution is otherwise in a state of flux. That the constitution presently is—and has for some time been— in a state of flux is hard to dispute. Over the last half-century or so, a number of highly significant developments have occurred, including the UK’s joining— and now leaving—the European Union; the enactment of the Human Rights Act 1998; the devolution of legislative and administrative authority to new institutions in Belfast, Cardiff and Edinburgh; and the increasing prominence accorded by the courts to the common law as a repository of fundamental constitutional rights and values. Each of these developments raises important questions about the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty. The question might be thought of in terms of the doctrine’s capacity to withstand, or accommodate, developments that may, at least at first glance, appear to be in tension with it. Such an analysis seems to follow naturally if we are wedded to an orthodox, and perhaps simplistic, account of parliamentary sovereignty, according to which the concept is understood in unyielding and absolutist terms: as something that is brittle, and which must either stand or fall in the face of changing circumstances. Viewed from a different angle, however, the developments of recent years and decades might be perceived as an opportunity to think about parliamentary sovereignty in a different, and arguably more useful, way—by considering how the implications of this still-central concept are being shaped by the changing nature of the constitutional landscape within which it sits. That is the task with which this chapter is concerned.

- parliamentary sovereignty

- constitutional law

- European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018

- Scotland Act 1998

- Northern Ireland Act 1998

- Government of Wales Act 2006

- Human Rights Act 1998

- political and legal constitutionalism

- constitutional legislation

You do not currently have access to this chapter

Please sign in to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Law Trove. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 14 April 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.159]

- 81.177.182.159

Characters remaining 500 /500

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

Eshed cohen, introduction.

What is a constitution of a state? Normally, a constitution contains those sets of laws that establish a state; an array of laws that constitutes the state, in the sense that the state is established, exists, and operates within the parameters of those rules. Accordingly, section 1 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996, begins by declaring that South Africa ‘is one, sovereign democratic state’.

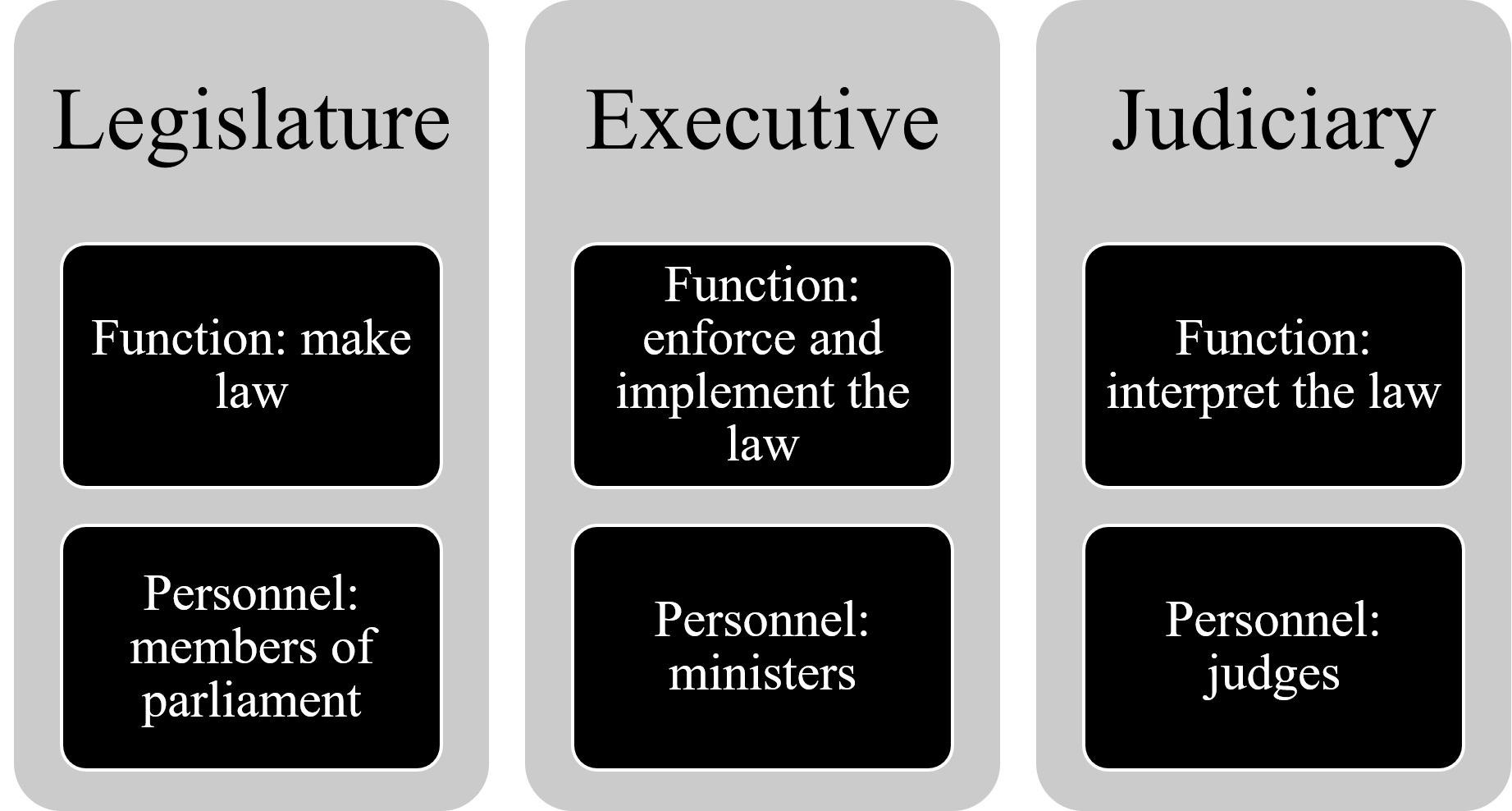

The fundamental rules constituting the state are those rules regulating the primary powers and duties of the state; the rules establishing arms and organs of the state; and the basic rules prescribing how a state interacts with persons in its jurisdiction through those arms and organs. So, constitutional law may not be limited to all the rules in a codified constitution. The laws relating to a state’s constitution may be contained in statute, common law, or even custom. In some countries, like religious states, constitutional law might even extend to theological texts. The ambit of constitutional law ultimately turns on what one considers to be rules that relate to the fundamental existence and functioning of a state.

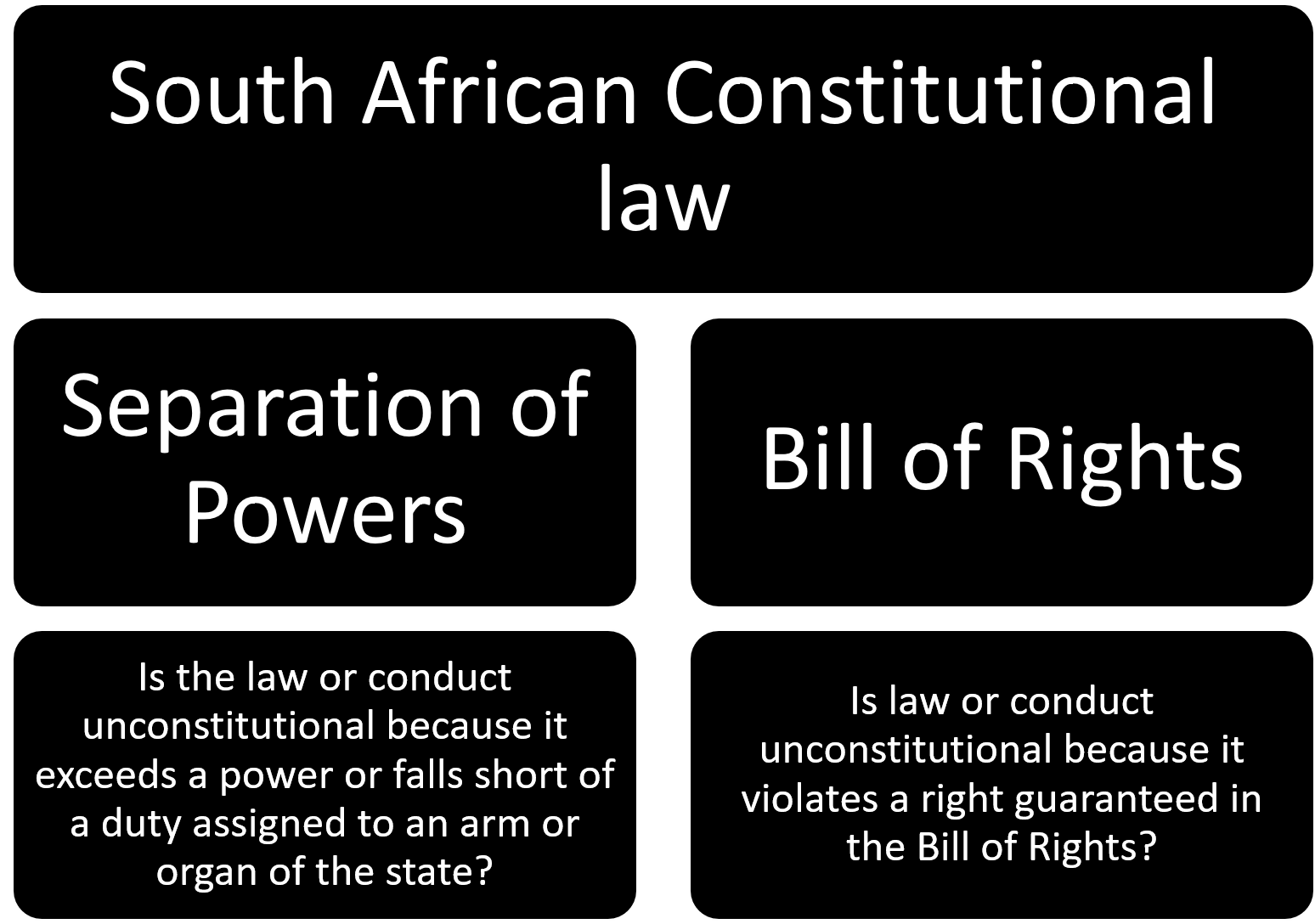

In the South African context, the ambit of constitutional law is generally seen as comprising two branches. First, there is the body of law that regulates how powers are separated between various arms and organs of state. Second, there is the body of law that grants persons within the jurisdiction of South Africa certain rights. These two arrays of rules are considered as the fundamental laws establishing the Republic of South Africa.

The primary reason for this bifocal conception of South African constitutional law is the structure of the Constitution. Chapter 2 of the Constitution, which is commonly referred to as the Bill of Rights, guarantees certain rights to various persons in South Africa. The rest of the Constitution is then largely devoted to creating arms and organs of state and then assigning powers and duties to those entities. An implication of this structure means that the constitutionality of law or conduct, roughly speaking, can be tested in two ways. First, law or conduct can be unconstitutional because it violates a right in the Bill of Rights. Secondly, law or conduct can be unconstitutional because it exceeds a power or falls short of a duty assigned to various state functionaries.

For example, the case of Doctors for Life concerned the constitutionality of the Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Amendment Act 38 of 2004 [1] . The Act gave women the right to abort a pregnancy. The Constitutional Court declared the Act to be unconstitutional, not because legalising abortion violated the right to life in the Bill of Rights, but because Parliament, in passing the law, had not fulfilled its constitutional duty to take reasonable steps to ensure public participation in the legislative process. The act was unconstitutional not for a rights-related reason, but for failing to perform its constitutional duty.

Constitutional law commentaries and curricula thus focus separately on the Bill of Rights and the separation of powers. This work roughly follows this structure. However, there is overlap between these two branches of constitutional law and this overlap is highlighted where relevant in this book.

The purpose of this chapter is first to introduce basic concepts of constitutional law that underpin South African constitutional law. Secondly, the chapter provides a schematic overview of the rest of the book.

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF CONSTITUTIONAL LAW

There are various principles and ideas invoked throughout this book and in most texts on constitutional law. These are: constitutional supremacy, separation of powers, the rule of law, democracy and transformative constitutionalism. Each of these is explained and discussed below.

- Constitutional supremacy

Section 1 of the Constitution provides that South Africa is a republic founded on the value of constitutional supremacy. Section 2 of the Constitution provides that the Constitution is ‘supreme law in the Republic; law or conduct inconsistent with it is invalid, and the obligations imposed by it must be fulfilled’. The rules in the Constitution thus trump all other rules contained in statutes, common law and custom. Any rule inconsistent with a constitutional rule is an invalid rule. Any conduct that contradicts the constitution, including failing to fulfil an obligation imposed by the Constitution, is similarly invalid.

The effect of section 2 is commonly referred to as constitutional supremacy, meaning that no rule or conduct can be inconsistent with a constitutional rule. If such an inconsistency arises, it is resolved by declaring the offending rule invalid to the extent that it contradicts a constitutional rule. Conversely stated, to be valid, all law and conduct must conform to the prescripts of the constitution. In this sense, the constitution is the ultimate authority for law-making and lawful conduct.

Constitutional supremacy has various implications for a state, state actors, and persons within a state’s jurisdiction, primarily that the rules in a constitution both establish and constrain the exercise of state power [2] . A state can only act in terms of its constitution. If it exceeds the bounds of the constitution its conduct is legally invalid.

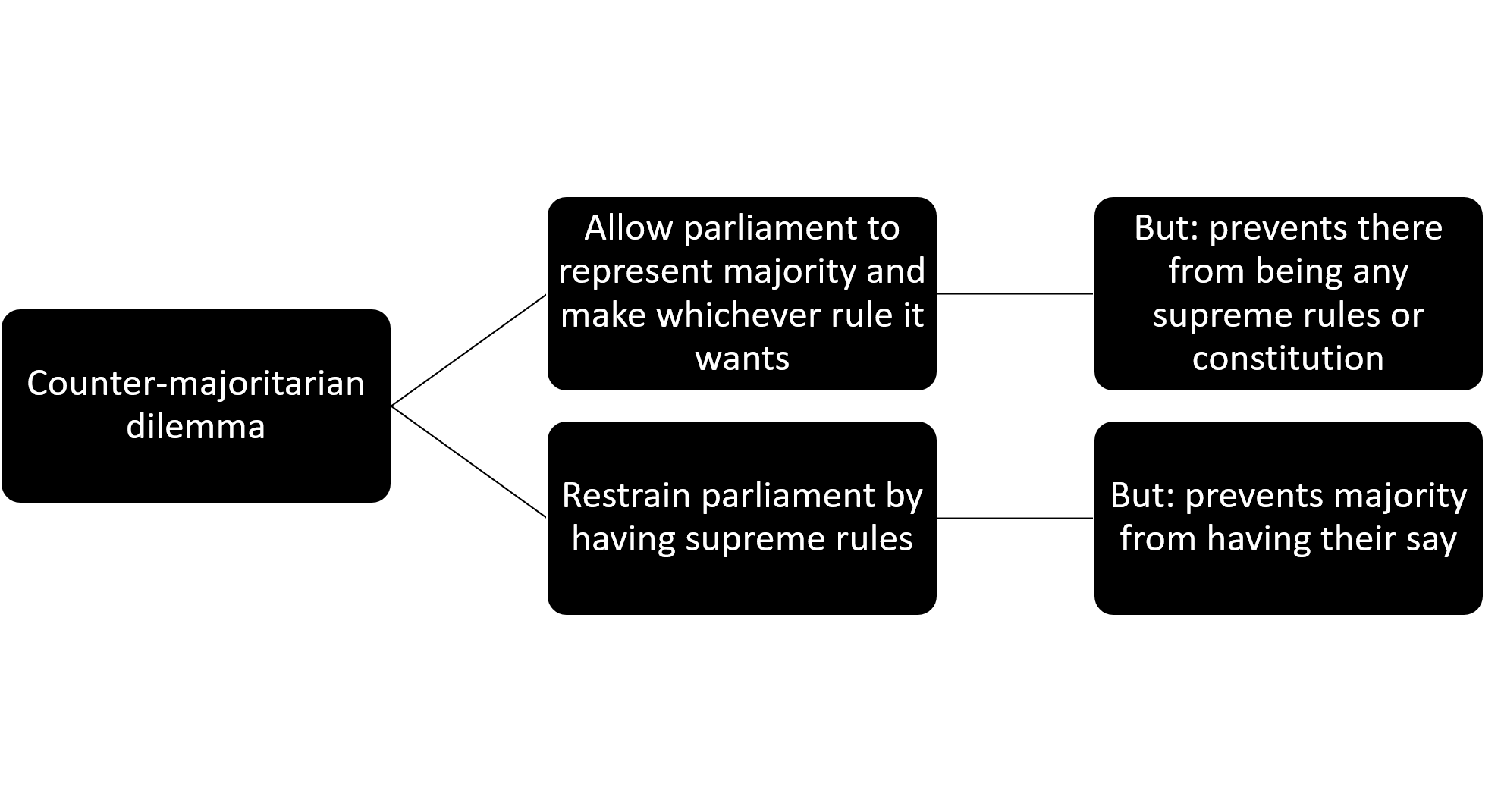

All state arms are bound by a supreme constitution. This includes the state legislature, the arm of government assigned with law-making powers. In a democratic state, this can give rise to what is commonly referred to as the counter-majoritarian dilemma; if a constitution limits the powers of a majority in parliament, then the will of the majority may be thwarted by a pre-existing constitutional rule. This runs counter to a basic premise of democracy that the majority of the people must determine the rules of a state. At the other extreme, if a majority of people can constantly overrule constitutional rules, then the constitution is hardly supreme. If the rules of the constitution could routinely be overridden by Acts of Parliament passed with a majority, the constitution would effectively be rendered meaningless. This could have implications for minority groups that are not represented by the majority in Parliament but whom a constitution seeks to protect.

The counter-majoritarian dilemma can be particularly acute where another branch of government (that may not be as representative of the majority as parliament) is given the final say over the meaning of the constitution, including the powers of the legislature. As explained briefly below and in Chapter 5 (The Judiciary), this is the position in South Africa, where the judiciary is given the final say over the meaning of the Constitution. In effect then, 11 justices of the Constitutional Court can tell the majority of South Africans that their wishes are invalid in law. The problem is squarely highlighted in Makwanyane , a case concerning the constitutionality of the death penalty. Chaskalson P held the following in relation to public opinion and the will of the majority of South Africans: