- Open access

- Published: 22 December 2022

Food safety practice and its associated factors among food handlers in food establishments of Mettu and Bedelle towns, Southwest Ethiopia, 2022

- Sanbato Tamiru 1 ,

- Kebebe Bidira 1 ,

- Tesema Moges 2 ,

- Milkias Dugasa 1 ,

- Bonsa Amsalu 1 &

- Wubishet Gezimu 1

BMC Nutrition volume 8 , Article number: 151 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

4970 Accesses

5 Citations

Metrics details

Food safety and hygiene are currently a global health concern, especially in unindustrialized countries, as a result of increasing food-borne diseases (FBDs) and accompanying deaths. It has continued to be a critical problem for people, food companies, and food control officials in developed and developing nations.

The objective of the study was to assess food safety practices and associated factors among food handlers in food establishments in Mettu and Bedelle towns, south-west Ethiopia, 2022.

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted from February to March 2022, among 450 randomly selected food handlers working in food and drink establishments in Mettu and Bedelle towns, Southwest Ethiopia. Data was collected using an interviewer-administered structured questionnaire. The data was coded and entered into Epi Data version 3.1 before being exported to SPSS version 20 for analysis. Both bivariate and multivariable logistic regression models were fitted. An adjusted odds ratio and a 95% confidence level were estimated to assess the significance of associations. A p -value of < 0.05 was considered sufficient to declare the statistical significance of variables in the final model.

A total of 450 food handlers participated in the study, making the response rate 99.3%. About 202 (44.9%) of respondents had poor practices in food safety. Lack of supervision (AOR = 6.2, 95% CI: 3.37, 11.39), absence of regular medical checkups (AOR = 1.98; 95% CI: 1.14, 3.43), lack of knowledge of food safety practices (AOR =2.32; 95% CI: 1.38, 3.89), availability of water storage equipment (AOR =0.37; CI: 0.21, 0.64), and unavailability of a refrigerator (AOR =0.24; 95% CI: 0.12) were factors significantly associated with food safety practices.

The level of poor food safety practices was remarkably high. Knowledge of food safety, medical checkups, service year as food handler, availability of water storage equipment, availability of refrigerator, and sanitary supervision were all significantly associated with food safety practice. Hence, great efforts are needed to improve food safety practices, and awareness should be created for food handlers on food safety.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Food safety is described as the circumstance and control required to ensure the safety, wholesomeness, and suitability of the food during its production and consumption. It is the primary public health concern for many countries, which is essential to prevent foodborne illness and enhance the well-being of humans [ 1 , 2 ]. Food safety and hygiene are currently a global health concern, particularly in developing countries, as a result of increasing food-borne diseases (FBDs) and accompanying deaths, and they also continue to be a critical problem in developed and developing nations for people, food companies, and food control officials [ 2 ].

Food-borne diseases (FBD) are associated with outbreaks, threaten global public health security, and have become an international concern as a growing public health issue [ 3 ]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), FBDs in developing nations are serious because of bad hygienic food handling methods, poor understanding, and the absence of infrastructure. This is the result of poor use of food handling and sanitation practices, inadequate food safety laws, weak regulatory systems, and a lack of financial resources [ 4 , 5 ].

Findings of different studies showed that there are relatively few food safety problems in some Asian countries like Indonesia, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia, which ranged from 10 to 19.31%, respectively [ 6 , 7 ]. But when we look at the findings of the study conducted in Malaysia, the magnitude of poor food safety practices was about 41.7% [ 1 ]. A study conducted in some parts of the country revealed that there is a high magnitude of food safety problems in food and drink establishment centers, ranging from 46.3 to 72.67% [ 3 , 8 , 9 ].

WHO disclosed that 1 in 10 individuals worldwide is sick from foodborne illnesses secondary to unsafe food practices and the use of contaminated foods [ 10 ]. Food safety practices are worse in developing countries, including Ethiopia; according to previous studies conducted in Addis Ababa and other areas of the country, less than half of food handlers have maintained satisfactory safety practices in handling food in the studied food establishments [ 3 , 8 , 9 ].

Foodborne diseases are prevalent in Ethiopia; the country’s annual incidence of foodborne illnesses ranged from 3.4 to 9.3% [ 3 ]. Food safety practices also have economic implications. The effects of food-related illness expenditures on hospital treatments are about US$ 110 billion annually in developing countries, which results in decreased production [ 11 ]. Several factors, like prevailing poor food handling and sanitation practices, inadequate food safety training, weak regulatory systems, a lack of financial resources, low educational status, and a lack of knowledge, have been identified as affecting food safety [ 12 ].

Efforts have been made globally by preparing a food safety guideline with the help of the World Health Organization. Similarly, in Ethiopia, significant work has been done with regards to food safety by preparing a national food safety policy and guidelines and assigning a regulatory department in the health office at different levels, though people are still suffering from morbidities and mortalities related to food-borne diseases. This is mainly attributed to food safety practices [ 3 , 13 ]. Only a few studies have been conducted in Ethiopia with regard to food safety practices. Hence, the purpose of this study was to assess food safety practices and associated factors among food handlers in the food establishment centers of Mettu and Bedelle towns.

Study design, period, and area

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted from February 21 to March 21, 2022, in Mettu and Bedelle towns. The two towns are located in the Oromia Regional State of southwest Ethiopia. Mettu is the capital of the Ilubabor Zone, and Bedelle is the capital of the Buno Bedelle Zone. Mettu and Bedelle towns are located about 600 and 480 km southwest of Addis Ababa, respectively. The two towns are home to different institutions and factories like Mettu University, Mettu Karl Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Bedelle General Hospital, Bedelle Brewery Factory that provide services for a large number people in the southwest region of the country. There were 188 food establishments and 1015 food handlers in the study area, according to data gathered from the trade and industry bureaus of the two towns.

Populations and eligibility criteria

All food handlers who worked in food and drink establishments in Mettu and Bedelle towns were considered the source population, whereas all selected food handlers who worked in selected food and drink establishments in the two towns were study participants in this study.

Food handlers working in preparation, cleaning, and service areas of food establishments at the time of the study were included in the study. However, food handlers who were not available during the data collection period and who could not give a response due to severe illness were excluded from the study.

Sample size determination and sampling procedure

The sample size was determined using a single population proportion formula:

Where Z = 1.96, the confidence limits of the survey result (value of Z at α/2 or critical value for normal distribution at 95% confidence interval).

p = 0.5 (50%), the population proportion of food safety practices from study conducted in Fiche town [ 5 ].

d = 0.05, the desired precision of the estimate

So the calculated sample size was, \(n={(1.96)}^2\frac{\left(0.5\ast 0.5\right)}{0.05^2}=384\)

Since the total number of food handlers in the study area was less than 10,000, we have utilized correction formula, that gives nf =288. After adding a 5% non-response rate and a design effect of 1.5, the final sample size of 453 was used for this study.

The list of existing food establishments and the number of food handlers currently working in food establishments were obtained from Mettu and Bedelle towns’ Trade and Industry Office. Then, food establishments for this study were randomly selected from a total list of food establishments. Next, study participants were proportionately allocated to each selected food establishment based on the number of food handlers. Then, an updated list of food handlers was taken from the manager or owner of the selected establishment. Finally, study participants were selected using a simple random method from each establishment.

Study variables

The dependent variable of this study was food safety practice, and the independent variable includes socio-demographic factors (educational level, age, gender, marital status, and work experience), institutional factors (training, supervision, and availability of guidelines for food safety), health-related factors (medical check-ups and sick leave during illness), knowledge-related factors (knowledge of methods to prevent contamination and knowledge of food safety practices), and sanitary facility-related factors (three-compartment dishwashing systems, refrigerators in the kitchen, and water supply).

Data collection tools and procedure

Data were collected using an interviewer-administered standardized questionnaire adapted and modified from previously published studies [ 3 , 8 , 9 , 13 ]]. The questionnaire was structured into six parts: socio-demographic parts with six questions, food safety knowledge with nine questions, basic sanitary facilities with seven questions, institutional factors with four questions, health-related with two questions, and food safety practice with twelve questions.

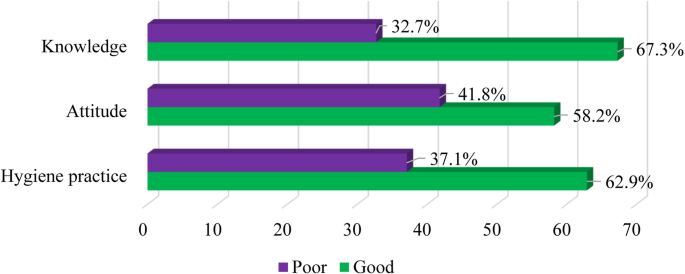

Food safety knowledge was assessed using nine closed-ended questions with two possible answers: “yes” or “no.” The questions mainly focus on the personal hygiene of food handlers, temperature control, cross-contamination, food storage, and equipment hygiene. In assessing knowledge, one score was given for every correct answer and zero score for incorrect answers or unanswered questions. Then, the responses to these questions were added together to generate a knowledge score. Food handlers who obtained a total score greater than the mean value were considered to have good food safety knowledge, and those who had scores less than the mean value were considered to have “poor food safety knowledge.”

Food safety practices were also assessed using 12 closed-ended questions with two possible answers: “yes” or “no.” One score was given for every standard practice and zero for every unsafe practice. Food handlers with a total score greater than the mean were considered to have “good food safety practices,” while those with a score less than the mean were considered to have “poor food safety practices.” The data was collected by three diploma nurses, and the overall data collection processes were supervised by one health officer after two days of training.

Data quality assurance

The quality of the data was ensured through all data collection tools and was translated into the local language and back-translated to English by language experts to ensure its consistency. Training of data collectors and supervisors was conducted to enable them to acquire the basic skills necessary for data collection and supervision, respectively. A pre-test was done on 5% of the sample in Gore town, and based on the results of the pre-test, necessary modifications were made. After data collection, the completeness of the data was checked by the principal investigator ahead of data entry. Incomplete and inconsistent questionnaires were excluded from the analysis.

Data analysis

The collected the data was curated according to the study objectives. The coded responses were entered into EpiData and exported to SPSS for analysis. A descriptive analysis was used to describe the percentages and number of distributions of the respondents by socio-demographic characteristics and other relevant variables in the study. A binary logistic regression analysis was performed on the independent variables and their proportions, and a crude odds ratio was computed against the outcome variable. The independent variables with a p -value less than 0.25 were entered into the multivariable logistic regression analysis to control for potential confounders and identify significant factors associated with outcome variables. Finally, a p -value of less than 0.05 at the 95% CI was used to claim statistical significance.

Ethics and approval processes

The ethical clearance letter was obtained from ethical committee of Mettu University, college of health science before conducting study. After the interviewer read and clearly explained the study’s benefits and risks, a written consent was obtained from the study participants. Then literate participants signed, whereas uneducated participants put their fingerprints on the consent form to shown their willingness to participate. Confidentiality of the data was maintained at all times.

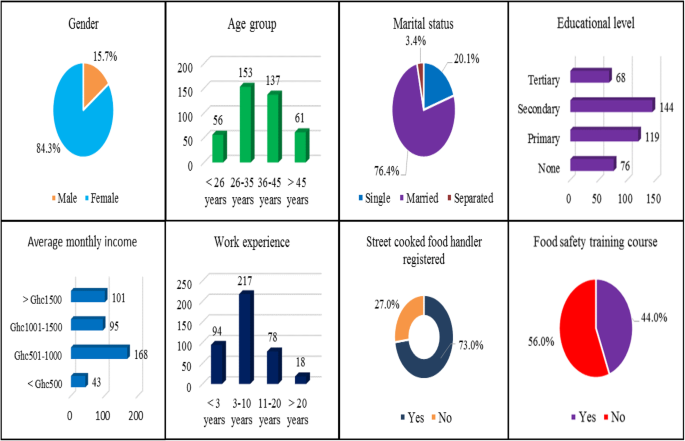

Socio-demographic characteristics of food handlers

In this study, a total of 450 food handlers participated out of a total of 453 with a response rate of 99.3%. The mean age of the participants was 29.3 years (SD = 5.28). The majority (54%) of food handlers were female. One hundred ninety-one (42.4%) of them attended secondary education, while only nine (2%) of them had least a higher education qualification. More than half (62.2%) of food handlers were married. Regarding service year as food handler, about 181 (40.2%) of respondents had worked for 2–4 years [Table 1 ].

Practice of food handlers on food safety

Among the 450 total food handlers, 417 (92.7%) of them were not checking the temperature of food. The majority, 333 (74%) of food handlers, did not wash their hands after sneezing. Two hundred and eleven (46.7%) participants did not wear hair covers. About 10.2% of food handlers did not trim their fingernails. Majority, 387(86%) of the participants, did wash their hands after touching unwrapped food, whereas 366 (81.3) of them wash their hands before touching cooked food. Moreover, 145 (32.2%) of participants did not use separate utensils for raw and cooked foods [Table 2 ].

Level of food safety practice

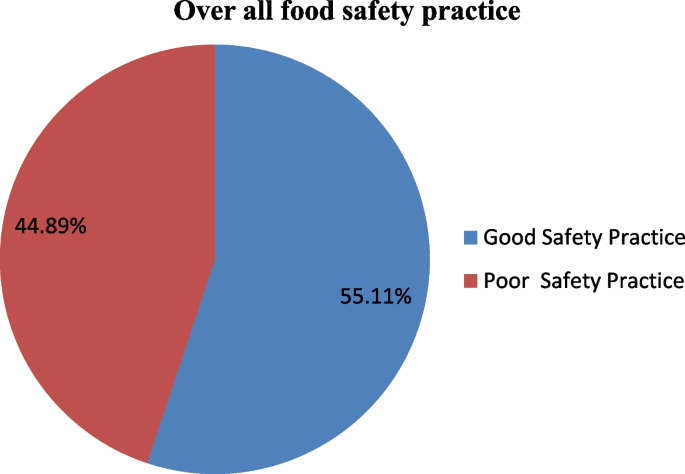

In general, out of all participants, 202 (44.89%) had poor food safety practices, while 248 (55.1%) had good food safety practices [Fig. 1 ].

Overall food safety practice of food handlers working in food and drink establishment in Mettu & Bedelle towns south west Ethiopia, 2022 ( n = 450)

Factors associated with food safety practice

In the bivariate analysis, variables like sanitary inspection, medical checkup, food safety knowledge, the presence of a refrigerator, the service year as a food handler, the presence of guidelines or guiding instructions, and the unavailability of water storage equipment were shown to be associated with the outcome variable. In the multivariable logistic analysis, the variables sanitary inspection (AOR = 6.2; 95% CI: 3.37, 11.39), medical checkup (AOR = 1.98; 95% CI: 1.14, 3.43), knowledge of food safety practices (AOR = 2.32; 95% CI: 1.38, 3.89), the presence of a refrigerator (AOR = 0.24; CI: 0.12, 0.45), and availability of water storage equipment (AOR = 0.37; CI: 0.12, 0.45) were found to be significantly associated with food safety practices.

The study revealed that food handlers with a poor level of knowledge were 2.32 times more likely to have poor food safety practices than those with a good level of knowledge (AOR = 2.32; 95% CI: 1.38, 3.89). The likelihood of having poor food safety practices among food handlers who did not have regular medical checkups was nearly two times higher than among food handlers who have regular medical checkups (AOR = 1.98; 95% CI: 1.14, 3.43). Moreover, poor food safety practice was 6.2 times higher among non-supervised food handlers as compared to their counterparts (AOR = 6.2; 95% CI: 3.37, 11.39) [Table 3 ].

Ensuring optimal food safety practices is still a major global challenge, particularly in developing countries like Ethiopia. This has in turn resulted in a high prevalence of FBD [ 3 ]. This study aimed to assess food safety practices and its associated factors among food handlers in food establishments of Mettu and Bedelle towns, Southwest Ethiopia.

The findings of the present study showed that 44.9% (CI: 40.29, 49.49) of participants had poor food safety practices. This finding is higher than studies conducted in Indonesia (10%) [ 2 ], Saudi Arabia (19.3%) [ 6 ], Nigeria (30.5%), [ 14 ], Arba Minch town, Southern Ethiopia (32.6%) [ 15 ], Dessie town, Northern Ethiopia (28%) [ 16 ], and Assosa Western Ethiopia [ 17 ]]. The variation might be due to differences in study settings and food handler’s socio-demographic profile. But it was lower than studies conducted in Fiche (50%) [ 3 ], and Gondar town (53.3%) [ 12 ]. The possible reason for discrepancies might be the difference in the study design, cutoff points, and year of study. However, the present finding was comparable with studies conducted in Debra Markos town (46.3%) [ 9 ], Woldia town, Northeast Ethiopia(46.5) [ 18 ], Dangila town, North West Ethiopia(47.5%) [ 19 ] and Batu town Central Ethiopia [ 20 ].

Regarding factors associated with poor food safety practice, this study revealed that; a lack of regular medical checkup was significantly associated with poor food safety practices. The likelihood of having poor food safety practices among food handlers who did not have regular medical checkups was nearly two times higher than that of those food handlers who have regular medical checkups. This finding was supported by a study conducted in Fiche, Gondar towns, and Dessie town [ 3 , 12 , 17 ]. This might be due to behavioral change following counseling given during a medical checkup.

The study revealed that sanitary inspection is significantly associated with food safety practice. Poor food safety practice was 6.2 times higher among non-supervised food handlers as compared to their counterparts. This finding is supported by a previous study conducted in Arba Minch town of Southern Ethiopia [ 15 ].

In the present study, knowledge of food safety was significantly associated with food safety practices. Food handlers with a poor level of food safety knowledge were 2.33 times more likely to have poor food safety practices than those with a good level of knowledge. This study is supported by cross-sectional studies conducted in Gondar city, Debra Marcos town, Dangila town, Northern Ethiopia, and Batu town, Central Ethiopia [ 9 , 12 , 19 , 20 ].

There was a significant association between food safety practices and sanitary inspection. The probability of having poor food safety practices was higher among food handlers who were not supervised than their counterparts. The present finding was supported by a study conducted in Assosa and Gondar city, Woldia town [ 12 , 17 , 18 ]. This might be due to the effect of advice and feedback given to supervised food handlers, managers, and the owners during an inspection.

The probability of having poor safety practices was 62.7% less likely among food handlers working in establishments having water storage equipment as compared to their counterparts. This might be due to easy access of water to cleansing. This finding was supported by a community based cross sectional study conducted in the Bole sub-city of Addis Ababa[ [ 8 ].

Moreover, the service year as a food handler was also significantly associated with food safety practices. The probability of having poor food safety practices among food handlers with 2–4 and 5–7 years of service was 96.8 and 88.5% less likely, respectively, as compared to those food handlers with a service year of less than 2 years. The finding was supported by a study conducted in Fiche and Debra Marcos town [ 3 , 9 ]. This might be due to the positive effect of adaptation to a specific working environment and sharing experience from coworkers.

Limitations of the study

The study was based on reported rather than observed practices related to food safety. Therefore, there was a risk that respondents may report what was expected of them but practice may be different. In addition, lack of universal consensus on the definition of good or poor practice was a challenge in the study. Furthermore, parasitic and microbiological laboratory investigations were not considered in this study.

The level of poor food safety practices was remarkably high in the study area. Almost all food handlers did not use thermometers to check the temperature of the food. More than one-third of them were not using separate utensils for raw and cooked foods. Nearly half of food handlers did not use hair covers, and three-fourths of them did not practice sanitizing or washing their hands after sneezing prior to touching foods. Generally, there is an increased risk of FBD in association with the identified poor food safety practices. Factors like sanitary inspection, medical checkup, food safety knowledge, availability of refrigerator, service year as food handlers, and availability of water storage were identified as having significant associations with the identified poor level of food safety practice. Therefore, there is need to invest much more in food safety practices, and special emphasis should be given to food safety in order to reduce the risk of FBD and ensure optimal food safety practices.

Recommendation

To improve food safety practices, all concerned bodies should play their roles. Food handlers should have regular medical checkups, maintain good hygiene, try to improve their knowledge and practice of food safety, and play a crucial role in ensuring good food safety practices. Food handlers should also use separate utensils for raw and cooked foods to reduce cross-contamination. Food establishment owners should avail themselves of equipment like refrigerators and water storage that can help ensure food safety by preventing spoilage and contamination.

Healthcare professionals and food professionals in collaboration need to conduct on-site supervision, inspect the hygiene of food handlers, and observe the way they are working towards food safety practices. They should conduct strict sanitary supervision on a regular basis and take timely corrective action (reward compliant food handler or constrain non-compliant handlers). In addition, they need to arrange for regular medical checkup of food handlers in collaboration with nearby medical facilities.

The trade and industry office should work in collaboration with health office and take food safety practices into consideration during the renewal of licenses of establishments, and the government or policy makers should enforce the implementation of HACCP as guiding instructions in all establishments as a mandatory requirement. Based on current findings, future researchers can conduct detailed investigations that are supported by microbial analysis and try to show a new approach to improving food safety practice.

Ethics statements

The study was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was conducted after getting ethical approval and clearance from the institutional review board (IRB) of Mettu University. A supportive letter was taken from Mettu University and submitted to each hospital, and permission was obtained from each hospital. Participation was completely voluntary, with no economic or other motivation, and informed consent was obtained from the study participants. All participants were informed of the study’s purpose and given the right to respond fully or partially to the questionnaire. They also had the right to withdraw at any time. Furthermore, Participants who agreed to participate in the study were asked to sign informed consent forms. The privacy and identity of participants were protected, and participants’ confidentiality was also assured by omitting their names from the informed consent form.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All the data generated or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abd Lataf Dora-Liyana NA, Mahyudin MR, Ismail-Fitry AA-Z, Rasiyuddin H. Food safety and hygiene knowledge, attitude and practices among food handlers at boarding schools in the northern region of Malaysia. Soc Sci. 2018;8(17):238–66.

Google Scholar

Organization WH. WHO estimates of the global burden of foodborne diseases: foodborne disease burden epidemiology reference group 2007-2015: World Health Organization; 2015.

Teferi SC, Sebsibe I, Adibaru B. Food safety practices and associated factors among food handlers of Fiche Town, North Shewa Zone, Ethiopia. Journal of environmental and public health. 2021;2021:6158769. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6158769 .

Article Google Scholar

Borchers A, Teuber SS, Keen CL, Gershwin ME. Food safety. Clinical reviews in allergy & immunology. 2010;39(2):95–141.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Grace D. Food safety in developing countries: An overview. Hemel Hempstead, UK: Evidence on Demand . 2015; Available from https://hdl.handle.net/10568/68720 .

Ayaz WO, Priyadarshini A, Jaiswal AK. Food safety knowledge and practices among Saudi mothers. Foods. 2018;7(12):193.

Lestantyo D, Husodo AH, Iravati S, Shaluhiyah Z. Safe food handling knowledge, attitude and practice of food handlers in hospital kitchen. Int J Public Health Sci. 2017;6(4):324–30.

Abdi AM, Amano A, Abrahim A, Getahun M, Ababor S, Kumie A. Food hygiene practices and associated factors among food handlers working in food establishments in the Bole Sub City, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2020;13:1861.

Alemayehu T, Aderaw Z, Giza M, Diress G. Food safety knowledge, handling practices and associated factors among food handlers working in food establishments in Debre Markos Town, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020: institution-based cross-sectional study. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021;14:1155.

Reta MA. Lemma MT. Lemlem GA. Food handling practice and associated factors among food handlers working in food establishments in Woldia town, Northeast Ethiopia: Gemeda AA; 2020.

Yenealem DG, Yallew WW, Abdulmajid S. Food safety practice and associated factors among meat handlers in Gondar town: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Environmental and Public Health. 2020;2020:7421745.

Azanaw J, Gebrehiwot M, Dagne H. Factors associated with food safety practices among food handlers: facility-based cross-sectional study. BMC Research Notes. 2019;12(1):1–6.

Chekol FA, Melak MF, Belew AK, Zeleke EG. Food handling practice and associated factors among food handlers in public food establishments, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Research Notes. 2019;12(1):1–7.

Iwu AC, Uwakwe KA, Duru CB, Diwe KC, Chineke HN, Merenu IA, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practices of food hygiene among food vendors in Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria. Occup Dis and Environ Med. 2017;5(01):11.

Legesse D, Tilahun M, Agedew E, Haftu D. Food handling practices and associated factors among food handlers in arba minch town public food establishments in Gamo Gofa Zone. South Ethiop Epidemiol (Sunnyvale). 2017;7(302):2161–1165.

Adane M, Teka B, Gismu Y, Halefom G, Ademe M. Food hygiene and safety measures among food handlers in street food shops and food establishments of Dessie town, Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. PloS one. 2018;13(5):e0196919.

W. AMaK. Food safety knowledge, Handling Practice and Associated Factors among Food Handlers of Hotels/Restaurants in Asosa Town, North Western Ethiopia. J Public Health Epidemiol. 2018;4(2):1051.

Reta MA, Lemma MT, Gemeda AA, Lemlem GA. Food handling practices and associated factors among food handlers working in public food and drink service establishments in Woldia town, Northeast Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2021:40.

Tessema AG, Gelaye KA, Chercos DH. Factors affecting food handling Practices among food handlers of Dangila town food and drink establishments, North West Ethiopia. BMC public Health. 2014;14(1):1–5.

Abe S, Arero G. Food handler’s safety practices and related factors in the public food establishments in Batu Town, Central Oromia. Ethiopia. Health. 2021;2(1):1–8.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank Mettu University for financial support. Again, our sincere appreciation goes to study participants, data collectors, and supervisors. Moreover, we would like to thank the Mettu and Bedelle towns’ trade and industry offices for provision of background information about the study population.

This research was funded by Mettu University with grant number of Meu/2021/210.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Nursing, Mettu University, Mettu, Ethiopia

Sanbato Tamiru, Kebebe Bidira, Milkias Dugasa, Bonsa Amsalu & Wubishet Gezimu

Department of Public Health, Mettu University, Mettu, Ethiopia

Tesema Moges

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

ST, KB, and TM participated in conceptualization of the study, methods, supervision, analysis, investigation, software, and writing of the first and final draft of the manuscript. MD, BA, and WG participated in the study methods, data curation, resource acquisition, and writing the final manuscript. Finally, all authors approved the last version of the manuscript to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all parts of the work.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sanbato Tamiru .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Mettu University. All methods were conducted in accordance with the code of ethics outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. After the interviewer read and clearly explained the study’s benefits and risks, a written consent was obtained from the study participants. Then literate participants signed, whereas uneducated participants put their fingerprints on the consent form to shown their willingness to participate. Confidentiality of the data was maintained at all times.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Additional information, publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1..

Annexe-1 Questionnaires and Consent forme.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Tamiru, S., Bidira, K., Moges, T. et al. Food safety practice and its associated factors among food handlers in food establishments of Mettu and Bedelle towns, Southwest Ethiopia, 2022. BMC Nutr 8 , 151 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-022-00651-3

Download citation

Received : 07 September 2022

Accepted : 15 December 2022

Published : 22 December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-022-00651-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Food safety

- Food handlers

BMC Nutrition

ISSN: 2055-0928

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open supplemental data

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Systematic review article, systematic review on food safety and supply chain risk assessment post pandemic: malaysian perspective.

- 1 Faculty of Applied Sciences, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Shah Alam, Malaysia

- 2 Department of Nutrition, Faculty of Publlic Health, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia

The novel coronavirus disease 2019, or COVID-19, is a recent disease that has struck the entire world. This review is conducted to study the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic to food safety as well as the food supply chain. The pandemic has caused various changes around the world as numerous countries and governments have implemented lockdowns and restrictions to help curb the rising cases due to COVID-19. However, these restrictions have impacted many aspects of everyday life, including the economic sectors such as the food industry. An overview of the current COVID-19 situation in Malaysia was discussed in this review along with its implication on food safety and food supply chain. This is followed by a discussion on the definition of food safety, the impact of the pandemic to food safety, as well as the steps to be taken to ensure food safety. Hygiene of food handlers, complete vaccination requirement, kitchen sanitation and strict standard operating procedures (SOPs) should be in place to ensure the safety of food products, either in food industries or small scale business. Additionally, the aspect of the food supply chain was also discussed, including the definition of the food supply chain and the impact of COVID-19 to the food supply chain. Travel restriction and lack of manpower had impacted the usual operation and production activities. Lack of customers and financial difficulties to sustain business operational costs had even resulted in business closure. As a conclusion, this article provides insight into crucial factors that need to be considered to effectively contain COVID-19 cases and highlights the precaution methods to be taken through continuous monitoring and implementation by Malaysian government.

Introduction

Recently, the entire world has been plagued with the sudden appearance of a new disease commonly known as COVID-19 that was brought about by the severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), ( Olaimat et al., 2020 ). On the 11th of March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) has declared the COVID-19 outbreak as a global pandemic as the number of cases worldwide rose to a concerning amount, with an expected increase in the number of cases in the coming months ( Cucinotta and Vanelli, 2020 ). According to World Health Organization (2020) , the new strain of the coronavirus disease was first identified in a cluster of pneumonia patients in Wuhan, China where the Chinese authorities later confirmed to be the cause of the pneumonia. COVID-19 is a respiratory illness characterized by symptoms such as fatigue, dry cough, fever, as well as lymphopenia ( Cucinotta and Vanelli, 2020 ).

This recent pandemic has brought about many changes around the world as numerous countries have implemented various lockdowns and the closure of many economic sectors in order to curb the number of rising COVID-19 cases due to the spread of the infection among the citizens. During these lockdowns, essential services were allowed to operate on strict standard operating procedures (SOPs). As a result, a new norm has been introduced where social and physical distancing must always be adhered to with masks to be worn at all times while being in public areas, as well as the prioritization of hygiene and sanitation. This pandemic has affected many aspects of day-to-day life, including social life, as well as many economic sectors. Rozaki (2020) found that many companies and businesses, including the agricultural practices and food industries have been affected by the economic uncertainty since the start of the pandemic. This study highlights the current issue of the COVID-19 pandemic that has affected the food industry, mainly in the aspect of food safety and the food supply chain in Malaysia. Due to COVID-19, many sectors in the economy were affected as companies have been forced to close down or took strict restrictions on their manufacturing and production as required by the health guidelines set by the government and authorizing bodies such as the WHO ( Rashid et al., 2021 ). Due to these restrictions, most companies had to cut down and minimize on the production and manufacturing of their products, which has caused shortages and delays of a particular product. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to review the impact and threats of the COVID-19 pandemic to food safety as well as to the food supply chain in Malaysia. Additionally, precaution and solution taken by the government were also discussed in order to provide an insight as a form of improvement to the current situation while managing the pandemic.

Literature Review

Overview of the covid-19 situation.

The recent COVID-19 pandemic has affected many countries in the world. As cases continued to rise, more and more countries have implemented lockdowns and restrictions. In China, where the first reported cases of COVID-19 originated, the Chinese government had enacted control measures which was described as “the strictest control measures since the founding of the People's Republic of China” ( Min et al., 2020 ). These measures include suspension of intra-city public transport, banning of public gatherings, and the shutdown of entertainment outlets. Additionally, restrictions had also been enforced in other countries such as the United Kingdom, where a lockdown that has restricted non-essential public gatherings, closure of businesses and educational institutions, and an order to stay at home aside for essential tasks and exercise was imposed ( Choi et al., 2020 ). In South East Asia, countries such as the Philippines have also implemented control measures which had included restrictions such as curfews, travel restrictions and check-points, as well as the indefinite suspension of business and education activities ( Tee et al., 2020 ). Globally, the government agencies have tried imposing restriction and control measures in order to closely monitor and manage the number of COVID-19 cases within each country. Nowadays, these restrictions are analyzed according to the state of each country and re-opening of other sub-economic sector were taken into consideration. However, tight SOPs are still in place as the pandemic is still far from being over globally which has eventually affected the food purchasing and consumption behavior ( Li et al., 2022 ).

In Malaysia, the first positive COVID-19 case was identified on the 25th of January 2020, and within 6 days, a total of eight positive cases were then reported, all of which were imported cases from Wuhan, China ( Shah et al., 2020 ). Furthermore, on 17th of March 2020, Malaysia recorded its first confirmed death ( Koh et al., 2020 ). Subsequently, the number of positive cases recorded skyrocketed following a religious mass gathering which has also included international participants from India, Brunei, Thailand, South Korea, China, and Japan ( Che Mat et al., 2020 ). Minhat and Shahar (2020) have expressed that the rapid transmission in positive cases was predicted to have been caused by exported cases from other countries. Following the continual increase in the number of cases in Malaysia from 99 positive to 200 positive in less than a week ( Shah et al., 2020 ), the government of Malaysia has implemented the Movement Control Order (MCO) on the 18th of March 2020. The MCO implemented has required all businesses to underwent a close down, with the exception of those that provide essential services and items ( Tang, 2020 ). Consequently, most businesses were forced to halt their activities as a form of compliance to the new MCO implemented by the government. Some of the restrictions during MCO include social distancing guidelines implemented in public places, limited operating hours, travel restrictions which have been further enforced by road blocks all over the country, in addition to the limitation of movement of a 10-km travel radius for all citizens ( Tang, 2020 ). However, even with the implementation of the MCO, after 1.5 years, Malaysia is seen still struggling to lower the number of cases among its population due to emerging new variants being transmitted.

These control measures had affected many walks of life, from workers, business owners, students, as well as children. Social life, education system and non-essential businesses have been placed on a halt. These restrictions, although implemented to stop the rising cases of COVID-19, have also impacted many economic sectors. While many companies were able to keep their businesses going by allowing their employees to work from home, the same cannot be applied for most food industries as many food companies require their workers to work hands-on with the product, especially for smaller businesses. Therefore, COVID-19 has caused some effects to the food industry, such as impacting food safety as well as the food supply chain, with similar impact found in over 16 countries. Hence, managing the whole system during a severe pandemic is utterly crucial ( Djekic et al., 2021 ).

Selection of Articles

In this study, the systematic review of articles was searched and selected from three databases (Science Direct, Scopus and Google Scholar). The literature search was conducted from Oct 2020 to September 2021. The search terms used were “food safety” and “food supply chain” under the (Article title, Abstracts, Keywords). In addition, the term “COVID-19” was used under the [Search within results] to be specific. About 1698 articles were identified through the database search and an additional 12 articles were identified (including governmental reports and newspaper articles) as indicated in Supplementary Figure 1 . Thorough screening was conducted to eliminate bias and subsequently, eligible literature were included in this study so that an overview of the food safety and supply chain during and post pandemic situations in Malaysia were able to be reflected in this study.

COVID-19 and Food Safety

What is food safety.

Food safety is a very important aspect in the food industry. According to Uçar et al. (2016 ), food safety is described as the preparation of food that shall not cause any harm to the consumer when it is eaten according to its intended use. Moreover, the Australian Institute of Food Safety (2019) describes food safety as the handling, preparation, and storage of food which can best lower the risk of sickness caused by foodborne illnesses. Food related diseases caused by foodborne pathogens can be very dangerous, and even fatal, therefore, food safety is a crucial aspect during food preparation to avoid any undesirable consequences. According to Uçar et al. (2016 ) there are a few factors which affects food safety: food hygiene, personal hygiene of food handlers, and kitchen sanitation, as shown in Supplementary Figure 2 . Previously, the responses of food safety system and management during pandemic in over 16 countries indicated that staff awareness and hygiene were the most important attributes that needed to be enforced in food industries ( Djekic et al., 2021 ).

Not only is food safety important to protect the consumers directly from foodborne diseases, but it is also significant as the consumption of safe and nutritious food will help maintain good health and well-being. Uddin et al. (2020) stated that the consumption of nutritious and safe foods helps to generate body immunity, thus, it also helps in fighting against diseases such as COVID-19. Additionally, a proper diet can guarantee that the body is strong enough to fight the virus. A healthy body and immunity are especially important during this pandemic where a sick or unhealthy person may be more susceptible to fall victim to COVID-19 as compared to a healthy person. Furthermore, it has been reported that the food consumption pattern during the pandemic has changed along with limited physical activities which could affect health condition in the long term ( Mahar et al., 2021 ). However, alongside the intake of healthy and nutritious foods in the diet, other measures such as food safety management and the good food practices are also necessary in combating the virus ( Aman and Masood, 2020 ). Thus, food safety should not be taken lightly during this pandemic. In fact, a huge shift of consumer perception toward food safety during the pandemic has influenced the purchasing power ( Thomas and Feng, 2021 ).

Impact of COVID-19 to Food Safety

Early on at the start of the pandemic, many food consumers have been concerned with the safety of their food as there was not much well-known information about COVID-19 and its transmission via food products. There were concerns of the virus being transmitted through food products as well as by the packaging of the food itself, which has caused many companies to enforce stricter hygiene rules in the manufacturing and production of their products. In this case, sanitation and sanitization is vital to ensure food safety. Sanitation is the utmost important criteria for hygienic condition so that the whole food preparation, handling area, amongst others, is in a clean environment. Additionally, during this pandemic outbreak, another step such as sanitization is needed to ensure that the surface is free from any kind of microbes and viruses that could potentially pose a threat to human health.

As more research was conducted, it was revealed that up until now, there was no study which had reported on the spread of COVID-19 through food products and the human digestive system ( Duda-Chodak et al., 2020 ; Olaimat et al., 2020 ). Food handlers in US practiced frequent hand-washing to eliminate the possibilities of contracting COVID-19 from food items ( Thomas and Feng, 2021 ). The World Health Organization (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), as well as the United States Food and Drug Administration (US-FDA) has advised that COVID-19 is not transmitted by the consumption of food contaminated by the virus ( Uddin et al., 2020 ). Moreover, Cable et al. (2020) reported that there was no evidence which has suggested that SARS-CoV-2, the virus causing COVID-19, is a foodborne virus, based on the conclusion brought about by the French Agency for Food, Environmental, and Occupational Health and Safety. Cable et al. (2020) has continued to state that, SARS-CoV-2 should be able to be inactivated during cooking as well as under normal pasteurization conditions, based on research conducted on other coronaviruses. This was also in agreement with the study conducted by Jawed et al. (2020) where high temperature heating of over 70°C has been found to inactivate viruses, including the Coronavirus. Thus, it is important for handlers to maintain good food safety etiquette, like cooking foods until the correct temperature was achieved in making sure that the food is safe for consumption. On the other hand, Cook and Richards (2013) has stated that even cooked foods may transmit viral diseases, if they come into contact with other contaminated foods or surfaces such as food that has been handled by a person with contaminated hands or coming into contact with food items that have previously been contaminated during processing or preparation. In the study, it has been further illustrated that viral droplets are typically considered heavy when they are more than 5 μm in size, resulting in a need for a space to land which could be any object, packaging or surfaces that in turn, could be the possible mode of transmission. Meanwhile, when the viral droplets are <5 μm in size, corona virus could be circulated in the air ( Cook, 2020 ).

Therefore, food safety is still a concern as this does not rule out the possibility of contamination through other means, such as from person-to-person, or from person-to-object. In light of recent events, food-related companies have faced even more challenges in maintaining food safety. Not only that they have been responsible in ensuring that their products were safe and free from foodborne pathogens, these companies must now also ensure that they are not exposing their employees and customers to COVID-19 ( Jawed et al., 2020 ). Hence, maintaining food safety among food handlers is still important and should not be taken lightly in food industries.

As person-to-person transmission is the main mode of transmission for COVID-19, it is of the upmost importance that safety and hygiene guidelines are implemented and enforced in food industries. For example, an infected person who does not follow social distancing and sanitation guidelines can come into contact with other co-workers and may infect them. Thus, Malaysian government has imposed strict rules to only allow workers that have completed full doses of vaccination to resume work in the food preparation area. On another note, infection among staff members is not the only concern. Uddin et al. (2020) has added that there is a great chance of exposure of infection to healthy individuals if an infected person handles the food packaging, contaminates the packaging, and gives the infected product to a healthy, unassuming customer. This is because the virus may be able to enter the body of an healthy individual via oral, nasal, or optic routes ( Pressman et al., 2020 ). Moreover, the virus may reach fresh food products such as fruits, vegetables, and baked goods, or food packaging by means of an infected person through coughing or sneezing directly on them ( Duda-Chodak et al., 2020 ; Rizou et al., 2020 ). Therefore, personal hygiene of food handlers is paramount in food safety, more so during this COVID-19 pandemic, which should include proper handwashing procedures, strict SOPs, frequent cleaning and sanitization, maintaining food respiratory hygiene and frequent usage of alcohol based sanitisers ( Jyoti and Bhattacharya, 2021 ).

Although transmission through surface contact is not the common mode of transmission for COVID-19, there is still a possibility of transmission through food packaging materials. For example, an infected worker may expose other people to the virus by contaminating environmental surfaces or objects, which will lead to an infection when an unsuspecting person comes into contact with the item ( Duda-Chodak et al., 2020 ; Pressman et al., 2020 ). It is a complex situation as we are unable to view the virus with naked eyes to postulate which site needs to be cleaned or sanitized. Under this situation, it could lead to a rather secondary or indirect transmission. Additionally, Duda-Chodak et al. (2020) has stated that the indirect transmission of coronaviruses from contaminated surfaces has been postulated. It was reported that the coronaviruses can remain for prolonged periods in environmental samples, which may boost the chance of transmission through package contact surfaces ( Olaimat et al., 2020 ). This was further supported by Desai and Aronoff (2020) where they have stated that SARS-CoV-2 may remain active on objects or surfaces for up to 72 h. Cable et al. (2020) supported this by expressing that there has been evidence of viral RNA identified on various types of surfaces, including doorknobs and gloves, and depending on the surface, the viral half-life ranges from 1 to 2 days. In addition, Pressman et al. (2020) revealed that the SARS-CoV-2 was able to remain on cardboard for up to 24 h, and on plastic and stainless steel objects, for up to 72 h. This may come as a concern as most food packages are made of cardboard or plastic. Under such scenario, it may be speculated that food packages are able to transmit the virus to consumers or employees if it is contaminated. Thus, it is important to make sure that safety measures are enforced in restaurants and food processing or manufacturing factories to avoid any sort of contamination from workers to the food packaging materials, and from the packaging to workers or consumers. Proper sanitization performed at frequent intervals is crucial to ensure cross-contamination of the virus is not available at the industry or operational sites prior to reaching the consumers. On the other hand, consumers are also encouraged to sanitize their hands and surroundings accordingly after receiving food or groceries from restaurants or shops ( Desai and Aronoff, 2020 ). Additionally, food safety in terms on kitchen sanitation and sanitization is important to minimize the risk of transmission through tools, cooking utensils, and packaging materials from workers to workers or workers to customers. Supplementary Figure 3 shows customers adhering to social distancing guidelines while dining in ( Free Malaysia Today, 2020 ).

Therefore, although COVID-19 is not a foodborne illness, it may still be transmitted during food manufacturing and processing activities. Thus, some aspects of food safety such as personal hygiene, kitchen sanitation and sanitization process should still be emphasized greatly during this pandemic. Strict protocols must be enforced during processing and handling of foods such as not allowing individuals who are showing signs of sickness to work, increase in sanitation (handwashing with soap or disinfecting with an alcohol-based sanitiser), social distancing between individuals, as well as the use of face coverings such as face masks and face shields ( Cable et al., 2020 ). In fact, completion of two doses of vaccination is important at this stage in National Recovery Plan as enforced by the Malaysian government. Supplementary Figure 4 shows a restaurant worker complying to MCO guidelines by screening individuals who wish to enter the food premises ( Lim, 2020 ).

Steps to Ensure Food Safety

Pivotal steps must be taken to ensure the food safety in order to prevent the spread of COVID-19 by operations conducted in the food industry. As what have been mentioned previously, there are a few factors which affect food safety in the COVID-19 pandemic, which are personal hygiene of food handlers as well as kitchen sanitation and sanitization. The normal practices in personal hygiene and kitchen sanitation must be followed strictly to avoid the spread of COVID-19 through food processing activities such as manufacturing, packaging, transporting, and regular restaurant operations. Frequent sanitization is important at this point of pandemic regardless of whether dine-in is allowed. According to Djekic et al. (2021) , staff awareness and hygiene has been reported to be the two of the most important aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic which affect food safety. Supplementary Figure 5 shows some practices that are conducted to maintain personal hygiene of food handlers as well as kitchen sanitation in the food industry.

Personal hygiene of food handlers is extremely important as these handlers have prolonged contact with the food products. According to Djekic et al. (2021) , many food companies have taken the initiative to implement strict hygiene procedures as well as purchasing additional personal protective equipment (PPE) for their employees in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, Lacombe et al. (2020) has stated that many processing plants have also reopened with the implementation of physical barriers in support of social distancing as well as the use of PPE and completion of vaccination among workers. Thus, one of the key steps which will need to be taken to ensure food safety during the COVID-19 pandemic is in the use of proper protective attire, which includes face masks, bonnets, gloves, as well as face shields ( Cable et al., 2020 ). This step has been made compulsory to stop the transmission of the virus from person-to-person or person-to-object. Since the transmission of the COVID-19 virus is mainly through respiratory droplets produced by sneezing, coughing, or talking, the use of face coverings such as face masks and face shields are extremely crucial to stop the transmission and the contamination of food products, food contact surfaces as well as food packaging. Furthermore, the use of gloves and bonnets are important to make sure that the food does not become contaminated by the handler's hair or microorganisms which live on human skin. Not only that, the use of clean clothes by handlers is also important as the virus may also contaminate clothing items ( Duda-Chodak et al., 2020 ). Hence, the handler must ensure that their clothes are clean and they should not wear items of clothing that have been previously worn before in public places as they may be contaminated by the virus. Moreover, it is also necessary to avoid smoking, coughing, sneezing, chewing, or eating in food processing areas as these activities may cause the transmission of the virus to the environment, and not to mention to other employees.

Next, kitchen sanitation is also beneficial in stopping the transmission of the virus and to maintain the safety of the food products. The hygiene of the kitchen or production area where food is prepared is extremely important as many types of contamination to foods can arise from a dirty environment. According to Redmond and Griffith (2009) , some of the reasons as to why the hygiene of a kitchen may be compromised was due to inadequate design, lacking equipment of safe food preparation, and may be used for other non-food related purposes. Thus, several steps must be taken to make sure that the environment where food is processed is safe for its quality for human consumption. Firstly, the kitchen must be set up as to allow for the ease of proper hygiene practices such as sanitation and cleaning of floors and countertops. For instance, the kitchen should be built with materials that are suitable, durable and easy to be cleaned, in addition to being safe and not to harbor microorganisms ( Uçar et al., 2016 ). Additionally, a kitchen which has been built to cater to proper hygiene practices will ensure that the employees are able to easily carry out cleaning and sanitation practices, which in turn, will motivate them to be more inclined to continue the practice. This is vital as the continuity of cleaning and sanitation practices is as important as the design and plan of the kitchen ( Uçar et al., 2016 ). If the procedures are not carried out continuously then the kitchen cannot maintain its cleanliness. Furthermore, a cleaning and disinfection plan should be developed by the management, and the plan must be enforced and adhered to by the kitchen staff. This plan should be developed to ensure that the hygienic procedures are carried out effectively. Furthermore, it is also important to train employees on the proper sanitation and disinfection of a kitchen. In this regard, Byun et al. (2005) has stated that the level of awareness of kitchen sanitation among food service were determined by the management systems employed in the workplace as well as the extent of their sanitation training. Thus, education and training must be administered frequently and continuously to employees to strengthen the food handlers' knowledge in the area ( Abdul-Mutalib et al., 2012 ). Lastly, utensils and equipment should also be cleaned and sanitized frequently. Among various chemical disinfectants that are being used against SARS-CoV-2 virus, alcohol based solution has been the best to be used in food industries. Ethanol and isopropanol (concentration 70–90%) kills SARS-CoV-2 virus within 30 s and causes membrane damage by disrupting the tertiary structure of proteins while denaturing the virus's protein and rupturing the RNA ( Al-Sayah, 2020 ).

This is especially important in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic as the virus may contaminate kitchen utensils and equipment, which may lead to transmission to other employees or to food products or food packaging. Hence, these sanitation and sanitization plan should be in place, well-documented and included in trainings so that it can be practiced when it is necessary. Since pandemic was unexpected, management system regarding food safety should be adhered according to WHO and local Ministry of Health guidelines.

Aspects of personal hygiene of handlers and kitchen sanitation are not only important for large scale food industries or restaurants, but also necessary to be adhered to by small businesses or street food vendors. During the pandemic, it will only take one infected vendor to potentially spread the virus to a countless number of customers, vendors and even delivery personnel. For example, street food vendors or small-scale food businesses should still adhere to personal hygiene practices such as the wearing of clean clothes and proper protective attire, such as face coverings and gloves. Not only that, but vendors should also avoid doing activities that might spread diseases near food preparation areas such as smoking, coughing, eating, and sneezing. Additionally, Pritwani et al. (2015) has also stated that proper handwashing during all stages of processing must be followed strictly, as this is crucial not only to stop the spread of foodborne illnesses, but also to avoid spreading the COVID-19 virus. Supplementary Figure 6 shows a scene with street food vendors and customers seen wearing masks and adhering to social distancing guidelines.

Furthermore, kitchen sanitation is also important for street food vendors and small-scale food industries. Moreover, access to clean and safe water supply should be monitored in order to conduct proper cleaning and sanitation and sanitization activities ( Pritwani et al., 2015 ; Cortese et al., 2016 ). Additionally, it is also important for the relevant authorities to regularly monitor and supervise small-scale food vendors to ensure they are complying with proper food safety practices ( Cortese et al., 2016 ). Training must also be given as most of these small-scale vendors have not been formally educated to emphasize food safety, thus it is necessary for the relevant authorities to provide education and support to ensure that these vendors can still operate their businesses without the danger of selling food that are not safe for human consumption. For example, a recent case of food poisoning that occurred in Malaysia involved 99 victims that have consumed a local food product, “puding buih” ( Malay Mail, 2020 ). According to an article reported by New Straits Times (2020) , the dessert has been purchased online from a local vendor by the victims. Following the incident, the local authorities have provided SOPs to home-based food traders to ensure that they are able to generate income during this pandemic while at the same time able to guarantee the safety of the food being sold ( Malay Mail, 2020 ).

COVID-19 and the Food Supply Chain

What is the food supply chain.

The food supply chain can be described as the different processes that occur to bring food from production to the consumer or from farm to fork. Generally, the supply chain consists of processes such as agricultural production, post-harvest handling, processing, distribution and retail, and lastly consumption ( Rizou et al., 2020 ). The food supply chain is not a singular chain of fixed entities, instead it is a complex web of interconnected entities which work together to make the food available to the consumers ( Dani, 2015 ).

The maintenance of a functional food supply chain is very important in ensuring food can be provided to the consumers continuously. The closure of a single factory may pose a risk to a certain amount of people whom work at the factory, however the obstruction of key processes in the food supply chain such as production or distribution, may endanger a larger portion of the population that depend on the food to live ( Aday and Aday, 2020 ). This is because the disruption in the supply chain will cause a snowball effect in the food industry such as halting the processing and production of food, leading to the creation of insufficient products in the market, which in turn results in the inability to attain food by the consumers for nourishment. Thus, the COVID-19 pandemic may have serious effects to the food supply chain.

Impact of COVID-19 to the Food Supply Chain

As what have been mentioned, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought on many difficulties, especially in the food industry as many companies have been forced to either partially or even fully shut down. Many countries, including Malaysia, have implemented lockdowns and partial lockdowns periodically in order to curb the rising cases of infections as well as deaths. The overall impact on agricultural practices and business entities along the food supply chain are depicted in Supplementary Figure 7 .

One of the impacts of COVID-19 is the restriction of movement which has caused issues in the supply chain. As an example, in Malaysia, the MCO implemented by the government restricted movement by implementing travel restrictions that has further enforced by road blocks all over the country, as well as the limitation of a 10-km travel radius for all citizens ( Tang, 2020 ). When workers are unable to get to work due to travel restrictions, then the processes in the supply chain will be incapacitated ( Aday and Aday, 2020 ). During the first few weeks of the implementation of the MCO in Malaysia, many food supply chains, especially those in urban areas, have been disrupted due to these travel restrictions. Many of these supply chains rely on the use of land transports such as lorries to carry their products from farms located far from the urban cities ( Chin, 2020 ). This was supported by Tumin et al. (2020) which has stated that the MCO has affected the supply chain or organic food products in Malaysia in which these restrictions have heavily impacted the distribution of products from the producers to the consumers. As a result, some farmers or growers have resorted to send their produce out to charity, or those who had rose up white flags at their homes due to financial difficulties. The raising of the white flags started initially in front of residential homes; with further neighbors tend to help out with groceries and home basic necessities. Later on, several apps such as Bendera Putih and White Flag were developed by local Malaysians to track suffering families and anyone nearby can help out based on the app. Website Kita Jaga Malaysia ( kitajaga.co ) has also been developed for this cause ( Angelin, 2021 ).

Furthermore, lockdowns have led to other disruptions in the food supply chain, which was due to a shortage of labor ( Singh et al., 2020 ). Verma and Prakash (2020) have stated that about 13 million people all over the world may face unemployment, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO). Moreover, Nicola et al. (2020) has further indicated that the restrictions brought on by the pandemic has led to a reduction in the workforce across all economic sectors, causing many jobs to be lost. The National Recovery Plan has been introduced in June 2021 to minimize the surging number of COVID-19 cases in Malaysia due to the third-wave. Under this plan, the workers were encouraged to get vaccinated to reduce the overloading the hospitals.

As an example, Dr. Tey Yeong Sheng, a researcher at the Institute of Agricultural and Food Policy Studies at Universiti Putra Malaysia has stated that labor shortages was one of the main difficulties faced by local farmers in food production ( Chung, 2020 ). These farmers were faced with many obstacles as they are reliant on workers to harvest crops as well as for preparation of land. Thus, when these workers face difficulty in crossing states and traveling, the food production will be disrupted. This has affected the processing of crops, livestock, and fishery sub-sectors in the food industry, and it has impacted the agriculture value chain as well as the availability of these foods ( Vaghefi, 2020 ). Supplementary Figure 8 shows a lone farmer working in a field ( Man, 2020 ).

Labor shortages affect many levels of the food supply chain as each process requires workers to complete hands-on tasks such as harvesting, processing, and manufacturing. Even though some companies manage by allowing their employees to work from home, the same cannot be applied for the food industry as most businesses require workers to work hands on, such as in agricultural production or post-harvest handling. For instance, a vegetable producer may experience problems from shortage of labor, thus not allowing the farmer to harvest as many vegetables as usual. Therefore, there will be a shortage in the production of fresh vegetables.

Moreover, labor shortages will also affect the food distribution system due to the unavailability of workers, such as truck drivers to transport the food products from the distributors to the consumers ( Mahajan and Tomar, 2020 ; Singh et al., 2020 ). Surendran (2020) also pointed out that the number of employees working in day-to-day operations on farms has also been limited during the period of MCO in Malaysia. This view was supported by Nicola et al. (2020) , where the restrictions imposed due to the COVID-19 pandemic has been found to have impacted the availability of workers such as inspectors as well as delivery staff in ensuring the verification and transportation of food products. This in turn will cause a lack of food items being made available to the consumers ( Singh et al., 2020 ).

In addition, labor shortages also cause losses for the farmers. For example, due to the MCO conducted in Malaysia, 2,300 farmers had suffered a reported loss of RM1 million per day due to their inability in selling harvested produce, thus they were discarded as waste ( Man, 2020 ). Similarly, it has been reported that about 200 farmers were unable to sell their vegetables in Gua Musang, leading to a total loss of RM400,000 a day. They had been forced to discard up to 200 metric tons of vegetables per day. This is because agricultural produce such as vegetables and fruits are perishable items, and as such, when there are not enough workers available to harvest, process, and transport the products for sale, then the produce will not be sold and has to be discarded as waste. Furthermore, this situation occurs as consumers opt for online purchases rather than to go out to obtain their weekly groceries.

Additionally, the farmers also suffered loss as the MCO had required closure of many businesses as well as restriction of the number of people allowed in a certain area. This was due to the difficulty of exercising social distancing in many markets where farmers usually sell their produce, thus many of these markets have been forced to close down, or allowed to open but with limitations ( Chin, 2020 ). Supplementary Figure 9 shows a vendor in a market wearing protective clothing while waiting for customers ( Hassan and Leong, 2020 ). In order to support the current economic situation, National Recovery Plan has been introduced in a few phases based on number of cases and utilization of ICU beds in hospitals in different states. Hence, workforce is allowed with 2 completed doses of vaccination and to maintain strict SOP at the workplace.

For example, a wholesale market in Selayang, Selangor has been ordered to reduce the amount of workers and its operating hours, which has caused vegetable farmers and fishermen to forcefully dump their stock of produce as the products were unable to be sold ( Hassan and Leong, 2020 ). This situation had also been seen occurring in farmers in Cameron Highlands that had to dump or gave away their produce due to the perishable nature of their products ( Ng and Wahid, 2020 ). Supplementary Figure 10 shows a photograph of a worker destroying vegetables on a farm as they cannot be sold due to issues arising from the COVID-19 pandemic ( Surendran, 2020 ).

In addition, unavailability of food products is also a resulting effect from the COVID-19 pandemic on the food supply chain. For example, during the start of the pandemic where initial lockdowns were announced, many consumers have exhibited panic buying and hoarding ( Aday and Aday, 2020 ; Singh et al., 2020 ). As COVID-19 was still unknown then, consumers were uncertain of the severity of this virus and how to handle the lockdown restrictions, thus many had been seen buying large amounts of food items that they could store and use in an emergency such as canned foods. Furthermore, Koh et al. (2020) has stated that panic buying may occur when people observe other people in buying certain products, then mass fear infects the individual as they do not want to be left out of owning an item that appears to be running out. This was seen when people kept buying items even if they did not necessarily need them. However, these hoarding and panic buying have caused the sudden surge of demand for food items ( Singh et al., 2020 ), As a result, many manufacturers and retailers had not been able to keep up with the demand, thus some less unfortunate people were unable to buy any food products to stock up during the lockdown. Furthermore, panic buying has also caused the increase in concerns of food shortages, including long-life foods like UHT milk, rice, pasta, as well as canned foods ( Nicola et al., 2020 ). The unavailability of food products would also induce price spikes due to high demand ( Aday and Aday, 2020 ; Mahajan and Tomar, 2020 ; Reardon et al., 2020 ). The increase in prices will negatively affect poorer households as certain food items will no longer become accessible to them ( Mahajan and Tomar, 2020 ). Lastly, the lack of food products in the market will give health repercussions as well-due to a decrease in intake of nutritionally balanced foods and lack of diversity in the diet ( Mahajan and Tomar, 2020 ). This is especially dangerous during a pandemic as maintaining one's health is of upmost importance in order to avoid contracting COVID-19 ( Uddin et al., 2020 ). Supplementary Figure 11 shows consumers crowding at a grocery store following announcements of a MCO ( Free Malaysia Today, 2021 ).

Conclusion and Recommendations

In conclusion, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought on some effects to food safety and the food supply chain. Although COVID-19 is said to not be a foodborne virus, it is still important to maintain proper food safety protocols in the food industry. The novelty of this study is to highlight that maintaining good personal hygiene of handlers is utterly important in food industries. Completion of the vaccination dosage is vital to achieve herd immunity. Besides, it is significant to point that the maintenance of kitchen sanitation is essential during this pandemic. This is due to the possibility of transmission of COVID-19 through the food handlers as well as by food packaging materials. It is important for food handlers to maintain good hygiene and kitchen sanitation to help keep themselves safe, as well as their surroundings clean and free from contamination, which in turn will minimize the spread of COVID-19. It seems like a complex mechanism, however, the safety of food and handlers can be maintained altogether if managed properly. Furthermore, COVID-19 has also made an impact on the food supply chain. Due to the strict lockdowns as well as many protocols involving social distancing and travel restrictions, the food supply chain has seen some negative effects in light of this pandemic. Some of these effects include shortages in labor which have caused disruption in the supply chain, as well as the lack of distribution of food products to consumers. Next, other effects include shortages of food, increase in prices, and health repercussions to the consumers due a lack of diversity in the diet and a decrease intake of nutritious foods. It is therefore crucial to ensure that the food supply chain has a smooth progression to maintain the constant supply of food commodity for consumption in Malaysia. At the moment, it is quite common to have delays in supply than usual due to current supply chain situation. All the threats and implication presented in this review have been assessed thoroughly, where the information was extracted from reports, local newspaper articles and manuscripts. This study is important to policymakers in the food industries, enabling designing management system and training needed during and post-pandemic situation to ensure continuous food safety and supply chain are in good progression.