Limitations of the literature – A guide to a sticky problem

One of the more difficult tasks set for a Masters and especially PhD student is to identify limitations in the literature under review. Postgraduate students are required not only to “tell” (repeat what an author/s say) but to critically engage the literature being reviewed. This work typically appears in a separate chapter in the thesis or dissertation under the title Literature Review. To help you, here are 10 typical examples often used to identify limitations in a particular body of literature—with a caveat—using education examples.

1. The sample size is too small and therefore not representative of the phenomenon being studied This is fine but be aware of the fact that a single case study (e.g. the leadership practices of a non-traditional principal) is completely acceptable in a qualitative study. Here depth makes up for spread (representivity) for the purpose of the study is different e.g. an ethnographic case study of one principal.

2. The context is limiting and therefore not representative of all This too is acceptable e.g. a study of subject competency levels of 10 science teachers in rural Limpopo province. However, always specific WHAT it is about the context that is limiting e.g. nothing about science teachers in urban areas. A common mistake is to say ‘that study was done in America’ but that is not helpful in itself. What is it about the American context that might not be applicable in the Southern African context?

3. The study is dated as in out-of-date e.g. 1985 This is important as a criticism except in the case of historical studies or in reference to a classical piece of work that set the standard for understanding a particular problem. For example, Michael Apple’s 1979 Ideology and Curriculum might be dated but it is the landmark criticism in the politics of curriculum and often deserves referencing as a launching pad for more recent studies.

4. The period of observation was too short This is valuable especially in the qualitative study of classrooms where the researcher visits a history class of 10 teachers once and then jumps to make major findings and conclusions from a 40-minute lesson per teacher. This is a common problem with qualitative research in education in South Africa—the lack of extended engagement in the field.

5. The theoretical framework or theory is limiting A researcher might be using a particular theory to explain events e.g. a behaviorist account of learner discipline where you believe that a constructivist account offers more insight into why learners misbehave in classrooms. The onus is still on you to explain why the rival theory is ‘better’ than the one used.

6. The methodological approach is inappropriate for the question posed A study uses a self-reporting questionnaire completed by teachers to determine their competency levels in mathematics teaching. You could argue that direct observation of actual teaching is a much more direct measure of teaching competency in mathematics since teachers might overestimate their own levels of competency in the subject (by the way, there is research to back you up with such a claim)

7. The research question or instrument(s) is biased A study that asks ‘why teachers are incompetent’ or ‘the students are lazy’ already assumes the fact ahead of the inquiry itself. The research question can and should be posed in an open-ended manner to allow for more than one outcome. In the controversial SU study on Coloured women’s cognitive abilities and health styles it was found that the measuring instrument used was found in other studies to be flawed. And the study of code-switching in a Grade 6 language classroom would clearly show bias if the researcher was competent in English alone—unless, of course, this deficiency is remedied in the study design.

8. The study does not differentiate between subjects or contexts A report might give the results of a study for academic performance in Grade 12 economics in the National Senior Certificate, which is fine, but does not differentiate between the results of the former white schools and those of black schools thereby concealing variable performance and, for the sake of reform, where exactly added support might be needed.

9. The literature reviewed does not cover the subject at all or from a particular perspective The conclusion that ‘there is no research on topic X’ is a common one among students and often wrong. The fact that you have not yet found literature on topic X does not mean that such references do not exist. However, there are instances in which the case can and should be made that topic X appears to be understudied given the literature reviewed. Hint: always check with your supervisor and other experts whether the ‘not yet researched’ claim is justified. More plausible are studies which critique a dominant perspective on a subject and offer a new lens on the same issue (see point #5) above.

10. The study is based largely on opinion and uses primarily secondary sources This is a very valid criticism of many articles posing as research studies where the evidence is often anecdotal (not ‘thick descriptions’ as anthropologists like to point out) and drawing on other opinion pieces rather than solid research on the topic.

REMEMBER: THESE NOTES ARE NOT ABOUT HOW TO IDENTIFY LIMITATIONS IN LITERATURE REVIEWED FOR YOUR STUDY. IT IS NOT ABOUT LISTING THE LIMITATIONS OF YOUR STUDY IN THE COURSE OF WRITING UP A RESEARCH PROPOSAL OR THE THESIS ITSELF, EVEN THOUGH THIS COULD HELP YOU DEFEND SELF-IDENTIFIED LIMITATIONS OF YOUR RESEARCH.

The upsides to a pandemic: from jobs to teaching, it’s not all bad news

Let’s face facts, the 2020 school year is lost. so what to do, you may also like, corrupted: a study of chronic dysfunction in south..., learning under lockdown – 100 student voices, ten elements of a good literature review, ten rules for turning a dissertation into a....

This was very helpful to me.

Truly helpful. So much valuable information on this site that’s worth spreading across all social media platforms.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Power To Truth With JJ Tabane

Corrupted: a study of chronic dysfunction in south…, limitations of the literature – a guide to…, honorary doctorate – uct faculty of humanities graduation…, ten rules for turning a dissertation into a…, what happens to your rights in a pandemic, trading places, a different take, my south africa, q&a-plus: let’s clear up some confusion about matric…, relocating some universities to places of relative safety…, there’s always room for more students, better planning,…, bela, my dear, where did we go wrong.

- Books published in 2022 & 2023

- Recent Research

- Presentations

- Speaking Requests

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Limitations of the Study

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

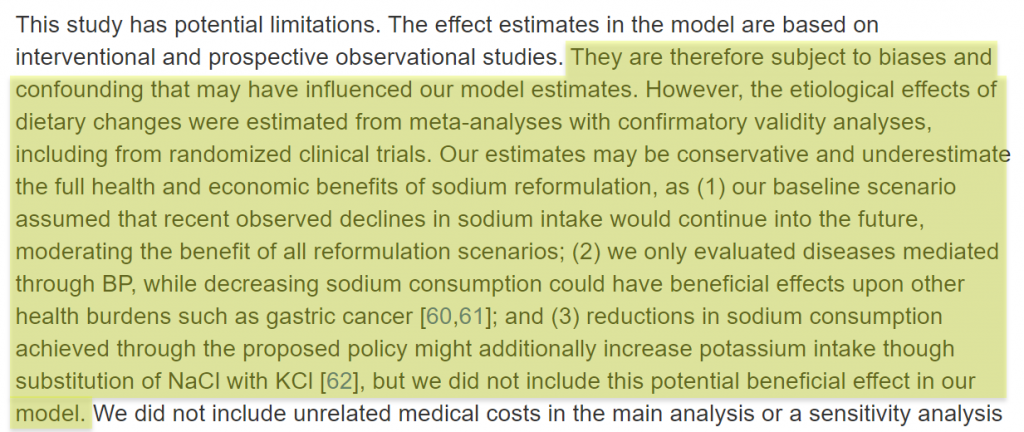

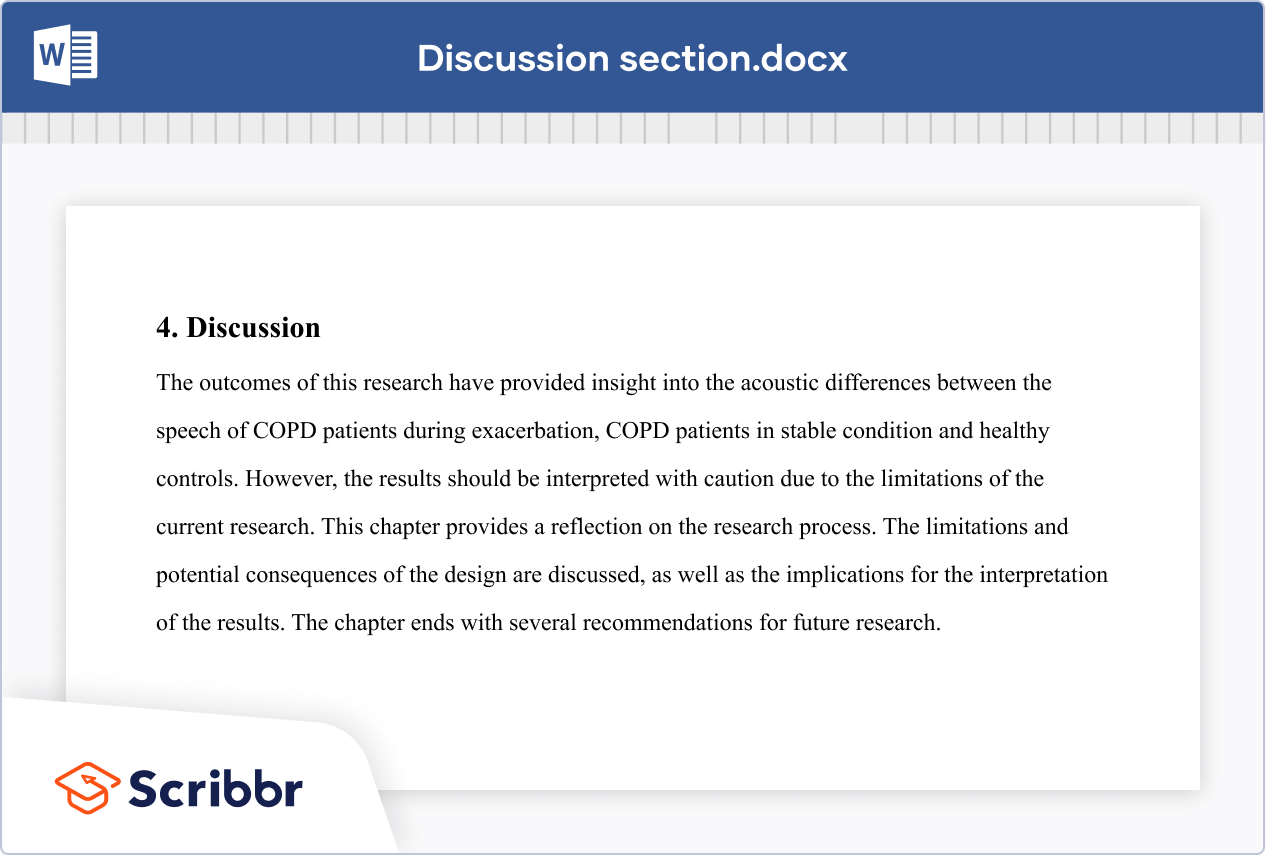

The limitations of the study are those characteristics of design or methodology that impacted or influenced the interpretation of the findings from your research. Study limitations are the constraints placed on the ability to generalize from the results, to further describe applications to practice, and/or related to the utility of findings that are the result of the ways in which you initially chose to design the study or the method used to establish internal and external validity or the result of unanticipated challenges that emerged during the study.

Price, James H. and Judy Murnan. “Research Limitations and the Necessity of Reporting Them.” American Journal of Health Education 35 (2004): 66-67; Theofanidis, Dimitrios and Antigoni Fountouki. "Limitations and Delimitations in the Research Process." Perioperative Nursing 7 (September-December 2018): 155-163. .

Importance of...

Always acknowledge a study's limitations. It is far better that you identify and acknowledge your study’s limitations than to have them pointed out by your professor and have your grade lowered because you appeared to have ignored them or didn't realize they existed.

Keep in mind that acknowledgment of a study's limitations is an opportunity to make suggestions for further research. If you do connect your study's limitations to suggestions for further research, be sure to explain the ways in which these unanswered questions may become more focused because of your study.

Acknowledgment of a study's limitations also provides you with opportunities to demonstrate that you have thought critically about the research problem, understood the relevant literature published about it, and correctly assessed the methods chosen for studying the problem. A key objective of the research process is not only discovering new knowledge but also to confront assumptions and explore what we don't know.

Claiming limitations is a subjective process because you must evaluate the impact of those limitations . Don't just list key weaknesses and the magnitude of a study's limitations. To do so diminishes the validity of your research because it leaves the reader wondering whether, or in what ways, limitation(s) in your study may have impacted the results and conclusions. Limitations require a critical, overall appraisal and interpretation of their impact. You should answer the question: do these problems with errors, methods, validity, etc. eventually matter and, if so, to what extent?

Price, James H. and Judy Murnan. “Research Limitations and the Necessity of Reporting Them.” American Journal of Health Education 35 (2004): 66-67; Structure: How to Structure the Research Limitations Section of Your Dissertation. Dissertations and Theses: An Online Textbook. Laerd.com.

Descriptions of Possible Limitations

All studies have limitations . However, it is important that you restrict your discussion to limitations related to the research problem under investigation. For example, if a meta-analysis of existing literature is not a stated purpose of your research, it should not be discussed as a limitation. Do not apologize for not addressing issues that you did not promise to investigate in the introduction of your paper.

Here are examples of limitations related to methodology and the research process you may need to describe and discuss how they possibly impacted your results. Note that descriptions of limitations should be stated in the past tense because they were discovered after you completed your research.

Possible Methodological Limitations

- Sample size -- the number of the units of analysis you use in your study is dictated by the type of research problem you are investigating. Note that, if your sample size is too small, it will be difficult to find significant relationships from the data, as statistical tests normally require a larger sample size to ensure a representative distribution of the population and to be considered representative of groups of people to whom results will be generalized or transferred. Note that sample size is generally less relevant in qualitative research if explained in the context of the research problem.

- Lack of available and/or reliable data -- a lack of data or of reliable data will likely require you to limit the scope of your analysis, the size of your sample, or it can be a significant obstacle in finding a trend and a meaningful relationship. You need to not only describe these limitations but provide cogent reasons why you believe data is missing or is unreliable. However, don’t just throw up your hands in frustration; use this as an opportunity to describe a need for future research based on designing a different method for gathering data.

- Lack of prior research studies on the topic -- citing prior research studies forms the basis of your literature review and helps lay a foundation for understanding the research problem you are investigating. Depending on the currency or scope of your research topic, there may be little, if any, prior research on your topic. Before assuming this to be true, though, consult with a librarian! In cases when a librarian has confirmed that there is little or no prior research, you may be required to develop an entirely new research typology [for example, using an exploratory rather than an explanatory research design ]. Note again that discovering a limitation can serve as an important opportunity to identify new gaps in the literature and to describe the need for further research.

- Measure used to collect the data -- sometimes it is the case that, after completing your interpretation of the findings, you discover that the way in which you gathered data inhibited your ability to conduct a thorough analysis of the results. For example, you regret not including a specific question in a survey that, in retrospect, could have helped address a particular issue that emerged later in the study. Acknowledge the deficiency by stating a need for future researchers to revise the specific method for gathering data.

- Self-reported data -- whether you are relying on pre-existing data or you are conducting a qualitative research study and gathering the data yourself, self-reported data is limited by the fact that it rarely can be independently verified. In other words, you have to the accuracy of what people say, whether in interviews, focus groups, or on questionnaires, at face value. However, self-reported data can contain several potential sources of bias that you should be alert to and note as limitations. These biases become apparent if they are incongruent with data from other sources. These are: (1) selective memory [remembering or not remembering experiences or events that occurred at some point in the past]; (2) telescoping [recalling events that occurred at one time as if they occurred at another time]; (3) attribution [the act of attributing positive events and outcomes to one's own agency, but attributing negative events and outcomes to external forces]; and, (4) exaggeration [the act of representing outcomes or embellishing events as more significant than is actually suggested from other data].

Possible Limitations of the Researcher

- Access -- if your study depends on having access to people, organizations, data, or documents and, for whatever reason, access is denied or limited in some way, the reasons for this needs to be described. Also, include an explanation why being denied or limited access did not prevent you from following through on your study.

- Longitudinal effects -- unlike your professor, who can literally devote years [even a lifetime] to studying a single topic, the time available to investigate a research problem and to measure change or stability over time is constrained by the due date of your assignment. Be sure to choose a research problem that does not require an excessive amount of time to complete the literature review, apply the methodology, and gather and interpret the results. If you're unsure whether you can complete your research within the confines of the assignment's due date, talk to your professor.

- Cultural and other type of bias -- we all have biases, whether we are conscience of them or not. Bias is when a person, place, event, or thing is viewed or shown in a consistently inaccurate way. Bias is usually negative, though one can have a positive bias as well, especially if that bias reflects your reliance on research that only support your hypothesis. When proof-reading your paper, be especially critical in reviewing how you have stated a problem, selected the data to be studied, what may have been omitted, the manner in which you have ordered events, people, or places, how you have chosen to represent a person, place, or thing, to name a phenomenon, or to use possible words with a positive or negative connotation. NOTE : If you detect bias in prior research, it must be acknowledged and you should explain what measures were taken to avoid perpetuating that bias. For example, if a previous study only used boys to examine how music education supports effective math skills, describe how your research expands the study to include girls.

- Fluency in a language -- if your research focuses , for example, on measuring the perceived value of after-school tutoring among Mexican-American ESL [English as a Second Language] students and you are not fluent in Spanish, you are limited in being able to read and interpret Spanish language research studies on the topic or to speak with these students in their primary language. This deficiency should be acknowledged.

Aguinis, Hermam and Jeffrey R. Edwards. “Methodological Wishes for the Next Decade and How to Make Wishes Come True.” Journal of Management Studies 51 (January 2014): 143-174; Brutus, Stéphane et al. "Self-Reported Limitations and Future Directions in Scholarly Reports: Analysis and Recommendations." Journal of Management 39 (January 2013): 48-75; Senunyeme, Emmanuel K. Business Research Methods. Powerpoint Presentation. Regent University of Science and Technology; ter Riet, Gerben et al. “All That Glitters Isn't Gold: A Survey on Acknowledgment of Limitations in Biomedical Studies.” PLOS One 8 (November 2013): 1-6.

Structure and Writing Style

Information about the limitations of your study are generally placed either at the beginning of the discussion section of your paper so the reader knows and understands the limitations before reading the rest of your analysis of the findings, or, the limitations are outlined at the conclusion of the discussion section as an acknowledgement of the need for further study. Statements about a study's limitations should not be buried in the body [middle] of the discussion section unless a limitation is specific to something covered in that part of the paper. If this is the case, though, the limitation should be reiterated at the conclusion of the section.

If you determine that your study is seriously flawed due to important limitations , such as, an inability to acquire critical data, consider reframing it as an exploratory study intended to lay the groundwork for a more complete research study in the future. Be sure, though, to specifically explain the ways that these flaws can be successfully overcome in a new study.

But, do not use this as an excuse for not developing a thorough research paper! Review the tab in this guide for developing a research topic . If serious limitations exist, it generally indicates a likelihood that your research problem is too narrowly defined or that the issue or event under study is too recent and, thus, very little research has been written about it. If serious limitations do emerge, consult with your professor about possible ways to overcome them or how to revise your study.

When discussing the limitations of your research, be sure to:

- Describe each limitation in detailed but concise terms;

- Explain why each limitation exists;

- Provide the reasons why each limitation could not be overcome using the method(s) chosen to acquire or gather the data [cite to other studies that had similar problems when possible];

- Assess the impact of each limitation in relation to the overall findings and conclusions of your study; and,

- If appropriate, describe how these limitations could point to the need for further research.

Remember that the method you chose may be the source of a significant limitation that has emerged during your interpretation of the results [for example, you didn't interview a group of people that you later wish you had]. If this is the case, don't panic. Acknowledge it, and explain how applying a different or more robust methodology might address the research problem more effectively in a future study. A underlying goal of scholarly research is not only to show what works, but to demonstrate what doesn't work or what needs further clarification.

Aguinis, Hermam and Jeffrey R. Edwards. “Methodological Wishes for the Next Decade and How to Make Wishes Come True.” Journal of Management Studies 51 (January 2014): 143-174; Brutus, Stéphane et al. "Self-Reported Limitations and Future Directions in Scholarly Reports: Analysis and Recommendations." Journal of Management 39 (January 2013): 48-75; Ioannidis, John P.A. "Limitations are not Properly Acknowledged in the Scientific Literature." Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 60 (2007): 324-329; Pasek, Josh. Writing the Empirical Social Science Research Paper: A Guide for the Perplexed. January 24, 2012. Academia.edu; Structure: How to Structure the Research Limitations Section of Your Dissertation. Dissertations and Theses: An Online Textbook. Laerd.com; What Is an Academic Paper? Institute for Writing Rhetoric. Dartmouth College; Writing the Experimental Report: Methods, Results, and Discussion. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University.

Writing Tip

Don't Inflate the Importance of Your Findings!

After all the hard work and long hours devoted to writing your research paper, it is easy to get carried away with attributing unwarranted importance to what you’ve done. We all want our academic work to be viewed as excellent and worthy of a good grade, but it is important that you understand and openly acknowledge the limitations of your study. Inflating the importance of your study's findings could be perceived by your readers as an attempt hide its flaws or encourage a biased interpretation of the results. A small measure of humility goes a long way!

Another Writing Tip

Negative Results are Not a Limitation!

Negative evidence refers to findings that unexpectedly challenge rather than support your hypothesis. If you didn't get the results you anticipated, it may mean your hypothesis was incorrect and needs to be reformulated. Or, perhaps you have stumbled onto something unexpected that warrants further study. Moreover, the absence of an effect may be very telling in many situations, particularly in experimental research designs. In any case, your results may very well be of importance to others even though they did not support your hypothesis. Do not fall into the trap of thinking that results contrary to what you expected is a limitation to your study. If you carried out the research well, they are simply your results and only require additional interpretation.

Lewis, George H. and Jonathan F. Lewis. “The Dog in the Night-Time: Negative Evidence in Social Research.” The British Journal of Sociology 31 (December 1980): 544-558.

Yet Another Writing Tip

Sample Size Limitations in Qualitative Research

Sample sizes are typically smaller in qualitative research because, as the study goes on, acquiring more data does not necessarily lead to more information. This is because one occurrence of a piece of data, or a code, is all that is necessary to ensure that it becomes part of the analysis framework. However, it remains true that sample sizes that are too small cannot adequately support claims of having achieved valid conclusions and sample sizes that are too large do not permit the deep, naturalistic, and inductive analysis that defines qualitative inquiry. Determining adequate sample size in qualitative research is ultimately a matter of judgment and experience in evaluating the quality of the information collected against the uses to which it will be applied and the particular research method and purposeful sampling strategy employed. If the sample size is found to be a limitation, it may reflect your judgment about the methodological technique chosen [e.g., single life history study versus focus group interviews] rather than the number of respondents used.

Boddy, Clive Roland. "Sample Size for Qualitative Research." Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 19 (2016): 426-432; Huberman, A. Michael and Matthew B. Miles. "Data Management and Analysis Methods." In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, eds. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994), pp. 428-444; Blaikie, Norman. "Confounding Issues Related to Determining Sample Size in Qualitative Research." International Journal of Social Research Methodology 21 (2018): 635-641; Oppong, Steward Harrison. "The Problem of Sampling in qualitative Research." Asian Journal of Management Sciences and Education 2 (2013): 202-210.

- << Previous: 8. The Discussion

- Next: 9. The Conclusion >>

- Last Updated: Apr 1, 2024 9:56 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- About the LSE Impact Blog

- Comments Policy

- Popular Posts

- Recent Posts

- Subscribe to the Impact Blog

- Write for us

- LSE comment

Neal Haddaway

October 19th, 2020, 8 common problems with literature reviews and how to fix them.

3 comments | 314 shares

Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

Literature reviews are an integral part of the process and communication of scientific research. Whilst systematic reviews have become regarded as the highest standard of evidence synthesis, many literature reviews fall short of these standards and may end up presenting biased or incorrect conclusions. In this post, Neal Haddaway highlights 8 common problems with literature review methods, provides examples for each and provides practical solutions for ways to mitigate them.

Enjoying this blogpost? 📨 Sign up to our mailing list and receive all the latest LSE Impact Blog news direct to your inbox.

Researchers regularly review the literature – it’s an integral part of day-to-day research: finding relevant research, reading and digesting the main findings, summarising across papers, and making conclusions about the evidence base as a whole. However, there is a fundamental difference between brief, narrative approaches to summarising a selection of studies and attempting to reliably and comprehensively summarise an evidence base to support decision-making in policy and practice.

So-called ‘evidence-informed decision-making’ (EIDM) relies on rigorous systematic approaches to synthesising the evidence. Systematic review has become the highest standard of evidence synthesis and is well established in the pipeline from research to practice in the field of health . Systematic reviews must include a suite of specifically designed methods for the conduct and reporting of all synthesis activities (planning, searching, screening, appraising, extracting data, qualitative/quantitative/mixed methods synthesis, writing; e.g. see the Cochrane Handbook ). The method has been widely adapted into other fields, including environment (the Collaboration for Environmental Evidence ) and social policy (the Campbell Collaboration ).

Despite the growing interest in systematic reviews, traditional approaches to reviewing the literature continue to persist in contemporary publications across disciplines. These reviews, some of which are incorrectly referred to as ‘systematic’ reviews, may be susceptible to bias and as a result, may end up providing incorrect conclusions. This is of particular concern when reviews address key policy- and practice- relevant questions, such as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic or climate change.

These limitations with traditional literature review approaches could be improved relatively easily with a few key procedures; some of them not prohibitively costly in terms of skill, time or resources.

In our recent paper in Nature Ecology and Evolution , we highlight 8 common problems with traditional literature review methods, provide examples for each from the field of environmental management and ecology, and provide practical solutions for ways to mitigate them.

There is a lack of awareness and appreciation of the methods needed to ensure systematic reviews are as free from bias and as reliable as possible: demonstrated by recent, flawed, high-profile reviews. We call on review authors to conduct more rigorous reviews, on editors and peer-reviewers to gate-keep more strictly, and the community of methodologists to better support the broader research community. Only by working together can we build and maintain a strong system of rigorous, evidence-informed decision-making in conservation and environmental management.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the LSE Impact Blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below

Image credit: Jaeyoung Geoffrey Kang via unsplash

About the author

Neal Haddaway is a Senior Research Fellow at the Stockholm Environment Institute, a Humboldt Research Fellow at the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change, and a Research Associate at the Africa Centre for Evidence. He researches evidence synthesis methodology and conducts systematic reviews and maps in the field of sustainability and environmental science. His main research interests focus on improving the transparency, efficiency and reliability of evidence synthesis as a methodology and supporting evidence synthesis in resource constrained contexts. He co-founded and coordinates the Evidence Synthesis Hackathon (www.eshackathon.org) and is the leader of the Collaboration for Environmental Evidence centre at SEI. @nealhaddaway

Why is mission creep a problem and not a legitimate response to an unexpected finding in the literature? Surely the crucial points are that the review’s scope is stated clearly and implemented rigorously, not when the scope was finalised.

- Pingback: Quick, but not dirty – Can rapid evidence reviews reliably inform policy? | Impact of Social Sciences

#9. Most of them are terribly boring. Which is why I teach students how to make them engaging…and useful.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Related Posts

“But I’m not ready!” Common barriers to writing and how to overcome them

November 16th, 2020.

“Remember a condition of academic writing is that we expose ourselves to critique” – 15 steps to revising journal articles

January 18th, 2017.

A simple guide to ethical co-authorship

March 29th, 2021.

How common is academic plagiarism?

February 8th, 2024.

Visit our sister blog LSE Review of Books

- Cookies & Privacy

- GETTING STARTED

- Introduction

- FUNDAMENTALS

- Acknowledgements

- Research questions & hypotheses

- Concepts, constructs & variables

- Research limitations

- Getting started

- Sampling Strategy

- Research Quality

- Research Ethics

- Data Analysis

How to structure the Research Limitations section of your dissertation

There is no "one best way" to structure the Research Limitations section of your dissertation. However, we recommend a structure based on three moves : the announcing , reflecting and forward looking move. The announcing move immediately allows you to identify the limitations of your dissertation and explain how important each of these limitations is. The reflecting move provides greater depth, helping to explain the nature of the limitations and justify the choices that you made during the research process. Finally, the forward looking move enables you to suggest how such limitations could be overcome in future. The collective aim of these three moves is to help you walk the reader through your Research Limitations section in a succinct and structured way. This will make it clear to the reader that you recognise the limitations of your own research, that you understand why such factors are limitations, and can point to ways of combating these limitations if future research was carried out. This article explains what should be included in each of these three moves :

- THE ANNOUNCING MOVE: Identifying limitations and explaining how important they are

- THE REFLECTING MOVE: Explaining the nature of the limitations and justifying the choices you made

- THE FORWARD LOOKING MOVE: Suggesting how such limitations could be overcome in future

THE ANNOUNCING MOVE Identifying limitations, and explaining how important they are

There are many possible limitations that your research may have faced. However, is not necessary for you to discuss all of these limitations in your Research Limitations section. After all, you are not writing a 2000 word critical review of the limitations of your dissertation, just a 200-500 word critique that is only one section long (i.e., the Research Limitations section within your Conclusions chapter). Therefore, in this first announcing move , we would recommend that you identify only those limitations that had the greatest potential impact on: (a) the quality of your findings; and (b) your ability to effectively answer your research questions and/or hypotheses.

We use the word potential impact because we often do not know the degree to which different factors limited our findings or our ability to effectively answer our research questions and/or hypotheses. For example, we know that when adopting a quantitative research design, a failure to use a probability sampling technique significantly limits our ability to make broader generalisations from our results (i.e., our ability to make statistical inferences from our sample to the population being studied). However, the degree to which this reduces the quality of our findings is a matter of debate. Also, whilst the lack of a probability sampling technique when using a quantitative research design is a very obvious example of a research limitation, other limitations are far less clear. Therefore, the key point is to focus on those limitations that you feel had the greatest impact on your findings, as well as your ability to effectively answer your research questions and/or hypotheses.

Overall, the announcing move should be around 10-20% of the total word count of the Research Limitations section.

THE REFLECTING MOVE Explaining the nature of the limitations and justifying the choices you made

Having identified the most important limitations to your dissertation in the announcing move , the reflecting move focuses on explaining the nature of these limitations and justifying the choices that you made during the research process. This part should be around 60-70% of the total word count of the Research Limitations section.

It is important to remember at this stage that all research suffers from limitations, whether it is performed by undergraduate and master's level dissertation students, or seasoned academics. Acknowledging such limitations should not be viewed as a weakness, highlighting to the person marking your work the reasons why you should receive a lower grade. Instead, the reader is more likely to accept that you recognise the limitations of your own research if you write a high quality reflecting move . This is because explaining the limitations of your research and justifying the choices you made during the dissertation process demonstrates the command that you had over your research.

We talk about explaining the nature of the limitations in your dissertation because such limitations are highly research specific. Let's take the example of potential limitations to your sampling strategy. Whilst you may have a number of potential limitations in sampling strategy, let's focus on the lack of probability sampling ; that is, of all the different types of sampling technique that you could have used [see Types of probability sampling and Types of non-probability sampling ], you choose not to use a probability sampling technique (e.g., simple random sampling , systematic random sampling , stratified random sampling ). As mentioned, if you used a quantitative research design in your dissertation, the lack of probability sampling is an important, obvious limitation to your research. This is because it prevents you from making generalisations about the population you are studying (e.g. Facebook usage at a single university of 20,000 students) from the data you have collected (e.g., a survey of 400 students at the same university). Since an important component of quantitative research is such generalisation, this is a clear limitation. However, the lack of a probability sampling technique is not viewed as a limitation if you used a qualitative research design. In qualitative research designs, a non-probability sampling technique is typically selected over a probability sampling technique.

And this is just part of the puzzle?

Even if you used a quantitative research design, but failed to employ a probability sampling technique, there are still many perfectly justifiable reasons why you could have made such a choice. For example, it may have been impossible (or near on impossible) to get a list of the population you were studying (e.g., a list of all the 20,000 students at the single university you were interested in). Since probability sampling is only possible when we have such a list, the lack of such a list or inability to attain such a list is a perfectly justifiable reason for not using a probability sampling technique; even if such a technique is the ideal.

As such, the purpose of all the guides we have written on research limitations is to help you: (a) explain the nature of the limitations in your dissertation; and (b) justify the choices you made.

In helping you to justifying the choices that you made, these articles explain not only when something is, in theory , an obvious limitation, but how, in practice , such a limitation was not necessarily so damaging to the quality of your dissertation. This should significantly strengthen the quality of your Research Limitations section.

THE FORWARD LOOKING MOVE Suggesting how such limitations could be overcome in future

Finally, the forward looking move builds on the reflecting move by suggesting how the limitations you have discuss could be overcome through future research. Whilst a lot could be written in this part of the Research Limitations section, we would recommend that it is only around 10-20% of the total word count for this section.

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

APA Citation Generator

MLA Citation Generator

Chicago Citation Generator

Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Present the Limitations of the Study Examples

What are the limitations of a study?

The limitations of a study are the elements of methodology or study design that impact the interpretation of your research results. The limitations essentially detail any flaws or shortcomings in your study. Study limitations can exist due to constraints on research design, methodology, materials, etc., and these factors may impact the findings of your study. However, researchers are often reluctant to discuss the limitations of their study in their papers, feeling that bringing up limitations may undermine its research value in the eyes of readers and reviewers.

In spite of the impact it might have (and perhaps because of it) you should clearly acknowledge any limitations in your research paper in order to show readers—whether journal editors, other researchers, or the general public—that you are aware of these limitations and to explain how they affect the conclusions that can be drawn from the research.

In this article, we provide some guidelines for writing about research limitations, show examples of some frequently seen study limitations, and recommend techniques for presenting this information. And after you have finished drafting and have received manuscript editing for your work, you still might want to follow this up with academic editing before submitting your work to your target journal.

Why do I need to include limitations of research in my paper?

Although limitations address the potential weaknesses of a study, writing about them toward the end of your paper actually strengthens your study by identifying any problems before other researchers or reviewers find them.

Furthermore, pointing out study limitations shows that you’ve considered the impact of research weakness thoroughly and have an in-depth understanding of your research topic. Since all studies face limitations, being honest and detailing these limitations will impress researchers and reviewers more than ignoring them.

Where should I put the limitations of the study in my paper?

Some limitations might be evident to researchers before the start of the study, while others might become clear while you are conducting the research. Whether these limitations are anticipated or not, and whether they are due to research design or to methodology, they should be clearly identified and discussed in the discussion section —the final section of your paper. Most journals now require you to include a discussion of potential limitations of your work, and many journals now ask you to place this “limitations section” at the very end of your article.

Some journals ask you to also discuss the strengths of your work in this section, and some allow you to freely choose where to include that information in your discussion section—make sure to always check the author instructions of your target journal before you finalize a manuscript and submit it for peer review .

Limitations of the Study Examples

There are several reasons why limitations of research might exist. The two main categories of limitations are those that result from the methodology and those that result from issues with the researcher(s).

Common Methodological Limitations of Studies

Limitations of research due to methodological problems can be addressed by clearly and directly identifying the potential problem and suggesting ways in which this could have been addressed—and SHOULD be addressed in future studies. The following are some major potential methodological issues that can impact the conclusions researchers can draw from the research.

Issues with research samples and selection

Sampling errors occur when a probability sampling method is used to select a sample, but that sample does not reflect the general population or appropriate population concerned. This results in limitations of your study known as “sample bias” or “selection bias.”

For example, if you conducted a survey to obtain your research results, your samples (participants) were asked to respond to the survey questions. However, you might have had limited ability to gain access to the appropriate type or geographic scope of participants. In this case, the people who responded to your survey questions may not truly be a random sample.

Insufficient sample size for statistical measurements

When conducting a study, it is important to have a sufficient sample size in order to draw valid conclusions. The larger the sample, the more precise your results will be. If your sample size is too small, it will be difficult to identify significant relationships in the data.

Normally, statistical tests require a larger sample size to ensure that the sample is considered representative of a population and that the statistical result can be generalized to a larger population. It is a good idea to understand how to choose an appropriate sample size before you conduct your research by using scientific calculation tools—in fact, many journals now require such estimation to be included in every manuscript that is sent out for review.

Lack of previous research studies on the topic

Citing and referencing prior research studies constitutes the basis of the literature review for your thesis or study, and these prior studies provide the theoretical foundations for the research question you are investigating. However, depending on the scope of your research topic, prior research studies that are relevant to your thesis might be limited.

When there is very little or no prior research on a specific topic, you may need to develop an entirely new research typology. In this case, discovering a limitation can be considered an important opportunity to identify literature gaps and to present the need for further development in the area of study.

Methods/instruments/techniques used to collect the data

After you complete your analysis of the research findings (in the discussion section), you might realize that the manner in which you have collected the data or the ways in which you have measured variables has limited your ability to conduct a thorough analysis of the results.

For example, you might realize that you should have addressed your survey questions from another viable perspective, or that you were not able to include an important question in the survey. In these cases, you should acknowledge the deficiency or deficiencies by stating a need for future researchers to revise their specific methods for collecting data that includes these missing elements.

Common Limitations of the Researcher(s)

Study limitations that arise from situations relating to the researcher or researchers (whether the direct fault of the individuals or not) should also be addressed and dealt with, and remedies to decrease these limitations—both hypothetically in your study, and practically in future studies—should be proposed.

Limited access to data

If your research involved surveying certain people or organizations, you might have faced the problem of having limited access to these respondents. Due to this limited access, you might need to redesign or restructure your research in a different way. In this case, explain the reasons for limited access and be sure that your finding is still reliable and valid despite this limitation.

Time constraints

Just as students have deadlines to turn in their class papers, academic researchers might also have to meet deadlines for submitting a manuscript to a journal or face other time constraints related to their research (e.g., participants are only available during a certain period; funding runs out; collaborators move to a new institution). The time available to study a research problem and to measure change over time might be constrained by such practical issues. If time constraints negatively impacted your study in any way, acknowledge this impact by mentioning a need for a future study (e.g., a longitudinal study) to answer this research problem.

Conflicts arising from cultural bias and other personal issues

Researchers might hold biased views due to their cultural backgrounds or perspectives of certain phenomena, and this can affect a study’s legitimacy. Also, it is possible that researchers will have biases toward data and results that only support their hypotheses or arguments. In order to avoid these problems, the author(s) of a study should examine whether the way the research problem was stated and the data-gathering process was carried out appropriately.

Steps for Organizing Your Study Limitations Section

When you discuss the limitations of your study, don’t simply list and describe your limitations—explain how these limitations have influenced your research findings. There might be multiple limitations in your study, but you only need to point out and explain those that directly relate to and impact how you address your research questions.

We suggest that you divide your limitations section into three steps: (1) identify the study limitations; (2) explain how they impact your study in detail; and (3) propose a direction for future studies and present alternatives. By following this sequence when discussing your study’s limitations, you will be able to clearly demonstrate your study’s weakness without undermining the quality and integrity of your research.

Step 1. Identify the limitation(s) of the study

- This part should comprise around 10%-20% of your discussion of study limitations.

The first step is to identify the particular limitation(s) that affected your study. There are many possible limitations of research that can affect your study, but you don’t need to write a long review of all possible study limitations. A 200-500 word critique is an appropriate length for a research limitations section. In the beginning of this section, identify what limitations your study has faced and how important these limitations are.

You only need to identify limitations that had the greatest potential impact on: (1) the quality of your findings, and (2) your ability to answer your research question.

Step 2. Explain these study limitations in detail

- This part should comprise around 60-70% of your discussion of limitations.

After identifying your research limitations, it’s time to explain the nature of the limitations and how they potentially impacted your study. For example, when you conduct quantitative research, a lack of probability sampling is an important issue that you should mention. On the other hand, when you conduct qualitative research, the inability to generalize the research findings could be an issue that deserves mention.

Explain the role these limitations played on the results and implications of the research and justify the choice you made in using this “limiting” methodology or other action in your research. Also, make sure that these limitations didn’t undermine the quality of your dissertation .

Step 3. Propose a direction for future studies and present alternatives (optional)

- This part should comprise around 10-20% of your discussion of limitations.

After acknowledging the limitations of the research, you need to discuss some possible ways to overcome these limitations in future studies. One way to do this is to present alternative methodologies and ways to avoid issues with, or “fill in the gaps of” the limitations of this study you have presented. Discuss both the pros and cons of these alternatives and clearly explain why researchers should choose these approaches.

Make sure you are current on approaches used by prior studies and the impacts they have had on their findings. Cite review articles or scientific bodies that have recommended these approaches and why. This might be evidence in support of the approach you chose, or it might be the reason you consider your choices to be included as limitations. This process can act as a justification for your approach and a defense of your decision to take it while acknowledging the feasibility of other approaches.

P hrases and Tips for Introducing Your Study Limitations in the Discussion Section

The following phrases are frequently used to introduce the limitations of the study:

- “There may be some possible limitations in this study.”

- “The findings of this study have to be seen in light of some limitations.”

- “The first is the…The second limitation concerns the…”

- “The empirical results reported herein should be considered in the light of some limitations.”

- “This research, however, is subject to several limitations.”

- “The primary limitation to the generalization of these results is…”

- “Nonetheless, these results must be interpreted with caution and a number of limitations should be borne in mind.”

- “As with the majority of studies, the design of the current study is subject to limitations.”

- “There are two major limitations in this study that could be addressed in future research. First, the study focused on …. Second ….”

For more articles on research writing and the journal submissions and publication process, visit Wordvice’s Academic Resources page.

And be sure to receive professional English editing and proofreading services , including paper editing services , for your journal manuscript before submitting it to journal editors.

Wordvice Resources

Proofreading & Editing Guide

Writing the Results Section for a Research Paper

How to Write a Literature Review

Research Writing Tips: How to Draft a Powerful Discussion Section

How to Captivate Journal Readers with a Strong Introduction

Tips That Will Make Your Abstract a Success!

APA In-Text Citation Guide for Research Writing

Additional Resources

- Diving Deeper into Limitations and Delimitations (PhD student)

- Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper: Limitations of the Study (USC Library)

- Research Limitations (Research Methodology)

- How to Present Limitations and Alternatives (UMASS)

Article References

Pearson-Stuttard, J., Kypridemos, C., Collins, B., Mozaffarian, D., Huang, Y., Bandosz, P.,…Micha, R. (2018). Estimating the health and economic effects of the proposed US Food and Drug Administration voluntary sodium reformulation: Microsimulation cost-effectiveness analysis. PLOS. https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1002551

Xu, W.L, Pedersen, N.L., Keller, L., Kalpouzos, G., Wang, H.X., Graff, C,. Fratiglioni, L. (2015). HHEX_23 AA Genotype Exacerbates Effect of Diabetes on Dementia and Alzheimer Disease: A Population-Based Longitudinal Study. PLOS. Retrieved from https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1001853

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Meryl Brodsky : Communication and Information Studies

Hannah Chapman Tripp : Biology, Neuroscience

Carolyn Cunningham : Human Development & Family Sciences, Psychology, Sociology

Larayne Dallas : Engineering

Janelle Hedstrom : Special Education, Curriculum & Instruction, Ed Leadership & Policy

Susan Macicak : Linguistics

Imelda Vetter : Dell Medical School

For help in other subject areas, please see the guide to library specialists by subject .

Periodically, UT Libraries runs a workshop covering the basics and library support for literature reviews. While we try to offer these once per academic year, we find providing the recording to be helpful to community members who have missed the session. Following is the most recent recording of the workshop, Conducting a Literature Review. To view the recording, a UT login is required.

- October 26, 2022 recording

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2022 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

Published on 22 February 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 7 June 2022.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research.

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarise sources – it analyses, synthesises, and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Why write a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1: search for relevant literature, step 2: evaluate and select sources, step 3: identify themes, debates and gaps, step 4: outline your literature review’s structure, step 5: write your literature review, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a dissertation or thesis, you will have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position yourself in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your dissertation addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

You might also have to write a literature review as a stand-alone assignment. In this case, the purpose is to evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of scholarly debates around a topic.

The content will look slightly different in each case, but the process of conducting a literature review follows the same steps. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research objectives and questions .

If you are writing a literature review as a stand-alone assignment, you will have to choose a focus and develop a central question to direct your search. Unlike a dissertation research question, this question has to be answerable without collecting original data. You should be able to answer it based only on a review of existing publications.

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research topic. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list if you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can use boolean operators to help narrow down your search:

Read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

To identify the most important publications on your topic, take note of recurring citations. If the same authors, books or articles keep appearing in your reading, make sure to seek them out.

You probably won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on the topic – you’ll have to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your questions.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models and methods? Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- How does the publication contribute to your understanding of the topic? What are its key insights and arguments?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible, and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can find out how many times an article has been cited on Google Scholar – a high citation count means the article has been influential in the field, and should certainly be included in your literature review.

The scope of your review will depend on your topic and discipline: in the sciences you usually only review recent literature, but in the humanities you might take a long historical perspective (for example, to trace how a concept has changed in meaning over time).

Remember that you can use our template to summarise and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using!

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It’s important to keep track of your sources with references to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography, where you compile full reference information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

You can use our free APA Reference Generator for quick, correct, consistent citations.

To begin organising your literature review’s argument and structure, you need to understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly-visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat – this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organising the body of a literature review. You should have a rough idea of your strategy before you start writing.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarising sources in order.

Try to analyse patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organise your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text, your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

If you are writing the literature review as part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate your central problem or research question and give a brief summary of the scholarly context. You can emphasise the timeliness of the topic (“many recent studies have focused on the problem of x”) or highlight a gap in the literature (“while there has been much research on x, few researchers have taken y into consideration”).

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, make sure to follow these tips:

- Summarise and synthesise: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole.

- Analyse and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole.

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources.

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transitions and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts.

In the conclusion, you should summarise the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasise their significance.

If the literature review is part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate how your research addresses gaps and contributes new knowledge, or discuss how you have drawn on existing theories and methods to build a framework for your research. This can lead directly into your methodology section.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarise yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, June 07). What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 2 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, what is a theoretical framework | a step-by-step guide, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

Dissertations - Skills Guide

- Where to start

- Research Proposal

- Ethics Form

- Primary Research

Literature Review

- Methodology

- Downloadable Resources

- Further Reading

What is it?

Literature reviews involve collecting information from literature that is already available, similar to a long essay. It is a written argument that builds a case from previous research (Machi and McEvoy, 2012). Every dissertation should include a literature review, but a dissertation as a whole can be a literature review. In this section we discuss literature reviews for the whole dissertation.

What are the benefits of a literature review?

There are advantages and disadvantages to any approach. The advantages of conducting a literature review include accessibility, deeper understanding of your chosen topic, identifying experts and current research within that area, and answering key questions about current research. The disadvantages might include not providing new information on the subject and, depending on the subject area, you may have to include information that is out of date.

How do I write it?

A literature review is often split into chapters, you can choose if these chapters have titles that represent the information within them, or call them chapter 1, chapter 2, ect. A regular format for a literature review is:

Introduction (including methodology)

This particular example is split into 6 sections, however it may be more or less depending on your topic.

Literature Reviews Further Reading

- << Previous: Primary Research

- Next: Methodology >>

- Last Updated: Oct 18, 2023 9:32 AM

- URL: https://libguides.derby.ac.uk/c.php?g=690330

How To Write An A-Grade Literature Review

3 straightforward steps (with examples) + free template.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | October 2019

Quality research is about building onto the existing work of others , “standing on the shoulders of giants”, as Newton put it. The literature review chapter of your dissertation, thesis or research project is where you synthesise this prior work and lay the theoretical foundation for your own research.

Long story short, this chapter is a pretty big deal, which is why you want to make sure you get it right . In this post, I’ll show you exactly how to write a literature review in three straightforward steps, so you can conquer this vital chapter (the smart way).

Overview: The Literature Review Process

- Understanding the “ why “

- Finding the relevant literature

- Cataloguing and synthesising the information

- Outlining & writing up your literature review

- Example of a literature review

But first, the “why”…

Before we unpack how to write the literature review chapter, we’ve got to look at the why . To put it bluntly, if you don’t understand the function and purpose of the literature review process, there’s no way you can pull it off well. So, what exactly is the purpose of the literature review?

Well, there are (at least) four core functions:

- For you to gain an understanding (and demonstrate this understanding) of where the research is at currently, what the key arguments and disagreements are.

- For you to identify the gap(s) in the literature and then use this as justification for your own research topic.

- To help you build a conceptual framework for empirical testing (if applicable to your research topic).

- To inform your methodological choices and help you source tried and tested questionnaires (for interviews ) and measurement instruments (for surveys ).

Most students understand the first point but don’t give any thought to the rest. To get the most from the literature review process, you must keep all four points front of mind as you review the literature (more on this shortly), or you’ll land up with a wonky foundation.

Okay – with the why out the way, let’s move on to the how . As mentioned above, writing your literature review is a process, which I’ll break down into three steps:

- Finding the most suitable literature

- Understanding , distilling and organising the literature

- Planning and writing up your literature review chapter

Importantly, you must complete steps one and two before you start writing up your chapter. I know it’s very tempting, but don’t try to kill two birds with one stone and write as you read. You’ll invariably end up wasting huge amounts of time re-writing and re-shaping, or you’ll just land up with a disjointed, hard-to-digest mess . Instead, you need to read first and distil the information, then plan and execute the writing.

Step 1: Find the relevant literature

Naturally, the first step in the literature review journey is to hunt down the existing research that’s relevant to your topic. While you probably already have a decent base of this from your research proposal , you need to expand on this substantially in the dissertation or thesis itself.