Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 10 December 2020

Effect of internet use and electronic game-play on academic performance of Australian children

- Md Irteja Islam 1 , 2 ,

- Raaj Kishore Biswas 3 &

- Rasheda Khanam 1

Scientific Reports volume 10 , Article number: 21727 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

70k Accesses

23 Citations

32 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

- Risk factors

This study examined the association of internet use, and electronic game-play with academic performance respectively on weekdays and weekends in Australian children. It also assessed whether addiction tendency to internet and game-play is associated with academic performance. Overall, 1704 children of 11–17-year-olds from young minds matter (YMM), a cross-sectional nationwide survey, were analysed. The generalized linear regression models adjusted for survey weights were applied to investigate the association between internet use, and electronic-gaming with academic performance (measured by NAPLAN–National standard score). About 70% of the sample spent > 2 h/day using the internet and nearly 30% played electronic-games for > 2 h/day. Internet users during weekdays (> 4 h/day) were less likely to get higher scores in reading and numeracy, and internet use on weekends (> 2–4 h/day) was positively associated with academic performance. In contrast, 16% of electronic gamers were more likely to get better reading scores on weekdays compared to those who did not. Addiction tendency to internet and electronic-gaming is found to be adversely associated with academic achievement. Further, results indicated the need for parental monitoring and/or self-regulation to limit the timing and duration of internet use/electronic-gaming to overcome the detrimental effects of internet use and electronic game-play on academic achievement.

Similar content being viewed by others

The impact of digital media on children’s intelligence while controlling for genetic differences in cognition and socioeconomic background

Adaption and implementation of the engage programme within the early childhood curriculum

The role of game genres and gamers’ communication networks in perceived learning

Introduction.

Over the past two decades, with the proliferation of high-tech devices (e.g. Smartphone, tablets and computers), both the internet and electronic games have become increasingly popular with people of all ages, but particularly with children and adolescents 1 , 2 , 3 . Recent estimates have shown that one in three under-18-year-olds across the world uses the Internet, and 75% of adolescents play electronic games daily in developed countries 4 , 5 , 6 . Studies in the United States reported that adolescents are occupied with over 11 h a day with modern electronic media such as computer/Internet and electronic games, which is more than they spend in school or with friends 7 , 8 . In Australia, it is reported that about 98% of children aged 15–17 years are among Internet users and 98% of adolescents play electronic games, which is significantly higher than the USA and Europe 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 .

In recent times, the Internet and electronic games have been regarded as important, not just for better results at school, but also for self-expression, sociability, creativity and entertainment for children and adolescents 13 , 14 . For instance, 88% of 12–17 year-olds in the USA considered the Internet as a useful mechanism for making progress in school 15 , and similarly, electronic gaming in children and adolescents may assist in developing skills such as decision-making, smart-thinking and coordination 3 , 15 .

On the other hand, evidence points to the fact that the use of the Internet and electronic games is found to have detrimental effects such as reduced sleeping time, behavioural problems (e.g. low self-esteem, anxiety, depression), attention problems and poor academic performance in adolescents 1 , 5 , 12 , 16 . In addition, excessive Internet usage and increased electronic gaming are found to be addictive and may cause serious functional impairment in the daily life of children and adolescents 1 , 12 , 13 , 16 . For example, the AU Kids Online survey 17 reported that 50% of Australian children were more likely to experience behavioural problems associated with Internet use compared to children from 25 European countries (29%) surveyed in the EU Kids Online study 18 , which is alarming 12 . These mixed results require an urgent need of understanding the effect of the Internet use and electronic gaming on the development of children and adolescents, particularly on their academic performance.

Despite many international studies and a smaller number in Australia 12 , several systematic limitations remain in the existing literature, particularly regarding the association of academic performance with the use of Internet and electronic games in children and adolescents 13 , 16 , 19 . First, the majority of the earlier studies have either relied on school grades or children’s self assessments—which contain an innate subjectivity by the assessor; and have not considered the standardized tests of academic performance 16 , 20 , 21 , 22 . Second, most previous studies have tested the hypothesis in the school-based settings instead of canvassing the whole community, and cannot therefore adjust for sociodemographic confounders 9 , 16 . Third, most studies have been typically limited to smaller sample sizes, which might have reduced the reliability of the results 9 , 16 , 23 .

By considering these issues, this study aimed to investigate the association of internet usage and electronic gaming on a standardized test of academic performance—NAPLAN (The National Assessment Program—Literacy and Numeracy) among Australian adolescents aged 11–17 years using nationally representative data from the Second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing—Young Minds Matter (YMM). It is hypothesized that the findings of this study will provide a population-wide, contextual view of excessive Internet use and electronic games played separately on weekdays and weekends by Australian adolescents, which may be beneficial for evidence-based policies.

Subject demographics

Respondents who attended gave NAPLAN in 2008 (N = 4) and 2009 (N = 29) were removed from the sample due to smaller sample size, as later years (2010–2015) had over 100 samples yearly. The NAPLAN scores from 2008 might not align with a survey conducted in 2013. Further missing cases were deleted with the assumption that data were missing at random for unbiased estimates, which is common for large-scale surveys 24 . From the initial survey of 2967 samples, 1704 adolescents were sampled for this study.

The sample characteristics were displayed in Table 1 . For example, distribution of daily average internet use was checked, showing that over 50% of the sampled adolescents spent 2–4 h on internet (Table 1 ). Although all respondents in the survey used internet, nearly 21% of them did not play any electronic games in a day and almost one in every three (33%) adolescents played electronic games beyond the recommended time of 2 h per day. Girls had more addictive tendency to internet/game-play in compare to boys.

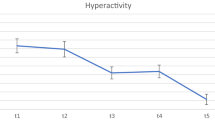

The mean scores for the three NAPLAN tests scores (reading, writing and numeracy) ranged from 520 to 600. A gradual decline in average NAPLAN tests scores (reading, writing and numeracy) scores were observed for internet use over 4 h during weekdays, and over 3 h during weekends (Table 2 ). Table 2 also shows that adolescents who played no electronic games at all have better scores in writing compared to those who play electronic games. Moreover, Table 2 shows no particular pattern between time spent on gaming and NAPLAN reading and numeracy scores. Among the survey samples, 308 adolescents were below the national standard average.

Internet use and academic performance

Our results show that internet (non-academic use) use during weekdays, especially more than 4 h, is negatively associated with academic performance (Table 3 ). For internet use during weekdays, all three models showed a significant negative association between time spent on internet and NAPLAN reading and numeracy scores. For example, in Model 1, adolescents who spent over 4 h on internet during weekdays are 15% and 17% less likely to get higher reading and numeracy scores respectively compared to those who spend less than 2 h. Similar results were found in Model 2 and 3 (Table 3 ), when we adjusted other confounders. The variable addiction tendency to internet was found to be negatively associated with NAPLAN results. The adolescents who had internet addiction were 17% less and 14% less likely to score higher in reading and numeracy respectively than those without such problematic behaviour.

Internet use during weekends showed a positive association with academic performance (Table 4 ). For example, Model 1 in Table 4 shows that internet use during weekends was significant for reading, writing and national standard scores. Youths who spend around 2–4 h and over 4 h on the internet during weekends were 21% and 15% more likely to get a higher reading scores respectively compared to those who spend less than 2 h (Model 1, Table 4 ). Similarly, in model 3, where the internet addiction of adolescents was adjusted, adolescents who spent 2–4 h on internet were 1.59 times more likely to score above the national standard. All three models of Table 4 confirmed that adolescents who spent 2–4 h on the internet during weekends are more likely to achieve better reading and writing scores and be at or above national standard compared to those who used the internet for less than 2 h. Numeracy scores were unlikely to be affected by internet use. The results obtained from Model 3 should be treated as robust, as this is the most comprehensive model that accounts for unobserved characteristics. The addiction tendency to internet/game-play variable showed a negative association with academic performance, but this is only significant for numeracy scores.

Electronic gaming and academic performance

Time spent on electronic gaming during weekdays had no effect on the academic performance of writing and language but had significant association with reading scores (Model 2, Table 5 ). Model 2 of Table 5 shows that adolescents who spent 1–2 h on gaming during weekdays were 13% more likely to get higher reading scores compared to those who did not play at all. It was an interesting result that while electronic gaming during weekdays tended to show a positive effect on reading scores, internet use during weekdays showed a negative effect. Addiction tendency to internet/game-play had a negative effect; the adolescents who were addicted to the internet were 14% less likely to score more highly in reading than those without any such behaviour.

All three models from Table 6 confirm that time spent on electronic gaming over 2 h during weekends had a positive effect on readings scores. For example, the results of Model 3 (Table 6 ) showed that adolescents who spent more than 2 h on electronic gaming during weekdays were 16% more likely to have better reading scores compared to adolescents who did not play games at all. Playing electronic games during weekends was not found to be statistically significant for writing and numeracy scores and national standard scores, although the odds ratios were positive. The results from all tables confirm that addiction tendency to internet/gaming is negatively associated with academic performance, although the variable is not always statistically significant.

Building on past research on the effect of the internet use and electronic gaming in adolescents, this study examined whether Internet use and playing electronic games were associated with academic performance (i.e. reading, writing and numeracy) using a standardized test of academic performance (i.e. NAPLAN) in a nationally representative dataset in Australia. The findings of this study question the conventional belief 9 , 25 that academic performance is negatively associated with internet use and electronic games, particularly when the internet is used for non-academic purpose.

In the current hi-tech world, many developed countries (e.g. the USA, Canada and Australia) have recommended that 5–17 year-olds limit electronic media (e.g. internet, electronic games) to 2 h per day for entertainment purposes, with concerns about the possible negative consequences of excessive use of electronic media 14 , 26 . However, previous research has often reported that children and adolescents spent more than the recommended time 26 . The present study also found similar results, that is, that about 70% of the sampled adolescents aged 11–17 spent more than 2 h per day on the Internet and nearly 30% spent more than 2-h on electronic gaming in a day. This could be attributed to the increased availability of computers/smart-phones and the internet among under-18s 12 . For instance, 97% of Australian households with children aged less than 15 years accessed internet at home in 2016–2017 10 ; as a result, policymakers recommended that parents restrict access to screens (e.g. Internet and electronic games) in children’s bedrooms, monitor children using screens, share screen hours with their children, and to act as role models by reducing their own screen time 14 .

This research has drawn attention to the fact that the average time spent using the internet, which is often more than 4 h during weekdays tends to be negatively associated with academic performance, especially a lower reading and numeracy score, while internet use of more than 2 h during weekends is positively associated with academic performance, particularly having a better reading and writing score and above national standard score. By dividing internet use and gaming by weekdays and weekends, this study find an answer to the mixed evidence found in previous literature 9 . The results of this study clearly show that the non-academic use of internet during weekdays, particularly, spending more than 4 h on internet is harmful for academic performance, whereas, internet use on the weekends is likely to incur a positive effect on academic performance. This result is consistent with a USA study that reported that internet use is positively associated with improved reading skills and higher scores on standardized tests 13 , 27 . It is also reported in the literature that academic performance is better among moderate users of the internet compared to non-users or high level users 13 , 27 , which was in line with the findings of this study. This may be due to the fact that the internet is predominantly a text-based format in which the internet users need to type and read to access most websites effectively 13 . The results of this study indicated that internet use is not harmful to academic performance if it is used moderately, especially, if ensuring very limited use on weekdays. The results of this study further confirmed that timing (weekdays or weekends) of internet use is a factor that needs to be considered.

Regarding electronic gaming, interestingly, the study found that the average time of gaming either in weekdays or weekends is positively associated with academic performance especially for reading scores. These results contradicted previous literatures 1 , 13 , 19 , 27 that have reported negative correlation between electronic games and educational performance in high-school children. The results of this study were consistent with studies conducted in the USA, Europe and other countries that claimed a positive correlation between gaming and academic performance, especially in numeracy and reading skills 28 , 29 . This is may be due to the fact that the instructions for playing most of the electronic games are text-heavy and many electronic games require gamers to solve puzzles 9 , 30 . The literature also found that playing electronic games develops cognitive skills (e.g. mental rotation abilities, dexterity), which can be attributable to better academic achievement 31 , 32 .

Consistent with previous research findings 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , the study also found that adolescents who had addiction tendency to internet usage and/or electronic gaming were less likely to achieve higher scores in reading and numeracy compared to those who had not problematic behaviour. Addiction tendency to Internet/gaming among adolescents was found to be negatively associated with overall academic performance compared to those who were not having addiction tendency, although the variables were not always statistically significant. This is mainly because adolescents’ skipped school and missed classes and tuitions, and provide less effort to do homework due to addictive internet usage and electronic gaming 19 , 35 . The results of this study indicated that parental monitoring and/ or self-regulation (by the users) regarding the timing and intensity of internet use/gaming are essential to outweigh any negative effect of internet use and gaming on academic performance.

Although the present study uses a large nationally representative sample and advances prior research on the academic performance among adolescents who reported using the internet and playing electronic games, the findings of this study also have some limitations that need to be addressed. Firstly, adolescents who reported on the internet use and electronic games relied on self-reported child data without any screening tests or any external validation and thus, results may be overestimated or underestimated. Second, the study primarily addresses the internet use and electronic games as distinct behaviours, as the YMM survey gathered information only on the amount of time spent on internet use and electronic gaming, and included only a few questions related to addiction due to resources and time constraints and did not provide enough information to medically diagnose internet/gaming addiction. Finally, the cross-sectional research design of the data outlawed evaluation of causality and temporality of the observed association of internet use and electronic gaming with the academic performance in adolescents.

This study found that the average time spent on the internet on weekends and electronic gaming (both in weekdays and weekends) is positively associated with academic performance (measured by NAPLAN) of Australian adolescents. However, it confirmed a negative association between addiction tendency (internet use or electronic gaming) and academic performance; nonetheless, most of the adolescents used the internet and played electronic games more than the recommended 2-h limit per day. The study also revealed that further research is required on the development and implementation of interventions aimed at improving parental monitoring and fostering users’ self-regulation to restrict the daily usage of the internet and/or electronic games.

Data description

Young minds matter (YMM) was an Australian nationwide cross-sectional survey, on children aged 4–17 years conducted in 2013–2014 37 . Out of the initial 76,606 households approached, a total of 6,310 parents/caregivers (eligible household response rate 55%) of 4–17 year-old children completed a structured questionnaire via face to face interview and 2967 children aged 11–17 years (eligible children response rate 89%) completed a computer-based self-reported questionnaire privately at home 37 .

Area based sampling was used for the survey. A total of 225 Statistical Area 1 (defined by Australian Bureau of Statistics) areas were selected based on the 2011 Census of Population and Housing. They were stratified by state/territory and by metropolitan versus non-metropolitan (rural/regional) to ensure proportional representation of geographic areas across Australia 38 . However, a small number of samples were excluded, based on most remote areas, homeless children, institutional care and children living in households where interviews could not be conducted in English. The details of the survey and methodology used in the survey can be found in Lawrence et al. 37 .

Following informed consent (both written and verbal) from the primary carers (parents/caregivers), information on the National Assessment Program—Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) of the children and adolescents were also added to the YMM dataset. The YMM survey is ethically approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Western Australia and by the Australian Government Department of Health. In addition, the authors of this study obtained a written approval from Australian Data Archive (ADA) Dataverse to access the YMM dataset. All the researches were done in accordance with relevant ADA Dataverse guidelines and policy/regulations in using YMM datasets.

Outcome variables

The NAPLAN, conducted annually since 2008, is a nationwide standardized test of academic performance for all Australian students in Years 3, 5, 7 and 9 to assess their skills in reading, writing numeracy, grammar and spelling 39 , 40 . NAPLAN scores from 2010 to 2015, reported by YMM, were used as outcome variables in the models; while NAPLAN data of 2008 (N = 4) and 2009 (N = 29) were excluded for this study in order to reduce the time lag between YMM survey and the NAPLAN test. The NAPLAN gives point-in-time standardized scores, which provide the scope to compare children’s academic performance over time 40 , 41 . The NAPLAN tests are one component of the evaluation and grading phase of each school, and do not substitute for the comprehensive, consistent evaluations provided by teachers on the performance of each student 39 , 41 . All four domains—reading, writing, numeracy and language conventions (grammar and spelling) are in continuous scales in the dataset. The scores are given based on a series of tests; details can be found in 42 . The current study uses only reading, writing and numeracy scores to measure academic performance.

In this study, the National standard score is a combination of three variables: whether the student meets the national standard in reading, writing and numeracy. Based on national average score, a binary outcome variable is also generated. One category is ‘below standard’ if a child scores at least one standard deviation (one below scores) from the national standard in reading, writing and numeracy, and the rest is ‘at/above standard’.

Independent variables

Internet use and electronic gaming.

In the YMM survey, owing to the scope of the survey itself, an extensive set of questions about internet usage and electronic gaming could not be included. Internet usage omitted the time spent in academic purposes and/or related activities. Playing electronic games included playing games on a gaming console (e.g. PlayStation, Xbox, or similar console ) online or using a computer, or mobile phone, or a handled device 12 . The primary independent covariates were average internet use per day and average electronic game-play in hours per day. A combination of hours on weekdays and weekends was separately used in the models. These variables were based on a self-assessed questionnaire where the youths were asked questions regarding daily time spent on the Internet and electronic game-play, specifically on either weekends or weekdays. Since, internet use/game-play for a maximum of 2 h/day is recommended for children and adolescents aged between 5 and 17 years in many developed countries including Australia 14 , 26 ; therefore, to be consistent with the recommended time we preferred to categorize both the time variables of internet use and gaming into three groups with an interval of 2 h each. Internet use was categorized into three groups: (a) ≤ 2 h), (b) 2–4 h, and (c) > 4 h. Similar questions were asked for game-play h. The sample distribution for electronic game-play was skewed; therefore, this variable was categorized into three groups: (a) no game-play (0 h), (b) 1–2 h, and (c) > 2 h.

Other covariates

Family structure and several sociodemographic variables were used in the models to adjust for the differences in individual characteristics, parental inputs and tastes, household characteristics and place of residence. Individual characteristics included age (continuous) and sex of the child (boys, girls) and addiction tendency to internet use and/or game-play of the adolescent. Addiction tendency to internet/game-play was a binary independent variable. It was a combination of five behavioural questions relating to: whether the respondent avoided eating/sleeping due to internet use or game-play; feels bothered when s/he cannot access internet or play electronic games; keeps using internet or playing electronic games even when s/he is not really interested; spends less time with family/friends or on school works due to internet use or game-play; and unsuccessfully tries to spend less time on the internet or playing electronic games. There were four options for each question: never/almost never; not very often; fairly often; and very often. A binary covariate was simulated, where if any four out of five behaviours were reported as for example, fairly often or very often, then it was considered that the respondent had addictive tendency.

Household characteristics included household income (low, medium, high), family type (original, step, blended, sole parent/primary carer, other) 43 and remoteness (major cities, inner regional, outer regional, remote/very remote). Parental inputs and taste included education of primary carer (bachelor, diploma, year 10/11), primary carer’s likelihood of serious mental illness (K6 score -likely; not likely); primary carer’s smoking status (no, yes); and risk of alcoholic related harm by the primary carer (risky, none).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of the sample and distributions of the outcome variables were initially assessed. Based on these distributions, the categorization of outcome variables was conducted, as mentioned above. For formal analysis, generalized linear regression models (GLMs) 44 were used, adjusting for the survey weights, which allowed for generalization of the findings. As NAPLAN scores of three areas—reading, writing and numeracy—were continuous variables, linear models were fitted to daily average internet time and electronic game play time. The scores were standardized (mean = 0, SD = 1) for model fitness. The binary logistic model was fitted for the dichotomized national standard outcome variable. Separate models were estimated for internet and electronic gaming on weekends and weekdays.

We estimated three different models, where models varied based on covariates used to adjust the GLMs. Model 1 was adjusted for common sociodemographic factors including age and sex of the child, household income, education of primary carer’s and family type 43 . However, the results of this model did not account for some unobserved household characteristics (e.g. taste, preferences) that are unobserved to the researcher and are arguably correlated with potential outcomes. The effects of unobserved characteristics were reduced by using a comprehensive set of observable characteristics 45 , 46 that were available in YMM data. The issue of unobserved characteristics was addressed by estimating two additional models that include variables by including household characteristics such as parental taste, preference and inputs, and child characteristics in the model. In addition to the variables in Model 1, Model 2 included remoteness, primary carer’s mental health status, smoking status and risk of alcoholic related harm by the primary carer. Model 3 further included internet/game addiction of the adolescent in addition to all the covariates in Model 2. Model 3 was expected to account for a child’s level of unobserved characteristics as the children who were addicted to internet/games were different from others. The model will further show how academic performance is affected by internet/game addiction. The correlation among the variables ‘internet/game addiction’ and ‘internet use’ and ‘gaming’ (during weekdays and weekends) were also assessed, and they were less than 0.5. Multicollinearity was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF), which was under 5 for all models, suggesting no multicollinearity 47 .

p value below the threshold of 0.05 was considered the threshold of significance. All analysis was conducted in R (version 3.6.1). R-package survey (version 3.37) was used for modelling which is suited for complex survey samples 48 .

Data availability

The authors declare that they do not have permission to share dataset. However, the datasets of Young Minds Matter (YMM) survey data is available at the Australian Data Archive (ADA) Dataverse on request ( https://doi.org/10.4225/87/LCVEU3 ).

Wang, C. -W., Chan, C. L., Mak, K. -K., Ho, S. -Y., Wong, P. W. & Ho, R. T. Prevalence and correlates of video and Internet gaming addiction among Hong Kong adolescents: a pilot study. Sci. World J . 2014 (2014).

Anderson, E. L., Steen, E. & Stavropoulos, V. Internet use and problematic internet use: a systematic review of longitudinal research trends in adolescence and emergent adulthood. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 22 , 430–454 (2017).

Article Google Scholar

Oliveira, M. P. MTd. et al. Use of internet and electronic games by adolescents at high social risk. Trends Psychol. 25 , 1167–1183 (2017).

Google Scholar

UNICEF. Children in a digital world. United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) (2017)

King, D. L. et al. The impact of prolonged violent video-gaming on adolescent sleep: an experimental study. J. Sleep Res. 22 , 137–143 (2013).

Byrne, J. & Burton, P. Children as Internet users: how can evidence better inform policy debate?. J. Cyber Policy. 2 , 39–52 (2017).

Council, O. Children, adolescents, and the media. Pediatrics 132 , 958 (2013).

Paulus, F. W., Ohmann, S., Von Gontard, A. & Popow, C. Internet gaming disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 60 , 645–659 (2018).

Posso, A. Internet usage and educational outcomes among 15-year old Australian students. Int J Commun 10 , 26 (2016).

ABS. 8146.0—Household Use of Information Technology, Australia, 2016–2017 (2018).

Brand, J. E. Digital Australia 2018 (Interactive Games & Entertainment Association (IGEA), Eveleigh, 2017).

Rikkers, W., Lawrence, D., Hafekost, J. & Zubrick, S. R. Internet use and electronic gaming by children and adolescents with emotional and behavioural problems in Australia–results from the second Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. BMC Public Health 16 , 399 (2016).

Jackson, L. A., Von Eye, A., Witt, E. A., Zhao, Y. & Fitzgerald, H. E. A longitudinal study of the effects of Internet use and videogame playing on academic performance and the roles of gender, race and income in these relationships. Comput. Hum. Behav. 27 , 228–239 (2011).

Yu, M. & Baxter, J. Australian children’s screen time and participation in extracurricular activities. Ann. Stat. Rep. 2016 , 99 (2015).

Rainie, L. & Horrigan, J. A decade of adoption: How the Internet has woven itself into American life. Pew Internet and American Life Project . 25 (2005).

Drummond, A. & Sauer, J. D. Video-games do not negatively impact adolescent academic performance in science, mathematics or reading. PLoS ONE 9 , e87943 (2014).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Green, L., Olafsson, K., Brady, D. & Smahel, D. Excessive Internet use among Australian children (2012).

Livingstone, S. EU kids online. The international encyclopedia of media literacy . 1–17 (2019).

Wright, J. The effects of video game play on academic performance. Mod. Psychol. Stud. 17 , 6 (2011).

Gentile, D. A., Lynch, P. J., Linder, J. R. & Walsh, D. A. The effects of violent video game habits on adolescent hostility, aggressive behaviors, and school performance. J. Adolesc. 27 , 5–22 (2004).

Rosenthal, R. & Jacobson, L. Pygmalion in the classroom. Urban Rev. 3 , 16–20 (1968).

Willoughby, T. A short-term longitudinal study of Internet and computer game use by adolescent boys and girls: prevalence, frequency of use, and psychosocial predictors. Dev. Psychol. 44 , 195 (2008).

Weis, R. & Cerankosky, B. C. Effects of video-game ownership on young boys’ academic and behavioral functioning: a randomized, controlled study. Psychol. Sci. 21 , 463–470 (2010).

Howell, D. C. The treatment of missing data. The Sage handbook of social science methodology . 208–224 (2007).

Terry, M. and Malik, A. Video gaming as a factor that affects academic performance in grade nine. Online Submission (2018).

Houghton, S. et al. Virtually impossible: limiting Australian children and adolescents daily screen based media use. BMC Public Health. 15 , 5 (2015).

Jackson, L. A., Von Eye, A., Fitzgerald, H. E., Witt, E. A. & Zhao, Y. Internet use, videogame playing and cell phone use as predictors of children’s body mass index (BMI), body weight, academic performance, and social and overall self-esteem. Comput. Hum. Behav. 27 , 599–604 (2011).

Bowers, A. J. & Berland, M. Does recreational computer use affect high school achievement?. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 61 , 51–69 (2013).

Wittwer, J. & Senkbeil, M. Is students’ computer use at home related to their mathematical performance at school?. Comput. Educ. 50 , 1558–1571 (2008).

Jackson, L. A. et al. Does home internet use influence the academic performance of low-income children?. Dev. Psychol. 42 , 429 (2006).

Barlett, C. P., Anderson, C. A. & Swing, E. L. Video game effects—confirmed, suspected, and speculative: a review of the evidence. Simul. Gaming 40 , 377–403 (2009).

Suziedelyte, A. Can video games affect children's cognitive and non-cognitive skills? UNSW Australian School of Business Research Paper (2012).

Chiu, S.-I., Lee, J.-Z. & Huang, D.-H. Video game addiction in children and teenagers in Taiwan. CyberPsychol. Behav. 7 , 571–581 (2004).

Skoric, M. M., Teo, L. L. C. & Neo, R. L. Children and video games: addiction, engagement, and scholastic achievement. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 12 , 567–572 (2009).

Leung, L. & Lee, P. S. Impact of internet literacy, internet addiction symptoms, and internet activities on academic performance. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 30 , 403–418 (2012).

Xin, M. et al. Online activities, prevalence of Internet addiction and risk factors related to family and school among adolescents in China. Addict. Behav. Rep. 7 , 14–18 (2018).

PubMed Google Scholar

Lawrence, D., Johnson, S., Hafekost, J., et al. The mental health of children and adolescents: report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing (2015).

Hafekost, J. et al. Methodology of young minds matter: the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 50 , 866–875 (2016).

Australian Curriculum ARAA. National Assessment Program Literacy and Numeracy: Achievement in Reading, Persuasive Writing, Language Conventions and Numeracy: National Report for 2011 . Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (2011).

Daraganova, G., Edwards, B. & Sipthorp, M. Using National Assessment Program Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) Data in the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) . Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (2013).

NAP. NAPLAN (2016).

Australian Curriculum ARAA. National report on schooling in Australia 2009. Ministerial Council for Education, Early Childhood Development and Youth… (2009).

Vu, X.-B.B., Biswas, R. K., Khanam, R. & Rahman, M. Mental health service use in Australia: the role of family structure and socio-economic status. Children Youth Serv. Rev. 93 , 378–389 (2018).

McCullagh, P. Generalized Linear Models (Routledge, Abingdon, 2019).

Book Google Scholar

Gregg, P., Washbrook, E., Propper, C. & Burgess, S. The effects of a mother’s return to work decision on child development in the UK. Econ. J. 115 , F48–F80 (2005).

Khanam, R. & Nghiem, S. Family income and child cognitive and noncognitive development in Australia: does money matter?. Demography 53 , 597–621 (2016).

Kutner, M. H., Nachtsheim, C. J., Neter, J. & Li, W. Applied Linear Statistical Models (McGraw-Hill Irwin, New York, 2005).

Lumley T. Package ‘survey’. 3 , 30–33 (2015).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the University of Western Australia, Roy Morgan Research, the Australian Government Department of Health for conducting the survey, and the Australian Data Archive for giving access to the YMM survey dataset. The authors also would like to thank Dr Barbara Harmes for proofreading the manuscript.

This research did not receive any specific Grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Health Research and School of Commerce, University of Southern Queensland, Workstation 15, Room T450, Block T, Toowoomba, QLD, 4350, Australia

Md Irteja Islam & Rasheda Khanam

Maternal and Child Health Division, International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b), Mohakhali, Dhaka, 1212, Bangladesh

Md Irteja Islam

Transport and Road Safety (TARS) Research Centre, School of Aviation, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, 2052, Australia

Raaj Kishore Biswas

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

M.I.I.: Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Investigation, Writing—Original draft preparation, Writing—Reviewing and Editing. R.K.B.: Methodology, Software, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing—Original draft preparation. R.K.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Md Irteja Islam .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Islam, M.I., Biswas, R.K. & Khanam, R. Effect of internet use and electronic game-play on academic performance of Australian children. Sci Rep 10 , 21727 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-78916-9

Download citation

Received : 28 August 2020

Accepted : 02 December 2020

Published : 10 December 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-78916-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

I want to play a game: examining sex differences in the effects of pathological gaming, academic self-efficacy, and academic initiative on academic performance in adolescence.

- Sara Madeleine Kristensen

- Magnus Jørgensen

Education and Information Technologies (2024)

Measurement Invariance of the Lemmens Internet Gaming Disorder Scale-9 Across Age, Gender, and Respondents

- Iulia Maria Coșa

- Anca Dobrean

- Robert Balazsi

Psychiatric Quarterly (2024)

Academic and Social Behaviour Profile of the Primary School Students who Possess and Play Video Games

- E. Vázquez-Cano

- J. M. Ramírez-Hurtado

- C. Pascual-Moscoso

Child Indicators Research (2023)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous

- Next chapter >

1 Introduction to Games User Research

- Published: January 2018

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter provides an introduction to the field of Games User Research (GUR) and to the present book. GUR is an interdisciplinary field of practice and research concerned with ensuring the optimal quality of usability and user experience in digital games. GUR inevitably involves any aspect of a video game that players interface with, directly or indirectly. This book aims to provide the foundational, accessible, go-to resource for people interested in GUR. It is a community-driven effort—it is written by passionate professionals and researchers in the GUR community as a handbook and guide for everyone interested in user research and games. We aim to provide the most comprehensive overview from an applied perspective, for a person new to GUR, but which is also useful for experienced user researchers.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Massively multiplayer online games and well-being: a systematic literature review.

- 1 School of Health and Behavioural Sciences, University of the Sunshine Coast, Maroochydore, QLD, Australia

- 2 Institute of Health and Sports, Victoria University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 3 School of Psychology, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

- 4 Thompson Institute, University of the Sunshine Coast, Maroochydore, QLD, Australia

Background: Massively multiplayer online games (MMOs) evolve online, whilst engaging large numbers of participants who play concurrently. Their online socialization component is a primary reason for their high popularity. Interestingly, the adverse effects of MMOs have attracted significant attention compared to their potential benefits.

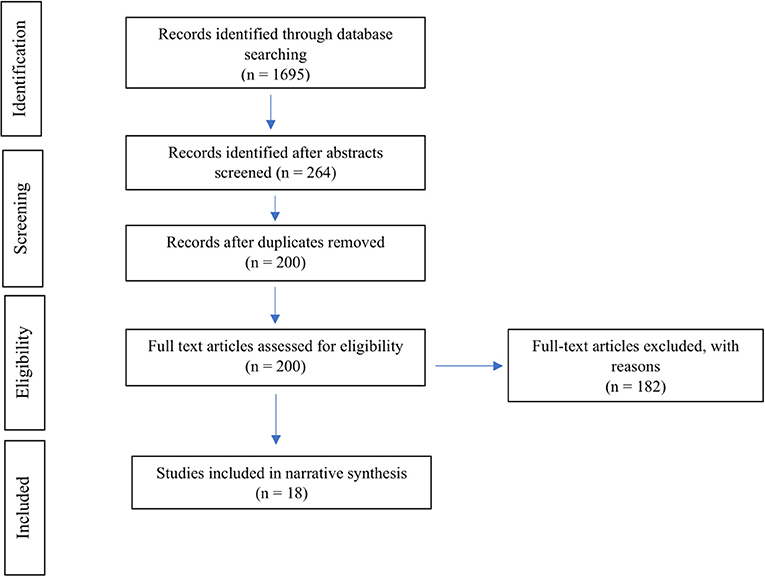

Methods: To address this deficit, employing PRISMA guidelines, this systematic review aimed to summarize empirical evidence regarding a range of interpersonal and intrapersonal MMO well-being outcomes for those older than 13.

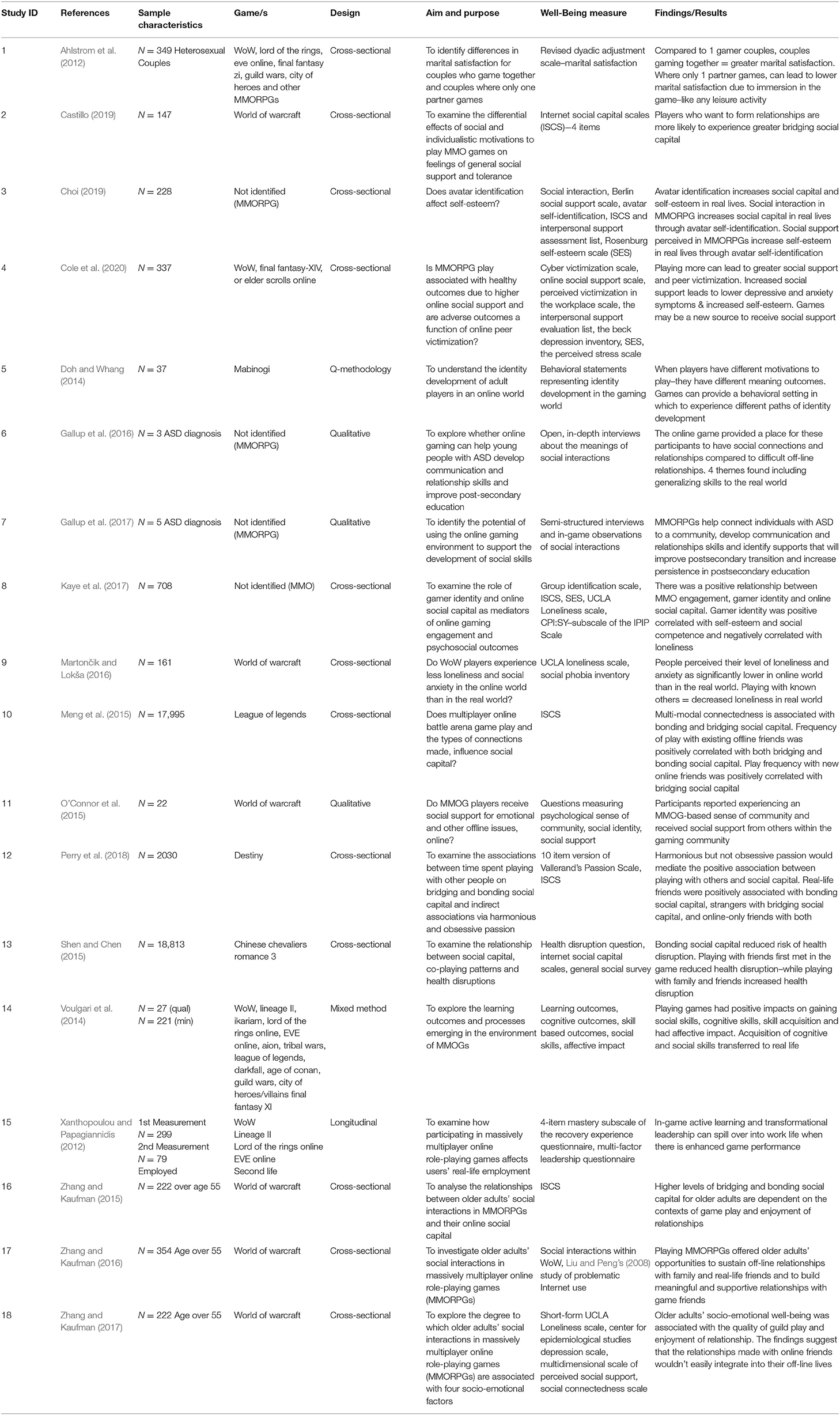

Results: Three databases identified 18 relevant English language studies, 13 quantitative, 4 qualitative and 1 mixed method published between January 2012 and August 2020. A narrative synthesis methodology was employed, whilst validated tools appraised risk of bias and study quality.

Conclusions: A significant positive relationship between playing MMOs and social well-being was concluded, irrespective of one's age and/or their casual or immersed gaming patterns. This finding should be considered in the light of the limited: (a) game platforms investigated; (b) well-being constructs identified; and (c) research quality (i.e., modest). Nonetheless, conclusions are of relevance for game developers and health professionals, who should be cognizant of the significant MMOs-well-being association(s). Future research should focus on broadening the well-being constructs investigated, whilst enhancing the applied methodologies.

Introduction

Internet gaming is a popular activity enjoyed by people around the globe, and across ages and gender ( Internet World Stats, 2020 ). With the addition of Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) in the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Health Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ) as a condition requiring further study, followed by the introduction of Gaming Disorder (GD) as a formal diagnostic classification in the 11th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11; World Health Organization, 2019 ), research concerning the associated adverse effects of gaming has increased ( Kircaburun et al., 2020 ; Teng et al., 2020 ). Accordingly, a series of potentially harmful aspects of internet gaming, such as reduced social skills, aggression, reduced family connection, interruptions to one's work and education have been cited ( Pontes et al., 2020 ).

Despite such likely aversive connotations, the uptake of internet gaming continues to increase. Recent statistics suggest that 64% of adults in the United States (U.S.) are gamers, 59% of those being male, with the average age range situated between 34 to 45 ( Entertainment Software Association, 2020 ). Of note is that 65% of those gamers are playing with others online or in person and they spend an average of 6.6 h playing per week with others online. Similarly, a survey of 801 New Zealand households (2,225 individuals) revealed that two-thirds play video games, with 34 years being the average age ( Brand et al., 2019 ).

Such high levels of game involvement have been interwoven with high reports of potential well-being benefits in the U.S. sample, including 80% for mental stimulation, 63% for problem solving, 55% for connecting with friends, 79% for relaxation and stress relief, 57% for enjoyment, and 50% for accommodating family quality time ( Entertainment Software Association, 2020 ). Interestingly, 30% of U.S. gamers met a good friend, spouse, or significant other through gaming ( Entertainment Software Association, 2020 ). Thus, video gaming does offer benefits, especially for one's socialization; indeed, gaming can simultaneously engage multiple online players ( Pierre-Louis, 2020 ; Pontes et al., 2020 ).

Multiplayer online games involve a broad genre of internet games, which entail participants playing with others in teams or competing within online virtual worlds ( Barnett and Coulson, 2010 ). A 2017 report of 1,234 Australian households (3,135 individuals) found 67% regularly played video games on computers, tablets, mobile phones, handheld devices, and gaming consoles, with 92% of those playing online with others ( Brand et al., 2017 ). When the “multiple-players” component allows the concurrent inclusion of large numbers (i.e., masses) of gamers, games are referred as massively multiplayer online games (MMOs; Stavropoulos et al., 2019 ). Such games employ the internet to simultaneously host millions of users globally. Participants tend to be organized in groups/teams/alliances competing with each other in the context of game worlds with progressively higher demands and challenges ( Adams et al., 2019 ). Massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPG) expand on this format of play with the introduction of role-playing characteristics through the creation of an avatar. This involves the player establishing their own customizable character for their gameplay, providing an opportunity for gamers to experiment with their own identity in a safe environment ( Stavropoulos et al., 2020 ). Thus, MMORPGs constitute a distinct subgenre of MMOs.

A preponderance of recent research on MMOs has focused specifically on the negative effects of problematic gaming or IGD ( Kircaburun et al., 2020 ; Pontes et al., 2020 ). For instance, a systematic review conducted by Männikkö et al. (2017) focused on health-related outcomes of problematic gaming behavior. This review aligns with prior research that looked at the risk factors and adverse health outcomes of excessive internet usage, particularly among adolescents ( Lam, 2014 ; Goh et al., 2019 ). Despite these efforts, Sublette and Mullan (2012) suggested that the evidence regarding the negative health consequences of gaming is inconclusive (e.g., overall health, sleep, aggression). As Internet games, and especially MMOs, may be also played moderately, they can accommodate a series of beneficial effects for the users such as socialization, a sense of achievement, and positive emotion ( Halbrook et al., 2019 ; Zhonggen, 2019 ; Colder Carras et al., 2020 ). Accordingly, the systematic literature review of Scott and Porter-Armstrong (2013) aimed to offer a more balanced view of the whole range of the positive and the negative effects of participation in MMORPGs, including on the psychosocial well-being of adolescents and young adults. They studied six research articles, where both negative and positive outcomes were identified; for instance, they concluded that problematic/pathological gaming associated with the negative outcomes such as depression, disrupted sleep, and avoidance of unpleasant thoughts. However, they also suggested that the MMORPG context could often provide a refuge from real-world issues, where new friendships and cooperative play could provide enjoyment. Correspondingly, a review of videogame use and flourishing mental health employing Seligman's 2011 positive psychology model of well-being (i.e., positive emotion; engagement; relationships; meaning and purpose; and accomplishment) reported that moderate levels of play was associated with improved mood and emotional regulation, decreased stress and emotional distress, and relaxation. Decisively, Jones and colleagues ( Jones et al., 2014 ) asserted that “videogame research must move beyond a “good-bad” dichotomy and develop a more nuanced understanding about videogame play” (p. 7).