I Am Prepared to Die

27 pages • 54 minutes read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Essay Analysis

Key Figures

Index of Terms

Literary Devices

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Analysis: “I Am Prepared to Die”

The purpose of Mandela’s speech is not to claim innocence in the face of the sabotage charges, as he admits to his prominent involvement in Umkhonto. Rather, the purpose is to use the court proceeding as a prominent venue in which to reframe the narrative . Mandela argues that his actions are justified in the context of the freedom struggle against apartheid . Therefore, throughout the speech, Mandela uses persuasive rhetorical techniques, relying on political arguments, examples of historic protests and court cases, statistics indicating the scope of inequality, and details from his own life and upbringing. Although the speech connects many key dates and events, it notably follows a non-linear narrative progression, as Mandela calls on these events when they are needed to substantiate his points.

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By Nelson Mandela

Long Walk to Freedom

Nelson Mandela

No Easy Walk to Freedom

Featured Collections

African History

View Collection

Books on Justice & Injustice

Mortality & Death

Politics & Government

South African Literature

Transcript: Nelson Mandela speech 'I am prepared to die’

Here is the transcript of nelson mandela's 'i am prepared to die' speech, which he gave from the dock during the rivonia trial, pretoria supreme court, 20 april 1964. this transcript is as published on the nelson mandela centre of memory website..

Share this with family and friends

Recommended for you

A 'wonderful human' and a Trump fan: Who is the stabbed Sydney church leader?

Terrorist attacks

Iran plays down the impact of apparent Israeli airstrikes, signals no further retaliation

War and unrest

Daniel Andrews and John Pesutto among 235 Australians sanctioned by Russia

Man dies after setting himself on fire outside Donald Trump's hush money trial courthouse

Legal proceedings

How Australians can view the rare 'Devil Comet' before it disappears for 70 years

Australia Post will make a big delivery change next week. Here's how it will affect you

Postal service

Anthony Albanese calls for calm after 'terrorist act'; police say rioters 'will be prosecuted'

News and Current Affairs

What was thought to be a 'significant' COVID-19 milestone wasn't at all

Get sbs news daily and direct to your inbox, sign up now for the latest news from australia and around the world direct to your inbox..

Morning (Mon–Fri)

Afternoon (Mon–Fri)

By subscribing, you agree to SBS’s terms of service and privacy policy including receiving email updates from SBS.

SBS World News

Nelson Mandela Foundation

- Mandela Day

Advanced search

“I am prepared to die”

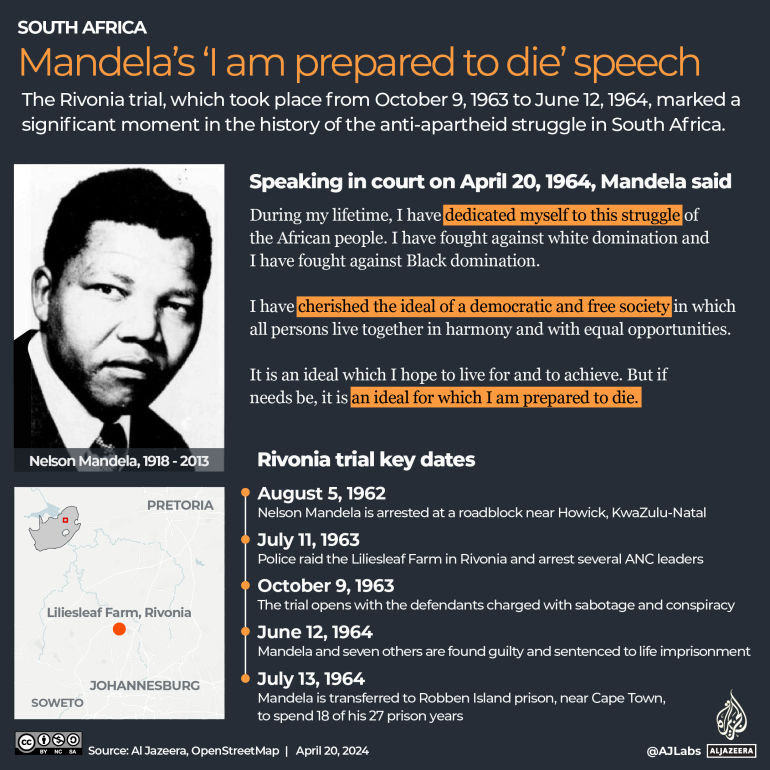

April 20, 2011 – April 20, 2011 marks the 47th anniversary of Nelson Mandela’s speech from the dock in the Rivonia Trial in which he said he was prepared to die for a democratic, non-racial South Africa.

The Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory has a rare typescript of the speech, which Mr Mandela autographed and gave as a gift to a comrade.

In the Rivonia Trial Mr Mandela chose, instead of testifying, to make a speech from the dock and proceeded to hold the court spellbound for more than four hours. His speech, which was made at the beginning of the defence case, ended with the words:

“During my lifetime I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

Click here to see the last page from the speech from the dock.

Less than two months later, Mr Mandela and his comrades Walter Sisulu, Ahmed Kathrada, Govan Mbeki, Denis Goldberg, Raymond Mhlaba, Andrew Mlangeni and Elias Motsoaledi, were convicted of sabotage and sentenced to life imprisonment. Apartheid laws dictated that the only white person sentenced, Denis Goldberg, should be held in Pretoria Central Prison. The other seven were sent to Robben Island.

Below the final paragraph of his typewritten speech Mr Mandela wrote:

“The invincibility of our cause and the certainty of our final victory are the impenetrable armour of those who consistently uphold their faith in freedom and justice in spite of political persecution” .

He signed the speech and dated it ‘April 1964’. Mr Mandela then gave the speech to Sylvia Neame, a political activist and the partner, at the time, of Mr Kathrada. She was arrested in August 1964 and put on trial with Advocate Bram Fischer and 10 others.

In April 1965 they were convicted and sentenced. Ms Neame was sentenced to four years (two years to run concurrently). She was released from prison in 1967 and went into exile.

After he was released from prison she gave the signed copy of the speech to Mr Kathrada who donated it to the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory.

Adv Fischer, who led the defence team in the Rivonia Trial, skipped bail during the trial with Ms Neame and others and was convicted in absentia.

He was rearrested in 1966 and sentenced to life imprisonment. In prison he contracted cancer which was diagnosed late. He was put under house arrest in his brother’s house in April 1975 where he died a few weeks later.

Click here for a full transcript of Mr Mandela’s speech from the dock.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

An ideal for which I am prepared to die

I am the first accused. I hold a bachelor's degree in arts and practised as an attorney in Johannesburg for a number of years in partnership with Oliver Tambo. I am a convicted prisoner serving five years for leaving the country without a permit and for inciting people to go on strike at the end of May 1961.

At the outset, I want to say that the suggestion that the struggle in South Africa is under the influence of foreigners or communists is wholly incorrect. I have done whatever I did because of my experience in South Africa and my own proudly felt African background, and not because of what any outsider might have said. In my youth in the Transkei I listened to the elders of my tribe telling stories of the old days. Amongst the tales they related to me were those of wars fought by our ancestors in defence of the fatherland. The names of Dingane and Bambata, Hintsa and Makana, Squngthi and Dalasile, Moshoeshoe and Sekhukhuni, were praised as the glory of the entire African nation. I hoped then that life might offer me the opportunity to serve my people and make my own humble contribution to their freedom struggle.

Some of the things so far told to the court are true and some are untrue. I do not, however, deny that I planned sabotage. I did not plan it in a spirit of recklessness, nor because I have any love of violence. I planned it as a result of a calm and sober assessment of the political situation that had arisen after many years of tyranny, exploitation, and oppression of my people by the whites.

I admit immediately that I was one of the persons who helped to form Umkhonto we Sizwe. I deny that Umkhonto was responsible for a number of acts which clearly fell outside the policy of the organisation, and which have been charged in the indictment against us. I, and the others who started the organisation, felt that without violence there would be no way open to the African people to succeed in their struggle against the principle of white supremacy. All lawful modes of expressing opposition to this principle had been closed by legislation, and we were placed in a position in which we had either to accept a permanent state of inferiority, or to defy the government. We chose to defy the law.

We first broke the law in a way which avoided any recourse to violence; when this form was legislated against, and then the government resorted to a show of force to crush opposition to its policies, only then did we decide to answer violence with violence.

The African National Congress was formed in 1912 to defend the rights of the African people, which had been seriously curtailed. For 37 years - that is, until 1949 - it adhered strictly to a constitutional struggle. But white governments remained unmoved, and the rights of Africans became less instead of becoming greater. Even after 1949, the ANC remained determined to avoid violence. At this time, however, the decision was taken to protest against apartheid by peaceful, but unlawful, demonstrations. More than 8,500 people went to jail. Yet there was not a single instance of violence. I and 19 colleagues were convicted for organising the campaign, but our sentences were suspended mainly because the judge found that discipline and non-violence had been stressed throughout.

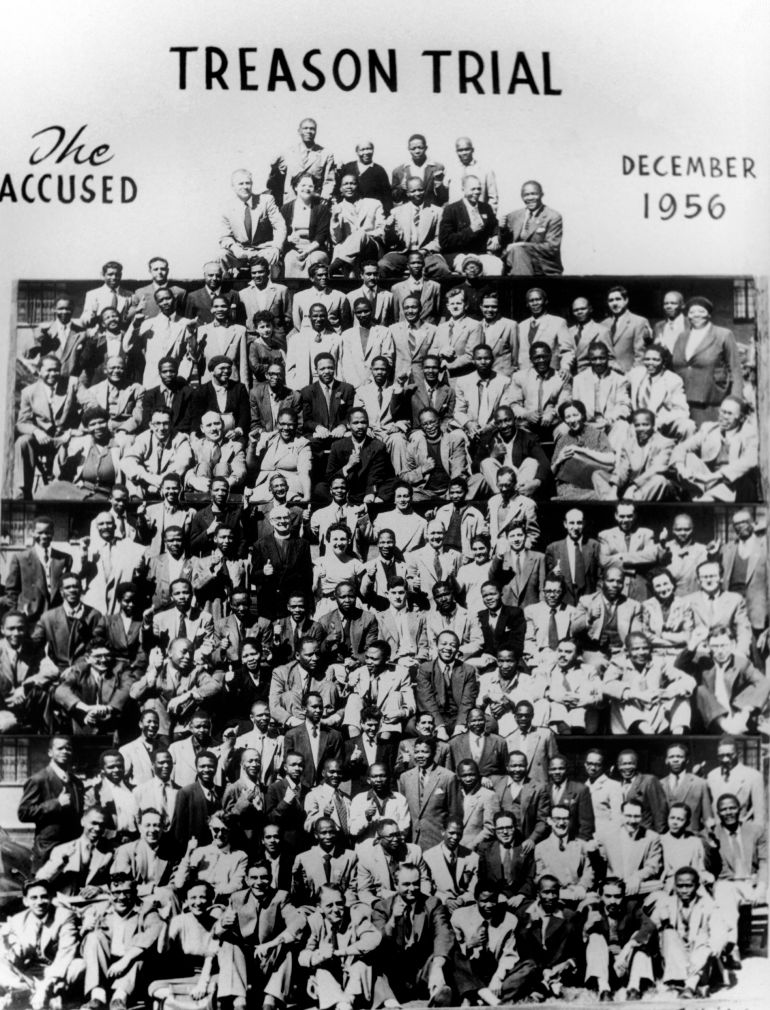

During the defiance campaign, the Public Safety Act and the Criminal Law Amendment Act were passed. These provided harsher penalties for protests against [the] laws. Despite this, the protests continued and the ANC adhered to its policy of non-violence. In 1956, 156 leading members of the Congress Alliance, including myself, were arrested. The non-violent policy of the ANC was put in issue by the state, but when the court gave judgment some five years later, it found that the ANC did not have a policy of violence.

In 1960 there was the shooting at Sharpeville, which resulted in the declaration of the ANC as an unlawful organisation. My colleagues man and I, after careful consideration, decided that we would not obey this decree. The African people were not part of the government and did not make the laws by which they were governed. We believed in the words of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, that "the will of the people shall be the basis of authority of the government", and for us to accept the banning was equivalent to accepting the silencing of the Africans for all time. The ANC refused to dissolve, but instead went underground.

In 1960 the government held a referendum which led to the establishment of the republic. Africans, who constituted approximately 70% of the population, were not entitled to vote, and were not even consulted. I undertook to be responsible for organising the national stay-at-home called to coincide with the declaration of the republic. As all strikes by Africans are illegal, the person organising such a strike must avoid arrest. I had to leave my home and family and my practice and go into hiding to avoid arrest. The stay-at-home was to be a peaceful demonstration. Careful instructions were given to avoid any recourse to violence.

The government's answer was to introduce new and harsher laws, to mobilise its armed forces, and to send Saracens, armed vehicles, and soldiers into the townships in a massive show of force designed to intimidate the people. The government had decided to rule by force alone, and this decision was a milestone on the road to Umkhonto. What were we, the leaders of our people, to do? We had no doubt that we had to continue the fight. Anything else would have been abject surrender. Our problem was not whether to fight, but was how to continue the fight.

We of the ANC had always stood for a non-racial democracy, and we shrank from any action which might drive the races further apart. But the hard facts were that 50 years of non-violence had brought the African people nothing but more and more repressive legislation, and fewer and fewer rights. By this time violence had, in fact, become a feature of the South African political scene.

There had been violence in 1957 when the women of Zeerust were ordered to carry passes; there was violence in 1958 with the enforcement of cattle culling in Sekhukhuneland; there was violence in 1959 when the people of Cato Manor protested against pass raids; there was violence in 1960 when the government attempted to impose Bantu authorities in Pondoland. Each disturbance pointed to the inevitable growth among Africans of the belief that violence was the only way out - it showed that a government which uses force to maintain its rule teaches the oppressed to use force to oppose it.

I came to the conclusion that as violence in this country was inevitable, it would be unrealistic to continue preaching peace and non-violence. This conclusion was not easily arrived at. It was only when all else had failed, when all channels of peaceful protest had been barred to us, that the decision was made to embark on violent forms of political struggle. I can only say that I felt morally obliged to do what I did.

Four forms of violence were possible. There is sabotage, there is guerrilla warfare, there is terrorism, and there is open revolution. We chose to adopt the first. Sabotage did not involve loss of life, and it offered the best hope for future race relations. Bitterness would be kept to a minimum and, if the policy bore fruit, democratic government could become a reality. The initial plan was based on a careful analysis of the political and economic situation of our country. We believed that South Africa depended to a large extent on foreign capital. We felt that planned destruction of power plants, and interference with rail and telephone communications, would scare away capital from the country, thus compelling the voters of the country to reconsider their position. Umkhonto had its first operation on December 16 1961, when government buildings in Johannesburg, Port Elizabeth and Durban were attacked. The selection of targets is proof of the policy to which I have referred. Had we intended to attack life we would have selected targets where people congregated and not empty buildings and power stations.

The whites failed to respond by suggesting change; they responded to our call by suggesting the laager. In contrast, the response of the Africans was one of encouragement. Suddenly there was hope again. People began to speculate on how soon freedom would be obtained.

But we in Umkhonto weighed up the white response with anxiety. The lines were being drawn. The whites and blacks were moving into separate camps, and the prospects of avoiding a civil war were made less. The white newspapers carried reports that sabotage would be punished by death. If this was so, how could we continue to keep Africans away from terrorism?

We felt it our duty to make preparations to use force in order to defend ourselves against force. We decided, therefore to make provision for the possibility of guerrilla warfare. All whites undergo compulsory military training, but no such training was given to Africans. It was in our view essential to build up a nucleus of trained men who would be able to provide the leadership which would be required if guerrilla warfare started.

At this stage it was decided that I should attend the Conference of the Pan-African Freedom Movement which was to be held early in 1962 in Addis Ababa, and after the conference, I would undertake a tour of the African states with a view to obtaining facilities for the training of soldiers. My tour was a success. Wherever I went I met sympathy for our cause and promises of help. All Africa was united against the stand of white South Africa, and even in London I was received with great sympathy by political leaders, such as Mr Gaitskell and Mr Grimond.

I started to make a study of the art of war and revolution and, whilst abroad, underwent a course in military training. If there was to be guerrilla warfare, I wanted to be able to stand and fight with my people and to share the hazards of war with them.

On my return I found that there had been little alteration in the political scene save, that the threat of a death penalty for sabotage had now become a fact.

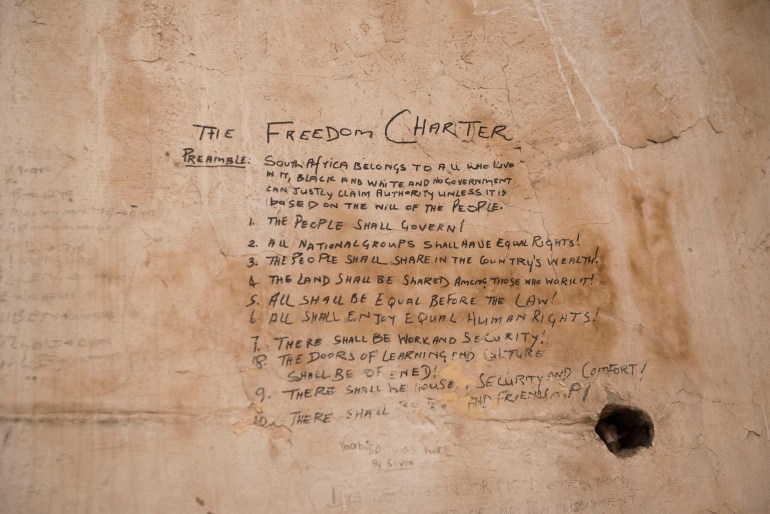

Another of the allegations made by the state is that the aims and objects of the ANC and the Communist party are the same. The creed of the ANC is, and always has been, the creed of African nationalism. It is not the concept of African nationalism expressed in the cry, "Drive the white man into the sea." The African nationalism for which the ANC stands is the concept of freedom and fulfilment for the African people in their own land. The most important political document ever adopted by the ANC is the "freedom charter". It is by no means a blueprint for a socialist state. It calls for redistribution, but not nationalisation, of land; it provides for nationalisation of mines, banks, and monopoly industry, because big monopolies are owned by one race only, and without such nationalisation racial domination would be perpetuated despite the spread of political power. Under the freedom charter, nationalisation would take place in an economy based on private enterprise.

As far as the Communist party is concerned, and if I understand its policy correctly, it stands for the establishment of a state based on the principles of Marxism. The Communist party sought to emphasise class distinctions whilst the ANC seeks to harmonise them. This is a vital distinction.

It is true that there has often been close cooperation between the ANC and the Communist party. But cooperation is merely proof of a common goal - in this case the removal of white supremacy - and is not proof of a complete community of interests. The history of the world is full of similar examples. Perhaps the most striking is the cooperation between Great Britain, the United States and the Soviet Union in the fight against Hitler. Nobody but Hitler would have dared to suggest that such cooperation turned Churchill or Roosevelt into communists. Theoretical differences amongst those fighting against oppression is a luxury we cannot afford at this stage.

What is more, for many decades communists were the only political group in South Africa prepared to treat Africans as human beings and their equals; who were prepared to eat with us; talk with us, live with us, and work with us. They were the only group which was prepared to work with the Africans for the attainment of political rights and a stake in society. Because of this, there are many Africans who, today, tend to equate freedom with communism. They are supported in this belief by a legislature which brands all exponents of democratic government and African freedom as communists and bans many of them (who are not communists) under the Suppression of Communism Act. Although I have never been a member of the Communist party, I myself have been imprisoned under that act.

I have always regarded myself, in the first place, as an African patriot. Today I am attracted by the idea of a classless society, an attraction which springs in part from Marxist reading and, in part, from my admiration of the structure of early African societies. The land belonged to the tribe. There were no rich or poor and there was no exploitation. We all accept the need for some form of socialism to enable our people to catch up with the advanced countries of this world and to overcome their legacy of extreme poverty. But this does not mean we are Marxists.

I have gained the impression that communists regard the parliamentary system of the west as reactionary. But, on the contrary, I am an admirer. The Magna Carta, the Petition of Right, and the Bill of Rights are documents held in veneration by democrats throughout the world. I have great respect for British institutions, and for the country's system of justice. I regard the British parliament as the most democratic institution in the world, and the impartiality of its judiciary never fails to arouse my admiration. The American Congress, that country's separation of powers, as well as the independence of its judiciary, arouses in me similar sentiments.

I have been influenced in my thinking by both west and east. I should tie myself to no particular system of society other than of socialism. I must leave myself free to borrow the best from the west and from the east.

Our fight is against real, and not imaginary, hardships or, to use the language of the state prosecutor, "so-called hardships". Basically, we fight against two features which are the hallmarks of African life in South Africa and which are entrenched by legislation. These features are poverty and lack of human dignity, and we do not need communists or so-called "agitators" to teach us about these things. South Africa is the richest country in Africa, and could be one of the richest countries in the world. But it is a land of remarkable contrasts. The whites enjoy what may be the highest standard of living in the world, whilst Africans live in poverty and misery. Poverty goes hand in hand with malnutrition and disease. Tuberculosis, pellagra and scurvy bring death and destruction of health.

The complaint of Africans, however, is not only that they are poor and the whites are rich, but that the laws which are made by the whites are designed to preserve this situation. There are two ways to break out of poverty. The first is by formal education, and the second is by the worker acquiring a greater skill at his work and thus higher wages. As far as Africans are concerned, both these avenues of advancement are deliberately curtailed by legislation.

The government has always sought to hamper Africans in their search for education. There is compulsory education for all white children at virtually no cost to their parents, be they rich or poor. African children, however, generally have to pay more for their schooling than whites.

Approximately 40% of African children in the age group seven to 14 do not attend school. For those who do, the standards are vastly different from those afforded to white children. Only 5,660 African children in the whole of South Africa passed their junior certificate in 1962, and only 362 passed matric.

This is presumably consistent with the policy of Bantu education about which the present prime minister said: "When I have control of native education I will reform it so that natives will be taught from childhood to realise that equality with Europeans is not for them. People who believe in equality are not desirable teachers for natives. When my department controls native education it will know for what class of higher education a native is fitted, and whether he will have a chance in life to use his knowledge."

The other main obstacle to the advancement of the African is the industrial colour-bar under which all the better jobs of industry are reserved for whites only. Moreover, Africans who do obtain employment in the unskilled and semi-skilled occupations open to them are not allowed to form trade unions which have recognition. This means that they are denied the right of collective bargaining, which is permitted to the better-paid white workers.

The government answers its critics by saying that Africans in South Africa are better off than the inhabitants of the other countries in Africa. I do not know whether this statement is true. But even if it is true, as far as the African people are concerned it is irrelevant.

Our complaint is not that we are poor by comparison with people in other countries, but that we are poor by comparison with the white people in our own country, and that we are prevented by legislation from altering this imbalance.

The lack of human dignity experienced by Africans is the direct result of the policy of white supremacy. White supremacy implies black inferiority. Legislation designed to preserve white supremacy entrenches this notion. Menial tasks in South Africa are invariably performed by Africans.

When anything has to be carried or cleaned the white man will look around for an African to do it for him, whether the African is employed by him or not. Because of this sort of attitude, whites tend to regard Africans as a separate breed. They do not look upon them as people with families of their own; they do not realise that they have emotions - that they fall in love like white people do; that they want to be with their wives and children like white people want to be with theirs; that they want to earn enough money to support their families properly, to feed and clothe them and send them to school. And what "house-boy" or "garden-boy" or labourer can ever hope to do this?

Pass laws render any African liable to police surveillance at any time. I doubt whether there is a single African male in South Africa who has not had a brush with the police over his pass. Hundreds and thousands of Africans are thrown into jail each year under pass laws.

Even worse is the fact that pass laws keep husband and wife apart and lead to the breakdown of family life. Poverty and the breakdown of family have secondary effects. Children wander the streets because they have no schools to go to, or no money to enable them to go, or no parents at home to see that they go, because both parents (if there be two) have to work to keep the family alive. This leads to a breakdown in moral standards, to an alarming rise in illegitimacy, and to violence, which erupts not only politically, but everywhere. Life in the townships is dangerous. Not a day goes by without somebody being stabbed or assaulted. And violence is carried out of the townships [into] the white living areas. People are afraid to walk the streets after dark. Housebreakings and robberies are increasing, despite the fact that the death sentence can now be imposed for such offences. Death sentences cannot cure the festering sore.

Africans want to be paid a living wage. Africans want to perform work which they are capable of doing, and not work which the government declares them to be capable of. Africans want to be allowed to live where they obtain work, and not be endorsed out of an area because they were not born there. Africans want to be allowed to own land in places where they work, and not to be obliged to live in rented houses which they can never call their own. Africans want to be part of the general population, and not confined to living in their own ghettoes.

African men want to have their wives and children to live with them where they work, and not be forced into an unnatural existence in men's hostels. African women want to be with their menfolk and not be left permanently widowed in the reserves. Africans want to be allowed out after 11 o'clock at night and not to be confined to their rooms like little children. Africans want to be allowed to travel in their own country and to seek work where they want to and not where the labour bureau tells them to. Africans want a just share in the whole of South Africa; they want security and a stake in society.

Above all, we want equal political rights, because without them our disabilities will be permanent. I know this sounds revolutionary to the whites in this country, because the majority of voters will be Africans. This makes the white man fear democracy. But this fear cannot be allowed to stand in the way of the only solution which will guarantee racial harmony and freedom for all. It is not true that the enfranchisement of all will result in racial domination. Political division, based on colour, is entirely artificial and, when it disappears, so will the domination of one colour group by another. The ANC has spent half a century fighting against racialism. When it triumphs it will not change that policy.

This then is what the ANC is fighting. Their struggle is a truly national one. It is a struggle of the African people, inspired by their own suffering and their own experience. It is a struggle for the right to live. During my lifetime I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.

· With thanks to the Nelson Mandela Foundation

- Nelson Mandela

- Great speeches: Nelson Mandela

Most viewed

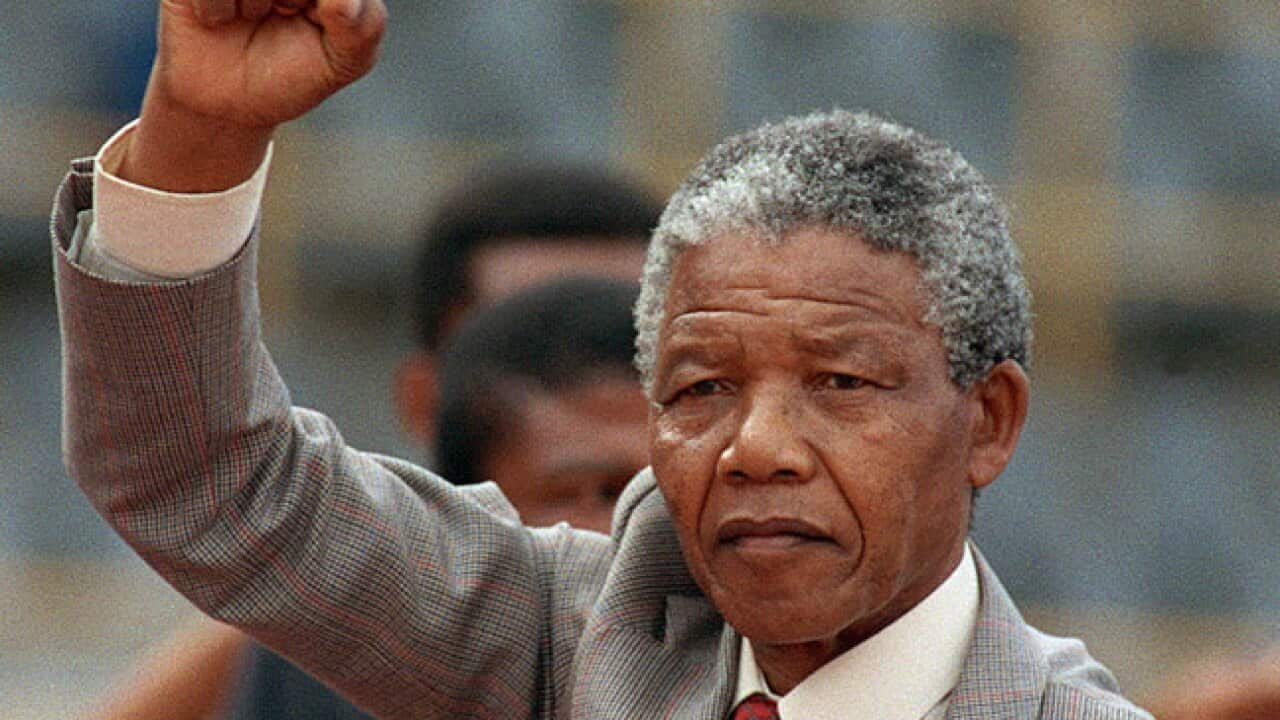

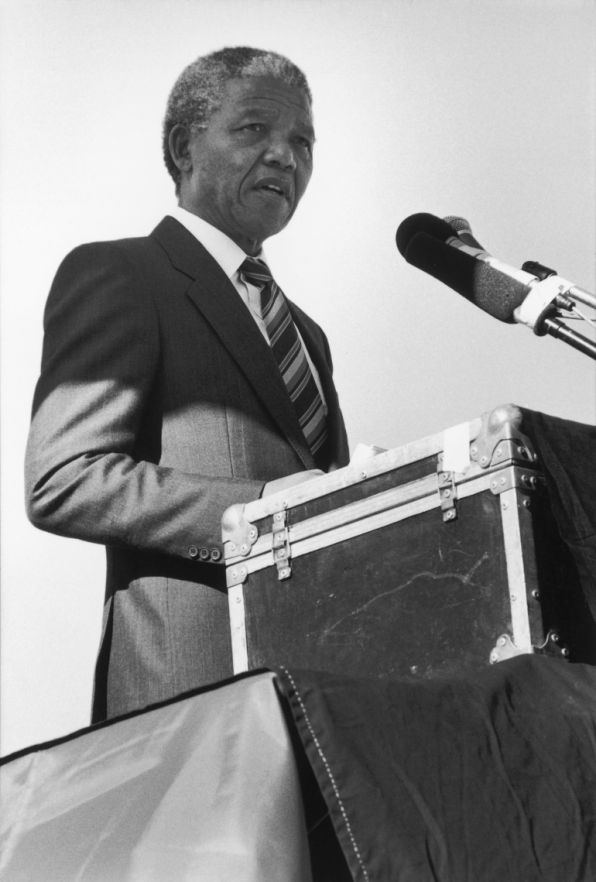

‘I am prepared to die’: Mandela’s speech which shook apartheid

Sixty years ago during the Rivonia Trial in South Africa, Nelson Mandela delivered one of the most famous speeches of the 20th century. He expected to be sentenced to death but instead lived to see his dream ‘of a democratic and free society’ realised.

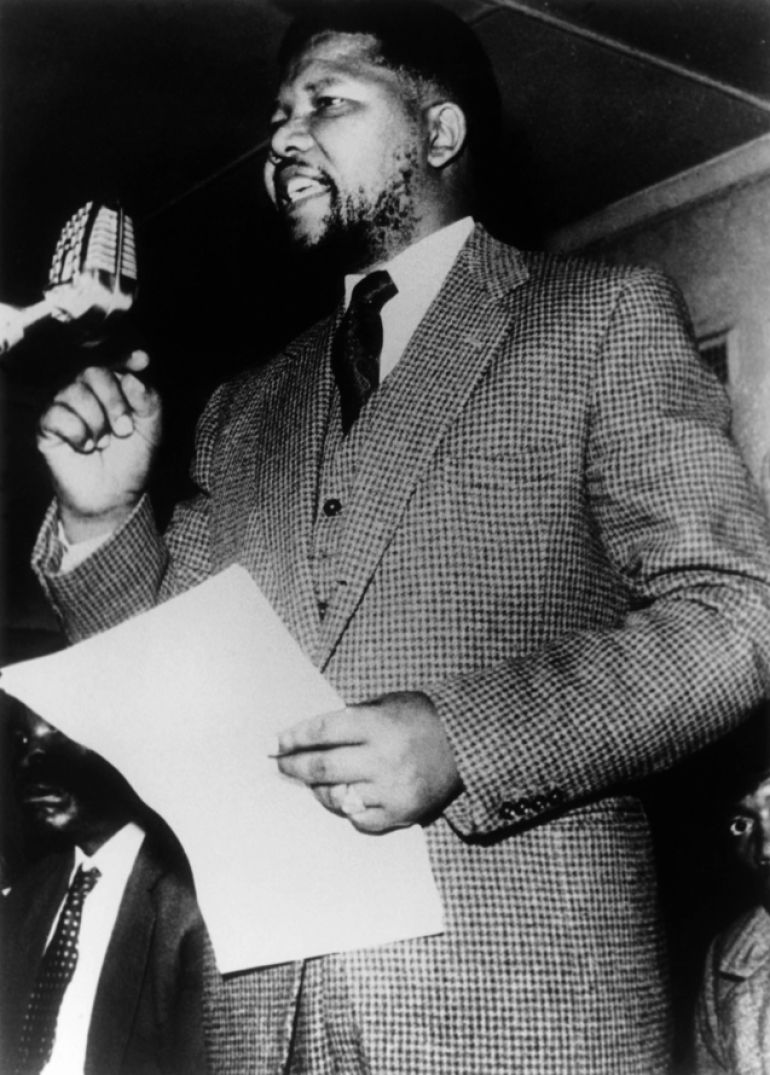

“Accused number one” had been speaking from the dock for almost three hours by the time he uttered the words that would ultimately change South Africa. The racially segregated Pretoria courtroom listened in silence as Nelson Mandela’s account of his lifelong struggle against white minority rule reached its conclusion. Judge Quintus de Wet managed not to look at Mandela for the majority of his address. But before accused number one delivered his final lines, defence lawyer Joel Joffe remembered, “Mandela paused for a long time and looked squarely at the judge” before saying:

“During my lifetime, I have dedicated my life to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against Black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons will live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal for which I hope to live for and to see realised. But, my Lord, if it needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

Keep reading

South africa seeks to stop auction of historic nelson mandela artefacts, a way of saying ‘we shall overcome’: playing football on robben island, history illustrated: mandela – south africa’s first black preside, king charles to host sa’s ramaphosa in first state visit of reign.

After he spoke that last sentence, novelist and activist Nadine Gordimer, who was in the courtroom on April 20, 1964, said, “The strangest and most moving sound I have ever heard from human throats came from the Black side of the court audience. It was short, sharp and terrible: something between a sigh and a groan.”

This was because there was a very good chance that Mandela and his co-accused would be sentenced to death for their opposition to the apartheid government. His lawyers had actually tried to talk him out of including the “I am prepared to die” line because they thought it might be seen as a provocation. But as Mandela later wrote in his autobiography, “I felt we were likely to hang no matter what we said, so we might as well say what we truly believed.”

‘The trial that changed South Africa’

The Rivonia Trial – in which Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki and seven other anti-apartheid activists were charged with sabotage – was the third and final time Mandela would stand accused in an apartheid court. From 1956 to 1961, he had been involved in the Treason Trial, a long-running embarrassment for the apartheid government, which would ultimately see all 156 of the accused acquitted because the state failed to prove they had committed treason.

And in 1962, he had been charged with leaving the country illegally and leading Black workers in a strike. He knew he was guilty on both counts, so he decided to put the apartheid government on trial. On the first day of the case, Mandela, known for his natty Western dress, arrived in traditional Xhosa attire to the shock of all present. He led his own defence and did not call any witnesses. Instead, he gave what has been remembered as the “Black man in a white court” speech, during which he asserted that “posterity will pronounce that I was innocent and that the criminals that should have been brought before this court are the members of the Verwoerd government,” a reference to Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd.

The Rivonia Trial, which kicked off in October 1963, was named after the Johannesburg suburb where Liliesleaf Farm was located. From 1961 to 1963, the Liliesleaf museum website notes, the farm served “as the secret headquarters and nerve centre” of the African National Congress (ANC), the South African Communist Party (SACP) and Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK, the military wing of the ANC). On July 11, 1963, acting on a tip-off, the police raided Liliesleaf, seizing many incriminating documents and arresting the core leadership of the underground liberation movement. Mandela, who was serving a five-year sentence on Robben Island from his conviction in the 1962 trial, was flown to Pretoria to take his place as accused number one.

Instead of charging the men with high treason, State Prosecutor Percy Yutar opted for the easier-to-prove crime of sabotage – the definition of which was so broad that it included misdemeanours such as trespassing – and which had recently been made a capital offence by the government. Thanks to the evidence seized from Liliesleaf, which included several documents handwritten by Mandela and the testimony of Bruno Mtolo (referred to as Mr X throughout the trial), a regional commander of MK who had turned state witness, Yutar was virtually assured of convictions for the main accused.

In his autobiography, Mandela explains their defence strategy: “Right from the start we had made it clear that we intended to use the trial not as a test of the law but as a platform for our beliefs. We would not deny, for example, that we had been responsible for acts of sabotage. We would not deny that a group of us had turned away from non-violence. We were not concerned with getting off or lessening our punishment, but with making the trial strengthen the cause for which we were struggling – at whatever cost to ourselves. We would not defend ourselves in a legal sense so much as in a moral sense.”

The accused and their lawyers decided that Mandela would open the defence case not as a witness – who would be subject to cross-examination – but with a statement from the dock. This format would allow him to speak uninterrupted, but it carried less legal weight.

Mandela writes that he spent “about a fortnight drafting [his] address, working mainly in my cell in the evenings”. He first read it to his co-accused, who approved the text with a few tweaks, before passing it to lead defence lawyer Bram Fischer. Fischer was concerned that the final paragraph might be taken the wrong way by the judge, so he got another member of the defence team, Hal Hanson, to read it. Hanson was unequivocal: “If Mandela reads this in court, they will take him straight to the back of the courthouse and string him up.”

“Nelson remained adamant” that the line should stay, wrote George Bizos, another member of the defence team. Bizos eventually persuaded Mandela to tweak his wording: “I proposed that Nelson say he hoped to live for and achieve his ideals but if needs be was prepared to die.”

On the evening of April 19, Bizos got Mandela’s permission to take a copy of his statement to Gordimer. The respected British journalist Anthony Sampson, who knew Mandela well, happened to be staying with her and he retired to Gordimer’s study with the text. “What seemed like hours” later, Bizos wrote, Sampson “eventually returned, obviously moved by what he had read”. Sampson made no major changes to the text, but he did advise moving some of the paragraphs because he felt journalists were likely to read the beginning and the end properly and skim over the rest.

Gordimer does not seem to have suggested changes to the address, but she did see several drafts. She, too, was happy with the final version.

The statement from the dock

Yutar, who had been hoodwinked by the defence team’s constant requests for court transcripts into spending weeks preparing to cross-examine Mandela, was visibly shocked when Fischer announced that Mandela would instead be making a statement from the dock. He even tried to get the judge to explain to Mandela that he was committing a legal error. But the usually stone-faced judge laughed as he dismissed the request. Mandela, himself a lawyer, was represented by some of the country’s finest legal minds. He knew exactly what he was doing.

“My Lord, I am the first accused,” Mandela said. “I admit immediately that I was one of the persons who helped to form Umkhonto we Sizwe and that I played a prominent role in its affairs until I was arrested in August 1962.” Thanks to the recent recovery of the original recordings of Mandela’s statement, we now know that he spoke for 176 minutes , not the four and a half hours regularly cited.

As Martha Evans, author of Speeches That Shaped South Africa, explained, Mandela “candidly confessed some of the crimes levelled against him before giving a cogent and detailed account of the conditions and events that had led to the establishment of MK and the adoption of the armed struggle”.

He spoke at length of the ANC’s tradition of nonviolence and explained why he had planned sabotage: “I did not plan it in a spirit of recklessness nor because I have any love for violence. I planned it as a result of a calm and sober assessment of the political situation that had arisen after many years of tyranny, exploitation and oppression of my people by the whites.”

The final section of the address focused on inequality in South Africa and humanised Black South Africans in ways that Mandela argued the country’s white population rarely acknowledged:

“Whites tend to regard Africans as a separate breed. They do not look upon them as people with families of their own. They do not realise that we have emotions, that we fall in love like white people do, that we want to be with our wives and children like white people want to be with theirs, that we want to earn money, enough money to support our families properly.”

And: “Above all, my Lord, we want equal political rights because without them our disabilities will be permanent. I know this sounds revolutionary to the whites in this country because the majority of voters will be Africans. This makes the white man fear democracy. But this fear cannot be allowed to stand in the way of the only solution which will guarantee racial harmony and freedom for all.”

Interestingly, Gordimer noted that the speech “read much better than it was spoken. Mandela’s delivery was very disappointing indeed, hesitant, parsonical (if there is such a word), boring. Only at the end did the man come through.”

Hanging by a thread

After Mandela’s address, several of the accused subjected themselves to cross-examination. Gordimer was particularly impressed by Walter Sisulu: “Sisulu was splendid. What a paradox – he is almost uneducated while [Mandela] has a law degree! He was lucid and to the point – and never missed a point in his replies to Yutar.”

The defence team enjoyed a number of minor victories with Judge de Wet fairly regularly telling the court that Yutar had failed to prove one point or another. After final arguments were heard in mid-May, court was adjourned for three weeks for the judge to consider his verdict.

For the main accused, that verdict was always going to be guilty. Avoiding the noose became the defence team’s number one priority. In the courtroom, this entailed asking Alan Paton, a world famous novelist who was leader of the vehemently anti-apartheid Liberal Party, to give evidence in mitigation of sentence.

But the real action happened outside the court, Sampson wrote in his authorised biography of Mandela: “The accused had been buoyed up by the growing support from abroad, not only from many African countries but also, more to Mandela’s surprise, from Britain. … On May 7, 1964, the British Prime Minister, Alec Douglas-Home, offered to send a private message to Verwoerd about the trial. But Sir Hugh Stephenson [Britain’s ambassador to South Africa] recommended that ‘no more pressure should be exerted’ and, contrary to some published reports, there is no evidence the message was sent. When the South African Ambassador called on the Foreign Office that month, he was told that the government was now under less pressure to take a stronger line against South Africa, though death sentences would bring the matter to a head again.”

A week before the verdicts, Bizos visited British Consul-General Leslie Minford at his Pretoria home. “As I was leaving, Leslie put his arm around my shoulders and said, ‘George, there won’t be a death sentence.’ I did not ask him how he knew. For one thing, he had downed a number of whiskies. Certainly, I felt I could not rely on the information nor could I tell the team or our anxious clients.”

Upping the stakes further was the decision by Mandela, Sisulu and Mbeki to not appeal their sentence – even if it were death. As he listened to sentencing arguments, Mandela clutched a handwritten note that concluded with the words: “If I must die, let me declare for all to know that I will meet my fate as a man.”

Paton and Hanson spoke in mitigation of sentence on the morning of June 12, 1964. Bizos noted, “Judge de Wet not only took no note of what was being said but he appeared not to be listening.” He had already made his mind up, and when the formalities were over, he announced: “I have decided not to impose the supreme penalty, which in a case like this would usually be the penalty for such a crime. But consistent with my duty, that is the only leniency which I can show. The sentence in the case of all the accused will be one of life imprisonment.”

Professor Thula Simpson, the leading historian of MK, told Al Jazeera, “There is no evidence that De Wet was leaned on by the state. I don’t believe there’s any evidence for this being a political rather than a judicial judgement.”

Professor Roger Southall, author of dozens of books on Southern African politics, agreed. “At the time, there was a lot of speculation about whether there was pressure on the SA government to ensure that capital punishment was not imposed,” he told Al Jazeera. “But there is also no proof that the SA government intervened. That remains an unanswered question. We have to presume that the judge knew the international and local climate.”

Business as usual?

“Rivonia got a lot of global publicity,” Southall said. “But once the trial ended, it seemed like Mandela had been forgotten.” Mandela and other senior ANC figures were either locked up on Robben Island or were living in relative obscurity in exile. “Capital came pouring into South Africa at a rate that’s never been equalled since,” Southall continued. “The apartheid government seemed totally in control. The resistance was dead. It was a thoroughly grim period for the ANC.”

This only started to change in 1973, Southall said, “with the Durban strikes and the revival of the trade union movement”, which had been battered into submission. The rebirth of the Black trade union movement signalled the beginning of a new phase of opposition politics. Things ratcheted up several notches on June 16, 1976, when apartheid policemen opened fire on a peaceful protest of schoolchildren in the Black township of Soweto, killing 15 people. In the eight months that followed, violence spread across South Africa, killing about 700 people.

The resuscitation of Black opposition to apartheid under a new band of leaders coincided with the decline of the economy. After the Soweto uprising, foreign investors fled South Africa in their droves, laying bare the fundamental flaws of the apartheid government’s dependence on cheap labour and mining and its point-blank refusal to meaningfully educate people of colour. The apartheid government spent about 12 times more per child on white schoolchildren than it did on Black ones.

By the 1980s, even the apartheid government could see something had to change, and in 1983, Prime Minister PW Botha announced plans to include multiracial and Indian South Africans, but not Black South Africans, in a new “tricameral” parliament. His plan backfired spectacularly, uniting the opposition like never before under the newly formed United Democratic Front (UDF). One of the UDF’s key demands was the unconditional release of all political prisoners, especially Mandela. Soon after its launch in August 1983, the UDF numbered almost 1,000 different organisations from all segments of South African society. Botha didn’t know what had hit him.

When, in 1984, Oliver Tambo, the ANC’s exiled leader, asked his supporters to “make South Africa ungovernable”, the townships rose up. Things got so bad in 1985 that Botha declared a state of emergency – but this was also the year in which tentative secret talks with Mandela began.

An icon re-emerges

“In the late 1970s, you started getting occasional demands that Mandela be released,” Southall said. By the mid-1980s, “Free Nelson Mandela” became a constant and global refrain with the “I am prepared to die” statement being quoted at rallies and emblazoned on T-shirts. “On one level, the ANC ‘invented’ this version of Mandela,” Southall said. “Until 1976, the apartheid government had done a very good job of erasing him from public memory.”

What might have happened if Mandela had been sentenced to death at Rivonia? One does not need to look far for a possible answer. The other poster boy of the global anti-apartheid movement in the 1980s was Steve Biko (subject of the Peter Gabriel hit song), the young leader of the Black Consciousness movement, who had been tortured to death by apartheid police in 1977. “You can also have myths develop when you execute people,” Simpson said. “If they had executed Mandela, he would have been a different icon in a different struggle.”

A dream realised

On February 11, 1990, Mandela was released from prison. From the balcony of Cape Town City Hall, he addressed his supporters for the first time since Rivonia. He opened his speech by saying: “I stand here before you not as a prophet but as a humble servant of you, the people. Your tireless and heroic sacrifices have made it possible for me to be here today. I, therefore, place the remaining years of my life in your hands.”

He ended by quoting the final lines of his 1964 statement from the dock, explaining that “they are true today as they were then.” Over the course of the next decade, as Mandela first navigated the treacherous path to democracy and then served as the country’s first democratically elected president, he lived out his vision of a “democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities”.

When the ANC’s Chris Hani was assassinated by an apartheid supporter in 1993, Mandela assumed the moral leadership of the country by urging his incensed supporters not to derail the peace process. After becoming president, he engaged in numerous public shows of reconciliation: He went for tea with the widow of slain apartheid Prime Minister Verwoerd, and he donned the Springbok rugby jersey (for many, a symbol of white supremacy) when he presented the almost entirely white South African team with the World Cup trophy in 1995.

When Mandela died in 2013, US President Barack Obama spoke at his memorial, famously – and predictably – quoting the final paragraph of the statement from the dock at Rivonia. By that stage, there were already some in South Africa who felt that Mandela was a “sellout” because he had been too forgiving of whites during the transition.

Now, more than a decade later as inequality continues to plague the country and South Africa stands on the cusp of its most competitive general election in 30 years of democracy, it is common to hear young Black South Africans accuse Mandela of selling out . Southall does not take such claims too seriously: “People who say he’s a sellout are either too young or too forgetful to appreciate how close we came to civil war. Mandela played a huge role in pulling off the peaceful transition.”

“Now, after 30 years of democracy, there is still a tension between white domination and Black domination,” Simpson said. “South Africa is not what Mandela dreamed of. He might be turning in his grave, but we can’t forget that many of the policies that have gone wrong were introduced by him. He might have turned things around, but he might have not.”

“You can’t blame Mandela for where we are now,” Southall said. “There are individual things he got wrong. But he also got a lot of things right.”

Mandela’s is one of the 12 remarkable lives covered in Nick Dall’s recent book, Legends: People Who Changed South Africa for the Better, co-written with Matthew Blackman.

Home Essay Examples Politics Nelson Mandela

The Rhetorical Analysis of Nelson Mandela’s “I Am Prepared To Die Speech”

- Category Politics

- Subcategory World Leaders

- Topic Nelson Mandela

Nelson Mandela’s “I Am Prepared to Die Speech” focuses on the struggle for equal rights of African American’s in South Africa. Throughout his speech he mentions universal themes such as the use of violence, discrimination, and equality. Since the speech was delivered during Mandela’s defense trial, the official intention of the speaker was to address the accusations brought against, however, the Mandela’s broader intention was to expose the injustices of the government and to gain national and international support for the cause of equal rights for his people.

Mandela wastes no time to create ethos in his speech, by starting to establish it from the very beginning. He starts off by claiming that he is the “First Accused” and in which he clearly portrays a persona for his audience to view him as, such as he is the first of many. He then chooses to clarify the fact that he holds a “Bachelor’s Degree in Arts” and that he has “practiced as an attorney” for many years. By doing this, Mandela uses ethos to create credibility and to give him a reliable platform from which he can base the rest of his argument to the audience.

Our writers can write you a new plagiarism-free essay on any topic

After establishing his credibility, Mandela continues on to say he is a “convicted prisoner serving five years” for “leaving the country without a permit” and by making his statement he reminds the people of South Africa of the foolishness of his conviction, a theme which he continues to push on throughout the entirety of his speech. By doing so he appeals to logos by planting the idea that the South African government has made questionable judgment calls in the past and can continue to make them. Mandela then appeals to logos and pathos by claiming that he was “one of the persons who helped to form Umkhonto” and that he “did so for two reasons.” By stating the charges made against him and defending his reasoning in doing so, Mandela further establishes his credibility by being honest and relating to the audience in the aspect that they would do the same if they were in his position.

Mandela’s effectively managed to give a speech that altered the movement he fought so hard for, but unfortunately it wasn’t enough to convince court officials of his innocence. It was an expected verdict seeing as though it is not a democratic state and government officials were against his movement. Throughout the speech he made sure to discredit the government and used them as the reasoning for all the charges against him. Mandela was a successful advocate for his movement but did not advocate well in the battle for his innocence.

We have 98 writers available online to start working on your essay just NOW!

Related Topics

Related essays.

By clicking "Send essay" you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

By clicking "Receive essay" you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

We can edit this one and make it plagiarism-free in no time

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

Sample details

Related topics.

- A Worn Path

- Lamb to The Slaughter

- The Painted Door

- Waiting For Godot

- The Landlady

- man's search for meaning

- Short Story

- The Necklace

- the wife of bath's tale

- Gospel of Mark

Nelson Mandela’s Speech “I Am Prepared to Die” Analysis

Nelson Mandela was charged for opposing the white authorities of South Africa in the 1960s, and gave a powerful defence speech titled I am Prepared to Die at his trial. Mandela used literary devices such as anecdotes, facts, statistics and allusions to support his defence. He stated that he hoped to make a difference in his people’s freedom, and presented himself as a Bachelor’s Degree holder, former lawyer and convicted captive. Mandela used statistics to show that more than 85,000 people were arrested for resisting apartheid laws, 70% of South Africans were not entitled to vote, and 69 unarmed Africans died at Sharpeville. Despite his powerful speech, Mandela was sentenced to life in prison and was released at the age of 71 in 1990. Nonetheless, his defence speech was persuasive and effective in presenting his case.

In 1962-1964. Nelson Mandela was charged for opposing the white authorities of South Africa. high lese majesty. sabotage. and the confederacy to subvert the authorities. In his defence. Mandela gave a address titled “I am Prepared to Die” at his test. This address is powerful and full of literary devices. In parts of this potent address he utilizes facts. statistics. and allusions as a tool to his defence. In the beginnings of his address he uses an anecdote. which is a short interesting narrative about a existent incident or individual. Here Mandela states that as immature male child in Transkei he listened to the seniors of his folk stating narratives of how it used to be. and of wars their ascendants fought against the homeland. and names such as Dingane. Bambata. Hinsta. and Makana were praised all over the African state.

He uses this to clarify that he hoped to assist his people and do a difference in their freedom. As of the factual parts he states within them. that he admits he was one of the people who helped to organize Umkhonto we Sizwe until he was arrested in August 1962. holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Arts and practiced as an lawyer in Johannesburg. a convicted captive functioning five old ages. and stating that more than 85. 000 people defied the apartheid Torahs and went to imprison. With more facts throughout the address. it gave Mandela more of a concluding to non be convicted. As of the statistical parts of this address he stated that more than 85. 000 people were arrested for withstanding the apartheid Torahs. adaging that 70 per centum of South Africa were non entitled to vote. besides saying that soixante-neuf unarmed Africans died at Sharpeville. These statistics gave Mandela more border to his defence and supported him.

Though Mandela’s address was intense it wasn’t adequate to happen him guiltless. He was sentenced to life. which he was released at 71 old ages of age. on February 11. 1990. Yet I still find that this address was powerful. The literary devices gave him border and his grounds was right.

Cite this page

https://graduateway.com/nelson-mandelas-speech-i-am-prepared-to-die-essay-2244-essay/

You can get a custom paper by one of our expert writers

- Affordable Care Act

- American Literature

- Protagonist

- The Yellow Wallpaper

- The Souls of Black Folk

Check more samples on your topics

An analysis of nelson mandela’s speech.

Nelson Mandela

Explanation of Context of Speech: Nelson Mandela spoke his "l am prepared to die" speech, when he was sentenced in the Rivonia Trial. Mandela was charged for opposing the White Government of South Africa, charges of sabotage, high treason, and threats to overthrow the South African Government. The purpose of the speech was to

Nelson Mandela Monologue – Speech

At school, the government spent approximately 6 times as much on a white student as they did on an African student. To the Nationalists, the African was biologically ignorant and lazy and no amount of education could fix that. When I was a boy, rarely ever came across a white man. To me, the whites

“Glory and Hope” by Nelson Mandela Analysis

He conveys his appreciation and message through his word choice, tone, sentence structure, and use of rhetorical devices. Nelson Mandela's word choice helps him convey his gratitude towards the audience and message that they must continue to work together to build and better society. He begins by addressing his audience with "Your Majesties, Your Highnesses,

Leadership and Nelson Mandela Analysis

To give a complete analysis to this movie from the prospective of Nelson Mandela being a leader in the sports world in this essay will explain the different styles of leadership Nelson Mandela implemented, group dynamics, communication, managing difficulties, issues of diversity. All of these where present in this movie and a direct correlation to

Life and Career of Nelson Mandela

Nelson Mandela Introduction Nelson Mandela was born to Chief Gadla Henry Mphakanyiswa and his third wife, Nosekani Fanny, at the Eastern Cape village of Mvezo. When his father died and young Mandela was taken into the care of his uncle Jongintaba Dalindyebo, who was an acting regent of the old Tembu, there was a profound turn in

A Comparative Study of Nelson Mandela and Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Following the First World War Germanys economy began to fail, the German people were disgruntled with their current government and went in search of nother leader. They were looking for a man that had the mettle to lead their country out of the bad times and into the good. As the world slipped into an

Nelson Mandela: Did He Deserve 27 Years in Prison?

Nelson Mandela was a writer, a non-US president, and a civil rights activist. He was known as a nonviolent anti-apartheid activist, politician, and philanthropist. Mandela directed a campaign of peaceful, nonviolent defiance against the South African government and it’s racist policies. He became South Africa’s first black president, in office from 1994 to 1999. Nelson

Nelson Mandela Is Remembered as a Political Leader

To the average person, Nelson Mandela is remembered as a political leader who eventually was president of his homeland of South Africa. However, behind his seemingly ever smiling face, lied a life of struggles and injustice. Before Mandela could become the great leader that he was, he endured numerous trials and tribulations. Mandela was born

The Song About Nelson Mandela

This song is “Glorious years” The song is about Nelson Mandela, the song was from Wong Ka Kui, he was a Honk Kong Musician, songwriter, and singer. This song was Wong wrote it for Mandela, he was deeply moved by Mandela. When he was released from prison in 1990, he wrote the lyrics for him

Hi, my name is Amy 👋

In case you can't find a relevant example, our professional writers are ready to help you write a unique paper. Just talk to our smart assistant Amy and she'll connect you with the best match.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

NPR editor Uri Berliner resigns with blast at new CEO

David Folkenflik

Uri Berliner resigned from NPR on Wednesday saying he could not work under the new CEO Katherine Maher. He cautioned that he did not support calls to defund NPR. Uri Berliner hide caption

Uri Berliner resigned from NPR on Wednesday saying he could not work under the new CEO Katherine Maher. He cautioned that he did not support calls to defund NPR.

NPR senior business editor Uri Berliner resigned this morning, citing the response of the network's chief executive to his outside essay accusing NPR of losing the public's trust.

"I am resigning from NPR, a great American institution where I have worked for 25 years," Berliner wrote in an email to CEO Katherine Maher. "I respect the integrity of my colleagues and wish for NPR to thrive and do important journalism. But I cannot work in a newsroom where I am disparaged by a new CEO whose divisive views confirm the very problems at NPR I cite in my Free Press essay."

NPR and Maher declined to comment on his resignation.

The Free Press, an online site embraced by journalists who believe that the mainstream media has become too liberal, published Berliner's piece last Tuesday. In it, he argued that NPR's coverage has increasingly reflected a rigid progressive ideology. And he argued that the network's quest for greater diversity in its workforce — a priority under prior chief executive John Lansing – has not been accompanied by a diversity of viewpoints presented in NPR shows, podcasts or online coverage.

Later that same day, NPR pushed back against Berliner's critique.

"We're proud to stand behind the exceptional work that our desks and shows do to cover a wide range of challenging stories," NPR's chief news executive, Edith Chapin, wrote in a memo to staff . "We believe that inclusion — among our staff, with our sourcing, and in our overall coverage — is critical to telling the nuanced stories of this country and our world."

Yet Berliner's commentary has been embraced by conservative and partisan Republican critics of the network, including former President Donald Trump and the activist Christopher Rufo.

Rufo is posting a parade of old social media posts from Maher, who took over NPR last month. In two examples, she called Trump a racist and also seemed to minimize the effects of rioting in 2020. Rufo is using those to rally public pressure for Maher's ouster, as he did for former Harvard University President Claudine Gay .

Others have used the moment to call for the elimination of federal funding for NPR – less than one percent of its roughly $300 million annual budget – and local public radio stations, which derive more of their funding from the government.

NPR names tech executive Katherine Maher to lead in turbulent era

Berliner reiterated in his resignation letter that he does not support such calls.

In a brief interview, he condemned a statement Maher issued Friday in which she suggested that he had questioned "whether our people are serving our mission with integrity, based on little more than the recognition of their identity." She called that "profoundly disrespectful, hurtful, and demeaning."

Berliner subsequently exchanged emails with Maher, but she did not address those comments.

"It's been building up," Berliner said of his decision to resign, "and it became clear it was on today."

For publishing his essay in The Free Press and appearing on its podcast, NPR had suspended Berliner for five days without pay. Its formal rebuke noted he had done work outside NPR without its permission, as is required, and shared proprietary information.

(Disclosure: Like Berliner, I am part of NPR's Business Desk. He has edited many of my past stories. But he did not see any version of this article or participate in its preparation before it was posted publicly.)

Earlier in the day, Berliner forwarded to NPR editors and other colleagues a note saying he had "never questioned" their integrity and had been trying to raise these issues within the newsroom for more than seven years.

What followed was an email he had sent to newsroom leaders after Trump's 2016 win. He wrote then: "Primarily for the sake of our journalism, we can't align ourselves with a tribe. So we don't exist in a cocoon that blinds us to the views and experience of tens of millions of our fellow citizens."

Berliner's critique has inspired anger and dismay within the network. Some colleagues said they could no longer trust him after he chose to publicize such concerns rather than pursue them as part of ongoing newsroom debates, as is customary. Many signed a letter to Maher and Edith Chapin, NPR's chief news executive. They asked for clarity on, among other things, how Berliner's essay and the resulting public controversy would affect news coverage.

Yet some colleagues privately said Berliner's critique carried some truth. Chapin also announced monthly reviews of the network's coverage for fairness and diversity - including diversity of viewpoint.

She said in a text message earlier this week that that initiative had been discussed long before Berliner's essay, but "Now seemed [the] time to deliver if we were going to do it."

She added, "Healthy discussion is something we need more of."

Disclosure: This story was reported and written by NPR Media Correspondent David Folkenflik and edited by Deputy Business Editor Emily Kopp and Managing Editor Gerry Holmes. Under NPR's protocol for reporting on itself, no NPR corporate official or news executive reviewed this story before it was posted publicly.

- Katherine Maher

- uri berliner

Advancing social justice, promoting decent work ILO is a specialized agency of the United Nations

The ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work , adopted in 1998 and amended in 2022, is an expression of commitment by governments, employers' and workers' organizations to uphold basic human values - values that are vital to our social and economic lives. It affirms the obligations and commitments that are inherent in membership of the ILO, namely:

- freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining;

- the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labour;

- the effective abolition of child labour;

- the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation; and

- a safe and healthy working environment.

Read the full text of the Declaration

Follow-up to the Declaration

The commitment is supported by a Follow-up procedure. The aim of the follow-up is to encourage the efforts made by the Members of the Organization to promote the fundamental principles and rights enshrined in the Constitution of the ILO and the Declaration of Philadelphia and reaffirmed in the 1998 Declaration.

This follow-up has two aspects based on existing procedures:

- The Annual follow-up concerning non-ratified fundamental Conventions will entail merely some adaptation of the present modalities of application of article 19, paragraph 5(e), of the Constitution.

- The Global Report on fundamental principles and rights at work that will serve to inform the recurrent discussion at the Conference on the needs of the Members, the ILO action undertaken, and the results achieved in the promotion of the fundamental principles and rights at work.

There is a third way to give effect to the Declaration, the Technical Cooperation Projects which are designed to address identifiable needs in relation to the Declaration and to strengthen local capacities thereby translating principles into practice.

Annual Review under the follow-up to the Declaration

Member States that have not ratified one or more of the fundamental ILO instruments directly relating to the principles and rights stated in the Declaration, including the Protocol of 2014 to the Forced Labour Convention, 1930 , are asked each year to report on the status of the relevant rights and principles within their borders. The reporting process provides governments and social partners with an opportunity to state what measures have been taken towards achieving respect for the Declaration, as well as to note impediments to ratification of the relevant instruments and areas where assistance may be required.

On the basis of the governments’ annual reports and observations by employers’ and workers’ organizations, the International Labour Office prepares and updates country baselines , which serve as a starting point to evaluate the extent to which the fundamental principles and rights at work are given effect in practice. The baselines also aim at facilitating the governments’ future reporting obligations.

- See all country baselines under the 1998 Declaration Annual Review

Five Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work

Freedom of association and the right of collective bargaining

Elimination of forced or compulsory labour

Abolition of child labour

Elimination of discrimination at work

A safe and healthy working environment

Integrated Strategy on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work 2017-2023

The teeth of the ILO - The impact of the 1998 ILO Declaration on Fundamentals Principles and Rights at Work

More From Forbes

Cannabis rolling papers may pose health risks from heavy metals, study finds.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Blonde girl holding red joint

The lack of regulation on cannabis rolling papers may expose users to health risks due to the presence of unsafe quantities of heavy metals, according to a new study.

Researchers from Lake Superior State University in Michigan recently published a study in the journal ACS Omega in order to measure the heavy metal content in commercially available cannabis rolling papers.

They analyzed the elemental composition of 53 commercially available rolling papers and assessed the potential risks of exposure in comparison to established standards.

The findings showed that around one-quarter of the samples exceeded the recommended levels of copper for inhaled pharmaceuticals. Furthermore, certain cannabis rolling papers contain elevated levels of elements such as copper, chromium, and vanadium, which could pose health risks. The study also revealed that some cannabis rolling papers use copper-based coloring, potentially exposing users to unsafe levels of copper, mainly when used in large quantities.

In this context, repeated exposure to heavy metals through inhalation can accumulate in the body over time, causing health problems and increasing the risk of developing diseases.

The heavy metals in these papers originate from various sources, including residual chemicals from manufacturing, ink and dyes applied during production, and potentially contaminated plants used in papermaking if grown in polluted soil. Researchers also explained that recycled paper poses an even higher risk as extra chemicals are often added during the recycling process to enhance its appearance. These added chemicals may include lead, arsenic, cadmium, chromium, and zinc.

By analyzing the levels of 26 different elements in cannabis rolling papers, researchers compared the level of these elements with the standards established by various states in the U.S. and Canada for inhaled cannabis products. Although there are typically no specific regulations regarding the elemental content of rolling papers, this comparison provided insights into their potential contribution to consumer exposure.

The findings revealed significant disparities in regulations across different states, particularly concerning acceptable arsenic, cadmium, mercury, and lead levels. Even if rolling papers were subject to regulation akin to cannabis products, the limits for these elements varied widely between jurisdictions, sometimes by 20 to 50 times.

The Best Romantic Comedy Of The Last Year Just Hit Netflix

Apple iphone 16 unique all new design promised in new report, the world s best beers according to the 2024 world beer cup.

Researchers found that calcium was the most common element in rolling papers, probably because of additives used in making paper. They also found magnesium, sodium, potassium, aluminum, iron, manganese, barium, copper, and zinc.

The exceptionally high metal levels in some samples taken into exam pose potential risks for users, according to this study.

The authors of this study suspect that certain manufacturers used inks containing copper pigments. For instance, the blue cone showed an even distribution of copper and titanium on its surface, suggesting the use of copper-containing pigment. In contrast, they noted that the yellow and red cones lacked copper but contained other elements like titanium and strontium, commonly used in coloring.

Overall, the analysis showed that copper was present in the green, blue, and purple parts of the rainbow cone, with the highest amount in the blue part. Chromium was found in the gold-colored tip.

These results suggest health risks from copper-based pigments in some rolling papers when smoked due to the potential release of hazardous compounds during combustion.

This study highlights the concerning lack of regulations for rolling papers, raising worries about potential exposure to harmful elements like copper, particularly considering the medical use of cannabis by many users.

With varying cannabis laws across states and the federal government, there's a lack of unified guidance, and researchers suggested that states should collaborate to establish limits on toxic elements in cannabis and rolling papers based on their findings.

Researchers also suggested that manufacturing processes can exacerbate exposure risks, especially when using copper-based inks, and encouraged manufacturers to eliminate their use, which could significantly reduce copper levels in papers.

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

Watch CBS News

Israeli strikes in Rafah kill 18, mostly children, Palestinian officials say

Updated on: April 21, 2024 / 10:07 PM EDT / CBS/AP

Israeli strikes on the southern Gaza city of Rafah overnight killed 18 people, including 14 children, health officials said Sunday. Meanwhile, the United States was on track to approve billions of dollars of additional military aid to its close ally.

Israel has carried out near-daily air raids on Rafah, where more than half of Gaza's population of 2.3 million has sought refuge from fighting elsewhere. It has also vowed to expand its ground offensive to the city on the border with Egypt despite international calls for restraint, including from the U.S.

The House of Representatives approved a $26 billion aid package on Saturday that includes around $9 billion in humanitarian assistance for Gaza. Democratic Sen. Mark Warner of Virginia, the chair of the Senate Intelligence Committee, told "Face the Nation" on Sunday that he believed the Senate would take up the legislation this week. It still needs senators' approval and President Biden's signature.

"We have to be ready to be prepared for our national security interests, not only in Ukraine and Russia, also in terms of military assistance to Israel, but with additional humanitarian aid for the Palestinians who are in such great challenges," Warner said Sunday.

The first strike killed a man, his wife and their 3-year-old child, according to the nearby Kuwaiti Hospital, which received the bodies. Among the dead was a pregnant woman in her 27th week, according to CBS News' team on the ground. Doctors were able to keep her baby alive as of Sunday morning.

The second strike killed 13 children and two women, all from the same family, according to hospital records. An airstrike in Rafah the night before killed nine people, including six children.

For over two months, Israel has warned it could send troops into Rafah. The Group of 7, or G7, countries that include the U.S., Japan and the United Kingdom and whose foreign ministers met last week, warned that a full-scale operation there would have catastrophic consequences.

The Israel-Hamas war has killed over 34,000 Palestinians, according to local health officials, devastated Gaza's two largest cities and left a swath of destruction across the territory. Around 80% of the population have fled their homes to other parts of the besieged coastal enclave, which experts say is on the brink of famine.

The Israel-Hamas conflict, now in its seventh month, has sparked regional unrest pitting Israel and the U.S. against Iran and allied militant groups across the Middle East. Israel and Iran traded fire directly earlier this month, raising fears of all-out war between the longtime foes.

Tensions have also spiked in the Israeli-occupied West Bank. Israeli troops killed two Palestinians who the military says attacked a checkpoint with a knife and a gun near the southern West Bank town of Hebron early Sunday. The Palestinian Health Ministry said the two killed were 18 and 19 years old, from the same family. No Israeli forces were wounded, the army said.

In the West Bank city of Tulkarm, at least 14 Palestinians were killed as part of a two-day Israel Defense Force operation over the weekend. The IDF pulled out of the area on Saturday night, on a scale residents say they have never seen in this area before.

The U.S. has imposed new sanctions on West Bank settlers as the region has seen violence allegedly perpetrated by extremist settlers against Palestinians since the war in nearby Gaza began. A U.S. official told CBS News that since 2022, it has been investigating an IDF unit of ultra Orthodox soldiers accused of human rights atrocities. An announcement is expected this week.

That unit is stationed in the West Bank. Media reports suggesting it could be blacklisted from receiving U.S. military aid prompted an angry outburst from Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who said sanctions against any IDF unit would be a moral low at a time when his country was fighting Hamas in Gaza.

The Palestinian Red Crescent rescue service meanwhile said it has recovered a total of 14 bodies from an Israeli raid in the Nur Shams urban refugee camp in the West Bank that began late Thursday. Those killed include three militants from the Islamic Jihad group and a 15-year-old boy. The military says it killed 10 militants in the camp and arrested eight suspects. Nine Israeli soldiers and officers were wounded.

In a separate incident in the West Bank, an Israeli man was wounded in an explosion Sunday, the Magen David Adom rescue service said. A video circulating online shows a man approaching a Palestinian flag that had been planted in a field. When he kicks it, it appears to trigger an explosive device.

At least 469 Palestinians have been killed by Israeli soldiers and settlers in the West Bank since the start of the war in Gaza, according to the Palestinian Health Ministry. Most have been killed during Israeli military arrest raids, which often trigger gunbattles, or in violent protests.