Rubric Best Practices, Examples, and Templates

A rubric is a scoring tool that identifies the different criteria relevant to an assignment, assessment, or learning outcome and states the possible levels of achievement in a specific, clear, and objective way. Use rubrics to assess project-based student work including essays, group projects, creative endeavors, and oral presentations.

Rubrics can help instructors communicate expectations to students and assess student work fairly, consistently and efficiently. Rubrics can provide students with informative feedback on their strengths and weaknesses so that they can reflect on their performance and work on areas that need improvement.

How to Get Started

Best practices, moodle how-to guides.

- Workshop Recording (Fall 2022)

- Workshop Registration

Step 1: Analyze the assignment

The first step in the rubric creation process is to analyze the assignment or assessment for which you are creating a rubric. To do this, consider the following questions:

- What is the purpose of the assignment and your feedback? What do you want students to demonstrate through the completion of this assignment (i.e. what are the learning objectives measured by it)? Is it a summative assessment, or will students use the feedback to create an improved product?

- Does the assignment break down into different or smaller tasks? Are these tasks equally important as the main assignment?

- What would an “excellent” assignment look like? An “acceptable” assignment? One that still needs major work?

- How detailed do you want the feedback you give students to be? Do you want/need to give them a grade?

Step 2: Decide what kind of rubric you will use

Types of rubrics: holistic, analytic/descriptive, single-point

Holistic Rubric. A holistic rubric includes all the criteria (such as clarity, organization, mechanics, etc.) to be considered together and included in a single evaluation. With a holistic rubric, the rater or grader assigns a single score based on an overall judgment of the student’s work, using descriptions of each performance level to assign the score.

Advantages of holistic rubrics:

- Can p lace an emphasis on what learners can demonstrate rather than what they cannot

- Save grader time by minimizing the number of evaluations to be made for each student

- Can be used consistently across raters, provided they have all been trained

Disadvantages of holistic rubrics:

- Provide less specific feedback than analytic/descriptive rubrics

- Can be difficult to choose a score when a student’s work is at varying levels across the criteria

- Any weighting of c riteria cannot be indicated in the rubric

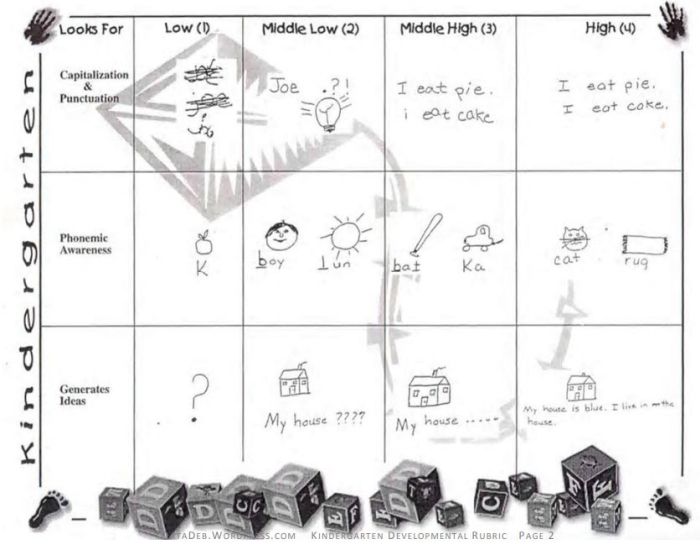

Analytic/Descriptive Rubric . An analytic or descriptive rubric often takes the form of a table with the criteria listed in the left column and with levels of performance listed across the top row. Each cell contains a description of what the specified criterion looks like at a given level of performance. Each of the criteria is scored individually.

Advantages of analytic rubrics:

- Provide detailed feedback on areas of strength or weakness

- Each criterion can be weighted to reflect its relative importance

Disadvantages of analytic rubrics:

- More time-consuming to create and use than a holistic rubric

- May not be used consistently across raters unless the cells are well defined

- May result in giving less personalized feedback

Single-Point Rubric . A single-point rubric is breaks down the components of an assignment into different criteria, but instead of describing different levels of performance, only the “proficient” level is described. Feedback space is provided for instructors to give individualized comments to help students improve and/or show where they excelled beyond the proficiency descriptors.

Advantages of single-point rubrics:

- Easier to create than an analytic/descriptive rubric

- Perhaps more likely that students will read the descriptors

- Areas of concern and excellence are open-ended

- May removes a focus on the grade/points

- May increase student creativity in project-based assignments

Disadvantage of analytic rubrics: Requires more work for instructors writing feedback

Step 3 (Optional): Look for templates and examples.

You might Google, “Rubric for persuasive essay at the college level” and see if there are any publicly available examples to start from. Ask your colleagues if they have used a rubric for a similar assignment. Some examples are also available at the end of this article. These rubrics can be a great starting point for you, but consider steps 3, 4, and 5 below to ensure that the rubric matches your assignment description, learning objectives and expectations.

Step 4: Define the assignment criteria

Make a list of the knowledge and skills are you measuring with the assignment/assessment Refer to your stated learning objectives, the assignment instructions, past examples of student work, etc. for help.

Helpful strategies for defining grading criteria:

- Collaborate with co-instructors, teaching assistants, and other colleagues

- Brainstorm and discuss with students

- Can they be observed and measured?

- Are they important and essential?

- Are they distinct from other criteria?

- Are they phrased in precise, unambiguous language?

- Revise the criteria as needed

- Consider whether some are more important than others, and how you will weight them.

Step 5: Design the rating scale

Most ratings scales include between 3 and 5 levels. Consider the following questions when designing your rating scale:

- Given what students are able to demonstrate in this assignment/assessment, what are the possible levels of achievement?

- How many levels would you like to include (more levels means more detailed descriptions)

- Will you use numbers and/or descriptive labels for each level of performance? (for example 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 and/or Exceeds expectations, Accomplished, Proficient, Developing, Beginning, etc.)

- Don’t use too many columns, and recognize that some criteria can have more columns that others . The rubric needs to be comprehensible and organized. Pick the right amount of columns so that the criteria flow logically and naturally across levels.

Step 6: Write descriptions for each level of the rating scale

Artificial Intelligence tools like Chat GPT have proven to be useful tools for creating a rubric. You will want to engineer your prompt that you provide the AI assistant to ensure you get what you want. For example, you might provide the assignment description, the criteria you feel are important, and the number of levels of performance you want in your prompt. Use the results as a starting point, and adjust the descriptions as needed.

Building a rubric from scratch

For a single-point rubric , describe what would be considered “proficient,” i.e. B-level work, and provide that description. You might also include suggestions for students outside of the actual rubric about how they might surpass proficient-level work.

For analytic and holistic rubrics , c reate statements of expected performance at each level of the rubric.

- Consider what descriptor is appropriate for each criteria, e.g., presence vs absence, complete vs incomplete, many vs none, major vs minor, consistent vs inconsistent, always vs never. If you have an indicator described in one level, it will need to be described in each level.

- You might start with the top/exemplary level. What does it look like when a student has achieved excellence for each/every criterion? Then, look at the “bottom” level. What does it look like when a student has not achieved the learning goals in any way? Then, complete the in-between levels.

- For an analytic rubric , do this for each particular criterion of the rubric so that every cell in the table is filled. These descriptions help students understand your expectations and their performance in regard to those expectations.

Well-written descriptions:

- Describe observable and measurable behavior

- Use parallel language across the scale

- Indicate the degree to which the standards are met

Step 7: Create your rubric

Create your rubric in a table or spreadsheet in Word, Google Docs, Sheets, etc., and then transfer it by typing it into Moodle. You can also use online tools to create the rubric, but you will still have to type the criteria, indicators, levels, etc., into Moodle. Rubric creators: Rubistar , iRubric

Step 8: Pilot-test your rubric

Prior to implementing your rubric on a live course, obtain feedback from:

- Teacher assistants

Try out your new rubric on a sample of student work. After you pilot-test your rubric, analyze the results to consider its effectiveness and revise accordingly.

- Limit the rubric to a single page for reading and grading ease

- Use parallel language . Use similar language and syntax/wording from column to column. Make sure that the rubric can be easily read from left to right or vice versa.

- Use student-friendly language . Make sure the language is learning-level appropriate. If you use academic language or concepts, you will need to teach those concepts.

- Share and discuss the rubric with your students . Students should understand that the rubric is there to help them learn, reflect, and self-assess. If students use a rubric, they will understand the expectations and their relevance to learning.

- Consider scalability and reusability of rubrics. Create rubric templates that you can alter as needed for multiple assignments.

- Maximize the descriptiveness of your language. Avoid words like “good” and “excellent.” For example, instead of saying, “uses excellent sources,” you might describe what makes a resource excellent so that students will know. You might also consider reducing the reliance on quantity, such as a number of allowable misspelled words. Focus instead, for example, on how distracting any spelling errors are.

Example of an analytic rubric for a final paper

Example of a holistic rubric for a final paper, single-point rubric, more examples:.

- Single Point Rubric Template ( variation )

- Analytic Rubric Template make a copy to edit

- A Rubric for Rubrics

- Bank of Online Discussion Rubrics in different formats

- Mathematical Presentations Descriptive Rubric

- Math Proof Assessment Rubric

- Kansas State Sample Rubrics

- Design Single Point Rubric

Technology Tools: Rubrics in Moodle

- Moodle Docs: Rubrics

- Moodle Docs: Grading Guide (use for single-point rubrics)

Tools with rubrics (other than Moodle)

- Google Assignments

- Turnitin Assignments: Rubric or Grading Form

Other resources

- DePaul University (n.d.). Rubrics .

- Gonzalez, J. (2014). Know your terms: Holistic, Analytic, and Single-Point Rubrics . Cult of Pedagogy.

- Goodrich, H. (1996). Understanding rubrics . Teaching for Authentic Student Performance, 54 (4), 14-17. Retrieved from

- Miller, A. (2012). Tame the beast: tips for designing and using rubrics.

- Ragupathi, K., Lee, A. (2020). Beyond Fairness and Consistency in Grading: The Role of Rubrics in Higher Education. In: Sanger, C., Gleason, N. (eds) Diversity and Inclusion in Global Higher Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore.

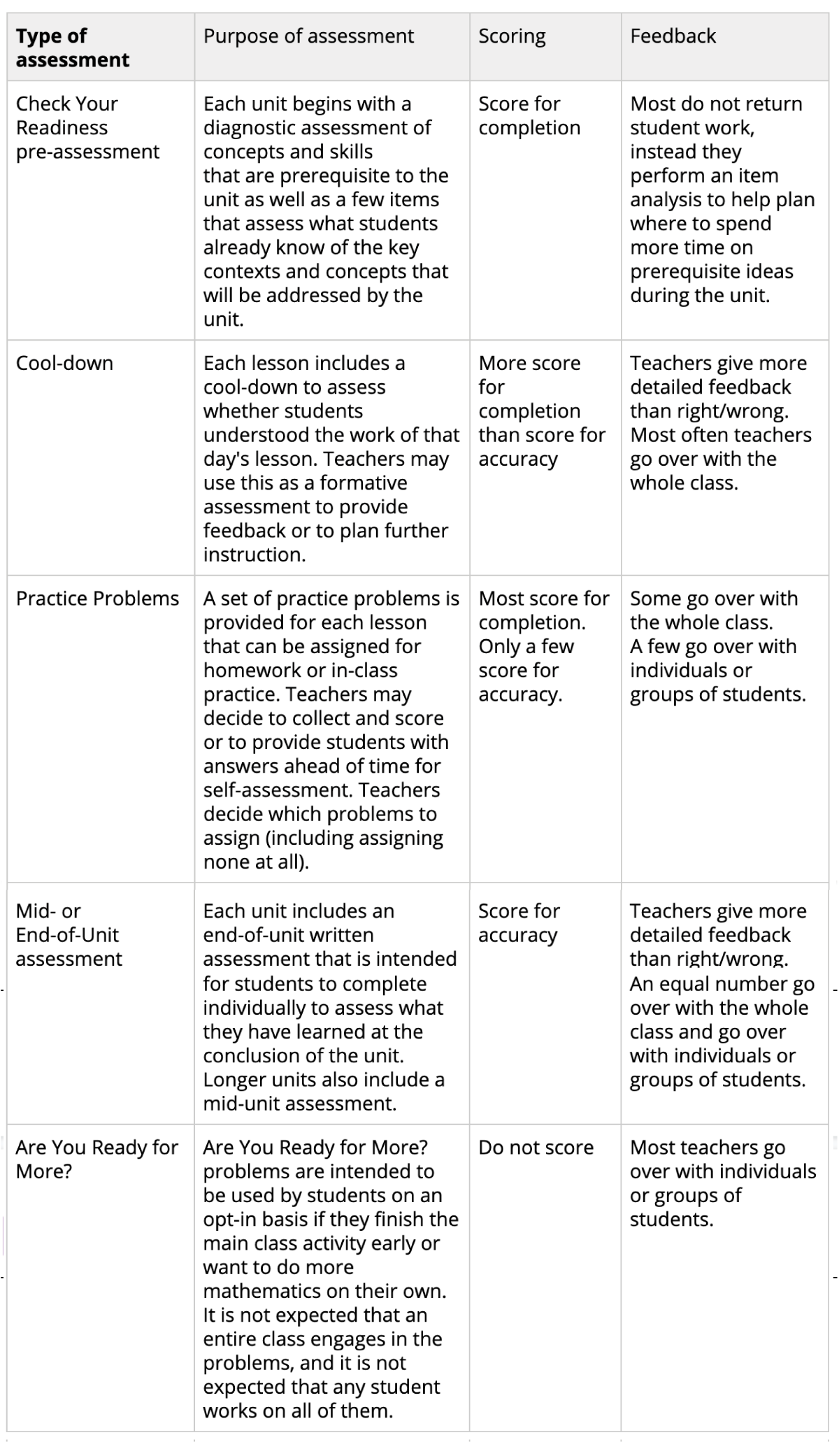

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

Free printable Mother's Day questionnaire 💐!

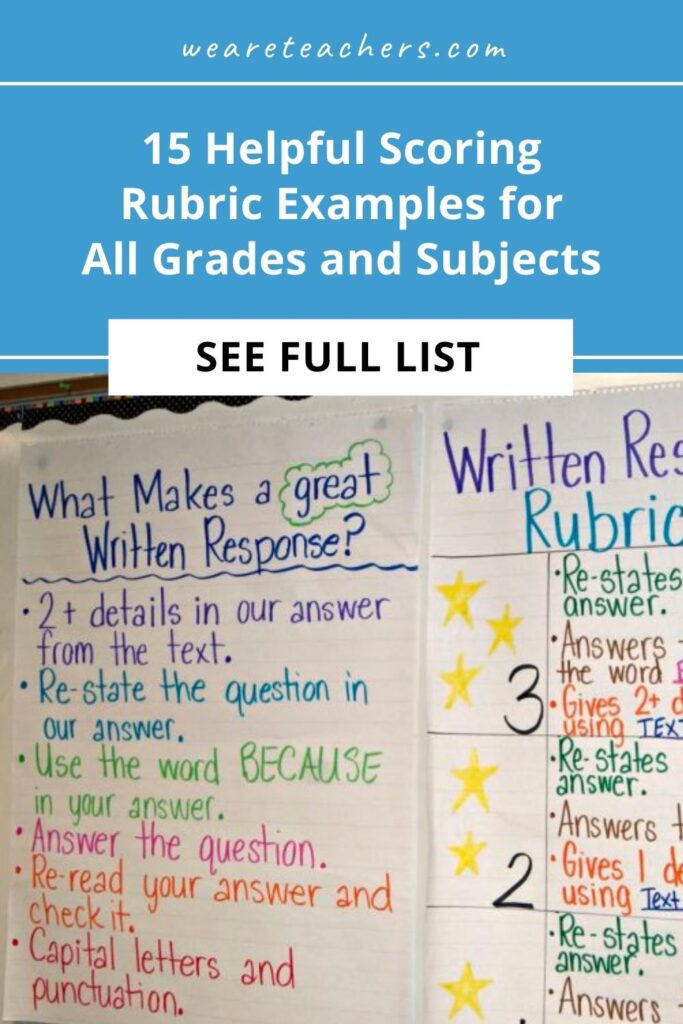

15 Helpful Scoring Rubric Examples for All Grades and Subjects

In the end, they actually make grading easier.

When it comes to student assessment and evaluation, there are a lot of methods to consider. In some cases, testing is the best way to assess a student’s knowledge, and the answers are either right or wrong. But often, assessing a student’s performance is much less clear-cut. In these situations, a scoring rubric is often the way to go, especially if you’re using standards-based grading . Here’s what you need to know about this useful tool, along with lots of rubric examples to get you started.

What is a scoring rubric?

In the United States, a rubric is a guide that lays out the performance expectations for an assignment. It helps students understand what’s required of them, and guides teachers through the evaluation process. (Note that in other countries, the term “rubric” may instead refer to the set of instructions at the beginning of an exam. To avoid confusion, some people use the term “scoring rubric” instead.)

A rubric generally has three parts:

- Performance criteria: These are the various aspects on which the assignment will be evaluated. They should align with the desired learning outcomes for the assignment.

- Rating scale: This could be a number system (often 1 to 4) or words like “exceeds expectations, meets expectations, below expectations,” etc.

- Indicators: These describe the qualities needed to earn a specific rating for each of the performance criteria. The level of detail may vary depending on the assignment and the purpose of the rubric itself.

Rubrics take more time to develop up front, but they help ensure more consistent assessment, especially when the skills being assessed are more subjective. A well-developed rubric can actually save teachers a lot of time when it comes to grading. What’s more, sharing your scoring rubric with students in advance often helps improve performance . This way, students have a clear picture of what’s expected of them and what they need to do to achieve a specific grade or performance rating.

Learn more about why and how to use a rubric here.

Types of Rubric

There are three basic rubric categories, each with its own purpose.

Holistic Rubric

Source: Cambrian College

This type of rubric combines all the scoring criteria in a single scale. They’re quick to create and use, but they have drawbacks. If a student’s work spans different levels, it can be difficult to decide which score to assign. They also make it harder to provide feedback on specific aspects.

Traditional letter grades are a type of holistic rubric. So are the popular “hamburger rubric” and “ cupcake rubric ” examples. Learn more about holistic rubrics here.

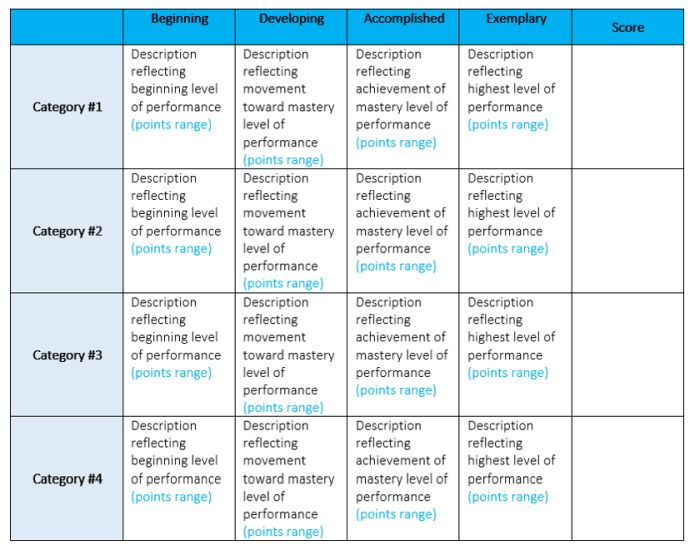

Analytic Rubric

Source: University of Nebraska

Analytic rubrics are much more complex and generally take a great deal more time up front to design. They include specific details of the expected learning outcomes, and descriptions of what criteria are required to meet various performance ratings in each. Each rating is assigned a point value, and the total number of points earned determines the overall grade for the assignment.

Though they’re more time-intensive to create, analytic rubrics actually save time while grading. Teachers can simply circle or highlight any relevant phrases in each rating, and add a comment or two if needed. They also help ensure consistency in grading, and make it much easier for students to understand what’s expected of them.

Learn more about analytic rubrics here.

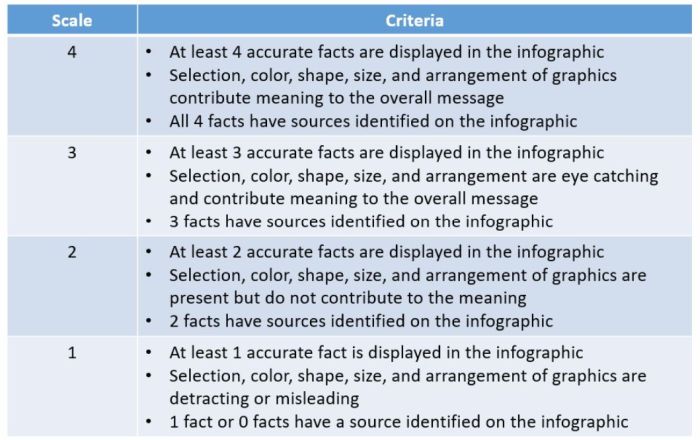

Developmental Rubric

Source: Deb’s Data Digest

A developmental rubric is a type of analytic rubric, but it’s used to assess progress along the way rather than determining a final score on an assignment. The details in these rubrics help students understand their achievements, as well as highlight the specific skills they still need to improve.

Developmental rubrics are essentially a subset of analytic rubrics. They leave off the point values, though, and focus instead on giving feedback using the criteria and indicators of performance.

Learn how to use developmental rubrics here.

Ready to create your own rubrics? Find general tips on designing rubrics here. Then, check out these examples across all grades and subjects to inspire you.

Elementary School Rubric Examples

These elementary school rubric examples come from real teachers who use them with their students. Adapt them to fit your needs and grade level.

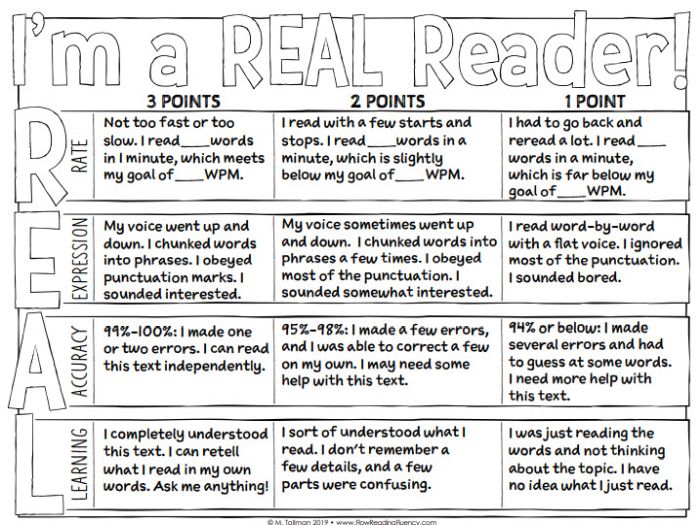

Reading Fluency Rubric

You can use this one as an analytic rubric by counting up points to earn a final score, or just to provide developmental feedback. There’s a second rubric page available specifically to assess prosody (reading with expression).

Learn more: Teacher Thrive

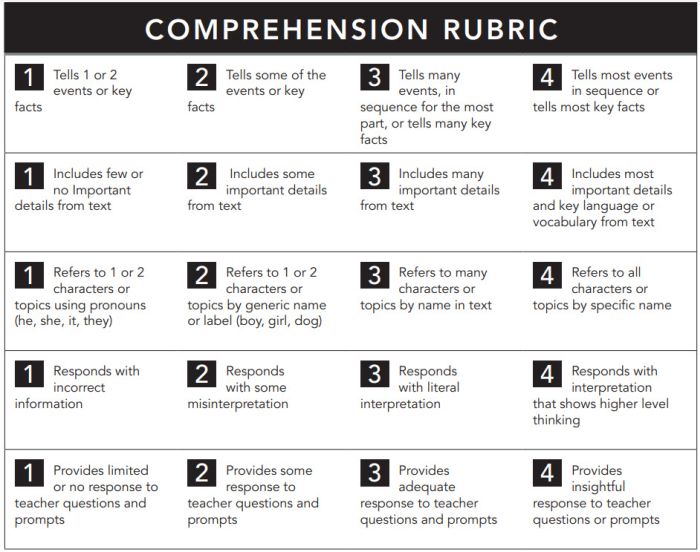

Reading Comprehension Rubric

The nice thing about this rubric is that you can use it at any grade level, for any text. If you like this style, you can get a reading fluency rubric here too.

Learn more: Pawprints Resource Center

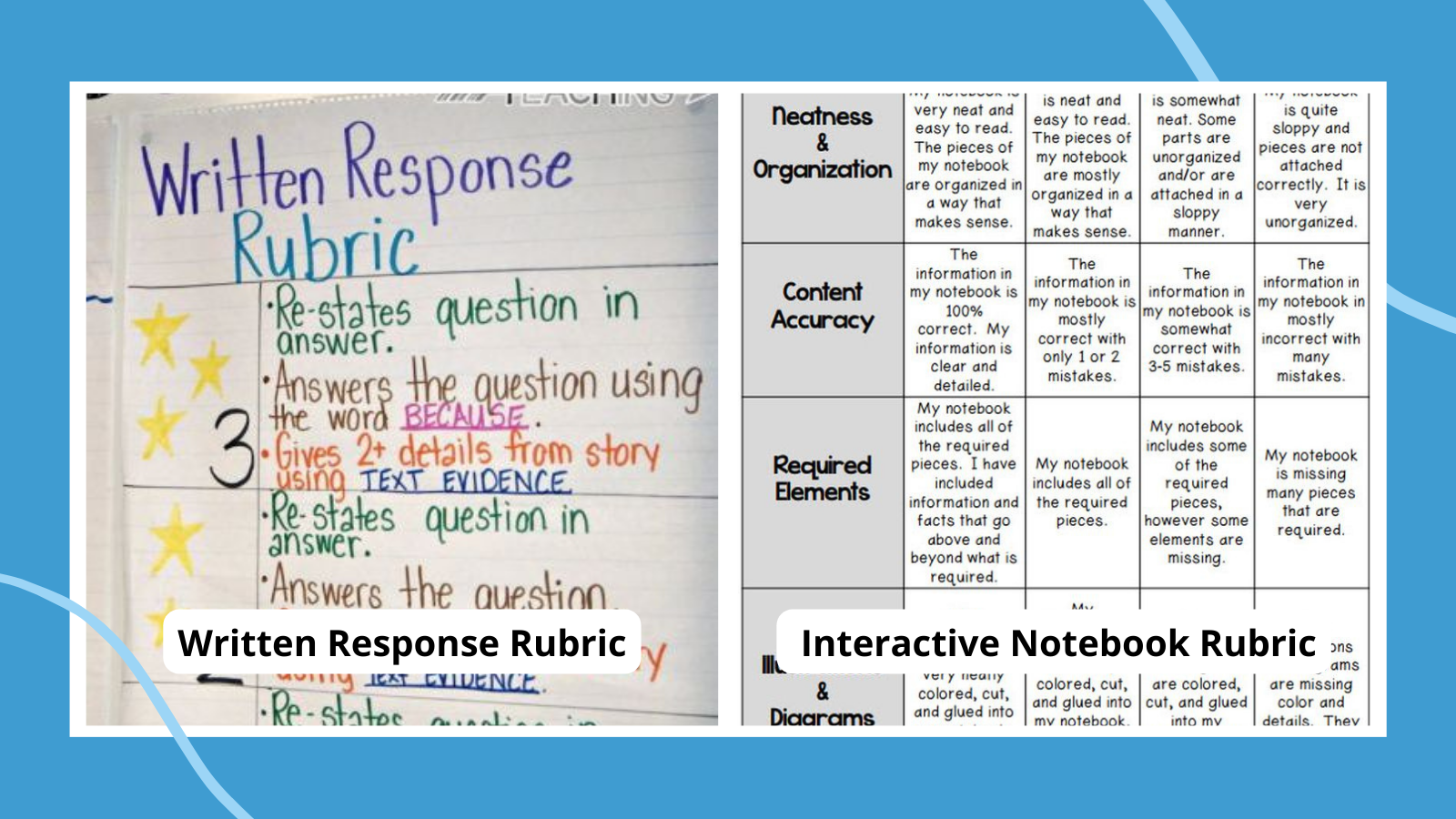

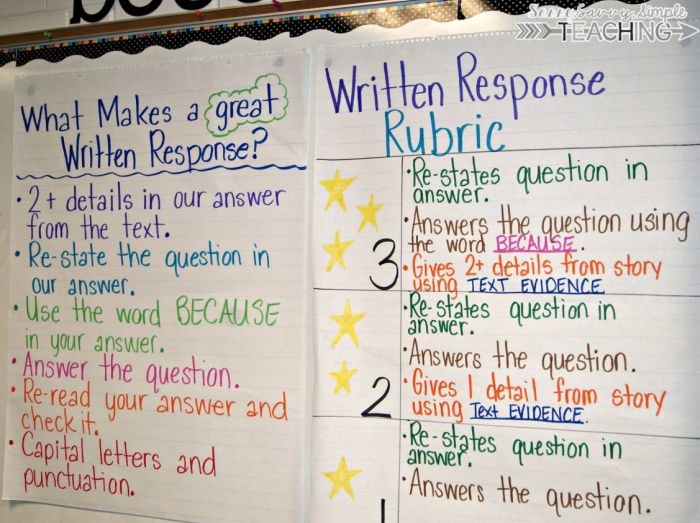

Written Response Rubric

Rubrics aren’t just for huge projects. They can also help kids work on very specific skills, like this one for improving written responses on assessments.

Learn more: Dianna Radcliffe: Teaching Upper Elementary and More

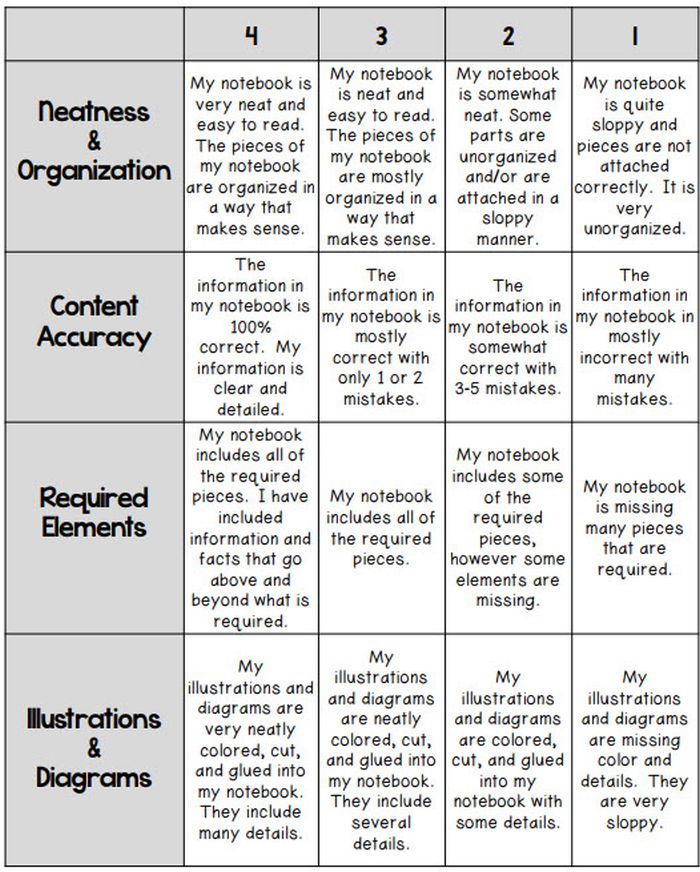

Interactive Notebook Rubric

If you use interactive notebooks as a learning tool , this rubric can help kids stay on track and meet your expectations.

Learn more: Classroom Nook

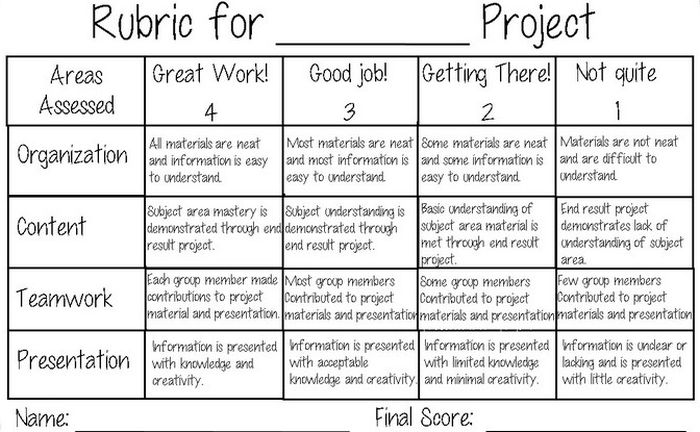

Project Rubric

Use this simple rubric as it is, or tweak it to include more specific indicators for the project you have in mind.

Learn more: Tales of a Title One Teacher

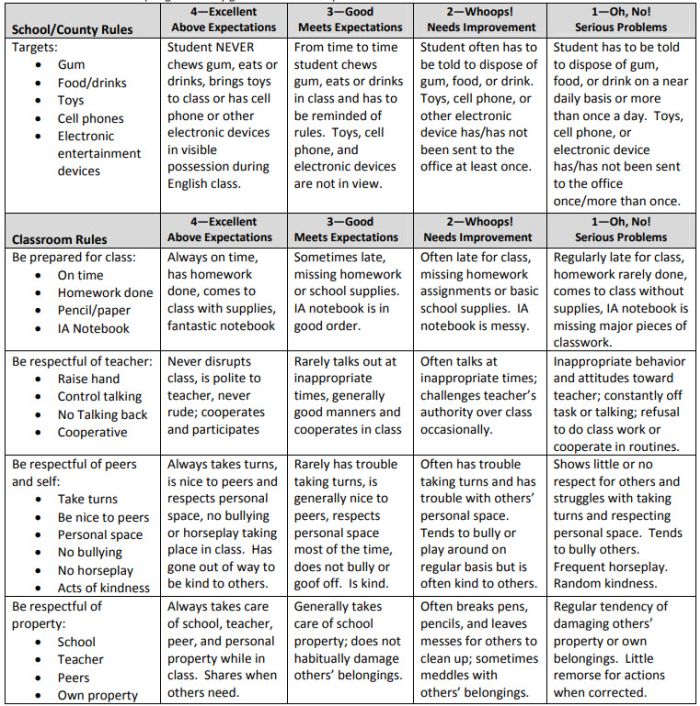

Behavior Rubric

Developmental rubrics are perfect for assessing behavior and helping students identify opportunities for improvement. Send these home regularly to keep parents in the loop.

Learn more: Teachers.net Gazette

Middle School Rubric Examples

In middle school, use rubrics to offer detailed feedback on projects, presentations, and more. Be sure to share them with students in advance, and encourage them to use them as they work so they’ll know if they’re meeting expectations.

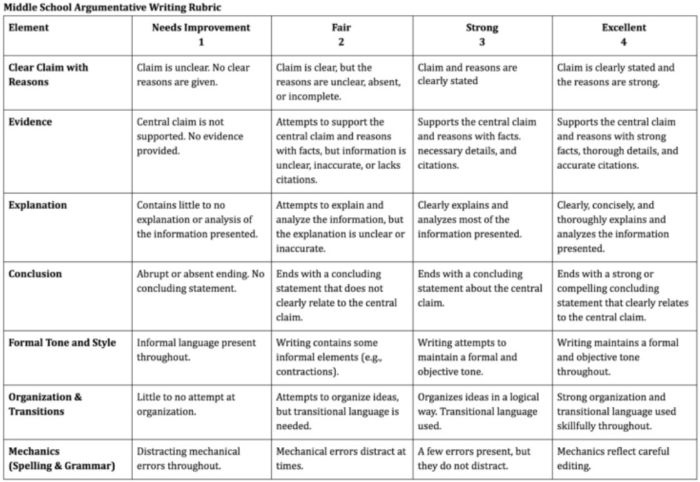

Argumentative Writing Rubric

Argumentative writing is a part of language arts, social studies, science, and more. That makes this rubric especially useful.

Learn more: Dr. Caitlyn Tucker

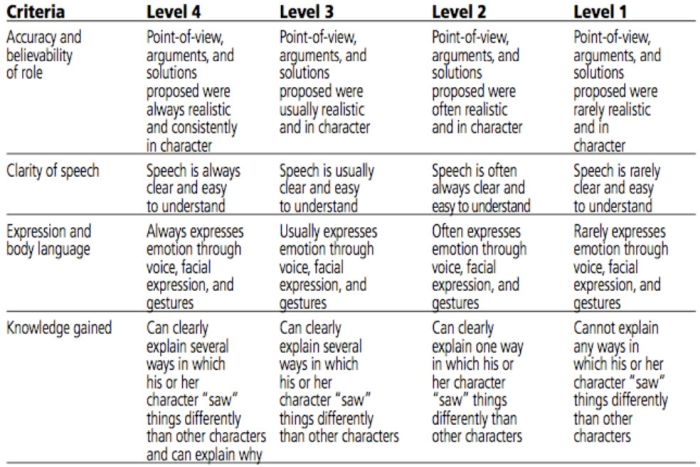

Role-Play Rubric

Role-plays can be really useful when teaching social and critical thinking skills, but it’s hard to assess them. Try a rubric like this one to evaluate and provide useful feedback.

Learn more: A Question of Influence

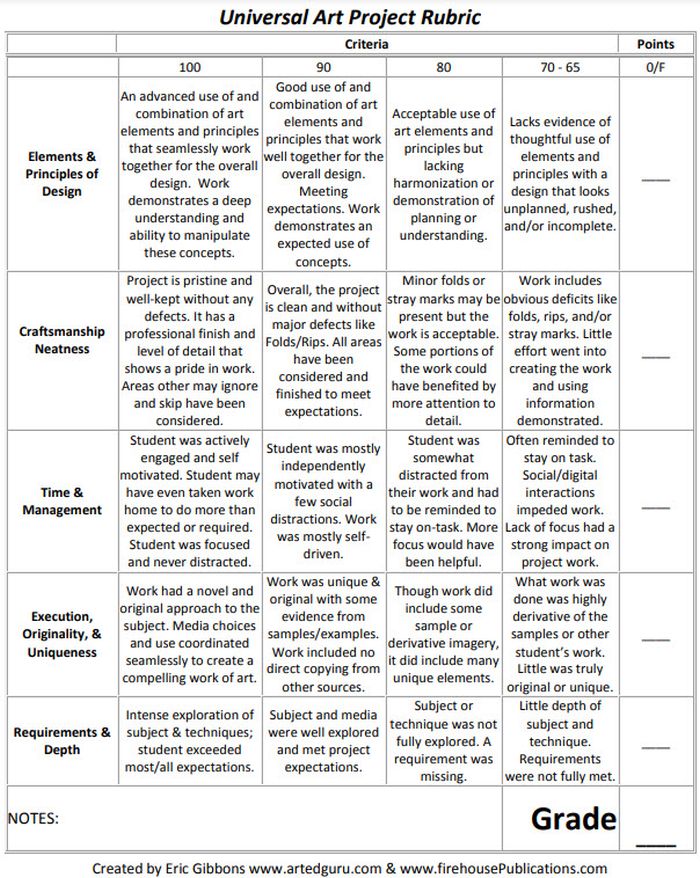

Art Project Rubric

Art is one of those subjects where grading can feel very subjective. Bring some objectivity to the process with a rubric like this.

Source: Art Ed Guru

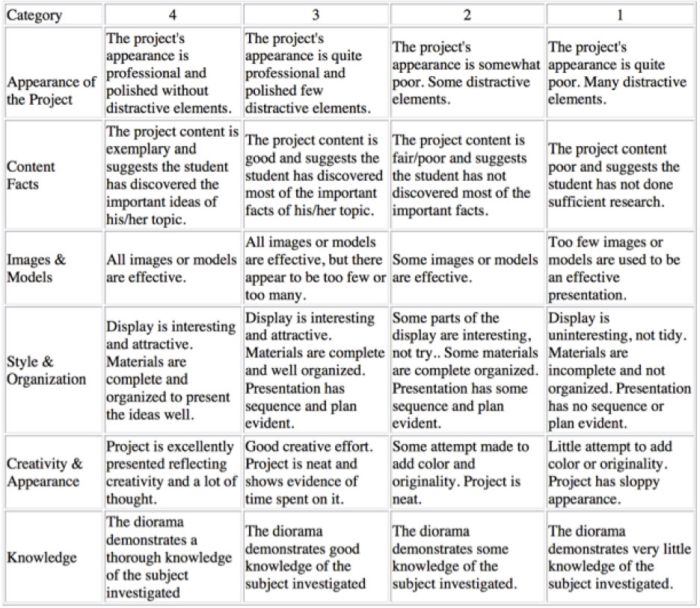

Diorama Project Rubric

You can use diorama projects in almost any subject, and they’re a great chance to encourage creativity. Simplify the grading process and help kids know how to make their projects shine with this scoring rubric.

Learn more: Historyourstory.com

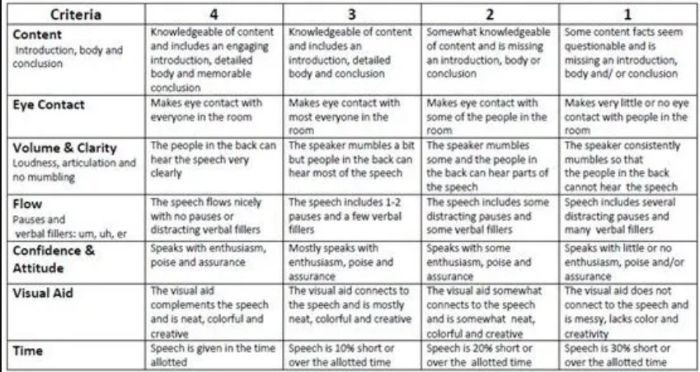

Oral Presentation Rubric

Rubrics are terrific for grading presentations, since you can include a variety of skills and other criteria. Consider letting students use a rubric like this to offer peer feedback too.

Learn more: Bright Hub Education

High School Rubric Examples

In high school, it’s important to include your grading rubrics when you give assignments like presentations, research projects, or essays. Kids who go on to college will definitely encounter rubrics, so helping them become familiar with them now will help in the future.

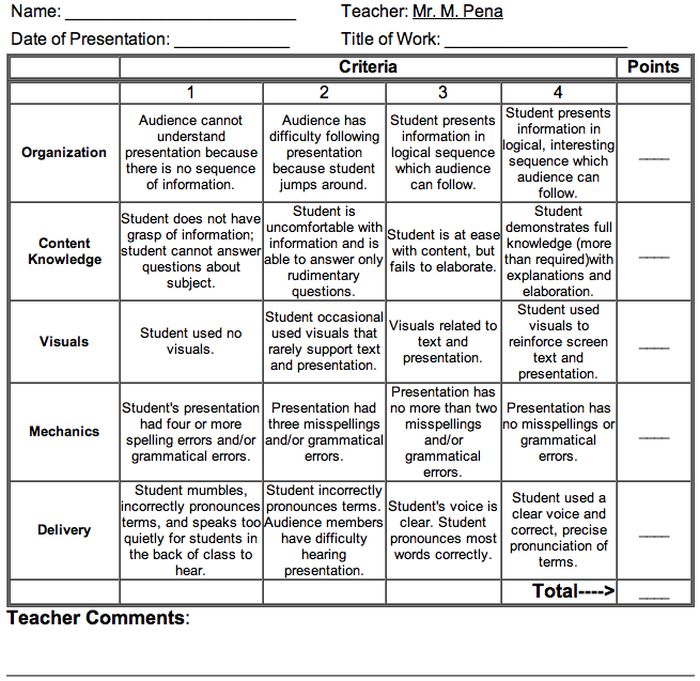

Presentation Rubric

Analyze a student’s presentation both for content and communication skills with a rubric like this one. If needed, create a separate one for content knowledge with even more criteria and indicators.

Learn more: Michael A. Pena Jr.

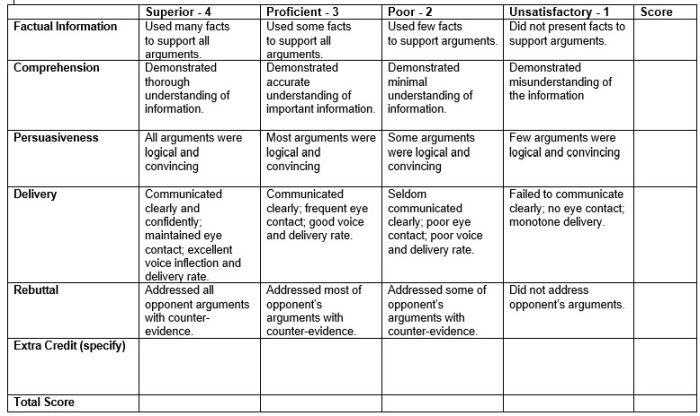

Debate Rubric

Debate is a valuable learning tool that encourages critical thinking and oral communication skills. This rubric can help you assess those skills objectively.

Learn more: Education World

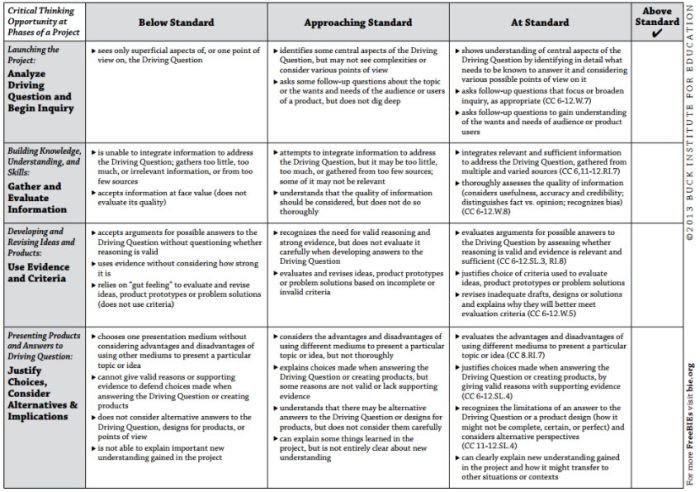

Project-Based Learning Rubric

Implementing project-based learning can be time-intensive, but the payoffs are worth it. Try this rubric to make student expectations clear and end-of-project assessment easier.

Learn more: Free Technology for Teachers

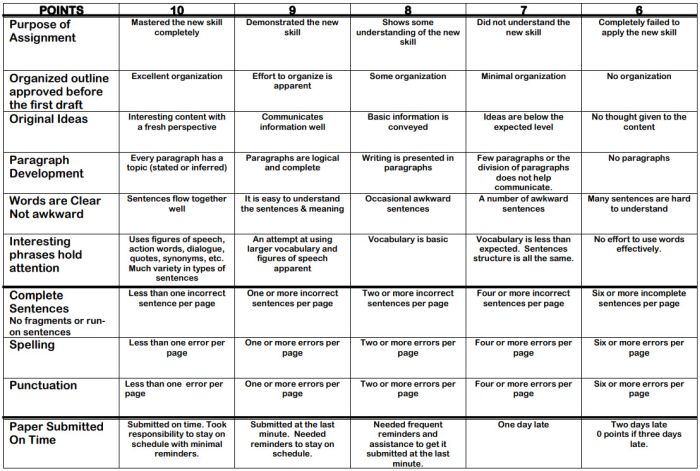

100-Point Essay Rubric

Need an easy way to convert a scoring rubric to a letter grade? This example for essay writing earns students a final score out of 100 points.

Learn more: Learn for Your Life

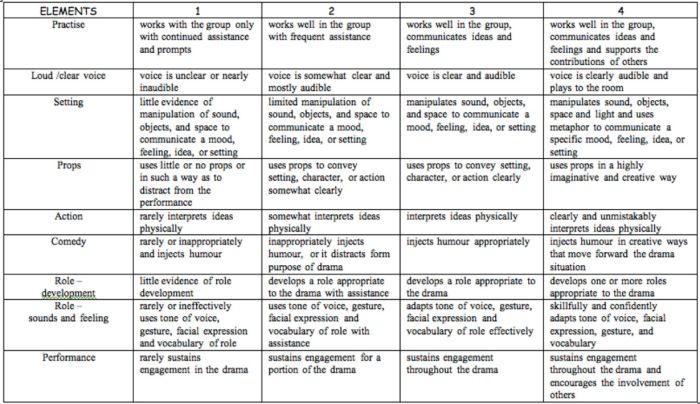

Drama Performance Rubric

If you’re unsure how to grade a student’s participation and performance in drama class, consider this example. It offers lots of objective criteria and indicators to evaluate.

Learn more: Chase March

How do you use rubrics in your classroom? Come share your thoughts and exchange ideas in the WeAreTeachers HELPLINE group on Facebook .

Plus, 25 of the best alternative assessment ideas ..

You Might Also Like

23 of the Best 3rd Grade Anchor Charts for Your Classroom

Our top picks to try in your classroom this year! Continue Reading

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

Eberly Center

Teaching excellence & educational innovation, creating and using rubrics.

A rubric is a scoring tool that explicitly describes the instructor’s performance expectations for an assignment or piece of work. A rubric identifies:

- criteria: the aspects of performance (e.g., argument, evidence, clarity) that will be assessed

- descriptors: the characteristics associated with each dimension (e.g., argument is demonstrable and original, evidence is diverse and compelling)

- performance levels: a rating scale that identifies students’ level of mastery within each criterion

Rubrics can be used to provide feedback to students on diverse types of assignments, from papers, projects, and oral presentations to artistic performances and group projects.

Benefitting from Rubrics

- reduce the time spent grading by allowing instructors to refer to a substantive description without writing long comments

- help instructors more clearly identify strengths and weaknesses across an entire class and adjust their instruction appropriately

- help to ensure consistency across time and across graders

- reduce the uncertainty which can accompany grading

- discourage complaints about grades

- understand instructors’ expectations and standards

- use instructor feedback to improve their performance

- monitor and assess their progress as they work towards clearly indicated goals

- recognize their strengths and weaknesses and direct their efforts accordingly

Examples of Rubrics

Here we are providing a sample set of rubrics designed by faculty at Carnegie Mellon and other institutions. Although your particular field of study or type of assessment may not be represented, viewing a rubric that is designed for a similar assessment may give you ideas for the kinds of criteria, descriptions, and performance levels you use on your own rubric.

- Example 1: Philosophy Paper This rubric was designed for student papers in a range of courses in philosophy (Carnegie Mellon).

- Example 2: Psychology Assignment Short, concept application homework assignment in cognitive psychology (Carnegie Mellon).

- Example 3: Anthropology Writing Assignments This rubric was designed for a series of short writing assignments in anthropology (Carnegie Mellon).

- Example 4: History Research Paper . This rubric was designed for essays and research papers in history (Carnegie Mellon).

- Example 1: Capstone Project in Design This rubric describes the components and standards of performance from the research phase to the final presentation for a senior capstone project in design (Carnegie Mellon).

- Example 2: Engineering Design Project This rubric describes performance standards for three aspects of a team project: research and design, communication, and team work.

Oral Presentations

- Example 1: Oral Exam This rubric describes a set of components and standards for assessing performance on an oral exam in an upper-division course in history (Carnegie Mellon).

- Example 2: Oral Communication This rubric is adapted from Huba and Freed, 2000.

- Example 3: Group Presentations This rubric describes a set of components and standards for assessing group presentations in history (Carnegie Mellon).

Class Participation/Contributions

- Example 1: Discussion Class This rubric assesses the quality of student contributions to class discussions. This is appropriate for an undergraduate-level course (Carnegie Mellon).

- Example 2: Advanced Seminar This rubric is designed for assessing discussion performance in an advanced undergraduate or graduate seminar.

See also " Examples and Tools " section of this site for more rubrics.

CONTACT US to talk with an Eberly colleague in person!

- Faculty Support

- Graduate Student Support

- Canvas @ Carnegie Mellon

- Quick Links

- Basics for GSIs

- Advancing Your Skills

Examples of Rubric Creation

Creating a rubric takes time and requires thought and experimentation. Here you can see the steps used to create two kinds of rubric: one for problems in a physics exam for a small, upper-division physics course, and another for an essay assignment in a large, lower-division sociology course.

Physics Problems

In STEM disciplines (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics), assignments tend to be analytical and problem-based. Holistic rubrics can be an efficient, consistent, and fair way to grade a problem set. An analytical rubric often gives a more clear picture of what a student should direct their future learning efforts on. Since holistic rubrics try to label overall understanding, they can lead to more regrade requests when compared to analytical rubric with more explicit criteria. When starting to grade a problem, it is important to think about the relevant conceptual ingredients in the solution. Then look at a sample of student work to get a feel for student mistakes. Decide what rubric you will use (e.g., holistic or analytic, and how many points). Apply the holistic rubric by marking comments and sorting the students’ assignments into stacks (e.g., five stacks if using a five-point scale). Finally, check the stacks for consistency and mark the scores. The following is a sample homework problem from a UC Berkeley Physics Department undergraduate course in mechanics.

Homework Problem

Learning objective.

Solve for position and speed along a projectile’s trajectory.

Desired Traits: Conceptual Elements Needed for the Solution

- Decompose motion into vertical and horizontal axes.

- Identify that the maximum height occurs when the vertical velocity is 0.

- Apply kinematics equation with g as the acceleration to solve for the time and height.

- Evaluate the numerical expression.

A note on analytic rubrics: If you decide you feel more comfortable grading with an analytic rubric, you can assign a point value to each concept. The drawback to this method is that it can sometimes unfairly penalize a student who has a good understanding of the problem but makes a lot of minor errors. Because the analytic method tends to have many more parts, the method can take quite a bit more time to apply. In the end, your analytic rubric should give results that agree with the common-sense assessment of how well the student understood the problem. This sense is well captured by the holistic method.

Holistic Rubric

A holistic rubric, closely based on a rubric by Bruce Birkett and Andrew Elby:

[a] This policy especially makes sense on exam problems, for which students are under time pressure and are more likely to make harmless algebraic mistakes. It would also be reasonable to have stricter standards for homework problems.

Analytic Rubric

The following is an analytic rubric that takes the desired traits of the solution and assigns point values to each of the components. Note that the relative point values should reflect the importance in the overall problem. For example, the steps of the problem solving should be worth more than the final numerical value of the solution. This rubric also provides clarity for where students are lacking in their current understanding of the problem.

Try to avoid penalizing multiple times for the same mistake by choosing your evaluation criteria to be related to distinct learning outcomes. In designing your rubric, you can decide how finely to evaluate each component. Having more possible point values on your rubric can give more detailed feedback on a student’s performance, though it typically takes more time for the grader to assess.

Of course, problems can, and often do, feature the use of multiple learning outcomes in tandem. When a mistake could be assigned to multiple criteria, it is advisable to check that the overall problem grade is reasonable with the student’s mastery of the problem. Not having to decide how particular mistakes should be deducted from the analytic rubric is one advantage of the holistic rubric. When designing problems, it can be very beneficial for students not to have problems with several subparts that rely on prior answers. These tend to disproportionately skew the grades of students who miss an ingredient early on. When possible, consider making independent problems for testing different learning outcomes.

Sociology Research Paper

An introductory-level, large-lecture course is a difficult setting for managing a student research assignment. With the assistance of an instructional support team that included a GSI teaching consultant and a UC Berkeley librarian [b] , sociology lecturer Mary Kelsey developed the following assignment:

This was a lengthy and complex assignment worth a substantial portion of the course grade. Since the class was very large, the instructor wanted to minimize the effort it would take her GSIs to grade the papers in a manner consistent with the assignment’s learning objectives. For these reasons Dr. Kelsey and the instructional team gave a lot of forethought to crafting a detailed grading rubric.

Desired Traits

- Use and interpretation of data

- Reflection on personal experiences

- Application of course readings and materials

- Organization, writing, and mechanics

For this assignment, the instructional team decided to grade each trait individually because there seemed to be too many independent variables to grade holistically. They could have used a five-point scale, a three-point scale, or a descriptive analytic scale. The choice depended on the complexity of the assignment and the kind of information they wanted to convey to students about their work.

Below are three of the analytic rubrics they considered for the Argument trait and a holistic rubric for all the traits together. Lastly you will find the entire analytic rubric, for all five desired traits, that was finally used for the assignment. Which would you choose, and why?

Five-Point Scale

Three-point scale, simplified three-point scale, numbers replaced with descriptive terms.

For some assignments, you may choose to use a holistic rubric, or one scale for the whole assignment. This type of rubric is particularly useful when the variables you want to assess just cannot be usefully separated. We chose not to use a holistic rubric for this assignment because we wanted to be able to grade each trait separately, but we’ve completed a holistic version here for comparative purposes.

Final Analytic Rubric

This is the rubric the instructor finally decided to use. It rates five major traits, each on a five-point scale. This allowed for fine but clear distinctions in evaluating the students’ final papers.

[b] These materials were developed during UC Berkeley’s 2005–2006 Mellon Library/Faculty Fellowship for Undergraduate Research program. Members of the instructional team who worked with Lecturer Kelsey in developing the grading rubric included Susan Haskell-Khan, a GSI Center teaching consultant and doctoral candidate in history, and Sarah McDaniel, a teaching librarian with the Doe/Moffitt Libraries.

Sample Grading Rubrics: Create Clear Homework Rubrics For Your Class

- Trent Lorcher

- Categories : Teaching methods, tips & strategies

- Tags : Teaching methods, tools & strategies

When Mr. Blockington started stabbing random teachers at the in-service, I headed to my classroom and locked the door. The pro-homework faction had begun an assault on the anti-homework faction at my school. Both sides had attempted to win me over during the

preceding month, but I was non-committal. I declared myself a homework agnostic. I assigned it, but only if it had a purpose. To establish my purpose I constructed clearly defined homework rubrics. I used different ones depending on the nature of the assignment, whether it were a summative assignment or meant for practice.

Where do you stand in the war? Ah, well regardless, having a clearly defined rubric is a must for your classroom.

Grading Rubrics

Homework fulfills different purposes depending on the assignment, the teacher, and the course. Grading rubrics will help assess assignments according to its nature, be it summative or practice. Here are potential criteria for a student’s work:

Homework must be:

- Has the proper heading.

- Neat and free of blemishes.

- Turned in on time.

- Shows all necessary work, steps, and procedures.

- Written clearly and is free of errors.

- Accurate and detailed.

- Has correct solutions.

- Identifies all aspects of a problem.

- Typed or printed neatly.

- Shows in depth understanding of the material.

- Answers give a complete response.

- Shows (a lack of) understanding.

- Does (not) show the correct solution.

- Does (not) show designated steps.

Reading Rubrics

I discovered early that students don’t always read the assignments for homework. I also discovered that some students who read didn’t really know what to look for, so I came up with a homework-reading rubric to help. The student should be able to:

- Identify important details from the reading.

- Retell the story’s main events.

- Retell the story in chronological order.

- Define important terms from the story using context clues , prior knowledge, or from a dictionary.

- Complete a story map.

This post is part of the series: Effective Teaching Methods

Work smarter not harder.

- Effective Teaching Methods

- Strategies for Reading Expository Texts

- Techniques and Ideas for Teaching Drama

- Teaching Methods on How to Lecture without Losing Control of the Class?

- Design Your Own Homework Rubric

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

Indiana University Bloomington Indiana University Bloomington IU Bloomington

- Course Development Institute

- Programmatic Assessment

- Instructional Technology

- Class Observations and Feedback

- Online Course Review and Feedback

- New Faculty Programs

- History of SoTL

- SOTL Resources

- IUB Database

- Featured SoTL Activity

- Intensive Writing

- Faculty Liaison

- Incorporating and Grading Writing

- Writing Tutorial Services

- Cel Conference

- CEL Course Development Institute

- ACE Program

- Community Partners

- CEL Course Designation

- CEL during COVID-19

- Annual AI Orientation

- Annual Classroom Climate Workshop

- GTAP Awardees

- Graduate Student Learning Communities

- Pedagogy Courses for Credit

- Diversity Statements

- Learning Communities

- Active Learning

- Frequent and Targeted Feedback

- Spaced Practice

- Transparency in Learning and Teaching

- Faculty Spotlights

- Preparing to Teach

- Decoding the Disciplines

- Backward Course Design

- Developing Learning Outcomes

- Syllabus Construction

- How to Productively Address AI-Generated Text in Your Classroom

- Accurate Attendance & Participation with Tophat

- Designing Assignments to Encourage Integrity

- DEI and Student Evals

- Engaging Students with Mental Health Issues

- Inclusive and Equitable Syllabi

- Creating Accessible Classrooms

- Proctoring and Equity

- Equitable Assignment Design

- Making Teaching Transparent

- DEIJ Institute

- Sense of Belonging

- Trauma-Informed Teaching

- Managing Difficult Classroom Discussions

- Technology to Support Equitable and Inclusive Teaching

- Teaching during a Crisis

- Teaching for Equity

- Supporting Religious Observances

- DEIJ Resources

- Test Construction

- Summative and Formative Assessment

- Classroom Assessment Techniques

- Authentic Assessment

- Alternatives to Traditional Exams and Papers

- Assessment for General Education and Programmatic Review

Rubric Creation and Use

- Google Suite

- Third Party Services: Legal, Privacy, and Instructional Concerns

- eTexts and Unizin Engage

- Next@IU Pilot Projects

- Web Conferencing

- Student Response Systems

- Mid-Semester Evaluations

- Teaching Statements & Philosophies

- Peer Review of Teaching

- Teaching Portfolios

- Administering and Interpreting Course Evaluations

- Temporary Online Teaching

- Attendance Policies and Student Engagement

- Teaching in the Face of Tragedy

- Application for an Active Learning Classroom

- Cedar Hall Classrooms

- Reflection in Service Learning

- Discussions

- Incorporating Writing

- Team-Based Learning

- First Day Strategies

- Flipping the Class

- Holding Students Accountable

- Producing Video for Courses

- Effective Classroom Management

- Games for Learning

- Quick Guides

- Mosaic Initiative

- Kelley Office of Instructional Consulting and Assessment

Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning

- Teaching Resources

- Assessing Student Learning

A rubric is a tool for evaluating and grading student work; it specifies the qualities or traits to be evaluated in an assignment and describes excellent, average, and below-average performance for each trait. Typically, a rubric is not a generic statement of expectations for student work; rather, it is tailored to describe the specific requirements for a particular assignment.

While rubrics are commonly use to evaluate student written work such as essays and research papers, they can be used for other types of assignments as well, such as oral presentations, posters, portfolios, or major projects. Rubrics can also be used in group projects as a way for team members to evaluate each other's contributions to the final product.

Most rubrics include several parts:

- Traits: the qualities or aspects of student work to be evaluated. Traits are usually expressed as nouns or noun phrases (e.g., "thesis," "graphic design elements," "accuracy of analysis," "eye contact," "grammar and mechanics").

- Performance levels: the categories of performance into which student work will be assigned for a particular trait; for example, Excellent/Good/Fair/Poor; Exceeds/Meets/Fails to Meet Expectations, etc.

- Descriptors: Brief descriptions of student work on a particular trait at a specific performance level

Why use rubrics?

For instructors as well as for students, using a rubric to grade an assignment has a number of advantages. A rubric can:

- Guarantee that instructor use the same standards for all students' work, preventing grading "drift" over time

- Specify all traits to be evaluated in student work are specified – no "hidden agendas"

- Promote equity by ensuring that all students understand the criteria by which their work will be evaluated (for more on the use of rubrics as an aspect of transparency and equity in grading, see this CITL resource on Transparency in Learning and Teaching (TILT)

- Serve as a training resource when multiple graders or AIs grade an assignment

- Make grading faster and more straightforward (although they require time to create)

- Decrease the number of student complaints about grades

- Can provide evidence on overall levels of student competence on particular traits to help instructors assess students' strengths and weaknesses, for their own information or as part of larger assessment efforts

What types of rubrics are there?

There are three general categories of rubrics: analytic, holistic, and single-point. Each has distinct advantages and disadvantages. In deciding what type of rubric to create, the main consideration should be the instructor's preference.

Analytic rubrics

An analytic rubric gives a student a separate rating or score on each trait evaluated in an assignment. An analytic rubric is typically organized in a grid, with each trait in a row and each performance level in a column. Each individual cell of the grid contains a descriptor with the characteristics of performance at that performance level on that trait.

- Time-consuming to create, but can make grading or scoring of student work easier and faster

- Gives students detailed feedback on various aspects of their work

- Can include point values for each trait and performance level to facilitate assigning numerical scores to student work

- Can be created within Canvas to simplify grading, using the the SpeedGrader tool

Holistic rubrics

Rather than evaluating each trait separately, as in an analytic rubric, a holistic rubric gives each student one overall score or grade for their work. A typical holistic rubric lists each level of performance followed by a description of student work at that level, incorporating descriptors for all the traits being evaluated. An instructor using a holistic rubric matches an entire piece of student work to the single rubric level that best describes the work.

- Easy to create, because it reflects how some instructors think

- Score or grade gives students less specific feedback on their work than an analytic rubric does

- A good option for large classes, or when only general feedback on student work is required

An essay earning an A:

- Answers the question thoroughly, in a nuanced and thoughtful way

- Uses all available sources of evidence; outside sources are clearly relevant to the topic

- Has a clear and convincing argument, that incorporates all sources of evidence effectively; addresses counterarguments

- Is well-organized, with a strong thesis statement and well-organized paragraphs with clear transitions and topic sentences

- Uses clear and polished phrasing, with only 1 or 2 grammatical errors

An essay earning a B:

- Answers the question clearly, but at a superficial level

- Uses all available sources of evidence; outside sources are relevant to the topic

- Has an argument that is mostly clear, but that may be vague in a few places; most evidence is used to support the argument well; counterarguments are not addressed

- Has a strong thesis statement and paragraphs that are mostly well-organized; one or two may lack clear transitions

- Uses clear phrasing, with one or 2 grammatical errors

An essay earning a C:

- Answers the question posed, but may ramble off-topic

- Uses all available sources of evidence; outside sources are marginally related to the topic

- Makes a fairly clear argument, but evidence is not used effectively to support it; argument may be thin in some places; counterarguments are not addressed

- Has a thesis statement that is adequate but not strong or comprehensive; paragraphs may occasionally jumble together several ideas; transitions weak or missing in some cases

- Includes a few distracting grammatical errors; some awkward phrasing

An essay earning a D:

- Does not address the question; may be reflect a misunderstanding of the topic

- Fails to use all sources of evidence; outside sources may be missing or irrelevant

- Includes an argument that may be off-topic, or may be primarily descriptive rather than argumentative; evidence is not related to the argument

- Lacks a thesis statement; paragraphs lack topic sentences; no clear transitions

- Contains numerous distracting grammatical errors; phrasing is awkward and unclear

Single-point rubrics

A single-point rubric is similar to an analytic rubric in that it breaks down performance into separate traits. But instead of providing descriptors for each performance level for each trait, a single-point rubric describes performance only at a proficient or competent level for each trait. It does not specify how performance might exceed or fall short of proficiency.

- Easy to create

- Time-consuming to use because instructor must write in a description of how a student's performance on a particular trait falls short of or exceeds proficiency

- Provides very specific, targeted feedback

- Does not require instructor to imagine all the different ways students' work could exceed or fail to meet expectations for proficiency

What are the steps in creating a rubric?

- Choose an assignment you want to create a rubric for.

- Look at examples of student work responding to the assignment, if available. Reflect on what makes the examples successful or unsuccessful, and what you hope to see in student work.

- What would a very strong response to this assignment look like? What characteristics would it have?

- What kinds of mistakes might students make on this assignment? In what ways might their work fall short?

- What kinds of feedback do you want to give students about this assignment?

- What type of rubric seems most appropriate for the type of assignment you've chosen?

- Do you want the rubric to provide a numerical score or an overall grade?

- How much detailed feedback do you need to provide for this assignment?

- For analytic or holistic rubrics, decide on the number of performance levels you will include, and label each level (with letter grades, numerical scores, or verbal labels such as Excellent, Good, Fair, Poor).

- Create a grid with traits listed in the left-hand column and performance levels across the top row. Write descriptors for each level of each trait in the cells of the grid. Avoid vague adjectives; instead, list specific things you would look for. It might be easiest to start by writing descriptors for the highest and lowest levels of performance, then filling in the intermediate levels. A simple template for an analytical rubric is provided here.

- If appropriate, make the rubric quantitative by assigning points to levels of performance, and/or different weights to specific traits.

- Write a description of student work at each performance level of the rubric. Make sure the description at each level mentions each of the traits you identified.

- It might be easiest to start by describing the highest level of performance, and then modifying the descriptors for lower levels of performance. Alternatively, you could start by describing a level of performance that is "acceptable but not exceptional," and then modifying the descriptors for higher or lower levels of performance.

- Write a descriptor for each trait at a level of performance that is acceptable but not exceptional . Depending on the levels of performance you have chosen, you might think of this level as "good," a grade of B, or a level at which students have fulfilled all the requirements of the assignment.

- Create a grid with 3 columns; in the rows of the middle column, enter a descriptor for each of the traits you created. The column on one side is for writing in feedback about how the work exceeded the acceptable level for that trait; the column on the other is for feedback about how the work fell short.

- Regardless of the type of rubric you create, before you distribute it to students, it is a good idea to apply the rubric to a few examples of student work (perhaps from a previous semester) to confirm that the rubric delivers the grade you think the student work should earn. Are all important traits included in the rubric? Do the levels describe the full range of student work? Are the gradations between levels appropriate? If not, revise the rubric and recalibrate it.

How should I use the rubric?

A rubric is not only a tool for grading student work after it has been turned in; it can also help students focus their time and effort appropriately as they work on an assignment, and it can serve as a formative tool to provide feedback on intermediate stages of student work.

- When an assignment is made: Distribute a rubric for an assignment along with the assignment itself, before students begin their work. Students can use the rubric to help them understand your expectations and organize their effort accordingly.

- Use the rubric to provide feedback to students at intermediate stages of a larger project, or formative feedback on early drafts of papers. Using the rubric in this way gives students a sense of what they still need to work on to succeed on the assignment.

- If students will be peer-reviewing each other's work, they can use the rubric as a guide when giving formative feedback. This strategy not only ensures that the peer reviews are focused on the important aspects of student work; it also helps students become familiar with the rubric.

- Use the rubric to provide feedback on student work and derive a grade.

- A rubric can serve as a sort of tally sheet to help you keep track of overall levels of student performance, to help you reflect on students' strengths and areas for further growth.

- After using a rubric, it is also helpful to reflect on the rubric itself. Did it include all the traits you wanted to evaluate? Did it accurately describe different levels of student performance? Did the grades or scores derived from the rubric seem fair?

How can I use a rubric in Canvas?

Canvas allows instructors to create analytic rubrics to grade assignments, discussions, and quizzes. Student work submitted online can be graded using the rubric in SpeedGrader. Specific traits in the rubric can also be attached to pre-defined learning outcomes (e.g., for reporting data for Gen Ed or department or school level assessment).

To learn more about rubrics in Canvas, see the Canvas Instructor Guide or IU's Technology Toolfinder .

Where can I see other examples of rubrics?

The links below provide more information about creating and using rubrics, and they include examples of rubrics from a variety of disciplines and for different kinds of assignments.

- Depaul University Teaching Commons

- Carnegie Mellon Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence & Educational Innovation

- UC Berkeley Center for Teaching and Learning

For more assistance with creating or using rubrics in your teaching, contact the CITL for an appointment .

Center for Innovative Teaching & Learning social media channels

Useful indiana university information.

- Campus Policies

- Knowledge Base

- University Information Technology Services

- Office of the Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education

- Office of the Vice Provost for Faculty and Academic Affairs

- Faculty Academy on Excellence in Teaching

- Wells Library, 2nd Floor, East Tower 1320 East Tenth Street Bloomington, IN 47405

- Phone: 812-855-9023

Assessing Learning

Grading + Rubrics

Some of the most difficult and time-consuming work that instructors and TAs do is grading student work. Whether you’re an experienced teacher, or just starting out, you will find tips on this page to improve grading efficiency, make grading more equitable, fair, and clear to your students.

Efficient Grading Equitable Grading Rubrics

Purpose of Grading

Ultimately, your assessments should be structured and graded in ways that motivate learning, rather than punish mistakes. We grade student work to provide feedback, open lines of communication, motivate improvement, and evaluate performance.

Provide Feedback - Grading gives the opportunity to provide short, targeted feedback. Limit overly critical feedback, and where possible, highlight at least one thing students did well, and one area they can improve upon.

Open Lines of Communication - The goal of assessment is to enable both parties, teacher and student, to learn where they stand relative to the learning goals. Our grading should facilitate students’ reflection on their learning, allow them to demonstrate what they understand, and discover where they are struggling.

Motivate Improvement - It’s important for our assessments to validate students’ progress, while encouraging them to learn from mistakes. Use light-touch feedback techniques , and provide opportunities for students to improve their grades. Where possible, let them redo, revise, and repeat.

Evaluate Performance - Grades are an evaluation of performance on a given task. Use specific performance criteria derived from the course learning objectives in your grading, and communicate to students what those performance criteria are before the assessment.

Make Grading Efficient

It benefits our students to receive feedback on their work in a timely manner, and we generally want to cut down the time we spend grading. You can strategize ways to make grading more efficient by using simplified metrics appropriate for the assignment, timing tools, and incorporating technologies.

UCSB Educational Technologies for Grading

Grading Assignments in GauchoSpace

Using Rubrics and Grading Criteria in GauchoSpace

Using Gradescope for Handwritten work and multiple-choice exams

iClicker for participation, polling and measuring student understanding

Simplified Grading Metrics or ‘Light Grading’

For some lower-stakes assessments, consider using simplified metrics like plus-check-minus rather than letter grades or percentages so you can grade more quickly.

Plus-Check-Minus

Minus (or 0): Didn’t do or didn’t understand

Check (or 1): Partially complete or missing something important

Plus (or 2): Complete and/or correct

Grade just some representative samples of student work. For instance, maybe only some questions are evaluated for accuracy and others on completion.

In many classroom and homework activities, grading on participation (credit/no-credit) is adequate to encourage active learning and independent studying, and can cut down on overall grading load.

Use ‘ Light-touch Feedback ’, which are brief emails to groups of students (e.g., ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘C’, and ‘D/F’ students) indicating your awareness of their performance on recent assignments, some commonly given feedback and encouragement targeted for each group of students, and direction to resources that can help them.

Student Self-Correction and Peer Review

Teaching students how to learn and work in your discipline means teaching them to set learning goals, measure their progress, and figure out where to put their efforts for continuous improvement. They also need to learn how to critique their own work and that of their peers’ in appropriate ways.

Have students assess their own work using some given criteria (see rubrics below) before they submit it so they can identify any gaps in their learning or disciplinary thinking.

Allow student self-correction or peer-correction on short writing samples, quizzes and exams by making it a classroom or homework activity.

Consider using online peer reviewing tools, like Eli Review , for students to provide peer feedback on each other’s work before students submit their work to you. It helps students turn in better work - which is always faster to grade!

For summative assessments, consider having students write a few sentences as a cover letter to their work describing what the strengths and weaknesses of their work are from their own perspective. They submit the cover letter with their work, which gives you a better idea of what to give feedback on and what the real gaps in learning might be for your class.

Timing Tools

Grading will take as much time as you give it - and more if you let it! Here are a few ideas to help you not get overwhelmed.

Set a timer to strictly hold yourself to, for example, 3-5 minutes per assignment, or 10-15 minutes per essay. Limit your feedback to comments students can use for improvement.

Create a grading schedule to space out your grading, and incorporate breaks to avoid burnout.

Make sure to track your time spent grading.

Grade with a fellow TA. Set a specific time to meet and get as much grading done as possible during that time.

Ask people who have similar kinds of assignments for advice on how to grade, what to put your effort into, and how much time might be “too much”.

Create a set of common phrases for feedback that you may find yourself giving to multiple students, and then copy/paste those onto student work, or use online grading tools in the course website to apply those phrases to student work with a few clicks.

Make Grading Equitable

Grading quickly is important, but cannot come at the expense of quality and fairness. We want our feedback to open lines of communication with students, and to be as transparent and accurate as possible, ensuring all students get a similar amount and type of feedback, with no preferential treatment. To make your grading more equitable, try implementing strategies like creating specific criteria or rubrics, TA group grading, and/or blind grading.

Grading Group Work

Specify the Criteria

Before grading assignments, consider what kinds of work your students are asked to perform on that assignment (answering questions on a quiz, responding to essay prompts, writing a paper, group work, etc.), and note which criteria you would need to see met for you to consider it to be a good performance on that work. This can increase your grading accuracy and consistency, thereby making it more equitable for your students. Then grade a few assignments using that criteria to see if you need to make adjustments. See the section on rubrics below for more details.

TA Group Grading

Grading with your fellow TAs or with a peer can help you stay consistent and discuss grading issues as they occur.

Hold a Norming Session: All readers/TAs get together and grade examples of student work together to identify potential challenges and create a common set of expectations. If possible, identify A, B, C, and F papers/projects, or responses that exceed, meet, or do not meet expectations.

Assign each grader a specific section/page of an exam to grade, instead of a certain number of exams to grade in full. This helps ensure consistency in grading across all exams and across different sections of students.

Blind Grading

Blind Grading means that you are unaware of the students’ identities (e.g., names) as you grade the work. This reduces the likelihood of grading student performance based on your subjective understanding of the students.

In Gauchospace, you can select “Blind Grading” to hide student identities (remind students to submit their assignments without identifying information in the document itself).

For blue books, go through and open all at once so you cannot see names as you move through the stack.

For essays, require students to only put their names on cover sheets which can be flipped over as you move though the stack.

Rubrics: Grading Papers, Projects, and Creative Work

Papers, projects, presentations and creative work usually involve a combination of critical thinking skills and multiple genres of work from students (such as group work, public speaking, academic writing, casual writing, graphic design, etc.). Rubrics help instructors determine and grade the specific combination of skills represented by a complex assignment by measuring each required skill independently, while also looking at students' work holistically. Rubrics also clarify and prioritize an assignment’s requirements, so students can focus their efforts appropriately and identify gaps in their learning. All of this makes your grading more equitable and efficient!

Rubrics should be customized for each assignment to ensure that instructors are measuring the learning objectives associated with the assignment. They typically contain three essential components:

A list of criteria that will be graded (i.e. thinking skills used in the assignment and format requirements. For example, ‘depth of analysis’ and ‘reference list’).

Descriptions of how students demonstrate those criteria on the assignment.

An evaluative scale that shows how many points each criterion is worth or what level of proficiency the student has attained.

What do rubrics look like?

Choose a grading framework that aligns with the complexity of the assignment and the level of detailed feedback students need about their work. All rubrics should leave space for instructor comments. Here are some example rubric frameworks:

Checklist : List of expectations that are either met or not met, with an area for overall comments.

Analytic Matrix : (see simplified example in video above as well) Includes multiple performance criteria, rating scales, and description and/or examples of indicators for each rating.

Single Point : Describes acceptable proficiency in each criteria only (no gradations of proficiency) and leaves space for comments.

Holistic : 3-5 levels of performance, along with a broad definition of the characteristics that define each level.

Most rubrics are organized into a matrix, with the thinking skills and requirements listed in the left column, descriptions of those criteria in the other columns, and a grading scale that applies a certain number of points to each criterion either in the top row or as its own column.

Many rubrics look more like a checklist, with each criterion listed with its descriptions of proficiency in paragraph form or as bullet points. The scale can be in the descriptions or somewhere else on the document - as long as the students can see the relative weights or acceptable performance levels for the criteria so they know where to focus their energies.

For creative projects it is important you provide enough structure to allow you to evaluate work fairly, while encouraging students to express themselves. Also make all minimum requirements very clear, like sources/references, page/word limits, or time limits for presentations, and formatting.

How can I use a rubric as a grading tool?

Try to create the rubric as you write or modify the assignment instructions. Then give it to the students with the instructions. Tell them to use it as a reference for where to focus their efforts. Consider allowing the students to fill out the rubric themselves as a cover letter to their assignment submission. Return the rubric to the student with their graded work so they can see the rationale behind the grade they received.

If you have a digital rubric on the course website or another grading tool, then you will fill out the rubric options when you create the assignment submission. As you grade each submission you will see options for assigning points and leaving comments.

If you have a paper document that you are using as a rubric, print out a rubric for each student, and then use a pencil to check off the matrix cells that best describe the student’s performance and write comments. A pencil allows you to make adjustments as you grade the class.

If you have a digital document as a rubric, copy/paste it onto their work or on the grading screen, or attach it to their submission in the grading area. Alternatively, have the students add the rubric (unfilled) to their work, or as an attachment to it. You can use the digital grading tools to fill it out.

When should I share my rubric with the class?

We recommend giving your students the rubric at the same time you give them the assignment instructions. This can reduce the number of questions and future complaints about unfair grading. You can also reference the rubric while teaching related skills and content.

If students are writing an essay during a midterm or final exam time, distribute the rubric several weeks in advance of the due date, so they can use it to focus their studying and preparation

Instructional Consultation 1130 Kerr Hall [email protected] 805-893-2972

TA Development Program 1130 Kerr Hall [email protected] 805-893-2972

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

fa51e2b1dc8cca8f7467da564e77b5ea

- Make a Gift

- Join Our Email List

Whenever we give feedback, it inevitably reflects our priorities and expectations about the assignment. In other words, we're using a rubric to choose which elements (e.g., right/wrong answer, work shown, thesis analysis, style, etc.) receive more or less feedback and what counts as a "good thesis" or a "less good thesis." When we evaluate student work, that is, we always have a rubric. The question is how consciously we’re applying it, whether we’re transparent with students about what it is, whether it’s aligned with what students are learning in our course, and whether we’re applying it consistently. The more we’re doing all of the following, the more consistent and equitable our feedback and grading will be:

Being conscious of your rubric ideally means having one written out, with explicit criteria and concrete features that describe more/less successful versions of each criterion. If you don't have a rubric written out, you can use this assignment prompt decoder for TFs & TAs to determine which elements and criteria should be the focus of your rubric.

Being transparent with students about your rubric means sharing it with them ahead of time and making sure they understand it. This assignment prompt decoder for students is designed to facilitate this discussion between students and instructors.

Aligning your rubric with your course means articulating the relationship between “this” assignment and the ones that scaffold up and build from it, which ideally involves giving students the chance to practice different elements of the assignment and get formative feedback before they’re asked to submit material that will be graded. For more ideas and advice on how this looks, see the " Formative Assignments " page at Gen Ed Writes.

Applying your rubric consistently means using a stable vocabulary when making your comments and keeping your feedback focused on the criteria in your rubric.

How to Build a Rubric

Rubrics and assignment prompts are two sides of a coin. If you’ve already created a prompt, you should have all of the information you need to make a rubric. Of course, it doesn’t always work out that way, and that itself turns out to be an advantage of making rubrics: it’s a great way to test whether your prompt is in fact communicating to students everything they need to know about the assignment they’ll be doing.

So what do students need to know? In general, assignment prompts boil down to a small number of common elements :

- Evidence and Analysis

- Style and Conventions

- Specific Guidelines

- Advice on Process

If an assignment prompt is clearly addressing each of these elements, then students know what they’re doing, why they’re doing it, and when/how/for whom they’re doing it. From the standpoint of a rubric, we can see how these elements correspond to the criteria for feedback:

All of these criteria can be weighed and given feedback, and they’re all things that students can be taught and given opportunities to practice. That makes them good criteria for a rubric, and that in turn is why they belong in every assignment prompt.

Which leaves “purpose” and “advice on process.” These elements are, in a sense, the heart and engine of any assignment, but their role in a rubric will differ from assignment to assignment. Here are a couple of ways to think about each.

On the one hand, “purpose” is the rationale for how the other elements are working in an assignment, and so feedback on them adds up to feedback on the skills students are learning vis-a-vis the overall purpose. In that sense, separately grading whether students have achieved an assignment’s “purpose” can be tricky.

On the other hand, metacognitive components such as journals or cover letters or artist statements are a great way for students to tie work on their assignment to the broader (often future-oriented) reasons why they’ve been doing the assignment. Making this kind of component a small part of the overall grade, e.g., 5% and/or part of “specific guidelines,” can allow it to be a nudge toward a meaningful self-reflection for students on what they’ve been learning and how it might build toward other assignments or experiences.

Advice on process

As with “purpose,” “advice on process” often amounts to helping students break down an assignment into the elements they’ll get feedback on. In that sense, feedback on those steps is often more informal or aimed at giving students practice with skills or components that will be parts of the bigger assignment.

For those reasons, though, the kind of feedback we give students on smaller steps has its own (even if ungraded) rubric. For example, if a prompt asks students to propose a research question as part of the bigger project, they might get feedback on whether it can be answered by evidence, or whether it has a feasible scope, or who the audience for its findings might be. All of those criteria, in turn, could—and ideally would—later be part of the rubric for the graded project itself. Or perhaps students are submitting earlier, smaller components of an assignment for separate grades; or are expected to submit separate components all together at the end as a portfolio, perhaps together with a cover letter or artist statement .

Using Rubrics Effectively

In the same way that rubrics can facilitate the design phase of assignment, they can also facilitate the teaching and feedback phases, including of course grading. Here are a few ways this can work in a course:

Discuss the rubric ahead of time with your teaching team. Getting on the same page about what students will be doing and how different parts of the assignment fit together is, in effect, laying out what needs to happen in class and in section, both in terms of what students need to learn and practice, and how the coming days or weeks should be sequenced.

Share the rubric with your students ahead of time. For the same reason it's ideal for course heads to discuss rubrics with their teaching team, it’s ideal for the teaching team to discuss the rubric with students. Not only does the rubric lay out the different skills students will learn during an assignment and which skills are more or less important for that assignment, it means that the formative feedback they get along the way is more legible as getting practice on elements of the “bigger assignment.” To be sure, this can’t always happen. Rubrics aren’t always up and running at the beginning of an assignment, and sometimes they emerge more inductively during the feedback and grading process, as instructors take stock of what students have actually submitted. In both cases, later is better than never—there’s no need to make the perfect the enemy of the good. Circulating a rubric at the time you return student work can still be a valuable tool to help students see the relationship between the learning objectives and goals of the assignment and the feedback and grade they’ve received.

Discuss the rubric with your teaching team during the grading process. If your assignment has a rubric, it’s important to make sure that everyone who will be grading is able to use the rubric consistently. Most rubrics aren’t exhaustive—see the note above on rubrics that are “too specific”—and a great way to see how different graders are handling “real-life” scenarios for an assignment is to have the entire team grade a few samples (including examples that seem more representative of an “A” or a “B”) and compare everyone’s approaches. We suggest scheduling a grade-norming session for your teaching staff.

- Designing Your Course

- In the Classroom

- When/Why/How: Some General Principles of Responding to Student Work

- Consistency and Equity in Grading

- Assessing Class Participation

- Assessing Non-Traditional Assignments

- Beyond “the Grade”: Alternative Approaches to Assessment

- Getting Feedback

- Equitable & Inclusive Teaching

- Advising and Mentoring

- Teaching and Your Career

- Teaching Remotely

- Tools and Platforms

- The Science of Learning

- Bok Publications

- Other Resources Around Campus

Academic Resources

- Academic Calendar

- Academic Catalog

- Academic Success

- BlueM@il (Email)

- Campus Connect

- DePaul Central

- Desire2Learn (D2L)

Campus Resources

- Campus Security

- Campus Maps

University Resources

- Technology Help Desk

Information For

- Alumni & Friends

- Current Students

- Faculty & Staff

Feedback & Grading

- Exit Tickets and Midterm Surveys

- Direct vs. Indirect Assessment

- Assessment and Bias

- Low-Stakes Assignments

- High-Stakes Assignments

- Types of Rubrics

- Creating Rubrics

Evaluating Rubrics

- More Examples

- Assessing Reflection

- Responding to Plagiarism

- Submitting Grades

- Teaching at DePaul

- Support Services

- Teaching Guides

- Technology Tools

Teaching Commons > Teaching Guides > Feedback & Grading > Rubrics > Evaluating Rubrics

Regardless of whether you are modifying an existing rubric, creating one from scratch, or using a rubric developed by another party, both before and after you use the rubric is a good time to evaluate it and determine if it is the most appropriate tool for the assessment task.

Questions to ask when evaluating a rubric include:

Does the rubric relate to the outcome(s) being measured? The rubric should address the criteria of the outcome(s) to be measured and no unrelated aspects.

Does it cover important criteria for student performance? Is the rubric authentic, does it reflect what was emphasized for the learning outcome and assignment(s)?

Does the top end of the rubric reflect excellence? Is acceptable work clearly defined? Does the high point on the scale truly represent an excellent ability? Does the scale clearly indicate an acceptable level of work? These should be based not on the number of students expected to reach these levels, but on current standards defined by the department often taking into consideration the types of courses student work was collected from (introductory or capstone courses).

Are the criteria and scales well-defined? Is it clear what the scale for each criterion measures and how the levels differ from one another? Has it been tested with actual student products to ensure that all likely criteria are included? Is the basis for assigning scores at each scale point clear? Is it clear exactly what needs to be present in a student product to obtain a score at each point on the scale? Is it possible to easily differentiate between scale points?

Can the rubric be applied consistently by different scorers? Inter-rater reliability, also sometimes called inter-rater agreement, is a reference to the degree to which scorers can agree on the level of achievement for any given aspect of a piece of student work. Inter-rater reliability depends on how well the criteria and scale points are defined. Working together in a norming session to develop shared understandings of definitions and adjusting the criteria, scales, and descriptors will increase consistency.

Rubrics: Useful Assessment Tool

Rubrics can be excellent tools to use when assessing students’ work for several reasons. You might consider developing and using rubrics if:

- You find yourself re-writing the same comments on several different students’ assignments.

- Your marking load is high, and writing out comments takes up a lot of your time.

- Students repeatedly question you about the assignment requirements, even after you’ve handed back the marked assignment.

- You want to address the specific components of your marking scheme for student and instructor use both prior to and following the assignment submission.

- You find yourself wondering if you are grading or commenting equitably at the beginning, middle, and end of a grading session.

- You have a team of graders and wish to ensure validity and inter-rater reliability.

What is a rubric?

A rubric is an assessment tool that clearly indicates achievement criteria across all the components of any kind of student work, from written to oral to visual. It can be used for marking assignments, class participation, or overall grades. There are two types of rubrics: holistic and analytical.

Holistic rubrics

Holistic rubrics group several different assessment criteria and classify them together under grade headings or achievement levels.

For a sample participation rubric, see the Appendix of this teaching tip. Our CTE Teaching Tip: Responding to Writing Assignments includes holistic rubrics specifically designed for writing assignments.

Analytic rubrics

Analytic rubrics separate different assessment criteria and address them comprehensively. In a horizontal assessment rubric, the top axis includes values that can be expressed either numerically or by letter grade, or a scale from Exceptional to Poor (or Professional to Amateur, and so on). The side axis includes the assessment criteria for each component. Analytic rubrics can also permit different weightings for different components.

See the VALUE Rubrics developed by the American Association of Colleges and Universities. They have open-access rubrics for 16 cross-cutting learning outcomes including creative thinking, teamwork, and written communication.

How to make a rubric