An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Cambridge Open

IS THE LINK BETWEEN HEALTH AND WEALTH CONSIDERED IN DECISION MAKING? RESULTS FROM A QUALITATIVE STUDY

Martina garau.

Office of Health Economics, Email: gro.eho@uaragm

Koonal Kirit Shah

Office of Health Economics

Priya Sharma

United States Agency for International Development

Adrian Towse

Associated data.

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0266462315000616.

Objectives: The aim of this study was to explore whether wealth effects of health interventions, including productivity gains and savings in other sectors, are considered in resource allocations by health technology assessment (HTA) agencies and government departments. To analyze reasons for including, or not including, wealth effects.

Methods: Semi-structured interviews with decision makers and academic experts in eight countries (Australia, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, South Korea, Sweden, and the United Kingdom).

Results: There is evidence suggesting that health interventions can produce economic gains for patients and national economies. However, we found that the link between health and wealth does not influence decision making in any country with the exception of Sweden. This is due to a combination of factors, including system fragmentation, methodological issues, and the economic recession forcing national governments to focus on short-term measures.

Conclusions: In countries with established HTA processes and methods allowing, in principle, the inclusion of wider effects in exceptional cases or secondary analyses, it might be possible to overcome the methodological and practical barriers and see a more systematic consideration of wealth effect in decision making. This would be consistent with principles of efficient priority setting. Barriers for the consideration of wealth effects in government decision making are more fundamental, due to an enduring separation of budgets within the public sector and current financial pressures. However, governments should consider all relevant effects from public investments, including healthcare, even when benefits can only be captured in the medium- and long-term. This will ensure that resources are allocated where they bring the best returns.

AIM OF THE STUDY

Traditionally, the primary outcome of health interventions considered by decision makers is the impact on patients’ health in terms of reduced morbidity or mortality. Additionally, interventions can generate “wealth effects” (also referred to as indirect costs, nonhealth benefits, or wider societal effects) which extend beyond the health gains accruing to patients. Wealth effects include: improvements in the labor productivity of patients and of their caregivers; cost savings to healthcare, social care, and other sectors; and increases in national income.

In 2003, David Byrne, the then European Commissioner for Health and Consumer Protection, delivered a speech that focused on the importance of health as a “driver of economic prosperity” for European Union (EU) Member States ( 1 ). There is a growing body of research aimed at demonstrating the interdependencies between health and wealth ( 2 – 4 ). However, we are not aware of any published studies of whether the consideration of wealth effects, as defined above, has had an impact on resource allocation decisions in practice. This study examines the extent to which the link between health and wealth has influenced national decision making in a sample of eight countries.

We focused on three types of decision makers: health technology assessment (HTA) agencies which make recommendations about the use and/or public reimbursement of health interventions; Health Ministries that run national health systems and in some cases allocate resources across separate health system components; and Finance Ministries/Treasuries that control the budgets of government departments.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

We began by developing a categorization of potential wealth effects based on the published literature. We identified relevant articles by following up the references in recent reviews and comprehensive analyses of the impact of health on economic growth in high-income countries, labor productivity and other indirect costs in economic evaluations ( 5 – 9 ). We identified further publications by conducting searches of Google Scholar using the keywords and abstract terms from these studies.

Figure 1 presents our conceptual framework. It illustrates that in addition to health effects such as reducing morbidity or mortality ( Figure 1 , box A), health interventions can also produce a variety of wealth effects.

Conceptual framework of the link between health and economic outcomes.

The economic costs of illness often fall on sectors other than the healthcare sector; the use of health interventions can lead to important cost savings to those sectors ( Figure 1 , box B). The resources freed up could then be used to provide additional services within the sector. For example, it has been shown that one of the key drivers of the cost of Alzheimer's disease (almost 40 percent) is the cost of social care provided in patients’ homes or in other community settings ( 10 ).

Despite evidence showing that indirect costs can constitute a significant proportion of the total cost of illness to society, the inclusion of those costs in economic evaluations remains limited. Stone et al. ( 11 ) found that productivity costs were considered in less than 10 percent of published cost-utility analyses.

Figure 1 also shows that at the macroeconomic level, a positive link may exist between the health of a population and the level of national income ( Figure 1 , box C). At the microeconomic level, healthcare interventions can have an impact on individuals or households by improving patients’ productivity at work (if they are of working age) and by reducing patients’ and carers’ absences from work due to ill health ( Figure 1 , box D). The arrow linking macro and micro effects indicates that some micro effects are captured at the macro level, for example, reducing sickness absence can improve individual firms’ production which can also contribute to national income growth. Some effects, however, such as time spent doing unpaid work (e.g., housework), tend only to be captured at the micro level.

Empirical evidence using a global sample of countries has shown that health, measured in terms of life expectancy, is a robust predictor of economic growth ( 12 – 15 ). However, the role of health seems to be stronger in the context of low- and medium-income countries compared with high-income countries, where evidence is limited and shows mixed results. For example, Knowles and Owen ( 16 ) found that life expectancy had a minor impact on the economic growth of a sample of high-income countries, while Bhargava et al. ( 17 ) found that above a certain level of income per capita in high-income countries, improvements in adult survival rates had a negative impact on growth rates.

The results of these types of studies should be interpreted with caution for two reasons. The first relates to the indicators used to measure population health, which in most studies is life expectancy or adult mortality. While there is wide variation in life expectancy between middle- and low-income countries, there is little variation among high-income countries. As a result, more relevant indicators of health are needed to capture the different levels of health in different high-income countries ( 4 ). An example of this is cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality as used in a study by Suhrcke and Urban ( 18 ). They show that a 10 percent increase in CVD mortality among OECD countries reduces the per capita income growth rate by one percentage point. CVD mortality was used as a proxy for health for two reasons. The first was the large disease burden of noncommunicable diseases in OECD countries, CVD in particular. The second was the impact on labor productivity, as CVD affects individuals of working age.

The second reason relates to institutional factors that prevent countries from realizing the positive effects of health improvements. As life expectancy exceeds the retirement age by a growing margin, the old age dependency ratio increases, thus negatively impacting government fiscal stability and, indirectly, economic growth. One way to overcome this would be to increase the retirement age so that the improved health of older people can result in an increase of labor supply and productivity ( 19 ). Those policies have already been implemented or are under discussion in several countries.

The literature also explores the issue of casual effect between health and wealth and shows that higher income can increase consumption and provision of goods and services promoting health ( 6 ; 13 ). This effect will ultimately reinforce the importance of recognizing the role of improving health outcomes on national income, which can create a “virtual” cycle between health and wealth.

At the micro-economic level, ill health can affect individuals’ participation in the labor force in the short-term, long-term or permanently. This affects individuals’ ability to earn income for themselves and their family, to consume market goods and to engage in leisure activities. A body of literature estimates what are called “indirect costs” to society due to ill health. They include losses due to: (i) Reduced productivity at work (presenteeism): some illnesses, such as back pain and depression ( 9 ; 20 ), do not necessarily prevent individuals from attending work but may affect their on-the-job performance; (ii) Sickness absence (absenteeism): individuals who are suffering, recovering from illness, or who are undergoing treatment may require absence from work. For example, it is estimated that a major component of the cost of breast cancer is due to patients’ absence from work due to treatment-related symptoms ( 21 ); (iii) Non-employment / early retirement: illnesses that are particularly debilitating may result in individuals being unable to return to work (and, therefore, unable to produce output) on a permanent basis. For example, Kobelt ( 22 ) reported that 38 percent of the total cost of multiple sclerosis is due to lost productivity from early retirement.

The effects of ill health also apply to those providing informal (i.e., unpaid) care to patients ( 23 ). For example, when children attend hospital appointments, their parents often need to be absent from work to take them to their appointments.

We conducted semi-structured interviews with decision makers and academic experts in eight countries. The aim of the interviews was to explore whether the wealth effects of interventions identified in our conceptual framework represented in Figure 1 are considered by HTA agencies in their health technology evaluations, and by government departments in their budget setting decisions. We also asked about the reasons why these wealth effects were or were not considered. Wealth effects were defined as nonhealth, economic effects generated by the use of health interventions, including impacts on labor productivity and supply, and savings to other sectors.

The potential interviewees invited to participate included individuals representing one or more of the three categories of decision makers (HTA agencies, Health Ministries, Finance Ministries). All were either currently employed by the relevant body or ministry, or local academic experts directly involved in their country's HTA processes and/or in advising their country's Ministry of Health.

The initial geographical scope included countries with established or emerging HTA systems, and near universal health coverage: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, South Korea, Sweden, Turkey, and the United Kingdom (UK). The final list of countries was based on whether invitees responded to our request for an interview. These were: Australia, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, South Korea, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

We developed two questionnaires, one to be used for the HTA or reimbursement decision makers and HTA experts (“Questionnaire for HTA decision makers/experts”; Supplementary Table 1 ); and the other to be used for the employees of Health and Finance Ministries who had little or no technical knowledge of HTA (“Questionnaire for Ministry of Health/Finance/experts”). The questionnaire for HTA decision makers/experts aimed at exploring whether effects on individuals/households (box D of Figure 1 ) generated by health interventions matter in the HTA processes of the interviewee's country; and if they are, which types of effects tend to be considered, in which diseases areas they are particularly important, what type of evidence is required to show their impact and what are the key issues encountered. Hypothetical interventions for three conditions were presented to illustrate those effects: Alzheimer's disease, breast cancer, and depression. The case studies were developed using data from recently published cost of illness studies ( 10 ; 21 ; 24 ). They focused on drug therapies, because many of the interviewees (particularly the HTA experts) were more familiar with the evaluation of drugs than of other types of health intervention, but it was emphasized to all interviewees that we were interested in the effects of all health interventions. In addition, the final question asked interviewees about the impact of new health interventions on national income (box C in Figure 1 ) and whether it mattered in the decision-making process they had experience of.

Categorization of Countries According to the Extent of Consideration of Wealth Effects in Resource Allocation Decisions

The questionnaire for Ministry of Health/Finance/experts asked interviewees about how any effects of health interventions on nonhealth public sectors (box B of Figure 1 ) influence budget setting decisions, for example, whether resource transfers are possible when benefits from health spending are captured in other sectors. For the sake of simplicity, this questionnaire included only one case study (the hypothetical intervention for Alzheimer's disease).

Both questionnaires included open-ended questions. This enabled the interviewer to structure the interview by asking predefined questions, but also to pursue additional topics in more depth or to probe for information on themes emerging from the interviewers’ answers. The questionnaires were sent to the interviewees in advance of the hour-long telephone interview. Two researchers were present at all interviews. Summary notes of the interviews were sent to the interviewees for confirmation and correction (if necessary) to ensure that all points made in the discussion were appropriately captured.

The finalized notes from the full set of interviews were reviewed by three researchers (M.G., K.S., and P.S.) who, working independently, summarized the answers in a tabular form, proposed categorizations of countries based on their consideration of wealth effects, and grouped common barriers to the inclusion of wealth effects. In particular, based on answers to two key questions (Are wealth effects mentioned in HTA guidelines/methods guide? Are they considered by your HTA body in practice?), we developed a categorization of countries designed to summarize the impact of wealth effects on their decision-making processes. This categorization is presented in the next section.

Results from those analyses were then discussed and validated, and key themes were agreed, in a group discussion involving all four researchers.

INTERVIEW RESULTS

We interviewed thirteen individuals from eight countries: seven academic experts and six individuals working (either currently or formerly) for HTA agencies or the Ministries of Health; two individuals from each country were interviewed, with the exception of France, Italy, and South Korea. When the experts stated they had a direct experience or extensive knowledge of the processes of the HTA agencies and/or the Ministries of Health in their countries, we asked them questions related to those topics (suggesting that the HTA/Health Ministry perspectives were represented).

In two countries (Italy, Poland), a Ministry of Finance perspective was represented as the interviewees were able to answer the questions about the allocation of resources among different ministries. In all countries, the Health Ministry and HTA perspectives were represented.

Do Decision Makers Consider Wealth Effects?

Based on our analysis of the interviewees’ responses (following the approach described in the methods section), we assigned each country to one of four categories: countries that consider wealth effects regularly; countries that consider wealth effects in principle but rarely or never in practice; countries that do not consider wealth effects within HTA; and countries that apparently do not currently consider any economic or cost data when making reimbursement and healthcare budget-setting decisions.

As shown in Table 1 , with the exception of Sweden, no country considers wealth effects on a regular basis. In Australia, Poland, and the United Kingdom, although economic evaluations of individual drug interventions submitted to HTA agencies could include wealth effects as part of a secondary analysis, in practice this rarely happens. In Germany, Italy, and Poland there is no scope for including anything other than the direct costs to the healthcare sector and benefits of a new drug. In France, the HTA agency did not consider economic or cost data at the time of our analysis.

At the Finance Ministry level, our two interviewees (from Poland and Italy) emphasized that there is reluctance to consider wider effects of health interventions in their decisions about allocating resources across sectors. Two other interviewees (from the United Kingdom and Australia) referred to national policy reports emphasizing the importance of wealth effects ( 25 ; 26 ) but noted that these have not resulted in any specific policy changes to date.

Key Barriers for the Inclusion of Wealth Effects

Our interviews revealed several legislative, evidence, and policy barriers to incorporating wealth effects into decision making. We have grouped those into the following themes: (i) System fragmentation, including a persistent culture of silo budgets whereby interlinks between governmental departments’ expenditures are not considered regularly if at all and views that the healthcare system should concentrate on health; (ii) Methodological and data generation issues, such as difficulties in demonstrating with reliable data the impact of a specific treatment on productivity; (iii) Practical issues due to added complexity if those effects are included in decision making; (iv) Equity issues as the inclusion of productivity effects can favor interventions for working-age individuals; (v) Weakness of evidence on the relationship between health and economic growth at the macro level which is limited in relation to high-income countries.

System Fragmentation

The general view among decision makers is that the primary and often sole objective of health care is to improve citizens’ health. Thus healthcare budgets tend to be separate from budgets for other sectors even when they are closely related, such as social care. Any spill-overs that occur across sectors are not captured, for example, where spending on a healthcare intervention leads to lower social care costs that are paid out of a separate budget.

In Australia, Italy, and Poland we found that there are also silo budgets within the heathcare sector. In Australia for example, hospital and primary care are financed separately with no scope for transferring any cost savings between the different parts of the healthcare system.

In South Korea, the Government created a separate budget to cover the cost of care for dementia. However, this budget covers community care but not drug costs, which are funded by means of the health budget. Any savings that may result from a new dementia drug that delays the need for community care would, therefore, not be considered in a drug benefit assessment as they would accrue outside the healthcare sector.

In Sweden, even though the HTA body adopts a societal perspective when making reimbursement recommendations on new medicines (i.e., all relevant costs and benefits associated with a treatment and illness are considered), individual County Councils can restrict use of HTA-approved medicines to meet their own budget targets (the key criterion for their decisions is budget impact) ( 8 ).

A few examples of integrated decision making, where nonhealth programs recognize health benefits, were identified (for example, local authority-funded cycle lanes in the United Kingdom). However, our interviewees could not identify any cases where nonhealth benefits of medicine-based interventions were taken into account when allocating resources to the healthcare sector or more specifically to the budget for pharmaceuticals.

Methodological and Data Generation Issues

When incorporating wealth effects in economic evaluation, there are methodological issues around measuring, and providing evidence of, productivity effects. First, there is no methodology to disaggregate productivity gains and improvements in quality of life measured by the quality-adjusted life-years (QALY). Are changes in the individuals’ ability to earn income reflected in the QALY? If they are, there is a potential for double counting those effects.

Second, even when productivity effects are included in the cost-effectiveness estimation of drug interventions (as indirect costs), HTA bodies require evidence showing productivity effects which are directly attributable to the intervention, which is rarely available. For example, what is the proportion of patients that return to work due to the treatment?

In addition, it was noted that short-term absences from work do not necessarily lead to significant losses for the firm employing the patient as the returning employee might catch up on her/his work and be more productive.

Those concerns were highlighted by interviewees from Australia and the United Kingdom, where the HTA process rely on cost-effectiveness evidence. In Sweden, where wealth effects are considered on a regular basis, an interviewee raised concerns about the poor quality of the studies showing productivity benefits underpinning recent submissions to the HTA body. The reason identified was that other HTA bodies such as NICE do not ask for this evidence, hence it is not a priority for companies to collect it. Overall, it emerged that, if HTA bodies were to consider productivity effects and other wealth effects of health interventions, including savings falling to other public sectors, then robust data showing those effects would be demanded.

The interviewees from Poland and South Korea discussed the issue of transferability of the data on indirect effects across countries, as evidence collected in the United Kingdom or Sweden, for example, may not be applicable to them. Therefore, the lack of country-specific data was identified as a barrier to the incorporation of indirect costs in their HTA decisions.

Practical Issues

Some interviewees were skeptical of the impact that wealth effects, particularly productivity gains, can have on final decisions. As one interviewee stated, indirect costs are unlikely to be “the factor that tips the scale in favor of a treatment or not.”

Furthermore, adopting a wider perspective in economic evaluations would result in more work for HTA agencies and for the manufacturers collecting the evidence. Many of our interviewees questioned whether the inclusion of these wealth effects was worth the additional cost and effort.

In some countries, there are legislative barriers to taking wealth effects into consideration when evaluating health interventions. For example, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom has until recently been required to adopt a narrow, healthcare sector perspective as specified in the legislation that defined its remit. The new legislation. Public health is already an exception, partly because many of the actions recommended in public health guidance relate to actors outside the health sector. This is reflected in NICE's public health activities where the Institute is more open to reflecting costs and benefits to other sectors. Similarly, in Poland the objective of the healthcare system is defined by law to be to improve the health of the Polish population with no mention of other nonhealth gains. Finally, German decision makers are guided by the statutory Social Code Book regulations, according to which drug benefit assessments should be based on patient relevant benefits identified using clinical endpoints.

Equity Issues

Including indirect effects in the assessment of health interventions can have distributive effects between different social groups. For example, including productivity effects will favor treatments aimed at working age individuals over those who are unable to work because of permanent disabilities, older/retired individuals (who tend to consume more resources than they produce, although they may have been net producers in the past), and children (who may eventually become net producers, but effects accruing over a life time are difficult to estimate). Importantly, this could result in situations where treatments which extend the lives of the older patients for a certain period of time will be found to be less cost-effective than treatments that extend the lives of working age patients for the same amount of time.

Interviewees from Australia and the United Kingdom had particularly strong concerns around the fact that including productivity effects of health interventions conflicted with the principles of equity and nondiscrimination that their health systems were founded upon. Some of the disadvantaged groups are already among the worst-off in society, so any reprioritization of resources away from them could be deemed to be inequitable.

This is in contrast with the approach in Sweden, which is the only country considering wealth effects on a regular basis, despite the fact that it is not an insurance-based system where, arguably, interventions increasing people's ability to work would be favored by employers contributing to insurance funds.

Weakness of Evidence on Health Impact on Economic Growth

We asked all interviewees whether the Suhrcke and Urban ( 18 ) study, which provides evidence on the impact of improved health outcomes in CVD on macroeconomic growth, had had any resonance in their country. Almost all interviewees said that the study, which was commissioned by the European Commission ( 4 ), has not had any impact on their national policy.

There are reservations about applying the Suhrcke and Urban results to inform resource allocation decisions. One issue identified was that the focus of the study is on one disease area, although one with the largest burden in high-income countries. Therefore, the results do not necessarily support investment in healthcare generally as a means to promote economic growth. In addition, the results cannot be used to inform priority setting within the health sector as evidence on the impact of other disease areas on macroeconomic indicators is not available.

A few interviewees questioned the validity of these studies, especially in light of documented methodological limitations ( 7 ). Only in the United Kingdom, according to one of the interviewees, was the Suhrcke and Urban ( 18 ) study discussed by a decision-making committee; however, this was primarily for public health interventions.

The barriers to the incorporation of wealth effects in decision making identified by our interviewees could be addressed in several ways. Breaking down silo budgeting may be difficult, as this will require not only a change in the operation of government financial systems to allow for resource transfers across departments, but also potentially the need to develop more integrated healthcare systems focusing on outcomes that go beyond health gains.

On the other hand, methodological issues can be addressed in the short term by undertaking research comparing the available approaches (e.g., friction cost approach, human capital approach) to estimating productivity gains and assess their validity in different economic contexts. In addition, empirical studies can be conducted to test the extent to which effects of changes in individuals’ income are captured by the QALY such as the study by Tilling et al. ( 27 ). This will give HTA bodies more confidence in considering wealth effects systematically.

A clear signal from HTA bodies to a more open approach to the consideration of wealth effects will encourage bio-pharmaceutical companies to invest in generating the evidence needed to demonstrate the presence and the size of those effects for specific treatments. In particular, for each category of wealth effect, including productivity, there is a need to identify the type of studies that can be undertaken and approach to incorporate this evidence in HTA submissions. If HTA remains ambivalent regarding the importance of wealth effects, companies are unlikely to generate good quality evidence to prove them. The UK Department of Health and NICE recently proposed introducing a new, value-based pricing system for pharmaceuticals ( 28 ), based on the recognition that the value of a medicine should capture all benefits to society beyond health. Though the proposal was ultimately rejected, it demonstrates that UK decision makers have at least considered the feasibility of incorporating a broader range of non-health effects in assessment processes.

Equity concerns should be considered in light of certain indirect effects of interventions. Taking into account productivity benefits could result in favoring treatments for diseases affecting individuals of working age. However, all members of society could potentially benefit from keeping people at work if the increased tax revenues are redistributed across different groups (e.g., by means of investment in public services). Furthermore, the improved health of nonworking individuals can also have positive effects on the economy by allowing their (informal) carers to remain in work and maintain their labor supply. This may be particularly true for quality of life-improving treatments for nonworking patients with chronic conditions, whose need for caregiving falls as a result of treatment.

The issue of uncertain results on the link between health and economic growth in high-income countries does not justify moving resources away from the health sector. From a methodological perspective, more research can be done entailing, for example, the use of health indicators other than life expectancy to better reflect variation of health states in rich countries and also the application of the Suhrcke and Urban ( 18 ) approach to different disease areas. From a national governments perspective, there is an opportunity to expand taxable income when funding interventions that increase patients’ ability to work and earn income, and, therefore, to set a virtuous cycle of “better health—more income for citizens—more taxable income for governments,” which could increase the total resources available and partly help dealing with public deficits.

STUDY LIMITATIONS AND SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

Our qualitative analysis was based on a relatively small number of interviews (one or two in each country) conducted by telephone. This was sufficient for us to identify common issues preventing countries from considering all relevant effects of healthcare spending, including positive economic spill-overs. A larger sample, however, would have allowed us to compare a greater number of views and to validate some of the claims being made. Further analyses could include more countries with emerging HTA systems and growing economies (such as Brazil) and new EU Member States facing budgetary pressures, to investigate whether and how health could be considered a long-term investment. In terms of methodology, qualitative approaches other than interviews could be used, such as focus groups or workshops allowing participants to interact with one another and to make recommendations following a period of discussion and deliberation.

CONCLUSIONS

There is evidence suggesting that, in certain diseases areas, health interventions can produce economic gains for patients and national economies ( 9 ; 18 ; 22 ; 23 ). Those benefits include improvements in the productivity of patients and their carers at work, and cost savings to other sectors such as education and social care.

Despite this evidence, the results from our interviews with decision makers and expert commentators in eight countries suggest that, with the exception of Sweden, considerations of the link between health and wealth have little to no impact on decision making, from budget setting across ministries to reimbursement decisions on individual therapies.

In countries with established HTA processes and methods guides that in principle allow the inclusion of wider effects in exceptional cases or secondary analyses (Australia, Poland, and the United Kingdom in our study), it might be possible to overcome some of the methodological and practical barriers identified and move toward a more systematic consideration of wealth effects in drug decision making. The United Kingdom, for example, considered this option when developing a proposal for value-based assessment ( 28 ). Ultimately, considering all relevant elements, including both health and wealth effects, is consistent with principles of efficient priority setting and does not necessarily require increasing the healthcare budget.

As far as national government decisions are concerned, barriers to the consideration of wealth effects in decision making and investment assessments are more fundamental due to an enduring separation of budgets within the public sector (and in some cases within the health sector) which prevents the capture of spill-overs across areas. In addition, given current financial pressures, it seems unlikely that governments will be willing to shift their focus away from cost-cutting measures aimed at reducing fiscal deficits in the short term toward public investments, including in healthcare, with longer-term benefits. Governments should not, however, overlook how to make the best use of the available resources and should consider all relevant effects, whether positive or negative, when making resource allocation decisions. In difficult economic times it becomes even more important to use resources where they bring the best returns to the economy.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The work on this paper conducted by Martina Garau, Koonal Shah, Priya Sharma, and Adrian Towse was funded by Eli Lilly and Company. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript.

Supplementary material

The Aspen Institute

©2024 The Aspen Institute. All Rights Reserved

- 0 Comments Add Your Comment

Exploring the Important Link Between Health and Wealth

November 5, 2019 • Rhett Buttle & Financial Security Program

Over the past several months, the Aspen Institute’s prestigious programs, the Financial Security Program and the Health, Medicine and Society Program, embarked on a unique collaboration to explore the link between good health and financial wellbeing.

The connection between financial wellness and health is significant, with evidence showing that increased financial security is linked to improved health outcomes and improved quality of life. What’s more, finance and health are among the fastest-growing sectors of the economy — in the US, they comprise more than 40 percent of GDP — and both are targets of innovation.

Research has found that more than half of an individual’s life expectancy in the DC region could be explained by education and economic factors. According to another report, income growth not only correlates to life expectancy increases, but also to a decrease in the risk of chronic illness and an increase in access to resources that promote longevity and health. Other research has shown that financial insecurity is a serious source of mental stress, reducing an individual’s productivity and job performance. And yet more research notes that poor physical health directly impacts financial stability, increasing the likelihood of personal bankruptcy from medical debt.

Stakeholders across public, private, and philanthropic sectors are increasingly convinced of the necessity of a multidisciplinary approach that would result in solutions designed to tackle issues related to both economic and health inequality. Some of these efforts are being driven by the changes we are seeing in our economy — for example, the growth of the “gig” economy, high levels of debt, record income disparities, and challenges to retirement security that are all leaving their mark on an individual’s health. With economic structures in transition, entrepreneurs are beginning to link up with care providers and health advocates are promoting microenterprise. So, what does the link between health and wealth mean in this evolving economy?

Given these developments and questions, our collaboration sought to explore the connection between these two fields. Our work has manifested itself in two ways.

A Set of Exploratory Roundtables

First, the programs co-hosted a set of roundtables — one in Washington, DC, and one in San Francisco, CA — with key stakeholders from both fields. Each roundtable included approximately 20 to 30 sharp minds, including public health, healthcare, and financial security leaders from across academia, business, community-based and advocacy organizations, and other appropriate experts. The roundtables began a necessary dialogue, promoted an open space, and fostered trust in order to identify and discover areas of partnership.

Integrating Health & Wealth into the Aspen Ideas Festival

In addition to the roundtables, we brought the conversation to Aspen Ideas: Health (the three-day opening event of the Aspen Ideas Festival). There, we produced a track (or “theme”) focused exclusively on Health & Wealth. Content included a conversation with the US Surgeon General and the President of the Federal Reserve of Philadelphia, who explored ways that their jobs and missions are both fundamentally geared toward advancing the health of America’s families, communities, and economy. We also featured several business leaders who spoke to the business case for thinking about health and wealth together, and how both sectors can do more to ensure that the end goal of business aligns with helping households experience greater wellbeing. Another panel looked at how a living wage can create better health outcomes, and another explored how the growing burden of medical debt is one of the most common financial burdens for Americans. Attendees left increasingly aware that health and financial wellness are fundamentally linked.

What’s Next

These times require an authentic conversation about the substantial financial challenges facing our families — and increasing financial insecurity more broadly. Examining the connection between health and financial security is at the heart of this — and, we believe, the right place to start.

It is our hope that in partnership with several of the Institute’s policy programs — the Financial Security Program and the Health, Medicine and Society Program — we can explore an effort that combines each program’s networks, learnings, and expertise. Working together, the programs can move forward with the opportunity to examine the common essential building blocks of healthcare, medicine, wellness, and financial well-being. The true power in this effort comes from the ability to examine problems in new ways, integrate networks, and explore innovative solutions that stem from real collaboration. Through public convenings — and intensive, off-the-record dialogues with leaders from a wide cross-section of private, public, and nonprofit institutions — the Aspen Institute can play a lead role in advancing a conversation on how to improve health and wealth in tandem.

Long-lasting improvement on the issues of financial and health inequality requires multidisciplinary solutions that embrace the inter-relatedness of these issues. Improving health outcomes will allow people to live longer and healthier lives, and participate more fully in the economy. Coming together with a diverse set of committed leaders, we can effect change and improve the lives of millions.

Related Posts

April 8, 2024 Sohrab Kohli & 1 more

April 5, 2024 Riani Carr & 2 more

The best of the Institute, right in your inbox.

Sign up for our email newsletter

- International Network

- Policy Papers

- Opinion Articles

- Historians' Books

- History of Government Blog

- Editorial Guidelines

- Case Studies

- Consultations

- Hindsight Perspectives for a Safer World Project

- Global Economics and History Forum

- Trade Union and Employment Forum

- Parenting Forum

Health and Wealth

Simon szreter | 07 november 2005.

Executive Summary

- Hindsight: contemporary international policies to promote economic growth and development are too often premised on a view of the past distorted by hindsight and unwitting present-centredness.

- Disruption: history teaches that economic growth is a profoundly disruptive and uncertain process, particularly with respect to population health.

- Information: essential public-health intelligence and even the registration of individual identities is lacking in many poor countries today, unlike in the European past.

- Social security: a system is lacking in most poor countries, yet the English Poor Law was crucial in facilitating development in the world's first industrial nation.

- Democracy: the relationship between democratisation and development is not straightforward. Healthy democracies need representative, independent local government, balanced by national, central government, not just votes for all.

- Social capital: the diverse and changing structures of relationships of trust and respect in society have great influence over all forms of policy implementation.

- Time: history teaches respect for thinking with appropriate units of time. Development processes occur in generations- quarter and half centuries- not annual accounting units or 5-year electoral cycles.

History and Policy: the historicist perspective

As its title indicates Health and Wealth. Studies in History and Policy (H&W) is a volume of essays intended to exemplify the purpose of the History and Policy website and the new History and Policy unit established at the Centre for Contemporary British History. H&W demonstrates how history can be deployed extensively to re-think major topics in the social and policy sciences concerning economic change and health.

The chapters of H&W present a series of revisionist historical articles published since 1988 on mortality change in Britain during the last three centuries. These chapters challenge orthodox and conventional social and policy-science views of the processes that govern the relationship between modern economic change and population health. By providing distinctive historicist perspectives, they also suggest a number of positive alternatives for contemporary development and public-health policies, which will be summarised here.

The historicist perspective in H&W seeks to avoid the fore-shortening and 'straightening-out' of time through the distorting lens of hindsight. This is one of the characteristic flaws of the contemporary social sciences in their attitude towards the past. History is too frequently seen merely as the sign-posted path to the present, as if everybody in the past (or the most important and progressive elements) somehow knew that they were headed towards the society and economy which we currently inhabit. According to this viewpoint, the only real question is how long did they take to get here? How fast was the rate of economic growth in different periods and what interfered with it or promoted it? When did our society pass through the different stages of the demographic transition to arrive in modernity? The first and cardinal point to emerge from adopting an historicist perspective is to recover the prospective indeterminacy of the past.

The people who populated the past did not know where they were going, just as we cannot predict with any confidence at all what kind of society or economy our grandchildren will inhabit in a hundred years' time. Like us, people in the past had dreams and ideals, fears and aspirations, but they certainly were not the same as ours and they were mostly to do with the next year, five years or ten years ahead of them.

Economic change, disruption and uncertainty

Most of the articles in Health and Wealth explore the history of demographic change in Britain during and after the industrial revolution, c. 1750-1914. The first insight to emerge from adopting an historicist perspective is that the economic growth occurring in Britain during this period was intensively and extensively disruptive. It is argued in H&W that this is an important general characteristic of 'successful' national economic growth almost everywhere that it occurs. Societies, governments and international NGOs working today to promote economic growth in the world's many poorer countries frequently fail to appreciate that the very goal which they are striving to bring about, and which would count for them as an index of their success- consistently rising rates of growth of national income- will bring with it a wide range of profoundly de-stabilising forces. It is not just absence of economic growth that can be a problem: its presence will also cause numerous difficulties, though they will be different ones.

Widespread poverty, lack of opportunity for whole sections of society such as women and children, and the pain and loss of emigration may characterise life in societies lacking economic growth. However, the first and greatest economic 'success' story of all, the industrial revolution in Britain, also shows that the achievement of economic growth in such societies will exacerbate migration rates from some regions still further; cause local or even regional-scale environmental hazards, such as water shortages, occupational diseases and air pollution; and will divide communities, families, and generations as relative values of assets are altered and some adopt new ideals and models of behaviour, while others cleave to established norms. Changing economic fortunes for some will also produce intense political uncertainty and turmoil in a social landscape where there are frequently as many who perceive themselves to be directly disadvantaged and their conditions of life threatened by economic change.

The counsel of history is not, however, the Luddite one of rejecting the goal of economic growth as not worth the trouble. Human aspirations to escape material poverty and to pursue self-fulfilment are valid and, apart from ascetics, universal; they both entail the desirability of economic growth. The purpose and value of arming oneself with a thoroughly historicist understanding of the difficulties involved in taking this crooked path is precisely to make it possible to negotiate effectively the bewildering and un-signposted road ahead, fore-warned with a more realistic set of general expectations about the chaos and disruptions that must be faced.

The orthodox social-science and development models tend not to portray such a picture of an intrinsically disruptive process. This is for the simple reason that they are not constructed to do so. Part One of H&W deploys the methods of historical enquiry to show how some of the most influential social-science models in the post-war era, such as the theory of demographic transition and the 'Mckeown' thesis of nutritional improvements driving mortality decline, were developed and deployed to provide reasoned support for selective policy goals. They were constructed teleologically as guides to positive action in the present and the future, utilising selective accounts of historical change to show that history had apparently moved in the manner, which, they were advocating, should now be followed.

A genuinely historicist account does not portray such perfectly accomplished teleology. Historical research more typically uncovers false starts, paths taken then abandoned, unintended consequences, conflicts, uncertainties and plain old-fashioned mistakes. However, the fact that the historical path is so crooked and pot-holed that nobody in their right mind would want directly to attempt to emulate it does not mean that there can be no helpful advice to be gleaned from the study of history. Indeed, it is in order not to repeat in ignorance all the follies of the past that one can usefully study history. For instance, one such helpful piece of historicist advice is to be prepared for a rough and dangerous ride in a society embarked on the experience of rapid economic growth, especially if this is for the first time in its history. A second general piece of advice is that the civic and political institutions a country possesses at the outset will be extremely important in influencing just how rough the ride can get; and they will have to adapt to change more rapidly than can often be easily achieved.

Both these pieces of historicist advice have very direct, practical policy implications, namely that just as much attention needs to be paid by those in government or by international NGOs to the form, vigour and adaptability of crucial civic and political institutions, as to the openness of the economy and its financial institutions or to the state of schools, roads and hospitals. They should be prepared in advance to cope with the eventuality that rising per capita national income will very probably be accompanied by social disruptions and health problems, so as not to be disagreeably taken by surprise once economic 'success' begins to exert these influences.

The chapters in Part Two of H&W investigate how and where such disruptive problems were precisely manifest in British history. It finds that among the English population there were grossly adverse health and mortality consequences of rapid economic growth. These were in fact concentrated among the urban proletariat in precisely the same locations where the new industrial wealth was being generated, the factory cities. Immigrants from both the rural hinterland and from Ireland (even before the famine added extra impetus) came to find work and higher wage rates; but equally frequently they and their wives and children also found higher death rates.

The importance of public-health information: vital statistics

Unlike many of the poorest nations in the world today, the English, by the beginning of the 1840s, did at least possess a sophisticated public-health intelligence system and these high urban death rates were increasingly analysed and denounced as 'preventable' by the government's own officials. One of the many important, albeit conditional, lessons of British history in the nineteenth century is that authoritative, universal and high quality public-health information is a necessary- but, alas, not sufficient- item of institutional machinery, which societies require in order to be able to address the epidemiological problems which economic growth, trade and increasing density of urban settlement inevitably produce. A comprehensive public-health information system is not a high priority among many of today's least developed nations and it is a great disadvantage which they labour under, neither knowing where and whom their worst health problems afflict, nor whether any remedial measures are truly taking effect.

H&W is able to show that, through the effective public-health propaganda machine of the General Register Office, the Victorian urban, middle and upper classes were never under any illusions as to the unhealthy state of their towns, even during the periods of relative respite between cholera visitations. By the 1830s and 1840s mortality was probably higher in most industrial towns than it had been at any point in the previous 100 years of their development. Since we can be sure that the Victorians were not simply ignorant of their predicament, this helps to identify other factors which prevented them from acting on this knowledge. It was not all towns, but especially those where the new industrial and commercial wealth was being made, which were especially unhealthy. Furthermore, health in such towns distinctly deteriorated in the 1830s and 1840s as diseases such as smallpox, almost eliminated two decades previously by vaccination, returned; and others, such as cholera, struck for the first time.

'Democratisation': not a simple panacea

The thesis developed in Part Two of Health and Wealth is that all manufacturing cities, such as Glasgow, Manchester and Liverpool, but also smaller ones such as Carlisle, Warrington or West Bromwich, became politically and administratively hamstrung for over half a century from the end of the Napoleonic Wars. This happened because of the unintended consequences of partial, 'democratic' reform of the polity. In common with the 1832 'Great' parliamentary Reform Act, the 1835 Municipal Reform Act gave votes to moderate property holders. Town government passed out of the hands of a narrow wealthy oligarchy and into those of a 'shopocracy' of petty bourgeois ratepayers. The highly restricted borrowing powers of urban corporations were already the source of serious problems, preventing these fast-growing towns from undertaking costly sanitary and environmental infrastructure projects: resulting, for instance, in the water supplies often being sold to private companies in the forlorn hope that they would make improvements to capacity, which the town's authorities were statutorily unable to undertake. For a whole further generation after 1835, while Britain's industrial towns expanded into crowded cities, their petty capitalist ratepayers refused to vote for anything except policies of do-nothing 'economy'.

Central government tried to force their hands with the 1848 Public Health Act but this was largely rebuffed. Borrowing and expenditure statistics clearly show that British cities did not really begin to invest in the expensive sanitary works which the 1848 Act hoped to encourage until the 1870s, when their electorates began to express support for such measures. This did not happen until after the municipal electorates were substantially extended in 1869. At that point a new generation of urban neo-patricians, led by the industrial magnate Joseph Chamberlain in Birmingham, realised that it was now possible to appeal with a municipal spending programme over the heads of the petty bourgeois to the non-rate-paying but voting working class. The largest employers and their workers both stood to benefit substantially from collective expenditure on the urban environment, which would boost the health and productivity of the workforces, while the petty bourgeoisie were now, finally, co-opted into helping to pay for it.

Although the exact course of historical events summarised here is specific to Britain in the nineteenth century and will never be precisely repeated again anywhere else, this does not mean there are not any generalisable policy lessons that can be drawn. In fact it is only by paying careful attention to this genuinely historicist version of British economic and demographic history- the crooked path of pitfalls, false turns and grubby local politics- that policy makers can learn anything they do not already know. The smoothly-surfaced high-road of models of historical change based on inspecting secular trends in national economic growth rates and aggregate demographic indices is, after all, merely a historical mirror reflecting back our own contemporary goals, wishes and assumptions.

There are, then, a number of specific but generalisable lessons about the relationship between economic change and population health, which can be gleaned from the historicist perspective on nineteenth-century British history, and these are elaborated in Part Three of H&W . These 'lessons' could be applied to societies undergoing rapid economic growth for the first time under political regimes that are at least moderately liberal and partially 'democratic', which probably covers most poor countries today, excluding those which are effectively one-party states or subject to dictatorial rule.

Firstly, the analysis in H&W demonstrates that the expansion of democracy per se under conditions of economic growth has no necessary beneficial health effects. Increasing degrees of 'democratisation' can have entirely diverse consequences. Careful attention must be paid to issues of representation, to the local details of franchise extensions and to the precise political means available for the opinion of the poor to be influenced and expressed (issues of public information media and party organisation). The interests of those who are given voting power and how this relates to those other sections of the population (children for instance in today's poor countries) who remain excluded cannot be ignored. Given the unavoidably expensive nature of maintaining- let alone improving- population health under the conditions of the large-scale urbanisation and migration which invariably accompany rapid economic growth, this can determine whether or not the political conditions exist at all for the required collective action to implement health-preserving technologies. In Britain the wrong kind of 'democratisation' of the national and urban electorates produced unbreakable political stalemate for a generation after the 1830s, while urban environments deteriorated and public health suffered.

Central and local government: a delicate balancing act

Secondly, H&W indicates that the exact relationship between central and local government may well be a crucial one. Imbalances of power in either direction may be counter-productive. Too much power and talent at the centre, as in Britain in the 1830s and 1840s, may result in a counter-productive, one-size-fits-all dictatorial style, undermining the vigour of provincial governments and only eliciting evasion or even rejection in the provinces of initiatives from the centre. Local representative and elected governments which are endowed with genuine independence, powers, status and resources, will very likely generate a competitive political forum across the nation of (literally) healthy rivalry among them. The centre may well be able to foster such productive competitiveness through a judicious policy of both financial and honorific carrots and sticks.

Relations between centre and periphery are probably optimal when characterised by a diplomatic and mutually respectful relationship based on genuine relative autonomy, rather than by relations of dependence (or complete independence), with the centre both prepared to learn from provincial innovations taken by energetic local authorities and to encourage and incentivise the spread of best practice where initiative is lacking. This characterised relations between central and local government in Britain over matters of health policy during the era of the Local Government Board, 1870-1919, when much was achieved in the improvement of the urban population's health.

The importance of public servants, professionalism and social capital

Thirdly, the effective delivery of health-preserving and enhancing services under the challenging conditions of rapid economic growth will require motivated bodies of trained and committed personnel at ground level. In British history this took the form of a combination of an expansion in long-standing religiously-motivated voluntary philanthropic organisations and the new growth of 'public service professions'. The latter were mainly employees of elected local governments, possessing specialist knowledge and training supervised by professional examining bodies (institutions licensed by the central state to exert independent and accountable control over an area of formal knowledge deemed to have direct, public importance). The generalisable point is the importance of creating a dutiful, committed, impartial and highly professional bureaucracy to serve elected local government, with rewards so scaled that professional talent does not leach away from the provinces to the centre.

Fourthly, H&W points to the manifold importance of 'social capital'. Social capital refers to the patterned structure of relationships which, often invisibly, criss-cross and structure society through the operation of networks and their associated norms. Social capital is a more general concept than 'civil society' because in principle it embraces all forms of networks, formal and informal, including nepotistic and 'hidden' ones - those which do not necessarily benefit the wider collectivity - as well as those which are more open, such as the many voluntary societies which exist to pursue harmless leisure activities or laudable, public aims. Social capital was significant in throwing up barriers to collective action by contributing to the mutually distrustful fissuring of British urban communities under the severe pressures of rapid growth during the first half of the nineteenth century. But social capital was also important in the changed context of the late 1860s and 1870s in enabling collective municipal action, providing both Chamberlain personally and the local Liberal party in the city of Birmingham with diverse means of communication and mobilisation to achieve electoral support for a new municipal politics of urban improvement and spending.

Social capital is also important in another way, in relation to the manner in which public-health and social services are delivered. Such services typically require extensive interaction between service providers and clients. Physical capital, facilities and medical science are of course also all involved, but maintaining or improving the health of whole urban populations which are having to adapt to the new environmental challenges thrown up by rapid economic growth requires much face-to-face interaction, especially between the poor, the displaced and the disoriented on the one hand, and various categories of officials and trained workers such as nurses and health visitors on the other. The quality of the human relationships characterising these interactions can be critical. The concept of linking social capital discussed in H&W emphasises how important are norms of respect governing this relationship, something which can be very difficult to achieve given the imbalance of power and expertise between professional and client in these circumstances. It is too easy for the possession of superior knowledge to become a stick with which to beat the poor. The vital ethos of professionalism in the public services has to include genuine respect for those with whom it works.

Systems of social security: a neglected lesson of history

Fifthly, there is the enormous significance in all polities of social security systems. At the minimum this is provided universally by kin and neighbours. Wider resources and agencies are, however, typically also involved in most societies, such as religious, philanthropic and mutual self-help organisations. Most economic, social, medical and policy scientists and NGOs operating in the 'development' field would assume that nationally-organised, government-based, official social-security systems are historically a relatively recent addition, famously innovated by Bismarck in the new German Empire in the 1880s, developed more extensively by Denmark and Sweden in the twentieth century and achieving their most developed form as 'the welfare states' of post-war western Europe. Such comprehensive social-security systems appear in this perspective to be the final fruits of decades of economic growth; and there are many economists who have serious reservations about their consequences for the vigour of national economies- doubts which have arguably prevented the USA from following the west European lead.

However, as the final chapter of H&W argues, a more thorough knowledge of British history transforms such assumptions about the historical relationship between national social-security systems and economic growth. Britain, the world's first and only example of self-induced rapid economic growth and industrialisation, possessed a fully-functional national statutory social-security system for two centuries before the industrial revolution. The Poor Laws, enacted in the reign of Elizabeth I, endowed the country with a uniquely comprehensive social-security system. Dutch historians have identified this as having given the British agrarian economy a crucial advantage in terms of the market flexibility and mobility of the primary factors of production, land, labour and capital. This was an important contributory factor enabling the British economy in the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to overtake the leader, Holland. Paradoxically the British 'free market' economy flourished as no other at the time because of the unparalleled strength not only of the central state in providing external military security and protecting the textile industries, but also because of the generous provision of domestic social security by the local state. The neo-liberal consensus that has emanated from the world's great financial institutions in Washington and New York for the last quarter century has been entirely ignorant of these lessons of history.

Identity and registration: back to the importance of information

A sixth lesson is the importance of civic-identity registration. This, like the social-security system, was another central-government-sponsored and locally-organised foundational element in the story of precocious economic and social development in England. The flowering of a widely-spread property-owning and property-disposing agrarian and commercial middle class of improving landowners, yeoman-farmers and merchants was a major feature of British agrarian capitalism. Access to a cheap and effective system for proving legal identity was as important for the smooth working of a society used to exchanging and inheriting property as it was for the smooth operation of the social-security system. For this aspect of British history to be emulated in today's poorer countries would require a government or World Bank-funded network of trustworthy and secure civil registers, proof from the possible abuse of such information by unscrupulous commercial or official agencies. Not easy to achieve. But without this, the citizens and would-be capitalists of poor countries are alike labouring under severe burdens of basic information deficits, like their public-health systems in the absence of public-health intelligence (something which in Britain's case was generated very economically as a by-product of its civil registration system).

The last lesson of history: the importance of time

Finally, an historical approach to studying economic and demographic change emphasises the importance of time. The social and policy sciences tend to have an unrealistic, almost frenetic conception of time. Policies are expected to demonstrate effects within a year or two. Partly the result of electoral cycles in democracies, five years is today considered a maximal time horizon by most governments or NGOs- ironically the same accounting unit envisaged by the proud and impatient planners of the USSR. But, being such a disruptive and chaotic process, economic growth and its evolving relationship with the environment and with population change and public health is a large-scale process, whose consequences tend to unfold in decadal and generational, rather than annual units of time. Policies designed to work at the appropriate scale and level themselves require to be conceptualised according to such time-scales.

Furthermore, as has been illustrated by the regionally-devastating HIV-AIDs pandemic of the last quarter century, when disruptive economic change does cause things to go wrong from a health point of view, it can be on a colossal scale, both temporally and geographically, with major economic consequences. It is questionable whether the world's international development institutions or the governments of poorer countries have ever truly understood this prime lesson of history. It was a wholly realistic assessment of the national insecurities and potential costs arising from such calamities, which was a part of the rationale behind the English state launching its pioneering, comprehensive social-security system in the sixteenth century, resulting in the historical fact that England achieved freedom from any famine-induced mortality well over a century before any other part of Europe. If this had been given the highest development policy priority, which history suggests it should have had during the last half-century, who can say how different the impact and cost of AIDs would have been? Would we have seen the recurring regional famines which are a blight on our age if the world's poorest countries had been encouraged instead to build for themselves a proper social-security system before being exposed to the necessary disruptions of the global economy?

- Szreter, Simon

- Medicine and public health

- Public services and social policy

Further Reading

Simon Szreter, Health and Wealth: Studies in History and Policy , Rochester Studies in Medical History (Rochester University Press 2005).

About the author

Simon Szreter is Reader in History and Policy, Faculty of History, University of Cambridge and Fellow of St John's College. With Alastair Reid, he is a founding editor of the History and Policy website. [email protected] .

Related Policy Papers

Democratisation: historical lessons from the british case, john garrard | 04 may 2004, a central role for local government the example of late victorian britain, simon szreter | 02 may 2002, papers by author, papers by theme, digital download.

Download and read with you anywhere!

- Download Kindle Version

- Visit Apple iBooks Store

Popular Papers

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Sign up to receive announcements on events, the latest research and more!

To complete the subscription process, please click the link in the email we just sent you.

We will never send spam and you can unsubscribe any time.

H&P is based at the Institute of Historical Research, Senate House, University of London.

We are the only project in the UK providing access to an international network of more than 500 historians with a broad range of expertise. H&P offers a range of resources for historians, policy makers and journalists.

Publications

Policy engagement, news & events.

Keep up-to-date via our social networks

- Follow on Twitter

- Like Us on FaceBook

- Watch Us on Youtube

- Listen to us on SoundCloud

- See us on flickr

- Listen to us on Apple iTunes

Health Thesis Statemen

Navigating the intricate landscape of health topics requires a well-structured thesis statement to anchor your essay. Whether delving into public health policies or examining medical advancements, crafting a compelling health thesis statement is crucial. This guide delves into exemplary health thesis statement examples, providing insights into their composition. Additionally, it offers practical tips on constructing powerful statements that not only capture the essence of your research but also engage readers from the outset.

What is the Health Thesis Statement? – Definition

A health thesis statement is a concise declaration that outlines the main argument or purpose of an essay or research paper thesis statement focused on health-related topics. It serves as a roadmap for the reader, indicating the central idea that the paper will explore, discuss, or analyze within the realm of health, medicine, wellness, or related fields.

What is an Example of a Medical/Health Thesis Statement?

Example: “The implementation of comprehensive public health campaigns is imperative in curbing the escalating rates of obesity and promoting healthier lifestyle choices among children and adolescents.”

In this example, the final thesis statement succinctly highlights the importance of public health initiatives as a means to address a specific health issue (obesity) and advocate for healthier behaviors among a targeted demographic (children and adolescents).

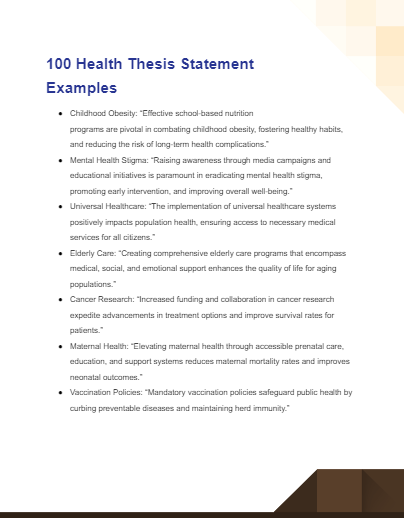

100 Health Thesis Statement Examples

Size: 191 KB

Discover a comprehensive collection of 100 distinct health thesis statement examples across various healthcare realms. From telemedicine’s impact on accessibility to genetic research’s potential for personalized medicine, delve into obesity, mental health, antibiotic resistance, opioid epidemic solutions, and more. Explore these examples that shed light on pressing health concerns, innovative strategies, and crucial policy considerations. You may also be interested to browse through our other speech thesis statement .

- Childhood Obesity : “Effective school-based nutrition programs are pivotal in combating childhood obesity, fostering healthy habits, and reducing the risk of long-term health complications.”

- Mental Health Stigma : “Raising awareness through media campaigns and educational initiatives is paramount in eradicating mental health stigma, promoting early intervention, and improving overall well-being.”

- Universal Healthcare : “The implementation of universal healthcare systems positively impacts population health, ensuring access to necessary medical services for all citizens.”

- Elderly Care : “Creating comprehensive elderly care programs that encompass medical, social, and emotional support enhances the quality of life for aging populations.”

- Cancer Research : “Increased funding and collaboration in cancer research expedite advancements in treatment options and improve survival rates for patients.”

- Maternal Health : “Elevating maternal health through accessible prenatal care, education, and support systems reduces maternal mortality rates and improves neonatal outcomes.”

- Vaccination Policies : “Mandatory vaccination policies safeguard public health by curbing preventable diseases and maintaining herd immunity.”

- Epidemic Preparedness : “Developing robust epidemic preparedness plans and international cooperation mechanisms is crucial for timely responses to emerging health threats.”

- Access to Medications : “Ensuring equitable access to essential medications, especially in low-income regions, is pivotal for preventing unnecessary deaths and improving overall health outcomes.”

- Healthy Lifestyle Promotion : “Educational campaigns promoting exercise, balanced nutrition, and stress management play a key role in fostering healthier lifestyles and preventing chronic diseases.”

- Health Disparities : “Addressing health disparities through community-based interventions and equitable healthcare access contributes to a fairer distribution of health resources.”

- Elderly Mental Health : “Prioritizing mental health services for the elderly population reduces depression, anxiety, and cognitive decline, enhancing their overall quality of life.”

- Genetic Counseling : “Accessible genetic counseling services empower individuals to make informed decisions about their health, family planning, and potential genetic risks.”

- Substance Abuse Treatment : “Expanding availability and affordability of substance abuse treatment facilities and programs is pivotal in combating addiction and reducing its societal impact.”

- Patient Empowerment : “Empowering patients through health literacy initiatives fosters informed decision-making, improving treatment adherence and overall health outcomes.”

- Environmental Health : “Implementing stricter environmental regulations reduces exposure to pollutants, protecting public health and mitigating the risk of respiratory illnesses.”

- Digital Health Records : “The widespread adoption of digital health records streamlines patient information management, enhancing communication among healthcare providers and improving patient care.”

- Healthy Aging : “Promoting active lifestyles, social engagement, and cognitive stimulation among the elderly population contributes to healthier aging and reduced age-related health issues.”

- Telehealth Ethics : “Ethical considerations in telehealth services include patient privacy, data security, and maintaining the quality of remote medical consultations.”

- Public Health Campaigns : “Strategically designed public health campaigns raise awareness about prevalent health issues, motivating individuals to adopt healthier behaviors and seek preventive care.”

- Nutrition Education : “Integrating nutrition education into school curricula equips students with essential dietary knowledge, reducing the risk of nutrition-related health problems.”

- Healthcare Infrastructure : “Investments in healthcare infrastructure, including medical facilities and trained personnel, enhance healthcare access and quality, particularly in underserved regions.”

- Mental Health Support in Schools : “Introducing comprehensive mental health support systems in schools nurtures emotional well-being, reduces academic stress, and promotes healthy student development.”

- Antibiotic Stewardship : “Implementing antibiotic stewardship programs in healthcare facilities preserves the effectiveness of antibiotics, curbing the rise of antibiotic-resistant infections.”