Screen Rant

Frida review: frida kahlo’s complex life gets a unique personal spotlight in compelling documentary.

Frida explores the life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo using her own words, painting a compelling picture of her life in this striking documentary.

- Frida explores the life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, using both her art and her writings to reflect her complex life.

- Narratives from her diary entries and letters provide insight into how her life influenced her art.

- The documentary combines real-world visuals with Kahlo's paintings to capture the essence of her intertwined life and art.

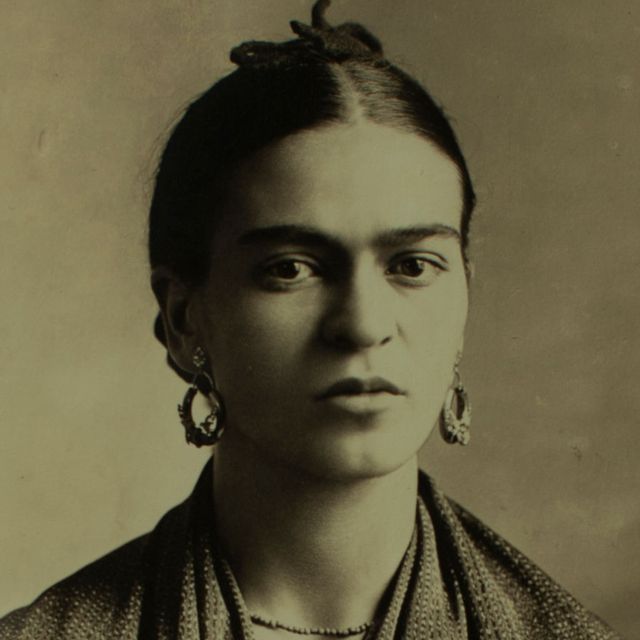

Artist Frida Kahlo is one of the most recognizable Mexican painters in history. Known for the portraits and self-portraits she painted throughout her life, she utilized surrealism to create art that was both historical and autobiographical. In addition to her paintings, she wrote extensively about her life in diary entries, letters, and essays, crafting a much larger view of who she was as a person. All her work intersects in Frida , a 2024 documentary directed by Carla Gutiérrez about her life told through the words and images she created.

Frida is a documentary film by director Carla Gutierrez released in 2024. Gutierrez takes viewers on a journey through the life of the Mexican painter Frida Kahlo by narrating it from the first person and using various narrative devices such as animations and interviews to help explore her world as she saw it.

- Frida adds complexity to the painter's life by using her own words

- Through moving artwork & narration, Kahlo's life is deeply explored

- Frida has a great visual style that makes for a compelling watch

- Frida captures how Kahlo's life and art informed one another

Frida Is A Stylistic Display Of An Artist's Life

Kahlo's paintings and writings are on full display..

While Frida shares the same name as the 2002 film where Salma Hayek plays the titular artist, the documentary has a clear focus on Kahlo's own words and paintings. Stylistic animations breathe vivid life into her most famous artwork, turning them into living parts of the documentary. These works are presented at various points throughout her life, oftentimes reflecting the intersection between her experiences and her creations. While the decision to animate her paintings is an unusual one that takes some getting used to, their lively presentation resonates with the documentary's purpose.

These animations are accompanied by a narrative woven within her writings, read throughout by actor Fernanda Echevarría del Rivero. Diary entries and letters reveal the extent to which the positive and negative elements of her life influenced her creations. They make up the backbone of the film's narrative, telling the story of her life experiences through an autobiographical perspective. Kahlo's artwork and writings compliment one another, revealing just how influential the complexities of her personal life were with her art.

Frida (2024)

Beyond what she herself created, the documentary bolsters the narrative of Kahlo's life with photos and videos of her spanning nearly five decades. These real-world visuals help highlight the documentary's purpose as an examination of her life through her own eyes. They also provide a contrast between the surrealist, oftentimes fantastical world of her artwork to the grounded nature of reality. By using photos and videos of her, Frida expertly captures the essence of how her life and art intertwined throughout the years.

10 Best Biopics About Iconic Women

Frida reveals the captivating story behind the famous mexican artist, the artist's personal life is a major focus of the documentary..

The Prime Video documentary captures the essence of who Kahlo was as a person, both within herself and to those around her. Frida displays her questioning, rebellious attitude, notably through her interactions with religion and sexuality throughout her life. These make their way into her personal life, and thereby her paintings, offering a close study of her relationship to these topics through her own eyes. The same form of presentation appears as parts of her life are explored, such as a life-altering accident and a tragic loss after her marriage.

The intersection between her real-world experiences and their reflections in her artwork make the documentary as close as the world will come to knowing how she felt through the many stages of her life.

One engrossing, focal section includes her relationship with fellow artist Diego Rivera , whose murals were just as renowned as Kahlo's paintings. These moments showcase how Kahlo fit into the wider world of Mexican art in the early 20th century, as constructed through her often imperfect marriage. They're also contrasted with other, more tender moments in the form of her love letters, their varied prose revealing her innermost desires. While this occasionally leads to some repetitious moments in the documentary, they prove important to understanding Kahlo beyond her artwork.

With a variety of art and writings reflecting her life, Frida takes an honest look at the complex painter through her own eyes in a creative and informative way. The intersection between her real-world experiences and their reflections in her artwork make the documentary as close as the world will come to knowing how she felt through the many stages of her life. While the information on display may be familiar to those who know of Kahlo, her own perspective is a powerful one. Informative for newcomers and the familiar, Frida is a must-watch biography.

Frida is now available to stream on Prime Video.

The Definitive Voice of Entertainment News

Subscribe for full access to The Hollywood Reporter

site categories

‘frida’ review: a portrait of frida kahlo that’s a triumph of deep-dive research and dynamic artistry.

The debut doc by editor Carla Gutiérrez explores the great Mexican artist’s life and work through her own words.

By Sheri Linden

Sheri Linden

Senior Copy Editor/Film Critic

- Share this article on Facebook

- Share this article on Twitter

- Share this article on Flipboard

- Share this article on Email

- Show additional share options

- Share this article on Linkedin

- Share this article on Pinit

- Share this article on Reddit

- Share this article on Tumblr

- Share this article on Whatsapp

- Share this article on Print

- Share this article on Comment

My guess is that Frida Kahlo would have loathed “Immersive Frida Kahlo,” the kind of touring exhibit that professes to honor the canvas while bathing it in digital-tech kitsch. And, having seen Carla Gutiérrez’s riveting documentary Frida , I’m certain the artist would have announced her disdain with a laugh and a healthy dose of juicy invective. If you want to immerse yourself in Frida Kahlo, here is the real thing.

Related Stories

With the departure of its ceo, sundance now must chart a new course, hot docs fest artistic director, programmers exit amid financial crunch.

Whatever that 2002 movie’s strengths and weaknesses, Gutiérrez’s nonfiction portrait (which takes its streaming bow March 15 on Prime Video) is, for starters, uncluttered by the layers of performance that define biographical drama. Frida ’s voice cast never diverts attention from the heart and soul of the story, and the exquisite work by Fernanda Echevarría del Rivero, as Kahlo, brings the great artist’s joys, sorrows, fierce intelligence and mouthy humor to life with an intense person-to-person intimacy.

The doc takes rewarding chances in its treatment of Kahlo’s artwork, chances that heighten the emotional connection between the painter and the image without overstepping. With sensitivity and elegance, animation by Sofía Inés Cázares and Renata Galindo adds movement to elements of the paintings and zeroes in on details: A Chihuahua’s tail wags, a plant’s leaves unfurl and sway, the earth cracks. If at certain moments the animation feels unnecessary given the sheer power of the imagery, it’s always in sync with the mood Kahlo is expressing, whether that mood is playful, celebratory or despairing.

As to the biography itself, it begins with photos of a plump toddler with a discerning gaze — hardly a surprise that she would soon be a smartass kid tossed out of class for pestering the priest with questions, or that, as a teen burning with intellectual and sexual hunger, she would hang out with the rebellious boys. Art was not Kahlo’s Plan A; she wanted to be a doctor, but a horrendous 1925 bus accident, when she was 18, would instead turn her into a lifelong patient. “The handrail,” Kahlo recalled, “went through me like a sword through a bull.” The free spirit was trapped, “alone with my soul,” and she began painting.

Emiliano Zapata was a crucial public figure in her childhood, and the film makes clear that through everything she endured — constant physical pain, many surgeries, braces and casts, the endless infidelities of her celebrated husband, Diego Rivera — she never let go of that revolutionary outlook. Art and revolution were resolutely entwined in the frescoes of her beloved Rivera and Mexico’s other great muralists of the early 20th century, David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco. One of the many delights of Frida is hearing her exuberant cursing (via Echevarría del Rivero) about the titans of industry who commissioned works from Rivera, along with the other “rich bitches,” “jerks” and “gringos” who made her seethe.

Kahlo had her own extramarital adventures, to be sure, among her lovers the on-the-lam Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and numerous famous artists, both men and women. And yet her struggles to accept Rivera’s affairs, as expressed in her writings, are wrenching; they cut through the simplistic “strong woman” stereotype to reveal the anguish and vulnerability that are often strength’s essence.

Perhaps the most searing example of her piercing insight involves her interactions with the French poet André Breton. Upon a visit to Mexico, he found her paintings in sync with the work of the Surrealists, the school of art he led. She knew nothing about them, and though Breton promoted her work in Paris, he also ignited her fury with his condescending use of cheap Mexican tchotchkes in the exhibit, meant as a thematic complement to her visionary canvases. Eventually, disgusted by the armchair revolutionaries she encountered in the salons of Europe, Kahlo concluded that she hated Surrealism. “A decadent manifestation of bourgeois art,” she called it.

Full credits

Thr newsletters.

Sign up for THR news straight to your inbox every day

More from The Hollywood Reporter

2024 global box office forecast up slightly, still below last year, box office: ‘godzilla x kong’ squashes ‘monkey man’ and ‘first omen’ with $31m, woody allen on why he feels the “romance of filmmaking is gone”, bradley cooper almost quit ‘the place beyond the pines’ after script rewrite, director says, lewis hamilton says he regrets turning down role in ‘top gun: maverick’, david barrington holt, former head of jim henson’s creature shop in l.a., dies at 78.

‘Frida’ Review: Popular Mexican Painter Speaks for Herself in Doc Drawn From Kahlo’s Diaries

Editor-turned-director Carla Gutiérrez assembles a unique and visceral portrait of Frida Kahlo, weaving artist’s own writings, exclusive archival footage and animated versions of her paintings.

By Carlos Aguilar

Carlos Aguilar

- ‘Cabrini’ Review: Lifeless Religious Drama Chronicles Hardships Faced by Determined Italian Nun Who Fought for Immigrants 1 month ago

- ‘Madu’ Review: Inspirational Doc on Young Nigerian Ballet Dancer Dazzles Visually but Lacks Depth 2 months ago

- ‘Lost in the Night’ Review: Mexican Director Amat Escalante Delivers a Beguiling Class-Divide Mystery 2 months ago

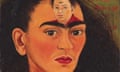

The image of Frida Kahlo, the prominent Mexican painter of the early 20 century, is one of the most replicated and commercialized of any artist in the history of the world. From T-shirts to houseware, merchandise of all sorts emblazoned with her face has turned Kahlo into a kitschy, mainstream, decontextualized emblem for Mexican identity. It doesn’t help that the vast majority of her works are self-portraits. Onscreen, the Salma Hayek-starring Hollywood biopic from director Julie Taymor and Paul Leduc’s 1983’s Mexican-production “Frida Still Life” attempted to decipher the tehuana-clad iconoclast via scripted portrayals.

Tasked with voicing Frida, performer Fernanda Echevarría del Rivero summons the woman’s defiant essence, giving precise intonation to each sentence — sometimes cheeky, others solemn — to convincingly incarnate Kahlo’s personality solely with words that accompany the visual components, including segments of previously unseen archival footage. There’s a raw, in-the-moment quality to her line delivery and to the text itself that often gives us the impression of having Kahlo adding live commentary to each of the most consequential moments of her life: the life-altering accident, her love-hate romance with promiscuous Diego Rivera, their trips to New York and Detroit (which she did not enjoy), her crushing miscarriage and her torrid affair with Soviet politician Leon Trotsky.

Still, as far as respectfully making her surrealist oeuvre part of the already rich tapestry of moving parts that comprise the doc, the choice is mostly sound. “I paint because I need to,” Gutiérrez’s Frida says. That notion that her artistic expression was an extension of her inner turmoil is confirmed by some of the supporting characters, also speaking in first-person through voice actors, namely Rivera and her friend Lucile Blanch.

If not entirely revelatory, the doc is definitely visceral. Foul-mouthed and unabashedly open about her sexual desires, the Frida we are introduced to here is unbound. One candid montage features an assortment of Kahlo’s many lovers, male and female, to illustrate her proclivity for indulging in the pleasures of the flesh. Early on, Gutiérrez makes a point of noting how even as a child, Kahlo was reprimanded for asking “improper” inquiries — that part of her remained unchanged throughout the years. So did her undying adoration for her Mexican identity to a fault, at times at odds with the patriarchal gender norms she disdained but that still applied to most other women in the country at the time.

One of the most memorable chapters epitomizes her detestation for the ultra-wealthy and pompous intellectuals who rushed to rationalize her work. Following her divorce from Rivera, Kahlo painted prolifically out of the need to support herself. She accepted exhibits in New York and later in Paris under the wing of writer André Breton, whom she came to detest. There’s a peculiar flavor to hearing her insulting their self-centered tirades about the world from their pedestals that wouldn’t come across from only reading about her dislike of them. That emotional immediacy is where Gutiérrez succeeds.

Gutiérrez, who edited the film herself, does a remarkable job harnessing the myriad of materials and keeping a steady pace for a cohesive, tight finished product — even though the cradle-to-grave structure rings obvious. “Frida” feels somewhat definitive. If you only see one filmic piece about Kahlo, this may be the one that presents the most complete overview of both the biographical highlights and her multifaceted persona behind closed doors without turning it into a didactic lesson. Even those already familiar with the trajectory of Kahlo’s existence may find the delivery here raw, vulnerable, and refreshing.

Reviewed at the Sunset Screening Room, Jan. 9, 2024. In Sundance Film Festival (U.S. Documentary Competition). Running time: 88 MIN.

- Production: (Documentary) A Prime Video release of an Amazon Studios, Imagine Documentaries, Storyville Films, Time Studios production. Producers: Sara Bernstein, Loren Hammonds, Alexandra Johnes, Katia Maguire, Justin Wilkes. Executive producers: Lynne Benioff, Julie Cohen, Alexa Conway, Brian Grazer, Ron Howard, Meredith Kaulfers, Betsy West.

- Crew: Director: Carla Gutiérrez. Editor: Carla Gutiérrez. Music: Victor Hernandez Stumpfhauser. Animation: Sofia Cázares, Renata Galindo

- With: Fernanda Echevarría Del Rivero

More From Our Brands

Beyoncé becomes first black woman to nab number one country album with ‘cowboy carter’, how todd snyder is decoding luxury menswear for a new generation, purdue, uconn advance as host committee seeks another final four, the best loofahs and body scrubbers, according to dermatologists, march madness 2024: how to watch iowa vs. south carolina in women’s national championship, verify it's you, please log in.

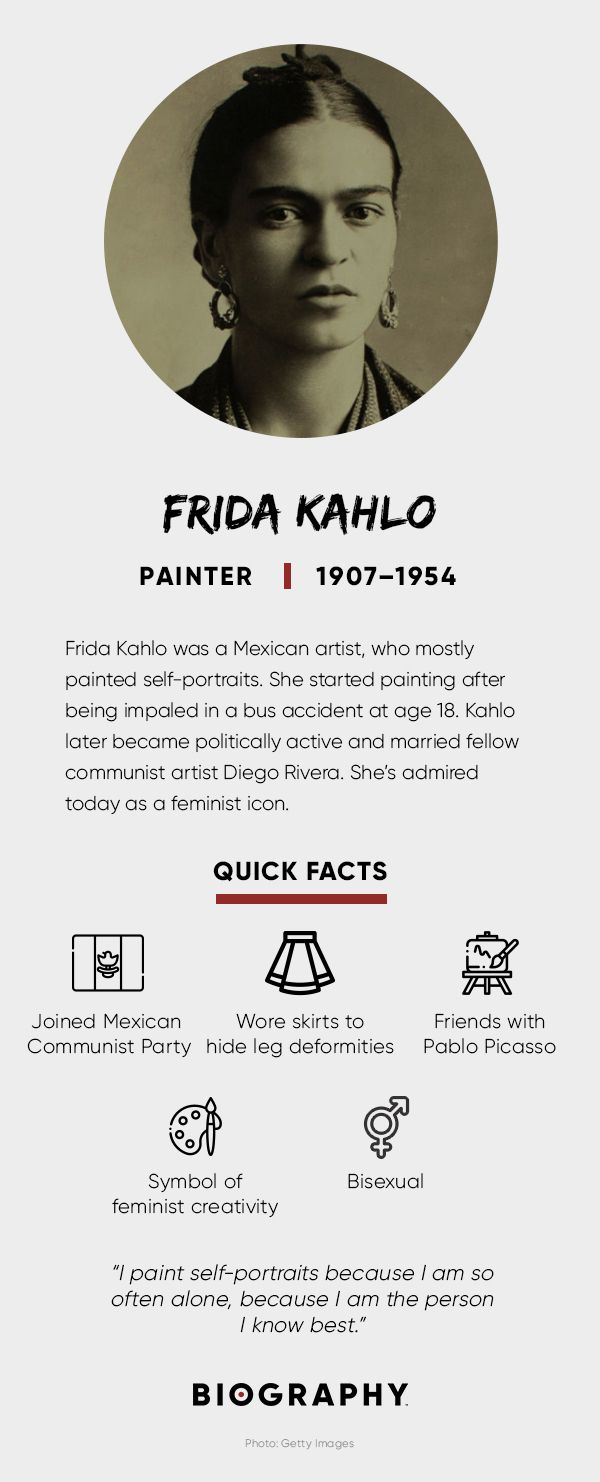

Frida Kahlo

Painter Frida Kahlo was a Mexican artist who was married to Diego Rivera and is still admired as a feminist icon.

(1907-1954)

Who Was Frida Kahlo?

Artist Frida Kahlo was considered one of Mexico's greatest artists who began painting mostly self-portraits after she was severely injured in a bus accident. Kahlo later became politically active and married fellow communist artist Diego Rivera in 1929. She exhibited her paintings in Paris and Mexico before her death in 1954.

Family, Education and Early Life

Kahlo was born Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Calderón on July 6, 1907, in Coyoacán, Mexico City, Mexico.

Kahlo's father, Wilhelm (also called Guillermo), was a German photographer who had immigrated to Mexico where he met and married her mother Matilde. She had two older sisters, Matilde and Adriana, and her younger sister, Cristina, was born the year after Kahlo.

Around the age of six, Kahlo contracted polio, which caused her to be bedridden for nine months. While she recovered from the illness, she limped when she walked because the disease had damaged her right leg and foot. Her father encouraged her to play soccer, go swimming, and even wrestle — highly unusual moves for a girl at the time — to help aid in her recovery.

In 1922, Kahlo enrolled at the renowned National Preparatory School. She was one of the few female students to attend the school, and she became known for her jovial spirit and her love of colorful, traditional clothes and jewelry.

While at school, Kahlo hung out with a group of politically and intellectually like-minded students. Becoming more politically active, Kahlo joined the Young Communist League and the Mexican Communist Party.

Frida Kahlo's Accident

After staying at the Red Cross Hospital in Mexico City for several weeks, Kahlo returned home to recuperate further. She began painting during her recovery and finished her first self-portrait the following year, which she gave to Gómez Arias.

Frida Kahlo's Marriage to Diego Rivera

In 1929, Kahlo and famed Mexican muralist Diego Rivera married. Kahlo and Rivera first met in 1922 when he went to work on a project at her high school. Kahlo often watched as Rivera created a mural called The Creation in the school’s lecture hall. According to some reports, she told a friend that she would someday have Rivera’s baby.

Kahlo reconnected with Rivera in 1928. He encouraged her artwork, and the two began a relationship. During their early years together, Kahlo often followed Rivera based on where the commissions that Rivera received were. In 1930, they lived in San Francisco, California. They then went to New York City for Rivera’s show at the Museum of Modern Art and later moved to Detroit for Rivera’s commission with the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Kahlo and Rivera’s time in New York City in 1933 was surrounded by controversy. Commissioned by Nelson Rockefeller , Rivera created a mural entitled Man at the Crossroads in the RCA Building at Rockefeller Center. Rockefeller halted the work on the project after Rivera included a portrait of communist leader Vladimir Lenin in the mural, which was later painted over. Months after this incident, the couple returned to Mexico and went to live in San Angel, Mexico.

Never a traditional union, Kahlo and Rivera kept separate, but adjoining homes and studios in San Angel. She was saddened by his many infidelities, including an affair with her sister Cristina. In response to this familial betrayal, Kahlo cut off most of her trademark long dark hair. Desperately wanting to have a child, she again experienced heartbreak when she miscarried in 1934.

Kahlo and Rivera went through periods of separation, but they joined together to help exiled Soviet communist Leon Trotsky and his wife Natalia in 1937. The Trotskys came to stay with them at the Blue House (Kahlo's childhood home) for a time in 1937 as Trotsky had received asylum in Mexico. Once a rival of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin , Trotsky feared that he would be assassinated by his old nemesis. Kahlo and Trotsky reportedly had a brief affair during this time.

Kahlo divorced Rivera in 1939. They did not stay divorced for long, remarrying in 1940. The couple continued to lead largely separate lives, both becoming involved with other people over the years .

Artistic Career

While she never considered herself a surrealist, Kahlo befriended one of the primary figures in that artistic and literary movement, Andre Breton, in 1938. That same year, she had a major exhibition at a New York City gallery, selling about half of the 25 paintings shown there. Kahlo also received two commissions, including one from famed magazine editor Clare Boothe Luce, as a result of the show.

In 1939, Kahlo went to live in Paris for a time. There she exhibited some of her paintings and developed friendships with such artists as Marcel Duchamp and Pablo Picasso .

Kahlo received a commission from the Mexican government for five portraits of important Mexican women in 1941, but she was unable to finish the project. She lost her beloved father that year and continued to suffer from chronic health problems. Despite her personal challenges, her work continued to grow in popularity and was included in numerous group shows around this time.

In 1953, Kahlo received her first solo exhibition in Mexico. While bedridden at the time, Kahlo did not miss out on the exhibition’s opening. Arriving by ambulance, Kahlo spent the evening talking and celebrating with the event’s attendees from the comfort of a four-poster bed set up in the gallery just for her.

After Kahlo’s death, the feminist movement of the 1970s led to renewed interest in her life and work, as Kahlo was viewed by many as an icon of female creativity.

Frida Kahlo's Most Famous Paintings

Many of Kahlo’s works were self-portraits. A few of her most notable paintings include:

'Frieda and Diego Rivera' (1931)

Kahlo showed this painting at the Sixth Annual Exhibition of the San Francisco Society of Women Artists, the city where she was living with Rivera at the time. In the work, painted two years after the couple married, Kahlo lightly holds Rivera’s hand as he grasps a palette and paintbrushes with the other — a stiffly formal pose hinting at the couple’s future tumultuous relationship. The work now lives at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

'Henry Ford Hospital' (1932)

In 1932, Kahlo incorporated graphic and surrealistic elements in her work. In this painting, a naked Kahlo appears on a hospital bed with several items — a fetus, a snail, a flower, a pelvis and others — floating around her and connected to her by red, veinlike strings. As with her earlier self-portraits, the work was deeply personal, telling the story of her second miscarriage.

'The Suicide of Dorothy Hale' (1939)

Kahlo was asked to paint a portrait of Luce and Kahlo's mutual friend, actress Dorothy Hale, who had committed suicide earlier that year by jumping from a high-rise building. The painting was intended as a gift for Hale's grieving mother. Rather than a traditional portrait, however, Kahlo painted the story of Hale's tragic leap. While the work has been heralded by critics, its patron was horrified at the finished painting.

'The Two Fridas' (1939)

One of Kahlo’s most famous works, the painting shows two versions of the artist sitting side by side, with both of their hearts exposed. One Frida is dressed nearly all in white and has a damaged heart and spots of blood on her clothing. The other wears bold colored clothing and has an intact heart. These figures are believed to represent “unloved” and “loved” versions of Kahlo.

'The Broken Column' (1944)

Kahlo shared her physical challenges through her art again with this painting, which depicted a nearly nude Kahlo split down the middle, revealing her spine as a shattered decorative column. She also wears a surgical brace and her skin is studded with tacks or nails. Around this time, Kahlo had several surgeries and wore special corsets to try to fix her back. She would continue to seek a variety of treatments for her chronic physical pain with little success.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S FRIDA KAHLO FACT CARD

Frida Kahlo’s Death

About a week after her 47th birthday, Kahlo died on July 13, 1954, at her beloved Blue House. There has been some speculation regarding the nature of her death. It was reported to be caused by a pulmonary embolism, but there have also been stories about a possible suicide.

Kahlo’s health issues became nearly all-consuming in 1950. After being diagnosed with gangrene in her right foot, Kahlo spent nine months in the hospital and had several operations during this time. She continued to paint and support political causes despite having limited mobility. In 1953, part of Kahlo’s right leg was amputated to stop the spread of gangrene.

Deeply depressed, Kahlo was hospitalized again in April 1954 because of poor health, or, as some reports indicated, a suicide attempt. She returned to the hospital two months later with bronchial pneumonia. No matter her physical condition, Kahlo did not let that stand in the way of her political activism. Her final public appearance was a demonstration against the U.S.-backed overthrow of President Jacobo Arbenz of Guatemala on July 2nd.

Movie on Frida Kahlo

Kahlo’s life was the subject of a 2002 film entitled Frida , starring Salma Hayek as the artist and Alfred Molina as Rivera. Directed by Julie Taymor, the film was nominated for six Academy Awards and won for Best Makeup and Original Score.

Frida Kahlo Museum

The family home where Kahlo was born and grew up, later referred to as the Blue House or Casa Azul, was opened as a museum in 1958. Located in Coyoacán, Mexico City, the Museo Frida Kahlo houses artifacts from the artist along with important works including Viva la Vida (1954), Frida and Caesarean (1931) and Portrait of my father Wilhelm Kahlo (1952).

Book on Frida Kahlo

Hayden Herrera’s 1983 book on Kahlo, Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo , helped to stir up interest in the artist. The biographical work covers Kahlo’s childhood, accident, artistic career, marriage to Diego Rivera, association with the communist party and love affairs.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Frida Kahlo

- Birth Year: 1907

- Birth date: July 6, 1907

- Birth City: Mexico City

- Birth Country: Mexico

- Gender: Female

- Best Known For: Painter Frida Kahlo was a Mexican artist who was married to Diego Rivera and is still admired as a feminist icon.

- Astrological Sign: Cancer

- National Preparatory School

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- Frida Kahlo met Diego Rivera when he was commissioned to paint a mural at her high school.

- Kahlo dealt with chronic pain most of her life due to a bus accident.

- Death Year: 1954

- Death date: July 13, 1954

- Death City: Mexico City

- Death Country: Mexico

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Frida Kahlo Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/artists/frida-kahlo

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: November 19, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- I never paint dreams or nightmares. I paint my own reality.

- My painting carries with it the message of pain.

- I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.

- I think that, little by little, I'll be able to solve my problems and survive.

- The only thing I know is that I paint because I need to, and I paint whatever passes through my head without any other consideration.

- I was born a bitch. I was born a painter.

- I love you more than my own skin.

- I am not sick, I am broken, but I am happy as long as I can paint.

- Feet, what do I need you for when I have wings to fly?

- I tried to drown my sorrows, but the bastards learned how to swim, and now I am overwhelmed with this decent and good feeling.

- There have been two great accidents in my life. One was the trolley and the other was Diego. Diego was by far the worst.

- I hope the end is joyful, and I hope never to return.

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Famous Painters

11 Notable Artists from the Harlem Renaissance

Fernando Botero

Gustav Klimt

The Surreal Romance of Salvador and Gala Dalí

Salvador Dalí

Margaret Keane

Andy Warhol

Advertisement

Supported by

Frida Kahlo in ‘Gringolandia’

- Share full article

- Apple Books

- Barnes and Noble

- Books-A-Million

When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission.

By Carolyn Burke

- March 3, 2020

FRIDA IN AMERICA The Creative Awakening of a Great Artist By Celia Stahr

It’s said that Frida Kahlo’s status in popular culture resembles a cross between a cult and a brand. At a time when oven mitts stamped with her likeness are found in museum gift shops, and her prosthetic leg is displayed like a saint’s relic in exhibitions , it’s hard to imagine Kahlo as an unknown artist at the start of her career. During the Depression, when she began to invent the flamboyant forms of identification with the Indigenous Mexicanidad for which she became famous, one could not have foreseen the current extent of Fridamania — our fascination with her carefully constructed personal mythos. (At some point she even changed her birth date from 1907 to 1910, the start of the Mexican Revolution, and elided the “e” in “Frieda” to make her name more authentically Mexican.)

It’s intriguing to encounter an artist in the act of becoming herself, and in “Frida in America,” Celia Stahr aims to do just that, returning us to Kahlo’s early days in San Francisco, New York and Detroit in the 1930s, when she and her husband, the artist Diego Rivera, were newlyweds. While Rivera was absorbed in painting large-scale social realist tableaus, Kahlo began fashioning modes of self-presentation in implicit opposition to the capitalist values of their host country , then painting canvases in the same style, marking major steps in her “creative awakening.”

Stahr, who teaches art history at the University of San Francisco, bases her narrative on the diary of Lucienne Bloch, a woman who became Kahlo’s confidante in the United States, as well as on correspondence between Kahlo and her family back in Mexico, beginning her book with the artist’s arrival with Rivera in San Francisco in 1930. There, Frida came to see her mixed heritage (she had a German father and a Mexican mother) as a source of distinction and started to develop the image of the mestiza in her appearance and work as an icon of Mexican national identity.

She did this first in her dress, emphasizing her “outsider status” to distinguish herself from Americans, who incurred her ongoing hostility. (Letters to her mother made an exception for San Francisco’s Chinese: They too were outsiders, their costumes and festivities “ simpáticos .”) In a work from this period, “Portrait of Eva Frederick,” Kahlo painted her African-American subject as both “an independent ‘New Woman’” and a “New Negro,” Stahr writes. Moreover, she had Frederick dress in a “Mexican-looking” garment, suggesting that Kahlo saw something of herself in her model.

Her 1931 canvas “Frieda and Diego Rivera,” often called a wedding portrait, depicts the artist as a diminutive but proud campesina — “a nationalist image,” Stahr notes, intended for an American audience — next to her imposingly large husband. Presenting herself in her painting as the wife of a famous artist, the 23-year-old Kahlo had begun confronting head-on “the complexity of being a stranger in a strange land.”

The complexities of the Riveras’ relations with America intensified when they moved to New York, where the Museum of Modern Art wanted to host a retrospective of Diego’s work. The contrast between the high society with whom they often socialized and the ordinary citizens suffering the effects of the Depression shocked Frida. She complained in a letter to her mother of “the horrible poverty here and the millions of people who have no work, food or home,” adding, of Diego, “Unfortunately, he has to work for these filthy rich asses.”

In New York, the couple were lionized by artists and photographers. As Imogen Cunningham and Edward Weston had done in San Francisco, Carl Van Vechten photographed Frida in Tehuana garb, depicting her with a touch of the “noble savage.” She played an important part in these sessions through her choice of costumes: “Whether they involved men’s clothing or the Indigenous styles of Mexico, she was bringing out an aspect of her complicated self.”

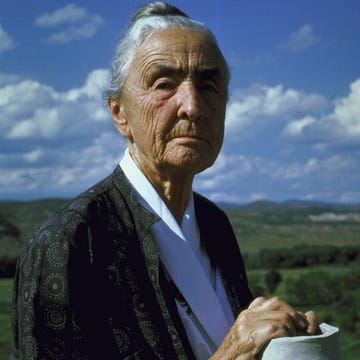

Stahr addresses Kahlo’s bisexuality in a speculative account of her acquaintance with Georgia O’Keeffe. Rivera watched with amusement as Kahlo flirted with O’Keeffe in the presence of her photographer husband, Alfred Stieglitz, then the most influential gallerist in New York. Kahlo boasted that she had done more than flirt with O’Keeffe — at the time perhaps the most successful American woman artist, and for this reason, Stahr argues, a role model. But while Kahlo clearly desired O’Keeffe’s support, there is little evidence to suggest that O’Keeffe responded to her flattery.

Stahr asserts that Kahlo’s infatuation “spilled over into a creative confluence, as the younger, more inexperienced Frida took on subjects that the older and more established Georgia had boldly painted.” This hypothesis prompts her to interpret one of Kahlo’s New York drawings as “a peek into her private dreams and desires” — discerning in it a profile of O’Keeffe, an interpretive gambit that seems far-fetched.

The Riveras’ New York visit concluded in 1932 with their move to Detroit, where Diego had been commissioned to paint another large-scale mural. Interviewed by a reporter, Frida declared that she too was an artist, “the greatest in the world.” (The reporter allowed, “She does paint with great charm.”) From then on, she asserted her originality while adopting a wry stance as the genius’s wife, a situation further complicated by a pregnancy.

The self-portraits Kahlo produced in Detroit dramatize her unflinching response to the miscarriage that ensued after a period of doubt about her fitness for motherhood. Looking at “Henry Ford Hospital (Flying Bed),” a portrait of the artist lying naked in her own blood, Stahr writes, “viewers, particularly those steeped in the Catholic imagery of a crucified Christ,” would have known that Kahlo “was referencing this image of suffering” in her disquieting version of a retablo painting, set against a frieze of Detroit’s factories. This canvas was followed by similar portraits, including a provocative image of a woman giving birth — titled “My Birth,” it is now owned by Madonna — painted after the death of Kahlo’s mother.

Stahr suggests that Kahlo’s raw, unrelenting vision during this period culminated in her “Self-Portrait on the Borderline Between Mexico and the United States” (1932), a faux-naïf portrait of the artist dressed in traditional garb and holding a Mexican flag. With this image, Kahlo positioned herself in a symbolic landscape — a Ford factory on one side, Mexican ruins on the other — that is also a confrontational perspective on the American scene. She left Detroit in 1933 confident that she was an artist in her own right, having found her subject matter in her ambivalent reactions to the United States.

Stahr intersperses chapters on Kahlo’s years in the three American cities with flashbacks to her childhood and accounts of trips to Mexico and of her return to New York in 1933, emboldened by the creation of what Stahr considers her best work. That year, “she left Gringolandia a different person than when she’d arrived. … It was the place where her creative spirit broke through to new heights.” From then on, Kahlo would turn her uncompromising gaze on a number of subjects, chiefly herself but also us, as we stare, riveted by her wild, brave aesthetic performances.

Stahr’s chronicle of Kahlo’s breakthrough includes vivid descriptions of the scenes that inspired her, along with many pages in which the narrative is suspended while she details her subject’s use of Mexican motifs, fantastic imagery and arcane formulas. Comparisons of Kahlo’s suffering to that of John the Baptist or Jesus may strike those other than Frida fans as something of a reach. For the broader dimensions of her traumatic life and fierce courage, readers might turn to Hayden Herrera’s 1983 biography, “Frida,” published before Fridamania attained its current frenzy — a phenomenon owing in no small part to her art’s congruence with current ideas about gender politics and cultural identity.

Carolyn Burke’s latest book, “Foursome: Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe, Paul Strand, Rebecca Salsbury,” was published in 2019.

FRIDA IN AMERICA The Creative Awakening of a Great Artist By Celia Stahr Illustrated. 383 pp. St. Martin’s Press. $29.99.

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

Stephen King, who has dominated horror fiction for decades , published his first novel, “Carrie,” in 1974. Margaret Atwood explains the book’s enduring appeal .

The actress Rebel Wilson, known for roles in the “Pitch Perfect” movies, gets vulnerable about her weight loss, sexuality and money in her new memoir.

“City in Ruins” is the third novel in Don Winslow’s Danny Ryan trilogy and, he says, his last book. He’s retiring in part to invest more time into political activism .

Jonathan Haidt, the social psychologist and author of “The Anxious Generation,” is “wildly optimistic” about Gen Z. Here’s why .

Do you want to be a better reader? Here’s some helpful advice to show you how to get the most out of your literary endeavor .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

- Arts & Photography

- History & Criticism

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: $24.99 $24.99 FREE delivery: Friday, April 12 on orders over $35.00 shipped by Amazon. Ships from: Amazon.com Sold by: Amazon.com

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Buy used: $15.97

Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) is a service we offer sellers that lets them store their products in Amazon's fulfillment centers, and we directly pack, ship, and provide customer service for these products. Something we hope you'll especially enjoy: FBA items qualify for FREE Shipping and Amazon Prime.

If you're a seller, Fulfillment by Amazon can help you grow your business. Learn more about the program.

Other Sellers on Amazon

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo Paperback – October 1, 2002

Purchase options and add-ons.

"Through her art, Herrera writes, Kahlo made of herself both performer and icon. Through this long overdue biography, Kahlo has also, finally, been made fully human." — San Francisco Chronicle

Hailed by readers and critics across the country, this engrossing biography of Mexican painter Frida Kahlo reveals a woman of extreme magnetism and originality, an artist whose sensual vibrancy came straight from her own experiences: her childhood near Mexico City during the Mexican Revolution; a devastating accident at age eighteen that left her crippled and unable to bear children; her tempestuous marriage to muralist Diego Rivera and intermittent love affairs with men as diverse as Isamu Noguchi and Leon Trotsky; her association with the Communist Party; her absorption in Mexican folklore and culture; and her dramatic love of spectacle.

Here is the tumultuous life of an extraordinary twentieth-century woman -- with illustrations as rich and haunting as her legend.

- Print length 528 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Harper Perennial

- Publication date October 1, 2002

- Dimensions 6.12 x 1.4 x 9.25 inches

- ISBN-10 0060085894

- ISBN-13 978-0060085896

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Similar items that may ship from close to you

Editorial Reviews

"A haunting, highly vivid biography." — Ms . magazine

From the Back Cover

About the author.

Hayden Herrera is an art historian. She has lectured widely, curated several exhibitions of art, taught Latin American art at New York University, and has been awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship. She is the author of numerous articles and reviews for such publications as Art in America, Art Forum, Connoisseur, and the New York Times, among others. Her books include Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo; Mary Frank; and Matisse: A Portrait. She is working on a critical biography of Arshile Gorky. She lives in New York City.

Product details

- Publisher : Harper Perennial (October 1, 2002)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 528 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0060085894

- ISBN-13 : 978-0060085896

- Item Weight : 1.43 pounds

- Dimensions : 6.12 x 1.4 x 9.25 inches

- #77 in Artist & Architect Biographies

- #120 in Arts & Photography Criticism

- #207 in Art History (Books)

About the author

Hayden herrera.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Start Selling with Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Movie Reviews

Tv/streaming, collections, great movies, chaz's journal, contributors.

Now streaming on:

Early in their marriage, Frida Kahlo tells Diego Rivera she expects him to be "not faithful, but loyal." She holds herself to the same standard. Sexual faithfulness is a bourgeois ideal that they reject as Marxist bohemians who disdain the conventional. But passionate jealousy is not unknown to them, and both have a double standard, permitting themselves freedoms they would deny the other. During the course of "Frida," Kahlo has affairs with Leon Trotsky and Josephine Baker (not a shabby dance card), and yet rages at Diego for his infidelities.

Julie Taymor 's biopic tells the story of an extraordinary life. Frida Kahlo ( Salma Hayek ), born of a German Jewish father and a Mexican mother, grew up in Mexico City at a time when it was a hotbed of exile and intrigue. As a student, she goes to see the great muralist Diego Rivera at work, boldly calls him "fat" and knows that he is the man for her.

Then she is almost mortally injured in a trolley crash that shatters her back and pierces her body with a steel rod. She was never to be free of pain again in her life and for long periods had to wear a body cast. Taymor shows a bluebird flying from Frida's hand at the moment of the crash, and later gold leaf falls on the cast: She uses the materials of magic realism to suggest how Frida was able to overcome pain with art and imagination.

Rivera was already a legend when she met him. Played by Alfred Molina in a great bearlike performance of male entitlement, he was equally gifted at art, carnal excess and self-promotion. The first time Frida sleeps with him, they are discovered by his wife, Lupe ( Valeria Golino ), who is enraged, of course, but such is Diego's power over women that after Frida and Diego are wed, Lupe brings them breakfast in bed ("This is his favorite. If you are here to stay, you'd better learn how to make it.") Frida's paintings often show herself, alone or with Diego, and reflect her pain and her ecstasy. They are on a smaller scale than his famous murals, and her art is overshadowed by his. His fame leads to an infamous incident, when he is hired by Nelson Rockefeller ( Edward Norton ) to create a mural for Rockefeller Center, and boldly includes Lenin among the figures he paints. Rockefeller commands the mural to be hammered down from the wall, thus making himself the goat in this episode forevermore.

The director, Julie Taymor, became famous for her production of " The Lion King " on Broadway, with its extraordinary merging of actors and the animals they portrayed. Her film " Titus " (1999) was a brilliant re-imaging of the Shakespeare tragedy, showing a gift for great daring visual inventions. Here, too, she breaks out of realism to suggest the fanciful colors of Frida's imagination. But real life itself is bizarre in this marriage, where the partners build houses side by side and connect them by a bridge between the top floors.

Artists talk about the "zone," that mental state when the mind, the eye, the hand and the imagination are all in the same place and they are able to lose track of time and linear thought. Frida Kahlo seems to have painted in order to seek the zone and escape pain: When she was at work, she didn't so much put the pain onto the canvas as channel it away from conscious thought and into the passion of her work. She needs to paint, not simply to "express herself" but to live at all, and this is her closest bond with Rivera.

Biopics of artists are always difficult, because the connections between life and art always seem too easy and facile. The best ones lead us back to the work itself and inspire us to sympathize with its maker. "Frida" is jammed with incident and anecdote--this was a life that ended at 46 and yet made longer lives seem underfurnished. Taymor obviously struggled with the material, as did her many writers; the screenwriters listed range from the veteran Clancy Sigal to the team of Gregory Nava and Anna Thomas , and much of the final draft was reportedly written by Norton. Sometimes we feel as if the film careens from one colorful event to another without respite, but sometimes it must have seemed to Frida Kahlo as if her life did, too.

The film opens in 1953, on the date of Frida's only one-woman show in Mexico. Her doctor tells her she is too sick to attend it, but she has her bed lifted into a flat-bed truck and carried to the gallery. This opening gesture provides Taymor with the set-up for the movie's extraordinary closing scenes, in which death itself is seen as another work of art.

Roger Ebert

Roger Ebert was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.

Now playing

Sleeping Dogs

Brian tallerico.

Carol Doda Topless at the Condor

Marya e. gates.

Mary & George

Cristina escobar.

Riddle of Fire

Robert daniels.

Steve! (Martin): A Documentary in Two Pieces

Christy Lemire

Film credits.

Frida (2002)

Rated R For Sexuality/Nudity and Language

120 minutes

Salma Hayek as Frida Kahlo

Alfred Molina as Diego Rivera

Geoffrey Rush as Leon Trotsky

Ashley Judd as Tina Modotti

Antonio Banderas as David Alfaro Siqueiros

Directed by

- Julie Taymor

- Gregory Nava

- Clancy Sigal

- Anna Thomas

Based on the book by

- Hayden Herrera

Latest blog posts

Criterion Celebrates the Films That Forever Shifted Our Perception of Kristen Stewart

The Estate of George Carlin Destroys AI George Carlin in Victory for Copyright Protection (and Basic Decency)

The Future of the Movies, Part 3: Fathom Events CEO Ray Nutt

11:11 - Eleven Reviews by Roger Ebert from 2011 in Remembrance of His Transition 11 Years Ago

ARTS & CULTURE

Frida kahlo.

The Mexican artist’s myriad faces, stranger-than-fiction biography and powerful paintings come to vivid life in a new film

Phyllis Tuchman

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9c/04/9c0461e2-407f-48e6-8293-bab6c7c5f353/frida_kahlo_by_guillermo_kahlo.jpg)

Frida Kahlo, who painted mostly small, intensely personal works for herself, family and friends, would likely have been amazed and amused to see what a vast audience her paintings now reach. Today, nearly 50 years after her death, the Mexican artist’s iconic images adorn calendars, greeting cards, posters, pins, even paper dolls. Several years ago the French couturier Jean Paul Gaultier created a collection inspired by Kahlo, and last year a self-portrait she painted in 1933 appeared on a 34-cent U.S. postage stamp. This month, the movie Frida, starring Salma Hayek as the artist and Alfred Molina as her husband, renowned muralist Diego Rivera, opens nationwide. Directed by Julie Taymor, the creative wizard behind Broadway’s long-running hit The Lion King , the film is based on Hayden Herrera’s 1983 biography, Frida. Artfully composed, Taymor’s graphic portrayal remains, for the most part, faithful to the facts of the painter’s life. Although some changes were made because of budget constraints, the movie “is true in spirit,” says Herrera, who was first drawn to Kahlo because of “that thing in her work that commands you—that urgency, that need to communicate.”

Focusing on Kahlo’s creativity and tumultuous love affair with Rivera, the film looks beyond the icon to the human being. “I was completely compelled by her story,” says Taymor. “I knew it superficially; and I admired her paintings but didn’t know them well. When she painted, it was for herself. She transcended her pain. Her paintings are her diary. When you’re doing a movie, you want a story like that.” In the film, the Mexican born and raised Hayek, 36, who was one of the film’s producers, strikes poses from the paintings, which then metamorphose into action-filled scenes. “Once I had the concept of having the paintings come alive,” says Taymor, “I wanted to do it.”

Kahlo, who died July 13, 1954, at the age of 47, reportedly of a pulmonary embolism (though some suspected suicide), has long been recognized as an important artist. In 2001-2002, a major traveling exhibition showcased her work alongside that of Georgia O’Keeffe and Canada’s Emily Carr. Earlier this year several of her paintings were included in a landmark Surrealism show in London and New York. Currently, works by both Kahlo and Rivera are on view through January 5, 2003, at the SeattleArt Museum. As Janet Landay, curator of exhibitions at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and one of the organizers of a 1993 exhibition of Kahlo’s work, points out, “Kahlo made personal women’s experiences serious subjects for art, but because of their intense emotional content, her paintings transcend gender boundaries. Intimate and powerful, they demand that viewers—men and women—be moved by them.”

Kahlo produced only about 200 paintings—primarily still lifes and portraits of herself, family and friends. She also kept an illustrated journal and did dozens of drawings. With techniques learned from both her husband and her father, a professional architectural photographer, she created haunting, sensual and stunningly original paintings that fused elements of surrealism, fantasy and folklore into powerful narratives. In contrast to the 20th-century trend toward abstract art, her work was uncompromisingly figurative. Although she received occasional commissions for portraits, she sold relatively few paintings during her lifetime. Today her works fetch astronomical prices at auction. In 2000, a 1929 self-portrait sold for more than $5 million.

Biographies of the artist, which have been translated into many languages, read like the fantastical novels of Gabriel García Márquez as they trace the story of two painters who could not live with or without each other. (Taymor says she views her film version of Kahlo’s life as a “great, great love story.”) Married twice, divorced once and separated countless times, Kahlo and Rivera had numerous affairs, hobnobbed with Communists, capitalists and literati and managed to create some of the most compelling visual images of the 20th century. Filled with such luminaries as writer André Breton, sculptor Isamu Noguchi, playwright Clare Boothe Luce and exiled Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky, Kahlo’s life played out on a phantasmagorical canvas.

She was born Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón July 6, 1907, and lived in a house (the Casa Azul, or Blue House, now the Museo Frida Kahlo) built by her father in Coyoacán, then a quiet suburb of Mexico City. The third of her parents’ four daughters, Frida was her father’s favorite—the most intelligent, he thought, and the most like himself. She was a dutiful child but had a fiery temperament. (Shortly before Kahlo and Rivera were wed in 1929, Kahlo’s father warned his future son-in-law, who at age 42 had already had two wives and many mistresses, that Frida, then 21, was “a devil.” Rivera replied: “I know it.”)

A German Jew with deep-set eyes and a bushy mustache, Guillermo Kahlo had immigrated to Mexico in 1891 at the age of 19. After his first wife died in childbirth, he married Matilde Calderón, a Catholic whose ancestry included Indians as well as a Spanish general. Frida portrayed her hybrid ethnicity in a 1936 painting, My Grandparents, My Parents, and I (opposite).

Kahlo adored her father. On a portrait she painted of him in 1951, she inscribed the words, “character generous, intelligent and fine.” Her feelings about her mother were more conflicted. On the one hand, the artist considered her “very nice, active, intelligent.” But she also saw her as fanatically religious, calculating and sometimes even cruel. “She did not know how to read or write,” recalled the artist. “She only knew how to count money.”

A chubby child with a winning smile and sparkling eyes, Kahlo was stricken with polio at the age of 6. After her recovery, her right leg remained thinner than her left and her right foot was stunted. Despite her disabilities or, perhaps, to compensate for them, Kahlo became a tomboy. She played soccer, boxed, wrestled and swam competitively. “My toys were those of a boy: skates, bicycles,” the artist later recalled. (As an adult, she collected dolls.)

Her father taught her photography, including how to retouch and color prints, and one of his friends gave her drawing lessons. In 1922, the 15-year-old Kahlo entered the elite, predominantly male NationalPreparatory School, which was located near the Cathedral in the heart of Mexico City.

As it happened, Rivera was working in the school’s auditorium on his first mural. In his autobiography— My Art, My Life —the artist recalled that he was painting one night high on a scaffold when “all of a sudden the door flew open, and a girl who seemed to be no more than ten or twelve was propelled inside. . . . She had,” he continued, “unusual dignity and self-assurance, and there was a strange fire in her eyes.” Kahlo, who was actually 16, apparently played pranks on the artist. She stole his lunch and soaped the steps by the stage where he was working.

Kahlo planned to become a doctor and took courses in biology, zoology and anatomy. Her knowledge of these disciplines would later add realistic touches to her portraits. She also had a passion for philosophy, which she liked to flaunt. According to biographer Herrera, she would cry out to her boyfriend, Alejandro Gómez Arias, “lend me your Spengler. I don’t have anything to read on the bus.” Her bawdy sense of humor and passion for fun were well known among her circle of friends, many of whom would become leaders of the Mexican left.

Then, on September 17, 1925, the bus on which she and her boyfriend were riding home from school was rammed by a trolley car. A metal handrail broke off and pierced her pelvis. Several people died at the site, and doctors at the hospital where the 18-year-old Kahlo was taken did not think she would survive. Her spine was fractured in three places, her pelvis was crushed and her right leg and foot were severely broken. The first of many operations she would endure over the years brought only temporary relief from pain. “In this hospital,” Kahlo told Gómez Arias, “death dances around my bed at night.” She spent a month in the hospital and was later fitted with a plaster corset, variations of which she would be compelled to wear throughout her life.

Confined to bed for three months, she was unable to return to school. “Without giving it any particular thought,” she recalled, “I started painting.” Kahlo’s mother ordered a portable easel and attached a mirror to the underside of her bed’s canopy so that the nascent artist could be her own model.

Though she knew the works of the old masters only from reproductions, Kahlo had an uncanny ability to incorporate elements of their styles in her work. In a painting she gave to Gómez Arias, for instance, she portrayed herself with a swan neck and tapered fingers, referring to it as “Your Botticeli.”

During her months in bed, she pondered her changed circumstances. To Gómez Arias, she wrote, “Life will reveal [its secrets] to you soon. I already know it all. . . . I was a child who went about in a world of colors. . . . My friends, my companions became women slowly, I became old in instants.”

As she grew stronger, Kahlo began to participate in the politics of the day, which focused on achieving autonomy for the government-run university and a more democratic national government. She joined the Communist party in part because of her friendship with the young Italian photographer Tina Modotti, who had come to Mexico in 1923 with her then companion, photographer Edward Weston. It was most likely at a soiree given by Modotti in late 1928 that Kahlo re-met Rivera.

They were an unlikely pair. The most celebrated artist in Mexico and a dedicated Communist, the charismatic Rivera was more than six feet tall and tipped the scales at 300 pounds. Kahlo, 21 years his junior, weighed 98 pounds and was 5 feet 3 inches tall. He was ungainly and a bit misshapen; she was heart-stoppingly alluring. According to Herrera, Kahlo “started with dramatic material: nearly beautiful, she had slight flaws that increased her magnetism.” Rivera described her “fine nervous body, topped by a delicate face,” and compared her thick eyebrows, which met above her nose, to “the wings of a blackbird, their black arches framing two extraordinary brown eyes.”

Rivera courted Kahlo under the watchful eyes of her parents. Sundays he visited the Casa Azul, ostensibly to critique her paintings. “It was obvious to me,” he later wrote, “that this girl was an authentic artist.” Their friends had reservations about the relationship. One Kahlo pal called Rivera “a pot-bellied, filthy old man.” But Lupe Marín, Rivera’s second wife, marveled at how Kahlo, “this so-called youngster,” drank tequila “like a real mariachi.”

The couple married on August 21, 1929. Kahlo later said her parents described the union as a “marriage between an elephant and a dove.” Kahlo’s 1931 Colonial-style portrait, based on a wedding photograph, captures the contrast. The newlyweds spent almost a year in Cuernavaca while Rivera executed murals commissioned by the American ambassador to Mexico, Dwight Morrow. Kahlo was a devoted wife, bringing Rivera lunch every day, bathing him, cooking for him. Years later Kahlo would paint a naked Rivera resting on her lap as if he were a baby.

With the help of Albert Bender, an American art collector, Rivera obtained a visa to the United States, which previously had been denied him. Since Kahlo had resigned from the Communist party when Rivera, under siege from the Stalinists, was expelled, she was able to accompany him. Like other left-wing Mexican intellectuals, she was now dressing in flamboyant native Mexican costume—embroidered tops and colorful, floor-length skirts, a style associated with the matriarchal society of the region of Tehuantepec. Rivera’s new wife was “a little doll alongside Diego,” Edward Weston wrote in his journal in 1930. “People stop in their tracks to look in wonder.”

The Riveras arrived in the United States in November 1930, settling in San Francisco while Rivera worked on murals for the San Francisco Stock Exchange and the California School of Fine Arts, and Kahlo painted portraits of friends. After a brief stay in New York City for a show of Rivera’s work at the Museum of Modern Art, the couple moved on to Detroit, where Rivera filled the Institute of Arts’ garden court with compelling industrial scenes, and then back to New York City, where he worked on a mural for Rockefeller Center. They stayed in the United States for three years. Diego felt he was living in the future; Frida grew homesick. “I find that Americans completely lack sensibility and good taste,” she observed. “They are boring and they all have faces like unbaked rolls.”

In Manhattan, however, Kahlo was exhilarated by the opportunity to see the works of the old masters firsthand. She also enjoyed going to the movies, especially those starring the Marx Brothers or Laurel and Hardy. And at openings and dinners, she and Rivera met the rich and the renowned.

But for Kahlo, despair and pain were never far away. Before leaving Mexico, she had suffered the first in a series of miscarriages and therapeutic abortions. Due to her trolley-car injuries, she seemed unable to bring a child to term, and every time she lost a baby, she was thrown into a deep depression. Moreover, her polio-afflicted and badly injured right leg and foot often troubled her. While in Michigan, a miscarriage cut another pregnancy short. Then her mother died. Up to that time she had persevered. “I am more or less happy,” she had written to her doctor, “because I have Diego and my mother and my father whom I love so much. I think that is enough. . . . ” Now her world was starting to fall apart.

Kahlo had arrived in America an amateur artist. She had never attended art school, had no studio and had not yet focused on any particular subject matter. “I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best,” she would say years later. Her biographers report that despite her injuries she regularly visited the scaffolding on which Rivera worked in order to bring him lunch and, they speculate, to ward off alluring models. As she watched him paint, she learned the fundamentals of her craft. His imagery recurs in her pictures along with his palette—the sunbaked colors of pre- Columbian art. And from him—though his large-scale wall murals depict historical themes, and her small-scale works relate her autobiography—she learned how to tell a story in paint.

Works from her American period reveal her growing narrative skill. In Self-Portrait on the Borderline betweenMexico and the United States, Kahlo’s homesickness finds expression in an image of herself standing between a pre-Columbian ruin and native flowers on one side and Ford Motor Company smokestacks and looming skyscrapers on the other. In HenryFordHospital, done soon after her miscarriage in Detroit, Kahlo’s signature style starts to emerge. Her desolation and pain are graphically conveyed in this powerful depiction of herself, nude and weeping, on a bloodstained bed. As she would do time and again, she exorcises a devastating experience through the act of painting.

When they returned to Mexico toward the end of 1933, both Kahlo and Rivera were depressed. His RockefellerCenter mural had created a controversy when the owners of the project objected to the heroic portrait of Lenin he had included in it. When Rivera refused to paint out the portrait, the owners had the mural destroyed. (Rivera later re-created a copy for the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City.) To a friend Kahlo wrote, Diego “thinks that everything that is happening to him is my fault, because I made him come [back] to Mexico. . . . ” Kahlo herself became physically ill, as she was prone to do in times of stress. Whenever Rivera, a notorious philanderer, became involved with other women, Kahlo succumbed to chronic pain, illness or depression. When he returned home from his wanderings, she would usually recover.

Seeking a fresh start, the Riveras moved into a new home in the upscale San Angel district of Mexico City. The house, now the Diego Rivera Studio museum, featured his-and-her, brightly colored (his was pink, hers, blue) Le Corbusier-like buildings connected by a narrow bridge. Though the plans included a studio for Kahlo, she did little painting, as she was hospitalized three times in 1934. When Rivera began an affair with her younger sister, Cristina, Kahlo moved into an apartment. A few months later, however, after a brief dalliance with the sculptor Isamu Noguchi, Kahlo reconciled with Rivera and returned to San Angel.

In late 1936, Rivera, whose leftist sympathies were more pronounced than ever, interceded with Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas to have the exiled Leon Trotsky admitted to Mexico. In January 1937, the Russian revolutionary took up a two-year residency with his wife and bodyguards at the Casa Azul, Kahlo’s childhood home, available because Kahlo’s father had moved in with one of her sisters. In a matter of months, Trotsky and Kahlo became lovers. “El viejo” (“the old man”), as she called him, would slip her notes in books. She painted a mesmerizing fulllength portrait of herself (far right), in bourgeois finery, as a gift for the Russian exile. But this liaison, like most of her others, was short lived.

The French Surrealist André Breton and his wife, Jacqueline Lamba, also spent time with the Riveras in San Angel. (Breton would later offer to hold an exhibition of Kahlo’s work in Paris.) Arriving in Mexico in the spring of 1938, they stayed for several months and joined the Riveras and the Trotskys on sight-seeing jaunts. The three couples even considered publishing a book of their conversations. This time, it was Frida and Jacqueline who bonded.

Although Kahlo would claim her art expressed her solitude, she was unusually productive during the time spent with the Trotskys and the Bretons. Her imagery became more varied and her technical skills improved. In the summer of 1938, the actor and art collector Edward G. Robinson visited the Riveras in San Angel and paid $200 each for four of Kahlo’s pictures, among the first she sold. Of Robinson’s purchase she later wrote, “For me it was such a surprise that I marveled and said: ‘This way I am going to be able to be free, I’ll be able to travel and do what I want without asking Diego for money.’”

Shortly after, Kahlo went to New York City for her first one-person show, held at the Julien Levy Gallery, one of the first venues in America to promote Surrealist art. In a brochure for the exhibition, Breton praised Kahlo’s “mixture of candour and insolence.” On the guest list for the opening were artist Georgia O’Keeffe, to whom Kahlo later wrote a fan letter, art historian Meyer Schapiro and Vanity Fair editor Clare Boothe Luce, who commissioned Kahlo to paint a portrait of a friend who had committed suicide. Upset by the graphic nature of Kahlo’s completed painting, however, Luce wanted to destroy it but in the end was persuaded not to. The show was a critical success. Time magazine noted that “the flutter of the week in Manhattan was caused by the first exhibition of paintings by famed muralist Diego Rivera’s . . . wife, Frida Kahlo. . . . Frida’s pictures, mostly painted in oil on copper, had the daintiness of miniatures, the vivid reds and yellows of Mexican tradition, the playfully bloody fancy of an unsentimental child.” A little later, Kahlo’s hand, bedecked with rings, appeared on the cover of Vogue .

Heady with success, Kahlo sailed to France, only to discover that Breton had done nothing about the promised show. A disappointed Kahlo wrote to her latest lover, portrait photographer Nickolas Muray: “It was worthwhile to come here only to see why Europe is rottening, why all this people—good for nothing—are the cause of all the Hitlers and Mussolinis.” Marcel Duchamp— “The only one,” as Kahlo put it, “who has his feet on the earth, among all this bunch of coocoo lunatic sons of bitches of the Surrealists”—saved the day. He got Kahlo her show. The Louvre purchased a self-portrait, its first work by a 20th-century Mexican artist. At the exhibition, according to Rivera, artist Wassily Kandinsky kissed Kahlo’s cheeks “while tears of sheer emotion ran down his face.” Also an admirer, Pablo Picasso gave Kahlo a pair of earrings shaped like hands, which she donned for a later self-portrait. “Neither Derain, nor I, nor you,” Picasso wrote to Rivera, “are capable of painting a head like those of Frida Kahlo.”

Returning to Mexico after six months abroad, Kahlo found Rivera entangled with yet another woman and moved out of their San Angel house and into the Casa Azul. By the end of 1939 the couple had agreed to divorce.

Intent on achieving financial independence, Kahlo painted more intensely than ever before. “To paint is the most terrific thing that there is, but to do it well is very difficult,” she would tell the group of students—known as Los Fridos—to whom she gave instruction in the mid-1940s. “It is necessary . . . to learn the skill very well, to have very strict self-discipline and above all to have love, to feel a great love for painting.” It was during this period that Kahlo created some of her most enduring and distinctive work. In self-portraits, she pictured herself in native Mexican dress with her hair atop her head in traditional braids. Surrounded by pet monkeys, cats and parrots amid exotic vegetation reminiscent of the paintings of Henri Rousseau, she often wore the large pre-Columbian necklaces given to her by Rivera.

In one of only two large canvases ever painted by Kahlo, The Two Fridas, a double self-portrait done at the time of her divorce, one Frida wears a European outfit torn open to reveal a “broken” heart; the other is clad in native Mexican costume. Set against a stormy sky, the “twin sisters,” joined together by a single artery running from one heart to the other, hold hands. Kahlo later wrote that the painting was inspired by her memory of an imaginary childhood friend, but the fact that Rivera himself had been born a twin may also have been a factor in its composition. In another work from this period, Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair (1940), Kahlo, in a man’s suit, holds a pair of scissors she has used to sever the locks that surround the chair on which she sits. More than once when she discovered Rivera with other women, she had cut off the long hair that he adored.

Despite the divorce, Kahlo and Rivera remained connected. When Kahlo’s health deteriorated, Rivera sought medical advice from a mutual friend, San Francisco doctor Leo Eloesser, who felt her problem was “a crisis of nerves.” Eloesser suggested she resolve her relationship with Rivera. “Diego loves you very much,” he wrote, “and you love him. It is also the case, and you know it better than I, that besides you, he has two great loves—1) Painting 2) Women in general. He has never been, nor ever will be, monogamous.” Kahlo apparently recognized the truth of this observation and resigned herself to the situation. In December 1940, the couple remarried in San Francisco.

The reconciliation, however, saw no diminution in tumult. Kahlo continued to fight with her philandering husband and sought out affairs of her own with various men and women, including several of his lovers. Still, Kahlo never tired of setting a beautiful table, cooking elaborate meals (her stepdaughter Guadalupe Rivera filled a cookbook with Kahlo’s recipes) and arranging flowers in her home from her beloved garden. And there were always festive occasions to celebrate. At these meals, recalled Guadalupe, “Frida’s laughter was loud enough to rise above the din of yelling and revolutionary songs.”

During the last decade of her life, Kahlo endured painful operations on her back, her foot and her leg. (In 1953, her right leg had to be amputated below the knee.) She drank heavily—sometimes downing two bottles of cognac a day—and she became addicted to painkillers. As drugs took control of her hands, the surface of her paintings became rough, her brushwork agitated.

In the spring of 1953, Kahlo finally had a one-person show in Mexico City. Her work had previously been seen there only in group shows. Organized by her friend, photographer Lola Alvarez Bravo, the exhibition was held at Alvarez Bravo’s Gallery of Contemporary Art. Though still bedridden following the surgery on her leg, Kahlo did not want to miss the opening night. Arriving by ambulance, she was carried to a canopied bed, which had been transported from her home. The headboard was decorated with pictures of family and friends; papier-mâché skeletons hung from the canopy. Surrounded by admirers, the elaborately costumed Kahlo held court and joined in singing her favorite Mexican ballads.

Kahlo remained a dedicated leftist. Even as her strength ebbed, she painted portraits of Marx and of Stalin and attended demonstrations. Eight days before she died, Kahlo, in a wheelchair and accompanied by Rivera, joined a crowd of 10,000 in Mexico City protesting the overthrow, by the CIA, of the Guatemalan president.

Although much of Kahlo’s life was dominated by her debilitated physical state and emotional turmoil, Taymor’s film focuses on the artist’s inventiveness, delight in beautiful things and playful but caustic sense of humor. Kahlo, too, preferred to emphasize her love of life and a good time. Just days before her death, she incorporated the words Viva La Vida (Long Live Life) into a still life of watermelons. Though some have wondered whether the artist may have intentionally taken her own life, others dismiss the notion. Certainly, she enjoyed life fully and passionately. “It is not worthwhile,” she once said, “to leave this world without having had a little fun in life.”

Get the latest Travel & Culture stories in your inbox.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up review – forget the paintings, here's her false leg

V&A, London By focusing on Kahlo’s life and her suffering rather than her art, this memorabilia-stuffed exhibition stifles her blazing visionary brilliance