- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

5 (page 91) p. 91 Colonialism in Africa

- Published: March 2007

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The period of colonial rule in Africa came late and did not last very long. Africa was conquered by European imperial powers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By the 1960s, it was mostly over. ‘Colonialism in Africa’ considers how this period shaped African history. For some Africans, colonial rule was threatening; for others, an opportunity. Reconstructing the complicated patterns of this time is a massive challenge for historians of Africa. Interest in Africa' colonial past has waxed and waned, and resurged recently. Colonialism was not just about the actions of the Europeans, it was also about the actions of the Africans and what they thought.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Colonialism in Africa: a Historical Overview

This essay about the legacy of colonialism in Africa provides a historical overview of how European colonization has profoundly shaped the continent’s political, economic, and social landscapes. It discusses how arbitrary borders imposed during colonial rule have led to enduring political instability and internal conflicts. Additionally, it examines the economic impact of colonialism, highlighting how extractive practices have hindered economic development and perpetuated poverty. Furthermore, the essay explores the social repercussions of colonialism, including the marginalization of indigenous cultures and languages. It concludes by emphasizing the ongoing challenges faced by African nations in addressing the legacy of colonialism and building inclusive and sustainable societies for the future.

How it works

The colonization of Africa, a process that unfolded over centuries, has left an indelible mark on the continent, shaping its political, social, and economic landscapes in profound ways. The scramble for Africa, reaching its zenith during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, saw European powers carving up the continent with little regard for indigenous cultures or historical divisions. This essay explores the multifaceted impacts of colonialism on Africa, examining its legacy through the lenses of political borders, economic structures, and social transformations.

Colonial powers imposed artificial borders that disregarded ethnic and cultural lines, leading to enduring political instability in post-colonial states. These arbitrary divisions often grouped disparate communities together or split cohesive ones apart, laying the groundwork for future conflicts. The legacy of these borders is still evident today, as many African nations grapple with internal divisions and regional disputes that trace back to colonial-era map-making.

Economically, colonialism restructured Africa’s economies to serve European interests, primarily focusing on the extraction of resources. This extractivist approach hindered the development of diversified economies, making post-colonial nations heavily dependent on a limited range of exports. Moreover, the infrastructure established during the colonial period was primarily designed to facilitate the removal of resources, rather than to support intracontinental trade or development. This economic legacy has contributed to persistent poverty and underdevelopment in many African countries.

Socially, colonialism had a profound impact on African societies, disrupting traditional structures and identities. European colonial powers often imposed their own cultures and languages, marginalizing indigenous practices and languages. This cultural imperialism not only eroded traditional African identities but also instilled a sense of inferiority that has been difficult to overcome. However, it also led to the formation of new identities and resistance movements that played crucial roles in the eventual decolonization process.

The struggle for independence across Africa, while a testament to the resilience and determination of its people, was often marked by violence and upheaval. The transition from colonial rule to sovereignty was fraught with challenges, as newly independent nations sought to navigate the complex legacy of colonialism. The post-colonial period has been characterized by efforts to redefine national identities, build cohesive states, and develop economies that can sustainably support their populations.

In conclusion, the colonization of Africa has had far-reaching effects that continue to influence the continent today. The political, economic, and social legacies of colonialism are intertwined, contributing to the complex challenges that African nations face in the 21st century. While the scars of colonialism are deeply etched into Africa’s history, the continent’s future will be defined by its own people. Efforts to address the lingering effects of colonialism, build inclusive societies, and forge sustainable development paths are crucial for Africa’s progress. The legacy of colonialism in Africa is a reminder of the enduring impact of historical injustices, but it also highlights the resilience and agency of African nations and their people.

Cite this page

Colonialism in Africa: A Historical Overview. (2024, Apr 01). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/colonialism-in-africa-a-historical-overview/

"Colonialism in Africa: A Historical Overview." PapersOwl.com , 1 Apr 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/colonialism-in-africa-a-historical-overview/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Colonialism in Africa: A Historical Overview . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/colonialism-in-africa-a-historical-overview/ [Accessed: 28 Apr. 2024]

"Colonialism in Africa: A Historical Overview." PapersOwl.com, Apr 01, 2024. Accessed April 28, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/colonialism-in-africa-a-historical-overview/

"Colonialism in Africa: A Historical Overview," PapersOwl.com , 01-Apr-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/colonialism-in-africa-a-historical-overview/. [Accessed: 28-Apr-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Colonialism in Africa: A Historical Overview . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/colonialism-in-africa-a-historical-overview/ [Accessed: 28-Apr-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

- Colonialism in Africa

Colonialism is the act by which a country or state exerts control and domination over another country or state. During a period lasting from 1881 to 1914 in what was known as the Scramble for Africa , several European nations took control over areas of the African continent.

European colonizers were able to attain control over much of Africa through diplomatic pressure, aggressive enticement, and military invasions. In fact, European countries competed with one another to see who could attain the most power and growth. At the height of colonization, only three sections of the continent had been untouched by European settlers:

- The Dervish State

Why Did European Countries Want to Colonize Africa?

In the years 1884 and 1885, the Berlin Conference formalized European colonization of Africa. Prior to this time, world superpowers such as Portugal, France, and Britain had already set up colonies in Africa. To a smaller extent, Germany and Italy had, too. By 1900, when the force of the quick colonization was over, the majority of the land in Africa was divided up amongst seven different European colonizing nations: Britain, France, Spain, Germany, Belgium, Italy, and Portugal. There were several different reasons why European colonizers set their sights on the African continent Some of the most prominent ones are outlined below:

Search for Riches

The 19th century was home to the industrial revolution , a time when many European nations were flourishing in the technology sector of the time. However, in order to accomplish these advancements, they needed a source of constant raw material supply. European powers noticed that many of these raw materials happened to be abundant in Africa.

Desire For Exploration

Prior to the wave of European colonization, the geography of Africa was generally misunderstood. Much like the adventurers who had traveled to Asia and North America, many European explorers set out to determine the physical makeup of the African continent.

Competition Between Colonizers

At the time of the Scramble for Africa, major world powers like Great Britain, France, and Spain were competing for power on the European stage. The amount of land that each country owned was considered to be a great indicator of power, with every state wanting to do better than their neighbor.

A large motivator behind African colonization was the desire to spread Christianity throughout the world. Much like what occurred in North and South America, European colonizers brought the Christian faith to Africa through missionaries.

Imperialism

A key ideology behind imperialism, which in turn informs colonialism, is the idea of racial superiority or cultural superiority. Again, much like the ideals behind the colonialism of the Americas, many European colonizers thought that they were doing a favor to those living on the African continent by introducing to them the European way of life, even if it came at the cost of destroying established societies.

Life In Africa Under Colonialism and Beyond

Life for the African people during colonization was difficult. Many of the ideologies behind imperialism were discriminatory in nature, using racist beliefs to justify harsh authoritarian leadership styles.

Throughout the colonial period, the societies that had been established in Africa fought hard to fend off their European colonizers. However, due to the fact that European powers were disproportionately aided by the products of the industrial revolution, many former empires and kingdoms that had been present in Africa were at a disadvantage and lost to the colonizers. Throughout this time, Africa was forever changed.

It has been argued that the poverty that is still experienced today in many African countries is a lasting effect of colonialism. The fact that many countries in Africa still experience high levels of poverty today, often despite the country’s natural riches, is used as proof by many that the colonialization of Africa did more harm than good.

British Colonies in Africa

- Anglo-Egyptian

- Bechuanaland

- British East Africa

- British Somaliland

- British Togoland

- British Cameroons

- British Egypt

- Gambia Colony and Protectorate

- Colonial Nigeria

- Northern Rhodesia

- Sierra Leone Colony and Protectorate

- South Africa

- South-West Africa

- Southern Rhodesia

- Tanganyika Territory

- Uganda Protectorate

- Sultanate of Zanzibar

Belgian Colonies in Africa

- https://lsigraph.com/Belgian Congo

- Lado Enclave

- Ruanda-Urundi

French Colonies in Africa

- French Dahomey

- French Algeria

- French Cameroons

- French Chad

- French Congo

- French Guinea

- French Upper Volta

- French Somaliland

- French Sudan

- French Togoland

- French Madagascar

- Ivory Coast

- Colonial Mauritania

- French Protectorate in Morocco

- Oubangui-Chari

- Senegambia and Niger

- French protectorate of Tunisia

German Colonies in Africa

- German East Africa

- German South-West Africa

Portuguese Colonies in Africa

- Algarve Ultramar

- Mozambique

- Portuguese Gold Coast

- Portuguese Guinea

- Sao Tome and Principe

More in Society

Countries With Zero Income Tax For Digital Nomads

The World's 10 Most Overcrowded Prison Systems

Manichaeism: The Religion that Went Extinct

The Philosophical Approach to Skepticism

How Philsophy Can Help With Your Life

3 Interesting Philosophical Questions About Time

What Is The Antinatalism Movement?

The Controversial Philosophy Of Hannah Arendt

How Africa’s colonial history affects its development

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Ewout Frankema

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Africa is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

The supply of African slaves to American plantations reached an all-time high in the late 18th century (Klein 1999). After anti-slave trade legislation finally shut down the Atlantic slave exports, commodity exports filled the gap. This so-called ‘commercial transition’ was completed in West Africa before it hit East Africa (Austen 1987, Law 2002). It was a game-changer, since it put a halt to the continuous drain of scarce labour and paved the way for the expansion of land-intensive forms of tropical agriculture, engaging smallholders, communal farms, and estates.

The establishment of colonial rule over the African interior (c. 1880-1900) reinforced Africa’s commodity export growth. Colonial control facilitated the construction of railways, induced large inflows of European investment, and forced profound changes in the operation of labour and land markets (Frankema and van Waijenburg 2012). That is, colonial regimes abolished slavery, but they replaced it with other forced labour schemes. The scramble pushed African exports to new heights, but without the preceding era of commercialisation the African scramble probably would never have taken place.

The Industrial Revolution

Africa’s commercial transition was inextricably connected to the rising demand for industrial inputs from the industrialising core in the North Atlantic. Revolutions in transportation (railways, steamships), a move towards liberal trade policies in Europe, and increasing rates of GDP growth enhanced demand for (new) manufactures, raw materials and tropical cash crops. African producers responded to this demand by increasing exports of vegetable oils (palm oil, groundnuts), gum, ivory, gold, hides and skins. Palm oil, a key export, was highly valued as a lubricant for machinery and an ingredient in food and soap. During and after the scramble, the range of commodity exports broadened to include raw materials like rubber, cotton, and copper, as well as cash crops such as cocoa, coffee, tea and tobacco. The lion’s share of these commodities went directly to manufacturing firms and consumers in Europe. Meanwhile, technological innovations also reduced the costs of colonial occupation. These included the Maxim gun, the steamship, the railway and quinine, the latter lowering the health risks to Europeans in the disease-ridden interior of the ‘dark continent’.

The African trade boom

To obtain a deeper understanding of the connection between Africa’s commercial transition and subsequent colonial intervention, we constructed annual time-series of export volumes, export values, commodity export prices, import prices, and the net barter terms (the ratio of average export to average import prices). The data cover the period from the heyday of the Atlantic slave trade in the 1790s to the eve of World War II, 1 and make it possible to analyse the commercial transition with much greater precision than was possible previously and to compare the development of African trade with other commodity exporting regions (Williamson 2011).

There was a prolonged rise in the net barter terms of trade for sub-Saharan Africa from the 1790s to the 1880s, a commodity price boom that was especially pronounced in the four decades between 1845 and 1885. Figure 1 shows that this secular price boom peaked exactly at the date of the Berlin conference (1884-5), when diplomats negotiated how to carve up Africa among the European imperialists. The terms of trade tripled in just four decades. While the terms of trade for commodity exporters were rising everywhere in what was once called the Third World, nowhere was the boom greater than for Africa. Furthermore, the scramble started right at the moment when African exports reached their highest exchange value.

Figure 1 . Terms of trade for sub-Saharan Africa, 1784-1939 (1900=100)

Notes : Excluding South Africa, Mauritius, Madagascar and Reunion. Smoothed trend derived using Hodrick-Prescott filter, with a smoothing factor set to 100.

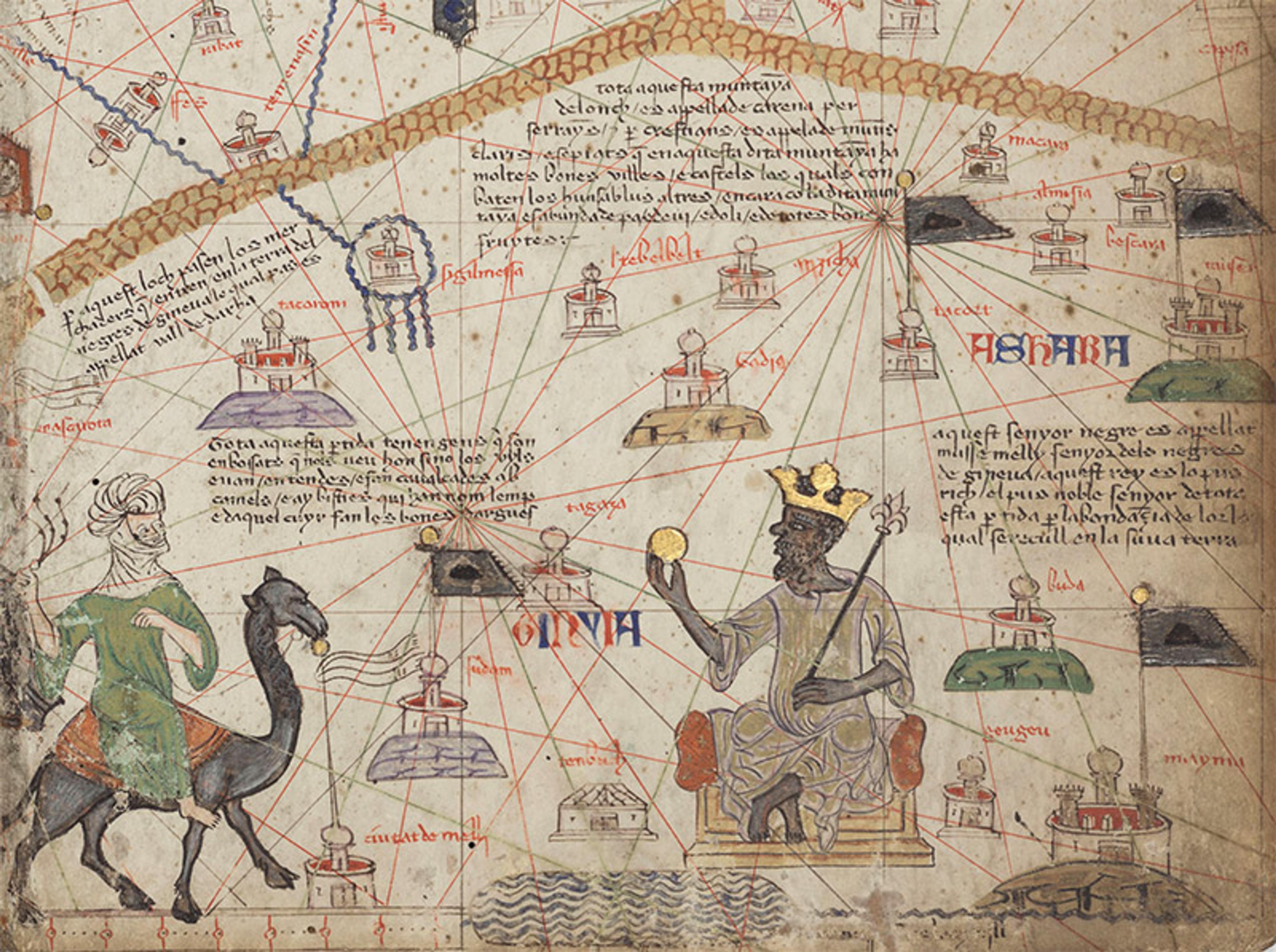

The share of West African exports in French imperial trade was much larger than it was in British imperial trade. Around the mid-19th century, about two thirds of French imperial trade was with Africa, the largest part of it with North Africa (e.g. Algeria), but a substantial share was also with West Africa. British imperial trade was dominated by India, and this distinction is consistent with the chronology of the scramble. The French set a chain reaction in motion by moving into the West African interior to survey the possibilities of a railway connection between the major trading hubs of the middle Niger delta (Gao, Timbuktu) and their trading enclaves along the Senegalese coast. The British responded by securing the lower Niger delta. After less than two decades, virtually the entire continent was divided among a handful of European powers.

Africa’s commodity boom in global perspective

The long-term secular trend of sub-Saharan Africa’s terms of trade coincided with the patterns observed in other parts of the commodity-exporting periphery. However, the price boom of 1845-1885 was exceptionally sharp compared with Latin America, Southeast Asia, India and China. From start to peak, the purchasing power of African exports rose by 3% per annum. Although Africa’s share of world exports remained modest, the trend fuelled an optimistic assessment of the future profitability of colonisation, French assessments in particular. Merchants, industrial capitalists, explorers (like David Livingstone) and even Christian missionaries added to the babble about new markets, new investment prospects, new converts, and the moral obligation to abolish African slavery and replace it with a commercial model.

Did colonisation lock Africa into a perverse path of specialisation?

Ironically, the secular terms of trade boom turned into an equally prolonged bust right at the time that the scramble gained steam. This price bust continued, with only some temporary reversals, up to the eve of World War II. In fact, in 1940 Africa’s terms of trade were back at their 1800 levels. Table 1 below shows that export volumes continued to expand after 1885 at a faster pace than before, thus offsetting the price declines. In other words, African farmers, European planters and mining firms specialised more and more in commodities as they became worth less and less.

Table 1 . Decomposition of export growth in British and French West Africa, 1850-1929

Does this mean that European colonisation locked Africa into a path of perverse specialisation? There are two plausible answers to this question: “yes” and “no”. The “yes” view is that expanding imports of European manufactures, coercive cultivation and mining schemes, and free-trade policies effectively pre-empted a diversification of African economies into manufacturing and eroded indigenous handicrafts. Only white-dominated settler economies that were able to operate with some degree of autonomy, such as South Africa and Southern Rhodesia, managed to develop a substantial industrial sector, albeit relying on a combination of protective barriers and African labour coercion. The alternative answer is “no”. Colonial trade simply followed a path that had already been blazed in the early 19th century. Manufacturing was inconsistent with African endowments and thus its comparative advantage. With abundant land and mineral resources, and scarce labour and human capital, commodity specialisation was the most efficient way to exploit world trade, and to move up the technology and skill ladder (Austin et al. 2016). The debate between these two competing views has not yet been resolved.

Is history repeating?

Today, China uses diplomacy in Africa instead of brute force, and it does not seem to aspire to formal political control in the region. Yet, African economies are again responding to the rising demand for commodities by a rapidly industrialising power. Chinese investments in land, infrastructure and mines are flowing in. Mineral exports, and especially oil, are again taking a growing share of African exports. History shows that such export booms are unsustainable, but what are the chances that Africa will avoid a renewed cycle of commodity dependency? As we ponder the answer, a major difference with history should be noted. With a projected population of over 3 billion, Africa will be one of the most populous regions of the world in 2050. If African policymakers find ways to invest commodity windfalls in the health and education of the next generations and to increase trade with neighbour countries, export growth may do more to stimulate African economic development than it did a century ago.

Austen, R A (1987), African Economic History: Internal Development and External Dependency , London: James Curry/Heinemann.

Austin G, E Frankema and M Jerven (2016), “Patterns of Manufacturing Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa: From Colonization to the Present,” forthcoming in K O’Rourke and J G Williamson (eds), The Spread of Modern Manufacturing to the Periphery, 1870 to the Present , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Frankema E, J G Williamson and P Woltjer (2015), “An economic rationale for the African scramble: the commercial transition and the commodity price boom of 1845-1885.” NBER Working Paper 21213.

Frankema, E H P and M Van Waijenburg (2012), “Structural Impediments to African Growth? New Evidence from Real Wages in British Africa, 1880-1965”, Journal of Economic History 72(4), pp. 895-926.

Klein, H S (1999), The Atlantic slave trade , Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Law, R (2002), From slave trade to legitimate commerce: the commercial transition in nineteenth-century West Africa , Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Williamson, J G (2011), Trade and poverty when the Third World fell behind , Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

1 These data will be made available as part of Wageningen African Commodity Trade Database, 1500-present, to be released in the autumn of 2015 at the website of the African Economic History Network, www.aehnetwork.org

This article is published in collaboration with VoxEU . Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter .

Author: Ewout Frankema is professor and chair of Rural and Environmental History at Wageningen University and elected member of the Young Academy of the Royal Dutch Academy of Arts and Sciences. Professor Jeffery Williamson is the Laird Bell Professor of Economics at Harvard University. Pieter Woltjer is a postdoc researcher at Wageningen University (department of Rural and Environmental History) where he is currently working on the study of long-term African welfare development.

Image: A woman walks by the beach of Kenya’s coastal city of Mombasa. REUTERS/Marko Djurica.

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Geographies in Depth .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

How can Japan navigate digital transformation ahead of a ‘2025 digital cliff’?

Naoko Tochibayashi and Naoko Kutty

April 25, 2024

What is desertification and why is it important to understand?

Andrea Willige

April 23, 2024

$400 billion debt burden: Emerging economies face climate action crisis

Libby George

April 19, 2024

How Bengaluru's tree-lovers are leading an environmental restoration movement

Apurv Chhavi

April 18, 2024

The World Bank: How the development bank confronts today's crises

Efrem Garlando

April 16, 2024

How African cities can learn from each other about building climate resilience

Babajide Oluwase

April 15, 2024

Colonialism in Africa: An Introductory Review

- First Online: 26 July 2023

Cite this chapter

- Lawson Onyema Chukwu 2 &

- G. N. Obah-Akpowoghaha 3

152 Accesses

3 Altmetric

- The original version of this chapter was revised: Incorrect author name ‘Nelson, OA.G.’ instead of ‘Obah-Akpowoghaha, G. N.’ has been corrected for this chapter. The correction to this chapter is available at https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-0245-3_19

Colonialism has left different forms of impact across the globe. The history of post-independence Africa was the outcome of the history of colonialism. At the dawn of the twentieth century, majority of African territories were under European colonial rule. The division and subsequent colonization of the African territories were efforts of European nations to intensify European imperialism. European countries engaged in antagonistic expansion policy because of essentials that were created by Industrial Revolution. Put differently, European colonization of the African continent was primarily impelled by economic forces; Africa to serve as a source of raw materials for their industries in Europe and as well market place for their finished products. This book, especially the first part of it, simply presents how colonialism laid the foundation for African underdevelopment.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Change history

14 october 2023.

A correction has been published.

Afigbo, A. E. (1972). The Warrant Chiefs: Indirect Rule in Southeastern Nigeria . London: Longman Group Limited.

Google Scholar

Ajayi, A. J. F., and Espie, I. (Eds). 1965. A Thousand Years of West African History: A Handbook for Teachers and Students . University of Ibadan: Ibadan University Press and Nelson.

Ani, K. J. (2013). “German Bid for Colonies in Africa: Fillip to Violent Imperialism and Global Integration.” NDUNODE; Calabar Journal of the Humanities 10 (1): 1–17.

Asante, T. K. (2014). “National Movements in Colonial Africa.” Journal of The History of African Development 1: 1–12.

Eluwa, G. I. C. et al. (1996). Africa and the Wider World Since 1800 A.D. Onitsha: Africana First Publisher Ltd.

Falola, T., Uhomoibhi, M., Mahadi, A., and Anyanwu, U. (1991). History of Nigeria 3 . Nigeria: Learn Africa Plc.

Hanna, A. J. (1961). European Rule in Africa. Historical Association of Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Hobson, J. A. (1938). Imperialism: A Study. Third Edition. London.

Kamalu, N. C. (2019). “British, French Belgian and Portuguese Models of Colonial Rule and Economic Development in Africa.” Annals of Global History 1 (1): 37–47.

Article Google Scholar

Livingston, D. (1868). Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa. New York: Harpers.

Miles, W. (1994). Hausa Land Divided: Colonialism and Independence in Nigeria and Niger . Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Nkrumah, K. (1963). Africa Must Unite . New York: Frederick A. Praeger Publisher.

Onwubiko, K. B. C. (1973). History of West Africa 1800-Present Day. First Edition. Africana Educational Publishers Ltd.

Oyebade, A. (2002). Colonial Political System in Africa 1885 – 1939, Vol. 3, Edited by Toyin Falola. Durham: Carolina Academic Press.

Palmer, N. D., and Perkins, H. C. (2007). Zac Relations . Delhi: A.I.T.B.S. Publishers.

Uwechue, R. (1991). Africa Today. Second Edition, Published by African Books Ltd, 169–171

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of History and Strategic Studies, Alex Ekwueme Federal University, Ndufu Alike Ikwo, Abakaliki, Nigeria

Lawson Onyema Chukwu

Department of Political Science, University of The Gambia, Serrekunda, Gambia

G. N. Obah-Akpowoghaha

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lawson Onyema Chukwu .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of History and Strategic Studies, Alex Ekwueme Federal University, Ndufu-Alike Ikwo, Nigeria

Kelechi Johnmary Ani

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Chukwu, L.O., Obah-Akpowoghaha, G.N. (2023). Colonialism in Africa: An Introductory Review. In: Ani, K.J. (eds) Political Economy of Colonial Relations and Crisis of Contemporary African Diplomacy. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-0245-3_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-0245-3_1

Published : 26 July 2023

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-99-0244-6

Online ISBN : 978-981-99-0245-3

eBook Packages : Political Science and International Studies Political Science and International Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Impacts of Colonialism on Africa Essay

Colonialism confronts simple definition, for its usage has tended to reflect changing moral judgments. In the late 1800s, the term was applied only to colonies of white settlers and was used in either of two ways, both morally neutral, a trait characteristic of such colonies, and the political status of a dependency as distinct from the metropolis or another sovereign state.

Actually, the term colonialism rarely was used in the sense of a colonial system. Its later usage resulted from its adoption as part of the verbal ammunition of the age of decolonization. In this, it suffered the fate of “imperialism,” which after 1900 was adopted by critics of European expansion to serve ideological purposes and used imprecisely to suggest both the annexation of territories and their subsequent state of subordination, in each case to serve the economic interests of the capitalist powers of Europe and North America. By the mid of 1900s, colonialism also began to be used in this derogatory sense. (Doctrines on colonialism 1)

The two terms were gradually refined and distinguished. Whereas “imperialism” came to indicate the dynamics of European empire-building and, for Marxists, the special character of the capitalist societies that acquired empires, “colonialism” described the resultant complex of political and economic controls imposed on dependencies. Colonialism, therefore, must now be taken to denote the colonial system in its post-expansionist phase, with the implication that it constituted a system of controls that was constructed by the imperial powers to subordinate and exploit their dependencies. (Singh 1)

Let’s take a view of the history of Colonization the special feature common to most modern colonial systems was that dependencies were geographically separated from their metropolis, although they remained under some degree of imperial control. The only power of which this was not true was Russia, whose “colonies” stretched without a break from its territory in Europe to the borders of India and to the Bering Strait. Although contiguous, these outlying provinces were true colonial dependencies; for they had been distinct ethnic and economic units with which Russia’s initial relations were those of conqueror or colonizer. (Johnston 2-5)

The Russian Empire provides a conceptual bridge between the modern colonial empires and other territorial empires at earlier periods, most of which was continental and contiguous to the metropolis. Most of Europe, Asia, Africa, and Central and South America at one time fell under the authority of an imperial dynasty or state. The greatest ancient imperial powers were Egypt, Babylonia, Assyria, Persia, Rome, Byzantium, the Carolingians, the Arabs, China, the Incas, and the Aztecs—were essentially continental.

Maritime empires were few and unspectacular before modern European overseas colonization. In classical times the Phoenicians, Greeks, Carthaginians, and Romans established overseas colonies. Later, Hindus and Muslims from India and Arabia settled territories of the Indian Ocean and Indonesia, and the Chinese colonized much of Southeast Asia. However, these settlements generally lacked central control or even continuing contact with the parent state.

For the most part, neither the great continental empires nor earlier maritime settlements had much in common with modern colonial systems—the former because they were territorially contiguous, the latter because they lacked central control. However, then, as later, both the motives that led to the creation of the systems, and the patterns of government, trade, or culture that emerged, were infinitely varied.

Continental empires were the product of multiple factors, notably dynastic ambition, frontier insecurity, religious fanaticism, or the need for land or slave labor. The same variety of motives is seen in earlier maritime colonization in which trade, surplus population, dynastic ambition, and religion figured. Colonial systems were equally varied. Some empires attempted to impose cultural uniformity; others did not. Some were highly centralized administratively; others consisted of essentially autonomous provinces. (Brunelle n.p.)

Modern European expansion can be dated from the Portuguese conquest of Ceuta (in Morocco) in 1415 to the Italian occupation of Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in 1936. Within this period there were two overlapping cycles, the first ending with the independence of the majority of the original colonies in the Americas in the 1820s, and the second beginning with the British conquest of Bengal in and after 1757. During the first cycle, most of the European colonies were in the Western Hemisphere. During the second cycle, the colonial empires encompassed much of Asia, the Pacific, and Africa. Behind these geographical contrasts lay fundamental differences in the character of colonialism. (Fieldhouse n.p.)

The paradoxical feature of the first cycle was that the states of Western Europe established vast empires in America almost by accident. Columbus intended to find an oceanic route to the East, not to found colonies. He failed, but Spain found compensation in the gold and silver resources of parts of Central and South America. Colonization there was the result of the first overseas gold rush by Europeans. In the wake of the first conquistadores came missionaries, administrators, settlers, and craftsmen. By 1650, Spain, Portugal, France, England, and the Netherlands all had colonies in America.

The motives of the colonizers varied, and their enterprises at first were experimental. Many hoped to find gold or silver. The search for a northwest passage to China continued. French and English fishermen needed bases near the Newfoundland Banks. Emigrants were attracted by free land or hoped to escape political or religious persecution at home. American colonization was an unforeseen and largely uncontrolled reaction to the challenge of discovery.

In other parts of the world the character of European expansion was quite different and to some extent was the result of deliberate planning. The general pattern was set by Portugal, which from the 1400s aimed to exploit the discovery of a route to the East round the Cape of Good Hope for commercial rather than colonizing purposes. Portugal did establish territorial possessions in certain parts of Africa and Asia, but on the whole, it chose to limit its commitments to coastal bases, relying on naval power and treaties with indigenous rulers to provide suitable conditions for a profitable trade. The French, English, and Dutch followed this example.

Nevertheless, European colonial empires expanded anew in the latter 1800s. This “new imperialism” is conventionally explained in terms of changing European economic needs and interests. Sources of raw materials, fields for investment, and ever-larger markets were needed, and fear of exclusion from regions controlled by other states forced each country to establish colonies in order to protect its interests. An alternate explanation holds that, with intensified international rivalries, each state claimed colonies to increase its strategic power, to defend its trade routes, or to use pawns in diplomacy. Finally, it has been suggested that colonization reflected a new aggressive nationalism in Europe, produced partly by international rivalries and partly by racist theories.

All these explanations focus on Europe, but while there were elements of truth in each, the evidence suggests that the dynamics of European expansion once again lay outside Europe: that imperialism was a reaction to crises and opportunities in Asia, the Pacific, and Africa rather than the product of needs and calculated policies within Europe. Crises might result from the frontier problems or expansionist tendencies of existing colonies, from the disintegration of indigenous political or social systems, or from rivalries between Europeans on the spot. Such situations might induce a European government to annex. (The New Imperialism n. p.)

Between 1880 and 1910 the tempo of annexation was quickened partly because crises occurred simultaneously in many areas and partly because Germany, Belgium, the United States, Italy, and Japan joined the existing group of maritime nations and Russia as colonial powers. The outcome was the virtually complete partition of Africa and the Pacific region and an increase of colonial territory in Asia. By 1914, Europe dominated every continent except the Americas, which in turn were dominated, indirectly, by the United States.

The period from 1914 to 1939 was the apogee of the modern colonial empires. After World War I, German, Japanese, and Ottoman territories were assigned mainly to European powers. These territories technically were League of Nations mandates, but they were administered like other dependencies. With the Italian occupation of Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in 1936, the colonial empires reached their territorial peak. Most western European countries were colonial powers, as were the United States and Japan. Russia, by this time a Socialist state, disclaimed colonies but retained those parts of central and eastern Asia that the Czarist regime had acquired, technically as autonomous republics.

World War II marked the beginning of the end. Europe lost control of most possessions in the Pacific and Southeast Asia to Japan, and other colonies were isolated from their metropolises. Although most ties were restored after 1945, the dissolution of empires had begun.

The reasons are not entirely clear. Hostility to alien rule sprouted or increased. Changing attitudes in Europe weakened faith in the moral basis and the practical advantages of colonialism. Russia and then China supported revolutionary movements. The first dependencies to gain independence—India, Pakistan, Ceylon, Burma, and Indonesia—inspired nationalists elsewhere.

By the late 1960s, only a few colonies remained notably Portuguese and Spanish territories in Africa, and some British, U. S., and French dependencies, which could not easily be set adrift or which still provided useful military facilities. Colonialism in the formal sense was dead.

There remained, however, a complex of economic and political influences exercised by the advanced over the less advanced world. Labeled “neocolonialism” by its critics, this predominance became the focus of the anti-European and anti-American complaints. Whether it differed in substance from the predominance exercised by the USSR over the eastern European states and how the imbalance of power could be redressed was open questions. (Bissell and Radu 1-7)

After the above-detailed discussion on the background of Colonialism now we proceed towards its impacts on Africa

From 1914 to 1939 saw the peak and the beginning of the decline of the colonial system in Africa. The administrations established by the major colonial powers before 1914 had three primary goals, first to protect law and order, and to erect an administrative makeup designed for effective government at a minimum cost, and to promote forms of economic development that would provide raw materials demanded by markets in the home country.

The political and administrative institutions that the Europeans created in their African colonies were modeled on those they knew best, their own. Frequently there was little regard for the fact that these institutions had been developed for European countries, whose histories, social backgrounds, and administrative needs bore little if any relationship to those of Africa. For the most part during the colonial period, little consistent thought was given by European administrators to the long-range development of the colonies toward independence. Moreover, some administrations forced Africans to work under deplorable conditions or to plant export crops instead of staple food crops. It was only through the gradual spread of education and the consequent emergence of political awareness among a small segment of the African population that demand arose for a share in political power. From this small group of nationalist leaders came the popular movements that finally swept the colonial administrations out of existence. (Cowan 1 of 1)

In the case of Britain, the theory of “indirect rule” was the basis of administration. British officers governed through the traditional chiefs, seeking to preserve as far as possible the power and prestige of those leaders while adapting the customary methods of the rule to meet the needs of modern society. It was hoped in this way to ease the impact of the transition from traditional to modern government. By 1939, however, it was becoming clear that indirect rule was unsatisfactory; the chiefs could not always be adapted to new ways, and the system left no place for the young, educated Africans to share in local administration. Gradually, in the years after World War II, elected local councils were substituted for the “native authorities”. These new councils became the testing ground for nationalist political parties.

France, in its African colonies, pursued a policy of assimilation and direct rule. The objective was to acquaint its African subjects as fully as possible with French institutions, language, and culture, the ultimate goal being the complete assimilation of the colonies to the home country. For this reason, little effort was made until after World War II to create representative political institutions in the colonies, and the traditional chiefs were largely subordinated to the French administrations. In the long run, French assimilation was no more successful than British indirect rule. For the comparatively small number of Africans who were able to enjoy the full benefits of the French educational system, assimilation was complete. Most Africans, however, were only superficially exposed to the French way of life and proved unwilling to give up their traditional cultures, particularly in the Muslim areas, where religion became a block to full acceptance of France. Beginning in 1946, therefore, efforts were made to create territorial assemblies, or local parliaments, in each colony. (Cowan 1 of 1)

Portuguese policy, to a greater degree than that of France, was based on full assimilation. Administratively the colonies were regarded as overseas provinces of Portugal. But Portuguese rule was characterized by abuse of authority, a low level of African education, and (except in Angola after World War II) severe limitations on economic development. In part, this restrictive policy could be accounted for by the poverty of Portugal itself, yet it was also a reaction to the spread of nationalism elsewhere in Africa. Portuguese resistance to the trend toward independence resulted in the outbreak of revolution in its territories in the early 1960s. Only after a military coup deposed Portugal’s conservative government in 1974 did that country become reconciled to the end of its colonial empire.

In the Belgian Congo, the home country pursued a policy of strong paternalism. Africans were prepared by widespread primary education for technical positions, but virtually no attempts were made to create African political representation, nor were political parties organized. In consequence, when Belgium decided in 1960 to grant immediate independence, the colony was unprepared for self-rule and chaos ensued.

Two colonial powers, Germany and Italy, disappeared from Africa between 1918 and 1943. Following World War I the German colonies were separately placed under the administration of Belgium, Britain, France, and South Africa—at first under the overall supervision of the Mandates Commission of the League of Nations, and after 1945 under the Trusteeship Council of the United Nations in preparation for their independence. Italy lost all its colonies during World War II. Ethiopia regained full sovereignty in 1941 after less than five years of Italian rule, and after the war, the Italian colony of Eritrea was joined to Ethiopia. The other two Italian possessions became independent. (Cowan 1 of 1)

Although the colonial system was showing signs of decline by 1939, what shattered the old order was World War II. The war exposed the weakness of the major colonial powers and had profound effects on all dependent territories in Africa. The European belligerents, hard-pressed by their war effort, made exceptionally heavy demands on their African subjects. Because of the shortage of officials, the colonial administrations were forced to grant Africans a degree of responsibility that would hitherto have been impossible. African leaders showed that they were capable of holding the reins of government. In turn, they encouraged and organized the popular demand for autonomy that forced the colonial powers to give way, first in local government and later at the level of central administration. As new institutions for popular representation were created, the stage was set for the transformation to self-government and finally, by the mid-1950s, to full independence.

Although World War II accelerated the growth of African nationalism, the seeds of independence had been sown in most parts of the continent before the war. In Egypt, for example, what prompted British occupation in 1882 was a nationalist movement expressing popular discontent with international control of the country?