- Reviewer Guidelines

- Peer review model

- Scope & article eligibility

- Reviewer eligibility

- Peer reviewer code of conduct

- Guidelines for reviewing

- How to submit

- The peer-review process

- Benefits for Reviewers

Guidelines for Article Reviewers

- Authors are eligible to publish - authors must be formally affiliated with Wellcome funding.

- Article types – articles are checked whether they meet the criteria and format of specific article types .

- Readability – as we do not copy edit articles, the standard of language and readability must be sufficient for readers to be able to follow the article.

- Plagiarism – articles are checked for plagiarism before publication.

- Methods section – we check that details of methods and resources are provided, so that the work can be assessed (we will ask you as an expert reviewer to comment whether more information would be required for others to reproduce the work).

- Policies – we check that articles publishing research involving humans or animals adhere to our ethical policies .

- Data – we check that the source data underlying the results are made openly available (we will ask you as an expert reviewer to comment whether the source data are appropriate for others to reproduce the work).

- Read the article fully – please read the full text of the article and view all associated figures, tables and data;

- Be thorough – a peer review report should discuss the article in full as well as individual points, and should demonstrate your understanding of the article;

- Be specific – your comments should contain as much detail as possible, with references where appropriate, so the authors are able to fully address the issue;

- Be constructive in your criticism – do not hesitate to include any concerns or criticisms you may have in your review, however, please do so in a constructive and respectful manner;

- Avoid derogatory comments or tone – review as you wish to be reviewed and ensure that your comments focus on the scientific content of the article in question rather than the authors themselves.

- Approved: No or only minor changes are required. For original research, this means that the experimental design, including controls and methods, is adequate; results are presented accurately and the conclusions are justified and supported by the data.

- Approved with Reservations: The reviewer believes the paper has academic merit, but has asked for a number of small changes to the article, or specific, sometimes more significant revisions.

- Not Approved: The article is of very poor quality and there are fundamental flaws in the article that seriously undermine the findings and conclusions.

- Is the work clearly and accurately presented and does it cite the current literature?

- Is the study design appropriate and does the work have academic merit?

- Are sufficient details of methods and analysis provided to allow replication by others?

- If applicable, is the statistical analysis and its interpretation appropriate?

- Are all the source data underlying the results available to ensure full reproducibility?

- Are the conclusions drawn adequately supported by the results?

- Are the rationale for, and objectives of, the Systematic Review clearly stated?

- Are sufficient details of the methods and analysis provided to allow replication by others?

- Is the statistical analysis and its interpretation appropriate?

- Are the conclusions drawn adequately supported by the results presented in the review?

- Is the rationale for developing the new software tool clearly explained?

- Is the description of the software tool technically sound?

- Are sufficient details of the code, methods and analysis (if applicable) provided to allow replication of the software development and its use by others?

- Is sufficient information provided to allow interpretation of the expected output datasets and any results generated using the tool?

- Is the rationale for developing the new method (or application) clearly explained?

- Is the description of the method technically sound?

- Are sufficient details provided to allow replication of the method development and its use by others?

- If any results are presented, are all the source data underlying the results available to ensure full reproducibility?

- Are the conclusions about the method and its performance adequately supported by the findings presented in the article?

- Is the rationale for creating the dataset(s) clearly described?

- Are the protocols appropriate and is the work technically sound?

- Are sufficient details of methods and materials provided to allow replication by others?

- Are the datasets clearly presented in a useable and accessible format?

- Is the rationale for, and objectives of, the study clearly described?

- Is the study design appropriate for the research question?

- Are sufficient details of the methods provided to allow replication by others?

- Is the background of the case’s history and progression described in sufficient detail?

- Are enough details provided of any physical examination and diagnostic tests, treatment given and outcomes?

- Is sufficient discussion included of the importance of the findings and their relevance to future understanding of disease processes, diagnosis or treatment?

- Is the case presented with sufficient detail to be useful for other practitioners?

- Is the background of the cases’ history and progression described in sufficient detail?

- Is the conclusion balanced and justified on the basis of the findings?

- Is the rationale for commenting on the previous publication clearly described?

- Are any opinions stated well-argued, clear and cogent?

- Are arguments sufficiently supported by evidence from the published literature or by new data and results?

- Is the conclusion balanced and justified on the basis of the presented arguments?

- Is the rationale for the Open Letter provided in sufficient detail?

- Does the article adequately reference differing views and opinions?

- Are all factual statements correct, and are statements and arguments made adequately supported by citations?

- Is the Open Letter written in accessible language?

- Where applicable, are recommendations and next steps explained clearly for others to follow?

- Is the study design appropriate for the research question (including statistical power analysis, where appropriate)?

- Have the authors pre-specified sufficient outcome-neutral tests for ensuring that the results obtained can test the stated hypotheses, including positive controls and quality checks?

- Are the data able to test the authors’ proposed hypotheses by satisfying the approved outcome-neutral conditions (such as quality checks, positive controls)?

- Are the introduction, rationale and stated hypotheses the same as the approved Stage 1 submission? (required)

- Did the authors adhere precisely to the registered experimental procedures? If not, has an explanation been provided regarding any change?

- Are any unregistered post hoc analyses added by the authors justified, methodologically sound and informative?

Are you a Wellcome-funded researcher?

If you are a previous or current Wellcome grant holder, sign up for information about developments, publishing and publications from Wellcome Open Research.

We'll keep you updated on any major new updates to Wellcome Open Research

The email address should be the one you originally registered with F1000.

You registered with F1000 via Google, so we cannot reset your password.

To sign in, please click here .

If you still need help with your Google account password, please click here .

You registered with F1000 via Facebook, so we cannot reset your password.

If you still need help with your Facebook account password, please click here .

If your email address is registered with us, we will email you instructions to reset your password.

If you think you should have received this email but it has not arrived, please check your spam filters and/or contact for further assistance.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Guidelines for Reviewers

PLOS ONE relies on members of the scientific research community to assess the validity of articles under consideration through peer review.

Invitation to Review

PLOS ONE editors select potential reviewers based on their expertise in research areas relevant to the manuscript under consideration. Reviewer invitations are sent by email from the journal's Editorial Manager submission system. Use the links in the invitation email to accept or decline, or check the “New Reviewer Invitations” folder on your Reviewer Main Menu screen in Editorial Manager. Accept an invitation only if you have the knowledge, time and objectivity necessary to provide an unbiased assessment of the research. In agreeing to complete a review, you also give permission to publish your review under a Creative Commons Attribution CC BY license.

Our Peer Review Process

PLOS ONE practices single-anonymized peer review by default, but offers opportunities for authors and reviewers to participate in signed and published peer review.

Our peer review model

Best practices for reviewers, receiving credit.

In choosing to volunteer as a peer reviewer for PLOS, you are helping to support free and open access to rigorous research. We couldn’t be more grateful!

Submit Your Review Now

Learn about peer review, how to submit a peer review in editorial manager.

PLOS ONE uses a structured reviewer form to help reviewers focus on our publication criteria and improve the efficiency of peer review. Preview the form . The form contains two sections:

Comments to the author

Answers to the questions in this section are required and will be included in the decision letter to the author. For questions 1-4 select a response from the drop down (e.g., “Yes,” “No,” “I don't know,” “N/A”) and provide any details you wish. Enter the main text of your peer review in question 5, “Review Comments to the Author.”

Comments to the editor

Use this section to declare any potential or perceived competing interests. You’ll also have the option to list anyone who collaborated with you on the peer review, and indicate whether you think the submission should be highlighted on the PLOS ONE webpage if it goes on to be published. This will not play any role in the editorial decision-making process or be shared with the authors.

PLOS ONE does not allow confidential comments other than the declaration of competing interests. If you have confidential concerns relating to publication or research ethics, please contact us at [email protected] .

What to Assess

To be eligible for publication manuscripts must meet our criteria for publication and comply with our editorial and publishing policies . The following guidance relates to articles reporting the results of original research.

Criteria for publication

Unlike many journals which attempt to use the peer review process to determine whether or not an article reaches the level of 'importance' required by a given journal, PLOS ONE uses peer review to determine whether a paper is technically rigorous and meets the scientific and ethical standard for inclusion in the published scientific record.

Please carefully review our seven editorial criteria for publication as the criteria employed by PLOS ONE are quite different to other journals you may have reviewed for.

To be accepted for publication in PLOS ONE , research articles must satisfy the following criteria:

- The study presents the results of primary scientific research .

- Results reported have not been published elsewhere .

- Experiments, statistics, and other analyses are performed to a high technical standard and are described in sufficient detail.

- Conclusions are presented in an appropriate fashion and are supported by the data .

- The article is presented in an intelligible fashion and is written in standard English .

- The research meets all applicable standards for the ethics of experimentation and research integrity .

- The article adheres to appropriate reporting guidelines and community standards for data availability .

Reviewing Registered Reports

Registered Reports are primary research articles in which the methods and proposed analyses are peer reviewed prior to conducting experiments, data collection or analysis. The PLOS ONE publication criteria apply to Registered Reports as they would to any other research submitted to the journal, but the peer review process is slightly different. Assessment takes place in two stages and, if accepted, results in two linked publications.

Reviewing Lab Protocols

Lab Protocols describe reusable methodologies for experimental and computational techniques.They typically consist of a protocol on the protocols.io platform and a PLOS ONE manuscript that contextualizes it, but authors can elect to publish on protocols.io after manuscript submission.

The PLOS ONE publication criteria apply to Lab Protocols as they would to any other research submitted to the journal, but the peer review process is generally expedited and typically carried out by one internal Academic Editor and one external reviewer.

Lab Protocols are eligible for both signed and published peer review.

You will review the manuscript, while referencing the protocol on protocols.io or in PDF format as a supplementary information file.

Peer review aims to ensure that the manuscript complies with the submission guidelines and publication criteria for Lab Protocols.

Consider:

- Is the protocol of utility to the research community?

- Does it link to a protocol on protocols.io and is this attached in PDF format as a SI file?

- Are the methods and reagents described sufficiently?

- Are the controls and sample sizes appropriate?

- Do the authors demonstrate that the method is validated, either by linking to at least one supporting peer-reviewed publication, or by providing appropriate supporting data?

- If the manuscript contains new data, have the authors made this data fully available?

Reviewing Study Protocols

Study Protocols describe detailed plans and proposals for research projects that have not yet generated results. They consist of a single article on PLOS ONE that can be referenced in future research.

The PLOS ONE publication criteria apply to Study Protocols as they would to any other research submitted to the journal. Study Protocols are eligible for both signed and published peer review.

Study Protocols submitted with proof of ethics approval (if required) and external funding by a funder that has independently peer reviewed the protocol are typically accepted without further external peer review. If, however, the journal staff decide that further review is necessary, reviewers will be invited to ensure that the Study Protocol complies with the submission guidelines and publication criteria

- The protocol prerequisites: the research study should not have generated results, nor should participant recruitment or data collection be complete.

- Are the required ethical standards met?

- Does the manuscript provide valid rationale for the planned or ongoing study, with clearly identified and justified research questions?

- Is the protocol technically sound and planned in a manner that will lead to a meaningful outcome and allow testing of the stated hypotheses?

- Have the authors described where all data underlying the findings will be made available when the study is complete?

- Does the manuscript title contain the word “Protocol”?

- Is the methodology feasible and does the description provide sufficient methodological detail for the protocol to be reproduced and replicated?

- Are any recommended checklists provided as SI files?

- Have the authors registered on a research platform that is appropriate for the study type, like OSF, for example?

- For clinical trials, is the trial registered and has the registration number been provided? Has the author provided the required SI files?

- For systematic reviews and meta-analyses, is the PRISMA-P checklist provided and complete? Have the authors opted to register with PROSPERO?

Writing the review

The purpose of the review is to provide the editors with an expert opinion regarding the validity and quality of the manuscript under consideration. The review should also supply authors with explicit feedback on how to improve their papers so that they will be acceptable for publication in PLOS ONE . As you write, consider the following points:

- What are the main claims of the paper and how significant are they for the discipline?

- Are the claims properly placed in the context of the previous literature? Have the authors treated the literature fairly?

- Do the data and analyses fully support the claims? If not, what other evidence is required?

- PLOS ONE encourages authors to publish detailed protocols and algorithms as supporting information online. Do any particular methods used in the manuscript warrant such treatment? If a protocol is already provided, for example for a randomized controlled trial, are there any important deviations from it? If so, have the authors explained adequately why the deviations occurred?

- If the paper is considered unsuitable for publication in its present form, does the study itself show sufficient potential that the authors should be encouraged to resubmit a revised version?

- Are original data deposited in appropriate repositories and accession/version numbers provided for genes, proteins, mutants, diseases, etc.?

- Does the study conform to any relevant guidelines such as CONSORT, MIAME, QUORUM, STROBE, and the Fort Lauderdale agreement ?

- Are details of the methodology sufficient to allow the experiments to be reproduced?

- Is any software created by the authors freely available?

- Is the manuscript well organized and written clearly enough to be accessible to non-specialists?

- Is it your opinion that this manuscript contains an NIH-defined experiment of Dual Use concern ?

Although confidential comments to the editors are respected, any remarks that might help to strengthen the paper should be directed to the authors themselves.

We often ask the original reviewers to evaluate revised manuscripts and the authors’ response to reviewer comments. We hope that you’ll make yourself available for re-review and questions from the editors.

Editing reviewers’ reports

The editors and PLOS staff will not change any reviewer comments that are intended for authors to read, except with reviewer approval prior to the decision letter being sent. For example, we may request changes if language is deemed inappropriate for professional communication, or if the comments contain information considered confidential, such as competing interest declarations.

The Editorial Process

Decision process.

The editors make the final decision on whether to publish each submission based on the reviewers’ comments, the PLOS ONE criteria for publication , and their own assessment of the manuscript.

Conflicting reviews

If reviewers appear to disagree fundamentally, the editors may choose to share all the reviews with each of the reviewers and request additional comments that may help the editors to reach a decision. Decisions are not necessarily made according to majority rule. Experts may disagree, and it is the job of the Editor to make a decision. Editors evaluate reviewer recommendations and comments alongside comments by the authors and material that may not have been made available to reviewers. Please know that your recommendation has been duly considered and your service is appreciated, even if the final decision does not accord with your review.

More on our Editorial Process .

For more tips on peer review go to the Peer Review Center , and sign up to the Peer Review Toolbox .

If you have questions or concerns about the manuscript you are reviewing, or if you need assistance submitting the review, please email us [email protected] .

Peer Review General and Ethical Guidelines

The fundamentals of ethical reviewing.

Take advantage of the industry's most comprehensive publishing ethics guidelines.

We believe that ethical publishing leads to a better research community, where everyone is valued and everyone is responsible for the work they do. Wiley's Best Practice Guidelines on Publishing Ethics: A Publisher's Perspective, Second Edition , is widely acknowledged as the industry's most comprehensive publishing ethics guidance.

Read the Wiley Guidelines on editorial standards and processes, including peer review.

COPE guidelines for peer reviewers

Wiley provides membership of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) as an option for our journal editors. COPE serves more than 8,500 members around the world with practical tools, e-learning, seminars, and much more. COPE has developed Ethical Guidelines for Peer Reviewers, to which editors and their editorial boards can refer for guidance. Read the COPE guidelines on their webpage, Ethical Guidelines for Peer Reviewers .

Additional Resources

Visit our peer review training resources for expert advice on peer review.

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

How to review articles.

Become a reviewer | Things to consider | What to include | Your recommendation | Webinar | Web of Science Academy

Peer review is essential for filtering out poor quality articles by assessing the validity and integrity of the research. We value the work done by peer reviewers in the academic community, who facilitate the process of publication and drive research within their fields of expertise. Please visit the Reviewer Rewards page to learn more about discounts and free journal access offered to reviewers of articles for Sage journals.

If you are an inexperienced or first-time reviewer, the peer review process may seem daunting. In fact, peer review can be a very rewarding process that allows you to contribute to the development of your field and hone your own research and writing skills. The resources below will explain what peer review involves and help you to write useful reviews.

How to become a reviewer

There are three ways to register as a reviewer.

1. Create a journal-specific reviewer account on Sage Track. Search for the journal’s name here and then click the ‘Submit paper’ link. This will take you to the peer review system where you can create an account.

Why create an account on a specific journal Sage Track site?

- You will be part of the journal’s reviewer database.

- You can make your profile more attractive by adding keywords related to your areas of expertise to boost your chances of being invited to review.

- Editors can rate your reviews which may increase your chances of being invited to review again.

2. Contact the journal editor or editorial office directly. In your communication, express your interest, summarize your expertise, and present yourself as a valuable reviewer.

Why contact the editor or editorial office directly?

- If you’re unsure if your area of expertise fits the journal's scope you can double-check with the editor or editorial office directly before registering your details on the Web of Science or the journal’s Sage Track site.

- Editors get a firsthand look at your experience and expertise.

- This is an opportunity for you to introduce yourself and your interests to the editor to increase your chances of being invited to review.

3. Sign up to the Web of Science Reviewer Recognition Service . Indicate your interest in reviewing for a journal by clicking on the journal’s Reviewer Recognition page. Editors use Reviewer Recognition to find suitable reviewers for their journals and may contact you directly via the Reviewer Recognition site.

Why sign up to WoS Reviewer Recognition?

- Editors can clearly see your interest in reviewing for their journal.

- Editors can look into your reviewer insights, including which other journals you are reviewing for.

- Editors can rate reviewers as ‘excellent’.

- You can review your satisfaction of Reviewer Recognition.

- You can receive weekly email updates summarizing your reviewer activity on the site.

- For Sage Journals, a claimed review will result in the individual’s name being listed as a reviewer for that journal.

- Co-reviewers can also receive credit on Reviewer Recognition.

Once you are registered as a reviewer, the editors will send you an invitation to review if a manuscript in your area of expertise is submitted.

We understand that our reviewers are busy, so it may not always be possible for you to accept an invitation to review. To avoid delays, please inform the editor as soon as possible if you are unable to accept an invitation to review or encounter any issues after accepting. If you cannot review a manuscript, we appreciate if you can suggest an alternative reviewer.

Tip: To further increase your chances of receiving review invitations, see our comprehensive blog post on Steps to Strengthen Your Reviewer Profile .

Watch the Video Tutorial

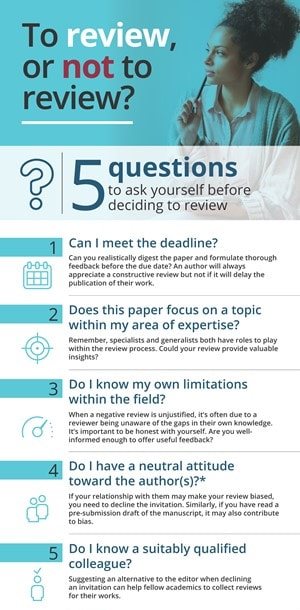

Things to consider before you begin a review

- Timing Inform the editor immediately if you will not be able to meet the deadline and keep your availability updated in Sage Track to avoid receiving invitations to review when you are unavailable.

- Suitability Do you have any reason why you should not review the submission? If in doubt, check with the journal’s editor. Learn more about your ethical responsibilities as a reviewer.

- Individual Journal Reviewer Guidelines Some journals ask reviewers to answer specific questions, so check what is expected before beginning your review.

- Confidentiality You must not share the content of a paper you have been invited to review, unless you have permission from the journal’s editor. If you suspect that author misconduct has taken place, only discuss this with the editor.

- Co-reviewing Inform the journal editor if you wish to collaborate on a review with a colleague or student. See the Ethics and Responsibility page for further instructions on this.

You may also wish to refer to COPE’s guide on what to consider when asked to peer review a manuscript before beginning a review .

What to include in a review

Watch our short video, How to Conduct a Peer Review , for a step-by-step walkthrough of the review process. Alternatively, you can download our Reviewer's Guide for written instructions on how to assess a manuscript and what to include in a review.

Watch the video tutorial

DOWNLOAD REVIEWER'S GUIDE PDF

Making your recommendation

In addition to your review comments, you will likely be expected to select an overall recommendation to the editor. Sage’s most common recommendation types are:

Accept: No further revision required. The manuscript is publishable in its current form.

The majority of articles require revision before reaching this stage.

Minor Revision: The paper is mostly sound but will be sent back to the authors for minor corrections and clarifications such as the addition of minor citations or the tweaking of arguments.

These revisions should not involve any major changes. However, changes should be clearly marked for the attention of the previous reviewers. The paper may be subject to re-review.

Major Revision: The principle of the article is sound and it has a chance of being accepted but requires substantial change to be made. This may include further experiments or analysis, the inclusion of additional literature or theory, or an improvement of arguments and conclusions. The authors are required to submit a point-by-point response to the reviewers and the paper will be subject to a re-review.

If issues of quality, novelty and/or contribution* cannot be addressed through revision, the reviewer should recommend rejection rather than revision. Editors withhold the right to reject the paper should revisions be insufficient.

Reject: The manuscript is of insufficient quality, novelty or significance to warrant publication.

Even when recommending rejection, the reviewer is encouraged to share their suggestions for improvement in the Comments to the Authors field.

If you would like to give us feedback on your experience of reviewing for a Sage journal to help us to improve our systems, please contact [email protected] .

*Check the journal Aims and Scope for any specific requirements with regard to levels of novelty and/or contribution.

How to Be a Peer Reviewer webinar

Considering becoming a reviewer or getting more involved with peer review? Our free webinar will guide you through the process of conducting peer review, including how to get started, basic principles of reviewing articles, what journal editors expect from reviewers, and important considerations such as research ethics and reviewer responsibilities. Learn more here .

Learn more with the Web of Science Academy

The Web of Science Academy offers free-of-charge short courses providing researchers with the skills and experience required to become an expert peer reviewer. Courses cover:

- What's expected of you as a reviewer

- What to look for in a manuscript

- How to write a review

- Co-reviewing with a mentor

A certificate is awarded on completion of the course.

- Journal Author Gateway

- Journal Editor Gateway

- What is Peer Review?

- How to Be a Peer Reviewer Webinar

- How to Review Plain Language Summaries

- How to Review Registered Reports

- Using Sage Track

- Peer Review Ethics

- Resources for Reviewers

- Reviewer Rewards

- Ethics & Responsibility

- Sage Editorial Policies

- Publication Ethics Policies

- Sage Chinese Author Gateway 中国作者资源

- Open Resources & Current Initiatives

- Discipline Hubs

Get Started

Take the first step and invest in your future.

Online Programs

Offering flexibility & convenience in 51 online degrees & programs.

Prairie Stars

Featuring 15 intercollegiate NCAA Div II athletic teams.

Find your Fit

UIS has over 85 student and 10 greek life organizations, and many volunteer opportunities.

Arts & Culture

Celebrating the arts to create rich cultural experiences on campus.

Give Like a Star

Your generosity helps fuel fundraising for scholarships, programs and new initiatives.

Bragging Rights

UIS was listed No. 1 in Illinois and No. 3 in the Midwest in 2023 rankings.

- Quick links Applicants & Students Important Apps & Links Alumni Faculty and Staff Community Admissions How to Apply Cost & Aid Tuition Calculator Registrar Orientation Visit Campus Academics Register for Class Programs of Study Online Degrees & Programs Graduate Education International Student Services Study Away Student Support Bookstore UIS Life Dining Diversity & Inclusion Get Involved Health & Wellness COVID-19 United in Safety Residence Life Student Life Programs UIS Connection Important Apps UIS Mobile App Advise U Canvas myUIS i-card Balance Pay My Bill - UIS Bursar Self-Service Email Resources Bookstore Box Information Technology Services Library Orbit Policies Webtools Get Connected Area Information Calendar Campus Recreation Departments & Programs (A-Z) Parking UIS Newsroom The Observer Connect & Get Involved Update your Info Alumni Events Alumni Networks & Groups Volunteer Opportunities Alumni Board News & Publications Featured Alumni Alumni News UIS Alumni Magazine Resources Order your Transcripts Give Back Alumni Programs Career Development Services & Support Accessibility Services Campus Services Campus Police Facilities & Services Registrar Faculty & Staff Resources Website Project Request Web Services Training & Tools Academic Impressions Career Connect CSA Reporting Cybersecurity Training Faculty Research FERPA Training Website Login Campus Resources Newsroom Campus Calendar Campus Maps i-Card Human Resources Public Relations Webtools Arts & Events UIS Performing Arts Center Visual Arts Gallery Event Calendar Sangamon Experience Center for Lincoln Studies ECCE Speaker Series Community Engagement Center for State Policy and Leadership Illinois Innocence Project Innovate Springfield Central IL Nonprofit Resource Center NPR Illinois Community Resources Child Protection Training Academy Office of Electronic Media University Archives/IRAD Institute for Illinois Public Finance

Request Info

How to Review a Journal Article

- Request Info Request info for.... Undergraduate/Graduate Online Study Away Continuing & Professional Education International Student Services General Inquiries

For many kinds of assignments, like a literature review , you may be asked to offer a critique or review of a journal article. This is an opportunity for you as a scholar to offer your qualified opinion and evaluation of how another scholar has composed their article, argument, and research. That means you will be expected to go beyond a simple summary of the article and evaluate it on a deeper level. As a college student, this might sound intimidating. However, as you engage with the research process, you are becoming immersed in a particular topic, and your insights about the way that topic is presented are valuable and can contribute to the overall conversation surrounding your topic.

IMPORTANT NOTE!!

Some disciplines, like Criminal Justice, may only want you to summarize the article without including your opinion or evaluation. If your assignment is to summarize the article only, please see our literature review handout.

Before getting started on the critique, it is important to review the article thoroughly and critically. To do this, we recommend take notes, annotating , and reading the article several times before critiquing. As you read, be sure to note important items like the thesis, purpose, research questions, hypotheses, methods, evidence, key findings, major conclusions, tone, and publication information. Depending on your writing context, some of these items may not be applicable.

Questions to Consider

To evaluate a source, consider some of the following questions. They are broken down into different categories, but answering these questions will help you consider what areas to examine. With each category, we recommend identifying the strengths and weaknesses in each since that is a critical part of evaluation.

Evaluating Purpose and Argument

- How well is the purpose made clear in the introduction through background/context and thesis?

- How well does the abstract represent and summarize the article’s major points and argument?

- How well does the objective of the experiment or of the observation fill a need for the field?

- How well is the argument/purpose articulated and discussed throughout the body of the text?

- How well does the discussion maintain cohesion?

Evaluating the Presentation/Organization of Information

- How appropriate and clear is the title of the article?

- Where could the author have benefited from expanding, condensing, or omitting ideas?

- How clear are the author’s statements? Challenge ambiguous statements.

- What underlying assumptions does the author have, and how does this affect the credibility or clarity of their article?

- How objective is the author in his or her discussion of the topic?

- How well does the organization fit the article’s purpose and articulate key goals?

Evaluating Methods

- How appropriate are the study design and methods for the purposes of the study?

- How detailed are the methods being described? Is the author leaving out important steps or considerations?

- Have the procedures been presented in enough detail to enable the reader to duplicate them?

Evaluating Data

- Scan and spot-check calculations. Are the statistical methods appropriate?

- Do you find any content repeated or duplicated?

- How many errors of fact and interpretation does the author include? (You can check on this by looking up the references the author cites).

- What pertinent literature has the author cited, and have they used this literature appropriately?

Following, we have an example of a summary and an evaluation of a research article. Note that in most literature review contexts, the summary and evaluation would be much shorter. This extended example shows the different ways a student can critique and write about an article.

Chik, A. (2012). Digital gameplay for autonomous foreign language learning: Gamers’ and language teachers’ perspectives. In H. Reinders (ed.), Digital games in language learning and teaching (pp. 95-114). Eastbourne, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Be sure to include the full citation either in a reference page or near your evaluation if writing an annotated bibliography .

In Chik’s article “Digital Gameplay for Autonomous Foreign Language Learning: Gamers’ and Teachers’ Perspectives”, she explores the ways in which “digital gamers manage gaming and gaming-related activities to assume autonomy in their foreign language learning,” (96) which is presented in contrast to how teachers view the “pedagogical potential” of gaming. The research was described as an “umbrella project” consisting of two parts. The first part examined 34 language teachers’ perspectives who had limited experience with gaming (only five stated they played games regularly) (99). Their data was recorded through a survey, class discussion, and a seven-day gaming trial done by six teachers who recorded their reflections through personal blog posts. The second part explored undergraduate gaming habits of ten Hong Kong students who were regular gamers. Their habits were recorded through language learning histories, videotaped gaming sessions, blog entries of gaming practices, group discussion sessions, stimulated recall sessions on gaming videos, interviews with other gamers, and posts from online discussion forums. The research shows that while students recognize the educational potential of games and have seen benefits of it in their lives, the instructors overall do not see the positive impacts of gaming on foreign language learning.

The summary includes the article’s purpose, methods, results, discussion, and citations when necessary.

This article did a good job representing the undergraduate gamers’ voices through extended quotes and stories. Particularly for the data collection of the undergraduate gamers, there were many opportunities for an in-depth examination of their gaming practices and histories. However, the representation of the teachers in this study was very uneven when compared to the students. Not only were teachers labeled as numbers while the students picked out their own pseudonyms, but also when viewing the data collection, the undergraduate students were more closely examined in comparison to the teachers in the study. While the students have fifteen extended quotes describing their experiences in their research section, the teachers only have two of these instances in their section, which shows just how imbalanced the study is when presenting instructor voices.

Some research methods, like the recorded gaming sessions, were only used with students whereas teachers were only asked to blog about their gaming experiences. This creates a richer narrative for the students while also failing to give instructors the chance to have more nuanced perspectives. This lack of nuance also stems from the emphasis of the non-gamer teachers over the gamer teachers. The non-gamer teachers’ perspectives provide a stark contrast to the undergraduate gamer experiences and fits neatly with the narrative of teachers not valuing gaming as an educational tool. However, the study mentioned five teachers that were regular gamers whose perspectives are left to a short section at the end of the presentation of the teachers’ results. This was an opportunity to give the teacher group a more complex story, and the opportunity was entirely missed.

Additionally, the context of this study was not entirely clear. The instructors were recruited through a master’s level course, but the content of the course and the institution’s background is not discussed. Understanding this context helps us understand the course’s purpose(s) and how those purposes may have influenced the ways in which these teachers interpreted and saw games. It was also unclear how Chik was connected to this masters’ class and to the students. Why these particular teachers and students were recruited was not explicitly defined and also has the potential to skew results in a particular direction.

Overall, I was inclined to agree with the idea that students can benefit from language acquisition through gaming while instructors may not see the instructional value, but I believe the way the research was conducted and portrayed in this article made it very difficult to support Chik’s specific findings.

Some professors like you to begin an evaluation with something positive but isn’t always necessary.

The evaluation is clearly organized and uses transitional phrases when moving to a new topic.

This evaluation includes a summative statement that gives the overall impression of the article at the end, but this can also be placed at the beginning of the evaluation.

This evaluation mainly discusses the representation of data and methods. However, other areas, like organization, are open to critique.

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Critical Reviews

How to Write an Article Review (With Examples)

Last Updated: April 24, 2024 Fact Checked

Preparing to Write Your Review

Writing the article review, sample article reviews, expert q&a.

This article was co-authored by Jake Adams . Jake Adams is an academic tutor and the owner of Simplifi EDU, a Santa Monica, California based online tutoring business offering learning resources and online tutors for academic subjects K-College, SAT & ACT prep, and college admissions applications. With over 14 years of professional tutoring experience, Jake is dedicated to providing his clients the very best online tutoring experience and access to a network of excellent undergraduate and graduate-level tutors from top colleges all over the nation. Jake holds a BS in International Business and Marketing from Pepperdine University. There are 12 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 3,100,459 times.

An article review is both a summary and an evaluation of another writer's article. Teachers often assign article reviews to introduce students to the work of experts in the field. Experts also are often asked to review the work of other professionals. Understanding the main points and arguments of the article is essential for an accurate summation. Logical evaluation of the article's main theme, supporting arguments, and implications for further research is an important element of a review . Here are a few guidelines for writing an article review.

Education specialist Alexander Peterman recommends: "In the case of a review, your objective should be to reflect on the effectiveness of what has already been written, rather than writing to inform your audience about a subject."

Article Review 101

- Read the article very closely, and then take time to reflect on your evaluation. Consider whether the article effectively achieves what it set out to.

- Write out a full article review by completing your intro, summary, evaluation, and conclusion. Don't forget to add a title, too!

- Proofread your review for mistakes (like grammar and usage), while also cutting down on needless information.

- Article reviews present more than just an opinion. You will engage with the text to create a response to the scholarly writer's ideas. You will respond to and use ideas, theories, and research from your studies. Your critique of the article will be based on proof and your own thoughtful reasoning.

- An article review only responds to the author's research. It typically does not provide any new research. However, if you are correcting misleading or otherwise incorrect points, some new data may be presented.

- An article review both summarizes and evaluates the article.

- Summarize the article. Focus on the important points, claims, and information.

- Discuss the positive aspects of the article. Think about what the author does well, good points she makes, and insightful observations.

- Identify contradictions, gaps, and inconsistencies in the text. Determine if there is enough data or research included to support the author's claims. Find any unanswered questions left in the article.

- Make note of words or issues you don't understand and questions you have.

- Look up terms or concepts you are unfamiliar with, so you can fully understand the article. Read about concepts in-depth to make sure you understand their full context.

- Pay careful attention to the meaning of the article. Make sure you fully understand the article. The only way to write a good article review is to understand the article.

- With either method, make an outline of the main points made in the article and the supporting research or arguments. It is strictly a restatement of the main points of the article and does not include your opinions.

- After putting the article in your own words, decide which parts of the article you want to discuss in your review. You can focus on the theoretical approach, the content, the presentation or interpretation of evidence, or the style. You will always discuss the main issues of the article, but you can sometimes also focus on certain aspects. This comes in handy if you want to focus the review towards the content of a course.

- Review the summary outline to eliminate unnecessary items. Erase or cross out the less important arguments or supplemental information. Your revised summary can serve as the basis for the summary you provide at the beginning of your review.

- What does the article set out to do?

- What is the theoretical framework or assumptions?

- Are the central concepts clearly defined?

- How adequate is the evidence?

- How does the article fit into the literature and field?

- Does it advance the knowledge of the subject?

- How clear is the author's writing? Don't: include superficial opinions or your personal reaction. Do: pay attention to your biases, so you can overcome them.

- For example, in MLA , a citation may look like: Duvall, John N. "The (Super)Marketplace of Images: Television as Unmediated Mediation in DeLillo's White Noise ." Arizona Quarterly 50.3 (1994): 127-53. Print. [9] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- For example: The article, "Condom use will increase the spread of AIDS," was written by Anthony Zimmerman, a Catholic priest.

- Your introduction should only be 10-25% of your review.

- End the introduction with your thesis. Your thesis should address the above issues. For example: Although the author has some good points, his article is biased and contains some misinterpretation of data from others’ analysis of the effectiveness of the condom.

- Use direct quotes from the author sparingly.

- Review the summary you have written. Read over your summary many times to ensure that your words are an accurate description of the author's article.

- Support your critique with evidence from the article or other texts.

- The summary portion is very important for your critique. You must make the author's argument clear in the summary section for your evaluation to make sense.

- Remember, this is not where you say if you liked the article or not. You are assessing the significance and relevance of the article.

- Use a topic sentence and supportive arguments for each opinion. For example, you might address a particular strength in the first sentence of the opinion section, followed by several sentences elaborating on the significance of the point.

- This should only be about 10% of your overall essay.

- For example: This critical review has evaluated the article "Condom use will increase the spread of AIDS" by Anthony Zimmerman. The arguments in the article show the presence of bias, prejudice, argumentative writing without supporting details, and misinformation. These points weaken the author’s arguments and reduce his credibility.

- Make sure you have identified and discussed the 3-4 key issues in the article.

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://libguides.cmich.edu/writinghelp/articlereview

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4548566/

- ↑ Jake Adams. Academic Tutor & Test Prep Specialist. Expert Interview. 24 July 2020.

- ↑ https://guides.library.queensu.ca/introduction-research/writing/critical

- ↑ https://www.iup.edu/writingcenter/writing-resources/organization-and-structure/creating-an-outline.html

- ↑ https://writing.umn.edu/sws/assets/pdf/quicktips/titles.pdf

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/mla_style/mla_formatting_and_style_guide/mla_works_cited_periodicals.html

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4548565/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/593/2014/06/How_to_Summarize_a_Research_Article1.pdf

- ↑ https://www.uis.edu/learning-hub/writing-resources/handouts/learning-hub/how-to-review-a-journal-article

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/editing-and-proofreading/

About This Article

If you have to write an article review, read through the original article closely, taking notes and highlighting important sections as you read. Next, rewrite the article in your own words, either in a long paragraph or as an outline. Open your article review by citing the article, then write an introduction which states the article’s thesis. Next, summarize the article, followed by your opinion about whether the article was clear, thorough, and useful. Finish with a paragraph that summarizes the main points of the article and your opinions. To learn more about what to include in your personal critique of the article, keep reading the article! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Prince Asiedu-Gyan

Apr 22, 2022

Did this article help you?

Sammy James

Sep 12, 2017

Juabin Matey

Aug 30, 2017

Vanita Meghrajani

Jul 21, 2016

Nov 27, 2018

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

- Submit your Research

- My Submissions

- Article Guidelines

- Article Guidelines (New Versions)

- Data Guidelines

- Posters and Slides Guidelines

- Document Guidelines

- Article Processing Charges

- Peer Review

- The Peer Review Process

- The Editorial Team’s Role

- Understanding Peer Review Reports and Statuses

- Revising and Responding to Reviewers

Finding Article Reviewers

- Reviewer Criteria

- Hints and Tips for Finding Reviewers

- Dos and Don’ts for Suggesting Reviewers

- Identity transparency: All identities visible

- Reviewer interacts with: Editor, other reviewers, authors

- Review information published: Review reports, submitted manuscript, reviewer identities

- Post publication commenting: Open

- Qualified: Reviewers should typically hold a doctorate (PhD/MD/MBBS or equivalent). Exceptions will be made for scholarly disciplines where doctorates are not necessary (e.g. Education, Library Science), or when an individual has a demonstrable public record of expertise. If possible, when a reviewer suggestion is rejected due to lack of qualifications, the editorial team will suggest that their Principal Investigator/Supervisor is invited instead, and the original person could then take the role of co-reviewer.

- Expert: Reviewers should have published at least three articles as lead author in a relevant topic, with at least one article having been published in the last five years . In fields where a reviewer’s expertise is not typically measured by their publication record or if the suggested reviewer’s expertise is demonstrable in ways other than their publication record, please provide an explanation of their suitability.

- have co-authored with any of the lead authors in the three years preceding publication of Version 1;

- have co-authored with any of the lead authors since the publication of Version 1;

- currently work at the same institution as the authors;

- be a close collaborator with an author.

- Global: For any given article, we require that reviewers are from different institutions . (This does not apply to large, multi-site institutions, such as Max-Planck Institutes or University of California). We also strongly encourage that geographically-diverse reviewers are invited to review, to gain an international perspective on the article. In cases where we receive multiple reviewer suggestions from the same country, the editorial team can only invite one of these reviewers at a time. Providing a geographically-diverse set of reviewers will help to prevent delays to the peer review process.

- Use the authors of the references cited in your article as a starting point for finding reviewers working in your specific field.

- Search abstracting and indexing databases such as Google Scholar , PubMed , Web of Science * and Scopus * (or other subject-specific literature databases) for recent articles with specific keywords can help you to identify authors currently working in the same field as yourself, and who may be suitable to review your article. As an expert in your area of research, you will likely be aware of prominent laboratories whose staff may be suitable to review your articles - try searching their website for potential reviewers. You can also search for specific experts with whom you have no recent collaborations, as they or their postdocs may be suitable to review.

- Try the Journal/Author Name Estimator and other similar tools can help to identify authors who have published related articles.

- Use our Reviewer Finder Tool. This tool analyzes the submission and provides a ranked list of reviewer candidates based on leading authors of related published studies. Authors can access this tool via the 'Suggest Reviewers' link next to submitted and published articles in the Submissions section in My Research . As this is an automatically generated list of potential reviewers, authors must use their own judgement to determine if the suggested reviewers have the appropriate expertise to review the article.

- Make sure suggested reviewers are experts in the relevant subject area F1000Research will only invite reviewers who have expertise in the field of research covered by the article. Not only does this ensure thorough peer review, but also reviewers are more likely to agree to provide a report when the subject matter is close to their own area of expertise.

- Try and ensure a global spread of reviewers For any given article, the reviewers must come from separate institutions and should not be affiliated with the authors’ institutions. We also strongly encourage that reviewers from around the world are invited to review where possible so that a global perspective can be gained for the article, and to ensure that all aspects of the work are reviewed.

- Ensure reviewers from the algorithm are suitable before approving them To provide authors who wish to suggest reviewers with a shortlist, each article is scanned by our Reviewer Finder Tool, which automatically provides a list of researchers who have published related articles. Authors can suggest appropriate reviewers from this automatically generated list (which can be accessed via the ‘Suggest Reviewers’ link next to your submitted or published article in My Research ), but must use their own judgement to determine if the suggested reviewers have the appropriate expertise to review the article.

- Discuss with your co-authors It may be that your co-authors would like to suggest reviewers – only the submitting author is able to provide these, however we welcome suggestions on your other authors’ behalfs. We would also be happy to change the submitting author so that a co-author can submit reviewers directly, please contact the editorial team if you wish to do this.

- Contact us if you have any questions If we have rejected a reviewer who you believe to be suitable, or if you have any questions or concerns about our reviewer criteria, we are always happy to discuss. Please email us so that we can explore possible options.

- Suggest reviewers who have recently closely collaborated with you or your co-authors We consider this to be a potential conflict of interest. A reviewer should not be based at the same institution as any author, be a close collaborator, or have co-authored with any of the lead authors for three years before the publication of the article. Please note that we make exceptions for cases where researchers have published together on the findings or consensus from a large consortia.

- Suggest reviewers who do not have the right expertise The editorial team will not invite reviewers who do not appear to have appropriate expertise. Suggesting inappropriate reviewers can cause significant delays to the peer review process.

- Contact the reviewers directly To ensure a fair peer review process is maintained, the editorial team acts as the intermediary between authors and reviewers. By directly contacting the reviewers, authors could not only influence their assessment of the article, but could also dissuade them from reviewing. Please be aware that if evidence of an author coercing reviewers is brought to our attention, we will investigate and take appropriate action. Authors can respond to a peer review report by posting a comment under the report.

The email address should be the one you originally registered with F1000.

You registered with F1000 via Google, so we cannot reset your password.

To sign in, please click here .

If you still need help with your Google account password, please click here .

You registered with F1000 via Facebook, so we cannot reset your password.

If you still need help with your Facebook account password, please click here .

If your email address is registered with us, we will email you instructions to reset your password.

If you think you should have received this email but it has not arrived, please check your spam filters and/or contact for further assistance.

Browse Econ Literature

- Working papers

- Software components

- Book chapters

- JEL classification

More features

- Subscribe to new research

RePEc Biblio

Author registration.

- Economics Virtual Seminar Calendar NEW!

How to Undertake an Impactful Literature Review: Understanding Review Approaches and Guidelines for High-impact Systematic Literature Reviews

- Author & abstract

- Related works & more

Corrections

- Amrita Chakraborty

- Arpan Kumar Kar

Suggested Citation

Download full text from publisher.

Follow serials, authors, keywords & more

Public profiles for Economics researchers

Various research rankings in Economics

RePEc Genealogy

Who was a student of whom, using RePEc

Curated articles & papers on economics topics

Upload your paper to be listed on RePEc and IDEAS

New papers by email

Subscribe to new additions to RePEc

EconAcademics

Blog aggregator for economics research

Cases of plagiarism in Economics

About RePEc

Initiative for open bibliographies in Economics

News about RePEc

Questions about IDEAS and RePEc

RePEc volunteers

Participating archives

Publishers indexing in RePEc

Privacy statement

Found an error or omission?

Opportunities to help RePEc

Get papers listed

Have your research listed on RePEc

Open a RePEc archive

Have your institution's/publisher's output listed on RePEc

Get RePEc data

Use data assembled by RePEc

This paper is in the following e-collection/theme issue:

Published on 10.5.2024 in Vol 10 (2024)

Community Engagement in Vaccination Promotion: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Authors of this article:

- Yao Jie Xie 1, 2 * , PhD ;

- Xiaoli Liao 1 * , PhD ;

- Meijuan Lin 1 , MM ;

- Lin Yang 1 , PhD ;

- Kin Cheung 1 , PhD ;

- Qingpeng Zhang 3, 4 , PhD ;

- Yan Li 1 , PhD ;

- Chun Hao 5 , PhD ;

- Harry HX Wang 5, 6 , PhD ;

- Yang Gao 7 , PhD ;

- Dexing Zhang 8 , PhD ;

- Alex Molassiotis 9 , PhD ;

- Gilman Kit Hang Siu 10 , PhD ;

- Angela Yee Man Leung 1, 11 , PhD

1 School of Nursing, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China (Hong Kong)

2 Research Centre for Chinese Medicine Innovation, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China (Hong Kong)

3 Musketeers Foundation Institute of Data Science, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China (Hong Kong)

4 Department of Pharmacology and Pharmacy, LKS Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China (Hong Kong)

5 School of Public Health, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

6 Usher Institute, Deanery of Molecular, Genetic & Population Health Sciences, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

7 Department of Sport, Physical Education and Health, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong, China (Hong Kong)

8 JC School of Public Health and Primary Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China (Hong Kong)

9 Health and Social Care Research Centre, University of Derby, Derby, United Kingdom

10 Department of Health Technology and Informatics, Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China (Hong Kong)

11 Research Institute on Smart Aging (RISA), The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China (Hong Kong)

*these authors contributed equally

Corresponding Author:

Yao Jie Xie, PhD

School of Nursing

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University

11 Yuk Choi Road

Hung Hom, Kowloon

China (Hong Kong)

Phone: 852 34003798

Fax:852 23649663

Email: [email protected]

Background: Community engagement plays a vital role in global immunization strategies, offering the potential to overcome vaccination hesitancy and enhance vaccination confidence. Although there is significant backing for community engagement in health promotion, the evidence supporting its effectiveness in vaccination promotion is fragmented and of uncertain quality.

Objective: This review aims to systematically examine the effectiveness of different contents and extent of community engagement for promoting vaccination rates.

Methods: This study was performed in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. A comprehensive and exhaustive literature search was performed in 4 English databases (PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library) and 2 Chinese databases (CNKI and Wan Fang) to identify all possible articles. Original research articles applying an experimental study design that investigated the effectiveness of community engagement in vaccination promotion were eligible for inclusion. Two reviewers independently performed the literature search, study selection, quality assessment, and data extraction. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion, with the arbitration of a third reviewer where necessary.

Results: A total of 20 articles out of 11,404 records from 2006 to 2021 were retrieved. The studies used various designs: 12 applied single-group pre-post study designs, 5 were cluster randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and 3 were non-RCTs. These studies targeted multiple vaccines, with 8 focusing on children’s immunization, 8 on human papillomavirus vaccine, 3 on hepatitis B virus vaccine, and 1 on COVID-19 vaccine. The meta-analysis revealed significant increases in vaccination rates both in pre-post comparison (rate difference [RD] 0.34, 95% CI 0.21-0.47, I 2 =99.9%, P <.001) and between-group comparison (RD 0.18, 95% CI 0.07-0.29, I 2 =98.4%, P <.001). The meta-analysis revealed that participant recruitment had the largest effect size (RD 0.51, 95% CI 0.36-0.67, I 2 =99.9%, P <.001), followed by intervention development (RD 0.36, 95% CI 0.23-0.50, I 2 =100.0%, P <.001), intervention implementation (RD 0.35, 95% CI 0.22-0.47, I 2 =99.8%, P <.001), and data collection (RD 0.34, 95% CI 0.19-0.50, I 2 =99.8%, P <.001). The meta-analysis indicated that high community engagement extent yielded the largest effect size (RD 0.49, 95% CI 0.17-0.82, I 2 =100.0%, P <.001), followed by moderate community engagement extent (RD 0.45, 95% CI 0.33-0.58, I 2 =99.6%, P <.001) and low community engagement extent (RD 0.15, 95% CI 0.05-0.25, I 2 =99.2%, P <.001). The meta-analysis revealed that “health service support” demonstrated the largest effect sizes (RD 0.45, 95% CI 0.25-0.65, I 2 =99.9%, P <.001), followed by “health education and discussion” (RD 0.39, 95% CI 0.20-0.58, I 2 =99.7%, P <.001), “follow-up and reminder” (RD 0.33, 95% CI 0.23-0.42, I 2 =99.3%, P <.001), and “social marketing campaigns and community mobilization” (RD 0.24, 95% CI 0.06-0.41, I 2 =99.9%, P <.001).

Conclusions: The results of this meta-analysis supported the effectiveness of community engagement in vaccination promotion with variations in terms of engagement contents and extent. Community engagement required a “fit-for-purpose” approach rather than a “one-size-fits-all” approach to maximize the effectiveness of vaccine promotion.

Trial Registration: PROSPERO CRD42022339081; https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=339081

Introduction

Vaccination stands as one of the top 10 great public health achievements of the last century. It has made significant strides in eliminating and controlling various vaccine-preventable diseases, as evidenced by the reduction in morbidity, mortality, and disability caused by these diseases [ 1 , 2 ]. A notable illustration is the use of vaccines as a crucial measure to mitigate the COVID-19 pandemic in the past 3 years [ 3 , 4 ]. A previous study analyzed the economic advantages of vaccination against 10 diseases across 73 countries from 2001 to 2020. It reported that vaccinations have prevented over 20 million deaths and saved approximately US $350 billion in disease costs [ 5 ]. A modeling study examined the health implications of vaccination against 10 pathogens across 98 countries from 2000 to 2030. It revealed that vaccinations have prevented 69 million deaths [ 6 ].

Both the Global Vaccine Action Plan 2011-2020 and Immunization Agenda 2030 have established strategic objectives to immunize every eligible individual with appropriate vaccines and to ensure equitable coverage of immunization benefits for all. However, the immunization coverage of many vaccines has yet to reach the expected level. For instance, between 2006 and 2014, only 47 million women across 80 countries and territories received the full course of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines, representing a mere 1.4% coverage of the total female population [ 7 ]. In addition, a study assessing the coverage of childhood vaccines across 1366 administrative regions in 43 countries revealed that only one-third of children in 4 countries had fully received routine childhood vaccines [ 8 ]. In terms of adult vaccination, only 11 out of 204 countries achieved the World Health Organization (WHO) target of 90% coverage for 11 routine vaccines by 2019 [ 9 ]. Various reasons and barriers contribute to the lack of vaccination, with a significant obstacle being vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy has been steadily rising worldwide over the past decade [ 10 , 11 ], emerging as one of the top 10 threats to global health listed by the WHO in 2019.

Community engagement is a process that involves engaging and motivating diverse partners to collaborate in harnessing community potential and enhancing community health [ 12 , 13 ]. It first gained prominence in the public health sphere with the Declaration of Alma-Ata and has since become increasingly prominent, particularly with the introduction of the new Sustainable Development Goals [ 14 ]. The WHO defines community engagement as “a process of developing relationship which enables stakeholders work together to address health issues” [ 15 ]. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) defines community engagement as “an action for working with community stakeholders to improve community health” [ 13 ]. The definition of community engagement often intersects, competes with, and contradicts definitions of other terms such as community participation and community involvement, among others. Despite the extensive literature on community engagement, there is a lack of comprehensive guidelines to clarify the content and scope of community engagement, including what constitutes community engagement and the extent of its involvement. The levels of community engagement are structured along a continuum that spans from informing and consulting to involving, collaborating, and empowering [ 16 , 17 ]. The elements of community engagement manifest across a spectrum of initiatives, encompassing participant recruitment, intervention development, intervention implementation, and data collection [ 18 , 19 ]. Community engagement is characterized as a dynamic process rather than a singular intervention, operating within diverse contexts to address various issues through multiple mechanisms involving different actors.

A meta-analysis, incorporating 131 individual studies, supported the positive impact of community engagement on health and psychosocial outcomes for disadvantaged groups across various conditions [ 20 ]. It plays a prominent role in global immunization strategies, as it has the capacity to alleviate vaccination hesitancy and enhance vaccination confidence. A systematic review, which included 14 studies, examined the effectiveness of community interventions on HPV vaccine coverage. Of these, 12 studies reported that community interventions led to an increase in the uptake of the HPV vaccine [ 21 ]. Another review, spanning across 19 countries, assessed studies indicating that community engagement enhanced the timeliness and coverage of routine childhood immunization vaccines [ 22 ]. Despite robust evidence supporting the role of community engagement in promoting health within diverse populations, the evidence for community engagement specifically in vaccination promotion remains fragmented. Thus, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the effectiveness of various aspects and levels of community engagement in enhancing vaccination rates.

This study was conducted following the guidelines outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [ 23 ], and the results were reported following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [ 24 ]. The review protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42022339081). Two reviewers (ML and YJX) conducted the literature search, study selection, quality assessment, and data extraction independently. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion, and a third reviewer (LY) was consulted for arbitration when necessary.

Ethics Approval

This review paper was a secondary analysis of existing data from original studies published before, rather than a direct collection of new data, and thus, does not require ethical approval.

Search Strategies

A comprehensive and exhaustive literature search was conducted across 4 English databases (PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library), as well as 2 Chinese databases (CNKI and Wan Fang).

The search strategy involved combining terms related to “community engagement” and “vaccination” using specific vocabulary terms (MeSH and Emtree) and their corresponding free-text terms [ 25 , 26 ]. These terms were identified based on key publications in relevant fields, and the search strategy was adjusted to suit each database. Boolean operators, specifically “OR” between terms and “AND” between concepts, were used to combine search terms effectively.

No restrictions were placed on language, study design, country of origin, or publication date. Studies were searched in the selected databases from their inception to April 30, 2023. The initial literature searches were performed in June 2022, with an updated search conducted in April 2023. In addition, the reference lists of relevant articles and previous reviews were manually reviewed to identify any additional relevant studies. The ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Database was consulted to identify unpublished dissertations and theses. Furthermore, Google and Google Scholar were searched to identify gray literature for potential inclusion. Clinical trial registries, including ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry, were also searched to identify trials with outcomes that had not yet been published.

Details of the full search strategy for each database are listed in Table S1 in Multimedia Appendix 1 .

Selection Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were established based on the participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design (PICOS) strategy [ 27 ]. Initially, these criteria were applied to titles and abstracts, and subsequently to full-text articles, to determine their final inclusion status ( Table 1 ).

All records retrieved from the literature search were imported into the bibliographic database EndNote (Clarivate), which was used to manage records and eliminate duplicates. Two reviewers (ML and XL) independently screened the records based on the eligibility criteria. Any discrepancies between the 2 reviewers were resolved through discussion, and a third reviewer (YJX) was consulted if consensus could not be reached. The search terms and selection criteria were designed to provide inclusive flexibility and discretion, considering the various permutations of community engagement.

Data Extraction

A data extraction form was developed and piloted on 6 randomly selected sample studies to establish consensus on the data abstraction procedures. Subsequently, 2 independent investigators (ML and XL) extracted information including the first author, publication year, study design, country, participant number, intervention details, control condition, vaccine rates, and effect size of the intervention, where reported. In cases where a study provided data for both vaccine series initiation and completion, only the latter was included in the summary table. If a study evaluated multiple vaccine types and reported a combined vaccination rate, that result was selected; otherwise data for the primary vaccine under focus were presented. In instances where a study reported incomplete data, the authors were contacted via email to obtain the required information.

Assessment of the Risk of Bias

The revised Cochrane Tool for Risk of Bias 2.0 (RoB2) was used to assess the risk of bias in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [ 33 ]. For nonrandomized trials and controlled pre-post studies, the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies-of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool was used to evaluate the risk of bias [ 34 ].

Each study was assessed and categorized as having low, moderate, or high risk of bias for each domain. Studies with low risk in 3 or more domains and moderate risk in any remaining domain(s) were classified as having an overall low risk of bias. Studies with moderate risk in 3 or more domains and low or unclear risk in any remaining domain(s) were classified as having an overall moderate risk of bias. Studies with high risk in 3 or more domains and moderate risk in any remaining domain(s) were classified as having an overall high risk of bias. Studies with moderate risk in 3 or more domains and high risk in any remaining domain(s) were also classified as having an overall high risk of bias.

Data Synthesis