What is desertification and why is it important to understand?

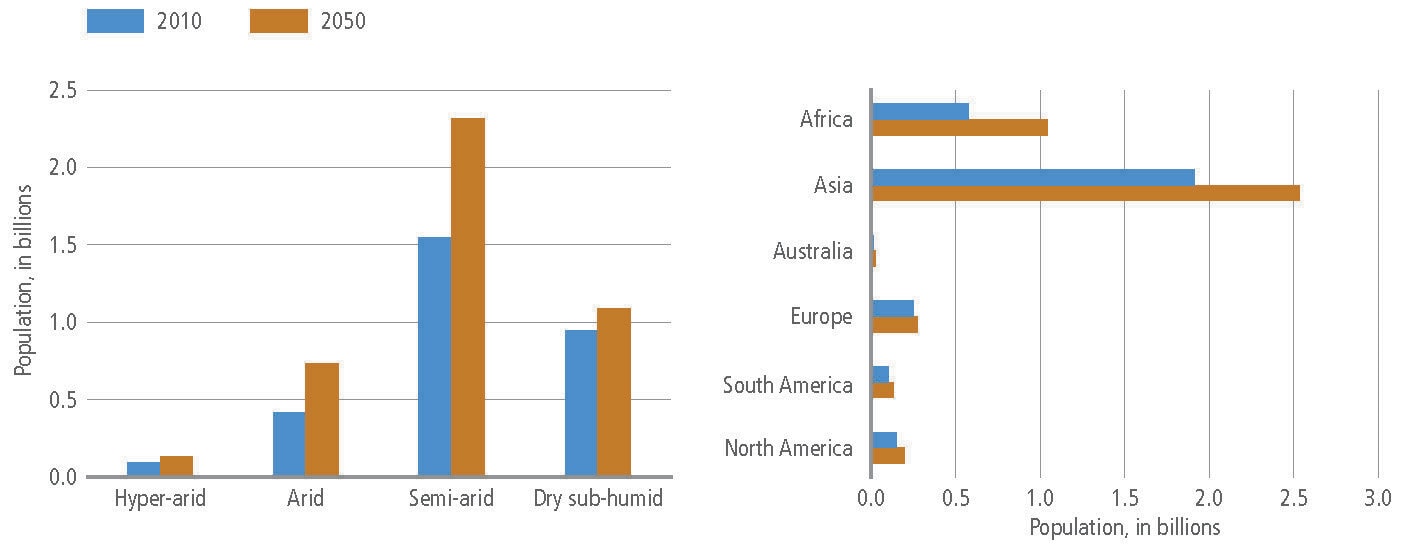

Currently, around 2 billion people live in drylands, which are most prone to desertification, according to Earth.org. Image: REUTERS/Ivan Alvarado

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Andrea Willige

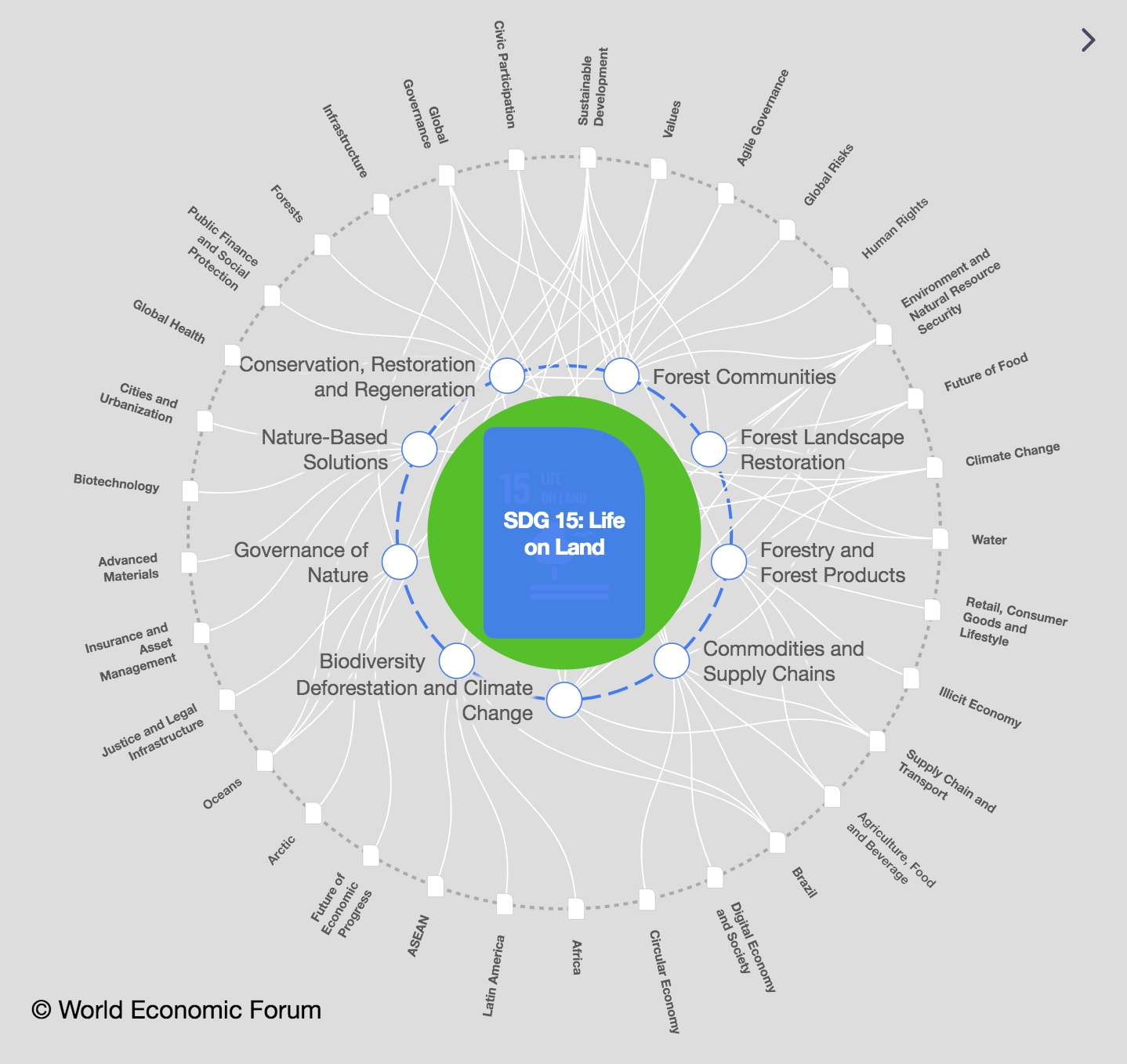

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} SDG 15: Life on Land is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, sdg 15: life on land.

- Factors including climate change, deforestation, overgrazing and unsustainable agricultural practices are increasingly turning our world’s drylands into deserts.

- Degradation of productive soil along with the loss of biodiversity, bodies of water and vegetation also impacts human life, leading to poverty, food and water scarcity and poor health.

- But 2024 could become a seminal year for the fight against desertification, with a series of events including the World Economic Forum’s Special Meeting and COP16 focused on tackling the issue.

When we think of deserts, regions such as the Middle East, Northern Africa or Central Asia may spring to mind. But growing desertification in the wake of climate change is increasingly drawing ever wider circles across the globe, increasing steadily . United Nations’ latest data, as presented by 126 Parties in their 2022 national reports, show that 15.5% of land is now degraded, an increase of 4% in as many years.

But this could become a seminal year for the fight against desertification, with two major events scheduled for 2024 in Saudi Arabia to mobilize support. Tackling this growing problem will be a major focus at the World Economic Forum’s forthcoming Special Meeting on Global Collaboration, Growth and Energy for Development in May, and the16th session of the Conference of the Parties to the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) COP16 in December.

The UNCCD is one of the three Rio Conventions, along with the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Convention on Biological Diversity.

What does desertification mean for our planet and people, and how can we mitigate against it?

Have you read?

These start-ups are helping to make life in the sahel more sustainable, why investing in land is a business imperative for a sustainable future, women's land rights: a key to combating desertification and drought, what is desertification and what causes it.

Desertification is a type of land degradation in which an already relatively dry land area becomes increasingly arid , degrading productive soil and losing its bodies of water, biodiversity and vegetation cover.

It is driven by a combination of factors, including climate change, deforestation, overgrazing and unsustainable agricultural practices .

The issue reaches far beyond deserts like the Sahara, Kalahari or Gobi deserts. The UNCCD says that 100 million hectares of productive land are degraded each year . Droughts are becoming more common, and three-quarters of people are expected to face water scarcity by 2050.

Currently, around 2 billion people live in drylands, which are most prone to desertification , according to Earth.org.

Among the most affected regions are Africa and Eastern and Central Asia.

Who is most affected by desertification?

In Africa, some 40 million people are living in severe drought conditions already , according to the World Economic Forum report Quantifying the Impact of Climate Change on Human Health 2024.

And, in Asia, China, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan are among the countries that have seen temperatures soaring, according to Earth.org. While some of these areas had been classed as having a desert climate since the 1980s, desertification has continued, leading to hotter, wetter climates. In the mountains, a lack of snow has led to the gradual disappearance of glaciers, threatening water security that affects both people and agriculture.

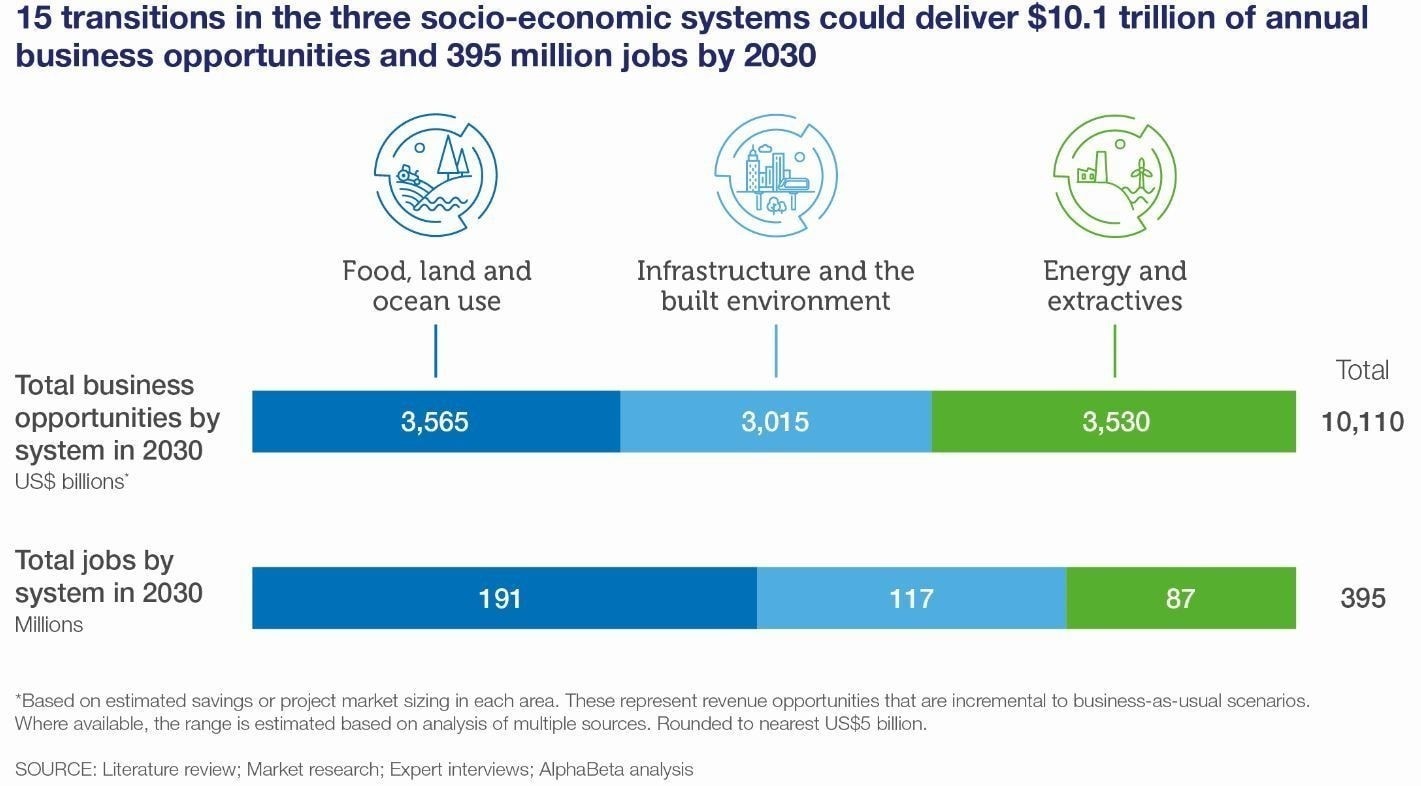

Biodiversity loss and climate change are occurring at unprecedented rates, threatening humanity’s very survival. Nature is in crisis, but there is hope. Investing in nature can not only increase our resilience to socioeconomic and environmental shocks, but it can help societies thrive.

There is strong recognition within the Forum that the future must be net-zero and nature-positive. The Nature Action Agenda initiative, within the Centre for Nature and Climate , is an inclusive, multistakeholder movement catalysing economic action to halt biodiversity loss by 2030.

The Nature Action Agenda is enabling business and policy action by:

Building a knowledge base to make a compelling economic and business case for safeguarding nature, showcasing solutions and bolstering research through the publication of the New Nature Economy Reports and impactful communications.

Catalysing leadership for nature-positive transitions through multi-stakeholder communities such as Champions for Nature that takes a leading role in shaping the net-zero, nature-positive agenda on the global stage.

Scaling up solutions in priority socio-economic systems through BiodiverCities by 2030 , turning cities into engines of nature-positive development; Financing for Nature , unlocking financial resources through innovative mechanisms such as high-integrity Biodiversity Credits Market ; and Sector Transitions to Nature Positive , accelerating sector-specific priority actions to reduce impacts and unlock opportunities.

Supporting an enabling environment by ensuring implementation of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and mobilizing business voices calling for ambitious policy actions in collaboration with Business for Nature .

But land degradation also affects more temperate regions. In the US, nearly 40% of the lower 48 states are facing drought, the Forum’s report says, quoting statistics from the US National Integrated Drought Information System.

Southern Europe has seen some of its worst droughts in recent years. In Spain, desertification and overexploitation have severely affected what’s known as “Europe’s kitchen garden”. The European Union has flagged the vulnerability of its southern members to desertification in recent years, pointing not only to Spain but also Portugal, Italy, Greece, Cyprus, Bulgaria and Romania.

What are the impacts of desertification?

According to the UNCCD, around 500 million people live in desertified areas .

They can experience exacerbated poverty, lack of food security and poor health due to malnutrition and lack of access to clean water. They are also more vulnerable to climate change and extreme weather such as droughts and natural disasters. With their livelihoods at stake and a greater risk of conflict over declining resources , they may also face forced migration.

One of the most prominent examples of desertification is the Aralkum desert in central Asia. In the 1960s, the area was covered by the fourth-largest lake in the world, the Aral Sea. Since then, it has shrunk to a tenth of its former size, with only three small, highly salty lakes remaining. In Soviet times, its waters were used for irrigating a semi-desert region to grow cotton, leading to a drop in water levels. Climate change added further impetus to this over time, turning the dry seabed into a salt-covered desert, leaving fishing boats stranded, rusting and livelihoods destroyed.

How can we mitigate against desertification?

There are a wide variety of approaches to address desertification , with many programmes underway around the globe.

Reforestation and afforestation can help revive degraded soil. In Uzbekistan, a regreening programme has planted trees and shrubs across one million hectares along the Aral desert. This includes the black saxual shrub, which is highly drought resistant and can fix salt and sand, stopping it from being swept up and carried inland by sandstorms.

In the Sahel and Sahara region in Africa, the “Great Green Wall” – launched in 2007 by the African Union – aims to restore plant life across 100 million hectares of degraded land. Involving 22 African countries, this initiative will revive the land, store more than 220 million tonnes of carbon and create 10 million jobs by 2030.

Another big part of tackling land degradation is introducing sustainable land management practices, ranging from agroforestry to sustainable grazing and can also improve crop yields and livelihoods.

Water management practices such as rainwater harvesting, drip-water irrigation and planting drought-resistant crops can address the impact of water scarcity.

Other remedial steps include re-vegetation and restoring natural habitats such as wetlands or entire river beds.

The World Economic Forum’s Special Meeting in Saudi Arabia will see a series of announcements and sessions on the topic of desertification, including support for Saudi Arabia as the host of COP16 and joint work between the Forum and Saudi Arabia to compile a programme for December’s event.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Climate Action .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Electric vehicles are key to the energy transition - but the switch must be sustainable. Here's why

Lisa Donahue and Vance Scott

April 28, 2024

Climate finance: What are debt-for-nature swaps and how can they help countries?

Kate Whiting

April 26, 2024

Beyond greenwashing: 5 key strategies for genuine sustainability in agriculture

Santiago Gowland

April 24, 2024

How Indigenous expertise is empowering climate action: A case study from Oceania

Amanda Young and Ginelle Greene-Dewasmes

April 23, 2024

Global forest restoration goals can be achieved with youth-led ecopreneurship

Agustin Rosello, Anali Bustos, Fernando Morales de Rueda, Jennifer Hong and Paula Sarigumba

The planet’s outlook is in our hands. Which future will we incentivize?

Carlos Correa

April 22, 2024

Desertification

Charney's hypothesis

There is a controversy about the advance of deserts in the world (1). There is a widespread belief that the Sahara desert is advancing into the Sahel region, for instance. The Sahel is a narrow band of West Africa between 15 -18 ° N, between the Sahara to the north and savannah (grass and open forest) and equatorial forest to the south. It extends from Senegal at the coast at about 15 ° W, across Mali and Niger, to about 15 ° E. It receives rainfall during a short but active wet season, from late June to mid September. It is covered by grassland and supports a pasture-based society which traditionally moved meridionally following the rains. Its northern limit may be defined by the 200 mm/a isohyet.

Is the Sahara extending into the Sahel? And if so, is this because of fluctuations of rainfall (total amount, rainfall intensity, duration of wet season, …) or is it largely the result of human activities, such as overgrazing or the removal of trees for firewood? There are also the questions: Do deserts create droughts? Do droughts create deserts? In other words, is there a positive climate feedback, which accelerates land degradation? A now classic paper by Jules Charney in 1975 (2) speculated that overgrazing in the Sahel leads to less vegetation, which raises the ground’s albedo, so that less solar radiation is absorbed and the Earth’s surface becomes cooler. It should be noted that the atmosphere above the Sahara experiences continues radiative cooling, because the dry air, free of clouds, absorbs very little of the longwave radiation upwelling from the ground. This radiative cooling is naturally compensated by subsidence heating, and the subsidence sustains the dry air, cloudlessness, and arid surface conditions. According Charney, overgrazing would enhance the radiative loss, which would foster subsidence within the troposphere, leading to drier conditions in the Sahel, and therefore less plant growth during the wet season. Less vegetation means a higher albedo. So we have positive feedback and a self-aggravating process, culminating in desertification, a process of land degradation that destroys its productivity. Charney’s hypothesis was supported by experiments with a very simple GCM, in which he changed the surface albedo from 20% to 30% (3).

The problem of overgrazing in the Sahel is as acute now as it was in the 1960's, yet there is no clear rainfall trend in the Sahel. The period 1930-'60 was slightly wetter than 1960-'90 in most parts of the Sahel. More significant than any trend is the occurrence of dry and wet periods, each lasting several years. The Sahel enjoyed a notably wet decade in the 1950’s, which was followed by a drought in the 70’s and 80’s (1). However, land productivity was fully recovered around 1990. So Charney's hypothesis cannot be confirmed.

To reject Charney's hypothesis, one needs to examine whether the albedo has really increased in the Sahel. Satellite-estimated albedo of the Sahel between 1983-1988 was about 35% in (dry) January and 31% in (wet) July, a difference of about 4%. The seasonal variation greatly exceeded any overall change during the period. This points to there being no irreversible change towards desert. It is concluded that the formation of desert is not a single self-aggravating process, but is complex, reflecting changes of both climate and human activities. There may be incomplete recovery after a dry period, or changes in the composition of the vegetation.

Desertification trends are evaluated by means of the ‘normalised difference vegetation index’ (NDVI). This index, based on satellite data, quantifies the amount of vegetation (1). It is a figure for the ‘green-ness’ of the surface, the ratio of the measured reflectances of red light (i.e. 0.55-0.68 micron wavelength) and near-infra-red (0.73-1.1) in solar radiation. NDVI is strongly correlated with the biological productivity of an area. In the Sahel there is close agreement of the shifts of NDVI and rainfall boundaries during 1980 - 1995, i.e. the NDVI/rainfall relationship remained about constant. In other words, there was no progressive ‘march’ of desert over more fertile areas, no one-way ratchet effect due to deserts causing droughts.

A question related to the question about deserts causing drought, is that of large lakes inducing rain. Nicholson et al. (1) mentioned proposals to flood the Kalahari desert of Botswana to increase the rainfall regionally. The topic was discussed indirectly in Notes 10.I and 10.J, where reasons are given for expecting no influence of forestation on rainfall, unless done over large areas; even then, the enhanced rainfall is insufficient to support the manmade forest.

A separate effect of desertification, apart from any possible influence on rainfall, is an increase of soil erosion and dust storms (4), as shown in Fig 1 . This shows the close relationship between rainfall and dust.

Fig 1 . The frequency of dust storms at Gao (in the Sahel), compared with annual rainfall anomalies (from (1), after (4)). The anomaly unit is the regionally averaged departure from the long-term mean, divided by the standard deviation. The dust occurrence is expressed in terms of the number of days when there is dust haze.

References

(1) Nicholson, S.E., C.J. Tucker and M.B. Ba 1998. Desertification, drought and surface vegetation: an example from the West African Sahel. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 79 , 815-29.

(2) Charney, J.G. 1975. Dynamics of deserts and drought in Sahel. Quart. J. Royal Meteor. Soc, 101 , 193-202.

(3) Xue, Y. and J. Shukla 1993. The influence of land surface properties on Sahel climate. J. Climate, 6 , 2232-45.

(4) N’Tchayi, M.G., J.J. Bertrand and S.E. Nicholson 1997. The diurnal and seasonal cycles of desert dust over Africa north of the equator. J. Appl. Meteor. 36 , 868-82.

New Research

What Really Turned the Sahara Desert From a Green Oasis Into a Wasteland?

10,000 years ago, this iconic desert was unrecognizable. A new hypothesis suggests that humans may have tipped the balance

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

Lorraine Boissoneault

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f2/94/f294516b-db3d-4f7b-9a60-ca3cd5f3d9b2/fbby1h_1.jpg)

When most people imagine an archetypal desert landscape—with its relentless sun, rippling sand and hidden oases—they often picture the Sahara. But 11,000 years ago, what we know today as the world’s largest hot desert would’ve been unrecognizable. The now-dessicated northern strip of Africa was once green and alive, pocked with lakes, rivers, grasslands and even forests. So where did all that water go?

Archaeologist David Wright has an idea: Maybe humans and their goats tipped the balance, kick-starting this dramatic ecological transformation. In a new study in the journal Frontiers in Earth Science , Wright set out to argue that humans could be the answer to a question that has plagued archaeologists and paleoecologists for years.

The Sahara has long been subject to periodic bouts of humidity and aridity. These fluctuations are caused by slight wobbles in the tilt of the Earth’s orbital axis, which in turn changes the angle at which solar radiation penetrates the atmosphere. At repeated intervals throughout Earth’s history , there’s been more energy pouring in from the sun during the West African monsoon season, and during those times—known as African Humid Periods—much more rain comes down over north Africa.

With more rain, the region gets more greenery and rivers and lakes. All this has been known for decades. But between 8,000 and 4,500 years ago, something strange happened: The transition from humid to dry happened far more rapidly in some areas than could be explained by the orbital precession alone, resulting in the Sahara Desert as we know it today. “Scientists usually call it ‘poor parameterization’ of the data,” Wright said by email. “Which is to say that we have no idea what we’re missing here—but something’s wrong.”

As Wright pored the archaeological and environmental data (mostly sediment cores and pollen records, all dated to the same time period), he noticed what seemed like a pattern. Wherever the archaeological record showed the presence of “pastoralists”—humans with their domesticated animals—there was a corresponding change in the types and variety of plants. It was as if, every time humans and their goats and cattle hopscotched across the grasslands, they had turned everything to scrub and desert in their wake.

Wright thinks this is exactly what happened. “By overgrazing the grasses, they were reducing the amount of atmospheric moisture—plants give off moisture, which produces clouds—and enhancing albedo,” Wright said. He suggests this may have triggered the end of the humid period more abruptly than can be explained by the orbital changes. These nomadic humans also may have used fire as a land management tool, which would have exacerbated the speed at which the desert took hold.

It’s important to note that the green Sahara always would’ve turned back into a desert even without humans doing anything—that’s just how Earth’s orbit works, says geologist Jessica Tierney, an associate professor of geoscience at the University of Arizona. Moreover, according to Tierney, we don’t necessarily need humans to explain the abruptness of the transition from green to desert.

Instead, the culprits might be regular old vegetation feedbacks and changes in the amount of dust. “At first you have this slow change in the Earth’s orbit,” Tierney explains. “As that’s happening, the West African monsoon is going to get a little bit weaker. Slowly you’ll degrade the landscape, switching from desert to vegetation. And then at some point you pass the tipping point where change accelerates.”

Tierney adds that it’s hard to know what triggered the cascade in the system, because everything is so closely intertwined. During the last humid period, the Sahara was filled with hunter-gatherers. As the orbit slowly changed and less rain fell, humans would have needed to domesticate animals, like cattle and goats , for sustenance. “It could be the climate was pushing people to herd cattle, or the overgrazing practices accelerated denudation [of foliage],” Tierney says.

Which came first? It’s hard to say with evidence we have now. “The question is: How do we test this hypothesis?” she says. “How do we isolate the climatically driven changes from the role of humans? It’s a bit of a chicken and an egg problem.” Wright, too, cautions that right now we have evidence only for correlation, not causation.

But Tierney is also intrigued by Wright’s research, and agrees with him that much more research needs to be done to answer these questions.

“We need to drill down into the dried-up lake beds that are scattered around the Sahara and look at the pollen and seed data and then match that to the archaeological datasets,” Wright said. “With enough correlations, we may be able to more definitively develop a theory of why the pace of climate change at the end of the AHP doesn’t match orbital timescales and is irregular across northern Africa.”

Tierney suggests researchers could use mathematical models that compare the impact hunter-gatherers would have on the environment versus that of pastoralists herding animals. For such models it would be necessary to have some idea of how many people lived in the Sahara at the time, but Tierney is sure there were more people in the region than there are today, excepting coastal urban areas.

While the shifts between a green Sahara and a desert do constitute a type of climate change, it’s important to understand that the mechanism differs from what we think of as anthropogenic (human-made) climate change today, which is largely driven by rising levels of CO2 and other greenhouse gases. Still, that doesn’t mean these studies can’t help us understand the impact humans are having on the environment now.

“It’s definitely important,” Tierney says. “Understanding the way those feedback (loops) work could improve our ability to predict changes for vulnerable arid and semi-arid regions.”

Wright sees an even broader message in this type of study. “Humans don’t exist in ecological vacuums,” he said. “We are a keystone species and, as such, we make massive impacts on the entire ecological complexion of the Earth. Some of these can be good for us, but some have really threatened the long-term sustainability of the Earth.”

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

Lorraine Boissoneault | | READ MORE

Lorraine Boissoneault is a contributing writer to SmithsonianMag.com covering history and archaeology. She has previously written for The Atlantic, Salon, Nautilus and others. She is also the author of The Last Voyageurs: Retracing La Salle's Journey Across America. Website: http://www.lboissoneault.com/

Sand dunes show the increasing desertification of the Tibetan Plateau, as land dries out and vegetation cover vanishes due to human activity.

- ENVIRONMENT

Desertification, explained

Humans are driving the transformation of drylands into desert on an unprecedented scale around the world, with serious consequences. But there are solutions.

As global temperatures rise and the human population expands, more of the planet is vulnerable to desertification, the permanent degradation of land that was once arable.

While interpretations of the term desertification vary, the concern centers on human-caused land degradation in areas with low or variable rainfall known as drylands: arid, semi-arid, and sub-humid lands . These drylands account for more than 40 percent of the world's terrestrial surface area.

While land degradation has occurred throughout history, the pace has accelerated, reaching 30 to 35 times the historical rate, according to the United Nations . This degradation tends to be driven by a number of factors, including urbanization , mining, farming, and ranching. In the course of these activities, trees and other vegetation are cleared away , animal hooves pound the dirt, and crops deplete nutrients in the soil. Climate change also plays a significant role, increasing the risk of drought .

All of this contributes to soil erosion and an inability for the land to retain water or regrow plants. About 2 billion people live on the drylands that are vulnerable to desertification, which could displace an estimated 50 million people by 2030.

Where is desertification happening, and why?

The risk of desertification is widespread and spans more than 100 countries , hitting some of the poorest and most vulnerable populations the hardest, since subsistence farming is common across many of the affected regions.

More than 75 percent of Earth's land area is already degraded, according to the European Commission's World Atlas of Desertification , and more than 90 percent could become degraded by 2050. The commission's Joint Research Centre found that a total area half of the size of the European Union (1.61 million square miles, or 4.18 million square kilometers) is degraded annually, with Africa and Asia being the most affected.

The drivers of land degradation vary with different locations, and causes often overlap with each other. In the regions of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan surrounding the Aral Sea , excessive use of water for agricultural irrigation has been a primary culprit in causing the sea to shrink , leaving behind a saline desert. And in Africa's Sahel region , bordered by the Sahara Desert to the north and savannas to the south, population growth has caused an increase in wood harvesting, illegal farming, and land-clearing for housing, among other changes.

The prospect of climate change and warmer average temperatures could amplify these effects. The Mediterranean region would experience a drastic transformation with warming of 2 degrees Celsius, according to one study , with all of southern Spain becoming desert. Another recent study found that the same level of warming would result in "aridification," or drying out, of up to 30 percent of Earth's land surface.

A herder family tends pastures beside a growing desert.

When land becomes desert, its ability to support surrounding populations of people and animals declines sharply. Food often doesn't grow, water can't be collected, and habitats shift. This often produces several human health problems that range from malnutrition, respiratory disease caused by dusty air, and other diseases stemming from a lack of clean water.

Desertification solutions

In 1994, the United Nations established the Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), through which 122 countries have committed to Land Degradation Neutrality targets, similar to the way countries in the climate Paris Agreement have agreed to targets for reducing carbon pollution. These efforts involve working with farmers to safeguard arable land, repairing degraded land, and managing water supplies more effectively.

The UNCCD has also promoted the Great Green Wall Initiative , an effort to restore 386,000 square miles (100 million hectares) across 20 countries in Africa by 2030. A similar effort is underway in northern China , with the government planting trees along the border of the Gobi desert to prevent it from expanding as farming, livestock grazing , and urbanization , along with climate change, removed buffering vegetation.

However, the results for these types of restoration efforts so far have been mixed. One type of mesquite tree planted in East Africa to buffer against desertification has proved to be invasive and problematic . The Great Green Wall initiative in Africa has evolved away from the idea of simply planting trees and toward the idea of " re-greening ," or supporting small farmers in managing land to maximize water harvesting (via stone barriers that decrease water runoff, for example) and nurture natural regrowth of trees and vegetation.

"The absolute number of farmers in these [at-risk rural] regions is so large that even simple and inexpensive interventions can have regional impacts," write the authors of the World Atlas of Desertification, noting that more than 80 percent of the world's farms are managed by individual households, primarily in Africa and Asia. "Smallholders are now seen as part of the solution of land degradation rather than a main problem, which was a prevailing view of the past."

FREE BONUS ISSUE

Related topics.

- AGRICULTURE

- DEFORESTATION

You May Also Like

They planted a forest at the edge of the desert. From there it got complicated.

Forests are reeling from climate change—but the future isn’t lost

Why forests are our best chance for survival in a warming world

How to become an ‘arbornaut’

Palm oil is unavoidable. Can it be sustainable?

- Environment

- Perpetual Planet

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Paid Content

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Savanna Hypothesis, The

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2016

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Gordon H. Orians 4

1003 Accesses

9 Altmetric

Habitat selection ; Landscape aesthetics

The Savanna Hypothesis states that we retain genetically based preferences for features of high-quality African savannas where our ancestors lived when their brains and bodies evolved into their modern forms.

Introduction

Selection of a place to live is a crucial step in the lives of most animals. Selection depends on the recognition of objects, sounds, and odors to which an animal, molded by natural selection, responds as if it understood their significance for its future survival and reproductive success. Evolutionary theory suggests that the ability of a landscape to evoke positive emotional states should be positively correlated with the expected survival and reproductive success of individuals of that species in it. In other words, good habitats should evoke strong positive responses; poor habitats should evoke weak or negative responses (Orians and Heerwagen 1992 ). Habitat selection has served as a conceptual basis for...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Appleton, J. (1975). The experience of landscape . New York: Wiley.

Google Scholar

Balling, J. D., & Falk, J. H. (1982). Development of visual preferences for natural environments. Environment and Behavior, 14 , 5–28.

Article Google Scholar

Bernáldez, F., Gallardo, D., & Abelló, R. P. (1987). Children’s landscape preferences: From rejection to attraction. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 7 , 169–176.

Campbell, B. (1985). Human evolution (3rd ed.). New York: Aldine.

Coss, R. G. (2003). The role of evolved perceptual biases in art and design. In E. Voland & K. Grammer (Eds.), Evolutionary aesthetics (pp. 69–130). Heidelberg: Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Coss, R. G., & Goldthwaite, R. O. (1995). The persistence of old designs for perception. In N. S. Thompson (Ed.), Perspectives in ethology, volume 11: Behavioral design (pp. 83–148). New York: Plenum Press.

Coss, R. G., & Moore, M. (2002). Precocious knowledge of trees as antipredator refuge in preschool children: An examination of aesthetics, attributive judgments, and relic sexual dinichism. Ecological Psychology, 14 , 181–222.

Heerwagen, J. H., & Orians, G. H. (1993). Humans, habitats, and aesthetics. In S. R. Kellert & E. O. Wilson (Eds.), The biophilia hypothesis (pp. 138–172). Washington, DC: Island Press.

Henshilwood, C. S., d’Errico, F., Marean, C. W., Milo, R. G., & Yates, R. (2001). An early bone tool industry from the Middle Stone Age at Blombos Cave, South Africa: Implications for the origins of modern human behaviour, symbolism and language. Journal of Human Evolution, 41 , 631–678.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Herzog, T. R. (1985). A cognitive analysis of preference for waterscapes. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 5 , 225–241.

Komar, V., & Melamid, A. (1997). In J. A. Wypijewski (Ed.), Painting by the numbers: Komar and Melamid’s scientific guide to art . New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Lohr, V. I., & Pearson-Mims, C. H. (2006). Responses to scenes with spreading, rounded, and conical tree forms. Environment and Behavior, 38 , 667–668.

Lyons, E. (1983). Demographic correlates of landscape preference. Environment and Behavior, 15 , 487–511.

Mellaart, J. (1968). Çatal Hüyük: A neolithic town in Anatolia . London: Thames and Hudson.

Nabhan, G. P. (2004). Why some like it hot. Food, genes, and cultural diversity . Washington, DC: Island Press.

Orians, G. H. (1980). Habitat selection. In J. S. Lockard (Ed.), The evolution of human social behavior (pp. 49–66). New York: Elsevier.

Orians, G. H. (2014). Snakes, sunrises and Shakespeare. How evolution shapes our loves and fears . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Book Google Scholar

Orians, G. H., & Heerwagen, J. H. (1992). Evolved responses to landscapes. In J. H. Barkow, L. Cosmides, & J. Tooby (Eds.), The adapted mind (pp. 555–579). New York: Oxford University Press.

Repton, H. (1907). The art of landscape gardening . Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Ross, S. (1998). What gardens mean . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Shanes, E. (1979). Turner’s picturesque views of England and Wales, 1825–1838 . London: Chatto & Windus.

Shuttleworth, S. (1980). The use of photographs as an environmental presentation medium in landscape studies. Journal of Environmental Management, 11 , 61–76.

Sommer, R. (1997). Further cross-national studies of tree-form preference. Ecological Psychology, 9 , 153–160.

Sommer, R., & Summit, J. (1996). Cross-national rankings of tree shape. Ecological Psychology, 8 , 327–341.

Tuan, Y.-F. (1974). Topophilia. A study of environmental perception, attitudes, and values . Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Ulrich, R. S. (1981). Natural versus urban spaces: Some psychophysiological effects. Environment and Behavior, 13 , 523–556.

Wilson, M. E., Robertson, L. D., Daley, M., & Walton, S. A. (1995). Effects of visual cues on assessment of water quality. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15 , 53–63.

Witzel, M. (2015). Water in mythology. Daedalus, 144 , 18–26.

Wrangham, R. (2009). Catching fire. How cooking made us human . New York: Basic Books.

Zube, E. H., Simcox, D. E., & Law, C. S. (1987). Perceptual landscape simulations: History and prospect. Landscape Journal, 6 , 62–80.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 98195, USA

Gordon H. Orians

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Gordon H. Orians .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Oakland Univ Dept of Psycholgy, Rochester, Michigan, USA

Viviana Weekes-Shackelford

Department of Psychology, Oakland University, Rochester, Michigan, USA

Todd K. Shackelford

Rochester, Michigan, USA

Viviana A. Weekes-Shackelford

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Orians, G.H. (2016). Savanna Hypothesis, The. In: Weekes-Shackelford, V., Shackelford, T., Weekes-Shackelford, V. (eds) Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16999-6_2930-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16999-6_2930-1

Received : 26 April 2016

Accepted : 29 April 2016

Published : 23 September 2016

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-16999-6

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Behavioral Science and Psychology Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Claims about desert are familiar and frequent in ordinary non-philosophical conversation. We say that a hard-working student who produces work of high quality deserves a high grade; that a vicious criminal deserves a harsh penalty; that someone who has suffered a series of misfortunes deserves some good luck for a change.

Philosophers have made use of the concept of desert in several contexts. In discussions of the nature of justice, several philosophers have advocated versions of the idea that justice obtains when goods and evils are distributed according to desert. In discussions of the concept of intrinsic value, some philosophers have suggested that happiness may be the greatest good but it has outstanding value only when enjoyed by someone who deserves it. In theories about moral obligation, some consequentialists have defended the idea that right acts lead to outcomes in which higher welfare is preferentially distributed to people who deserve it. In social and political philosophy (or philosophy of law) a number of philosophers have appealed to the concept of desert when discussing the justification of penalties for violations of law.

So appeals to desert appear frequently in many contexts, in philosophy as well as in ordinary non-philosophical talk. Yet many questions remain about desert: how can it be distinguished from mere entitlement? What is its conceptual structure? What kinds of things can be deserving? What kinds of things can be deserved? What kinds of properties can serve as bases on which a deserver deserves a desert? How can claims about desert be justified?

1. Desert and Entitlement

2. deservers, desert, and desert bases, 3. the justification of desert claims, 4. desert and intrinsic value, 5. desertist theories of justice, works cited, other readings, other internet resources, related entries.

It is important here at the outset that we draw attention to a distinction between desert and another concept with which it might be confused. We will speak of this latter concept as the concept of entitlement , though different philosophers use different terminology to mark this distinction.

A typical desert claim is a claim to the effect that someone – the “deserver” – deserves something – the “desert” – in virtue of his or her possession of some feature – the “desert base”. [ 1 ] For example, consider the claim that a certain student deserves a high grade from her teacher in virtue of the fact that she did excellent work in the course. A typical entitlement claim is a claim to the effect that someone is entitled to something from someone on some basis. For example, consider the claim that a customer is entitled to a refund from a merchant in virtue of the fact that the merchandise he purchased from that merchant had been sold with a guarantee and turned out to be defective.

There are obvious structural similarities between desert claims and claims about entitlement. In typical examples of each sort, someone is said to deserve (or be entitled to) something from someone on some basis. However, there is an important difference between the concepts of desert and entitlement. As the terminology is used here, desert is a more purely normative concept, while entitlement is a sociological or empirical concept. If some social or legal institution is in place in your social group, and that institution has a rule that specifies some treatment for those who have some feature, and you have the feature, then you are entitled to that treatment. Thus, for example, suppose that when the customer purchased a certain item, he received a legally binding written guarantee from the seller. The guarantee specified that if the item should turn out to be defective, the seller would either replace the item or refund the money that the buyer had spent for the defective item. In such a case, if the buyer satisfies the conditions stated in the guarantee, and the purchased item is indeed defective, the buyer is entitled to the refund or replacement.

Typical desert claims have a similar structure, but do not always depend in this way on the existence of laws or contracts or other similar social institutions. A person may deserve some sort of treatment even though there are no rules in place in his society that codify the conditions under which someone deserves that sort of treatment. In such a case, a person may deserve something even though he is not entitled to it. Similarly, a person may be entitled to something by some rules that are in place in his society even though he does not deserve it. Some examples may help to make this distinction clearer.

Consider an example involving a wealthy grandfather and two grandchildren. One grandchild is vicious and rich; the other is virtuous and poor. The vicious grandchild never treated his grandfather with respect. The virtuous grandchild was always respectful and caring. Suppose the grandfather leaves his entire fortune to the vicious grandchild. As the terminology is used here, we may want to describe the situation by saying that the vicious grandchild is entitled to the fortune (the rules of the legal system are unambiguous on this point), but at the same time we may want to say that he does not deserve it (he already has too much money; he is a rotten person who never treated his grandfather respectfully). The virtuous grandchild may deserve at least some of the inheritance, but he is not entitled to any of it.

Another example illustrates the same point. Suppose that an athlete has her heart set on doing well in a competition. Suppose she has a lot of natural talent and trains diligently for a long time until she has developed championship-level abilities in her sport. Suppose that the training involves quite a bit of sacrifice on her part. Suppose that at the last minute the competition is cancelled, and the athlete has no opportunity to compete. Then we might say that this was a great misfortune for her; she deserved to have a chance to participate. Unfortunately, there is no rule in the rulebook of the athlete’s sport that says that those who have trained diligently are to get a chance to participate. Let us assume that there is no institution in place in the athlete’s society that specifies that those who train hard shall be given a chance to compete. In this case, it would be wrong to say (using the terminology in the way that has been specified) that the athlete is entitled to a chance to participate, yet we may still feel that she deserved the chance. This seems to be an example of a case in which someone has completely “non-institutional” desert of something.

Some philosophers use the expression ‘pre-institutional desert’ where we use ‘desert’, and ‘institutional desert’ where we use ‘entitlement’. To avoid confusion, we will use ‘desert’ to refer to the relation that does not essentially involve the existence of social or legal institutions, and ‘entitlement’ to refer to the relation that does essentially involve the existence of such institutions. Our focus in this article is on desert; we mention entitlement only as it bears on desert.

In his seminal work on desert and justice (Feinberg 1970) Joel Feinberg presented a catalog of types of seemingly uncontroversial desert claims: a student might deserve a high grade in virtue of having written a good paper; an athlete might deserve a prize in virtue of having excelled in a competition; a successful researcher might deserve an expression of gratitude in virtue of having perfected a disease-preventing serum; a criminal might deserve the contempt of his community in virtue of having committed crimes; the victim of an industrial accident may deserve compensation from his negligent employer; a hard-working public official may deserve to be promoted to a higher office in virtue of her diligence. Leibniz, Kant, and others focused on examples in which a person is said to deserve happiness in virtue of having been morally excellent.

In all these familiar cases, the deserver is a person. But as Feinberg himself mentioned, there does not seem to be any conceptual barrier to saying that non-persons may also be deservers. Thus, for example, it seems acceptable to say that a beautiful ancient city deserves to be preserved; that a unique and formerly vibrant ecosystem deserves to be restored; that the scene of a horrible massacre deserves to be torn down. In moral and political discussions, cases under scrutiny tend to be ones in which deservers are either individual people or groups of people. This should not blind us to the fact that non-persons can also be deservers.

Desert claims also typically involve a desert . This is the thing that the deserver is said to deserve. As Feinberg indicated, familiar deserts include such things as grades, wages, prizes, respect, honors and awards, rights, love, benefits and other such things. Leibniz and Kant would surely insist that we include happiness among the possible deserts; and others would insist that we should mention welfare.

Those deserts may seem at first to be “positive.” However, there are “negative” counterparts. Indeed, some of the items on that list are already negative. Thus, some grades are bad grades, as for example, the F a student might deserve for a very weak paper. Other deserts are uniformly negative: burdens, fines, booby prizes, contempt, dishonors, onerous obligations, penalties, condemnation, hate, etc.

Some contributors to the literature on desert suggest that every desert is either a plus or a minus. Some speak, in this context of “benefits and burdens,” or advantages and disadvantages. However, there are cases in which someone deserves something that is neither good nor bad, neither a benefit nor a burden. Suppose someone who has done outstanding academic work deserves to get an A, while someone who has done completely unsatisfactory work deserves to get an F. It is reasonable to suppose that the A is a good grade – something the recipient will be pleased to get – and the F is a bad grade – something that the recipient will be disappointed to get. But suppose a student did mediocre work and deserves a mediocre grade – a C. This is neither good nor bad, neither a benefit nor a burden. Nevertheless, someone might deserve it. This would be a case in which someone deserves something that is neither “positive” nor “negative.”

The same could be true of welfare. Someone might deserve happiness and (we may assume) that would be a good thing to get; someone else might deserve unhappiness and (we may assume) that would be a bad thing to get. But another person might deserve to be at an intermediate welfare level, neither happy nor unhappy. While it might be good in some way for the person to be at that neutral welfare level, the thing he deserves would be neither good nor bad. So while it is convenient to say that deserts are benefits or burdens – things that will be good or bad for the deserver to receive – in fact some deserts are neither benefits nor burdens.

Feinberg suggested that we can distinguish between “basic” and “derived” deserts. He went on to say that basic deserts are always responsive attitudes such as approval and disapproval. On this view, derived deserts are forms of treatment that would be fitting expressions of the more fundamental basic deserts. Thus, giving a student an A might be the fitting expression for approval of her work; giving a student an F might be the most fitting expression of serious disapproval of her work. Some recent contributors to the literature on desert seem to ignore this distinction between basic and derived desert, but others continue to employ the distinction and to treat it as important. Scanlon, for example, makes it a central feature of his conception of desert (see Scanlon 2013, 2018).

Perhaps the most important and controversial bit of information we typically seek in connection with a claim about desert concerns the desert base . This is generally taken to be the feature in virtue of which the deserver deserves the desert. On this view, a desert base is always a property. If we adopt this view, we will say (for example) that the student deserves a high grade in virtue of her possession of the property of having produced course work of high quality . On another view, a desert base is always a fact. If we adopt this view we will prefer to say that the student deserves her high grade in virtue of the fact that her work was of such high quality .

We are inclined to think that it makes no difference whether we take desert bases to be properties or to be facts. The views seem to be intertranslatable. In this article, simply as a matter of convenience, we generally speak of desert bases as properties.

In some cases there is little debate about whether a certain property serves as a desert base for a certain sort of treatment. This may be illustrated by the example of the student who produced outstanding work in a course and deserves a high grade. Few would debate the claim that the student deserves the grade in virtue of the high quality of her work. The desert base in that case would be having produced academic work of high quality . Similarly consider the case of the cold-blooded criminal who has inflicted great harm on many innocent victims. It is reasonable to suppose that he deserves a harsh penalty in virtue of his evil behavior. In this case, the desert base is something like having inflicted great harm on many innocent victims .

In other cases, however, there would be more controversy about desert bases. A good example involves the desert of wages. Suppose an employee works hard, is productive, is loyal to his employer, and in virtue of some health problems in his family, needs more money. We may agree in such a case that the employee deserves a raise – but we may disagree about the basis on which he deserves that raise.

There is general agreement that properties of certain types cannot serve as desert bases. Consider a case in which punishing an innocent person would have good consequences. The person has this property: being such that punishing him would have good consequences . But it would be seriously counterintuitive to say that the person deserves punishment in virtue of his possession of this property.

Certain general principles about desert bases have been introduced in an effort to explain why certain properties seem ineligible to serve as desert bases. Perhaps the least controversial principle is the so-called “Aboutness Principle,” mentioned by Feinberg. In its propositional form, this principle says that a person can deserve something in virtue of a certain fact only if that fact is a fact “about the person.” In its property form, the principle would say that a person can deserve something in virtue of a certain property only if the person actually has the property. The Aboutness Principle does not offer any assistance with respect to the punishment case just mentioned. After all, the innocent person in that example actually does have the property of being such that punishing him would have good consequences . The fact that punishing him would have good consequences is a fact about him.

Some have said that if someone deserves something, D, in virtue of having some desert base, DB, then the deserving one must be responsible for having DB (see, for example, Rawls 1971; Rachels 1978; Sadurski 1985). This “Responsibility Principle” seems to be satisfied by many of the examples already discussed. The good student, we may suppose, is responsible for having produced good academic work. The cold-blooded criminal, similarly, may seem responsible for his vicious behavior. The hard working employee bears some responsibility for having worked so hard. We may generalize from these cases and conclude that all cases of desert are like this: if someone deserves something, D, on some basis, DB, then he or she is responsible for having DB. Appeal to the Responsibility Principle would explain why the innocent person does not deserve punishment. He is not responsible for having the property of being such that punishing him would have good consequences .

A variety of cases have been offered as counterexamples to the Responsibility Principle. Feldman (1995a) described a case in which patrons at a restaurant became ill as a result of having been served spoiled food. He claimed that the patrons in such a case would deserve compensation. The desert base here seems to be having been harmed by the negligent food preparation by the restaurant – yet the patrons were not responsible for having that desert base. They were innocent victims. A similar thing happens in the case of someone who has been egregiously insulted. She may deserve an apology in virtue of having been insulted, but she is not responsible for the insult. Another case mentioned by McLeod involves a child who, through no fault of his own, comes down with a painful illness. He deserves the care and sympathy of his parents, yet he is not responsible for having become ill.

Others have suggested what may be called “the Temporality Principle”: the idea here is roughly this: if someone deserves something, D, in virtue of having a certain desert base, DB, then he or she must already have DB at the time he or she begins to deserve D (see, for example, Rachels 1978; Kleinig 1971; Sadurski 1985). You cannot deserve something on the basis of a property you will begin to have only later. The Temporality Principle has been invoked in an effort to explain why it is wrong to engage in “pre-punishment.” It is said that even if a certain person is going to commit a crime, he does not begin to deserve punishment for that crime until he actually commits it. This line of thought has been debated. One problem is that even before he commits the crime, the future criminal already has this property: being such that he will later commit a crime . It might be said that he deserves punishment in virtue of already having this property even before he commits the crime. While the Temporality Principle is widely endorsed, counterexamples have been presented (see, for example, Feldman 1995b). Those counterexamples have not been universally accepted (see, for example, Smilansky 1996a, 1996b).

In many cases, when we make a desert claim we mention a distributor . This is the person or institution from whom the deserver deserves to receive the desert. In some cases, the identity of the distributor will be clear. In other cases, it is not so clear. Consider, for example, the motto that the McDonald’s restaurants formerly used: ‘You deserve a break today.’ No distributor is explicitly mentioned in the motto. It just says that you deserve a break. Perhaps when McDonald’s made this statement, they did not have any particular distributor in mind. Maybe they just thought that you deserve it from someone . The same would be true of the Gates Foundation’s former motto according to which ‘Every person deserves the chance to live a healthy and productive life.’ The motto does not mention anyone who has the job of ensuring that everyone gets a chance to live a healthy and productive life. Given that no one has the capacity to ensure that everyone lives a healthy and productive life, we may conclude that in this case no distributor is mentioned precisely because no one is qualified to be a distributor.

In other cases, there is a distributor and its identity is clear. Consider, for example, the claim that a certain elderly professor deserves some respect from his unruly students. Here the distributor is explicitly mentioned: it is the unruly students. Those who endorse the notion that virtuous people deserve happiness in heaven will presumably say that the distributor in that case is God. In social and political contexts we often find philosophers assuming that citizens deserve certain rights from the government of their country.

It may seem that we could relocate this reference to the distributor. We could build reference to the distributor into the description of the desert. Thus, instead of saying that the desert in the example involving the elderly professor is respect , we could say that the desert is respect from his students .

In some cases a desert statement may also indicate something about the strength of the deserver’s desert of the thing deserved. The strength of someone’s desert of something might be indicated loosely, as when we say that someone’s desert of something is “very strong,” or “only slight.” In some cases we can use some numbers to represent strengths of desert, though the choice of a numbering system will be to some extent arbitrary. But there are some important facts here: sometimes you deserve both A and B, but you deserve A more than you deserve B; sometimes two different deservers deserve the same thing and it is not possible for both of them to get it; maybe one of them deserves it more than the other. Sometimes you deserve something, but only to a very slight degree and this desert could easily be overridden by some other consideration.

In many cases a desert statement (if fully spelled out) would also indicate some times . One of these is the time of the deserving; the other is the time when the receipt of the desert is supposed to take place. Thus, for example, suppose a lot of money has been withheld from a certain person’s paycheck each week for a whole year. Suppose in fact the government has withheld more than the person owes in taxes. Then he deserves a refund. Suppose refunds are all given out on April 1. We might want to say this: at every moment in March, the taxpayer deserves to get a refund on April 1. In this example, the time of the deserving is every moment in March . The time at which the deserver deserves to receive the desert is April 1.

A number of related questions have been discussed under the general title of ‘the justification of desert claims.’ Some apparently take the question about justification to be a question about epistemic justification (see, for example, McLeod 1995, 89). If we understand the question in this way, we may want to know how – if at all – a person can be epistemically justified in believing that (for example) hard work is a desert base for reward. Others take the question about justification in a different way. They take it to be a question about explanation . Consider again the question about the justification of the claim that hard work makes us deserve reward. On this second interpretation, the question is: what explains the fact that hard work is a desert base for reward? Others speak in this context of “normative force” (see, for example, Sher 1987, xi). They seem to be concerned with a question about what explains the fact that when someone deserves something, it is obligatory for others to provide it, or good that it be provided. Still others may phrase the question by appeal to concepts of grounding or foundation . They may ask what grounds the fact that those who work hard deserve rewards. Still others write a bit more vaguely about the analysis of desert claims (see, for example, Feinberg 1970).

There is a further distinction to be noted. Some who write about the justification of desert claims seem to think that it is specific desert claims about particular individuals that call for justification. Thus, they might ask for a justification of the claim that Jones deserves a $100 bonus for having worked extra hard over the holiday weekend. Others apparently think that what calls for justification is a more general claim about desert bases and deserts. They might ask for a justification of the claim that hard work is a desert base for financial reward .

We will formulate the discussion in the admittedly vague idiom of justification of claims about desert bases and deserts . But as we understand the question, it can be explicated in this way: suppose someone claims that in general the possession of some desert base, DB, makes people deserve a certain desert, D. If challenged, how could the maker of such a claim support his claim? How could he argue for his assertion? What facts about DB and D could he cite in order to show that he was right – the possession of DB does make someone deserve D?

Some who write on this topic are “monists” about justification; they apparently assume that there is a single feature that will serve in all cases to justify desert claims. Others are “pluralists.” They defend the idea that desert claims fall into different categories, and that each category has its own distinctive sort of justification (see, for example, Feinberg 1970, Sher 1987, and Lamont 1994). We first consider some monist views.

Some popular views about the justification of desert claims are based on the idea that such claims can be justified by appeal to considerations about the values of consequences. Sidgwick seems to be thinking of something like this in The Methods of Ethics where he mentions ‘the utilitarian interpretation of Desert.’ He describes this by saying: ‘when a man is said to deserve reward for any services to society, the meaning is that it is expedient to reward him, in order that he and others may be induced to render similar services by the expectation of similar rewards’ (1907, 284, note 1). (It is not clear that Sidgwick means to defend this view about desert; he seems to be offering it as an account of what a determinist would have to say.)

Sidgwick’s statement has direct implications only for cases in which what is deserved is some sort of reward and the desert base of this desert is some sort of ‘service to society.’ As a result, it is not clear that this idea about justification, taken simply by itself, has any direct relevance to cases in which someone deserves punishment, or compensation, or a prize for outstanding performance, or a grade for academic work.

According to a natural extension of the view that Sidgwick mentioned, a claim to the effect that someone deserves something, D, in virtue of his possession of some feature, DB, is justified by pointing out that giving the person D in virtue of his possession of DB would have high utility.

While there surely are some cases in which giving someone what he deserves would have high utility, this link between desert and utility is just as frequently absent. To see this, consider a case in which a very popular person has engaged in some bad behavior for which he deserves punishment – but suppose in addition that no one believes he is guilty. If he were punished for having done the nasty deed, there would be an outpouring of anger from all of the popular person’s fans and friends who think he has been framed. If our interest were in producing an outcome with high utility, we would have to refrain from punishing him. But in spite of that, since in fact he did do the nasty deed, he does deserve the punishment.

In other cases, giving a person some benefit might have good results even though the person does not deserve to receive those benefits. To see this, imagine that a crazed maniac threatens to murder a dozen hostages unless he is given a half-hour of prime time TV to air his grievances. Giving him this airtime might have high utility – it might be the best thing for those in charge to do in the circumstances – but at the same time we might feel that the maniac does not deserve it.

Another serious problem with the consequentialist approach is brought out by consideration of the famous telishment case, also known as ‘The Small Southern Town.’ The example was presented by Carritt in his Ethical and Political Thinking , but gained great notoriety as a result of being quoted at length in Rawls’s ‘Two Concepts of Rules’ (Rawls 1955). Here is the passage from Carritt:

…if some kind of very cruel crime becomes common, and none of the criminals can be caught, it might be highly expedient, as an example, to hang an innocent man, if a charge against him could be so framed that he were universally thought guilty… (Carritt 1947, 65)

In this example, punishing an innocent person has high utility because it would have great deterrent effect. But the victim of the punishment does not deserve punishment – after all, he is innocent. This highlights an important fact about desert and utility: sometimes it can be expedient to give someone a reward or a punishment that he or she does not deserve.

It appears then that the consequentialist approach confronts overwhelming objections. Sometimes deserved treatment is expedient; sometimes it is not. Sometimes undeserved treatment is expedient; sometimes it is not. As a result, appeals to the utility of giving someone some benefit or burden cannot justify the claim that the person deserves that sort of treatment.

A second approach to the justification of desert claims is based on some ideas concerning institutions. There are several different ways in which this “institutional justification” can be developed. (Our discussion in this section has benefited enormously from McLeod 1999b.)

First, some background: an institution may be identified by a system of rules that define positions, moves, penalties, rewards, etc. In some cases the rules of an institution are carefully written down and perhaps made a matter of legislation. The system of taxation in some country might be a good example. In other cases the rules of an institution are not explicitly formalized. An example might be the system of etiquette governing the writing, sending, replying to, etc. of wedding invitations. It is not easy to say what makes an institution “exist” in a society. That is a puzzle best left to the sociologists.

We may also need to assume that when people set up institutions, they do so with some intention. They are trying to achieve something; or more likely, they are trying to achieve several different things. Maybe different people have different aims. We can say – somewhat vaguely – that the point of an institution is the main goal or aim that people have in establishing or maintaining that institution.

A person may be governed by some institution even if he does not like it, or does not endorse it. Thus, for example, suppose a criminal justice system exists in a certain state. Suppose some miscreant lives in that state and has been charged with some crime. Suppose he is found guilty in a duly established court of law and is sentenced to ten years in prison. He is governed by the rules of the judicial system whether he likes it or not. To be governed by an institution one must live (or perhaps be a visitor) in the state or society where the institution exists, and one must somehow “fall under” the rules. Those rules must “apply to” the individual. Again, these are tricky sociological notions, not easily spelled out.

Some philosophers have said things that suggest that it is possible to justify a desert claim by identifying a currently existing, actual institution according to which the deserver is entitled to the desert. We can state this idea a bit more clearly:

AID: The claim that a person, S, deserves something, D, on the basis of the fact that he has a feature, DB, is justifiable if and only if there is some social institution, I; I exists in S’s society; S is governed by I; according to the rules of I, those who have DB are to receive D; S has DB.

This “actual institutional” account of desert is almost universally rejected. [ 2 ] There are several independent sources of difficulty. Most of these emerge from the requirement that a desert claim is justifiable always and only when there is an appropriate actual social institution. This produces a number of devastating objections. Suppose a thoroughly decent person has suffered a number of serious misfortunes. He deserves a change of luck; he deserves some good luck for a change. Suppose he lives in a country where there is no social institution that supplies compensatory benefits to those who have had bad luck. If AID were true, it would be impossible to justify the claim that he deserves it.

An equally serious objection arises from the fact that some of the institutions that actually exist are morally indefensible. Let us imagine a thoroughly horrible social institution – slavery. Suppose some unfortunate individual is governed by that institution. Suppose the institution contains rules that say that slaves who are strong and healthy shall be required to work without pay in the cotton fields. Suppose this individual is strong and healthy. Consider the claim that he deserves to be required to work in the fields without pay in virtue of the fact that he is strong and healthy. AID implies that this desert claim is justified. That is as preposterous as it is offensive.

The general point: we must not lose sight of the fundamental difference between entitlement and desert . AID seems to confuse these. It seems to say that you deserve something if and only if you are entitled to it by the rules of an actual institution. Since there are bad institutions, and cases in which desert arises in the absence of institutions, this is clearly a mistake.

We can deal with all of these objections by altering the institutional account of justification. Instead of making the justification of a desert claim depend upon the existence of an actual social institution, we can make it depend upon the rules that would be contained in some ideal social institution. The main change is that we no longer require that the social institution exists. We require instead that it be an ideal institution – an institution that would be in some way excellent or preferable. Then we can attempt to justify desert claims by saying that the deservers would be entitled to those deserts by the rules of an ideal social institution.

We can state the thesis this way:

IID: The claim that a person, S, deserves something, D, on the basis of the fact that he has a feature, DB, is justifiable if and only if there is some possible social institution, I; I would be ideal for S’s society; S would be governed by I; according to the rules of I, those who have DB are to receive D; S has DB.

Before we can evaluate this proposal, we have to explain in greater detail what makes a possible institution “ideal” for a society. We might try to define ideality by saying that an ideal institution is one that would distribute benefits and burdens to people precisely in accord with their deserts. With this account of ideality in place, IID generates quite a few correct results. Unfortunately, it would be unhelpful in the present context. After all, the aim here is to explain how desert claims can be justified. This account would explain desert by appeal to ideal institutions, and then explain ideal institutions by appeal to desert.

Following the rule utilitarians, we could attempt to define ideality by saying that a possible institution is ideal for a society if and only if having it as the society’s institutional way of achieving its point would produce more utility than would the having of any alternative institution. This yields a form of the institutional approach that seems importantly similar to the consequentialist approach already discussed.

Unfortunately, with this conception of ideality in place, the proposal seems to inherit some of the defects of the simpler consequentialist approach. It implies, for example, that if it is possible for there to be a seriously unfair but nevertheless utility maximizing institution, then people would deserve the burdens allocated to them by the rules of that institution, even if it were not in place.

A further difficulty arises in connection with actual but not optimific institutions. Suppose, for example, the utility maximizing ice-skating institution would have rules specifying that in order to win the gold medal, a competitor must perform a 7 minute free program; a 6 minute program of required figures; and that all contestants must wear regulation team uniforms consisting of full length trousers and matching long-sleeved team shirts. Suppose in fact that this institution is not in place in Nancy’s society. Suppose instead that the de facto institution contains some slightly different but still fairly reasonable rules for ice-skating competitions. Suppose Nancy abides by all the relevant extant rules and is declared the winner in a competition. She is entitled to the gold medal by the actual rules. It may seem, in such a case, that her claim to deserve the medal would be justified. But since she would not be entitled to it by the rules of the ideal institution, IID implies that it is impossible to justify her claim that she deserves the medal by virtue of her performance here tonight.

It appears, then, that difficulties confront the attempt to justify desert claims by appeal to claims about the entitlements created by institutions, actual or ideal.

Some philosophers have drawn attention to alleged connections between desert claims and facts about “appraising attitudes” or “responsive attitudes” (see, for example, Feinberg 1970). Commentators have understood these philosophers to have been defending the idea that desert claims can be justified by appeal to facts about appraising attitudes. Some have said, for example, that David Miller defended a view of this sort in his Social Justice (1976). While there may be debate about whether Miller actually intended to be defending such a view, it is worthwhile to consider it. (In the discussion that follows we are indebted to McLeod 1995 and McLeod 2013.)

We need first to understand what is meant by ‘appraising attitude.’

Admiration, approval, and gratitude are typically cited as examples of “positive” appraising attitudes. In each case, if a person has such an attitude toward someone, he has that attitude in virtue of some feature that he takes the person to have. Suppose, for example, that you admire someone; then you must admire her for something she is or something she did . Maybe she worked hard; or wrote a good paper; or can run very fast; or is able to play the violin beautifully. Similarly for the other positive appraising attitudes.

Disapproval, resentment, contempt, “thinking ill of,” and condemnation may be cited as examples of “negative” appraising attitudes. They are similar to the positive attitudes in this respect, if you disapprove of someone, then you must disapprove of him for something he is or something he did . Maybe he plagiarized a paper; maybe he is totally out of shape; maybe he is utterly talentless.