Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved April 4, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination and analysis of a particular phenomenon or case, such as an individual, organization, community, event, or situation.

It is a qualitative research approach that aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the case being studied. Case studies typically involve multiple sources of data, including interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, which are analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory. The findings of a case study are often used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Types of Case Study

Types and Methods of Case Study are as follows:

Single-Case Study

A single-case study is an in-depth analysis of a single case. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand a specific phenomenon in detail.

For Example , A researcher might conduct a single-case study on a particular individual to understand their experiences with a particular health condition or a specific organization to explore their management practices. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a single-case study are often used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Multiple-Case Study

A multiple-case study involves the analysis of several cases that are similar in nature. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to identify similarities and differences between the cases.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a multiple-case study on several companies to explore the factors that contribute to their success or failure. The researcher collects data from each case, compares and contrasts the findings, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as comparative analysis or pattern-matching. The findings of a multiple-case study can be used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Exploratory Case Study

An exploratory case study is used to explore a new or understudied phenomenon. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to generate hypotheses or theories about the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an exploratory case study on a new technology to understand its potential impact on society. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as grounded theory or content analysis. The findings of an exploratory case study can be used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Descriptive Case Study

A descriptive case study is used to describe a particular phenomenon in detail. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to provide a comprehensive account of the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a descriptive case study on a particular community to understand its social and economic characteristics. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a descriptive case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Instrumental Case Study

An instrumental case study is used to understand a particular phenomenon that is instrumental in achieving a particular goal. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand the role of the phenomenon in achieving the goal.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an instrumental case study on a particular policy to understand its impact on achieving a particular goal, such as reducing poverty. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of an instrumental case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Case Study Data Collection Methods

Here are some common data collection methods for case studies:

Interviews involve asking questions to individuals who have knowledge or experience relevant to the case study. Interviews can be structured (where the same questions are asked to all participants) or unstructured (where the interviewer follows up on the responses with further questions). Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

Observations

Observations involve watching and recording the behavior and activities of individuals or groups relevant to the case study. Observations can be participant (where the researcher actively participates in the activities) or non-participant (where the researcher observes from a distance). Observations can be recorded using notes, audio or video recordings, or photographs.

Documents can be used as a source of information for case studies. Documents can include reports, memos, emails, letters, and other written materials related to the case study. Documents can be collected from the case study participants or from public sources.

Surveys involve asking a set of questions to a sample of individuals relevant to the case study. Surveys can be administered in person, over the phone, through mail or email, or online. Surveys can be used to gather information on attitudes, opinions, or behaviors related to the case study.

Artifacts are physical objects relevant to the case study. Artifacts can include tools, equipment, products, or other objects that provide insights into the case study phenomenon.

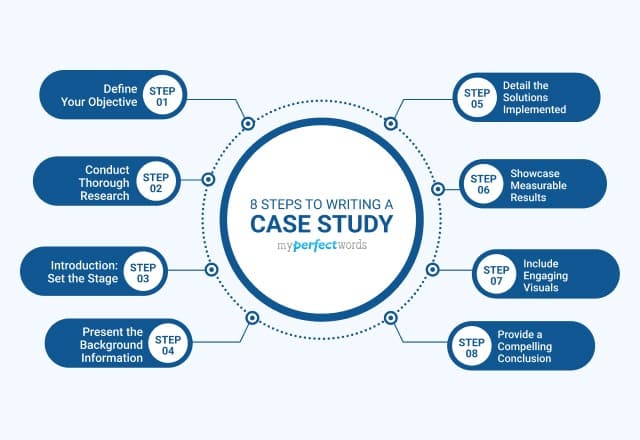

How to conduct Case Study Research

Conducting a case study research involves several steps that need to be followed to ensure the quality and rigor of the study. Here are the steps to conduct case study research:

- Define the research questions: The first step in conducting a case study research is to define the research questions. The research questions should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the case study phenomenon under investigation.

- Select the case: The next step is to select the case or cases to be studied. The case should be relevant to the research questions and should provide rich and diverse data that can be used to answer the research questions.

- Collect data: Data can be collected using various methods, such as interviews, observations, documents, surveys, and artifacts. The data collection method should be selected based on the research questions and the nature of the case study phenomenon.

- Analyze the data: The data collected from the case study should be analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, or grounded theory. The analysis should be guided by the research questions and should aim to provide insights and conclusions relevant to the research questions.

- Draw conclusions: The conclusions drawn from the case study should be based on the data analysis and should be relevant to the research questions. The conclusions should be supported by evidence and should be clearly stated.

- Validate the findings: The findings of the case study should be validated by reviewing the data and the analysis with participants or other experts in the field. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Write the report: The final step is to write the report of the case study research. The report should provide a clear description of the case study phenomenon, the research questions, the data collection methods, the data analysis, the findings, and the conclusions. The report should be written in a clear and concise manner and should follow the guidelines for academic writing.

Examples of Case Study

Here are some examples of case study research:

- The Hawthorne Studies : Conducted between 1924 and 1932, the Hawthorne Studies were a series of case studies conducted by Elton Mayo and his colleagues to examine the impact of work environment on employee productivity. The studies were conducted at the Hawthorne Works plant of the Western Electric Company in Chicago and included interviews, observations, and experiments.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment: Conducted in 1971, the Stanford Prison Experiment was a case study conducted by Philip Zimbardo to examine the psychological effects of power and authority. The study involved simulating a prison environment and assigning participants to the role of guards or prisoners. The study was controversial due to the ethical issues it raised.

- The Challenger Disaster: The Challenger Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986. The study included interviews, observations, and analysis of data to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

- The Enron Scandal: The Enron Scandal was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Enron Corporation’s bankruptcy in 2001. The study included interviews, analysis of financial data, and review of documents to identify the accounting practices, corporate culture, and ethical issues that led to the company’s downfall.

- The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster : The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the nuclear accident that occurred at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan in 2011. The study included interviews, analysis of data, and review of documents to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

Application of Case Study

Case studies have a wide range of applications across various fields and industries. Here are some examples:

Business and Management

Case studies are widely used in business and management to examine real-life situations and develop problem-solving skills. Case studies can help students and professionals to develop a deep understanding of business concepts, theories, and best practices.

Case studies are used in healthcare to examine patient care, treatment options, and outcomes. Case studies can help healthcare professionals to develop critical thinking skills, diagnose complex medical conditions, and develop effective treatment plans.

Case studies are used in education to examine teaching and learning practices. Case studies can help educators to develop effective teaching strategies, evaluate student progress, and identify areas for improvement.

Social Sciences

Case studies are widely used in social sciences to examine human behavior, social phenomena, and cultural practices. Case studies can help researchers to develop theories, test hypotheses, and gain insights into complex social issues.

Law and Ethics

Case studies are used in law and ethics to examine legal and ethical dilemmas. Case studies can help lawyers, policymakers, and ethical professionals to develop critical thinking skills, analyze complex cases, and make informed decisions.

Purpose of Case Study

The purpose of a case study is to provide a detailed analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. A case study is a qualitative research method that involves the in-depth exploration and analysis of a particular case, which can be an individual, group, organization, event, or community.

The primary purpose of a case study is to generate a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case, including its history, context, and dynamics. Case studies can help researchers to identify and examine the underlying factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and detailed understanding of the case, which can inform future research, practice, or policy.

Case studies can also serve other purposes, including:

- Illustrating a theory or concept: Case studies can be used to illustrate and explain theoretical concepts and frameworks, providing concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Developing hypotheses: Case studies can help to generate hypotheses about the causal relationships between different factors and outcomes, which can be tested through further research.

- Providing insight into complex issues: Case studies can provide insights into complex and multifaceted issues, which may be difficult to understand through other research methods.

- Informing practice or policy: Case studies can be used to inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

Advantages of Case Study Research

There are several advantages of case study research, including:

- In-depth exploration: Case study research allows for a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. This can provide a comprehensive understanding of the case and its dynamics, which may not be possible through other research methods.

- Rich data: Case study research can generate rich and detailed data, including qualitative data such as interviews, observations, and documents. This can provide a nuanced understanding of the case and its complexity.

- Holistic perspective: Case study research allows for a holistic perspective of the case, taking into account the various factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Theory development: Case study research can help to develop and refine theories and concepts by providing empirical evidence and concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Practical application: Case study research can inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

- Contextualization: Case study research takes into account the specific context in which the case is situated, which can help to understand how the case is influenced by the social, cultural, and historical factors of its environment.

Limitations of Case Study Research

There are several limitations of case study research, including:

- Limited generalizability : Case studies are typically focused on a single case or a small number of cases, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The unique characteristics of the case may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, which may limit the external validity of the research.

- Biased sampling: Case studies may rely on purposive or convenience sampling, which can introduce bias into the sample selection process. This may limit the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings.

- Subjectivity: Case studies rely on the interpretation of the researcher, which can introduce subjectivity into the analysis. The researcher’s own biases, assumptions, and perspectives may influence the findings, which may limit the objectivity of the research.

- Limited control: Case studies are typically conducted in naturalistic settings, which limits the control that the researcher has over the environment and the variables being studied. This may limit the ability to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Time-consuming: Case studies can be time-consuming to conduct, as they typically involve a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific case. This may limit the feasibility of conducting multiple case studies or conducting case studies in a timely manner.

- Resource-intensive: Case studies may require significant resources, including time, funding, and expertise. This may limit the ability of researchers to conduct case studies in resource-constrained settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is a Case Study?

Weighing the pros and cons of this method of research

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

Verywell / Colleen Tighe

- Pros and Cons

What Types of Case Studies Are Out There?

Where do you find data for a case study, how do i write a psychology case study.

A case study is an in-depth study of one person, group, or event. In a case study, nearly every aspect of the subject's life and history is analyzed to seek patterns and causes of behavior. Case studies can be used in many different fields, including psychology, medicine, education, anthropology, political science, and social work.

The point of a case study is to learn as much as possible about an individual or group so that the information can be generalized to many others. Unfortunately, case studies tend to be highly subjective, and it is sometimes difficult to generalize results to a larger population.

While case studies focus on a single individual or group, they follow a format similar to other types of psychology writing. If you are writing a case study, we got you—here are some rules of APA format to reference.

At a Glance

A case study, or an in-depth study of a person, group, or event, can be a useful research tool when used wisely. In many cases, case studies are best used in situations where it would be difficult or impossible for you to conduct an experiment. They are helpful for looking at unique situations and allow researchers to gather a lot of˜ information about a specific individual or group of people. However, it's important to be cautious of any bias we draw from them as they are highly subjective.

What Are the Benefits and Limitations of Case Studies?

A case study can have its strengths and weaknesses. Researchers must consider these pros and cons before deciding if this type of study is appropriate for their needs.

One of the greatest advantages of a case study is that it allows researchers to investigate things that are often difficult or impossible to replicate in a lab. Some other benefits of a case study:

- Allows researchers to capture information on the 'how,' 'what,' and 'why,' of something that's implemented

- Gives researchers the chance to collect information on why one strategy might be chosen over another

- Permits researchers to develop hypotheses that can be explored in experimental research

On the other hand, a case study can have some drawbacks:

- It cannot necessarily be generalized to the larger population

- Cannot demonstrate cause and effect

- It may not be scientifically rigorous

- It can lead to bias

Researchers may choose to perform a case study if they want to explore a unique or recently discovered phenomenon. Through their insights, researchers develop additional ideas and study questions that might be explored in future studies.

It's important to remember that the insights from case studies cannot be used to determine cause-and-effect relationships between variables. However, case studies may be used to develop hypotheses that can then be addressed in experimental research.

Case Study Examples

There have been a number of notable case studies in the history of psychology. Much of Freud's work and theories were developed through individual case studies. Some great examples of case studies in psychology include:

- Anna O : Anna O. was a pseudonym of a woman named Bertha Pappenheim, a patient of a physician named Josef Breuer. While she was never a patient of Freud's, Freud and Breuer discussed her case extensively. The woman was experiencing symptoms of a condition that was then known as hysteria and found that talking about her problems helped relieve her symptoms. Her case played an important part in the development of talk therapy as an approach to mental health treatment.

- Phineas Gage : Phineas Gage was a railroad employee who experienced a terrible accident in which an explosion sent a metal rod through his skull, damaging important portions of his brain. Gage recovered from his accident but was left with serious changes in both personality and behavior.

- Genie : Genie was a young girl subjected to horrific abuse and isolation. The case study of Genie allowed researchers to study whether language learning was possible, even after missing critical periods for language development. Her case also served as an example of how scientific research may interfere with treatment and lead to further abuse of vulnerable individuals.

Such cases demonstrate how case research can be used to study things that researchers could not replicate in experimental settings. In Genie's case, her horrific abuse denied her the opportunity to learn a language at critical points in her development.

This is clearly not something researchers could ethically replicate, but conducting a case study on Genie allowed researchers to study phenomena that are otherwise impossible to reproduce.

There are a few different types of case studies that psychologists and other researchers might use:

- Collective case studies : These involve studying a group of individuals. Researchers might study a group of people in a certain setting or look at an entire community. For example, psychologists might explore how access to resources in a community has affected the collective mental well-being of those who live there.

- Descriptive case studies : These involve starting with a descriptive theory. The subjects are then observed, and the information gathered is compared to the pre-existing theory.

- Explanatory case studies : These are often used to do causal investigations. In other words, researchers are interested in looking at factors that may have caused certain things to occur.

- Exploratory case studies : These are sometimes used as a prelude to further, more in-depth research. This allows researchers to gather more information before developing their research questions and hypotheses .

- Instrumental case studies : These occur when the individual or group allows researchers to understand more than what is initially obvious to observers.

- Intrinsic case studies : This type of case study is when the researcher has a personal interest in the case. Jean Piaget's observations of his own children are good examples of how an intrinsic case study can contribute to the development of a psychological theory.

The three main case study types often used are intrinsic, instrumental, and collective. Intrinsic case studies are useful for learning about unique cases. Instrumental case studies help look at an individual to learn more about a broader issue. A collective case study can be useful for looking at several cases simultaneously.

The type of case study that psychology researchers use depends on the unique characteristics of the situation and the case itself.

There are a number of different sources and methods that researchers can use to gather information about an individual or group. Six major sources that have been identified by researchers are:

- Archival records : Census records, survey records, and name lists are examples of archival records.

- Direct observation : This strategy involves observing the subject, often in a natural setting . While an individual observer is sometimes used, it is more common to utilize a group of observers.

- Documents : Letters, newspaper articles, administrative records, etc., are the types of documents often used as sources.

- Interviews : Interviews are one of the most important methods for gathering information in case studies. An interview can involve structured survey questions or more open-ended questions.

- Participant observation : When the researcher serves as a participant in events and observes the actions and outcomes, it is called participant observation.

- Physical artifacts : Tools, objects, instruments, and other artifacts are often observed during a direct observation of the subject.

If you have been directed to write a case study for a psychology course, be sure to check with your instructor for any specific guidelines you need to follow. If you are writing your case study for a professional publication, check with the publisher for their specific guidelines for submitting a case study.

Here is a general outline of what should be included in a case study.

Section 1: A Case History

This section will have the following structure and content:

Background information : The first section of your paper will present your client's background. Include factors such as age, gender, work, health status, family mental health history, family and social relationships, drug and alcohol history, life difficulties, goals, and coping skills and weaknesses.

Description of the presenting problem : In the next section of your case study, you will describe the problem or symptoms that the client presented with.

Describe any physical, emotional, or sensory symptoms reported by the client. Thoughts, feelings, and perceptions related to the symptoms should also be noted. Any screening or diagnostic assessments that are used should also be described in detail and all scores reported.

Your diagnosis : Provide your diagnosis and give the appropriate Diagnostic and Statistical Manual code. Explain how you reached your diagnosis, how the client's symptoms fit the diagnostic criteria for the disorder(s), or any possible difficulties in reaching a diagnosis.

Section 2: Treatment Plan

This portion of the paper will address the chosen treatment for the condition. This might also include the theoretical basis for the chosen treatment or any other evidence that might exist to support why this approach was chosen.

- Cognitive behavioral approach : Explain how a cognitive behavioral therapist would approach treatment. Offer background information on cognitive behavioral therapy and describe the treatment sessions, client response, and outcome of this type of treatment. Make note of any difficulties or successes encountered by your client during treatment.

- Humanistic approach : Describe a humanistic approach that could be used to treat your client, such as client-centered therapy . Provide information on the type of treatment you chose, the client's reaction to the treatment, and the end result of this approach. Explain why the treatment was successful or unsuccessful.

- Psychoanalytic approach : Describe how a psychoanalytic therapist would view the client's problem. Provide some background on the psychoanalytic approach and cite relevant references. Explain how psychoanalytic therapy would be used to treat the client, how the client would respond to therapy, and the effectiveness of this treatment approach.

- Pharmacological approach : If treatment primarily involves the use of medications, explain which medications were used and why. Provide background on the effectiveness of these medications and how monotherapy may compare with an approach that combines medications with therapy or other treatments.

This section of a case study should also include information about the treatment goals, process, and outcomes.

When you are writing a case study, you should also include a section where you discuss the case study itself, including the strengths and limitiations of the study. You should note how the findings of your case study might support previous research.

In your discussion section, you should also describe some of the implications of your case study. What ideas or findings might require further exploration? How might researchers go about exploring some of these questions in additional studies?

Need More Tips?

Here are a few additional pointers to keep in mind when formatting your case study:

- Never refer to the subject of your case study as "the client." Instead, use their name or a pseudonym.

- Read examples of case studies to gain an idea about the style and format.

- Remember to use APA format when citing references .

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011;11:100.

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011 Jun 27;11:100. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Gagnon, Yves-Chantal. The Case Study as Research Method: A Practical Handbook . Canada, Chicago Review Press Incorporated DBA Independent Pub Group, 2010.

Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . United States, SAGE Publications, 2017.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 30 January 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organisation, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating, and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyse the case.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

Unlike quantitative or experimental research, a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

If you find yourself aiming to simultaneously investigate and solve an issue, consider conducting action research . As its name suggests, action research conducts research and takes action at the same time, and is highly iterative and flexible.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience, or phenomenon.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews, observations, and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data .

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis, with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results , and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyse its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, January 30). Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved 2 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/case-studies/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, correlational research | guide, design & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, descriptive research design | definition, methods & examples.

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of case study

Examples of case study in a sentence.

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'case study.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

1914, in the meaning defined at sense 1

Dictionary Entries Near case study

case spring

case study method

Cite this Entry

“Case study.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/case%20study. Accessed 6 Apr. 2024.

More from Merriam-Webster on case study

Thesaurus: All synonyms and antonyms for case study

Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about case study

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

The tangled history of 'it's' and 'its', more commonly misspelled words, why does english have so many silent letters, your vs. you're: how to use them correctly, every letter is silent, sometimes: a-z list of examples, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - apr. 5, 12 bird names that sound like compliments, 10 scrabble words without any vowels, 12 more bird names that sound like insults (and sometimes are), 8 uncommon words related to love, games & quizzes.

We use essential cookies to make Venngage work. By clicking “Accept All Cookies”, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts.

Manage Cookies

Cookies and similar technologies collect certain information about how you’re using our website. Some of them are essential, and without them you wouldn’t be able to use Venngage. But others are optional, and you get to choose whether we use them or not.

Strictly Necessary Cookies

These cookies are always on, as they’re essential for making Venngage work, and making it safe. Without these cookies, services you’ve asked for can’t be provided.

Show cookie providers

- Google Login

Functionality Cookies

These cookies help us provide enhanced functionality and personalisation, and remember your settings. They may be set by us or by third party providers.

Performance Cookies

These cookies help us analyze how many people are using Venngage, where they come from and how they're using it. If you opt out of these cookies, we can’t get feedback to make Venngage better for you and all our users.

- Google Analytics

Targeting Cookies

These cookies are set by our advertising partners to track your activity and show you relevant Venngage ads on other sites as you browse the internet.

- Google Tag Manager

- Infographics

- Daily Infographics

- Graphic Design

- Graphs and Charts

- Data Visualization

- Human Resources

- Training and Development

- Beginner Guides

Blog Beginner Guides

What is a Case Study? [+6 Types of Case Studies]

By Ronita Mohan , Sep 20, 2021

Case studies have become powerful business tools. But what is a case study? What are the benefits of creating one? Are there limitations to the format?

If you’ve asked yourself these questions, our helpful guide will clear things up. Learn how to use a case study for business. Find out how cases analysis works in psychology and research.

We’ve also got examples of case studies to inspire you.

Haven’t made a case study before? You can easily create a case study with Venngage’s customizable templates.

CREATE A CASE STUDY

Click to jump ahead:

What is a case study, what is the case study method, benefits of case studies, limitations of case studies, types of case studies, faqs about case studies.

Case studies are research methodologies. They examine subjects, projects, or organizations to tell a story.

USE THIS TEMPLATE

Numerous sectors use case analyses. The social sciences, social work, and psychology create studies regularly.

Healthcare industries write reports on patients and diagnoses. Marketing case study examples , like the one below, highlight the benefits of a business product.

CREATE THIS REPORT TEMPLATE

Now that you know what a case study is, we explain how case reports are used in three different industries.

What is a business case study?

A business or marketing case study aims at showcasing a successful partnership. This can be between a brand and a client. Or the case study can examine a brand’s project.

There is a perception that case studies are used to advertise a brand. But effective reports, like the one below, can show clients how a brand can support them.

Hubspot created a case study on a customer that successfully scaled its business. The report outlines the various Hubspot tools used to achieve these results.

Hubspot also added a video with testimonials from the client company’s employees.

So, what is the purpose of a case study for businesses? There is a lot of competition in the corporate world. Companies are run by people. They can be on the fence about which brand to work with.

Business reports stand out aesthetically, as well. They use brand colors and brand fonts . Usually, a combination of the client’s and the brand’s.

With the Venngage My Brand Kit feature, businesses can automatically apply their brand to designs.

A business case study, like the one below, acts as social proof. This helps customers decide between your brand and your competitors.

Don’t know how to design a report? You can learn how to write a case study with Venngage’s guide. We also share design tips and examples that will help you convert.

Related: 55+ Annual Report Design Templates, Inspirational Examples & Tips [Updated]

What is a case study in psychology?

In the field of psychology, case studies focus on a particular subject. Psychology case histories also examine human behaviors.

Case reports search for commonalities between humans. They are also used to prescribe further research. Or these studies can elaborate on a solution for a behavioral ailment.

The American Psychology Association has a number of case studies on real-life clients. Note how the reports are more text-heavy than a business case study.

Famous psychologists such as Sigmund Freud and Anna O popularised the use of case studies in the field. They did so by regularly interviewing subjects. Their detailed observations build the field of psychology.

It is important to note that psychological studies must be conducted by professionals. Psychologists, psychiatrists and therapists should be the researchers in these cases.

Related: What Netflix’s Top 50 Shows Can Teach Us About Font Psychology [Infographic]

What is a case study in research?

Research is a necessary part of every case study. But specific research fields are required to create studies. These fields include user research, healthcare, education, or social work.

For example, this UX Design report examined the public perception of a client. The brand researched and implemented new visuals to improve it. The study breaks down this research through lessons learned.

Clinical reports are a necessity in the medical field. These documents are used to share knowledge with other professionals. They also help examine new or unusual diseases or symptoms.

The pandemic has led to a significant increase in research. For example, Spectrum Health studied the value of health systems in the pandemic. They created the study by examining community outreach.

The pandemic has significantly impacted the field of education. This has led to numerous examinations on remote studying. There have also been studies on how students react to decreased peer communication.

Social work case reports often have a community focus. They can also examine public health responses. In certain regions, social workers study disaster responses.

You now know what case studies in various fields are. In the next step of our guide, we explain the case study method.

Return to Table of Contents

A case analysis is a deep dive into a subject. To facilitate this case studies are built on interviews and observations. The below example would have been created after numerous interviews.

Case studies are largely qualitative. They analyze and describe phenomena. While some data is included, a case analysis is not quantitative.

There are a few steps in the case method. You have to start by identifying the subject of your study. Then determine what kind of research is required.

In natural sciences, case studies can take years to complete. Business reports, like this one, don’t take that long. A few weeks of interviews should be enough.

The case method will vary depending on the industry. Reports will also look different once produced.

As you will have seen, business reports are more colorful. The design is also more accessible . Healthcare and psychology reports are more text-heavy.

Designing case reports takes time and energy. So, is it worth taking the time to write them? Here are the benefits of creating case studies.

- Collects large amounts of information

- Helps formulate hypotheses

- Builds the case for further research

- Discovers new insights into a subject

- Builds brand trust and loyalty

- Engages customers through stories

For example, the business study below creates a story around a brand partnership. It makes for engaging reading. The study also shows evidence backing up the information.

We’ve shared the benefits of why studies are needed. We will also look at the limitations of creating them.

Related: How to Present a Case Study like a Pro (With Examples)

There are a few disadvantages to conducting a case analysis. The limitations will vary according to the industry.

- Responses from interviews are subjective

- Subjects may tailor responses to the researcher

- Studies can’t always be replicated

- In certain industries, analyses can take time and be expensive

- Risk of generalizing the results among a larger population

These are some of the common weaknesses of creating case reports. If you’re on the fence, look at the competition in your industry.

Other brands or professionals are building reports, like this example. In that case, you may want to do the same.

There are six common types of case reports. Depending on your industry, you might use one of these types.

Descriptive case studies

Explanatory case studies, exploratory case reports, intrinsic case studies, instrumental case studies, collective case reports.

USE THIS TEMPLATE

We go into more detail about each type of study in the guide below.

Related: 15+ Professional Case Study Examples [Design Tips + Templates]

When you have an existing hypothesis, you can design a descriptive study. This type of report starts with a description. The aim is to find connections between the subject being studied and a theory.

Once these connections are found, the study can conclude. The results of this type of study will usually suggest how to develop a theory further.

A study like the one below has concrete results. A descriptive report would use the quantitative data as a suggestion for researching the subject deeply.

When an incident occurs in a field, an explanation is required. An explanatory report investigates the cause of the event. It will include explanations for that cause.

The study will also share details about the impact of the event. In most cases, this report will use evidence to predict future occurrences. The results of explanatory reports are definitive.

Note that there is no room for interpretation here. The results are absolute.

The study below is a good example. It explains how one brand used the services of another. It concludes by showing definitive proof that the collaboration was successful.

Another example of this study would be in the automotive industry. If a vehicle fails a test, an explanatory study will examine why. The results could show that the failure was because of a particular part.

Related: How to Write a Case Study [+ Design Tips]

An explanatory report is a self-contained document. An exploratory one is only the beginning of an investigation.

Exploratory cases act as the starting point of studies. This is usually conducted as a precursor to large-scale investigations. The research is used to suggest why further investigations are needed.

An exploratory study can also be used to suggest methods for further examination.

For example, the below analysis could have found inconclusive results. In that situation, it would be the basis for an in-depth study.

Intrinsic studies are more common in the field of psychology. These reports can also be conducted in healthcare or social work.

These types of studies focus on a unique subject, such as a patient. They can sometimes study groups close to the researcher.

The aim of such studies is to understand the subject better. This requires learning their history. The researcher will also examine how they interact with their environment.

For instance, if the case study below was about a unique brand, it could be an intrinsic study.

Once the study is complete, the researcher will have developed a better understanding of a phenomenon. This phenomenon will likely not have been studied or theorized about before.

Examples of intrinsic case analysis can be found across psychology. For example, Jean Piaget’s theories on cognitive development. He established the theory from intrinsic studies into his own children.

Related: What Disney Villains Can Tell Us About Color Psychology [Infographic]

This is another type of study seen in medical and psychology fields. Instrumental reports are created to examine more than just the primary subject.

When research is conducted for an instrumental study, it is to provide the basis for a larger phenomenon. The subject matter is usually the best example of the phenomenon. This is why it is being studied.

Assume it’s examining lead generation strategies. It may want to show that visual marketing is the definitive lead generation tool. The brand can conduct an instrumental case study to examine this phenomenon.

Collective studies are based on instrumental case reports. These types of studies examine multiple reports.

There are a number of reasons why collective reports are created:

- To provide evidence for starting a new study

- To find pattens between multiple instrumental reports

- To find differences in similar types of cases

- Gain a deeper understanding of a complex phenomenon

- Understand a phenomenon from diverse contexts

A researcher could use multiple reports, like the one below, to build a collective case report.

Related: 10+ Case Study Infographic Templates That Convert

What makes a case study a case study?

A case study has a very particular research methodology. They are an in-depth study of a person or a group of individuals. They can also study a community or an organization. Case reports examine real-world phenomena within a set context.

How long should a case study be?

The length of studies depends on the industry. It also depends on the story you’re telling. Most case studies should be at least 500-1500 words long. But you can increase the length if you have more details to share.

What should you ask in a case study?

The one thing you shouldn’t ask is ‘yes’ or ‘no’ questions. Case studies are qualitative. These questions won’t give you the information you need.

Ask your client about the problems they faced. Ask them about solutions they found. Or what they think is the ideal solution. Leave room to ask them follow-up questions. This will help build out the study.

How to present a case study?

When you’re ready to present a case study, begin by providing a summary of the problem or challenge you were addressing. Follow this with an outline of the solution you implemented, and support this with the results you achieved, backed by relevant data. Incorporate visual aids like slides, graphs, and images to make your case study presentation more engaging and impactful.

Now you know what a case study means, you can begin creating one. These reports are a great tool for analyzing brands. They are also useful in a variety of other fields.

Use a visual communication platform like Venngage to design case studies. With Venngage’s templates, you can design easily. Create branded, engaging reports, all without design experience.

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Meaning of case study in English

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

- anti-narrative

- be another story idiom

- bodice-ripper

- cautionary tale

- misdescription

- multi-stranded

- running commentary phrase

- semi-legendary

- shaggy-dog story

- short story

- write something up

case study | Intermediate English

Case study | business english, examples of case study, translations of case study.

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

your bread and butter

a job or activity that provides you with the money you need to live

Shoots, blooms and blossom: talking about plants

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- English Noun

- Intermediate Noun

- Business Noun

- Translations

- All translations

Add case study to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

Hey there! Free trials are available for Standard and Essentials plans. Start for free today.

What Is a Case Study and Why You Should Use Them

Case studies can provide more insights into your business while helping you conduct further research with robust qualitative data analysis to learn more.

If you're in charge of running a company, then you're likely always looking for new ways to run your business more efficiently and increase your customer base while streamlining as many processes as possible.

Unfortunately, it can sometimes be difficult to determine how to go about implementing the proper program in order to be successful. This is why many business owners opt to conduct a case study, which can help significantly. Whether you've been struggling with brand consistency or some other problem, the right case study can identify why your problem exists as well as provide a way to rectify it.

A case study is a great tool that many businesses aren't even aware exists, and there are marketing experts like Mailchimp who can provide you with step-by-step assistance with implementing a plan with a case study. Many companies discover that not only do they need to start a blog in order to improve business, but they also need to create specific and relevant blog titles.

If your company already has a blog, then optimizing your blog posts may be helpful. Regardless of the obstacles that are preventing you from achieving all your professional goals, a case study can work wonders in helping you reverse this issue.

What is a case study?

A case study is a comprehensive report of the results of theory testing or examining emerging themes of a business in real life context. Case studies are also often used in the healthcare industry, conducting health services research with primary research interest around routinely collected healthcare data.

However, for businesses, the purpose of a case study is to help small business owners or company leaders identify the issues and conduct further research into what may be preventing success through information collection, client or customer interviews, and in-depth data analysis.

Knowing the case study definition is crucial for any business owner. By identifying the issues that are hindering a company from achieving all its goals, it's easier to make the necessary corrections to promote success through influenced data collection.

Why are case studies important?

Now that we've answered the questions, "what is a case study?" Why are case studies important? Some of the top reasons why case studies are important include:

- Understand complex issues: Even after you conduct a significant amount of market research , you might have a difficult time understanding exactly what it means. While you might have the basics down, conducting a case study can help you see how that information is applied. Then, when you see how the information can make a difference in business decisions, it could make it easier to understand complex issues.

- Collect data: A case study can also help with data tracking . A case study is a data collection method that can help you describe the information that you have available to you. Then, you can present that information in a way the reader can understand.

- Conduct evaluations: As you learn more about how to write a case study, remember that you can also use a case study to conduct evaluations of a specific situation. A case study is a great way to learn more about complex situations, and you can evaluate how various people responded in that situation. By conducting a case study evaluation, you can learn more about what has worked well, what has not, and what you might want to change in the future.

- Identify potential solutions: A case study can also help you identify solutions to potential problems. If you have an issue in your business that you are trying to solve, you may be able to take a look at a case study where someone has dealt with a similar situation in the past. For example, you may uncover data bias in a specific solution that you would like to address when you tackle the issue on your own. If you need help solving a difficult problem, a case study may be able to help you.

Remember that you can also use case studies to target your audience . If you want to show your audience that you have a significant level of expertise in a field, you may want to publish some case studies that you have handled in the past. Then, when your audience sees that you have had success in a specific area, they may be more likely to provide you with their business. In essence, case studies can be looked at as the original method of social proof, showcasing exactly how you can help someone solve their problems.

What are the benefits of writing a business case study?

Although writing a case study can seem like a tedious task, there are many benefits to conducting one through an in depth qualitative research process.

- Industry understanding: First of all, a case study can give you an in-depth understanding of your industry through a particular conceptual framework and help you identify hidden problems that are preventing you from transcending into the business world.

- Develop theories: If you decide to write a business case study, it provides you with an opportunity to develop new theories. You might have a theory about how to solve a specific problem, but you need to write a business case study to see exactly how that theory has unfolded in the past. Then, you can figure out if you want to apply your theory to a similar issue in the future.

- Evaluate interventions: When you write a business case study that focuses on a specific situation you have been through in the past, you can uncover whether that intervention was truly helpful. This can make it easier to figure out whether you want to use the same intervention in a similar situation in the future.

- Identify best practices: If you want to stay on top of the best practices in your field, conducting case studies can help by allowing you to identify patterns and trends and develop a new list of best practices that you can follow in the future.

- Versatility: Writing a case study also provides you with more versatility. If you want to expand your business applications, you need to figure out how you respond to various problems. When you run a business case study, you open the door to new opportunities, new applications, and new techniques that could help you make a difference in your business down the road.

- Solve problems: Writing a great case study can dramatically improve your chances of reversing your problem and improving your business.

- These are just a few of the biggest benefits you might experience if you decide to publish your case studies. They can be an effective tool for learning, showcasing your talents, and teaching some of your other employees. If you want to grow your audience , you may want to consider publishing some case studies.

What are the limitations of case studies?

Case studies can be a wonderful tool for any business of any size to use to gain an in-depth understanding of their clients, products, customers, or services, but there are limitations.

One limitation of case studies is the fact that, unless there are other recently published examples, there is nothing to compare them to since, most of the time, you are conducting a single, not multiple, case studies.

Another limitation is the fact that most case studies can lack scientific evidence.

Types of case studies

There are specific types of case studies to choose from, and each specific type will yield different results. Some case study types even overlap, which is sometimes more favorable, as they provide even more pertinent data.

Here are overviews of the different types of case studies, each with its own theoretical framework, so you can determine which type would be most effective for helping you meet your goals.

Explanatory case studies

Explanatory case studies are pretty straightforward, as they're not difficult to interpret. This type of case study is best if there aren't many variables involved because explanatory case studies can easily answer questions like "how" and "why" through theory development.

Exploratory case studies

An exploratory case study does exactly what its name implies: it goes into specific detail about the topic at hand in a natural, real-life context with qualitative research.

The benefits of exploratory case studies are limitless, with the main one being that it offers a great deal of flexibility. Having flexibility when writing a case study is important because you can't always predict what obstacles might arise during the qualitative research process.

Collective case studies

Collective case studies require you to study many different individuals in order to obtain usable data.

Case studies that involve an investigation of people will involve many different variables, all of which can't be predicted. Despite this fact, there are many benefits of collective case studies, including the fact that it allows an ongoing analysis of the data collected.

Intrinsic case studies

This type of study differs from the others as it focuses on the inquiry of one specific instance among many possibilities.

Many people prefer these types of case studies because it allows them to learn about the particular instance that they wish to investigate further.

Instrumental case studies

An instrumental case study is similar to an intrinsic one, as it focuses on a particular instance, whether it's a person, organization, or something different.

One thing that differentiates instrumental case studies from intrinsic ones is the fact that instrumental case studies aren't chosen merely because a person is interested in learning about a specific instance.

Tips for writing a case study

If you have decided to write case studies for your company, then you may be unsure of where to start or which type to conduct.

However, it doesn't have to be difficult or confusing to begin conducting a case study that will help you identify ways to improve your business.

Here are some helpful tips for writing your case studies:

1. Your case study must be written in the proper format

When writing a case study, the format that you should be similar to this:

Administrative summary

The executive summary is an overview of what your report will contain, written in a concise manner while providing real-life context.

Despite the fact that the executive summary should appear at the beginning of your case studies, it shouldn't be written until you've completed the entire report because if you write it before you finish the report, this summary may not be completely accurate.

Key problem statement

In this section of your case study, you will briefly describe the problem that you hope to solve by conducting the study. You will have the opportunity to elaborate on the problem that you're focusing on as you get into the breadth of the report.

Problem exploration

This part of the case study isn't as brief as the other two, and it goes into more detail about the problem at hand. Your problem exploration must include why the identified problem needs to be solved as well as the urgency of solving it.

Additionally, it must include justification for conducting the problem-solving, as the benefits must outweigh the efforts and costs.

Proposed resolution

This case study section will also be lengthier than the first two. It must include how you propose going about rectifying the problem. The "recommended solution" section must also include potential obstacles that you might experience, as well as how these will be managed.

Furthermore, you will need to list alternative solutions and explain the reason the chosen solution is best. Charts can enhance your report and make it easier to read, and provide as much proof to substantiate your claim as possible.

Overview of monetary consideration

An overview of monetary consideration is essential for all case studies, as it will be used to convince all involved parties why your project should be funded. You must successfully convince them that the cost is worth the investment it will require. It's important that you stress the necessity for this particular case study and explain the expected outcome.

Execution timeline

In the execution times of case studies, you explain how long you predict it will take to implement your study. The shorter the time it will take to implement your plan, the more apt it is to be approved. However, be sure to provide a reasonable timeline, taking into consideration any additional time that might be needed due to obstacles.

Always include a conclusion in your case study. This is where you will briefly wrap up your entire proposal, stressing the benefits of completing the data collection and data analysis in order to rectify your problem.

2. Make it clear and comprehensive

You want to write your case studies with as much clarity as possible so that every aspect of the report is understood. Be sure to double-check your grammar, spelling, punctuation, and more, as you don't want to submit a poorly-written document.

Not only would a poorly-written case study fail to prove that what you are trying to achieve is important, but it would also increase the chances that your report will be tossed aside and not taken seriously.

3. Don't rush through the process

Writing the perfect case study takes time and patience. Rushing could result in your forgetting to include information that is crucial to your entire study. Don't waste your time creating a study that simply isn't ready. Take the necessary time to perform all the research necessary to write the best case study possible.

Depending on the case study, conducting case study research could mean using qualitative methods, quantitative methods, or both. Qualitative research questions focus on non-numerical data, such as how people feel, their beliefs, their experiences, and so on.

Meanwhile, quantitative research questions focus on numerical or statistical data collection to explain causal links or get an in-depth picture.

It is also important to collect insightful and constructive feedback. This will help you better understand the outcome as well as any changes you need to make to future case studies. Consider using formal and informal ways to collect feedback to ensure that you get a range of opinions and perspectives.

4. Be confident in your theory development

While writing your case study or conducting your formal experimental investigation, you should have confidence in yourself and what you're proposing in your report. If you took the time to gather all the pertinent data collected to complete the report, don't second-guess yourself or doubt your abilities. If you believe your report will be amazing, then it likely will be.

5. Case studies and all qualitative research are long

It's expected that multiple case studies are going to be incredibly boring, and there is no way around this. However, it doesn't mean you can choose your language carefully in order to keep your audience as engaged as possible.

If your audience loses interest in your case study at the beginning, for whatever reason, then this increases the likelihood that your case study will not be funded.

Case study examples

If you want to learn more about how to write a case study, it might be beneficial to take a look at a few case study examples. Below are a few interesting case study examples you may want to take a closer look at.

- Phineas Gage by John Martin Marlow : One of the most famous case studies comes from the medical field, and it is about the story of Phineas Gage, a man who had a railroad spike driven through his head in 1848. As he was working on a railroad, an explosive charge went off prematurely, sending a railroad rod through his head. Even though he survived this incident, he lost his left eye. However, Phineas Gage was studied extensively over the years because his experiences had a significant, lasting impact on his personality. This served as a case study because his injury showed different parts of the brain have different functions.

- Kitty Genovese and the bystander effect : This is a tragic case study that discusses the murder of Kitty Genovese, a woman attacked and murdered in Queens, New York City. Shockingly, while numerous neighbors watched the scene, nobody called for help because they assumed someone else would. This case study helped to define the bystander effect, which is when a person fails to intervene during an emergency because other people are around.