- Business & Money

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

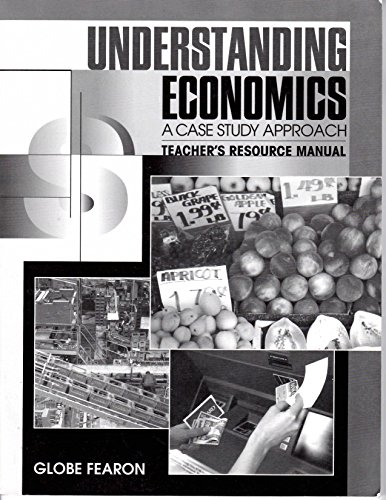

Understanding Economics: A Case Study Approach Paperback – January 1, 1997

- Print length 188 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Globe Fearon

- Publication date January 1, 1997

- Grade level 7 - 9

- Dimensions 8.5 x 0.5 x 11 inches

- ISBN-10 0835918106

- ISBN-13 978-0835918107

- See all details

Product details

- Publisher : Globe Fearon (January 1, 1997)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 188 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0835918106

- ISBN-13 : 978-0835918107

- Grade level : 7 - 9

- Item Weight : 1.25 pounds

- Dimensions : 8.5 x 0.5 x 11 inches

- #45,509 in Economics (Books)

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Connect with Us

- Entertainment

- Gadgets Review

- Government Schemes

- Make Money Online

- Product Review

- Uncategorized

Solving Case Study in Economics: A Complete Guide

case study in economics

Case studies are invaluable in economics education, providing students with real-world scenarios to apply theoretical concepts and analytical skills. However, solving a case study in economics requires a structured approach that combines research, critical thinking, and a deep understanding of economic principles. This post presents a comprehensive guide on effectively solving a case study in economics , ensuring a thorough analysis and a grasp of practical implications.

Understanding the Case Study

Read carefully: .

Begin by reading the case study thoroughly. Pay attention to the details, context, and objectives presented. Identify the main issues, stakeholders, and the economic concepts at play.

Define the Problem:

Clearly define the economic problem or challenge presented in the case study. What are the fundamental problems that ought to be handled? Understanding the problem is crucial before proceeding with analysis.Identify the central economic problem or challenge that the case study presents. This could involve issues related to demand and supply, market structures, externalities, government interventions, or any other economic concept.

Gathering Relevant Information

Research: .

Conduct thorough research to gather additional information relevant to the case study. This may involve exploring economic theories, statistical data, and industry trends. Reliable sources such as academic journals, government reports, and reputable news outlets are valuable.

Identify Variables:

Identify the variables affecting the situation presented in the case study. These could include economic indicators, market conditions, government policies, etc.

Read also: How Trademark Registration Can Help in Business

Applying Economic Concepts

Use relevant theories: .

Apply relevant economic theories and concepts to analyze the case study. Consider concepts like supply and demand, elasticity, market structure, cost analysis, and utility theory, depending on the case context.

Quantitative Analysis:

If applicable, use quantitative methods such as calculations, graphs, and charts to illustrate your analysis. These tools can help visualize economic relationships and trends.

Data Interpretation

Cause and effect:.

Identify the cause-and-effect relationships driving the economic situation in the case study. Analyze how changes in one variable can impact others and lead to specific outcomes.

Consider Alternatives:

Explore solutions or strategies to address the issues presented. Consider the possible benefits and drawbacks of each option.

Making Recommendations

Informed decisions: .

Based on your analysis, make informed recommendations for addressing the challenges outlined in the case study in economics. Your recommendations should be rooted in economic theories and supported by your gathered data.

Justify Your Recommendations:

Clearly explain the rationale behind your recommendations. How will they positively impact the stakeholders involved? Justify your choices with economic logic.

Read also: Best Practices for Workday Financial Management Integration

Tips for Success

Practice: .

The more case studies you solve, the more comfortable you’ll become with the process. Practice hones your analytical skills and enables you to apply economic concepts effectively.

Collaborate:

Engage in discussions with peers or instructors. Collaborative analysis can offer diverse perspectives and deepen your understanding of the case.

Real-World Context:

Relate the case study to real-world economic scenarios. Understanding the practical implications of your analysis adds depth to your recommendations.

Stay Updated:

Case study in economics is a dynamic field. Stay updated with current economic trends, policy changes, and market developments to enhance the relevance of your analysis.

Read the Case Thoroughly

Begin by reading the case study attentively. Familiarize yourself with the context, characters, and economic issues presented. Take notes as you read to highlight key information and identify the main problems.

Apply Relevant Economic Concepts

Next, apply the economic concepts and theories you’ve learned in your coursework to the identified problem. Consider how concepts like elasticity, opportunity cost, marginal analysis, and cost-benefit analysis can be applied to the situation.

Collect Data and Information

Gather relevant data and information that can support your analysis. This may include statistical data, market trends, historical information, and other relevant sources that substantiate your arguments.

Analyze and Evaluate

Conduct a thorough analysis of the situation. Identify the factors contributing to the problem and evaluate their impact. Use graphs, charts, and diagrams to represent your analysis and provide clarity visually.

Explore Alternatives

Generate possible solutions or alternatives to address the identified problem. Consider the pros and cons of each solution, keeping in mind economic feasibility, ethical implications, and potential outcomes.

Apply Economic Theories

When formulating solutions, apply economic theories and principles that align with the situation. For instance, if you’re dealing with a market failure, explore how government intervention or corrective measures can be applied based on economic theories like externalities or public goods.

Quantitative Analysis

If applicable, perform quantitative analysis using relevant mathematical or statistical tools. This could involve calculating elasticity break-even points or analyzing cost structures to support your recommendations.

Justify Your Recommendations

Ensure that your solutions are well-justified and backed by solid economic reasoning. Explain how each solution addresses the problem and aligns with economic theories.

Consider Real-World Constraints

Acknowledge any real-world constraints that might affect the implementation of your recommendations. This could include budgetary limitations, political considerations, or social factors.

Solving an case study in economics writing is an enriching experience that bridges theory and practice. It requires a structured approach, from understanding the case to making well-informed recommendations. By thoroughly analyzing the economic concepts, interpreting data, and applying relevant theories, you can arrive at strategic solutions that align with economic principles.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related News

How to migrate from Wix to WordPress – Ultimate Guide

7 Best Team Collaboration Tools for Remote & In-Person

You may have missed.

How to Personalize Custom Boxes for Special Occasions?

How to Fix NVIDIA GeForce Experience Error Code 0x0003

Style Mastery: Essential Tips for Every Woman’s Occasion

Creating High-Performance Teams for Success

Health and Insurance Bridging the Gap of Technology

UBO Verification: Understand the Ultimate Beneficial Owners

Items related to Understanding Economics: A Case Study Approach

Understanding economics: a case study approach - softcover, globe fearon.

This specific ISBN edition is currently not available.

- About this edition

- Publisher Globe Fearon

- Publication date 1996

- ISBN 10 0835918114

- ISBN 13 9780835918114

- Binding Paperback

- Number of pages 86

(No Available Copies)

- Advanced Search

- AbeBooks Home

If you know the book but cannot find it on AbeBooks, we can automatically search for it on your behalf as new inventory is added. If it is added to AbeBooks by one of our member booksellers, we will notify you!

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

- Children's Books

- Geography & Cultures

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet or computer – no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera, scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video, download Flash Player

Understanding Economics: A Case Study Approach Paperback – Jan. 1 1810

- Language English

- Publication date Jan. 1 1810

- Dimensions 21.59 x 1.27 x 27.94 cm

- ISBN-10 0835918106

- ISBN-13 978-0835918107

- See all details

Product details

- Language : English

- ISBN-10 : 0835918106

- ISBN-13 : 978-0835918107

- Item weight : 567 g

- Dimensions : 21.59 x 1.27 x 27.94 cm

Customer reviews

No customer reviews.

- Amazon and Our Planet

- Investor Relations

- Press Releases

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Sell on Amazon Handmade

- Advertise Your Products

- Independently Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- Amazon.ca Rewards Mastercard

- Shop with Points

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Amazon Cash

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns Are Easy

- Manage your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Customer Service

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Interest-Based Ads

- Amazon.com.ca ULC | 40 King Street W 47th Floor, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5H 3Y2 |1-877-586-3230

- Скидки дня

- Справка и помощь

- Адрес доставки Идет загрузка... Ошибка: повторите попытку ОК

- Продажи

- Список отслеживания Развернуть список отслеживаемых товаров Идет загрузка... Войдите в систему , чтобы просмотреть свои сведения о пользователе

- Краткий обзор

- Недавно просмотренные

- Ставки/предложения

- Список отслеживания

- История покупок

- Купить опять

- Объявления о товарах

- Сохраненные запросы поиска

- Сохраненные продавцы

- Сообщения

- Уведомление

- Развернуть корзину Идет загрузка... Произошла ошибка. Чтобы узнать подробнее, посмотрите корзину.

Product Identifiers

- Publisher Globe Fearon Educational Publishing

- ISBN-10 0835918106

- ISBN-13 9780835918107

- eBay Product ID (ePID) 2575571

Product Key Features

- Book Title Understanding Economics : a Case Study Approach

- Author Not Available

- Format Hardcover

- Language English

- Intended Audience Young Adults

- Number of Pages 192 Pages

- Item Length 11in

- Item Width 8.7in

- Item Weight 19.2 Oz

Additional Product Features

- Age Range 14-17

- Grade from Ninth Grade

- Grade to Twelfth Grade

- Target Audience Young Adult Audience

- Illustrated Yes

Economics Inscribed Study Hardcovers Prep

Economics workbook study hardcovers prep, economics hardcover study guides & test prep, economics hardcover study guides & test prep in english, economics hardcover study guides & test prep personalized, economics hardcover study guides & test prep in japanese.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

A newer edition of this book is available.

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

22 Case Study Research: In-Depth Understanding in Context

Helen Simons, School of Education, University of Southampton

- Published: 01 July 2014

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter explores case study as a major approach to research and evaluation. After first noting various contexts in which case studies are commonly used, the chapter focuses on case study research directly Strengths and potential problematic issues are outlined and then key phases of the process. The chapter emphasizes how important it is to design the case, to collect and interpret data in ways that highlight the qualitative, to have an ethical practice that values multiple perspectives and political interests, and to report creatively to facilitate use in policy making and practice. Finally, it explores how to generalize from the single case. Concluding questions center on the need to think more imaginatively about design and the range of methods and forms of reporting requiredto persuade audiences to value qualitative ways of knowing in case study research.

Introduction

This chapter explores case study as a major approach to research and evaluation using primarily qualitative methods, as well as documentary sources, contemporaneous or historical. However, this is not the only way in which case study can be conceived. No one has a monopoly on the term. While sharing a focus on the singular in a particular context, case study has a wide variety of uses, not all associated with research. A case study, in common parlance, documents a particular situation or event in detail in a specific sociopolitical context. The particular can be a person, a classroom, an institution, a program, or a policy. Below I identify different ways in which case study is used before focusing on qualitative case study research in particular. However, first I wish to indicate how I came to advocate and practice this form of research. Origins, context, and opportunity often shape the research processes we endorse. It is helpful for the reader, I think, to know how I came to the perspective I hold.

The Beginnings

I first came to appreciate and enjoy the virtues of case study research when I entered the field of curriculum evaluation and research in the 1970s. The dominant research paradigm for educational research at that time was experimental or quasi- experimental, cost-benefit, or systems analysis, and the dominant curriculum model was aims and objectives ( House, 1993 ). The field was dominated, in effect, by a psychometric view of research in which quantitative methods were preeminent. But the innovative projects we were asked to evaluate (predominantly, but not exclusively, in the humanities) were not amenable to such methodologies. The projects were challenging to the status quo of institutions, involved people interpreting the policy and programs, were implemented differently in different contexts and regions, and had many unexpected effects.

We had no choice but to seek other ways to evaluate these complex programs, and case study was the methodology we found ourselves exploring, in order to understand how the projects were being implemented, why they had positive effects in some regions of the country and not others, and what the outcomes meant in different sociopolitical and cultural contexts. What better way to do this than to talk with people to see how they interpreted the “new” curriculum; to watch how teachers and students put it into practice; to document transactions, outcomes, and unexpected consequences; and to interpret all in the specific context of the case ( Simons, 1971 , 1987 , pp. 55–89). From this point on and in further studies, case study in educational research and evaluation came to be a major methodology for understanding complex educational and social programs. It also extended to other practice professions, such as nursing, health, and social care ( Zucker, 2001 ; Greenhalgh & Worrall, 1997 ; Shaw & Gould, 2001 ). For further details of the evolution of the case study approach and qualitative methodologies in evaluation, see House, 1993 , pp. 2–3; Greene, 2000 ; Simons, 2009 , pp. 14–18; Simons & McCormack, 2007 , pp. 292–311).

This was not exactly the beginning of case study, of course. It has a long history in many disciplines ( Simons, 1980; Ragin, 1992; Gomm, Hammersley, & Foster, 2004 ; Platt, 2007 ), many aspects of which form part of case study practice to this day. But its evolution in the context just described was a major move in the contemporary evolution of the logic of evaluative inquiry ( House, 1980 ). It also coincided with movement toward the qualitative in other disciplines, such as sociology and psychology. This was all part of what Denzin & Lincoln (1994) termed “a quiet methodological revolution” (p. ix) in qualitative inquiry that had been evolving over the course of forty years.

There is a further reason why I continue to advocate and practice case study research and evaluation to this day and that is my personal predilection for trying to understand and represent complexity, for puzzling through the ambiguities that exist in many contexts and programs and for presenting and negotiating different values and interests in fair and just ways.

Put more simply, I like interacting with people, listening to their stories, trials and tribulations—giving them a voice in understanding the contexts and projects with which they are involved, and finding ways to share these with a range of audiences. In other words, the move toward case study methodology described here suited my preference for how I learn.

Concepts and Purposes of Case Study

Before exploring case study as it has come to be established in educational research and evaluation over the past forty years, I wish to acknowledge other uses of case study. More often than not, these relate to purpose, and appropriately so in their different contexts, but many do not have a research intention. For a study to count as research, it would need to be a systematic investigation generating evidence that leads to “new” knowledge that is made public and open to scrutiny. There are many ways to conduct research stemming from different traditions and disciplines, but they all, in different ways, involve these characteristics.

Everyday Usage: Stories We Tell

The most common of these uses of case study is the everyday reference to a person, an anecdote or story illustrative of a particular incident, event, or experience of that person. It is often a short, reported account commonly seen in journalism but also in books exploring a phenomenon, such as recovery from serious accidents or tragedies, where the author chooses to illustrate the story or argument with a “lived” example. This is sometimes written by the author and sometimes by the person whose tale it is. “Let me share with you a story,” is a phrase frequently heard

The spirit behind this common usage and its power to connect can be seen in a report by Tim Adams of the London Olympics opening ceremony’s dramatization by Danny Boyle.

It was the point when we suddenly collectively wised up to the idea that what we are about to receive over the next two weeks was not only about “legacy collateral” and “targeted deliverables,” not about G4S failings and traffic lanes and branding opportunities, but about the second-by-second possibilities of human endeavour and spirit and communality, enacted in multiple places and all at the same time. Stories in other words. ( Adams, 2012 )

This was a collective story, of course, not an individual one, but it does convey some of the major characteristics of case study—that richness of detail, time, place, multiple happenings and experiences—that are also manifest in case study research, although carefully evidenced in the latter instance. We can see from this common usage how people have come to associate case study with story. I return to this thread in the reporting section.

Professions Individual Cases

In professional settings, in health and social care, case studies, often called case histories , are used to accurately record a person’s health or social care history and his or her current symptoms, experience, and treatment. These case histories include facts but also judgments and observations about the person’s reaction to situations or medication. Usually these are confidential. Not dissimilar is the detailed documentation of a case in law, often termed a case precedent when referred to in a court case to support an argument being made. However in law there is a difference in that such case precedents are publicly documented.

Case Studies in Teaching

Exemplars of practice.

In education, but also in health and social care training contexts, case studies have long been used as exemplars of practice. These are brief descriptions with some detail of a person or project’s experience in an area of practice. Though frequently reported accounts, they are based on a person’s experience and sometimes on previous research.

Case scenarios

Management studies are a further context in which case studies are often used. Here, the case is more like a scenario outlining a particular problem situation for the management student to resolve. These scenarios may be based on research but frequently are hypothetical situations used to raise issues for discussion and resolution. What distinguishes these case scenarios and the case exemplars in education from case study research is the intention to use them for teaching purposes.

Country Case Studies

Then there are case studies of programs, projects, and even countries, as in international development, where a whole-country study might be termed a case study or, in the context of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), where an exploration is conducted of the state of the art of a subject, such as education or environmental science in one or several countries. This may be a contemporaneous study and/or what transpired in a program over a period of time. Such studies often do have a research base but frequently are reported accounts that do not detail the design, methodology, and analysis of the case, as a research case study would do, or report in ways that give readers a vicarious experience of what it was like to be there. Such case studies tend to be more knowledge and information-focused than experiential.

Case Study as History

Closer to a research context is case study as history—what transpired at a certain time in a certain place. This is likely to be supported by documentary evidence but not primary data gathering unless it is an oral history. In education, in the late 1970s, Stenhouse (1978) experimented with a case study archive. Using contemporaneous data gathering, primarily through interviewing, he envisaged this database, which he termed a “case record,” forming an archive from which different individuals,, at some later date, could write a “case study.” This approach uses case study as a documentary source to begin to generate a history of education, as the subtitle of Stenhouse’s 1978 paper indicates “Towards a contemporary history of education.”

Case Study Research

From here on, my focus is on case study research per se, adopting for this purpose the following definition:

Case study is an in-depth exploration from multiple perspectives of the complexity and uniqueness of a particular project, policy, institution or system in a “real-life” context. It is research based, inclusive of different methods and is evidence-led. ( Simons, 2009 , p. 21).

For further related definitions of case study, see Stake (1995) , Merriam (1998), and Chadderton & Torrance (2011) . And for definitions from a slightly different perspective, see Yin (2004) and Thomas (2011a) .

Not Defined by Method or Perspective

The inclusion of different methods in the definition quoted above definition signals that case study research is not defined by methodology or method. What defines case study is its singularity and the concept and boundary of the case. It is theoretically possible to conduct a case study using primarily quantitative data if this is the best way of providing evidence to inform the issues the case is exploring. It is equally possible to conduct case study that is mainly qualitative, to engage people with the experience of the case or to provide a rich portrayal of an event, project, or program.

Or one can design the case using mixed methods. This increases the options for learning from different ways of knowing and is sometimes preferred by stakeholders who believe it provides a firmer basis for informing policy. This is not necessarily the case but is beyond the scope of this chapter to explore. For further discussion of the complexities of mixing methods and the virtue of using qualitative methods and case study in a mixed method design, see Greene (2007) .

Case study research may also be conducted from different standpoints—realist, interpretivist, or constructivist, for example. My perspective falls within a constructivist, interpretivist framework. What interests me is how I and those in the case perceive and interpret what we find and how we construct or co-construct understandings of the case. This not only suits my predilection for how I see the world, but also my preferred phenomenological approach to interviewing and curiosity about people and how they act in social and professional life.

Qualitative Case Study Research

Qualitative case study research shares many characteristics with other forms of qualitative research, such as narrative, oral history, life history, ethnography, in-depth interview, and observational studies that utilize qualitative methods. However, its focus, purpose, and origins, in educational research at least, are a little different.

The focus is clearly the study of the singular. The purpose is to portray an in-depth view of the quality and complexity of social/educational programs or policies as they are implemented in specific sociopolitical contexts. What makes it qualitative is its emphasis on subjective ways of knowing, particularly the experiential, practical, and presentational rather than the propositional ( Heron, 1992 , 1999 ) to comprehend and communicate what transpired in the case.

Characteristic Features and Advantages

Case study research is not method dependent, as noted earlier, nor is it constrained by resources or time. Although it can be conducted over several years, which provides an opportunity to explore the process of change and explain how and why things happened, it can equally be carried out contemporaneously in a few days, weeks, or months. This flexibility is extremely useful in many contexts, particularly when a change in policy or unforeseen issues in the field require modifying the design.

Flexibility extends to reporting. The case can be written up in different lengths and forms to meet different audience needs and to maximize use (see the section on Reporting). Using the natural language of participants and familiar methods (like interview, observation, oral history) also enables participants to engage in the research process, thereby contributing significantly to the generation of knowledge of the case. As I have indicated elsewhere ( Simons, 2009 ), “This is both a political and epistemological point. It signals a potential shift in the power base of who controls knowledge and recognizes the importance of co-constructing perceived reality through the relationships and joint understandings we create in the field” (p. 23).

Possible Disadvantages

If one is an advocate, identifying advantages of a research approach is easier than pointing out its disadvantages, something detractors are quite keen to do anyway! But no approach is perfect, and here are some of the issues that often trouble people about case study research. The “sample of one” is an obvious issue that worries those convinced that only large samples can constitute valid research and especially if this is to inform policy. Understanding complexity in depth may not be a sufficient counterargument, and I suspect there is little point in trying to persuade otherwise For frequently, this perception is one of epistemological and methodological, if not ideological, preference.

However, there are some genuine concerns that many case researchers face: the difficulty of processing a mass of data; of “telling the truth” in contexts where people may be identifiable; personal involvement, when the researcher is the main instrument of data gathering; and writing reports that are data-based, yet readable in style and length. But one issue that concerns advocates and nonadvocates alike is how inferences are drawn from the single case.

Answers to some of these issues are covered in the sections that follow. Whether they convince may again be a question of preference. However, it is worth noting here that I do not think we should seek to justify these concerns in terms identified by other methodologies. Many of them are intrinsic to the nature and strength of qualitative case study research.

Subjectivity, for instance, both of participants and researcher is inevitable, as it is in many other qualitative methodologies. This is often the basis on which we act. Rather than see this as bias or something to counter, it is an intelligence that is essential to understanding and interpreting the experience of participants and stakeholders. Such subjectivity needs to be disciplined, of course, through procedures that examine both the validity of individuals’ representations of “their truth”, and demonstrate how the researcher took a reflexive approach to monitoring how his or her own values and predilections may have unduly influenced the data.

Types of Case Study

There are numerous types of case study, too many to categorize, I think, as there are overlaps between them. However, attempts have been made to do this and, for those who value typologies, I refer them to Bassey (1999) and, for a more extended typology, to Thomas (2011b) . A slightly different approach is taken by Gomm, Hammersley, and Foster (2004) in annotating the different emphases in major texts on case study. What I prefer to do here is to highlight a few familiar types to focus the discussion that follows on the practice of case study research.

Stake (1995) offers a threefold distinction that is helpful when it comes to practice, he says, because it influences the methods we choose to gather data (p. 4). He distinguishes between an intrinsic case study , one that is studied to learn about the particular case itself and an instrumental case study , in which we choose a case to gain insight into a particular issue (i.e., the case is instrumental to understanding something else; p. 3). The collective case study is what its name suggests: an extension of the instrumental to several cases.

Theory-led or theory-generated case study is similarly self-explanatory, the first starting from a specific theory that is tested through the case; the second constructing a theory through interpretation of data generated in the case. In other words, one ends rather than begins with a theory. In qualitative case study research, this is the more familiar route. The theory of the case becomes the argument or story you will tell.

Evaluation case study requires a slightly longer description as this is my context of practice, one which has influenced the way I conduct case study and what I choose to emphasize in this chapter. An evaluation case study has three essential features: to determine the value of the case, to include and balance different interests and values, and to report findings to a range of stakeholders in ways that they can use. The reasons for this may be found in the interlude that follows, which offers a brief characterization of the social and ethical practice of evaluation and why qualitative methods are so important in this practice.

Interlude: Social and Ethical Practice of Evaluation

Evaluation is a social practice that documents, portrays, and seeks to understand the value of a particular project, program, or policy. This can be determined by different evaluation methodologies, of course. But the value of qualitative case study is that it is possible to discern this value without decontextualizing the data. While the focus of the case is usually a project, program, policy, or some unit within, studies of key individuals, what I term case profiles , may be embedded within the overall case. In some instances, these profiles, or even shorter cameos of individuals, may be quite prominent. For it is through the perceptions, interpretations, and interactions of people that we learn how policies and programs are enacted ( Kushner, 2000 , p. 12). The program is still the main focus of analysis, but, in exploring how individuals play out their different roles in the program, we get closer to the actual experience and meaning of the program in practice.

Case study evaluation is often commissioned from an external source (government department or other agency) keen to know the worth of publicly funded programs and policies to inform future decision making. It needs to be responsive to issues or questions identified by stakeholders, who often have different values and interests in the expected outcomes and appreciate different perspectives of the program in action. The context also is often highly politicized, and interests can conflict. The task of the evaluator in such situations becomes one of including and balancing all interests and values in the program fairly and justly.

This is an inherently political process and requires an ethical practice that offers participants some protection over the personal data they give as part of the research and agreed audiences access to the findings, presented in ways they can understand. Negotiating what information becomes public can be quite difficult in singular settings where people are identifiable and intricate or problematic transactions have been documented. The consequences that ensue from making knowledge public that hitherto was private may be considerable for those in the case. It may also be difficult to portray some of the contextual detail that would enhance understanding for readers.

The ethical stance that underpins the case study research and evaluation I conduct stems from a theory of ethics that emphasizes the centrality of relationships in the specific context and the consequences for individuals, while remaining aware of the research imperative to publicly report. It is essentially an independent democratic process based on the concepts of fairness and justice, in which confidentiality, negotiation, and accessibility are key principles ( MacDonald, 1976 ; Simons, 2009 , pp. 96–111; and Simons 2010 ). The principles are translated into specific procedures to guide the collection, validation, and dissemination of data in the field. These include:

engaging participants and stakeholders in identifying issues to explore and sometimes also in interpreting the data;

documenting how different people interpret and value the program;

negotiating what data becomes public respecting both the individual’s “right to privacy” and the public’s “right to know”;

offering participants opportunities to check how their data are used in the context of reporting;

reporting in language and forms accessible to a wide range of audiences;

disseminating to audiences within and beyond the case.

For further discussion of the ethics of democratic case study evaluation and examples of their use in practice, see Simons (2000 , 2006 , 2009 , chapter 6, 2010 ).

Designing Case Study Research

Design issues in case study sometimes take second place to those of data gathering, the more exciting task perhaps in starting research. However, it is critical to consider the design at the outset, even if changes are required in practice due to the reality of what is encountered in the field. In this sense, the design of case study is emergent, rather than preordinate, shaped and reshaped as understanding of the significance of foreshadowed issues emerges and more are discovered.

Before entering the field, there are a myriad of planning issues to think about related to stakeholders, participants, and audiences. These include whose values matter, whether to engage them in data gathering and interpretation, the style of reporting appropriate for each, and the ethical guidelines that will underpin data collection and reporting. However, here I emphasize only three: the broad focus of the study, what the case is a case of, and framing questions/issues. These are steps often ignored in an enthusiasm to gather data, resulting in a case study that claims to be research but lacks the basic principles required for generation of valid, public knowledge.

Conceptualize the Topic

First, it is important that the topic of the research is conceptualized in a way that it can be researched (i.e., it is not too wide). This seems an obvious point to make, but failure to think through precisely what it is about your research topic you wish to investigate will have a knock-on effect on the framing of the case, data gathering, and interpretation and may lead, in some instances, to not gathering or analyzing data that actually informs the topic. Further conceptualization or reconceptualization may be necessary as the study proceeds, but it is critical to have a clear focus at the outset.

What Constitutes the Case

Second, I think it is important to decide what would constitute the case (i.e., what it is a case of) and where the boundaries of this lie. This often proves more difficult than first appears. And sometimes, partly because of the semifluid nature of the way the case evolves, it is only possible to finally establish what the case is a case of at the end. Nevertheless, it is useful to identify what the case and its boundaries are at the outset to help focus data collection while maintaining an awareness that these may shift. This is emergent design in action.

In deciding the boundary of the case, there are several factors to bear in mind. Is it bounded by an institution or a unit within an institution, by people within an institution, by region, or by project, program or policy,? If we take a school as an example, the case could be comprised of the principal, teachers, and students, or the boundary could be extended to the cleaners, the caretaker, the receptionist, people who often know a great deal about the subnorms and culture of the institution.

If the case is a policy or particular parameter of a policy, the considerations may be slightly different. People will still be paramount—those who generated the policy and those who implemented it—but there is likely also to be a political culture surrounding the policy that had an influence on the way the policy evolved. Would this be part of the case?

Whatever boundary is chosen, this may change in the course of conducting the study when issues arise that can only be understood by going to another level. What transpires in a classroom, for example, if this is the case, is often partly dependent on the support of the school leadership and culture of the institution and this, in turn, to some extent is dependent on what resources are allocated from the local education administration. Much like a series of Russian dolls, one context inside the other.

Unit of analysis

Thinking about what would constitute the unit of analysis— a classroom, an institution, a program, a region—may help in setting the boundaries of the case, and it will certainly help when it comes to analysis. But this is a slightly different issue from deciding what the case is a case of. Taking a health example, the case may be palliative care support, but the unit of analysis the palliative care ward or wards. If you took the palliative care ward as the unit of analysis this would be as much about how palliative care was exercised in this or that ward than issues about palliative care support in general. In other words, you would need to have specific information and context about how this ward was structured and managed to understand how palliative care was conducted in this particular ward. Here, as in the school example above, you would need to consider which of the many people who populate the ward form part of the case—nurses, interns, or doctors only, or does it extend to patients, cleaners, nurse aides, and medical students?

Framing Questions and Issues

The third most important consideration is how to frame the study, and you are likely to do this once you have selected the site or sites for study. There are at least four approaches. You could start with precise questions, foreshadowed issues ( Smith & Pohland, 1974 ), theories, or a program logic. To some extent, your choice will be dictated by the type of case you have chosen, but also by your personal preference for how to conduct it—in either a structured or open way.

Initial questions give structure; foreshadowed issues more freedom to explore. In qualitative case study, foreshadowed issues are more common, allowing scope for issues to change as the study evolves, guided by participants’ perspectives and events in the field. With this perspective, it is more likely that you will generate a theory of the case toward the end, through your interpretation and analysis.

If you are conducting an instrumental case study, staying close to the questions or foreshadowed issues is necessary to be sure you gain data that will illuminate the central focus of the study. This is critical if you are exploring issues across several cases, although it is possible to do a cross-case analysis from cases that have each followed a different route to discovering significant issues.

Opting to start with a theoretical framework provides a basis for formulating questions and issues, but it can also constrain the study to only those questions/issues that fit the framework. The same is true with using program logic to frame the case. This is an approach frequently adopted in evaluation case study where the evaluator, individually or with stakeholders, examines how the aims and objectives of the program relate to the activities designed to promote it and the outcomes and impacts expected. It provides direction, although it can lead to simply confirming what was anticipated, rather than documenting what transpired in the case.

Whichever approach you choose to frame the case, it is useful to think about the rationale or theory for each question and what methods would best enable you to gain an understanding of them. This will not only start a reflexive process of examining your choices—an important aspect of the process of data gathering and interpretation—it will also aid analysis and interpretation further down the track.

Methodology and Methods

Qualitative case study research, as already noted, appeals to subjective ways of knowing and to a primarily qualitative methodology, that captures experiential understanding ( Stake, 2010 , pp. 56–70). It follows that the main methods of data gathering to access this way of knowing will be qualitative. Interviewing, observation, and document analysis are the primary three, often supported by critical incidents, focus groups, cameos, vignettes, diaries/journals, and photographs. Before gathering any primary data, however, it is useful to search relevant existing sources (written or visual) to learn about the antecedents and context of a project, program, or policy as a backdrop to the case. This can sharpen framing questions, avoid unnecessary data gathering, and shorten the time needed in the field.

Given that there are excellent texts on qualitative methods (see, for example, Denzin & Lincoln, 1994 ; Seale, 1999 ; Silverman, 2000 , 2004 ), I will not discuss all potential relevant methods here, but simply focus on the qualities of the primary methods that are particularly appropriate for case study research.

Primary Qualitative Data Gathering Methods

Interviewing.

The most effective style of interviewing in qualitative case study research to gain in-depth data, document multiple perspectives and experiences and explore contested issues is the unstructured interview, active listening and open questioning are paramount, whatever prequestions or foreshadowed issues have been identified. This can include photographs—a useful starting point with certain cultural groups and the less articulate, to encourage them to tell their story through connecting or identifying with something in the image.

The flexibility of unstructured interviewing has three further advantages for understanding participants’ experiences. First, through questioning, probing, listening, and, above all, paying attention to the silences and what they mean, you can get closer to the meaning of participants’ experiences. It is not always what they say.

Second, unstructured interviewing is useful for engaging participants in the process of research. Instead of starting with questions and issues, invite participants to tell their stories or reflect on specific issues, to conduct their own self-evaluative interview, in fact. Not only will they contribute their particular perspective to the case, they will also learn about themselves, thereby making the process of research educative for them as well as for the audiences of the research.

Third, the open-endedness of this style of interviewing has the potential for creating a dialogue between participants and the researcher and between the researcher and the public, if enough of the dialogue is retained in the publication ( Bellah, Madsen, Sullivan, Swidler, & Tipton, 1985 ).

Observations

Observations in case study research are likely to be close-up descriptions of events, activities, and incidents that detail what happens in a particular context. They will record time, place, specific incidents, transactions, and dialogue, and note characteristics of the setting and of people in it without preconceived categories or judgment. No description is devoid of some judgment in selection, of course, but, on the whole, the intent is to describe the scene or event “as it is,” providing a rich, textured description to give readers a sense of what it was like to be there or provide a basis for later interpretation.

Take the following excerpt from a study of the West Bromwich Operatic Society. It is the first night of a new production, The Producers , by this amateur operatic society. This brief excerpt is from a much longer observation of the overture to the first evening’s performance, detailing exactly what the production is, where it is, and why there is such a tremendous sense of atmosphere and expectation surrounding the event. Space prevents including the whole observation, but I hope you can get a glimmer of the passion and excitement that precedes the performance:

Birmingham, late November, 2011, early evening.... Bars and restaurants spruce up for the evening’s trade. There is a chill in the air but the party season is just starting....

A few hundred yards away, past streaming traffic on Suffolk Street, Queensway, an audience is gathering at the New Alexandra Theatre. The foyer windows shine in the orange sodium night. Above each one is the rubric: WORLD CLASS THEATRE.

Inside the preparatory rituals are being observed; sweets chosen, interval drinks ordered and programmes bought. People swap news and titbits about the production.... The bubble of anticipation grows as the 5-minute warning sounds. People make their way to the auditorium. There have been so many nights like this in the past 110 years since a man named William Coutts invested £10,000 to build this palace of dreams.... So many fantasies have been played under this arch: melodramas and pantomimes, musicals and variety.... So many audiences, settling down in their tip-up seats, wanting to be transported away from work, from ordinariness and private troubles.... The dimming lights act like a mother’s hush. You could touch the silence. Boinnng! A spongy thump on a bass drum, and the horns pipe up that catchy, irrepressible, tasteless tune and already you’re singing under your breath, ‘Springtime for Hitler and Germany....’ The orchestra is out of sight in the pit. There’s just the velvet curtain to watch as your fingers tap along. What’s waiting behind? Then it starts it to move. Opening night.... It’s opening night! ( Matarasso, 2012 , pp. 1–2)

For another and different example—a narrative observation of an everyday but unique incident that details date, time, place, and experience—see Simons (2009 , p. 60).

Such naturalistic observations are also useful in contexts where we cannot understand what is going on through interviewing alone—in cultures with which we are less familiar or where key actors may not share our language or have difficulty expressing it. Careful description in these situations can help identify key issues, discover the norms and values that exist in the culture, and, if sufficiently detailed, allow others to cross corroborate what significance we draw from these observations. This last point is very important to avoid the danger in observation of ascribing motivations to people and meanings to transactions.

Finally, naturalistic observations are very important in highly politicized environments, often the case in commissioned evaluation case study, where individuals in interview may try to elude the “truth” or press on you that their view is the “right” view of the situation. In these contexts, naturalistic observations not only enable you to document interactions as you perceive them, but they also provide a cross-check on the veracity of information obtained in interviews.

Document analysis

Analysis of documents, as already intimated, is useful for establishing what historical antecedents might exist to provide a springboard for contemporaneous data gathering. In most cases, existing documents are also extremely pertinent for understanding the policy context.

In a national policy case study I conducted on a major curriculum change, the importance of preexisting documentation was brought home to me sharply when certain documentation initially proved elusive to obtain. It was difficult to believe that it did not exist, as the evolution of the innovation involved several parties who had not worked together before. There was bound, I thought, to be minuted meetings sharing progress and documentation of the “new” curriculum. In the absence of some crucial documents, I began to piece together the story through interviewing. Only there were gaps, and certain issues did not make sense.

It was only when I presented two versions of what I discerned had transpired in the development of this initiative in an interim report eighteen months into the study that things started to change. Subsequent to the meeting at which the report was presented, the “missing” documents started to appear. Suddenly found. What lay behind the “missing documents,” something I suspected from what certain individuals did and did not say in interview, was a major difference of view about how the innovation evolved, who was key in the process, and whose voice was more important in the context. Political differences, in other words, that some stakeholders were trying to keep from me. The emergence of the documents enabled me to finally produce an accurate and fair account.

This is an example of the importance of having access to all relevant documents relating to a program or policy in order to study it fairly. The other major way in which document analysis is useful in case study is for understanding the values, explicit and hidden, in policy and program documents and in the organization where the program or policy is implemented. Not to be ignored as documents are photographs, and these, too, can form the basis of a cultural and value analysis of an organization ( Prosser, 2000 ).

Creative artistic approaches

Increasingly, some case study researchers are employing creative approaches associated with the arts as a means of data gathering and analysis. Artistic approaches have often been used in representing findings, but less frequently in data gathering and interpretation ( Simons & McCormack, 2007 ). A major exception is the work of Richardson (1994) , who sees the very process of writing as an interpretative act, and of Cancienne and Snowber (2003) , who argue for movement as method.

The most familiar of these creative and artistic forms are written—narratives and short stories ( Clandinin & Connelly, 2000 ; Richardson, 1994 ; Sparkes, 2002 ), poems or poetic form ( Butler-Kisber, 2010 ; Duke, 2007 ; Richardson, 1997 ; Sparkes & Douglas, 2007 ), cameos of people, or vignettes of situations. These can be written by participants or by the researcher or developed in partnership. They can also be shared with participants to further interpret the data. But photographs also have a long history in qualitative research for presenting and constructing understanding ( Butler-Kisber, 2010 ; Collier, 1967 ; Prosser, 2000 ; Rugang, 2006 ; Walker, 1993 ).

Less common are other visual forms of gathering data, such as “draw and write” ( Sewell, 2011 ), artefacts, drawings, sketches, paintings, and collages, although all forms are now on the increase. For examples of the use of collage in data gathering, see Duke (2007) and Butler-Kisber (2010) , and for charcoal drawing, Elliott (2008) .