Type 2 Diabetes Research At-a-Glance

The ADA is committed to continuing progress in the fight against type 2 diabetes by funding research, including support for potential new treatments, a better understating of genetic factors, addressing disparities, and more. For specific examples of projects currently funded by the ADA, see below.

Greg J. Morton, PhD

University of Washington

Project: Neurocircuits regulating glucose homeostasis

“The health consequences of diabetes can be devastating, and new treatments and therapies are needed. My research career has focused on understanding how blood sugar levels are regulated and what contributes to the development of diabetes. This research will provide insights into the role of the brain in the control of blood sugar levels and has potential to facilitate the development of novel approaches to diabetes treatment.”

The problem: Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is among the most pressing and costly medical challenges confronting modern society. Even with currently available therapies, the control and management of blood sugar levels remains a challenge in T2D patients and can thereby increase the risk of diabetes-related complications. Continued progress with newer, better therapies is needed to help people with T2D.

The project: Humans have special cells, called brown fat cells, which generate heat to maintain optimal body temperature. Dr. Morton has found that these cells use large amounts of glucose to drive this heat production, thus serving as a potential way to lower blood sugar, a key goal for any diabetes treatment. Dr. Morton is working to understand what role the brain plays in turning these brown fat cells on and off.

The potential outcome: This work has the potential to fundamentally advance our understanding of how the brain regulates blood sugar levels and to identify novel targets for the treatment of T2D.

Tracey Lynn McLaughlin, MD

Stanford University

Project: Role of altered nutrient transit and incretin hormones in glucose lowering after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery

“This award is very important to me personally not only because the enteroinsular axis (gut-insulin-glucose metabolism) is a new kid on the block that requires rigorous physiologic studies in humans to better understand how it contributes to glucose metabolism, but also because the subjects who develop severe hypoglycemia after gastric bypass are largely ignored in society and there is no treatment for this devastating and very dangerous condition.”

The problem: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery is the single-most effective treatment for type 2 diabetes, with persistent remission in 85% of cases. However, the underlying ways by which the surgery improves glucose control is not yet understood, limiting the ability to potentially mimic the surgery in a non-invasive way. Furthermore, a minority of RYGB patients develop severe, disabling, and life-threatening low-blood sugar, for which there is no current treatment.

The project: Utilizing a unique and rigorous human experimental model, the proposed research will attempt to gain a better understanding on how RYGB surgery improves glucose control. Dr. McLaughlin will also test a hypothesis which she believes could play an important role in the persistent low-blood sugar that is observed in some patients post-surgery.

The potential outcome: This research has the potential to identify novel molecules that could represent targets for new antidiabetic therapies. It is also an important step to identifying people at risk for low-blood sugar following RYGB and to develop postsurgical treatment strategies.

Rebekah J. Walker, PhD

Medical College of Wisconsin

Project: Lowering the impact of food insecurity in African Americans with type 2 diabetes

“I became interested in diabetes research during my doctoral training, and since that time have become passionate about addressing social determinants of health and health disparities, specifically in individuals with diabetes. Living in one of the most racially segregated cities in the nation, the burden to address the needs of individuals at particularly high risk of poor outcomes has become important to me both personally and professionally.”

The problem: Food insecurity is defined as the inability to or limitation in accessing nutritionally adequate food and may be one way to address increased diabetes risk in high-risk populations. Food insecure individuals with diabetes have worse diabetes outcomes and have more difficulty following a healthy diet compared to those who are not food insecure.

The project: Dr. Walker’s study will gather information to improve and then will test an intervention to improve blood sugar control, dietary intake, self-care management, and quality of life in food insecure African Americans with diabetes. The intervention will include weekly culturally appropriate food boxes mailed to the participants and telephone-delivered diabetes education and skills training. It will be one of the first studies focused on the unique needs of food insecure African American populations with diabetes using culturally tailored strategies.

The potential outcome: This study has the potential to guide and improve policies impacting low-income minorities with diabetes. In addition, Dr. Walker’s study will help determine if food supplementation is important in improving diabetes outcomes beyond diabetes education alone.

Research Summaries

Keep up with the latest diabetes and diabetes-related studies with these brief overviews. Each summary provides main points, methods, and findings and includes a link to the article.

Diabetes Management and Education

Reaching treatment goals could help people living with type 2 diabetes increase their life expectancy by 3 years or in some cases by as much as 10 years. Read the summary .

Adults who receive diabetes education are more likely to follow recommended preventive care practices that lead to better diabetes management. Read the summary .

In 2017, the total cost of diabetes complications was over $37 billion among Medicare beneficiaries 65 or older with type 2 diabetes. Read the summary .

Kids and teens can get both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. New research shows how diabetes rates in young people may rise by 2060. Read the summary .

New USPSTF and ADA guidelines lower the age for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes screening to 35. This study examined if testing practices aligned with guidelines and which populations were less likely to receive testing. Read the summary .

The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study reports trends in young people who are being diagnosed with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Read the summary .

Recent guidelines recommend newer types of diabetes medications, and most Americans living with type 2 diabetes are eligible. Read the summary .

Chronic Kidney Disease

End-stage kidney disease—kidney failure that requires dialysis or a kidney transplant—can lead to disability and early death, is expensive to treat, and cases are on the rise. Read the summary .

- Reports and Publications

- Research Projects

- US Diabetes Surveillance System

To receive updates about diabetes topics, enter your email address:

- Diabetes Home

- State, Local, and National Partner Diabetes Programs

- National Diabetes Prevention Program

- Native Diabetes Wellness Program

- Chronic Kidney Disease

- Vision Health Initiative

- Heart Disease and Stroke

- Overweight & Obesity

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Clinical Trials

Type 2 diabetes.

Displaying 96 studies

The purpose of this study is to identify changes to the metabolome (range of chemicals produced in the body) and microbiome (intestine microbe environment) that are unique to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery and assess the associated effect on the metabolism of patients with type 2 diabetes.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the impact of a digital storytelling intervention derived through a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach on type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) outcomes among Hispanic adults with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) in primary care settings through a randomized clinical trial.

The purpose of this study is to assess the impact of a whole food plant-based diet on blood sugar control in diabetic patients versus a control group on the American Diabetics Association diet before having a total hip, knee, or shoulder replacement surgery.

The purpose of this study is to learn more about if the medication, Entresto, could help the function of the heart and kidneys.

The primary aim of this study is to compare the outcome measures of adult ECH type 2 diabetes patients who were referred to onsite pharmacist services for management of their diabetes to similar patients who were not referred for pharmacy service management of their diabetes. A secondary aim of the study is to assess the Kasson providers’ satisfaction level and estimated pharmacy service referral frequency to their patients. A tertiary aim of the study is to compare the hospitalization rates of type 2 diabetes rates who were referred to onsite pharmacist services for management of their diabetes to similar patients ...

To explore the feasibility of conducting a family centered wellness coaching program for patients at high risk for developing diabetes, in a primary care setting.

To determine engagement patterns.

To describe characteristics of families who are likely to participate.

To identify barriers/limitations to family centered wellness coaching.

To assess whether a family centered 8 week wellness coaching intervention for primary care patients at high risk for diabetes will improve self-care behaviors as measured by self-reported changes in physical activity level and food choices.

This study is being done to understand metformin's mechanisms of action regarding glucose production, protein metabolism, and mitochondrial function.

The purpose of this study is to assess the effectiveness of Revita® DMR for improving HbA1c to ≤ 7% without the need of insulin in subjects with T2D compared to sham and to assess the effectiveness of DMR versus Sham on improvement in Glycemic, Hepatic and Cardiovascular endpoints.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate 6 weeks of home use of the Control-IQ automated insulin delivery system in individuals with type 2 diabetes.

This study will evaluate whether bile acids are able to increase insulin sensitivity and enhance glycemic control in T2DM patients, as well as exploring the mechanisms that enhance glycemic control. These observations will provide the preliminary data for proposing future therapeutic as well as further mechanistic studies of the role of bile acids in the control of glycemia in T2DM.

The purpose of this study is to determine if Inpatient Stress Hyperglycemia is an indicator of future risk of developing type 2 Diabetes Mellitus.

The purpose of this study is to assess the effectiveness of a digital storytelling intervention derived through a community based participatory research (CBPR) approach on self-management of type 2 diabetes (T2D) among Somali adults.

The GRADE Study is a pragmatic, unmasked clinical trial that will compare commonly used diabetes medications, when combined with metformin, on glycemia-lowering effectiveness and patient-centered outcomes.

The overall goal of this proposal is to determine the effects of acute hyperglycemia and its modulation by Glucagon-like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) on myocardial perfusion in type 2 diabetes (DM). This study plan utilizes myocardial contrast echocardiography (MCE) to explore a) the effects of acute hyperglycemia on myocardial perfusion and coronary flow reserve in individuals with and without DM; and b) the effects of GLP-1 on myocardial perfusion and coronary flow reserve during euglycemia and hyperglycemia in DM. The investigators will recruit individuals with and without DM matched for age, gender and degree of obesity. The investigators will measure myocardial perfusion ...

The purpose of this study is to test the hypothesis that patients with T2DM will have greater deterioration in BMSi and in cortical porosity over 3 yrs as compared to sex- and age-matched non-diabetic controls; and identify the circulating hormonal (e.g., estradiol [E2], testosterone [T]) and biochemical (e.g., bone turnover markers, AGEs) determinants of changes in these key parameters of bone quality, and evaluate the possible relationship between existing diabetic complications and skeletal deterioration over time in the T2DM patients.

The purpose of this study is to determine the effect of endogenous GLP-1 secretion on islet function in people with Typr 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM).

GLP-1 is a hormone made by the body that promotes the production of insulin in response to eating. However, there is increasing evidence that this hormone might help support the body’s ability to produce insulin when diabetes develops.

The purpose of this study is to assess whether psyllium is more effective in lowering fasting blood sugar and HbA1c, and to evaluate the effect of psyllium compared to wheat dextrin on the following laboratory markers: LDL-C, inflammatory markers such as ceramides and hsCRP, and branch chain amino acids which predict Diabetes Mellitus (DM).

This mixed methods study aims to answer the question: "What is the work of being a patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus?" .

The purpose of this study is to assess penile length pre- and post-completion of RestoreX® traction therapy compared to control groups (no treatment) among men with type II diabetes.

This observational study is conducted to determine how the duodenal layer thicknesses (mucosa, submucosa, and muscularis) vary with several factors in patients with and without type 2 diabetes.

This trial is a multi-center, adaptive, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active- controlled, parallel group, phase 2 study in subjects with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus to evaluate the effect of TTP399 on HbA1c following administration for 6 months.

The purpose of this study is to find the inheritable changes in genetic makeup that are related to the development of type 2 diabetes in Latino families.

The objective of this early feasibility study is to assess the feasibility and preliminary safety of the Endogenex Divice for endoscopic duodenal mucosal regeneration in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) inadequately controlled on 2-3 non-insulin glucose-lowering medications.

The purpose of this study is to determine the impact of patient decision aids compared to usual care on measures of patient involvement in decision-making, diabetes care processes, medication adherence, glycemic and cardiovascular risk factor control, and use of resources in nonurban practices in the Midwestern United States.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate if breathing pure oxygen overnight affects insulin sensitivity in participants with diabetes.

The purpose of this study is to estimate the risk of diabetes related complications after total pancreatectomy. We will contact long term survivors after total pancreatectomy to obtain data regarding diabetes related end organ complications.

The purpose of this study is to understand nighttime glucose regulation in humans and find if the pattern is different in people with Type 2 diabetes

The study is being undertaken to understand how a gastric bypass can affect a subject's diabetes even prior to their losing significant amounts of weight. The hypothesis of this study is that increased glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) secretion explains the amelioration in insulin secretion after Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) surgery.

The investigators will determine whether people with high muscle mitochondrial capacity produce higher amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS) on consuming high fat /high glycemic diet and thus exhibit elevated cellular oxidative damage. The investigators previously found that Asian Indian immigrants have high mitochondrial capacity in spite of severe insulin resistance. Somalians are another new immigrant population with rapidly increasing prevalence of diabetes. Both of these groups traditionally consume low caloric density diets, and the investigators hypothesize that when these groups are exposed to high-calorie Western diets, they exhibit increased oxidative stress, oxidative damage, and insulin resistance. The investigators will ...

The purpose of this research is to find out how genetic variations in GLP1R, alters insulin secretion, in the fasting state and when blood sugars levels are elevated. Results from this study may help us identify therapies to prevent or reverse type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The study purpose is to understand patients’ with the diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus type 1 or 2 perception of the care they receive in the Diabetes clinic or Diabetes technology clinic at Mayo Clinic and to explore and to identify the healthcare system components patients consider important to be part of the comprehensive regenerative care in the clinical setting.

However, before we can implement structural changes or design interventions to promote comprehensive regenerative care in clinical practice, we first need to characterize those regenerative practices occurring today, patients expectations, perceptions and experiences about comprehensive regenerative care and determine the ...

It is unknown how patient preferences and values impact the comparative effectiveness of second-line medications for Type 2 diabetes (T2D). The purpose of this study is to elicit patient preferences toward various treatment outcomes (e.g., hospitalization, kidney disease) using a participatory ranking exercise, use these rankings to generate individually weighted composite outcomes, and estimate patient-centered treatment effects of four different second-line T2D medications that reflect the patient's value for each outcome.

The purpose of this mixed-methods study is to deploy the tenets of Health and Wellness Coaching (HWC) through a program called BeWell360 model , tailored to the needs of Healthcare Workers (HCWs) as patients living with poorly-controlled Type 2 Diabetes (T2D). The objective of this study is to pilot-test this novel, scalable, and sustainable BeWell360 model that is embedded and integrated as part of primary care for Mayo Clinic Employees within Mayo Clinic Florida who are identified as patients li)ving with poorly-controlled T2D.

To determine if the EndoBarrier safely and effectively improves glycemic control in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes.

Can QBSAfe be implemented in a clinical practice setting and improve quality of life, reduce treatment burden and hypoglycemia among older, complex patients with type 2 diabetes?

Questionnaire administered to diabetic patients in primary care practice (La Crosse Mayo Family Medicine Residency /Family Health Clinic) to assess patient’s diabetic knowledge. Retrospective chart review will also be done to assess objective diabetic control based on most recent hemoglobin A1c.

The purpose of this study is to assess key characteristics of bone quality, specifically material strength and porosity, in patients who have type 2 diabetes. These patients are at an unexplained increased risk for fractures and there is an urgent need to refine clinical assessment for this risk.

Muscle insulin resistance is a hallmark of upper body obesity (UBO) and Type 2 diabetes (T2DM). It is unknown whether muscle free fatty acid (FFA) availability or intramyocellular fatty acid trafficking is responsible for muscle insulin resistance, although it has been shown that raising FFA with Intralipid can cause muscle insulin resistance within 4 hours. We do not understand to what extent the incorporation of FFA into ceramides or diacylglycerols (DG) affect insulin signaling and muscle glucose uptake. We propose to alter the profile and concentrations of FFA of healthy, non-obese adults using an overnight, intra-duodenal palm oil infusion vs. ...

The objectives of this study are to identify circulating extracellular vesicle (EV)-derived protein and RNA signatures associated with Type 2 Diabetes (T2D), and to identify changes in circulating EV cargo in patients whose T2D resolves after sleeve gastrectomy (SG) or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB).

This research study is being done to develop educational materials that will help patients and clinicians talk about diabetes treatment and management options.

Assessment of glucose metabolism and liver fat after 12 week dietary intervention in pre diabetes subjects. Subjects will be randomized to either high fat (olive oil supplemented),high carb/high fiber (beans supplemented) and high carb/low fiber diets. Glucose metabolism will be assessed by labeled oral glucose tolerance test and liver fat by magnetic resonance spectroscopy pre randomization and at 8 and 12 week after starting dietary intervention.

To study the effect of an ileocolonic formulation of ox bile extract on insulin sensitivity, postprandial glycemia and incretin levels, gastric emptying, body weight and fasting serum FGF-19 (fibroblast growth factor) levels in overweight or obese type 2 diabetic subjects on therapy with DPP4 (dipeptidyl peptidase-4) inhibitors (e.g. sitagliptin) alone or in combination with metformin.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate whether or not a 6 month supply (1 meal//day) of healthy food choices readily available in the patient's home and self management training including understanding of how foods impact diabetes, improved food choices and how to prepare those foods, improve glucose control. In addition, it will evaluate whether or not there will be lasting behavior change modification after the program.

The purpose of this study is to compare the rate of progression from prediabetes at 4 months to frank diabetes at 12 months (as defined by increase in HbA1C or fasting BS to diabetic range based on the ADA criteria) after transplantation in kidney transplant recipients on Exenatide SR + SOC vs. standard-of-care alone.

The purpose of this study evaluates a subset of people with isolated Impaired Fasting Glucose with Normal Glucose Tolerance (i.e., IFG/NGT) believed to have normal β-cell function in response to a glucose challenge, suggesting that – at least in this subset of prediabetes – fasting glucose is regulated independently of glucose in the postprandial period. To some extent this is borne out by genetic association studies which have identified loci that affect fasting glucose but not glucose tolerance and vice-versa.

The purpose of this study is to learn more about how the body stores dietary fat. Medical research has shown that fat stored in different parts of the body can affect the risk for diabetes, heart disease and other major health conditions.

The purpose of this study is to see why the ability of fat cells to respond to insulin is different depending on body shape and how fat tissue inflammation is involved.

The purpose of this study is to determine the mechanism(s) by which common bariatric surgical procedures alter carbohydrate metabolism. Understanding these mechanisms may ultimately lead to the development of new interventions for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes and obesity.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effects of improving glycemic control, and/or reducing glycemic variability on gastric emptying, intestinal barrier function, autonomic nerve functions, and epigenetic changes in subjects with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) who are switched to intensive insulin therapy as part of clinical practice.

This study is designed to compare an intensive lifestyle and activity coaching program ("Sessions") to usual care for diabetic patients who are sedentary. The question to be answered is whether the Sessions program improves clinical or patient centric outcomes. Recruitment is through invitiation only.

A research study to enhance clinical discussion between patients and pharmacists using a shared decision making tool for type 2 diabetes or usual care.

While the potential clinical uses of pulsed electromagnetic field therapy (PEMF) are extensive, we are focusing on the potential benefits of PEMF on vascular health. We are targeting, the pre diabetic - metabolic syndrome population, a group with high prevalence in the American population. This population tends to be overweight, low fitness, high blood pressure, high triglycerides and borderline high blood glucose.

This is a study to evaluate a new Point of Care test for blood glucose monitoring.

This protocol is being conducted to determine the mechanisms responsible for insulin resistance, obesity and type 2 diabetes.

The purpose of this study is to assess the effects of a nighttime rise in cortisol on the body's glucose production in type 2 diabetes.

The goal of this study is to evaluate a new format for delivery of a culturally tailored digital storytelling intervention by incorporating a facilitated group discussion following the videos, for management of type II diabetes in Latino communities.

The purpose of this study is to determine the metabolic effects of Colesevelam, particularly for the ability to lower blood sugar after a meal in type 2 diabetics, in order to develop a better understanding of it's potential role in the treatment of obesity.

The purpose of this study is to test whether markers of cellular aging and the SASP are elevated in subjects with obesity and further increased in patients with obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) and to relate markers of cellular aging (senescence) and the SASP to skeletal parameters (DXA, HRpQCT, bone turnover markers) in each of these groups.

Integration of Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) and Diabetes Self Management Program (DSMP) into WellConnect.

Using stem cell derived intestinal epithelial cultures (enteroids) derived from obese (BMI> 30) patients and non-obese and metabolically normal patients (either post-bariatric surgery (BS) or BS-naïve with BMI < 25), dietary glucose absorption was measured. We identified that enteroids from obese patients were characterized by glucose hyper-absorption (~ 5 fold) compared to non-obese patients. Significant upregulation of major intestinal sugar transporters, including SGLT1, GLU2 and GLUT5 was responsible for hyper-absorptive phenotype and their pharmacologic inhibition significantly decreased glucose absorption. Importantly, we observed that enteroids from post-BS non-obese patients exhibited low dietary glucose absorption, indicating that altered glucose absorption ...

Muscle insulin resistance is a hallmark of upper body obesity (UBO) and Type 2 diabetes (T2DM). It is unknown whether muscle free fatty acid (FFA) availability or intramyocellular fatty acid trafficking is responsible for the abnormal response to insulin. Likewise, we do not understand to what extent the incorporation of FFA into ceramides or diacylglycerols (DG) affect insulin signaling and muscle glucose uptake. We will measure muscle FFA storage into intramyocellular triglyceride, intramyocellular fatty acid trafficking, activation of the insulin signaling pathway and glucose disposal rates under both saline control (high overnight FFA) and after an overnight infusion of intravenous ...

The purpose of this study is to improve our understanding of why gastrointestinal symptoms occur in diabetes mellitus patients and identify new treatment(s) in the future.

These symptoms are often distressing and may impair glycemic control. We do not understand how diabetes mellitus affects the GI tracy. In 45 patients undergoing sleeve gastrectomy, we plan to compare the cellular composition of circulating peripheral mononuclear cells, stomach immune cells, and interstitial cells of Cajal in the stomach.

Muscle insulin resistance is a hallmark of upper body obesity (UBO) and Type 2 diabetes (T2DM), whereas lower body obesity (LBO) is characterized by near-normal insulin sensitivity. It is unknown whether muscle free fatty acid (FFA) availability or intramyocellular fatty acid trafficking differs between different obesity phenotypes. Likewise, we do not understand to what extent the incorporation of FFA into ceramides or diacylglycerols (DG) affect insulin signaling and muscle glucose uptake. By measuring muscle FFA storage into intramyocellular triglyceride, intramyocellular fatty acid trafficking, activation of the insulin signaling pathway and glucose disposal rates we will provide the first integrated examination ...

The goal of this study is to evaluate the presence of podocytes (special cells in the kidney that prevent protein loss) in the urine in patients with diabetes or glomerulonephritis (inflammation in the kidneys). Loss of podocyte in the urine may be an earlier sign of kidney injury (before protein loss) and the goal of this study is to evaluate the association between protein in the urine and podocytes in the urine.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effects of multiple dose regimens of RM-131 on vomiting episodes, stomach emptying and stomach paralysis symptoms in patients with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes and gastroparesis.

The purpose of this study is assess the feasibility, effectiveness, and acceptability of Diabetes-REM (Rescue, Engagement, and Management), a comprehensive community paramedic (CP) program to improve diabetes self-management among adults in Southeast Minnesota (SEMN) treated for servere hypoglycemia by the Mayo Clinic Ambulance Services (MCAS).

The purpose of this study is to determine if a blood test called "pancreatic polypeptide" can help distinguish between patients with diabetes mellitus with and without pancreatic cancer.

The purpose of this study is to create a prospective cohort of subjects with increased probability of being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and then screen this cohort for pancreatic cancer

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of brolucizumab vs. aflibercept in the treatment of patients with visual impairment due to diabetic macular edema (DME).

Women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) are likely to have insulin resistance that persists long after pregnancy, resulting in greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). The study will compare women with and without a previous diagnosis of GDM to determine if women with a history of GDM have abnormal fatty acid metabolism, specifically impaired adipose tissue lipolysis. The study will aim to determine whether women with a history of GDM have impaired pancreatic β-cell function. The study will determine whether women with a history of GDM have tissue specific defects in insulin action, and also identify the effect of a ...

Although vitreous hemorrhage (VH) from proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) can cause acute and dramatic vision loss for patients with diabetes, there is no current, evidence-based clinical guidance as to what treatment method is most likely to provide the best visual outcomes once intervention is desired. Intravitreous anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) therapy alone or vitrectomy combined with intraoperative PRP each provide the opportunity to stabilize or regress retinal neovascularization. However, clinical trials are lacking to elucidate the relative time frame of visual recovery or final visual outcome in prompt vitrectomy compared with initial anti-VEGF treatment. The Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research ...

The purpose of this study is to demonstrate feasibility of dynamic 11C-ER176 PET imaging to identify macrophage-driven immune dysregulation in gastric muscle of patients with DG. Non-invasive quantitative assessment with PET can significantly add to our diagnostic armamentarium for patients with diabetic gastroenteropathy.

The purpose of this study is to assess the safety and tolerability of intra-arterially delivered mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSC) to a single kidney in one of two fixed doses at two time points in patients with progressive diabetic kidney disease.

Diabetic kidney disease, also known as diabetic nephropathy, is the most common cause of chronic kidney disease and end-stage kidney failure requiring dialysis or kidney transplantation. Regenerative, cell-based therapy applying MSCs holds promise to delay the progression of kidney disease in individuals with diabetes mellitus. Our clinical trial will use MSCs processed from each study participant to test the ...

This study aims to measure the percentage of time spent in hyperglycemia in patients on insulin therapy and evaluate diabetes related patient reported outcomes in kidney transplant recipients with type 2 diabetes. It also aimes to evaluate immunosuppression related patient reported outcomes in kidney transplant recipients with type 2 diabetes.

The purpose of this study is to look at how participants' daily life is affected by their heart failure. The study will also look at the change in participants' body weight. This study will compare the effect of semaglutide (a new medicine) compared to "dummy" medicine on body weight and heart failure symptoms. Participants will either get semaglutide or "dummy" medicine, which treatment participants get is decided by chance. Participants will need to take 1 injection once a week.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate whether or not semaglutide can slow down the growth and worsening of chronic kidney disease in people with type 2 diabetes. Participants will receive semaglutide (active medicine) or placebo ('dummy medicine'). This is known as participants' study medicine - which treatment participants get is decided by chance. Semaglutide is a medicine, doctors can prescribe in some countries for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Participants will get the study medicine in a pen. Participants will use the pen to inject the medicine in a skin fold once a week. The study will close when ...

The objectives of this study are to evaluate the safety of IW-9179 in patients with diabetic gastroparesis (DGP) and the effect of treatment on the cardinal symptoms of DGP.

The purpose of this study is to understand why patients with indigestion, with or without diabetes, have gastrointestinal symptoms and, in particular, to understand where the symptoms are related to increased sensitivity to nutrients.Subsequently, look at the effects of Ondansetron on these patients' symptoms.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and exploratory effectiveness of nimacimab in patients with diabetic gastroparesis.

The purpose of this study is to prospectively assemble a cohort of subjects >50 and ≤85 years of age with New-onset Diabetes (NOD):

- Estimate the probability of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) in the NOD Cohort;

- Establish a biobank of clinically annotated biospecimens including a reference set of biospecimens from pre-symptomatic PDAC and control new-onset type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) subjects;

- Facilitate validation of emerging tests for identifying NOD subjects at high risk for having PDAC using the reference set; and

- Provide a platform for development of an interventional protocol for early detection of sporadic PDAC ...

The purpose of this study is to demonstrate the performance of the Guardian™ Sensor (3) with an advanced algorithm in subjects age 2 - 80 years, for the span of 170 hours (7 days).

The purpose of this study is to look at the relationship of patient-centered education, the Electronic Medical Record (patient portal) and the use of digital photography to improve the practice of routine foot care and reduce the number of foot ulcers/wounds in patients with diabetes.

Diabetes mellitus is a common condition which is defined by persistently high blood sugar levels. This is a frequent problem that is most commonly due to type 2 diabetes. However, it is now recognized that a small portion of the population with diabetes have an underlying problem with their pancreas, such as chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer, as the cause of their diabetes. Currently, there is no test to identify the small number of patients who have diabetes caused by a primary problem with their pancreas.

The goal of this study is to develop a test to distinguish these ...

The primary purpose of this study is to evaluate the impact of dapagliflozin, as compared with placebo, on heart failure, disease specific biomarkers, symptoms, health status and quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes or prediabetes and chronic heart failure with preserved systolic function.

The primary purpose of this study is to prospectively assess symptoms of bloating (severity, prevalence) in patients with diabetic gastroparesis.

The purpose of this study is to track the treatment burden experienced by patients living with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) experience as they work to manage their illness in the context of social distancing measures.

To promote social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic, health care institutions around the world have rapidly expanded their use of telemedicine to replace in-office appointments where possible.1 For patients with diabetes, who spend considerable time and energy engaging with various components of the health care system,2,3 this unexpected and abrupt transition to virtual health care may signal significant changes to ...

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the safety and efficacy of oral Pyridorin 300 mg BID in reducing the rate of progression of nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effect of Aramchol as compared to placebo on NASH resolution, fibrosis improvement and clinical outcomes related to progression of liver disease (fibrosis stages 2-3 who are overweight or obese and have prediabetes or type 2 diabetes).

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the ability of appropriately-trained family physicians to screen for and identify Diabetic Retinopathy using retinal camera and, secondarily, to describe patients’ perception of the convenience and cost-effectiveness of retinal imaging.

The primary purpose of this study is to evaluate the impact of dapagliflozin, as compared with placebo, on heart failure disease-specific biomarkers, symptoms, health status, and quality of life in patients who have type 2 diabetes and chronic heart failure with reduced systolic function.

Hypothesis: We hypothesize that patients from the Family Medicine Department at Mayo Clinic Florida who participate in RPM will have significantly reduced emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and hospital contacts.

Aims, purpose, or objectives: In this study, we will compare the RPM group to a control group that does not receive RPM. The primary objective is to determine if there are significant group differences in emergency room visits, hospitalizations, outpatient primary care visits, outpatient specialty care visits, and hospital contacts (inbound patient portal messages and phone calls). The secondary objective is to determine if there are ...

The purpose of this research is to determine if CGM (continuous glucose monitors) used in the hospital in patients with COVID-19 and diabetes treated with insulin will be as accurate as POC (point of care) glucose monitors. Also if found to be accurate, CGM reading data will be used together with POC glucometers to dose insulin therapy.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effect of fenofibrate compared with placebo for prevention of diabetic retinopathy (DR) worsening or center-involved diabetic macular edema (CI-DME) with vision loss through 4 years of follow-up in participants with mild to moderately severe non-proliferative DR (NPDR) and no CI-DME at baseline.

The purpose of this study is to assess painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy after high-frequency spinal cord stimulation.

The purpose of this study is to examine the evolution of diabetic kindey injury over an extended period in a group of subjects who previously completed a clinical trial which assessed the ability of losartan to protect the kidney from injury in early diabetic kidney disease. We will also explore the relationship between diabetic kidney disease and other diabetes complications, including neuropathy and retinopathy.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effietiveness of remdesivir (RDV) in reducing the rate of of all-cause medically attended visits (MAVs; medical visits attended in person by the participant and a health care professional) or death in non-hospitalized participants with early stage coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and to evaluate the safety of RDV administered in an outpatient setting.

Mayo Clinic Footer

- Request Appointment

- About Mayo Clinic

- About This Site

Legal Conditions and Terms

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Notice of Privacy Practices

- Notice of Nondiscrimination

- Manage Cookies

Advertising

Mayo Clinic is a nonprofit organization and proceeds from Web advertising help support our mission. Mayo Clinic does not endorse any of the third party products and services advertised.

- Advertising and sponsorship policy

- Advertising and sponsorship opportunities

Reprint Permissions

A single copy of these materials may be reprinted for noncommercial personal use only. "Mayo," "Mayo Clinic," "MayoClinic.org," "Mayo Clinic Healthy Living," and the triple-shield Mayo Clinic logo are trademarks of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.

Patient Centered Studies Focused on Type 2 Diabetes Management, Education, and Family Support: A Scoping Review

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Pharmacy Administration, School of Pharmacy, University of Mississippi, Oxford, MS 38677-1848, USA.

- 2 School of Pharmacy, University of Mississippi, Oxford, MS 38677-1848, USA.

- PMID: 34789134

- DOI: 10.2174/1573399818666211117113026

Background: Although a large amount of research has been conducted in diabetes management, many of the articles do not focus on patient-centered questions and concerns. To address this shortcoming, patients and various other stakeholders from three northern Mississippi communities co-created research questions focused on Type 2 diabetes management.

Objective: To identify the diabetes management literature pertaining to each of the six patient-developed research questions from March 2010 to July 2020.

Methods: A scoping review was conducted via PubMed to identify research articles from March 2010 to July 2020 focused on patient-centered Type 2 diabetes studies relevant to the six research questions.

Results: A total of 1,414 studies were identified via the search strategy and 34 were included for qualitative analysis following article exclusion. For one of the research questions, there were no articles included. For the remaining research questions, the number of articles identified ranged from two to eleven. After analysis of the included articles, it was found that these questions either lacked extensive data or had not been implemented in the practice of diabetes management.

Conclusion: Additional research is warranted for three of the five questions, as current evidence is either lacking or contradictory. In the remaining two questions, it seems that adequate current research exists to warrant transitioning to implementation focused studies wherein data may be generated to improve sustainability and scaling of current programming.

Keywords: IDF; diabetes self-management; insulin; oral medications; patient-centered studies; type 2 diabetes.

Copyright© Bentham Science Publishers; For any queries, please email at [email protected].

Publication types

- Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2* / therapy

- Patient-Centered Care

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Type 2 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes is usually diagnosed using the glycated hemoglobin (A1C) test. This blood test indicates your average blood sugar level for the past two to three months. Results are interpreted as follows:

- Below 5.7% is normal.

- 5.7% to 6.4% is diagnosed as prediabetes.

- 6.5% or higher on two separate tests indicates diabetes.

If the A1C test isn't available, or if you have certain conditions that interfere with an A1C test, your health care provider may use the following tests to diagnose diabetes:

Random blood sugar test. Blood sugar values are expressed in milligrams of sugar per deciliter ( mg/dL ) or millimoles of sugar per liter ( mmol/L ) of blood. Regardless of when you last ate, a level of 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L ) or higher suggests diabetes, especially if you also have symptoms of diabetes, such as frequent urination and extreme thirst.

Fasting blood sugar test. A blood sample is taken after you haven't eaten overnight. Results are interpreted as follows:

- Less than 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L ) is considered healthy.

- 100 to 125 mg/dL (5.6 to 6.9 mmol/L ) is diagnosed as prediabetes.

- 126 mg/dL (7 mmol/L ) or higher on two separate tests is diagnosed as diabetes.

Oral glucose tolerance test. This test is less commonly used than the others, except during pregnancy. You'll need to not eat for a certain amount of time and then drink a sugary liquid at your health care provider's office. Blood sugar levels then are tested periodically for two hours. Results are interpreted as follows:

- Less than 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L ) after two hours is considered healthy.

- 140 to 199 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L and 11.0 mmol/L ) is diagnosed as prediabetes.

- 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L ) or higher after two hours suggests diabetes.

Screening. The American Diabetes Association recommends routine screening with diagnostic tests for type 2 diabetes in all adults age 35 or older and in the following groups:

- People younger than 35 who are overweight or obese and have one or more risk factors associated with diabetes.

- Women who have had gestational diabetes.

- People who have been diagnosed with prediabetes.

- Children who are overweight or obese and who have a family history of type 2 diabetes or other risk factors.

After a diagnosis

If you're diagnosed with diabetes, your health care provider may do other tests to distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes because the two conditions often require different treatments.

Your health care provider will test A1C levels at least two times a year and when there are any changes in treatment. Target A1C goals vary depending on age and other factors. For most people, the American Diabetes Association recommends an A1C level below 7%.

You also receive tests to screen for complications of diabetes and other medical conditions.

More Information

- Glucose tolerance test

Management of type 2 diabetes includes:

- Healthy eating.

- Regular exercise.

- Weight loss.

- Possibly, diabetes medication or insulin therapy.

- Blood sugar monitoring.

These steps make it more likely that blood sugar will stay in a healthy range. And they may help to delay or prevent complications.

Healthy eating

There's no specific diabetes diet. However, it's important to center your diet around:

- A regular schedule for meals and healthy snacks.

- Smaller portion sizes.

- More high-fiber foods, such as fruits, nonstarchy vegetables and whole grains.

- Fewer refined grains, starchy vegetables and sweets.

- Modest servings of low-fat dairy, low-fat meats and fish.

- Healthy cooking oils, such as olive oil or canola oil.

- Fewer calories.

Your health care provider may recommend seeing a registered dietitian, who can help you:

- Identify healthy food choices.

- Plan well-balanced, nutritional meals.

- Develop new habits and address barriers to changing habits.

- Monitor carbohydrate intake to keep your blood sugar levels more stable.

Physical activity

Exercise is important for losing weight or maintaining a healthy weight. It also helps with managing blood sugar. Talk to your health care provider before starting or changing your exercise program to ensure that activities are safe for you.

- Aerobic exercise. Choose an aerobic exercise that you enjoy, such as walking, swimming, biking or running. Adults should aim for 30 minutes or more of moderate aerobic exercise on most days of the week, or at least 150 minutes a week.

- Resistance exercise. Resistance exercise increases your strength, balance and ability to perform activities of daily living more easily. Resistance training includes weightlifting, yoga and calisthenics. Adults living with type 2 diabetes should aim for 2 to 3 sessions of resistance exercise each week.

- Limit inactivity. Breaking up long periods of inactivity, such as sitting at the computer, can help control blood sugar levels. Take a few minutes to stand, walk around or do some light activity every 30 minutes.

Weight loss

Weight loss results in better control of blood sugar levels, cholesterol, triglycerides and blood pressure. If you're overweight, you may begin to see improvements in these factors after losing as little as 5% of your body weight. However, the more weight you lose, the greater the benefit to your health. In some cases, losing up to 15% of body weight may be recommended.

Your health care provider or dietitian can help you set appropriate weight-loss goals and encourage lifestyle changes to help you achieve them.

Monitoring your blood sugar

Your health care provider will advise you on how often to check your blood sugar level to make sure you remain within your target range. You may, for example, need to check it once a day and before or after exercise. If you take insulin, you may need to check your blood sugar multiple times a day.

Monitoring is usually done with a small, at-home device called a blood glucose meter, which measures the amount of sugar in a drop of blood. Keep a record of your measurements to share with your health care team.

Continuous glucose monitoring is an electronic system that records glucose levels every few minutes from a sensor placed under the skin. Information can be transmitted to a mobile device such as a phone, and the system can send alerts when levels are too high or too low.

Diabetes medications

If you can't maintain your target blood sugar level with diet and exercise, your health care provider may prescribe diabetes medications that help lower glucose levels, or your provider may suggest insulin therapy. Medicines for type 2 diabetes include the following.

Metformin (Fortamet, Glumetza, others) is generally the first medicine prescribed for type 2 diabetes. It works mainly by lowering glucose production in the liver and improving the body's sensitivity to insulin so it uses insulin more effectively.

Some people experience B-12 deficiency and may need to take supplements. Other possible side effects, which may improve over time, include:

- Abdominal pain.

Sulfonylureas help the body secrete more insulin. Examples include glyburide (DiaBeta, Glynase), glipizide (Glucotrol XL) and glimepiride (Amaryl). Possible side effects include:

- Low blood sugar.

- Weight gain.

Glinides stimulate the pancreas to secrete more insulin. They're faster acting than sulfonylureas. But their effect in the body is shorter. Examples include repaglinide and nateglinide. Possible side effects include:

Thiazolidinediones make the body's tissues more sensitive to insulin. An example of this medicine is pioglitazone (Actos). Possible side effects include:

- Risk of congestive heart failure.

- Risk of bladder cancer (pioglitazone).

- Risk of bone fractures.

DPP-4 inhibitors help reduce blood sugar levels but tend to have a very modest effect. Examples include sitagliptin (Januvia), saxagliptin (Onglyza) and linagliptin (Tradjenta). Possible side effects include:

- Risk of pancreatitis.

- Joint pain.

GLP-1 receptor agonists are injectable medications that slow digestion and help lower blood sugar levels. Their use is often associated with weight loss, and some may reduce the risk of heart attack and stroke. Examples include exenatide (Byetta, Bydureon Bcise), liraglutide (Saxenda, Victoza) and semaglutide (Rybelsus, Ozempic, Wegovy). Possible side effects include:

SGLT2 inhibitors affect the blood-filtering functions in the kidneys by blocking the return of glucose to the bloodstream. As a result, glucose is removed in the urine. These medicines may reduce the risk of heart attack and stroke in people with a high risk of those conditions. Examples include canagliflozin (Invokana), dapagliflozin (Farxiga) and empagliflozin (Jardiance). Possible side effects include:

- Vaginal yeast infections.

- Urinary tract infections.

- Low blood pressure.

- High cholesterol.

- Risk of gangrene.

- Risk of bone fractures (canagliflozin).

- Risk of amputation (canagliflozin).

Other medicines your health care provider might prescribe in addition to diabetes medications include blood pressure and cholesterol-lowering medicines, as well as low-dose aspirin, to help prevent heart and blood vessel disease.

Insulin therapy

Some people who have type 2 diabetes need insulin therapy. In the past, insulin therapy was used as a last resort, but today it may be prescribed sooner if blood sugar targets aren't met with lifestyle changes and other medicines.

Different types of insulin vary on how quickly they begin to work and how long they have an effect. Long-acting insulin, for example, is designed to work overnight or throughout the day to keep blood sugar levels stable. Short-acting insulin generally is used at mealtime.

Your health care provider will determine what type of insulin is right for you and when you should take it. Your insulin type, dosage and schedule may change depending on how stable your blood sugar levels are. Most types of insulin are taken by injection.

Side effects of insulin include the risk of low blood sugar — a condition called hypoglycemia — diabetic ketoacidosis and high triglycerides.

Weight-loss surgery

Weight-loss surgery changes the shape and function of the digestive system. This surgery may help you lose weight and manage type 2 diabetes and other conditions related to obesity. There are several surgical procedures. All of them help people lose weight by limiting how much food they can eat. Some procedures also limit the amount of nutrients the body can absorb.

Weight-loss surgery is only one part of an overall treatment plan. Treatment also includes diet and nutritional supplement guidelines, exercise and mental health care.

Generally, weight-loss surgery may be an option for adults living with type 2 diabetes who have a body mass index (BMI) of 35 or higher. BMI is a formula that uses weight and height to estimate body fat. Depending on the severity of diabetes or the presence of other medical conditions, surgery may be an option for someone with a BMI lower than 35.

Weight-loss surgery requires a lifelong commitment to lifestyle changes. Long-term side effects may include nutritional deficiencies and osteoporosis.

People living with type 2 diabetes often need to change their treatment plan during pregnancy and follow a diet that controls carbohydrates. Many people need insulin therapy during pregnancy. They also may need to stop other treatments, such as blood pressure medicines.

There is an increased risk during pregnancy of developing a condition that affects the eyes called diabetic retinopathy. In some cases, this condition may get worse during pregnancy. If you are pregnant, visit an ophthalmologist during each trimester of your pregnancy and one year after you give birth. Or as often as your health care provider suggests.

Signs of trouble

Regularly monitoring your blood sugar levels is important to avoid severe complications. Also, be aware of symptoms that may suggest irregular blood sugar levels and the need for immediate care:

High blood sugar. This condition also is called hyperglycemia. Eating certain foods or too much food, being sick, or not taking medications at the right time can cause high blood sugar. Symptoms include:

- Frequent urination.

- Increased thirst.

- Blurred vision.

Hyperglycemic hyperosmolar nonketotic syndrome (HHNS). This life-threatening condition includes a blood sugar reading higher than 600 mg/dL (33.3 mmol/L ). HHNS may be more likely if you have an infection, are not taking medicines as prescribed, or take certain steroids or drugs that cause frequent urination. Symptoms include:

- Extreme thirst.

- Drowsiness.

- Dark urine.

Diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetic ketoacidosis occurs when a lack of insulin results in the body breaking down fat for fuel rather than sugar. This results in a buildup of acids called ketones in the bloodstream. Triggers of diabetic ketoacidosis include certain illnesses, pregnancy, trauma and medicines — including the diabetes medicines called SGLT2 inhibitors.

The toxicity of the acids made by diabetic ketoacidosis can be life-threatening. In addition to the symptoms of hyperglycemia, such as frequent urination and increased thirst, ketoacidosis may cause:

- Shortness of breath.

- Fruity-smelling breath.

Low blood sugar. If your blood sugar level drops below your target range, it's known as low blood sugar. This condition also is called hypoglycemia. Your blood sugar level can drop for many reasons, including skipping a meal, unintentionally taking more medication than usual or being more physically active than usual. Symptoms include:

- Irritability.

- Heart palpitations.

- Slurred speech.

If you have symptoms of low blood sugar, drink or eat something that will quickly raise your blood sugar level. Examples include fruit juice, glucose tablets, hard candy or another source of sugar. Retest your blood in 15 minutes. If levels are not at your target, eat or drink another source of sugar. Eat a meal after your blood sugar level returns to normal.

If you lose consciousness, you need to be given an emergency injection of glucagon, a hormone that stimulates the release of sugar into the blood.

- Medications for type 2 diabetes

- GLP-1 agonists: Diabetes drugs and weight loss

- Bariatric surgery

- Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty

- Gastric bypass (Roux-en-Y)

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies testing new treatments, interventions and tests as a means to prevent, detect, treat or manage this condition.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Careful management of type 2 diabetes can reduce the risk of serious — even life-threatening — complications. Consider these tips:

- Commit to managing your diabetes. Learn all you can about type 2 diabetes. Make healthy eating and physical activity part of your daily routine.

- Work with your team. Establish a relationship with a certified diabetes education specialist, and ask your diabetes treatment team for help when you need it.

- Identify yourself. Wear a necklace or bracelet that says you are living with diabetes, especially if you take insulin or other blood sugar-lowering medicine.

- Schedule a yearly physical exam and regular eye exams. Your diabetes checkups aren't meant to replace regular physicals or routine eye exams.

- Keep your vaccinations up to date. High blood sugar can weaken your immune system. Get a flu shot every year. Your health care provider also may recommend the pneumonia vaccine. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also recommends the hepatitis B vaccination if you haven't previously received this vaccine and you're 19 to 59 years old. Talk to your health care provider about other vaccinations you may need.

- Take care of your teeth. Diabetes may leave you prone to more-serious gum infections. Brush and floss your teeth regularly and schedule recommended dental exams. Contact your dentist right away if your gums bleed or look red or swollen.

- Pay attention to your feet. Wash your feet daily in lukewarm water, dry them gently, especially between the toes, and moisturize them with lotion. Check your feet every day for blisters, cuts, sores, redness and swelling. Contact your health care provider if you have a sore or other foot problem that isn't healing.

- Keep your blood pressure and cholesterol under control. Eating healthy foods and exercising regularly can go a long way toward controlling high blood pressure and cholesterol. Take medication as prescribed.

- If you smoke or use other types of tobacco, ask your health care provider to help you quit. Smoking increases your risk of diabetes complications. Talk to your health care provider about ways to stop using tobacco.

- Use alcohol sparingly. Depending on the type of drink, alcohol may lower or raise blood sugar levels. If you choose to drink alcohol, only do so with a meal. The recommendation is no more than one drink daily for women and no more than two drinks daily for men. Check your blood sugar frequently after drinking alcohol.

- Make healthy sleep a priority. Many people with type 2 diabetes have sleep problems. And not getting enough sleep may make it harder to keep blood sugar levels in a healthy range. If you have trouble sleeping, talk to your health care provider about treatment options.

- Caffeine: Does it affect blood sugar?

Alternative medicine

Many alternative medicine treatments claim to help people living with diabetes. According to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, studies haven't provided enough evidence to recommend any alternative therapies for blood sugar management. Research has shown the following results about popular supplements for type 2 diabetes:

- Chromium supplements have been shown to have few or no benefits. Large doses can result in kidney damage, muscle problems and skin reactions.

- Magnesium supplements have shown benefits for blood sugar control in some but not all studies. Side effects include diarrhea and cramping. Very large doses — more than 5,000 mg a day — can be fatal.

- Cinnamon, in some studies, has lowered fasting glucose levels but not A1C levels. Therefore, there's no evidence of overall improved glucose management.

Talk to your health care provider before starting a dietary supplement or natural remedy. Do not replace your prescribed diabetes medicines with alternative medicines.

Coping and support

Type 2 diabetes is a serious disease, and following your diabetes treatment plan takes commitment. To effectively manage diabetes, you may need a good support network.

Anxiety and depression are common in people living with diabetes. Talking to a counselor or therapist may help you cope with the lifestyle changes and stress that come with a type 2 diabetes diagnosis.

Support groups can be good sources of diabetes education, emotional support and helpful information, such as how to find local resources or where to find carbohydrate counts for a favorite restaurant. If you're interested, your health care provider may be able to recommend a group in your area.

You can visit the American Diabetes Association website to check out local activities and support groups for people living with type 2 diabetes. The American Diabetes Association also offers online information and online forums where you can chat with others who are living with diabetes. You also can call the organization at 800-DIABETES ( 800-342-2383 ).

Preparing for your appointment

At your annual wellness visit, your health care provider can screen for diabetes and monitor and treat conditions that increase your risk of diabetes, such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol or a high BMI .

If you are seeing your health care provider because of symptoms that may be related to diabetes, you can prepare for your appointment by being ready to answer the following questions:

- When did your symptoms begin?

- Does anything improve the symptoms or worsen the symptoms?

- What medicines do you take regularly, including dietary supplements and herbal remedies?

- What are your typical daily meals? Do you eat between meals or before bedtime?

- How much alcohol do you drink?

- How much daily exercise do you get?

- Is there a history of diabetes in your family?

If you are diagnosed with diabetes, your health care provider may begin a treatment plan. Or you may be referred to a doctor who specializes in hormonal disorders, called an endocrinologist. Your care team also may include the following specialists:

- Certified diabetes education specialist.

- Foot doctor, also called a podiatrist.

- Doctor who specializes in eye care, called an ophthalmologist.

Talk to your health care provider about referrals to other specialists who may be providing care.

Questions for ongoing appointments

Before any appointment with a member of your treatment team, make sure you know whether there are any restrictions, such as not eating or drinking before taking a test. Questions that you should regularly talk about with your health care provider or other members of the team include:

- How often do I need to monitor my blood sugar, and what is my target range?

- What changes in my diet would help me better manage my blood sugar?

- What is the right dosage for prescribed medications?

- When do I take the medications? Do I take them with food?

- How does management of diabetes affect treatment for other conditions? How can I better coordinate treatments or care?

- When do I need to make a follow-up appointment?

- Under what conditions should I call you or seek emergency care?

- Are there brochures or online sources you recommend?

- Are there resources available if I'm having trouble paying for diabetes supplies?

What to expect from your doctor

Your health care provider is likely to ask you questions at your appointments. Those questions may include:

- Do you understand your treatment plan and feel confident you can follow it?

- How are you coping with diabetes?

- Have you had any low blood sugar?

- Do you know what to do if your blood sugar is too low or too high?

- What's a typical day's diet like?

- Are you exercising? If so, what type of exercise? How often?

- Do you sit for long periods of time?

- What challenges are you experiencing in managing your diabetes?

- Professional Practice Committee: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes — 2020. Diabetes Care. 2020; doi:10.2337/dc20-Sppc.

- Diabetes mellitus. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/endocrine-and-metabolic-disorders/diabetes-mellitus-and-disorders-of-carbohydrate-metabolism/diabetes-mellitus-dm. Accessed Dec. 7, 2020.

- Melmed S, et al. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 14th ed. Elsevier; 2020. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Dec. 3, 2020.

- Diabetes overview. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/all-content. Accessed Dec. 4, 2020.

- AskMayoExpert. Type 2 diabetes. Mayo Clinic; 2018.

- Feldman M, et al., eds. Surgical and endoscopic treatment of obesity. In: Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management. 11th ed. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Oct. 20, 2020.

- Hypersmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS). Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/endocrine-and-metabolic-disorders/diabetes-mellitus-and-disorders-of-carbohydrate-metabolism/hyperosmolar-hyperglycemic-state-hhs. Accessed Dec. 11, 2020.

- Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/endocrine-and-metabolic-disorders/diabetes-mellitus-and-disorders-of-carbohydrate-metabolism/diabetic-ketoacidosis-dka. Accessed Dec. 11, 2020.

- Hypoglycemia. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/endocrine-and-metabolic-disorders/diabetes-mellitus-and-disorders-of-carbohydrate-metabolism/hypoglycemia. Accessed Dec. 11, 2020.

- 6 things to know about diabetes and dietary supplements. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/tips/things-to-know-about-type-diabetes-and-dietary-supplements. Accessed Dec. 11, 2020.

- Type 2 diabetes and dietary supplements: What the science says. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/providers/digest/type-2-diabetes-and-dietary-supplements-science. Accessed Dec. 11, 2020.

- Preventing diabetes problems. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/preventing-problems/all-content. Accessed Dec. 3, 2020.

- Schillie S, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recommendations and Reports. 2018; doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6701a1.

- Diabetes prevention: 5 tips for taking control

- Hyperinsulinemia: Is it diabetes?

Associated Procedures

News from mayo clinic.

- Mayo study uses electronic health record data to assess metformin failure risk, optimize care Feb. 10, 2023, 02:30 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Strategies to break the heart disease and diabetes link Nov. 28, 2022, 05:15 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Q and A: Diabetes risk in Hispanic people Oct. 20, 2022, 12:15 p.m. CDT

- The importance of diagnosing, treating diabetes in the Hispanic population in the US Sept. 28, 2022, 04:00 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Managing Type 2 diabetes Sept. 28, 2022, 02:30 p.m. CDT

Products & Services

- A Book: The Essential Diabetes Book

- A Book: The Mayo Clinic Diabetes Diet

- Assortment of Health Products from Mayo Clinic Store

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

- Open access

- Published: 30 April 2022

A qualitative study exploring the barriers to attending structured education programmes among adults with type 2 diabetes

- Imogen Coningsby 1 , 2 ,

- Ben Ainsworth 1 &

- Charlotte Dack 1

BMC Health Services Research volume 22 , Article number: 584 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

5283 Accesses

5 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Diabetes self-management education, a universally recommended component of diabetes care, aims to support self-management in people with type 2 diabetes. However, attendance is low (approx. 10%). Previous research investigating the reasons for low attendance have not yet linked findings to theory, making it difficult to translate findings into practice. This study explores why some adults with type 2 diabetes do not attend diabetes self-management education and considers how services can be adapted accordingly, using Andersen’s Behavioural Model of Health Service Utilisation as a framework.

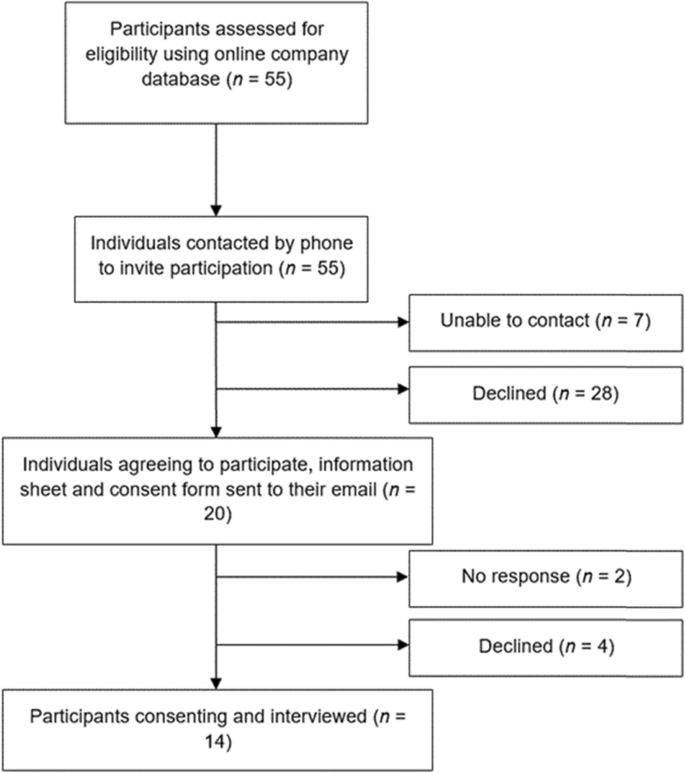

A cross-sectional semi-structured qualitative interview study was carried out. Semi-structured interviews were conducted by telephone with 14 adults with type 2 diabetes who had verbally declined their invitation to attend diabetes self-management education in Bath and North East Somerset, UK, within the last 2 years. Data were analysed using inductive thematic analysis before mapping the themes onto the factors of Andersen’s Behavioural Model.

Two main themes were identified: ‘perceived need’ and ‘practical barriers’ . The former theme explored participants’ tendency to decline diabetes education when they perceived they did not need the programme. This perception tended to arise from participants’ high self-efficacy to manage their type 2 diabetes, the low priority they attributed to their condition and limited knowledge about the programme. The latter theme, ‘ practical barriers’ , explored the notion that some participants wanted to attend but were unable to due to other commitments and/or transportation issues in getting to the venue.

Conclusions

All sub-themes resonated with one or more factors of Andersen’s Behavioural Model indicating that the model may help to elucidate attendance barriers and ways to improve services. To fully understand low attendance to diabetes education, the complex and individualised reasons for non-attendance must be recognised and a person-centred approach should be taken to understand people’s experience, needs and capabilities.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes has the fastest rising prevalence of any long-term condition [ 1 ]. Self-management, defined as a set of skilled behaviours one engages in to manage an illness [ 2 ], plays a central role in keeping blood glucose within a safe threshold in people with type 2 diabetes [ 3 ]. The knowledge and skills needed to self-manage one’s type 2 diabetes are diverse and include numerous daily activities, such as carbohydrate counting, exercise and self-monitoring of blood glucose levels [ 4 ]. When blood glucose levels rise above the normal threshold, this can lead to serious complications such as blindness, renal failure and amputation [ 5 ].

In the UK, diabetes self-management education (DSME) is a recommended component of diabetes care which aims to improve individuals’ knowledge, skills and confidence enabling them to self-manage their type 2 diabetes and improve self-care and clinical outcomes including glycaemic control (level of glucose in the blood) [ 6 ]. DSME has an evidence-based and theory-driven curriculum that is delivered in groups by trained educators [ 6 ]. In the UK, examples of DSME include X-PERT diabetes [ 7 ], a 6-week programme in sessions of 2.5 hours and DESMOND [ 8 ], a 1 or 2 day programme lasting 6 hours in total.

There is strong evidence that DSME confers significant benefits on self-management behaviours as well as clinical, lifestyle and psychosocial outcomes in adults with type 2 diabetes. For example, a randomised controlled trial [ 9 ] found that participation in the DSME programme, X-PERT, led to improvements in a range of outcomes at 14 month follow-up such as glycaemic control, body mass index, waist circumference, cholesterol, diabetes knowledge and psychosocial adjustment. These findings have also been replicated in a national audit of X-PERT diabetes programmes [ 10 ]. Systematic reviews with meta-analysis have also conferred similar positive effects [ 11 , 12 ]. For example, a systematic review [ 13 ] of DSME for people with type 2 diabetes found that, at 1-year follow-up, patient satisfaction and body weight had significantly improved and, at 2-year follow-up, there were significant improvements in blood glucose levels and diabetes knowledge. These findings indicate that DSME is a well-supported intervention to improve clinical, lifestyle and psychosocial outcomes in adults with type 2 diabetes.