An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

Flood protection has blocked this Solr request. See more at The Acquia Search flood control mechanism has blocked a Solr query due to API usage limits

Systematic Review Service: Classes, Consultations, Software, and Databases

Interested in conducting a literature review? There are many types—narrative, rapid, scoping, and systematic—all with different methodologies to use. The NIH Library’s Systematic Review Service is available to guide you through the entire process. We offer classes, consultations, and resources to help you with selecting the most appropriate type of review, writing the protocol, conducting the search, managing the results, and writing and publishing the review.

Classes The NIH Library is offering a series of webinars on conducting various types of reviews. Click on the links below for more information about the classes and to register.

- Introduction to the Systematic Review Process May 3, 12:00‒1:00 PM

- Developing and Publishing Your Protocol May 4, 11:00 AM–12:00 PM

- Selecting the Most Appropriate Type of Literature Review for Your Research May 5, 10:00–11:00 AM

- Developing the Research Question and Conducting the Literature Search May 9, 12:00‒1:00 PM

- Introduction to Scoping Reviews May 10, 1:00‒2:00 PM

- Establishing Your Eligibility Criteria and Conducting the Screening and Risk of Bias Steps in Your Review May 11, 12:00‒1:00 PM

- Exploring the Cochrane Library: Systematic Reviews, Clinical Trials, and More May 18, 11:00 AM‒12:00 PM

- Collecting and Cleaning Data for Your Review May 18, 12:00‒1:30 PM

- Gray Literature: Searching Beyond the Databases May 19, 10:00‒11:00 AM

- Writing and Publishing Your Review May 22, 12:00‒1:00 PM

- Introduction to Rapid Reviews May 23, 1:00‒2:00 PM

- Using Covidence for Conducting Your Review May 24, 12:00‒1:00 PM

- Introduction to Umbrella Reviews: Conducting a Review of Reviews May 25, 1:00‒2:00 PM

- Meta-Analysis: Quantifying a Systematic Review June 6, 1:00–3:00 PM

Consultations NIH Librarians are available to help you select the most appropriate type of review for your research project, identify and complete the steps of your review, conduct the literature search, and edit the final manuscript. Schedule a consultation to get started today.

Covidence: Systematic Review Software The NIH Library provides access to Covidence, an online tool for managing and streamlining your systematic review. Covidence can help you screen citations, conduct data extraction, and perform critical appraisal. For access to Covidence, please use our Software Registration form.

Databases The NIH Library provides access to three primary databases used for most systematic reviews, in addition to many others:

- Cochrane Library Contains high-quality, independent evidence to inform health care decision making, including the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). CENTRAL is a curated registry of randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials conducted worldwide. Search using keywords or controlled vocabulary terms, and export results to a citation management tool.

- Embase Allows users to build comprehensive literature searches through its extensive, deeply indexed database and flexible search options. By applying the PICO (Patient or Problem; Intervention; Comparison or Control; and Outcome) framework, users can structure searches that address clinical questions. Users can search Embase by keywords, controlled vocabulary terms, or use a special search feature to find literature on drugs, medical devices, pharmacovigilance, and more.

- PubMed/MEDLINE Features advanced search functions and filters to find literature for your systematic review. Search using keywords and controlled vocabulary terms from MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) to focus your search and find relevant information.

____________________________

The NIH Library is part of the Office of Research Services (ORS) in the Office of the Director (OD), and serves the information needs of staff at NIH and select HHS agencies.

NIH Library | 301-496-1080 | [email protected] Website | Ask a Question | NIH Library News Subscribe | Unsubscribe

- +91 9884350006

- +1-972-502-9262

- [email protected]

Systematic Review Services

Review by experts, research services.

- Literature Review & Gap

- Meta-Analysis

- Case Report Writing

Systematic Review

- Experimental Design

- Biostatistics

- Grant Writing

- Product Development

A systematic review is designed to summarise the results of available studies and provides a high level of evidence-based findings on the effectiveness of interventions. Our experts can handle any type of research, whether you need systematic review based on controlled clinical trials or review based on observational study designs or community (e.g. psychology) intervention? Our experts at Pubrica, perform a rigorous systematic review by following multi-step process, which includes

(a) Identifying a well-focused clinically relevant research question while following suitable frameworks including PICO, SPICE, SPIDER, and ECLIPSE etc.

(b) Developing a detailed review protocol with strict inclusion and exclusion criteria and registering the protocol at different registries such as The Campbell Collaboration, The Cochrane Collaboration, OSF Preregistration, SYREAF-systematic reviews for animals and food, Research Registry, Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) and PROSPERO.

(c) A systematic literature search of multiple databases (includes PubMed, Embase, MEDLINE, Web of Science, and Google Scholar) in finding relevant references that further requires extensive search and study. A number of other electronic databases and bibliographic sources will also be searched. Sources we posit for use for the project include:

- Scientific literature databases as described above and others

- Cochrane Library

- Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE)

- NHS Economic Evaluation database

- Material referenced in Publications obtained in the course of research on the topic

- International Network of Agencies for Health Technology Assessment (INAHTA) documents

- Clinical trials databases, including clinicaltrialsregister.eu (EU), clinicaltrials.gov (US) and others.

However, using multiple databases to search relevant studies is laborious and time-consuming so that a well-designed search strategy will be developed.

(d) Meticulous study identification using a variety of search terms, checking for a clear outcome (primary and secondary)

(e) Systematic data abstraction, by at least two sets of investigators independently,

(f) Risk of bias assessment with the use of existing different assessment tools (e.g. STROBE). For example, allocation concealment (selection bias), incomplete outcome data addressed (attrition bias), and selective reporting (reporting bias).

(g) Thoughtful quantitative synthesis through meta-analysis where relevant. Besides informing guidelines, credible systematic reviews and quality of evidence assessment can help Identify key knowledge gaps for future studies.

We can help you with the most used qualitative systematic review, as well as, quantitative, health policy and management information and meta-analysis .

Our systematic review at Pubrica is more structured as at every stage of writing, and we ensure to critically check the rigour using standard methodological checklists such as PRISMA, CASP, AMSTAR, and ARIF etc., based on the checklist provided.

- Formulate the research question

- Search for studies

- Selection of studies

- Data collection

- Methodological quality assessment

- Findings are interpreted.

- The time required for producing a quality systematic review

Our Experts:

Pubrica Healthcare and Medical Research Experts provide custom scientific research writing and analytics (data science & biostatistics) services that have a team of experienced researchers and writers who are available round the clock and ready to assist you with the systematic review writing. We have PhD level domain experts who also have decades of scientific writing experience. As such, we have the capability to deliver a high calibre, written literature review. Our experts are very facile around scientific literature databases to complete the literature review, including PubMed & Medline and cancer domain expertise to selectively identify impactful journal articles to draw upon for the review. Written status reports will be shared at every milestone completion including 1) an overview of the status of completion of deliverables including specifics of the literature search and environmental scans; 2) a description of progress addressing discrete components of the Report as agreed; 3) a description of challenges encountered, potential risks and associated mitigation strategies.

Recent trends

Pubrica has done plethora of work in the area of systematic reviews for authors, medical device, pharmaceutical companies and policy makers. Our SR experts ensure to collate empirical evidence that fits prespecified eligibility criteria, an assess its validity through risk of bias, and present and synthesis the attributes and findings from the studies used. All tasks in compliance to PRISMA guidelines and other reporting standards.

We deliver study designs balanced to meet your business needs and expectations with the current scientific understanding and all regulatory requirements considered.

Allow us to help propel your product forward.

Expert Assistance: “Moving from individual, informal tracking Pubrica’s Systematic review service has saved me innumerable hours and costs. They gave me the tools support and control assistance I needed to ensure thorough screening by analysts and clinicians at various locations.” - Rory K., PHD Student, Tulsa.

Quality delivery: “With Pubrica, I was able to produce high quality, accurate work in a much more timely fashion. I really liked what I saw in the final draft, and I was able to get up and running right away with access to live support anytime we need it.” - Melba R., PHD Student, South Hadley.

Client Satisfaction: “I can’t think of a way to do reviews faster than with Pubrica. Being able to monitor progress and collaborate with colleagues makes my life a lot easier.” - Fred A., Springfield.

High Level Experts: “Pubrica is an indispensable part of my systematic review and has allowed me to complete my research effectively and efficiently. It’s enabled me to better manage my increased volume of work.” - Mary V., PHD Student, Lexington.

Trust: “With Pubrica’s systematic review service, I could get my research’s Systematic reviews done and approved quickly and efficiently. The feedback from the notified bodies about the quality and presentation of my systematic review has been extremely positive.” - Glen G., PHD Student, Lexington.

On time delivery: “Pubrica has been instrumental in improving my ability to review full text articles in an efficient and consistent manner. My guide loves the PRISMA diagrams and process outputs which helped me in delivering compliant results that meet their expectations.” - Laura S., PHD Student, Lincoln.

We’ll scale

Up as your needs grow..

No compromising on integrity and quality. Our processes are well defined and flexible to ramp up as per your requirements.

Partnering with

You till the project end..

We come with you all the way. From design to market support

Pubrica Offerings

Pubrica offers you complete publishing support across a variety of publications, journals, and books. You can now morph your concepts into incisive reports with our array of writing services: regulatory writing, Clinical Report Forms (CRF), biostatistics, manuscripts, business writing, physician reports, medical writing and more. Experts in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM), and pundits with therapeutic repertoire. Publishing that medical paper or getting a regulatory drug approval is now easy. Save time and money through Pubrica's support.

Download brochure on our offerings (PDF).

Frequently asked questions

We are with you the whole nine yards. In this section, we answer the tough questions. For any information, contact us via +91-9884350006 meanwhile, here are some of those queries

We provide a wide variety of services such as identifying a well-defined focused clinically relevant question, developing a detailed review protocol with strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, systematic literature search meticulous study identification and systematic data abstraction risk of bias assessment, and thoughtful quantitative synthesis through meta-analysis

Delivery depends on the order type. However, despite the type of order, if you require literature survey chapter, we will provide extensive and critical writing, identifying controversial in literature, referenced documents, fully formatted document, and assurance of plagiarism. Besides, under the Elite plan, we also link the problem gap with the current literature and provide you with a clear problem statement.

We have Develop a well-written scientific & academic research article, Use appropriate citations (e.g., Oxford, APA, and MLA) as necessary. For more about detailed research area plan selection, please visit

To choose the Systematic Review Services, we need clear & precise Domain area. E.g., Medical, Bio-medical, clinical research, Area of interest, Target Country. E.g. the UK, Target State, if any or generalized UK population, Research question, Clearly defining Eligibility criteria, Should have completed Systematic Review., University guidelines and also we need following information such as your Qualification, specialization, University, Country, Your experience, possible areas of your interest, Your supervisor capability and university interest, new methodology that is based on related to your Research and area of interest.

Pubrica hires only experienced and certified professionals from European and UK base. All of our medical writers hold Master and PhD degree and have at least five years of writing experience. Each medical writer have their specialization; it helps us to allocate the most appropriate writer according to your discipline. You will get only subject expertise, that’s our assurance, i.e., every order of thesis provide only a relevant research background.

After confirming your order, work will be assigned to Project Associates (PA), who will check the order according to the requirement. The order will, later on, assign to specific subject experts after signing a non-disclosure agreement. She/he will start working on the project as per the agreed deliverables. The order will be delivered after thorough quality check and assurance by the Quality Assurance Department (QAD) and will be given for plagiarism check. After that, you will get the QAD and plagiarism report.

Our work is completely based on your order and requirement. We promise on following guarantees: (1) On-time delivery (2) Plagiarism free and Unique Content (with the acceptability of less than 5-10% plagiarism) (3) Exact match with your requirements (4) Engaging Subject or domain experts for your project. If there is any deviation in the mentioned guarantees, we take 100% responsibility to compensate. However, the quality of work delivered may also get hampered when there is no precise requirement. In that case, you need to take up a fresh order.

We promise on following guarantees: (1) On-time delivery (2) Plagiarism free and Unique Content (with the acceptability of less than 5-10% plagiarism) (3) Exact match with your order requirements (4) Engaging Subject or domain experts for your project. If there is any deviation in the above guarantees, we take 100% responsibility to compensate.

Yes, at Scientific Writing & Publishing Support, our motto is to work hands-on with clients. We guarantee 100% project satisfaction. So we go exceed their expectations. Full-fledged writing services across all domains; moreover, we also provide animation, regulatory writing, medical writing, research, and biostatistical programming services as well. Call us now to get a quote.

SEE WHAT PUBRICA CAN DO FOR YOU

FILL OUT THE BRIEF FORM BELOW TO GET IN TOUCH.

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

- 3rd Party Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

This website uses Google Analytics to collect anonymous information such as the number of visitors to the site, and the most popular pages.

Keeping this cookie enabled helps us to improve our website.

Please enable Strictly Necessary Cookies first so that we can save your preferences!

Collections and Library Services

- Connecting from Off-Grounds

- IDEA Resources

Introduction

Systematic Review Services and Resources

Need help with a review? Health Sciences Library experts and resources are here for UVA faculty, staff, and students for all types of reviews , from critical reviews, to mapping reviews, to scoping studies, and more. Both the Cochrane Collaboration and the Institute of Medicine recommend authors of systematic reviews work with librarians to identify the best possible evidence. Let us help you prepare your review with the best methods possible.

We fully support UVA faculty, students, and staff in their roles related to health and biomedical research and education, and in patient care. However, due to capacity and licensing limitations, we are unable to provide literature search services for professional society committee members and other professional organizational commitments of faculty. We applaud those professional medical societies that employ librarians to support these types of activities.

Librarian Participation Models We offer two models for librarian participation in systematic and other review types, such as scoping and narrative reviews. Services below are generally limited to UVA Health faculty, staff, and students.

1. Consult model: A librarian will discuss your topic, review any terms you have or show you how to develop search terms, advise on database selection, and give you an overview of the review process. Review teams then run their own searches.

2. Collaboration model: A librarian is part of the review team and due to their contributions, co-authorship is expected. Librarian contributions may include the following:

- formulate research question

- investigate whether there is already a published systematic or scoping review on your topic or whether there is one currently under development

- assist with protocol registration

- recommend databases to be searched, and run the search

- de-duplicate search results

- advise on (or manage) choice of screening software/platforms

- manage PDF availability for full-text screening

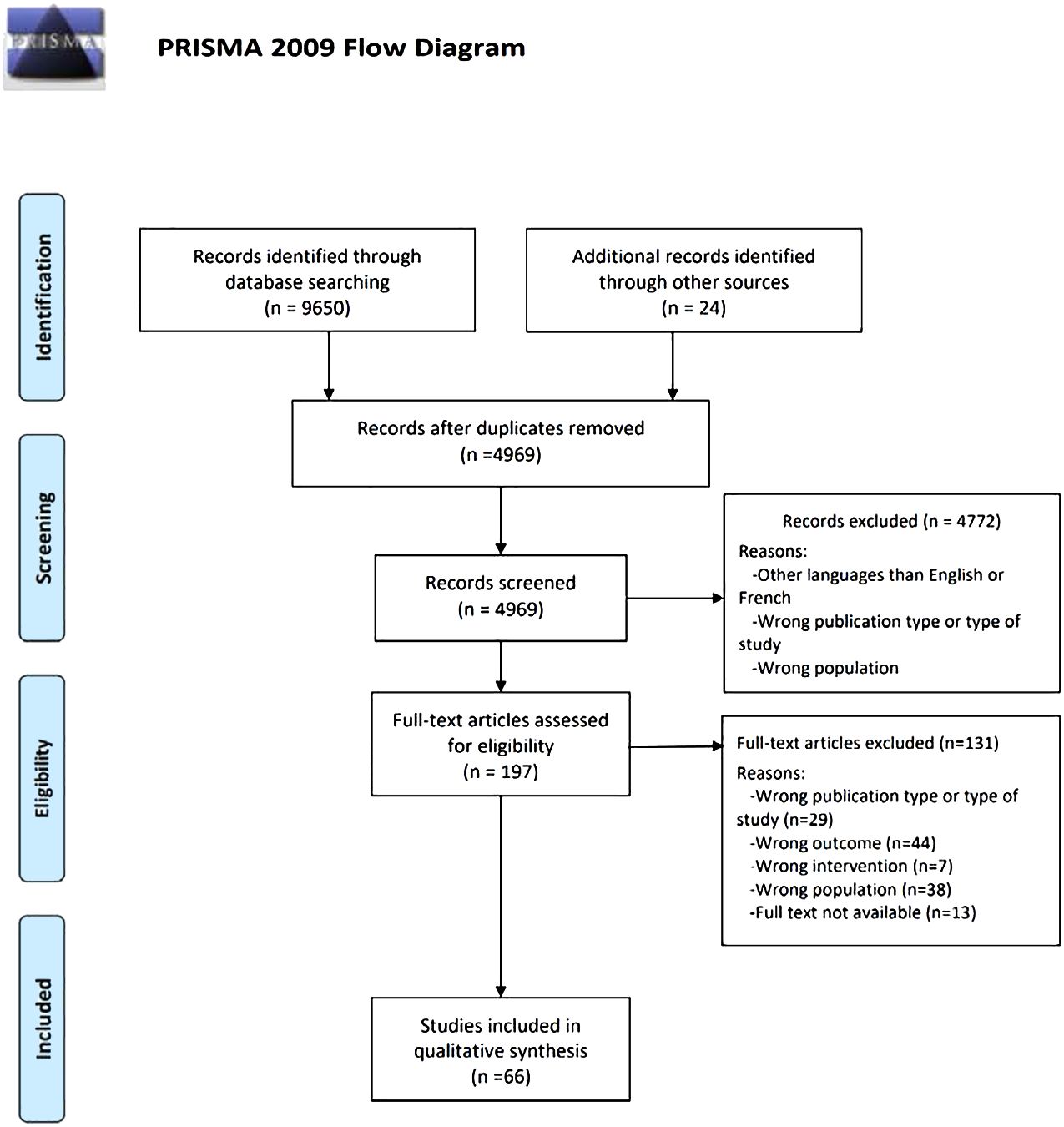

- complete the PRISMA flow diagram

- write the search methods section of the review manuscript and provide appropriate documentation (e.g. full search strategy for one database)

- approve the final manuscript

To request a librarian to participate in your systematic review, please fill out our Systematic Review Request form. If you have questions about our services, please use our Ask Us form

Review Resources

Working on a systematic or other type of review? These guides and tools may be useful:

What Type of Review?

To determine what review is most appropriate for your question, timeframe, or resources, consult this decision tree graphic from U Maryland Health Sciences and Human Services Library

Also consult Systematic Reviews & Other Review Types from Temple University Libraries

- Scroll down to see the process organized into steps/stages

- Helpful links to Critical Appraisal Checklists (i.e. CASP) and Grading the strength of evidence (i.e. GRADE)

A) The Process as a Whole

At-a-Glance

Systematic Reviews: A simplified, step-by-step process (UNC Health Sciences Library)

Think about where you would want to publish your review. What types of reviews does that journal publish? Check out the journal's website or use PubMed's Citation Matcher to search on your journal title, limiting your results to review to see what's been done.

In-Depth Guidance

Useful guides and articles on the basics (and more!) of systematic reviews

New to reviews? This multi-page guide does an excellent job detailing the many steps involved in a systematic review.

Systematic Reviews - Duke University Medical Library

Excellent overview; includes a helpful grid of Types of Reviews and a helpful

Evidence Synthesis & Literature Reviews - Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

Includes tutorials

A Guide to Evidence Synthesis: Steps in a Systematic Review - Cornell University Library

Text and videos provide an overview of the steps in a review with links to useful tools

Systematic Reviews - U Kentucky Libraries

Well-designed layout to lead you through the needed steps

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis — Open & Free Self-paced, asynchronous full tutorial with exercises (developed for the Campbell Collaboration (social sciences).

"Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses" (Cochrane Handbook, Ch. 10) covers the principles and various methods for conducting meta-analyses for the main types of data encountered.

Review Workflow

Guidelines and tools are available to assist you with the planning and workflow of your review.

- PROSPERO is a prospective registry of health-related systematic reviews

- Scoping review protocol from JBI Evidence Synthesis

- PRISMA provides a checklist, flow diagram, and other guidance for reporting

- AHRQ Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews

B) Specific Stages

Managing References

Collecting your citations is an important step in any review. Software and web-based tools assist with this process. All of the following tools have features to help with both formatting your in-text citations and your bibliography.

- EndNote is a powerful software tool for Windows or Mac. EndNote 20 is available at the discounted price of $249.95 ($149.95 for students) via Cavalier Computers . It helps with collecting references as well as PDFs.

- Zotero is a free product and is especially feature-rich in terms of capturing citation information for web pages and other document types.

Want help comparing these tools? See our Citation Managers guide.

Screening and Study Selection

Much of the work in a review involves managing the process of title and abstract screening and study selection. Fortunately there are tools that facilitate this process with features to import citations, screen titles and abstracts, etc.

- Rayyan is a free, Web-based tool

- Covidence is fee-based, but allows one free trial (with two reviewers and up to 500 citations)

- DistillerSR is very feature-rich. It's fee-based (and pricey), but does provide a free student version .

Want to learn more? Check out these resources:

- Inclusion and Exclusion criteria - University of Melbourne Libraries

- SR Toolbox - look up a tool to learn more, or, search by features you want the tool to support (e.g. data extraction).

- Goldet G, Howick J. Understanding GRADE: an introduction . J Evid Based Med. 2013 Feb;6(1):50-54. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12018. PMID: 23557528.

Data Extraction

- Consider consulting similar published reviews and their completed data tables

- Data Extraction - UNC Health Sciences Library

- Sample form for a small-scale review (this example is interventions to increase ED throughput

- Cochrane Data Collection form for RCTs

Quality Assessment

- Quality Assessment - UNC Health Sciences Library

- Spreadsheet of Quality Assessment or Risk of Bias tool choices (Duke Medical Library)

Tools for Creating Risk of Bias Figures

Web app designed for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments to create “traffic light” plots

- Last Updated: Jan 9, 2024 11:53 AM

- URL: https://guides.hsl.virginia.edu/sys-review-resources

- UNC Libraries

- HSL Academic Process

- Systematic Reviews

Systematic Reviews: Home

Created by health science librarians.

- Systematic review resources

What is a Systematic Review?

A simplified process map, how can the library help, publications by hsl librarians, systematic reviews in non-health disciplines, resources for performing systematic reviews.

- Step 1: Complete Pre-Review Tasks

- Step 2: Develop a Protocol

- Step 3: Conduct Literature Searches

- Step 4: Manage Citations

- Step 5: Screen Citations

- Step 6: Assess Quality of Included Studies

- Step 7: Extract Data from Included Studies

- Step 8: Write the Review

Check our FAQ's

Email us

Chat with us (during business hours)

Call (919) 962-0800

Make an appointment with a librarian

Request a systematic or scoping review consultation

A systematic review is a literature review that gathers all of the available evidence matching pre-specified eligibility criteria to answer a specific research question. It uses explicit, systematic methods, documented in a protocol, to minimize bias , provide reliable findings , and inform decision-making. ¹

There are many types of literature reviews.

Before beginning a systematic review, consider whether it is the best type of review for your question, goals, and resources. The table below compares a few different types of reviews to help you decide which is best for you.

- Scoping Review Guide For more information about scoping reviews, refer to the UNC HSL Scoping Review Guide.

- UNC HSL's Simplified, Step-by-Step Process Map A PDF file of the HSL's Systematic Review Process Map.

- Text-Only: UNC HSL's Systematic Reviews - A Simplified, Step-by-Step Process A text-only PDF file of HSL's Systematic Review Process Map.

The average systematic review takes 1,168 hours to complete. ¹ A librarian can help you speed up the process.

Systematic reviews follow established guidelines and best practices to produce high-quality research. Librarian involvement in systematic reviews is based on two levels. In Tier 1, your research team can consult with the librarian as needed. The librarian will answer questions and give you recommendations for tools to use. In Tier 2, the librarian will be an active member of your research team and co-author on your review. Roles and expectations of librarians vary based on the level of involvement desired. Examples of these differences are outlined in the table below.

- Request a systematic or scoping review consultation

The following are systematic and scoping reviews co-authored by HSL librarians.

Only the most recent 15 results are listed. Click the website link at the bottom of the list to see all reviews co-authored by HSL librarians in PubMed

Researchers conduct systematic reviews in a variety of disciplines. If your focus is on a topic outside of the health sciences, you may want to also consult the resources below to learn how systematic reviews may vary in your field. You can also contact a librarian for your discipline with questions.

- EPPI-Centre methods for conducting systematic reviews The EPPI-Centre develops methods and tools for conducting systematic reviews, including reviews for education, public and social policy.

Environmental Topics

- Collaboration for Environmental Evidence (CEE) CEE seeks to promote and deliver evidence syntheses on issues of greatest concern to environmental policy and practice as a public service

Social Sciences

- Siddaway AP, Wood AM, Hedges LV. How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Syntheses. Annu Rev Psychol. 2019 Jan 4;70:747-770. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803. A resource for psychology systematic reviews, which also covers qualitative meta-syntheses or meta-ethnographies

- The Campbell Collaboration

Social Work

Software engineering

- Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering The objective of this report is to propose comprehensive guidelines for systematic literature reviews appropriate for software engineering researchers, including PhD students.

Sport, Exercise, & Nutrition

- Application of systematic review methodology to the field of nutrition by Tufts Evidence-based Practice Center Publication Date: 2009

- Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis — Open & Free (Open Learning Initiative) The course follows guidelines and standards developed by the Campbell Collaboration, based on empirical evidence about how to produce the most comprehensive and accurate reviews of research

- Systematic Reviews by David Gough, Sandy Oliver & James Thomas Publication Date: 2020

Updating reviews

- Updating systematic reviews by University of Ottawa Evidence-based Practice Center Publication Date: 2007

Looking for our previous Systematic Review guide?

Our legacy guide was used June 2020 to August 2022

- Systematic Review Legacy Guide

- Next: Step 1: Complete Pre-Review Tasks >>

- Last Updated: Apr 24, 2024 2:00 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.unc.edu/systematic-reviews

Search & Find

- E-Research by Discipline

- More Search & Find

Places & Spaces

- Places to Study

- Book a Study Room

- Printers, Scanners, & Computers

- More Places & Spaces

- Borrowing & Circulation

- Request a Title for Purchase

- Schedule Instruction Session

- More Services

Support & Guides

- Course Reserves

- Research Guides

- Citing & Writing

- More Support & Guides

- Mission Statement

- Diversity Statement

- Staff Directory

- Job Opportunities

- Give to the Libraries

- News & Exhibits

- Reckoning Initiative

- More About Us

- Search This Site

- Privacy Policy

- Accessibility

- Give Us Your Feedback

- 208 Raleigh Street CB #3916

- Chapel Hill, NC 27515-8890

- 919-962-1053

University Libraries University of Nevada, Reno

- Skill Guides

- Subject Guides

Systematic, Scoping, and Other Literature Reviews: Overview

- Project Planning

What Is a Systematic Review?

Regular literature reviews are simply summaries of the literature on a particular topic. A systematic review, however, is a comprehensive literature review conducted to answer a specific research question. Authors of a systematic review aim to find, code, appraise, and synthesize all of the previous research on their question in an unbiased and well-documented manner. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) outline the minimum amount of information that needs to be reported at the conclusion of a systematic review project.

Other types of what are known as "evidence syntheses," such as scoping, rapid, and integrative reviews, have varying methodologies. While systematic reviews originated with and continue to be a popular publication type in medicine and other health sciences fields, more and more researchers in other disciplines are choosing to conduct evidence syntheses.

This guide will walk you through the major steps of a systematic review and point you to key resources including Covidence, a systematic review project management tool. For help with systematic reviews and other major literature review projects, please send us an email at [email protected] .

Getting Help with Reviews

Organization such as the Institute of Medicine recommend that you consult a librarian when conducting a systematic review. Librarians at the University of Nevada, Reno can help you:

- Understand best practices for conducting systematic reviews and other evidence syntheses in your discipline

- Choose and formulate a research question

- Decide which review type (e.g., systematic, scoping, rapid, etc.) is the best fit for your project

- Determine what to include and where to register a systematic review protocol

- Select search terms and develop a search strategy

- Identify databases and platforms to search

- Find the full text of articles and other sources

- Become familiar with free citation management (e.g., EndNote, Zotero)

- Get access to you and help using Covidence, a systematic review project management tool

Doing a Systematic Review

- Plan - This is the project planning stage. You and your team will need to develop a good research question, determine the type of review you will conduct (systematic, scoping, rapid, etc.), and establish the inclusion and exclusion criteria (e.g., you're only going to look at studies that use a certain methodology). All of this information needs to be included in your protocol. You'll also need to ensure that the project is viable - has someone already done a systematic review on this topic? Do some searches and check the various protocol registries to find out.

- Identify - Next, a comprehensive search of the literature is undertaken to ensure all studies that meet the predetermined criteria are identified. Each research question is different, so the number and types of databases you'll search - as well as other online publication venues - will vary. Some standards and guidelines specify that certain databases (e.g., MEDLINE, EMBASE) should be searched regardless. Your subject librarian can help you select appropriate databases to search and develop search strings for each of those databases.

- Evaluate - In this step, retrieved articles are screened and sorted using the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The risk of bias for each included study is also assessed around this time. It's best if you import search results into a citation management tool (see below) to clean up the citations and remove any duplicates. You can then use a tool like Rayyan (see below) to screen the results. You should begin by screening titles and abstracts only, and then you'll examine the full text of any remaining articles. Each study should be reviewed by a minimum of two people on the project team.

- Collect - Each included study is coded and the quantitative or qualitative data contained in these studies is then synthesized. You'll have to either find or develop a coding strategy or form that meets your needs.

- Explain - The synthesized results are articulated and contextualized. What do the results mean? How have they answered your research question?

- Summarize - The final report provides a complete description of the methods and results in a clear, transparent fashion.

Adapted from

Types of reviews, systematic review.

These types of studies employ a systematic method to analyze and synthesize the results of numerous studies. "Systematic" in this case means following a strict set of steps - as outlined by entities like PRISMA and the Institute of Medicine - so as to make the review more reproducible and less biased. Consistent, thorough documentation is also key. Reviews of this type are not meant to be conducted by an individual but rather a (small) team of researchers. Systematic reviews are widely used in the health sciences, often to find a generalized conclusion from multiple evidence-based studies.

Meta-Analysis

A systematic method that uses statistics to analyze the data from numerous studies. The researchers combine the data from studies with similar data types and analyze them as a single, expanded dataset. Meta-analyses are a type of systematic review.

Scoping Review

A scoping review employs the systematic review methodology to explore a broader topic or question rather than a specific and answerable one, as is generally the case with a systematic review. Authors of these types of reviews seek to collect and categorize the existing literature so as to identify any gaps.

Rapid Review

Rapid reviews are systematic reviews conducted under a time constraint. Researchers make use of workarounds to complete the review quickly (e.g., only looking at English-language publications), which can lead to a less thorough and more biased review.

Narrative Review

A traditional literature review that summarizes and synthesizes the findings of numerous original research articles. The purpose and scope of narrative literature reviews vary widely and do not follow a set protocol. Most literature reviews are narrative reviews.

Umbrella Review

Umbrella reviews are, essentially, systematic reviews of systematic reviews. These compile evidence from multiple review studies into one usable document.

Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal , vol. 26, no. 2, 2009, pp. 91-108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x .

- Next: Project Planning >>

- University of Wisconsin–Madison

- University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Research Guides

- Evidence Synthesis, Systematic Review Services

- Literature Review Types, Taxonomies

Evidence Synthesis, Systematic Review Services : Literature Review Types, Taxonomies

- Develop a Protocol

- Develop Your Research Question

- Select Databases

- Select Gray Literature Sources

- Write a Search Strategy

- Manage Your Search Process

- Register Your Protocol

- Citation Management

- Article Screening

- Risk of Bias Assessment

- Synthesize, Map, or Describe the Results

- Find Guidance by Discipline

- Manage Your Research Data

- Browse Evidence Portals by Discipline

- Automate the Process, Tools & Technologies

- Additional Resources

Choosing a Literature Review Methodology

Growing interest in evidence-based practice has driven an increase in review methodologies. Your choice of review methodology (or literature review type) will be informed by the intent (purpose, function) of your research project and the time and resources of your team.

- Decision Tree (What Type of Review is Right for You?) Developed by Cornell University Library staff, this "decision-tree" guides the user to a handful of review guides given time and intent.

Types of Evidence Synthesis*

Critical Review - Aims to demonstrate writer has extensively researched literature and critically evaluated its quality. Goes beyond mere description to include degree of analysis and conceptual innovation. Typically results in hypothesis or model.

Mapping Review (Systematic Map) - Map out and categorize existing literature from which to commission further reviews and/or primary research by identifying gaps in research literature.

Meta-Analysis - Technique that statistically combines the results of quantitative studies to provide a more precise effect of the results.

Mixed Studies Review (Mixed Methods Review) - Refers to any combination of methods where one significant component is a literature review (usually systematic). Within a review context it refers to a combination of review approaches for example combining quantitative with qualitative research or outcome with process studies.

Narrative (Literature) Review - Generic term: published materials that provide examination of recent or current literature. Can cover wide range of subjects at various levels of completeness and comprehensiveness.

Overview - Generic term: summary of the [medical] literature that attempts to survey the literature and describe its characteristics.

Qualitative Systematic Review or Qualitative Evidence Synthesis - Method for integrating or comparing the findings from qualitative studies. It looks for ‘themes’ or ‘constructs’ that lie in or across individual qualitative studies.

Rapid Review - Assessment of what is already known about a policy or practice issue, by using systematic review methods to search and critically appraise existing research.

Scoping Review or Evidence Map - Preliminary assessment of potential size and scope of available research literature. Aims to identify nature and extent of research.

State-of-the-art Review - Tend to address more current matters in contrast to other combined retrospective and current approaches. May offer new perspectives on issue or point out area for further research.

Systematic Review - Seeks to systematically search for, appraise and synthesis research evidence, often adhering to guidelines on the conduct of a review. (An emerging subset includes Living Reviews or Living Systematic Reviews - A [review or] systematic review which is continually updated, incorporating relevant new evidence as it becomes available.)

Systematic Search and Review - Combines strengths of critical review with a comprehensive search process. Typically addresses broad questions to produce ‘best evidence synthesis.’

Umbrella Review - Specifically refers to review compiling evidence from multiple reviews into one accessible and usable document. Focuses on broad condition or problem for which there are competing interventions and highlights reviews that address these interventions and their results.

*These definitions are in Grant & Booth's "A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies."

Literature Review Types/Typologies, Taxonomies

Grant, M. J., and A. Booth. "A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies." Health Information and Libraries Journal 26.2 (2009): 91-108. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x Link

Munn, Zachary, et al. “Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach.” BMC Medical Research Methodology , vol. 18, no. 1, Nov. 2018, p. 143. DOI: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x. Link

Sutton, A., et al. "Meeting the Review Family: Exploring Review Types and Associated Information Retrieval Requirements." Health Information and Libraries Journal 36.3 (2019): 202-22. DOI: 10.1111/hir.12276 Link

Dissertation Research (Capstones, Theses)

While a full systematic review may not necessarily satisfy criteria for dissertation research in a discipline (as independent scholarship), the methods described in this guide--from developing a protocol to searching and synthesizing the literature--can help to ensure that your review of the literature is comprehensive, transparent, and reproducible.

In this context, your review type , then, may be better described as a 'structured literature review', a ' systematized search and review', or a ' systematized scoping (or integrative or mapping) review'.

- Planning Worksheet for Structured, Systematized Literature Reviews

- << Previous: Home

- Next: The Systematic Review Process >>

- Last Updated: Apr 12, 2024 11:56 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.wisc.edu/literature_review

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PMC10248995

Guidance to best tools and practices for systematic reviews

Kat kolaski.

1 Departments of Orthopaedic Surgery, Pediatrics, and Neurology, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC USA

Lynne Romeiser Logan

2 Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY USA

John P. A. Ioannidis

3 Departments of Medicine, of Epidemiology and Population Health, of Biomedical Data Science, and of Statistics, and Meta-Research Innovation Center at Stanford (METRICS), Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA USA

Associated Data

Data continue to accumulate indicating that many systematic reviews are methodologically flawed, biased, redundant, or uninformative. Some improvements have occurred in recent years based on empirical methods research and standardization of appraisal tools; however, many authors do not routinely or consistently apply these updated methods. In addition, guideline developers, peer reviewers, and journal editors often disregard current methodological standards. Although extensively acknowledged and explored in the methodological literature, most clinicians seem unaware of these issues and may automatically accept evidence syntheses (and clinical practice guidelines based on their conclusions) as trustworthy.

A plethora of methods and tools are recommended for the development and evaluation of evidence syntheses. It is important to understand what these are intended to do (and cannot do) and how they can be utilized. Our objective is to distill this sprawling information into a format that is understandable and readily accessible to authors, peer reviewers, and editors. In doing so, we aim to promote appreciation and understanding of the demanding science of evidence synthesis among stakeholders. We focus on well-documented deficiencies in key components of evidence syntheses to elucidate the rationale for current standards. The constructs underlying the tools developed to assess reporting, risk of bias, and methodological quality of evidence syntheses are distinguished from those involved in determining overall certainty of a body of evidence. Another important distinction is made between those tools used by authors to develop their syntheses as opposed to those used to ultimately judge their work.

Exemplar methods and research practices are described, complemented by novel pragmatic strategies to improve evidence syntheses. The latter include preferred terminology and a scheme to characterize types of research evidence. We organize best practice resources in a Concise Guide that can be widely adopted and adapted for routine implementation by authors and journals. Appropriate, informed use of these is encouraged, but we caution against their superficial application and emphasize their endorsement does not substitute for in-depth methodological training. By highlighting best practices with their rationale, we hope this guidance will inspire further evolution of methods and tools that can advance the field.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13643-023-02255-9.

Part 1. The state of evidence synthesis

Evidence syntheses are commonly regarded as the foundation of evidence-based medicine (EBM). They are widely accredited for providing reliable evidence and, as such, they have significantly influenced medical research and clinical practice. Despite their uptake throughout health care and ubiquity in contemporary medical literature, some important aspects of evidence syntheses are generally overlooked or not well recognized. Evidence syntheses are mostly retrospective exercises, they often depend on weak or irreparably flawed data, and they may use tools that have acknowledged or yet unrecognized limitations. They are complicated and time-consuming undertakings prone to bias and errors. Production of a good evidence synthesis requires careful preparation and high levels of organization in order to limit potential pitfalls [ 1 ]. Many authors do not recognize the complexity of such an endeavor and the many methodological challenges they may encounter. Failure to do so is likely to result in research and resource waste.

Given their potential impact on people’s lives, it is crucial for evidence syntheses to correctly report on the current knowledge base. In order to be perceived as trustworthy, reliable demonstration of the accuracy of evidence syntheses is equally imperative [ 2 ]. Concerns about the trustworthiness of evidence syntheses are not recent developments. From the early years when EBM first began to gain traction until recent times when thousands of systematic reviews are published monthly [ 3 ] the rigor of evidence syntheses has always varied. Many systematic reviews and meta-analyses had obvious deficiencies because original methods and processes had gaps, lacked precision, and/or were not widely known. The situation has improved with empirical research concerning which methods to use and standardization of appraisal tools. However, given the geometrical increase in the number of evidence syntheses being published, a relatively larger pool of unreliable evidence syntheses is being published today.

Publication of methodological studies that critically appraise the methods used in evidence syntheses is increasing at a fast pace. This reflects the availability of tools specifically developed for this purpose [ 4 – 6 ]. Yet many clinical specialties report that alarming numbers of evidence syntheses fail on these assessments. The syntheses identified report on a broad range of common conditions including, but not limited to, cancer, [ 7 ] chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, [ 8 ] osteoporosis, [ 9 ] stroke, [ 10 ] cerebral palsy, [ 11 ] chronic low back pain, [ 12 ] refractive error, [ 13 ] major depression, [ 14 ] pain, [ 15 ] and obesity [ 16 , 17 ]. The situation is even more concerning with regard to evidence syntheses included in clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) [ 18 – 20 ]. Astonishingly, in a sample of CPGs published in 2017–18, more than half did not apply even basic systematic methods in the evidence syntheses used to inform their recommendations [ 21 ].

These reports, while not widely acknowledged, suggest there are pervasive problems not limited to evidence syntheses that evaluate specific kinds of interventions or include primary research of a particular study design (eg, randomized versus non-randomized) [ 22 ]. Similar concerns about the reliability of evidence syntheses have been expressed by proponents of EBM in highly circulated medical journals [ 23 – 26 ]. These publications have also raised awareness about redundancy, inadequate input of statistical expertise, and deficient reporting. These issues plague primary research as well; however, there is heightened concern for the impact of these deficiencies given the critical role of evidence syntheses in policy and clinical decision-making.

Methods and guidance to produce a reliable evidence synthesis

Several international consortiums of EBM experts and national health care organizations currently provide detailed guidance (Table (Table1). 1 ). They draw criteria from the reporting and methodological standards of currently recommended appraisal tools, and regularly review and update their methods to reflect new information and changing needs. In addition, they endorse the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system for rating the overall quality of a body of evidence [ 27 ]. These groups typically certify or commission systematic reviews that are published in exclusive databases (eg, Cochrane, JBI) or are used to develop government or agency sponsored guidelines or health technology assessments (eg, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE], Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [SIGN], Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ]). They offer developers of evidence syntheses various levels of methodological advice, technical and administrative support, and editorial assistance. Use of specific protocols and checklists are required for development teams within these groups, but their online methodological resources are accessible to any potential author.

Guidance for development of evidence syntheses

Notably, Cochrane is the largest single producer of evidence syntheses in biomedical research; however, these only account for 15% of the total [ 28 ]. The World Health Organization requires Cochrane standards be used to develop evidence syntheses that inform their CPGs [ 29 ]. Authors investigating questions of intervention effectiveness in syntheses developed for Cochrane follow the Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews [ 30 ] and undergo multi-tiered peer review [ 31 , 32 ]. Several empirical evaluations have shown that Cochrane systematic reviews are of higher methodological quality compared with non-Cochrane reviews [ 4 , 7 , 9 , 11 , 14 , 32 – 35 ]. However, some of these assessments have biases: they may be conducted by Cochrane-affiliated authors, and they sometimes use scales and tools developed and used in the Cochrane environment and by its partners. In addition, evidence syntheses published in the Cochrane database are not subject to space or word restrictions, while non-Cochrane syntheses are often limited. As a result, information that may be relevant to the critical appraisal of non-Cochrane reviews is often removed or is relegated to online-only supplements that may not be readily or fully accessible [ 28 ].

Influences on the state of evidence synthesis

Many authors are familiar with the evidence syntheses produced by the leading EBM organizations but can be intimidated by the time and effort necessary to apply their standards. Instead of following their guidance, authors may employ methods that are discouraged or outdated 28]. Suboptimal methods described in in the literature may then be taken up by others. For example, the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) is a commonly used tool for appraising non-randomized studies [ 36 ]. Many authors justify their selection of this tool with reference to a publication that describes the unreliability of the NOS and recommends against its use [ 37 ]. Obviously, the authors who cite this report for that purpose have not read it. Authors and peer reviewers have a responsibility to use reliable and accurate methods and not copycat previous citations or substandard work [ 38 , 39 ]. Similar cautions may potentially extend to automation tools. These have concentrated on evidence searching [ 40 ] and selection given how demanding it is for humans to maintain truly up-to-date evidence [ 2 , 41 ]. Cochrane has deployed machine learning to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and studies related to COVID-19, [ 2 , 42 ] but such tools are not yet commonly used [ 43 ]. The routine integration of automation tools in the development of future evidence syntheses should not displace the interpretive part of the process.

Editorials about unreliable or misleading systematic reviews highlight several of the intertwining factors that may contribute to continued publication of unreliable evidence syntheses: shortcomings and inconsistencies of the peer review process, lack of endorsement of current standards on the part of journal editors, the incentive structure of academia, industry influences, publication bias, and the lure of “predatory” journals [ 44 – 48 ]. At this juncture, clarification of the extent to which each of these factors contribute remains speculative, but their impact is likely to be synergistic.

Over time, the generalized acceptance of the conclusions of systematic reviews as incontrovertible has affected trends in the dissemination and uptake of evidence. Reporting of the results of evidence syntheses and recommendations of CPGs has shifted beyond medical journals to press releases and news headlines and, more recently, to the realm of social media and influencers. The lay public and policy makers may depend on these outlets for interpreting evidence syntheses and CPGs. Unfortunately, communication to the general public often reflects intentional or non-intentional misrepresentation or “spin” of the research findings [ 49 – 52 ] News and social media outlets also tend to reduce conclusions on a body of evidence and recommendations for treatment to binary choices (eg, “do it” versus “don’t do it”) that may be assigned an actionable symbol (eg, red/green traffic lights, smiley/frowning face emoji).

Strategies for improvement

Many authors and peer reviewers are volunteer health care professionals or trainees who lack formal training in evidence synthesis [ 46 , 53 ]. Informing them about research methodology could increase the likelihood they will apply rigorous methods [ 25 , 33 , 45 ]. We tackle this challenge, from both a theoretical and a practical perspective, by offering guidance applicable to any specialty. It is based on recent methodological research that is extensively referenced to promote self-study. However, the information presented is not intended to be substitute for committed training in evidence synthesis methodology; instead, we hope to inspire our target audience to seek such training. We also hope to inform a broader audience of clinicians and guideline developers influenced by evidence syntheses. Notably, these communities often include the same members who serve in different capacities.

In the following sections, we highlight methodological concepts and practices that may be unfamiliar, problematic, confusing, or controversial. In Part 2, we consider various types of evidence syntheses and the types of research evidence summarized by them. In Part 3, we examine some widely used (and misused) tools for the critical appraisal of systematic reviews and reporting guidelines for evidence syntheses. In Part 4, we discuss how to meet methodological conduct standards applicable to key components of systematic reviews. In Part 5, we describe the merits and caveats of rating the overall certainty of a body of evidence. Finally, in Part 6, we summarize suggested terminology, methods, and tools for development and evaluation of evidence syntheses that reflect current best practices.

Part 2. Types of syntheses and research evidence

A good foundation for the development of evidence syntheses requires an appreciation of their various methodologies and the ability to correctly identify the types of research potentially available for inclusion in the synthesis.

Types of evidence syntheses

Systematic reviews have historically focused on the benefits and harms of interventions; over time, various types of systematic reviews have emerged to address the diverse information needs of clinicians, patients, and policy makers [ 54 ] Systematic reviews with traditional components have become defined by the different topics they assess (Table 2.1 ). In addition, other distinctive types of evidence syntheses have evolved, including overviews or umbrella reviews, scoping reviews, rapid reviews, and living reviews. The popularity of these has been increasing in recent years [ 55 – 58 ]. A summary of the development, methods, available guidance, and indications for these unique types of evidence syntheses is available in Additional File 2 A.

Types of traditional systematic reviews

Both Cochrane [ 30 , 59 ] and JBI [ 60 ] provide methodologies for many types of evidence syntheses; they describe these with different terminology, but there is obvious overlap (Table 2.2 ). The majority of evidence syntheses published by Cochrane (96%) and JBI (62%) are categorized as intervention reviews. This reflects the earlier development and dissemination of their intervention review methodologies; these remain well-established [ 30 , 59 , 61 ] as both organizations continue to focus on topics related to treatment efficacy and harms. In contrast, intervention reviews represent only about half of the total published in the general medical literature, and several non-intervention review types contribute to a significant proportion of the other half.

Evidence syntheses published by Cochrane and JBI

a Data from https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/reviews . Accessed 17 Sep 2022

b Data obtained via personal email communication on 18 Sep 2022 with Emilie Francis, editorial assistant, JBI Evidence Synthesis

c Includes the following categories: prevalence, scoping, mixed methods, and realist reviews

d This methodology is not supported in the current version of the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis

Types of research evidence

There is consensus on the importance of using multiple study designs in evidence syntheses; at the same time, there is a lack of agreement on methods to identify included study designs. Authors of evidence syntheses may use various taxonomies and associated algorithms to guide selection and/or classification of study designs. These tools differentiate categories of research and apply labels to individual study designs (eg, RCT, cross-sectional). A familiar example is the Design Tree endorsed by the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine [ 70 ]. Such tools may not be helpful to authors of evidence syntheses for multiple reasons.

Suboptimal levels of agreement and accuracy even among trained methodologists reflect challenges with the application of such tools [ 71 , 72 ]. Problematic distinctions or decision points (eg, experimental or observational, controlled or uncontrolled, prospective or retrospective) and design labels (eg, cohort, case control, uncontrolled trial) have been reported [ 71 ]. The variable application of ambiguous study design labels to non-randomized studies is common, making them especially prone to misclassification [ 73 ]. In addition, study labels do not denote the unique design features that make different types of non-randomized studies susceptible to different biases, including those related to how the data are obtained (eg, clinical trials, disease registries, wearable devices). Given this limitation, it is important to be aware that design labels preclude the accurate assignment of non-randomized studies to a “level of evidence” in traditional hierarchies [ 74 ].

These concerns suggest that available tools and nomenclature used to distinguish types of research evidence may not uniformly apply to biomedical research and non-health fields that utilize evidence syntheses (eg, education, economics) [ 75 , 76 ]. Moreover, primary research reports often do not describe study design or do so incompletely or inaccurately; thus, indexing in PubMed and other databases does not address the potential for misclassification [ 77 ]. Yet proper identification of research evidence has implications for several key components of evidence syntheses. For example, search strategies limited by index terms using design labels or study selection based on labels applied by the authors of primary studies may cause inconsistent or unjustified study inclusions and/or exclusions [ 77 ]. In addition, because risk of bias (RoB) tools consider attributes specific to certain types of studies and study design features, results of these assessments may be invalidated if an inappropriate tool is used. Appropriate classification of studies is also relevant for the selection of a suitable method of synthesis and interpretation of those results.

An alternative to these tools and nomenclature involves application of a few fundamental distinctions that encompass a wide range of research designs and contexts. While these distinctions are not novel, we integrate them into a practical scheme (see Fig. Fig.1) 1 ) designed to guide authors of evidence syntheses in the basic identification of research evidence. The initial distinction is between primary and secondary studies. Primary studies are then further distinguished by: 1) the type of data reported (qualitative or quantitative); and 2) two defining design features (group or single-case and randomized or non-randomized). The different types of studies and study designs represented in the scheme are described in detail in Additional File 2 B. It is important to conceptualize their methods as complementary as opposed to contrasting or hierarchical [ 78 ]; each offers advantages and disadvantages that determine their appropriateness for answering different kinds of research questions in an evidence synthesis.

Distinguishing types of research evidence

Application of these basic distinctions may avoid some of the potential difficulties associated with study design labels and taxonomies. Nevertheless, debatable methodological issues are raised when certain types of research identified in this scheme are included in an evidence synthesis. We briefly highlight those associated with inclusion of non-randomized studies, case reports and series, and a combination of primary and secondary studies.

Non-randomized studies

When investigating an intervention’s effectiveness, it is important for authors to recognize the uncertainty of observed effects reported by studies with high RoB. Results of statistical analyses that include such studies need to be interpreted with caution in order to avoid misleading conclusions [ 74 ]. Review authors may consider excluding randomized studies with high RoB from meta-analyses. Non-randomized studies of intervention (NRSI) are affected by a greater potential range of biases and thus vary more than RCTs in their ability to estimate a causal effect [ 79 ]. If data from NRSI are synthesized in meta-analyses, it is helpful to separately report their summary estimates [ 6 , 74 ].

Nonetheless, certain design features of NRSI (eg, which parts of the study were prospectively designed) may help to distinguish stronger from weaker ones. Cochrane recommends that authors of a review including NRSI focus on relevant study design features when determining eligibility criteria instead of relying on non-informative study design labels [ 79 , 80 ] This process is facilitated by a study design feature checklist; guidance on using the checklist is included with developers’ description of the tool [ 73 , 74 ]. Authors collect information about these design features during data extraction and then consider it when making final study selection decisions and when performing RoB assessments of the included NRSI.

Case reports and case series

Correctly identified case reports and case series can contribute evidence not well captured by other designs [ 81 ]; in addition, some topics may be limited to a body of evidence that consists primarily of uncontrolled clinical observations. Murad and colleagues offer a framework for how to include case reports and series in an evidence synthesis [ 82 ]. Distinguishing between cohort studies and case series in these syntheses is important, especially for those that rely on evidence from NRSI. Additional data obtained from studies misclassified as case series can potentially increase the confidence in effect estimates. Mathes and Pieper provide authors of evidence syntheses with specific guidance on distinguishing between cohort studies and case series, but emphasize the increased workload involved [ 77 ].

Primary and secondary studies

Synthesis of combined evidence from primary and secondary studies may provide a broad perspective on the entirety of available literature on a topic. This is, in fact, the recommended strategy for scoping reviews that may include a variety of sources of evidence (eg, CPGs, popular media). However, except for scoping reviews, the synthesis of data from primary and secondary studies is discouraged unless there are strong reasons to justify doing so.

Combining primary and secondary sources of evidence is challenging for authors of other types of evidence syntheses for several reasons [ 83 ]. Assessments of RoB for primary and secondary studies are derived from conceptually different tools, thus obfuscating the ability to make an overall RoB assessment of a combination of these study types. In addition, authors who include primary and secondary studies must devise non-standardized methods for synthesis. Note this contrasts with well-established methods available for updating existing evidence syntheses with additional data from new primary studies [ 84 – 86 ]. However, a new review that synthesizes data from primary and secondary studies raises questions of validity and may unintentionally support a biased conclusion because no existing methodological guidance is currently available [ 87 ].

Recommendations

We suggest that journal editors require authors to identify which type of evidence synthesis they are submitting and reference the specific methodology used for its development. This will clarify the research question and methods for peer reviewers and potentially simplify the editorial process. Editors should announce this practice and include it in the instructions to authors. To decrease bias and apply correct methods, authors must also accurately identify the types of research evidence included in their syntheses.

Part 3. Conduct and reporting

The need to develop criteria to assess the rigor of systematic reviews was recognized soon after the EBM movement began to gain international traction [ 88 , 89 ]. Systematic reviews rapidly became popular, but many were very poorly conceived, conducted, and reported. These problems remain highly prevalent [ 23 ] despite development of guidelines and tools to standardize and improve the performance and reporting of evidence syntheses [ 22 , 28 ]. Table 3.1 provides some historical perspective on the evolution of tools developed specifically for the evaluation of systematic reviews, with or without meta-analysis.

Tools specifying standards for systematic reviews with and without meta-analysis

a Currently recommended

b Validated tool for systematic reviews of interventions developed for use by authors of overviews or umbrella reviews

These tools are often interchangeably invoked when referring to the “quality” of an evidence synthesis. However, quality is a vague term that is frequently misused and misunderstood; more precisely, these tools specify different standards for evidence syntheses. Methodological standards address how well a systematic review was designed and performed [ 5 ]. RoB assessments refer to systematic flaws or limitations in the design, conduct, or analysis of research that distort the findings of the review [ 4 ]. Reporting standards help systematic review authors describe the methodology they used and the results of their synthesis in sufficient detail [ 92 ]. It is essential to distinguish between these evaluations: a systematic review may be biased, it may fail to report sufficient information on essential features, or it may exhibit both problems; a thoroughly reported systematic evidence synthesis review may still be biased and flawed while an otherwise unbiased one may suffer from deficient documentation.

We direct attention to the currently recommended tools listed in Table 3.1 but concentrate on AMSTAR-2 (update of AMSTAR [A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews]) and ROBIS (Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews), which evaluate methodological quality and RoB, respectively. For comparison and completeness, we include PRISMA 2020 (update of the 2009 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews of Meta-Analyses statement), which offers guidance on reporting standards. The exclusive focus on these three tools is by design; it addresses concerns related to the considerable variability in tools used for the evaluation of systematic reviews [ 28 , 88 , 96 , 97 ]. We highlight the underlying constructs these tools were designed to assess, then describe their components and applications. Their known (or potential) uptake and impact and limitations are also discussed.

Evaluation of conduct

Development.

AMSTAR [ 5 ] was in use for a decade prior to the 2017 publication of AMSTAR-2; both provide a broad evaluation of methodological quality of intervention systematic reviews, including flaws arising through poor conduct of the review [ 6 ]. ROBIS, published in 2016, was developed to specifically assess RoB introduced by the conduct of the review; it is applicable to systematic reviews of interventions and several other types of reviews [ 4 ]. Both tools reflect a shift to a domain-based approach as opposed to generic quality checklists. There are a few items unique to each tool; however, similarities between items have been demonstrated [ 98 , 99 ]. AMSTAR-2 and ROBIS are recommended for use by: 1) authors of overviews or umbrella reviews and CPGs to evaluate systematic reviews considered as evidence; 2) authors of methodological research studies to appraise included systematic reviews; and 3) peer reviewers for appraisal of submitted systematic review manuscripts. For authors, these tools may function as teaching aids and inform conduct of their review during its development.

Description

Systematic reviews that include randomized and/or non-randomized studies as evidence can be appraised with AMSTAR-2 and ROBIS. Other characteristics of AMSTAR-2 and ROBIS are summarized in Table 3.2 . Both tools define categories for an overall rating; however, neither tool is intended to generate a total score by simply calculating the number of responses satisfying criteria for individual items [ 4 , 6 ]. AMSTAR-2 focuses on the rigor of a review’s methods irrespective of the specific subject matter. ROBIS places emphasis on a review’s results section— this suggests it may be optimally applied by appraisers with some knowledge of the review’s topic as they may be better equipped to determine if certain procedures (or lack thereof) would impact the validity of a review’s findings [ 98 , 100 ]. Reliability studies show AMSTAR-2 overall confidence ratings strongly correlate with the overall RoB ratings in ROBIS [ 100 , 101 ].

Comparison of AMSTAR-2 and ROBIS

a ROBIS includes an optional first phase to assess the applicability of the review to the research question of interest. The tool may be applicable to other review types in addition to the four specified, although modification of this initial phase will be needed (Personal Communication via email, Penny Whiting, 28 Jan 2022)

b AMSTAR-2 item #9 and #11 require separate responses for RCTs and NRSI

Interrater reliability has been shown to be acceptable for AMSTAR-2 [ 6 , 11 , 102 ] and ROBIS [ 4 , 98 , 103 ] but neither tool has been shown to be superior in this regard [ 100 , 101 , 104 , 105 ]. Overall, variability in reliability for both tools has been reported across items, between pairs of raters, and between centers [ 6 , 100 , 101 , 104 ]. The effects of appraiser experience on the results of AMSTAR-2 and ROBIS require further evaluation [ 101 , 105 ]. Updates to both tools should address items shown to be prone to individual appraisers’ subjective biases and opinions [ 11 , 100 ]; this may involve modifications of the current domains and signaling questions as well as incorporation of methods to make an appraiser’s judgments more explicit. Future revisions of these tools may also consider the addition of standards for aspects of systematic review development currently lacking (eg, rating overall certainty of evidence, [ 99 ] methods for synthesis without meta-analysis [ 105 ]) and removal of items that assess aspects of reporting that are thoroughly evaluated by PRISMA 2020.

Application

A good understanding of what is required to satisfy the standards of AMSTAR-2 and ROBIS involves study of the accompanying guidance documents written by the tools’ developers; these contain detailed descriptions of each item’s standards. In addition, accurate appraisal of a systematic review with either tool requires training. Most experts recommend independent assessment by at least two appraisers with a process for resolving discrepancies as well as procedures to establish interrater reliability, such as pilot testing, a calibration phase or exercise, and development of predefined decision rules [ 35 , 99 – 101 , 103 , 104 , 106 ]. These methods may, to some extent, address the challenges associated with the diversity in methodological training, subject matter expertise, and experience using the tools that are likely to exist among appraisers.

The standards of AMSTAR, AMSTAR-2, and ROBIS have been used in many methodological studies and epidemiological investigations. However, the increased publication of overviews or umbrella reviews and CPGs has likely been a greater influence on the widening acceptance of these tools. Critical appraisal of the secondary studies considered evidence is essential to the trustworthiness of both the recommendations of CPGs and the conclusions of overviews. Currently both Cochrane [ 55 ] and JBI [ 107 ] recommend AMSTAR-2 and ROBIS in their guidance for authors of overviews or umbrella reviews. However, ROBIS and AMSTAR-2 were released in 2016 and 2017, respectively; thus, to date, limited data have been reported about the uptake of these tools or which of the two may be preferred [ 21 , 106 ]. Currently, in relation to CPGs, AMSTAR-2 appears to be overwhelmingly popular compared to ROBIS. A Google Scholar search of this topic (search terms “AMSTAR 2 AND clinical practice guidelines,” “ROBIS AND clinical practice guidelines” 13 May 2022) found 12,700 hits for AMSTAR-2 and 1,280 for ROBIS. The apparent greater appeal of AMSTAR-2 may relate to its longer track record given the original version of the tool was in use for 10 years prior to its update in 2017.