Services on Demand

Related links, south african journal of science, on-line version issn 1996-7489 print version issn 0038-2353, s. afr. j. sci. vol.107 n.5-6 pretoria may./jun. 2011, http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajs.v107i5/6.709 .

BOOK REVIEW

The war for South Africa

Department of Historical Studies, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

Postal address

Book Title: The war for South Africa: The Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902

Book Cover:

Author: Bill Nasson ISBN: 978-0-624-04809-1 Publisher: Tafelberg; R176.76 * Review Title: The war for South Africa

It is a remarkable fact that the centenary of the Union of South Africa last year passed by largely unnoticed by the South African public. Though the centenary of the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902 attracted the attention of the media, the most important consequence of the war, that South Africa became a unified political entity in 1910, was forgotten. However, 110 years ago, the societies of South Africa were at war with each other, fighting to determine who should control the region and what sort of political system should prevail. The British victory in the struggle ensured that, instead of an ill-fitting assortment of Boer republics, African kingdoms and settler colonies, there would be a unified state, knitted together by barbed wire, blood and blockhouses. The new state had some seemingly irreconcilable political differences to manage - protecting the interests of British imperialism whilst simultaneously placating embittered Afrikaners and politically frustrated Africans - but its failures should not obscure how significant unification was, nor that unification was made possible by, and influenced by, war.

There are thus good reasons for us not to forget the war that made South Africa; and Bill Nasson's book is a fresh, lively and thought-provoking reminder not to do so. It is, without doubt, the best general study of the war now available. Though Thomas Packenham's The Boer War is still immensely enjoyable, Nasson's book has a more even coverage of events and is more up to date. The war for South Africa is a complete re-write of Nasson's earlier book on the subject, The South African War, 1899-1902 , written over a decade ago. The present book has benefited from an engagement with much of the new literature that was produced around the centenary of the war, in 1999, and also reflects some of the debates surrounding that centenary. Even 10 years ago the intelligentsia of the New South Africa were questioning the war's relevance to the nation, and some of Nasson's most perceptive writing records that debate. With his customary love of the absurd and his sardonic sense of humour, Nasson's views are far from being politically correct. But there is a lot worth ridiculing when ill-informed politicians attempt to make usable heritage out of a complex and contested past.

The causes of the war have long been a favourite topic to set as an essay question for students of South African history. Nasson's treatment of this question is exemplary and brief. He deals with the relationship between capitalism and imperialism most succinctly, pointing out that whatever the role was that was played by gold and mining interests, the fundamental question was 'Who was South Africa for?' It boiled down to Boer independence versus British control. The claims of Africans were seen as being largely irrelevant. Because Nasson is primarily a social historian this is not, primarily, a military history and he takes care not to lose sight of what impact the war was having on society at large. He does not allow himself to get bogged down in the sort of detail that delights military historians. Instead Nasson briskly discusses the tactics and strategies that evolved as the war took on a life of its own. His is a narrative that downplays the glory and heroism of men in combat to concentrate on the sufferings of ordinary men and women. There are few heroes or villains in these pages. The sieges of Ladysmith, Mafeking and Kimberley, that so inspired the Victorian public to eulogise their plucky defenders, are here portrayed as largely inconsequential. There are no lavish, set-piece battle accounts. Some well-known characters do not feature at all in this history (Kipling, Sol Plaatje) whereas other, lesser-known actors are promoted to our attention (Robert Kekewich). But whoever or whatever Nasson discusses is enlivened by his judicious writing, well spiced with telling quotes and quirky observations.

Nasson's chapters on the aftermath of the war and its impact on South African memory and the heritage industry are particularly impressive. If a nation's political maturity can be judged by the way in which its politicians interpret a complicated and divisive past then we have some way to go until adulthood. In his discussion of the causes of the war Nasson keeps one eye on contemporary events, such as the Allied invasion of Iraq or intervention in Afghanistan. When is it permissible to force war on another country? How does one ensure that one wins the peace after the war as well as the war itself? To what extent is it possible to distinguish between combatants and civilians in military strategy? All of these questions make the South African War a very modern war, a war not just of the 20th century but of the 21st century too. In the end, it seems, if the questions are too hard to answer, the temptation is for politicians to forget about the past completely or to get it spectacularly wrong in the name of inclusive nation building.

Nasson's conclusions are, throughout, objective and fair. This is not a revisionist history with new accusations of atrocious conduct or revelations of genocidal intent. Nor is it an apology for either side. There are no moral pronouncements or value judgements. It is, instead, a careful, subtle reading of the historical context in which actions took place. The military historian John Keegan has reminded us that war is a cultural activity. This means that, when we study wars, we must understand the cultures of those who fight them if we wish to understand the ways in which they are fought. Nasson has this broad, cultural empathy and he shares it with us in a fast-moving, energetic prose style that entertains whilst it instructs and that eschews the use of cliché. This is an outstanding history of the war by an outstanding historian.

© 2011. The Authors. Licensee: OpenJournals Publishing. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License. * Book price at time of review

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

South African War, Union, Segregation

Department of History, University of Kwazulu-Natal

- Published: 08 June 2020

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter examines the politics of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century South Africa. It considers the South African War and itsrole in shaping modern South Africa through the postwar program of reconstruction under the watch of Milner’s kindergarten, in the context of the British imperial project. Factors that led to the war are outlined, including the role of Randlords, followed by a discussion of the reconciliation between the British and the Boers at the expense of black South Africans, the standoff between Smuts and Gandhi, reconstruction, segregation, the marginalization of black South Africans, and the genesis of organized black resistance to white minority rule under which union was forged.

Brian Porter famously claimed that the British were “absent-minded imperialists,” 1 while Ronald Hyam argued that there was “no such thing as Greater Britain, still less a British empire—India perhaps apart. There was only a ragbag of territorial bits and pieces.” 2 John Gallagher and Ronald Robinson contended in their 1950s essay that the British did not have direct formal control over their empire but that their growing economy “integrated remote parts of the globe.” 3 They argued that “the usual summing up of the policy of the free trade empire as ‘trade not rule’ should read ‘trade with informal control if possible; trade with rule when necessary’.” 4 John Darwin suggested that informal empire “represented a pragmatic acceptance of limited power” and reflected “the force majeure of circumstance than the triumph of a principle.” 5 Informal empire ultimately proved unsustainable and local crises in various regions forced the British to adopt formal methods of empire. 6

South Africa provides one instance where the British sought to impose formal control. War between the Boers and the British in 1899 was essentially a struggle between contending white powers for political hegemony in South Africa. 7 The causes and sequence of events leading to the war continue to be debated, but among the factors mentioned by historians are the conflicting political ideologies of British imperialism and Boer republicanism; Britain’s determination to protect its strategic interests in the region in the face of German competition; mineral discoveries on the Witwatersrand, which drew in migrants and magnates in large numbers; the demand for full democratic rights for the mainly British immigrants ( Uitlanders ), which the Transvaal government resisted; the role of mining magnates in promoting war to uphold their economic interests; and the failed attempt by Cecil John Rhodes and Leander Starr Jameson to overthrow the government of Paul Kruger in the Transvaal in 1895, which heightened tension and distrust between both sides.

British attempts to unify the Afrikaner republics and British colonies in a self-governing dominion under white control in order to safeguard Britain’s interests predated the mineral discoveries that transformed the political economy of South Africa. “Inspired by a grandiose imperialist vision,” Lord Carnarvon and Sir Bartle Frere in the 1870s and Sir Alfred Milner and Joseph Chamberlain in the 1890s, colonial secretaries and high commissioners, respectively, were especially active in seeking to secure British interests in South Africa. 8

Britain’s determination to bring South Africa under its influence was a direct cause of the First Anglo-Boer War (1880–1881), which was the only war the British lost in the nineteenth century. The Boers, who had migrated from the Cape, established the independent republics of the Transvaal (or South African Republic) and the Orange Free State (OFS), which were recognized by Britain at the Sand River (1852) and Bloemfontein (1854) conventions, respectively. British expansion in Southern Africa began with the annexation of Basutoland in 1868. Colonial Secretary Lord Carnarvon proposed a confederation of South African states in 1875 in the hope that political stability would lead to economic growth under British rule. The discovery of diamonds in 1867 near the confluence of the Orange and Vaal Rivers and gold on the Rand in the 1880s transformed the political economy of South Africa and rendered the British imperial project more urgent. 9

Defeat in the First Anglo-Boer War did not deter the British, whose policy mold should be seen in the context of the scramble for Africa. Britain’s economic investments were most significant in Egypt and Southern Africa. Its occupation of Egypt in 1882 to defend its “substantial economic interests” triggered events that led to conflict and imperial expansion in West Africa in 1898 and at Fashoda in East Africa later in the year, 10 and that eventually led to war in South Africa. The discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand brought in its wake thousands of European prospectors, and the white population of South Africa increased from 621,000 to 1,117,000 between 1891 and 1904. 11 The Boers regarded the prospectors, especially the English, as Uitlanders (literally, “outlanders”) who posed a threat to their control of the Transvaal, and restricted their voting rights. Only foreigners who had been in the country for fourteen years or more could vote. This caused tension between the Transvaal and British governments as the latter exploited the situation for its own purposes. 12

The Kruger government’s desire to remain independent grew firmer as the Transvaal became the largest producer of gold in the world and replaced the Cape as the economic hub of South Africa. Britain needed a stable gold supply to maintain its preeminent economic position in the world, which made the Transvaal especially attractive. The gold reefs in the Transvaal were very deep, and individual miners soon gave way to large multinational companies. One of the architects of British imperialism in southern Africa was the magnate Cecil John Rhodes, who arrived from Britain in 1870, established a monopoly of the world diamond supply over the next two decades, and became premier of the Cape Colony in 1890. Rhodes was an ardent imperialist. His last will and testament stated: “I contend that we are the first race in the world, and that the more of the world we inhabit the better it is for the human race.” He saw the doggedly independent Paul Kruger and the Transvaal as standing in the way of settler colonial expansion that would facilitate the formation of self-governing components of a British Empire.

Rhodes was determined to prevent the Transvaal from acquiring a route to the sea, which would affect the economies of Natal and the Cape Colony and threaten Britain’s hegemonic position in South Africa. He became emboldened when Joseph Chamberlain became colonial secretary in 1895 and Sir Alfred Milner high commissioner in South Africa in 1897. Like Rhodes, they were determined to change the regime in the Transvaal and thus magnified differences between the Transvaal and British colonies. Rhodes publicized Uitlander grievances, both real and imagined, in his newspapers and together with Jameson plotted an Uitlander uprising to oust Kruger. The so-called Jameson Raid began on 29 December 1895 but ended in disarray owing to differences among the Uitlanders themselves and the fact that most did not feel sufficiently aggrieved to rise against the government. Jameson surrendered on 2 January 1896, and Rhodes paid a political price—he had to resign as premier of the Cape Colony.

Rhodes may have been marginalized politically, but his imperial vision was very much alive. Matters came to a head when Kruger was reelected president in 1898, and his determination to maintain the Transvaal’s independence came up against ardent advocates of British imperial expansion, Milner and Chamberlain, who exploited the question of the Uitlander franchise to heighten political tensions in the Transvaal, eventually leading to war. The war that broke out on 10 October 1899 proved longer, costlier, and more difficult than the British had anticipated. Indeed, British defeats in the initial months in Mafeking, Ladysmith, and Kimberley “induced a sense of crisis for imperial power, and called into question national fighting efficiency and British ‘racial’ vitality, initiative and competence.” The Boers, on the other hand, “fought and resisted with agility, guile, and tenacity in what in many ways came to resemble a people’s war, with numerous rural women involved in the republican war effort or otherwise sucked into hostilities.” 13 British war methods included a scorched-earth policy and imprisoning inmates in concentration camps, which destroyed the agrarian basis of Boer society. An estimated 28,000 Boers died in the camps. 14

While many Boer leaders refused to countenance surrender, it was clear by early 1902 that the British could not be defeated. A younger generation of Afrikaner generals led by the likes of Jan Christiaan Smuts and Louis Botha were pragmatic enough to realize that the very existence of the Afrikaner people depended on the sacrifice of republican independence, at least in the short term. 15 Smuts was born in 1870 in the Cape Colony and studied law at Cambridge University. He returned to South Africa in 1895 and practiced as an advocate in Cape Town. He moved to Johannesburg after the Jameson Raid and in 1898 became state attorney and advisor to the executive council in President Paul Kruger’s government. He distinguished himself in the South African War as a general in the republican forces and was the Transvaal government’s legal adviser at the Vereeniging Peace Conference in 1902. 16 Smuts strongly supported the Treaty of Vereeniging. Facing down Boer militants, he told delegates that “from the prison, from the camps, the graves, the veld, from the womb of the future the nation cries out to us to make a wise decision… We fought for independence, but we must not sacrifice the nation on the altar of independence.” 17

It is now widely acknowledged that this was not a “White man’s war,” a fact reflected in the change in nomenclature from “Anglo-Boer” to “South African” War. Research in the past few decades has underscored black people’s participation in the war and its impact on them. Around a quarter of Boer manpower in the early stages of the war consisted of Africans, who contributed as wagon drivers, guides, and scouts, as well as soldiers, and by its end there were more Africans serving in the British army as scouts, bearers, and transport drivers than there were white fighters on the Boer side. 18 Africans were also placed in segregated, disease-ridden, and unhygienic internment camps, resulting in thousands of deaths, with some estimating that the number of deaths was possibly higher than those suffered by whites, while many died of hunger and starvation. Some Africans gained control of large swathes of the countryside on the Highveld, staking their claim to lost land and making it difficult for Boer commandos to move around, 19 while others looted livestock and robbed Boer farms, with the result that the Boers felt that they were fighting the war on two fronts. Mohandas K. Gandhi led a small contingent of Indian stretcher bearers who served in northern Natal and were active in the siege of Ladysmith in particular. Many whites on both sides of the political divide became concerned about the impact of the war on “the African mind” and were keen to end hostilities. 20

Most historians agree that the war was pivotal in shaping the history of twentieth-century South Africa. Shula Marks described it as South Africa’s

“Great War,” as important to the shaping of modern South Africa as was the American Civil War in the history of the United States. South African Union, on the imperial agenda since the failure of confederation in the 1870s, was born in its ashes, as whites on both sides joined hands to shore up white supremacy against the background of rumours of revolt by restive Africans. If, at one level, it was a war about colonial self-determination—however limited—at another, it was also a war for the survival of a settler society, and about the credibility and international reputation of the British Empire. 21

The years following the war saw Britain seeking reconciliation with its former Boer opponents and eventually granting self-government to a Boer-dominated Union of South Africa in 1910, at the expense of black South Africans, 22 who remained largely powerless with their primary role being to provide unskilled migrant labor.

The truce reached at Vereeniging on 31 May 1902 saw the Boers and British resolve their differences, with the Boers forced to give up their independence in return for the release of prisoners and certain economic and political safeguards, such as the right to keep firearms, the right to their property, and relief for victims of war. Unlike in Canada and Australia, white South Africans settled on unification rather than a federal system even though Natal had argued strongly for a federal structure. Importantly, Clause 8 of the treaty excluded the granting of any form of franchise to Africans until after self-government, which meant that the status of Africans would be determined locally, and in fact they would be excluded from the franchise when the Transvaal and Orange River colony were granted self-government. Many educated and politicized Africans, Indians and Coloureds were disappointed that they gained nothing from the truce. The African leader L. T. Mvabaza told the British prime minister Lloyd George when an African delegation visited London in 1919:

During the Anglo-Boer War of 1899 to 1902, we took the British side as British subjects and fought against the Boers, but when the Peace time came, and the Treaty of Vereeniging was signed our rights were sacrificed. For, then and there, the “colour bar” was accepted by the British. Hence, the question of colour was introduced and sanctioned as a principle of British constitution in South Africa for the first time in the annals of Great Britain. 23

Segregation

The terms of the truce essentially compensated the Boers and sought to maintain the status quo between white and black. Its terms satisfied the Boers as well as British mining capital, which secured control over what Lord Selbourne at the Colonial Office had described in 1899 as “the richest spot on earth.” 24 Generals Botha and Smuts emerged as the most powerful Boer leaders and worked hand in glove with the British in the period from 1902 to 1910 to create a South Africa of white power and privilege, an exclusively white self-governing community whose economic edifice was built on the land dispossession of Africans and a migrant labor system that powered enormous profits from the mines. 25 In the words of J. X. Merriman, a liberal politician from the Cape, whites were reconciled “over the body of the blacks.” 26

A major policy imperative of Milner, who was the high commissioner and governor of the Transvaal from 1897 and Orange River Colony until March 1905, was to get the mining industry up and running. This depended on a plentiful supply of labor, an efficient bureaucracy, and the co-option of the white working class. 27 Milner was pleased that many British soldiers remained in South Africa after the war, as he wanted English migrants to outnumber the Afrikaners by at least three to two in order to lay the foundation for an English-dominated white South Africa. While he believed that whites shared a common outlook on the basis of race and culture, many white migrants came from a working-class background and became involved in worker organizations that challenged mining interests. 28 In contrast, the Boers were able to mask their differences and present a more united front than the English.

Milner’s Kindergarten, the name given to the coterie of Oxford-educated bureaucrats that he appointed to help reconstruct the republics, subscribed to firm ideas of segregation. They saw the empire as divided between Europeans and non-Europeans; at its most extreme between the “civilized” English and “uncivilized” Africans. There was also a substantial Asian population (Indians, Japanese, Chinese) that “occupied a liminal space between these two racial extremes in South Africa as well as within the Empire.” 29 Indians saw themselves as British citizens in terms of Queen Victoria’s edict of 1857, and their struggle for their rights as subjects of the empire was raised powerfully by Gandhi, who spent most of the years between 1893 and 1914 in South Africa.

In his speech at the opening of the British Parliament in 1902, King Edward VII seemed to set the agenda when he called for the “equality of all the white races south of the Zambezi,” rather than “civilised races,” as was the usage prior to the war. 30 Milner, however, was convinced of the need for white supremacy in South Africa: “The white man must rule, because he is elevated by many, many steps above the black man; steps which it will take many centuries to climb, and it is quite possible that the vast bulk of the black population may never be able to climb at all.” 31 Milner declared that he was an “Imperialist out and out.” The empire was bound by the “tie of blood, language, history and traditions common to the British people.” 32 Milner was also aware that whites in South Africa would not tolerate any form of equality with blacks. In a May 1904 speech, he said that it was impossible to make allowances on the race question because of the “extravagance on the part of almost all the whites—not the Boers only—against any concession to any Coloured man.” 33

Lionel Curtis, who was the assistant colonial secretary of the Transvaal from 1903 to 1906 and a key member of Milner’s Kindergarten, opposed the Cape policy of granting franchise to educated Africans. He wrote in 1906 that “the white community must be self-governing; the black community must be ruled autocratically.” Curtis rejected the idea of a few educated blacks entering the portals of white society. He argued that their racial origins would always trump individual personal “success.” 34 Curtis wrote in 1907 that the task of whites was to implement “the best form of government for maintaining the race barrier.” Self-government was only for “progressive” societies at the top of the civilizational ladder (Europeans), while “static” non-Western societies had to be ruled through “autocratic” and “efficient” bureaucracies. 35 Curtis stated in his 1906 farewell speech that his policy had aimed to “keep the Transvaal a white man’s country” and save it from the fate of places like Jamaica and Mauritius, where whites had been displaced from power. 36 Philip Kerr, another member of Milner’s Kindergarten, wrote in 1916 that the fact that humans were divided on a “graduated scale of civility and barbarism was one of the most fundamental facts in human history.” 37

These views were consistent with Smuts’s views on the “Native question,” which were revealed in a letter to the journalist W. T. Stead in January 1902. He described as “shocking” the use of “armed Barbarians [Blacks] under white officers in a war between two white Christian peoples,” as this effectively made blacks “arbiters” in the dispute and thus give them the “casting vote.” This “Frankenstein Monster” would result in South Africa’s relapsing into “barbarism.” 38 While the war would “one day only be remembered as a great thunderstorm, which purified the atmosphere of the subcontinent,” the “evils and horrors of this war will appear as nothing by comparison with its after effects produced on the native mind.” 39 In similar vein, Louis Botha, the Union of South Africa’s first prime minister, testified before the South African Native Affairs Commission (SANAC) that Africans “looked down upon Afrikaners” as a defeated people.

In a talk entitled “The White Man’s Task” at the Savoy Hotel in London on 22 May 1917, Smuts warned that whites had to work hard to forge racial unity because they were living among a mass of Africans who were “uncivilised”: “We know that on the African Continent at various times there have been attempts at civilisation. Where are those civilisations now? They have all disappeared, and barbarism once more rules over the land and makes the thoughtful man nervous about the white man's future in Southern Africa.” Smuts made it clear that in his view there could be “no intermixture of blood between the two colours (white and black). It is probably true that earlier civilisations have largely failed because that principle was never recognised, civilising races being rapidly submerged in the quicksands of the African blood.” Smuts was also determined not to allow Asian migration: “If thousands of Orientals settled in South Africa, the Westerners must go to the wall. Westerners are not prepared to commit suicide and their leaders will not permit them to be reduced to such straits.” 40

In the immediate postwar years in the Transvaal and Orange River Colony, “the most distinguished generals of the guerrilla war were transforming themselves into politicians.” 41 Botha formed Het Volk (“The People”) in January 1905 in the Transvaal, and Afrikaners in the Orange River Colony regrouped under the Oranje Unie led by General Hertzog and Abraham Fischer. These parties represented various Afrikaner interests, and their platform included self-government, job creation for poor whites as a way of appealing to urban workers as well as improving relations between capital and labor, and unity between British and Afrikaner. Hertzog, for example, stated in July 1905 that “it was much better for us to go to the grave with our grievances than to His Majesty’s Government.” Yet less than a year later, in May 1906, he would say at the first party congress of the Oranjie Unie that “broken friendships are restored, and we must … labour that the people of this land shall be cemented together to build up a great and worthy country.” 42

Afrikaners’ quest for self-government was helped by the coming to power of a Liberal Party government in England, led by Henry Campbell-Bannerman, in December 1905. When Smuts traveled to London seeking self-government for the Transvaal, albeit limited to white people, he told Campbell-Banerman that “the only security for the British connection lies—not in armies and ostentatious loyalty of mine-owners—but in the trust and goodwill of the people of South Africa as a whole.” Smuts was convinced that “under the British flag there are peace and contentment, there are justice and equal rights for all, and there is free scope to follow their national ideals and destiny.” 43 Campbell-Bannerman was amenable to Afrikaner demands, pointing out that “though there was an element of risk attached to that course, the alternative of continued forceful suppression of Afrikaners seemed impossible … [and] the increasing tensions in the European system made it essential to stabilise South Africa at once.” 44

The British acceded to Afrikaner demands for self-government, and the Transvaal was granted Responsible Government in 1906, with the Orange River Colony following a year later. 45 The South African Native Congress (SANC) adopted a resolution in 1906 that this move was premature, “considering the very low moral tone of the average colonist in regard to native treatment and their feeling and demeanour towards the native races.” 46 Self-government effectively put the Afrikaners in power in South Africa, meaning that the Afrikaner-British balance of political power was maintained. Smuts emerged as a key figure in the Transvaal, moving from a Boer general fighting the British to calling for the unity of the white “races” of South Africa and eventually becoming “the Henchman of the Empire.” 47 He strove for an Anglo-Afrikaner alliance as a way of forging South African nationhood and preventing further imperial interference. After winning the 1907 election, gave ministerial places to English-speakers and worked with mining magnates, even though the party’s support base was mainly Afrikaners and workers. 48

Milner’s policies had divided the British in the Transvaal. He allied himself with deep-level gold-mining interests while professionals, artisans, and even some diamond mining and outcrop gold–mining executives supported self-government. Lionel Phillips, arguably the most influential representative of mining capital, was aware that in the years just after the war Smuts had labeled the Transvaal government as “almost completely dictated by the magnates.” 49 Phillips had been involved in the Jameson Raid but now realized the need to use financial clout as a way to influence the Het Volk government, because he felt that with the granting of Responsible Government, “the Africander tide is again rising.” 50 For his part, Smuts was aware that mining capital was the main source of income for the Transvaal government and that attacking capital by threatening nationalization could bring swift retribution from Britain and possibly ruin the Afrikaner nationalist project.

There was also the added threat in the Transvaal of a militant white working class dominated by a British born leadership. When around five thousand white mineworkers who felt threatened by the use of Chinese, Afrikaner, and African labor to undertake limited skilled work went on strike in May 1907, Smuts and Botha had no qualms about using force and scab labor to break the strike for the benefit of British Randlords. The state (under Boer control) and capital (in British hands) acted in tandem to protect common interests. As Yudelman points out, there was a gamut of seemingly contradictory demands—mine owners wanting to drive down labor costs, white organized labor seeking to preserve its racial advantage, the government wanting to keep the mines profitable while pushing for more white Afrikaners to enter the mines—out of which a symbiotic relationship emerged between mining capital and the Het Volk government. The government needed the revenue from the mines, and the mine owners needed stability to accumulate capital. 51

White workers also sought to protect their racial privileges. For example, the South African Labour Party (SALP), which was formed in 1910, had a clearly segregationist political platform aimed at confronting both capital and cheap black labor. As Shula Marks points out, “A fusion of militant labor and racist visions was common to the political platform of the imperial working class, whether in South Africa, Britain or Australia.” 52 Jonathan Hyslop’s insightful work shows that, in the first decade of the twentieth century, the white working class was bound together in places like Australia, Canada, South Africa, and Britain into an imperial working class by the movement of people across the empire and the common ideology of white laborism, whose critique of capital for exploiting workers was bound up with a strong racial component, and which was determined to protect the organized power of white workers internationally. 53

Africans, Indians, and Coloureds hoping to find redress under British rule in the Transvaal were extremely disappointed by growing antiblack legislation. For example, Gandhi hoped that Indians’ grievances would be addressed as the treatment of Asians was one of the issues that the British cited in the lead-up to war. Lord Landsdowne, then Secretary of State for War, told a meeting in Sheffield, England, in 1899: “Among the many misdeeds of the South African Republic I do not know that any fills me with more indignation than its treatment of these Indians.” Sir Mancherjee Bhownaggree, the second Indian MP in the British Parliament, would say after the war that he had been “led by the assurances of Cabinet Ministers to cherish the anticipation that the war had for one of its main objects the rescue of British-Indians from the harsh treatment to which they were exposed by the late Boer Republics.” 54

Indians faced discrimination in all South African territories. They were banned from the Orange River Colony; there were restrictions on their entry to the Transvaal and the Cape and segregatory measures for those in the colony; and while Natal continued to import indentured labor until 1911, there were immigration, trade, and residential restrictions and a tax on free Indians aimed at forcing them to return to India. There were many anti-Asian meetings in Natal and the Transvaal in particular. For example, at a meeting on 23 January 1907 at the Builder’s Association on Smith Street, Durban, a Colonial Patriotic Union was formed with the aim of keeping Asians out of Natal and restricting the trading rights of those already there in order to prevent Indians’ “getting the possession of the whole town and drive the proper owners out.” 55 The Durban Political Association (DPA) under Duncan McKenzie passed resolutions calling for the compulsory repatriation of Indians and restrictions on trading by refusing new licenses or the transfer of licenses. It also called for a federation of South Africa “as a white man’s country.” 56 It was in the Transvaal that Gandhi pioneered satyagraha (passive resistance). White Natal was fully behind a unification project based on segregation. Although few in number, Indians commanded the attention of the imperial authorities because of concern that anger about their treatment in South Africa would agitate Indians in India.

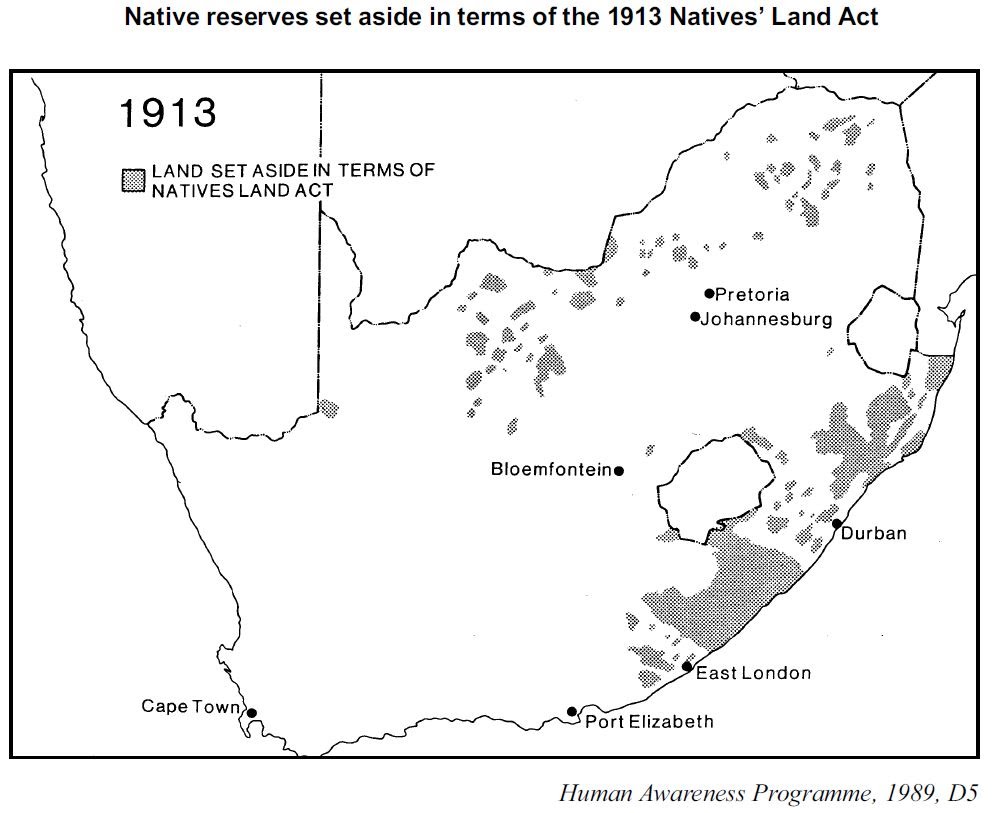

Many African and Coloured leaders conveyed their disillusionment in their evidence before SANAC that British policies did not reflect the “philanthropic” and “kindhearted” treatment that British officials had led them to believe they would receive in return for their loyalty; instead, they were denied land and forced onto the labor market as the traditional basis of their societies was destroyed. Milner appointed SANAC to formulate a national policy for Africans in a future unified South Africa. The commission heard evidence between 1903 and 1905, and its recommendations included measures that in time would be implemented as segregation by the South African state. This included its proposal of territorial segregation to divide the country into black and white areas, which lay behind the 1913 Land Act, the foundation of the policy of segregation; pass laws to control the movement of Africans whose labor was required on the mines and farms and in urban areas; protection of white workers, which would bear fruit in the “Civilised Labour Policy”; and separate political representation for Africans, who were to be controlled through their own traditional institutions. 57

SANAC met at a time of reduced labor supply for the mines and farms because the war had disrupted recruitment in Mozambique, and many Africans from South Africa were loath to return to the Rand because they had accumulated money and cattle or obtained work repairing roads and railways damaged during the war, while others complained of terrible living and working conditions and low wages as the mines, anticipating a flow of labor under British rule, cut wages by half. 58 Officials had to use the South African Constabulary and Native Affairs Commissioners in many rural areas to force Africans back onto farms. The status quo was gradually restored in rural areas as the native commissioners and British administrators persuaded African tenants to pay rent and taxes and return cattle and guns. 59 While some of these restrictive measures had existed previously in one form or another, “it was only during Milner’s Reconstruction administration that they were combined into an overarching general policy.” 60 In the years following union, segregationist policies helped to establish a firm policy of cheap labor for the mines and agriculture by entrenching influx control to prevent permanent African urbanization. 61

While these policies would take effect in future years, the shortage of mine labor had to be addressed as a matter of urgency. The British were not in a position to force African labor to the mines and sought unskilled labor from abroad. Milner tried to recruit Indian indentured workers, but the scheme failed because the Indian government refused the proviso of compulsory repatriation. This increased the ire of Milner and others in the Transvaal, who felt that they were being denied the “desirable” class of Indian (workers), while the parasitical class (traders) was allowed entry. 62 Milner wrote in early 1903 that Chinese labor “would release an immense quantity of niggers for agriculture etc. which they much prefer & I think it ought to be quite possible to keep the yellow man for unskilled labour pure & simple & to ship them home again when they have done it.” 63 Between 1904 and 1907, 63,000 indentured workers were imported from northeastern China and were repatriated by 1910 once African labor became available. 64

It became clear in the period after 1902 that blacks would be denied a meaningful political role in any future dispensation. Indeed, in Natal, Africans had been subject to segregationist measures through the reserves established in the nineteenth century and the imposition of a hut tax and measures such as curfews and pass laws to control influx into urban areas. Difficult economic conditions in the postwar period were compounded by the government’s setting aside several million acres of land in Zululand for white settlement in 1905; stock and crop diseases; and the imposition of a poll tax on males not eligible for the hut tax. Bhambatha of the Zondi led the Zulu Rebellion in April 1906, which lasted several months, led to great loss of life on the Zulu side (3,000, against 30 whites), and generated enormous tension and fear among whites. The Natal government believed that Dininzulu, son of the former king Cetshwayo, was behind the uprising and in 1908 tried him on a charge of treason. Dininzulu was found not guilty in March 1909 but was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment for harboring rebels; in the interim, a commission of inquiry corroborated most African grievances.

Unlike those of the other territories, the 1853 Cape constitution had a qualified male franchise based on income and property that did not discriminate on the basis of race. However, owing to economic inequality, the majority of voters were white. Changes in 1872 and 1887, which included an educational test, made it even more difficult for Africans to qualify to vote, and those who did constituted a tiny elite. The Cape liberal model of “civilized” racial mixing was pushed to the margins as whites debated a union of South Africa. Cape liberalism was, in fact, began to decline in the late nineteenth century, and there was some overtly racial legislation, such as the establishment of a segregated location for Africans in Cape Town in 1902 and the introduction of compulsory educational segregation in 1905 by the School Board Act. Such legislation meant that “Cape liberalism was certainly dented by 1910.” 65

There was a considerable black political awakening and organization in the postwar period leading up to union in 1910. Mission-educated ( amakholwa ) African teachers, farmers, and traders in Natal and the Cape had moved from war as a tool of resistance to petitioning for their rights from the 1860s. While there were a number of local and regional organizations, a loosely structured South African Native Congress (SANC) was formed in 1898 by African political leaders in the Eastern Cape such as Thomas Mqanda, Jonathan Tunyiswa, and Walter Rubusana, to push back against “growing racial discrimination and deteriorating economic conditions.” SANC’s strongest support was in the Eastern Cape and the Transkei, though support grew gradually in other parts of the country. 66 Other organizations that emerged during the Boer War period, a time of profound social, economic, and political crisis for South African society, were the Natal Native Congress (1900), the Cape Native Congress (1902), the Transvaal Native Vigilance Association (1902), and the Orange River Colony Native Vigilance Association (1903). 67 The Transvaal Native Congress (TNC) was formed on the initiative of SANC in 1905 by leaders of independent African churches, chiefs, and secular groups and often intervened on behalf of African mineworkers. The African Political (later People’s) Organisation (APO) was formed in Cape Town in 1902; its program, which placed strong emphasis on improving Coloured education and extending the Coloured franchise to the northern colonies, was shaped to a large extent by the Scottish-trained medical doctor Abdullah Abdurahman, who was president from 1905 to 1940.

In 1902 SANC sent a resolution to the British government calling for protection of the interests of African and Coloured people in the face of moves to curtail their freedoms. SANC passed a resolution at its April 1906 congress that political unity “founded on the political extinction of the Native element would be shortsighted” and criticized the Cape government’s failure to protect Africans rights and attacks on Africans by the “capitalistic press.” It also defended African workers’ consumption of beer. 68 Delegates questioned how the British government could reconcile its commitment to South Africa as a “white man’s country” with its “solemn pledges of protection to the weaker races” and stated that they preferred being ruled directly by the British to the racist white governments. Delegates viewed the removal of the “imperial factor” with “extreme gravity.” 69

These organizations and African-owned newspapers, such as John Tengo Jabavu’s Imvo Zabantsundu in King William’s Town; Walter Rubusana’s Izwi Labantu ( Voice of the People ) in East London; Silas Morema and Sol Plaatjie’s Koranta ea Becoana ( Bechuana’s Gazette ); Plaatjie’s Tsala ea Batho ( The Friend of the People ); the Pietermaritzburg-based Inkanyiso yase Natal ( Light of Natal ); and John Dube’s Ilanga lase Natal were elitist, accommodationist, and essentially conservative, highlighting the grievances and aspirations of the African bourgeoisie in the main; but they occasionally spoke out against the terrible treatment of African workers in the mines, employers’ failure to provide medical care, the pass laws, lack of employment opportunities for educated Africans, and so on. 70 However, it was only with the founding of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC) in 1912 that these issues appeared on the national stage.

Eight years after the truce of Vereeniging, the Union of South Africa came into being on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Transvaal, Natal, the Cape Colony, and the Orange River Colony. It was founded as a dominion of the British Empire, with the British monarch represented by a governor-general in South Africa.

The movement toward unification was given impetus from around 1905 by the need for a unified native policy to make labor available for the farms and mines in different parts of the country; the need for a common railways, customs, and tariffs policy to eradicate competition between these self-governing colonies; and the fear of a national African uprising following the Bhambatha Rebellion in Natal. The quest for unity was driven by both imperialists and anti-imperialists. Imperialists hoped that a British electoral majority would help to secure their interests in the region, while republicans anticipated that unification would both address the problems common to the colonies and create a common purpose among white South Africans to end imperial interference in the region.

Shula Marks notes that this rapid unification “was partly a product of the tremendous white insecurities unleashed by the war. … White unity was forged in the face of the fear of Africans brought on by the war.” 71 The struggle between white and white did not take place in a vacuum; “at any given time, there was either a resistance war going on somewhere or one had just finished, or there were rumours of another (African) outbreak.” 72 The white colonies feared that rebellion could spread to their territories and felt compelled to unite to thwart such danger.

Milner left South Africa in April 1905, and the quest for unification on the British side was led by the likes of his successor as high commissioner, Lord Selbourne, and Lionel Curtis. Selborne and Curtis prepared the so-called Selborne Memorandum, which was introduced in the Cape Parliament in July 1907 and advocated strongly for unification because disunity was “crippling the power of government to remove obstacles from the path of enterprise.” 73 In 1908 the Kindergarten published The Government of South Africa , which, in two volumes written mainly by Curtis, argued in favor of unitary government as most appropriate in the particular circumstances in South Africa. The Kindergarten established a public association called the Closer Union Societies and a journal entitled The State to publicize their vision of a unified South African state within the British Empire. 74

South Africa, they hoped, would join Canada, Australia, and New Zealand as self-governing dominions, which were “a crucial supplement to Britain’s strategic strength at a time of growing international tension in Europe.” 75 These dominions were to be white ruled. Lord Elgin wrote to his successor as Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord Crewe, in 1908 that giving equality to “civilised men” in South Africa would be dangerous because a time will come when “the natives will control the elections. Are we prepared to subordinate the whites to native rule under such circumstances?” 76 Sir Charles Lucas, of the Dominion Department, was of the view that Britain would not “confront its Dominions on the issue of imperial citizenship,” since they were of more value to Britain than Britain was to them; in any case, he added, most “Coloured people were unfit to rule.” 77

In his farewell speech in Johannesburg in March 1905, Milner described the British Empire as a group of states, “all independent in their own local concerns, but all united for the defence of their own common interests and the development of a common civilization; united not in an alliance—for alliances can be made and unmade … but in a permanent organic union.” His vision was of an empire consisting of a group of white self-governing communities bound by a common “civilization” in which the various “elements would gravitate towards each other in a ‘natural’ way, and … each played a role in sustaining the entity as a whole.” 78 Speaking in Ottawa, Canada, in 1908, Milner stated that it was a great boon “for every white man of British birth, that he can be at home in every state of the Empire from the moment he has set foot in it, though his whole previous life may have been passed at the other end of the earth.” 79

The immediate reaction to unity among white South African leaders was subdued, but this changed by early 1908, when Jameson’s Imperial Party was defeated by the South African Party in the Cape. The latter was led by the English-speaking John X. Merriman but was composed mainly of members of the Afrikaner Bond, while the Transvaal and the Orange River Colony had become self-governing. This meant in effect that three of the four self-governing colonies were under anti-imperialist governments, and their leaders, according to Leonard Thompson, began to seriously countenance union and were able to “control the process of unification” rather than follow the lead of British administrators. 80 However, Vineet Thakur, Alexander E. Davis, and Peter Vale argue that the Kindergarten “understood itself as having a background role in the process,” with Lord Selborne writing to Lionel Curtis in February 1909 that without his penning The Government of South Africa , “we never should have got such an excellent form of constitution. … Milner’s Kindergarten will have more profoundly influenced the history of South Africa than any combination of Afrikanders (sic) has ever done.” 81

A National Constitutional Convention was organized with meetings held in Durban and Cape Town between October 1908 and February 1909, when a report and draft constitution were prepared, and an amended draft was unanimously adopted on 1 June 1909. Natalians favored federation, but their Zulu “problem” and the economic incentives of unification left them with no option but to become a part of the union. 82 In July 1909 the four governments sent delegates to London, where they discussed the draft constitution with Lord Crewe. The British government subsequently passed the South Africa Bill, and thus was born, in 1910, the Union of South Africa.

The most highly contested issue was the African franchise. Delegates from the Cape Colony pushed for an education and property franchise, while the other three colonies demanded an all-white male one. SANAC reported in 1905 that of 135,168 voters in the Cape, 18,279 were African, mainly in the eastern parts. Merriman, the Liberal politician from the Cape, had written to Smuts on 6 March 1906 that disenfranchisement did not offer “any prospect of permanence. Is it not rather building on a volcano, the suppressed force of which must someday burst forth in a destroying flood, as history warns us it has always done?” Smuts replied that he did not believe “in politics for them” (black South Africans). 83 Delegates agreed to maintain the status quo in each colony. Thus, Africans had a qualified franchise in the Cape, but only whites could stand for election to the national parliament on their behalf. Coloureds enjoyed the franchise but from 1930 were restricted to electing white representatives. While all white males had the right to vote, Boer women in particular, who had made great sacrifices during the war and had become highly politicized, were denied it. It was not until 1930 that white women got the vote.

Black South Africans were wary of the move toward unification. The newspaper Izwi Labantu stated in an editorial on 16 July 1907 that under the watch of racists and capitalists South Africa would “be a glorious country for corporation pythons and political puff-adders, forced labor and commercial despotism, but no fit place for freedom to live in.” 84 African fears of the consequences of unification intensified, and countrywide meetings culminated in March 1909 in a South African Native Convention in Bloemfontein, where the draft constitution was discussed. The sixty delegates accepted that union was necessary for progress, deemed it the responsibility of the British government to ensure that Blacks were given the same privileges as whites, and called upon the British government to extend the franchise to Africans and Coloureds and to remove the color bar in the Union parliament. They resolved that if the National Convention did not remove the color restrictions in the draft constitution, they would send a delegation to England to rally against the draft South Africa Act. 85

The delegation went to London in June 1909. Walter Rubusana, Daniel Dwanya, and Thomas Mapikela represented the SANC in the delegation and the physician Abdullah Abdurahman the APO delegation. Both delegations were led by W. P. Schreiner, a Cape Liberal barrister and MP, and the brother of the author and antiwar campaigner Olive Schreiner. 86 The African Political Organisation (APO) convened a national congress of Coloureds in April 1909, at which delegates called for the extension of the franchise to “all qualified men irrespective of race, colour or creed throughout the contemplated Union.” 87 In an editorial in its newsletter APO , dated 5 June 1909, the leadership was confident that English people would “never be dragooned into bartering away the glorious reputation won by their ancestors as lovers of freedom and asserters of the rights of humanity.” Schreiner told Reuters on 3 July 1909 that the delegations had come “to try to get the blot removed from the Act, which makes it no Act of Union, but rather an Act of Separation between the minority and the majority of the people of South Africa.” Schreiner wanted South Africa to move up to the Cape’s standards as far as the rights of Blacks were concerned, and not down to those set by the Boer republics. The APO and SANC delegations secured the support of the Anti-Slavery and Aborigines Protection Society, the London Missionary Society, and the South African Native Races Committee. 88