An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

- PMC10001968

A Current Review of Water Pollutants in American Continent: Trends and Perspectives in Detection, Health Risks, and Treatment Technologies

Associated data.

Not applicable.

Currently, water pollution represents a serious environmental threat, causing an impact not only to fauna and flora but also to human health. Among these pollutants, inorganic and organic pollutants are predominantly important representing high toxicity and persistence and being difficult to treat using current methodologies. For this reason, several research groups are searching for strategies to detect and remedy contaminated water bodies and effluents. Due to the above, a current review of the state of the situation has been carried out. The results obtained show that in the American continent a high diversity of contaminants is present in the water bodies affecting several aspects, in which in some cases, there exists alternatives to realize the remediation of contaminated water. It is concluded that the actual challenge is to establish sanitation measures at the local level based on the specific needs of the geographical area of interest. Therefore, water treatment plants must be designed according to the contaminants present in the water of the region and tailored to the needs of the population of interest.

1. Introduction

Water contamination represents a current crisis in human and environmental health. The presence of contaminants in the water and the lack of basic sanitation hinder the eradication of extreme poverty and diseases in the poorest countries [ 1 ]. For example, water sanitation deficiency is one of the leading causes of mortality in several countries. Due to unsafe water and a lack of sanitation, there are several diseases present in the population [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Therefore, the sixth global objective of the United Nations, foreseen as part of its sustainable development agent 2030, aims to guarantee the availability and sustainable management of water resources. In this sense, numerous research groups have focused on proposing alternative solutions focusing on three fundamental aspects: (a) detection of contaminants present in water for human consumption, (b) assessment of risks to public and environmental health due to the presence of contaminants in the water, and (c) the proposal of water treatment technologies. In the case of the American continent, the detection of contaminants (inorganic and organic) has been studied; the research works show alarming results in which the impact of water pollution is demonstrated, how the ecosystem is being affected, and consequently the repercussion towards human health [ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ]. This last point becomes worrying due to the fact that there are reported cases in which newborns, children, and adults consumed drinking water from various sources (such as rivers, lakes, groundwater, and wells) without the certainty that it is free of contaminants, representing a health risk factor [ 9 , 10 , 11 ]. Some of the detected contaminants have been associated with a potential health risk, such as the case of some disinfectants with cancer [ 12 ] and NO 3 − and NO 2 − as potential carcinogens in the digestive system [ 13 ]. The lack of safe drinking water has been reported in several countries [ 3 , 14 ] since the presence of contaminants in water has demonstrated that actual quality controls are not able to detect or treat pollutants that are present [ 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ].

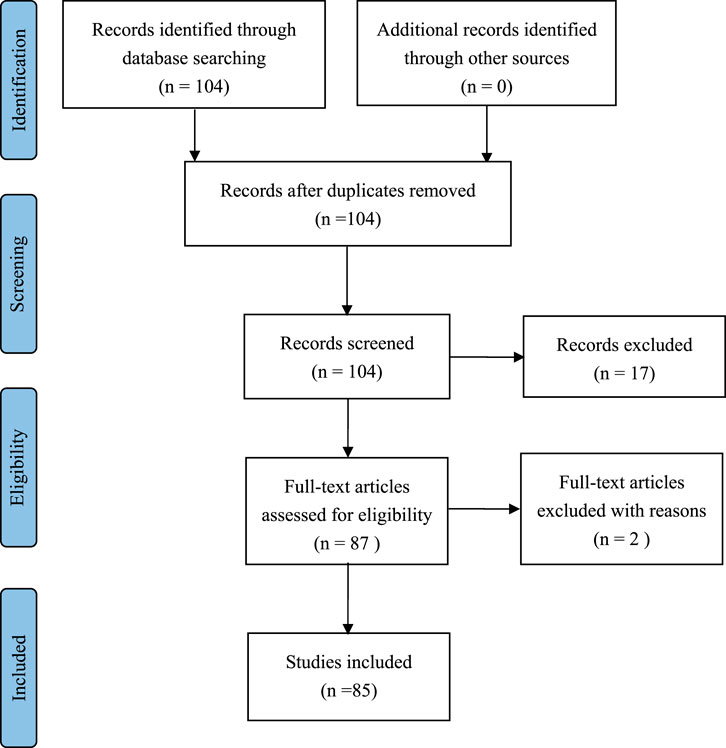

In this sense, numerous research groups have focused on proposing alternative solutions focusing on three fundamental aspects: (a) the detection of contaminants present in water for human consumption, (b) assessment of risks to public and environmental health due to the presence of contaminants in the water, and (c) a proposal for water treatment technologies. This communication shows a critical review of the latest published research works. The use of Web Of Science from Clarivate Analytics was used for the bibliographic review. The bibliographic search was carried out in January 2023 using the keywords “public health pollutants/contaminants water” + “name of the American country.” The retrieved articles were filtered considering the following: (i) articles published in the period 2018–2023, (ii) articles carried out based on effluents and bodies of water belonging to the American continent, and (iii) articles that demonstrate the presence and/or treatment of organic (excluding biological contaminants) and inorganic contaminants in water. The selection of these research articles was used to carry out a critical review of the current situation to propose future challenges to achieve efficient, and sustainable water treatment processes.

2. Critical Review: Evaluation of the Current Situation, Perspectives, and Challenges in the Detection of Contaminants, Health Risk Assessment, and Water Treatment Technologies in the American Continent

2.1. detection of contaminants in water.

At present, there are various analytical techniques that have been used in the detection and quantification of inorganic and organic contaminants in aqueous matrices. Mainly, these techniques can be divided into three major groups: chromatographic, spectroscopic, and other techniques, such as electrochemical and colorimetric titration. A comparison of the advantages and disadvantages of the most commonly used analytical techniques is presented in Supplementary Table S1 . From these, techniques that have been used the most are shown below.

In chromatographic techniques, the most reported are gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), gas chromatography/mass spectrometry with selected ion monitoring (GC-MS/SIM), liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), liquid chromatography quadrupole time-of-flight- mass spectrometry (LC-QTOF-MS), high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI-MS), ultra-performance liquid chromatography- electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (UPLC-ESI-MS), high-performance liquid chromatography-charged aerosol detector (HPLC-CAD), and ion chromatography (IC). In the case of spectroscopic techniques, these include inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS), inductively coupled plasma dynamic reaction cell mass spectrometry (ICP-DRC-MS), thermal ionization mass spectrometry (TIMS), high resolution inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (HR-ICP-MS), particle-induced X-ray emission (PIXE), fluorescence spectrometry, inductively coupled optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES), and cold vapor atomic absorption spectrophotometry (CVAAS).

From these techniques, it has been possible to determine the concentrations of various pollutants of interest to human health and the environment.

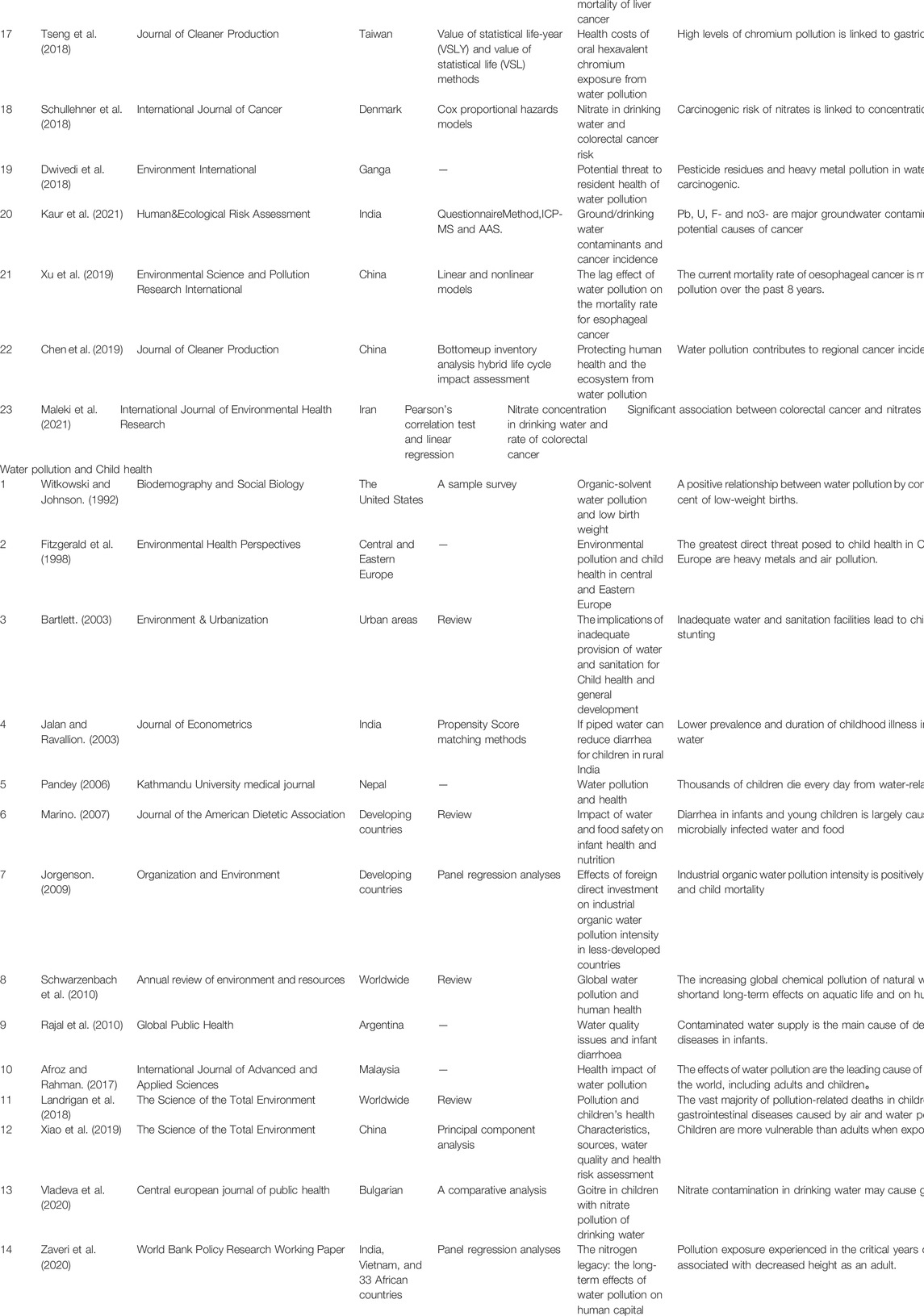

The compilation of information from the latest scientific reports (related to the detection of inorganic contaminants present in the water) is shown in Table 1 and Figure 1 (geographical distribution). On the other hand, the comparison of the detection limits for the limits of interest using different analytical techniques is presented in Supplementary Table S2 . Among them, some works have been carried out based on water bodies in different countries, such as Canada [ 19 ], USA [ 20 , 21 , 22 ], Mexico [ 23 ], and Brazil [ 24 ], in which the presence of As, Fe, U, Zn, Na, K, Ca, Mg, HCO 3 − , and Hg with respect to interactions among water, bedrock mineralogy, and geochemical conditions of the region has been studied, so they can be classified as contamination due to a natural source. A particular case can be analyzed for U, which is present in water bodies of the southwest and west central USA, because high levels of acute exposure can be fatal for the population, and chronic exposure at low levels is associated with health problems, such as renal and cardiac risk. Although, exposure studies of surrounding communities cannot be considered conclusive, they correspond to a great advance in the field, and future studies should be carried out to assess possible damage to human health and the ecosystem.

Geographical distribution of pollutants detected in the American continent in different matrices (water, blood, sediments, biota) in the last 5 years.

On the other hand, research works stand out showing that water pollution can occur due to anthropogenic activities [ 25 ], being evident that modern practices of agriculture and livestock have consequences as the indiscriminate use of fertilizers, pesticides, and hormones results in nitrates in the water, which are associated with a risk of congenital anomalies, such as heart and neural tube defects.

Within the works carried out, one of the most concurrent techniques used in the evaluation of contaminants has been performed via ICP (MS or OES) due to its high precision, low cost, low detection limits, and the advantage of analyzing a large number of elements simultaneously in a short time [ 26 ]. However, in some cases, the detection limits of the technique are above the maximum permissible limits proposed by the WHO (World Health Organization), such is the case of Hg, for which the detection limit is of 0.0025 mg L − 1 and the maximum detection limit recommended by the WHO is 0.002 mg L − 1 . Therefore, it is concluded that one of the challenges to be dealt with for metal detection in water is based in the fact that current techniques must be complemented by advanced analytical techniques, such as electrochemical tests [ 27 ]. These techniques are of great interest for their study due to the benefits they have, such as improvements in detection limits, low operating costs, short analysis times, and mobility, being able to perform analytical determinations in situ [ 27 ]. It is concluded that the contaminants with the greatest presence in the continent are As, U, Pb, Mn, Se, and Hg, mainly related to the mineralogy of the analyzed site and anthropogenic activities in the analysis areas. However, in some cases, the source of contamination is natural and occurs periodically due to seasonal changes, with the rainy season being the period with the greatest presence due to the mobility of metals contained in the rock and soil of the region [ 28 , 29 ]. Moreover, the presence of ions in solution related to the use of fertilizers and agrochemicals in crop fields has also been documented [ 30 ]. It is important to denote that the origin of the contamination source is not accurately concluded, providing a current challenge for the exact determination of the source to propose containment and sanitation actions to solve the problem.

Detection of inorganic pollutants in environmental samples.

Research studies presented in Table 1 demonstrated the potential human health risks that metal presence can have in water bodies, being important to highlight that there is still a need to evaluate the impact that inorganic contaminants have on human health. Furthermore, several research groups in different countries have detected the presence of contaminants not only in the supply sources, such as water bodies, but also in aquatic environments, such as flora and fauna being affected and representing economic importance since certain species can be traded, based on great demand to satisfy local and international markets.

On the other hand, organic contaminants can be divided into several groups; nevertheless, the principal groups are the ones denominated as persistent organic pollutants (POPs). These pollutants have an important impact on the environment and human health. Some examples are per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), personal care products, pharmaceutical compounds, pesticides, phenolic compounds, dyes, hormones, sweeteners, surfactants, and others.

Their detection has been primarily necessary to assess the effects that these pollutants have. Most of them are primarily obtained from industrial activities having different uses, such as flame retardants, coolants, cement, and others. Their presence represents an important contribution to water ecotoxicity (Ecuador, Argentina, Mexico) that affects the integrity of the species that inhabit that ecosystem [ 53 , 54 , 55 ].

Important issues have been detected in aquatic environments. The bioaccumulation of several organic compounds, such as polychlorinated biphenyl compounds (PBCs) and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), in important water bodies, such as Lake Chapala (Mexico), has been reported, through the analysis of samples recollected from water, fish, and sediments from two local seasonal periods. In this case, the fish analyzed were Cyprinus carpio , Oreochromis aureus , and Chirostoma spp., establishing that these chemical substances can reach the lake via industrial activities and strong winds and enter from the Lerma River (Mexico) [ 55 ].

In the study of Ramos et al. (2021), a water analysis was performed in the river and its treated water throughout a year in Minas-Gerais (Brazil). The detection of seventeen phenolic compounds with a single quadrupole gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer equipment (GCMS-QP2010 SE) coupled with a flame ionization detector (FID) was analyzed. From the samples analyzed, only sixteen were detected, being that 3-methylphenol was the only one not detected. In raw water, the detection of 2,3,4-trichlorophenol, 2,4-dimethylphenol, and 4-nitrophenol was found with the most frequency and for treated water, 4-nitrophenol and bisphenol A, establishing that a health risk to the environment and humans was identified with the contamination of these phenolic compounds [ 56 ]. Another study carried out in the St. Lawrence River, Quebec, (Canada), was performed based on an analysis of surface water for the detection of ultraviolet absorbents (UVAs) and industrial antioxidants (IAs). The detection was carried out via gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) detecting several groups of UVAs, such as organic UV filters (benzophenone (BP), 2-ethylhexyl salicylate (EHS), 2-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzophenone (BP3), 3,3,5-trimethylcyclohexylsalicylate (HMS), 2-ethylhexyl 2-cyano-3,3-diphenylacrylate (OC), and ethylhexyl methoxycinnamate (EHMC)), aromatic secondary amines (diphenylamine (DPA)), benzotriazole UV stabilizers (2-(2H-benzotriazol-2-yl)-4,6-di-tert-pentylphenol (UV238), and synthetic phenolic antioxidants (2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol (BHT) and 2,6-di-tert-butyl-1,4-benzoquinone (BHTQ)). The field-based tissue-specific bioaccumulation factors (BAF) were analyzed to assess these contaminants in fish tissues (lake sturgeon and northern pike) in which some of the compounds that accumulated in lake sturgeon were BP3, BHT, and UV238. For northern pike, some were BP, BP3, BHT, and BHTQ, establishing an environmental risk assessment in terms of possible adverse effects on fish [ 57 ].

Finally, in the case of PAHs, several compounds have been detected (fluorene, naphthalene, anthracene, chrysene, and others) in different American countries, such as Canada, United States of America, Ecuador, Peru, Chile, and Brazil [ 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 ]. Their presence has been related to anthropogenic activities, such as aluminum smelter or oil production, having a negative impact on health, such as carcinogenic effects.

For this reason, analytical assays must be performed to establish the concentrations of these pollutants using techniques that are capable of studying a complex matrix and if it is possible, in situ. In Table 2 , the description of several studies that were able to detect organic compounds in environmental samples and the technique that was employed are provided.

Detection of organic pollutants in environmental samples.

As it can be appreciated in Table 2 , a variety of organic compounds have been identified as being associated with several disorders and diseases. Nevertheless, most of the studies analyzed correlated its contaminant of interest with previous research that evaluated its potential human health risk effect. For this reason, it is important to detect the contaminant and correlate it with its health impact in the environment (population and biota).

2.2. Presence of Pollutants in Water: Impact on Human Health and Its Possible Sources

The inorganic contaminants with the greatest presence in water bodies correspond to heavy metals. At the moment, the potential damage to health due to heavy metals has been reported as listed below: As(III) (skin damage, circulatory system issues), Cd(II) (kidney damage, carcinogenic, cardiovascular damage, hematological, and skeletal changes), Cr(III) (allergic dermatitis, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting), Cu(II) (gastrointestinal, liver or kidney damage), Pb(II) (kidney damage, reduced neural development, behavioral disorders), Hg(II) (kidney damage, nervous system).

According to the scientific reports analyzed, it is concluded that there are two main risk factors in public health: (i) the intake of contaminated water, being the main factor due to direct exposure to the contaminant, which can produce different anomalies as those described in the previous paragraph. However, the studies presented cannot be considered conclusive, since the reports show that the impact on health is directly related to the clinical history of the exposed population [ 20 ]. (ii) The consumption of contaminated food, such as in the case of the report of da-Silva et al. (2019) [ 24 ], which reported Hg migration in water from the Western Amazon Basin (Amazon Triple Frontier: Brazil, Peru, and Colombia) to fish; being that if they are intended for human consumption, this can cause mercury intoxication (mercurialism). While the intake of contaminated food is the most likely action to occur, there are other special factors that particularly attract attention, such as the report presented by Oliveira et al. (2021) [ 87 ] studying a potential health risk in terms of a cognitive deficit due to soil intake by pre-school children aged 1 to 4 years, which presents high levels of Pb and Cd due to contact with contaminated wastewater from industries in the region of São Paulo (Brazil).

On the other hand, for organic contaminants, data analysis and comparison has been performed in different countries evidencing the necessity of establishing strategies to remediate water pollution ( Figure 1 ). These strategies are urgent, based on the potential risk that these contaminants can have on human health [ 88 , 89 , 90 ]. Although there are currently certain reports, guidance values or standards that allow establishing criteria based on the presence of these contaminants and their potential toxic effect are needed [ 43 , 91 ]. Efforts have been performed to establish international regulations since the majority of organic compounds are not quality controls [ 92 ].

For this reason, several research groups have tried to determine the impact a chemical compound has on human health. For example, atrazine, an artificial herbicide that was detected in surface water, has been associated with an impact on human health and aquatic biota [ 93 ], upon evaluating endocrine-disrupting compounds that can affect human health via cell-based assays [ 94 ]. Moreover, per and polyfluoroalkyl substances have been determined, but there are no reference points that establish a water quality criterion for its impact on human health [ 91 ]. Based on this, there is a need to establish scientific studies in a human population and evaluate the impact of water pollution on its health. Some studies have been performed (see Table 3 ) to correlate the exposure of contaminants in people’s life and if possible, establish the impact that water sources and body contamination have.

Scientific studies on the correlation between a water source and the presence of certain pollutants in a human population.

2.3. Water Treatment Technologies for the Removal of Contaminants in Water: Status and Perspectives

2.3.1. inorganic contaminants.

Taking into consideration the environmental and public health risk represented by effluents and water bodies contaminated with metals, numerous research groups have focused on proposing remediation alternatives, highlighting the adsorption process [ 104 , 105 ], coagulation/flocculation [ 106 ], chemical precipitation [ 107 ], ion exchange [ 108 ], electrochemical treatments [ 109 , 110 ], membrane use (ultrafiltration, osmosis, and nanofiltration) [ 111 , 112 ], and other alternative treatments based on the use of biopolyelectrolytes and coupled adsorption processes with electrochemical regeneration [ 113 , 114 ]. In all cases, the actual challenge consists of evaluating the scale-up process, for which studies have been performed on a small scale under controlled conditions.

Although, scientific reports have demonstrated great efficiencies in the removal of heavy metals, there has been certain problems documented for each technology, which must be addressed to present advanced remediation technologies. For the ion exchange process, it has been documented that those present with low efficiencies for the removal of high concentrations of metals [ 115 ]. For example, Malik et al. (2019) reported removal efficiencies of 55% for Pb and 30–40% for Hg [ 116 ]. In the case of membrane filtration, good removal efficiencies have been reported (around 90% for Cu and Cd) [ 116 ],;however, it requires high installation costs and maintenance [ 117 ]. Likewise, it has been reported that the electrochemical, catalysis, and coagulation/flocculation processes present high metal removal efficiencies (around 85–99% for Cd, Zn, and Mn) [ 118 ]. On the other hand, the main drawbacks are high installation costs and extra operational costs, as well as the generation of unwanted by-products (sludge) [ 119 ]. These drawbacks significantly reduce the effectiveness of water treatment processes, so a second challenge to deal with is process optimization.

Finally, the third challenge is the design of environmentally and economically sustainable treatment processes. The current paradigm of water treatment of metal contamination must be broken; the importance is not only in water sanitation, but also in recovering the metal in order to obtain valuable products and not only change the pollutant phase [ 120 ]. For all the above, adsorption and chemical precipitation have turned out to be the most used methods. However, the removal results obtained depend on each matrix used, so the materials and experimental conditions must be proposed based on the needs and the type of effluent to be treated [ 121 ].

2.3.2. Organic Contaminants

In the previous sections, the detection of these pollutants is only the first step to evaluate the environmental risk that communities and countries have in their respective water sources. The next step is to determine technologies that can establish an efficiency in the removal of these contaminants in a complex matrix without affecting the environment using novel systems [ 122 , 123 , 124 ]. In this regard, an actual challenge is the development of technologies capable of treating specific organic compounds and if it is possible, to use these treatment technologies with the current systems that governments have implemented. Some technologies that have been investigated are the use of continuous flow supercritical water (SCW) for the removal of hormones from the wastewater of a pharmaceutical industry. In their results, the technology was demonstrated to reduce 88.4% of the initial total organic carbon (TOC) value, and the presence in gas phase of H 2 , CH 4 , CO, CO 2 , C 2 H 6 , and C 2 H 4 , which could be used to produce renewable energy. Moreover, phytotoxicity assays demonstrated that there was no risk of the treated samples with respect to the germination of Cucumis sativus seeds [ 125 ]. Another technology that has been used is direct contact membrane distillation, which can be used to treat raw surface water contaminated with phenolic compounds [ 126 ]. In this case, water samples were spiked with 15 phenolic compounds. An important parameter evaluated was the recovery rate (RR) to demonstrate the stability of the direct membrane distillation, being up to a 30%. Pollutant removal reached 94.3 ± 1.9% and 95.0 ± 2.2% for 30% and 70% RR, respectively. A consideration for this technology is to work at a recovery rate in which flux does not decay (RR < 30%) to avoid performing loss and fouling.

Different approaches have been used for the removal of contaminants, such as the use of a photocatalytic paint based on TiO 2 nanoparticles and acrylate-based photopolymer resin for the removal of dyes in different water matrices [ 127 ]. Another strategy was subsurface horizontal flow-constructed wetlands (planted in polyculture and unplanted) as secondary domestic wastewater treatment to demonstrate the removal of personal care and pharmaceutical products [ 128 ].

Considering the above mentioned content, among all technologies evaluated currently to eliminate organic contaminants present in water, Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) stand out, since they generate highly reactive and non-selective radicals capable of almost completely mineralizing the contaminant of interest, generating mainly CO 2 and H 2 O as an oxidation product. In this sense, the most widely studied AOPs correspond to catalytic wet peroxide oxidation, catalytic wet air oxidation, homogeneous catalyst, photo-Fenton, Fenton process, photocatalysis, Fenton-like, electro-Fenton, heterogeneous catalyst, ultrasound, and microwave [ 129 ]. Although the results show the potential use of technologies for water treatment, there are still challenges to address. The current challenge of this technology must be aimed at scaling the process, optimizing operational parameters, and designing a sustainable technology to have a low cost and be environmentally friendly, achieving the lowest generation of by-products. In this sense, two recently published research articles stand out in which AOPs have been evaluated for the treatment of contaminated water effluents in the Latin American region. Mejía-Morales et al. (2020) [ 130 ] presented the use of an AOP based on UV/H 2 O 2 /O 3 for the remediation of residual water from a hospital in Puebla (Mexico), showing the feasibility of its use to remediate effluents contaminated with a high organic load. On the other hand, Zárate-Guzmán et al. (2021) [ 131 ] presented the scale-up of a Fenton and Photo-Fenton process for the treatment of piggery wastewater in Guanajuato (Mexico). The results show that these two AOPs have great application potential for the remediation of effluents contaminated with a high organic load due to their high removal percentages (COD, TOC, and Color) and low operating costs.

3. Conclusions

The presence of contaminants in the water is a severe environmental and public health problem in the American continent. The presence of inorganic (As, Cd, Cr, Pb, Cu, Hg, and U) and organic pollutants (dyes, phenolic compounds, hormones, pesticides, and pharmaceuticals compounds) in effluents and water bodies is due to anthropogenic activities and natural factors in the region. The health risks associated with these contaminants primarily encompass skin damage, carcinogenic effects, nervous system damage, circulatory system issues, kidney damage, gastrointestinal damage, and impacts on the food chain. The critical review of the reports presented in this document identifies the following as the main challenges:

- (i) Implement advanced analytical detection techniques, such as those based on electrochemical tests, to achieve improvements in detection limits, low operating costs, short analysis times, and mobility to perform in situ determinations.

- (ii) Accurately determine the source of contamination in each geographic site of interest to propose containment and sanitation actions to solve the problem.

- (iii) Evaluate water treatment technologies on a large scale and under real conditions to optimize the treatment processes.

- (iv) Design and/or conditioning of specific water treatment plants according to the pollutant of interest in the region. The universal design paradigm of a water treatment plant must be broken; the pertinent modifications must be made according to the needs of the population of interest.

- (v) Design environmentally and economically sustainable treatment processes. Future water treatment processes will need to integrate circular economy concepts to obtain high-quality water and valuable products, such as precious metals, and/or produce biofuels.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the “Secretaria de Innovación, Ciencia y tecnología (SICyT)” and “Consejo Estatal de Ciencia y Tecnología de Jalisco (COECYTJAL)” for the support received through the Convocatoria del fondo de Desarrollo Científico de Jalisco para Atender Retos Sociales “FODECIJAL 2022” (Clave del Proyecto: 10169-2022).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph20054499/s1 , Supplementary Table S1: Comparative table of analytical techniques most used for the detection of inorganic contaminants present in water. Supplementary Table S2: Comparison of detection limits in μg L −1 at 3 sigma [ 132 ].

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.I.Z.-G. and L.A.R.-C.; Methodology, all authors; Formal analysis, all authors; writing—original draft preparation, all authors; writing—review and editing, all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

Effects of Water Pollution: Causes, Consequences, & Solutions on Environment

- June 10, 2023

- Environment

Water pollution is a global environmental issue that affects the quality of our water bodies, threatening aquatic ecosystems and human health. This article explores the causes, consequences, and potential solutions to combat water pollution. By understanding the gravity of this problem, we can take necessary actions to protect and preserve our water resources for future generations.

Causes of Water Pollution:

- Industrial Discharges: Industrial activities often release harmful chemicals and pollutants into nearby water bodies, contaminating the water and endangering aquatic life.

- Agricultural Runoff: Excessive use of fertilizers and pesticides in agriculture results in runoff, carrying these pollutants into rivers and lakes, leading to eutrophication and the death of aquatic organisms.

- Sewage and Wastewater: Inadequate sewage treatment systems allow untreated or poorly treated wastewater to flow into water sources, introducing disease-causing bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens.

- Oil Spills: Accidental oil spills from shipping, offshore drilling, or transportation accidents have catastrophic effects on marine life, as oil coats and suffocates animals and birds, disrupting the entire ecosystem .

Consequences of Water Pollution:

- Threat to Aquatic Ecosystems: Water pollution disrupts the delicate balance of aquatic ecosystems by depleting oxygen levels, destroying habitats, and reducing biodiversity . This, in turn, affects fish populations and other aquatic organisms, leading to ecosystem collapse.

- Human Health Impacts: Contaminated water is a major source of waterborne diseases such as cholera, dysentery, and hepatitis. Additionally, long-term exposure to polluted water can lead to various health problems, including cancer, developmental disorders, and reproductive issues.

- Economic Toll: Water pollution has significant economic implications, including the decline of fisheries, tourism, and recreational activities. Cleaning up polluted water sources and providing clean water to affected communities also incur substantial costs.

Key Consequences in Detail:

- Eutrophication: Excessive nutrient runoff, mainly nitrogen and phosphorus, leads to eutrophication, causing algal blooms and depleting oxygen levels. This creates dead zones where marine life cannot survive.

- Bioaccumulation: Pollutants such as heavy metals and pesticides enter the food chain and accumulate in the tissues of aquatic organisms. As larger predators consume smaller ones, these pollutants become concentrated, posing risks to human health when consumed.

- Destruction of Coral Reefs: Water pollution, combined with factors like ocean acidification and rising temperatures, contributes to coral reef degradation. Coral reefs support a diverse range of marine life and act as natural barriers against coastal erosion.

- Disruption of the Water Cycle: Polluted water can interfere with the natural water cycle, affecting precipitation patterns, groundwater quality, and overall water availability in a region.

Solutions to Water Pollution:

- Enhanced Regulations: Governments should enforce stricter regulations on industrial and agricultural practices, ensuring proper waste management and reducing the release of pollutants into water bodies.

- Improved Sewage Treatment: Investing in modern wastewater treatment facilities and infrastructure can effectively treat and purify sewage before it is released back into the environment .

- Sustainable Agriculture: Promoting sustainable farming practices, such as organic farming and precision irrigation, can reduce the use of harmful chemicals and minimize agricultural runoff.

- Public Awareness and Education: Raising awareness about the importance of water conservation, pollution prevention, and responsible water usage is crucial in fostering a sense of environmental responsibility among individuals and communities.

Key Takeaways:

Water pollution poses a severe threat to our environment, economy, and public health. By understanding the causes, consequences, and solutions to combat water pollution, we can work together to protect and restore our precious water resources. Implementing stricter regulations, improving wastewater treatment, adopting sustainable agricultural practices, and promoting public awareness are essential steps towards achieving clean and healthy water bodies worldwide. Let us act now to ensure a sustainable future for ourselves and the generations to come.

FAQs about Effects of Water Pollution

Q: what is water pollution.

A: Water pollution refers to the contamination of water bodies such as rivers, lakes, oceans, and groundwater with harmful substances, chemicals, or pollutants, making the water unsafe for use and threatening aquatic ecosystems.

Q: What are the main causes of water pollution?

A: Water pollution can be caused by various factors, including industrial discharges, agricultural runoff, sewage and wastewater, oil spills, and improper waste disposal.

Q: How does water pollution affect the environment?

A: Water pollution has detrimental effects on the environment. It can lead to the loss of aquatic biodiversity, destruction of habitats, disruption of ecosystems, and the formation of dead zones where marine life cannot survive.

Q: How does water pollution impact human health?

A: Water pollution can have severe consequences for human health. Consuming contaminated water can lead to waterborne diseases such as cholera, dysentery, and hepatitis. Long-term exposure to polluted water can also result in various health problems, including cancer, developmental disorders, and reproductive issues.

Q: What are the economic impacts of water pollution?

A: Water pollution has significant economic implications. It can lead to the decline of fisheries, loss of tourism revenue, and increased costs for cleaning up polluted water sources. Providing clean water to affected communities and treating waterborne diseases also incur substantial financial burdens.

Q: How can we prevent water pollution?

A: Preventing water pollution requires collective efforts. Some key solutions include enforcing stricter regulations on industrial and agricultural practices, improving sewage treatment systems, promoting sustainable farming methods, and raising public awareness about water conservation and pollution prevention.

Share this:

How 5 Cities Shape Sustainable Urban Futures? Passive Cooling Revolution

- December 18, 2023

- Global Warming

What Is The Impact of Rising Sea Levels on The Pacific Island?

- December 13, 2023

Ground Water Vulnerability Assessment: Predicting Relative Contamination Potential Under Conditions of Uncertainty (1993)

Chapter: 5 case studies, 5 case studies, introduction.

This chapter presents six case studies of uses of different methods to assess ground water vulnerability to contamination. These case examples demonstrate the wide range of applications for which ground water vulnerability assessments are being conducted in the United States. While each application presented here is directed toward the broad goal of protecting ground water, each is unique in its particular management requirements. The intended use of the assessment, the types of data available, the scale of the assessments, the required resolution, the physical setting, and institutional factors all led to very different vulnerability assessment approaches. In only one of the cases presented here, Hawaii, are attempts made to quantify the uncertainty associated with the assessment results.

Introduction

Ground water contamination became an important political and environmental issue in Iowa in the mid-1980s. Research reports, news headlines, and public debates noted the increasing incidence of contaminants in rural and urban well waters. The Iowa Ground water Protection Strategy (Hoyer et al. 1987) indicated that levels of nitrate in both private and municipal

wells were increasing. More than 25 percent of the state's population was served by water with concentrations of nitrate above 22 milligrams per liter (as NO 3 ). Similar increases were noted in detections of pesticides in public water supplies; about 27 percent of the population was periodically consuming low concentrations of pesticides in their drinking water. The situation in private wells which tend to be shallower than public wells may have been even worse.

Defining the Question

Most prominent among the sources of ground water contamination were fertilizers and pesticides used in agriculture. Other sources included urban use of lawn chemicals, industrial discharges, and landfills. The pathways of ground water contamination were disputed. Some interests argued that contamination occurs only when a natural or human generated condition, such as sinkholes or agricultural drainage wells, provides preferential flow to underground aquifers, resulting in local contamination. Others suggested that chemicals applied routinely to large areas infiltrate through the vadose zone, leading to widespread aquifer contamination.

Mandate, Selection, and Implementation

In response to growing public concern, the state legislature passed the Iowa Ground water Protection Act in 1987. This landmark statute established the policy that further contamination should be prevented to the "maximum extent practical" and directed state agencies to launch multiyear programs of research and education to characterize the problem and identify potential solutions.

The act mandated that the Iowa Department of Natural Resources (DNR) assess the vulnerability of the state's ground water resources to contamination. In 1991, DNR released Ground water Vulnerability Regions of Iowa , a map developed specifically to depict the intrinsic susceptibility of ground water resources to contamination by surface or near-surface activities. This assessment had three very limited purposes: (1) to describe the physical setting of ground water resources in the state, (2) to educate policy makers and the public about the potential for ground water contamination, and (3) to provide guidance for planning and assigning priorities to ground water protection efforts in the state.

Unlike other vulnerability assessments, the one in Iowa took account of factors that affect both ground water recharge and well development. Ground water recharge involves issues related to aquifer contamination; well development involves issues related to contamination of water supplies in areas where sources other than bedrock aquifers are used for drinking water. This

approach considers jointly the potential impacts of contamination on the water resource in aquifers and on the users of ground water sources.

The basic principle of the Iowa vulnerability assessment involves the travel time of water from the land surface to a well or an aquifer. When the time is relatively short (days to decades), vulnerability is considered high. If recharge occurs over relatively long periods (centuries to millennia), vulnerability is low. Travel times were determined by evaluating existing contaminants and using various radiometric dating techniques. The large reliance on travel time in the Iowa assessment likely results in underestimation of the potential for eventual contamination of the aquifer over time.

The most important factor used in the assessment was thickness of overlying materials which provide natural protection to a well or an aquifer. Other factors considered included type of aquifer, natural water quality in an aquifer, patterns of well location and construction, and documented occurrences of well contamination. The resulting vulnerability map ( Plate 1 ) delineates regions having similar combinations of physical characteristics that affect ground water recharge and well development. Qualitative ratings are assigned to the contamination potential for aquifers and wells for various types and locations of water sources. For example, the contamination potential for wells in alluvial aquifers is considered high, while the potential for contamination of a variable bedrock aquifer protected by moderate drift or shale is considered low.

Although more sophisticated approaches were investigated for use in the assessment, ultimately no complex process models of contaminant transport were used and no distinction was made among Iowa's different soil types. The DNR staff suggested that since the soil cover in most of the state is such a small part of the overall aquifer or well cover, processes that take place in those first few inches are relatively similar and, therefore, insignificant in terms of relative susceptibilities to ground water contamination. The results of the vulnerability assessment followed directly from the method's assumptions and underlying principles. In general, the thicker the overlay of clayey glacial drift or shale, the less susceptible are wells or aquifers to contamination. Where overlying materials are thin or sandy, aquifer and well susceptibilities increase. Vulnerability is also greater in areas where sinkholes or agricultural drainage wells allow surface and tile water to bypass natural protective layers of soil and rapidly recharge bedrock aquifers.

Basic data on geologic patterns in the state were extrapolated to determine the potential for contamination. These data were supplemented by databases on water contamination (including the Statewide Rural Well-Water Survey conducted in 1989-1990) and by research insights into the transport, distribution, and fate of contaminants in ground water. Some of the simplest data needed for the assessment were unavailable. Depth-to-bedrock information had never been developed, so surface and bedrock topographic

maps were revised and integrated to create a new statewide depth-to-bedrock map. In addition, information from throughout the state was compiled to produce the first statewide alluvial aquifer map. All new maps were checked against available well-log data, topographic maps, outcrop records, and soil survey reports to assure the greatest confidence in this information.

While the DNR was working on the assessment, it was also asked to integrate various types of natural resource data into a new computerized geographic information system (GIS). This coincident activity became a significant contributor to the assessment project. The GIS permitted easier construction of the vulnerability map and clearer display of spatial information. Further, counties or regions in the state can use the DNR geographic data and the GIS to explore additional vulnerability parameters and examine particular areas more closely to the extent that the resolution of the data permits.

The Iowa vulnerability map was designed to provide general guidance in planning and ranking activities for preventing contamination of aquifers and wells. It is not intended to answer site-specific questions, cannot predict contaminant concentrations, and does not even rank the different areas of the state by risk of contamination. Each of these additional uses would require specific assessments of vulnerability to different activities, contaminants, and risk. The map is simply a way to communicate qualitative susceptibility to contamination from the surface, based on the depth and type of cover, natural quality of the aquifer, well location and construction, and presence of special features that may alter the transport of contaminants.

Iowa's vulnerability map is viewed as an intermediate product in an ongoing process of learning more about the natural ground water system and the effects of surface and near-surface activities on that system. New maps will contain some of the basic data generated by the vulnerability study. New research and data collection will aim to identify ground water sources not included in the analysis (e.g., buried channel aquifers and the "salt and pepper sands" of western Iowa). Further analyses of existing and new well water quality data will be used to clarify relationships between aquifer depth and ground water contamination. As new information is obtained, databases and the GIS will be updated. Over time, new vulnerability maps may be produced to reflect new data or improved knowledge of environmental processes.

The Cape Cod sand and gravel aquifer is the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) designated sole source of drinking water for Barnstable County, Massachusetts (ca. 400 square miles, winter population 186,605 in 1990, summer population ca. 500,000) as well as the source of fresh water for numerous kettle hole ponds and marine embayments. During the past 20 years, a period of intense development of open land accompanied by well-reported ground water contamination incidents, Cape Cod has been the site of intensive efforts in ground water management and analysis by many organizations, including the Association for the Preservation of Cape Cod, the U.S. Geological Survey, the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (formerly the Department of Environmental Quality Engineering), EPA, and the Cape Cod Commission (formerly the Cape Cod Planning and Economic Development Commission). An earlier NRC publication, Ground Water Quality Protection: State and Local Strategies (1986) summarizes the Cape Cod ground water protection program.

The Area Wide Water Quality Management Plan for Cape Cod (CCPEDC 1978a, b), prepared in response to section 208 of the federal Clean Water Act, established a management strategy for the Cape Cod aquifer. The plan emphasized wellhead protection of public water supplies, limited use of public sewage collection systems and treatment facilities, and continued general reliance on on-site septic systems, and relied on density controls for regulation of nitrate concentrations in public drinking water supplies. The water quality management planning program began an effort to delineate the zones of contribution (often called contributing areas) for public wells on Cape Cod that has become increasingly sophisticated over the years. The effort has grown to address a range of ground water resources and ground water dependent resources beyond the wellhead protection area, including fresh and marine surface waters, impaired areas, and water quality improvement areas (CCC 1991). Plate 2 depicts the water resources classifications for Cape Cod.

Selection and Implementation of Approaches

The first effort to delineate the contributing area to a public water supply well on Cape Cod came in 1976 as part of the initial background studies for the Draft Area Wide Water Quality Management Plan for Cape

Cod (CCPEDC 1978a). This effort used a simple mass balance ratio of a well's pumping volume to an equal volume average annual recharge evenly spread over a circular area. This approach, which neglects any hydrogeologic characteristics of the aquifer, results in a number of circles of varying radii that are centered at the wells.

The most significant milestone in advancing aquifer protection was the completion of a regional, 10 foot contour interval, water table map of the county by the USGS (LeBlanc and Guswa 1977). By the time that the Draft and Final Area Wide Water Quality Management Plans were published (CCPEDC 1978a, b), an updated method for delineating zones of contribution, using the regional water table map, had been developed. This method used the same mass balance approach to characterize a circle, but also extended the zone area by 150 percent of the circle's radius in the upgradient direction. In addition, a water quality watch area extending upgradient from the zone to the ground water divide was recommended. Although this approach used the regional water table map for information on ground water flow direction, it still neglected the aquifer's hydrogeologic parameters.

In 1981, the USGS published a digital model of the aquifer that included regional estimates of transmissivity (Guswa and LeBlanc 1981). In 1982, the CCPEDC used a simple analytical hydraulic model to describe downgradient and lateral capture limits of a well in a uniform flow field (Horsley 1983). The input parameters required for this model included hydraulic gradient data from the regional water table map and transmissivity data from the USGS digital model. The downgradient and lateral control points were determined using this method, but the area of the zone was again determined by the mass balance method. Use of the combined hydraulic and mass balance method resulted in elliptical zones of contribution that did not extend upgradient to the ground water divide. This combined approach attempted to address three-dimensional ground water flow beneath a partially penetrating pumping well in a simple manner.

At about the same time, the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection started the Aquifer Lands Acquisition (ALA) Program to protect land within zones of contribution that would be delineated by detailed site-specific studies. Because simple models could not address three-dimensional flow and for several other reasons, the ALA program adopted a policy that wellhead protection areas or Zone IIs (DEP-WS 1991) should be extended upgradient all the way to a ground water divide. Under this program, wells would be pump tested for site-specific aquifer parameters and more detailed water table mapping would often be required. In many cases, the capture area has been delineated by the same simple hydraulic analytical model but the zone has been extended to the divide. This method has resulted in some 1989 zones that are 3,000 feet wide and extend 4.5

miles upgradient, still without a satisfactory representation of three-dimensional flow to the well.

Most recently the USGS (Barlow 1993) has completed a detailed subregional, particle-tracking three-dimensional ground water flow model that shows the complex nature of ground water flow to wells. This approach has shown that earlier methods, in general, overestimate the area of zones of contribution (see Figure 5.1 ).

In 1988, the public agencies named above completed the Cape Cod Aquifer Management Project (CCAMP), a resource-based ground water protection study that used two towns, Barnstable and Eastham, to represent the more and less urbanized parts of Cape Cod. Among the CCAMP products were a GIS-based assessment of potential for contamination as a result of permissible land use changes in the Barnstable zones of contribution (Olimpio et al. 1991) and a ground water vulnerability assessment by Heath (1988) using DRASTIC for the same area. Olimpio et al. characterized land uses by ranking potential contaminant sources without regard to differences in vulnerability within the zones. Heath's DRASTIC analysis of the same area, shown in Figure 5.2 , delineated two distinct zones of vulnerability based on hydrogeologic setting. The Sandwich Moraine setting, with deposits of silt, sand and gravel, and depths to ground water ranging from 0 to more than 125 feet, had DRASTIC values of 140 to 185; the Barnstable Outwash Plain, with permeable sand and fine gravel deposits with beds of silt and clay and depths to ground water of less than 50 feet, yielded values of 185 to 210. The DRASTIC scores and relative contributions of the factors are shown in Tables 5.1 and 5.2 . Heath concluded that similar areas of Cape Cod would produce similar moderate to high vulnerability DRASTIC scores. The CCAMP project also addressed the potential for contamination of public water supply wells from new land uses allowable under existing zoning for the same area. The results of that effort are shown in Plate 4 .

In summary, circle zones were used initially when the hydrogeologic nature of the aquifer or of hydraulic flow to wells was little understood. The zones improved with an understanding of ground water flow and aquifer characteristics, but in recognition of the limitations of regional data, grossly conservative assumptions came into use. Currently, a truer delineation of a zone of contribution can be prepared for a given scenario using sophisticated models and highly detailed aquifer characterization. However, the area of a given zone still is highly dependent on the initial assumptions that dictate how much and in what circumstances a well is pumped. In the absence of ability to specify such conditions, conservative assumptions,

FIGURE 5.1 Contributing areas of wells and ponds in the complex flow system determined by using the three-dimensional model with 1987 average daily pumping rates. (Barlow 1993)

such as maximum prolonged pumping, prevail, and, therefore, conservatively large zones of contribution continue to be used for wellhead protection.

The ground water management experience of Cape Cod has resulted in a better understanding of the resource and the complexity of the aquifer

FIGURE 5.2 DRASTIC contours for Zone 1, Barnstable-Yarmouth, Massachusetts.

system, as well as the development of a more ambitious agenda for resource protection. Beginning with goals of protection of existing public water supplies, management interests have grown to include the protection of private wells, potential public supplies, fresh water ponds, and marine embayments. Public concerns over ground water quality have remained high and were a major factor in the creation of the Cape Cod Commission by the Massachusetts legislature. The commission is a land use planning and regulatory agency with broad authority over development projects and the ability to create special resource management areas. The net result of 20 years of effort by many individuals and agencies is the application of

TABLE 5.1 Ranges, Rating, and Weights for DRASTIC Study of Barnstable Outwash Plain Setting (NOTE: gpd/ft 2 = gallons per day per square foot) (Heath 1988)

TABLE 5.2 Ranges, Rating, and Weights for DRASTIC Study of Sandwich Moraine Setting (NOTE: gpd/ft 2 = gallons per day per square foot) (Heath 1988)

higher protection standards to broader areas of the Cape Cod aquifer. With some exceptions for already impaired areas, a differentiated resource protection approach in the vulnerable aquifer setting of Cape Cod has resulted in a program that approaches universal ground water protection.

Florida has 13 million residents and is the fourth most populous state (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1991). Like several other sunbelt states, Florida's population is growing steadily, at about 1,000 persons per day, and is estimated to reach 17 million by the year 2000. Tourism is the biggest industry in Florida, attracting nearly 40 million visitors each year. Ground water is the source of drinking water for about 95 percent of Florida's population; total withdrawals amount to about 1.5 billion gallons per day. An additional 3 billion gallons of ground water per day are pumped to meet the needs of agriculture—a $5 billion per year industry, second only to tourism in the state. Of the 50 states, Florida ranks eighth in withdrawal of fresh ground water for all purposes, second for public supply, first for rural domestic and livestock use, third for industrial/commercial use, and ninth for irrigation withdrawals.

Most areas in Florida have abundant ground water of good quality, but the major aquifers are vulnerable to contamination from a variety of land use activities. Overpumping of ground water to meet the growing demands of the urban centers, which accounts for about 80 percent of the state's population, contributes to salt water intrusion in coastal areas. This overpumping is considered the most significant problem for degradation of ground water quality in the state. Other major sources of ground water contaminants include: (1) pesticides and fertilizers (about 2 million tons/year) used in agriculture, (2) about 2 million on-site septic tanks, (3) more than 20,000 recharge wells used for disposing of stormwater, treated domestic wastewater, and cooling water, (4) nearly 6,000 surface impoundments, averaging one per 30 square kilometers, and (5) phosphate mining activities that are estimated to disturb about 3,000 hectares each year.

The Hydrogeologic Setting

The entire state is in the Coastal Plain physiographic province, which has generally low relief. Much of the state is underlain by the Floridan aquifer system, largely a limestone and dolomite aquifer that is found in both confined and unconfined conditions. The Floridan is overlain through most of the state by an intermediate aquifer system, consisting of predominantly clays and sands, and a surficial aquifer system, consisting of predominantly sands, limestone, and dolomite. The Floridan is one of the most productive aquifers in the world and is the most important source of drinking water for Florida residents. The Biscayne, an unconfined, shallow, limestone aquifer located in southeast Florida, is the most intensively used

aquifer and the sole source of drinking water for nearly 3 million residents in the Miami-Palm Beach coastal area. Other surficial aquifers in southern Florida and in the western panhandle region also serve as sources of ground water.

Aquifers in Florida are overlain by layers of sand, clay, marl, and limestone whose thickness may vary considerably. For example, the thickness of layers above the Floridan aquifer range from a few meters in parts of west-central and northern Florida to several hundred meters in south-central Florida and in the extreme western panhandle of the state. Four major groups of soils (designated as soil orders under the U.S. Soil Taxonomy) occur extensively in Florida. Soils in the western highlands are dominated by well-drained sandy and loamy soils and by sandy soils with loamy subsoils; these are classified as Ultisols and Entisols. In the central ridge of the Florida peninsula, are found deep, well-drained, sandy soils (Entisols) as well as sandy soils underlain by loamy subsoils or phosphatic limestone (Alfisols and Ultisols). Poorly drained sandy soils with organic-rich and clay-rich subsoils, classified as Spodosols, occur in the Florida flatwoods. Organic-rich muck soils (Histosols) underlain by muck or limestone are found primarily in an area extending south of Lake Okeechobee.

Rainfall is the primary source of ground water in Florida. Annual rainfall in the state ranges from 100 to 160 cm/year, averaging 125 cm/year, with considerable spatial (both local and regional) and seasonal variations in rainfall amounts and patterns. Evapotranspiration (ET) represents the largest loss of water; ET ranges from about 70 to 130 cm/year, accounting for between 50 and 100 percent of the average annual rainfall. Surface runoff and ground water discharge to streams averages about 30 cm/year. Annual recharge to surficial aquifers ranges from near zero in perennially wet, lowland areas to as much as 50 cm/year in well-drained areas; however, only a fraction of this water recharges the underlying Floridan aquifer. Estimates of recharge to the Floridan aquifer vary from less than 3 cm/year to more than 25 cm/year, depending on such factors as weather patterns (e.g., rainfall-ET balance), depth to water table, soil permeability, land use, and local hydrogeology.

Permeable soils, high net recharge rates, intensively managed irrigated agriculture, and growing demands from urban population centers all pose considerable threat of ground water contamination. Thus, protection of this valuable natural resource while not placing unreasonable constraints on agricultural production and urban development is the central focus of environmental regulation and growth management in Florida.

Along with California, Florida has played a leading role in the United

States in development and enforcement of state regulations for environmental protection. Detection in 1983 of aldicarb and ethylene dibromide, two nematocides used widely in Florida's citrus groves, crystallized the growing concerns over ground water contamination and the need to protect this vital natural resource. In 1983, the Florida legislature passed the Water Quality Assurance Act, and in 1984 adopted the State and Regional Planning Act. These and subsequent legislative actions provide the legal basis and guidance for the Ground Water Strategy developed by the Florida Department of Environmental Regulation (DER).

Ground water protection programs in Florida are implemented at federal, state, regional, and local levels and involve both regulatory and nonregulatory approaches. The most significant nonregulatory effort involves more than 30 ground water studies being conducted in collaboration with the Water Resources Division of the U.S. Geological Survey. At the state level, Florida statutes and administrative codes form the basis for regulatory actions. Although DER is the primary agency responsible for rules and statutes designed to protect ground water, the following state agencies participate to varying degrees in their implementation: five water management districts, the Florida Geological Survey, the Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services (HRS), the Department of Natural Resources, and the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (DACS). In addition, certain interagency committees help coordinate the development and implementation of environmental codes in the state. A prominent example is the Pesticide Review Council which offers guidance to the DACS in developing pesticide use regulation. A method for screening pesticides in terms of their chronic toxicity and environmental behavior has been developed through collaborative efforts of the DACS, the DER, and the HRS (Britt et al. 1992). This method will be used to grant registration for pesticide use in Florida or to seek additional site-specific field data.

Selecting an Approach

The emphasis of the DER ground water program has shifted in recent years from primarily enforcement activity to a technically based, quantifiable, planned approach for resource protection.

The administrative philosophy for ground water protection programs in Florida is guided by the following principles:

Ground water is a renewable resource, necessitating a balance between withdrawals and natural or artificial recharge.

Ground water contamination should be prevented to the maximum degree possible because cleanup of contaminated aquifers is technically or economically infeasible.

It is impractical, perhaps unnecessary, to require nondegradation standards for all ground water in all locations and at all times.

The principle of ''most beneficial use" is to be used in classifying ground water into four classes on the basis of present quality, with the goal of attaining the highest level protection of potable water supplies (Class I aquifers).

Part of the 1983 Water Quality Assurance Act requires Florida DER to "establish a ground water quality monitoring network designed to detect and predict contamination of the State's ground water resources" via collaborative efforts with other state and federal agencies. The three basic goals of the ground water quality monitoring program are to:

Establish the baseline water quality of major aquifer systems in the state,

Detect and predict changes in ground water quality resulting from the effects of various land use activities and potential sources of contamination, and

Disseminate to local governments and the public, water quality data generated by the network.

The ground water monitoring network established by DER to meet the goals stated above consists of two major subnetworks and one survey (Maddox and Spicola 1991). Approximately 1,700 wells that tap all major potable aquifers in the state form the Background Network, which was designed to help define the background water quality. The Very Intensively Studied Area (VISA) network was established to monitor specific areas of the state considered highly vulnerable to contamination; predominant land use and hydrogeology were the primary attributes used to evaluate vulnerability. The DRASTIC index, developed by EPA, served as the basis for statewide maps depicting ground water vulnerability. Data from the VISA wells will be compared to like parameters sampled from Background Network wells in the same aquifer segment. The final element of the monitoring network is the Private Well Survey, in which up to 70 private wells per county will be sampled. The sampling frequency and chemical parameters to be monitored at each site are based on several factors, including network well classification, land use activities, hydrogeologic sensitivity, and funding. In Figure 5.3 , the principal aquifers in Florida are shown along with the distribution of the locations of the monitoring wells in the Florida DER network.

The Preservation 2000 Act, enacted in 1990, mandated that the Land Acquisition Advisory Council (LAAC) "provide for assessing the importance

FIGURE 5.3 Principal aquifers in Florida and the network of sample wells as of March 1990 (1642 wells sampled). (Adapted from Maddox and Spicola 1991, and Maddox et al. 1993.)

of acquiring lands which can serve to protect or recharge ground water, and the degree to which state land acquisition programs should focus on purchasing such land." The Ground Water Resources Committee, a subcommittee of the LAAC, produced a map depicting areas of ground water significance at regional scale (1:500,000) (see Figure 5.4 ) to give decision makers the basis for considering ground water as a factor in land acquisition under the Preservation 2000 Act (LAAC 1991). In developing maps for their districts, each of the five water management districts (WMDs) used the following criteria: ground water recharge, ground water quality, aquifer vulnerability, ground water availability, influence of existing uses on the resource, and ground water supply. The specific approaches used by

FIGURE 5.4 General areas of ground water significance in Florida. (Map provided by Florida Department of Environmental Regulation, Bureau of Drinking Water and Ground Water Resources.)

the WMDs varied, however. For example, the St. Johns River WMD used a GIS-based map overlay and DRASTIC-like numerical index approach that rated the following attributes: recharge, transmissivity, water quality, thickness of potable water, potential water expansion areas, and spring flow capture zones. The Southwest Florida WMD also used a map overlay and index approach which considered four criteria, and GIS tools for mapping. Existing databases were considered inadequate to generate a DRASTIC map for the Suwannee River WMD, but the map produced using an overlay approach was considered to be similar to DRASTIC maps in providing a general depiction of aquifer vulnerability.

In the November 1988, Florida voters approved an amendment to the Florida Constitution allowing land producing high recharge to Florida's aquifers to be classified and assessed for ad valorem tax purposes based on character or use. Such recharge areas are expected to be located primarily in the upland, sandy ridge areas. The Bluebelt Commission appointed by the 1989 Florida Legislature, studied the complex issues involved and recommended that the tax incentive be offered to owners of such high recharge areas if their land is left undeveloped (SFWMD 1991). The land eligible

for classification as "high water recharge land" must meet the following criteria established by the commission:

The parcel must be located in the high recharge areas designated on maps supplied by each of the five WMDs.

The high recharge area of the parcel must be at least 10 acres.

The land use must be vacant or single-family residential.

The parcel must not be receiving any other special assessment, such as Greenbelt classification for agricultural lands.

Two bills related to the implementation of the Bluebelt program are being considered by the 1993 Florida legislation.

THE SAN JOAQUIN VALLEY

Pesticide contamination of ground water resources is a serious concern in California's San Joaquin Valley (SJV). Contamination of the area's aquifer system has resulted from a combination of natural geologic conditions and human intervention in exploiting the SJV's natural resources. The SJV is now the principal target of extensive ground water monitoring activities in the state.

Agriculture has imposed major environmental stresses on the SJV. Natural wetlands have been drained and the land reclaimed for agricultural purposes. Canal systems convey water from the northern, wetter parts of the state to the south, where it is used for irrigation and reclamation projects. Tens of thousands of wells tap the sole source aquifer system to supply water for domestic consumption and crop irrigation. Cities and towns have sprouted throughout the region and supply the human resources necessary to support the agriculture and petroleum industries.

Agriculture is the principal industry in California. With 1989 cash receipts of more than $17.6 billion, the state's agricultural industry produced more than 50 percent of the nation's fruits, nuts, and vegetables on 3 percent of the nation's farmland. California agriculture is a diversified industry that produces more than 250 crop and livestock commodities, most of which can be found in the SJV.

Fresno County, the largest agricultural county in the state, is situated in the heart of the SJV, between the San Joaquin River to the north and the Kings River on the south. Grapes, stone fruits, and citrus are important commodities in the region. These and many other commodities important to the region are susceptible to nematodes which thrive in the county's coarse-textured soils.

While agricultural diversity is a sound economic practice, it stimulates the growth of a broad range of pest complexes, which in turn dictates greater reliance on agricultural chemicals to minimize crop losses to pests, and maintain productivity and profit. Domestic and foreign markets demand high-quality and cosmetically appealing produce, which require pesticide use strategies that rely on pest exclusion and eradication rather than pest management.

Hydrogeologic Setting

The San Joaquin Valley (SJV) is at the southern end of California's Central Valley. With its northern boundary just south of Sacramento, the Valley extends in a southeasterly direction about 400 kilometers (250 miles) into Kern County. The SJV averages 100 kilometers (60 miles) in width and drains the area between the Sierra Nevada on the east and the California Coastal Range on the west. The rain shadow caused by the Coastal Range results in the predominantly xeric habitat covering the greater part of the valley floor where the annual rainfall is about 25 centimeters (10 inches). The San Joaquin River is the principal waterway that drains the SJV northward into the Sacramento Delta region.

The soils of the SJV vary significantly. On the west side of the valley, soils are composed largely of sedimentary materials derived from the Coastal Range; they are generally fine-textured and slow to drain. The arable soils of the east side developed on relatively unweathered, granitic sediments. Many of these soils are wind-deposited sands underlain by deep coarse-textured alluvial materials.

From the mid-1950s until 1977, dibromochloropropane (DBCP) was the primary chemical used to control nematodes. DBCP has desirable characteristics for a nematocide. It is less volatile than many other soil fumigants, such as methylbromide; remains active in the soil for a long time, and is effective in killing nematodes. However, it also causes sterility in human males, is relatively mobile in soil, and is persistent. Because of the health risks associated with consumption of DBCP treated foods, the nematocide was banned from use in the United States in 1979. After the ban, several well water studies were conducted in the SJV by state, county and local authorities. Thirteen years after DBCP was banned, contamination of well waters by the chemical persists as a problem in Fresno County.

Public concern over pesticides in ground water resulted in passage of the California Pesticide Contamination Prevention Act (PCPA) of 1985. It is a broad law that establishes the California Department of Pesticide Regulation

as the lead agency in dealing with issues of ground water contamination by pesticides. The PCPA specifically requires:

pesticide registrants to collect and submit specific chemical and environmental fate data (e.g., water solubility, vapor pressure, octanol-water partition coefficient, soil sorption coefficient, degradation half-lives for aerobic and anaerobic metabolism, Henry's Law constant, hydrolysis rate constant) as part of the terms for registration and continued use of their products in California.

establishment of numerical criteria or standards for physical-chemical characteristics and environmental fate data to determine whether a pesticide can be registered in the state that are at least as stringent as those standards set by the EPA,

soil and water monitoring investigations be conducted on:

pesticides with properties that are in violation of the physical-chemical standards set in 2 above, and

pesticides, toxic degradation products or other ingredients that are:

contaminants of the state's ground waters, or

found at the deepest of the following soil depths:

2.7 meters (8 feet) below the soil surface,

below the crop root zone, or

below the microbial zone, and

creation of a database of wells sampled for pesticides with a provision requiring all agencies to submit data to the California Department of Pesticide Regulation (CDPR).

Difficulties associated with identifying the maximum depths of root zone and microbial zone have led to the establishment of 8 feet as a somewhat arbitrary but enforceable criterion for pesticide leaching in soils.

Selection and Implementation of an Approach

Assessment of ground water vulnerability to pesticides in California is a mechanical rather than a scientific process. Its primary goal is compliance with the mandates established in the PCPA. One of these mandates requires that monitoring studies be conducted in areas of the state where the contaminant pesticide is used, in other areas exhibiting high risk portraits (e.g., low organic carbon, slow soil hydrolysis, metabolism, or dissipation), and in areas where pesticide use practices present a risk to the state's ground water resources.

The numerical value for assessments was predetermined by the Pesticide Use Report (PUR) system employed in the state. Since the early

1970s, California has required pesticide applicators to give local authorities information on the use of restricted pesticides. This requirement was extended to all pesticides beginning in 1990. Application information reported includes names of the pesticide(s) and commodities, the amount applied, the formulation used, and the location of the commodity to the nearest section (approximately 1 square mile) as defined by the U.S. Rectangular Coordinate System. In contrast to most other states that rely on county pesticide sales in estimating pesticide use, California can track pesticide use based on quantities applied to each section. Thus, the section, already established as a political management unit, became the basic assessment unit.

The primary criteria that subject a pesticide to investigation as a ground water pollutant are:

detection of the pesticide or its metabolites in well samples, or

its failure to conform to the physical-chemical standards set in accordance with the PCPA, hence securing its position on the PCPA's Ground Water Protection List of pesticides having a potential to pollute ground water.