- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 09 October 2021

Understanding family planning decision-making: perspectives of providers and community stakeholders from Istanbul, Turkey

- Duygu Karadon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1086-8607 1 ,

- Yilmaz Esmer 1 ,

- Bahar Ayca Okcuoglu 1 ,

- Sebahat Kurutas 1 ,

- Simay Sevval Baykal 1 ,

- Sarah Huber-Krum 2 ,

- David Canning 2 &

- Iqbal Shah 2

BMC Women's Health volume 21 , Article number: 357 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

8300 Accesses

4 Citations

Metrics details

A number of factors may determine family planning decisions; however, some may be dependent on the social and cultural context. To understand these factors, we conducted a qualitative study with family planning providers and community stakeholders in a diverse, low-income neighborhood of Istanbul, Turkey.

We used purposeful sampling to recruit 16 respondents (eight family planning service providers and eight community stakeholders) based on their potential role and influence on matters related to sexual and reproductive health issues. Interviews were audio-recorded with participants' permission and subsequently transcribed in Turkish and translated into English for analysis. We applied a multi-stage analytical strategy, following the principles of the constant comparative method to develop a codebook and identify key themes.

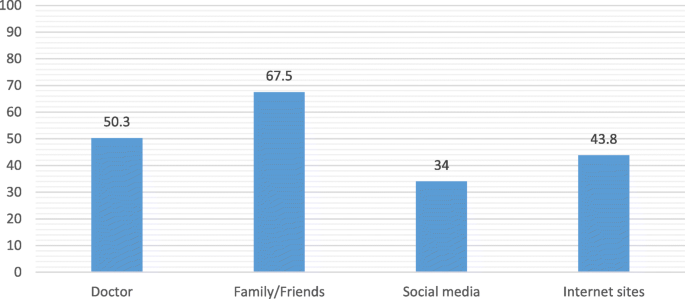

Results indicate that family planning decision-making—that is, decision on whether or not to avoid a pregnancy—is largely considered a women’s issue although men do not actively object to family planning or play a passive role in actual use of methods. Many respondents indicated that women generally prefer to use family planning methods that do not have side-effects and are convenient to use. Although women trust healthcare providers and the information that they receive from them, they prefer to obtain contraceptive advice from friends and family members. Additionally, attitude of men toward childbearing, fertility desires, characteristics of providers, and religious beliefs of the couple exert considerable influence on family planning decisions.

Conclusions

Numerous factors influence family planning decision-making in Turkey. Women have a strong preference for traditional methods compared to modern contraceptives. Additionally, religious factors play a leading role in the choice of the particular method, such as withdrawal. Besides, there is a lack of men’s involvement in family planning decision-making. Public health interventions should focus on incorporating men into their efforts and understanding how providers can better provide information to women about contraception.

Peer Review reports

There is considerable literature on the decision-making process related to fertility, and various factors have been proposed as predictors of family planning decision-making. Women’s characteristics, such as age, parity, level of education, level of income, occupation, and work status are the most frequently cited factors [ 1 , 2 ]. Additionally, previous studies have analyzed diverse factors that influence family planning decision-making within the family, such as power relations [ 3 ] and dominance of male partners [ 2 , 4 ]. Various studies in Turkey have found that many men are motivated to use family planning and would like to share responsibility for family planning decision-making (to use or not use any family planning method) [ 5 , 6 ]. However, there is also a tendency to view family planning as “woman's domain,” which refers to deciding whether to avoid pregnancy or not [ 7 ].

We would like to emphasize that cultural values also play an important role in impacting the use of family planning. Among these cultural factors, perhaps religious values top our list. Previous studies have also included ethnicity, male preference, traditional family values as well as the economic value of children as potential causal factors in determining family planning decisions. The present study aims at identifying significant contextual factors that are likely to influence use of family planning such as socio-cultural and religious norms.

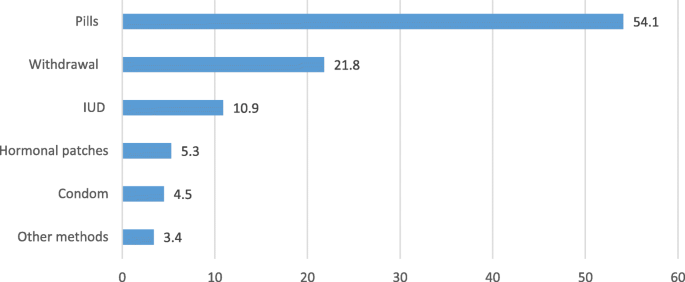

In the 1960s, Turkey adopted a national family planning policy that advocated the use of both traditional and modern contraceptive methods (i.e., sterilization, intrauterine devices (IUDs), implants, injectables, pills, condoms, emergency contraception, lactational amenorrhea (LAM), and standard days method), and expanded access to contraception through health clinics. According to the 2018 Turkey Demographic and Health Survey, women are very knowledgeable about contraception: 97% of all Turkish women know at least one method of contraception [ 8 ]. Further, almost half of married women use a modern contraceptive method [ 8 ]. The most commonly used modern methods are male condoms (19%), IUDs (14%), and female sterilization (10%) [ 8 ]. However, while the use of modern contraceptives increased steadily in the 1980s and 1990s, the prevalence rate has stagnated since the 2000s. Further, a sizable proportion of women continue to rely on traditional methods of family planning, such as withdrawal [ 8 ].

The dominant (almost exclusive) religion in Turkey is Islam. The government, which has been in power since 2002, actively promotes policies that encourage high fertility and discourage contraception and abortion. The Turkish Ministry of Health is responsible for designing and implementing health policies and overseeing all private and public healthcare services in the country. All residents of Turkey who are registered with the Sosyal Güvenlik Kurumu (SGK) Footnote 1 can receive free medical treatment in hospitals contracted by the agency. The services are provided by government hospitals, Aile Sağlığı Merkezi (ASM), Footnote 2 Ana Çocuk Sağlığı ve Aile Planlama Merkezi (AÇSAP), Footnote 3 maternity, and children’s hospitals, training and research hospitals, university hospitals, private hospitals, and private polyclinics. Family planning and abortion services are provided both in public, and private sectors, and modern methods may be accessed for free in government-funded primary health care units and hospitals or from pharmacies and private practitioners for a fee [ 9 ]. In general, most women and couples obtain modern contraception from public sector sources, and pharmacies are the leading source of oral contraceptives and male condoms [ 8 ]. Women and men can also purchase emergency contraception, hormonal and copper IUDs, three-month contraceptive injections (Depo-Provera), and one-month contraceptive injections (Mesigyna) from pharmacies. IUDs cannot be inserted at pharmacies but are taken to health facilities to be inserted. Male condoms can also be purchased from markets and beauty shops.

The Turkish national curriculum does not provide sex education and the subject is rarely discussed in schools [ 10 ]. Since there is no formal education on reproductive health, most people are informed about family planning though friends, relatives as well as printed or social media. Basic information, education, and communication materials about contraception are provided by health facilities.

This study aims to delineate the factors that influence family planning decision-making processes from the perspectives of community stakeholders such as prayer group leaders, parent-teacher association members, and family planning service providers. We attempt to understand and explain these factors within the context of social and political tensions in Turkey most important of which are ethnic and secular-religious cleavages.

Study procedures

We used purposive sampling [ 11 , 12 ] to interview eight family planning service providers and eight community stakeholders in Bagcilar, Istanbul. Our sample includes fifteen females and one male participant. We determined the number of interviews based on the principles of theoretical saturation (i.e., the criterion for judging when to terminate interviewing at the point when no new information was being generated [ 13 ].

Bagcilar is one of the largest districts in Turkey with a population of 745,125 in 2019 [ 14 ]. We sampled key informants from different professional backgrounds, with different social status within their respective communities, and based on their role in influencing reproductive health. This enabled us to understand broader community and provider perspectives about women’s health concerns. In-depth interviews were conducted between April and May 2019.

We partnered with a local research firm that had extensive experience in conducting qualitative studies in the area. The research firm and research team generated a list of potential community stakeholders (such as members of local government, religious leaders, women’s groups, and community groups) and the research team made visits to the study area to organize the interviews. We identified service providers from public and private hospitals that offered family planning services in the study area, from a health facility assessment that we conducted less than six months prior. To map the availability of and access to family planning and abortion services, we conducted a facility survey in public and private facilitates that provided reproductive health services in the study area. The facility survey captured data on service availability and facility readiness (including staffing, hours of operation, and payment of user fees), services provided (including counseling, physical examination and contraceptive, and abortion methods), and commodity supplies. These were supplemented with in-depth interviews with key informants. The research firm used separate standardized scripts to recruit family planning providers and community stakeholders. The recruitment script included details about the study, its aim, and contact information for the principal investigators. The research firm scheduled a time for interview with providers and community stakeholders who were willing to participate in the study.

All respondents spoke Turkish and interviews were conducted by a trained Turkish female interviewer who was employed by the research firm. The interviewer had a university degree and was employed as a fieldwork director by the local research firm at the time of the interview. After a refresher training session about principles and techniques of qualitative research, ethics and confidentiality, and role-playing exercises with a supervisor, the interviewer piloted two different semi-structured interview guides (see selected questions in Table 1 ) (one interview with a family planning service provider and one interview with a community stakeholder). The interview guides were developed for this study in English and translated into Turkish (see Additional files 1 and 2 ). A randomly selected sample (approximately 5%) of the transcripts were back-translated and reviewed by the research team to ensure that translations were consistent and of high quality. The service provider interview guide included several topics related to accessing family planning, factors influencing decision to use contraception, and barriers to and facilitators of family planning use in the community. The community stakeholder interviewer guide captured information on socio-cultural beliefs influencing community preferences and attitudes regarding family planning. Topics were related to the availability and accessibility of contraceptives, the demand for contraception and abortion services, the influence of attitudes and beliefs on contraception and abortion accessibility, decision-making, and behavior of women regarding gender norms and decision-making between couples. The Turkish version of the interview guide was amended based on questions and feedback obtained during training and pilot test.

All participants received written information about the study and provided oral consent to participate. We did not collect any identifying information from participants. Face-to-face interviews were conducted in a private space (i.e., private rooms at the facilities for family planning service providers and community stakeholders’ homes), and audio recorded with permission from the participants. The interviewer took field notes during the interview. On average, interviews lasted approximately one hour. After interviews were completed, the research team transcribed each interview in Turkish and then translated it into English for coding and analysis. Transcripts were double-coded by the research team to ensure accuracy. We did not share transcripts with participants. Before data collection we received ethical approval from the Boards of Harvard School of Public Health and Bahcesehir University.

We used ATLAS.ti (Version 8.0, Scientific Software Development, Berlin) to manage and analyze the data. We further used an inductive, thematic analytical approach, guided by the principles of the constant comparative method to identify key themes arising from the data [ 12 ]. First, four researchers reviewed eight transcripts and developed an initial list of codes and general themes (see Additional file 3 ). Specifically, we used in vivo coding in ATLAS.ti to code participants’ spoken words and used their own words as codes. For example, one participant commented, “ One of my clients said that she would not use birth control pills because it was a sin.” The final title of the code became “sin” and similar statements referring to abortion as a sin were grouped together to create the theme. Next, four members of the study team read two transcripts aloud together and open-coded all text, in line with the principles of open coding and an inductive approach [ 12 ]. We reviewed all codes together (more than 200 codes), merging similar codes and grouping codes into themes and sub-themes. Next, once all major themes and sub-themes were agreed upon, we generated a final codebook, which included 51 sub-codes in six main coding groups, including demographics, family planning, abortion, socially-oriented perspectives, quality of services, and family planning programs. The study team double coded all transcripts. Two members of the study team were assigned to each interview in order to enhance the quality of the analysis.

Several key themes emerged from the data related to family planning decision-making. All themes were identified by two members of the study team. We decided to characterize emerging dominant themes related to most frequently discussed topics across all interviews.

Participants’ profile

Background characteristics of participants are shown in Table 2 . There were six physicians/gynecologists and two midwives in the group of family planning providers. The service providers in our sample had been providing family planning services for between one and 22 years. Regarding community stakeholders, two were associated with Ak Parti—the religiously conservative, ruling political party- as members Footnote 4 and representatives, Footnote 5 two were local parent-teacher association members, one was a neighborhood representative’s assistant and another was a member of a local prayer group. Additionally, there was a pharmacist and a pharmacist’s assistant in the group of community stakeholders. The pharmacist and the pharmacist’s assistant were assigned to the community stakeholder group since they frequently provided informal advice to women about contraceptive use and other reproductive health-related topics.

We wanted to understand family planning decision-making process in relation to decisions about whether to avoid pregnancy or not. Three main themes identified by the study team emerged from the transcripts, including the decision-making process, the role of male partners, and the role of religious beliefs on reproductive health decisions, that provide insight into how women and couples decide to use contraception, how they learn about contraception, and the types of contraceptives women and couples prefer (Table 3 ). In general, we found that there was considerable demand for modern contraceptives among women. The majority of respondents mentioned the increasing awareness about modern contraceptive methods, most notably young women wishing to delay or space childbearing and women who wish to limit births once they achieve their ideal family size. Providers’ narratives implied that they are supportive of these growing modern contraceptive trends and actively encouraged young women to take actions to meet their reproductive needs.

Decision-making process: preferences and access

Respondents differed in what they perceived as the most preferred contraceptive method for women. While they discussed a variety of modern contraceptive methods used by women in their communities, many agreed that traditional methods, such as withdrawal or periodic abstinence, were preferred. They frequently believed these traditional methods to be more effective than other modern methods, and also explained that women prefer these methods to avoid side effects and also for convenience in use. A gynecologist who had been serving in this position for four months said:

If you leave it to the clients, they will still use the withdrawal method. It does not matter if they are educated or not. Nearly 70% of them still use the withdrawal method… They think it is safe. They say they have been using it for five years and nothing happened, so they continue [to use it] . (Interviewee 15, Family planning provider)

Most respondents agreed that the use of contraception is a woman’s decision. A parent-teacher association member noted that “… women have to think about [birth control] as they are the ones who take care of the children. So the women make the decisions.” (Interviewee 8, Community stakeholder). Moreover, another participant summarized the situation with the following comment: “ Because they [women] don’t want to get pregnant. It is always the women who endure the hardships of pregnancy, so they make the decisions” (Interviewee 11, Community stakeholder). Although most respondents agreed that women are more likely than men to be involved in the choice of a preferred contraceptive method, decision-making within a family is multi-layered. Some respondents reported that mothers-in-law and fathers-in-law are also important actors who exert an influence on family planning matters. A physician who had been providing family planning services for approximately nine years explained:

I had a few clients whose mothers-in-law wanted their daughters-in-law to have more children. And this affects the spouses or the husbands and they think about having another child. As they live together, the mother-in-law or even the father-in-law influences [their decisions to have another child] . (Interviewee 6, Family planning provider)

All participants reported that modern contraceptive methods are widely available and easy to access from health care centers and pharmacies. The majority of respondents (both providers and community stakeholders) reported that women trust and respect family planning service providers. Nevertheless, with regard to obtaining information, women trust the contraceptive experience of other people like their friends and family members and therefore mostly rely on second hand information. A community stakeholder commented:

First, they [women] talk among themselves. For example, she asks me how I manage birth control, how I prevent pregnancy. I say that I use the pill or injections or that my husband uses a method. She says that if it is good, she will do it too. Then she goes to the health center to ask the nurses…It is the culture of the women here, nothing else. It is better for them to hear it instead of searching and learning, I think . (Interviewee 1, Community stakeholder)

A few participants discussed the influence that the characteristics of providers can have on decision-making. The narratives suggested that decision-making is influenced by accessibility and quality of services. One community stakeholder said:

If the doctor is male, women are shy, but just a little…Their husbands don’t let them [go]. They say “If the doctor is male, you can’t go… When we go there again with our husbands, and the doctor will say that I have been here before. Then I will have problems with my husband” they say . (Interviewee 1, Community stakeholder)

Most participants did not report difficulties with accessing contraception for any particular group of women, and they agreed that unmarried women and adolescent girls can access modern contraception. A few reported that modern contraceptive methods are available, but it is difficult for single women to obtain them, which is an indication of barriers to access among this sub-group of women.

As far as I know, single persons wouldn’t get them from somebody they know [meaning a provider, pharmacist, or friend]. It is easily accessible, but the social pressure is serious. So, it is easily accessible, but it is hard to get . (Interviewee 3, Community stakeholder)

Our findings suggest that there is no single explanation for family planning decisions among women in the study setting. Various factors influence family planning decisions, and factors such as the source of information, characteristics of service provider, and marital status play a role.

Role of male partners

Most respondents stated that demand for modern contraceptive services is stronger among women compared to men. The majority of respondents reported that men do not favor modern contraceptive use, but do not actively object to using them. It was evident from participants’ narratives that family planning decisions remain a “woman’s domain”—that is, it is women who typically decide whether to avoid pregnancy or not. Additionally, family planning service providers reported that men have very limited involvement with pregnancy planning and fertility decisions and that women often do not trust men to be involved in such decisions.

Men are not trusted to be involved with family planning by women. Men are fine with [women’s decisions] …I think this responsibility is given to the women in Turkey. Men do not care about it much . (Interviewee 15, Family planning provider)

A gynecologist who has provided family planning services for 14 years said:

…men have birth control methods such as withdrawal and condoms but generally the women come here to consult about the methods. But a lot of men use birth control too. When the women use IUD or the pill and experience side-effects, I think the men understand and they resort to methods such as withdrawal and condoms . (Interviewee 10, Family planning provider)

Participants reported that men are more likely to desire more children compared to women, but the burden of childrearing falls on women. A local midwife who had provided services for ten years in the community explained:

When [women] bear a child, most husbands do not help with childcare. It is as if the child belongs only to the mother; supposedly, he is the father. When the child is sick, the mother takes care of him/her; and when the mother is sick, the father cannot take care of the child… Men generally say that they are unable to take care of children. So, women want birth control methods to avoid consecutive births . (Interviewee 14, Family planning provider)

A local pharmacist who has been in that position for 36 years also indicated that men desire to have more children than their wives. She said:

…especially the husbands want more children, so the women sometimes get these [family planning methods] without telling their husbands . (Interviewee 3, Community stakeholder)

The role of religious beliefs

Participants reported few barriers to contraception, and the narratives suggest relatively few reasons for non-use. However, a frequent theme was the importance of religious beliefs on reproductive health decisions. A few participants reported that women believe that modern contraception, in general, or use of certain methods in particular, are sinful behavior. A gynecologist who had been in that position for 20 years said:

…our religious belief is against it; according to our faith, family planning is forbidden. What can you do with this person? He/she wouldn’t do it even if it were free . (Interviewee 9, Footnote 6 Family planning provider)

Further, a parent-teacher association member and a gynecologist reported that:

Some spouses consider [birth control] to be a sin. We hear it from our friends … Interviewee 8, Community stakeholder) Actually, there is prejudice against most of the birth control methods in our society… Modern contraception is considered a sin. They [referring to the people in the community] do not want birth control. Women do not want IUD. They use the withdrawal method . (Interviewee 13, Family planning provider)

Additionally, beliefs about the moral status of contraception seem to be influenced by women’s social networks. A pharmacist described the effects of shared beliefs around contraceptive decision-making, thus:

One of my clients said that she would not use birth control pills because it was a sin. A couple of months later, she got pregnant and had to have an abortion. I asked her who had recommended it; it turned out to be someone I knew. Then I called that person and said “Why are you misinforming people?” She told me that it was a sin. I told her “Isn’t abortion a sin? She had to have an abortion.” She said that it was not alive until it was three months old. I told her “Look, you don’t have the knowledge about it but you have opinions. You are misinforming people and playing with their lives. A lifeless thing does not grow; it is alive since the first moment that sperm fertilizes the egg. Do not misinform people, please. Send the people to the health centers or doctors but don’t misinform them.” She was offended but I think that the conversation was effective. (Interviewee 3, Community stakeholder)

The narratives suggest that there is contradiction between faith and behavior. In particular, women think that contraception could be against the will of God, but act in accordance with the dictates of modern life.

The findings from this study highlight the major factors that influence family planning decision-making. According to the 2018 Turkey Demographic and Health Survey, 99.5 percent of married women of reproductive age know at least one method of contraception [ 8 ]. Our results are consistent with the existing literature which shows that contraceptive methods (either modern or traditional method) are widely known in the community. Thus, a key finding from the study is that women, and particularly married women, are aware of at least one method of contraception. Therefore, high levels of knowledge of contraceptives provide opportunities for programs to address barriers that could hinder translation of such knowledge into practice.

We found that, according to the perceptions of key informants, traditional methods were preferred over modern methods, and most respondents explained that women prefer traditional methods mostly due to the absence of side effects and ease of use. There is widespread perception that modern methods might have undesired side effects. Additionally, there are religious reasons such as couples’ consideration of natural, easy use the method with more minor side effects for traditional methods being the most preferred methods. According to Cebeci et al., however, even religious beliefs should not be identified as the dominant barrier to contraceptives; they rather affect the choice of particular methods such as withdrawal [ 7 ]. The effect of religious beliefs on contraceptive choice may be the reason why couples continue to rely on traditional methods. There is, however, a need for studies to better understand the motivations for preference for traditional methods in the study setting and how women could be supported to ensure that such methods meet their reproductive needs.

Participants reported that family planning is a “women’s domain” although sometimes other family members, such as mothers-in-law and fathers-in-law, may influence decision-making. A study among married individuals in Umraniye which is another district of Istanbul also found that family planning decision-making was perceived as a “women’s issue” by male partners [ 7 ]. Yet, decision-making is not limited to women and women’s partners; family members are also involved in their contraceptive choices. These patterns underscore a need for a better understanding of intra-family relations and opportunities that such relations provide for supporting women in the study setting to realize their reproductive goals.

Our findings show that although women trust family planning providers on contraceptive issues, they have more confidence in the previous family planning experiences of other people like their friends, neighbors, or relatives. This underscores the significance of women’s social networks as a source of information as well as a determinant of behavior. As Yee and Simon found, women identified their social networks as one of the most influential factors in the family planning decision-making process, especially about side-effects, safety, and effectiveness, and most of them considered that information more reliable than other sources of information [ 15 ]. Husbands, however, do not tend to share information about contraception with one another. Thus, husbands may look to their wives to receive accurate and reliable information about contraception [ 16 ]. Understanding how women’s and men’s social networks influence contraceptive use in this setting may be key to increasing contraceptive use among women who do not want a pregnancy. Intervention studies might also consider leveraging women’s social networks to provide education about contraception (e.g., peer educators or women’s groups).

Related to the accessibility and quality of services that influence decision-making, our findings show that women prefer female to male physicians and consultants in matters related to contraception. In addition, some of the community stakeholders reported prejudice in accessibility to contraceptive methods against unmarried women. Pharmacies provide male condoms, pills, and emergency contraception without a written prescription in Turkey. The pharmacy sector provides more than 45% of the male-condom and pills [ 8 ]. Many unmarried women find it more convenient to obtain contraceptive supplies from pharmacies, despite contraception not being free at pharmacies. This is likely because many single women prefer to avoid social pressure in healthcare facilities and fear being ostracized for engaging in what is regarded as illegitimate sex. The finding that many women in the study setting prefer obtaining contraceptives from pharmacies suggests a need for improving the capacity of pharmacists to provide contraceptive information and counseling to clients.

Various studies in Turkey have found that a variety of perspectives need to be taken into account to fully understand family planning decision-making processes. On the one hand, men report that family planning is a shared responsibility [ 6 ], and that pregnancy planning should be done jointly between partners [ 17 ] which is consistent with existing evidence showing that male involvement and shared decision-making is a key element of reproductive decisions [ 5 , 18 ]. On the other hand, several studies show that men and women are not resistant to contraception, although women are perceived to be the ones making family planning decisions [ 7 , 19 ]. Our findings show that men are not much involved in family planning decision-making and it is often women who decide whether to avoid pregnancy or not. While some respondents suggest that men might be opposed to contraception, the majority reported that men were simply indifferent. Additionally, lack of men’s involvement likely stems from pro-natalist views. The findings suggest a need for a better understanding of couple-level contraceptive decision-making and how best to engage men in supporting women’s reproductive needs.

Studies show that various factors influence fertility decisions, including the number of living children [ 20 , 21 ], level of education of parents and especially of female partners [ 22 ], and socio-cultural norms and religious attitudes [ 17 ]. However, men, in almost every setting, desire more children than women [ 17 , 23 ]. In general, both family planning service providers and community stakeholders in our study reported that men desire more children compared to women. However, the burden of childrearing falls on women, which reflects gender roles in the family. Men’s desire for children could be associated with a need to continue the family line and enhance their social value [ 24 ], making sense in terms of the social value of having a child primarily for men [ 25 ]. This a further indication of the need for understanding the perspectives of men in the study setting and how best to involve them in supporting women’s reproductive needs.

Our findings showed that women placed greater importance on religious beliefs although in practice, such beliefs did not have a direct influence on decisions regarding family planning. Although women believed that contraception could be against the will of God, this did not stop them from using the methods. This is consistent with findings from another qualitative study which showed that religious beliefs were not barriers to contraception, but such beliefs influenced the choice of methods [ 7 ]. Religion does not often dissuade women and men from wanting small families, but instead of using the most effective methods, they instead rely on methods that they perceive to be in alignment with religious beliefs or methods that are not as bad as others. Although most respondents in our study reported that contraception is perceived as a sin, women still used methods. It is possible that religious values may encourage the use of traditional methods, such as withdrawal, that have a long and historical tradition of being used in this setting. Cebeci and colleagues found that, in addition to people’s consideration of withdrawal as a natural, easy to use method with less side effects compared to modern methods, some considered it the method encouraged by Prophet Muhammad, which indicates that modern methods are perceived as harmful [ 7 ]. The findings underscore a need for family programs in the study setting to incorporate empowerment principles in client counseling in order to address misconceptions about modern contraceptives influenced by religious beliefs.

Our findings may be influenced by the manner in which participants were selected. In particular, community stakeholders and service providers were purposively selected based on their familiarity with women’s reproductive health-related topics, including family planning, and the sample included only one male participant. All interviews were conducted in Turkish and translated into English for analysis. Although some meanings could be lost in the process, a small sample of the transcripts were back-translated to determine the extent of such loss. There was no loss in meanings due to translation from one language to another. Additionally, all interviews were conducted in a private space to reduce the risk of social desirability bias. By its very nature, our sample has limited external validity which prevents us from making inferences about patterns in the study setting or the country as a whole. Although our findings, based on a limited purposive sample with key informants, are consistent with the findings of other studies using larger samples with more diverse groups of women, further qualitative research with representative samples of reproductive age women is needed to determine the extent to which our findings are consistent with the prevailing patterns in the country as a whole.

Our study sheds light on the factors that play a role in women’s contraceptive decisions in Turkey, a country with a strong national family planning policy but characterized by political-religious differences in beliefs about use of family planning. Our first take is that women (as well as couples) have a strong preference for traditional methods and particularly withdrawal. Religious factors in particular and socially conservative values in general play an important role in the choice of method. However, it should also be noted that the strong preference for traditional methods is a more general phenomenon that is not limited to the prevalence of religious and conservative values.

Second, in most cases, men play a minimal, if any, in family planning decisions. This is of both practical and academic interest especially in a male-dominant culture. From a policy viewpoint it points out to the need of educating not only women but also men about the availability, advantages, disadvantages and possible risk of available methods.

Third and last, the link between values and family planning decisions at all levels seems to be evident and this relationship deserves further investigation.

Availability of data and materials

Anonymized data can be availed upon reasonable request to the first author.

Social Security Institution.

Family Health Centers.

Maternal and Child Health and Family Planning Centers.

AK Parti member is also member of parent-teacher association.

They are not politicians, but they act as liaisons between community members and the political party.

Male participant.

Abbreviations

intrauterine devices

lactational amenorrhea

Sosyal Güvenlik Kurumu

Aile Sağlığı Merkezi

Ana Çocuk Sağlığı ve Aile Planlama Merkezi

Koc I. Determinants of contraceptive use and method choice in Turkey. J Biosoc Sci. 2000;32(3):329–42.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Tadele A, Tesfay A, Kebede A. Factors influencing decision-making power regarding reproductive health and rights among married women in Mettu rural district, south-west, Ethiopia. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):155.

Article Google Scholar

Darteh EKM, Doku DT, Esia-Donkoh K. Reproductive health decision making among Ghanaian women. Reprod Health. 2014;11(1):23.

Orji EO, Ojofeitimi PEO, Olanrewaju BA. The role of men in family planning decision-making in rural and urban Nigeria. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2007;12(1):70–5.

Ozvaris SB, Dogan BG, Akin A. Male involvement in family planning in Turkey. World Health Forum. 1998;19(1):76–8.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Sahin NH. Male university students’ views, attitudes and behaviors towards family planning and emergency contraception in Turkey. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2008;34(3):392–8.

Cebeci DS, Erbaydar T, Kalaca S, Harmancı H, Calı S, Karavus M. Resistance against contraception or medical contraceptive methods: a qualitative study on women and men in Istanbul. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2004;9(2):94–101.

Hacettepe University Institute of Population Studies. Turkey Demographic and Health Survey [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2020 Apr 24]. http://www.hips.hacettepe.edu.tr/tnsa2018/rapor/TDHS2018_mainReport.pdf .

Karavus M, Cali S, Kalaca S, Cebeci D. Attitudes of married individuals towards oral contraceptives: a qualitative study in Istanbul, Turkey. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2004;30(2):95–8.

Yücesan A, Alkaya SA. Ignored issue at schools: Sexual health education. SDÜ Tıp Fakültesi Dergisi. 2018 Mar 1 [cited 2021 Mar 24]. https://doi.org/10.17343/sdutfd.342828 .

Berg BL. Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. 2nd ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 1995.

Google Scholar

Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. London: SAGE Publications; 1998.

Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine; 1967.

National Statistics Institute (TURKSTAT) [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Feb 3]. https://biruni.tuik.gov.tr/medas/?kn=95&locale=tr .

Yee LM, Simon M. The role of the social network in contraceptive decision-making among young, African American and Latina women. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(4):374–80.

Ortayli N, Bulut A, Ozugurlu M, Cokar M. Why withdrawal? Why not withdrawal? Men’s perspectives. Reproduct Health Matters. 2005;13(25):164–73.

Zeyneloğlu S, Kisa S, Delibas L. Determinants of family planning use among Turkish married men who live in South East Turkey. Am J Men’s Health. 2013;7(3):255–64.

Mistik S, Nacar M, Mazicioglu M, Cetinkaya F. Married men’s opinions and involvement regarding family planning in rural areas. Contraception. 2003;67(2):133–7.

Angin Z, Shorter FC. Negotiating reproduction and gender during the fertility decline in Turkey. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47(5):555–64.

Miller WB, Pasta DJ. Behavioral intentions: which ones predict fertility behavior in married couples? J Appl Soc Psychol. 1995;25(6):530–55.

Casterline JB, Han S. Unrealized fertility: fertility desires at the end of the reproductive career. Demogr Res. 2017;36(14):427–54.

Testa MR. On the positive correlation between education and fertility intentions in Europe: individual- and country-level evidence. Adv Life Course Res. 2014;21:28–42.

Tuloro T, Deressa W, Ali A, Davey G. The role of men in contraceptive use and fertility preference in Hossana town, Southern Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2006;20(3):152–9.

Odu O, Jadunola K, Parakoyi D. Reproductive behaviour and determinants of fertility among men in a semi-urban Nigerian community. J Community Med Prim Health Care. 2005;17(1):13–9.

Kagitcibasi C. The changing value of children in Turkey. Honolulu: East-West Population Institute; 1982.

Book Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the family planning service providers and the community stakeholder who participated in the study.

This study was funded by an anonymous donation to Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. This funding source had no role in the design of this study, data collection, analyses, interpretation of the data, or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Bahcesehir Universiy, Istanbul, Turkey

Duygu Karadon, Yilmaz Esmer, Bahar Ayca Okcuoglu, Sebahat Kurutas & Simay Sevval Baykal

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA

Sarah Huber-Krum, David Canning & Iqbal Shah

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

DK drafted the first version of the manuscript. DK, BAO, SSB, and SK conducted an open coding of all transcripts and grouped the codes into themes. Data analysis was conducted by DK and BAO. YE, SHK, IS, and DC reviewed the manuscript for substantial intellectual content and contributed to the interpretation of the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Duygu Karadon .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study was approved by the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human participants were approved by the Ethics Board of Bahcesehir University and the Institutional Review Board at Harvard University (Protocol #: IRB17-1806). All participants received written information about the study and provided oral consent to participate in the research. Oral consent procedures were approved by the Ethics Board of Bahcesehir University and the Institutional Review Board at Harvard University. Before each interview, the consent script was read aloud to women. Enumerators asked participants to provide oral consent to take part in the study and recorded the answer on the tablet. Oral consent was obtained, rather than written consent, to protect the privacy of respondents.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:.

Key Informant Interview Guide-Community Stakeholders.

Additional file 2:

Key Informant Interview Guide-Family Planning Service Providers.

Additional file 3:

Coding tree.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Karadon, D., Esmer, Y., Okcuoglu, B.A. et al. Understanding family planning decision-making: perspectives of providers and community stakeholders from Istanbul, Turkey. BMC Women's Health 21 , 357 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01490-3

Download citation

Received : 23 September 2020

Accepted : 24 September 2021

Published : 09 October 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01490-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Family planning

- Decision-making

- Health decisions

- Qualitative data

BMC Women's Health

ISSN: 1472-6874

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Family planning science and practice lessons from the 2018 International Conference on Family Planning

Jean Christophe Rusatira Roles: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Methodology, Project Administration, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review & Editing Claire Silberg Roles: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review & Editing Alexandria Mickler Roles: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review & Editing Carolina Salmeron Roles: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Methodology, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review & Editing Jean Olivier Twahirwa Rwema Roles: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Methodology, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review & Editing Maia Johnstone Roles: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review & Editing Michelle Martinez Roles: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review & Editing Jose G. Rimon Roles: Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Supervision, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review & Editing Linnea Zimmerman Roles: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review & Editing

This article is included in the International Conference on Family Planning gateway.

Family planning, return on investment, women empowerment, reproductive rights, reproductive health, gender empowerment, contraceptive technology

Revised Amendments from Version 1

We have amended the paper to address the comments from the reviewers. Abstract section: We have re-written the abstract to improve readability and clarify the thematic grouping process of the 15 tracks into 6 themes and to address other comments made by the reviewers. Introduction section: We have included more context on the theme. Lessons from ICFP 2018 section: We have made edits to address various comments to expand on the demographic dividend framing and human rights-oriented framing. We have also incorporated more information on the investments and political environment necessary to harness the DD. We have revised the Male Involvement in FP Programming section and provided copyediting to make the section more succinct. We have also made editorial copy editing to remove grammatical errors and improve the flow of the paper. References section: We have updated the reference list.

See the authors' detailed response to the review by Nguyen Toan Tran See the authors' detailed response to the review by Ann Biddlecom See the authors' detailed response to the review by Gillian Mckay

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s). Publication in Gates Open Research does not imply endorsement by the Gates Foundation.

Introduction

The family planning (FP) community acknowledges that access to safe, high quality, voluntary family planning is a human right. However, the majority of girls and women, particularly in developing countries, continue to have limited and inequitable access to sexual and reproductive health rights, information, and services, including FP 1 . Although more than 500 million couples in developing countries use FP, the United Nations estimates that by 2030, nearly 200 million women seeking to delay or avoid having a birth will have an unmet need for modern contraception 2 . This demand will likely continue to grow as record numbers of young people enter the prime reproductive ages in the decades to come. It is thus essential that the family planning community identifies high impact approaches to address the major barriers and gaps affecting equitable access to quality family planning.

Since its inception in 2009, the International Conference on Family Planning (ICFP) has served as a strategic inflection point for the FP and reproductive health community worldwide. ICFP serves as an international forum for scientific and programmatic exchange that enables the sharing of available findings and the identification of knowledge gaps, in addition to facilitating the use of new knowledge to transform policy. At the London Summit in 2012, the global FP community set an aspirational goal to enable 120 million more women and girls to access voluntary quality FP by 2020, and the FP community broadened that goal to include universal access to reproductive health care and services by 2030 3 , 4 . The ICFP has been an important, collaborative effort in the buildup to establishing that goal, raising visibility, creating momentum around FP, and leading to concrete changes in policy and programs.

The 2018 ICFP, held in Kigali, Rwanda, was centered on the overarching theme, “Investing for a Lifetime of Returns”. This theme was chosen because of the essential role of FP for the realization of all 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and spoke to the various returns that investments in FP provides — from better sexual and reproductive health outcomes and improvements in maternal and child health, to education and women’s empowerment, to long-term environmental benefits and socio-economic growth 5 . Over 700 oral presentations were featured at the conference and covered FP advocacy wins, services developments, and research. Oral presentations were grouped into the following conference tracks: 1) Returns on investment in family planning and the demographic dividend; 2) Policy, financing, and accountability; 3) Demand generation and social and behavior change; 4) Fertility intention and family planning; 5) Reproductive rights and gender empowerment; 6) Improving quality of care, 7) Expanding access to family planning; 8) Advances in contraceptive technology and contraceptive commodity security; 9) Integration of family planning into health and development programs; 10) Sexual and reproductive health and rights among youth and adolescents; 11) Men and family planning; 12) Family planning and reproductive health in humanitarian settings; 13) Faith and family planning; 14) Urbanization and reproductive health; 15) Advances in monitoring and evaluation methods. This paper summarizes the highlights of the scientific program and identifies key findings presented during the oral sessions in the fields of research, programming, and advocacy in order to inform future work in these fields.

The findings summarized in this paper are from 64 abstracts from individual and preformed panel submissions accepted for oral presentations at ICFP 2018. Each co-author of this paper reviewed abstracts from up to three conference tracks based on their expertise and provided summaries from these tracks, organized by emerging key themes. The final abstracts were selected for inclusion in this paper based on the novelty of the findings and contribution to the FP field. These summaries were incorporated to develop the final draft of the paper.

Lessons from ICFP 2018

Investing in family planning for a lifetime of returns.

Measuring the returns on investments in FP is crucial for continued funding and support for FP programs. The business cases for FP presented at ICFP demonstrated the ways in which cost-effective FP programming may save money in the short-term and long-term at the individual, community, donor, and national levels. Willcox and colleagues developed a model based on 47 county referral hospitals in Kenya, which demonstrated that for every dollar invested in training and equipment for implant removal services, a future return of USD $1.62 would be accrued from the economic benefits of continued implants uptake 6 . Costing data presented by Tumusiime and colleagues found that in Senegal and Uganda, the total costs—including direct medical costs (i.e. provider time, supplies, drugs), costs of self-injection training (based on a one-page instruction sheet scenario), and direct non-medical costs (i.e. client travel and time costs)—are significantly lower for the self-injection of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate administered subcutaneously (DMPA-SC) as opposed to provider-administered injectables 7 . In Nigeria, Adedeji and colleagues found that for every $1 invested in high-impact intervention-focused FP programs, an estimated $1.40 may be saved on maternal and newborn care, and another $4 could be saved on treating complications from unplanned pregnancies 8 . While self-administered DMPA-SC may provide a cost-effective approach to improving access to long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods, a study conducted in Rwanda identified LARCs to be more cost-effective than non-LARC methods post-partum, with a savings of $31.42 per pregnancy averted for two years following birth, and additional cost savings expected over longer time frames 9 .

FP may also be a catalyst for the demographic transition and an opportunity to realize the benefits of the demographic dividend. The demographic dividend describes the changes in the population age structure caused by reductions in population-level fertility and mortality rates. These structural population changes result in a large working-age population and a smaller number of youth dependents 10 . With the correct set of political, economic, educational, and employment policies and opportunities, countries characterized by this population age structure have the potential to take advantage of the large working age population to bolster socio-economic development and create generational wealth 11 . Furthermore, this demographic transition may help countries achieve SDG targets. Modeling has shown that FP investments can positively affect SDGs across several sectors including health, governance, economic growth, agriculture, and education 12 , 13 . Despite improvements in FP funding and financing, expanded financial investments in FP are still needed throughout much of sub-Saharan Africa in order to successfully reach the FP targets necessary for countries to reap their demographic dividend potential 14 , 15 .

Strategies to sustain FP advances include long-term financing for FP, particularly the transition from donor-dependent financing to locally owned initiatives. Donor funding to support FP continues to fall short of the amount needed to address the unmet need of family planning globally and the extent of this gap varies significantly across countries and regions 16 . To mitigate the impact of this shortage in donor funding, it is critical for countries to plan for shifts in financing options, including the procurement of finances for subsidized commodities. Locally owned community-based health insurance (CBHI) schemes, characterized by voluntarily pooled funds, may be a promising option in order to sustain FP financing 17 . Research on CBHI schemes from sub-Saharan Africa showed positive effects on healthcare utilization and FP uptake. In Ethiopia, Pathfinder International found that women who were enrolled in a CBHI scheme were 1.3 times more likely to practice modern FP than those who were not enrolled 18 . Since 2014, the Ethiopian government has slowly shifted away from donor-dependence and has launched and expanded the number of CBHI and social health insurance (SHI) programs in more than one-third of districts. Based on current projections, by 2025, the number of modern contraceptive users in Ethiopia will have doubled from 6 million to 12 million, and the private sector will account for 40% of them 19 .

Data gleaned from nationally representative datasets showed a similar global pattern in factors associated with FP utilization. Findings from the Ethiopia (2016), Kenya (2014), Nigeria (2013), and Philippines (2013) Demographic Health Surveys (DHS), as well as Indonesia’s 2015 Susenas survey, revealed trends in the number of insured women and the modern contraceptive prevalence rate (mCPR); specifically, the ratio of mCPR between insured versus uninsured individuals was greatest among women of the lowest socioeconomic status (SES) in the Philippines, Kenya, Indonesia, and Ethiopia 20 – 23 . Insurance coverage was shown to be directly associated with FP utilization. These findings signify the importance of comprehensive health insurance for FP access, particularly amongst marginalized groups 24 . Another important finding related to FP access and insurance showed how national health priorities supersede FP access. While FP is often included under universal health coverage (UHC) schemes, the inclusion of FP is often not operationalized or realized 25 . Data from 22 priority FP2020 countries showed that the challenges to comprehensive UHC include government prioritization of less cost-effective yet urgent curative services, instead of preventive care or primary services 26 .

Additionally, research on health financing highlighted opportunities for new financing models and insurance schemes. In Tanzania, the United Nations Fund for Population Activities (UNFPA) and DKT International implemented an innovative micro-insurance scheme for urban youth and adolescents, which demonstrated high uptake in just one year of initiation. This program, “iPlan”, required a nominal annual fee of $10, after which an individual received comprehensive sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services including contraceptive counseling and commodities for one year 27 . Similarly, researchers found that the Public-Private Partnership Health Posts model in Rwanda was a cost-effective and viable solution for individuals living more than 60 minutes away from health facilities 28 . The social franchising model created by the Family Health Guidance Association of Ethiopia (FGAE) was also shown to be a cost-effective model as compared to static clinics. When compared to the FGAE-owned static clinics, the cost per Couple Years of Protection (CYP), (an indicator used to estimate protection from pregnancy by family planning/contraceptive methods during a one-year period) 29 was significantly less expensive. CYP provided through the FGAE social franchise model was estimated to be between USD $0.73-$1.77, compared to USD $25.61-37.35 per CYP provided at the FGAE-owned static clinics 30 .

Addressing inequities in family planning for adolescents, youth, and key populations

Inequities in access to FP exist across women from different socio-economic groups, age cohorts, health statuses, and physical abilities. Compared to women of other reproductive ages, adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) have specific FP and sexual and reproductive health needs, including low contraceptive uptake, high risk of unintended pregnancies and unsafe abortions, high risk of sexually transmitted infections, and a greater risk of acquiring HIV 31 , 32 .

Involving youth in advocacy and programming efforts was shown to be critical in order to ensure that their unique FP needs are met. Reproductive Health Uganda developed an innovative program to support young people in realizing their right to hold state-actors accountable for improving access to youth-friendly health services. The initiative led to the successful allocation of county-level funds for youth-friendly services in all sectors and created a network of youth advocates for FP programming 33 . In Kenya, the Network for Adolescents and Youth of Africa developed a holistic advocacy network in Kisii County that led to the allocation of KES 7,000,000 (USD 68,000) to contraceptive procurement and FP services in the financial year 2016/2017, the first time a line item for FP was included in the county budget 34 .

FP programs for youth with hearing and speech impairments included a sexual health education program for adolescents in Vietnam and a social media literacy program integrating SRH and FP information exchange in Burkina Faso 35 , 36 . In Egypt, Love Matters Arabic Project was launched to engage young people on SRH issues, dispel myths and taboos, and improve access to accurate and reliable SRH and FP information 37 . Some researchers maintain that to attract youth and gain their trust, programming must include a pleasure component and tie this information to healthy sexual behaviors and practices 29 , 38 . This hypothesis needs further exploration in future research and programming.

Other key populations highlighted during the conference included youth living in conflict zones, people living with HIV, women with disabilities, female sex workers, people who use drugs, individuals with a low socioeconomic status, and individuals who do not identify as heterosexual 39 , 40 . A nationally-representative survey from Ethiopia found that more than 95% of women living with a mental, physical, or visual disability face obstacles in physically accessing health facilities and are less likely to have access to FP information 38 . Furthermore, this sub-population may be more likely to face discrimination by healthcare providers. These barriers to FP services and knowledge may have direct consequences on health outcomes. For example, among women with disabilities who have ever had a pregnancy, more than 85% reported that the pregnancies were unintended 41 .

Studies from conflict zones in Afghanistan, Cameroon, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Yemen showed that girls who marry before the age of 18 have lower rates of FP use, less intention to use in the future, and a significantly higher risk of unintended pregnancy, compared to married women 18 years of age and older 42 . Among Somali refugee girls aged 10–19 and living in Ethiopia, nearly 75% of girls were aware of how to become pregnant, but fewer were aware of the risks associated with inadequate birth spacing. Despite nearly one in five girls having already given birth, 40% of participants remained unaware of methods to avoid pregnancy 43 .

People living with HIV may also have trouble accessing comprehensive FP services. A study from Uganda found that unmarried women with an HIV-positive status and women of high parity were significantly less likely to use FP post-partum 44 . Women who take antiretroviral therapy have desires to bear children, learn about contraception, and receive information on methods to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV 45 . To this end, it is important that programs recognize this population’s unique desires and needs. A program in London demonstrated the promise of service integration to improve access to FP for women living with HIV; Mabonga and colleagues found a 50% increase in LARC use after the integration of FP and HIV services in a postnatal contraception clinic in London 46 . Integrating HIV and FP services into one convenient location helps promote healthy SRH and child health outcomes, while also easing client burden associated with traveling between different clinics.

Reproductive justice: Abortion care, family planning, and women’s wellbeing

Unsafe abortions have emerged as one of the key neglected public health problems, accounting for more than 1 in 10 maternal-related deaths worldwide 47 . Accordingly, abstracts discussing safe abortion access and FP were cross-cutting through the conference’s tracks. Research on unsafe abortions underscored the determinants of abortion practices as well as inequities in the accessibility of safe abortion services. For example, in both Nigeria and Rwanda, younger, uneducated women in rural areas are more likely to seek out and use abortion services. However, due to restrictive abortion laws, these abortions are often unsafe, which poses not only health challenges but legal challenges as well 48 . In 2012, 24% of all incarcerated women in Rwanda were imprisoned for participating in clandestine, illegal abortions 49 . Access to safe abortion services is a critical component of comprehensive SRH yet continues to be heavily restricted in many parts of the world. Several authors called for targeted advocacy for legal provisions to ensure the availability of safe abortion services 50 , 51 . Amendments to national laws, increased and expanded training of providers, and improved access to medical abortions were highlighted as priorities for policymakers 24 , 52 . Furthermore, emphasis was placed on the recognition of social disparities and inequities in abortion prevalence and access 45 .

Analyses of post-abortion care (PAC) programs for women in humanitarian settings in DRC and Yemen found that providers may effectively shift from unsafe practices of dilation and curettage (D&C) to manual vacuum aspiration and medical treatment with misoprostol. Over a period of 5 years, the percentage of PAC clients requiring evacuation who received D&C as treatment was reduced from of 18.6% to 2.0% in DRC and from 25% to 2.8% in Yemen 53 .

Expanding access to safe abortion services can also directly increase women’s access to FP. Research from Kenya found that, regardless of pregnancy intentions, over 70% of women who attended PAC initiated contraceptives during their PAC visit 54 . Analyses of post-abortion family planning (PAFP) service delivery across two states in India also revealed that 28% of women adopted a contraceptive method within two months after their abortion 55 . Another study from Kenya found that women’s PAFP method varied based on the type of abortion the woman experienced. While women who had undergone surgical abortions were more likely to choose intrauterine devices or other LARC methods, women who had medical abortions were more likely to choose implants. While this may be due to the fact that IUDs can be inserted following a surgical abortion but not following a medical abortion, further research is necessary to ensure women receive the FP method that best suits their needs, preferences, and fertility desires 56 . Insights into context-specific ideals of family size as well as abortion care-seeking behaviors are important in understanding how to improve future PAFP service delivery and increase contraceptive use 51 .

Couple dynamics and family planning decision-making

Research on women’s covert use of FP underscored the ethical tensions between supporting and validating women’s ability to exercise reproductive autonomy without disclosure to a partner while also striving to engage male partners in reproductive health decisions 57 . Research revealed that a woman’s decision to covertly use FP may be linked to discordant partner views on childbearing and fertility desires 58 . One study found that when men expressed beliefs that contraception is “women’s business”, women were more likely to engage in covert use and not disclose their FP decisions to their partners 53 . However, women who use FP covertly often struggle with the cost of contraceptives and worry about concealing FP from their partners 53 . Power dynamics continue to influence FP use, even when women choose to use FP methods covertly.

Couple power dynamics and household decision-making also influences FP utilization. Easterlina and colleagues found that 75% of women in West Pokot, Kenya, identified their husband or partner as the biggest barrier to voluntary FP use 59 . In the Afar region of Ethiopia, 58.8% of women reported not having the freedom to make independent fertility decisions 60 . Conversely, researchers have found that the odds of using modern contraception increases significantly when couples make decisions together 61 . Couples who reported shared decision-making on everyday life choices (e.g. financial decisions) in Ibadan, Nigeria, were more likely to report using FP than couples in which decisions were made solely by the husband 62 . Other factors which have been found to influence FP uptake include the educational status of couple dyads, couple’s knowledge of reproductive health and rights, women’s economic security and involvement in microcredit schemes, and gender equitable household dynamics 63 , 64 .

Male involvement in family planning programming

Considering men’s influence on FP decisions, involving male partners in FP programming is essential to meeting FP goals globally. Males have a desire to learn about FP and contraception but often have limited or inaccurate information which fuels false beliefs and myths. In Uganda, when men were asked why they do not allow their wives to use modern FP methods, participants expressed fears that their wives were likely to become promiscuous if they began using contraception. The researchers also found that male participants’ beliefs about FP were often inaccurate, inconsistent, or grounded in gendered stereotypes, fueling fears about wives’ promiscuity 65 . Similarly, research from Kenya showed that 50% of men in Western Kenya lack accurate knowledge on the possible benefits of healthy timing and spacing of pregnancies 55 . In Nepal, men’s limited understanding of contraceptives were shown also to impact their partner’s uptake of IUDs 66 .

Research revealed the potential of male champions and advocacy networks in changing social norms, educating male peers, and creating a culture receptive and open to family planning discussions. In Uttar Pradesh, India, a community-based information diffusion strategy was used to dispel FP myths and misconceptions and provide comprehensive information on non-scalpel vasectomy. To accommodate the diverse lives of men living in informal settlements, men were engaged by their peers at traditional male gathering points at convenient times, such as evening meetings for rickshaw pullers 67 . In Zamboanga City, Philippines, a packaged community-based learning program, EL HOMBRE, used a peer-to-peer information dissemination technique to share information related to FP, family matters, and family planning 68 . Similarly, a male champions program was rolled out successfully in Western Kenya, where 50 male champions held sensitization forums once a month to encourage discussions on healthy timing and spacing of pregnancies 55 . In Benin, USAID/ANCRE implemented a “men as advocates” intervention that included counseling male spouses on FP when their partners left the maternity ward and creating groups of “committed men” to sensitize male peers. Over the course of a year, post-partum FP counseling for males increased by more than 100% across 47 health facilities 69 .

Couple-based approaches to behavioral change and FP uptake also show promise. Project Concern International implemented a social and behavioral change program that used couples as community change agents to address restrictive social norms and SRH myths, improve couple communication strategies, and aid couples in the development of their FP and fertility goals 70 . The Emanzi program in Uganda also showed a positive changes in equitable gender norms, a rise in shared decision-making in the household, and a significant increase in FP uptake 71 .

Gender-transformative programming is grounded in the notion that changes in gendered norms, beliefs, and behaviors lead to positive health outcomes. Landmark gender-transformative programs included the Bandebereho intervention in Rwanda, which consisted of 15-week group education meetings for more than 4,000 young adult men and women and 1,700 expectant and new fathers and couples. When compared to the control group, findings showed an increase in the proportion of young people who had sought SRH services, as well as changes in positive gender norms and increases in shared decision-making 72 . The GroupUp Smart education curriculum in Rwanda targeted prepubescent male and female adolescents and their parents. The program found that adolescent boys’ awareness of preventing pregnancy increased from 65% to 81% and their knowledge of reproductive health significantly increased. Compared to pre-intervention, adolescent boys experienced significant increases in gender equity scores, pointing to the notion that SRH education which includes a gender component may be more beneficial than SRH education alone, particularly when introduced earlier in life 73 .

Breakthroughs in novel contraceptives and systems improvement in family planning

Research advances in contraceptive technology highlighted the importance of beginning with the end-user in mind. In Nigeria and India, initial acceptability research of a microneedle contraceptive patch (MNP) explored client perceptions of the method and quantified desired MNP attributes. Across both contexts, prospective users liked the potential for self-application and both providers and clients found the method to be easily used. Researchers also wanted to identify user preferences for other attributes, including the method’s effect on menstruation, duration of effectiveness, placement location, pain, and the potential for skin reactions at the application site 74 . These findings underscored high overall acceptability of microneedles as a novel delivery method, yet also emphasized the importance of reducing side effects associated with existing contraceptive methods.

Use of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) has risen rapidly in high-income countries and is one of the most effective forms of contraception available. However, the cost of the method is typically a barrier to clients in low-income countries. Research by Marie Stopes International Nigeria and FHI360 piloted the introduction of an affordable version of the LNG-IUS at multiple service delivery points and found that users, providers, and key opinion leaders were receptive and enthusiastic about the method. Many clients also reported reduced menstrual bleeding as a key non-contraceptive benefit of the method. This research also suggested that a multi-stakeholder approach, including coordinated demand-generation activities, may be important in order to advance the scale-up of LNG-IUS in Nigeria and in other similar contexts 75 .

Improved access to subdermal implants and other long-acting methods like IUDs have raised concerns on whether women can access timely removal services on-demand. Data from pilot studies examining the subdermal implant removal tool, RemovAid, suggested that this novel device is safe to proceed to larger studies, and with it, physicians can safely remove one-rod implants and minimize the removal time to just under seven minutes 76 . Furthermore, initial acceptability research revealed that a novel postpartum IUD inserter would be attractive in India due to high unmet need and a lack of trained providers 77 . These products would not require additional supplies, aside from what it’s packaged with, and demonstrated high client and provider satisfaction.

Novel approaches to service delivery and contraceptive commodity procurement included the development of an “informed push” model, which would change the public health sector’s reporting system to allow for consolidated transport routes and combined supply delivery. Rather than following a typical model where an individual health facility is responsible for FP commodity reporting, product requisition, and pick-up, this model relied on health “zone staff” to optimize transport routes and report on stockouts and product consumption. By consolidating FP commodities alongside other health products and optimizing transit routes, the study demonstrated a substantial reduction in the incidence of stockouts and a decline in transit costs 78 . In India, an application developed by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare also seeks to collect consumption data, forecast demand, and track commodity distribution. While still in the formative stage, individual states have demonstrated an interest in customization of the app per state to allow the government to improve commodity distribution and transfers by tracking “live” data 79 .

Lastly, algorithm-based fertility apps, such as the Dynamic Optimal Timing application, demonstrated a typical-use failure rate that was comparable to or better than other user-initiated methods, including fertility-awareness based methods. This method delivered consistently correct information to women about their daily fertility status, which suggests that the app could allow women to self-manage fertile days to avoid pregnancy 80 .