- Open access

- Published: 06 February 2024

Large-scale cultural heritage conservation and utilization based on cultural ecology corridors: a case study of the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin in Guangdong, China

- Ying Sun 1 ,

- Yushun Wang 2 ,

- Lulu Liu 3 ,

- Zhiwei Wei 1 ,

- Jialiang Li 1 &

- Xi Cheng 1

Heritage Science volume 12 , Article number: 44 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

671 Accesses

Metrics details

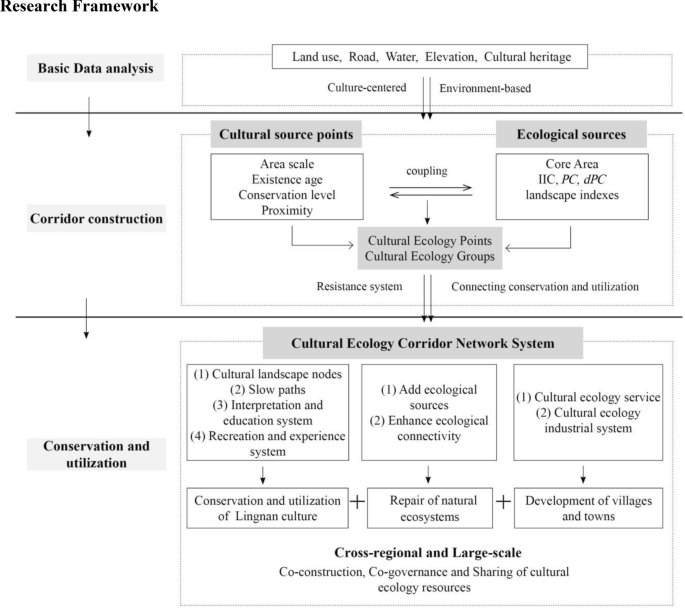

In the field of world heritage conservation, there has been broad consensus on carrying out heritage conservation research on the basis of spatial integration and interregional and international cooperation. However, there are still many deficiencies in the integration of culture with the environment, regional economic and social development, and the regional, holistic and multimodal conservation and utilization of cultural heritage sites. In China, the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin is a representative area of substantial cultural and ecological value for both Guangdong Province and the whole country. This paper uses the morphological spatial pattern analysis and the minimum cumulative resistance model to integrate cultural ecology sources and establish a cross-regional and large-scale cultural ecology network system that includes 1 main corridor, 22 important corridors and 17 secondary corridors. In addition, based on identified cultural landscape nodes and cultural ecology services, the economy of the cultural ecology corridor could be developed with large-scale co-construction, co-governance and shared working mechanisms to overcome administrative limits and realize the conservation and utilization of multimodal and large-scale heritage sites. This approach has strong theoretical and practical significance for innovative methods in cultural ecology research, as well as for new content in the research of Lingnan culture, ecosystem restoration, and the economic and social development of towns and villages. This article supplements unilateral studies of regional culture and ecology and demonstrates an in-depth application of cultural ecology theory.

Introduction

Cultural heritage, characterized by its longevity, diversity, rich artifacts, wide distribution and exceptional value to society [ 1 , 2 ], is an important carrier of historical lineage that supports national pride and historical cultural inheritance. Many regions rely on similar natural geographic environments, important regional transportation corridors (rivers, historical trails, railroads, etc.), or the needs of historical migrations, military defense, and economic development. Many of the strong commonalities and intrinsic links between cultural heritage, culture and the environment still maintain a strong level of vitality and continue to evolve temporally and spatially [ 3 ]. In the field of world heritage conservation, there has been broad consensus that heritage conservation research should be carried out on the basis of spatial integration with interregional and international cooperation [ 4 ]. However, at present, China's cultural heritage traditions face the following challenges: (1) the isolation and separation of heritage from the environment [ 5 , 6 ]; (2) a lack of connection between heritage traditions [ 7 ]; (3) a singular conservation and utilization mode for individual traditions, such as heritage museums and cultural tourism villages [ 8 , 9 ]; and (4) in addition, due to the limitations posed by administrative divisions and departments, governance tools at all levels, such as conservation policies, conservation works, and conservation funds, cannot be coordinated across the whole system, so that it is difficult to identify the objects of conservation, including material and nonmaterial cultural resources, and coordinate conservation and utilization plans [ 10 ]. Therefore, an important part of the conservation and utilization of cultural heritage in China at this stage is to carry out broad investigations, analyses and plans based on unique regional culture that will break through the prevailing style of “classification” research in cultural heritage of the past few decades [ 11 ] and construct an “overall” framework for research on a large scale across regions [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ].

The essence of the decline and demise of cultural heritage is the incompatibility between heritage and environmental development. In the conservation of historical and cultural heritage, international attention on the historical environment began very early. The conservation criteria included “urban or rural setting” (ICOMOS, Venice Charter, 1964) [ 16 ]; “historic areas and their surroundings” (UNESCO, Nairobi, 1976) [ 17 ]; “the town or urban area and its surrounding setting” (ICOMOS, Washington Charter, 1987) [ 18 ]; and “historic cities, towns and urban areas as important elements of urban ecosystems, noting that conservation not only entails the enhancement and management of these areas but also a synergistic development that promotes sustainable and holistic conservation and the harmonious development of historic towns as integral parts of urban ecosystems” (ICOMOS, Valletta Principles, 2011) [ 19 ]. The trend of regionalization and integration of heritage conservation is further manifested in the integration of heritage sites with the surrounding environment. In 1955, Julian H. Steward, an American cultural anthropologist, proposed the term "cultural ecology", which emphasizes the interaction between culture and the environment, focusing on the relationships among the environment, biological organisms and cultural elements [ 20 ]. It focuses on the mutual “adaptation” of culture and environment, which is a methodology of cultural research [ 21 ]. On this basis, the cultural ecology system further emphasizes the organic unity of the cultural community and its environment. There are three characteristics of adaptability, variability and integrity between culture and the environment. Adaptability refers to the cultural factors that shape a good living and development environment for one’s own needs; variability refers to the adjustment and change in cultural factors according to changes in the natural and social environment, which may manifest as the variation and integration between cultures or cultural adaptation and decline under changes in the natural environment; and integrity refers to the mutual influence and adjustment of cultural and environmental factors in an open cultural ecosystem. Through the adjustment of the development direction of the two systems, cultural ecology factors are integrated into a stable system, that is, the cultural ecology system [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ].

In recent years, research on cultural ecology in the study of cultural heritage has involved the following aspects, among others: heritage corridor construction [ 26 , 27 , 28 ], ecological network construction [ 6 , 29 , 30 ], delineation of heritage conservation areas [ 31 ], cultural landscape mapping of traditional villages [ 32 , 33 , 34 ] and cultural landscape security patterns [ 35 , 36 ]. The importance of holistic heritage conservation and the integration of heritage and the environment has been widely recognized worldwide. However, several issues still need to be discussed continuously, such as the following: (1) How can cultural heritage be better integrated into the regional environmental network and an organic network that closely combines culture and the environment be formed? (2) How can a single heritage point and a single pathway for tourism utilization be multiplied to promote the overall and multimodal cultural and environmental conservation, restoration and utilization of the heritage site? (3) How can the constraints of administrative boundaries be overcome, convenient channels for the flow of resources between regions be established, and the overall conservation and utilization of heritage regions be realized?

With the above questions, from the perspective of cultural ecology, this paper draws on the method of constructing heritage corridors [ 14 ] to focus on the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin in Guangdong Province, which features a concentration of Lingnan culture. The understanding of the geography of linear space and place has deepened and expanded. Combined with the cultural ecology of the study area, the adaptability, variability and integrity are discussed from the perspective of the system, and a large-scale conservation and utilization system with a transadministrative boundary integrating cultural heritage and the environment is established. We believe this work has made certain contributions to the conservation of cultural heritage at both the theoretical and practical levels.

Study area and methods

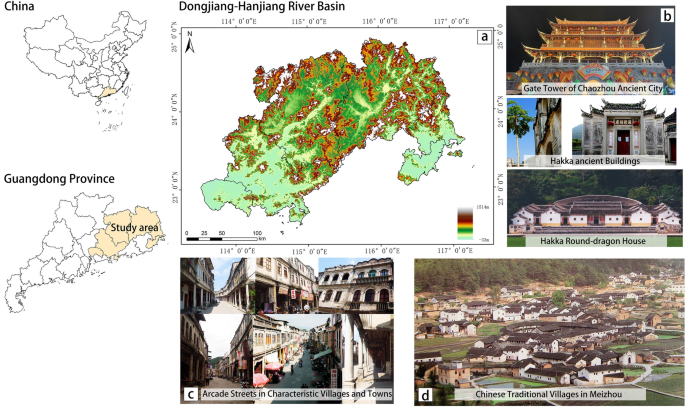

Guangdong Province, located in the southernmost part of mainland China, is one of the three major gathering places of Lingnan culture in China. Lingnan culture has made indelible contributions to the formation and development of the Han nationality, the main ethnic group in China, as well as to national unity. This culture occupies an important position in the history of Chinese national culture. Lingnan culture in Guangdong Province has three main subgroups: Guangfu culture, Hakka culture and Chaoshan culture (Table 1 ) [ 37 , 38 ]. At present, there are approximately 38 million Guangfu people, 16 million Chaoshan people and 14 million Hakka people in the world. In terms of geographical space, this population is mainly distributed in the Pearl River Delta (Guangfu) and the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin area in the northeastern part of Guangdong Province (Chaoshan and Hakka). In this paper, the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin is taken as the scope of study (Fig. 1 ). The geographical area represents the great cultural and ecological value of the whole country.

The geographical location of the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin and the spatial distribution of its cultural heritage resources. a Location of the study area, b Ancient buildings, c Arcade streets in characteristic villages and towns, d Chinese traditional villages

In terms of culture, the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin is the main gathering place for Chaoshan and Hakka cultures. The Dongjiang and Hanjiang Rivers run through the core area and subregion of Hakka culture, the subregion of Guangfu culture, and the core area of Chaoshan culture. High-value, numerous and widely distributed Lingnan cultural heritage sites have survived along the river thus far.

In terms of ecology, the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin is rich in water and biological resources. It is the water supply source for eastern Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Dongguan, Hong Kong and other places; furthermore, it supports economic and social activities in the northeastern region of Guangdong Province. This basin plays an important ecological role in terms of resource supply, ecological services and environmental regulation in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area and the northeastern region of Guangdong Province.

The data used in this study include land use data, road network data, water network data, elevation data and cultural heritage data from the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin. The following types of data are included:

The land use data were derived from the GlobeLand30 global land cover data from 2020 ( http://globeland30.org/ ), and three partitions—N49_20, N50_20, and N50_25—were selected.

Vector water and road network data were derived from the Open-Street Map ( https://www.openhistoricalmap.org/ ).

The 30 m resolution DEM elevation data were obtained from the Geospatial Data Cloud Platform of the Computer Network Information Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences ( http://www.gscloud.cn/search ).

Data on immovable tangible cultural heritage sites were obtained from the “Guangdong Cultural Heritage Immovable Cultural Relics List” (2013), which included attributes such as protection level, age, and heritage type of the five types of heritage objects, including grottoes and rock carvings, ancient tombs, ancient ruins, ancient buildings, and modern historical sites and buildings, within the scope of the study area. The characteristic village, town and historical trail data were obtained from “the Conservation and Utilization Master Plan for the Historical Trails in Guangdong Province” (2017). The Chinese traditional village data were derived from the “List of Chinese Traditional Villages” (first to sixth batches). Together, they constitute the data of cultural heritage sites.

Morphological spatial pattern analysis

The morphological spatial pattern analysis (MSPA) model proposed by Vogt et al. is a bias measure structural connectivity method used to identify the source and construct the resistance surface [ 39 ]. The forestland, grassland and water land types in the study area in 2020 were used as foreground data, and the MSPA method was used to divide them into seven green landscape structure types, namely, core area, islet, perforation, edge, loop, bridge and branch. According to the integral index of connectivity (IIC), the probability of connectivity ( PC ) and the delta of PC ( dPC ) in the landscape index, the patches in the core area were quantitatively evaluated [ 29 , 40 ] to determine the ecological source in the basin.

In the formula, n is the total number of patches; a i and a j are the areas of patches i and j, respectively; nl ij is the number of connections on the shortest path between patches i and j; \(p_{ij}^{*}\) represents the maximum probability of species diffusion between patches i and j; A L is the total area of the landscape; and PC remove represents the PC value after removing a patch in the study area. 0 ≤ IIC ≤ 1 and IIC = 0 indicates that there is no connection between patches, and IIC = 1 indicates that the whole landscape is connected. When 0 < PC < 1, the greater the PC value is, the greater the degree of patch connection. The greater the dPC value is, the greater the importance of the patches.

Analytic hierarchy process and composite index method

The analytic hierarchy process (AHP) refers to the decision-making method that decomposes the elements that are always related to decision-making into levels such as goals, criteria, and programs and conducts qualitative and quantitative analysis on this basis [ 41 ]. In this paper, the AHP method is used to evaluate and classify the importance of cultural heritage and the influencing factors that are resistant to the conservation and utilization of cultural ecology sources. The evaluation indices are determined as follows:

Importance of cultural heritage. The age, type and conservation level of cultural heritage sites reflect the time value, existence form and conservation value of heritage, respectively, which can reflect the importance of heritage. The number of heritage sites in the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin is large and scattered. Proximity can reflect the degree of aggregation between heritages and facilitate interaction between heritages. The scale of a heritage site can reflect the availability of cultural activities carried out by the heritage site, and the type of heritage has a direct correlation with the scale. Finally, the existence age, conservation level, proximity and area scale of cultural heritage are selected as the evaluation indices of heritage importance.

Resistance surface. From the perspective of the conservation and utilization of cultural ecology sources, the main aspects of resistance are geographical conditions and accessibility. In terms of geographical conditions, evaluation factors include elevation, slope and land use type. The greater the elevation and slope are, the greater the resistance cost. The types of land use are divided according to the intensity of human activities. The activity intensity of construction land is the highest, and the resistance cost is lower. In terms of accessibility, the evaluation factor is the distance from the main roads, rivers and historical trails. The closer the distance is to the source point, the greater the accessibility and the lower the resistance cost. Finally, the terrain, land use, road network, water network and historical trail data were selected to construct resistance factors.

The relative importance of the evaluation indicators is determined by the Delphi method. According to the selection criteria for the Delphi method of consulting experts, a total of 15 scholars and government staff members working in traditional villages and Lingnan culture research were selected; these included 2 professors, 3 associate professors, 5 government staff members and 5 researchers at the Institute of Geography. The judgment matrix is obtained through expert judgment. The weights of the two parts of the evaluation index are calculated by Yaahp 12.3, and the matrix CR is less than 0.1, which is consistent with the consistency test.

Minimum cumulative resistance

The minimum cumulative resistance (MCR) mainly refers to the minimum work or cumulative cost of simulating various landscapes with different resistance values from the “source”. This model usually combines a gravity model, mapping theory, and a connection index to evaluate and optimize ecological corridors [ 42 ]. In 2004, Yu introduced the least resistance model into the field of heritage corridors for the first time when discussing a new suitability analysis method for heritage corridors [ 43 ]. The MCR model can also help explain the distribution of biodiversity in ecosystems and provide a scientific basis for the conservation and restoration of biodiversity. In this paper, the MCR model is used to construct potential cultural-ecological corridors, connect cultural-ecological resources, and carry out conservation and utilization activities.

In the formula, D represents the distance between landscape units i and j , and R i represents the resistance coefficient of landscape unit i .

Evaluation of the corridor network structure

The network closure index (α index), network connectivity index (β index) and network connectivity rate (γ index) were used to quantitatively analyze and evaluate the structure of the constructed corridor network to determine the rationality of the network structure [ 44 ]. This paper uses the α, β and γ indices to evaluate the structural rationality of the cultural ecological corridor network system.

In the formula, the α index takes the value of [0,1]; when close to 0, no loop is formed; when close to 1, the loop in the ecological corridor network reaches the peak value. The β index takes the value of [0,3]; β > 1 means that the complexity of the corridor network structure is high; β = 1 means that only a single-loop ecological corridor network is generated; and β < 1 means that the corridor structure is single and that only a tree-like ecological corridor network is generated. The γ index takes the value of [0,1]; the larger the value is, the greater the network connectivity.

Selection of cultural ecology points

Cultural source points.

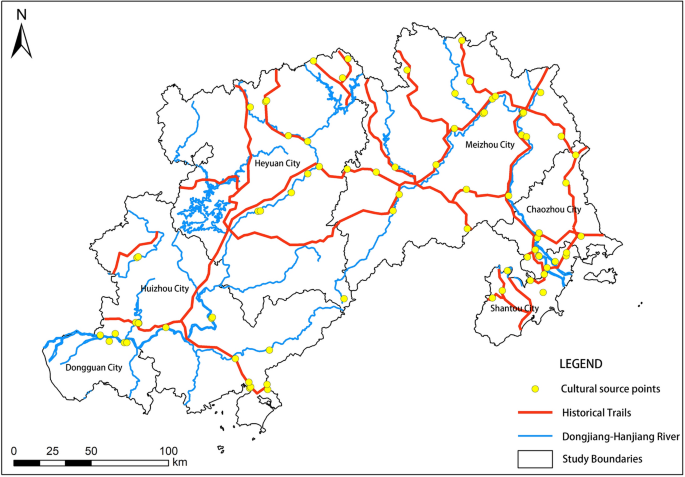

A total of 5688 tangible cultural heritages in 8 categories were investigated and organized, including grottoes and stone carvings, ancient tombs, ancient ruins, ancient buildings, modern historical sites and buildings, traditional Chinese villages, ancient cities, characteristic villages and towns (Table 2 ). The selected cultural source points should have the characteristics of high historical and cultural value, outstanding conservation value, and ease of carrying out subsequent cultural ecology activities. The four index factors, including the area scale, existence age, conservation level and proximity of the heritage site, are selected, and the factor weight is determined by the AHP (Table 3 ). A comprehensive evaluation of the importance of cultural heritage sites in the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin was carried out. According to the evaluation score, there were 1–2 general heritage sites (5015 sites), 2–3 more important heritage sites (553 sites), 3–4 important heritage sites (112 sites), and 4–5 core heritage sites (8 sites). Initially, 120 important and core heritage points were selected as representative cultural source points in the river basin. On this basis, considering the accessibility of the heritage site and the distance from the cultural route, the main rivers and historical trails in the river basin were used as the skeleton and natural substrate of the cultural route. A 2 km buffer zone was established with the help of ArcGIS to further screen 79 heritage sites as the final representative cultural source points (Fig. 2 ). The important cultural source points are located mainly in the Chaoshan area, followed by Meizhou and Heyuan cities, with fewer sites distributed in Dongguan and Huizhou cities.

Distribution of important cultural source points

Ecological sources

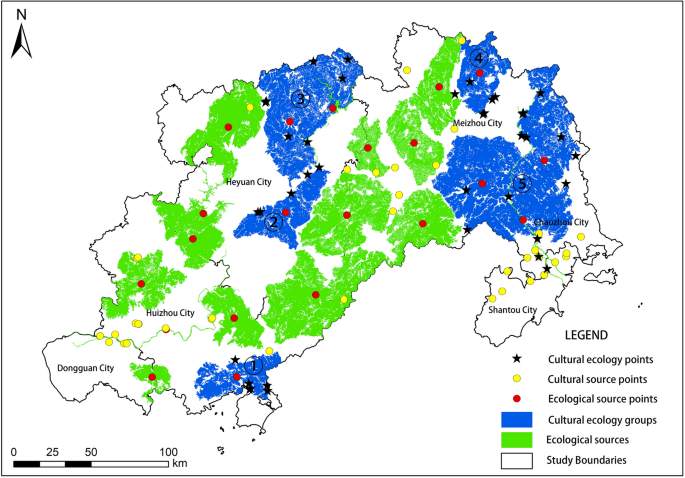

According to the MSPA, the landscape core area of the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin is 34,026.87 km 2 , accounting for 91.10% of the total ecological source area and 67.23% of the total study area. The core areas mainly distributed in Heyuan, Huizhou, Chaozhou and Meizhou city, and the landscape connectivity is good, which is conducive to the flow of biology and material. The connections to the basin are less common in Dongguan and Shantou city. The edge and perforation areas account for 3.79% and 3.64%, respectively, of the total ecological resources. There is a certain transition between the external edge and the internal edge in the core area. The proportions of islets, loops, bridges, and branches were all low, indicating that there were fewer isolated small patches in the study area and fewer channels available to alleviate internal barriers and strengthen patch connections (Table 4 ).

In the analysis of ecological sources, considering the spatial scale of the basin, the suitability of habitat patches, and the diffusion ability of wild animal composite groups, referring to Meurk’s (2017) research on Yujiang County, a 500-m patch distance threshold was set, and the connectivity probability was selected as 0.5 [ 45 ]. Through MSPA, the core area of the landscape was used as a potential ecological source. Conefor was used to evaluate the landscape connectivity of potential ecological source patches through the IIC, PC and dPC landscape indices. dPC is a representation of the importance of patches; the larger the value is, the greater the contribution of patches to the overall landscape. Referring to Chen's (2023) research on Fujian Province, 21 core areas with dPC > 1 [ 29 ] were ultimately selected as the ecological sources in the basin (Fig. 3 ). These ecological sources cover almost all important ecological control areas and scenic spots in the study area.

Distribution of ecological source points

Cultural-ecological coupling

The above cultural source points and ecological sources are coupled and analyzed. Spatially, the historical and cultural attributes and the ecological environment attributes are superimposed, and most of the cultural source points are distributed within the ecological sources; however, some are not superimposed in the surrounding areas of urban centralized construction land but are clustered.

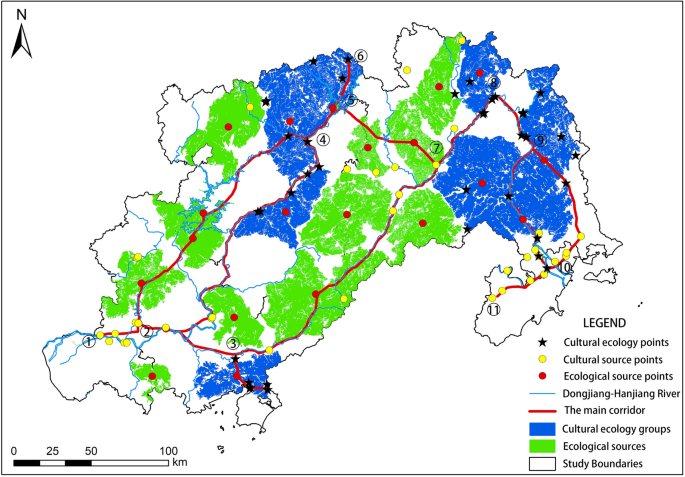

First, the number of cultural source points in a single ecological source is greater than or equal to 3, and the source is identified as a dual attribute of culture and ecology; that is, the cultural ecology group and the cultural source point in the group are regarded as the source points of cultural ecology. Second, for sources with fewer than 3 cultural sources in a single ecological source, the cultural and ecological attributes are not considered to fully overlap, and the single attribute is still maintained, that is, the cultural source and the ecological source are separated. Finally, 40 cultural ecology points, 36 cultural source points, 21 ecological sources and 5 cultural ecology groups were identified. In addition, Dongguan city and Shantou city currently lack ecological resources, but the cultural sources are more concentrated and identified as cultural groups (Fig. 4 ; Table 5 ).

Distribution of cultural ecology points

Construction of the cultural ecology corridor

Resistance surface analysis.

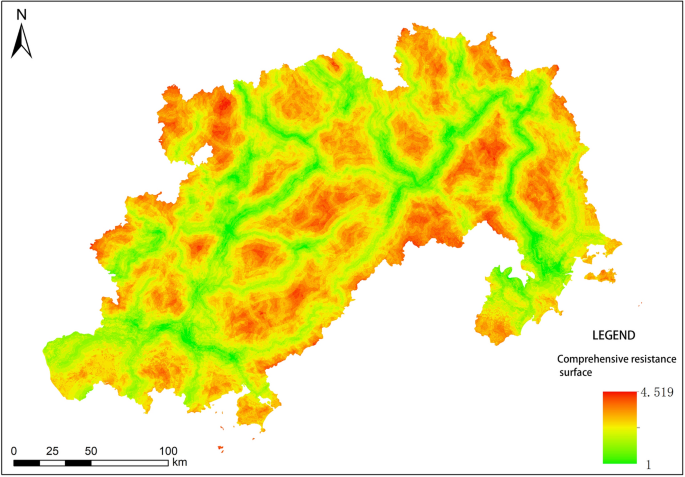

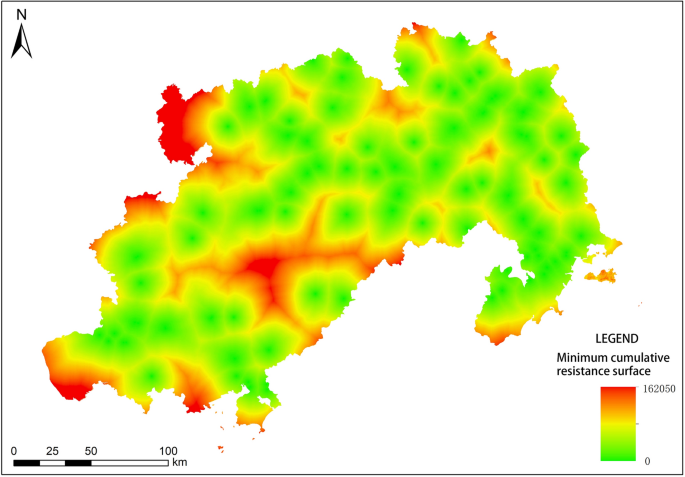

In the construction of the minimum resistance surface, the factors influencing resistance to the conservation and utilization of cultural ecology sources are considered, and the natural ecological environment and economic and social conditions in the basin are combined. Then, the elevation, slope, land use, and distance from roads, rivers and historical trails are selected to construct the resistance factor. The resistance value is set to 1–5, the 'unfavorable' method is adopted [ 46 ], and each resistance factor is assigned (Table 6 ). The AHP is used to determine the weight of factors, and the grid calculator of ArcGIS 10.8 software is used to construct the comprehensive resistance surface (Fig. 5 ). Next, based on the cultural ecology source points and the comprehensive resistance surface, the MCR is used to construct the minimum cumulative resistance surface, and the minimum resistance surface between each cultural ecology source point is calculated (Fig. 6 ).

Comprehensive resistance surface

Minimum cumulative resistance surface

Construction of a cultural ecology corridor network system

Preliminary construction and classification of the network

The MCR model is used to calculate the minimum cost route between the source points, and preliminary corridor construction is carried out according to the groups obtained from the previous analysis. Construction rules: A corridor connected to two cultural ecology groups is identified as an important corridor; a cultural ecology group and any single functional group (culture or ecology) are identified as important corridors; and two single functional groups are identified as secondary corridors. A total of 22 important corridors and 17 secondary corridors were formed. Source points were combined with highly accessible corridors to create important corridors, and the corridor with the most source points was taken as the main corridor. The relevant authorities should prioritize the implementation and construction of the main corridor. There is a strong overlap between the main corridor and the main river systems of the Dongjiang River and Hanjiang River (Table 7 ). The Dongjiang River Basin section has two rings, namely, the “Dongguan-Heyuan Dongjiang Corridor Ring” and “Huizhou-Heyuan-Meizhou Dongjiang Corridor Ring”, which include Pingtan Town, Meizhou Ancient City, Tuocheng Ancient City, Luofu Mountain, Fengshuba Nature Reserve and other important cultural ecology sources. The Hanjiang River Basin contains two parts, namely, the “Meizhou-Chaozhou Hanjiang Corridor Ring” in the north-central region and the “Shantou Hanjiang Corridor” in the southern region, including Songkou town, Dapu County, Dahao Ancient City, Yinna Mountain, Xiyan Mountain and other important cultural ecology sources.

Finally, a preliminary map of the cultural ecology corridor in the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin was generated (Fig. 7 ). The preliminary analysis showed that the important corridors were mainly distributed in the central and eastern regions of the basin and were in line with the cultural ecology groups. The secondary corridors further enhanced the connectivity of various cultural ecology patches in the basin.

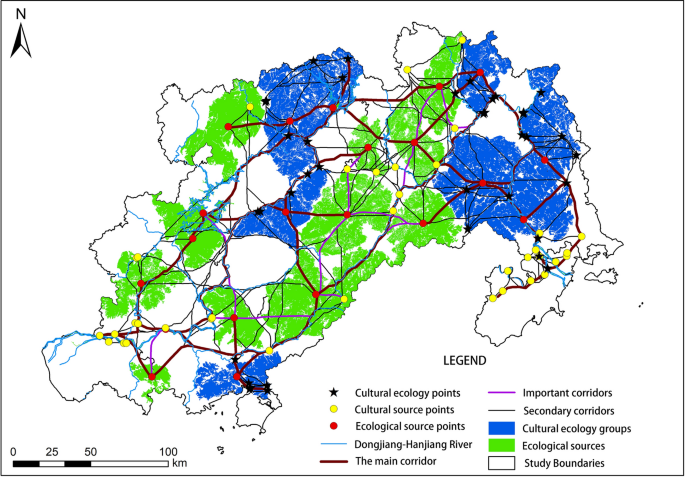

Improvement of the network

The main cultural ecology corridor

On the basis of the preliminary construction and classification of cultural ecology corridors, it is also necessary to construct a general corridor between the source points in each remaining patch, forming the structure of the main network and the branches of the nerve endings, to improve the completeness of the network. These general corridors connect cultural source points, ecological sources, cultural ecology source points and patch groups to form a complete cultural ecology corridor network (Fig. 8 ). The construction of this network is conducive to improving the information and material exchange of cultural and environmental elements in the basin and promoting the connectivity of cultural routes and ecosystems between regions.

Analyzing the network structure

The cultural ecology corridor network

The number of potential cultural ecology corridors in the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin is L = 1231, and the number of corridor nodes is V = 537. This basin includes 1 main corridor, 22 important corridors and 17 secondary corridors. The α, β, and γ indices were used to analyze and evaluate the generated cultural ecology corridor network structure and showed that α = 0.65, β = 4.58, and γ = 0.77, indicating that the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin has formed a composite network structure with many corridors, good connectivity and high density, which is conducive to the comprehensive overall conservation and interaction of culture and ecology.

In the 1980s, the United States of America proposed the conservation and utilization of canal areas via the heritage corridor model. The heritage corridor includes four constituent elements: green corridors, walking trails, heritage sites, and interpretation systems. It emphasizes the conservation of the natural environment and the lining and linking of cultural heritage; this conservation method pursues the multiple objectives of heritage preservation, regional revitalization, residents' recreation, cultural tourism and education [ 47 ]. Currently, heritage corridor research focuses on corridor construction methods, industrial development, tourism development, and conservation and management [ 26 , 27 , 28 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 ]. However, studies on the comprehensive conservation and utilization of corridors are rare. This paper draws on the practical operation of heritage corridors. On the basis of the cultural ecology corridors in the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin, the construction of cultural landscape nodes assists with the development of cultural ecology services, large-scale co-construction, co-governance-sharing working mechanisms, and a corridor-based cultural-ecology economy. This will further promote the utilization of cultural heritage, natural ecological restoration, regional coordination and development and promote regional economic and social development through the conservation and utilization of cultural and environmental resources.

In addition, the overall conservation awareness induced by cultural heritage and its combination with the environment has been widely valued by scholars. However, the integration of culture and environment, culture and regional economic and social development, and the regional, holistic and multimodal conservation and utilization of cultural heritage sites need to continue to be supported by related research and discussion. The comprehensive construction of the cultural ecology corridor system in this paper, on the one hand, is a solution to the three discussion questions; on the other hand, this is in line with China's current national policy requirements for building a cultural power and harmonious coexistence between humanity and nature.

Developing cultural ecology services and inheriting Lingnan culture

Cultural landscape nodes should be built. The cultural ecology source point is combined with its surrounding character stories, folklore, rituals, food and other content to create a "cultural landscape node" that integrates the elements of "material culture + natural ecology + nonmaterial culture" to promote the conservation and utilization of cultural heritage. We will construct a system of “slow paths (multiple linear carriers such as historical trails, greenways, scenic roads, and blue roads), interpretation and education, and recreation and experience” in the cultural ecology corridors of the river basin. Through the systematic coordination of cultural and ecological resources, we will promote the recreational, ornamental, and research activities of cultural landscape nodes in the corridor.

Historical stories, architectural features, village development, folk culture and other content along the corridor are clarified to educate and disseminate Lingnan culture, improve the public's understanding of the traditional culture of Chaoshan and Hakka cultures, and promote 'holistic' conservation and utilization of cultural heritage.

Enhancing ecological connectivity and the repair of natural ecosystems

Dongguan and Shantou should be added as ecological sources, and ecological corridors were restored. In 2021, China proposed the idea of systematic management of mountains, rivers, forests, fields, lakes and sands, with river basins serving as the main unit. The ecological sources of Dongguan and Shantou in the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin are relatively lacking, and additional additions are recommended: in the Dongguan area, the corresponding locations are Dalingshan Forest Park and Lianhuashan Country Park; in the Shantou area, the corresponding sites are the Dafeng Scenic Area and Xihuanshan Forest Park. Through natural restoration, artificial restoration and external constraints, the ecological service quality of the two ecological sources is gradually improving, and on this basis, the ecological corridor is further supplemented. Moreover, ecological resources such as mines, ecological forests and waterfront landscape belts around the corridor are being continuously restored, and 44 ecological breakpoints caused by urban construction have been repaired to ensure animal migration and network connectivity.

Cultural ecology-sensitive areas should be established to restore biodiversity. The cultural ecology-sensitive areas are set around the cultural ecology corridors, of which the main corridors and important corridors are set to be no less than 1 km and the secondary corridors are set to no less than 0.8 km. The sensitive area of cultural ecology is the intersection of human activities and wildlife migration, habitat and activities in villages and towns. These corridors control urban construction, production and living activities in sensitive areas and create good migration and living environments for wildlife.

Developing the “corridor cultural ecology economy” and promoting the development of villages and towns along the route

The development momentum should be transformed, and a corridor-based cultural ecology economic belt built. The slow path, interpretation and education, recreation and experience systems of cultural ecology corridors are inseparable from the conservation and utilization of hotels, restaurants, transportation and other commercial and service facilities in villages and towns along the line. The construction of a cultural ecology service system, the construction of a corridor cultural ecology economic belt, and the promotion of economic and social development of villages and towns along the corridor are important. Taking the villages and towns passing by the main corridor as the key construction areas in northeast Guangdong, we should strengthen the delivery of resources, the supply of facilities and the restoration of ecology; vigorously develop cultural ecology recreation, viewing, research and other activities around the cultural landscape nodes; develop a modern cultural ecology industrial system; and build a demonstration area for coordinated urban and rural development.

Establishment of the department of natural ecology and cultural heritage of Guangdong Province: co-construction, co-governance and sharing of cultural ecology resources

A large-scale co-construction, co-governance and sharing working mechanisms that breaks through administrative boundaries and eliminates the local monopoly of resources should be established. A department of natural ecology and cultural heritage for Guangdong Province should be established as part of the provincial government to coordinate the provincial cultural heritage and natural ecological protection areas. On this basis, in view of cultural heritage conservation and utilization, natural ecological restoration, regional coordination and development of the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin, the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin Cultural Ecology Corridor Management Committee has been established. This committee is responsible for the investigation and registration of cultural ecology resources and the construction and management of cultural ecology corridors (Table 8 ); additionally, it bypasses the constraints of administrative boundaries, realizes the conservation and utilization of cross-regional and large-scale cultural ecology corridors at the basin level and promotes the cross-regional flow of resources.

Conclusions

The Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin represents the substantial cultural and ecological value of both Guangdong Province and China. First, the cultural heritage source points and ecological sources in the basin are extracted via heritage importance evaluation and MSPA. On this basis, spatial coupling of cultural and ecological elements is carried out to determine the source of cultural ecology to ensure the full coverage of important cultural and ecological elements. Finally, 40 cultural ecology composite sources, 36 cultural source points, 21 ecological sources, 5 cultural ecology groups and 2 cultural groups were identified. On this basis, the MCR model, which is based on the conservation of cultural ecology elements and the development of cultural ecology activities, is used to construct the cultural ecology corridor network system via the 'unfavorable' method; this system includes 1 main corridor, 22 important corridors and 17 secondary corridors. The α, β and γ indices are used to analyze and evaluate the corridor network structure, and α = 0.65, β = 4.58, and γ = 0.77 indicate that the number of corridors is large, the connectivity is good, and the density is high, which is conducive to the comprehensive overall conservation and interaction of culture and ecology.

This study can supplement unilateral regional research on culture and ecology at home and abroad and provide an in-depth application of cultural ecology theory in the construction of the cultural ecology corridor of the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin by coupling cultural ecology source points, establishing a cross-regional and large-scale cultural ecology network, integrating regional culture and ecological resources, dismantling the “classification” discussion of cultural heritage used in the past, and discussing the adaptability, variability and integrity of culture and ecology. In addition, the selection of cultural source points overcomes the disadvantages of determining source points by considering a single heritage point or by performing a kernel density analysis of cultural clusters; moreover, this paper comprehensively considers the importance, availability and proximity of heritage sites, which is conducive to strengthening the operability of heritage conservation and utilization. This approach is also conducive to strengthening the continuity and integrity of the ecological environment between heritage sites. The article further proposes that, based on the cultural ecology corridor, through the construction of cultural landscape nodes and cultural ecology services, the development of the corridor’s cultural ecology economy, the establishment of large-scale co-construction, co-governance, and shared working mechanisms, etc., will overcome the constraints of administrative boundaries and realize the multimodal and large-scale conservation and utilization of heritage. This study has strong theoretical and practical significance in both content and methods for research in this field and represents a new contribution to the research area of Lingnan culture inheritance, ecosystem restoration, and economic and social development of villages and towns along the line.

The researchers hope to use the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin as a pilot to carry out the value realization mechanism of cultural ecology products and use the rich Lingnan culture and ecological resources in the basin to create a base for understanding the conservation and economic value of Chinese cultural ecology. At both the national and international levels, these actions address current human conservation and construction requirements for better cultural and ecological environments; furthermore, they are important for achieving sustainable development.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Pang F, Shi C. A study of important discourses on the protection and utilization of historical and cultural heritage. Hunan Soc Sci. 2022;01:156–63.

Google Scholar

Zhang Y, Yuan X, Zhang H, Wang Y. We will protect the eternal roots of the Chinese national spirit. People's Daily 2022,03-20(001).

Zhang S. Urban conservation planning: from historic environments to historic urban landscapes. Beijing: Science Press; 2020.

Huang Y, Shen S, Hu W, Li Y, Li G. Construction of cultural heritage tourism corridor for the dissemination of historical culture: a case study of typical mountainous multi-ethnic area in China. Land. 2023;12:138.

Article Google Scholar

Wen Y. Semantics of authenticity and cultural ecology model of heritage. City Plan Rev. 2022;46(3):115–24.

Li J, Shan M, Qi J. Coupling coordination development of culture-ecology-tourism in cities along the grand canal cultural belt. Econ Geogr. 2022;42(10):201–7.

Deng W, Hu H, Yang R, He Y. A study on the dual-structure characteristics of traditional rural settlements and implications. Urban Plan Forum. 2019;06:101–6.

Shao Y, Hu L, Zhao J. Integrated conservation and utilization of historic and cultural resources from the regional perspective—the case of Southern Anhui. Urban Plan Forum. 2016;03:98–105.

Zhang D, Zhang W, Chen D. Analysis and exploration of the concept of traditional settlement protection and development cluster mode in the new period. Urban Dev Stud. 2022;29(04):16–21+39.

Chen X, Yan H. The rural spatial planning under the construction of territorial spatial planning system—take Jiangsu as an example. Urban Plan Forum. 2021;01:74–81.

Yang J. Protection of urban and rural cultural heritage based on cultural ecology and complex system. City Plan Rev. 2016;40(04):103–9.

Zhang B. Historic urban and rural settlements: a new category towards regional and integral conservation of cultural heritage. Urban Plan Forum. 2015;06:5–11.

CAS Google Scholar

Zhang S, Liu J, Pei T, Chan C, Wang M, Meng B. Tourism value assessment of linear cultural heritage: the case of the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal in China. Curr Issues Tour. 2021;1–23.

Conzen MP, Wulfestieg BM. Metropolitan Chicago’s regional cultural park: assessing the development of the Illinois & Michigan Canal National Heritage Corridor. J Geogr. 2001;100:111–7.

Murray M, Graham B. Exploring the dialectics of route based tourism: the Camino de Santiago. Tour Manag. 1997;18:513–24.

ICOMOS. International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (Venice Charter) [EB/OL]. https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/venice_e.pdf .

UNESCO. Recommendation concerning the Safeguarding and Contemporary Role of Historic Areas. [EB/OL]. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0011/001140/114038e.pdf#page=136 .

ICOMOS. Charter for the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas (Washington Charter) [EB/OL]. https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/towns_e.pdf .

ICOMOS. The Valletta Principles for the Safeguarding and Management of Historic Cities, Towns and Urban Areas (Valletta Principles) [EB/OL]. https://civvih.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Valletta-Principles-GA-_EN_FR_28_11_2011.pdf .

Steward JH. Theory of culture change. University of Illinois Press, Urbana. 1979, vol. 7, pp. 39–40.

Jiang J. Discussion on the theory framework of cultural ecology. Hum Geogr. 2005;04:119–24.

Zhang S. Research on the regional integrated conservation strategy for cultural ecology: a case study of Huizhou Cultural Ecology Zone. J Tongji Univ Soc Sci Sect. 2009;3:2735.

ADS Google Scholar

Head L. Cultural ecology: the problematic human and the terms of engagement. Prog Hum Geogr. 2007;31(6):837–46.

Ma J. A review of studies on cultural ecology in China in recent ten years. Hunan Soc Sci. 2011;1:26–31.

Kent M. Cultural Landscape and ecology 1995–96: of oecnmenics and nature. Prog Hum Geogr. 1998;22(1):115–28.

Severo M. European cultural routes: building a multi-actor approach. Mus Int. 2017;69:136–45.

Boley BB, Gaither CJ. Exploring empowerment within the Gullah Geechee cultural heritage corridor: implications for heritage tourism development in the lowcountry. J Herit Tour. 2016;11:155–76.

Shao Y, Huang Y. Planning and governance of regional historical and cultural space conservation and development: a case study of the Loire Valley in France. Urban Plan Inter. 2022;37(04):111–21.

Chen J, Zhao C, Zhao Q, Xu C, Lin S, Qiu R, Hu X. Construction of ecological network in Fujian Province based on Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis. Acta Ecol Sin. 2023;43(2):603–14.

Connell J. Film tourism—evolution, progress and prospects. Tour Manag. 2012;33(5):1007–29.

Tao L, Wang H, Li J, Zhang L. Construction of CCSPM model for spatial definition of cultural corridor: a case study of cross-border cultural corridor in Southwest Yunnan. Sci Geogr Sin. 2022;42(4):602–10.

Liu P. Traditional settlement cultural landscape gene: deep understanding of the genetic map of traditional settlement landscape. Beijing: The Commercial Press; 2014.

Yin L, Liu P, Li B, Qi J, Hu Z. Map of traditional settlement landscape morphology gene: a case study of the Xiangjiang River Basin. Sci Geogr Sin. 2023;43(6):1053–65.

Hu Z, Liu P, Deng Y, Zheng W. A novel method for identifying and separating landscape genes from traditional settlements. Sci Geogr Sin. 2015;35(12):1518–24.

Wang F, Jiang Ch, Wei R. Cultural landscape security pattern: concept and structure. Geogr Res. 2017;36(10):1834–42.

Wang F, Prominski M. Urbanization and locality: strengthening identity and sustainability by site-specific planning and design. Heidelberg: Springer; 2016.

Book Google Scholar

Pan Y, Zhuo X. Comparative study on traditional settlement patterns of Guang-fu Area and Chao-Shan Area. South Arch. 2014;03:79–85.

Sun Y, Wang Y, Xiao D. The spatial distribution and evolution of Hakka traditional villages on GlS in Meizhou Area. Econ Geogr. 2016;36(10): 193200.

Vogt P, Riitters KH, Estreguil C, Kozak J, Wade TG, Wickham JD. Mapping spatial patterns with morphological image processing. Landsc Ecol. 2007;22:171–7.

Saura S, Pascual HL. A new habitat availability index to integrate connectivity in landscape conservation planning: comparison with existing indices and application to a case study. Landsc Urban Plan. 2007;83:91–103.

Deng X, Li J, Zeng H, Chen J, Zhao J. Research on computation methods of AHP wight vector and its applications. Math Prac Theory. 2012;42(07):93–100.

Lookingbill TR, Elmore AJ, Engelhardt KA, Churchill JB, Gates JE, Johnson JB. Influence of wetland networks on bat activity in mixed-use landscapes. Biol Conser. 2010;143:973–83.

Lin F, Zhang X, Ma Z, Zhang Y. Spatial structure and corridor construction of intangible cultural heritage: a case study of the Ming great wall. Land. 2022;11:1478.

Chen Z, Kuang D, Wei X, Zhang L. Developing ecological networks based on MSPA and MCR: a case study in Yujiang County. Resour Environ Yangtze Basin. 2017;26:1199–207.

Meurk CD, Chen C, Wu S, Lu M, Wen Z, Jiang Y, Chen J. Effects of changing cost values on landscape connectivity simulation. Acta Ecol Sin. 2015;35:7367–76.

Li W, Yu K, Li D. Theoretical framework of heritage corridor and overall conservation of the great canal. Urban Probl. 2004;01:28–31+54.

Oikonomopoulou E, Delegou ET, Sayas J, Moropoulou A. An innovative approach to the protection of cultural heritage: the case of cultural routes in Chios Island, Greece. J Archaeol Sci Rep. 2017;14:742–57.

LaPoint S, Gallery P, Wikelski M, Kays R. Animal behavior, cost-based corridor models, and real corridors. Landsc Ecol. 2013;28:1615–30.

Zhang D, Feng T, Zhang J. Discussion on the construction of heritage corridors along Weihe River system in Xi’an Metropolitan Area. Chin Landsc Arch. 2016;32:52–6.

MathSciNet Google Scholar

Byrne D. Heritage corridors: transnational flows and the built environment of migration. J Ethn Migr Stud. 2016;42:2360–78.

Xi X, Chen L. The preservation and sustainable utilization approach of the American Erie canal heritage corridor and its inspirations. Urban Plan Inter. 2013;28(04):100–7.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the research group for the financial support and the reviewers for their useful comments and suggestions.

"Chaozhou Culture Research Special Project": Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Project of Guangdong Province in 2023 (GD23CZZ03).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Culture Tourism and Geography, Guangdong University of Finance and Economics, Guangzhou, 510320, China

Ying Sun, Zhiwei Wei, Jialiang Li & Xi Cheng

Jiantong Design Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, 510010, China

Yushun Wang

School of Mechanics and Construction Engineering, Jinan University, Guangzhou, 510632, China

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

YS, conceptualization, methodology, investigation, funding acquisition, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; YSW, methodology, investigation, writing—review and editing. LLL, conceptualization, methodology, investigation. ZWW, methodology, software, writing—original draft, visualization, validation; JLL and XC, data curation, software, visualization, validation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yushun Wang .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors of this article declare no potential competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Sun, Y., Wang, Y., Liu, L. et al. Large-scale cultural heritage conservation and utilization based on cultural ecology corridors: a case study of the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin in Guangdong, China. Herit Sci 12 , 44 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01162-z

Download citation

Received : 07 September 2023

Accepted : 27 January 2024

Published : 06 February 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01162-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cultural ecology

- Corridor network system

- Lingnan culture

- Member Directory

- Jobs

Celebrate With Us

- Discover our 2024 Award Recipients!

- Learn more about our awards and the nomination processes

Climate Resilience

- Discover how climate change may impact your site and develop resilience strategies with our newly-launched Climate Resilience Resources for Cultural Heritage.

Support FAIC

- The Foundation supports emergency response, free collection resources, and moderated forums for nearly 20,000 people!

- Donate today!

What is Conservation?

The profession that melds art with science to preserve cultural material for the future. Conservation protects our heritage, preserves our legacy, and ultimately, saves our past for generations to come.

Foundation for Advancement in Conservation

We conduct conservation education, research, and outreach activities through the Foundation for Advancement in Conservation, which specifically supports the care of collections and assists with disaster preparedness and response. Learn how to support our work.

Professional Development & Continued Education

We promote material and technological expertise in the mastery of conservation techniques and are dedicated to sharing that knowledge with the conservation field and allied professions through research and continued education.

- Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Accessibility

Our core values include equity, inclusion and access, and we are committed to increasing diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility (DEIA) throughout both organizations. Learn more about our key DEIA initiatives.

- Land Acknowledgement

Our headquarters are in Washington, DC, the ancestral home of the Piscataway Conoy Tribe, Piscataway Indian Nation, the Nacotchtank People, and other Chesapeake Indigenous Tribes. Read our full acknowledgement.

Update your information

Search Members

Connect with colleagues

See what we offer

- Advocate for Conservation

You are the voice for cultural materials preservation. Advocate for public policy that values the enduring evidence of human imagination, creativity, and achievement. Join our efforts.

Friends of Conservation

Conservators play a vital role in protecting and preserving the art, objects, and historic sites that tell the story of our lives. Become a Friend to support their work and learn how conservation affects the world around us.

Emergency affecting your collection?

Get immediate assistance from our team of National Heritage Responders.

- Board of Directors

- Internal Advisory Group

- 2024 Election Slate

- Our History

- Held in Trust Report

- Areas of Study

- Held in Trust Project Updates

- Held in Trust Project Groups

- Life Cycle Assessment

- Climate Resilience Resources

- Join Friends of Conservation

- Our Supporters

- Planned Giving

- Logos & Rules for Use

- Press Release Archives

- Conservation Terminology

- Conservation Specialties

- Ask a Conservator Day

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Related Organizations

- Pre-program

- Post-graduate

- Continued Education

- Our Code of Ethics

- Caring for Belongings

- Find a Professional

- Post Graduates

- Institutions

- Professional Membership

- Awards & Honors

- Communications

- Education & Training

- Affinity Groups

- Ethics & Standards

- Financial Advisory

- Health and Safety

- Membership Designations

- Member Engagement

- Sustainability

- Ethics Core Documents Review Task Force

- Archaeological Heritage Network

- Member Community

- Architectural Conservation Wiki

- About the BPG

- BPG Executive Council Responsibilities

- BPG Education & Programs Committee

- BPG Nominating Committee

- BPG Publications Committee

- BPG Discussion Groups

- Get Involved

- BPG Guidelines

- Business Meeting & Program

- Art on Paper Discussion Group

- Library and Archives Conservation Discussion Group

- Author Index

- Title Index

- Grants and Scholarships

- Networks & Allied Groups

- Online Community

- Conservators in Private Practice Group

- Publications

- Optical Media Pen

- Electronic Media Review

- Standing Charge

- Current Officers

- Network Structure & History

- Update from the Chair

- Liaison Program News

- Archived News

- ECPN at the Annual Meeting

- Liaison Program

- Digital Programs

- ECPN-CIPP Mentorship Program

- Pre-Program Internships

- Specialty Groups

- International Education

- Tips Sheets

- Informational Materials

- Compensation Resources

- Relevant AIC Resources

- ECPN on the AIC Blog

- AIC Wiki: Resources for Emerging Conservation Professionals

- AIC News Articles

- Conference Posters

- How to Get Involved

- Articles & Guides

- Historic House Hazards

- Outreach Resources

- Paintings Specialty Group

- Albumen: History, Science,Preservation

- Coatings on Photographs Book

- Photographic Materials Conservation Wiki

- Guide to Digital Photography and Documentation

- JAIC Articles

- Photographic Print Sample Sets

- Photographic Information Record

- Platinum and Palladium Photographs Book

- Topics in Photographic Preservation

- Preventive Care Network

- Imaging Working Group Community

- Achievement Award

- Become a Member

- Rules of Order

- WAG Postprints

- Annual Meeting

- Volunteer Opportunities

- Professional Development Grants & Scholarships

- Publication Fellowships

- Outside Funding Sources

- Emergency Grants

- External Courses

- REALM Project

- Current Response Efforts

- Disaster Response & Recovery Guides

- Plan an Alliance for Response Forum

- Build Relationships with Emergency Responders

- Develop a Local Assistance Network

- Engage Your Network with Education, Training, and Activities

- Find Support for Network Projects

- Leadership Events

- Berks-Lehigh-Northampton

- Central Pennsylvania

- Central Virginia

- Massachusetts

- Mississippi Gulf Coast

- New Orleans

- New York Capital Region

- New York City

- North Carolina

- Northeast Pennsylvania

- Northwest Pennsylvania

- Philadelphia

- Sarasota Manatee

- South Central Pennsylvania

- South Florida

- Suburban Philadelphia

- U.S. Virgin Islands

- Washington D.C.

- Past Responses

- Deployment Procedures

- Risk Evaluation and Planning Program

- Getting Ready in Indian Country

- Emergency Planning Toolkit for Tribal Cultural Institutions

- Connecting to Collections Care

- Eligibility

- Meeting the Match

- Participating Museums

- Funding Resources

- State Grants

- Assessor Resources

- Assessor FAQs

- Emergency CAP

- Outreach Resources for Members

- Language Hub

- Climate and Sustainability

- Registration Policies

- Refund Policy

- How to Register Online

- Green Attendee Pledge

- 2024 Virtual Access

- Attendee Information

- Speaker Information

- Call for Submissions

- Exhibitor Packages

- Sponsor and Advertise

- Exhibitor Policies

- Accommodations & Travel

- Future Meetings

- Program and Schedule

- 2023 Posters

- Exhibit Hall

- Support Florida Organizations

- 2022 Posters

- Meet the Exhibitors

- 49th Virtual Annual Meeting (2021)

- 48th Virtual Annual Meeting (2020)

- 47th Annual Meeting in New England (2019)

- 46th Annual Meeting in Houston (2018)

- 45th Annual Meeting in Chicago (2017)

- 44th Annual Meeting in Montreal (2016)

- 43rd Annual Meeting in Miami (2015)

- Earlier Meetings

- Past Events

- Propose a Professional Development Program

- Code of Conduct

- Current Issue

- Style Guide

- Tips for Preparing Articles and Notes

- Special Call for Papers

- Common Misconceptions About Publishing in JAIC

- Past Issues

- Editorial Policy

- Content Schedule

- Lead Article Lineup

- Digital Products

- Shippable Products

- Annual Conference Publications

- Global Conservation Forum

- Social Media

- Survey Reports

- CoOL, Blog, & Wiki

- Advertise with Us

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.6(1); 2022 Jan

Heritage Conservation Future: Where We Stand, Challenges Ahead, and a Paradigm Shift

Jorge otero.

1 Department of Mineralogy and Petrology, University of Granada, Fuentenueva s/n, Granada 18002 Spain

Global cultural heritage is a lucrative asset. It is an important industry generating millions of jobs and billions of euros in revenue yearly. However, despite the tremendous economic and socio‐cultural benefits, little attention is usually paid to its conservation and to developing innovative big‐picture strategies to modernize its professional field. This perspective aims to compile some of the relevant current global needs to explore alternative ways for shaping future steps associated with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. From this perspective, it is conceptualized how emerging artificial intelligence (AI) and digital socio‐technological models of production based on democratic Peer‐2‐Peer (P2P) interactions can represent an alternative transformative solution by going beyond the current global communication and technical limitations in the heritage conservation community, while also providing novel digital tools to conservation practitioners, which can truly revolutionize the conservation decision‐making process and improve global conservation standards.

Cultural heritage is a lucrative asset. However, despite its tremendous worldwide economic and socio‐cultural benefits, little attention is usually paid to reflect on novel big‐picture strategies to modernize the conservation field. This perspective reviews some of the relevant current global challenges and conceptualizes how emerging digital‐social‐movements based on Peer‐2‐Peer interactions can represent a truly transformative solution to go beyond current needs.

1. Introduction

Cultural heritage refers to the legacy of tangible items (i.e., buildings, monuments, landscapes, books, textiles, paintings, or archaeological artifacts) and their intangible attributes (i.e., folklore, traditions, language, or performance arts) that are inherited from the past by a group or society and conserved for future generations due to their artistic, cultural, or historic value. [ 1 ] The act of preserving cultural heritage is known as Heritage Conservation, and it mostly focuses on doing everything possible to delay the natural laws of deterioration on tangible items to guarantee the transmission of its significant heritage messages and values for future generations. Current heritage conservation practice activities, which are mostly carried out by conservation practitioners (i.e., conservators–restorers and conservation technicians) in worldwide museums, conservation laboratories and monuments; widely involve activities such as the implementation of preventive actions (i.e., controlling the surrounding environmental conditions of items to mitigate damage), remedial activities (i.e., applying a conservation treatment to strengthen item's properties) or the application of a restoration process to bring decayed items as nearly as possible to their former condition. Conservation scientific research activities, which are mostly carried out by conservation scientists in worldwide universities and heritage research institutions, support the conservation practice providing scientific advances in the characterization of materials, the investigation of the material's degradation phenomena and the development of materials and technologies for their conservation and restoration. [ 2 ]

Cultural heritage represents nowadays one of the most important global industries and a substantial economic benefit for host countries, regions, and local communities. According to the latest studies made by the World Travel and Tourism Council, in 2019, cultural tourism represented 40% of all European tourism, generating 319 million jobs and producing more than 30 billion € in revenues every year. [ 3 ] Besides the economic asset and tourist attraction, cultural heritage also has a significant value as an identity factor contributing to social cohesion. [ 4 ] Despite the tremendous economic and socio‐cultural benefits, little attention and investment are usually taken on its conservation and/or to develop new strategies to modernize its practice activities. Machu Picchu, Taj Mahal, Petra or Angkor, among many other monuments with irreplaceable cultural heritage significance, are currently eroding at a noticeable rate [ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ] and current global conservation activities are not completely succeeding in the implementation of quality conservation strategies to stop damage. [ 9 ] According to the latest heritage at risk report made by ICOMOS in 2020, [ 10 ] ≈65% of the world's buildings with artistic and/or cultural interest currently present lack of maintenance and are in a poor state of conservation, which leads structures to a constant loss of its cultural, artistic, and economic value. Such loss has drawn recently the attention of the international political community, which has recognized the need to safeguard this heritage, as represented by one of the 169 specific targets of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 11.4). Inadequate environmental conditions, climate change, the massification of tourism, and insufficient management and resources are nowadays the major conservation threats to World Heritage Sites. [ 11 ] Considering that the cultural tourism industry has been globally growing, at a rate of 20–25% in the last 10 years before the COVID‐19 pandemic eruption, [ 12 ] added to the effect of global warming and the current high levels of pollution in urban areas, the decay of heritage items is expected to increase considerably in the next 10 years. [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ] This rapid deterioration is expected to be even more exacerbated in developing countries since conservation activities are often carried out by inexpert and/or untrained practitioners [ 18 ] which, in several cases, can increase damage up to 50%. [ 19 ] In this context, there is a pressing need to envision innovative solutions to develop different global strategies to go beyond the current global challenges in the heritage conservation community for better conservation outcomes and to continue enjoying the tremendous economic benefits derived from heritage more efficiently and sustainably for the benefit of global future generations.

On the other hand, cultural heritage conservation can also serve as a worldwide economic driving force, but especially in economically and socially marginalized communities in developing countries since it helps to generate local jobs, creation of opportunities for income‐generation and jobs (especially for youth and women), better learning opportunities for all, reducing inequality between social status or communities, improving professional competitiveness in skilled jobs and promoting cooperation between stakeholders and professional entities, increase tourism, and improve the quality visitor experience. [ 20 ] Besides the economic growth in developing countries, cultural heritage conservation enables sustainable development by enhancing the inhabitants’ sense of identity, feeling of connection, and improves people's well‐being. [ 21 ]

This communication aims to assemble some of the current global challenges in heritage conservation and propose an alternative paradigm for shaping up future steps associated with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

2. Global Challenges Ahead in Heritage Conservation

2.1. analysis of the heritage conservation scientific data.

The ability to uncover insights and trends in large amounts of data has been around since ancient times. Ancient Egyptians used the analysis of data to increase efficiency in tax collection or accurately predict the flooding of the river Nile every year. [ 22 ] However, data science, or “big data analysis,” has especially emerged in the last decade as a key new area of study having a tremendous impact in other scientific areas such as biology, medicine, or the development of smart‐green cities, which is able to extract new value from large complex unstructured data coming from differences sources. [ 23 , 24 , 25 ] The interest to study heritage materials is an old field of research, which started back in the XIX century where scientists such as Michael Faraday (1791–1867), [ 26 ] Friedrich W. Rathgen (1862–1942), [ 27 ] or A. W. von Hofmann (1818–1892) [ 28 ] had already drawn the attention to the study of the degradation phenomenon of heritage materials. However, to date, there has not been a single work on any macroperspective analysis or data science applied to the understanding and management of the conservation data from heritage. This is surprising especially for three reasons: i) studies of the heritage conservation are incredibly data‐rich and spread in a vast number of sources; ii) current research is still progressing without macroperspective directions; iii) most excellent scientific findings lack nowadays the adequate dissemination and are rarely transferred into practice.

I believe that, at this point, heritage conservation data requires the appropriate analysis in order to derive meaningful information crucial to help scientists and conservation research institutions to find new key areas of research and optimize research activities. At this point, should the emphasis of heritage conservation be placed on the development of new materials and new application procedures? Are most of the damage mechanisms already precisely understood and linked to visible decay patterns? Has there been significant uncover work that needs to be transferred to real practice? Have similar studies obtained similar results? Are the techniques and methods for evaluating heritage materials and decay processes accessible to conservation practitioners and is this methodology universally accepted by the scientific community? Can this methodology and findings be implemented by conservation practitioners also in developing countries? Does science need to provide more research to evaluate the long‐term durability of treatments? etc. In this light, I believe there is an urgent need to analyze the existing scientific data before continuing with more incremental research data to evaluate the direction in which research has been progressing and whether or not the current direction is proving fruitful.

But, how can we tackle such complex and macroscopical analysis? Big data technologies (software and data warehouse), together with the increased use of cloud‐based, high‐performance computing (algorithms), and artificial intelligence (AI), can create new opportunities for data analysis with tremendous benefits to any multidisciplinary and data‐rich fields as health, [ 29 ] history, [ 30 ] or even heritage conservation. [ 31 ] However, although these big data technologies could be very useful to extract unknown correlations, detect hidden patterns, detect areas of overproduction, areas that lack research or help us to obtain similarities or differences on similar projects, [ 32 ] those algorithms have currently difficulties to establishing qualitative analyses to highlight crucial findings, which can help us answer the mentioned questions; especially considering diverse and complex environments, [ 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ] such as the conservation of cultural heritage, which requires frequently the consensus/input of professionals with very different angles based on diverse expertise, context, and environments. Moreover, considering that the big data analysis is usually carried out by only one researcher or by a selected group of experts, this analysis has been found to be highly unconsciously biased by the researcher's previous experience/scientific position and often this big data analysis is not unanimously accepted on multidisciplinary environments involving different fields, academic positions, and research interests. [ 37 , 38 , 39 ] So, how can we provide the first step to create a summary of the conservation existing scientific findings that could be accepted consensually by both its scientific and practice community?

2.2. Reduce Inequalities: Bridge the Gap between Developed and Developing Countries

Scientific journals are still nowadays the principal channel for disseminating research results across the global scientific community. However, access to those scientific journals is highly expensive and also restricted to some developing countries, which is called by UNESCO “the information gap.” [ 40 ] In the developed world, the majority of research institutions and universities provide their scientists with unlimited updated online access to most scientific journals. [ 41 ] However, in developing countries, where most conservation is needed, most research institutions cannot afford them and scientists suffer from a serious lack of access to advanced and up‐to‐date peer‐reviewed scholarly literature. [ 42 ] A World Health Organization (WHO) survey conducted in 2000 [ 43 ] reported that ≈65% of research institutions in developing countries have no subscription to any international scientific journals. Another relevant survey published in Nature [ 44 ] revealed that only eight nations in the world produce 85% of total publications globally. Unfortunately, this isolation is unconsciously promoted by developed‐country scientists who are usually encouraged and expected to publish research in “high profile” journals to increase competitiveness. This, in turn, facilitates access to further research funding, but this also further accentuates the information gap between developed and developing countries. If such asymmetry in research output and access to up‐to‐date information remains a characteristic of the scientific world, then conservation practitioners and scientists in developing countries will remain isolated and their work will continue to have an important lack of updated technical expertise, which will affect directly the conservation of their cultural heritage. In this light, further initiatives in conservation should aim, as much as possible, to promote open‐science and provide a better, wider, and more equal access to knowledge.

2.3. Increase the Synergetic Exchange of Knowledge between Science and Practice: Promoting Interdisciplinary