- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Reading Research Effectively

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Reading a Scholarly Article or Research Paper

Identifying a research problem to investigate usually requires a preliminary search for and critical review of the literature in order to gain an understanding about how scholars have examined a topic. Scholars rarely structure research studies in a way that can be followed like a story; they are complex and detail-intensive and often written in a descriptive and conclusive narrative form. However, in the social and behavioral sciences, journal articles and stand-alone research reports are generally organized in a consistent format that makes it easier to compare and contrast studies and to interpret their contents.

General Reading Strategies

W hen you first read an article or research paper, focus on asking specific questions about each section. This strategy can help with overall comprehension and with understanding how the content relates [or does not relate] to the problem you want to investigate. As you review more and more studies, the process of understanding and critically evaluating the research will become easier because the content of what you review will begin to coalescence around common themes and patterns of analysis. Below are recommendations on how to read each section of a research paper effectively. Note that the sections to read are out of order from how you will find them organized in a journal article or research paper.

1. Abstract

The abstract summarizes the background, methods, results, discussion, and conclusions of a scholarly article or research paper. Use the abstract to filter out sources that may have appeared useful when you began searching for information but, in reality, are not relevant. Questions to consider when reading the abstract are:

- Is this study related to my question or area of research?

- What is this study about and why is it being done ?

- What is the working hypothesis or underlying thesis?

- What is the primary finding of the study?

- Are there words or terminology that I can use to either narrow or broaden the parameters of my search for more information?

2. Introduction

If, after reading the abstract, you believe the paper may be useful, focus on examining the research problem and identifying the questions the author is trying to address. This information is usually located within the first few paragraphs of the introduction or in the concluding paragraph. Look for information about how and in what way this relates to what you are investigating. In addition to the research problem, the introduction should provide the main argument and theoretical framework of the study and, in the last paragraphs of the introduction, describe what the author(s) intend to accomplish. Questions to consider when reading the introduction include:

- What is this study trying to prove or disprove?

- What is the author(s) trying to test or demonstrate?

- What do we already know about this topic and what gaps does this study try to fill or contribute a new understanding to the research problem?

- Why should I care about what is being investigated?

- Will this study tell me anything new related to the research problem I am investigating?

3. Literature Review

The literature review describes and critically evaluates what is already known about a topic. Read the literature review to obtain a big picture perspective about how the topic has been studied and to begin the process of seeing where your potential study fits within the domain of prior research. Questions to consider when reading the literature review include:

- W hat other research has been conducted about this topic and what are the main themes that have emerged?

- What does prior research reveal about what is already known about the topic and what remains to be discovered?

- What have been the most important past findings about the research problem?

- How has prior research led the author(s) to conduct this particular study?

- Is there any prior research that is unique or groundbreaking?

- Are there any studies I could use as a model for designing and organizing my own study?

4. Discussion/Conclusion

The discussion and conclusion are usually the last two sections of text in a scholarly article or research report. They reveal how the author(s) interpreted the findings of their research and presented recommendations or courses of action based on those findings. Often in the conclusion, the author(s) highlight recommendations for further research that can be used to develop your own study. Questions to consider when reading the discussion and conclusion sections include:

- What is the overall meaning of the study and why is this important? [i.e., how have the author(s) addressed the " So What? " question].

- What do you find to be the most important ways that the findings have been interpreted?

- What are the weaknesses in their argument?

- Do you believe conclusions about the significance of the study and its findings are valid?

- What limitations of the study do the author(s) describe and how might this help formulate my own research?

- Does the conclusion contain any recommendations for future research?

5. Methods/Methodology

The methods section describes the materials, techniques, and procedures for gathering information used to examine the research problem. If what you have read so far closely supports your understanding of the topic, then move on to examining how the author(s) gathered information during the research process. Questions to consider when reading the methods section include:

- Did the study use qualitative [based on interviews, observations, content analysis], quantitative [based on statistical analysis], or a mixed-methods approach to examining the research problem?

- What was the type of information or data used?

- Could this method of analysis be repeated and can I adopt the same approach?

- Is enough information available to repeat the study or should new data be found to expand or improve understanding of the research problem?

6. Results

After reading the above sections, you should have a clear understanding of the general findings of the study. Therefore, read the results section to identify how key findings were discussed in relation to the research problem. If any non-textual elements [e.g., graphs, charts, tables, etc.] are confusing, focus on the explanations about them in the text. Questions to consider when reading the results section include:

- W hat did the author(s) find and how did they find it?

- Does the author(s) highlight any findings as most significant?

- Are the results presented in a factual and unbiased way?

- Does the analysis of results in the discussion section agree with how the results are presented?

- Is all the data present and did the author(s) adequately address gaps?

- What conclusions do you formulate from this data and does it match with the author's conclusions?

7. References

The references list the sources used by the author(s) to document what prior research and information was used when conducting the study. After reviewing the article or research paper, use the references to identify additional sources of information on the topic and to examine critically how these sources supported the overall research agenda. Questions to consider when reading the references include:

- Do the sources cited by the author(s) reflect a diversity of disciplinary viewpoints, i.e., are the sources all from a particular field of study or do the sources reflect multiple areas of study?

- Are there any unique or interesting sources that could be incorporated into my study?

- What other authors are respected in this field, i.e., who has multiple works cited or is cited most often by others?

- What other research should I review to clarify any remaining issues or that I need more information about?

NOTE : A final strategy in reviewing research is to copy and paste the title of the source [journal article, book, research report] into Google Scholar . If it appears, look for a "cited by" followed by a hyperlinked number [e.g., Cited by 45]. This number indicates how many times the study has been subsequently cited in other, more recently published works. This strategy, known as citation tracking, can be an effective means of expanding your review of pertinent literature based on a study you have found useful and how scholars have cited it. The same strategies described above can be applied to reading articles you find in the list of cited by references.

Reading Tip

Specific Reading Strategies

Effectively reading scholarly research is an acquired skill that involves attention to detail and an ability to comprehend complex ideas, data, and theoretical concepts in a way that applies logically to the research problem you are investigating. Here are some specific reading strategies to consider.

As You are Reading

- Focus on information that is most relevant to the research problem; skim over the other parts.

- As noted above, read content out of order! This isn't a novel; you want to start with the spoiler to quickly assess the relevance of the study.

- Think critically about what you read and seek to build your own arguments; not everything may be entirely valid, examined effectively, or thoroughly investigated.

- Look up the definitions of unfamiliar words, concepts, or terminology. A good scholarly source is Credo Reference .

Taking notes as you read will save time when you go back to examine your sources. Here are some suggestions:

- Mark or highlight important text as you read [e.g., you can use the highlight text feature in a PDF document]

- Take notes in the margins [e.g., Adobe Reader offers pop-up sticky notes].

- Highlight important quotations; consider using different colors to differentiate between quotes and other types of important text.

- Summarize key points about the study at the end of the paper. To save time, these can be in the form of a concise bulleted list of statements [e.g., intro has provides historical background; lit review has important sources; good conclusions].

Write down thoughts that come to mind that may help clarify your understanding of the research problem. Here are some examples of questions to ask yourself:

- Do I understand all of the terminology and key concepts?

- Do I understand the parts of this study most relevant to my topic?

- What specific problem does the research address and why is it important?

- Are there any issues or perspectives the author(s) did not consider?

- Do I have any reason to question the validity or reliability of this research?

- How do the findings relate to my research interests and to other works which I have read?

Adapted from text originally created by Holly Burt, Behavioral Sciences Librarian, USC Libraries, April 2018.

Another Reading Tip

When is it Important to Read the Entire Article or Research Paper

Laubepin argues, "Very few articles in a field are so important that every word needs to be read carefully." However, this implies that some studies are worth reading carefully. As painful and time-consuming as it may seem, there are valid reasons for reading a study in its entirety from beginning to end. Here are some examples:

- Studies Published Very Recently . The author(s) of a recent, well written study will provide a survey of the most important or impactful prior research in the literature review section. This can establish an understanding of how scholars in the past addressed the research problem. In addition, the most recently published sources will highlight what is currently known and what gaps in understanding currently exist about a topic, usually in the form of the need for further research in the conclusion .

- Surveys of the Research Problem . Some papers provide a comprehensive analytical overview of the research problem. Reading this type of study can help you understand underlying issues and discover why scholars have chosen to investigate the topic. This is particularly important if the study was published very recently because the author(s) should cite all or most of the key prior research on the topic. Note that, if it is a long-standing problem, there may be studies that specifically review the literature to identify gaps that remain. These studies often include the word review in their title [e.g., Hügel, Stephan, and Anna R. Davies. "Public Participation, Engagement, and Climate Change Adaptation: A Review of the Research Literature." Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 11 (July-August 2020): https://doi.org/10.1002/ wcc.645].

- Highly Cited . If you keep coming across the same citation to a study while you are reviewing the literature, this implies it was foundational in establishing an understanding of the research problem or the study had a significant impact within the literature [positive or negative]. Carefully reading a highly cited source can help you understand how the topic emerged and motivated scholars to further investigate the problem. It also could be a study you need to cite as foundational in your own paper to demonstrate to the reader that you understand the roots of the problem.

- Historical Overview . Knowing the historical background of a research problem may not be the focus of your analysis. Nevertheless, carefully reading a study that provides a thorough description and analysis of the history behind an event, issue, or phenomenon can add important context to understanding the topic and what aspect of the problem you may want to examine further.

- Innovative Methodological Design . Some studies are significant and worth reading in their entirety because the author(s) designed a unique or innovative approach to researching the problem. This may justify reading the entire study because it can motivate you to think creatively about pursuing an alternative or non-traditional approach to examining your topic of interest. These types of studies are generally easy to identify because they are often cited in others works because of their unique approach to studying the research problem.

- Cross-disciplinary Approach . R eviewing studies produced outside of your discipline is an essential component of investigating research problems in the social and behavioral sciences. Consider reading a study that was conducted by author(s) based in a different discipline [e.g., an anthropologist studying political cultures; a study of hiring practices in companies published in a sociology journal]. This approach can generate a new understanding or a unique perspective about the topic . If you are not sure how to search for studies published in a discipline outside of your major or of the course you are taking, contact a librarian for assistance.

Laubepin, Frederique. How to Read (and Understand) a Social Science Journal Article . Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ISPSR), 2013; Shon, Phillip Chong Ho. How to Read Journal Articles in the Social Sciences: A Very Practical Guide for Students . 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2015; Lockhart, Tara, and Mary Soliday. "The Critical Place of Reading in Writing Transfer (and Beyond): A Report of Student Experiences." Pedagogy 16 (2016): 23-37; Maguire, Moira, Ann Everitt Reynolds, and Brid Delahunt. "Reading to Be: The Role of Academic Reading in Emergent Academic and Professional Student Identities." Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 17 (2020): 5-12.

- << Previous: 1. Choosing a Research Problem

- Next: Narrowing a Topic Idea >>

- Last Updated: Mar 26, 2024 10:40 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, 113 great research paper topics.

General Education

One of the hardest parts of writing a research paper can be just finding a good topic to write about. Fortunately we've done the hard work for you and have compiled a list of 113 interesting research paper topics. They've been organized into ten categories and cover a wide range of subjects so you can easily find the best topic for you.

In addition to the list of good research topics, we've included advice on what makes a good research paper topic and how you can use your topic to start writing a great paper.

What Makes a Good Research Paper Topic?

Not all research paper topics are created equal, and you want to make sure you choose a great topic before you start writing. Below are the three most important factors to consider to make sure you choose the best research paper topics.

#1: It's Something You're Interested In

A paper is always easier to write if you're interested in the topic, and you'll be more motivated to do in-depth research and write a paper that really covers the entire subject. Even if a certain research paper topic is getting a lot of buzz right now or other people seem interested in writing about it, don't feel tempted to make it your topic unless you genuinely have some sort of interest in it as well.

#2: There's Enough Information to Write a Paper

Even if you come up with the absolute best research paper topic and you're so excited to write about it, you won't be able to produce a good paper if there isn't enough research about the topic. This can happen for very specific or specialized topics, as well as topics that are too new to have enough research done on them at the moment. Easy research paper topics will always be topics with enough information to write a full-length paper.

Trying to write a research paper on a topic that doesn't have much research on it is incredibly hard, so before you decide on a topic, do a bit of preliminary searching and make sure you'll have all the information you need to write your paper.

#3: It Fits Your Teacher's Guidelines

Don't get so carried away looking at lists of research paper topics that you forget any requirements or restrictions your teacher may have put on research topic ideas. If you're writing a research paper on a health-related topic, deciding to write about the impact of rap on the music scene probably won't be allowed, but there may be some sort of leeway. For example, if you're really interested in current events but your teacher wants you to write a research paper on a history topic, you may be able to choose a topic that fits both categories, like exploring the relationship between the US and North Korea. No matter what, always get your research paper topic approved by your teacher first before you begin writing.

113 Good Research Paper Topics

Below are 113 good research topics to help you get you started on your paper. We've organized them into ten categories to make it easier to find the type of research paper topics you're looking for.

Arts/Culture

- Discuss the main differences in art from the Italian Renaissance and the Northern Renaissance .

- Analyze the impact a famous artist had on the world.

- How is sexism portrayed in different types of media (music, film, video games, etc.)? Has the amount/type of sexism changed over the years?

- How has the music of slaves brought over from Africa shaped modern American music?

- How has rap music evolved in the past decade?

- How has the portrayal of minorities in the media changed?

Current Events

- What have been the impacts of China's one child policy?

- How have the goals of feminists changed over the decades?

- How has the Trump presidency changed international relations?

- Analyze the history of the relationship between the United States and North Korea.

- What factors contributed to the current decline in the rate of unemployment?

- What have been the impacts of states which have increased their minimum wage?

- How do US immigration laws compare to immigration laws of other countries?

- How have the US's immigration laws changed in the past few years/decades?

- How has the Black Lives Matter movement affected discussions and view about racism in the US?

- What impact has the Affordable Care Act had on healthcare in the US?

- What factors contributed to the UK deciding to leave the EU (Brexit)?

- What factors contributed to China becoming an economic power?

- Discuss the history of Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies (some of which tokenize the S&P 500 Index on the blockchain) .

- Do students in schools that eliminate grades do better in college and their careers?

- Do students from wealthier backgrounds score higher on standardized tests?

- Do students who receive free meals at school get higher grades compared to when they weren't receiving a free meal?

- Do students who attend charter schools score higher on standardized tests than students in public schools?

- Do students learn better in same-sex classrooms?

- How does giving each student access to an iPad or laptop affect their studies?

- What are the benefits and drawbacks of the Montessori Method ?

- Do children who attend preschool do better in school later on?

- What was the impact of the No Child Left Behind act?

- How does the US education system compare to education systems in other countries?

- What impact does mandatory physical education classes have on students' health?

- Which methods are most effective at reducing bullying in schools?

- Do homeschoolers who attend college do as well as students who attended traditional schools?

- Does offering tenure increase or decrease quality of teaching?

- How does college debt affect future life choices of students?

- Should graduate students be able to form unions?

- What are different ways to lower gun-related deaths in the US?

- How and why have divorce rates changed over time?

- Is affirmative action still necessary in education and/or the workplace?

- Should physician-assisted suicide be legal?

- How has stem cell research impacted the medical field?

- How can human trafficking be reduced in the United States/world?

- Should people be able to donate organs in exchange for money?

- Which types of juvenile punishment have proven most effective at preventing future crimes?

- Has the increase in US airport security made passengers safer?

- Analyze the immigration policies of certain countries and how they are similar and different from one another.

- Several states have legalized recreational marijuana. What positive and negative impacts have they experienced as a result?

- Do tariffs increase the number of domestic jobs?

- Which prison reforms have proven most effective?

- Should governments be able to censor certain information on the internet?

- Which methods/programs have been most effective at reducing teen pregnancy?

- What are the benefits and drawbacks of the Keto diet?

- How effective are different exercise regimes for losing weight and maintaining weight loss?

- How do the healthcare plans of various countries differ from each other?

- What are the most effective ways to treat depression ?

- What are the pros and cons of genetically modified foods?

- Which methods are most effective for improving memory?

- What can be done to lower healthcare costs in the US?

- What factors contributed to the current opioid crisis?

- Analyze the history and impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic .

- Are low-carbohydrate or low-fat diets more effective for weight loss?

- How much exercise should the average adult be getting each week?

- Which methods are most effective to get parents to vaccinate their children?

- What are the pros and cons of clean needle programs?

- How does stress affect the body?

- Discuss the history of the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians.

- What were the causes and effects of the Salem Witch Trials?

- Who was responsible for the Iran-Contra situation?

- How has New Orleans and the government's response to natural disasters changed since Hurricane Katrina?

- What events led to the fall of the Roman Empire?

- What were the impacts of British rule in India ?

- Was the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki necessary?

- What were the successes and failures of the women's suffrage movement in the United States?

- What were the causes of the Civil War?

- How did Abraham Lincoln's assassination impact the country and reconstruction after the Civil War?

- Which factors contributed to the colonies winning the American Revolution?

- What caused Hitler's rise to power?

- Discuss how a specific invention impacted history.

- What led to Cleopatra's fall as ruler of Egypt?

- How has Japan changed and evolved over the centuries?

- What were the causes of the Rwandan genocide ?

- Why did Martin Luther decide to split with the Catholic Church?

- Analyze the history and impact of a well-known cult (Jonestown, Manson family, etc.)

- How did the sexual abuse scandal impact how people view the Catholic Church?

- How has the Catholic church's power changed over the past decades/centuries?

- What are the causes behind the rise in atheism/ agnosticism in the United States?

- What were the influences in Siddhartha's life resulted in him becoming the Buddha?

- How has media portrayal of Islam/Muslims changed since September 11th?

Science/Environment

- How has the earth's climate changed in the past few decades?

- How has the use and elimination of DDT affected bird populations in the US?

- Analyze how the number and severity of natural disasters have increased in the past few decades.

- Analyze deforestation rates in a certain area or globally over a period of time.

- How have past oil spills changed regulations and cleanup methods?

- How has the Flint water crisis changed water regulation safety?

- What are the pros and cons of fracking?

- What impact has the Paris Climate Agreement had so far?

- What have NASA's biggest successes and failures been?

- How can we improve access to clean water around the world?

- Does ecotourism actually have a positive impact on the environment?

- Should the US rely on nuclear energy more?

- What can be done to save amphibian species currently at risk of extinction?

- What impact has climate change had on coral reefs?

- How are black holes created?

- Are teens who spend more time on social media more likely to suffer anxiety and/or depression?

- How will the loss of net neutrality affect internet users?

- Analyze the history and progress of self-driving vehicles.

- How has the use of drones changed surveillance and warfare methods?

- Has social media made people more or less connected?

- What progress has currently been made with artificial intelligence ?

- Do smartphones increase or decrease workplace productivity?

- What are the most effective ways to use technology in the classroom?

- How is Google search affecting our intelligence?

- When is the best age for a child to begin owning a smartphone?

- Has frequent texting reduced teen literacy rates?

How to Write a Great Research Paper

Even great research paper topics won't give you a great research paper if you don't hone your topic before and during the writing process. Follow these three tips to turn good research paper topics into great papers.

#1: Figure Out Your Thesis Early

Before you start writing a single word of your paper, you first need to know what your thesis will be. Your thesis is a statement that explains what you intend to prove/show in your paper. Every sentence in your research paper will relate back to your thesis, so you don't want to start writing without it!

As some examples, if you're writing a research paper on if students learn better in same-sex classrooms, your thesis might be "Research has shown that elementary-age students in same-sex classrooms score higher on standardized tests and report feeling more comfortable in the classroom."

If you're writing a paper on the causes of the Civil War, your thesis might be "While the dispute between the North and South over slavery is the most well-known cause of the Civil War, other key causes include differences in the economies of the North and South, states' rights, and territorial expansion."

#2: Back Every Statement Up With Research

Remember, this is a research paper you're writing, so you'll need to use lots of research to make your points. Every statement you give must be backed up with research, properly cited the way your teacher requested. You're allowed to include opinions of your own, but they must also be supported by the research you give.

#3: Do Your Research Before You Begin Writing

You don't want to start writing your research paper and then learn that there isn't enough research to back up the points you're making, or, even worse, that the research contradicts the points you're trying to make!

Get most of your research on your good research topics done before you begin writing. Then use the research you've collected to create a rough outline of what your paper will cover and the key points you're going to make. This will help keep your paper clear and organized, and it'll ensure you have enough research to produce a strong paper.

What's Next?

Are you also learning about dynamic equilibrium in your science class? We break this sometimes tricky concept down so it's easy to understand in our complete guide to dynamic equilibrium .

Thinking about becoming a nurse practitioner? Nurse practitioners have one of the fastest growing careers in the country, and we have all the information you need to know about what to expect from nurse practitioner school .

Want to know the fastest and easiest ways to convert between Fahrenheit and Celsius? We've got you covered! Check out our guide to the best ways to convert Celsius to Fahrenheit (or vice versa).

These recommendations are based solely on our knowledge and experience. If you purchase an item through one of our links, PrepScholar may receive a commission.

Christine graduated from Michigan State University with degrees in Environmental Biology and Geography and received her Master's from Duke University. In high school she scored in the 99th percentile on the SAT and was named a National Merit Finalist. She has taught English and biology in several countries.

Student and Parent Forum

Our new student and parent forum, at ExpertHub.PrepScholar.com , allow you to interact with your peers and the PrepScholar staff. See how other students and parents are navigating high school, college, and the college admissions process. Ask questions; get answers.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

- Chess (Gr. 1-4)

- TV (Gr. 1-4)

- Metal Detectors (Gr. 2-6)

- Tetris (Gr. 2-6)

- Seat Belts (Gr. 2-6)

- The Coliseum (Gr. 2-6)

- The Pony Express (Gr. 2-6)

- Wintertime (Gr. 2-6)

- Reading (Gr. 3-7)

- Black Friday (Gr. 3-7)

- Hummingbirds (Gr. 3-7)

- Worst Game Ever? (Gr. 4-8)

- Carnivorous Plants (Gr. 4-8)

- Google (Gr. 4-8)

- Honey Badgers (Gr. 4-8)

- Hyperinflation (Gr. 4-8)

- Koko (Gr. 4-8)

- Mongooses (Gr. 5-9)

- Trampolines (Gr. 5-9)

- Garbage (Gr. 5-9)

- Maginot Line (Gr. 5-9)

- Asian Carp (Gr. 5-9)

- Tale of Two Countries (Gr. 6-10)

- Kevlar (Gr. 7-10)

- Tigers (Gr. 7-11)

- Statue of Liberty (Gr. 8-10)

- Submarines (Gr. 8-12)

- Castles (Gr. 9-13)

- Gutenberg (Gr. 9-13)

- Author's Purpose Practice 1

- Author's Purpose Practice 2

- Author's Purpose Practice 3

- Fact and Opinion Practice 1

- Fact and Opinion Practice 2

- Fact and Opinion Practice 3

- Idioms Practice Test 1

- Idioms Practice Test 2

- Figurative Language Practice 1

- Figurative Language Practice 2

- Figurative Language Practice 3

- Figurative Language Practice 4

- Figurative Language Practice 5

- Figurative Language Practice 6

- Figurative Language Practice 7

- Figurative Language Practice 8

- Figurative Language Practice 9

- Figurative Language of Edgar Allan Poe

- Figurative Language of O. Henry

- Figurative Language of Shakespeare

- Genre Practice 1

- Genre Practice 2

- Genre Practice 3

- Genre Practice 4

- Genre Practice 5

- Genre Practice 6

- Genre Practice 7

- Genre Practice 8

- Genre Practice 9

- Genre Practice 10

- Irony Practice 1

- Irony Practice 2

- Irony Practice 3

- Making Inferences Practice 1

- Making Inferences Practice 2

- Making Inferences Practice 3

- Making Inferences Practice 4

- Making Inferences Practice 5

- Main Idea Practice 1

- Main Idea Practice 2

- Point of View Practice 1

- Point of View Practice 2

- Text Structure Practice 1

- Text Structure Practice 2

- Text Structure Practice 3

- Text Structure Practice 4

- Text Structure Practice 5

- Story Structure Practice 1

- Story Structure Practice 2

- Story Structure Practice 3

- Author's Purpose

- Characterizations

- Context Clues

- Fact and Opinion

- Figurative Language

- Grammar and Language Arts

- Poetic Devices

- Point of View

- Predictions

- Reading Comprehension

- Story Structure

- Summarizing

- Text Structure

- Character Traits

- Common Core Aligned Unit Plans

- Teacher Point of View

- Teaching Theme

- Patterns of Organization

- Project Ideas

- Reading Activities

- How to Write Narrative Essays

- How to Write Persuasive Essays

- Narrative Essay Assignments

- Narrative Essay Topics

- Persuasive Essay Topics

- Research Paper Topics

- Rubrics for Writing Assignments

- Learn About Sentence Structure

- Grammar Worksheets

- Noun Worksheets

- Parts of Speech Worksheets

- Punctuation Worksheets

- Sentence Structure Worksheets

- Verbs and Gerunds

- Examples of Allitertion

- Examples of Hyperbole

- Examples of Onomatopoeia

- Examples of Metaphor

- Examples of Personification

- Examples of Simile

- Figurative Language Activities

- Figurative Language Examples

- Figurative Language Poems

- Figurative Language Worksheets

- Learn About Figurative Language

- Learn About Poetic Devices

- Idiom Worksheets

- Online Figurative Language Tests

- Onomatopoeia Worksheets

- Personification Worksheets

- Poetic Devices Activities

- Poetic Devices Worksheets

- About This Site

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Understanding CCSS Standards

- What's New?

Ereading Worksheets

Free reading worksheets, activities, and lesson plans., site navigation.

- Learn About Author’s Purpose

- Author’s Purpose Quizzes

- Character Types Worksheets and Lessons

- List of Character Traits

- Differentiated Reading Instruction Worksheets and Activities

- Fact and Opinion Worksheets

- Irony Worksheets

- Animal Farm Worksheets

- Literary Conflicts Lesson and Review

- New Home Page Test

- Lord of the Flies Chapter 2 Worksheet

- Lord of the Flies Chapter 5 Worksheet

- Lord of the Flies Chapter 6 Worksheet

- Lord of the Flies Chapter 10 Worksheet

- Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

- Sister Carrie

- The Count of Monte Cristo

- The Odyssey

- The War of the Worlds

- The Wizard of Oz

- Mood Worksheets

- Context Clues Worksheets

- Inferences Worksheets

- Main Idea Worksheets

- Making Predictions Worksheets

- Nonfiction Passages and Functional Texts

- Setting Worksheets

- Summarizing Worksheets and Activities

- Short Stories with Questions

- Story Structure Activities

- Story Structure Worksheets

- Tone Worksheets

- Types of Conflict Worksheets

- Reading Games

- Figurative Language Poems with Questions

- Hyperbole and Understatement Worksheets

- Simile and Metaphor Worksheets

- Simile Worksheets

- Hyperbole Examples

- Metaphor Examples

- Personification Examples

- Simile Examples

- Understatement Examples

- Idiom Worksheets and Tests

- Poetic Devices Worksheets & Activities

- Alliteration Examples

- Allusion Examples

- Onomatopoeia Examples

- Onomatopoeia Worksheets and Activities

- Genre Worksheets

- Genre Activities

- Capitalization Worksheets, Lessons, and Tests

- Contractions Worksheets and Activities

- Double Negative Worksheets

- Homophones & Word Choice Worksheets

- ‘Was’ or ‘Were’

- Simple Subjects & Predicates Worksheets

- Subjects, Predicates, and Objects

- Clauses and Phrases

- Type of Sentences Worksheets

- Sentence Structure Activities

- Comma Worksheets and Activities

- Semicolon Worksheets

- End Mark Worksheets

- Noun Worksheets, Lessons, and Tests

- Verb Worksheets and Activities

- Pronoun Worksheets, Lessons, and Tests

- Adverbs & Adjectives Worksheets, Lessons, & Tests

- Preposition Worksheets and Activities

- Conjunctions Worksheets and Activities

- Interjections Worksheets

- Parts of Speech Activities

- Verb Tense Activities

- Past Tense Worksheets

- Present Tense Worksheets

- Future Tense Worksheets

- Point of View Activities

- Point of View Worksheets

- Teaching Point of View

- Cause and Effect Example Paragraphs

- Chronological Order

- Compare and Contrast

- Order of Importance

- Problem and Solution

- Text Structure Worksheets

- Text Structure Activities

- Essay Writing Rubrics

- Narrative Essay Topics and Story Ideas

- Narrative Essay Worksheets & Writing Assignments

- Persuasive Essay and Speech Topics

- Persuasive Essay Worksheets & Activities

- Writing Narrative Essays and Short Stories

- Writing Persuasive Essays

- All Reading Worksheets

- Understanding Common Core State Standards

- Remote Learning Resources for Covid-19 School Closures

- What’s New?

- Ereading Worksheets | Legacy Versions

- Online Figurative Language Practice

- Online Genre Practice Tests

- Online Point of View Practice Tests

- 62 School Project Ideas

- 2nd Grade Reading Worksheets

- 3rd Grade Reading Worksheets

- 4th Grade Reading Worksheets

- 5th Grade Reading Worksheets

- 6th Grade Reading Worksheets

- 7th Grade Reading Worksheets

- 8th Grade Reading Worksheets

- 9th Grade Reading Worksheets

- 10th Grade Reading Worksheets

- Membership Billing

- Membership Cancel

- Membership Checkout

- Membership Confirmation

- Membership Invoice

- Membership Levels

- Your Profile

Want Updates?

101 research paper topics.

- Why do we sleep ?

- How do GPS systems work?

- Who was the first person to reach the North Pole ?

- Did anybody ever escape Alcatraz ?

- What was life like for a gladiator ?

- What are the effects of prolonged steroid use on the human body?

- What happened during the Salem witch trials ?

- Are there any effective means of repelling insects ?

- How did trains and railroads change life in America?

- What may have occurred during the Roswell UFO incident of 1947?

- How is bulletproof clothing made?

- What Olympic events were practiced in ancient Greece?

- What are the major theories explaining the disappearance of the dinosaurs ?

- How was the skateboard invented and how has it changed over the years?

- How did the long bow contribute to English military dominance?

- What caused the stock market crash of 2008?

- How did Cleopatra come to power in Egypt what did she do during her reign?

- How has airport security intensified since September 11 th , 2001?

- What is life like inside of a beehive ?

- Where did hip hop originate and who were its founders?

- What makes the platypus a unique and interesting mammal?

- How does tobacco use affect the human body?

- How do computer viruses spread and in what ways do they affect computers?

- What is daily life like for a Buddhist monk ?

- What are the origins of the conflict in Darfur ?

- How did gunpowder change warfare?

- In what ways do Wal-Mart stores affect local economies?

- How were cats and dogs domesticated and for what purposes?

- What do historians know about ninjas ?

- How has the music industry been affected by the internet and digital downloading?

- What were the circumstances surrounding the death of Osama Bin Laden ?

- What was the women’s suffrage movement and how did it change America?

- What efforts are being taken to protect endangered wildlife ?

- How much does the war on drugs cost Americans each year?

- How is text messaging affecting teen literacy?

- Are humans still evolving ?

- What technologies are available to home owners to help them conserve energy ?

- How have oil spills affected the planet and what steps are being taken to prevent them?

- What was the Magna Carta and how did it change England?

- What is the curse of the pharaohs?

- Why was Socrates executed?

- What nonlethal weapons are used by police to subdue rioters?

- How does the prison population in America compare to other nations?

- How did ancient sailors navigate the globe?

- Can gamblers ever acquire a statistical advantage over the house in casino games?

- What is alchemy and how has it been attempted?

- How are black holes formed?

- How was the assassination of Abraham Lincoln plotted and executed?

- Do the benefits of vaccination outweigh the risks?

- How do submarines work?

- Do lie detector tests accurately determine truthful statements?

- How did Cold War tension affect the US and the world?

- What happened to the lost settlers at Roanoke ?

- How does a hybrid car save energy?

- What ingredients can be found inside of a hotdog ?

- How did Julius Caesar affect Rome?

- What are some common sleep disorders and how are they treated?

- How did the Freedom Riders change society?

- How is internet censorship used in China and around the world?

- What was the code of the Bushido and how did it affect samurai warriors ?

- What are the risks of artificial tanning or prolonged exposure to the sun?

- What programs are available to help war veterans get back into society?

- What steps are involved in creating a movie or television show?

- How have the film and music industries dealt with piracy ?

- How did Joan of Arc change history?

- What responsibilities do secret service agents have?

- How does a shark hunt?

- What dangers and hardships did Lewis and Clark face when exploring the Midwest?

- Has the Patriot Act prevented or stopped terrorist acts in America?

- Do states that allow citizens to carry guns have higher or lower crime rates?

- How are the Great Depression and the Great Recession similar and different?

- What are the dangers of scuba diving and underwater exploration?

- How does the human brain store and retrieve memories ?

- What was the Manhattan Project and what impact did it have on the world?

- How does stealth technology shield aircraft from radar?

- What causes tornadoes ?

- Why did Martin Luther protest against the Catholic Church?

- How does a search engine work?

- What are the current capabilities and future goals of genetic engineers ?

- How did the Roman Empire fall?

- What obstacles faced scientists in breaking the sound barrier ?

- How did the black plague affect Europe?

- What happened to Amelia Earhart ?

- What are the dangers and hazards of using nuclear power ?

- How did Genghis Khan conquer Persia?

- What architectural marvels were found in Tenochtitlan, capital of the Aztec Empire ?

- From where does spam email come and can we stop it?

- How does night vision work?

- How did journalists influence US war efforts in Vietnam ?

- What are the benefits and hazards of medical marijuana ?

- What causes desert mirages and how do they affect wanderers?

- What was the cultural significance of the first moon landing ?

- What are sinkholes and how are they formed?

- Have any psychics ever solved crimes or prevented them from occurring?

- Who is Vlad the Impaler and what is his connection to Count Dracula ?

- What are the risks of climate change and global warming ?

- What treatments are available to people infected with HIV and are they effective?

- Who was a greater inventor, Leonardo di Vinci or Thomas Edison ?

- How are the Chinese and American economies similar and different?

- Why was communism unsuccessful in so many countries?

- In what ways do video games affect children and teenagers?

923 Comments

I like using this website when I assist kids with learning as a lot of these topics are quickly covered in the school systems. Thankyou

Mackenah Nicole Molina

Wow! I always have trouble deiciding what to do a research project on but this list has totally solved that. Now my only problem is choosing what idea on this list I should do first!

Most of these my teacher rejected because apparently ‘these aren’t grade level topics, and I doubt they interest you”

I’m sorry to hear that. Sounds like you will have a potentially valuable character-building experience in the short-term.

Edwin Augusto Galindo Cuba

THIS SITE IS AWESOME, THERE ARE LOTS OF TOPICS TO LEARN AND MASTER OUR SKILLS!

research kid

I need one about animals, please. I have been challenged to a animal research project, Due Friday. I have no clue what to research! somebody help, thanks for reading!

You can do one on bats

For international studies you can do Defense and Security.

This was very helpful.

Research on Ben Franklin? I think THAT will get a real charge out of everyone (hehehehegetit)

Mandy Maher

“Is it possible to colonize Mars?”

maddy burney

these are silly topics

thx for making this real.

more gaming questions!!!!!!

Is it still considered stealing if you don’t get caught?

Yes, yes it is still considered stealing.

I need topics on memes

Mary Nnamani

Please I need project topics on Language Literature

Marcella Vallarino

I would appreciate a list of survey questions for middle school grades 6-8

I need a research topics about public sector management

I NEED FIVE EXAMPLES EACH ON QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH (EDUCATION, HEALTH, TECHNOLOGY, ECONOMY AND ENGINEERING)

publish research that are interesting please……

hey can you do one on the burmiueda triangle

Anybody know video games effect kids,and,teens. There Fun!!

they’re

I need a topic about woman history if any of u can find 1 please that would be great!

You could research about the history of the astronauts, and of human past (WWI, WWII, etc.)

so about women? Manitoba Women Win the Right to Vote in Municipal Elections, The First Women, January 23, 1849: Elizabeth Blackwell becomes the first woman to graduate from medical school and become a doctor in the United States, Rosa Parks Civil Rights Equal Pay. I have way more. so if you need more just ask.

communism is good

what are you a communist?!?!

Did FDR know about the upcoming attack on Pearl Harbor on 07 DEC 1941.

do you know how babies are born

Christine Singu

kindly assist with a research topic in the field of accounting or auditing

need more about US army

Please can yiu give me a topic in education

I think one should be how can music/Video games can affect the life for people

or How Do Video Games Affect Teenagers?

zimbabwe leader

I think a good topic is supporting the confederate flag!

Need a research topic within the context of students union government and dues payments

do more weird ones plz

joyce alcantara

Hi pls po can you give me a topic relate for humanities pls thank u.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Subscribe Now

Popular content.

- Author's Purpose Worksheets

- Characterization Worksheets

- Common Core Lesson and Unit Plans

- Online Reading Practice Tests

- Plot Worksheets

- Reading Comprehension Worksheets

- Summary Worksheets

- Theme Worksheets

New and Updated Pages

- Capitalization Worksheets

- Contractions Worksheets

- Double Negatives Worksheets

- Homophones & Word Choice Worksheets

BECOME A MEMBER!

Project Ideas for Reading

Many of these ideas are excerpted from "Share with a Flare" by Anne Semple Bruce, Blue Ribbon Press.

Most projects will be related in some way to comprehension, understanding genres and developing dispositions to enjoy reading, read for daily living and/or read for information.

Visual arts and crafts

Performing arts and drama, written language, other activities.

Audiotape a book or play for the visually impaired. Students first read the book, discuss its message, characters, and whether there are changes of mood that should be reflected as it is read. Pronunciations and meanings for unfamiliar words are clarified. Different students read dialogue for particular characters as such dialogue appears. The audiotape is presented to an appropriate institution or program in the community. (Comprehension, vocabulary and fluency are all addressed.)

How do I know it? Let me show the ways! Books/stories/information from articles are retold in other creative formats (plays, newspapers, comic books, puppet shows, song and dance, illustrated guides, etc.) and shared with an appropriate audience. Reading the targeted text and group discussion precedes the selection of the project(s) by different teams.

Romeo, Juliet, who would you be today? Reset a Shakespearean play into modern day and retell the story. Play reading and discussion for comprehension precedes the transformation.

Books as Calls to Action. Stories and songs arouse emotions. Emotions often spur a desire to do something. Discuss the fact that there are universal themes that authors use to create the conflicts or problems at the center of great literature. After eliciting several of these themes (greed, injustice, poverty, discrimination, war, love, selfishness, overcoming obstacles, fear, etc.) present students with a choice of books to read (e.g., To Kill a Mockingbird, Romeo and Juliet, Grapes of Wrath, The Diary of Anne Frank, etc.). Their discussions should tie the theme to modern problems. Students can plan a debate on how society should deal with the problem, an informative exhibit or event, or a service project to help alleviate the basic problem. An alternate approach is to have them select a theme and assign a book dealing with that theme.

Is Shakespeare Still Relevant? Students read at least one of Shakespeare’s plays and identify the universal theme, which will still be relevant today. They then select a way to convince an audience of their opinions. Lends itself to debate, resetting in modern times, finding articles in newspapers (current and archived) and highlighting (and giving meaning to) quotes to think about today.

Extend the Reading. Students or groups of students can extend the reading of a common text from different perspectives and using different talents to reveal their understanding by engaging in any of these activities.

Create a(n):

Advertisement to buy or read a book—Be prepared to explain what in the advertisement will attract people. Think about what in the book might attract people with different interests and backgrounds.

Award for the book— Awards are often certificates or plaques. What about the book deserves an award? What kind of award does it deserve?

Book jacket— The jacket should give a brief summary—but not give away the ending! It should also say something about the author.

Bulletin board or posters— List the funniest jokes or riddles from books, or amazing facts; the display is interactive and can grow over time as children add to it.

Chalk talk— Using chalk on a chalkboard or markers on a white board, briefly retell the story in pictures while simultaneously relating it orally.

Collage— Show the important ideas, events or characters—Be sure you can tell why each part of the collage is there. What was its importance? All of the pieces together could present a message. What would it be for this book?

Cartoon or graphic novel of the story or part of it—Does the cartoon version illustrate the important events and feelings?

Costume for a character—Why is this an appropriate costume? Be able to tell us about the character in terms of who he/she is and about the setting of the story that would bring images of this costume.

Diorama— It should portray several important scenes that allow you to retell highlights of the story as seen in the diorama.

Family tree of a character—Some stories will not lend themselves to this very well. Choose only if a family tree is important to the story.

Illustration of a setting, favorite part or amazing or important facts—Be able to explain all you can about what you have illustrated. Was it the most important setting? The first? The last? What about the fact is amazing or important?

Map of the setting or a character’s journey—As you point out different sites on the map, can you relate what happened there?

Mask of a character— Help others know the character. Who was he or she? What part did the character play in the story? Do you know someone like this character?

Mobile of story elements (story grammar)— Mobiles can be made from separate pieces of paper, on a cube, a balloon, or beach ball that can be hung with each element visible. Important parts of the story should be highlighted. These may include characters, setting, problem, solution, plot and theme. Very young children may use a simpler format of story beginning, middle and end.

Mural— Be sure you can tell what the mural shows and why you picked these things to be part of it.

Painting— Paint a scene; a part you liked, the turning point in the story, characters or illustrate an amazing or new fact you learned. Share why you chose what you did and what part it (they) played in the story as a whole.

Poster illustrating milestone events—Be able to explain their importance.

Puppet of a character— Create a puppet and be prepared to tell everyone about this character and its place in the book. Since it is a puppet, tell it from the perspective of the character through the mouth of the puppet.

Scrapbook based on information or events in the book—For this you will have to imagine the sequence of events and imagine artifacts or articles that might have been written as the events of the story unfolded.

Three-dimensional characters made of stuffed socks or other material—Tell about the characters and their place in the story or have them talk about themselves and their acquaintances.

PowerPoint presentation based on information from the book or retelling the story—This venue may be more appropriate for nonfiction books.

Research— Books and stories can be used to prompt research on the times, places and customs from the stories, to compare characters to historical figures or to find items in today’s news that relate to the story. Such research should at the very least be presented to the rest of the class, perhaps inviting parents or community members or displayed as an exhibit in the hall.

Design and perform:

Accompaniment to a retelling or reading of the story—Consider sound effects or music.

Choral reading of poetry.

Graphics or use ready-made graphics— Use them to highlight parts of the story or to retell it.

Interview with a character or with the author—This requires a partner, one to be the interviewer and one the interviewee. Try to think of what people listening to the interview would like to know.

Memorize and recite a passage from the book—Be able to tell what happened before and after this passage and what its significance is to the storyline. Several students could memorize favorite passages and present them at appropriate times as a narrator tells the whole story.

Original song or rap about the story—Be sure to pick up an important idea and know how it fits with the whole story if it does not tell the whole story.

Oral critique of the story or topics related to the story that have been researched—what made it interesting or not interesting; were the characters believable or were they meant to take you out of the world into fantasy and did they do that; what do you think of the theme of the story; would you want to read other books like this or by this author? This could be done as a panel show.

Oral directions of how to make or do something from the book—If possible, pick something that the audience will actually be able to make while you speak.

Pantomime the story, a scene, or a character for others who have read the book—Have the audience ask yes or no questions if they need clues.

Parade of characters from one book or a variety of books—Each character can tell about what he or she does in the story and how it all turns out from the character’s perspective. They could tell something that happened to them and ask the audience to identify the book or story.

Play— Create a short play that summarizes the story and act it out using props and costumes (could be a spare tie, hat or ribbon).

Radio commercial— This is similar to a written advertisement but must be done with only sound. How can you make readers want to buy or borrow this book in up to 60 seconds time?

Reader’s theatre— Students develop scripts, perform in groups and practice using their voice to depict characters from texts.

Story retelling orally to a group—Can you use your own words as a storyteller to get them interested? Can you create suspense, excitement or calm? Can you make them think the story is happening right there?

Talk show featuring the book or the author or a character from the book—Someone will be the host and others will play the author and readers and respond to questions.

Television commercial —Sell the book or a play about the book. Visuals are needed and could be produced as PowerPoint or a story board.

Travel lecture about a particular setting or location in the book, using visual aids.

Videotaped retelling or re-enactment of a scene—Live performance is preferable.

Write a(n):

Alphabet book or large poster with boxes for each letter of the alphabet with something corresponding to the story for each letter.

Autobiography of a character.

Book review or critique of the book—similar to oral project but written so it can be part of an exhibition.

Biography of the author or illustrator.

Copy passages or phrases from the book that are particularly memorable or well written—Keep such passages in a special journal or share on a poster with why you think they are special.

Crossword puzzle or acrostic— Create by using vocabulary or important characters, events or facts from the book.

Diary or journal of a character—Pretend that you are the character in the book. As each part of the story progresses, write an entry from the viewpoint of the character.

Game questions— Create questions based on the story that could be used in a game like Jeopardy or Twenty Questions.

Investigation— Does something in the reading make you curious about your own community or the people you know? Conduct a poll or gather data to find out. Display the data and interpret it for an audience.

Letter to one of the characters— This letter should focus on something that happens in the story to that character, expressing sympathy, outrage, desire to help, request, or questioning something that has been said or done. Your letter should show that you understand the story.

Letter to the author— What would you say to the author about the story? Did you enjoy it? Were you confused by something? Did it make you think or feel strongly? Did it make you think about something in your life?

Letters between characters— Imagine one character writing to another in the story. Think about their relationship. What might they each say to the other? Be prepared to explain why they would write what they do.

Math story problem drawn from the story— In many stories there are references to numbers or shapes or chance. If there are some in your book, can word problems be written about them? (Be sure to provide the solutions.)

Newspaper or newspaper article— Select an event and act as a local reporter. Write an article for the newspaper that captures what was happening. For historic reading, a whole newspaper page or two may be in order reporting on various aspects of the day.

New title for the book— Do you think the book could have a different title? Propose a new title and tell why you think it would be more appropriate than the one it has.

Opinion and proof— Write an opinion about a character or about a piece of information in a non-fiction book and then cite evidence from the book to support your opinion.

Organize a community project— If your reading has brought to mind a need in the community that young people can help with, organize a group for community service and carry it out (e.g., food or clothing collection, visiting the elderly, stories or songs on DVD, cleaning up the neighborhood, etc.).

Persuasive article or speech about the book or a subject explored in the book—Try to convince others to agree with your position on the topic explored or to take action about something the book has addressed.

Poem about a character or event in the book—Look at various forms of poetry such as acrostics, haiku, odes, etc.

Propose legislation— If the reading revealed a need in the community, propose a piece of legislation to correct what is wrong. Support your proposal with logical arguments.

Reference book— Create it from information learned in the book and related books.

Riddles about characters or events—Share them with an audience.

Sequel or prequel to the story—What happened before the book began? After it ended?

Story rewrite— Can you put a new ending on the story? At what point in the current book will the new ending begin to unfold? Why do you like this ending?

Create or use a(n):

Book talk— Discuss several books that will entice other students to read them.

Book discussion, book club or literature circle to talk about the book with others—Books on some topics may lead to debates or campaigns.

Book fair— Have students showcase titles, authors and genres they’ve read.

Build or create something from the story—Pick something that is interesting to students. For example, a book about dogs might lend itself to building a doghouse; a book about frontier days might produce a rag or straw doll; a book about a million might lead to collecting or creating a million of something.

Edible book fair— Students can prepare or bring in a dish that relates to the book. For example, food arrangement or cake baked in the shape of the main character (works well if it’s an animal), or a character’s favorite dish, or food appropriate to a setting, or a type of food that’s discussed in the book such as corn in a book about Midwest farming or Tang orange drink in a book about space exploration, or even food that’s a pun on the title such as a cheese dip called “Velveeta Rabbit” based on the book “The Velveteen Rabbit”.

Graphic organizer to categorize and relate ideas—When using any of these be prepared to explain to the audience what is written to help them understand the story, important aspects and relationships, or the author’s devices.

- Character map

- Semantic feature analysis

- Timeline or calendar

Artifacts— Have them relate to the subject such as confederate currency in a book about the Civil War or shells in a book about the seashore.

Research the topic of the book, the time period or the author—Present the information to others in an interesting way.

Read similar books—Select books by the same author, in the same series, on the same topic, or on the same topic but in a different genre such as nonfiction or poetry and compare to the original book.

How to Read a Research Paper – A Guide to Setting Research Goals, Finding Papers to Read, and More

If you work in a scientific field, you should try to build a deep and unbiased understanding of that field. This not only educates you in the best possible way but also helps you envision the opportunities in your space.

A research paper is often the culmination of a wide range of deep and authentic practices surrounding a topic. When writing a research paper, the author thinks critically about the problem, performs rigorous research, evaluates their processes and sources, organizes their thoughts, and then writes. These genuinely-executed practices make for a good research paper.

If you’re struggling to build a habit of reading papers (like I am) on a regular basis, I’ve tried to break down the whole process. I've talked to researchers in the field, read a bunch of papers and blogs from distinguished researchers, and jotted down some techniques that you can follow.

Let’s start off by understanding what a research paper is and what it is NOT!

What is a Research Paper?

A research paper is a dense and detailed manuscript that compiles a thorough understanding of a problem or topic. It offers a proposed solution and further research along with the conditions under which it was deduced and carried out, the efficacy of the solution and the research performed, and potential loopholes in the study.

A research paper is written not only to provide an exceptional learning opportunity but also to pave the way for further advancements in the field. These papers help other scholars germinate the thought seed that can either lead to a new world of ideas or an innovative method of solving a longstanding problem.

What Research Papers are NOT

There is a common notion that a research paper is a well-informed summary of a problem or topic written by means of other sources.

But you shouldn't mistake it for a book or an opinionated account of an individual’s interpretation of a particular topic.

Why Should You Read Research Papers?

What I find fascinating about reading a good research paper is that you can draw on a profound study of a topic and engage with the community on a new perspective to understand what can be achieved in and around that topic.

I work at the intersection of instructional design and data science. Learning is part of my day-to-day responsibilities. If the source of my education is flawed or inefficient, I’d fail at my job in the long term. This applies to many other jobs in Science with a special focus on research.

There are three important reasons to read a research paper:

- Knowledge — Understanding the problem from the eyes of someone who has probably spent years solving it and has taken care of all the edge cases that you might not think of at the beginning.

- Exploration — Whether you have a pinpointed agenda or not, there is a very high chance that you will stumble upon an edge case or a shortcoming that is worth following up. With persistent efforts over a considerable amount of time, you can learn to use that knowledge to make a living.

- Research and review — One of the main reasons for writing a research paper is to further the development in the field. Researchers read papers to review them for conferences or to do a literature survey of a new field. For example, Yann LeCun’ s paper on integrating domain constraints into backpropagation set the foundation of modern computer vision back in 1989. After decades of research and development work, we have come so far that we're now perfecting problems like object detection and optimizing autonomous vehicles.

Not only that, with the help of the internet, you can extrapolate all of these reasons or benefits onto multiple business models. It can be an innovative state-of-the-art product, an efficient service model, a content creator, or a dream job where you are solving problems that matter to you.

Goals for Reading a Research Paper — What Should You Read About?

The first thing to do is to figure out your motivation for reading the paper. There are two main scenarios that might lead you to read a paper:

- Scenario 1 — You have a well-defined agenda/goal and you are deeply invested in a particular field. For example, you’re an NLP practitioner and you want to learn how GPT-4 has given us a breakthrough in NLP. This is always a nice scenario to be in as it offers clarity.

- Scenario 2 — You want to keep abreast of the developments in a host of areas, say how a new deep learning architecture has helped us solve a 50-year old biological problem of understanding protein structures. This is often the case for beginners or for people who consume their daily dose of news from research papers (yes, they exist!).

If you’re an inquisitive beginner with no starting point in mind, start with scenario 2. Shortlist a few topics you want to read about until you find an area that you find intriguing. This will eventually lead you to scenario 1.

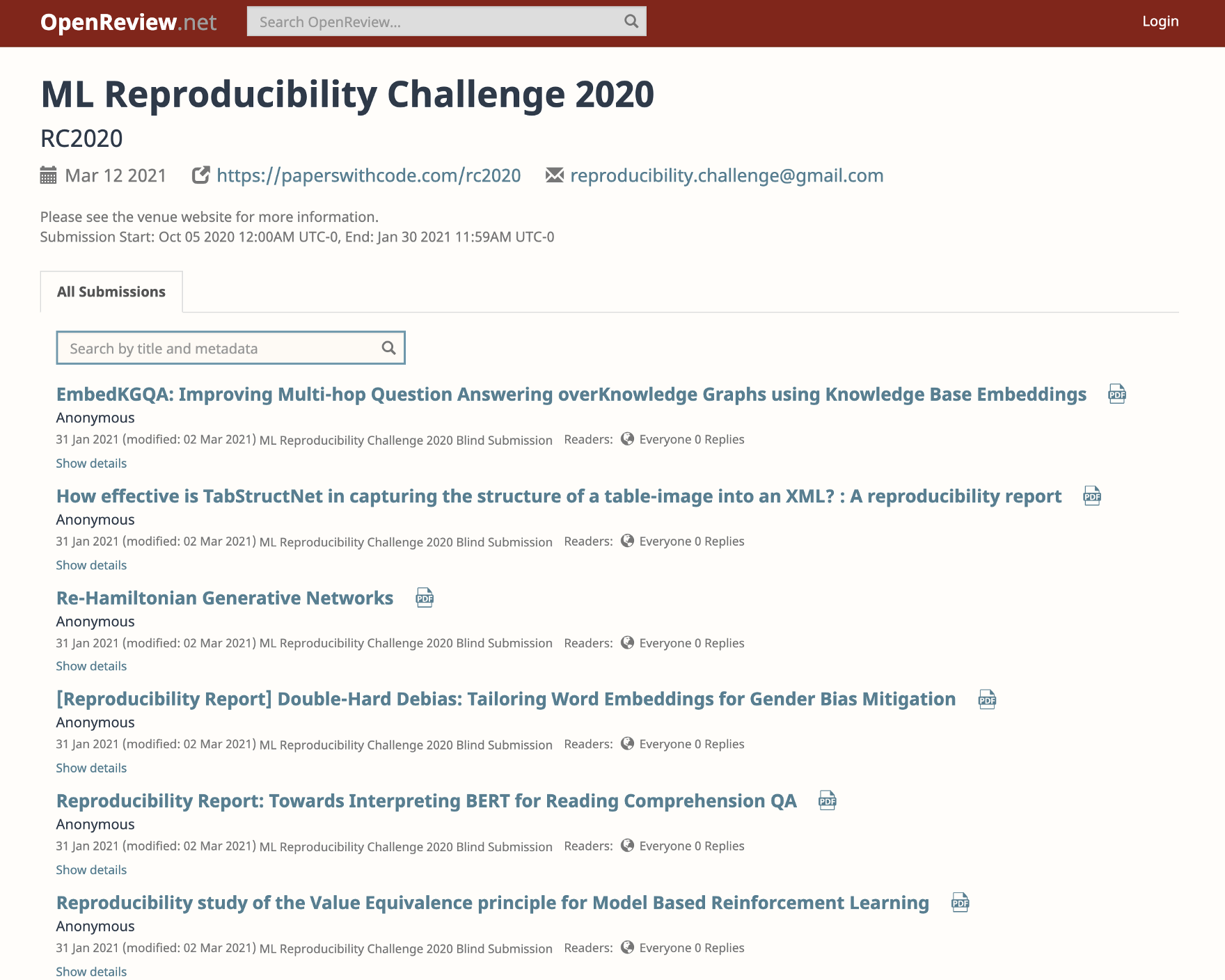

ML Reproducibility Challenge

In addition to these generic goals, if you need an end goal for your habit-building exercise of reading research papers, you should check out the ML reproducibility challenge.

You’ll find top-class papers from world-class conferences that are worth diving deep into and reproducing the results.

They conduct this challenge twice a year and they have one coming up in Spring 2021. You should study the past three versions of the challenge, and I’ll write a detailed post on what to expect, how to prepare, and so on.

Now you must be wondering – how can you find the right paper to read?

How to Find the Right Paper to Read

In order to get some ideas around this, I reached out to my friend, Anurag Ghosh who is a researcher at Microsoft. Anurag has been working at the crossover of computer vision, machine learning, and systems engineering.

Here are a few of his tips for getting started:

- Always pick an area you're interested in.

- Read a few good books or detailed blog posts on that topic and start diving deep by reading the papers referenced in those resources.

- Look for seminal papers around that topic. These are papers that report a major breakthrough in the field and offer a new method perspective with a huge potential for subsequent research in that field. Check out papers from the morning paper or C VF - test of time award/Helmholtz prize (if you're interested in computer vision).

- Check out books like Computer Vision: Algorithms and Applications by Richard Szeliski and look for the papers referenced there.

- Have and build a sense of community. Find people who share similar interests, and join groups/subreddits/discord channels where such activities are promoted.

In addition to these invaluable tips, there are a number of web applications that I’ve shortlisted that help me narrow my search for the right papers to read:

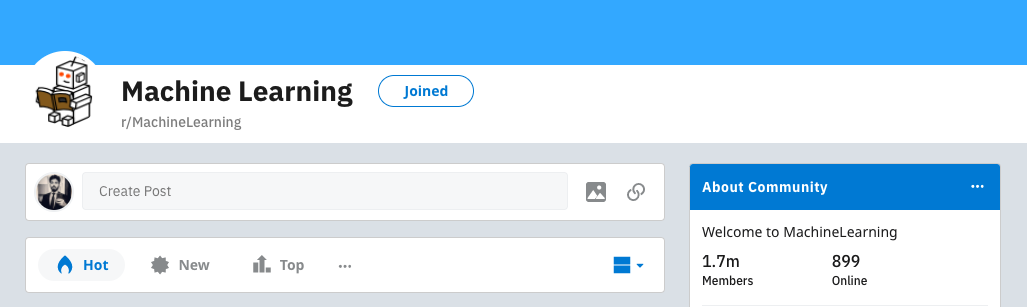

- r/MachineLearning — there are many researchers, practitioners, and engineers who share their work along with the papers they've found useful in achieving those results.

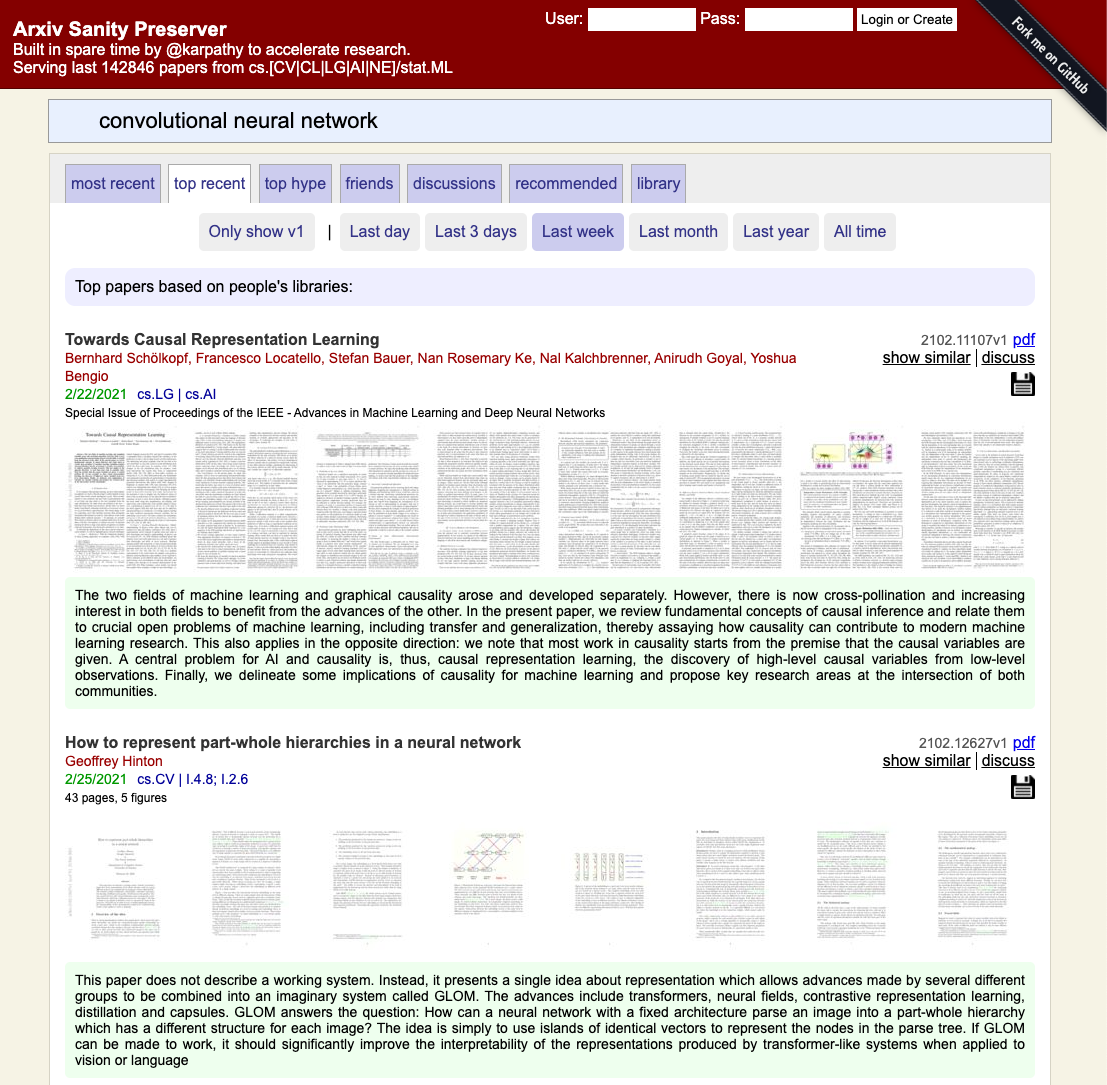

- Arxiv Sanity Preserver — built by Andrej Karpathy to accelerate research. It is a repository of 142,846 papers from computer science, machine learning, systems, AI, Stats, CV, and so on. It also offers a bunch of filters, powerful search functionality, and a discussion forum to make for a super useful research platform.

- Google Research — the research teams at Google are working on problems that have an impact on our everyday lives. They share their publications for individuals and teams to learn from, contribute to, and expedite research. They also have a Google AI blog that you can check out.

How to Read a Research Paper

After you have stocked your to-read list, then comes the process of reading these papers. Remember that NOT every paper is useful to read and we need a mechanism that can help us quickly screen papers that are worth reading.

To tackle this challenge, you can use this Three-Pass Approach by S. Keshav . This approach proposes that you read the paper in three passes instead of starting from the beginning and diving in deep until the end.

The three pass approach

- The first pass — is a quick scan to capture a high-level view of the paper. Read the title, abstract, and introduction carefully followed by the headings of the sections and subsections and lastly the conclusion. It should take you no more than 5–10 mins to figure out if you want to move to the second pass.

- The second pass — is a more focused read without checking for the technical proofs. You take down all the crucial notes, underline the key points in the margins. Carefully study the figures, diagrams, and illustrations. Review the graphs, mark relevant unread references for further reading. This helps you understand the background of the paper.

- The third pass — reaching this pass denotes that you’ve found a paper that you want to deeply understand or review. The key to the third pass is to reproduce the results of the paper. Check it for all the assumptions and jot down all the variations in your re-implementation and the original results. Make a note of all the ideas for future analysis. It should take 5–6 hours for beginners and 1–2 hours for experienced readers.

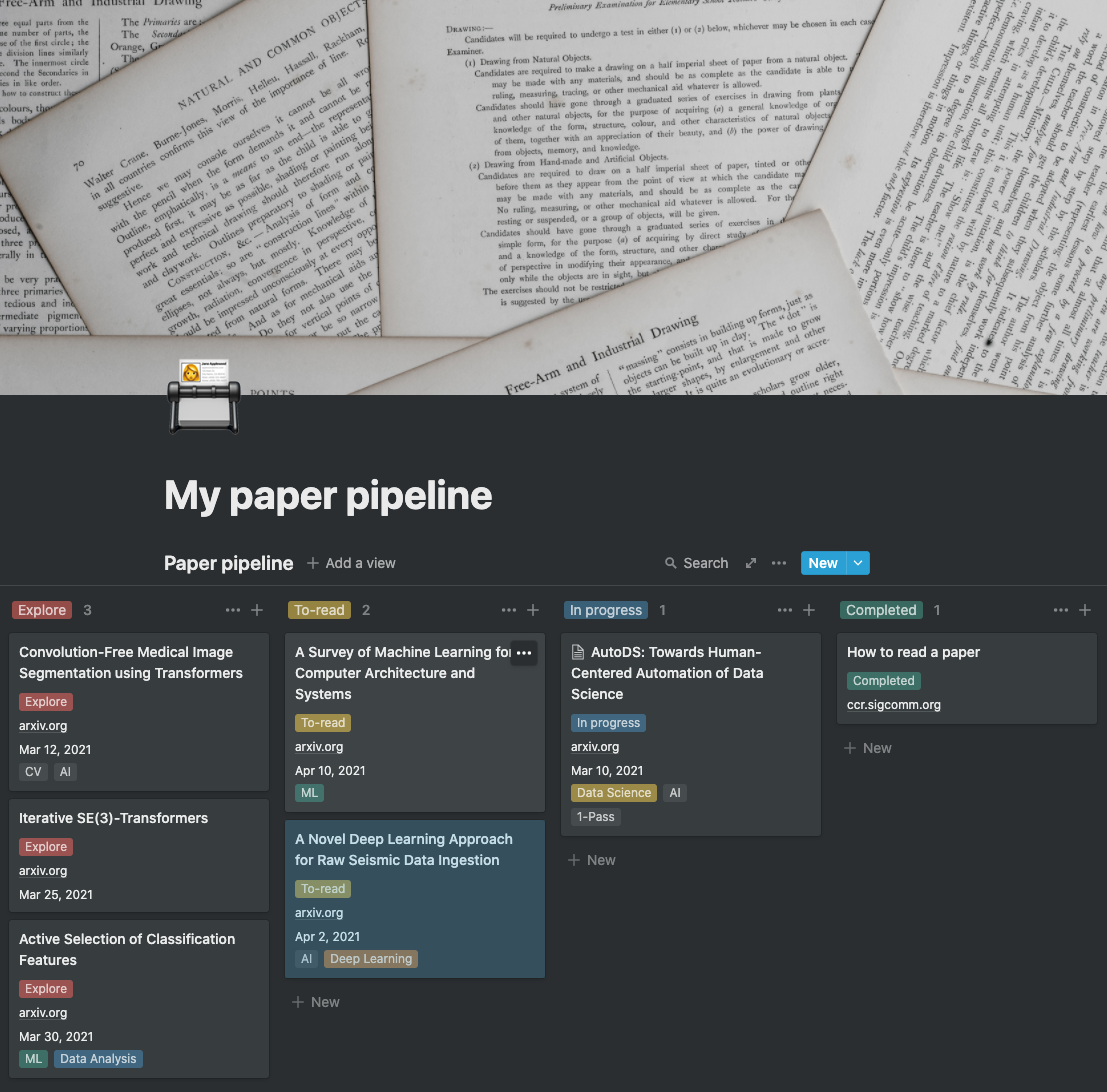

Tools and Software to Keep Track of Your Pipeline of Papers

If you’re sincere about reading research papers, your list of papers will soon grow into an overwhelming stack that is hard to keep track of. Fortunately, we have software that can help us set up a mechanism to manage our research.

Here are a bunch of them that you can use:

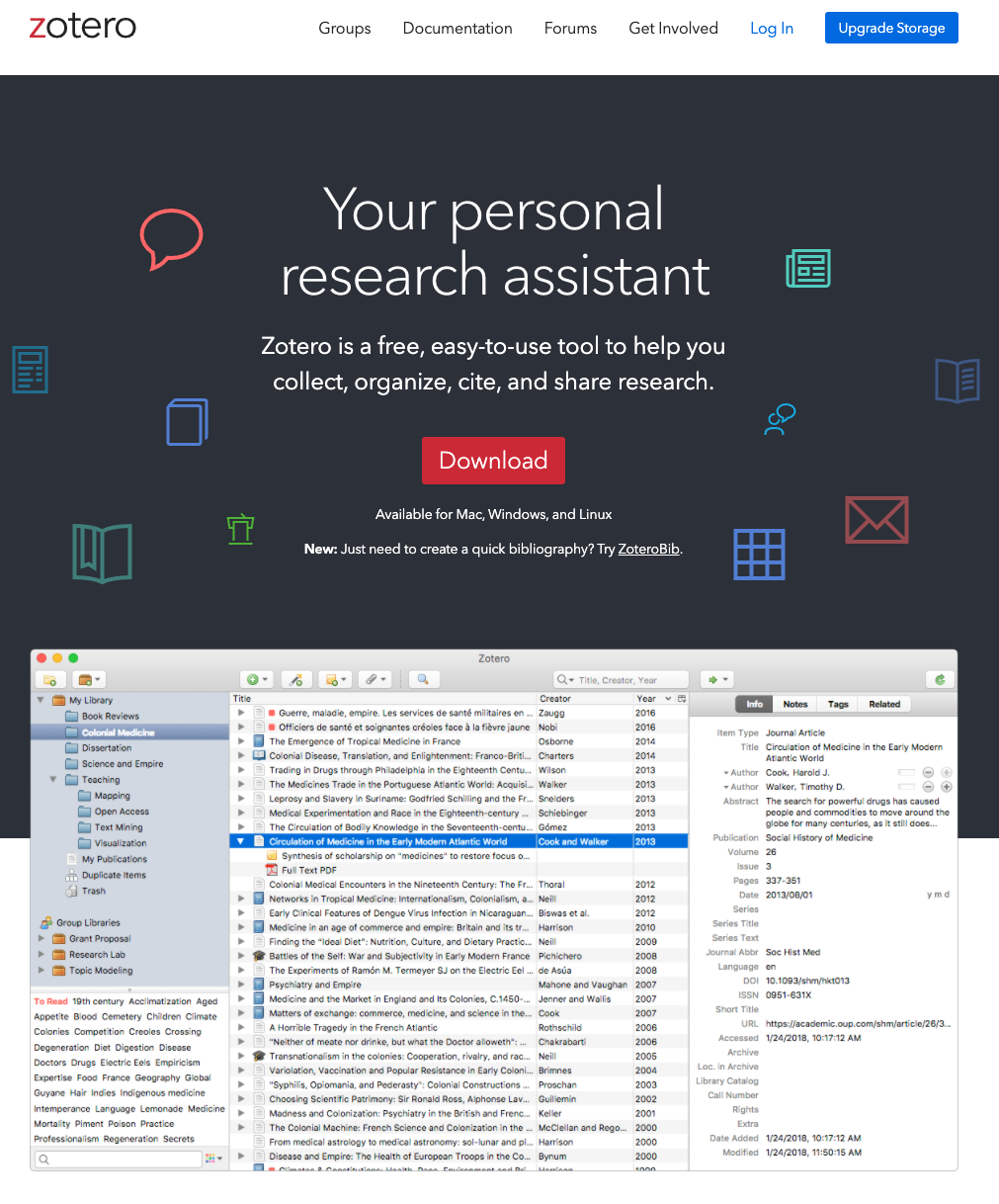

- Mendeley [not free] — you can add papers directly to your library from your browser, import documents, generate references and citations, collaborate with fellow researchers, and access your library from anywhere. This is mostly used by experienced researchers.