Patient Case #1: 27-Year-Old Woman With Bipolar Disorder

- Theresa Cerulli, MD

- Tina Matthews-Hayes, DNP, FNP, PMHNP

Custom Around the Practice Video Series

Experts in psychiatry review the case of a 27-year-old woman who presents for evaluation of a complex depressive disorder.

EP: 1 . Patient Case #1: 27-Year-Old Woman With Bipolar Disorder

Ep: 2 . clinical significance of bipolar disorder, ep: 3 . clinical impressions from patient case #1, ep: 4 . diagnosis of bipolar disorder, ep: 5 . treatment options for bipolar disorder, ep: 6 . patient case #2: 47-year-old man with treatment resistant depression (trd), ep: 7 . patient case #2 continued: novel second-generation antipsychotics, ep: 8 . role of telemedicine in bipolar disorder.

Michael E. Thase, MD : Hello and welcome to this Psychiatric Times™ Around the Practice , “Identification and Management of Bipolar Disorder. ”I’m Michael Thase, professor of psychiatry at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Joining me today are: Dr Gustavo Alva, the medical director of ATP Clinical Research in Costa Mesa, California; Dr Theresa Cerulli, the medical director of Cerulli and Associates in North Andover, Massachusetts; and Dr Tina Matthew-Hayes, a dual-certified nurse practitioner at Western PA Behavioral Health Resources in West Mifflin, Pennsylvania.

Today we are going to highlight challenges with identifying bipolar disorder, discuss strategies for optimizing treatment, comment on telehealth utilization, and walk through 2 interesting patient cases. We’ll also involve our audience by using several polling questions, and these results will be shared after the program.

Without further ado, welcome and let’s begin. Here’s our first polling question. What percentage of your patients with bipolar disorder have 1 or more co-occurring psychiatric condition? a. 10%, b. 10%-30%, c. 30%-50%, d. 50%-70%, or e. more than 70%.

Now, here’s our second polling question. What percentage of your referred patients with bipolar disorder were initially misdiagnosed? Would you say a. less than 10%, b. 10%-30%, c. 30%-50%, d. more than 50%, up to 70%, or e. greater than 70%.

We’re going to go ahead to patient case No. 1. This is a 27-year-old woman who’s presented for evaluation of a complex depressive syndrome. She has not benefitted from 2 recent trials of antidepressants—sertraline and escitalopram. This is her third lifetime depressive episode. It began back in the fall, and she described the episode as occurring right “out of the blue.” Further discussion revealed, however, that she had talked with several confidantes about her problems and that she realized she had been disappointed and frustrated for being passed over unfairly for a promotion at work. She had also been saddened by the unusually early death of her favorite aunt.

Now, our patient has a past history of ADHD [attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder], which was recognized when she was in middle school and for which she took methylphenidate for adolescence and much of her young adult life. As she was wrapping up with college, she decided that this medication sometimes disrupted her sleep and gave her an irritable edge, and decided that she might be better off not taking it. Her medical history was unremarkable. She is taking escitalopram at the time of our initial evaluation, and the dose was just reduced by her PCP [primary care physician]from 20 mg to 10 mg because she subjectively thought the medicine might actually be making her worse.

On the day of her first visit, we get a PHQ-9 [9-item Patient Health Questionnaire]. The score is 16, which is in the moderate depression range. She filled out the MDQ [Mood Disorder Questionnaire] and scored a whopping 10, which is not the highest possible score but it is higher than 95% of people who take this inventory.

At the time of our interview, our patient tells us that her No. 1 symptom is her low mood and her ease to tears. In fact, she was tearful during the interview. She also reports that her normal trouble concentrating, attributable to the ADHD, is actually substantially worse. Additionally, in contrast to her usual diet, she has a tendency to overeat and may have gained as much as 5 kg over the last 4 months. She reports an irregular sleep cycle and tends to have periods of hypersomnolence, especially on the weekends, and then days on end where she might sleep only 4 hours a night despite feeling tired.

Upon examination, her mood is positively reactive, and by that I mean she can lift her spirits in conversation, show some preserved sense of humor, and does not appear as severely depressed as she subjectively describes. Furthermore, she would say that in contrast to other times in her life when she’s been depressed, that she’s actually had no loss of libido, and in fact her libido might even be somewhat increased. Over the last month or so, she’s had several uncharacteristic casual hook-ups.

So the differential diagnosis for this patient included major depressive disorder, recurrent unipolar with mixed features, versus bipolar II disorder, with an antecedent history of ADHD. I think the high MDQ score and recurrent threshold level of mixed symptoms within a diagnosable depressive episode certainly increase the chances that this patient’s illness should be thought of on the bipolar spectrum. Of course, this formulation is strengthened by the fact that she has an early age of onset of recurrent depression, that her current episode, despite having mixed features, has reverse vegetative features as well. We also have the observation that antidepressant therapy has seemed to make her condition worse, not better.

Transcript Edited for Clarity

Dr. Thase is a professor of psychiatry at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Dr. Alva is the medical director of ATP Clinical Research in Costa Mesa, California.

Dr. Cerulli is the medical director of Cerulli and Associates in Andover, Massachusetts.

Dr. Tina Matthew-Hayes is a dual certified nurse practitioner at Western PA Behavioral Health Resources in West Mifflin, Pennsylvania.

The Week in Review: April 1-5

Blue Light, Depression, and Bipolar Disorder

An Update on Bipolar I Disorder

Four Myths About Lamotrigine

Recap: Mood Disorders 2024

Evidence-Based Novel Therapies for Bipolar Depression: Top 5 Takeaways

2 Commerce Drive Cranbury, NJ 08512

609-716-7777

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Contributors

- About the Authors

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Template for Case Studies

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 1: Preschooler with Emotional and Behavioral Difficulties p2-7

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 2: In Foster Care and Very Active p8-20

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 3: Aggression at a Young Age p21-25

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 4: Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Low Frustration Tolerance p26-34

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 5: Attention and Behavior Problems p35-45

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 6: Not Cooperating and Being Aggressive p46-52

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 7: Transgender Youth p53-60

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 8: Self-Harm and Suicidality p61-68

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 9: Intrusive Thoughts p69-74

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 10: Depressed Adolescent p75-82

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 11: Test Taking Anxiety p84-88

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 12: Stimulants and Mania p89-97

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 13: Depressed and Anxious in College p98-107

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 14: Depressed and Voices Say to Kill Myself p108-122

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 15: Not Doing Well in College p123-133

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 16: Depressed and Anxious p134-139

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 17: Hates Everyone, Angry Everyday p140-147

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 18: Anxiety and Insomnia p148-153

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 19: Stressed and Biting Fingers More p154-160

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 20: Stressed and Cutting p161-166

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 21: Migraines and Impaired p167-177

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 22: Night Terrors p178-183

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 23: Still Has Auditory Hallucinations with Olanzapine p184-193

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 24: Out of Control Eating with a History of Depression p194-205

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 25: Depressed and Anxious Postpartum p206-213

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 26: Opiates Are Ruining My Life p214-231

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 27: Blacking Out p232-247

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 28: Back in School and Cannot Focus p248-258

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 29: Feeling more Anxious and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Is Worse p259-264

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 30: Unsteady after Being on Risperidone p265-271

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 31: Thinks He May Be Depressed p272-283

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 32: Manic with Psychotic Features p284-296

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 33: Depression Post Brain Tumor p297-304

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 34: Feeling Paranoid p305-313

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 35: Pregnant and Anxious p314-321

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 36: Panic Attacks after Traumatic Incident p322-329

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 37: Depressed and Worried about Drinking p330-336

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 38: Telepsychiatry p337-348

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 39: Incarcerated and Substance Use Problems p349-361

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 40: Worried about a Brain Tumor p362-368

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 41: Still Crying about Her Father’s Death p369-373

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 42: Treatment after Rehab for Opiate Addiction p374-382

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 43: Depressed and Fatigued p383-390

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 44: Homeless and Problems with Alcohol p391-405

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 45: Renal Function Decreasing p406-419

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 46: Very Tired and Cannot Sleep p420-427

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 47: Withdrawn after Surgery p429-436

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 48: Lithium and the Older Adult p437-450

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 49: Worried about Father Dying p451-461

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 50: Older and Depressed p462-471

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 51: Seeing Dead People p472-483

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Case 52: Agitated and Clapping Hands p484-496

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Index by Diagnostic Category p497-500

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites List of Medications Referred to in the Cases p501-502

- Add To Remove From Your Favorites Clinical Practice Tools List p503-503

Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- April 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 4 CURRENT ISSUE pp.255-346

- March 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 3 pp.171-254

- February 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 2 pp.83-170

- January 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 1 pp.1-82

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

DSM-5 Clinical Cases

- Rachel A. Davis , M.D.

Search for more papers by this author

DSM-5 Clinical Cases makes the rather overwhelming DSM-5 much more accessible to mental health clinicians by using clinical examples—the way many clinicians learn best—to illustrate the changes in diagnostic criteria from DSM-IV-TR to DSM-5. More than 100 authors contributed to the 103 case vignettes and discussions in this book. Each case is concise but not oversimplified. The cases range from straightforward and typical to complicated and unusual, providing a nice repertoire of clinical material. The cases are realistic in that many portray scenarios that are complicated by confounding factors or in which not all information needed to make a diagnosis is available. The authors are candid in their discussions of difficulties arriving at the correct diagnoses, and they acknowledge the limitations of DSM-5 when appropriate.

The book is conveniently organized in a manner similar to DSM-5. The 19 chapters in DSM-5 Clinical Cases correspond to the first 19 chapters in section 2 of DSM-5. As in DSM-5, DSM-5 Clinical Cases begins with diagnoses that tend to manifest earlier in life and advances to diagnoses that usually occur later in life. Each chapter begins with a discussion of changes from DSM-IV. These changes are further explored in the cases that follow.

Each case vignette is titled with the presenting problem. The cases are formatted similarly throughout and include history of present illness, collateral information, past psychiatric history, social history, examination, any laboratory findings, any neurocognitive testing, and family history. This is followed by the diagnosis or diagnoses and the case discussion. In the discussions, the authors highlight the key symptoms relevant to DSM-5 criteria. They explore the differential diagnosis and explain their rational for arriving at their selected diagnoses versus others they considered as well. In addition, they discuss complicating factors that make the diagnoses less clear and often mention what additional information they would like to have. Each case is followed by a list of suggested readings.

As an example, case 6.1 is titled Depression. This case describes a 52-year-old man, “Mr. King,” presenting with the chief complaint of depressive symptoms for years, with minimal response to medication trials. The case goes on to describe that Mr. King had many anxieties with related compulsions. For example, he worried about contracting diseases such as HIV and would wash his hands repeatedly with bleach. He was able to function at work as a janitor by using gloves but otherwise lived a mostly isolative life. Examination was positive for a strong odor of bleach, an anxious, constricted affect, and insight that his fears and behaviors were “kinda crazy.” No laboratory findings or neurocognitive testing is mentioned.

The diagnoses given for this case are “OCD, with good or fair insight,” and “major depressive disorder.” The discussants acknowledge that evaluation for OCD can be difficult because most patients are not so forthcoming with their symptoms. DSM-5 definitions of obsessions and compulsions are reviewed, and the changes to the description of obsessions are highlighted: the term urge is used instead of impulse so as to minimize confusion with impulse-control disorders; the term unwanted instead of inappropriate is used; and obsessions are noted to generally (rather than always) cause marked anxiety or distress to reflect the research that not all obsessions result in marked anxiety or distress. The authors review the remaining DSM-5 criteria, that OCD symptoms must cause distress or impairment and must not be attributable to a substance use disorder, a medical condition, or another mental disorder. They discuss the two specifiers: degree of insight and current or past history of a tic disorder. They briefly explore the differential diagnosis, noting the importance of considering anxiety disorders and distinguishing the obsessions of OCD from the ruminations of major depressive disorder. They also point out the importance of looking for comorbid diagnoses, for example, body dysmorphic disorder and hoarding disorder.

This brief case, presented and discussed in less than three pages, leaves the reader with an overall understanding of the diagnostic criteria for OCD, as well as a good sense of the changes in DSM-5.

DSM-5 Clinical Cases is easy to read, interesting, and clinically relevant. It will improve the reader’s ability to apply the DSM-5 diagnostic classification system to real-life practice and highlights many nuances to DSM-5 that one might otherwise miss. This book will serve as a valuable supplementary manual for clinicians across many different stages and settings of practice. It may well be a more practical and efficient way to learn the DSM changes than the DSM-5 itself.

The author reports no financial relationships with commercial interests.

- Cited by None

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Psychiatry

- v.61(6); Nov-Dec 2019

Case presentation in academic psychiatry: The clinical applications, purposes, and structure of formulation and summary

Narayana manjunatha.

Department of Psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

INTRODUCTION

Case presentation in an academic psychiatry traditionally follows one of the following three formats: 4DP format (ideal and lengthy format; described in the following section), “Case Summary” (CS) (medium format), or “Case Formulation” (CF) (short format), in order of the decreasing length, duration, and the gradual transition from the use of layman terms (in the history with a goal of layman understanding) to technical terms (in diagnostic formulation [DF] with a goal to communicate with professionals). However, the medium and short formats (CS and CF) are often preferred as a rule rather than exception routinely than the ideal and lengthy 4DP format in the area of academic psychiatry.

An ideal case presentation in academic psychiatry follows 4DP format: first is the “Detailed presentations of all clinical information,” second is the “Diagnostic summary” (DS) (it is optional, see below), third is the “Diagnostic formulation,” fourth is the Diagnosis or differential diagnosis (usually International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10)/Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 [DSM-5]) and discussion of diagnosis with points in favor and against, and finally is the “Plan of management.” The goal of this article is to overview the clinical applications, purposes, and structure of the “formulation” and “summary” in this article with review from published literatures. Table 1 represents these formats of presentation graphically.

Graphical representation of different formats of case presentations in psychiatry

*Includes complete history, physical examination, and detailed mental status examination. DD – Differential diagnosis

CONCEPTS OF “FORMULATION” AND “SUMMARY:” SHORTCOMINGS

Despite the availability of substantial literatures, the concepts of “formulation” and “summary” are rather confusing concepts in academic psychiatry, especially with psychiatric residents. There are few shortcomings of these concepts causing this confusion. The presence of various models of formulations in psychiatric literatures is one of the reasons for this confusion such as “psychodynamic formulation,” “psychotherapeutic formulation,” and “cultural formulation.” It is essential to understand the purposes of the existing models of these psychiatric formulations. The “psychodynamic formulation” focuses on psychodynamic understanding of the problems of patients and may involve interventions with psychodynamic psychotherapy, the “psychotherapeutic formulation” aims to understand the problems of patients and helps to choose the different schools of psychotherapy, and the “cultural psychiatric formulation” focuses on understanding of the patient's problems from his/her cultural background. Lack of clarity on this pair of terminologies such as “case formulation” versus “diagnostic formulation” and “case summary” versus “diagnostic summary” in published literatures is another significant reason for confusion. Kuruvilla and Kuruvilla[ 1 ] in their article entitled “diagnostic formulation” denotes the inclusion of diagnosis (at least the differential diagnosis) and plan of management in the formulation. The author wishes to convey that “diagnostic formulation” and “case formulation” (formulating a case) are rather different concepts with different purposes. The concept “CF” denotes for formulating a case for the purpose of both diagnostic and management purposes, whereas “DF” with the term “diagnostic” denotes diagnostic point of view only (where term itself denotes diagnosis), which excludes the “plan of management.” The similar explanation is offered to differentiate “CS” and “DS.” Often, these pairs of terminology are used synonymously causing confusion. Further discussion in this article is based on the above explanations of all these four terms. However, if examiners/teachers ask to present DF, it means formulating his/her case for the purpose of diagnostic purpose, which need not include the management plan. For the sake of better clarity, the author wishes to discuss student-friendly models of formulation, summary, and diagnosis, edited by Professor David Goldberg. Along with experienced teachers, trainees themselves are involved in deriving these concepts in explaining Professor D. Goldberg's concepts which is an interesting point.

CLINICAL APPLICATION OF DIAGNOSTIC FORMULATION AND SUMMARY

Often, the choice of presentation from one of either “DS” or “DF” in academic psychiatry depends on whether the detailed clinical information is presented or not. If detailed clinical information is presented, “DS” may be skipped and proceed directly to presentation of the third step of ideal 4DP format, i.e., “DF.” In case detailed clinical information is not presented for any reasons, the case presentation may begin with “DS” and then may proceed to “DF” (however, it is optional). In either of the ways, both “DS” and “DF” are followed by the fourth step of ideal 4DP format, i.e., the “diagnosis or differential diagnosis” (usually ICD-10 and DSM 5) and discussion of diagnosis with points in favor and against, and finally is the “plan of management.”

The choice of the presentation either “DS”/“DF”, at times, depends on the availability of time with examiners/listeners/faculties. When ample of time are available, the examiners/teachers ask residents to present a detailed presentation of all clinical data in the usual 4DP format of “presenting complaint,” “history of presenting illness,” etc., followed by “DF,” and then plan of management, and this format has the minimal scope of “DS” presentation. However, whenever time is a constraint, residents shall be asked to present the “DS” without a detailed presentation of clinical data followed by with or without “DF.” In any case, psychiatric residents shall be encouraged to learn both DS and DF for any eventuality during examination.

As discussed above, the “CF” traditionally includes only the last three steps (3 rd , 4 th , and 5 th ) of 4DP format of psychiatric case presentation. This has relevance from psychodynamic explanation of psychiatric disorders. In view of the significant development in the neurobiology of psychiatric disorders in the last few decades and high dependency of making clinical diagnosis based on the current classificatory system (ICD-10 and DSM 5), the “DF” is preferred which excludes the plan of management than the “CF” as authors believe that the presentation of the “plan of management” itself is an important skill which is expected from psychiatric residents during training and examination. However, whenever a psychiatric resident is asked to present “CF,” he/she shall include the third to fifth steps of ideal format.

PURPOSE OF DIAGNOSTIC FORMULATION AND SUMMARY

The important goal of the “DF” is to facilitate the communication of clinical information of patients with another professional/s who are familiar with technical jargons (i.e., psychopathological/psychiatric terminology), whereas the purpose of “DS” is to convey the clinical information of patients to lay persons and/or nonprofessionals and comprises all the components of a DF, but in layman's terminology. The contents of DS may be used for the purpose of psychoeducation to patients and their family.

STRUCTURE OF DIAGNOSTIC FORMULATION AND SUMMARY

The purposes of “DF” and “DS” are important to understand their structure or contents. Since “DF” is targeted for professionals, the technical jargons are used in its content, whereas “DS” is targeted for lay persons or nonprofessionals, and then layman terms are used in its content. The “DF” should be quite brief to just re-orientating the listener to the salient features of the case, often just the key demographics and major diagnostic criteria described in technical terms in as less words as possible without repetition of any word/s. The technical jargons in “DF” often include the terminology of descriptive psychopathology or diagnostic points of classificatory system (ICD-10 and DSM-5). In simple words, the structure of both DF and DS is, more or less, similar in contents, but the difference lies in the use of technical terms and layman's terms, respectively, in its structure/contents. Further details of the structure of DF and DS are discussed below in the proposed format and case vignettes.

RECOMMENDED SIZE AND TIME TO PRESENT “DIAGNOSTIC FORMULATION AND “DIAGNOSTIC SUMMARY

The completed DF shall last for about 5 min, and the recommended length for a written version is not more than one side of a A4 paper when typed,[ 1 ] which is equivalent to 10 to 15 sentences, whereas the completed DS should be short enough to cover about two sides of a A4 paper when typed,[ 2 ] which should not be more than 10 min.

SUMMARY, FORMULATION, AND DIAGNOSIS: MODEL BY PROFESSOR DAVID GOLDBERG

The following paragraphs exerted in italic (without any edition to preserve the semantic) from “ The Maudsley Handbook of Practical Psychiatry ” were edited by Professor David Goldberg. The author feels that these paragraphs are important to understand the difference between the process of summary, formulation, and diagnosis. The author intentionally deleted diagnostic points and management plan from the discussion to keep focus on DF only.

A SUMMARY is a descriptive account of collected data: Objective and impartial. In contrast, a FORMULATION is a clinical opinion: Weighing up the pros and cons of conflicting evidence, that leads to a diagnostic choice. An opinion inevitably implies a subjective view point, by virtue of assigning relative importance to each piece of evidence; in doing so, both theoretical bias and past personal experience invariably come to play. No matter how accurate the final verdict, an analysis is inextricably bound up with subjective judgments and decisions. When assigning the same patient, two experts may produce two similar summaries, but two different formulations with divergent conclusions. This is the fundamental difference: A SUMMARY is a descriptive, whereas a formulation is analytical. Therefore, a summary calls for the qualities of thoroughness, restraint, and objectivity, while a formulation demands the composite skill of methodological thinking, incisive analysis and intelligent presentation.

THE SUMMARY

It is an important document which should be drawn up with care. Its purpose is to provide a concise description of all the important aspects of the case, enabling others who are unfamiliar with the patient to grasp the essential features of the problem without needing to search elsewhere for further information. The completed summary should be short enough to cover about two sides of A4 paper when typed.

THE FORMULATION

Formulating a case with clarity and precision is probably the most testing yet challenging and crucial part of a psychiatric assessment. The skills of writing a good formulation depend upon the ability to differentiate what are merely the incidental and circumstantial biographical details from what are the salient and discriminatory features and it is this that forms the cornerstone of a clinical diagnosis. Certain features are discriminatory because they support one diagnosis as more likely candidate and discount another diagnosis as less likely.

THE DIAGNOSIS AND FORMULATION

A diagnosis involves a nomothetic (literally “law-giving”) process. This means that all cases included within the identified category have one or more properties in common. By contrast, the formulation is an idiographic process (literally “picture of the individual”). This means that it includes the unique characteristics of each patient's case which are needed for the process of management. So, while nomothetic processes are the only way we can advance knowledge about a disease, we use idiographic methods to understand and study the individual.

THE FORMAT OF THE FORMULATION

The formulation follows a logical sequence.

Demographic data: Begins with name, age, occupation, and marital status of the patient.

Descriptive formulation: Describe the nature of onset,– for example, acute or insidious; the total duration of the present illness; and course; for instance, cyclic or deteriorating. Then list of the main phenomena (namely, symptoms and signs) that characterize the disorder. As you become more experienced you should try to be selective by featuring those phenomena that are most important, either because of their diagnostic specificity or because of their predominance in severity or duration. Avoids long lists of minor or transient symptoms and negative findings. These basic data are chiefly derived from history of the present illness; the mental state and physical examinations are used to determine the syndrome diagnosis in the next section. Note that this is not usually the place to bring in other aspects of the history: That comes later. If we know the diagnosis of a previous episode of mental illness, this should also be taken into account, but remember, the present disorder may not be connected and the diagnosis may be different.

Etiology: The various factors that have contributed should be evident mainly from the family and personal histories, the history of previous illness, and the premorbid personality. Try to answer two questions: Why this patient developed this particular disorder, and why has the disorder developed at this particular time?

PROPOSED FORMATS OF “DIAGNOSTIC SUMMARY” AND “DIAGNOSTIC FORMULATION”

The general formats of “DS” and “DF” are essentially similar with slight changes in order of the presentation, which aim to reduce the number of words as well as to avoid the repetition of words.

- Sociodemographic data

- Elaboration of chief complaint with focus on positive aspects with relevant negative aspects: Presenting the long list of minor or transient symptoms and negative findings is advisable in DS to differentiate in the differential diagnosis which may be avoided in DF. Treatment history also needs to be briefed here. Please note that layman terms shall be used in DS, whereas technical jargons are used in DF

- Past psychiatric and medical history: Briefly describe the symptoms of the past psychiatric disorder and then write possible name for that psychiatric disorder in DS, whereas directly write psychiatric diagnosis in DF

- Family history: Briefly describe symptoms and age of the onset of psychiatric disorder, and then write possible name of that psychiatric disorder in DS, whereas directly write psychiatric diagnosis in DF

- Personal history: Briefly describe the positive aspects of personal history in DS, whereas the use of possible technical jargon in DF is advised

- Premorbid personality: Describe briefly each headings of premorbid personality followed by impression in DS, whereas give directly the impression in DF, i.e., well-adjusted or schizoid/schizotypal/anxious avoidant/personality traits/disorder

- Physical examination: Briefly describe positive findings in DS, whereas technical comments in DF using medial jargons

- Mental Status Examination (MSE): Briefly describe positive findings first, then give impression of that finding using psychopathological terms in DS, whereas directly write technical jargons using psychopathological terms in DF. Please note here that, in case of DF, the psychopathological findings in MSE may be similar to the history of presenting illness (HOPI). In this case, mention as “concurred with HOPI findings” in order to avoid repetition of terms (see in case vignette of DF).

Note: Please note that findings from the family and personal histories, the history of previous illness, and the premorbid personality give the etiology of presentation of case. The sequence in the format of DS may be preferred in the same way as above, whereas in DF, etiology-related history such as past, family, and personal histories as well as premorbid personality may be presented before presenting complaints, which reduce the number of words by avoiding the repetition of words (please see in case vignettes of DS and DF).

CASE VIGNETTES: DEMONSTRATION OF THE STRUCTURE OF “DS “ AND “DF “

Diagnostic summary.

A 36-year-old married and postgraduation-completed male, currently working as a software professional hailing from urban-middle socioeconomic background from Bengaluru, presented with adequate and reliable information of 20-day illness of abrupt onset and continuous course characterized by overcheerfulness, hyperactivity, and unable to sit at one place, overtalkativeness, overfamiliarity, and overspending most of the time in the last 20 days and false and firm claims that he is a minister and demand respect from people in the last 12 days, with decreased need of sleep and appetite disturbance along with socio-occupational dysfunction in the absence of organicity and schizophrenic and depressive symptoms. There was a family history of episodic mental illness suggestive of bipolar disorder in first-degree relative with age of onset at about 23 years with maintaining asymptomatic with lithium prophylaxis and past history suggestive of episodic mental illness of bipolar disorder in the last 12 years with four similar manic episodes with each 3–5 months' duration and another three depressive episodes characterized by depressed mood, reduced interest, easy fatiguability, and early-morning awakening for about 6–8 months with poor medication adherence, with nil significant personal history and well-adjusted premorbid personality. No abnormality was found in physical examination. MSE reveals overfamiliarity; easily established rapport; increased tone, tempo, and volume in speech; pacing around excessive suggestive of increased psychomotor activity; expression and observation of overcheerfulness suggestive of elated mood and affect; and delusion of grandiosity of identity for the above claim with impaired judgment and partial insight (total 250 words).

Diagnostic formulation

Mr. Sri, a 36-year-old married and postgraduation-completed male, currently working as a software professional hailing from urban-middle socio-economic status from Bengaluru, with a family history of bipolar disorder in first-degree relative with maintaining remission on lithium prophylaxis, with past history of four manic episodes and three depressive episodes in last 12 years with poor medication adherence, with nil significant personal history and well-adjusted pre-morbid personality, presented with adequate and reliable information of 20-day illness of abrupt onset and continuous course with characterized by elated mood, increased psychomotor activity, inflated self-esteem, excessive and rapid speech, overfamiliarity, and delusion of grandiosity of identity in the last 12 days with severe bio-socio-occupational dysfunction. No abnormality was found in physical examination. MSE is concurred with the above psychopathology with impaired judgment and impaired insight (total 131 words).

Please note that the above case vignettes are not exclusive and minor variation/s are still possible.

The aims of CF/CS are different from that of DF/DS. CF/CS focuses on understanding of the case-as-whole, but DF/DS aims for diagnostic points of view. The clinical applications, purposes, and structure of DF and DS are different. The authors explained hypothetical explanation of case presentation in academic psychiatry, which we feel is relevant in order to reduce the confusion in minds of present and prospective psychiatric residents. The author hope that these hypothetical explanations explained here is welcomed by the community of academic psychiatry.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Learning DSM-5 by case example

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

285 Previews

10 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station27.cebu on August 19, 2022

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Identification of factors associated with hospitalization in an outpatient population with mental health conditions: a case–control study.

- 1 Pôle Centre Rive Gauche, CH Le Vinatier, Bron, France

- 2 Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, Villeurbanne, France

- 3 Pôle Santé Publique, Hospices Civils de Lyon, Lyon, France

- 4 UMR 5992 CNRS, U1028 INSERM, Centre de Recherche en Neurosciences de Lyon, Bron, France

- 5 Hospices Civils de Lyon, Lyon, France

- 6 UMR 5229 CNRS, Centre Ressource de Réhabilitation psychosociale, Le Vinatier, Bron, France

Introduction: Addressing relevant determinants for preserved person-centered rehabilitation in mental health is still a major challenge. Little research focuses on factors associated with psychiatric hospitalization in exclusive outpatient settings. Some variables have been identified, but evidence across studies is inconsistent. This study aimed to identify and confirm factors associated with hospitalization in a specific outpatient population.

Methods: A retrospective monocentric case-control study with 617 adult outpatients (216 cases and 401 controls) from a French community-based care facility was conducted. Participants had an index outpatient consultation between June 2021 and February 2023. All cases, who were patients with a psychiatric hospitalization from the day after the index outpatient consultation and up to 1 year later, have been included. Controls have been randomly selected from the same facility and did not experience a psychiatric hospitalization in the 12 months following the index outpatient consultation. Data collection was performed from electronic medical records. Sociodemographic, psychiatric diagnosis, historical issues, lifestyle, and follow-up-related variables were collected retrospectively. Uni- and bivariate analyses were performed, followed by a multivariable logistic regression.

Results: Visit to a psychiatric emergency within a year (adjusted odds ratio (aOR): 13.02, 95% confidence interval (CI): 7.32–23.97), drug treatment discontinuation within a year (aOR: 6.43, 95% CI: 3.52–12.03), history of mental healthcare without consent (aOR: 5.48, 95% CI: 3.10–10.06), medical follow-up discontinuation within a year (aOR: 3.17, 95% CI: 1.70–5.95), history of attempted suicide (aOR: 2.50, 95% CI: 1.48–4.30) and unskilled job (aOR: 0.26, 95% CI: 0.10–0.65) are the independent variables found associated with hospitalization for followed up outpatients.

Conclusions: Public health policies and tools at the local and national levels should be adapted to target the identified individual determinants in order to prevent outpatients from being hospitalized.

1 Introduction

The deinstitutionalization process in psychiatry began in the late twentieth century. This shift, especially seen in high-income countries, consists of a decrease in specialized psychiatric hospital beds for an increase of patients with a mental health condition, followed up in general medical hospitals, community-based care, and various outpatient settings ( 1 ). Between the mid-twentieth century and the 1990s, the number of psychiatric beds dropped to more than 80% in most western regions around the world ( 1 ).

However, the transition from an inpatient setting paradigm to an outpatient one needs to be carefully organized, with the necessary and appropriate structures and funding. Indeed, patients who suffer from a mental health disease need a deep consideration of the multifaceted world in which they live, to integrate and adapt their rehabilitation process for the outside world. The strengthening of community services has been heterogenous around the world ( 1 ). This deinstitutionalization failed, for example, in many places in the USA, leading to an increase in homelessness and crime among people with psychiatric diseases in the 1990s ( 2 ). More recently, there are still concerns about the good transitioning process that have been raised in central and eastern Europe, with a large body of evidence showing failures in deinstitutionalization and reinstitutionalization outcomes. Some of the causes found are lack of personal assistance, development and adaptation of social housing, and cuts to social support ( 3 ). The limited scaling up of community-based and primary care mental health services has also been identified as a failure factor of deinstitutionalization, along with fundamental concerns with the model. A deeper work on addressing social determinants is indeed also evoked, which are known to be fundamental structural drivers of mental illness ( 1 ). A relatively recent dramatic event that has to be remembered regarding the deinstitutionalization failure has been the “Life Esidimeni scandal” in 2016 in South Africa. Qualified as a humanitarian crisis, this event caused the deaths of a thousand psychiatric patients (94 according to an official report issued in 2017 ( 4 )) following their transfer from an inpatient setting to multiple outpatient settings without the appropriate care and follow-up required. Indeed, the cut in this 2,000-bed facility budget led to patients’ discharge regardless of individual autonomy and psychosocial disability into inadequately resourced nongovernmental facilities ( 5 ).

Deinstitutionalization requires strong, continuous efforts and should always stay person-centered. In this approach, the multidisciplinary team caring for the patient must bear in mind the individual factors that can predict the maintained recovery of the patient in the outpatient setting ( 6 ). Few settings succeed yet to address all structural determinants, even in high-income countries ( 1 ). Indeed, the Lancet Commission on Global Mental Health and Sustainable Development reminded us that regarding mental health, all countries are “developing” due to the relative underfunding of mental health services in relation to the burden of the condition ( 7 ). Ways to achieve success with deinstitutionalization may involve legislation with a mandate to establish community-based services (like in Italy ( 8 )) and to adapt them to a local context. Improvements will probably require a multitude of paradigm shifts within these structures, considering factors enabling their enhancement. If no adequate care is provided during deinstitutionalization or after it, patients may relapse after being discharged from the hospital and consequently readmitted. Many studies therefore considered readmission rate to be an indicator for intervention studies ( 1 ) and to identify protective and risk factors of relapses ( 9 ) ( 10 , 11 ).

A rich scientific literature is available on the study of risk factors of hospitalization in patients suffering from mental health pathologies. Nonexhaustively, for depression ( 12 ), the type of illness diagnosis, psychiatric comorbidity, treatment-related factors, and sociodemographic factors were associated with hospitalization. For bipolar disorders ( 13 ), characteristics of the index hospitalization (transfer, discharge disposition, length of stay), all-cause acute health service utilization in the year prior to it, and comorbidity were identified. For schizophrenia ( 14 , 15 ), recent medical follow-up discontinuation, medication nonadherence, life events, comorbidity, sex, age, and medication type were variables associated with hospitalization. Finally, for other psychiatric conditions ( 16 ) ( 9 , 10 ) ( 17 ) ( 11 ) ( 18 ), factors associated with hospitalization were shown to be recent medical follow-up discontinuation, multiple psychiatric hospitalization history, history of mental healthcare without consent, social isolation, socioeconomic status, violence history, psychiatric diagnosis, and patient’s satisfaction with treatment. A suicide attempt was found to be a risk factor for hospitalization in some studies and a protective factor at 1 year in others.

Nonetheless, the studies cited above only evaluate risk factors for readmission, i.e., for patients that are originally coming from an inpatient hospital setting. Literature focusing on an exclusive outpatient setting is scarce ( 19 , 20 ). It confirmed some previously identified risk factors in studies with an inpatient setting, such as alcohol/substance use, family history of mental health disease, and marital status, but have also diverging results for negative attitude/poor compliance with medication, identified by Antonio Ciudad et al. ( 20 ) as lowering the hazard of relapse during outpatient follow-up.

A systematic review of the literature carried out by Donisi et al. ( 11 ) additionally underlined some inhomogeneous results for identified risk factors associated with readmissions regarding sociodemographic variables, and a literature weakness for social support, considered only in a few papers. Furthermore, the authors emphasized that some factors were only identified in uni- or bivariate analyses and not in multiple regression.

More people are followed up in outpatient settings, and the minimal use of hospitalization remains a challenge in mental health. This study is of interest to mental health professionals and policymakers because more data on factors associated with hospitalization in followed up outpatients could help tailor appropriate follow-up care and adapt existing tools to reduce the need for hospitalization. Our study, therefore, aimed to identify and confirm risk factors of hospitalization in a specific outpatient population.

2.1 Study design

We conducted an observational, retrospective, monocentric case-control study based on hospitalization in one of the largest university-affiliated public psychiatric hospitals in France, with around 500 beds and 26,500 patients followed up on an outpatient basis, the Centre Hospitalier le Vinatier (CHV) in Bron. The CHV has several community-based care facilities called “Centre Médico-Psychologique” or “CMP”, providing medical–psychological and social consultations to anyone experiencing psychological difficulties. The present study was made in one of them. We reported this case-control study according to Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE). For details, see Supplementary File 1 .

This retrospective study investigated the data from patients followed up in an outpatient setting from June 2021 to February 2023. This study period has been chosen in order not to have repercussions of the health restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic on our variables. The studied sample comes from the Centre Médico-Psychologique Centre Rive Gauche facility, administratively attached to the CHV but which has an independent operation for outpatients requiring mental healthcare in a defined geographic area (third, sixth, and eighth districts of Lyon).

In this facility, participants were eligible if they were aged 18 or older and had at least one outpatient psychiatric medical consultation between June 2021 and February 2023 (defined as the index consultation).

The sample size for this study was determined considering an odds ratio of 1.5 to 3 clinically meaningful based on previous literature. With a significance level of 0.05, a type I error of 0.025, and a power of 0.9, the required sample size was calculated using R and its Epicalc package 2.9.0.1. An estimate was then made with the lowest and highest expected frequencies for the studied variables. An ideal sample size was calculated and ranged between 807 and 423, with an approximate 1:2 case/control ratio.

2.3 Outcome

The studied outcome was full psychiatric hospitalization from the day after the index outpatient consultation and up to 1 year later. Full psychiatric hospitalization was defined in this study as more than 24 h of hospitalization in a psychiatric hospital. Thus, participants who had this outcome of interest were referred to as cases, whereas others who did not have the outcome of interest were referred to as controls.

2.4 Selection of cases and controls

Cases were patients who had a full psychiatric hospitalization from the day after the index outpatient consultation and up to 1 year later.

Controls were patients who did not experience full psychiatric hospitalization in the 12 months following the index outpatient consultation (therefore, controls have an index outpatient consultation before February 2022 to have at least a 1-year psychiatric hospitalization-free period).

All cases in the sample responding to the case definition were included ( n = 216).

Controls ( n = 401) were then randomly selected from the sample list of patients who met the definition of controls in order to approximately respect a 1:2 case/control ratio and the sample size determination. The random selection was performed with simple random sampling using computer-generated random numbers to ensure an unbiased selection process.

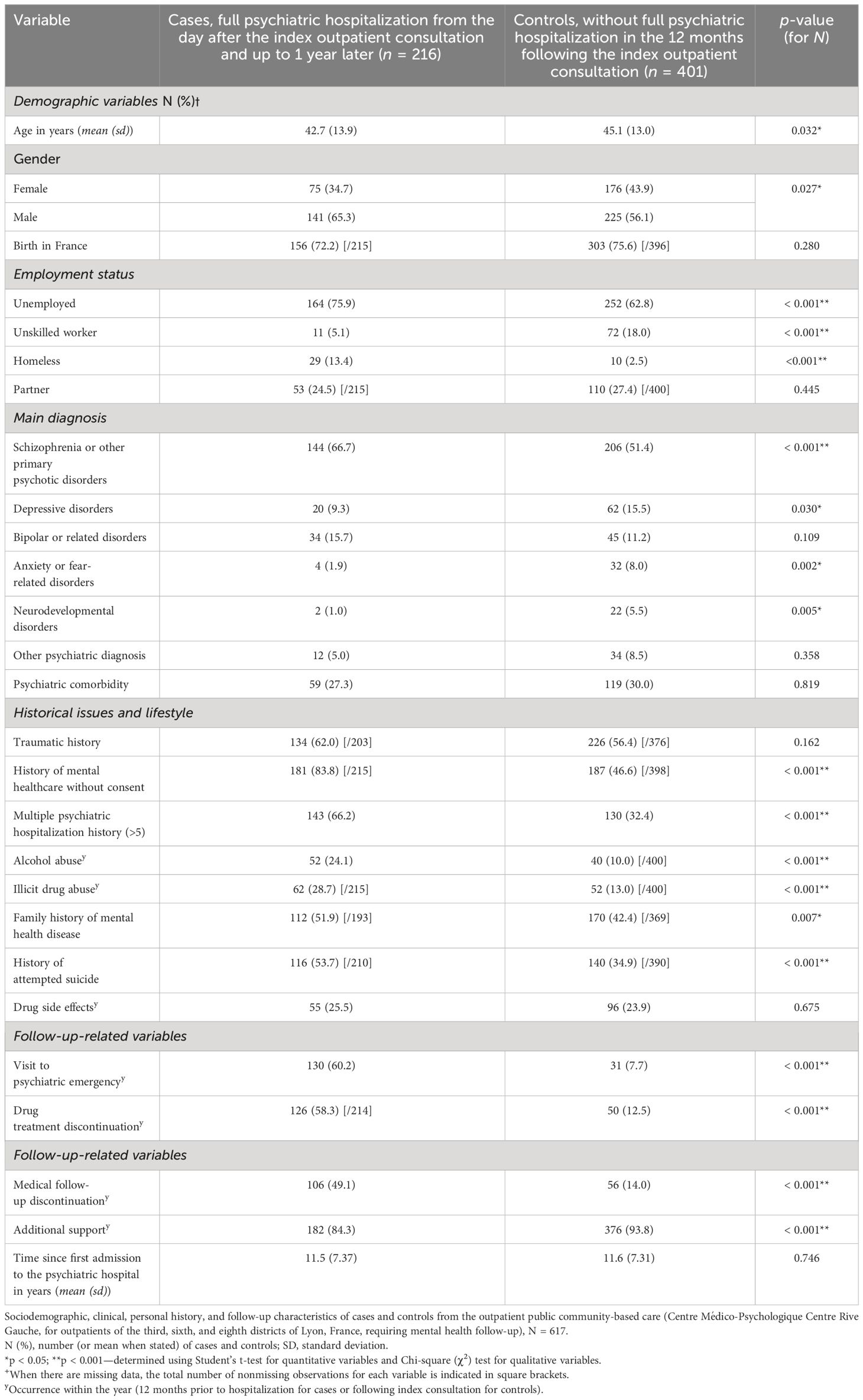

All the detailed characteristics of cases and controls can be found in Table 1 .

Table 1 Descriptive analysis.

2.5 Variables

The following exposure or potential confounder variables were collected retrospectively from patients’ medical records (collected in a binary yes/no format for qualitative variables):

I. Sociodemographic variables: age (in years, quantitative variable), gender, birth in France, unemployed (including patients on sick leave but not retired patients), unskilled worker (i.e., job accessible without special qualifications, only job category collected), homeless, partner of life (in a relationship).

II. Main psychiatric diagnosis (1 only), according to the ICD-11: depressive disorders, schizophrenia or other primary psychotic disorders, bipolar or related disorders, anxiety or fear-related disorders, neurodevelopmental disorders, another psychiatric diagnosis (other diagnosis belonging to the ICD-11 category 6: mental, behavioral, or neurodevelopmental disorders).

III. Psychiatric comorbidity: the presence of a psychiatric comorbidity (in addition to the main diagnosis, the presence of another psychiatric disorder falling under category 6 of the ICD-11).

IV. Historical issues and lifestyle: traumatic history (exhaustively: rape and/or sexual assault and/or loss of first-degree relative before the patient’s age of 18 and/or torture and/or major physical assault and/or loss of a child by suicide and/or violent death of a first-degree relative in front of the patient and/or patient placed in foster care during childhood, and/or direct witness to a homicide), history of mental healthcare without consent (medical treatment undertaken without the consent of the patient being treated, as permitted by law), multiple psychiatric hospitalization history (> 5 full psychiatric hospitalization), alcohol abuse within the year (diagnosed by the psychiatrist as pathologic, and corresponding to the ICD-11 codes 6C40.0, 6C40.1, 6C40.20, 6C40.21, and 6C40.3), illicit drug abuse within the year (regular consumption of an illicit substance greater than 1/week), family history of mental health disease (known psychiatric disorder within the patient’s biological family), history of attempted suicide, and drug side effect reported within the year (presence of a side effect documented on the patient’s medical record).

V. Follow-up-related variables: visit to psychiatric emergency within the year (excluding the one that led to full psychiatric hospitalization of the case definition), drug treatment discontinuation within the year (discontinuation by the patient, without medical agreement, of a psychiatric background treatment regimen over a period of more than 1 week), medical follow-up discontinuation within the year, additional support within the year (follow-up by a psychiatrist at least twice a year and/or regular follow-up by a medical mobile team (> 1/trimester) and/or included in a psychoeducation care program with a total hourly volume > 15 h/year), and time since first admission to the psychiatric hospital in outpatient or inpatient setting (in years, quantitative variable).

The term “within the year” refers to the variable being present 12 months prior to hospitalization for cases or 12 months following the index consultation for controls.

These variables were chosen because they have already been identified in the literature as factors associated with psychiatric hospitalization or suggested to be potential risk factors or confounders.

We hypothesized that all variables might be potential confounders and were indiscriminately tested to include them in the regression model (see Section 2.6) and to control for potential confounders.

2.6 Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using R software version 4.2.1 (23 June 2022) (R Core Team, 2022). Collected variables in case and control groups have been compared using a bivariate analysis ( Table 1 ). For quantitative variables, the Student’s t -test was used. For qualitative variables (dichotomous variables collected in a yes/no format), a Chi-square ( χ 2 ) test was performed.

Multivariable logistic regression was used to study the relationship between the outcome and the assessed covariables (listed in Section 2.2) with adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). In the analysis and to interpret its results, control group variables were considered baseline/reference category and case variables were compared to them. Based on the significant factors identified in the univariate analysis, variables were added to the model when p < 0.10. The model was built using a forward, stepwise selection procedure. It involves iteratively adding variables to the model one at a time, based on their individual contribution to improving the model’s fit. The fitness of the models was compared with a likelihood-ratio test. The choice was made to work on a subset of patients without missing data (complete case analysis). Interactions between variables included in the model were tested. They were considered when they appeared significant ( p -value < 0.01 to avoid multiple testing problems) and had an interpretable clinical meaning. The multiple logistic regression model was adjusted for all the risk factor variables included in the full model ( Table 2 ). The data normality of residuals for this multiple logistic regression was assessed by the Shapiro–Wilk normality test.

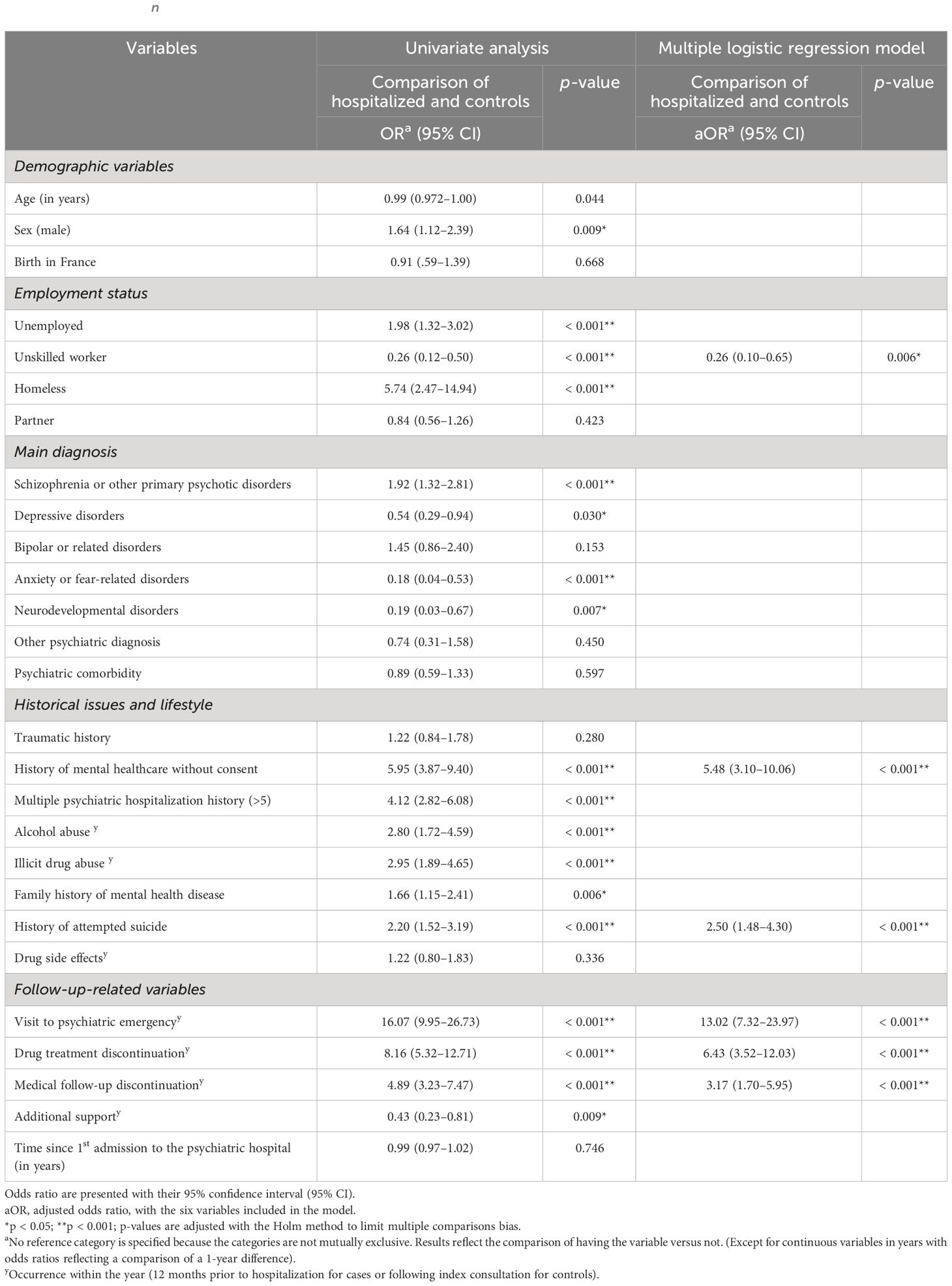

Table 2 Univariate analysis and results of a multiple logistic regression model predicting psychiatric hospital admission of outpatients (on a no missing values dataset, n = 521).

2.7 Data collection and ethical approval

Data were retrieved from the CHV’s electronic medical record system by reading through each medical record one by one. It was collected anonymously and entered directly into a secure document to ensure the confidentiality and privacy of participants. Personal identifying information such as names, addresses, and contact details were not recorded. Instead, each participant was assigned a unique identification code, which was used to perform the analyses with the studied variables. All data were stored securely and accessible only to authorized research personnel. Only the first author acquired data to guarantee reproducibility. Only the selected variables cited above were collected in the binary format “yes” or “no”, except for the two quantitative variables “age” and “time since first admission to the psychiatric hospital in outpatient or inpatient setting” collected in years (whole number).

To ensure data reliability, data were directly collected during the reading of each medical record.

Ethical approval was obtained by the Ethics Committee of the CHV with the registration number CEREVI/2023/003 on 27 February 2023. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

3.1 Participants and missing data investigation

All eligible cases have been included in the study (216 cases). Based on the number of cases and the predetermined targeted sample size, 401 controls were included out of a total eligible population of 1,044. The included controls were randomly selected from the sample list of eligible controls.

No missing data were observed for n = 521 patients out of the 617 included in the study.

When considering the mechanism underlying these missing data, it is important to note that they predominantly pertain to variables that necessitate investigating past events. Specifically, these pertain to the presence or absence of a family history of mental health diseases ( n = 55 missing data points out of 617, i.e., 8.9%), the presence or not of personal traumatic history ( n = 38 missing data points out of 617, i.e., 6.2%), and whether or not there was a history of suicide attempt ( n = 17 missing data out of 617, i.e., 2.8%). The other variables have less than 10 missing data points each. The details regarding missing data points for each of the variables within cases and controls are available in Table 1 .

3.2 Sociodemographic characteristics and descriptive analysis

Data from N = 617 patients followed up in an outpatient setting from June 2021 to February 2023 have been investigated for descriptive analysis (216 cases and 401 controls). Men were a higher proportion of cases (65.3%) than controls (56.1%). Cases were slightly younger than controls, with a mean age of 42.7 years old versus 45.1 years, respectively. Unemployment was higher among cases than controls (75.9% of unemployment for cases versus 62.8% for controls), and in parallel, more people had unskilled work in the control group (18.0% versus 5.1% in the case group ( p < 0.001)). Homelessness was much more prevalent among cases than controls, with 13.4% of homeless individuals among cases versus 2.5% for controls ( p < 0.001).

There was a difference in proportion for the main psychiatric diagnosis between groups for depression, schizophrenia or other primary psychotic disorders, anxiety or fear-related disorders, and neurodevelopmental disorders. Schizophrenia, or other primary psychotic disorders, was the main diagnosed psychiatric disease in our population (66.7% and 51.4% for cases and controls, respectively, p < 0.001).

For historical issues and lifestyle variables: case and control groups significantly differed in proportion for history of mental healthcare without consent, multiple psychiatric hospitalization history (> 5), alcohol or illicit drug abuse within the year, family history of mental health disease, and history of attempted suicide ( p < 0.001 except for family history of mental health disease with p = 0.007).

Finally, considering follow-up-related variables, strong significant proportion differences between groups for the following variables were observed ( p < 0.001): visit to a psychiatric emergency, drug treatment discontinuation, medical follow-up discontinuation, and additional support (all within the year). For the variables: visit to psychiatric emergency, drug treatment discontinuation, and medical follow-up discontinuation, the rates were all higher among cases than controls with respectively 60.2%, 58.3%, and 49.1% (cases) versus 7.7%, 12.5%, and 14.0% (controls). Conversely, additional support had a higher proportion in controls (93.8%) than in cases (84.3%) ( p < 0.001).

Table 1 describes the detailed sociodemographic, clinical, personal history, and follow-up characteristics of cases and controls ( N = 617).

3.3 Analytic statistics: multivariable modeling using multiple logistic regression

For the analytic statistics, modeling was conducted using a subset of patients without missing data (complete case analysis) with n = 521. According to our model, we found that six independent variables are significantly associated with full psychiatric hospitalization for patients being followed up in an outpatient setting. Indeed, in multivariable analysis, psychiatric hospitalization of outpatients remained strongly associated with a visit to a psychiatric emergency within a year (aOR: 13.02 [95% CI: 7.32–23.97]), a drug treatment or medical follow-up discontinuation within a year (aOR: 6.43 [95% CI: 3.52–12.03] and aOR: 3.17 [95% CI: 1.70–5.95], respectively), a history of mental healthcare without consent (aOR: 5.48 [95% CI: 3.10–10.06]), and a history of attempted suicide (aOR: 2.50 [95% CI: 1.48–4.30]). Finally, having a work (unskilled work) was conversely associated with a smaller risk of psychiatric hospitalization (aOR: 0.26 [95% CI: 0.10–0.65]). Estimates of adjusted odds ratio were calculated using logistic regression adjusted for the variables included in the model: “visit to a psychiatric emergency within a year”, “drug treatment discontinuation within a year”, “history of mental healthcare without consent”, “medical follow-up discontinuation within a year”, “history of attempted suicide”, and “unskilled job”.

Table 2 presents these identified variables with their respective odds ratios and confidence intervals.

4 Discussion

This study aimed to identify and confirm variables associated with hospitalization, including both protective and risk factors. This information aims to guide and establish appropriate vigilance and follow-up care for mental health in an outpatient setting.

According to our multivariable logistic regression model, six variables have been independently found to be significantly associated with full hospitalization in psychiatry for patients followed up in an outpatient setting: visit to a psychiatric emergency within a year, drug treatment discontinuation within a year, history of mental healthcare without consent, medical follow-up discontinuation within a year, history of attempted suicide, and unskilled job. These findings highlight the importance of considering follow-up-related, historical issues and sociodemographic determinants for successful outpatient rehabilitation and, by extension, deinstitutionalization.

Visit to a psychiatric emergency within the year was the most strongly associated variable with hospitalization and had an aOR of 13.02 (95% CI: 7.32–23.97) in our model. This result is in line with literature that identified emergency visits associated with hospitalization, but to a lesser extent and not in an exclusive outpatient setting like in our study ( 21 ) ( 10 ). Drug treatment discontinuation within the year was associated with an aOR of 6.43 (95% CI: 3.52–12.03). A systematic literature review by Donisi et al. ( 11 ) identified medication compliance as a factor associated with readmissions of psychiatric patients, but Antonio Ciudad et al. ( 20 ) found conflicting results for schizophrenic outpatients. A recent study on early psychiatric rehospitalization also found mental health prescription adherence as a predictor of rehospitalization with a random forest analysis ( 10 ). Medication compliance is known to be an important and challenging factor in the care of psychiatric patients ( 22 ). Our study identified and confirmed the importance of medication compliance in an outpatient setting. History of mental healthcare without consent was also associated with hospitalization (aOR: 5.48, 95% CI: 3.10–10.06). We can assume that patients with a history of care without consent are the ones with bad insight into their illness and are therefore more complex patients, requiring more frequent hospitalization. This risk factor has already been identified, particularly in schizophrenic patients ( 23 ). In another study, conducted without distinction of psychiatric pathology and still in an inpatient setting, no statistical association was found ( 18 ). Medical follow-up discontinuation in psychiatry has also already been studied in the literature. Anne Nelson et al. examined whether patients discharged from inpatient psychiatric care (and not originated from outpatient care like in our study) would have lower rehospitalization rates if they kept an outpatient follow-up appointment after discharge ( 17 ). The authors showed a greater rate of rehospitalization for patients who did not keep an appointment after discharge. The same conclusions have been drawn on a general psychiatric inpatient population ( 10 ) and on a study focused on schizophrenia ( 14 ). In our study, where patients come from an outpatient setting, we also found that medical follow-up discontinuation is a risk factor for hospitalization (aOR: 3.17, 95% CI: 1.70–5.95). A history of attempted suicide also appeared to be a risk factor for psychiatric hospitalization for patients followed up in an outpatient mental health setting, with a 2.50 aOR (95% CI: 1.48–4.30). However, the literature shows conflicting results. Some studies also confirm this risk factor, which has previously been identified in studies conducted in inpatient settings ( 18 , 24 ); in other studies, this risk factor was unclear, with nonsignificant results ( 11 , 21 , 25 ). The ability to have a job, which has been collected in our study with the variable “unskilled worker”, has been identified as a protective factor in the multivariable logistic regression model ( p -value: 0.006) adjusted for potential confounders, as illustrated in Table 2 : aOR of 0.26 (95% CI: 0.10–0.65). We explain this protective effect by assuming that controls, supposed to be clinically less severe than cases, with fewer symptoms, are more likely to get and keep a work. Having a job is indeed linked with cognitive remediation and the recovery process ( 26 ). “Unskilled worker” has been the only job category collected because other job categories were almost nonexistent in our population.

The community-based outpatient setting of the present study is particularly interesting regarding its population characteristics. Indeed, it offers multi-professional monitoring, which is valuable for patients with severe illnesses. With 75.9% of cases and 62.8% of controls unemployed in our study, this strongly suggests that mental disability significantly impacts psychosocial determinants, highlighting its importance. As with other chronic illnesses, psychological disability is a barrier to employment, and the severity of the condition is related to the ability to work ( 26 ). This might also explain the protective effect found in the association of the variable “unskilled worker”. Patients followed up regularly in this setting are also considered “severe” for other reasons. They often cannot follow a liberal mental health specialist due to poor socioeconomic conditions and may have a too severe psychiatric disorder requiring hospital practitioners (due to complex pharmacotherapeutics or illness) to reach a stable medical state. From a clinical point of view, most patients having a main diagnosis of schizophrenia or other primary psychotic disorders (66.7% among cases and 51.4% among controls) is another argument for the population severity, with patients who cannot be adequately followed up by general practitioners and/or private psychiatrists. Interestingly, this does not represent the psychiatric diseases distribution of general population and is even the opposite. Indeed, in France, anxiety disorders have the highest prevalence, followed by depression, bipolar disorders, and finally, psychotic disorders ( 27 ). Regarding historical issues and lifestyle, the prevalence of traumatic history was notably high in both groups, with around 60% prevalence. Mental health conditions are well-known to have multifactorial origins ( 28 ). Nevertheless, it is noteworthy to observe the prevalence of traumatic exposure within our study population. The high proportions of patients with mental healthcare without consent history and multiple psychiatric hospitalization histories (> 5) also underline the specificities of our outpatient population, which have a certain severity. Multidisciplinary community-based care has the potential to address the specific needs of the population within the framework of deinstitutionalization when considering the identified determinants.

The case–control design and the multivariable logistic regression utilized have, however, their limitations. Firstly, the population selection has been made through “hospital recruitment” (outpatient service attached to the CHV public psychiatric hospital). It can therefore introduce a selection bias regarding the admission probability of participants to that public outpatient service (e.g., patients with poorest socioeconomic conditions). Nonetheless, as the probability of admission to that service relies on the geographical sectorization (population originating from a defined geographic urban area: third, sixth, and eighth districts of Lyon) and has few equivalents in the private sector, we consider this bias to be existent but limited. To limit classification bias, classification was made on electronical medical records identically for cases and controls. Sectorization also prevents the risk of missing a hospitalization in another facility by ensuring the patient is ultimately hospitalized in his or her local hospital. Confusion bias has been considered via modeling with multivariable logistic regression. We assessed interactions in our model with one being significant (variable history of mental healthcare without consent with variable history of attempted suicide, adjusted p -value of 0.004). We, however, decided not to include this interaction in the model because (i) the clinical relevance of this interaction was not key in our exploratory investigation, and we do not seek a predictive model; (ii) considering that this interaction barely improves our overall model significance (residual deviance of 361 when considered versus 370, p -value: 0.003). Lastly, a limitation of our model is the absence of residuals normality for this multiple logistic regression. Indeed, residuals do not seem independent of the predicted values. Some explanatory variables would thus be lacking and not exhaustively listed in this study, such as variables on education level or on patient’s attitude and perception.

The highlights of this study are, however, its overall consistency with literature data on previously identified risk factors associated with hospitalization and the confirmation of these factors in an exclusive outpatient setting. The recruitment method used in this study with the sectorization principle of the service is also a robust point because it allowed to limit selection bias and consider all the patients followed up in this special outpatient setting.

5 Conclusion

Our study identified several independent risk and protective factors for hospitalization among patients with a mental health condition who are being treated in an outpatient setting. These factors include variables related to follow-up, such as a recent visit to a psychiatric emergency and recent discontinuation of drug treatment or medical follow-up (within the year), as well as historical issues or lifestyle-related factors.

To our knowledge, this is the first time that these factors are assessed statistically together in a specific outpatient setting, with patients not originating exclusively from a hospital. That is of great interest in the deinstitutionalization era. Public health policies at local and to a bigger extent, at the national scale, should consider these new data to target and tailor appropriate follow-up of care in outpatient settings. Tools to distinguish patients with the identified risk factors and prevent them from being hospitalized should also be created and adapted.

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: Medical information that cannot be shared according to the ethical approval obtained by the Ethics Committee of the CHV with the registration number CEREVI/2023/003 on 02/27/2023. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to [email protected].

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of the CHV with the registration number CEREVI/2023/003 on 02/27/2023. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because the data were obtained in routine care practice with patient information and possible retraction. The study was carried out in accordance with current legislations.

Author contributions

ML: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. RM: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. CD: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Methodology. LZ: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Project administration. JP: Writing – review & editing, Software, Data curation. NF: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note