- Sign In / Manage Profile

- Learn About Membership

- Join AMWA Now

- Access Member Benefits

- Member Directory

- Recognition & Awards

- AMWA Code of Ethics

- AMWA Education

- Online Learning

- Live Webinars

- Essential Skills

- ES Certificate

- Certificate in Medical Editing

- Onsite Training

- Events Calendar

- AMWA Career

- Search the Directory

- Create a Listing

- Compensation and Salary Information

- Advance Your Professional Career

- Expert Tips for Freelance Medical Writing

- Guide to Becoming a Medical Writer

- Guide to Regulatory Writing

- Medical Editing Guide

- Value of Medical Writing

- Employer Resources

- About Medical Communication

- View the Current MWCs

- About the MWC Commission

- AMWA Resources

- Current Issue

- Read Recent Issues

- Past Issue Archive

- Instructions for Contributors

- Index (1985-2023)

- Medical Communication News

- Member Resource Library

- Mini Tutorials

- Position Statements and Guidelines

- Regulatory Writer Training eBook

- Online Store

- AMWA Event Calendar

- Registration

- Onsite Experience

- Sponsors and Exhibitors

- AMWA Online Learning

Ultimate Guide to Becoming a Medical Writer

Medical writing is an esteemed profession. Every day, medical writers are detailing, documenting, and sharing news and research that is improving health outcomes and saving lives. Their roles and opportunities are always evolving, whether they’re crafting peer-reviewed articles reporting on clinical trials, marketing cutting-edge devices, educating health care professionals or even the general public about new treatments, or writing grant proposals to fund innovative research.

This guide provides information and resources on what medical writers do, the companies they work for, and what you need to know to embark on this growing, rewarding—and lucrative—career.

What Is Medical Writing?

Medical writing involves the development and production of print or digital documents that deal specifically with medicine or health care. The profession of medical writing calls for knowledge in both writing and science, combining a writer’s creative talent with the rigor and detail of research and the scientific process.

With the constant advancement and innovation in medicine and health care, the need to communicate about research findings, products, devices, and services is growing. Medical writers are increasingly in demand to convey new information to health care professionals as well as the general public.

Depending on their position and the scope of their duties, medical writers are involved in communicating scientific and clinical data to many audiences, from doctors and nurses to insurance adjusters and patients. They work in a variety of formats, including traditional print publications to electronic publications, multimedia presentations, videos, podcasts, website content, and social media sites.

Medical writers often work with doctors, scientists, and other subject matter experts (SMEs) to create documents that describe research results, product use, and other medical information. They also ensure that documents comply with regulatory, publication, or other guidelines in terms of content, format, and structure.

Medical writers are also key players in developing applications for mobile devices that are used in multiple ways, such as

- Disease management

- Continuing education and training

- Medical reference and information-gathering

- Practice management and monitoring

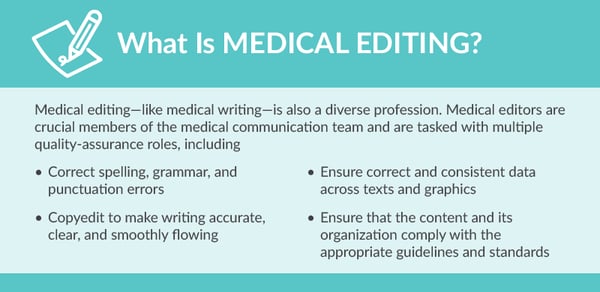

Medical communicators may be writers, editors , health care journalists, supervisors, project managers, media relations specialists, educators, and more. At their core, they are exceptionally skilled at gathering, organizing, interpreting, evaluating, and presenting often complex information to health care professionals, a public audience, or industry professionals such as hospital purchasers, manufacturers and users of medical devices, pharmaceutical sales representatives, members of the insurance industry, and public policy officials. For each of these audiences, the language, documents, and deliverables are distinct. For beginning to mid-level medical communicators who want to enhance and fine-tune their medical editing skills, AMWA provides a Certificate in Medical Editing .

What Are Examples of Medical Communication Jobs?

Medical communication positions in writing and editing vary greatly across industries, companies, organizations, and other entities.

In addition to the title of medical writer, medical communicators may be known as scientific writers, technical writers, regulatory writers , promotional writers, health care marketers, health care journalists, or communication specialists. Both medical writers and medical editors may work for pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, medical communication agencies, medical education companies, health care professionals associations, academic institutions, medical and health care book publishers, trade publications, and more.

What Do Medical Writers Write?

The expertise and contributions of medical writers and editors can be found throughout the medical community. Examples of their work include

- Abstracts for medical journals and medical conferences

- Advertisements for pharmaceuticals, devices, and other products

- Advisory board summaries

- Continuing medical education materials

- Decision aids for patients

- Grant proposals

- Health care policy documents

- Health education materials

- Magazine and newspaper articles

- Medical and health care books

- Medical and scientific journal articles

- Marketing materials

- Poster presentations for medical conferences

- Regulatory documents, including FDA submissions

- Sales training

- Slide presentations for medical conferences

- White papers

Who Hires Medical Writers?

Right now, there is tremendous growth in the medical industry. Pharmaceutical companies are developing drugs more quickly, and new medical devices and diagnostic tools are being released every day. With this comes the increased need to meet regulatory and insurance requirements and to relay medical and consumer information. All of this results in greater opportunities for medical writers and communicators.

Medical writers can find positions with a variety of employers, reaching a multitude of audiences with different communication needs and styles. These may include

- Associations and professional health care societies

- Authors or investigators

- Biotechnology companies

- Clinical or contract research organizations (CROs)

- Communications, marketing, or advertising agencies

- Government agencies

- Health care organizations or providers

- Medical book publishers

- Medical device companies

- Medical education companies

- Medical schools or universities

- News outlets for health/medical news

- Peer-reviewed medical journals

- Pharmaceutical companies

- Trade journals for health care professionals

AMWA members can access a current list of available openings on AMWA Jobs Online . (Not a member? Join here. )

How Much Do Medical Writers Make?

Medical writer salaries vary from city to city and region to region. Compensation also depends on the writer’s experience, the type of employer, and the type of work.

Sites such as Salary.com , PayScale.com , and Glassdoor.com indicate that a salary range for a junior-level or beginning medical writer is $52,000 to $80,000 annually and a salary range for a junior-level or beginning medical editor as $57,000 to $75,000 annually.

The AMWA Medical Communication Compensation Report provides an in-depth analysis of medical communication salary data by experience level, degree, industry categories, and much more.

Join our professional community of skilled medical communicators.

What Does It Take to Be a Medical Writer?

While medical writers come from all educational and professional backgrounds, they do share some traits. Medical writers have an interest and flair for both science and writing. They also have a clear understanding of medical concepts and ideas and are able to present data and its interpretation in a way the target audience will understand.

Although it’s not required, many medical communicators hold an advanced degree. Some have a medical or science degree (eg, PhD, PharmD, MD) or experience in academic settings or as bench scientists, pharmacists, physicians, or other health care professionals. Others have an MFA or a PhD in communications or English.

Certificates and certifications are additional credentials that demonstrate your knowledge and proficiency in the medical communication field. Many are described in this guide.

How Do I Become a Medical Writer?

Medical communication can be a flexible, rewarding, and well-paying career in a growing field of both full-time and freelance opportunities. To get started, follow these steps.

1. Determine a focus

Based on the wide range of companies and organizations that employ medical communicators, the field is generally divided into different writing settings and specializations, each requiring specific technical writing skills or knowledge of medical terminology and practices. In this step, it’s important to focus on an area you’re most interested in and that best matches your skill set.

- Continuing education for healthcare professionals

- Health communication

- Marketing/Advertising/PR

- Patient education

- Publications for professional audiences (non-peer reviewed)

- Regulatory writing

- Sales training (biotech or pharma industry)

- Scientific publications (peer-reviewed journals)

2. Assess your knowledge and skills

Medical communicators come to the field from a variety of different disciplines. Those with a medical or science background commonly need refreshers in writing and editing mechanics, whereas medical terminology and statistics are typically more difficult for those with a writing or communications background. No matter what your training has been, you should take an inventory of your essential skills .

Basic Grammar and Usage

- Parts of speech and grammatical principles form the foundation of writing in every discipline. Can you identify a dangling modifier or notice the lack of a pronoun referent?

Sentence Structure

- Even if you know grammar, you may need a refresher on achieving emphasis and organizing your sentences for clarity. Do you know the difference between an independent and a dependent clause? Do you understand parallel structure?

Punctuation

- A single misplaced comma can create a very different meaning, which can have serious implications in medical writing. Are all your commas in the right places? What about your semicolons?

Medical Terminology

- It’s not enough to know medical terms. You gain more insight into medical vocabulary by learning about the prefixes, combining forms, and suffixes that make up all your favorite medical words. Do you know the rules for eponyms? Do you know the difference between an acronym and an initialism?

Professional Ethics

- Every profession has a code of ethics, and medical communication is no different. Make sure you know the steps to ethical decision-making and the ethical principles to uphold.

- If you’re working with medical research, it’s essential to have a basic understanding of statistics. Can you describe the difference between mean, median, and mode? Can you define a hazard ratio?

Tables and Graphs

- Tables and graphs are essential tools for communicating complex information. Do you know what kind of graph to use for continuous data? Are your table column headings doing their job?

If you need to fill gaps in your knowledge, AMWA offers a variety of educational activities , including the AMWA Essential Skills Certificate Program , which addresses all of these topics.

3. Explore resources

As you explore the medical writing profession, the next step is to become aware of the resources available to you. AMWA offers many opportunities to support new medical communicators and a wealth of professional development resources to help throughout an evolving career. The following are some examples.

- AMWA Online Learning activity: A Career in Medical Communication: Steps to Success

- AMWA Career Services : Jobs Online , Freelance Directory

- Live webinars

- AMWA Essential Skills Certificate Program

- Comprehensive Guide to Medical Editing

- Medical Editing Checklist

- How to Identify Predatory Publishers eBook

Other resources include a number of recommended books on medical writing , listed in the "Medical Writer Resources" section below.

Although there are plenty of opportunities in medical communication, it is important to recognize that it can be a difficult field to break into. Networking is a crucial part of gaining success as a medical writer.

Throughout your career, but especially at the start, it’s important to connect with other medical communicators in your local area as well as across the country .

Networking is an excellent way to connect with other medical communicators. Not only does it provide informal learning opportunities, but some experts say that 70% to 80% of people found their current position through networking. Others say it’s closer to 85%. Whether you are using LinkedIn , Facebook , Twitter , community boards, or conference attendance , it is important to seek out ways to stay connected.

Take the leap!

New and experienced medical writers are finding ways to advance in a solid career and contribute to positive health outcomes through the power of communication. With a greater understanding of the role of the medical communicator and the available opportunities, people with a passion for writing and science can excel in this interesting and ever-changing field.

Medical Writer Resources

Books about medical writing.

- The Accidental Medical Writer . Brian G. Bass and Cynthia L. Kryder. Booklocker.com, Inc, 2008.

- Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers . 2nd ed. Mimi Zeiger. McGraw-Hill, 2000.

- Health Literacy from A to Z: Practical Ways to Communicate Your Health Message . Helen Osborne. Jones and Bartlett Publishers, 2005.

- How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper, 8th ed . Barbara Gastel and Robert A. Day. Greenwood, 2016.

- Targeted Regulatory Writing Techniques: Clinical Documents for Drugs and Biologics . Linda Fossati Wood and MaryAnn Foote, eds. Birkhauser, 2009.

Style Guides

- AMA Manual of Style

- Associated Press Stylebook

- Chicago Manual of Style

- American Psychological Association Style

- Scientific Style and Format: The CSE Manual for Authors, Editors, and Publishers

Publication Ethics

- Code of Conduct and Best Practice Guidelines for Journal Editors (Committee on Publication Ethics)

- White Paper on Publication Ethics (Council of Science Editors)

- Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals (International Committee of Medical Journal Editors)

- Good Publication Practice Guidelines - GPP3 (International Society for Medical Publication Professionals)

Professional Associations & Societies

- American Medical Writers Association

- Association of Health Care Journalists

- Board of Editors in the Life Sciences

- Council of Science Editors

- Drug Information Association

- Editorial Freelancers Association

- International Society for Medical Publication Professionals

- National Association of Science Writers

- Regulatory Affairs Professionals Society

- Society for Health Communication

- Society for Technical Communication

Medical Communication Programs – Universities, Colleges, Associations

This list is not comprehensive and was last updated on 11/23/2022.

Graduate Programs in Medical/Health Communication/Writing/Journalism

- Master of Science in Health Communication (Online)

- Master of Science: Science & Medical Journalism

- Carnegie Mellon University - Master of Arts: Professional Writing

- Johns Hopkins University - Master of Arts: Science-Medical Writing

- New York University - Master of Arts / Master of Science: Health and Environmental Reporting

- Texas A&M University - Master of Science: Science and Technology Journalism

- Towson University - Master of Science: Professional Writing

- University of Houston-Downtown - Master of Science: Technical Communication

- University of Illinois - Master of Science: Health Communication

- University of Minnesota - Professional Master of Arts: Health Communication

- University of North Carolina - Master of Arts: Medical Science & Journalism

Undergraduate Programs in Medical/Health Communication/Writing/Journalism

- Juniata College - Degree in Health Communication

- Missouri State University - Bachelor of Arts / Bachelor of Science: Science/Professional Writing

- University of Minnesota - Bachelor of Arts: Technical Writing and Communication

Tracks or Minors in Medical Communication

- Ferris State University - Bachelor of Science: Journalism and Technical Communication

- University of Tennessee at Knoxville - Science Communication Program

Degree Programs in Regulatory Affairs

- George Washington University - Dual Degree: BSHS/MSHS in Clinical Operations & Healthcare Management

- University of Washington School of Pharmacy - Master of Science in Biomedical Regulatory Affair s

University Certificate Programs

- Harvard Medical School - Effective Writing for Health Care

- UC San Diego Extension - Medical Writing Certificate

- University of Chicago Graham School of General Studies - Medical Writing and Editing Certificate

AMWA acknowledges the contributions of Lori Alexander, MPTW, ELS, MWC, Lori De Milto, MJ, and Cyndy Kryder, MS, MWC in the development of this AMWA resource.

WANT A PORTABLE VERSION OF THIS ARTICLE? DOWNLOAD IT HERE.

American Medical Writers Association 9841 Washingtonian Blvd, Suite 500-26 Gaithersburg, MD 20878

phone: 240. 238. 0940 fax: 301. 294. 9006 [email protected]

About Us Contact AMWA Staff © 2023 AMWA / Policies

QUICK LINKS

- AMWA Journal

- Certification

- Engage Online Community

- Medical Writing & Communication Conference

CONNECT WITH US

- Support AMWA

- Advertise with AMWA

Membership Management Software Powered by YourMembership :: Legal

UC Irvine GPS-STEM

Graduate Professional Success for PhD students and Postdocs in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics

Basics of Medical Writing for PhD Students and Postdocs

Mini-course (5 learning modules) offered by

Graduate Professional Success in STEM (GPS-STEM) at UC Irvine

Date/Time: August 14 (Fridays) ; 12:00PM (PST)

Duration: 5 Weeks [ August 14, 2020 – Sept 11, 2020]

Currently, a significant number of biomedical PhDs are employed in scientific industry and the demand for highly skilled PhD level scientists keeps growing. Biomedical science PhDs can transition into ~20 different non-academic careers in the private sector, government and nonprofits. Out of the wide variety of available industry jobs, medical writing jobs are becoming increasingly popular amongst biomedical PhDs.

Historically, the medical writing field has employed a large number of professional degree holders e.g PharmD and MDs; however, lately this trend has shifted towards hiring basic science PhDs. Healthcare industries value biomedical science PhDs due to their vast subject matter expertise, ability to understand pathophysiology of different disease conditions, drug mechanisms, high level of analytical skills, and exceptional writing traits. However, there is inadequate knowledge amongst trainees (PhD students & Postdocs) on medical writing as a plausible future career as well as mechanisms of transitioning into these roles.

In order to fill the gap in knowledge and experience related to medical writing careers, GPS-STEM at UC Irvine is offering a mini-course, designed to help trainees learn the landscape of the medical writing field, roles and responsibilities of a medical writer, and the variety of transferable skills required to transition into these roles.

Mission: Help trainees understand ins-and-outs of the medical writing field & teach ways to transition successfully

- Help trainees understand similarities and differences between grant writing, manuscript writing, & medical writing

- Gain deeper understanding of medical writing field

- Learn about different kinds of medical writing e.g regulatory writing, health communications, publications, diagnostics and other kinds of educational writing

- Learn transferable skills required to transition into these roles plus skills required on the job to be successful

- Practice writing tests required during the hiring process

- Learn about steps and techniques to successfully transition into writing roles

Course Coordinators:

Acknowledgements: GPS-STEM program would like to sincerely thank William Kim for helping with the curriculum design, Huixuan Liang for bringing regulatory affairs writing expertise and all the UCI alumn i for helping take this course off the ground.

Special thanks to Joanne Ly , PhD student in Biomedical Engineering & Multimedia Director of GPS-STEM program, for beautiful graphics.

Course Curriculum & Schedule

Module 1 [ Aug 14, 2020 ] : Introduction & overview of the field of medical writing. Understand the landscape of medical writing field, kinds of medical writing, skills required to transition. Basics of Medical Writing

- Publications

- Regulatory

- Medical Education

- Health communication

- Laboratory diagnostics

- Promotional

- FDA – Regulatory writing

Required skill sets (Transferrable Skills) & qualifications for the role

Speakers/Panelists:

- William Kim, PhD. Manager, Scientific Communications at Edwards Lifescience (Prev. Sr. Medical Writer, Allergan)

- Julie Dela Cruz-Mulder, PhD . Medical Science Liaison, Eli Lilly. Previously, Publications Manager, Allergan (now Abbvie)

- Huixuan Liang, PhD . Sr. Medical Writer at Medtronic

- Terra White, PhD . Medical Writer at Quest Diagnostics

Module 2 [ Aug 21, 2020 ]: Where do medical writers work/Career development/progression Learn about many places where medical writers are employed at including avenues of career development in each. Our speakers will share medical writer roles in Biotech, medical device and pharmaceutical companies, CROs, communication agencies, education sector, freelance and medical writing agencies.

Major discussion topics –

- Is there scope of lateral transition or climbing ladder

- Freelance medical writing

- Medical writing agencies

- Average time one spends in a writing job

- What other kind of roles/jobs medical writers transition into e.g is it easy to transition from medical writing to regulatory writing & vice-versa

Required skill sets

- Ana Vicente-sanchez, PhD . Scientific Associate/Medical Writer, PrecisionValue ((Medical Writing Agency)

Module 3 [ Aug 28, 2020 ] : Examples of the types of work that medical writers perform on the job (with examples) . During this session, speakers will provide examples of the kinds of writing medical writers perform. Discuss key collaborators e.g Pub Managers, R&D, Clinical teams, MDs, PhDs. and understanding the kinds of working relationships

- Journal articles

- Abstract writing

- Conference posters/presentations

- Slides/internal training materials

- Data analysis

- Project timeline

- Stakeholder engagement

- Healthcare agencies

- Documentation

- Authorship guidelines – Differences b/w academia vs Industry

Required Skill Sets (Transferrable Skills)

- Nayna Sanathara, PhD . Principal Medical Writer at Abbvie

- Sarah Joy Cross, PhD . Sr. Medical Writer at Abbvie

- Emma Flores-Kim, PhD. Scientific Affairs Manager, NeoTract

Module 4 [ Sept 4, 2020 ] : Tests on writing and editing with examples of kinds of writing exams

- In this module we will offer publicly available tests or examples for practice to get familiar with the application process

- Write abstract and create 5 min presentation slide based on several pages of clinical data

- Create a complex data figure on excel similar to given example and write up a paragraph describing the results in the figure

- Brush up on basic stats, eg, confidence intervals, standard deviation, p value

- Writing assignments * will be due at the end of the course for receiving certificate of course completion.

- What skill sets employers look for in medical writers (transferable skills from PhD/Postdoc to be highlighted in the cover letters)

Module 5 [ Sept 11, 2020 ] : How to transition into medical writing roles – Panel discussion & e-Networking.

- Examples of Resume, cover letter tailoring tricks for these jobs

- Effective use of LinkedIn for job search in the field

- Networking events & Alumni mentoring programs

Medical writers in attendance –

- Kristin Hirahatake, PhD . Sr. Medical Writer at Abbvie

*Writing Assignments Due [Sept 14, 2020]: Submit assignments, receive feedback from speakers/panelists – Certificate of course completion

Resources for Medical Writing Careers:

- How to prepare for a medical writing career as a graduate student or postdoc

- The medical writing career path for PhDs

- Is a career in medical writing right for you?

- Genetics PhD to medical writer and entrepreneur

- So you want to be a medical writer – Interview

- What types of medical writing are there? AMWA

- A career in medical communication: Steps to success

- An ultimate guide to becoming a medical writer

- 5 Steps to a successful job search in medical writing

UCI Partners

- Antrepreneur Center

- Applied Innovation

- Career Center

- Graduate Resource Center

- Outreach & Minority Science Programs

- The Graduate Division

- UCI Division of Continuing Education

- UCI Office of Postdoctoral Scholars

- UCI Postdoctoral Association

External Partners

- Fish & Tsang LLP

- LDOS Media Lab

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Volume 25, Issue 2 - Medical Communication

A phd and medical writing: a good match, author: benjamin gallarda.

The transition out of academia can involve a good deal of change. For PhDs who enjoy writing, a career in medical communications is a viable option. The field of medical writing is broad, encompassing everything from regulatory affairs, to writing and editing manuscripts, to medical education and promotion. Despite numerous novel experiences offered by medical writing, several skills typically acquired during the course of a PhD programme align nicely with the new requirements and responsibilities. From the perspective of a medical communications agency, PhDs form an important bridge between the need for deep and thorough biomedical knowledge and the daily responsibilities of writing, editing, educating and promoting. Should one choose to apply these skills to medical writing, the result can be an interesting and enjoyable work for the PhD, and a benefit to the employing agency.

- Cyranoski D, Gilbert N, Ledford H, Nayar A, Yahia M. Education: The PhD factory. Nature. 2011; 472:276-9.

- Sauermann H, Roach M. Science PhD career preferences: Levels, changes, and advisor encouragement. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36307.

- Sharma S. How to become a competent medical writer? Perspect Clin Res. 2010;1(1):33-7.

- How long is the average dissertation? 2013 [cited 2016 Feb 28] Available from: https://beckmw.wordpress.com/2013/ 04/15/how-long-is-the-averagedissertation/

Editoral Board

Editor-in-Chief

Raquel Billiones

Evguenia Alechine

Jonathan Pitt

Managing Editor

Victoria White

Associate Editors

Anuradha Alahari

Jennifer Bell

Nicole Bezuidenhout

Claire Chang

Barbara Grossman

Sarah Milner

Sampoorna Rappaz

Amy Whereat

Section Editors

Daniela Kamir

AI/Automation

Biotechnology

Nicole Bezuidenhout

Digital Communication

Somsuvro Basu

EMWA News

Ana Sofia Correia

Gained in Translation

Ivana Turek

Getting Your Foot in the Door

Wendy Kingdom / Amy Whereat

Good Writing Practice

Alison McIntosh

In the Bookstores

Maria Kołtowska-Häggström

Lingua Franca and Beyond

Publications

Lisa Chamberlain-James

Medical Communications/Writing for Patients

Payal Bhatia

Medical Devices

My First Medical Writing

News from the EMA

Adriana Rocha

Freelancing

Tiziana von Bruchhausen

Pharmacovigilance

Clare Chang / Zuo Yen Lee

Regulatory Matters

Sam Hamilton

Regulatory Public Disclosure

Claire Gudex

Teaching Medical Writing

Louisa Ludwig-Begall / Sarah Kabani

The Crofter: Sustainable Communications

Louisa Marcombes

Veterinary Writing

Editors Emeritus

Elise Langdon-Neuner

Phil Leventhal

Layout Designer

Fellowship and Scientific Writing Resources

Weill Cornell Graduate School (WCGS) strongly encourages our students to apply for external funding. While we guarantee funding for all students during their training, the process of writing a fellowship allows you to hone your scientific writing skills and develop your research project. Receiving a fellowship can also make your future job applications - in and outside academia - more competitive. The Office of Fellowships and Scientific Writing (OFSW) supports students through the grant writing and submission process.

Fellowship Opportunities

Please check out our highlighted Fellowship Opportunities and the WCM Funding Database .

Services provided by OFSW

Fellowship writing workshops.

The OFSW has sourced materials from the NIH, professional grant writing consultants, and the literature to create multiple fellowship writing workshops that combine didactic lectures with peer review of participants’ proposals. Notification of the workshop dates are sent out via the Graduate Student email list.

- NSF GRFP Workshop: The NSF GRFP funds early-stage graduate students, first or second year students, who have not completed a stand alone Master’s degree. This mutli-week workshop includes detailed instruction regarding rules and regulations, review criteria, and coordination of peer review. Dates: Workshop September-October. Submission deadline typically mid-October.

- NIH F31 Workshops: The F31 National Research Service Award (NRSA) predoctoral training fellowship is given to promising applicants with the potential to become productive, independent investigators. We offer the F31 workshop series three times a year to coincide with NIH fellowship cycle deadlines. The goal of these multi-week workshops is to provide students with information regarding application components, outline the NIH peer review system for evaluating fellowships and grants, and coordination of peer review. Dates: Workshops October-November, February-April, and June-July. Submission deadline April 8, August 8, and December 8. When deadline dates occur on a weekend or federal holiday, the submission deadline is the next business day.

One-on-One Consultation and Proposal Editing Services

We encourage students to reach out to our office via email to set up appointments for individualized advice on all topics related to fellowships. We can assist at all stages of proposal development; including helping you choose a fellowship that is aligned with your research and career goals, brainstorming research topics/hypothesis development, and structuring an effective proposal. With advanced notice, we also offer editing of finalized drafts.

Submission of Graduate Student Fellowship and Grant Applications

Some fellowships are submitted to the sponsor from the university using a "system-2-system" platform; other fellowships are submitted to the sponsor by the applicant. Regardless of the method of submission, all fellowships with a budget must be reviewed by the university prior to submission.

The Office of Fellowships and Scientific Writing is responsible for routing all graduate student fellowship and grant applications to the Office of Sponsored Research Administration (OSRA) at Weill Cornell Medicine for review. Fellowship applications are routed to OSRA through Weill Research Gateway (WRG) . OSRA has standard due dates associated with application routing in WRG.

NIH submissions

NIH submissions are due for pre-review at 3pm EST 7 business days prior to the sponsor deadline . Pre-review requires that all “non-science” documents must be finalized. All attachments except the Specific Aims page, Research Strategy, and associated Bibliography are due in their final form at pre-review.

NIH submissions are due for final review at 3pm EST 2 business days prior to the sponsor deadline . All grant documents must be finalized at this time.

All other submissions

All other submissions are due for final review at 3pm EST 2 business days prior to the sponsor deadline . All grant documents must be finalized at this time.

Fellowship Progress Reports and Termination Notices

The Office of Fellowships and Scientific Writing (OFSW) works together with the Graduate School's post-award and financial team and Office of Sponsored Research Administration (OSRA) to help students with federal fellowships submit required progress reports. These include:

- NIH Research Performance Progress Reports (RPPR) for F31 and F99/K00 fellowships. RPPRs are due to the NIH 2 months before the start of the next project period. RPPRs are submitted to the NIH via eRA Commons , and must be routed to OSRA in eRA Commons for approval 7 business days prior to the NIH deadline for review.

- NSF GRFP Annual Activities Reports, described in the administrative guide . Annual Activities Reports are submitted via the NSF Fastlane portal .

Additional Resources

Meet our fellows.

2024 NSF GRSP Awardees and Honorable Mentions

Leandro Pimentel Marcelino Program: Tri-I PhD in Chemical Biology Mentor: Dr. Tarun Kapoor at RU Award Result: Awarded Rose Sciortino Program: Neuroscience Mentor: Dr. Miklos Toth at WCM Award Result: Honorable Mention Jian Zheng Program BCMB Allied Program Mentor: Xiaolan Zhao at MSKCC Award Result: Honorable Mention

Fellowship Award Policies

While WCGS guarantees funding for all students, we strongly encourage our students to apply for external funding. As an incentive, WCGS issues an additional “Fellowship Award” to each student who receives a fellowship, scholarship, or grant from an external funding agency’s competitive award program. To learn more, click here .

Travel Award Policies

The Weill Cornell Graduate School of Medical Sciences believes that presenting research as a first-author is an essential part of the graduate training experience. To support our graduate students, WCGS provides $1,200 per year to PhD students in the BCMB, IMP, Neuroscience, Pharmacology, and PBSB programs to travel to present their first author work , e.g., a poster or talk, at a conference or meeting. To learn more, click here .

Diversity Supplements Information

Diversity Supplements are additional financial support provided to Principle Investigators (PIs) who have already been awarded a research grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The goal of these supplements is to enhance the diversity of the research workforce by financially supporting the stipends/salaries of students, postdoctorates, and eligible investigators from diverse backgrounds, including those from groups that have been shown to be underrepresented in health-related research. To learn more, click here .

Office of Fellowships and Scientific Writing Contact Information

Contact us with questions regarding fellowship development or scientific writing.

Weill Cornell Medicine Graduate School of Medical Sciences 1300 York Ave. Box 65 New York, NY 10065 Phone: (212) 746-6565 Fax: (212) 746-8906

Non-Credit Certificate Program in Medical Writing and Editing

Master the fundamentals and best practices of medical writing, editing, and communication.

Upcoming Events

How to Land Your First Job in Editing

Apr 29, 2024 • Online

Career Pivots Online Panel

May 8, 2024 • Online

At a Glance

The University of Chicago’s non-credit certificate in Medical Writing and Editing uses the AMA Manual of Style as the foundation for mastering the fundamentals and best practices of medical writing, editing, and communication.

Developed for professionals with backgrounds in science or writing, the online medical writing certificate program with synchronous course sessions has a comprehensive curriculum focused on creating medical communicators with strong writing, editing, data reporting, and analytic skills. Student have the opportunity to boost their skills quickly in nine months to one year, part-time.

Designed For

Designed for both professionals with a background in science who want to acquire writing skills, and those with a background in writing or an English degree who want to understand medical terminology.

Learn from Industry Experts

Our program instructors have worked with and for a wide range of leading organizations, including the American Medical Association, WebMD, the Mayo Clinic, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, and the Journal of Graduate Medical Education.

Want to Learn More?

View our comprehensive curriculum, taught by seasoned medical writers and editors.

Grow Your Network

Current students and alumni have access to networking events and webinars hosted by our Student Advisory Board and our Professional Development team, who also fund an alumni scholarship program.

Join a Thriving Field in Medical Writing

Driven by the expansion of scientific and technical products, the Bureau of Labor Statistics projects a faster growth rate in the employment of technical writers than that in other fields.

Potential Job Titles for Medical Writers and Editors

- Content Specialist

- Medical Writer/Editor

- Regulatory Writer/Editor

- Technical Editor

Average salaries for Medical Writers and Editors

According to Glassdoor, the salaries of both medical writers and editors average around $97,000.

Focus Areas

- Specialization Track in Freelancing

Offered by The University of Chicago's Professional Education

Ready to Take Your Next Step?

Of interest.

- Non-Credit Certificate Program in Regulatory Writing

Gain in-demand medical writing skills that will help elevate your career in healthcare or medical...

Inescapable Ethics

Essential Courses on Medical Copyediting

From Freelancer to Founder

- Learning the Business of Freelance Medical Writing and Editing

- Explore the World of Medical Writing

- Partner With Us

- Custom Training

- Teach for Us

- My Extension

- Instructor Link

- Outreach Trainer Portal

- Search UCSD Division of Extended Studies

- Medical Writing

- Courses and programs

About the Medical Writing Program

Delivery method.

- Live Online

- Number of courses: 4 required courses (10 units) and 6 units of electives

- Total units: 16

Medical Terminology: An Anatomy and Physiology Approach FPM-40632

Units: 1.50

Using an anatomy and physiology systems approach, this course reviews common terms associated with medical practice, research, and different healthcare settings. The goal: to better prepare individual...

Upcoming Start Dates:

Grammar lab wcwp-40234.

Units: 3.00

Grammar Lab (WCWP-40234)10 Weeks | OnlineThis ten-week online Grammar Lab course is skillfully designed to meet the needs of all students. It is beneficial for those with little grammar experience and...

Clinical Trials and Regulatory Writing Primer FPM-40672

Units: 1.00

This course introduces the components of effective clinical trial design, and the basic phases, and purposes of pharmacological and clinical development. Gain foundational knowledge of the overall cl...

CT: Practical Clinical Statistics for the Non-Statistician FPM-40233

Units: 2.00

This course presents the statistics essentials for the non-statistician involved in clinical trials. Topics include study designs, hypothesis testing, sample size calculations, assumptions, controls, ...

Introduction to Medical Writing and Editing FPM-40696

Introduction to Medical Writing and Editing is intended for people who are considering a career in medical communication and is designed to introduce students to the profession of medical writing and ...

Applied Medical Writing and Editing FPM-40652

This course builds on the knowledge gained in the Introduction to Medical Writing and Editing course and introduces the student to some of the more complex topics in writing and editing scientific and...

Ethics for Medical Writers FPM-40609

This course covers the current tools and resources that should be used by medical writers who desire to practice their craft in an ethical manner. Students will be made aware of professional ethical c...

Designing Figures, Tables, & Graphs FPM-40608

This course focuses on how to construct effective, accurate and attractive figures, tables and graphs. Course content includes basic statistics, principles of the visual display of quantitative inform...

Communicating Real World Evidence; Medical Writer Professional Development FPM-40658

This course examines real world evidence (RWE), and the role of the professional medical writer in this rapidly expanding area of evidence generation. Learn the basics of RWE, and how and why these s...

Citations and Reference Methods for Medical Writing FPM-40660

This course covers the current tools and resources that should be used by medical writers to properly cite courses. Medical writers must be able to cite their work and correct the citations of others....

CT: Documents in Drug Development: Writing Protocols, Reports, Summaries, Submissions, and Disclosures FPM-40685

No clinical trial can begin until a protocol has been written, and no clinical trial is complete until the final report is assembled, signed, and submitted to the FDA. Good documentation for clinical ...

Health Economics and Outcomes Research (HEOR) FPM-40659

This course covers the foundations Health Economics Outcomes Research (HEOR) and demonstrates why this growing field provides important information for making healthcare coverage and access decisions....

Capstone: Journal Article and Publication Development FPM-40630

Units: 4.00

This course will benefit students who are seeking to write and publish an article in a peer-reviewed journal. Using knowledge acquired throughout the medical writing program, students in this capston...

Capstone: Medical Education Materials FPM-40627

Medical writers play a vital role in creating continuing medical education (CME) materials that help physicians and other health care providers remain current in the knowledge and skills needed to pro...

Capstone: Regulatory Writing FPM-40628

Regulatory Writing is as much about knowing the regulations and guidance that govern regulatory submissions as it is about the building the intelligence, knowledge, relationships, and know-how in beco...

Medical Writing Certificate Information Session

Watch an information session on earning a professional certificate in Medical Writing with program faculty at UC San Diego Extended Studies.

Conditions for Admission

Successful applicants must have relevant educational background, and native-level fluency in English with the demonstrated ability to write clear, logical, and grammatically correct sentences as evidenced by the application, official transcripts and writing samples. Accepted applicants will have degrees in biomedical or life sciences, such as biology, chemistry, pharmacy, nursing, nutrition, or public health. It is anticipated that many will have advanced degrees, including PhDs. Candidates with PhDs are particularly competitive for medical writing positions in the commercial sector and academic settings.

Certificate Guidelines

All students must either take the following prerequisites or have taken appropriate equivalents within the past five years, earning a grade of B- or better:

- Medical Terminology FPM-40172, 1 unit online

- Practical Clinical Statistics for the Non-Statistician FPM-40233, 2 units online

- Grammar Lab WCWP-40234, 3 units online

- Clinical Trials and Regulatory Writing Primer, FPM-40672, 1 unit online

Prerequisites can be waived for individuals whose work experience demonstrates foundational knowledge of these subjects. Applicants seeking this waiver should email their CV to Jessica Bradford, Program Manager, at [email protected] for determination in advance of their application.

Next Steps Experience

Connect your classroom education with real-world experiences through a Next Step Experience course. These specially designed classes allow students to gain hands-on experience by working closely with instructors and/or peers on real-world projects. In the Capstone course, students will apply all previously learned concepts to work through one or more projects in one of the four pre-identified Medical Writing areas. The purpose of the Capstone is to:

- Gain hands on experience of researching information, and analyzing, interpreting, and communicating data as would be expected of a Medical Writer. The final project(s) will be submitted for critical review by the advising faculty leader

- Have a clear sense of the critical behaviors and practical work practices that make the student a better Medical Writer.

- Identify areas of continued improvement moving forward to hone knowledge and skill in the evolving Medical Writing profession.

To be eligible to take this course, you must have completed all of the other courses in the Medical Writing program with a B-/80% or higher. You must select from one of the four areas of specialization to fulfill this final required component of the certificate.

Capstone: Journal Article and Publication Development (FPM-40630)

Capstone: Medical Education Materials (FPM-40627)

Capstone: Regulatory Writing (FPM-40628)

Capstone: Scientific Grants (FPM-40629)

Related Documents

- UCSD Extension Medical Writing Program Flier

- Medical Writing Workforce Data Study: October 2020

Advisory Board

Michelle Beauclair

Medical writer and copywriter

MB Medical Writer

Tim Collinson, BSc (hons), ISMPP CMPP

Director, Global Publications

Santen Inc.

Noelle Demas

Medical Writer

Panorama MedWriters Group, Inc.

Thomas Gegeny, MS, ELS, MWC, CMPP

Director, Scientific Strategy & Partnerships

Prime Global Medical Communications Ltd.

Timothy Mackey, MAS, PhD

Assistant Professor

UC San Diego School of Medicine

Related Articles

November 19, 2020

Making a Change: From Scientist to Medical Writer

Tanvir Khan switched from researcher to medical writer in less than a year by taking UCSD Extension’s Medical Writing certificate program. Now he’s fielding job offers and pursuing a refreshing new career path without missing a beat.

October 12, 2020

The Top 6 Healthcare Careers You Can Do From Home

Healthcare may not seem like an obvious work-from-home career option, but there are a number of professional areas perfect for working remotely. Check out our top 6 recommendations for this rapid growing industry.

June 19, 2019

How I Did It: Going from Medical Doctor to Medical Writer

What happens when you have multiple degrees and a talent for sharing complex information in a clear and thoughtful way? You write.

November 18, 2015

Turning science into sentences: The art of medical writing

Turning science into sentences – meaningful, factual and compelling sentences – is the art and the craft of medical writing. It is also a skill that is increasingly in demand. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, jobs for technical writers in the health care field are projected to grow nearly 27% from 2012 to 2022.

Programs you may also like:

Specialized Certificate

Spanish for Healthcare Professionals

Science communication, healthcare revenue cycle, stay updated.

Subscribe to our emails and be in the know about upcoming events, quarterly updates and new courses & programs. You can expect to receive course and workshop discounts, important resources and tailored information based on your interests.

UC San Diego Website Privacy Policy

The University of California, San Diego, is committed to protecting your privacy. The following Privacy Policy describes what information we collect from you when you visit this site, and how we use this information. Please read this Privacy Policy carefully so that you understand our privacy practices.

The information UC San Diego collects

UCSD collects two kinds of information on this site:

- Personal information that is voluntarily supplied by visitors to this site who register for and use services that require such information.

- Tracking information that is automatically collected as visitors navigate through this site.

If you choose to register for and use services on this site that require personal information, such as WebMail, WebCT, or MyBlink, you will be required to provide certain personal information that we need to process your request. This site automatically recognizes and records certain non-personal information, including the name of the domain and host.

This site also includes links to other websites hosted by third parties. When you access any such website from this site, use of any information you provide will be governed by the privacy policy of the operator of the site you are visiting.

How UC San Diego uses this information

We do not sell, trade, or rent your personal information to others. We may provide aggregated statistical data to reputable third-party agencies, but this data will include no personally identifying information. We may release account information when we believe, in good faith, that such release is reasonably necessary to:

- Comply with law.

- Enforce or apply the terms of any of our user agreements.

- Protect the rights, property or safety of UCSD, our users, or others.

Your consent

By using this website, you consent to the collection and use of this information by UCSD. If we decide to change our privacy policy, we will post those changes on this page before the changes take effect. Of course, our use of information gathered while the current policy is in effect will always be consistent with the current policy, even if we change that policy later.

If you have questions about this Privacy Policy, please contact us via this form .

This policy was last updated on November 27, 2007.

You've been subscribed

Request Information

Interested in the Program?

Your email has been sent.

Ready to get started?

This certificate requires an application before taking any courses. There will be a $25 fee to apply to this program. Students will also be required to pay a $95 certificate fee upon enrollment into the program after acceptance. View the complete Certificate Registration and Candidacy Guidelines.

Share the Medical Writing Certificate Program

.png)

Medical & Scientific Writer

Adriana Rocha, PhD

.png)

Medical Communications,

Scientific Writing & Editing

Freelance Services

.png)

▪ Medical & Scientific Writer

▪ scientific editor, phd in medical neurosciences.

International Graduate Program in Medical Neurosciences

Humboldt University || Charité Universitätsmedizin

Berlin, Germany

BSc in Bioch emistry

University of porto.

Porto, Portugal

I am Adriana Rocha, PhD, a freelance medical & scientific writer with a solid background in medical neurosciences

With my training and attention to d etail, I am a rigorous scientific writer and editor in Medical Communications .

I work with Pharmaceutical and Life Sciences companies , Medical Communication agencies , and Research Institutions , creating and editing high-quality content aimed at healthcare professionals and academics .

As a medical & scientific writer ,

I create materials to educate and allow professionals to communicate their work more effectively, from training modules to peer-reviewed publications, as well as slide decks and infographics.

As a scientific editor ,

I rigorously edit and proofread your project, ensuring the accuracy of all medical and scientific content. I also provide referencing and annotation, with strict adherence to the required style guides.

Professional Affiliations

Communications

Health c opywriting

Feature articles

Newsletters

Research summaries

Training and educational modules

Scientific Writing

Peer-reviewed publications

Abstracts and short communications

Visual communications

Slide decks

Infographics

Editing and Proofreading

Referencing and Annotation

Fact-check all medical and scientific content

Compliance with guidelines and style g uides (e.g. AMA Style)

Areas of expertise

Neurosciences

Neurodegenerative diseases

Mental He alth

Women's Health

Female Pelvic Floor Dysfunction: A Quick Guide to Diagnosis and Treatment

Infographic aimed at healthcare professionals

Social Media and the Rise of Predatory Journals: A Case Report

Article in collaboration with Petal Smart for Medical Writing, EMWA's official journal.

Aimed at all research, healthcare and publishing professionals that can be targeted by predatory journals.

Thanks for submitting!

Let’s Work Together

Get in touch to discuss your writing needs.

Fill the contact form or send me an email to get started.

Connect with me on LinkedIn

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Granting access: Development of a formal course to demystify and promote predoctoral fellowship applications for graduate students

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected] (PKG); [email protected] (CMB)

Affiliations Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, United States of America, Medical Scientist Training Program, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Medical Scientist Training Program, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, United States of America, Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, United States of America

Roles Project administration, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Scientific Editing and Research Communication Core, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, United States of America

- Pamela K. Geyer,

- Darren S. Hoffmann,

- Jennifer Y. Barr,

- Heather A. Widmayer,

- Christine M. Blaumueller

- Published: April 26, 2024

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0301480

- Reader Comments

Strong scientific writing skills are the foundation of a successful research career and require training and practice. Although these skills are critical for completing a PhD, most students receive little formal writing instruction prior to joining a graduate program. In 2015, the University of Iowa Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP) addressed this issue by developing the scientific writing course Grant Writing Basics (GWB). Here we describe the structure of this course and its effectiveness. GWB is an interactive, workshop-based course that uses a National Institutes of Health (NIH) F30 predoctoral fellowship proposal as a platform for building writing expertise. GWB incorporates established pedagogical principles of adult learning, including flipped classrooms, peer teaching, and reiterative evaluation. Time spent in class centers on active student analysis of previously submitted fellowship applications, discussion of writing resources, active writing, facilitated small group discussion of critiques of student writing samples, revision, and a discussion with a panel of experienced study section members and a student who completed a fellowship submission. Outcomes of GWB include a substantial increase in the number of applications submitted and fellowships awarded. Rigorous evaluation provides evidence that learning objectives were met and that students gained confidence in both their scientific writing skills and their ability to give constructive feedback. Our findings show that investment in formal training in written scientific communication provides a foundation for good writing habits, and the knowledge and skills needed to succeed in this vital aspect of a scientific research career. Furthermore, they highlight that evaluation is valuable in guiding course evolution. Strategies embedded in GWB can be adapted for use in any graduate program to advance scientific writing skills among its trainees.

Citation: Geyer PK, Hoffmann DS, Barr JY, Widmayer HA, Blaumueller CM (2024) Granting access: Development of a formal course to demystify and promote predoctoral fellowship applications for graduate students. PLoS ONE 19(4): e0301480. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0301480

Editor: Rea Lavi, Massachusetts Institute of Technology School of Engineering, UNITED STATES

Received: December 27, 2023; Accepted: March 16, 2024; Published: April 26, 2024

Copyright: © 2024 Geyer et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting information files.

Funding: This publication was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, T32 GM139776 to PKG. https://search.usa.gov/search?utf8=%E2%9C%93&affiliate=grants.nih.gov&query=t32&commit=Search The funding agency did not participate in study design.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Effective written communication is central to success in a scientific career. Scientists must share their research findings to garner funds and build successful research teams. Yet, writing scientific papers and grant proposals is inherently complex and requires considerable time and effort. Self-reported barriers to engagement in scientific writing, especially for early-career scientists, include lack of sufficient time and aptitude [ 1 ].

Effective writing is shaped by instruction and practice. Although such training should begin early in a scientific career, most undergraduate curricula include little formal instruction in scientific writing [ 2 ]. This deficit reflects the attitude that time spent learning writing skills is less important than time spent learning foundational scientific concepts. As a result, students enter graduate programs with limited practice in scientific writing, a core competency of PhD training programs [ 3 ]. This gap continues during graduate training, evidenced by a recent survey of MD-PhD programs revealing that few programs include writing courses in their curricula [ 4 ]. Indeed, in a recent survey of alumni of a molecular medicine PhD program, participants ranked “proficiency in academic and professional writing” as very important (4/4) for career success but ranked satisfaction with their preparation lower (3/4; [ 5 ]). These observations about gaps in training highlight a need for dedicated coursework in scientific writing.

Recognizing the importance of writing in scientific careers, the leadership of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded University of Iowa Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP) developed a course entitled Grant Writing Basics (GWB) to augment training of their MD-PhD dual-degree students, a cohort of talented trainees whose career goals include advancing the science of medicine and its translation into clinical practice. GWB uses the NIH F30 predoctoral fellowship application as a platform for instruction, given that this type of application is a relevant exercise, is a likely next step for many MSTP trainees, and represents an authentic learning experience. We reasoned that early participation in GWB would motivate students to develop key questions pertinent to their research interests, boost the amount of concentrated time that they spend on reading and critically analyzing the literature, increase their understanding of experimental design, and fine-tune their research goals. Additionally, students would practice delivering well-reasoned and concise scientific arguments to a knowledgeable but broad peer audience, building upon concepts that peer learning increases engagement and enhances knowledge [ 6 ]. These design choices align with principles of adult learning, including relevance, self-direction, ownership, and learning by doing [ 7 ]. Finally, submission of a fellowship proposal should provide students the opportunity to understand the mechanics of, and time commitments required for, the grant writing process, as well provide eligibility for institutional monetary recognition. GWB occurs early during the PhD training and helps establish a foundation for continued formal and informal writing instruction as students advance through their PhD programs.

The University of Iowa MSTP is not alone in adopting grant writing as a platform for instruction of scientific writing. Surveys of the landscape of grant writing instruction reveal that multiple formats are used, ranging from focused singular workshops to longitudinal courses and writing communities [ 4 , 8 – 11 ]. Common instructional features include identifying funding sources, decoding grant-specific language (e.g., specific aims, training plans), introducing students to the mechanics of the grant review process, and providing dedicated time for iterative writing that is focused on the application [ 9 , 11 ]. Notably, each grant writing course is highly contextualized, and built to suit the student population and grant writing norms of the discipline.

Here, we describe key aspects of GWB, including the evaluation process and our findings that resulted in the current course structure. We report that students have gained confidence in their grantsmanship and scientific writing abilities, have become more willing to seek feedback on their own work and are more assured about providing useful feedback to others, skills with long-lasting benefits. Our findings also highlight the value of rigorous evaluation in guiding iterative evolution of curricula. Together, our observations provide strong support for early training in written scientific communication.

Course participants

GWB is a one-credit course that is required for all third year MSTP students. This course was developed with the goals of building a learner’s autonomy, encouraging active learning experiences, inspiring ownership, and providing the structure needed to achieve learning objectives. Embedded in GWB are milestones that mark students’ progress, and opportunities for engagement as peer educators. These design features align with principles outlined in adult learning theory [ 7 , 12 , 13 ].

Each year, the course is taken by six to eleven students who are members of a single MSTP entering class. MSTP students have strong scientific backgrounds. In recent MSTP entering classes (2015 to 2019), most (~75%) students had completed one or more “gap years” during which they engaged in scientific research, and over half (55%) were co-authors on at least one paper. MSTP students have diverse scientific interests, evidenced by their enrollment in one of fifteen PhD programs across three colleges ( Table 1 ). The MSTP class composition has two major advantages. First, students have a shared history of training that provides the social capital and trust needed for giving and receiving honest and productive feedback. Second, given the diverse nature of research interests, the students are forced to write to a broad audience, in language that is clear and concise.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0301480.t001

Course description

GWB uses the NIH predoctoral F30 National Research Service Award (a funding mechanism specific to physician-scientists in training) as a platform for building writing expertise. Students take GWB in the spring semester of their first year of graduate training, after having completed two years of preclinical medical school requirements. At this stage, students have identified a research mentor, and most have begun research relevant to their dissertation topic. The third year of the MSTP is equivalent to the second semester of the second year of graduate training for most PhD students. The objectives of GWB are: 1) to learn the scientific logic that underlies effective grant writing; 2) to learn the value of revision; 3) to develop skills in providing and applying constructive feedback; and 4) to assume ownership of a research project. An additional expectation is that students will gain a better understanding of how to assemble a predoctoral fellowship. An unofficial expectation is that students will submit a full proposal for extramural funding. The final GWB writing product is a polished Specific Aims page that serves as a roadmap for a fellowship submission, and ideally for the student’s dissertation research.

GWB is taught by a team of instructors who integrate expertise in scientific investigation and communication. This team includes a member of the MSTP PhD training faculty (PKG) and scientists (henceforth referred to as “editors”) on the staff of the Scientific Editing and Research Communication Core in the Carver College of Medicine (CMB, JYB, HAW). We have found that this combination of trainers is highly effective, with the faculty member putting greater emphasis on scientific issues and the editors additionally providing substantive advice on effective writing strategies.

Course format

Weekly course sessions are one-and-a-half hours in length and are held over a three-month semester (11 weeks). Classes are interactive, workshop based, and delivered in four formats, as indicated in Table 2 . Five sessions are held in a large group setting and cover foundational material related to writing components of the F30 application and strategies for clarity in writing; four sessions are held in a small group setting (writing groups) and focus on peer driven critiques of Specific Aims pages submitted by the students; one session combines small and large group formats to help students sharpen the logic underlying their proposal; and one session is a panel discussion that features faculty who have reviewed fellowship applications as members of study sections and an MSTP student who has submitted a fellowship application.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0301480.t002

The five course sessions that cover foundational material are delivered using a flipped-classroom model, a teaching modality found to increase students’ motivation and engagement in learning [ 14 ]. Self-directed student learning includes review of pre-recorded lectures and two key resources: grant writing templates and examples of grant sections. Templates contain prompts and guidelines for each section of the fellowship and were developed by the editors based on NIH resources, the editors’ own experiences, and well-regarded grant writing workbooks [ 15 , 16 ]. Example texts are excerpts from previous NIH-funded fellowship proposals that either model effective scientific writing or could use improvement. Students are expected to be prepared to participate in a facilitated discussion of lessons learned from these examples and the lecture materials. Each session includes about one hour of group discussion on topics such as the Specific Aims page, Research Strategy, Biographical Sketch, or Training Plan ( Table 2 ) and thirty minutes during which students brainstorm and begin to write a section of the grant using the relevant template. Each session ends with a brief wrap-up discussion.

The four course sessions devoted to critiquing Specific Aims pages use a small group format with a high degree of structure that enables rounds of feedback from diverse sources. Each student submits a draft for two of these sessions. In an early session, they submit an initial draft, and in a follow up session, they submit a revised draft that addresses feedback received during the earlier discussion. Groups include one facilitator (an editor) and three to four students. Early in the course, students are introduced to concepts of giving and receiving feedback [ 17 ], and instructors emphasize the value of, and strategies for, doing so effectively. Examples of constructive feedback are provided to guide the written critiques the students prepare. They submit their draft of the Specific Aims page to members of their writing group (including the facilitator) and the faculty instructor one week before it is discussed. Writers are encouraged to include a letter outlining areas on which they wish to obtain feedback. Each Specific Aims page is pre-assigned to a primary reviewer, who provides detailed written and verbal feedback; the remaining students and facilitator also provide written and verbal commentary. Feedback from other students is not expected to be as detailed as that of the primary reviewer; feedback from the instructors is typically thorough. During the session, the primary reviewer introduces the proposed research project to the group and then summarizes the strengths of the writing and areas needing improvement. Next, other student reviewers contribute their ideas, and finally the facilitator provides comments and synthesizes the collective feedback. Students also receive written feedback from the faculty instructor. During the review of each Specific Aims page, the writer is present but initially silent; after the review is completed, the writer is invited to ask questions and share ideas for addressing the issues that were raised. Setting boundaries for the participation of the writer allows reviewers to complete their assessment of the document without the discussion digressing into the author’s intended meaning. The small size of the writing group ensures that the feedback provided to writers is manageable and comes from trusted peers and a facilitator. This approach fosters productive discussions. A revised version of the Specific Aims page is reviewed several weeks later, following the same structured format. In this session, discussion includes an assessment of how effectively the feedback from the first session was addressed.

Early in GWB, a single session is devoted to an exercise in refining the logic of the students’ research proposal through a storytelling approach [ 18 ]. This session is a supplement to the foundational presentation about the Specific Aims page, which is held the previous week ( Table 2 ). During this exercise, students are asked to think about the current status of their field of study, how they envision the field will advance in the future, and how their proposed research will promote change. Students are initially paired with a partner for a ten-minute discussion during which each presents their story to the other, switching off as “storyteller” and “reporter.” The large group then reconvenes, and each reporter retells the story they heard. In many cases, this exercise reveals logic gaps that the storyteller needs to fill when writing their Specific Aims page. This teaching exercise builds on what the students have already learned about writing a Specific Aims page, by requiring them to consider the logic underlying their proposal from a new angle and from a listener’s (and reader’s) perspective. This session has proven to be particularly helpful in refining the Specific Aims page, and it has helped students start thinking about the Significance section of the Research Strategy.

Midway through GWB, a single course session is devoted to a panel discussion. This session occurs in a large group setting and is facilitated by the faculty instructor. The panel consists of three to four faculty members who have served on predoctoral review panels for the NIH or private foundations and one senior MSTP student who has experience submitting a fellowship application. The panel session is held after students have been introduced to all sections of the fellowship application and have had the first draft of their Specific Aims page critiqued. This discussion provides insights into the score-driving components of a proposal, from both a faculty member’s and a student’s perspective. Notably, the panel discussion highlights that grant evaluation is subjective and reviewer-dependent; this helps overcome a commonly held misperception that reviews are necessarily objective. In addition, panelists share information about local resources and real-life experiences that have helped them develop successful proposals.

Evaluations of the GWB course

Evaluation procedures in this study included anonymous electronic course surveys and pre- and post-course interviews that were conducted by the editors and broadly evaluated a student’s experience. Evaluations were completed by students in nine classes of GWB students between 2015 and 2023. All interview notes and survey data were anonymized.

In years 2015 and 2016 (n = 19 students), course evaluation was conducted in class, during the final course session. In years 2017 to 2023 (n = 63 students), anonymous electronic surveys were administered at the end of the course. Survey questions were answered using a five-point Likert agreement scale. Scaled response items are summarized in Table 3 . In addition, three open field questions were asked, including 1) What strategies do you find most useful? 2) What changes might improve the templates? and 3) Have you overcome problems that you previously experienced in writing? The response rate for electronic course evaluations was 97% (61/63).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0301480.t003

In years 2020 to 2023 (n = 32 students), pre- and post-course interviews were conducted by the team of editors, who interviewed each individual student. During the interviews, students were reminded that responses would be made confidential and held no weight in their standing in the program. Notably, the interviewers did not hold an ongoing authoritative role with the students, reducing impacts of perceived power dynamics. An open-question format was used to develop an understanding of students’ experience, in their own words. Pre-course interviews enabled the instructional team to informally assess student expectations and experiences, and to develop trust that promoted honest class discussions. Post-course interviews enabled a deeper exploration of the extent to which GWB fostered knowledge and skill development in grant writing, areas for continued personal growth, and other course outcomes. Post-course interview questions touched on strengths of the course format and areas for improvement. One member of the interview team (CMB) took detailed notes during the interviews. After the interview, notes were reviewed by the interview team to fill any gaps that were missed. Then, the interview note taker determined the frequency of responses to establish initial response codes. Subsequently, the MSTP program evaluator (DSH) conducted a thematic analysis of consolidated data that involved clustering themes into categories and re-analyzing the data in a focused coding step. Pre- and post-course interview scripts are provided in S1 Appendix .

Ethics statement

The University of Iowa institutional review board determined that the evaluation of GWB impact did not meet the regulatory definition of human subjects research after review (IRB #202302103).

Electronic evaluations and changes to course structure

Anonymous electronic course evaluations revealed enthusiastic endorsement of GWB ( Table 3 ). Of the 63 students surveyed, most (95%) agreed that their knowledge of how to write a grant proposal had improved. Most (92%) also found that the grant-writing templates developed by the editing core were useful, with answers to free-form questions indicating that these resources effectively prompted development of sections of the proposal. For example, students indicated that the template for the Specific Aims page “Helps with blank page anxiety” and “Provides a place to get started,” endorsing the use of grant writing templates in aiding the writing process.