- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Back to Entry

- Entry Contents

- Entry Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Supplement to Critical Thinking

How can one assess, for purposes of instruction or research, the degree to which a person possesses the dispositions, skills and knowledge of a critical thinker?

In psychometrics, assessment instruments are judged according to their validity and reliability.

Roughly speaking, an instrument is valid if it measures accurately what it purports to measure, given standard conditions. More precisely, the degree of validity is “the degree to which evidence and theory support the interpretations of test scores for proposed uses of tests” (American Educational Research Association 2014: 11). In other words, a test is not valid or invalid in itself. Rather, validity is a property of an interpretation of a given score on a given test for a specified use. Determining the degree of validity of such an interpretation requires collection and integration of the relevant evidence, which may be based on test content, test takers’ response processes, a test’s internal structure, relationship of test scores to other variables, and consequences of the interpretation (American Educational Research Association 2014: 13–21). Criterion-related evidence consists of correlations between scores on the test and performance on another test of the same construct; its weight depends on how well supported is the assumption that the other test can be used as a criterion. Content-related evidence is evidence that the test covers the full range of abilities that it claims to test. Construct-related evidence is evidence that a correct answer reflects good performance of the kind being measured and an incorrect answer reflects poor performance.

An instrument is reliable if it consistently produces the same result, whether across different forms of the same test (parallel-forms reliability), across different items (internal consistency), across different administrations to the same person (test-retest reliability), or across ratings of the same answer by different people (inter-rater reliability). Internal consistency should be expected only if the instrument purports to measure a single undifferentiated construct, and thus should not be expected of a test that measures a suite of critical thinking dispositions or critical thinking abilities, assuming that some people are better in some of the respects measured than in others (for example, very willing to inquire but rather closed-minded). Otherwise, reliability is a necessary but not a sufficient condition of validity; a standard example of a reliable instrument that is not valid is a bathroom scale that consistently under-reports a person’s weight.

Assessing dispositions is difficult if one uses a multiple-choice format with known adverse consequences of a low score. It is pretty easy to tell what answer to the question “How open-minded are you?” will get the highest score and to give that answer, even if one knows that the answer is incorrect. If an item probes less directly for a critical thinking disposition, for example by asking how often the test taker pays close attention to views with which the test taker disagrees, the answer may differ from reality because of self-deception or simple lack of awareness of one’s personal thinking style, and its interpretation is problematic, even if factor analysis enables one to identify a distinct factor measured by a group of questions that includes this one (Ennis 1996). Nevertheless, Facione, Sánchez, and Facione (1994) used this approach to develop the California Critical Thinking Dispositions Inventory (CCTDI). They began with 225 statements expressive of a disposition towards or away from critical thinking (using the long list of dispositions in Facione 1990a), validated the statements with talk-aloud and conversational strategies in focus groups to determine whether people in the target population understood the items in the way intended, administered a pilot version of the test with 150 items, and eliminated items that failed to discriminate among test takers or were inversely correlated with overall results or added little refinement to overall scores (Facione 2000). They used item analysis and factor analysis to group the measured dispositions into seven broad constructs: open-mindedness, analyticity, cognitive maturity, truth-seeking, systematicity, inquisitiveness, and self-confidence (Facione, Sánchez, and Facione 1994). The resulting test consists of 75 agree-disagree statements and takes 20 minutes to administer. A repeated disturbing finding is that North American students taking the test tend to score low on the truth-seeking sub-scale (on which a low score results from agreeing to such statements as the following: “To get people to agree with me I would give any reason that worked”. “Everyone always argues from their own self-interest, including me”. “If there are four reasons in favor and one against, I’ll go with the four”.) Development of the CCTDI made it possible to test whether good critical thinking abilities and good critical thinking dispositions go together, in which case it might be enough to teach one without the other. Facione (2000) reports that administration of the CCTDI and the California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCTST) to almost 8,000 post-secondary students in the United States revealed a statistically significant but weak correlation between total scores on the two tests, and also between paired sub-scores from the two tests. The implication is that both abilities and dispositions need to be taught, that one cannot expect improvement in one to bring with it improvement in the other.

A more direct way of assessing critical thinking dispositions would be to see what people do when put in a situation where the dispositions would reveal themselves. Ennis (1996) reports promising initial work with guided open-ended opportunities to give evidence of dispositions, but no standardized test seems to have emerged from this work. There are however standardized aspect-specific tests of critical thinking dispositions. The Critical Problem Solving Scale (Berman et al. 2001: 518) takes as a measure of the disposition to suspend judgment the number of distinct good aspects attributed to an option judged to be the worst among those generated by the test taker. Stanovich, West and Toplak (2011: 800–810) list tests developed by cognitive psychologists of the following dispositions: resistance to miserly information processing, resistance to myside thinking, absence of irrelevant context effects in decision-making, actively open-minded thinking, valuing reason and truth, tendency to seek information, objective reasoning style, tendency to seek consistency, sense of self-efficacy, prudent discounting of the future, self-control skills, and emotional regulation.

It is easier to measure critical thinking skills or abilities than to measure dispositions. The following eight currently available standardized tests purport to measure them: the Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal (Watson & Glaser 1980a, 1980b, 1994), the Cornell Critical Thinking Tests Level X and Level Z (Ennis & Millman 1971; Ennis, Millman, & Tomko 1985, 2005), the Ennis-Weir Critical Thinking Essay Test (Ennis & Weir 1985), the California Critical Thinking Skills Test (Facione 1990b, 1992), the Halpern Critical Thinking Assessment (Halpern 2016), the Critical Thinking Assessment Test (Center for Assessment & Improvement of Learning 2017), the Collegiate Learning Assessment (Council for Aid to Education 2017), the HEIghten Critical Thinking Assessment (https://territorium.com/heighten/), and a suite of critical thinking assessments for different groups and purposes offered by Insight Assessment (https://www.insightassessment.com/products). The Critical Thinking Assessment Test (CAT) is unique among them in being designed for use by college faculty to help them improve their development of students’ critical thinking skills (Haynes et al. 2015; Haynes & Stein 2021). Also, for some years the United Kingdom body OCR (Oxford Cambridge and RSA Examinations) awarded AS and A Level certificates in critical thinking on the basis of an examination (OCR 2011). Many of these standardized tests have received scholarly evaluations at the hands of, among others, Ennis (1958), McPeck (1981), Norris and Ennis (1989), Fisher and Scriven (1997), Possin (2008, 2013a, 2013b, 2013c, 2014, 2020) and Hatcher and Possin (2021). Their evaluations provide a useful set of criteria that such tests ideally should meet, as does the description by Ennis (1984) of problems in testing for competence in critical thinking: the soundness of multiple-choice items, the clarity and soundness of instructions to test takers, the information and mental processing used in selecting an answer to a multiple-choice item, the role of background beliefs and ideological commitments in selecting an answer to a multiple-choice item, the tenability of a test’s underlying conception of critical thinking and its component abilities, the set of abilities that the test manual claims are covered by the test, the extent to which the test actually covers these abilities, the appropriateness of the weighting given to various abilities in the scoring system, the accuracy and intellectual honesty of the test manual, the interest of the test to the target population of test takers, the scope for guessing, the scope for choosing a keyed answer by being test-wise, precautions against cheating in the administration of the test, clarity and soundness of materials for training essay graders, inter-rater reliability in grading essays, and clarity and soundness of advance guidance to test takers on what is required in an essay. Rear (2019) has challenged the use of standardized tests of critical thinking as a way to measure educational outcomes, on the grounds that they (1) fail to take into account disputes about conceptions of critical thinking, (2) are not completely valid or reliable, and (3) fail to evaluate skills used in real academic tasks. He proposes instead assessments based on discipline-specific content.

There are also aspect-specific standardized tests of critical thinking abilities. Stanovich, West and Toplak (2011: 800–810) list tests of probabilistic reasoning, insights into qualitative decision theory, knowledge of scientific reasoning, knowledge of rules of logical consistency and validity, and economic thinking. They also list instruments that probe for irrational thinking, such as superstitious thinking, belief in the superiority of intuition, over-reliance on folk wisdom and folk psychology, belief in “special” expertise, financial misconceptions, overestimation of one’s introspective powers, dysfunctional beliefs, and a notion of self that encourages egocentric processing. They regard these tests along with the previously mentioned tests of critical thinking dispositions as the building blocks for a comprehensive test of rationality, whose development (they write) may be logistically difficult and would require millions of dollars.

A superb example of assessment of an aspect of critical thinking ability is the Test on Appraising Observations (Norris & King 1983, 1985, 1990a, 1990b), which was designed for classroom administration to senior high school students. The test focuses entirely on the ability to appraise observation statements and in particular on the ability to determine in a specified context which of two statements there is more reason to believe. According to the test manual (Norris & King 1985, 1990b), a person’s score on the multiple-choice version of the test, which is the number of items that are answered correctly, can justifiably be given either a criterion-referenced or a norm-referenced interpretation.

On a criterion-referenced interpretation, those who do well on the test have a firm grasp of the principles for appraising observation statements, and those who do poorly have a weak grasp of them. This interpretation can be justified by the content of the test and the way it was developed, which incorporated a method of controlling for background beliefs articulated and defended by Norris (1985). Norris and King synthesized from judicial practice, psychological research and common-sense psychology 31 principles for appraising observation statements, in the form of empirical generalizations about tendencies, such as the principle that observation statements tend to be more believable than inferences based on them (Norris & King 1984). They constructed items in which exactly one of the 31 principles determined which of two statements was more believable. Using a carefully constructed protocol, they interviewed about 100 students who responded to these items in order to determine the thinking that led them to choose the answers they did (Norris & King 1984). In several iterations of the test, they adjusted items so that selection of the correct answer generally reflected good thinking and selection of an incorrect answer reflected poor thinking. Thus they have good evidence that good performance on the test is due to good thinking about observation statements and that poor performance is due to poor thinking about observation statements. Collectively, the 50 items on the final version of the test require application of 29 of the 31 principles for appraising observation statements, with 13 principles tested by one item, 12 by two items, three by three items, and one by four items. Thus there is comprehensive coverage of the principles for appraising observation statements. Fisher and Scriven (1997: 135–136) judge the items to be well worked and sound, with one exception. The test is clearly written at a grade 6 reading level, meaning that poor performance cannot be attributed to difficulties in reading comprehension by the intended adolescent test takers. The stories that frame the items are realistic, and are engaging enough to stimulate test takers’ interest. Thus the most plausible explanation of a given score on the test is that it reflects roughly the degree to which the test taker can apply principles for appraising observations in real situations. In other words, there is good justification of the proposed interpretation that those who do well on the test have a firm grasp of the principles for appraising observation statements and those who do poorly have a weak grasp of them.

To get norms for performance on the test, Norris and King arranged for seven groups of high school students in different types of communities and with different levels of academic ability to take the test. The test manual includes percentiles, means, and standard deviations for each of these seven groups. These norms allow teachers to compare the performance of their class on the test to that of a similar group of students.

Copyright © 2022 by David Hitchcock < hitchckd @ mcmaster . ca >

- Accessibility

Support SEP

Mirror sites.

View this site from another server:

- Info about mirror sites

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is copyright © 2024 by The Metaphysics Research Lab , Department of Philosophy, Stanford University

Library of Congress Catalog Data: ISSN 1095-5054

Critical Thinking About Measuring Critical Thinking

A list of critical thinking measures..

Posted May 18, 2018

- What Is Cognition?

- Find a therapist near me

In my last post , I discussed the nature of engaging the critical thinking (CT) process and made mention of individuals who draw a conclusion and wind up being correct. But, just because they’re right, it doesn’t mean they used CT to get there. I exemplified this through an observation made in recent years regarding extant measures of CT, many of which assess CT via multiple-choice questions. In the case of CT MCQs, you can guess the "right" answer 20-25% of the time, without any need for CT. So, the question is, are these CT measures really measuring CT?

As my previous articles explain, CT is a metacognitive process consisting of a number of sub-skills and dispositions, that, when applied through purposeful, self-regulatory, reflective judgment, increase the chances of producing a logical solution to a problem or a valid conclusion to an argument (Dwyer, 2017; Dwyer, Hogan & Stewart, 2014). Most definitions, though worded differently, tend to agree with this perspective – it consists of certain dispositions, specific skills and a reflective sensibility that governs application of these skills. That’s how it’s defined; however, it’s not necessarily how it’s been operationally defined.

Operationally defining something refers to defining the terms of the process or measure required to determine the nature and properties of a phenomenon. Simply, it is defining the concept with respect to how it can be done, assessed or measured. If the manner in which you measure something does not match, or assess the parameters set out in the way in which you define it, then you have not been successful in operationally defining it.

Though most theoretical definitions of CT are similar, the manner in which they vary often impedes the construction of an integrated theoretical account of how best to measure CT skills. As a result, researchers and educators must consider the wide array of CT measures available, in order to identify the best and the most appropriate measures, based on the CT conceptualisation used for training. There are various extant CT measures – the most popular amongst them include the Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Assessment (WGCTA; Watson & Glaser, 1980), the Cornell Critical Thinking Test (CCTT; Ennis, Millman & Tomko, 1985), the California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCTST; Facione, 1990a), the Ennis-Weir Critical Thinking Essay Test (EWCTET; Ennis & Weir, 1985) and the Halpern Critical Thinking Assessment (Halpern, 2010).

It has been noted by some commentators that these different measures of CT ability may not be directly comparable (Abrami et al., 2008). For example, the WGCTA consists of 80 MCQs that measure the ability to draw inferences; recognise assumptions; evaluate arguments; and use logical interpretation and deductive reasoning (Watson & Glaser, 1980). The CCTT consists of 52 MCQs which measure skills of critical thinking associated with induction; deduction; observation and credibility; definition and assumption identification; and meaning and fallacies. Finally, the CCTST consists of 34 multiple-choice questions (MCQs) and measures CT according to the core skills of analysis, evaluation and inference, as well as inductive and deductive reasoning.

As addressed above, the MCQ-format of these three assessments is less than ideal – problematic even, because it allows test-takers to simply guess when they do not know the correct answer, instead of demonstrating their ability to critically analyse and evaluate problems and infer solutions to those problems (Ku, 2009). Furthermore, as argued by Halpern (2003), the MCQ format makes the assessment a test of verbal and quantitative knowledge rather than CT (i.e. because one selects from a list of possible answers rather than determining one’s own criteria for developing an answer). The measurement of CT through MCQs is also problematic given the potential incompatibility between the conceptualisation of CT that shapes test construction and its assessment using MCQs. That is, MCQ tests assess cognitive capacities associated with identifying single right-or-wrong answers and as a result, this approach to testing is unable to provide a direct measure of test-takers’ use of metacognitive processes such as CT, reflective judgment, and disposition towards CT.

Instead of using MCQ items, a better measure of CT might ask open-ended questions, which would allow test-takers to demonstrate whether or not they spontaneously use a specific CT skill. One commonly used CT assessment, mentioned above, that employs an open-ended format is the Ennis-Weir Critical Thinking Essay Test (EWCTET; Ennis & Weir, 1985). The EWCTET is an essay-based assessment of the test-taker’s ability to analyse, evaluate, and respond to arguments and debates in real-world situations (Ennis & Weir, 1985; see Ku, 2009 for a discussion). The authors of the EWCTET provide what they call a “rough, somewhat overlapping list of areas of critical thinking competence”, measured by their test (Ennis & Weir, 1985, p. 1). However, this test, too, has been criticised – for its domain-specific nature (Taube, 1997), the subjectivity of its scoring protocol and its bias in favour of those proficient in writing (Adams, Whitlow, Stover & Johnson, 1996).

Another, more recent CT assessment that utilises an open-ended format is the Halpern Critical Thinking Assessment (HCTA; Halpern, 2010). The HCTA consists of 25 open-ended questions based on believable, everyday situations, followed by 25 specific questions that probe for the reasoning behind each answer. The multi-part nature of the questions makes it possible to assess the ability to use specific CT skills when the prompt is provided (Ku, 2009). The HCTA’s scoring protocol also provides comprehensible, unambiguous instructions for how to evaluate responses by breaking them down into clear, measurable components. Questions on the HCTA represent five categories of CT application: hypothesis testing (e.g. understanding the limits of correlational reasoning and how to know when causal claims cannot be made), verbal reasoning (e.g. recognising the use of pervasive or misleading language), argumentation (e.g. recognising the structure of arguments, how to examine the credibility of a source and how to judge one’s own arguments), judging likelihood and uncertainty (e.g. applying relevant principles of probability, how to avoid overconfidence in certain situations) and problem-solving (e.g. identifying the problem goal, generating and selecting solutions among alternatives).

Up until the development of the HCTA, I would have recommended the CCTST for measuring CT, despite its limitations. What’s nice about the CCTST is that it assesses the three core skills of CT: analysis, evaluation, and inference, which other scales do not (explicitly). So, if you were interested in assessing students’ sub-skill ability, this would be helpful. However, as we know, though CT skill performance is a sequence, it is also a collation of these skills – meaning that for any given problem or topic, each skill is necessary. By administrating an analysis problem, an evaluation problem and an inference problem, in which the student scores top marks for all three, it doesn’t guarantee that the student will apply these three to a broader problem that requires all three. That is, these questions don’t measure CT skill ability per se, rather analysis skill, evaluation skill and inference skill in isolation. Simply, scores may predict CT skill performance, but they don’t measure it.

What may be a better indicator of CT performance is assessment of CT application . As addressed above, there are five general applications of CT: hypothesis testing, verbal reasoning, argumentation, problem-solving and judging likelihood and uncertainty – all of which require a collation of analysis, evaluation, and inference. Though the sub-skills of analysis, evaluation, and inference are not directly measured in this case, their collation is measured through five distinct applications; and, as I see it, provides a 'truer' assessment of CT. In addition to assessing CT via an open-ended, short-answer format, the HCTA measures CT according to the five applications of CT; thus, I recommend its use for measuring CT.

However, that’s not to say that the HCTA is perfect. Though it consists of 25 open-ended questions, followed by 25 specific questions that probe for the reasoning behind each answer, when I first used it to assess a sample of students, I found that in setting up my data file, there were actually 165 opportunities for scoring across the test. Past research recommends that the assessment takes roughly between 45 and 60 minutes to complete. However, many of my participants reported it requiring closer to two hours (sometimes longer). It’s a long assessment – thorough, but long. Fortunately, adapted, shortened versions are now available, and it’s an adapted version that I currently administrate to assess CT. Another limitation is that, despite the rationale above, it would be nice to have some indication of how participants get on with the sub-skills of analysis, evaluation, and inference, as I do think there’s a potential predictive element in the relationship among the individual skills and the applications. With that, I suppose it is feasible to administer both the HCTA and CCTST to assess such hypotheses.

Though it’s obviously important to consider how assessments actually measure CT and the nature in which each is limited, the broader, macro-problem still requires thought. Just as conceptualisations of CT vary, so too does the reliability and validity of the different CT measures, which has led Abrami and colleagues (2008, p. 1104) to ask: “How will we know if one intervention is more beneficial than another if we are uncertain about the validity and reliability of the outcome measures?” Abrami and colleagues add that, even when researchers explicitly declare that they are assessing CT, there still remains the major challenge of ensuring that measured outcomes are related, in some meaningful way, to the conceptualisation and operational definition of CT that informed the teaching practice in cases of interventional research. Often, the relationship between the concepts of CT that are taught and those that are assessed is unclear, and a large majority of studies in this area include no theory to help elucidate these relationships.

In conclusion, solving the problem of consistency across CT conceptualisation, training, and measure is no easy task. I think recent advancements in CT scale development (e.g. the development of the HCTA and its adapted versions) have eased the problem, given that they now bridge the gap between current theory and practical assessment. However, such advances need to be made clearer to interested populations. As always, I’m very interested in hearing from any readers who may have any insight or suggestions!

Abrami, P. C., Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Wade, A., Surkes, M. A., Tamim, R., & Zhang, D. (2008). Instructional interventions affecting critical thinking skills and dispositions: A stage 1 meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 78(4), 1102–1134.

Adams, M.H., Whitlow, J.F., Stover, L.M., & Johnson, K.W. (1996). Critical thinking as an educational outcome: An evaluation of current tools of measurement. Nurse Educator, 21, 23–32.

Dwyer, C.P. (2017). Critical thinking: Conceptual perspectives and practical guidelines. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Dwyer, C.P., Hogan, M.J. & Stewart, I. (2014). An integrated critical thinking framework for the 21st century. Thinking Skills & Creativity, 12, 43-52.

Ennis, R.H., Millman, J., & Tomko, T.N. (1985). Cornell critical thinking tests. CA: Critical Thinking Co.

Ennis, R.H., & Weir, E. (1985). The Ennis-Weir critical thinking essay test. Pacific Grove, CA: Midwest Publications.

Facione, P. A. (1990a). The California critical thinking skills test (CCTST): Forms A and B;The CCTST test manual. Millbrae, CA: California Academic Press.

Facione, P.A. (1990b). The Delphi report: Committee on pre-college philosophy. Millbrae, CA: California Academic Press.

Halpern, D. F. (2003b). The “how” and “why” of critical thinking assessment. In D. Fasko (Ed.), Critical thinking and reasoning: Current research, theory and practice. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Halpern, D.F. (2010). The Halpern critical thinking assessment: Manual. Vienna: Schuhfried.

Ku, K.Y.L. (2009). Assessing students’ critical thinking performance: Urging for measurements using multi-response format. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 4, 1, 70- 76.

Taube, K.T. (1997). Critical thinking ability and disposition as factors of performance on a written critical thinking test. Journal of General Education, 46, 129-164.

Watson, G., & Glaser, E.M. (1980). Watson-Glaser critical thinking appraisal. New York: Psychological Corporation.

Christopher Dwyer, Ph.D., is a lecturer at the Technological University of the Shannon in Athlone, Ireland.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Critical thinking disposition as a measure of competent clinical judgment: the development of the California Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Physiological Nursing, School of Nursing, UCSF 94143.

- PMID: 7799093

- DOI: 10.3928/0148-4834-19941001-05

Assessing critical thinking skills and disposition is crucial in nursing education and research. The California Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory (CCTDI) uses the Delphi Report's consensus definition of critical thinking as the theoretical basis to measure critical thinking disposition. Item analysis and factor analysis techniques were used to create seven disposition scales, which grouped the Delphi dispositional descriptions into larger, more unified constructs: open-mindedness, analyticity, cognitive maturity, truth-seeking, systematicity, inquisitiveness, and self-confidence. Cronbach's alpha for the overall instrument, the disposition toward critical thinking, is .92. The 75-item instrument was administered to an additional sample of college students (N = 1019). The alpha levels in the second sample remained relatively stable, ranging from .60 to .78 on the subscales and .90 overall. The instrument has subsequently been used to assess critical thinking disposition in high school through the graduate level but is targeted primarily for the college undergraduates. Administration time is 20 minutes. Correlation with its companion instrument, the California Critical Thinking Skills Test, also based on the Delphi critical thinking construct, was measured at .66 and .67 in two pilot sample groups.

- Delphi Technique

- Education, Nursing*

- Factor Analysis, Statistical

- Nursing Research

- Psychological Tests*

- Psychometrics

- Reproducibility of Results

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

How do critical thinking ability and critical thinking disposition relate to the mental health of university students.

- School of Education, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China

Theories of psychotherapy suggest that human mental problems associate with deficiencies in critical thinking. However, it currently remains unclear whether both critical thinking skill and critical thinking disposition relate to individual differences in mental health. This study explored whether and how the critical thinking ability and critical thinking disposition of university students associate with individual differences in mental health in considering impulsivity that has been revealed to be closely related to both critical thinking and mental health. Regression and structural equation modeling analyses based on a Chinese university student sample ( N = 314, 198 females, M age = 18.65) revealed that critical thinking skill and disposition explained a unique variance of mental health after controlling for impulsivity. Furthermore, the relationship between critical thinking and mental health was mediated by motor impulsivity (acting on the spur of the moment) and non-planning impulsivity (making decisions without careful forethought). These findings provide a preliminary account of how human critical thinking associate with mental health. Practically, developing mental health promotion programs for university students is suggested to pay special attention to cultivating their critical thinking dispositions and enhancing their control over impulsive behavior.

Introduction

Although there is no consistent definition of critical thinking (CT), it is usually described as “purposeful, self-regulatory judgment that results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as explanations of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations that judgment is based upon” ( Facione, 1990 , p. 2). This suggests that CT is a combination of skills and dispositions. The skill aspect mainly refers to higher-order cognitive skills such as inference, analysis, and evaluation, while the disposition aspect represents one's consistent motivation and willingness to use CT skills ( Dwyer, 2017 ). An increasing number of studies have indicated that CT plays crucial roles in the activities of university students such as their academic performance (e.g., Ghanizadeh, 2017 ; Ren et al., 2020 ), professional work (e.g., Barry et al., 2020 ), and even the ability to cope with life events (e.g., Butler et al., 2017 ). An area that has received less attention is how critical thinking relates to impulsivity and mental health. This study aimed to clarify the relationship between CT (which included both CT skill and CT disposition), impulsivity, and mental health among university students.

Relationship Between Critical Thinking and Mental Health

Associating critical thinking with mental health is not without reason, since theories of psychotherapy have long stressed a linkage between mental problems and dysfunctional thinking ( Gilbert, 2003 ; Gambrill, 2005 ; Cuijpers, 2019 ). Proponents of cognitive behavioral therapy suggest that the interpretation by people of a situation affects their emotional, behavioral, and physiological reactions. Those with mental problems are inclined to bias or heuristic thinking and are more likely to misinterpret neutral or even positive situations ( Hollon and Beck, 2013 ). Therefore, a main goal of cognitive behavioral therapy is to overcome biased thinking and change maladaptive beliefs via cognitive modification skills such as objective understanding of one's cognitive distortions, analyzing evidence for and against one's automatic thinking, or testing the effect of an alternative way of thinking. Achieving these therapeutic goals requires the involvement of critical thinking, such as the willingness and ability to critically analyze one's thoughts and evaluate evidence and arguments independently of one's prior beliefs. In addition to theoretical underpinnings, characteristics of university students also suggest a relationship between CT and mental health. University students are a risky population in terms of mental health. They face many normative transitions (e.g., social and romantic relationships, important exams, financial pressures), which are stressful ( Duffy et al., 2019 ). In particular, the risk increases when students experience academic failure ( Lee et al., 2008 ; Mamun et al., 2021 ). Hong et al. (2010) found that the stress in Chinese college students was primarily related to academic, personal, and negative life events. However, university students are also a population with many resources to work on. Critical thinking can be considered one of the important resources that students are able to use ( Stupple et al., 2017 ). Both CT skills and CT disposition are valuable qualities for college students to possess ( Facione, 1990 ). There is evidence showing that students with a higher level of CT are more successful in terms of academic performance ( Ghanizadeh, 2017 ; Ren et al., 2020 ), and that they are better at coping with stressful events ( Butler et al., 2017 ). This suggests that that students with higher CT are less likely to suffer from mental problems.

Empirical research has reported an association between CT and mental health among college students ( Suliman and Halabi, 2007 ; Kargar et al., 2013 ; Yoshinori and Marcus, 2013 ; Chen and Hwang, 2020 ; Ugwuozor et al., 2021 ). Most of these studies focused on the relationship between CT disposition and mental health. For example, Suliman and Halabi (2007) reported that the CT disposition of nursing students was positively correlated with their self-esteem, but was negatively correlated with their state anxiety. There is also a research study demonstrating that CT disposition influenced the intensity of worry in college students either by increasing their responsibility to continue thinking or by enhancing the detached awareness of negative thoughts ( Yoshinori and Marcus, 2013 ). Regarding the relationship between CT ability and mental health, although there has been no direct evidence, there were educational programs examining the effect of teaching CT skills on the mental health of adolescents ( Kargar et al., 2013 ). The results showed that teaching CT skills decreased somatic symptoms, anxiety, depression, and insomnia in adolescents. Another recent CT skill intervention also found a significant reduction in mental stress among university students, suggesting an association between CT skills and mental health ( Ugwuozor et al., 2021 ).

The above research provides preliminary evidence in favor of the relationship between CT and mental health, in line with theories of CT and psychotherapy. However, previous studies have focused solely on the disposition aspect of CT, and its link with mental health. The ability aspect of CT has been largely overlooked in examining its relationship with mental health. Moreover, although the link between CT and mental health has been reported, it remains unknown how CT (including skill and disposition) is associated with mental health.

Impulsivity as a Potential Mediator Between Critical Thinking and Mental Health

One important factor suggested by previous research in accounting for the relationship between CT and mental health is impulsivity. Impulsivity is recognized as a pattern of action without regard to consequences. Patton et al. (1995) proposed that impulsivity is a multi-faceted construct that consists of three behavioral factors, namely, non-planning impulsiveness, referring to making a decision without careful forethought; motor impulsiveness, referring to acting on the spur of the moment; and attentional impulsiveness, referring to one's inability to focus on the task at hand. Impulsivity is prominent in clinical problems associated with psychiatric disorders ( Fortgang et al., 2016 ). A number of mental problems are associated with increased impulsivity that is likely to aggravate clinical illnesses ( Leclair et al., 2020 ). Moreover, a lack of CT is correlated with poor impulse control ( Franco et al., 2017 ). Applications of CT may reduce impulsive behaviors caused by heuristic and biased thinking when one makes a decision ( West et al., 2008 ). For example, Gregory (1991) suggested that CT skills enhance the ability of children to anticipate the health or safety consequences of a decision. Given this, those with high levels of CT are expected to take a rigorous attitude about the consequences of actions and are less likely to engage in impulsive behaviors, which may place them at a low risk of suffering mental problems. To the knowledge of the authors, no study has empirically tested whether impulsivity accounts for the relationship between CT and mental health.

This study examined whether CT skill and disposition are related to the mental health of university students; and if yes, how the relationship works. First, we examined the simultaneous effects of CT ability and CT disposition on mental health. Second, we further tested whether impulsivity mediated the effects of CT on mental health. To achieve the goals, we collected data on CT ability, CT disposition, mental health, and impulsivity from a sample of university students. The results are expected to shed light on the mechanism of the association between CT and mental health.

Participants and Procedure

A total of 314 university students (116 men) with an average age of 18.65 years ( SD = 0.67) participated in this study. They were recruited by advertisements from a local university in central China and majoring in statistics and mathematical finance. The study protocol was approved by the Human Subjects Review Committee of the Huazhong University of Science and Technology. Each participant signed a written informed consent describing the study purpose, procedure, and right of free. All the measures were administered in a computer room. The participants were tested in groups of 20–30 by two research assistants. The researchers and research assistants had no formal connections with the participants. The testing included two sections with an interval of 10 min, so that the participants had an opportunity to take a break. In the first section, the participants completed the syllogistic reasoning problems with belief bias (SRPBB), the Chinese version of the California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCSTS-CV), and the Chinese Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory (CCTDI), respectively. In the second session, they completed the Barrett Impulsivity Scale (BIS-11), Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21), and University Personality Inventory (UPI) in the given order.

Measures of Critical Thinking Ability

The Chinese version of the California Critical Thinking Skills Test was employed to measure CT skills ( Lin, 2018 ). The CCTST is currently the most cited tool for measuring CT skills and includes analysis, assessment, deduction, inductive reasoning, and inference reasoning. The Chinese version included 34 multiple choice items. The dependent variable was the number of correctly answered items. The internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of the CCTST is 0.56 ( Jacobs, 1995 ). The test–retest reliability of CCTST-CV is 0.63 ( p < 0.01) ( Luo and Yang, 2002 ), and correlations between scores of the subscales and the total score are larger than 0.5 ( Lin, 2018 ), supporting the construct validity of the scale. In this study among the university students, the internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of the CCTST-CV was 0.5.

The second critical thinking test employed in this study was adapted from the belief bias paradigm ( Li et al., 2021 ). This task paradigm measures the ability to evaluate evidence and arguments independently of one's prior beliefs ( West et al., 2008 ), which is a strongly emphasized skill in CT literature. The current test included 20 syllogistic reasoning problems in which the logical conclusion was inconsistent with one's prior knowledge (e.g., “Premise 1: All fruits are sweet. Premise 2: Bananas are not sweet. Conclusion: Bananas are not fruits.” valid conclusion). In addition, four non-conflict items were included as the neutral condition in order to avoid a habitual response from the participants. They were instructed to suppose that all the premises are true and to decide whether the conclusion logically follows from the given premises. The measure showed good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.83) in a Chinese sample ( Li et al., 2021 ). In this study, the internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of the SRPBB was 0.94.

Measures of Critical Thinking Disposition

The Chinese Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory was employed to measure CT disposition ( Peng et al., 2004 ). This scale has been developed in line with the conceptual framework of the California critical thinking disposition inventory. We measured five CT dispositions: truth-seeking (one's objectivity with findings even if this requires changing one's preconceived opinions, e.g., a person inclined toward being truth-seeking might disagree with “I believe what I want to believe.”), inquisitiveness (one's intellectual curiosity. e.g., “No matter what the topic, I am eager to know more about it”), analyticity (the tendency to use reasoning and evidence to solve problems, e.g., “It bothers me when people rely on weak arguments to defend good ideas”), systematically (the disposition of being organized and orderly in inquiry, e.g., “I always focus on the question before I attempt to answer it”), and CT self-confidence (the trust one places in one's own reasoning processes, e.g., “I appreciate my ability to think precisely”). Each disposition aspect contained 10 items, which the participants rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale. This measure has shown high internal consistency (overall Cronbach's α = 0.9) ( Peng et al., 2004 ). In this study, the CCTDI scale was assessed at Cronbach's α = 0.89, indicating good reliability.

Measure of Impulsivity

The well-known Barrett Impulsivity Scale ( Patton et al., 1995 ) was employed to assess three facets of impulsivity: non-planning impulsivity (e.g., “I plan tasks carefully”); motor impulsivity (e.g., “I act on the spur of the moment”); attentional impulsivity (e.g., “I concentrate easily”). The scale includes 30 statements, and each statement is rated on a 5-point scale. The subscales of non-planning impulsivity and attentional impulsivity were reversely scored. The BIS-11 has good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.81, Velotti et al., 2016 ). This study showed that the Cronbach's α of the BIS-11 was 0.83.

Measures of Mental Health

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 was used to assess mental health problems such as depression (e.g., “I feel that life is meaningless”), anxiety (e.g., “I find myself getting agitated”), and stress (e.g., “I find it difficult to relax”). Each dimension included seven items, which the participants were asked to rate on a 4-point scale. The Chinese version of the DASS-21 has displayed a satisfactory factor structure and internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.92, Wang et al., 2016 ). In this study, the internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of the DASS-21 was 0.94.

The University Personality Inventory that has been commonly used to screen for mental problems of college students ( Yoshida et al., 1998 ) was also used for measuring mental health. The 56 symptom-items assessed whether an individual has experienced the described symptom during the past year (e.g., “a lack of interest in anything”). The UPI showed good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.92) in a Chinese sample ( Zhang et al., 2015 ). This study showed that the Cronbach's α of the UPI was 0.85.

Statistical Analyses

We first performed analyses to detect outliers. Any observation exceeding three standard deviations from the means was replaced with a value that was three standard deviations. This procedure affected no more than 5‰ of observations. Hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to determine the extent to which facets of critical thinking were related to mental health. In addition, structural equation modeling with Amos 22.0 was performed to assess the latent relationship between CT, impulsivity, and mental health.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

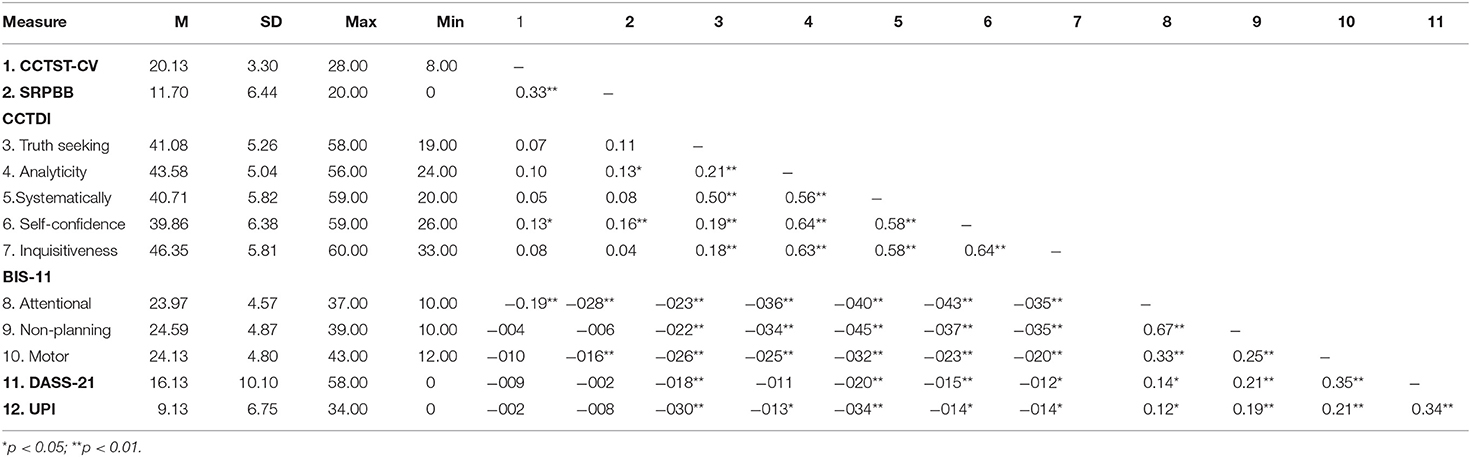

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of all the variables. CT disposition such as truth-seeking, systematicity, self-confidence, and inquisitiveness was significantly correlated with DASS-21 and UPI, but neither CCTST-CV nor SRPBB was related to DASS-21 and UPI. Subscales of BIS-11 were positively correlated with DASS-21 and UPI, but were negatively associated with CT dispositions.

Table 1 . Descriptive results and correlations between all measured variables ( N = 314).

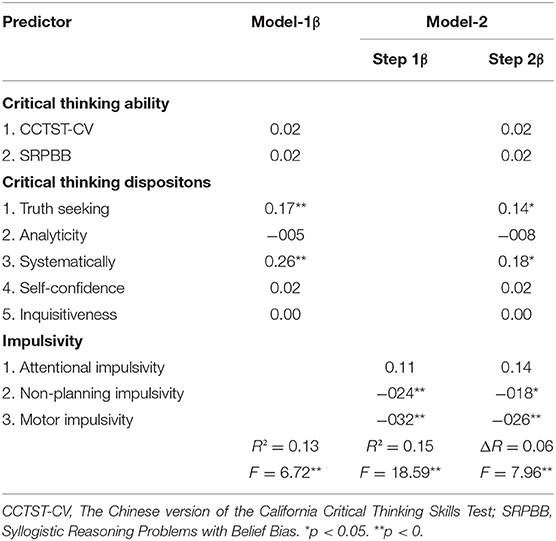

Regression Analyses

Hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to examine the effects of CT skill and disposition on mental health. Before conducting the analyses, scores in DASS-21 and UPI were reversed so that high scores reflected high levels of mental health. Table 2 presents the results of hierarchical regression. In model 1, the sum of the Z-score of DASS-21 and UPI served as the dependent variable. Scores in the CT ability tests and scores in the five dimensions of CCTDI served as predictors. CT skill and disposition explained 13% of the variance in mental health. CT skills did not significantly predict mental health. Two dimensions of dispositions (truth seeking and systematicity) exerted significantly positive effects on mental health. Model 2 examined whether CT predicted mental health after controlling for impulsivity. The model containing only impulsivity scores (see model-2 step 1 in Table 2 ) explained 15% of the variance in mental health. Non-planning impulsivity and motor impulsivity showed significantly negative effects on mental health. The CT variables on the second step explained a significantly unique variance (6%) of CT (see model-2 step 2). This suggests that CT skill and disposition together explained the unique variance in mental health after controlling for impulsivity. 1

Table 2 . Hierarchical regression models predicting mental health from critical thinking skills, critical thinking dispositions, and impulsivity ( N = 314).

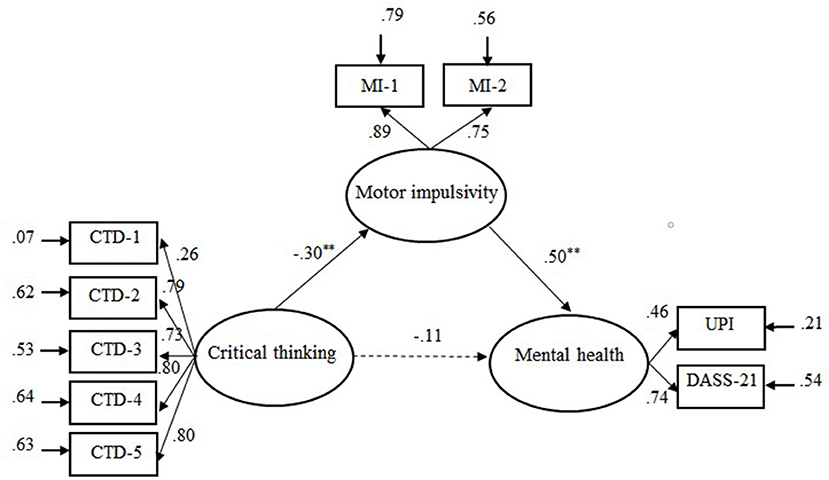

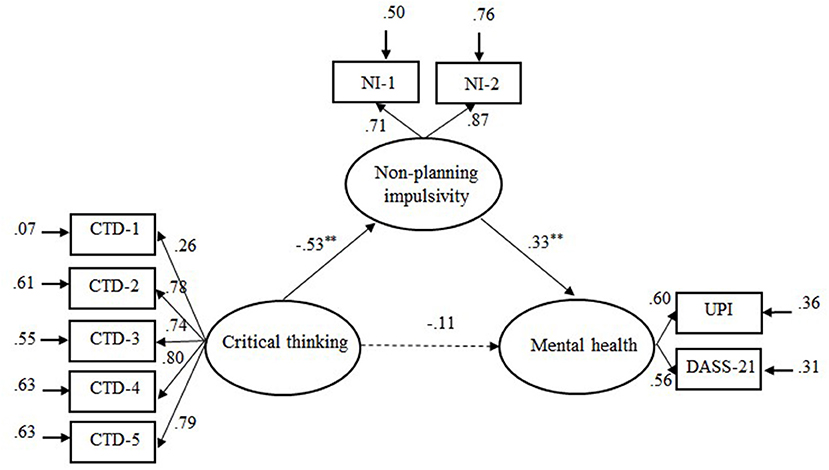

Structural equation modeling was performed to examine whether impulsivity mediated the relationship between CT disposition (CT ability was not included since it did not significantly predict mental health) and mental health. Since the regression results showed that only motor impulsivity and non-planning impulsivity significantly predicted mental health, we examined two mediation models with either motor impulsivity or non-planning impulsivity as the hypothesized mediator. The item scores in the motor impulsivity subscale were randomly divided into two indicators of motor impulsivity, as were the scores in the non-planning subscale. Scores of DASS-21 and UPI served as indicators of mental health and dimensions of CCTDI as indicators of CT disposition. In addition, a bootstrapping procedure with 5,000 resamples was established to test for direct and indirect effects. Amos 22.0 was used for the above analyses.

The mediation model that included motor impulsivity (see Figure 1 ) showed an acceptable fit, χ ( 23 ) 2 = 64.71, RMSEA = 0.076, CFI = 0.96, GFI = 0.96, NNFI = 0.93, SRMR = 0.073. Mediation analyses indicated that the 95% boot confidence intervals of the indirect effect and the direct effect were (0.07, 0.26) and (−0.08, 0.32), respectively. As Hayes (2009) indicates, an effect is significant if zero is not between the lower and upper bounds in the 95% confidence interval. Accordingly, the indirect effect between CT disposition and mental health was significant, while the direct effect was not significant. Thus, motor impulsivity completely mediated the relationship between CT disposition and mental health.

Figure 1 . Illustration of the mediation model: Motor impulsivity as mediator variable between critical thinking dispositions and mental health. CTD-l = Truth seeking; CTD-2 = Analyticity; CTD-3 = Systematically; CTD-4 = Self-confidence; CTD-5 = Inquisitiveness. MI-I and MI-2 were sub-scores of motor impulsivity. Solid line represents significant links and dotted line non-significant links. ** p < 0.01.

The mediation model, which included non-planning impulsivity (see Figure 2 ), also showed an acceptable fit to the data, χ ( 23 ) 2 = 52.75, RMSEA = 0.064, CFI = 0.97, GFI = 0.97, NNFI = 0.95, SRMR = 0.06. The 95% boot confidence intervals of the indirect effect and the direct effect were (0.05, 0.33) and (−0.04, 0.38), respectively, indicating that non-planning impulsivity completely mediated the relationship between CT disposition and mental health.

Figure 2 . Illustration of the mediation model: Non-planning impulsivity asmediator variable between critical thinking dispositions and mental health. CTD-l = Truth seeking; CTD-2 = Analyticity; CTD-3 = Systematically; CTD-4 = Self-confidence; CTD-5 = Inquisitiveness. NI-I and NI-2 were sub-scores of Non-planning impulsivity. Solid line represents significant links and dotted line non-significant links. ** p < 0.01.

This study examined how critical thinking skill and disposition are related to mental health. Theories of psychotherapy suggest that human mental problems are in part due to a lack of CT. However, empirical evidence for the hypothesized relationship between CT and mental health is relatively scarce. This study explored whether and how CT ability and disposition are associated with mental health. The results, based on a university student sample, indicated that CT skill and disposition explained a unique variance in mental health. Furthermore, the effect of CT disposition on mental health was mediated by motor impulsivity and non-planning impulsivity. The finding that CT exerted a significant effect on mental health was in accordance with previous studies reporting negative correlations between CT disposition and mental disorders such as anxiety ( Suliman and Halabi, 2007 ). One reason lies in the assumption that CT disposition is usually referred to as personality traits or habits of mind that are a remarkable predictor of mental health (e.g., Benzi et al., 2019 ). This study further found that of the five CT dispositions, only truth-seeking and systematicity were associated with individual differences in mental health. This was not surprising, since the truth-seeking items mainly assess one's inclination to crave for the best knowledge in a given context and to reflect more about additional facts, reasons, or opinions, even if this requires changing one's mind about certain issues. The systematicity items target one's disposition to approach problems in an orderly and focused way. Individuals with high levels of truth-seeking and systematicity are more likely to adopt a comprehensive, reflective, and controlled way of thinking, which is what cognitive therapy aims to achieve by shifting from an automatic mode of processing to a more reflective and controlled mode.

Another important finding was that motor impulsivity and non-planning impulsivity mediated the effect of CT disposition on mental health. The reason may be that people lacking CT have less willingness to enter into a systematically analyzing process or deliberative decision-making process, resulting in more frequently rash behaviors or unplanned actions without regard for consequences ( Billieux et al., 2010 ; Franco et al., 2017 ). Such responses can potentially have tangible negative consequences (e.g., conflict, aggression, addiction) that may lead to social maladjustment that is regarded as a symptom of mental illness. On the contrary, critical thinkers have a sense of deliberativeness and consider alternate consequences before acting, and this thinking-before-acting mode would logically lead to a decrease in impulsivity, which then decreases the likelihood of problematic behaviors and negative moods.

It should be noted that although the raw correlation between attentional impulsivity and mental health was significant, regression analyses with the three dimensions of impulsivity as predictors showed that attentional impulsivity no longer exerted a significant effect on mental effect after controlling for the other impulsivity dimensions. The insignificance of this effect suggests that the significant raw correlation between attentional impulsivity and mental health was due to the variance it shared with the other impulsivity dimensions (especially with the non-planning dimension, which showed a moderately high correlation with attentional impulsivity, r = 0.67).

Some limitations of this study need to be mentioned. First, the sample involved in this study is considered as a limited sample pool, since all the participants are university students enrolled in statistics and mathematical finance, limiting the generalization of the findings. Future studies are recommended to recruit a more representative sample of university students. A study on generalization to a clinical sample is also recommended. Second, as this study was cross-sectional in nature, caution must be taken in interpreting the findings as causal. Further studies using longitudinal, controlled designs are needed to assess the effectiveness of CT intervention on mental health.

In spite of the limitations mentioned above, the findings of this study have some implications for research and practice intervention. The result that CT contributed to individual differences in mental health provides empirical support for the theory of cognitive behavioral therapy, which focuses on changing irrational thoughts. The mediating role of impulsivity between CT and mental health gives a preliminary account of the mechanism of how CT is associated with mental health. Practically, although there is evidence that CT disposition of students improves because of teaching or training interventions (e.g., Profetto-Mcgrath, 2005 ; Sanja and Krstivoje, 2015 ; Chan, 2019 ), the results showing that two CT disposition dimensions, namely, truth-seeking and systematicity, are related to mental health further suggest that special attention should be paid to cultivating these specific CT dispositions so as to enhance the control of students over impulsive behaviors in their mental health promotions.

Conclusions

This study revealed that two CT dispositions, truth-seeking and systematicity, were associated with individual differences in mental health. Furthermore, the relationship between critical thinking and mental health was mediated by motor impulsivity and non-planning impulsivity. These findings provide a preliminary account of how human critical thinking is associated with mental health. Practically, developing mental health promotion programs for university students is suggested to pay special attention to cultivating their critical thinking dispositions (especially truth-seeking and systematicity) and enhancing the control of individuals over impulsive behaviors.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by HUST Critical Thinking Research Center (Grant No. 2018CT012). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

XR designed the study and revised the manuscript. ZL collected data and wrote the manuscript. SL assisted in analyzing the data. SS assisted in re-drafting and editing the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the Social Science Foundation of China (grant number: BBA200034).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^ We re-analyzed the data by controlling for age and gender of the participants in the regression analyses. The results were virtually the same as those reported in the study.

Barry, A., Parvan, K., Sarbakhsh, P., Safa, B., and Allahbakhshian, A. (2020). Critical thinking in nursing students and its relationship with professional self-concept and relevant factors. Res. Dev. Med. Educ. 9, 7–7. doi: 10.34172/rdme.2020.007

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Benzi, I. M. A., Emanuele, P., Rossella, D. P., Clarkin, J. F., and Fabio, M. (2019). Maladaptive personality traits and psychological distress in adolescence: the moderating role of personality functioning. Pers. Indiv. Diff. 140, 33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.06.026

Billieux, J., Gay, P., Rochat, L., and Van der Linden, M. (2010). The role of urgency and its underlying psychological mechanisms in problematic behaviours. Behav. Res. Ther. 48, 1085–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.07.008

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Butler, H. A., Pentoney, C., and Bong, M. P. (2017). Predicting real-world outcomes: Critical thinking ability is a better predictor of life decisions than intelligence. Think. Skills Creat. 25, 38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2017.06.005

Chan, C. (2019). Using digital storytelling to facilitate critical thinking disposition in youth civic engagement: a randomized control trial. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 107:104522. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104522

Chen, M. R. A., and Hwang, G. J. (2020). Effects of a concept mapping-based flipped learning approach on EFL students' English speaking performance, critical thinking awareness and speaking anxiety. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 51, 817–834. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12887

Cuijpers, P. (2019). Targets and outcomes of psychotherapies for mental disorders: anoverview. World Psychiatry. 18, 276–285. doi: 10.1002/wps.20661

Duffy, M. E., Twenge, J. M., and Joiner, T. E. (2019). Trends in mood and anxiety symptoms and suicide-related outcomes among u.s. undergraduates, 2007–2018: evidence from two national surveys. J. Adolesc. Health. 65, 590–598. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.04.033

Dwyer, C. P. (2017). Critical Thinking: Conceptual Perspectives and Practical Guidelines . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Google Scholar

Facione, P. A. (1990). Critical Thinking: Astatement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction . Millibrae, CA: The California Academic Press.

Fortgang, R. G., Hultman, C. M., van Erp, T. G. M., and Cannon, T. D. (2016). Multidimensional assessment of impulsivity in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder: testing for shared endophenotypes. Psychol. Med. 46, 1497–1507. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716000131

Franco, A. R., Costa, P. S., Butler, H. A., and Almeida, L. S. (2017). Assessment of undergraduates' real-world outcomes of critical thinking in everyday situations. Psychol. Rep. 120, 707–720. doi: 10.1177/0033294117701906

Gambrill, E. (2005). “Critical thinking, evidence-based practice, and mental health,” in Mental Disorders in the Social Environment: Critical Perspectives , ed S. A. Kirk (New York, NY: Columbia University Press), 247–269.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Ghanizadeh, A. (2017). The interplay between reflective thinking, critical thinking, self-monitoring, and academic achievement in higher education. Higher Educ. 74. 101–114. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-0031-y

Gilbert, T. (2003). Some reflections on critical thinking and mental health. Teach. Phil. 24, 333–339. doi: 10.5840/teachphil200326446

Gregory, R. (1991). Critical thinking for environmental health risk education. Health Educ. Q. 18, 273–284. doi: 10.1177/109019819101800302

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the newmillennium. Commun. Monogr. 76, 408–420. doi: 10.1080/03637750903310360

Hollon, S. D., and Beck, A. T. (2013). “Cognitive and cognitive-behavioral therapies,” in Bergin and Garfield's Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, Vol. 6 . ed M. J. Lambert (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley), 393–442.

Hong, L., Lin, C. D., Bray, M. A., and Kehle, T. J. (2010). The measurement of stressful events in chinese college students. Psychol. Sch. 42, 315–323. doi: 10.1002/pits.20082

CrossRef Full Text

Jacobs, S. S. (1995). Technical characteristics and some correlates of the california critical thinking skills test, forms a and b. Res. Higher Educ. 36, 89–108.

Kargar, F. R., Ajilchi, B., Goreyshi, M. K., and Noohi, S. (2013). Effect of creative and critical thinking skills teaching on identity styles and general health in adolescents. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 84, 464–469. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.585

Leclair, M. C., Lemieux, A. J., Roy, L., Martin, M. S., Latimer, E. A., and Crocker, A. G. (2020). Pathways to recovery among homeless people with mental illness: Is impulsiveness getting in the way? Can. J. Psychiatry. 65, 473–483. doi: 10.1177/0706743719885477

Lee, H. S., Kim, S., Choi, I., and Lee, K. U. (2008). Prevalence and risk factors associated with suicide ideation and attempts in korean college students. Psychiatry Investig. 5, 86–93. doi: 10.4306/pi.2008.5.2.86

Li, S., Ren, X., Schweizer, K., Brinthaupt, T. M., and Wang, T. (2021). Executive functions as predictors of critical thinking: behavioral and neural evidence. Learn. Instruct. 71:101376. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2020.101376

Lin, Y. (2018). Developing Critical Thinking in EFL Classes: An Infusion Approach . Singapore: Springer Publications.

Luo, Q. X., and Yang, X. H. (2002). Revising on Chinese version of California critical thinkingskillstest. Psychol. Sci. (Chinese). 25, 740–741.

Mamun, M. A., Misti, J. M., Hosen, I., and Mamun, F. A. (2021). Suicidal behaviors and university entrance test-related factors: a bangladeshi exploratory study. Persp. Psychiatric Care. 4, 1–10. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12783

Patton, J. H., Stanford, M. S., and Barratt, E. S. (1995). Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin. Psychol. 51, 768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:63.0.CO;2-1

Peng, M. C., Wang, G. C., Chen, J. L., Chen, M. H., Bai, H. H., Li, S. G., et al. (2004). Validity and reliability of the Chinese critical thinking disposition inventory. J. Nurs. China (Zhong Hua Hu Li Za Zhi). 39, 644–647.

Profetto-Mcgrath, J. (2005). Critical thinking and evidence-based practice. J. Prof. Nurs. 21, 364–371. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2005.10.002

Ren, X., Tong, Y., Peng, P., and Wang, T. (2020). Critical thinking predicts academic performance beyond general cognitive ability: evidence from adults and children. Intelligence 82:101487. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2020.101487

Sanja, M., and Krstivoje, S. (2015). Developing critical thinking in elementary mathematics education through a suitable selection of content and overall student performance. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 180, 653–659. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.02.174

Stupple, E., Maratos, F. A., Elander, J., Hunt, T. E., and Aubeeluck, A. V. (2017). Development of the critical thinking toolkit (critt): a measure of student attitudes and beliefs about critical thinking. Think. Skills Creat. 23, 91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2016.11.007

Suliman, W. A., and Halabi, J. (2007). Critical thinking, self-esteem, and state anxiety of nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today. 27, 162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2006.04.008

Ugwuozor, F. O., Otu, M. S., and Mbaji, I. N. (2021). Critical thinking intervention for stress reduction among undergraduates in the Nigerian Universities. Medicine 100:25030. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000025030

Velotti, P., Garofalo, C., Petrocchi, C., Cavallo, F., Popolo, R., and Dimaggio, G. (2016). Alexithymia, emotion dysregulation, impulsivity and aggression: a multiple mediation model. Psychiatry Res. 237, 296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.01.025

Wang, K., Shi, H. S., Geng, F. L., Zou, L. Q., Tan, S. P., Wang, Y., et al. (2016). Cross-cultural validation of the depression anxiety stress scale−21 in China. Psychol. Assess. 28:e88. doi: 10.1037/pas0000207

West, R. F., Toplak, M. E., and Stanovich, K. E. (2008). Heuristics and biases as measures of critical thinking: associations with cognitive ability and thinking dispositions. J. Educ. Psychol. 100, 930–941. doi: 10.1037/a0012842

Yoshida, T., Ichikawa, T., Ishikawa, T., and Hori, M. (1998). Mental health of visually and hearing impaired students from the viewpoint of the University Personality Inventory. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 52, 413–418.

Yoshinori, S., and Marcus, G. (2013). The dual effects of critical thinking disposition on worry. PLoS ONE 8:e79714. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.007971

Zhang, J., Lanza, S., Zhang, M., and Su, B. (2015). Structure of the University personality inventory for chinese college students. Psychol. Rep. 116, 821–839. doi: 10.2466/08.02.PR0.116k26w3

Keywords: mental health, critical thinking ability, critical thinking disposition, impulsivity, depression

Citation: Liu Z, Li S, Shang S and Ren X (2021) How Do Critical Thinking Ability and Critical Thinking Disposition Relate to the Mental Health of University Students? Front. Psychol. 12:704229. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.704229

Received: 04 May 2021; Accepted: 21 July 2021; Published: 19 August 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Liu, Li, Shang and Ren. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xuezhu Ren, renxz@hust.edu.cn

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 06 January 2021

Psychometric properties of the critical thinking disposition assessment test amongst medical students in China: a cross-sectional study

- Liyuan Cui 1 , 2 ,

- Yaxin Zhu 1 ,

- Jinglou Qu 1 , 3 ,

- Liming Tie 1 , 4 ,

- Ziqi Wang 1 &

- Bo Qu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2526-9690 1

BMC Medical Education volume 21 , Article number: 10 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

4934 Accesses

23 Citations

Metrics details

Critical thinking disposition helps medical students and professionals overcome the effects of personal values and beliefs when exercising clinical judgment. The lack of effective instruments to measure critical thinking disposition in medical students has become an obstacle for training and evaluating students in undergraduate programs in China. The aim of this study was to evaluate the psychometric properties of the CTDA test.

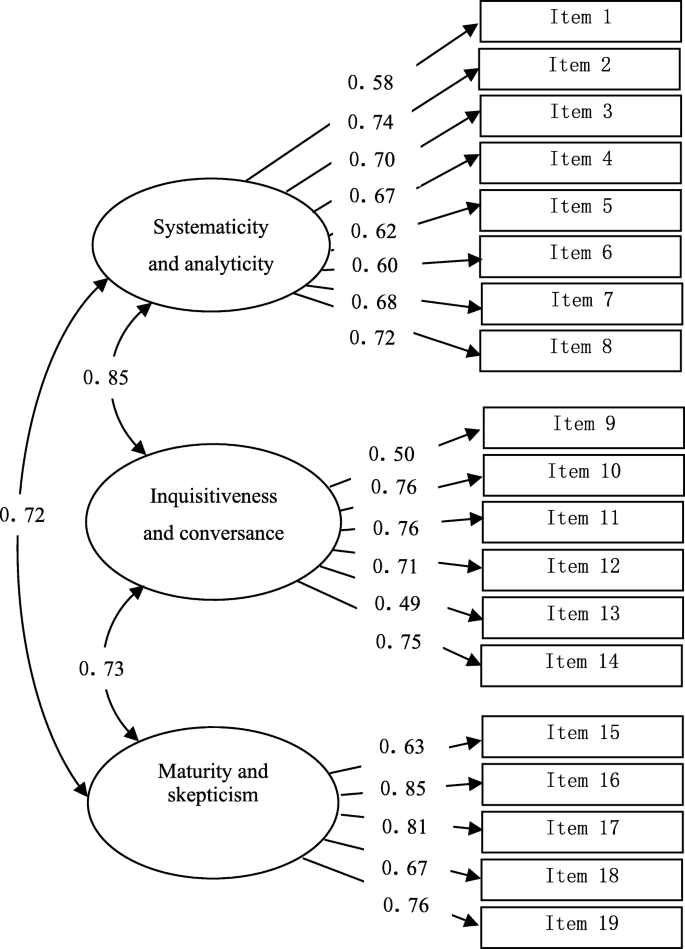

A total of 278 students participated in this study and responded to the CTDA test. Cronbach’s α coefficient, internal consistency, test-retest reliability, floor effects and ceiling effects were measured to assess the reliability of the questionnaire. Construct validity of the pre-specified three-domain structure of the CTDA was evaluated by explanatory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The convergent validity and discriminant validity were also analyzed.

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the entire questionnaire was calculated to be 0.92, all of the domains showed acceptable internal consistency (0.81–0.86), and the test-retest reliability indicated acceptable intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) (0.93, p < 0.01). The EFA and the CFA demonstrated that the three-domain model fitted the data adequately. The test showed satisfactory convergent and discriminant validity.

Conclusions

The CTDA is a reliable and valid questionnaire to evaluate the disposition of medical students towards critical thinking in China and can reasonably be applied in critical thinking programs and medical education research.

Peer Review reports

For decades, the importance of developing critical thinking skills has been emphasized in medical education [ 1 ]. As listed by the World Federation for Medical Education, critical thinking should be part of the training standards for medical students and practitioners [ 2 ]. Critical thinking is essential for medical students and professionals to be able to evaluate, diagnose and treat patients effectively [ 3 ]. One major criticism of medical education is the gap that exists between what students learn in the classroom setting and what they experience in clinical practice [ 4 ]. Only a few students will analyze and employ critical thinking when they acquire knowledge during their education [ 5 ]. Therefore, critical thinking has become increasingly necessary for medical students and professionals [ 6 ].

Critical thinking is an indispensable component of ethical reasoning and clinical judgment, and possessing reasonable critical thinking abilities reduces the risk of clinical errors [ 7 ]. Adverse events that occur by human error and preventable medical errors were frequently caused by a failure of cognitive function (e.g., failure to synthesize and/or take action based on information), which was second only to ‘failure in technical operation of an indicated procedure’ [ 8 , 9 ]. Similar problems have been reported in several countries such as the United Kingdom, Canada and Denmark [ 10 ]. Therefore, medical professionals need to exercise critical thinking, transcend simple issues, and make sound judgments in order to handle adverse medical situations [ 11 ]. Providing evidence and logical arguments to medical students and professionals is beneficial in order to support clinical decision-making and assertions [ 12 ]. Lipman and Deatrick are of the same opinion; i.e., critical thinking is a prerequisite for sound clinical decision-making [ 13 ]. Therefore, medical students should be exposed to clinical learning experiences that promote the acquisition of critical thinking abilities that are needed to provide quality care for patients in modern complex healthcare environments [ 14 ].

Currently, critical thinking is defined as a kind of reasonable reflective thinking following the synthesis of cognitive abilities and disposition [ 15 ]. The former includes interpretation, deduction, induction, evaluation and inference, whereas the latter includes having an open mind and being intellectually honest [ 16 ]. The critical thinking disposition (CTD) was described as seven attributes including, truth-seeking, open-mindness, analyticity, systematicity, critical thinking self-confidence, inquisitiveness and maturity [ 17 ]. A disposition to critical thinking is essential for professional clinical judgement [ 18 ]. An assessment of the CTD in professional judgment circumstances and educational contexts can establish benchmarks to advance critical thinking through training programs [ 4 ].

To investigate and assess the CTD in medical students, a reliable and valid tool is indispensable. Several CTD measurement tools are available, such as the California Critical Thinking Dispositions Inventory (CCTDI), Yoon’s Critical Thinking Disposition (YCTD) and the Critical Thinking Disposition Assessment (CTDA). The CCTDI was developed to evaluate the CTD in normal adults. It had good reliability and validity in western cultures, however, it had low reliability and validity for Chinese nursing students in previous studies [ 19 , 20 ]. Yoon created the YCTD, which was based on the CCTDI, for nursing students in South Korea [ 21 ]. According to the literature review and other measures of critical thinking disposition, Yuan developed the CTDA in English version. They used it to measure the CTD for medical students and professionals. In his study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the entire assessment was 0.94 [ 22 ]. The CTD for the CTDA were defined as “systematicity and analyticity”, “inquisitiveness and conversance” and “maturity and skepticism”. The “systematicity and analyticity” portion is the cognitive component of the CTD and measured the tendency towards organizing and applying evidence to address problems. Being systematical and analytical allow medical students to connect clinical observations with their knowledge to anticipate events that are likely to threaten the patient’s safety [ 23 ]. The “inquisitiveness and conversance” is the motivation component of the CTD. It measures the desire of medical students for learning whenever the application of the knowledge is inconclusive and is essential for medical students to expand their knowledge in clinical practice [ 24 ]. The “maturity and skepticism” is the personality component of the CTD which measured the disposition to be judicious in decision making and how often it leads to reflective skepticism. This disposition has particular implications for ethical decision making, particularly in time-pressured clinical situations [ 25 ]. All the domains have a tight connection to one another. In adapting to the Chinese version, we followed the translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the guidelines set forth by the WHO [ 26 ]. The steps listed by the WHO are as follows: forward translation, expert panel review, back translation, pretest and cognitive interviews, and formulation of the final version. As such, the CTDA may be especially valuable for institutes or universities in Asian countries or with an Eastern culture for assessing critical thinking disposition in medical students. Given the lack of effective instruments to assess the CTD in undergraduate medical programs in mainland China, the objective of this investigation was to evaluate the psychometric properties of the CTDA.

Sample sizes

According to Kline’s recommendation, it is necessary to note that the sample size should base on the principle of a 1:10 item to participant ratio [ 27 ]. The total number of items in the CDTA is nineteen and so the sample size should be at least 190 students. Therefore, using this guideline, with a sample size of 300 students, this research exceeds the recommended minimum.

Participants and procedures