Search form

- About Faculty Development and Support

- Programs and Funding Opportunities

Consultations, Observations, and Services

- Strategic Resources & Digital Publications

- Canvas @ Yale Support

- Learning Environments @ Yale

- Teaching Workshops

- Teaching Consultations and Classroom Observations

- Teaching Programs

- Spring Teaching Forum

- Written and Oral Communication Workshops and Panels

- Writing Resources & Tutorials

- About the Graduate Writing Laboratory

- Writing and Public Speaking Consultations

- Writing Workshops and Panels

- Writing Peer-Review Groups

- Writing Retreats and All Writes

- Online Writing Resources for Graduate Students

- About Teaching Development for Graduate and Professional School Students

- Teaching Programs and Grants

- Teaching Forums

- Resources for Graduate Student Teachers

- About Undergraduate Writing and Tutoring

- Academic Strategies Program

- The Writing Center

- STEM Tutoring & Programs

- Humanities & Social Sciences

- Center for Language Study

- Online Course Catalog

- Antiracist Pedagogy

- NECQL 2019: NorthEast Consortium for Quantitative Literacy XXII Meeting

- STEMinar Series

- Teaching in Context: Troubling Times

- Helmsley Postdoctoral Teaching Scholars

- Pedagogical Partners

- Instructional Materials

- Evaluation & Research

- STEM Education Job Opportunities

- Yale Connect

- Online Education Legal Statements

You are here

Case-based learning.

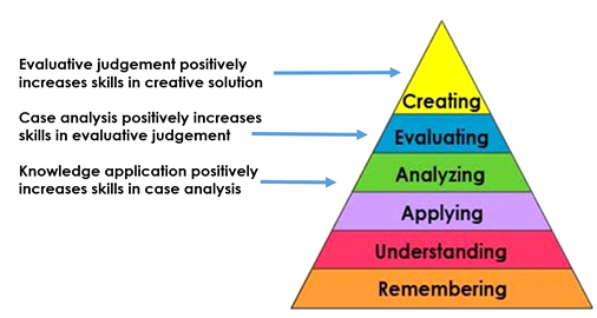

Case-based learning (CBL) is an established approach used across disciplines where students apply their knowledge to real-world scenarios, promoting higher levels of cognition (see Bloom’s Taxonomy ). In CBL classrooms, students typically work in groups on case studies, stories involving one or more characters and/or scenarios. The cases present a disciplinary problem or problems for which students devise solutions under the guidance of the instructor. CBL has a strong history of successful implementation in medical, law, and business schools, and is increasingly used within undergraduate education, particularly within pre-professional majors and the sciences (Herreid, 1994). This method involves guided inquiry and is grounded in constructivism whereby students form new meanings by interacting with their knowledge and the environment (Lee, 2012).

There are a number of benefits to using CBL in the classroom. In a review of the literature, Williams (2005) describes how CBL: utilizes collaborative learning, facilitates the integration of learning, develops students’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation to learn, encourages learner self-reflection and critical reflection, allows for scientific inquiry, integrates knowledge and practice, and supports the development of a variety of learning skills.

CBL has several defining characteristics, including versatility, storytelling power, and efficient self-guided learning. In a systematic analysis of 104 articles in health professions education, CBL was found to be utilized in courses with less than 50 to over 1000 students (Thistlethwaite et al., 2012). In these classrooms, group sizes ranged from 1 to 30, with most consisting of 2 to 15 students. Instructors varied in the proportion of time they implemented CBL in the classroom, ranging from one case spanning two hours of classroom time, to year-long case-based courses. These findings demonstrate that instructors use CBL in a variety of ways in their classrooms.

The stories that comprise the framework of case studies are also a key component to CBL’s effectiveness. Jonassen and Hernandez-Serrano (2002, p.66) describe how storytelling:

Is a method of negotiating and renegotiating meanings that allows us to enter into other’s realms of meaning through messages they utter in their stories,

Helps us find our place in a culture,

Allows us to explicate and to interpret, and

Facilitates the attainment of vicarious experience by helping us to distinguish the positive models to emulate from the negative model.

Neurochemically, listening to stories can activate oxytocin, a hormone that increases one’s sensitivity to social cues, resulting in more empathy, generosity, compassion and trustworthiness (Zak, 2013; Kosfeld et al., 2005). The stories within case studies serve as a means by which learners form new understandings through characters and/or scenarios.

CBL is often described in conjunction or in comparison with problem-based learning (PBL). While the lines are often confusingly blurred within the literature, in the most conservative of definitions, the features distinguishing the two approaches include that PBL involves open rather than guided inquiry, is less structured, and the instructor plays a more passive role. In PBL multiple solutions to the problem may exit, but the problem is often initially not well-defined. PBL also has a stronger emphasis on developing self-directed learning. The choice between implementing CBL versus PBL is highly dependent on the goals and context of the instruction. For example, in a comparison of PBL and CBL approaches during a curricular shift at two medical schools, students and faculty preferred CBL to PBL (Srinivasan et al., 2007). Students perceived CBL to be a more efficient process and more clinically applicable. However, in another context, PBL might be the favored approach.

In a review of the effectiveness of CBL in health profession education, Thistlethwaite et al. (2012), found several benefits:

Students enjoyed the method and thought it enhanced their learning,

Instructors liked how CBL engaged students in learning,

CBL seemed to facilitate small group learning, but the authors could not distinguish between whether it was the case itself or the small group learning that occurred as facilitated by the case.

Other studies have also reported on the effectiveness of CBL in achieving learning outcomes (Bonney, 2015; Breslin, 2008; Herreid, 2013; Krain, 2016). These findings suggest that CBL is a vehicle of engagement for instruction, and facilitates an environment whereby students can construct knowledge.

Science – Students are given a scenario to which they apply their basic science knowledge and problem-solving skills to help them solve the case. One example within the biological sciences is two brothers who have a family history of a genetic illness. They each have mutations within a particular sequence in their DNA. Students work through the case and draw conclusions about the biological impacts of these mutations using basic science. Sample cases: You are Not the Mother of Your Children ; Organic Chemisty and Your Cellphone: Organic Light-Emitting Diodes ; A Light on Physics: F-Number and Exposure Time

Medicine – Medical or pre-health students read about a patient presenting with specific symptoms. Students decide which questions are important to ask the patient in their medical history, how long they have experienced such symptoms, etc. The case unfolds and students use clinical reasoning, propose relevant tests, develop a differential diagnoses and a plan of treatment. Sample cases: The Case of the Crying Baby: Surgical vs. Medical Management ; The Plan: Ethics and Physician Assisted Suicide ; The Haemophilus Vaccine: A Victory for Immunologic Engineering

Public Health – A case study describes a pandemic of a deadly infectious disease. Students work through the case to identify Patient Zero, the person who was the first to spread the disease, and how that individual became infected. Sample cases: The Protective Parent ; The Elusive Tuberculosis Case: The CDC and Andrew Speaker ; Credible Voice: WHO-Beijing and the SARS Crisis

Law – A case study presents a legal dilemma for which students use problem solving to decide the best way to advise and defend a client. Students are presented information that changes during the case. Sample cases: Mortgage Crisis Call (abstract) ; The Case of the Unpaid Interns (abstract) ; Police-Community Dialogue (abstract)

Business – Students work on a case study that presents the history of a business success or failure. They apply business principles learned in the classroom and assess why the venture was successful or not. Sample cases: SELCO-Determining a path forward ; Project Masiluleke: Texting and Testing to Fight HIV/AIDS in South Africa ; Mayo Clinic: Design Thinking in Healthcare

Humanities - Students consider a case that presents a theater facing financial and management difficulties. They apply business and theater principles learned in the classroom to the case, working together to create solutions for the theater. Sample cases: David Geffen School of Drama

Recommendations

Finding and Writing Cases

Consider utilizing or adapting open access cases - The availability of open resources and databases containing cases that instructors can download makes this approach even more accessible in the classroom. Two examples of open databases are the Case Center on Public Leadership and Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Case Program , which focus on government, leadership and public policy case studies.

- Consider writing original cases - In the event that an instructor is unable to find open access cases relevant to their course learning objectives, they may choose to write their own. See the following resources on case writing: Cooking with Betty Crocker: A Recipe for Case Writing ; The Way of Flesch: The Art of Writing Readable Cases ; Twixt Fact and Fiction: A Case Writer’s Dilemma ; And All That Jazz: An Essay Extolling the Virtues of Writing Case Teaching Notes .

Implementing Cases

Take baby steps if new to CBL - While entire courses and curricula may involve case-based learning, instructors who desire to implement on a smaller-scale can integrate a single case into their class, and increase the number of cases utilized over time as desired.

Use cases in classes that are small, medium or large - Cases can be scaled to any course size. In large classes with stadium seating, students can work with peers nearby, while in small classes with more flexible seating arrangements, teams can move their chairs closer together. CBL can introduce more noise (and energy) in the classroom to which an instructor often quickly becomes accustomed. Further, students can be asked to work on cases outside of class, and wrap up discussion during the next class meeting.

Encourage collaborative work - Cases present an opportunity for students to work together to solve cases which the historical literature supports as beneficial to student learning (Bruffee, 1993). Allow students to work in groups to answer case questions.

Form diverse teams as feasible - When students work within diverse teams they can be exposed to a variety of perspectives that can help them solve the case. Depending on the context of the course, priorities, and the background information gathered about the students enrolled in the class, instructors may choose to organize student groups to allow for diversity in factors such as current course grades, gender, race/ethnicity, personality, among other items.

Use stable teams as appropriate - If CBL is a large component of the course, a research-supported practice is to keep teams together long enough to go through the stages of group development: forming, storming, norming, performing and adjourning (Tuckman, 1965).

Walk around to guide groups - In CBL instructors serve as facilitators of student learning. Walking around allows the instructor to monitor student progress as well as identify and support any groups that may be struggling. Teaching assistants can also play a valuable role in supporting groups.

Interrupt strategically - Only every so often, for conversation in large group discussion of the case, especially when students appear confused on key concepts. An effective practice to help students meet case learning goals is to guide them as a whole group when the class is ready. This may include selecting a few student groups to present answers to discussion questions to the entire class, asking the class a question relevant to the case using polling software, and/or performing a mini-lesson on an area that appears to be confusing among students.

Assess student learning in multiple ways - Students can be assessed informally by asking groups to report back answers to various case questions. This practice also helps students stay on task, and keeps them accountable. Cases can also be included on exams using related scenarios where students are asked to apply their knowledge.

Barrows HS. (1996). Problem-based learning in medicine and beyond: a brief overview. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 68, 3-12.

Bonney KM. (2015). Case Study Teaching Method Improves Student Performance and Perceptions of Learning Gains. Journal of Microbiology and Biology Education, 16(1): 21-28.

Breslin M, Buchanan, R. (2008) On the Case Study Method of Research and Teaching in Design. Design Issues, 24(1), 36-40.

Bruffee KS. (1993). Collaborative learning: Higher education, interdependence, and authority of knowledge. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD.

Herreid CF. (2013). Start with a Story: The Case Study Method of Teaching College Science, edited by Clyde Freeman Herreid. Originally published in 2006 by the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA); reprinted by the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science (NCCSTS) in 2013.

Herreid CH. (1994). Case studies in science: A novel method of science education. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 23(4), 221–229.

Jonassen DH and Hernandez-Serrano J. (2002). Case-based reasoning and instructional design: Using stories to support problem solving. Educational Technology, Research and Development, 50(2), 65-77.

Kosfeld M, Heinrichs M, Zak PJ, Fischbacher U, Fehr E. (2005). Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature, 435, 673-676.

Krain M. (2016) Putting the learning in case learning? The effects of case-based approaches on student knowledge, attitudes, and engagement. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 27(2), 131-153.

Lee V. (2012). What is Inquiry-Guided Learning? New Directions for Learning, 129:5-14.

Nkhoma M, Sriratanaviriyakul N. (2017). Using case method to enrich students’ learning outcomes. Active Learning in Higher Education, 18(1):37-50.

Srinivasan et al. (2007). Comparing problem-based learning with case-based learning: Effects of a major curricular shift at two institutions. Academic Medicine, 82(1): 74-82.

Thistlethwaite JE et al. (2012). The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education. A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 23. Medical Teacher, 34, e421-e444.

Tuckman B. (1965). Development sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63(6), 384-99.

Williams B. (2005). Case-based learning - a review of the literature: is there scope for this educational paradigm in prehospital education? Emerg Med, 22, 577-581.

Zak, PJ (2013). How Stories Change the Brain. Retrieved from: https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_stories_change_brain

YOU MAY BE INTERESTED IN

The Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning routinely supports members of the Yale community with individual instructional consultations and classroom observations.

Instructional Enhancement Fund

The Instructional Enhancement Fund (IEF) awards grants of up to $500 to support the timely integration of new learning activities into an existing undergraduate or graduate course. All Yale instructors of record, including tenured and tenure-track faculty, clinical instructional faculty, lecturers, lectors, and part-time acting instructors (PTAIs), are eligible to apply. Award decisions are typically provided within two weeks to help instructors implement ideas for the current semester.

Reserve a Room

The Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning partners with departments and groups on-campus throughout the year to share its space. Please review the reservation form and submit a request.

- Hispanoamérica

- Work at ArchDaily

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Mixed Use Architecture

Sarnsara Learning Center / Architects 49

- Curated by Hana Abdel

- Architects: Architects 49

- Area Area of this architecture project Area: 16568 m²

- Year Completion year of this architecture project Year: 2020

- Photographs Photographs: Nattakit Jeerapatmaitree

- Lead Architects: Prabhakorn Vadanyakul, Somkiat Lo-Chindapong

- Interior Architects : PIA interior

- Structural Engineer : Architectural Engineering 49

- Landscape : Landscape Architects 49

- Lighting Designer : 49 Lighting Design Consultants

- Client: Muang Thai Life Assurance

- Awards: LEED V4 Gold® (LEED® BD+C: New Construction): 2020

- System Engineer: M&E Engineering 49

- City: Ban Pong

- Country: Thailand

Text description provided by the architects. Muang Thai Life Assurance’s core values, “The M Powered C: Customer Centric, Creativity, Commitment to Success, Collaboration and Caring,” were integrated into the design of the Sarnsara Learning Center, in Ratchaburi province. This training center was established in a natural setting to nurture an understanding of the company’s objectives and the importance of its representatives maintaining close client relationships.

In the spirit of their collaborative culture, the center’s design encourages interaction and the exchange of ideas between users. Spaces for discussions and casual meetings, facilitate the company’s belief that new products can originate from any individual in the organization. To this end, the complex is designed to provide various adaptive spaces that encourage innovation.

A triangle modular configuration is used to enable the users to create an array of rooms to suit a variety of purposes from seminars, meetings, group discussions, workshops or other activities, reflecting the company’s customer centric values. This triangular module is also applied to spaces for outdoor activities. In line with this triangular theme, the shape is also applied to the ceiling systems for semi-outdoor spaces to filter natural light from the skylight to meet the needs of each activity. Combined with the company’s color branding, the resulting atmosphere can be likened to sitting in the shade of a fuchsia tree.

An oval-shaped auditorium, reflects and promotes the idea of a happy community, and the overall atmosphere creates a collaborative working culture. Facilities include a 1,000-seat auditorium, training rooms that can accommodate from 20 to 200 people, and 73 guestrooms. Residential units are secluded from the street, with views of the lake, offering privacy and a place for relaxation.

Incorporating characteristic elements inspired by the famous local earthenware, a refreshing and informal atmosphere was created that is well received by both locals and the training participants.

Project gallery

Project location

Address: ban pong, ban pong district, ratchaburi 70110, thailand.

Materials and Tags

- Sustainability

想阅读文章的中文版本吗?

轮回培训中心 / Architects 49

You've started following your first account, did you know.

You'll now receive updates based on what you follow! Personalize your stream and start following your favorite authors, offices and users.

- Our Mission

Making Learning Relevant With Case Studies

The open-ended problems presented in case studies give students work that feels connected to their lives.

To prepare students for jobs that haven’t been created yet, we need to teach them how to be great problem solvers so that they’ll be ready for anything. One way to do this is by teaching content and skills using real-world case studies, a learning model that’s focused on reflection during the problem-solving process. It’s similar to project-based learning, but PBL is more focused on students creating a product.

Case studies have been used for years by businesses, law and medical schools, physicians on rounds, and artists critiquing work. Like other forms of problem-based learning, case studies can be accessible for every age group, both in one subject and in interdisciplinary work.

You can get started with case studies by tackling relatable questions like these with your students:

- How can we limit food waste in the cafeteria?

- How can we get our school to recycle and compost waste? (Or, if you want to be more complex, how can our school reduce its carbon footprint?)

- How can we improve school attendance?

- How can we reduce the number of people who get sick at school during cold and flu season?

Addressing questions like these leads students to identify topics they need to learn more about. In researching the first question, for example, students may see that they need to research food chains and nutrition. Students often ask, reasonably, why they need to learn something, or when they’ll use their knowledge in the future. Learning is most successful for students when the content and skills they’re studying are relevant, and case studies offer one way to create that sense of relevance.

Teaching With Case Studies

Ultimately, a case study is simply an interesting problem with many correct answers. What does case study work look like in classrooms? Teachers generally start by having students read the case or watch a video that summarizes the case. Students then work in small groups or individually to solve the case study. Teachers set milestones defining what students should accomplish to help them manage their time.

During the case study learning process, student assessment of learning should be focused on reflection. Arthur L. Costa and Bena Kallick’s Learning and Leading With Habits of Mind gives several examples of what this reflection can look like in a classroom:

Journaling: At the end of each work period, have students write an entry summarizing what they worked on, what worked well, what didn’t, and why. Sentence starters and clear rubrics or guidelines will help students be successful. At the end of a case study project, as Costa and Kallick write, it’s helpful to have students “select significant learnings, envision how they could apply these learnings to future situations, and commit to an action plan to consciously modify their behaviors.”

Interviews: While working on a case study, students can interview each other about their progress and learning. Teachers can interview students individually or in small groups to assess their learning process and their progress.

Student discussion: Discussions can be unstructured—students can talk about what they worked on that day in a think-pair-share or as a full class—or structured, using Socratic seminars or fishbowl discussions. If your class is tackling a case study in small groups, create a second set of small groups with a representative from each of the case study groups so that the groups can share their learning.

4 Tips for Setting Up a Case Study

1. Identify a problem to investigate: This should be something accessible and relevant to students’ lives. The problem should also be challenging and complex enough to yield multiple solutions with many layers.

2. Give context: Think of this step as a movie preview or book summary. Hook the learners to help them understand just enough about the problem to want to learn more.

3. Have a clear rubric: Giving structure to your definition of quality group work and products will lead to stronger end products. You may be able to have your learners help build these definitions.

4. Provide structures for presenting solutions: The amount of scaffolding you build in depends on your students’ skill level and development. A case study product can be something like several pieces of evidence of students collaborating to solve the case study, and ultimately presenting their solution with a detailed slide deck or an essay—you can scaffold this by providing specified headings for the sections of the essay.

Problem-Based Teaching Resources

There are many high-quality, peer-reviewed resources that are open source and easily accessible online.

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science at the University at Buffalo built an online collection of more than 800 cases that cover topics ranging from biochemistry to economics. There are resources for middle and high school students.

- Models of Excellence , a project maintained by EL Education and the Harvard Graduate School of Education, has examples of great problem- and project-based tasks—and corresponding exemplary student work—for grades pre-K to 12.

- The Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning at Purdue University is an open-source journal that publishes examples of problem-based learning in K–12 and post-secondary classrooms.

- The Tech Edvocate has a list of websites and tools related to problem-based learning.

In their book Problems as Possibilities , Linda Torp and Sara Sage write that at the elementary school level, students particularly appreciate how they feel that they are taken seriously when solving case studies. At the middle school level, “researchers stress the importance of relating middle school curriculum to issues of student concern and interest.” And high schoolers, they write, find the case study method “beneficial in preparing them for their future.”

Creating a learning center of excellence

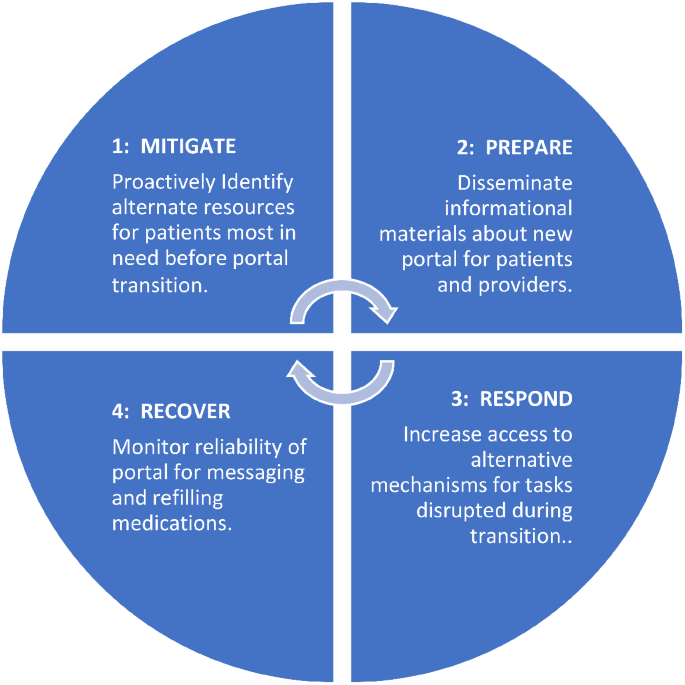

Cara helped a large insurance company architect a learning center of excellence to ensure that agency training and development was aligned to critical business needs..

The client, a large decentralized insurance firm, wanted to ensure more effective upskilling of its field-based agents. They also wanted to reduce redundant spending and duplication of efforts, modernize Learning and Development approaches, and leverage a consistent operating model. They needed to shift to a focus on results and relevance by developing new skills and capabilities, increasing knowledge retention, building communities, and improving agent performance.

CARA provided a customized blueprint to achieve the goals of the organization. It provided a clear and detailed path forward for the client to create a modern, efficient and effective Learning Center of Excellence.

CARA’s solution included:

- A recommended strategic direction and approach to launching a Learning Center of Excellence

- Leading and benchmarked best practices and critical success factors to consider when launching these types of services within a large, distributed organization

- Recommendations around strategy, structure, and processes

- A learning measurement strategy that focuses on outcomes and application of learning on the job

- An assessment of risks/issues and suggestions on how to manage them

- A learning governance strategy to ensure alignment of efforts and return on investment

- Operational process flows for executing the Learning Center of Excellence

- Organizational Change Management Plan to ensure an effective implementation of the new department

CARA provided a customized blueprint to achieve the goals of the organization. It provided a clear and detailed path forward for the client to create a modern, efficient, and effective Learning Center of Excellence.

A large insurance company was undergoing major shifts in its agency organization, including new roles and behaviors for agents, new processes and new technologies. Agencies didn’t have a single source to turn to for standardized training which resulted in redundant spending and wasted time. In addition, the corporate office was competing for the agents’ attention. With no clear structure for how or what they should learn, it was unclear how much the agents were learning and if the company was investing their training time and money wisely.

The head of agency training called CARA to get help figuring out how to approach these issues. One of CARA’s Learning Strategy consultants was assigned to the engagement. He began by working with the client to clearly define the goals and what they wanted the future state of a Learning Center of Excellence to look like.

Once the future state was defined, they met with key stakeholders, interviewed agents and took a deep dive into the processes that were in place to develop a good understanding of the current state. After the current and future state were defined, he was able to determine the gap that needed to be closed to get to the future state.

CARA’s consultant took a systematic approach to defining the steps to close the gap. He defined the critical elements for the Learning Center of Excellence and how they fit together. Creating this blueprint was like putting together a large jigsaw puzzle, making sure the elements fit together in a logical way. He had to constantly check the parts and make sure there were no overlaps or gaps in the approach and that the picture was clear to the client.

Not only did he create strategic guidance, he transitioned into the operational, creating process flows for how the Learning Center of Excellence would interact with the lines of business, including intake processes, design and development approaches, as well as review and results measurement.

Because this was an entirely new department for the client, the strategy also included key elements of an organizational change management strategy to identify the key stakeholders, understand what they needed to know and do to support the implementation of the department, and to ensure they were supported in being successful.

The CARA consultant finalized the project with a presentation to stakeholders that described a way to transform their Agency training operations into a modern, efficient and effective Learning Center of Excellence.

Don’t Miss Out!

Join the 1000’s of business leaders who receive Learning & Development, Organizational Change Management, and Communications insights from us each month!

By signing up you agree to our Terms of Use .

- Terms of Use

- Job Openings

Our Insights

- Reskilling Facts Copy

- Upskilling Facts

- Game Changer: Shifting to a Skills-Based Organization

Connect with Us

One Lincoln Centre Suite 1000 Oakbrook Terrace, IL 60181

866.401.2272

© 2024 The CARA Group.

- Change Management

- Custom Learning

- Communications

- Our Commitment

- Case Studies

- Learning and Events

- CARA Overview PDF

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

fa51e2b1dc8cca8f7467da564e77b5ea

- Make a Gift

- Join Our Email List

- Teaching with Cases

At professional schools (like Harvard’s Law, Business, Education, or Medical Schools), courses often adopt the so-called "case method" of teaching , in which students are confronted with real-world problems or scenarios involving multiple stakeholders and competing priorities. Most of the cases which faculty use with their students are written by professionals who have expertise in researching and writing in that genre, and for good reason—writing a truly masterful case, one which can engage students in hours of debate and deliberation, takes a lot of time and effort. It can be effective, nevertheless, for you to try implementing some aspects of the case-teaching approach in your class. Among the benefits which accrue to using case studies are the following:

- the fact that it gives your students the opportunity to "practice" a real-world application;

- the fact that it compels them (and you!) to reconstruct all of the divergent and convergent perspectives which different parties might bring to the scenario;

- the fact that it motivates your students to anticipate a wide range of possible responses which a reader might have; and

- the fact that it invites your students to indulge in metacognition as they revisit the process by which they became more knowledgeable about the scenario.

Features of an Effective Teaching Case

While no two case studies will be exactly alike, here are some of those principles:

- The case should illustrate what happens when a concept from the course could be, or has been, applied in the real world. Depending on the course, a “concept” might mean any one among a range of things, including an abstract principle, a theory, a tension, an issue, a method, an approach, or simply a way of thinking characteristic of an academic field. Whichever you choose, you should make sure to “ground” the case in a realistic setting early in the narrative, so that participants understand their role in the scenario.

- The case materials should include enough factual content and context to allow students to explore multiple perspectives. In order for participants to feel that they are encountering a real-world application of the course material, and that they have some freedom and agency in terms of how they interpret it, they need to be able to see the issue or problem from more than one perspective. Moreover, those perspectives need to seem genuine, and to be sketched in enough detail to seem complex. (In fact, it’s not a bad idea to include some “extraneous” information about the stakeholders involved in the case, so that students have to filter out things that seem relevant or irrelevant to them.) Otherwise, participants may fall back on picking obvious “winners” and “losers” rather than seeking creative, negotiated solutions that satisfy multiple stakeholders.

- The case materials should confront participants with a range of realistic constraints, hard choices, and authentic outcomes. If the case presumes that participants will all become omniscient, enjoy limitless resources, and succeed, they won’t learn as much about themselves as team-members and decision-makers as if they are forced to confront limitations, to make tough decisions about priorities, and to be prepared for unexpected results. These constraints and outcomes can be things which have been documented in real life, but they can also be things which the participants themselves surface in their deliberations.

- The activity should include space to reflect upon the decision-making process and the lessons of the case. Writing a case offers an opportunity to engage in multiple layers of reflection. For you, as the case writer, it is an occasion to anticipate how you (if you were the instructor) might create scenarios that are aligned with, and likely to meet the learning objectives of, a given unit of your course. For the participants whom you imagine using your case down the road, the case ideally should help them (1) to understand their own hidden assumptions, priorities, values, and biases better; and (2) to close the gap between their classroom learning and its potential real-world applications.

For more information...

Kim, Sara et al. 2006. "A Conceptual Framework for Developing Teaching Cases: A Review and Synthesis of the Literature across Disciplines." Medical Education 40: 867–876.

Herreid, Clyde Freeman. 2011. "Case Study Teaching." New Directions for Teaching and Learning 128: 31–40.

Nohria, Nitin. 2021. "What the Case Study Method Really Teaches." Harvard Business Review .

Swiercz, Paul Michael. "SWIF Learning: A Guide to Student Written-Instructor Facilitated Case Writing."

- Designing Your Course

- A Teaching Timeline: From Pre-Term Planning to the Final Exam

- The First Day of Class

- Group Agreements

- Classroom Debate

- Flipped Classrooms

- Leading Discussions

- Polling & Clickers

- Problem Solving in STEM

- Engaged Scholarship

- Devices in the Classroom

- Beyond the Classroom

- On Professionalism

- Getting Feedback

- Equitable & Inclusive Teaching

- Advising and Mentoring

- Teaching and Your Career

- Teaching Remotely

- Tools and Platforms

- The Science of Learning

- Bok Publications

- Other Resources Around Campus

- Publications

- Conferences & Events

- Professional Learning

- Science Standards

- Awards & Competitions

- Daily Do Lesson Plans

- Free Resources

- American Rescue Plan

- For Preservice Teachers

NCCSTS Case Collection

- Partner Jobs in Education

- Interactive eBooks+

- Digital Catalog

- Regional Product Representatives

- e-Newsletters

- Bestselling Books

- Latest Books

- Popular Book Series

- Prospective Authors

- Web Seminars

- Exhibits & Sponsorship

- Conference Reviewers

- National Conference • Denver 24

- Leaders Institute 2024

- National Conference • New Orleans 24

- Submit a Proposal

- Latest Resources

- Professional Learning Units & Courses

- For Districts

- Online Course Providers

- Schools & Districts

- College Professors & Students

- The Standards

- Teachers and Admin

- eCYBERMISSION

- Toshiba/NSTA ExploraVision

- Junior Science & Humanities Symposium

- Teaching Awards

- Climate Change

- Earth & Space Science

- New Science Teachers

- Early Childhood

- Middle School

- High School

- Postsecondary

- Informal Education

- Journal Articles

- Lesson Plans

- e-newsletters

- Science & Children

- Science Scope

- The Science Teacher

- Journal of College Sci. Teaching

- Connected Science Learning

- NSTA Reports

- Next-Gen Navigator

- Science Update

- Teacher Tip Tuesday

- Trans. Sci. Learning

MyNSTA Community

- My Collections

Case Study Listserv

Permissions & Guidelines

Submit a Case Study

Resources & Publications

Enrich your students’ educational experience with case-based teaching

The NCCSTS Case Collection, created and curated by the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science, on behalf of the University at Buffalo, contains over a thousand peer-reviewed case studies on a variety of topics in all areas of science.

Cases (only) are freely accessible; subscription is required for access to teaching notes and answer keys.

Subscribe Today

Browse Case Studies

Latest Case Studies

Development of the NCCSTS Case Collection was originally funded by major grants to the University at Buffalo from the National Science Foundation , The Pew Charitable Trusts , and the U.S. Department of Education .

Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning

- Case Based Learning

What is the case method?

In case-based learning, students learn to interact with and manipulate basic foundational knowledge by working with situations resembling specific real-world scenarios.

How does it work?

Case studies encourage students to use critical thinking skills to identify and narrow an issue, develop and evaluate alternatives, and offer a solution. In fact, Nkhoma (2016), who studied the value of developing case-based learning activities based on Bloom’s Taxonomy of thinking skills, suggests that this approach encourages deep learning through critical thinking:

Sherfield (2004) confirms this, asserting that working through case studies can begin to build and expand these six critical thinking strategies:

- Emotional restraint

- Questioning

- Distinguishing fact from fiction

- Searching for ambiguity

What makes a good case?

Case-based learning can focus on anything from a one-sentence physics word problem to a textbook-sized nursing case or a semester-long case in a law course. Though we often assume that a case is a “problem,” Ellet (2007) suggests that most cases entail one of four types of situations:

- Evaluations

- What are the facts you know about the case?

- What are some logical assumptions you can make about the case?

- What are the problems involved in the case as you see it?

- What is the root problem (the main issue)?

- What do you estimate is the cause of the root problem?

- What are the reasons that the root problem exists?

- What is the solution to the problem?

- Are there any moral or ethical considerations to your solution?

- What are the real-world implications for this case?

- How might the lives of the people in the case study be changed because of your proposed solution?

- Where in your world (campus/town/country) might a problem like this occur?

- Where could someone get help with this problem?

- What personal advice would you give to the person or people concerned?

Adapted from Sherfield’s Case Studies for the First Year (2004)

Some faculty buy prepared cases from publishers, but many create their own based on their unique course needs. When introducing case-based learning to students, be sure to offer a series of guidelines or questions to prompt deep thinking. One option is to provide a scenario followed by questions; for example, questions designed for a first year experience problem might include these:

Before you begin, take a look at what others are doing with cases in your field. Pre-made case studies are available from various publishers, and you can find case-study templates online.

- Choose scenarios carefully

- Tell a story from beginning to end, including many details

- Create real-life characters and use quotes when possible

- Write clearly and concisely and format the writing simply

- Ask students to reflect on their learning—perhaps identifying connections between the lesson and specific course learning outcomes—after working a case

Additional Resources

- Barnes, Louis B. et al. Teaching and the Case Method , 3 rd (1994). Harvard, 1994.

- Campoy, Renee. Case Study Analysis in the Classroom: Becoming a Reflective Teacher . Sage Publications, 2005.

- Ellet, William. The Case Study Handbook . Harvard, 2007.

- Herreid, Clyde Freeman, ed. Start with a Story: The Case Study Method of Teaching College Science . NSTA, 2007.

- Herreid, Clyde Freeman, et al. Science Stories: Using Case Studies to Teach Critical Thinking . NSTA, 2012.

- Nkhoma, M., Lam, et al. Developing case-based learning activities based on the revised Bloom’s Taxonomy . Proceedings of Informing Science & IT Education Conference (In SITE) 2016, 85-93. 2016.

- Rolls, Geoff. Classic Case Studies in Psychology , 3 rd Hodder Education, Bookpoint, 2014.

- Sherfield, Robert M., et al. Case Studies for the First Year . Pearson, 2004.

- Shulman, Judith H., ed. Case Methods in Teacher Education . Teacher’s College, 1992.

Quick Links

- Developing Learning Objectives

- Creating Your Syllabus

- Active Learning

- Service Learning

- Critical Thinking and other Higher-Order Thinking Skills

- Group and Team Based Learning

- Integrating Technology in the Classroom

- Effective PowerPoint Design

- Hybrid and Hybrid Limited Course Design

- Online Course Design

Consult with our CETL Professionals

Consultation services are available to all UConn faculty at all campuses at no charge.

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 10 min read

Case Study-Based Learning

Enhancing learning through immediate application.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

If you've ever tried to learn a new concept, you probably appreciate that "knowing" is different from "doing." When you have an opportunity to apply your knowledge, the lesson typically becomes much more real.

Adults often learn differently from children, and we have different motivations for learning. Typically, we learn new skills because we want to. We recognize the need to learn and grow, and we usually need – or want – to apply our newfound knowledge soon after we've learned it.

A popular theory of adult learning is andragogy (the art and science of leading man, or adults), as opposed to the better-known pedagogy (the art and science of leading children). Malcolm Knowles , a professor of adult education, was considered the father of andragogy, which is based on four key observations of adult learners:

- Adults learn best if they know why they're learning something.

- Adults often learn best through experience.

- Adults tend to view learning as an opportunity to solve problems.

- Adults learn best when the topic is relevant to them and immediately applicable.

This means that you'll get the best results with adults when they're fully involved in the learning experience. Give an adult an opportunity to practice and work with a new skill, and you have a solid foundation for high-quality learning that the person will likely retain over time.

So, how can you best use these adult learning principles in your training and development efforts? Case studies provide an excellent way of practicing and applying new concepts. As such, they're very useful tools in adult learning, and it's important to understand how to get the maximum value from them.

What Is a Case Study?

Case studies are a form of problem-based learning, where you present a situation that needs a resolution. A typical business case study is a detailed account, or story, of what happened in a particular company, industry, or project over a set period of time.

The learner is given details about the situation, often in a historical context. The key players are introduced. Objectives and challenges are outlined. This is followed by specific examples and data, which the learner then uses to analyze the situation, determine what happened, and make recommendations.

The depth of a case depends on the lesson being taught. A case study can be two pages, 20 pages, or more. A good case study makes the reader think critically about the information presented, and then develop a thorough assessment of the situation, leading to a well-thought-out solution or recommendation.

Why Use a Case Study?

Case studies are a great way to improve a learning experience, because they get the learner involved, and encourage immediate use of newly acquired skills.

They differ from lectures or assigned readings because they require participation and deliberate application of a broad range of skills. For example, if you study financial analysis through straightforward learning methods, you may have to calculate and understand a long list of financial ratios (don't worry if you don't know what these are). Likewise, you may be given a set of financial statements to complete a ratio analysis. But until you put the exercise into context, you may not really know why you're doing the analysis.

With a case study, however, you might explore whether a bank should provide financing to a borrower, or whether a company is about to make a good acquisition. Suddenly, the act of calculating ratios becomes secondary – it's more important to understand what the ratios tell you. This is how case studies can make the difference between knowing what to do, and knowing how, when, and why to do it.

Then, what really separates case studies from other practical forms of learning – like scenarios and simulations – is the ability to compare the learner's recommendations with what actually happened. When you know what really happened, it's much easier to evaluate the "correctness" of the answers given.

When to Use a Case Study

As you can see, case studies are powerful and effective training tools. They also work best with practical, applied training, so make sure you use them appropriately.

Remember these tips:

- Case studies tend to focus on why and how to apply a skill or concept, not on remembering facts and details. Use case studies when understanding the concept is more important than memorizing correct responses.

- Case studies are great team-building opportunities. When a team gets together to solve a case, they'll have to work through different opinions, methods, and perspectives.

- Use case studies to build problem-solving skills, particularly those that are valuable when applied, but are likely to be used infrequently. This helps people get practice with these skills that they might not otherwise get.

- Case studies can be used to evaluate past problem solving. People can be asked what they'd do in that situation, and think about what could have been done differently.

Ensuring Maximum Value From Case Studies

The first thing to remember is that you already need to have enough theoretical knowledge to handle the questions and challenges in the case study. Otherwise, it can be like trying to solve a puzzle with some of the pieces missing.

Here are some additional tips for how to approach a case study. Depending on the exact nature of the case, some tips will be more relevant than others.

- Read the case at least three times before you start any analysis. Case studies usually have lots of details, and it's easy to miss something in your first, or even second, reading.

- Once you're thoroughly familiar with the case, note the facts. Identify which are relevant to the tasks you've been assigned. In a good case study, there are often many more facts than you need for your analysis.

- If the case contains large amounts of data, analyze this data for relevant trends. For example, have sales dropped steadily, or was there an unexpected high or low point?

- If the case involves a description of a company's history, find the key events, and consider how they may have impacted the current situation.

- Consider using techniques like SWOT analysis and Porter's Five Forces Analysis to understand the organization's strategic position.

- Stay with the facts when you draw conclusions. These include facts given in the case as well as established facts about the environmental context. Don't rely on personal opinions when you put together your answers.

Writing a Case Study

You may have to write a case study yourself. These are complex documents that take a while to research and compile. The quality of the case study influences the quality of the analysis. Here are some tips if you want to write your own:

- Write your case study as a structured story. The goal is to capture an interesting situation or challenge and then bring it to life with words and information. You want the reader to feel a part of what's happening.

- Present information so that a "right" answer isn't obvious. The goal is to develop the learner's ability to analyze and assess, not necessarily to make the same decision as the people in the actual case.

- Do background research to fully understand what happened and why. You may need to talk to key stakeholders to get their perspectives as well.

- Determine the key challenge. What needs to be resolved? The case study should focus on one main question or issue.

- Define the context. Talk about significant events leading up to the situation. What organizational factors are important for understanding the problem and assessing what should be done? Include cultural factors where possible.

- Identify key decision makers and stakeholders. Describe their roles and perspectives, as well as their motivations and interests.

- Make sure that you provide the right data to allow people to reach appropriate conclusions.

- Make sure that you have permission to use any information you include.

A typical case study structure includes these elements:

- Executive summary. Define the objective, and state the key challenge.

- Opening paragraph. Capture the reader's interest.

- Scope. Describe the background, context, approach, and issues involved.

- Presentation of facts. Develop an objective picture of what's happening.

- Description of key issues. Present viewpoints, decisions, and interests of key parties.

Because case studies have proved to be such effective teaching tools, many are already written. Some excellent sources of free cases are The Times 100 , CasePlace.org , and Schroeder & Schroeder Inc . You can often search for cases by topic or industry. These cases are expertly prepared, based mostly on real situations, and used extensively in business schools to teach management concepts.

Case studies are a great way to improve learning and training. They provide learners with an opportunity to solve a problem by applying what they know.

There are no unpleasant consequences for getting it "wrong," and cases give learners a much better understanding of what they really know and what they need to practice.

Case studies can be used in many ways, as team-building tools, and for skill development. You can write your own case study, but a large number are already prepared. Given the enormous benefits of practical learning applications like this, case studies are definitely something to consider adding to your next training session.

Knowles, M. (1973). 'The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species [online].' Available here .

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

Book Insights

Five Star Service: How to Deliver Exceptional Customer Service

Michael Heppel

Expert Interviews

Kiss, Bow, or Shake Hands

Terri Morrison

Add comment

Comments (0)

Be the first to comment!

Get 30% off your first year of Mind Tools

Great teams begin with empowered leaders. Our tools and resources offer the support to let you flourish into leadership. Join today!

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Newest Releases

What Is Stakeholder Management?

GE-McKinsey Matrix

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

Business reports.

Using the Right Format for Sharing Information

Making the Right Career Move

Choosing the Role That's Best for You

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Negotiation no-nos.

Avoid These Mistakes To Get What You Want

Animated Video

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

Using Case Studies to Teach

Why Use Cases?

Many students are more inductive than deductive reasoners, which means that they learn better from examples than from logical development starting with basic principles. The use of case studies can therefore be a very effective classroom technique.

Case studies are have long been used in business schools, law schools, medical schools and the social sciences, but they can be used in any discipline when instructors want students to explore how what they have learned applies to real world situations. Cases come in many formats, from a simple “What would you do in this situation?” question to a detailed description of a situation with accompanying data to analyze. Whether to use a simple scenario-type case or a complex detailed one depends on your course objectives.

Most case assignments require students to answer an open-ended question or develop a solution to an open-ended problem with multiple potential solutions. Requirements can range from a one-paragraph answer to a fully developed group action plan, proposal or decision.

Common Case Elements

Most “full-blown” cases have these common elements:

- A decision-maker who is grappling with some question or problem that needs to be solved.

- A description of the problem’s context (a law, an industry, a family).

- Supporting data, which can range from data tables to links to URLs, quoted statements or testimony, supporting documents, images, video, or audio.

Case assignments can be done individually or in teams so that the students can brainstorm solutions and share the work load.

The following discussion of this topic incorporates material presented by Robb Dixon of the School of Management and Rob Schadt of the School of Public Health at CEIT workshops. Professor Dixon also provided some written comments that the discussion incorporates.

Advantages to the use of case studies in class

A major advantage of teaching with case studies is that the students are actively engaged in figuring out the principles by abstracting from the examples. This develops their skills in:

- Problem solving

- Analytical tools, quantitative and/or qualitative, depending on the case

- Decision making in complex situations

- Coping with ambiguities

Guidelines for using case studies in class

In the most straightforward application, the presentation of the case study establishes a framework for analysis. It is helpful if the statement of the case provides enough information for the students to figure out solutions and then to identify how to apply those solutions in other similar situations. Instructors may choose to use several cases so that students can identify both the similarities and differences among the cases.

Depending on the course objectives, the instructor may encourage students to follow a systematic approach to their analysis. For example:

- What is the issue?

- What is the goal of the analysis?

- What is the context of the problem?

- What key facts should be considered?

- What alternatives are available to the decision-maker?

- What would you recommend — and why?

An innovative approach to case analysis might be to have students role-play the part of the people involved in the case. This not only actively engages students, but forces them to really understand the perspectives of the case characters. Videos or even field trips showing the venue in which the case is situated can help students to visualize the situation that they need to analyze.

Accompanying Readings

Case studies can be especially effective if they are paired with a reading assignment that introduces or explains a concept or analytical method that applies to the case. The amount of emphasis placed on the use of the reading during the case discussion depends on the complexity of the concept or method. If it is straightforward, the focus of the discussion can be placed on the use of the analytical results. If the method is more complex, the instructor may need to walk students through its application and the interpretation of the results.

Leading the Case Discussion and Evaluating Performance

Decision cases are more interesting than descriptive ones. In order to start the discussion in class, the instructor can start with an easy, noncontroversial question that all the students should be able to answer readily. However, some of the best case discussions start by forcing the students to take a stand. Some instructors will ask a student to do a formal “open” of the case, outlining his or her entire analysis. Others may choose to guide discussion with questions that move students from problem identification to solutions. A skilled instructor steers questions and discussion to keep the class on track and moving at a reasonable pace.

In order to motivate the students to complete the assignment before class as well as to stimulate attentiveness during the class, the instructor should grade the participation—quantity and especially quality—during the discussion of the case. This might be a simple check, check-plus, check-minus or zero. The instructor should involve as many students as possible. In order to engage all the students, the instructor can divide them into groups, give each group several minutes to discuss how to answer a question related to the case, and then ask a randomly selected person in each group to present the group’s answer and reasoning. Random selection can be accomplished through rolling of dice, shuffled index cards, each with one student’s name, a spinning wheel, etc.

Tips on the Penn State U. website: http://tlt.its.psu.edu/suggestions/cases/

If you are interested in using this technique in a science course, there is a good website on use of case studies in the sciences at the University of Buffalo.

Dunne, D. and Brooks, K. (2004) Teaching with Cases (Halifax, NS: Society for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education), ISBN 0-7703-8924-4 (Can be ordered at http://www.bookstore.uwo.ca/ at a cost of $15.00)

- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Office of Teaching, Learning, and Innovation

- University Policies

- Columbia Online

- Academic Calendar

- Resources and Technology

- Resources and Guides

Case Method Teaching and Learning

What is the case method? How can the case method be used to engage learners? What are some strategies for getting started? This guide helps instructors answer these questions by providing an overview of the case method while highlighting learner-centered and digitally-enhanced approaches to teaching with the case method. The guide also offers tips to instructors as they get started with the case method and additional references and resources.

On this page:

What is case method teaching.

- Case Method at Columbia

Why use the Case Method?

Case method teaching approaches, how do i get started.

- Additional Resources

The CTL is here to help!

For support with implementing a case method approach in your course, email [email protected] to schedule your 1-1 consultation .

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2019). Case Method Teaching and Learning. Columbia University. Retrieved from [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/case-method/

Case method 1 teaching is an active form of instruction that focuses on a case and involves students learning by doing 2 3 . Cases are real or invented stories 4 that include “an educational message” or recount events, problems, dilemmas, theoretical or conceptual issue that requires analysis and/or decision-making.

Case-based teaching simulates real world situations and asks students to actively grapple with complex problems 5 6 This method of instruction is used across disciplines to promote learning, and is common in law, business, medicine, among other fields. See Table 1 below for a few types of cases and the learning they promote.

Table 1: Types of cases and the learning they promote.

For a more complete list, see Case Types & Teaching Methods: A Classification Scheme from the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science.

Back to Top

Case Method Teaching and Learning at Columbia

The case method is actively used in classrooms across Columbia, at the Morningside campus in the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA), the School of Business, Arts and Sciences, among others, and at Columbia University Irving Medical campus.

Faculty Spotlight:

Professor Mary Ann Price on Using Case Study Method to Place Pre-Med Students in Real-Life Scenarios

Read more

Professor De Pinho on Using the Case Method in the Mailman Core

Case method teaching has been found to improve student learning, to increase students’ perception of learning gains, and to meet learning objectives 8 9 . Faculty have noted the instructional benefits of cases including greater student engagement in their learning 10 , deeper student understanding of concepts, stronger critical thinking skills, and an ability to make connections across content areas and view an issue from multiple perspectives 11 .

Through case-based learning, students are the ones asking questions about the case, doing the problem-solving, interacting with and learning from their peers, “unpacking” the case, analyzing the case, and summarizing the case. They learn how to work with limited information and ambiguity, think in professional or disciplinary ways, and ask themselves “what would I do if I were in this specific situation?”

The case method bridges theory to practice, and promotes the development of skills including: communication, active listening, critical thinking, decision-making, and metacognitive skills 12 , as students apply course content knowledge, reflect on what they know and their approach to analyzing, and make sense of a case.

Though the case method has historical roots as an instructor-centered approach that uses the Socratic dialogue and cold-calling, it is possible to take a more learner-centered approach in which students take on roles and tasks traditionally left to the instructor.

Cases are often used as “vehicles for classroom discussion” 13 . Students should be encouraged to take ownership of their learning from a case. Discussion-based approaches engage students in thinking and communicating about a case. Instructors can set up a case activity in which students are the ones doing the work of “asking questions, summarizing content, generating hypotheses, proposing theories, or offering critical analyses” 14 .

The role of the instructor is to share a case or ask students to share or create a case to use in class, set expectations, provide instructions, and assign students roles in the discussion. Student roles in a case discussion can include:

- discussion “starters” get the conversation started with a question or posing the questions that their peers came up with;

- facilitators listen actively, validate the contributions of peers, ask follow-up questions, draw connections, refocus the conversation as needed;

- recorders take-notes of the main points of the discussion, record on the board, upload to CourseWorks, or type and project on the screen; and

- discussion “wrappers” lead a summary of the main points of the discussion.

Prior to the case discussion, instructors can model case analysis and the types of questions students should ask, co-create discussion guidelines with students, and ask for students to submit discussion questions. During the discussion, the instructor can keep time, intervene as necessary (however the students should be doing the talking), and pause the discussion for a debrief and to ask students to reflect on what and how they learned from the case activity.

Note: case discussions can be enhanced using technology. Live discussions can occur via video-conferencing (e.g., using Zoom ) or asynchronous discussions can occur using the Discussions tool in CourseWorks (Canvas) .

Table 2 includes a few interactive case method approaches. Regardless of the approach selected, it is important to create a learning environment in which students feel comfortable participating in a case activity and learning from one another. See below for tips on supporting student in how to learn from a case in the “getting started” section and how to create a supportive learning environment in the Guide for Inclusive Teaching at Columbia .

Table 2. Strategies for Engaging Students in Case-Based Learning

Approaches to case teaching should be informed by course learning objectives, and can be adapted for small, large, hybrid, and online classes. Instructional technology can be used in various ways to deliver, facilitate, and assess the case method. For instance, an online module can be created in CourseWorks (Canvas) to structure the delivery of the case, allow students to work at their own pace, engage all learners, even those reluctant to speak up in class, and assess understanding of a case and student learning. Modules can include text, embedded media (e.g., using Panopto or Mediathread ) curated by the instructor, online discussion, and assessments. Students can be asked to read a case and/or watch a short video, respond to quiz questions and receive immediate feedback, post questions to a discussion, and share resources.

For more information about options for incorporating educational technology to your course, please contact your Learning Designer .

To ensure that students are learning from the case approach, ask them to pause and reflect on what and how they learned from the case. Time to reflect builds your students’ metacognition, and when these reflections are collected they provides you with insights about the effectiveness of your approach in promoting student learning.

Well designed case-based learning experiences: 1) motivate student involvement, 2) have students doing the work, 3) help students develop knowledge and skills, and 4) have students learning from each other.

Designing a case-based learning experience should center around the learning objectives for a course. The following points focus on intentional design.

Identify learning objectives, determine scope, and anticipate challenges.

- Why use the case method in your course? How will it promote student learning differently than other approaches?

- What are the learning objectives that need to be met by the case method? What knowledge should students apply and skills should they practice?

- What is the scope of the case? (a brief activity in a single class session to a semester-long case-based course; if new to case method, start small with a single case).

- What challenges do you anticipate (e.g., student preparation and prior experiences with case learning, discomfort with discussion, peer-to-peer learning, managing discussion) and how will you plan for these in your design?

- If you are asking students to use transferable skills for the case method (e.g., teamwork, digital literacy) make them explicit.

Determine how you will know if the learning objectives were met and develop a plan for evaluating the effectiveness of the case method to inform future case teaching.

- What assessments and criteria will you use to evaluate student work or participation in case discussion?

- How will you evaluate the effectiveness of the case method? What feedback will you collect from students?

- How might you leverage technology for assessment purposes? For example, could you quiz students about the case online before class, accept assignment submissions online, use audience response systems (e.g., PollEverywhere) for formative assessment during class?

Select an existing case, create your own, or encourage students to bring course-relevant cases, and prepare for its delivery

- Where will the case method fit into the course learning sequence?

- Is the case at the appropriate level of complexity? Is it inclusive, culturally relevant, and relatable to students?

- What materials and preparation will be needed to present the case to students? (e.g., readings, audiovisual materials, set up a module in CourseWorks).

Plan for the case discussion and an active role for students

- What will your role be in facilitating case-based learning? How will you model case analysis for your students? (e.g., present a short case and demo your approach and the process of case learning) (Davis, 2009).

- What discussion guidelines will you use that include your students’ input?

- How will you encourage students to ask and answer questions, summarize their work, take notes, and debrief the case?

- If students will be working in groups, how will groups form? What size will the groups be? What instructions will they be given? How will you ensure that everyone participates? What will they need to submit? Can technology be leveraged for any of these areas?

- Have you considered students of varied cognitive and physical abilities and how they might participate in the activities/discussions, including those that involve technology?

Student preparation and expectations

- How will you communicate about the case method approach to your students? When will you articulate the purpose of case-based learning and expectations of student engagement? What information about case-based learning and expectations will be included in the syllabus?

- What preparation and/or assignment(s) will students complete in order to learn from the case? (e.g., read the case prior to class, watch a case video prior to class, post to a CourseWorks discussion, submit a brief memo, complete a short writing assignment to check students’ understanding of a case, take on a specific role, prepare to present a critique during in-class discussion).

Andersen, E. and Schiano, B. (2014). Teaching with Cases: A Practical Guide . Harvard Business Press.

Bonney, K. M. (2015). Case Study Teaching Method Improves Student Performance and Perceptions of Learning Gains†. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education , 16 (1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v16i1.846

Davis, B.G. (2009). Chapter 24: Case Studies. In Tools for Teaching. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass.

Garvin, D.A. (2003). Making the Case: Professional Education for the world of practice. Harvard Magazine. September-October 2003, Volume 106, Number 1, 56-107.

Golich, V.L. (2000). The ABCs of Case Teaching. International Studies Perspectives. 1, 11-29.

Golich, V.L.; Boyer, M; Franko, P.; and Lamy, S. (2000). The ABCs of Case Teaching. Pew Case Studies in International Affairs. Institute for the Study of Diplomacy.

Heath, J. (2015). Teaching & Writing Cases: A Practical Guide. The Case Center, UK.

Herreid, C.F. (2011). Case Study Teaching. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. No. 128, Winder 2011, 31 – 40.

Herreid, C.F. (2007). Start with a Story: The Case Study Method of Teaching College Science . National Science Teachers Association. Available as an ebook through Columbia Libraries.

Herreid, C.F. (2006). “Clicker” Cases: Introducing Case Study Teaching Into Large Classrooms. Journal of College Science Teaching. Oct 2006, 36(2). https://search.proquest.com/docview/200323718?pq-origsite=gscholar

Krain, M. (2016). Putting the Learning in Case Learning? The Effects of Case-Based Approaches on Student Knowledge, Attitudes, and Engagement. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching. 27(2), 131-153.

Lundberg, K.O. (Ed.). (2011). Our Digital Future: Boardrooms and Newsrooms. Knight Case Studies Initiative.

Popil, I. (2011). Promotion of critical thinking by using case studies as teaching method. Nurse Education Today, 31(2), 204–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2010.06.002

Schiano, B. and Andersen, E. (2017). Teaching with Cases Online . Harvard Business Publishing.

Thistlethwaite, JE; Davies, D.; Ekeocha, S.; Kidd, J.M.; MacDougall, C.; Matthews, P.; Purkis, J.; Clay D. (2012). The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education: A BEME systematic review . Medical Teacher. 2012; 34(6): e421-44.

Yadav, A.; Lundeberg, M.; DeSchryver, M.; Dirkin, K.; Schiller, N.A.; Maier, K. and Herreid, C.F. (2007). Teaching Science with Case Studies: A National Survey of Faculty Perceptions of the Benefits and Challenges of Using Cases. Journal of College Science Teaching; Sept/Oct 2007; 37(1).

Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass.

Additional resources

Teaching with Cases , Harvard Kennedy School of Government.

Features “what is a teaching case?” video that defines a teaching case, and provides documents to help students prepare for case learning, Common case teaching challenges and solutions, tips for teaching with cases.

Promoting excellence and innovation in case method teaching: Teaching by the Case Method , Christensen Center for Teaching & Learning. Harvard Business School.

National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science . University of Buffalo.

A collection of peer-reviewed STEM cases to teach scientific concepts and content, promote process skills and critical thinking. The Center welcomes case submissions. Case classification scheme of case types and teaching methods:

- Different types of cases: analysis case, dilemma/decision case, directed case, interrupted case, clicker case, a flipped case, a laboratory case.

- Different types of teaching methods: problem-based learning, discussion, debate, intimate debate, public hearing, trial, jigsaw, role-play.

Columbia Resources

Resources available to support your use of case method: The University hosts a number of case collections including: the Case Consortium (a collection of free cases in the fields of journalism, public policy, public health, and other disciplines that include teaching and learning resources; SIPA’s Picker Case Collection (audiovisual case studies on public sector innovation, filmed around the world and involving SIPA student teams in producing the cases); and Columbia Business School CaseWorks , which develops teaching cases and materials for use in Columbia Business School classrooms.

Center for Teaching and Learning

The Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) offers a variety of programs and services for instructors at Columbia. The CTL can provide customized support as you plan to use the case method approach through implementation. Schedule a one-on-one consultation.

Office of the Provost