Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, what is a hypothesis and how do i write one.

General Education

Think about something strange and unexplainable in your life. Maybe you get a headache right before it rains, or maybe you think your favorite sports team wins when you wear a certain color. If you wanted to see whether these are just coincidences or scientific fact, you would form a hypothesis, then create an experiment to see whether that hypothesis is true or not.

But what is a hypothesis, anyway? If you’re not sure about what a hypothesis is--or how to test for one!--you’re in the right place. This article will teach you everything you need to know about hypotheses, including:

- Defining the term “hypothesis”

- Providing hypothesis examples

- Giving you tips for how to write your own hypothesis

So let’s get started!

What Is a Hypothesis?

Merriam Webster defines a hypothesis as “an assumption or concession made for the sake of argument.” In other words, a hypothesis is an educated guess . Scientists make a reasonable assumption--or a hypothesis--then design an experiment to test whether it’s true or not. Keep in mind that in science, a hypothesis should be testable. You have to be able to design an experiment that tests your hypothesis in order for it to be valid.

As you could assume from that statement, it’s easy to make a bad hypothesis. But when you’re holding an experiment, it’s even more important that your guesses be good...after all, you’re spending time (and maybe money!) to figure out more about your observation. That’s why we refer to a hypothesis as an educated guess--good hypotheses are based on existing data and research to make them as sound as possible.

Hypotheses are one part of what’s called the scientific method . Every (good) experiment or study is based in the scientific method. The scientific method gives order and structure to experiments and ensures that interference from scientists or outside influences does not skew the results. It’s important that you understand the concepts of the scientific method before holding your own experiment. Though it may vary among scientists, the scientific method is generally made up of six steps (in order):

- Observation

- Asking questions

- Forming a hypothesis

- Analyze the data

- Communicate your results

You’ll notice that the hypothesis comes pretty early on when conducting an experiment. That’s because experiments work best when they’re trying to answer one specific question. And you can’t conduct an experiment until you know what you’re trying to prove!

Independent and Dependent Variables

After doing your research, you’re ready for another important step in forming your hypothesis: identifying variables. Variables are basically any factor that could influence the outcome of your experiment . Variables have to be measurable and related to the topic being studied.

There are two types of variables: independent variables and dependent variables. I ndependent variables remain constant . For example, age is an independent variable; it will stay the same, and researchers can look at different ages to see if it has an effect on the dependent variable.

Speaking of dependent variables... dependent variables are subject to the influence of the independent variable , meaning that they are not constant. Let’s say you want to test whether a person’s age affects how much sleep they need. In that case, the independent variable is age (like we mentioned above), and the dependent variable is how much sleep a person gets.

Variables will be crucial in writing your hypothesis. You need to be able to identify which variable is which, as both the independent and dependent variables will be written into your hypothesis. For instance, in a study about exercise, the independent variable might be the speed at which the respondents walk for thirty minutes, and the dependent variable would be their heart rate. In your study and in your hypothesis, you’re trying to understand the relationship between the two variables.

Elements of a Good Hypothesis

The best hypotheses start by asking the right questions . For instance, if you’ve observed that the grass is greener when it rains twice a week, you could ask what kind of grass it is, what elevation it’s at, and if the grass across the street responds to rain in the same way. Any of these questions could become the backbone of experiments to test why the grass gets greener when it rains fairly frequently.

As you’re asking more questions about your first observation, make sure you’re also making more observations . If it doesn’t rain for two weeks and the grass still looks green, that’s an important observation that could influence your hypothesis. You'll continue observing all throughout your experiment, but until the hypothesis is finalized, every observation should be noted.

Finally, you should consult secondary research before writing your hypothesis . Secondary research is comprised of results found and published by other people. You can usually find this information online or at your library. Additionally, m ake sure the research you find is credible and related to your topic. If you’re studying the correlation between rain and grass growth, it would help you to research rain patterns over the past twenty years for your county, published by a local agricultural association. You should also research the types of grass common in your area, the type of grass in your lawn, and whether anyone else has conducted experiments about your hypothesis. Also be sure you’re checking the quality of your research . Research done by a middle school student about what minerals can be found in rainwater would be less useful than an article published by a local university.

Writing Your Hypothesis

Once you’ve considered all of the factors above, you’re ready to start writing your hypothesis. Hypotheses usually take a certain form when they’re written out in a research report.

When you boil down your hypothesis statement, you are writing down your best guess and not the question at hand . This means that your statement should be written as if it is fact already, even though you are simply testing it.

The reason for this is that, after you have completed your study, you'll either accept or reject your if-then or your null hypothesis. All hypothesis testing examples should be measurable and able to be confirmed or denied. You cannot confirm a question, only a statement!

In fact, you come up with hypothesis examples all the time! For instance, when you guess on the outcome of a basketball game, you don’t say, “Will the Miami Heat beat the Boston Celtics?” but instead, “I think the Miami Heat will beat the Boston Celtics.” You state it as if it is already true, even if it turns out you’re wrong. You do the same thing when writing your hypothesis.

Additionally, keep in mind that hypotheses can range from very specific to very broad. These hypotheses can be specific, but if your hypothesis testing examples involve a broad range of causes and effects, your hypothesis can also be broad.

The Two Types of Hypotheses

Now that you understand what goes into a hypothesis, it’s time to look more closely at the two most common types of hypothesis: the if-then hypothesis and the null hypothesis.

#1: If-Then Hypotheses

First of all, if-then hypotheses typically follow this formula:

If ____ happens, then ____ will happen.

The goal of this type of hypothesis is to test the causal relationship between the independent and dependent variable. It’s fairly simple, and each hypothesis can vary in how detailed it can be. We create if-then hypotheses all the time with our daily predictions. Here are some examples of hypotheses that use an if-then structure from daily life:

- If I get enough sleep, I’ll be able to get more work done tomorrow.

- If the bus is on time, I can make it to my friend’s birthday party.

- If I study every night this week, I’ll get a better grade on my exam.

In each of these situations, you’re making a guess on how an independent variable (sleep, time, or studying) will affect a dependent variable (the amount of work you can do, making it to a party on time, or getting better grades).

You may still be asking, “What is an example of a hypothesis used in scientific research?” Take one of the hypothesis examples from a real-world study on whether using technology before bed affects children’s sleep patterns. The hypothesis read s:

“We hypothesized that increased hours of tablet- and phone-based screen time at bedtime would be inversely correlated with sleep quality and child attention.”

It might not look like it, but this is an if-then statement. The researchers basically said, “If children have more screen usage at bedtime, then their quality of sleep and attention will be worse.” The sleep quality and attention are the dependent variables and the screen usage is the independent variable. (Usually, the independent variable comes after the “if” and the dependent variable comes after the “then,” as it is the independent variable that affects the dependent variable.) This is an excellent example of how flexible hypothesis statements can be, as long as the general idea of “if-then” and the independent and dependent variables are present.

#2: Null Hypotheses

Your if-then hypothesis is not the only one needed to complete a successful experiment, however. You also need a null hypothesis to test it against. In its most basic form, the null hypothesis is the opposite of your if-then hypothesis . When you write your null hypothesis, you are writing a hypothesis that suggests that your guess is not true, and that the independent and dependent variables have no relationship .

One null hypothesis for the cell phone and sleep study from the last section might say:

“If children have more screen usage at bedtime, their quality of sleep and attention will not be worse.”

In this case, this is a null hypothesis because it’s asking the opposite of the original thesis!

Conversely, if your if-then hypothesis suggests that your two variables have no relationship, then your null hypothesis would suggest that there is one. So, pretend that there is a study that is asking the question, “Does the amount of followers on Instagram influence how long people spend on the app?” The independent variable is the amount of followers, and the dependent variable is the time spent. But if you, as the researcher, don’t think there is a relationship between the number of followers and time spent, you might write an if-then hypothesis that reads:

“If people have many followers on Instagram, they will not spend more time on the app than people who have less.”

In this case, the if-then suggests there isn’t a relationship between the variables. In that case, one of the null hypothesis examples might say:

“If people have many followers on Instagram, they will spend more time on the app than people who have less.”

You then test both the if-then and the null hypothesis to gauge if there is a relationship between the variables, and if so, how much of a relationship.

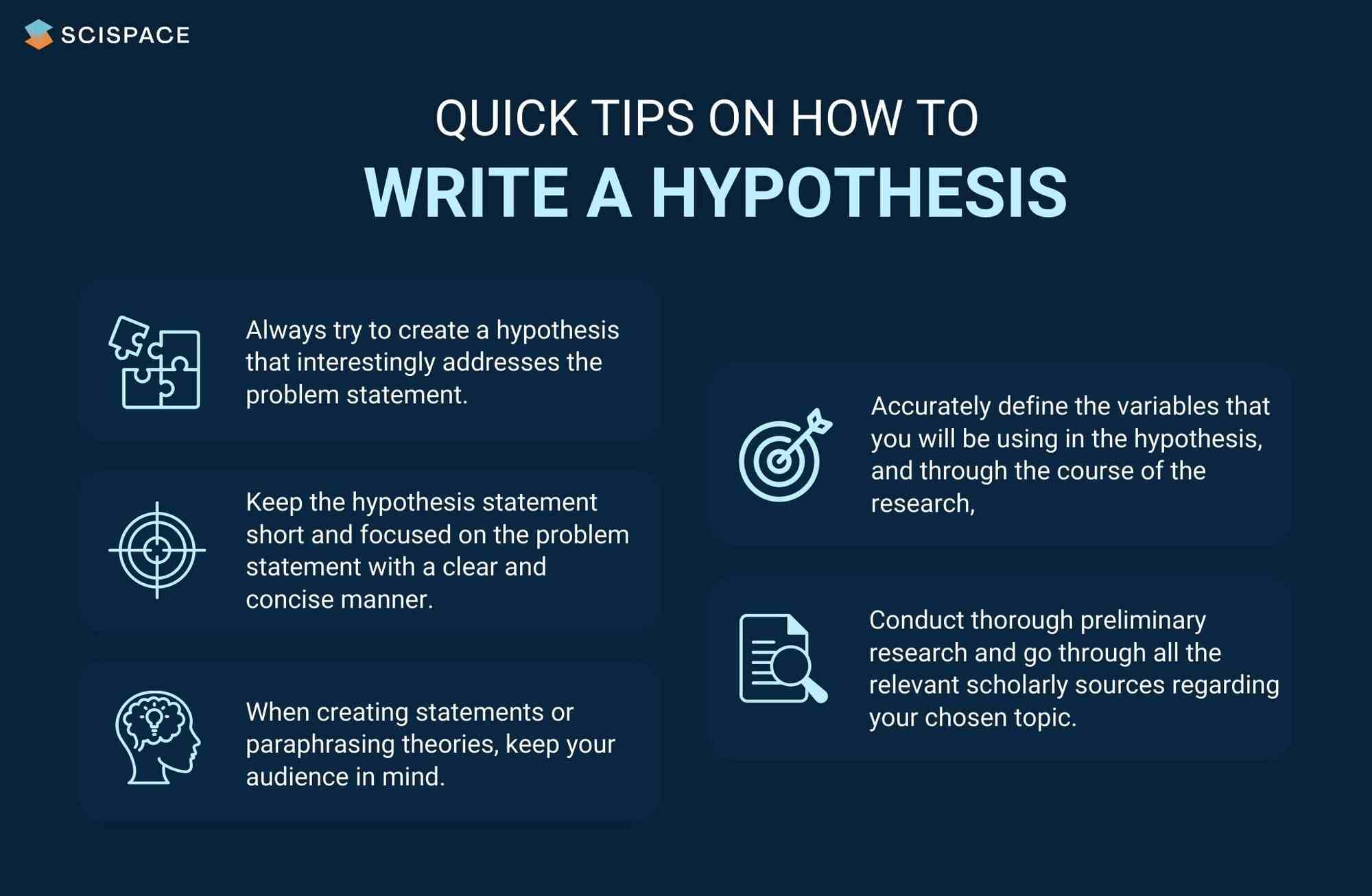

4 Tips to Write the Best Hypothesis

If you’re going to take the time to hold an experiment, whether in school or by yourself, you’re also going to want to take the time to make sure your hypothesis is a good one. The best hypotheses have four major elements in common: plausibility, defined concepts, observability, and general explanation.

#1: Plausibility

At first glance, this quality of a hypothesis might seem obvious. When your hypothesis is plausible, that means it’s possible given what we know about science and general common sense. However, improbable hypotheses are more common than you might think.

Imagine you’re studying weight gain and television watching habits. If you hypothesize that people who watch more than twenty hours of television a week will gain two hundred pounds or more over the course of a year, this might be improbable (though it’s potentially possible). Consequently, c ommon sense can tell us the results of the study before the study even begins.

Improbable hypotheses generally go against science, as well. Take this hypothesis example:

“If a person smokes one cigarette a day, then they will have lungs just as healthy as the average person’s.”

This hypothesis is obviously untrue, as studies have shown again and again that cigarettes negatively affect lung health. You must be careful that your hypotheses do not reflect your own personal opinion more than they do scientifically-supported findings. This plausibility points to the necessity of research before the hypothesis is written to make sure that your hypothesis has not already been disproven.

#2: Defined Concepts

The more advanced you are in your studies, the more likely that the terms you’re using in your hypothesis are specific to a limited set of knowledge. One of the hypothesis testing examples might include the readability of printed text in newspapers, where you might use words like “kerning” and “x-height.” Unless your readers have a background in graphic design, it’s likely that they won’t know what you mean by these terms. Thus, it’s important to either write what they mean in the hypothesis itself or in the report before the hypothesis.

Here’s what we mean. Which of the following sentences makes more sense to the common person?

If the kerning is greater than average, more words will be read per minute.

If the space between letters is greater than average, more words will be read per minute.

For people reading your report that are not experts in typography, simply adding a few more words will be helpful in clarifying exactly what the experiment is all about. It’s always a good idea to make your research and findings as accessible as possible.

Good hypotheses ensure that you can observe the results.

#3: Observability

In order to measure the truth or falsity of your hypothesis, you must be able to see your variables and the way they interact. For instance, if your hypothesis is that the flight patterns of satellites affect the strength of certain television signals, yet you don’t have a telescope to view the satellites or a television to monitor the signal strength, you cannot properly observe your hypothesis and thus cannot continue your study.

Some variables may seem easy to observe, but if you do not have a system of measurement in place, you cannot observe your hypothesis properly. Here’s an example: if you’re experimenting on the effect of healthy food on overall happiness, but you don’t have a way to monitor and measure what “overall happiness” means, your results will not reflect the truth. Monitoring how often someone smiles for a whole day is not reasonably observable, but having the participants state how happy they feel on a scale of one to ten is more observable.

In writing your hypothesis, always keep in mind how you'll execute the experiment.

#4: Generalizability

Perhaps you’d like to study what color your best friend wears the most often by observing and documenting the colors she wears each day of the week. This might be fun information for her and you to know, but beyond you two, there aren’t many people who could benefit from this experiment. When you start an experiment, you should note how generalizable your findings may be if they are confirmed. Generalizability is basically how common a particular phenomenon is to other people’s everyday life.

Let’s say you’re asking a question about the health benefits of eating an apple for one day only, you need to realize that the experiment may be too specific to be helpful. It does not help to explain a phenomenon that many people experience. If you find yourself with too specific of a hypothesis, go back to asking the big question: what is it that you want to know, and what do you think will happen between your two variables?

Hypothesis Testing Examples

We know it can be hard to write a good hypothesis unless you’ve seen some good hypothesis examples. We’ve included four hypothesis examples based on some made-up experiments. Use these as templates or launch pads for coming up with your own hypotheses.

Experiment #1: Students Studying Outside (Writing a Hypothesis)

You are a student at PrepScholar University. When you walk around campus, you notice that, when the temperature is above 60 degrees, more students study in the quad. You want to know when your fellow students are more likely to study outside. With this information, how do you make the best hypothesis possible?

You must remember to make additional observations and do secondary research before writing your hypothesis. In doing so, you notice that no one studies outside when it’s 75 degrees and raining, so this should be included in your experiment. Also, studies done on the topic beforehand suggested that students are more likely to study in temperatures less than 85 degrees. With this in mind, you feel confident that you can identify your variables and write your hypotheses:

If-then: “If the temperature in Fahrenheit is less than 60 degrees, significantly fewer students will study outside.”

Null: “If the temperature in Fahrenheit is less than 60 degrees, the same number of students will study outside as when it is more than 60 degrees.”

These hypotheses are plausible, as the temperatures are reasonably within the bounds of what is possible. The number of people in the quad is also easily observable. It is also not a phenomenon specific to only one person or at one time, but instead can explain a phenomenon for a broader group of people.

To complete this experiment, you pick the month of October to observe the quad. Every day (except on the days where it’s raining)from 3 to 4 PM, when most classes have released for the day, you observe how many people are on the quad. You measure how many people come and how many leave. You also write down the temperature on the hour.

After writing down all of your observations and putting them on a graph, you find that the most students study on the quad when it is 70 degrees outside, and that the number of students drops a lot once the temperature reaches 60 degrees or below. In this case, your research report would state that you accept or “failed to reject” your first hypothesis with your findings.

Experiment #2: The Cupcake Store (Forming a Simple Experiment)

Let’s say that you work at a bakery. You specialize in cupcakes, and you make only two colors of frosting: yellow and purple. You want to know what kind of customers are more likely to buy what kind of cupcake, so you set up an experiment. Your independent variable is the customer’s gender, and the dependent variable is the color of the frosting. What is an example of a hypothesis that might answer the question of this study?

Here’s what your hypotheses might look like:

If-then: “If customers’ gender is female, then they will buy more yellow cupcakes than purple cupcakes.”

Null: “If customers’ gender is female, then they will be just as likely to buy purple cupcakes as yellow cupcakes.”

This is a pretty simple experiment! It passes the test of plausibility (there could easily be a difference), defined concepts (there’s nothing complicated about cupcakes!), observability (both color and gender can be easily observed), and general explanation ( this would potentially help you make better business decisions ).

Experiment #3: Backyard Bird Feeders (Integrating Multiple Variables and Rejecting the If-Then Hypothesis)

While watching your backyard bird feeder, you realized that different birds come on the days when you change the types of seeds. You decide that you want to see more cardinals in your backyard, so you decide to see what type of food they like the best and set up an experiment.

However, one morning, you notice that, while some cardinals are present, blue jays are eating out of your backyard feeder filled with millet. You decide that, of all of the other birds, you would like to see the blue jays the least. This means you'll have more than one variable in your hypothesis. Your new hypotheses might look like this:

If-then: “If sunflower seeds are placed in the bird feeders, then more cardinals will come than blue jays. If millet is placed in the bird feeders, then more blue jays will come than cardinals.”

Null: “If either sunflower seeds or millet are placed in the bird, equal numbers of cardinals and blue jays will come.”

Through simple observation, you actually find that cardinals come as often as blue jays when sunflower seeds or millet is in the bird feeder. In this case, you would reject your “if-then” hypothesis and “fail to reject” your null hypothesis . You cannot accept your first hypothesis, because it’s clearly not true. Instead you found that there was actually no relation between your different variables. Consequently, you would need to run more experiments with different variables to see if the new variables impact the results.

Experiment #4: In-Class Survey (Including an Alternative Hypothesis)

You’re about to give a speech in one of your classes about the importance of paying attention. You want to take this opportunity to test a hypothesis you’ve had for a while:

If-then: If students sit in the first two rows of the classroom, then they will listen better than students who do not.

Null: If students sit in the first two rows of the classroom, then they will not listen better or worse than students who do not.

You give your speech and then ask your teacher if you can hand out a short survey to the class. On the survey, you’ve included questions about some of the topics you talked about. When you get back the results, you’re surprised to see that not only do the students in the first two rows not pay better attention, but they also scored worse than students in other parts of the classroom! Here, both your if-then and your null hypotheses are not representative of your findings. What do you do?

This is when you reject both your if-then and null hypotheses and instead create an alternative hypothesis . This type of hypothesis is used in the rare circumstance that neither of your hypotheses is able to capture your findings . Now you can use what you’ve learned to draft new hypotheses and test again!

Key Takeaways: Hypothesis Writing

The more comfortable you become with writing hypotheses, the better they will become. The structure of hypotheses is flexible and may need to be changed depending on what topic you are studying. The most important thing to remember is the purpose of your hypothesis and the difference between the if-then and the null . From there, in forming your hypothesis, you should constantly be asking questions, making observations, doing secondary research, and considering your variables. After you have written your hypothesis, be sure to edit it so that it is plausible, clearly defined, observable, and helpful in explaining a general phenomenon.

Writing a hypothesis is something that everyone, from elementary school children competing in a science fair to professional scientists in a lab, needs to know how to do. Hypotheses are vital in experiments and in properly executing the scientific method . When done correctly, hypotheses will set up your studies for success and help you to understand the world a little better, one experiment at a time.

What’s Next?

If you’re studying for the science portion of the ACT, there’s definitely a lot you need to know. We’ve got the tools to help, though! Start by checking out our ultimate study guide for the ACT Science subject test. Once you read through that, be sure to download our recommended ACT Science practice tests , since they’re one of the most foolproof ways to improve your score. (And don’t forget to check out our expert guide book , too.)

If you love science and want to major in a scientific field, you should start preparing in high school . Here are the science classes you should take to set yourself up for success.

If you’re trying to think of science experiments you can do for class (or for a science fair!), here’s a list of 37 awesome science experiments you can do at home

Ashley Sufflé Robinson has a Ph.D. in 19th Century English Literature. As a content writer for PrepScholar, Ashley is passionate about giving college-bound students the in-depth information they need to get into the school of their dreams.

Student and Parent Forum

Our new student and parent forum, at ExpertHub.PrepScholar.com , allow you to interact with your peers and the PrepScholar staff. See how other students and parents are navigating high school, college, and the college admissions process. Ask questions; get answers.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Shona McCombes .

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more variables . An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls. A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Step 1: ask a question.

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

Step 2: Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalise more complex constructs.

Step 3: Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

Step 4: Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

Step 5: Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if … then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

Step 6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

A hypothesis is not just a guess. It should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (‘ x affects y because …’).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses. In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, May 06). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 22 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/hypothesis-writing/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, operationalisation | a guide with examples, pros & cons, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples.

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

The Craft of Writing a Strong Hypothesis

Table of Contents

Writing a hypothesis is one of the essential elements of a scientific research paper. It needs to be to the point, clearly communicating what your research is trying to accomplish. A blurry, drawn-out, or complexly-structured hypothesis can confuse your readers. Or worse, the editor and peer reviewers.

A captivating hypothesis is not too intricate. This blog will take you through the process so that, by the end of it, you have a better idea of how to convey your research paper's intent in just one sentence.

What is a Hypothesis?

The first step in your scientific endeavor, a hypothesis, is a strong, concise statement that forms the basis of your research. It is not the same as a thesis statement , which is a brief summary of your research paper .

The sole purpose of a hypothesis is to predict your paper's findings, data, and conclusion. It comes from a place of curiosity and intuition . When you write a hypothesis, you're essentially making an educated guess based on scientific prejudices and evidence, which is further proven or disproven through the scientific method.

The reason for undertaking research is to observe a specific phenomenon. A hypothesis, therefore, lays out what the said phenomenon is. And it does so through two variables, an independent and dependent variable.

The independent variable is the cause behind the observation, while the dependent variable is the effect of the cause. A good example of this is “mixing red and blue forms purple.” In this hypothesis, mixing red and blue is the independent variable as you're combining the two colors at your own will. The formation of purple is the dependent variable as, in this case, it is conditional to the independent variable.

Different Types of Hypotheses

Types of hypotheses

Some would stand by the notion that there are only two types of hypotheses: a Null hypothesis and an Alternative hypothesis. While that may have some truth to it, it would be better to fully distinguish the most common forms as these terms come up so often, which might leave you out of context.

Apart from Null and Alternative, there are Complex, Simple, Directional, Non-Directional, Statistical, and Associative and casual hypotheses. They don't necessarily have to be exclusive, as one hypothesis can tick many boxes, but knowing the distinctions between them will make it easier for you to construct your own.

1. Null hypothesis

A null hypothesis proposes no relationship between two variables. Denoted by H 0 , it is a negative statement like “Attending physiotherapy sessions does not affect athletes' on-field performance.” Here, the author claims physiotherapy sessions have no effect on on-field performances. Even if there is, it's only a coincidence.

2. Alternative hypothesis

Considered to be the opposite of a null hypothesis, an alternative hypothesis is donated as H1 or Ha. It explicitly states that the dependent variable affects the independent variable. A good alternative hypothesis example is “Attending physiotherapy sessions improves athletes' on-field performance.” or “Water evaporates at 100 °C. ” The alternative hypothesis further branches into directional and non-directional.

- Directional hypothesis: A hypothesis that states the result would be either positive or negative is called directional hypothesis. It accompanies H1 with either the ‘<' or ‘>' sign.

- Non-directional hypothesis: A non-directional hypothesis only claims an effect on the dependent variable. It does not clarify whether the result would be positive or negative. The sign for a non-directional hypothesis is ‘≠.'

3. Simple hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement made to reflect the relation between exactly two variables. One independent and one dependent. Consider the example, “Smoking is a prominent cause of lung cancer." The dependent variable, lung cancer, is dependent on the independent variable, smoking.

4. Complex hypothesis

In contrast to a simple hypothesis, a complex hypothesis implies the relationship between multiple independent and dependent variables. For instance, “Individuals who eat more fruits tend to have higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.” The independent variable is eating more fruits, while the dependent variables are higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.

5. Associative and casual hypothesis

Associative and casual hypotheses don't exhibit how many variables there will be. They define the relationship between the variables. In an associative hypothesis, changing any one variable, dependent or independent, affects others. In a casual hypothesis, the independent variable directly affects the dependent.

6. Empirical hypothesis

Also referred to as the working hypothesis, an empirical hypothesis claims a theory's validation via experiments and observation. This way, the statement appears justifiable and different from a wild guess.

Say, the hypothesis is “Women who take iron tablets face a lesser risk of anemia than those who take vitamin B12.” This is an example of an empirical hypothesis where the researcher the statement after assessing a group of women who take iron tablets and charting the findings.

7. Statistical hypothesis

The point of a statistical hypothesis is to test an already existing hypothesis by studying a population sample. Hypothesis like “44% of the Indian population belong in the age group of 22-27.” leverage evidence to prove or disprove a particular statement.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

Writing a hypothesis is essential as it can make or break your research for you. That includes your chances of getting published in a journal. So when you're designing one, keep an eye out for these pointers:

- A research hypothesis has to be simple yet clear to look justifiable enough.

- It has to be testable — your research would be rendered pointless if too far-fetched into reality or limited by technology.

- It has to be precise about the results —what you are trying to do and achieve through it should come out in your hypothesis.

- A research hypothesis should be self-explanatory, leaving no doubt in the reader's mind.

- If you are developing a relational hypothesis, you need to include the variables and establish an appropriate relationship among them.

- A hypothesis must keep and reflect the scope for further investigations and experiments.

Separating a Hypothesis from a Prediction

Outside of academia, hypothesis and prediction are often used interchangeably. In research writing, this is not only confusing but also incorrect. And although a hypothesis and prediction are guesses at their core, there are many differences between them.

A hypothesis is an educated guess or even a testable prediction validated through research. It aims to analyze the gathered evidence and facts to define a relationship between variables and put forth a logical explanation behind the nature of events.

Predictions are assumptions or expected outcomes made without any backing evidence. They are more fictionally inclined regardless of where they originate from.

For this reason, a hypothesis holds much more weight than a prediction. It sticks to the scientific method rather than pure guesswork. "Planets revolve around the Sun." is an example of a hypothesis as it is previous knowledge and observed trends. Additionally, we can test it through the scientific method.

Whereas "COVID-19 will be eradicated by 2030." is a prediction. Even though it results from past trends, we can't prove or disprove it. So, the only way this gets validated is to wait and watch if COVID-19 cases end by 2030.

Finally, How to Write a Hypothesis

Quick tips on writing a hypothesis

1. Be clear about your research question

A hypothesis should instantly address the research question or the problem statement. To do so, you need to ask a question. Understand the constraints of your undertaken research topic and then formulate a simple and topic-centric problem. Only after that can you develop a hypothesis and further test for evidence.

2. Carry out a recce

Once you have your research's foundation laid out, it would be best to conduct preliminary research. Go through previous theories, academic papers, data, and experiments before you start curating your research hypothesis. It will give you an idea of your hypothesis's viability or originality.

Making use of references from relevant research papers helps draft a good research hypothesis. SciSpace Discover offers a repository of over 270 million research papers to browse through and gain a deeper understanding of related studies on a particular topic. Additionally, you can use SciSpace Copilot , your AI research assistant, for reading any lengthy research paper and getting a more summarized context of it. A hypothesis can be formed after evaluating many such summarized research papers. Copilot also offers explanations for theories and equations, explains paper in simplified version, allows you to highlight any text in the paper or clip math equations and tables and provides a deeper, clear understanding of what is being said. This can improve the hypothesis by helping you identify potential research gaps.

3. Create a 3-dimensional hypothesis

Variables are an essential part of any reasonable hypothesis. So, identify your independent and dependent variable(s) and form a correlation between them. The ideal way to do this is to write the hypothetical assumption in the ‘if-then' form. If you use this form, make sure that you state the predefined relationship between the variables.

In another way, you can choose to present your hypothesis as a comparison between two variables. Here, you must specify the difference you expect to observe in the results.

4. Write the first draft

Now that everything is in place, it's time to write your hypothesis. For starters, create the first draft. In this version, write what you expect to find from your research.

Clearly separate your independent and dependent variables and the link between them. Don't fixate on syntax at this stage. The goal is to ensure your hypothesis addresses the issue.

5. Proof your hypothesis

After preparing the first draft of your hypothesis, you need to inspect it thoroughly. It should tick all the boxes, like being concise, straightforward, relevant, and accurate. Your final hypothesis has to be well-structured as well.

Research projects are an exciting and crucial part of being a scholar. And once you have your research question, you need a great hypothesis to begin conducting research. Thus, knowing how to write a hypothesis is very important.

Now that you have a firmer grasp on what a good hypothesis constitutes, the different kinds there are, and what process to follow, you will find it much easier to write your hypothesis, which ultimately helps your research.

Now it's easier than ever to streamline your research workflow with SciSpace Discover . Its integrated, comprehensive end-to-end platform for research allows scholars to easily discover, write and publish their research and fosters collaboration.

It includes everything you need, including a repository of over 270 million research papers across disciplines, SEO-optimized summaries and public profiles to show your expertise and experience.

If you found these tips on writing a research hypothesis useful, head over to our blog on Statistical Hypothesis Testing to learn about the top researchers, papers, and institutions in this domain.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. what is the definition of hypothesis.

According to the Oxford dictionary, a hypothesis is defined as “An idea or explanation of something that is based on a few known facts, but that has not yet been proved to be true or correct”.

2. What is an example of hypothesis?

The hypothesis is a statement that proposes a relationship between two or more variables. An example: "If we increase the number of new users who join our platform by 25%, then we will see an increase in revenue."

3. What is an example of null hypothesis?

A null hypothesis is a statement that there is no relationship between two variables. The null hypothesis is written as H0. The null hypothesis states that there is no effect. For example, if you're studying whether or not a particular type of exercise increases strength, your null hypothesis will be "there is no difference in strength between people who exercise and people who don't."

4. What are the types of research?

• Fundamental research

• Applied research

• Qualitative research

• Quantitative research

• Mixed research

• Exploratory research

• Longitudinal research

• Cross-sectional research

• Field research

• Laboratory research

• Fixed research

• Flexible research

• Action research

• Policy research

• Classification research

• Comparative research

• Causal research

• Inductive research

• Deductive research

5. How to write a hypothesis?

• Your hypothesis should be able to predict the relationship and outcome.

• Avoid wordiness by keeping it simple and brief.

• Your hypothesis should contain observable and testable outcomes.

• Your hypothesis should be relevant to the research question.

6. What are the 2 types of hypothesis?

• Null hypotheses are used to test the claim that "there is no difference between two groups of data".

• Alternative hypotheses test the claim that "there is a difference between two data groups".

7. Difference between research question and research hypothesis?

A research question is a broad, open-ended question you will try to answer through your research. A hypothesis is a statement based on prior research or theory that you expect to be true due to your study. Example - Research question: What are the factors that influence the adoption of the new technology? Research hypothesis: There is a positive relationship between age, education and income level with the adoption of the new technology.

8. What is plural for hypothesis?

The plural of hypothesis is hypotheses. Here's an example of how it would be used in a statement, "Numerous well-considered hypotheses are presented in this part, and they are supported by tables and figures that are well-illustrated."

9. What is the red queen hypothesis?

The red queen hypothesis in evolutionary biology states that species must constantly evolve to avoid extinction because if they don't, they will be outcompeted by other species that are evolving. Leigh Van Valen first proposed it in 1973; since then, it has been tested and substantiated many times.

10. Who is known as the father of null hypothesis?

The father of the null hypothesis is Sir Ronald Fisher. He published a paper in 1925 that introduced the concept of null hypothesis testing, and he was also the first to use the term itself.

11. When to reject null hypothesis?

You need to find a significant difference between your two populations to reject the null hypothesis. You can determine that by running statistical tests such as an independent sample t-test or a dependent sample t-test. You should reject the null hypothesis if the p-value is less than 0.05.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

Holman Library

Research Guide: Scholarly Journals

- Introduction: Hypothesis/Thesis

- Why Use Scholarly Journals?

- What does "Peer-Reviewed" mean?

- What is *NOT* a Scholarly Journal Article?

- Interlibrary Loan for Journal Articles

- Reading the Citation

- Authors' Credentials

- Literature Review

- Methodology

- Results/Data

- Discussion/Conclusions

- APA Citations for Scholarly Journal Articles

- MLA Citations for Scholarly Journal Articles

Hypothesis or Thesis

Looking for the author's thesis or hypothesis.

The image below shows the part of the scholarly article that shows where the authors are making their argument.

(click on image to enlarge)

- The first few paragraphs of a journal article serve to introduce the topic, to provide the author's hypothesis or thesis, and to indicate why the research was done.

- A thesis or hypothesis is not always clearly labeled; you may need to read through the introductory paragraphs to determine what the authors are proposing.

- << Previous: How to Read a Scholarly Article

- Next: Reading the Citation >>

- Last Updated: Mar 15, 2024 1:18 PM

- URL: https://libguides.greenriver.edu/scholarlyjournals

- Manuscript Preparation

What is and How to Write a Good Hypothesis in Research?

- 4 minute read

- 301.3K views

Table of Contents

One of the most important aspects of conducting research is constructing a strong hypothesis. But what makes a hypothesis in research effective? In this article, we’ll look at the difference between a hypothesis and a research question, as well as the elements of a good hypothesis in research. We’ll also include some examples of effective hypotheses, and what pitfalls to avoid.

What is a Hypothesis in Research?

Simply put, a hypothesis is a research question that also includes the predicted or expected result of the research. Without a hypothesis, there can be no basis for a scientific or research experiment. As such, it is critical that you carefully construct your hypothesis by being deliberate and thorough, even before you set pen to paper. Unless your hypothesis is clearly and carefully constructed, any flaw can have an adverse, and even grave, effect on the quality of your experiment and its subsequent results.

Research Question vs Hypothesis

It’s easy to confuse research questions with hypotheses, and vice versa. While they’re both critical to the Scientific Method, they have very specific differences. Primarily, a research question, just like a hypothesis, is focused and concise. But a hypothesis includes a prediction based on the proposed research, and is designed to forecast the relationship of and between two (or more) variables. Research questions are open-ended, and invite debate and discussion, while hypotheses are closed, e.g. “The relationship between A and B will be C.”

A hypothesis is generally used if your research topic is fairly well established, and you are relatively certain about the relationship between the variables that will be presented in your research. Since a hypothesis is ideally suited for experimental studies, it will, by its very existence, affect the design of your experiment. The research question is typically used for new topics that have not yet been researched extensively. Here, the relationship between different variables is less known. There is no prediction made, but there may be variables explored. The research question can be casual in nature, simply trying to understand if a relationship even exists, descriptive or comparative.

How to Write Hypothesis in Research

Writing an effective hypothesis starts before you even begin to type. Like any task, preparation is key, so you start first by conducting research yourself, and reading all you can about the topic that you plan to research. From there, you’ll gain the knowledge you need to understand where your focus within the topic will lie.

Remember that a hypothesis is a prediction of the relationship that exists between two or more variables. Your job is to write a hypothesis, and design the research, to “prove” whether or not your prediction is correct. A common pitfall is to use judgments that are subjective and inappropriate for the construction of a hypothesis. It’s important to keep the focus and language of your hypothesis objective.

An effective hypothesis in research is clearly and concisely written, and any terms or definitions clarified and defined. Specific language must also be used to avoid any generalities or assumptions.

Use the following points as a checklist to evaluate the effectiveness of your research hypothesis:

- Predicts the relationship and outcome

- Simple and concise – avoid wordiness

- Clear with no ambiguity or assumptions about the readers’ knowledge

- Observable and testable results

- Relevant and specific to the research question or problem

Research Hypothesis Example

Perhaps the best way to evaluate whether or not your hypothesis is effective is to compare it to those of your colleagues in the field. There is no need to reinvent the wheel when it comes to writing a powerful research hypothesis. As you’re reading and preparing your hypothesis, you’ll also read other hypotheses. These can help guide you on what works, and what doesn’t, when it comes to writing a strong research hypothesis.

Here are a few generic examples to get you started.

Eating an apple each day, after the age of 60, will result in a reduction of frequency of physician visits.

Budget airlines are more likely to receive more customer complaints. A budget airline is defined as an airline that offers lower fares and fewer amenities than a traditional full-service airline. (Note that the term “budget airline” is included in the hypothesis.

Workplaces that offer flexible working hours report higher levels of employee job satisfaction than workplaces with fixed hours.

Each of the above examples are specific, observable and measurable, and the statement of prediction can be verified or shown to be false by utilizing standard experimental practices. It should be noted, however, that often your hypothesis will change as your research progresses.

Language Editing Plus

Elsevier’s Language Editing Plus service can help ensure that your research hypothesis is well-designed, and articulates your research and conclusions. Our most comprehensive editing package, you can count on a thorough language review by native-English speakers who are PhDs or PhD candidates. We’ll check for effective logic and flow of your manuscript, as well as document formatting for your chosen journal, reference checks, and much more.

- Research Process

Systematic Literature Review or Literature Review?

What is a Problem Statement? [with examples]

You may also like.

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

The Essentials of Writing to Communicate Research in Medicine

Changing Lines: Sentence Patterns in Academic Writing

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Great Hypothesis

Hypothesis Definition, Format, Examples, and Tips

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Alex Dos Diaz

- The Scientific Method

Hypothesis Format

Falsifiability of a hypothesis.

- Operationalization

Hypothesis Types

Hypotheses examples.

- Collecting Data

A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. It is a preliminary answer to your question that helps guide the research process.

Consider a study designed to examine the relationship between sleep deprivation and test performance. The hypothesis might be: "This study is designed to assess the hypothesis that sleep-deprived people will perform worse on a test than individuals who are not sleep-deprived."

At a Glance

A hypothesis is crucial to scientific research because it offers a clear direction for what the researchers are looking to find. This allows them to design experiments to test their predictions and add to our scientific knowledge about the world. This article explores how a hypothesis is used in psychology research, how to write a good hypothesis, and the different types of hypotheses you might use.

The Hypothesis in the Scientific Method

In the scientific method , whether it involves research in psychology, biology, or some other area, a hypothesis represents what the researchers think will happen in an experiment. The scientific method involves the following steps:

- Forming a question

- Performing background research

- Creating a hypothesis

- Designing an experiment

- Collecting data

- Analyzing the results

- Drawing conclusions

- Communicating the results

The hypothesis is a prediction, but it involves more than a guess. Most of the time, the hypothesis begins with a question which is then explored through background research. At this point, researchers then begin to develop a testable hypothesis.

Unless you are creating an exploratory study, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen.

In a study exploring the effects of a particular drug, the hypothesis might be that researchers expect the drug to have some type of effect on the symptoms of a specific illness. In psychology, the hypothesis might focus on how a certain aspect of the environment might influence a particular behavior.

Remember, a hypothesis does not have to be correct. While the hypothesis predicts what the researchers expect to see, the goal of the research is to determine whether this guess is right or wrong. When conducting an experiment, researchers might explore numerous factors to determine which ones might contribute to the ultimate outcome.

In many cases, researchers may find that the results of an experiment do not support the original hypothesis. When writing up these results, the researchers might suggest other options that should be explored in future studies.

In many cases, researchers might draw a hypothesis from a specific theory or build on previous research. For example, prior research has shown that stress can impact the immune system. So a researcher might hypothesize: "People with high-stress levels will be more likely to contract a common cold after being exposed to the virus than people who have low-stress levels."

In other instances, researchers might look at commonly held beliefs or folk wisdom. "Birds of a feather flock together" is one example of folk adage that a psychologist might try to investigate. The researcher might pose a specific hypothesis that "People tend to select romantic partners who are similar to them in interests and educational level."

Elements of a Good Hypothesis

So how do you write a good hypothesis? When trying to come up with a hypothesis for your research or experiments, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is your hypothesis based on your research on a topic?

- Can your hypothesis be tested?

- Does your hypothesis include independent and dependent variables?

Before you come up with a specific hypothesis, spend some time doing background research. Once you have completed a literature review, start thinking about potential questions you still have. Pay attention to the discussion section in the journal articles you read . Many authors will suggest questions that still need to be explored.

How to Formulate a Good Hypothesis

To form a hypothesis, you should take these steps:

- Collect as many observations about a topic or problem as you can.

- Evaluate these observations and look for possible causes of the problem.

- Create a list of possible explanations that you might want to explore.

- After you have developed some possible hypotheses, think of ways that you could confirm or disprove each hypothesis through experimentation. This is known as falsifiability.

In the scientific method , falsifiability is an important part of any valid hypothesis. In order to test a claim scientifically, it must be possible that the claim could be proven false.

Students sometimes confuse the idea of falsifiability with the idea that it means that something is false, which is not the case. What falsifiability means is that if something was false, then it is possible to demonstrate that it is false.

One of the hallmarks of pseudoscience is that it makes claims that cannot be refuted or proven false.

The Importance of Operational Definitions

A variable is a factor or element that can be changed and manipulated in ways that are observable and measurable. However, the researcher must also define how the variable will be manipulated and measured in the study.

Operational definitions are specific definitions for all relevant factors in a study. This process helps make vague or ambiguous concepts detailed and measurable.

For example, a researcher might operationally define the variable " test anxiety " as the results of a self-report measure of anxiety experienced during an exam. A "study habits" variable might be defined by the amount of studying that actually occurs as measured by time.

These precise descriptions are important because many things can be measured in various ways. Clearly defining these variables and how they are measured helps ensure that other researchers can replicate your results.

Replicability

One of the basic principles of any type of scientific research is that the results must be replicable.

Replication means repeating an experiment in the same way to produce the same results. By clearly detailing the specifics of how the variables were measured and manipulated, other researchers can better understand the results and repeat the study if needed.

Some variables are more difficult than others to define. For example, how would you operationally define a variable such as aggression ? For obvious ethical reasons, researchers cannot create a situation in which a person behaves aggressively toward others.

To measure this variable, the researcher must devise a measurement that assesses aggressive behavior without harming others. The researcher might utilize a simulated task to measure aggressiveness in this situation.

Hypothesis Checklist

- Does your hypothesis focus on something that you can actually test?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate the variables?

- Can your hypothesis be tested without violating ethical standards?

The hypothesis you use will depend on what you are investigating and hoping to find. Some of the main types of hypotheses that you might use include:

- Simple hypothesis : This type of hypothesis suggests there is a relationship between one independent variable and one dependent variable.

- Complex hypothesis : This type suggests a relationship between three or more variables, such as two independent and dependent variables.

- Null hypothesis : This hypothesis suggests no relationship exists between two or more variables.

- Alternative hypothesis : This hypothesis states the opposite of the null hypothesis.

- Statistical hypothesis : This hypothesis uses statistical analysis to evaluate a representative population sample and then generalizes the findings to the larger group.

- Logical hypothesis : This hypothesis assumes a relationship between variables without collecting data or evidence.

A hypothesis often follows a basic format of "If {this happens} then {this will happen}." One way to structure your hypothesis is to describe what will happen to the dependent variable if you change the independent variable .

The basic format might be: "If {these changes are made to a certain independent variable}, then we will observe {a change in a specific dependent variable}."

A few examples of simple hypotheses:

- "Students who eat breakfast will perform better on a math exam than students who do not eat breakfast."

- "Students who experience test anxiety before an English exam will get lower scores than students who do not experience test anxiety."

- "Motorists who talk on the phone while driving will be more likely to make errors on a driving course than those who do not talk on the phone."

- "Children who receive a new reading intervention will have higher reading scores than students who do not receive the intervention."

Examples of a complex hypothesis include:

- "People with high-sugar diets and sedentary activity levels are more likely to develop depression."

- "Younger people who are regularly exposed to green, outdoor areas have better subjective well-being than older adults who have limited exposure to green spaces."

Examples of a null hypothesis include:

- "There is no difference in anxiety levels between people who take St. John's wort supplements and those who do not."

- "There is no difference in scores on a memory recall task between children and adults."

- "There is no difference in aggression levels between children who play first-person shooter games and those who do not."

Examples of an alternative hypothesis:

- "People who take St. John's wort supplements will have less anxiety than those who do not."

- "Adults will perform better on a memory task than children."

- "Children who play first-person shooter games will show higher levels of aggression than children who do not."

Collecting Data on Your Hypothesis

Once a researcher has formed a testable hypothesis, the next step is to select a research design and start collecting data. The research method depends largely on exactly what they are studying. There are two basic types of research methods: descriptive research and experimental research.

Descriptive Research Methods

Descriptive research such as case studies , naturalistic observations , and surveys are often used when conducting an experiment is difficult or impossible. These methods are best used to describe different aspects of a behavior or psychological phenomenon.

Once a researcher has collected data using descriptive methods, a correlational study can examine how the variables are related. This research method might be used to investigate a hypothesis that is difficult to test experimentally.

Experimental Research Methods

Experimental methods are used to demonstrate causal relationships between variables. In an experiment, the researcher systematically manipulates a variable of interest (known as the independent variable) and measures the effect on another variable (known as the dependent variable).

Unlike correlational studies, which can only be used to determine if there is a relationship between two variables, experimental methods can be used to determine the actual nature of the relationship—whether changes in one variable actually cause another to change.

The hypothesis is a critical part of any scientific exploration. It represents what researchers expect to find in a study or experiment. In situations where the hypothesis is unsupported by the research, the research still has value. Such research helps us better understand how different aspects of the natural world relate to one another. It also helps us develop new hypotheses that can then be tested in the future.

Thompson WH, Skau S. On the scope of scientific hypotheses . R Soc Open Sci . 2023;10(8):230607. doi:10.1098/rsos.230607

Taran S, Adhikari NKJ, Fan E. Falsifiability in medicine: what clinicians can learn from Karl Popper [published correction appears in Intensive Care Med. 2021 Jun 17;:]. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47(9):1054-1056. doi:10.1007/s00134-021-06432-z

Eyler AA. Research Methods for Public Health . 1st ed. Springer Publishing Company; 2020. doi:10.1891/9780826182067.0004

Nosek BA, Errington TM. What is replication ? PLoS Biol . 2020;18(3):e3000691. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000691

Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. Study designs: Part 2 - Descriptive studies . Perspect Clin Res . 2019;10(1):34-36. doi:10.4103/picr.PICR_154_18

Nevid J. Psychology: Concepts and Applications. Wadworth, 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Privacy Policy

Home » What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Definition:

Hypothesis is an educated guess or proposed explanation for a phenomenon, based on some initial observations or data. It is a tentative statement that can be tested and potentially proven or disproven through further investigation and experimentation.

Hypothesis is often used in scientific research to guide the design of experiments and the collection and analysis of data. It is an essential element of the scientific method, as it allows researchers to make predictions about the outcome of their experiments and to test those predictions to determine their accuracy.

Types of Hypothesis

Types of Hypothesis are as follows:

Research Hypothesis

A research hypothesis is a statement that predicts a relationship between variables. It is usually formulated as a specific statement that can be tested through research, and it is often used in scientific research to guide the design of experiments.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis is a statement that assumes there is no significant difference or relationship between variables. It is often used as a starting point for testing the research hypothesis, and if the results of the study reject the null hypothesis, it suggests that there is a significant difference or relationship between variables.

Alternative Hypothesis

An alternative hypothesis is a statement that assumes there is a significant difference or relationship between variables. It is often used as an alternative to the null hypothesis and is tested against the null hypothesis to determine which statement is more accurate.

Directional Hypothesis

A directional hypothesis is a statement that predicts the direction of the relationship between variables. For example, a researcher might predict that increasing the amount of exercise will result in a decrease in body weight.

Non-directional Hypothesis

A non-directional hypothesis is a statement that predicts the relationship between variables but does not specify the direction. For example, a researcher might predict that there is a relationship between the amount of exercise and body weight, but they do not specify whether increasing or decreasing exercise will affect body weight.

Statistical Hypothesis

A statistical hypothesis is a statement that assumes a particular statistical model or distribution for the data. It is often used in statistical analysis to test the significance of a particular result.

Composite Hypothesis

A composite hypothesis is a statement that assumes more than one condition or outcome. It can be divided into several sub-hypotheses, each of which represents a different possible outcome.

Empirical Hypothesis

An empirical hypothesis is a statement that is based on observed phenomena or data. It is often used in scientific research to develop theories or models that explain the observed phenomena.

Simple Hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement that assumes only one outcome or condition. It is often used in scientific research to test a single variable or factor.

Complex Hypothesis

A complex hypothesis is a statement that assumes multiple outcomes or conditions. It is often used in scientific research to test the effects of multiple variables or factors on a particular outcome.

Applications of Hypothesis

Hypotheses are used in various fields to guide research and make predictions about the outcomes of experiments or observations. Here are some examples of how hypotheses are applied in different fields:

- Science : In scientific research, hypotheses are used to test the validity of theories and models that explain natural phenomena. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a particular variable on a natural system, such as the effects of climate change on an ecosystem.

- Medicine : In medical research, hypotheses are used to test the effectiveness of treatments and therapies for specific conditions. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a new drug on a particular disease.

- Psychology : In psychology, hypotheses are used to test theories and models of human behavior and cognition. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a particular stimulus on the brain or behavior.

- Sociology : In sociology, hypotheses are used to test theories and models of social phenomena, such as the effects of social structures or institutions on human behavior. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of income inequality on crime rates.

- Business : In business research, hypotheses are used to test the validity of theories and models that explain business phenomena, such as consumer behavior or market trends. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a new marketing campaign on consumer buying behavior.

- Engineering : In engineering, hypotheses are used to test the effectiveness of new technologies or designs. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the efficiency of a new solar panel design.

How to write a Hypothesis

Here are the steps to follow when writing a hypothesis:

Identify the Research Question

The first step is to identify the research question that you want to answer through your study. This question should be clear, specific, and focused. It should be something that can be investigated empirically and that has some relevance or significance in the field.

Conduct a Literature Review

Before writing your hypothesis, it’s essential to conduct a thorough literature review to understand what is already known about the topic. This will help you to identify the research gap and formulate a hypothesis that builds on existing knowledge.

Determine the Variables

The next step is to identify the variables involved in the research question. A variable is any characteristic or factor that can vary or change. There are two types of variables: independent and dependent. The independent variable is the one that is manipulated or changed by the researcher, while the dependent variable is the one that is measured or observed as a result of the independent variable.

Formulate the Hypothesis

Based on the research question and the variables involved, you can now formulate your hypothesis. A hypothesis should be a clear and concise statement that predicts the relationship between the variables. It should be testable through empirical research and based on existing theory or evidence.

Write the Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis is the opposite of the alternative hypothesis, which is the hypothesis that you are testing. The null hypothesis states that there is no significant difference or relationship between the variables. It is important to write the null hypothesis because it allows you to compare your results with what would be expected by chance.

Refine the Hypothesis

After formulating the hypothesis, it’s important to refine it and make it more precise. This may involve clarifying the variables, specifying the direction of the relationship, or making the hypothesis more testable.

Examples of Hypothesis

Here are a few examples of hypotheses in different fields:

- Psychology : “Increased exposure to violent video games leads to increased aggressive behavior in adolescents.”

- Biology : “Higher levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere will lead to increased plant growth.”

- Sociology : “Individuals who grow up in households with higher socioeconomic status will have higher levels of education and income as adults.”

- Education : “Implementing a new teaching method will result in higher student achievement scores.”

- Marketing : “Customers who receive a personalized email will be more likely to make a purchase than those who receive a generic email.”

- Physics : “An increase in temperature will cause an increase in the volume of a gas, assuming all other variables remain constant.”

- Medicine : “Consuming a diet high in saturated fats will increase the risk of developing heart disease.”

Purpose of Hypothesis