How to Write a Monologue: Tips and Examples

Hello, dear readers. So you want to write a monologue? We assume that’s why you’re here. And you’re in the right place! In this article, you’ll learn all about what exactly a monologue is, its purpose in literature and media, and how to write your very own.

Tune in to learn the secrets behind a great monologue.

What Is a Monologue?

Firstly, what exactly is a monologue? And what is its purpose? There are different types of monologue that you may wish to know about before deciding which kind you will write. Let's dive in.

Definition of Monologue

A monologue is a lengthy, uninterrupted speech, spoken by a single character in theatre plays, novels, movies, television, or essentially, any media that uses actors. That is why, for the purposes of this article, we will use the terms ‘audience’, ‘listener’, ‘viewer’, and ‘reader’ interchangeably to refer to the intended audience of your monologue.

We’ll also use the terms ‘watch’, ‘listen’, and ‘read’ interchangeably, to refer to the concept of written material enjoyed in any format.

The word ‘monologue’ comes from the Greek words ‘monos’ and ‘logos’, meaning ‘alone’ and ‘speech’ respectively.

What is the Purpose of a Monologue?

Monologues tend to be used to give the audience more information about the story or the character’s thoughts, personality, or motivations. They give a glimpse into the character’s thought process when making a decision, which helps us, the audience, make sense of that decision.

A monologue also invites viewers, listeners, and readers into the speaker’s mind and gives them a glimpse of their true nature. Just in the same way, we can’t truly get to know someone unless they let us in on their innermost thoughts and, sometimes, secrets, our knowledge of a fictional character would remain limited if it weren’t for monologues giving us some insight.

Monologues can also be used to move the story forward. Indeed, telling part of a story through speech instead of scenes can save time and explain in more detail what has happened, in a way that imagery or dialogue couldn’t.

A monologue is also a great way to pack a lot of information into a scene, in a way that dialogue might not allow, due to the back and forth of the speech between characters and perhaps, at times, the unwillingness of the characters to reveal some information to one another.

Generally, the information given in a speech usually cannot be given in dialogue - at least not in the same way - and this is the reason why monologues exist. Remember this, as it will be important to take into consideration when you come to write your monologue, as we will come to explain in a later section.

Types of Monologue

Here are the following types of monologues:

A soliloquy is a type of monologue given by a character who assumes nobody is listening to them. They are speaking to themselves, rather than to another character or the audience.

Soliloquies give a privileged insight into a character’s thoughts, and can therefore be used to explain some of their choices, motivations, or actions.

Since the character delivering the soliloquy is unaware that anyone can hear them, they tend to reveal pretty personal and private information in these monologues. Of course, the audience can hear them, and sometimes another character might also be listening secretly.

The famous To Be Or Not To Be by William Shakespeare is an example of a soliloquy. Hamlet delivers this speech without intending for anyone to hear it. It’s a lament of his feelings.

Dramatic monologue

A dramatic monologue is quite the opposite of a soliloquy. Indeed, this type is a speech given by a character, with the intention of another character and/or the audience of hearing it.

When you watch the President’s speech on TV, for example, you are watching a dramatic monologue.

A character will usually deliver a dramatic monologue to reveal specific intentions.

Interior monologue

An interior monologue gives the audience access to the character’s stream of consciousness. The character is aware that the audience is listening, and they are delivering the speech to confess their thoughts and feelings to them, or to give the audience an essential part of information.

The difference is that, unlike a dramatic monologue, the character isn’t speaking directly to the audience.

They fill in the blanks and provide the reader, listener, or viewer with a clearer picture of what’s going on.

For example, you might hear an interior monologue in between scenes during a movie or a sitcom.

Fight Club is a great example of interior monologues. It is full of them throughout the movie, with Edward Norton as the narrator, giving us some insight into his thoughts, which, as it turns out, ends up playing an essential role in understanding the story. Without this ongoing interior monologue, the story wouldn't make sense.

Origins of Monologues

Drama as we know it evolved from Greek theatre, which started as long ago as 700 BC. Originally, it consisted mostly of monologues and did not contain much acting or dialogue between characters.

It evolved into more complex setups: now more characters were being added in to play out the storyline, and dialogues between characters were helping to carry the story forward. But even then, monologues were invaluable in helping transmit parts of the story to the audience.

Imagine, for example, having to relay to the audience that years have gone by, and the man has departed on his travels, and the woman in the meantime got pregnant unexpectedly. All of this on a small stage in 500 BC. Of course, this could also be done using signs or acting, but it would be much easier to explain with a monologue, don’t you think?

How to Write a Monologue

Are you ready to get onto the juicy bit? It’s time to write your own monologue. Whether you’re writing for a theatre play, a movie, a novel, a speech on TV, or any other medium, the following tips will help you in your endeavor.

Get Your Timing Right When You Write a Monologue

If you’re writing a monologue with the purpose of it being part of a bigger piece of writing, then timing is everything. If you don’t place it correctly, it could feel a little forced, or come across as fake to your audience. Or, quite simply, it might not deliver the dramatic effect you’d like it to.

You could place your monologue at the beginning or end of the scene or movie, or you could strategically place it at another crucial moment.

Thinking about your monologue’s purpose will help you decide the optimal time for your character to deliver their monologue.

A monologue at the beginning

Having a character deliver a monologue at the beginning of a scene, movie, act or chapter can help set the mood and tone for what’s to come. This can be useful if you want to implement a sudden change in tone, for example. Or if you want to introduce an unexpected side to a character.

Think of Henry Hill’s monologue at the start of Goodfellas. This iconic speech gives an introduction to one of the main characters, and immediate insight into his way of thinking, as well as his hopes and desires.

A monologue at the end

A monologue at the end of a scene helps summarize, emphasize the moral, or end on a particular note.

Think of Red’s parole monologue at the end of the immensely popular movie The Shawshank Redemption . It brings together the moral of the story by expressing the lessons Red has learned from his time in prison.

This monologue cleverly gives us insight into the meaning he has derived from his countless dialogues with other characters throughout the movie, as well as his experiences, all of which we have been witness to. This speech has a strong impact on the audience and leaves us feeling a particular way - as per the writer’s intentions.

A monologue as a transition

Monologues, as we have mentioned already, are a good way to mark a transition between two ideas. If you’re using a monologue for this purpose, then there aren’t any rules around where exactly you should place it. This comes down to your judgment.

Placement is still important. It is essential to place it somewhere that makes sense. Even more so if it’s a monologue serving as a transition since placing it in the middle of a scene can really interrupt the flow if it isn’t done naturally. Don’t get us wrong, you can have a monologue in the middle of a scene - if it makes sense.

Know Your Monologue’s Purpose

As has been mentioned earlier, a monologue must be used to do something a dialogue cannot. Otherwise, it will seem ill-placed and forced, and the audience will wonder why you’re using a monologue as opposed to another type of speech. So ask yourself, when your monologue is written - could this have been better communicated in a dialogue? If so, your monologue needs to be stronger.

A monologue can carry so much power. The best ones give us goosebumps as there are high stakes involved. Think of Buffy the Vampire Slayer delivering a long speech to her Scooby Gang about why they can defeat the big bad - even though this one is scarier and stronger than any other before.

Or take Sean Maguire’s speech about love and loss in the iconic Good Will Hunting. It is highly impactful - on the viewers, as well as Matt Damon’s character Will.

Another great monologue is Lester’s speech in American Beauty about how time stretches right before you die, which is delivered as he is about to die.

These monologues are notorious and will be remembered always, because of the emotions they elicited.

Be deliberate about your monologue’s purpose, and determine what it will be before you begin writing it. As discussed earlier, the purpose will also determine where it goes in your scene/movie if you are indeed writing one.

Knowing your monologue’s purpose will help it to fit seamlessly into the scene, and the overall evolution of the story will flow. It will also help you decide which type of monologue it should be - dramatic, soliloquy, or interior.

Give Your Monologue Structure

A clear beginning, middle, and end are essential parts of a monologue. You can almost think of a monologue as a standalone piece of writing. In fact, sometimes it is. Perhaps you’re here because you just want to write a monologue that will stand alone. In any case, the monologue should begin and end with a specific purpose.

Usually, the ending will be some sort of revelation on the speaker’s part. If the purpose of the monologue was for the character to have an internal struggle around which action to take, then the monologue might end with a decision.

If the monologue was telling a story about the character’s past, the end might explain how this impacts them today.

Choose the Right Length For Your Monologue

A monologue can be any length, as long as you follow the above rules. The length is less important than what the monologue is accomplishing and how well it is doing it. You could lose your reader/viewer within the first few sentences if the monologue is boring. Conversely, an enthralling and well-written monologue can keep the reader engaged for paragraphs or hours at a time (depending on the medium).

If your monologue is intended for an audiovisual medium, after writing it, it can be a good idea to perform it out loud the way you would like it to be performed by the actor - conveying the right emotions and taking the relevant pauses in speech. This is because a monologue can last for longer when spoken than it seems when being read in your head.

Of course, if you’re writing a monologue only, as opposed to a monologue that will fit into a broader picture (movie, book, etc.) then it’s likely to be somewhat longer since the entire performance rests on this monologue. Again, that isn’t a problem, it just raises the stakes in terms of keeping the listener engaged. Think about why they would want to listen to you if they don’t know anything about you/your character. And if they do know you, what more might they want to know?

Start to Write a Monologue With a Hook

You should spike the reader’s curiosity from the very beginning of the speech so that the listener will want to pay attention until the end. Here are a few ways you can do that.

- Use humor when you write a monologue: People love to laugh. Opening with humor is a great way to get people engaged and wanting more. Humor done well is usually a winner. If you’d like to know more about that, check out our recent article on writing comedy .

- Resonate with the audience: If they feel like you get them, your audience will be more than happy to stick around. Start with something they can resonate with.

- Inject an element of surprise: Try saying something a little controversial or challenging. The audience won’t expect it and they’ll be curious to see where you’re going. So make sure you are going somewhere with it.

- Get emotional: People like the idea that there’s something bigger at play. There’s always a way to make your topic tap into something larger than what it first appears to be.

What Makes a Good Monologue?

Now’s the time to edit and rewrite what needs to be improved upon. Remember, writing is a process. You aren’t expected to get it right the first time. Many drafts will be required, and that’s okay. Have fun with your monologue. Workshop it. Get ideas from friends.

Here are some tips to check if your monologue can hold its ground. You can use these tips to check in at different stages of your writing process, or when you’re done writing and are ready to make some tweaks.

Can it Stand Alone?

Ask yourself: if you take your monologue out of context, will it stand on its own pretty well? If the answer is yes, there’s a good chance your monologue is of high quality.

Since a monologue needs a clear beginning and end, as explained earlier, it can usually stand alone and make perfect sense.

Does it Add to the Story?

Despite being able to stand alone, within the intended context it adds fresh details to the story. So this is another element of a good quality monologue. It reveals something new to the audience.

Maybe it’s some juicy info that they didn’t know about a character. Maybe it raises the stakes. Maybe it makes the audience care more. Whatever it is, it grips the listener and keeps them hooked until the end of the monologue.

Character Profile and Character Development When You Write a Monologue

Your characters must act in a way the audience expects them to. Think of how a real person would act. Sure, we sometimes act out of character, but mostly we stick to a fairly unchangeable set of values and act in largely predictable ways. Your characters should do the same.

It can help to design character profiles, going into quite a lot of depth around their traits, thoughts, likes and dislikes, hobbies, and so on. Even if you don’t plan to use this information in your story directly, it can help you know your characters like your back pocket. And this in turn will help you write realistic monologues because they paint your character’s thoughts in a way that seems natural.

Even if their monologue is revealing something completely unexpected, the audience won’t question it so long as the character development was leading to this, or if they believe it’s possible in any way.

Does it Flow?

The best way to know if your monologue flows naturally is to perform it out loud. If you can, hire an actor to perform it. This will allow you to take the place of the audience and really listen . Does it grab your attention? Does the character behave in a way and use words that they would be expected to? Is the tone consistent throughout? Does the ending feel natural or is it a little abrupt? Is it long enough? Perhaps it feels too long and some elements can be cut.

There’s no better way for you to know how your monologue will come across to an audience than by putting yourself in the audience’s shoes. Of course, reading it out loud to another person will also help, as they will have the objectivity that you won’t, from hearing the piece for the first time.

How to Get Better at Writing Monologues

If you enjoyed the process of writing a monologue, you may want to write more. That’s great! If you want to get your creative juices flowing, monologues are a great choice because they are so rich and diverse, and there are many directions you can go with it.

It’s important to hone your craft and make sure that you’re improving your skills over time. Here is some advice for you to get better and better at writing monologues.

As they say, practice makes perfect. Keep writing, make it a daily practice. You can find time to write a little each day. Try using writing prompts - you can find these online, or in journals bought specifically for this purpose.

When you practice, you don’t have to practice only writing monologues. Just getting your creative juices flowing will help you. The more you tap into that side of your brain, the more it will become a habit, and the easier inspiration will come.

Speaking of inspiration, try to find it in mundane moments or objects. Pay attention to what’s around you and imagine writing a story about it.

Enjoy the Process When You Write a Monologue

Before, we said, “practice makes perfect”. Of course, there’s no such thing as perfection, especially in the world of creativity, since everyone’s taste is different and art is subjective.

Besides, we don’t recommend that you aim for perfection. Why? Because this will rob you of the joy of the process.

Writer Mark Ronson once said that he used to write with the anticipation of the piece being performed, always thinking ahead. Then when he got his piece to the stage and he was finally “there”, he had “made it”, he would realize that the most enjoyable part of the process was actually the writing.

Moral of the story is? Enjoy each stage when you’re in it. Don’t wish your time away. Don’t dwell on being imperfect or wondering how popular your piece of writing will be. That’s not the most important part. Because the truth is that when you find joy in your writing, this will be felt in your writing, as it will naturally improve.

Learn From the Pros

Watch, read, listen to and mimic the pros. What are they doing? Find out about their daily rituals, and their practices around writing, listen to their advice, and take in their tips.

This applies to writing monologues or writing in general.

You can buy books, watch Ted Talks, listen to podcasts, and take a course; the list of resources to help you improve your writing is endless. Head to reputable sites created by the people who have been there, who are doing it, who are living it, and listen to what they have to say. Learn from their expertise.

Expose Your Mind to Good Writing

There’s no better way to be exposed to good writing than to read good writing. Or watch well-written movies.

Pay attention to the dialogue. Study the writing and see if you can detect patterns. Read/watch the material over and over, join a study group, and dissect the whole thing. Not only is this loads of fun, but it will seriously help improve your writing.

Final Thoughts on How to Write a Monologue

So hopefully by now, you have the tools to write a strong monologue, so what are you waiting for? Get started! We believe in getting started before you feel ready, because the inspiration will come as you are writing, and practice makes perfect.

Remember, above all, to have a lot of fun with it. Having a goal for your monologue is valid, but it isn’t everything. Writing should be a fun and enjoyable process, so make sure not to omit that side of things, too.

Good luck writing your monologue!

Learn More:

- How to Write a Postcard (Tips and Examples)

- How to Write Comedy: Tips and Examples to Make People Laugh

- How to Write Like Ernest Hemingway

- How to Write a Follow-Up Email After an Interview

- How to Write a Formal Email

- 'Master's Student' or 'Masters Student' or 'MS Student': Which is Correct?

- How to Write Height Correctly - Writing Feet and Inches

- How Long Does It Take to Write 1000 Words

- How to Write an Inequality: From Number Lines or Word Problems

- How to Write a Letter to the President (With Example)

- How to Write a 2-Week Notice Email

- How to Write an Out-of-Office (OOO) Email

- How to Write a Professional ‘Thank You’ Email

- How to End an Email (Sign Off Examples)

- How to Sound Polite in Your Emails

We encourage you to share this article on Twitter and Facebook . Just click those two links - you'll see why.

It's important to share the news to spread the truth. Most people won't.

Add new comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post Comment

Related Topics

- How to Write a Book

- Writing a Book for the First Time

- How to Write an Autobiography

- How Long Does it Take to Write a Book?

- Do You Underline Book Titles?

- Snowflake Method

- Book Title Generator

- How to Write Nonfiction Book

- How to Write a Children's Book

- How to Write a Memoir

- Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Book

- How to Write a Book Title

- How to Write a Book Introduction

- How to Write a Dedication in a Book

- How to Write a Book Synopsis

- Author Overview

- Types of Writers

- How to Become a Writer

- Document Manager Overview

- Screenplay Writer Overview

- Technical Writer Career Path

- Technical Writer Interview Questions

- Technical Writer Salary

- Google Technical Writer Interview Questions

- How to Become a Technical Writer

- UX Writer Career Path

- Google UX Writer

- UX Writer vs Copywriter

- UX Writer Resume Examples

- UX Writer Interview Questions

- UX Writer Skills

- How to Become a UX Writer

- UX Writer Salary

- Google UX Writer Overview

- Google UX Writer Interview Questions

- Technical Writing Certifications

- Grant Writing Certifications

- UX Writing Certifications

- Proposal Writing Certifications

- Content Design Certifications

- Knowledge Management Certifications

- Medical Writing Certifications

- Grant Writing Classes

- Business Writing Courses

- Technical Writing Courses

- Content Design Overview

- Documentation Overview

- User Documentation

- Process Documentation

- Technical Documentation

- Software Documentation

- Knowledge Base Documentation

- Product Documentation

- Process Documentation Overview

- Process Documentation Templates

- Product Documentation Overview

- Software Documentation Overview

- Technical Documentation Overview

- User Documentation Overview

- Knowledge Management Overview

- Knowledge Base Overview

- Publishing on Amazon

- Amazon Authoring Page

- Self-Publishing on Amazon

- How to Publish

- How to Publish Your Own Book

- Document Management Software Overview

- Engineering Document Management Software

- Healthcare Document Management Software

- Financial Services Document Management Software

- Technical Documentation Software

- Knowledge Management Tools

- Knowledge Management Software

- HR Document Management Software

- Enterprise Document Management Software

- Knowledge Base Software

- Process Documentation Software

- Documentation Software

- Internal Knowledge Base Software

- Grammarly Premium Free Trial

- Grammarly for Word

- Scrivener Templates

- Scrivener Review

- How to Use Scrivener

- Ulysses vs Scrivener

- Character Development Templates

- Screenplay Format Templates

- Book Writing Templates

- API Writing Overview

- Business Writing Examples

- Business Writing Skills

- Types of Business Writing

- Dialogue Writing Overview

- Grant Writing Overview

- Medical Writing Overview

- How to Write a Novel

- How to Write a Thriller Novel

- How to Write a Fantasy Novel

- How to Start a Novel

- How Many Chapters in a Novel?

- Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Novel

- Novel Ideas

- How to Plan a Novel

- How to Outline a Novel

- How to Write a Romance Novel

- Novel Structure

- How to Write a Mystery Novel

- Novel vs Book

- Round Character

- Flat Character

- How to Create a Character Profile

- Nanowrimo Overview

- How to Write 50,000 Words for Nanowrimo

- Camp Nanowrimo

- Nanowrimo YWP

- Nanowrimo Mistakes to Avoid

- Proposal Writing Overview

- Screenplay Overview

- How to Write a Screenplay

- Screenplay vs Script

- How to Structure a Screenplay

- How to Write a Screenplay Outline

- How to Format a Screenplay

- How to Write a Fight Scene

- How to Write Action Scenes

- How to Write a Monologue

- Short Story Writing Overview

- Technical Writing Overview

- UX Writing Overview

- Reddit Writing Prompts

- Romance Writing Prompts

- Flash Fiction Story Prompts

- Dialogue and Screenplay Writing Prompts

- Poetry Writing Prompts

- Tumblr Writing Prompts

- Creative Writing Prompts for Kids

- Creative Writing Prompts for Adults

- Fantasy Writing Prompts

- Horror Writing Prompts

- Book Writing Software

- Novel Writing Software

- Screenwriting Software

- ProWriting Aid

- Writing Tools

- Literature and Latte

- Hemingway App

- Final Draft

- Writing Apps

- Grammarly Premium

- Wattpad Inbox

- Microsoft OneNote

- Google Keep App

- Technical Writing Services

- Business Writing Services

- Content Writing Services

- Grant Writing Services

- SOP Writing Services

- Script Writing Services

- Proposal Writing Services

- Hire a Blog Writer

- Hire a Freelance Writer

- Hire a Proposal Writer

- Hire a Memoir Writer

- Hire a Speech Writer

- Hire a Business Plan Writer

- Hire a Script Writer

- Hire a Legal Writer

- Hire a Grant Writer

- Hire a Technical Writer

- Hire a Book Writer

- Hire a Ghost Writer

Home » Blog » How to Write a Monologue in 7 Simple Steps

How to Write a Monologue in 7 Simple Steps

TABLE OF CONTENTS

There was a time when monologues were used in theatres but things are different now. Monologues are used in books, movies, novels , science fiction , TV series, and pretty much everywhere.

Writing a monologue needs creativity and a systematic approach. You can’t just start writing a good monologue without a plan. A poorly written monologue will bore readers, they might lose interest, or they might skip the monologue outright. In any case, it’s a big loss as a writer if you fail to connect with your readers at any stage.

A great writer makes readers read every single word – not just once – but multiple times.

If you are new to monologue writing and have little or no idea of where to begin, what to include, and how to write a monologue, this actionable step-by-step guide is your best bet.

How to Write a Monologue: Step-By-Step Guide

Writing a monologue doesn’t just require practice but it needs a systematic approach. You can’t just write anything and name it as a dramatic monologue, and expect your audience to make sense of it.

If you are new to monologue writing, the following 7-step guide to writing a powerful monologue will help you master the art.

Step #1: Define the Purpose of the Monologue

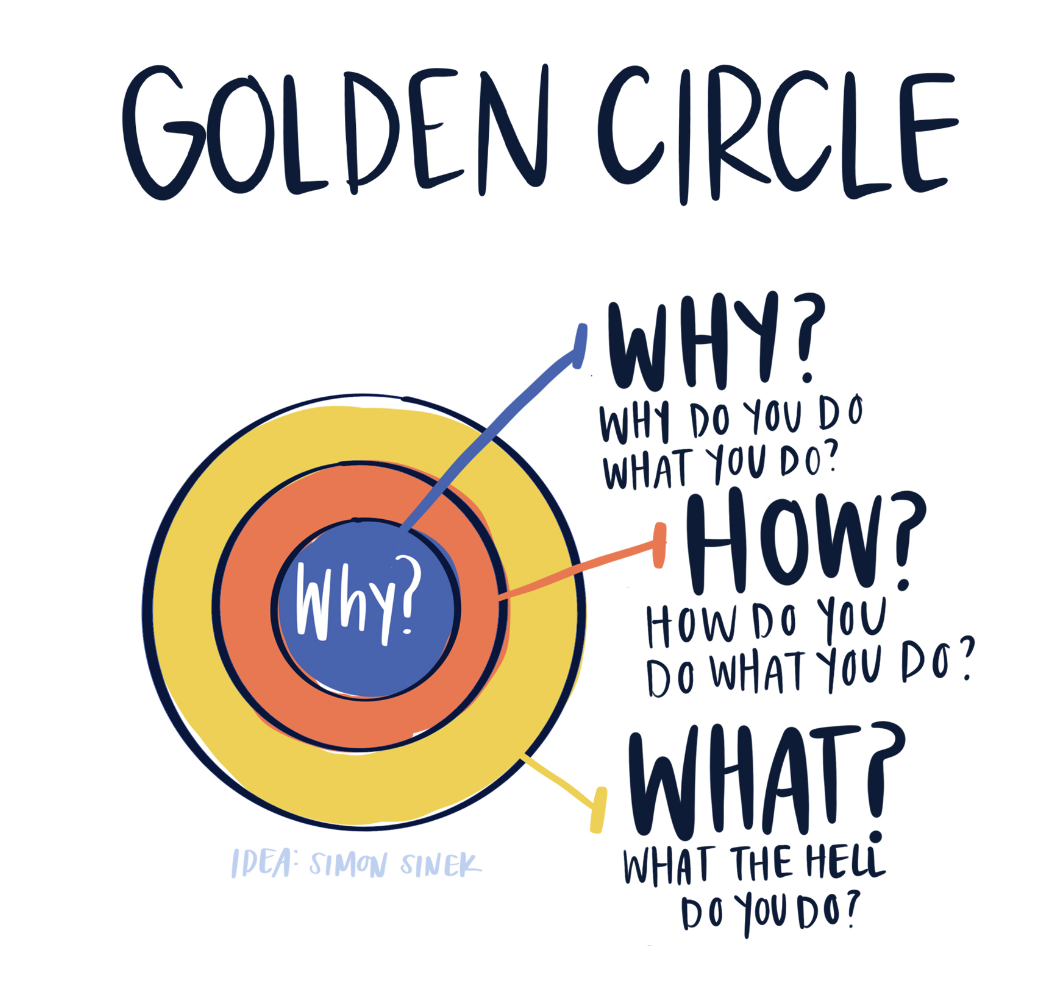

You don’t have to add a monologue to your story just for the sake of it rather you must have a clear purpose and objective that you wish to achieve with the help of a monologue. Remember the following golden circle :

Ask yourself: Why, how, and what of the monologue to clearly define its purpose.

For example, you can use monologue to reveal a secret. Writers use monologues to express a character’s true emotions or thoughts that are, otherwise, hard to express via dialogues. Whenever you find it hard to communicate with the readers via dialogue, you must consider using a monologue.

Defining the purpose of the monologue is the first and most crucial step in the writing process. You can use monologue for a wide range of purposes such as:

- Emotional release by a character

- Revealing a secret

- Answering questions related to the storyline or character

- Sharing feelings and thoughts of a character

- Communicating with the readers

Ideally, you need to make sure you are using monologue to either let a weak character express his/her views or have one of the main characters speak aloud.

Step #2: Develop Character Profile

Character development is a must. When you decide to write a monologue and you have set its purpose, you know the character already. You now need to set up the complete character profile to ensure the speech is delivered appropriately.

Remember, monologue is different. It has to be powerful, attention-grabbing, and interesting so that the audience doesn’t lose interest. You don’t just have to focus on the speech and its words rather the actor or character delivering it must be worked upon too.

Building a character profile that matches the monologue is essential. Here is a list of the major things to consider for profiling:

- Speaking style

- Character’s voice

- Tone and pitch

- Facial expressions

- Body language

- Emotions and feelings

And other details you think are necessary. Check out this 12-step guide to creating a powerful character profile .

Most of these details might not appear in the story but these are necessary as it helps you craft a better monologue. For example, the tone, pitch, and speaking style might not be visible in the book, however, when you set these upfront, you’ll be able to use words, sentences, terms, and phrases that help you deliver the tone, pitch, and style.

Character development and profiling specifically for an effective monologue are essential to keep it natural and meaningful.

Use Squibler to write your monologue and store your character, their details , dialogue , and descriptions so that you keep the characters constant throughout the story as you want them to be. You can always invoke the details by just writing the character’s name when writing your monologues with it.

Step #3: Identify the Audience

The audience refers to the people your character will be addressing. The audience is the target of your character’s monologue . If your character is addressing himself/herself, the audience in this case will be the character himself/herself.

When writing a good monologue, make sure you have a target audience identified. It will help you write a better monologue. Avoid writing your monologue without any specific audience.

For example, if there is a character expressing his feelings for another character, decide if the other character must be present or if the monologue will be delivered in his/her absence.

These petty details are always in your mind as a writer, but it is essential to write them down so that you can avoid assumptions while writing a monologue. Just because you know the audience of the monologue doesn’t mean readers will know it too.

Use Squibler’s smart writer to develop and extend the monologue. You can provide manual instructions about your intended audience, the type of conversation, and the plot to the AI tool and it will generate content within seconds for you according to your needs.

Step #4: Craft a Powerful Beginning

Now is the time to start writing the monologue. A monologue has three distinct parts: Beginning, middle, and end.

The beginning of the monologue must be powerful, and intriguing, and it must be attention-grabbing.

The first must line sets the stage for a secret and the second line further tells the readers what they must expect from the monologue.

The beginning should set the tone and mood of the monologue so it must be crafted carefully. The best approach is to write an outline for the entire monologue and then craft a beginning according to the outline.

Here are a few tips on writing an attention-grabbing beginning for your monologue:

- Stick with the purpose of your monologue and make sure the beginning adheres to the purpose

- The first line must be the best

- Start the monologue with a secret, fact, joke, or deep emotion to hook the readers

- One of the basic approaches to writing a killer monologue introduction is to begin it with the most crucial sentence (the crux of the monologue), and then explain it throughout the monologue

- Define the character and the need for the monologue. Why a speech is needed in the first place?

- Set the tone and mood by using the right words, expressions, attire, and scene.

One of the key features of writing a monologue is to use software that you are comfortable with. Using a monologue writing software saves you from a lot of issues such as formatting and organization of ideas.

Squibler , for instance, is the best AI writing app that provides you with an AI smart writer, multiple templates, and outlines that save you from the pain of doing everything from scratch. You can use an existing template and instruct the Smart Writer to generate engaging and relevant content for. Consider using a writing app so you can focus on writing instead of formatting, organizing, template, and outlining, and what’s better than using an AI one where you don’t even have to write by yourself?

Step #5: Write the Middle Part

As a writer, I’m sure you the importance of creating conflict and resolving it. The best technique to write the middle section of your interior monologue is to use conflict and climax to make it work.

This is the crux of the monologue where you have to explain everything by building your case. One of the most common ways to write a monologue is to build past-present interaction. The character, in this case, refers to past feelings and emotions and connects them to present and/or future events, actions, or thoughts.

Here is an overview of the important things to consider when writing the mid-section of a monologue:

- Use conflict to build reader interest as it works best for monologue writing. Focus on the word choice.

- Build the speech in a way that leads to the climax. Use an interconnected series of actions, words, and feelings that lead to the climax or a decisive action.

- An important revelation about the character that’s alien to the readers and other characters is often the best way to use a climax in a monologue.

- The secret (or climax) must be related to the plot and the rest of the story. It must not be an isolated climax that doesn’t impact the plot.

- Create suspense as it will keep readers hooked. Since a monologue is a speech by one character, readers might likely get bored if it lacks suspense or climax. Develop suspense with a plot twist.

The middle part of the monologue is where you need to present everything. It must be well-written and must connect with the readers emotionally. Not to forget, it must fulfill the purpose of the monologue.

If you feel stuck with adding the details and conflict, Squibler’s smart writer takes the lead. You can instruct the tool about the context, plot, and intensity you want to add, and it will generate conflict-rich intense content around your plot. If you don’t like some segment, don’t worry, you can always edit it.

Step #6: Craft a Clear Ending

A monologue without a proper ending is a rare scene. The end of the scene or the monologue must be clear, sound, and logical. It needs to give something new to the readers in the shape of a climax or a plot twist.

There are several important considerations for the ending including:

- It needs to conclude the monologue with a very strong point

- The ending must justify the purpose of the monologue

- It must end with something new preferably something that readers don’t expect at all

- The ending must show readers how the story will move forward from this point.

When you are done with the ending, you’ll have a clear view of the full monologue. This is a good time to revisit your entire monologue and see if it fits well in the story.

Step #7: Refine and Tweak

Finally, you are all set to refine, proofread, and edit your monologue. Refining your monologue is important because it is a long speech that might make readers bored. Unlike interactive dialogues, a monologue needs special attention as it’s not interactive.

Follow these advanced techniques to refine and polish your monologue:

- Read it and see how well it fits in the overall story

- See if it meets the objective and does it conveys the same message that you wanted to deliver

- Have a few experts read the monologue for improvements and suggestions

- The monologue must be short so try removing words, phrases, and weak sentences

- Keep it simple by breaking lengthy complex sentences into short phrases.

The issue of polishing and refining is taken care of by the writing app if you are using one. When you are using a monologue writing app , you’ll have a set template and outline to follow that saves you from refining your work.

What is a Monologue?

A monologue is a speech (usually long) by a single character in a film, book, novel, or story. It can be used for varied purposes such as to share a character’s viewpoints or to explain something to the readers (or audience).

Monologues originated from theatres where a character used to make a long speech to address the audience to share thoughts. But monologues aren’t limited to theatres only and are used widely in the literature in plays of all types. One of the famous monologue examples is Polonius’s speech to his son in Hamlet by William Shakespeare:

Here is another example of a monologue from Mark Antony in Julius Caesar:

Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears; I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him. The evil that men do lives after them; good is oft interred with their bones; So let it be with Caesar. The noble Brutus Hath told you Caesar was ambitious: If it were so, it was a grievous fault, And grievously hath Caesar answer’d it. Here, under leave of Brutus and the rest– For Brutus is an honourable man; So are they all, all honourable men– Come I to speak in Caesar’s funeral. He was my friend, faithful and just to me: Brutus says he was ambitious; Brutus is an honourable man.

There are different types of monologues that you can choose from. An understanding of the types of monologues helps you better craft it.

It is a monologue that’s used in drama and was used extensively in theatre in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. The character expresses his/her feelings in the speech while other characters and actors stay silent.

Interior Monologue

It is a monologue that’s used in both fiction and nonfiction stories where a protagonist expresses his/her thoughts and mindset. It depicts the thoughts (and feelings) that a character is going through.

Dramatic Monologue

It is a poem that’s written as a speech. You’ll find dramatic monologues in Robert Browning’s poems such as My Last Duchess . It is also used in novels where a character expresses his/her views and psychological viewpoint to the readers.

Advanced Tips and Tricks to Write a Monologue

Now that you know how to write a monologue in 7 easy steps, it is time to look at advanced tips, techniques, and tricks to refine and improve your monologue. You already know the basics and you know how to get started, the following tips will help you take your monologue writing skills to the next level:

- The monologue must be concise . Generally, great monologues are long speeches but you need to make sure you aren’t adding too many details. Edit it multiple times to ensure it only consists of relevant and important details and nothing else. While the concept is to have a long speech, it doesn’t necessarily mean you have to keep it lengthy. Maintain a balance.

- Have a clear understanding of the type of monologue you’ll be writing . This goes beyond the purpose of the monologue. You can choose to write a contemporary monologue instead of a poetic one. If you aren’t sure what type of monologue you’ll write, it will get extremely tough to make sense of the final product.

- The monologue must have a strong point of view, and climax , and it must have a strong impact on the story and/or character. The idea of a great monologue is to convey important details via a speech delivered by a single character. If the outcome of a monologue isn’t intriguing and it doesn’t impact the story significantly, what’s the point of writing a monologue?

- Avoid adding too many monologues close to each other . Monologues must be used when you have to convey important information or you need to reveal a secret or add a twist to the story. Having multiple monologues simultaneously means disclosing too much important information together and that’s where it gets confusing and rather boring for the readers. Add monologues at the right place where it makes the most sense.

- Read, read, and read . The more you read the best monologues, the better. It will help you understand how to write a monologue, how to structure it, what type of language to use, and so on. You’ll find a lot of monologues throughout the literature, consider reading a few of them before writing a monologue for the first time.

- Focus on the structure of the monologue , that is, it must have a clear introduction, middle, and conclusion. Consider it a story within your story with a proper opening line and ending.

- Use a writing app or software to simplify and fasten the writing process. A writing app will help you get started quickly by selecting a relevant monologue template, adding text, and that’s all. It saves you a lot of time and you can focus on writing the monologue instead of other non-writing tasks. Consider using Squibler that’s one of the best AI writing apps in the market. You can not just write, re-write, and generate content with AI, but also organize, collaborate, and assign work on the same tool.

Final Remarks

You are ready to start writing your own monologue . You know the steps on how to write a monologue, what to expect, how to make it appealing, and what techniques to use. It is time to get into it practically.

A monologue isn’t much different from any other type of writing. Once you have the first monologue ready, you’ll see how easy the process is. Simply follow the step-by-step guide in the article and you’ll be good to go.

As a writer, you might not face any obstacles in writing a monologue. You will know how to connect with the readers, how to use climax, how to reveal secrets, how to build a character, how to connect past events to present events, how to remove fluff from the text, and so on. This seems familiar, right?

Monologues aren’t much different from any other story you write. You can master it with little practice. The more you write them, the better. Your skills will improve significantly over time.

Here is a list of the most common questions that authors ask when writing monologues:

How do I start writing a monologue?

To begin your monologue, focus on a strong, relatable theme or emotion. Dive into personal experiences, observations, or fictional scenarios that evoke the intended feeling. Remember, the key is to connect with your audience through genuine expression.

Should I follow a specific structure for my monologue?

While there’s no strict formula, consider starting with a compelling opening, followed by a development of your main idea, and conclude with a memorable closing. Allow your thoughts to flow naturally, maintaining a conversational tone that keeps listeners engaged.

How long should a monologue be?

Aim for a duration that maintains the audience’s interest. Generally, 3-5 minutes is a good guideline, but let the content dictate the length. Ensure each word serves a purpose, keeping the monologue concise and impactful.

Can I use humor in a serious monologue?

Absolutely! Humor can be a powerful tool to engage your audience and create a connection. However, balance is key. Integrate humor thoughtfully, ensuring it complements the overall tone and reinforces your message rather than distracting from it.

How do I make my monologue authentic and relatable?

Inject your personality into the narrative. Share personal anecdotes, use everyday language, and express genuine emotions. Allow your unique voice to shine through, creating a connection that resonates with the audience and makes your monologue memorable.

Related Posts

Published in What is a Screenplay?

Join 5000+ Technical Writers

Get our #1 industry rated weekly technical writing reads newsletter.

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

How to Write Dramatic Monologue

Last Updated: October 4, 2023 References

This article was co-authored by Christopher Taylor, PhD . Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014. There are 13 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been viewed 393,758 times.

Whether you’re writing a novel, a screenplay, or a stage play, dramatic monologues are important tools for furthering character development and shedding light on the major themes in your story. A dramatic monologue is typically a long excerpt in a larger piece of writing that reveals the character’s thoughts and feelings, but should not slow down the pace of the larger piece, only further it. [1] X Research source

Understanding the Role and Structure of a Dramatic Monologue

- A dramatic monologue usually occurs when a character is facing an extreme crisis, a dramatic moment in the plot, or a “do-or-die” situation where simple actions can no longer suitably convey the immense feeling or desire the character is dealing with.

- An effective dramatic monologue should express the goal, agenda, or backstory of the speaker. It can also try to enlist the support of other characters or the audience, or attempt to change the hearts and minds of the audience or the listener.

- A dramatic monologue can be used in theater, poetry and film.

- A monologue differs from a soliloquy [4] X Research source in that a soliloquy is literally a character talking to him/herself. A dramatic monologue has an implied audience, as the character will usually be speaking to another character in the monologue.

The serpent that did sting thy father's life Now wears his crown. Thy uncle, Ay, that incestuous, that adulterous beast, With witchcraft of his wit, with traitorous gifts-- O wicked wit and gifts, that have the power So to seduce! -- won to his shameful lust The will of my most seeming-virtuous queen.

- Shakespeare uses a dramatic monologue to provide Hamlet's motivation to kill Claudius and to give Hamlet’s father an emotional presence in the play through a direct address to Hamlet and by extension, to the audience.

- The monologue is dramatic in that is is meant to be read to an audience. In poetry, a dramatic monologue allows the poet to express a point of view through a certain character.

Christ, it was better than hunting bear which don't know why you want him dead.

- Using the device of the dramatic monologue in the poem, Hayden is able to create powerful emotion through taking on the disturbing and violent voice of a character.

- Robert Browning's poem “My Last Duchess”. [9] X Research source

- Madame Ranevsky’s monologue in Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard . [10] X Research source

- The Indianapolis monologue in Spielberg’s Jaws . [11] X Research source

- Jules’ shepherd monologue in Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction . [12] X Research source

- To whom is the speaker addressing in the monologue?

- What does the speaker want from the addressee or receiver of the monologue?

- Why is the speaker performing the monologue at this point in the story?

- How does this monologue affect the overall plot and/or development of the speaker, as well as the other characters in the scene or in the story?

- What kind of language or description is the speaker using? What gives the speaker a unique or distinct voice?

Jules: Well there's this passage I got memorized. Ezekiel 25:17. "The path of the righteous man is beset on all sides by the inequities of the selfish and the tyranny of evil men. Blessed is he who, in the name of charity and good will, shepherds the weak through the valley of the darkness. For he is truly his brother's keeper and the finder of lost children. And I will strike down upon thee with great vengeance and furious anger those who attempt to poison and destroy my brothers. And you will know I am the Lord when I lay my vengeance upon you."

- The speaker is the character Jules Winnfield, a hit man played by Samuel L. Jackson.

- In previous scenes in the film, we are shown Jules and his partner, Vincent Vega (John Travolta) carrying out a hit on a group of college kids who stole money from their boss, Marsellus Wallace (Ving Rhames). During the hit, one of the kids shoots at Jules and Vincent, but, by some miracle, none of the bullets end up killing either men. Jules takes it as a sign from a higher power and during this dramatic monologue, explains that he is reconsidering his stance on killing others, or being “the tyranny of evil.”

- The dramatic monologue occurs at a key character moment for Jules, and the receiver of the monologue, a robber named “Honey Bunny”, becomes a stand in for all of the other people Jules has killed in the past. The monologue ends with Jules putting down his gun and allowing the robbers to leave unharmed, a major moment of character development.

- In terms of language use, Jules quotes a passage from the Bible, Ezekiel 25:17, which is a throwback to the earlier scene where he kills the college kids. Using Biblical language and then analyzing the more formal, poetic language of the Bible with curse words and casual slang like “my righteous ass” and “tryin’” instead of “trying”, Jules’ character expresses himself with a distinct tone and style in the monologue that is consistent with his speech and voice in previous scenes in the film.

Preparing to Write Your Own Dramatic Monologue

- For example, the ghost monologue in Hamlet is serving the overall story in two ways: it relays key information to the play’s protagonist (Hamlet), thereby setting him up to fulfill a revenge plot to get back at his murderous uncle [15] X Research source and also adds to the feeling of unnatural occurrences or not quite reality in the play. [16] X Research source So, though the ghost is not a major character, having the ghost as the speaker of the monologue still serves the overall story and furthers the action of the main character in the play.

- Comparatively, Jules’ monologue in “Pulp Fiction” serves to further character development in the story by allowing one of the main characters to express their emotions and explain the way his understanding of his work and of himself have evolved. The monologue illustrates the character’s progression from the beginning of the story to the end of the story and lets the viewer know a change or shift has occurred for that character.

- If it is a monologue that will show character development, you may want to place it towards the mid point or climax of the story or towards the end of the story.

- If it is a monologue that is going to spoken by a minor character to relay information to a main character or add to the theme or mood of the story, you may want to place it earlier in the action of the story.

- For example, the ghost monologue in Hamlet occurs early in the play, Act I, Scene 5. By the time the ghost appears, Shakespeare has already established Hamlet as a the main character as well as his unease or melancholy nature, and the “foul” or troubled state of the kingdom of Denmark. The monologue then moves the story forward as it causes Hamlet to take action, thereby furthering the overall plot.

- Comparably, Jules’ monologue takes place in the last scene of the film, and functions to show that Jules has changed or shifted. The previous scenes all served to illustrate Jules’ journey as a main character and prepares the audience for his moment of realization. The monologue resolves the conflict he struggled with throughout the rest of the film, so it is placed at the end of the film as a moment of resolution.

Writing the Monologue

- Use your character's voice. Keep in mind the language, description, and tone of that character. Focus on sensory details like taste, touch, sound, etc. to engage the audience’s empathy or emotion for the character by engaging their senses. [18] X Research source

- Use the present tense. This is happening now and should have a sense of urgency.

- You could begin the scene with a short introduction to the speaker, such as in the ghost monologue: “I am thy father’s spirit.”

- You could then have the speaker and the other character(s) have a conversation or dialogue to build up the monologue, such as in the diner scene with Jules’ monologue, where Jules asks if the robber (Tim Roth) reads the Bible before launching into the monologue with a Biblical passage.

- In the ghost monologue, the ghost (speaker) starts a dialogue with Hamlet and over the course of the dialogue, the ghost says lines like "Revenge his foul and most unnatural murder". [19] X Research source Gradually, the ghost's motive for speaking to Hamlet becomes clearer.

- In Jules’ monologue, he recites a passage from the Bible that will frame his larger point about the “tyranny of evil”. The passage also has a double meaning as it was used by Jules in an earlier scene right before he killed the college kids. This is a callback to the previous scene but it places the same passage within a different moment in the character’s journey. The context for the passage has changed for Jules and as a result, it has also changed for the audience.

- In the ghost monologue, the climax occurs once the ghost has detailed how he was poisoned by his own brother, Hamlet’s uncle, and his crown and queen was stolen from him. This is a game changer for Hamlet (and by extension, the audience), as it then moves Hamlet to avenge his father’s death and also allows the audience to have sympathy for the wrongful death of Hamlet's father.

- In Jules’ monologue, the climax occurs when Jules notes that the listener (the robber) is “weak” and he is the “tyranny of evil” but, despite this evil, he is “tryin’ real hard to be the shepherd”. This climax indicates the robbers will likely live instead of die, and also illustrate the reason why Jules decides to give up his life as a hitman and be a “shepherd” rather than be an active part of the “tyranny of evil.”

- The ghost monologue ends with a call to action for Hamlet to avenge his murder. In the rest of the scene, Hamlet acknowledges this new information about his murderous uncle and responds to the ghost’s call to vengeance by vowing to get even.

- At the end of Jules’ monologue, he punctuates his desire to be a “shepherd” rather than part of the “tyranny of evil” by cocking his gun and placing it on the table, thereby allowing the robbers to leave the scene unharmed.

Editing the Monologue

- Ensure the monologue flows well within the larger story. There should be enough build up or dramatic tension in the moments before the monologue occurs to justify the need for a dramatic monologue. [20] X Research source

- The audience should be prepared, rather than surprised or confused, by the monologue.

- Check the timing of the monologue. Does it take too long to get started? Should it end sooner? What can be cut from the draft? Look for places where the monologue sounds redundant or the same point is stated in different ways.

- Ask your listeners if they understood the overall message or purpose of the monologue.

- If you are writing a dramatic monologue for a play or film, it may be useful to have two people act out the scene with the monologue.

- Have someone read the monologue back to you. Listening to someone else interpret your words is a great way to see if your message is clear, the character voice is believable, and there is enough detail in the monologue.

Sample Monologue

Expert Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://education-portal.com/academy/lesson/dramatic-monologue-definition-examples-quiz.html

- ↑ http://www.wheresthedrama.com/monologues.htm

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/553410/soliloquy

- ↑ http://www.monologuearchive.com/s/shakespeare_004.html

- ↑ http://www.poets.org/poetsorg/text/poetic-technique-dramatic-monologue

- ↑ http://www.blueridgejournal.com/poems/rh-night.htm

- ↑ http://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poem/my-last-duchess

- ↑ http://www.monologuearchive.com/c/chekhov_014.html

- ↑ http://www.monologuegenie.com/monologue-writing-101.html

- ↑ http://www.whysanity.net/monos/jules.html

- ↑ http://www.shakespeare-online.com/plays/hamlet_1_5.html

- ↑ http://www.shmoop.com/hamlet/ghost.html

- ↑ https://overland.org.au/2012/07/dont-kill-your-darlings/

About This Article

A dramatic monologue is a great way to draw your audience in and shed some light on your character. To write a good monologue, you’ll want to start with a compelling opening statement to grab the audience’s attention, like “I am just like my father.” Then, have your character work through whatever issue they’re having out loud. Keep in mind that a monologue, while spoken by 1 character, is usually addressed to another character, so you should plan to have a 2nd character on stage during the scene. A good monologue usually ends with a call to action that keeps the play moving. For example, you might have your character resolve to avenge his father’s death at the end of his speech. To learn how to edit your monologue, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Nov 18, 2018

Did this article help you?

Raymond Mazire

Mar 1, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Develop the tech skills you need for work and life

- How to Write a Powerful Monologue (With Examples)

by Joe Keith | Feb 19, 2022 | Theater | 0 comments

Since ancient Greek theater, a powerful monologue can be used as a way to captivate an audience. Some of the greatest moments in theatre and films have come in the form of monologues.

However, it is one thing to have monologues in your script, and it is another thing to know why you are writing them as well as how to write them well.

Before going into all the interesting details about writing a strong monologue, let’s see what a monologue actually is.

My musician friends could always practice what they loved doing, but I can’t go on a street corner and start reciting a monologue. Acting is very collaborative, and you always need other people with you – mainly an audience. Julia Stiles

What is a Monologue?

The word “monologue” consists of the Greet roots for “alone” and “speak.” The term refers to a long speech by a single character that is either addressing other characters in the scene or talking to the audience.

A monologue can serve a specific purpose in storytelling. If used carefully, a powerful monologue can give the audience more details about a plot or a character. They are a great way to share the backstory of a character or his internal thoughts.

While monologues and soliloquy are similar (since in both, speeches are presented by a single character), the main difference between them is that the speaker in a monologue reveals his thoughts to other characters in the scene or the audience, while the speaker in a soliloquy expresses his thoughts to himself.

Examples of Powerful Monologues

- Jocasta in Oedipus the King: “Why should a mortal man, the sport of chance, with no assured foreknowledge, be afraid?”

- Antigone in Antigone: “Yea for these laws were not ordained by Zeus, And she who sits enthroned with gods below…”

- Marc Antony in Julius Caesar: “Friends, Romans, Countrymen, lend me your ears; I have come to bury Caesar, not to praise him…”

- Flute (as Thisbe) in A Midsummer Night’s Dream: “Asleep, my love? What, dean, my dove? O Pyramus, arise!”

- Gloucester in Richard III: “Now is the winter of our discontent Made glorious summer by this sun of York…”

- Jacques in As You Like it: “All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players…”

- Hamlet in Hamlet: “To be, or not to be, that is the question…”

- Viola in Twelfth Night: “I left no ring with her: what means this lady?”

Monologue Structuring Tips

The structuring of a good monologue is similar to that of a good story ; it will have a beginning, a middle, and an end. Without a buildup and a resolution, long stories can become stale and monotonous.

- Beginning: there’s always a reason to initiate a monologue, even in real life. People usually start speaking in response to something that happened or was said. Your first line must make a smooth transition into a monologue. An easy way to start a monologue could be “I was thinking of what was said of him…”

- Middle: This is usually the toughest part to write in a monologue. This is because long speeches can bore your viewers, and so it is important to avoid predictable monologues. You can achieve this by crafting little twists and turns into the storytelling. Adding such interesting plot details, and unique ways the character describes them can keep your monologues engaging and fresh.

- End: it is common for monologues to end with a quick statement of meaning, especially monologues meant to convince other characters in the scene to do something. You don’t have to do so much explanation nonetheless, you can trust your audience to find meaning in it for themselves.

In conclusion , there has to be a purpose for using a monologue in a play or film. It shouldn’t be used merely to tell what you can’t show. Instead, it should add more depth to your story, or be a call to action.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Recent Posts

- Boost Your Confidence With Dancing

- How to Find Your Acting Niche

- 5 Plays Every Actor Should Read

- Why is Music so Important for Motivation?

Recent Comments

- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Use a Monologue

I. What is a Monologue?

A monologue is a speech given by a single character in a story. In drama, it is the vocalization of a character’s thoughts; in literature, the verbalization. It is traditionally a device used in theater—a speech to be given on stage—but nowadays, its use extends to film and television.

II. Example of a Monologue

A monologue speaks at people, not with people. Many plays and shows involving performers begin with a single character giving a monologue to the audience before the plot or action begins. For example, envision a ringleader at a circus…

Ladies and Gentleman, Boys and Girls!

Tonight, your faces will glow with wonder

As you witness some of the greatest acts ever seen in the ring!

Beauties and beasts, giants and men, dancers and daredevils

Will perform before your very eyes

Some of the most bold and wondrous stunts

You’ve yet beheld!

Watch, now,

As they face fire and water,

Depths and heights,

Danger and fear…

The ringleader’s speech is directed to the audience. His monologue helps him build anticipation and excitement in his viewers while he foreshadows some of the thrills the performance will contain.

A monologue doesn’t have to be at the start or end of a play, show, or movie—on the contrary, they occur all of the time. Imagine a TV series about a group of young friends, and on this episode, one friend has been being a bully. The group is telling jokes about some of the things the bully has done to other kids at school, when one girl interrupts everyone…

You know, I don’t think what you are doing is funny. In fact, I think it is sad. You think you’re cool because you grew faster than some people, and now you can beat them up? What is cool about hurting people? We are all here pretending that you’re a leader, when really, I know that you’re nothing but a mean bully! All this time I’ve been scared to say that, but just now, I realized that I’m not afraid of bullies—so, I won’t be afraid of you!

When a conversation stops and shifts focus to a single character’s speech, it is usually a sign of a monologue. In this situation, a group conversation between friends turns into one girl’s response; a monologue addressing bullying and the bully himself.

III. Types of Monologues

A. soliloquy.

A speech that a character gives to himself—as if no one else is listening — which voices his inner thoughts aloud. Basically, a soliloquy captures a character talking to himself at length out loud . Of course, the audience (and sometimes other characters) can hear the speech, but the person talking to himself is unaware of others listening. For example, in comedy, oftentimes a character is pictured giving themselves a lengthy, uplifting speech in the mirror…while a friend is secretly watching them and laughing. The soliloquy is one of the most fundamental dramatic devices used by Shakespeare in his dramas .

B. Dramatic Monologue

A speech that is given directly to the audience or another character. It can be formal or informal, funny or serious; but it is almost always significant in both length and purpose. For example, a scene that captures a president’s speech to a crowd exhibits a dramatic monologue that is both lengthy and important to the story’s plotline. In fact, in TV, theater ,and film, all speeches given by a single character—to an audience, the audience, or even just one character—are dramatic monologues .

C. Internal Monologue

The expression of a character’s thoughts so that the audience can witness (or read, in literature) what is going on inside that character’s mind. It is sometimes (depending on the style in) referred to as “stream-of-consciousness.” In a piece of writing, internal monologues can often be easily identified by italicized blocks of text that express a character’s inner thoughts. On TV and in films, internal monologues are usually spoken in the character’s voice, but without seeing him actually speak; thus giving the feeling of being able to hear his thoughts .

IV. Importance of Monologues

Monologues give the audience and other characters access to what a particular character is thinking, either through a speech or the vocalization of their thoughts. While the purpose of a speech is obvious, the latter is particularly useful for characterization : it aids the audience in developing an idea about what the character is really thinking, which in turn helps (or can later help) explain their previous (or future) actions and behavior.

V. Examples of Monologue in Literature

As a technique principally used on the stage (or screen), the best examples of monologues in literature are found in dramatic literature, most notably in Shakespeare’s dramas. Below is selection of arguably the most famous monologue in literature— soliloquy , specifically—from Act III Scene I of the tragedy Hamlet . This soliloquy begins with the well-known words “To be, or not to be- that is the question:”

HAMLET To be, or not to be- that is the question: Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune Or to take arms against a sea of troubles, And by opposing end them. To die- to sleep- No more; and by a sleep to say we end The heartache, and the thousand natural shocks That flesh is heir to. ‘Tis a consummation Devoutly to be wish’d. To die- to sleep. To sleep- perchance to dream: ay, there’s the rub! For in that sleep of death what dreams may come When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, Must give us pause. There’s the respect That makes calamity of so long life.

This scene reveals to the audience that Hamlet is contemplating suicide. His words express an internal thought process that we would normally not be able to witness. The only reason that Shakespeare has Hamlet speak these words out loud is so that the audience—not anyone else in the play—can hear them. He uses a soliloquy to share Hamlet’s unstable state of mind and disquieting thoughts.

In Mark Twain’s short story “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County,” the narrator is sent to find a man named Simon Wheeler, who will tell him a story. After the narrator introduces the premise, he explains that he let Wheeler “go on in his own way, and never interrupted him once.” He follows with Wheeler’s story, told in Wheeler’s voice, which he achieves through the shift in the style of speech. Below is a small piece of the story:

There was a feller here once by the name of Jim Smiley, in the winter of ’49—or may be it was the spring of ’50—I don’t recollect exactly, somehow, though what makes me think it was one or the other is because I remember the big flume wasn’t finished when he first came to the camp; but any way he was the curiosest man about always betting on any thing that turned up you ever see, if he could get anybody to bet on the other side; and if he couldn’t, he’d change sides. Any way that suited the other man would suit him—any way just so’s he got a bet, he was satisfied. But still he was lucky, uncommon lucky; he most always come out winner.

Mark Twain was a literary genius when it came to storytelling—he could make the page seem like a stage with the way he used spelling and grammar to bring a character’s accent and personality to life. Wheeler’s story is a dramatic monologue , which Twain used to achieve the feeling of a real storytelling exchange between two people. His employment of this dramatic technique in this short story makes the readers feel like they are hearing Wheeler’s story firsthand.

VI. Examples of Monologue in Pop Culture

Oftentimes, a conversation occurs between characters and then shifts to one character giving a significant speech. This is a popular way of inserting a monologue into a scene. In this scene from Season 5 Episode 10 of the TV horror The Walking Dead , the group is talking around the campfire:

Every day he woke up and told himself, ‘Rest in peace; now get up and go to war,’” says Rick. “After a few years of pretending he was dead, he made it out alive. That’s the trick of it, I think. We do what we need to do, and then we get to live. No matter what we find in D.C., I know we’ll be okay. This is how we survive: We tell ourselves that we are the walking dead. -Rick Grimes

Here, Rick’s monologue begins when the dialogue ceases to be a group discussion. Now he alone is speaking to the group—he is giving a dramatic monologue .

In one of the most popular Christmas movies to date, A Christmas Story , the protagonist Ralphie is also the narrator. However, the narration is internal: Ralphie isn’t speaking directly to us, but he is openly letting us in on his thoughts.

As you’ve now heard in this clip, Ralphie’s voice is that of an adult man, and that’s why the narration style in this film is unique—adult Ralphie is simultaneously reflecting on the past and reenacting present-Ralphie’s thoughts. The mental debate he has about who taught him the curse word and what to tell his mother is an internal monologue : we can hear his thoughts; thus the situation is funnier and more thought provoking.

VIII. Related Terms

An aside is when a character briefly pauses to speak directly to the audience, but no other characters are aware of it. It is very similar to a monologue; however, the primary difference between the two is that an aside is very short ; it can be just one word, or a couple of sentences, but it is always brief—monologues are substantial in length. Furthermore, an aside is always said directly to the audience, usually accomplished (in film and television) by looking directly into the camera. As an example, asides are a key part of the style of the Netflix series House of Cards ; the main character Francis Underwood often looks directly into the camera and openly addresses the audience as if they are present, while the other characters do not know that the audience exists.

While a monologue is a given by one character (“mono”=single), a dialogue is a conversation that occurs between two or more characters. Monologues and dialogues are similar in that they both deliver language to the audience. For instance, in a movie, a race winner’s speech is a monologue, however, a speech collectively given by several members of a team is dialogue. Both techniques can address the audience, but the difference lies in how many people are speaking.

In conclusion, monologues (and dialogues) are arguably the most fundamental parts of onstage drama and dramatic literature. Without them, essentially only silent film and theater could exist, as monologues provide the only way for the audience to witness a character’s thoughts.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

Story Arcadia

How To Write A Monologue

Writing a monologue can be a challenging but rewarding task. Whether you are a playwright, actor, or simply someone looking to express themselves through the art of solo performance, crafting a compelling monologue requires careful attention to detail and a deep understanding of character and storytelling.

The first step in writing a monologue is to choose a compelling and relatable topic. This could be a personal experience, an issue that is important to you, or a fictional scenario that resonates with your audience. Once you have chosen your topic, it’s important to consider the perspective from which you will be speaking. Are you speaking as yourself, or are you embodying a character? Understanding the point of view from which you are speaking will help guide the tone and language of your monologue.

Next, consider the structure of your monologue. A well-crafted monologue typically has a clear beginning, middle, and end. The beginning should grab the audience’s attention and establish the setting and context of the monologue. The middle should delve deeper into the topic at hand, exploring emotions, conflicts, and revelations. The end should provide closure or leave the audience with something to ponder.

When it comes to writing the actual dialogue of your monologue, it’s important to make every word count. Each line should serve a purpose in advancing the story or revealing something about the character. Consider using vivid imagery, sensory details, and figurative language to bring your words to life and engage the audience’s imagination.