How it works

Transform your enterprise with the scalable mindsets, skills, & behavior change that drive performance.

Explore how BetterUp connects to your core business systems.

We pair AI with the latest in human-centered coaching to drive powerful, lasting learning and behavior change.

Build leaders that accelerate team performance and engagement.

Unlock performance potential at scale with AI-powered curated growth journeys.

Build resilience, well-being and agility to drive performance across your entire enterprise.

Transform your business, starting with your sales leaders.

Unlock business impact from the top with executive coaching.

Foster a culture of inclusion and belonging.

Accelerate the performance and potential of your agencies and employees.

See how innovative organizations use BetterUp to build a thriving workforce.

Discover how BetterUp measurably impacts key business outcomes for organizations like yours.

A demo is the first step to transforming your business. Meet with us to develop a plan for attaining your goals.

- What is coaching?

Learn how 1:1 coaching works, who its for, and if it's right for you.

Accelerate your personal and professional growth with the expert guidance of a BetterUp Coach.

Types of Coaching

Navigate career transitions, accelerate your professional growth, and achieve your career goals with expert coaching.

Enhance your communication skills for better personal and professional relationships, with tailored coaching that focuses on your needs.

Find balance, resilience, and well-being in all areas of your life with holistic coaching designed to empower you.

Discover your perfect match : Take our 5-minute assessment and let us pair you with one of our top Coaches tailored just for you.

Research, expert insights, and resources to develop courageous leaders within your organization.

Best practices, research, and tools to fuel individual and business growth.

View on-demand BetterUp events and learn about upcoming live discussions.

The latest insights and ideas for building a high-performing workplace.

- BetterUp Briefing

The online magazine that helps you understand tomorrow's workforce trends, today.

Innovative research featured in peer-reviewed journals, press, and more.

Founded in 2022 to deepen the understanding of the intersection of well-being, purpose, and performance

We're on a mission to help everyone live with clarity, purpose, and passion.

Join us and create impactful change.

Read the buzz about BetterUp.

Meet the leadership that's passionate about empowering your workforce.

For Business

For Individuals

The importance of knowing yourself: your key to fulfillment

Jump to section

What does it mean to know yourself?

The importance and benefits of knowing one's self, how to know yourself better, how to improve your self-knowledge, how coaching can help.

Think of the most eccentric person in your life. You know the one.

The one who either shows up in a disheveled leather jacket or an all-black outfit and a beret. They’re somewhat aloof but always energetic. Unapologetically flamboyant, but always kind and understanding. This person chooses to be themselves, not who they’re expected to be.

They don’t care about the world’s expectations. This sometimes gets them into trouble or attracts judging glares from nearby strangers. But, you have to admit, it would be nice to have that kind of self-confidence . And you can!

In a world rife with expectations, living authentically can feel impossible. It feels easier to have your path planned for you. But, in the long run, this will only hold you back from living a fulfilling life.

The great philosopher Socrates said it himself: “To know thyself is the beginning of wisdom.”

So if you’re wondering whether authenticity is worth pursuing, the short answer is “yes.” And, for the detail-oriented among you, here’s everything you need to know about the importance of knowing yourself — so you too can find your true self.

Knowing yourself is about discovering what makes you tick. Among other things, it means:

- Learning your likes and dislikes

- Unearthing your beliefs and values

- Knowing your personal boundaries

- Accepting your personality traits

- Being a better team player

- Having a clearer path in your professional life

- Understanding how you interact with others

- Recognizing your core personal values

- Increasing your capacity for self-compassion

- Having a clearer idea of your life’s purpose

- Knowing what it takes to be self-motivated

- Being more adaptable

Ultimately, all of these things will increase your self-awareness . Being more self-aware lends to enhanced self-development, acceptance, and proactivity while benefiting our overall mental health .

We’ll be more confident, make better decisions, have stronger relationships, and be more honest .

Knowing yourself is about knowing what makes you tick. It means identifying what matters to you, your strengths and weaknesses, your behaviors, tendencies, and thought patterns. This list describes the importance and benefits of knowing one's self:

1. Despite your quirks, flaws, and insecurities, you learn self-love and acceptance. Once you do, you can walk through the world with more confidence and care less about what people think.

2. You can change your personality flaws and improve on your weaknesses. You are empowered to become who you want to be. This will help you become a better, more well-rounded person.

3. You’ll have more emotional intelligence , which is key to knowing others. You’ll be more conscious of your own emotions and feelings, making it easier to understand another person's point of view.

4. You'll be more confident. Self-doubt disappears when you know and accept yourself, and others won't influence you as easily. It'll be easier to stand your ground .

5. You’ll forge better relationships. It’s easier to share yourself when you know yourself. You’ll also know what kind of people you get along with, so you can find your community .

6. You’ll be less stressed. Self-awareness will help you make decisions that are better for you. And when this happens, you become less stressed about what people think or whether you made the right choice.

7. You’ll break patterns of disappointment. Y ou'll find repetitive behaviors that lead to poor outcomes when you look inward. Once you name them, you can break them.

8. You’ll be happier. Expressing who you are, loud and proud, will help you improve your well-being.

10. You'll have more self-worth. Why is self-worth important? Because it helps you avoid compromising your core values and beliefs. Valuing yourself also teaches others to respect you.

11. You'll understand your values. We can’t understate the importance of knowing your values. They will help you make decisions aligned with who you are and what you care about.

12. You'll find purpose in life. Knowing purpose in life will give you a clear idea of where you should go and what you should do.

Getting to know yourself is hard. It involves deep self-reflection, honesty, and confronting parts of yourself you might be afraid of. But it’s a fundamental part of self-improvement .

If you need help, try working with a professional. BetterUp can help you navigate your inner world.

Now that we’re clear on the importance of knowing yourself, you might not know where to get started. Let’s get into it.

Check your VITALS

Author Meg Selig coined the term VITALS as a guide for developing self-knowledge. Its letters spell out the six core pillars of self-understanding:

These are your guides for decision-making and setting your goals. Understanding them will help you make decisions aligned with your authentic self. Here are some example values:

- Being helpful

- Trust

- Wealth

You can see how each of these might lead to different life choices. For example, if you value honesty, you might quit a job where you have to lie to others.

2. I nterests

Your interests are what you do without being asked, like your hobbies, passions, and causes you care about. You can then try to align your work with these interests. Here are some examples:

- Climate change. If you’re passionate about this issue, you might choose to work directly on the problem. Or you can make choices that allow for a more sustainable lifestyle, like owning an electric car.

- Audio editing. Perhaps you’re an amateur musician, and you spend your time recording and editing audio. You can start working as a freelance editor or find a job that uses these skills.

- Fitness. If you love working out and value helping others, you might consider becoming a trainer at your local gym or leading a running group.

Not all of your interests need to be a side-hustle . But being aware of them can help you make decisions that better suit your desired life. It is really about knowing your priorities.

3. T emperament

Your temperament describes where your energy comes from. You might be an introvert and value being alone. Or, as an extrovert, you find energy being around others.

Knowing your temperament will help you communicate your needs to others.

If you’re a meticulous planner going on a trip, you should communicate this to your more spontaneous travel buddy. They might feel suffocated by your planning, leading to arguments down the road. Bringing it up before your trip will help talk it out to avoid conflict later.

4. A round-the-clock activities

This refers to when you like to do things. If you’re a writer and you’re more creative at night, carve out time in the evening to work. If you prefer working out in the morning, make it happen. Aligning your schedule with your internal clock will make you a happier human being.

5. L ife-mission and goals

Knowing your life mission is about knowing what gives your life meaning. It gives you purpose, a vocation , and something to strive for.

To find your life mission, think about what events were most meaningful to you so far. For example:

- Leading a successful project at the office

- Influencing positive change through your work

- Helping someone else succeed

There are many ways to fulfill a life mission. You can fulfill your goals with the skills and resources you have. For example, “helping someone succeed” could mean becoming a teacher or mentoring a young professional.

6. S trengths and weaknesses

These include both “hard skills” (like industry-specific knowledge and talents) and “soft skills” (like communication or emotional intelligence ).

When you do what you’re good at, you’re more likely to succeed, which will improve your morale and mental health.

Knowing your weaknesses and toxic traits will help you improve on them or minimize their influence on your life.

Are you ready to get started? There are many ways to understand your inner self:

- Write in a journal

- Step out of your comfort zone

- Track your progress

- Choose smart habits

A professional coach will encourage you to reflect on and reframe your inner thoughts and patterns. They understand that, in many cases, impulsivity holds you back from attaining your full potential.

The amygdala — an almond-sized region of the brain partially responsible for emotions — releases dopamine to reinforce impulsive behavior . This happens every time you open Facebook instead of working, eat chocolate while on a diet, or get angry at your colleagues instead of helping solve the problem.

Self-awareness can help you overcome your impulsivity. Armed with the right tools, you can break unhealthy or unwanted behaviors.

A coach can help you meet these ends. They can teach you:

- Mindfulness: the acceptance that nothing is inherently good or bad

- Metacognition: the awareness that your mind is the root of your actions

- Reframing: the power to react differently to an event or circumstance

These three elements can help you strengthen your self-control . You'll keep a cool head in stressful situations, communicate more effectively with others, and become a better leader overall.

In other words: by checking in with yourself, you avoid wrecking yourself.

At BetterUp , our coaches are trained in Inner Work® and understand the importance of knowing yourself. This is a lifetime journey. But together, we can make your life better.

Discover your authentic self

Kickstart your path to self-discovery and self-awareness. Our coaches can guide you to better understand yourself and your potential.

Allaya Cooks-Campbell

With over 15 years of content experience, Allaya Cooks Campbell has written for outlets such as ScaryMommy, HRzone, and HuffPost. She holds a B.A. in Psychology and is a certified yoga instructor as well as a certified Integrative Wellness & Life Coach. Allaya is passionate about whole-person wellness, yoga, and mental health.

The benefits of knowing yourself: Why you should become your own best friend

Self-knowledge examples that will help you upgrade to you 2.0, how to reset your life in 10 ways, tune in to the self discovery channel with 10 tips for finding yourself, reinventing yourself: 10 ways to realize your full potential, 10 self-discovery techniques to help you find yourself, life purpose: the inspiration you need to find your drive, 15 questions to discover your life purpose and drive meaning, use the wheel of life® tool to achieve better balance, similar articles, the subtle, but important, difference between confidence and arrogance, learn how to introduce yourself in conversation and in writing, how self-compassion and motivation will help achieve your goals, how to walk the freeing path of believing in yourself, what is self-awareness and how to develop it, self-awareness in leadership: how it will make you a better boss, what are metacognitive skills examples in everyday life, stay connected with betterup, get our newsletter, event invites, plus product insights and research..

3100 E 5th Street, Suite 350 Austin, TX 78702

- Platform Overview

- Integrations

- Powered by AI

- BetterUp Lead

- BetterUp Manage™

- BetterUp Care™

- Sales Performance

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Case Studies

- Why BetterUp?

- About Coaching

- Find your Coach

- Career Coaching

- Communication Coaching

- Life Coaching

- News and Press

- Leadership Team

- Become a BetterUp Coach

- BetterUp Labs

- Center for Purpose & Performance

- Leadership Training

- Business Coaching

- Contact Support

- Contact Sales

- Privacy Policy

- Acceptable Use Policy

- Trust & Security

- Cookie Preferences

Photo by Trent Parke/Magnum

You are a network

You cannot be reduced to a body, a mind or a particular social role. an emerging theory of selfhood gets this complexity.

by Kathleen Wallace + BIO

Who am I? We all ask ourselves this question, and many like it. Is my identity determined by my DNA or am I product of how I’m raised? Can I change, and if so, how much? Is my identity just one thing, or can I have more than one? Since its beginning, philosophy has grappled with these questions, which are important to how we make choices and how we interact with the world around us. Socrates thought that self-understanding was essential to knowing how to live, and how to live well with oneself and with others. Self-determination depends on self-knowledge, on knowledge of others and of the world around you. Even forms of government are grounded in how we understand ourselves and human nature. So the question ‘Who am I?’ has far-reaching implications.

Many philosophers, at least in the West, have sought to identify the invariable or essential conditions of being a self. A widely taken approach is what’s known as a psychological continuity view of the self, where the self is a consciousness with self-awareness and personal memories. Sometimes these approaches frame the self as a combination of mind and body, as René Descartes did, or as primarily or solely consciousness. John Locke’s prince/pauper thought experiment, wherein a prince’s consciousness and all his memories are transferred into the body of a cobbler, is an illustration of the idea that personhood goes with consciousness. Philosophers have devised numerous subsequent thought experiments – involving personality transfers, split brains and teleporters – to explore the psychological approach. Contemporary philosophers in the ‘animalist’ camp are critical of the psychological approach, and argue that selves are essentially human biological organisms. ( Aristotle might also be closer to this approach than to the purely psychological.) Both psychological and animalist approaches are ‘container’ frameworks, positing the body as a container of psychological functions or the bounded location of bodily functions.

All these approaches reflect philosophers’ concern to focus on what the distinguishing or definitional characteristic of a self is, the thing that will pick out a self and nothing else, and that will identify selves as selves, regardless of their particular differences. On the psychological view, a self is a personal consciousness. On the animalist view, a self is a human organism or animal. This has tended to lead to a somewhat one-dimensional and simplified view of what a self is, leaving out social, cultural and interpersonal traits that are also distinctive of selves and are often what people would regard as central to their self-identity. Just as selves have different personal memories and self-awareness, they can have different social and interpersonal relations, cultural backgrounds and personalities. The latter are variable in their specificity, but are just as important to being a self as biology, memory and self-awareness.

Recognising the influence of these factors, some philosophers have pushed against such reductive approaches and argued for a framework that recognises the complexity and multidimensionality of persons. The network self view emerges from this trend. It began in the later 20th century and has continued in the 21st, when philosophers started to move toward a broader understanding of selves. Some philosophers propose narrative and anthropological views of selves. Communitarian and feminist philosophers argue for relational views that recognise the social embeddedness, relatedness and intersectionality of selves. According to relational views, social relations and identities are fundamental to understanding who persons are.

Social identities are traits of selves in virtue of membership in communities (local, professional, ethnic, religious, political), or in virtue of social categories (such as race, gender, class, political affiliation) or interpersonal relations (such as being a spouse, sibling, parent, friend, neighbour). These views imply that it’s not only embodiment and not only memory or consciousness of social relations but the relations themselves that also matter to who the self is. What philosophers call ‘4E views’ of cognition – for embodied, embedded, enactive and extended cognition – are also a move in the direction of a more relational, less ‘container’, view of the self. Relational views signal a paradigm shift from a reductive approach to one that seeks to recognise the complexity of the self. The network self view further develops this line of thought and says that the self is relational through and through, consisting not only of social but also physical, genetic, psychological, emotional and biological relations that together form a network self. The self also changes over time, acquiring and losing traits in virtue of new social locations and relations, even as it continues as that one self.

H ow do you self-identify? You probably have many aspects to yourself and would resist being reduced to or stereotyped as any one of them. But you might still identify yourself in terms of your heritage, ethnicity, race, religion: identities that are often prominent in identity politics. You might identify yourself in terms of other social and personal relationships and characteristics – ‘I’m Mary’s sister.’ ‘I’m a music-lover.’ ‘I’m Emily’s thesis advisor.’ ‘I’m a Chicagoan.’ Or you might identify personality characteristics: ‘I’m an extrovert’; or commitments: ‘I care about the environment.’ ‘I’m honest.’ You might identify yourself comparatively: ‘I’m the tallest person in my family’; or in terms of one’s political beliefs or affiliations: ‘I’m an independent’; or temporally: ‘I’m the person who lived down the hall from you in college,’ or ‘I’m getting married next year.’ Some of these are more important than others, some are fleeting. The point is that who you are is more complex than any one of your identities. Thinking of the self as a network is a way to conceptualise this complexity and fluidity.

Let’s take a concrete example. Consider Lindsey: she is spouse, mother, novelist, English speaker, Irish Catholic, feminist, professor of philosophy, automobile driver, psychobiological organism, introverted, fearful of heights, left-handed, carrier of Huntington’s disease (HD), resident of New York City. This is not an exhaustive set, just a selection of traits or identities. Traits are related to one another to form a network of traits. Lindsey is an inclusive network, a plurality of traits related to one another. The overall character – the integrity – of a self is constituted by the unique interrelatedness of its particular relational traits, psychobiological, social, political, cultural, linguistic and physical.

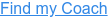

Figure 1 below is based on an approach to modelling ecological networks; the nodes represent traits, and the lines are relations between traits (without specifying the kind of relation).

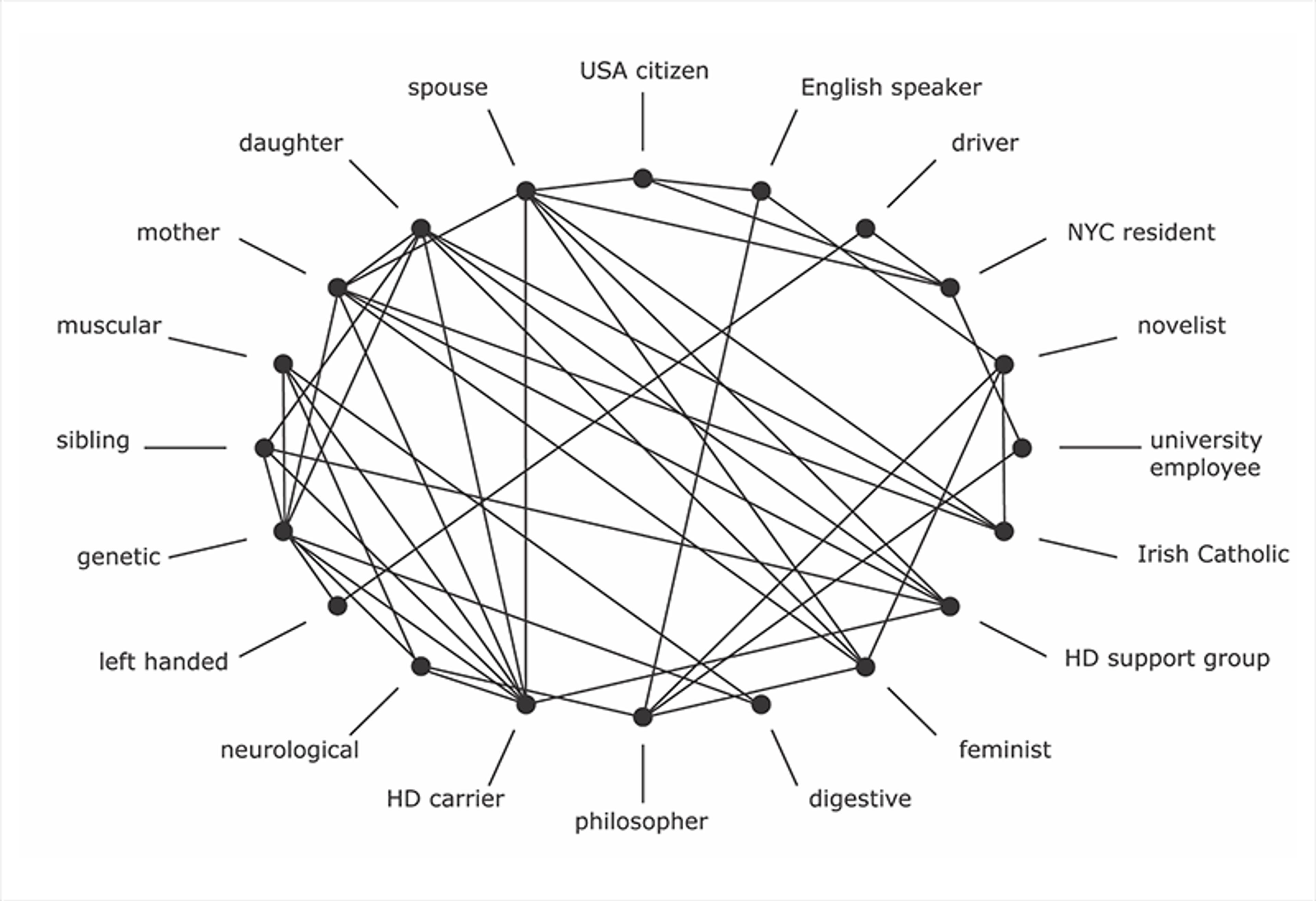

We notice right away the complex interrelatedness among Lindsey’s traits. We can also see that some traits seem to be clustered, that is, related more to some traits than to others. Just as a body is a highly complex, organised network of organismic and molecular systems, the self is a highly organised network. Traits of the self can organise into clusters or hubs, such as a body cluster, a family cluster, a social cluster. There might be other clusters, but keeping it to a few is sufficient to illustrate the idea. A second approximation, Figure 2 below, captures the clustering idea.

Figures 1 and 2 (both from my book , The Network Self ) are simplifications of the bodily, personal and social relations that make up the self. Traits can be closely clustered, but they also cross over and intersect with traits in other hubs or clusters. For instance, a genetic trait – ‘Huntington’s disease carrier’ (HD in figures 1 and 2) – is related to biological, family and social traits. If the carrier status is known, there are also psychological and social relations to other carriers and to familial and medical communities. Clusters or sub-networks are not isolated, or self-enclosed hubs, and might regroup as the self develops.

Sometimes her experience might be fractured, as when others take one of her identities as defining all of her

Some traits might be more dominant than others. Being a spouse might be strongly relevant to who Lindsey is, whereas being an aunt weakly relevant. Some traits might be more salient in some contexts than others. In Lindsey’s neighbourhood, being a parent might be more salient than being a philosopher, whereas at the university being a philosopher is more prominent.

Lindsey can have a holistic experience of her multifaceted, interconnected network identity. Sometimes, though, her experience might be fractured, as when others take one of her identities as defining all of her. Suppose that, in an employment context, she isn’t promoted, earns a lower salary or isn’t considered for a job because of her gender. Discrimination is when an identity – race, gender, ethnicity – becomes the way in which someone is identified by others, and therefore might experience herself as reduced or objectified. It is the inappropriate, arbitrary or unfair salience of a trait in a context.

Lindsey might feel conflict or tension between her identities. She might not want to be reduced to or stereotyped by any one identity. She might feel the need to dissimulate, suppress or conceal some identity, as well as associated feelings and beliefs. She might feel that some of these are not essential to who she really is. But even if some are less important than others, and some are strongly relevant to who she is and identifies as, they’re all still interconnected ways in which Lindsey is.

F igures 1 and 2 above represent the network self, Lindsey, at a cross-section of time, say at early to mid-adulthood. What about the changeableness and fluidity of the self? What about other stages of Lindsey’s life? Lindsey-at-age-five is not a spouse or a mother, and future stages of Lindsey might include different traits and relations too: she might divorce or change careers or undergo a gender identity transformation. The network self is also a process .

It might seem strange at first to think of yourself as a process. You might think that processes are just a series of events, and your self feels more substantial than that. Maybe you think of yourself as an entity that’s distinct from relations, that change is something that happens to an unchangeable core that is you. You’d be in good company if you do. There’s a long history in philosophy going back to Aristotle arguing for a distinction between a substance and its properties, between substance and relations, and between entities and events.

However, the idea that the self is a network and a process is more plausible than you might think. Paradigmatic substances, such as the body, are systems of networks that are in constant process even when we don’t see that at a macro level: cells are replaced, hair and nails grow, food is digested, cellular and molecular processes are ongoing as long as the body is alive. Consciousness or the stream of awareness itself is in constant flux. Psychological dispositions or attitudes might be subject to variation in expression and occurrence. They’re not fixed and invariable, even when they’re somewhat settled aspects of a self. Social traits evolve. For example, Lindsey-as-daughter develops and changes. Lindsey-as-mother is not only related to her current traits, but also to her own past, in how she experienced being a daughter. Many past experiences and relations have shaped how she is now. New beliefs and attitudes might be acquired and old ones revised. There’s constancy, too, as traits don’t all change at the same pace and maybe some don’t change at all. But the temporal spread, so to speak, of the self means that how a self as a whole is at any time is a cumulative upshot of what it’s been and how it’s projecting itself forward.

Anchoring and transformation, sameness and change: the cumulative network is both-and , not either-or

Rather than an underlying, unchanging substance that acquires and loses properties, we’re making a paradigm shift to seeing the self as a process, as a cumulative network with a changeable integrity. A cumulative network has structure and organisation, as many natural processes do, whether we think of biological developments, physical processes or social processes. Think of this constancy and structure as stages of the self overlapping with, or mapping on to, one another. For Lindsey, being a sibling overlaps from Lindsey-at-six to the death of the sibling; being a spouse overlaps from Lindsey-at-30 to the end of the marriage. Moreover, even if her sibling dies, or her marriage crumbles, sibling and spouse would still be traits of Lindsey’s history – a history that belongs to her and shapes the structure of the cumulative network.

If the self is its history, does that mean it can’t really change much? What about someone who wants to be liberated from her past, or from her present circumstances? Someone who emigrates or flees family and friends to start a new life or undergoes a radical transformation doesn’t cease to have been who they were. Indeed, experiences of conversion or transformation are of that self, the one who is converting, transforming, emigrating. Similarly, imagine the experience of regret or renunciation. You did something that you now regret, that you would never do again, that you feel was an expression of yourself when you were very different from who you are now. Still, regret makes sense only if you’re the person who in the past acted in some way. When you regret, renounce and apologise, you acknowledge your changed self as continuous with and owning your own past as the author of the act. Anchoring and transformation, continuity and liberation, sameness and change: the cumulative network is both-and , not either-or .

Transformation can happen to a self or it can be chosen. It can be positive or negative. It can be liberating or diminishing. Take a chosen transformation. Lindsey undergoes a gender transformation, and becomes Paul. Paul doesn’t cease to have been Lindsey, the self who experienced a mismatch between assigned gender and his own sense of self-identification, even though Paul might prefer his history as Lindsey to be a nonpublic dimension of himself. The cumulative network now known as Paul still retains many traits – biological, genetic, familial, social, psychological – of its prior configuration as Lindsey, and is shaped by the history of having been Lindsey. Or consider the immigrant. She doesn’t cease to be the self whose history includes having been a resident and citizen of another country.

T he network self is changeable but continuous as it maps on to a new phase of the self. Some traits become relevant in new ways. Some might cease to be relevant in the present while remaining part of the self’s history. There’s no prescribed path for the self. The self is a cumulative network because its history persists, even if there are many aspects of its history that a self disavows going forward or even if the way in which its history is relevant changes. Recognising that the self is a cumulative network allows us to account for why radical transformation is of a self and not, literally, a different self.

Now imagine a transformation that’s not chosen but that happens to someone: for example, to a parent with Alzheimer’s disease. They are still parent, citizen, spouse, former professor. They are still their history; they are still that person undergoing debilitating change. The same is true of the person who experiences dramatic physical change, someone such as the actor Christopher Reeve who had quadriplegia after an accident, or the physicist Stephen Hawking whose capacities were severely compromised by ALS (motor neuron disease). Each was still parent, citizen, spouse, actor/scientist and former athlete. The parent with dementia experiences loss of memory, and of psychological and cognitive capacities, a diminishment in a subset of her network. The person with quadriplegia or ALS experiences loss of motor capacities, a bodily diminishment. Each undoubtedly leads to alteration in social traits and depends on extensive support from others to sustain themselves as selves.

Sometimes people say that the person with dementia who doesn’t know themselves or others anymore isn’t really the same person that they were, or maybe isn’t even a person at all. This reflects an appeal to the psychological view – that persons are essentially consciousness. But seeing the self as a network takes a different view. The integrity of the self is broader than personal memory and consciousness. A diminished self might still have many of its traits, however that self’s history might be constituted in particular.

Plato, long before Freud, recognised that self-knowledge is a hard-won and provisional achievement

The poignant account ‘Still Gloria’ (2017) by the Canadian bioethicist Françoise Baylis of her mother’s Alzheimer’s reflects this perspective. When visiting her mother, Baylis helps to sustain the integrity of Gloria’s self even when Gloria can no longer do that for herself. But she’s still herself. Does that mean that self-knowledge isn’t important? Of course not. Gloria’s diminished capacities are a contraction of her self, and might be a version of what happens in some degree for an ageing self who experiences a weakening of capacities. And there’s a lesson here for any self: none of us is completely transparent to ourselves. This isn’t a new idea; even Plato, long before Freud, recognised that there were unconscious desires, and that self-knowledge is a hard-won and provisional achievement. The process of self-questioning and self-discovery is ongoing through life because we don’t have fixed and immutable identities: our identity is multiple, complex and fluid.

This means that others don’t know us perfectly either. When people try to fix someone’s identity as one particular characteristic, it can lead to misunderstanding, stereotyping, discrimination. Our currently polarised rhetoric seems to do just that – to lock people into narrow categories: ‘white’, ‘Black’, ‘Christian’, ‘Muslim’, ‘conservative’, ‘progressive’. But selves are much more complex and rich. Seeing ourselves as a network is a fertile way to understand our complexity. Perhaps it could even help break the rigid and reductive stereotyping that dominates current cultural and political discourse, and cultivate more productive communication. We might not understand ourselves or others perfectly, but we often have overlapping identities and perspectives. Rather than seeing our multiple identities as separating us from one another, we should see them as bases for communication and understanding, even if partial. Lindsey is a white woman philosopher. Her identity as a philosopher is shared with other philosophers (men, women, white, not white). At the same time, she might share an identity as a woman philosopher with other women philosophers whose experiences as philosophers have been shaped by being women. Sometimes communication is more difficult than others, as when some identities are ideologically rejected, or seem so different that communication can’t get off the ground. But the multiple identities of the network self provide a basis for the possibility of common ground.

How else might the network self contribute to practical, living concerns? One of the most important contributors to our sense of wellbeing is the sense of being in control of our own lives, of being self-directing. You might worry that the multiplicity of the network self means that it’s determined by other factors and can’t be self -determining. The thought might be that freedom and self-determination start with a clean slate, with a self that has no characteristics, social relations, preferences or capabilities that would predetermine it. But such a self would lack resources for giving itself direction. Such a being would be buffeted by external forces rather than realising its own potentialities and making its own choices. That would be randomness, not self-determination. In contrast, rather than limiting the self, the network view sees the multiple identities as resources for a self that’s actively setting its own direction and making choices for itself. Lindsey might prioritise career over parenthood for a period of time, she might commit to finishing her novel, setting philosophical work aside. Nothing prevents a network self from freely choosing a direction or forging new ones. Self-determination expresses the self. It’s rooted in self-understanding.

The network self view envisions an enriched self and multiple possibilities for self-determination, rather than prescribing a particular way that selves ought to be. That doesn’t mean that a self doesn’t have responsibilities to and for others. Some responsibilities might be inherited, though many are chosen. That’s part of the fabric of living with others. Selves are not only ‘networked’, that is, in social networks, but are themselves networks. By embracing the complexity and fluidity of selves, we come to a better understanding of who we are and how to live well with ourselves and with one another.

To read more about the self, visit Psyche , a digital magazine from Aeon that illuminates the human condition through psychology, philosophical understanding and the arts.

Building embryos

For 3,000 years, humans have struggled to understand the embryo. Now there is a revolution underway

John Wallingford

Design and fashion

Sitting on the art

Given its intimacy with the body and deep play on form and function, furniture is a ripely ambiguous artform of its own

Emma Crichton Miller

Learning to be happier

In order to help improve my students’ mental health, I offered a course on the science of happiness. It worked – but why?

Consciousness and altered states

How perforated squares of trippy blotter paper allowed outlaw chemists and wizard-alchemists to dose the world with LSD

Last hours of an organ donor

In the liminal time when the brain is dead but organs are kept alive, there is an urgent tenderness to medical care

Ronald W Dworkin

Stories and literature

Do liberal arts liberate?

In Jack London’s novel, Martin Eden personifies debates still raging over the role and purpose of education in American life

Essays About Self: 5 Essay Examples and 7 Creative Essay Prompts

Essays about self require brainstorming and ample time to reflect on who you are. See our top picks and prompts to use in your essay writing.

“Tell me about yourself.” It’s a familiar question we are asked in social situations, job interviews, or on the first day of class. It’s also a customary essay writing topic in schools to prepare students for future career interviews, cover letters, and, most importantly, to assist individuals in assessing their personalities.

Self refers to qualities of one’s identity or character. It’s a broad topic, but many find it confusing. Before your get started on this topic, learn how to write personal essays to make this challenging topic easier to tackle.

5 Essay Examples

1. essay on defining self by anonymous on wowessays.com, 2. long essay on about myself by prasanna, 3. self discovery: my journey to understanding myself and the world around by anonymous on samplius.com, 4. how my future self is my hero by anonymous on gradesfixer.com, 5. essay on self-respect by bunty rane, 7 writing prompts on essays about self, 1. who am i, 2. a look at my personality, 3. my life: a self-reflection, 4. my best and worst qualities, 5. reasons to write about myself, 6. overcoming challenges and mistakes, 7. the importance of self-awareness.

“Google provided a definition of self as a “person’s essential being that distinguishes them from others, esp. considered as the object of introspection or reflexive action.” (Google.com, 2013) This may be as simple as this, but the word “self” is far more complicated than the things that make an individual different from other people.”

The author defines self as the physical and psychological way of perceiving and evaluating ourselves, which has two aspects. First is the development of an existential self which includes awareness of being different from others. Meanwhile, the second aspect is when someone realizes their categorical self or that they have the same physical characteristics as others.

The essay includes three aspects of self-definition. One is sell-image, or how a person views himself. Two is self-esteem, which dramatically affects how a person values and carries himself. And three is the ideal self, where people compare their self-image with their ideal characteristics, often leading to a new definition of themselves.

“Each person finds their mission differently and has a different journey. Thus, when I write about myself, I write about my journey and what makes the person I am because of the trip. I try to be myself, be passionate about my dreams and hobbies, live honestly, and work hard to achieve all that I want to make.”

Prassana divides her essay into sections: hobbies, dreams, aspirations, and things she wants to learn. Her hobbies are baking and reading books that help her relax. She’s lucky to have parents who let her choose her career where she’ll be happy and stable, which is being a traveler. Prasanna finds learning fun, so she wants to continue learning simple things like cooking specific cuisine, scuba, and sky diving.

“High school has taught me about myself, and that is the most important lesson I could have learned. This metamorphosis has taken me from what I used to be to what I am now.”

In this essay, the writer shows the importance of self-discovery to become a better version of yourself. During their high school days, the author was a typically shy and somewhat childish person who was afraid to speak. So they hid in their room, where they felt safe. But as days pass and they grow older, the writer learns to be strong and stabilize their emotions. Soon, they left their cocoon, managed to express their feelings, and believed in themselves.

Because of self-discovery, the author realized they have their thoughts, ideas, morals, likes, and dislikes. They are no longer afraid of mistakes and have learned to enjoy life. The writer also believes that to succeed, and everyone must trust themselves and not give up on reaching their dreams.

“Bold, passionate, humble these are how I envision my hero to be and these are the three people I want to work on, moving forward as I strive to become the self I want to be in the future.”

The essay shows how a simple award speech by Matthew McConaughey moves the writer’s mind and ultimately creates their hero. They come up with three main qualities they want their future self to have. The first is to be someone who is not afraid to take advantage of any opportunities. Next is to stop being content with just being alive and continue searching for their purpose and genuine passion. Last, they strive to be humble and grateful to every person who contributes to their success.

“People with self-respect have the courage of accepting their mistakes. They exhibit certain toughness, a kind of moral courage, and they display character. Without self-respect, one becomes an unwilling audience of one’s failing both real and imaginary.”

Self-respect is a form of self-love. For Rane, it’s a habit of the mind that will never fail anyone. It’s a ritual that makes a person remember who they are. It reminds us to live without needing anyone else’s approval and walk alone toward our goals. Meanwhile, people with no self-respect hate those who have it. As a result, they become weak and lose their identity.

People can describe who you are in many ways, but the only person who truly knows you is yourself. Use this prompt to introduce yourself to the readers. Share personal and exciting details such as your name’s origin, quirky family routines, and your most memorable moments. It doesn’t have to be too personal. You only need to focus on information that distinguishes you from everyone else.

Personality is a person’s unique way of thinking, feeling, and behavior. You can apply this prompt to describe your personality as a student or working adult. Write about how you develop your skills, make friends, do everyday tasks, and many more. Differentiate “self” and “personality” in your introduction to help readers understand your essay content better.

Connect with your inner self and conduct a self-reflection. This practice helps us grow and improve. In writing this prompt, you will need time to reflect on your life to identify and explain your qualities and values.

For instance, talk about the things you are grateful for, words that best describe you according to the people around you, and areas of yourself that you’d like to improve. Then, discuss how these things affect your life.

Every individual is a work in progress. Although you consider yourself a good person, there are still parts of you that you want to improve. Discuss these shortcomings with your readers. Expound on why people like and dislike these traits. Include how you plan to change your bad characteristics. You can add instances demonstrating your good and bad qualities to make your piece more relatable.

Writing about yourself is a great way to use your creativity in exploring and examining your identity. But, unfortunately, it’s also a great medium to release emotional distress and work through these feelings. So, for this prompt, delve into the benefits of writing about oneself. Then, persuade your readers to start writing about themselves and give tips to help them get started.

For help with this topic, read our guide explaining what is persuasive writing ?

If you want to connect emotionally with your readers, this prompt is the best to use for your essay. Identify and discuss difficult life experiences and explain how these challenging times helped you learn and grow as a person.

Tip : You can use this prompt even if you haven’t faced any life-changing challenges. The problem you may have encountered can be as simple as finding it hard to wake up early.

Some benefits of self-awareness include being a better decision-maker and effective communicator. Define and explain self-awareness. Then, examine how self-awareness influences our lives. You can also include different types of self-awareness and their benefits to a person.

If you want to try these techniques, check out our round-up of the best journals !

Maria Caballero is a freelance writer who has been writing since high school. She believes that to be a writer doesn't only refer to excellent syntax and semantics but also knowing how to weave words together to communicate to any reader effectively.

View all posts

CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS article

“i” and “me”: the self in the context of consciousness.

- Cognition and Philosophy Lab, Department of Philosophy, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

James (1890) distinguished two understandings of the self, the self as “Me” and the self as “I”. This distinction has recently regained popularity in cognitive science, especially in the context of experimental studies on the underpinnings of the phenomenal self. The goal of this paper is to take a step back from cognitive science and attempt to precisely distinguish between “Me” and “I” in the context of consciousness. This distinction was originally based on the idea that the former (“Me”) corresponds to the self as an object of experience (self as object), while the latter (“I”) reflects the self as a subject of experience (self as subject). I will argue that in most of the cases (arguably all) this distinction maps onto the distinction between the phenomenal self (reflecting self-related content of consciousness) and the metaphysical self (representing the problem of subjectivity of all conscious experience), and as such these two issues should be investigated separately using fundamentally different methodologies. Moreover, by referring to Metzinger’s (2018) theory of phenomenal self-models, I will argue that what is usually investigated as the phenomenal-“I” [following understanding of self-as-subject introduced by Wittgenstein (1958) ] can be interpreted as object, rather than subject of experience, and as such can be understood as an element of the hierarchical structure of the phenomenal self-model. This understanding relates to recent predictive coding and free energy theories of the self and bodily self discussed in cognitive neuroscience and philosophy.

Introduction

Almost 130 years ago, James (1890) introduced the distinction between “Me” and “I” (see Table 1 for illustrative quotes) to the debate about the self. The former term refers to understanding of the self as an object of experience, while the latter to the self as a subject of experience 1 . This distinction, in different forms, has recently regained popularity in cognitive science (e.g., Christoff et al., 2011 ; Liang, 2014 ; Sui and Gu, 2017 ; Truong and Todd, 2017 ) and provides a useful tool for clarifying what one means when one speaks about the self. However, its exact meaning varies in cognitive science, especially in regard to what one understands as the self as subject, or “I.”

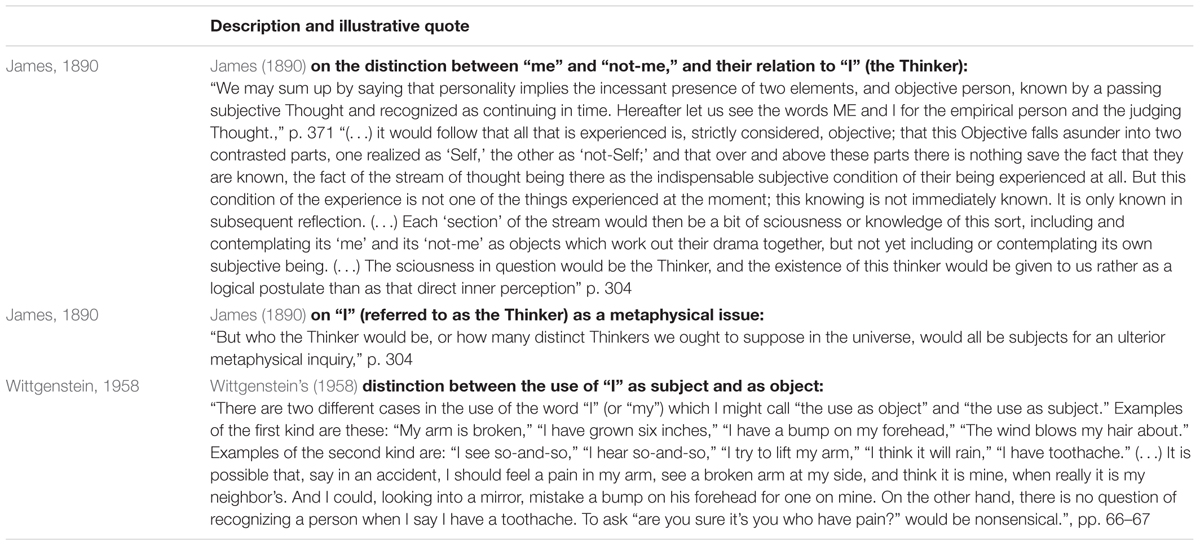

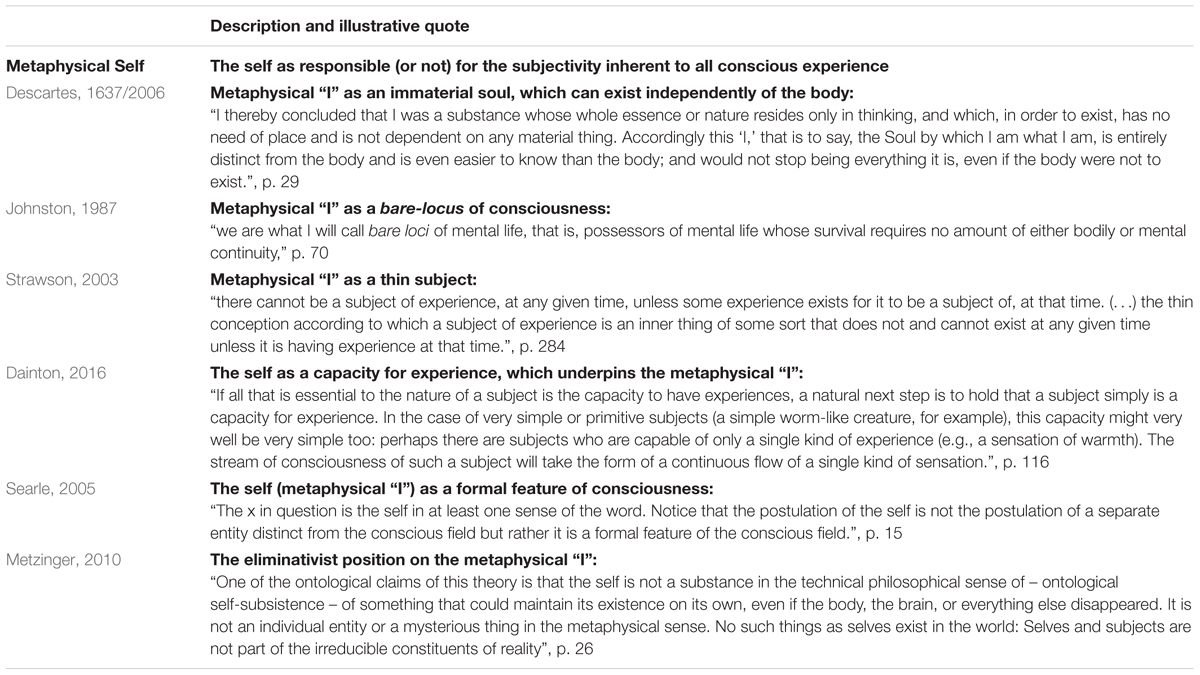

TABLE 1. Quotes from James (1890) illustrating the distinction between self-as-object (“Me”) and self-as-subject (“I”) and a quote from Wittgenstein (1958) illustrating his distinction between the use of “I” as object and as subject.

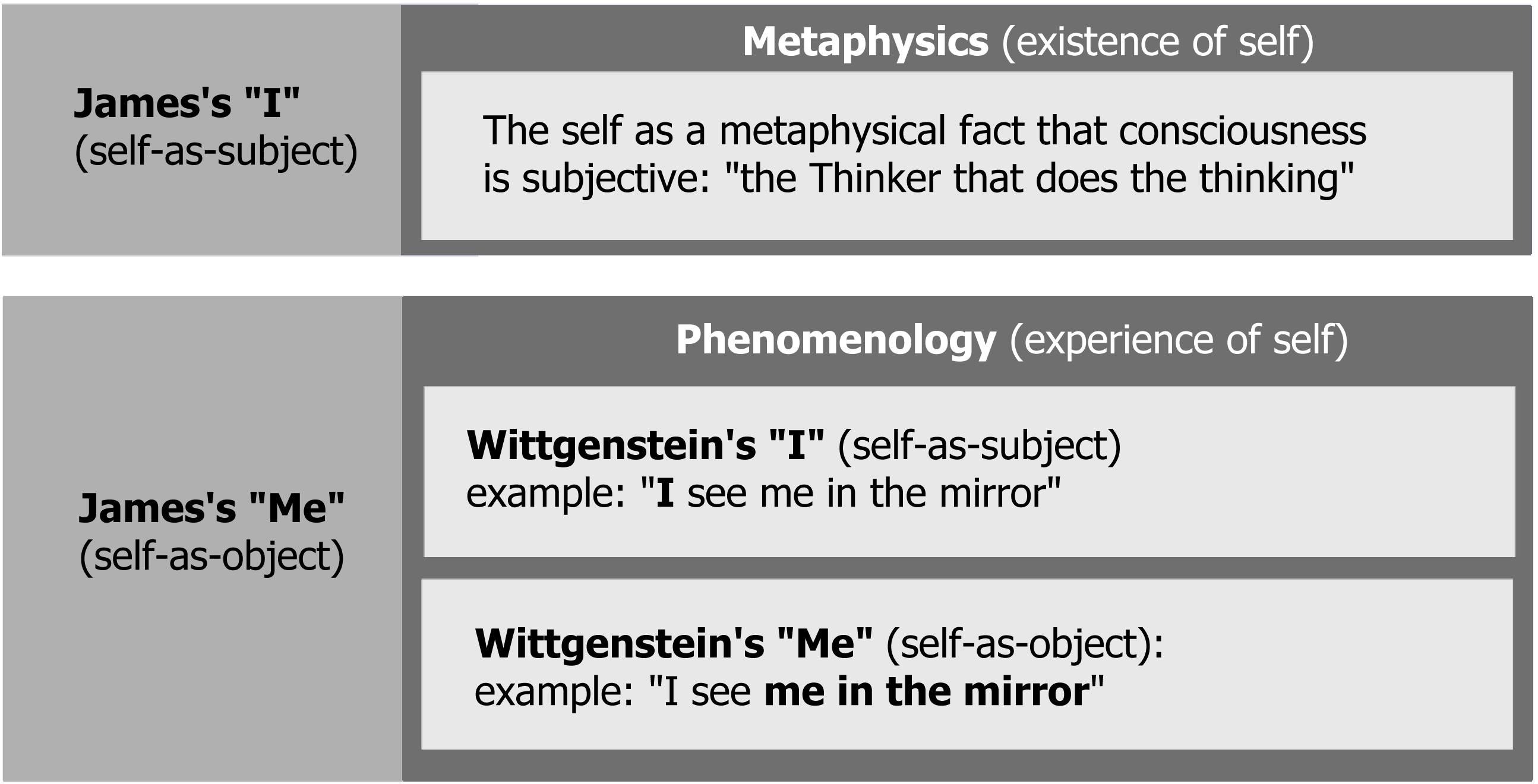

The goal of this paper is to take a step back from cognitive science and take a closer look at the conceptual distinction between “Me” and “I” in the context of consciousness. I will suggest, following James (1890) and in opposition to the tradition started by Wittgenstein (1958) , that in this context “Me” (i.e., the self as object) reflects the phenomenology of selfhood, and corresponds to what is also known as sense of self, self-consciousness, or phenomenal selfhood (e.g., Blanke and Metzinger, 2009 ; Blanke, 2012 ; Dainton, 2016 ). On the other hand, the ultimate meaning of “I” (i.e., the self as subject) is rooted in metaphysics of subjectivity, and refers to the question: why is all conscious experience subjective and who/what is the subject of conscious experience? I will argue that these two theoretical problems, i.e., phenomenology of selfhood and metaphysics of subjectivity, are in principle independent issues and should not be confused. However, cognitive science usually follows the Wittgensteinian tradition 2 by understanding the self-as-subject, or “I,” as a phenomenological, rather than metaphysical problem [Figure 1 illustrates the difference between James (1890) and Wittgenstein’s (1958) approach to the self]. By following Metzinger’s (2003 , 2010 ) framework of phenomenal self-models, and in agreement with a reductionist approach to the phenomenal “I” 3 ( Prinz, 2012 ), I will argue that what is typically investigated in cognitive science as the phenomenal “I” [or the Wittgenstein’s (1958) self-as-subject] can be understood as just a higher-order component of the self-model reflecting the phenomenal “Me.” Table 2 presents some of crucial claims of the theory of self-models, together with concise references to other theories of the self-as-object discussed in this paper.

FIGURE 1. An illustration of James (1890) and Wittgenstein’s (1958) distinctions between self-as-object (“Me”) and self-as-subject (“I”). In the original formulation, James’ (1890) “Me” includes also physical objects and people (material and social “Me”) – they were not included in the picture, because they are not directly related to consciousness.

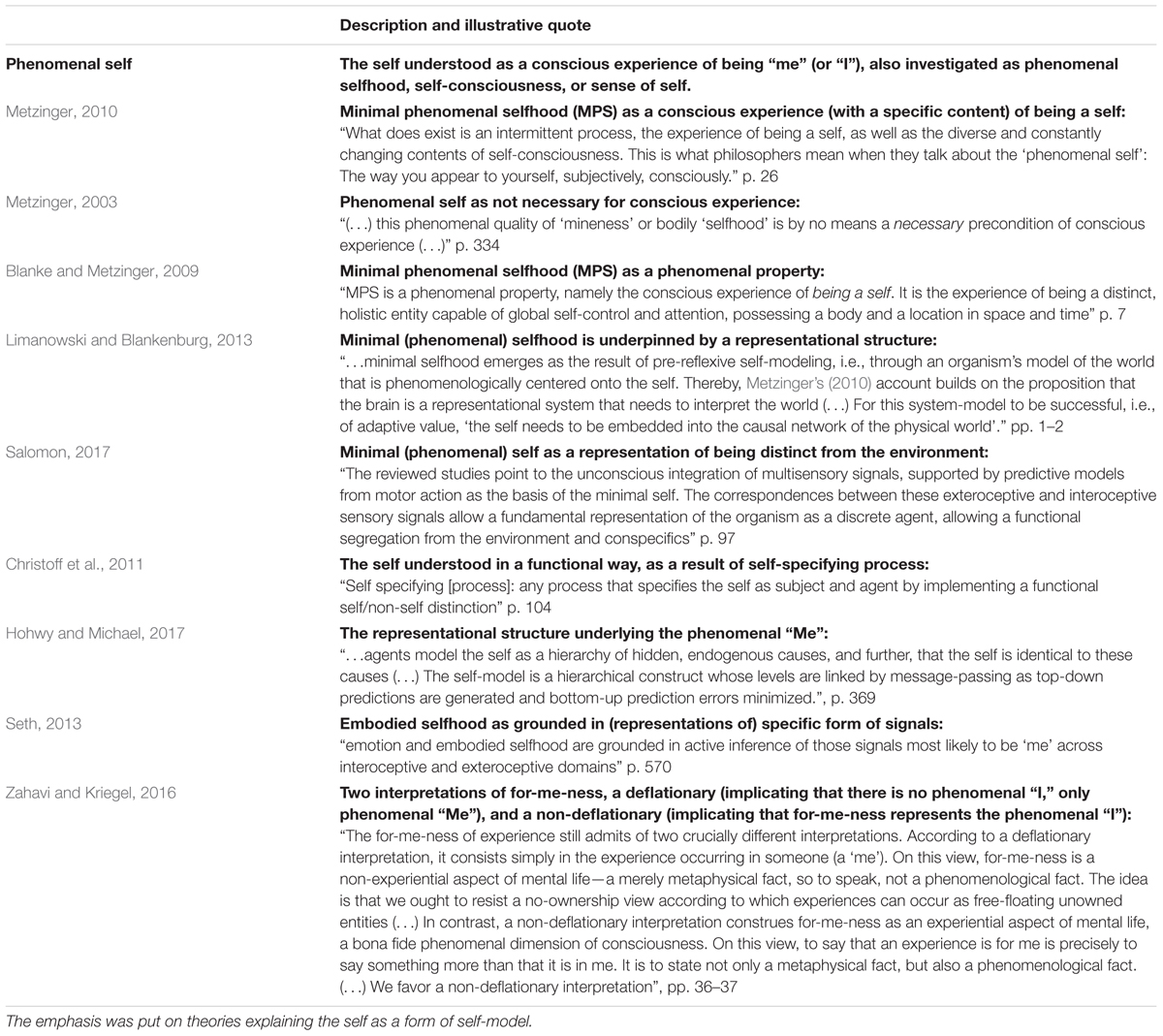

TABLE 2. Examples of theories of the self-as-object (“Me”) in the context of consciousness, as theories of the phenomenal self, with representative quotes illustrating each position.

“Me” As An Object Of Experience: Phenomenology Of Self-Consciousness

The words ME, then, and SELF, so far as they arouse feeling and connote emotional worth, are OBJECTIVE designations, meaning ALL THE THINGS which have the power to produce in a stream of consciousness excitement of a certain particular sort ( James, 1890 , p. 319, emphasis in original).

James (1890) chose the word “Me” to refer to self-as-object. What does it mean? In James’ (1890) view, it reflects “all the things” which have the power to produce “excitement of a certain particular sort.” This certain kind of excitement is nothing more than some form of experiential quality of me-ness, mine-ness, or similar - understood in a folk-theoretical way (this is an important point, because these terms have recently acquired technical meanings in philosophy, e.g., Zahavi, 2014 ; Guillot, 2017 ). What are “all the things”? The classic formulation suggests that James (1890) meant physical objects and cultural artifacts (material self), human beings (social self), and mental processes and content (spiritual self). These are all valid categories of self-as-object, however, for the purpose of this paper I will limit the scope of further discussion only to “objects” which are relevant when speaking about consciousness. Therefore, rather than speaking about, for example, my car or my body, I will discuss only their conscious representations. This limits the scope of self-as-object to one category of “things” – conscious mental content.

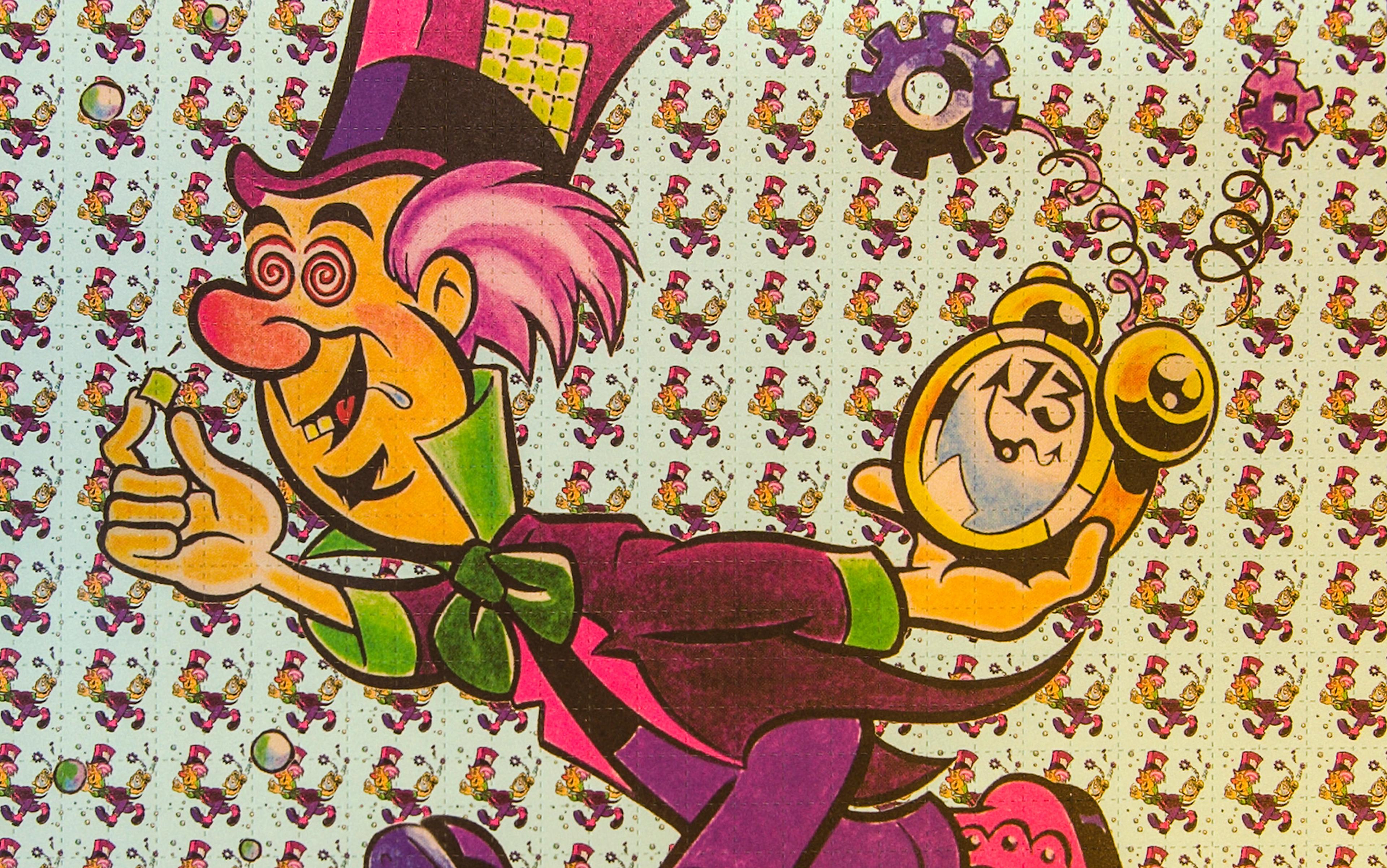

Let us now reformulate James’ (1890) idea in more contemporary terms and define “Me” as the totality of all content of consciousness that is experienced as self-related. Content of consciousness is meant here in a similar way to Chalmers (1996) , who begins “ The conscious mind ” by providing a list of different kinds of conscious content. He delivers an extensive (without claiming that exhaustive) collection of types of experiences, which includes the following 4 : visual; auditory; tactile; olfactory; experiences of hot and cold; pain; taste; other bodily experiences coming from proprioception, vestibular sense, and interoception (e.g., headache, hunger, orgasm); mental imagery; conscious thought; emotions. Chalmers (1996) also includes several other, which, however, reflect states of consciousness and not necessarily content per se , such as dreams, arousal, fatigue, intoxication, and altered states of consciousness induced by psychoactive substances. What is common to all of the types of experience from the first list (conscious contents) is the fact that they are all, speaking in James’ (1890) terms, “objects” in a stream of consciousness: “all these things are objects, properly so called, to the subject that does the thinking” (p. 325).

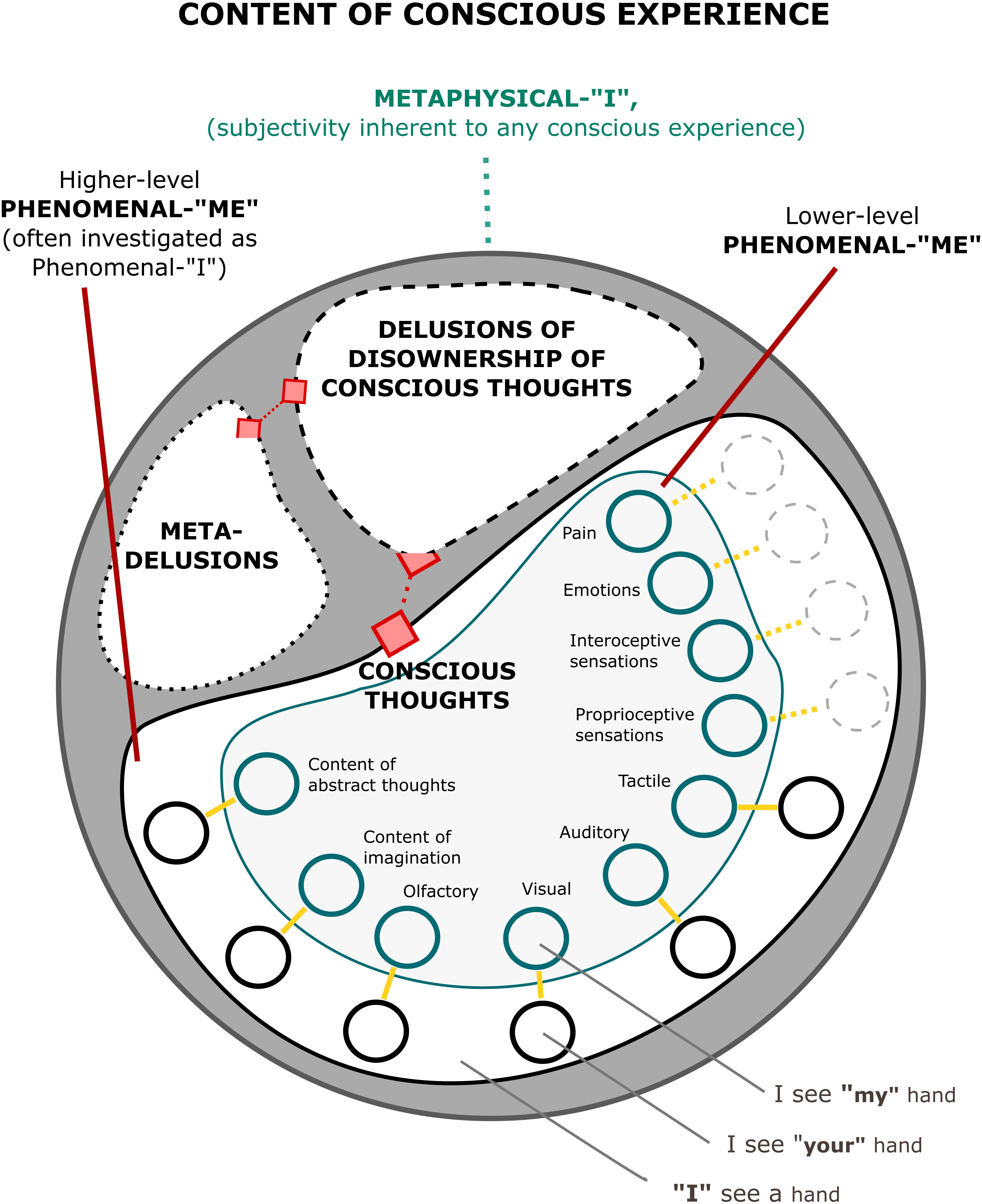

The self understood as “Me” can be understood as a subset of a set of all these possible experiences. This subset is characterized by self-relatedness (Figure 2 ). It can be illustrated with sensory experiences. For example, in the visual domain, I experience an image of my face as different from another person’s face. Hence, while the image of my face belongs to “Me,” the image of someone else does not (although it can be experimentally manipulated, Tsakiris, 2008 ; Payne et al., 2017 ; Woźniak et al., 2018 ). The same can be said about my voice and sounds caused by me (as opposed to voices of other people), and about my smell. We also experience self-touch as different from touching or being touched by a different person ( Weiskrantz et al., 1971 ; Blakemore et al., 1998 ; Schutz-Bosbach et al., 2009 ). There is even evidence that we process our possessions differently ( Kim and Johnson, 2014 ; Constable et al., 2018 ). This was anticipated by James’ (1890) notion of the material “Me,” and is typically regarded as reflecting one’s extended self ( Kim and Johnson, 2014 ). In all of these cases, we can divide sensory experiences into the ones which do relate to the self and the ones which do not. The same can be said about the contents of thoughts and feelings, which can be either about “Me” or about something/someone else.

FIGURE 2. A simplified representation of a structure of phenomenal content including the metaphysical “I,” the phenomenal “Me,” and the phenomenal “I,” which can be understood (see in text) as a higher-level element of the phenomenal “Me.” Each pair of nodes connected with a yellow line represents one type of content of consciousness, with indigo nodes corresponding to self-related content, and black nodes corresponding to non-self-related content. In some cases (e.g., pain, emotions, interoceptive, and proprioceptive sensations), the black nodes are lighter and drawn with a dashed line (the same applies to links), to indicate that in normal circumstances one does not experiences these sensations as representing another person (although it is possible in thought experiments and pathologies). Multisensory/multimodal interactions have been omitted for the sake of clarity. All of the nodes compose the set of conscious thoughts, which can be formulated as “I experience X.” In normal circumstances, one does not deny ownership over these thoughts, however, in thought experiments, and in some cases of psychosis, one may experience that even such thoughts cease to feel as one’s own. This situation is represented by the shape with a dashed outline. Moreover, in special cases one can form meta-delusions, i.e., delusions about delusions – thoughts that my thoughts about other thoughts are not my thoughts (see text for description).

Characterizing self-as-object as a subset of conscious experiences specifies the building blocks of “Me” (which are contents of consciousness) and provides a guiding principle for distinguishing between self and non-self (self-relatedness). However, it is important to note two things. First, the distinction between self and non-self is often a matter of scale rather than a binary classification, and therefore self-relatedness may be better conceptualized as the strength of the relation with the self. It can be illustrated with an example of the “Inclusion of Other in Self” scale ( Aron et al., 1992 ). This scale asks to estimate to what extent another person feels related to one’s self, by choosing among a series of pairs of more-to-less overlapping circles representing the self and another person (e.g., a partner). The degree of overlap between the chosen pair of circles represents the degree of self-relatedness. Treating self-relatedness as a matter of scale adds an additional level of complexity to the analysis, and results in speaking about the extent to which a given content of consciousness represents self, rather than whether it simply does it or not. This does not, however, change the main point of the argument that we can classify all conscious contents according to whether (or to what extent, in that case) they are self-related. For the sake of clarity, I will continue to speak using the language of binary classification, but it should be kept in mind that it is an arbitrary simplification. The second point is that this approach to “Me” allows one to flexibly discuss subcategories of the self by imposing additional constraints on the type of conscious content that is taken into account, as well as the nature of self-relatedness (e.g., whether it is ownership of, agency over, authorship, etc.). For example, by limiting ourselves to discussing conscious content representing one’s body one can speak about the bodily self, and by imposing limits to conscious experience of one’s possessions one can speak about one’s extended self.

Keeping these reservations in mind two objections can be raised to the approach to “Me” introduced here. The first one is as follows:

(1) Speaking about the self/other distinction does not make sense in regard to experiences which are always “mine,” such as prioprioception or interoception. This special status may suggest that these modalities underpin the self as “I,” i.e., the subject of experience.

This idea is present in theoretical proposals postulating that subjectivity emerges based on (representations of) sensorimotor ( Gallagher, 2000 ; Christoff et al., 2011 ; Blanke et al., 2015 ) or interoceptive signals ( Damasio, 1999 ; Craig, 2010 ; Seth et al., 2011 ; Park and Tallon-Baudry, 2014 ; Salomon, 2017 ). There are two answers to this objection. First, the fact that this kind of experience (this kind of content of consciousness) is always felt as “my” experience simply means that all proprioceptive, interoceptive, pain experiences, etc., are as a matter of fact parts of “Me.” They are self-related contents of consciousness and hence naturally qualify as self-as-object. Furthermore, there is no principled reason why the fact that we normally do not experience them as belonging to someone else should transform them from objects of experience (content) into a subject of experience. Their special status may cause these experiences to be perceived as more central aspects of the self than experiences in other modalities, but there is no reason to think that it should change them from something that we experience into the self as an experiencer. Second, even the special status of these sensations can be called into question. It is possible to imagine a situation in which one experiences these kinds of sensations from an organ or a body which does not belong to her or him. We can imagine that with enough training one will learn to distinguish between proprioceptive signals coming from one’s body and those coming from another person’s (or artificial) body. If this is possible, then one may develop a phenomenal distinction between “my” versus “other’s” proprioceptive and interoceptive experiences (for example), and in this case the same rules of classification into phenomenal “Me” and phenomenal “not-Me” will apply as to other sensory modalities. This scenario is not realistic at the current point of technological development, but there are clinical examples which indirectly suggest that it may be possible. For example, people who underwent transplantation of an organ sometimes experience rejection of a transplant. Importantly, patients whose organisms reject an organ also more often experience psychological rejection of that transplant ( Látos et al., 2016 ). Moreover, there are rare cases in which patients following a successful surgery report that they perceive transplanted organs as foreign objects in themselves ( Goetzmann et al., 2009 ). In this case, affected people report experiencing a form of disownership of the implanted organ, suggesting that they may experience interoceptive signals coming from that transplant as having a phenomenal quality of being “not-mine,” leading to similar phenomenal quality as the one postulated in the before-mentioned thought experiment. Another example of a situation in which self-relatedness of interoception may be disrupted may be found in conjoint twins. In some variants of this developmental disorder (e.g., parapagus, dicephalus, thoracopagus) brains of two separate twins share some of the internal organs (and limbs), while others are duplicated and possessed by each twin individually ( Spencer, 2000 ; Kaufman, 2004 ). This provides an inverted situation to the one described in our hypothetical scenario – rather than two pieces of the same organ being “wired” to one person, the same organ (e.g., a heart, liver, stomach) is shared by two individuals. As such it may be simultaneously under control of two autonomous nervous systems. This situation raises challenging questions for theories which postulate that the root of self-as-subject lies in interoception. For example, if conjoint twins share the majority of internal organs, but possess mostly independent nervous systems, like dicephalus conjoint twins, then does it mean that they share the neural subjective frame ( Park and Tallon-Baudry, 2014 )? If the answer is yes, then does it mean that they share it numerically (both twins have one and the same subjective frame), or only qualitatively (their subjective frames are similar to the point of being identical, but they are distinct frames)? However, if interoception is just a part of “Me” then the answer becomes simple – the experiences can be only qualitatively identical, because they are experienced by two independent subjects.

All of these examples challenge the assumption that sensori-motor and interoceptive experiences are necessarily self-related and, as a consequence, that they can form the basis of self-as-subject. For this reason, it seems that signals coming from these modalities are more appropriate to underlie the phenomenal “Me,” for example in a form of background self-experience, or “phenomenal background” ( Dainton, 2008 , 2016 ), rather than the phenomenal “I.”

The second possible objection to the view of self-as-object described in this section is the following one:

(2) My thoughts and feelings may have different objects, but they are always my thoughts and feelings. Therefore, their object may be either “me” or “other,” but their subject is always “I.” As a consequence, even though my thoughts and feelings constitute contents of my consciousness, they underlie the phenomenal “I” and not the phenomenal “Me.”

It seems to be conceptually misguided to speak about one’s thoughts and feelings as belonging to someone else. This intuition motivated Wittgenstein (1958) to write: “there is no question of recognizing a person when I say I have toothache. To ask ‘are you sure it is you who have pains?’ “would be nonsensical” ( Wittgenstein, 1958 ). In the Blue Book, he introduced the distinction between the use of “I” as object and as subject (see Table 1 for a full relevant quote) and suggested that while we can be wrong about the former, making a mistake about the latter is not possible. This idea was further developed by Shoemaker (1968) who introduced an arguably conceptual truth that we are immune to error through misidentification relative to the first-person pronoun, or IEM in short. For example, when I say “I see a photo of my face in front of me” I may be mistaken about the fact that it is my face (because, e.g., it is a photo of my identical twin), but I cannot be mistaken that it is me who is looking at it. One way to read IEM is that it postulates that I can be mistaken about self-as-object, but I cannot be mistaken about self-as-subject. If this is correct then there is a radical distinction between these two types of self that provides a strong argument to individuate them. From that point, one may argue that IEM provides a decisive argument to distinguish between phenomenal “I” (self-as-subject) and phenomenal “Me” (self-as-object).

Before endorsing this conclusion, let us take a small step back. It is important to note that in the famous passage from the Blue Book Wittgenstein (1958) did not write about two distinct types of self. Instead, he wrote about two ways of using the word “I” (or “my”). As such, he was more concerned with issues in philosophy of language than philosophy of mind. Therefore, a natural question arises – to what extent does this linguistic distinction map onto a substantial distinction between two different entities (types of self)? On the face of it, it seems that there is an important difference between these two uses of self-referential words, which can be mapped onto the experience of being a self-as-subject and the experience of being a self-as-object (or, for example, the distinction between bodily ownership and thought authorship, as suggested by Liang, 2014 ). However, I will argue that there are reasons to believe that the phenomenal “I,” i.e., the experience of being a self-as-subject may be better conceptualized as a higher-order phenomenal “Me” – a higher-level self-as-object.

Psychiatric practice provides cases of people, typically suffering from schizophrenia, who describe experiences of dispossession of thoughts, known as delusions of thought insertion ( Young, 2008 ; Bortolotti and Broome, 2009 ; Martin and Pacherie, 2013 ). According to the standard account, the phenomenon of thought insertion does not represent a disruption of sense of ownership over one’s thoughts, but only loss of sense of agency over them. However, the standard account has been criticized in recent years by theorists arguing that thought insertion indeed represents loss of sense of ownership ( Metzinger, 2003 ; Billon, 2013 ; Guillot, 2017 ; López-Silva, 2017 ). One of the main arguments against the standard view is that it runs into serious problems when attempting to explain obsessive intrusive thoughts in clinical population and spontaneous thoughts in healthy people. In both cases, subjects report lack of agency over thoughts, although they never claim lack of ownership over them, i.e., that these are not their thoughts. However, if the standard account is correct, obsessive thoughts should be experienced as belonging to someone else. The fact that they are not suggests that something else must be disrupted in delusions of thought insertion, i.e., sense of ownership 5 over them. If one can lose sense of ownership over one’s thoughts then it has important implications, because then one becomes capable of experiencing one’s thoughts “as someone else’s,” or at least “as not-mine.” However, when I experience my thoughts as not-mine I do it because I’ve taken a stance towards my thoughts, which treats them as an object of deliberation. In other words, I must have “objectified” them to experience that they have a quality of “feeling as if they are not mine.” Consequently, if I experience them as objects of experience, then they cannot form part of my self as subject of experience, because these two categories are mutually exclusive. Therefore, what seemed to constitute a phenomenal “I” turns out to be a part of thephenomenal “Me.”

If my thoughts do not constitute the “I” then how do they fit into the structure of “Me”? Previously, I asserted that thoughts with self-related content constitute “Me,” while thoughts with non-self related content do not. However, just now I argued in favor of the claim that all thoughts (including the ones with non-self-related content) that are experienced as “mine” belong to “Me.” How can one resolve this contradiction?

A way to address this reservation can be found in Metzinger’s (2003 ; 2010 ) self-model theory. Metzinger (2003 , 2010 ) argues that the experience of the self can be understood as underpinned by representational self-models. These self-models, however, are embedded in the hierarchical representational structure, as illustrated by an account of ego dissolution by Letheby and Gerrans (2017) :

Savage suggests that on LSD “[changes] in body ego feeling usually precede changes in mental ego feeling and sometimes are the only changes” (1955, 11), (…) This common temporal sequence, from blurring of body boundaries and loss of sense of ownership for body parts through to later loss of sense of ownership for thoughts, speaks further to the hierarchical architecture of the self-model. ( Letheby and Gerrans, 2017 , p. 8)

If self-models underlying the experience of self-as-object (“Me”) are hierarchical, then the apparent contradiction may be easily explained by the fact that when speaking about the content of thoughts and the thoughts themselves we are addressing self-models at two distinct levels. At the lower level we can distinguish between thoughts with self-related content and other-related content, while on the higher level we can distinguish between thoughts that feel “mine” as opposed to thoughts that are not experienced as “mine.” As a result, this thinking phenomenal “I” experienced in feeling of ownership over one’s thoughts may be conceived as just a higher-order level of Jamesian “Me.” As such, one may claim that there is no such thing as a phenomenal “I,” just multilevel phenomenal “Me.” However, an objection can be raised here. One may claim that even though a person with schizophrenic delusions experiences her thoughts as someone else’s (a demon’s or some malicious puppet master’s), she can still claim that:

Yes, “I” experience my thoughts as not mine, but as demon’s.” My thoughts feel as “not-mine,” however, it’s still me (or: “I”) who thinks of them as “not-mine.”

As such, one escapes “objectification” of “I” into “Me” by postulating a higher-level phenomenal-“I.” However, let us keep in mind that the thought written above constitutes a valid thought by itself. As such, this thought is vulnerable to the theoretical possibility that it turns into a delusion itself, once a psychotic person forms a meta-delusion (delusion about delusion). In this case, one may begin to experience that: “I” (I 1 ) experience that the “fake I” (I 2 ), who is a nasty pink demon, experiences my thoughts as not mine but as someone else’s (e.g., as nasty green demon’s). In this case, I may claim that the real phenomenal “I” is I 1 , since it is at the top of the hierarchy. However, one may repeat the operation of forming meta-delusions ad infinitum (as may happen in psychosis or drug-induced psychedelic states) effectively transforming each phenomenal “I” into another “fake-I” (and consequently making it a part of “Me”).

The possibility of meta-delusions illustrates that the phenomenal “I” understood as subjective thoughts is permanently vulnerable to the threat of losing the apparent subjective character and becoming an object of experience. As such it seems to be a poor choice for the locus of subjectivity, since it needs to be constantly “on the run” from becoming treated as an object of experience, not only in people with psychosis, but also in all psychologically healthy individuals if they decide to reflect on their thoughts. Therefore, it seems more likely that the thoughts themselves cannot constitute the subject of experience. However, even in case of meta-delusions there seems to be a stable deeper-level subjectivity, let us call it the deep “I,” which is preserved, at least until one loses consciousness. After all, a person who experiences meta-delusions would be constantly (painfully) aware of the process, and often would even report it afterwards. This deep “I” cannot be a special form of content in the stream of consciousness, because otherwise it would be vulnerable to becoming a part of “Me.” Therefore, it must be something different.

There seem to be two places where one can look for this deep “I”: in the domain of phenomenology or metaphysics. The first approach has been taken by ( Zahavi and Kriegel, 2016 ) who argue that “all conscious states’ phenomenal character involves for-me-ness as an experiential constituent.” It means that even if we rule out everything else (e.g., bodily experiences, conscious thoughts), we are still left with some form of irreducible phenomenal self-experience. This for-me-ness is not a specific content of consciousness, but rather “refers to the distinct manner, or how , of experiencing” ( Zahavi, 2014 ).

This approach, however, may seem inflationary and not satisfying (e.g., Dainton, 2016 ). One reason for this is that it introduces an additional phenomenal dimension, which may lead to uncomfortable consequences. For example, a question arises whether for-me-ness can ever be lost or replaced with the “ how of experiencing” of another person. For example, can I experience my sister’s for-me-ness in my stream of consciousness? If yes, then how is for-me-ness different from any other content of consciousness? And if the answer is no, then how is it possible to distil the phenomenology of for-me-ness from the metaphysical fact that a given stream of consciousness is always experienced by this and not other subject?

An alternative approach to the problem of the deep “I” is to reject that the subject of experience, the “I,” is present in phenomenology (like Hume, 1739/2000 ; Prinz, 2012 ; Dainton, 2016 ), and look for it somewhere else, in the domain of metaphysics. Although James (1890) did not explicitly formulate the distinction between “Me” and “I” as the distinction between the phenomenal and the metaphysical self, he hinted at it at several points, for example when he concluded the Chapter on the self with the following fragment: “(...) a postulate, an assertion that there must be a knower correlative to all this known ; and the problem who that knower is would have become a metaphysical problem” ( James, 1890 , p. 401).

“I” As A Subject Of Experience: Metaphysics Of Subjectivity

Thoughts which we actually know to exist do not fly about loose, but seem each to belong to some one thinker and not to another ( James, 1890 , pp. 330–331).

Let us assume that phenomenal consciousness exists in nature, and that it is a part of the reality we live in. The problem of “I” emerges once we realize that one of the fundamental characteristics of phenomenal consciousness is that it is always subjective, that there always seems to be some subject of experience. It seems mistaken to conceive of consciousness which do “fly about loose,” devoid of subjective character, devoid of being someone’s or something’s consciousness. Moreover, it seems that subjectivity may be one of the fundamental inherent properties of conscious experience (similar notions can be found in: Berkeley, 1713/2012 ; Strawson, 2003 ; Searle, 2005 ; Dainton, 2016 ). It seems highly unlikely, if not self-contradictory, that there exists something like an objective conscious experience of “what it is like to be a bat” ( Nagel, 1974 ), which is not subjective in any way. This leads to the metaphysical problem of the self: why is all conscious experience subjective, and what or who is the subject of this experience? Let us call it the problem of the metaphysical “I,” as contrasted with the problem of the phenomenal “I” (i.e., is there a distinctive experience of being a self as a subject of experience, and if so, then what is this experience?), which we discussed so far.

The existence of the metaphysical “I” does not entail the existence of the phenomenal self. It is possible to imagine a creature that possesses a metaphysical “I,” but does not possess any sense of self. In such a case, the creature would possess consciousness, although it would not experience anything as “me,” nor entertain any thoughts/feelings, etc., as “I.” In other words, it is a possibility that one may not experience self-related content of consciousness, while being a sentient being. One example of such situation may be the experience of a dreamless sleep, which “is characterized by a dissolution of subject-object duality, or (…) by a breakdown of even the most basic form of the self-other distinction” ( Windt, 2015 ). This is a situation which can be regarded as an instance of the state of minimal phenomenal experience – the simplest form of conscious experience possible ( Windt, 2015 ; Metzinger, 2018 ), in which there is no place for even the most rudimentary form of “Me.” Another example may be the phenomenology of systems with grid-like architectures which, according to the integrated information theory (IIT, Tononi et al., 2016 ), possess conscious experience 6 . If IIT is correct, then these systems experience some form of conscious states, which most likely lack any phenomenal distinction between “Me” and “not-Me.” However, because they may possess a stream of conscious experience, and conscious experience is necessarily subjective, there remains a valid question: who or what is the subject of that experience?