ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Unemployment, employability and covid19: how the global socioeconomic shock challenged negative perceptions toward the less fortunate in the australian context.

- 1 Research School of Population Health, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia

- 2 Institute of Child Protection Studies, The Australian Catholic University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 3 Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Unemployed benefit recipients are stigmatized and generally perceived negatively in terms of their personality characteristics and employability. The COVID19 economic shock led to rapid public policy responses across the globe to lessen the impact of mass unemployment, potentially shifting community perceptions of individuals who are out of work and rely on government income support. We used a repeated cross-sections design to study change in stigma tied to unemployment and benefit receipt in a pre-existing pre-COVID19 sample ( n = 260) and a sample collected during COVID19 pandemic ( n = 670) by using a vignette-based experiment. Participants rated attributes of characters who were described as being employed, working poor, unemployed or receiving unemployment benefits. The results show that compared to employed characters, unemployed characters were rated substantially less favorably at both time points on their employability and personality traits. The difference in perceptions of the employed and unemployed was, however, attenuated during COVID19 with benefit recipients perceived as more employable and more Conscientious than pre-pandemic. These results add to knowledge about the determinants of welfare stigma highlighting the impact of the global economic and health crisis on perception of others.

Introduction

The onset of COVID19 pandemic saw unemployment climb to the highest rate since the Great Depression in many regions globally 1 . Over just one month, from March to April 2020 unemployment rate in the United States increased from 4.4% to over 14.7% and in Australia the effective rate of unemployment increased from 5.4 to 11.7% ( Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020 ) 2 . In Australia, a number of economic responses were rapidly introduced including a wage subsidy scheme (Jobkeeper) to enable employees to keep their employees connected to the workforce, one-off payments to many welfare recipients, and a doubling of the usual rate of the unemployment benefits (Jobseeker payment) through a new Coronavirus supplement payment. At the time of writing in July 2020, many countries, including Australia remain in the depths of a health and economic crisis.

A rich research literature from a range of disciplines has documented the pervasive negative community views toward those who are unemployed and receiving unemployment benefits, with the extent of this “welfare stigma” being particularly pronounced in countries with highly targeted benefit systems such as the United States and Australia ( Fiske et al., 2002 ; Baumberg, 2012 ; Contini and Richiardi, 2012 ; Schofield and Butterworth, 2015 ). The stigma and potential discrimination associated with unemployment and benefit receipt are known to have negative impacts on health, employability and equality (for meta-analyses, see Shahidi et al., 2016 ). In addition, the receipt of unemployment benefits co-occurs with other stigmatized characteristics such as poverty and unemployment ( Schofield and Butterworth, 2018a ). The changing context related to the COVID19 crisis provides a novel opportunity to better understand the determinants of stigmatizing perceptions of unemployment and benefit receipt.

Negative community attitudes and perceptions of benefit recipients are commonly explained by the concept of “deservingness” ( van Oorschot and Roosma, 2017 ). The unemployed are typically seen as less deserving of government support than other groups because they are more likely to be seen as responsible for their own plight, ungrateful for support, not in genuine need ( Petersen et al., 2011 ; van Oorschot and Roosma, 2017 ), and lacking reciprocity (i.e., seen as taking more than they have given – or will give – back to society; van Oorschot, 2000 ; Larsen, 2008 ; Petersen et al., 2011 ; Aarøe and Petersen, 2014 ). Given the economic shock associated with COVID19, unemployment and reliance on income support are less likely to seen as an outcome within the individuals control and may therefore amplify perceptions of deservingness. Prior work has shown that experimentally manipulating perceived control over circumstances does indeed change negative stereotypes ( Aarøe and Petersen, 2014 ).

A number of experimental paradigms have been used to investigate perceptions of “welfare recipients” and the “unemployed.” The stereotype content model (SCM; Fiske et al., 2002 ), for example, represents the stereotypes of social groups on two dimensions: warmth, relating to being friendly and well–intentioned (rather than ill–intentioned); and competence, relating to one’s capacity to pursue intentions ( Fiske et al., 2002 ). Using this model, the “unemployed” have been evaluated as low in warmth and competence across a variety of welfare regime types ( Fiske et al., 2002 ; Bye et al., 2014 ). The structure of stereotypes has also been studied using the Big Five personality dimensions ( Schofield and Butterworth, 2018b ; Schofield et al., 2019 ): Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Emotional Stability (for background on the Big Five see: Goldberg, 1993 ; Hogan et al., 1996 ; Saucier and Goldberg, 1996 ; McCrae and Terracciano, 2005 ; Srivastava, 2010 ; Chan et al., 2012 ; Löckenhoff et al., 2014 ). There are parallels between the Big Five and the SCM: warmth relating to the dimension of Agreeableness, and competence relating to Conscientiousness ( Digman, 1997 ; Ward et al., 2006 ; Cuddy et al., 2008 ; Abele et al., 2016 ) and these constructs have been found to predict employability and career success ( Barrick et al., 2001 ; Cuesta and Budría, 2017 ). Warmth and agreeableness have also been linked to the welfare-specific characteristics of deservingness ( Aarøe and Petersen, 2014 ).

The term “employability” has been previously defined as a set of achievements, skills and personal attributes that make a person more likely to gain employment and leading to success in their chosen career pathway ( Pegg et al., 2012 ; O’Leary, 2017 , 2019 ). While there are few studies examining perceptions of others, perceptions of one’s own employability have been recently studied in university students, jobseekers ( Atitsogbe et al., 2019 ) and currently employed workers ( Plomp et al., 2019 ; Yeves et al., 2019 ), consistently showing higher levels of perceived employability being linked to personal and job-related wellbeing as well as career success. Examining other’s perceptions of employability may be more relevant to understand factors impacting on actual employment outcomes. A majority of studies examining other’s perceptions of employability have focused on job specific skills study ( Lowden et al., 2011 ; Dhiman, 2012 ; Saad and Majid, 2014 ).

Building on this previous work, our own research has focused on the effects of unemployment by drawing on frameworks of Big Five, SCM and employability in pre-COVID19 samples ( Schofield and Butterworth, 2018b ; Schofield et al., 2019 ). Our studies consistently show that unemployed individuals receiving government payments are perceived as less employable (poorer “quality” workers and less desirable for employment) and less Conscientious. We found similar but weaker pattern related to Agreeableness, Emotional Stability, and the extent that a person is perceived as “uniquely human” ( Schofield et al., 2019 ). Further, we found that vignette characters described as currently employed but with a history of welfare receipt were indistinguishable from those described as employed and with no reference to benefit receipt ( Schofield et al., 2019 ). Findings such as this provide experimental evidence that welfare stigma is malleable and can be challenged by information inconsistent with negative stereotype ( Schofield and Butterworth, 2018b ; Schofield et al., 2019 ; see also Petersen et al., 2011 ).

The broad aim of the current study was to extend this previous work by examining the impact of COVID19 on person perceptions tied to employment and benefit recipient status. It repeats a pre-COVID19 study of an Australian general population sample in the COVID19 context, drawing on the same sampling frame, materials and study design to maximize comparability. The study design recognizes that the negative perceptions of benefit recipients may reflect a combination of difference sources of stigma: poverty, lack of work, and benefit receipt. Therefore, the original study used four different conditions to seek to differentiate these different sources: (1) Employed ; (2) Working poor ; (3) Unemployed ; and (4) Unemployed benefit recipient . Finally, for the COVID19 sample we added a novel fifth condition: (5) Unemployment benefit recipient also receiving the “Coronavirus” supplement . We except that the reference to a payment specifically applicable to the COVID19 context may lead to more favorable perceptions (more deserving) than the other unemployed and benefit receipt characters.

The study capitalizes on a major exogenous event, the COVID19 crisis, which we hypothesize will alter perceptions of deservingness by fundamentally challenging social identities and perceptions of one’s own vulnerability to unemployment. The study tests three hypotheses, and in doing so makes an important empirical and theoretical contribution to understanding how deservingness influences person perception, and understanding of the potential “real world” barriers experienced by people seeking employment in the COVID19 context.

Hypothesis 1

The pre-COVID19 assessment uses a subset of data from a pre-registered study, but this reuse of the data was not preregistered 3 . We hypothesize that, at Time 1 (pre-COVID19 assessment) we will find that employed characters will be rated more favorably than characters described as unemployed and receiving unemployment benefits, particularly on dimensions of Conscientiousness, Worker and Boss suitability. Moreover, we expect a gradient in perceptions across the four experimental conditions, from employed to working poor, to unemployed to unemployed receiving benefits and to show a similar trend for the other outcome measures included in the study.

Hypothesis 2

We hypothesize that the character in the unemployed condition(s) would be rated less negatively relative to the employed condition(s) at Time 2, compared to Time 1. We predict a two-way interaction between time and condition for the key measures (Conscientiousness, Worker and Boss suitability) and a similar trend on other outcomes.

Hypothesis 3

We expect that explicit reference to the unemployed benefit character receiving the “Coronavirus supplement” payment will increase the salience of the COVID19 context and lead to more positive ratings of this character relative to the standard unemployed benefit condition in the pre-COVID19 and COVID19 occasions.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

Two general population samples (pre-COVID19 and COVID19) were recruited from the same source: The Australian Online Research Unit (ORU) panel. The ORU is an online survey platform that provides access to a cohort of members of the general public who are interested in contributing to research. The ORU randomly selects potential participants who meet study eligibility criteria, and provides the participant with an incentive for their participation. The sample for the Time 1 (pre-COVID19) occasion was part of a larger study (768 participants) collected in November 2018. From this initial dataset, we were able to use data from 260 (50.1% female, M Age = 42.1 [16.7] years, range: 18–82) participants who were presented with the one vignette scenario that we could replicate at the time of the social restrictions applicable in the COVID19 context (i.e., the vignette character was not described as going out and visiting friends, as these behaviors were illegal at Time 2). The sample for Time 2 (COVID19) was collected in May–June 2020, at the height of the lock down measures in Australia and included 670 participants (40.5% female, M Age = 51.0 [15.8] years, range: 18–85). The two samples were broadly similar (see below), though the proportion of male participants at Time 2 was greater than at Time 1.

The pre-COVID assessment at Time 1 was restricted to those participants who completed the social-distancing consistent vignette in the first place to avoid potential order/context effects. This provided, on average, 65 respondents in each of the four experimental conditions. Using the results from our previous published studies as indicators of effect size ( Schofield and Butterworth, 2018b ; Schofield et al., 2019 ). Monte Carlo simulation was used to identify the Time 2 sample size that would provide 90% power to detect an interaction effect that represented a 50% decline in the difference between the two employment and two unemployment conditions on the three-key measures at the COVID occasion relative to the pre-COVID difference. This sample size of 135 per condition also provided between 60 and 90% power to detect a difference of a similar magnitude between the employed and unemployment benefit conditions across the two measurement occasions. Given previous evidence that the differences between employed and unemployed/welfare conditions is robust and large for Conscientiousness and Worker suitability ( Schofield and Butterworth, 2018b ), the current study is also adequately powered to detect the most replicable effects of unemployment and welfare on perceptions of a person’s character (even in the absence of the hypothesized interaction effect).

Materials and Procedure

The procedures were identical on both study occasions. Participants read a brief vignette that described a fictional character, and then rated the character on measures reflecting personality dimensions, their suitability as a worker or boss, morality, warmth, and competence, and the participant’s beliefs the character should feel guilt and shame, or feel angry and disgusted. At Time 1 (pre-COVID19 context) participants then repeated this process with a second vignette, but we do not consider data from the second vignette.

Manipulation

The key experimental conditions were operationalized by a single sentence embedded within the vignette that was randomly allocated to different participants (employed: “S/he is currently working as a sales assistant in a large department store”; working poor: “S/he is currently working as a sales assistant, on a minimum-wage, in a large department store”; unemployed: “S/he is currently unemployed”; and receipt of unemployment benefits: “S/he is currently unemployed, and is receiving government benefits due to his/her unemployment”). The four experimental conditions were identical at both time points. At Time 2, an additional COVID19-specific condition was included (to maximize the salience of the COVID19 context): “S/he is currently unemployed and is receiving government benefits, including the Coronavirus supplement, due to his/her unemployment.”

All three study conditions will imply poverty/low income. In Australia, few minimum-wage jobs are supplemented by tips, and so a minimum-wage job indicates a level of relative poverty. A full-time worker in a minimum wage job is in the bottom quartile of income earners ( Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2017 ). Prior to the COVID19 crisis and the increase in payment level, a single person with no dependents receiving unemployment benefits received approximately 75% of the minimum-wage in cash assistance. During COVID19 and at the time of the data collection, the rate of pay exceeds the minimum-wage.

Several characteristics of the vignette character, including age and relationship status, were balanced across study participants. Age was specified as either 27 or 35 years, relationship status was either “single” or “lives with his/her partner.” The character’s gender was also varied and names were stereotypically White.

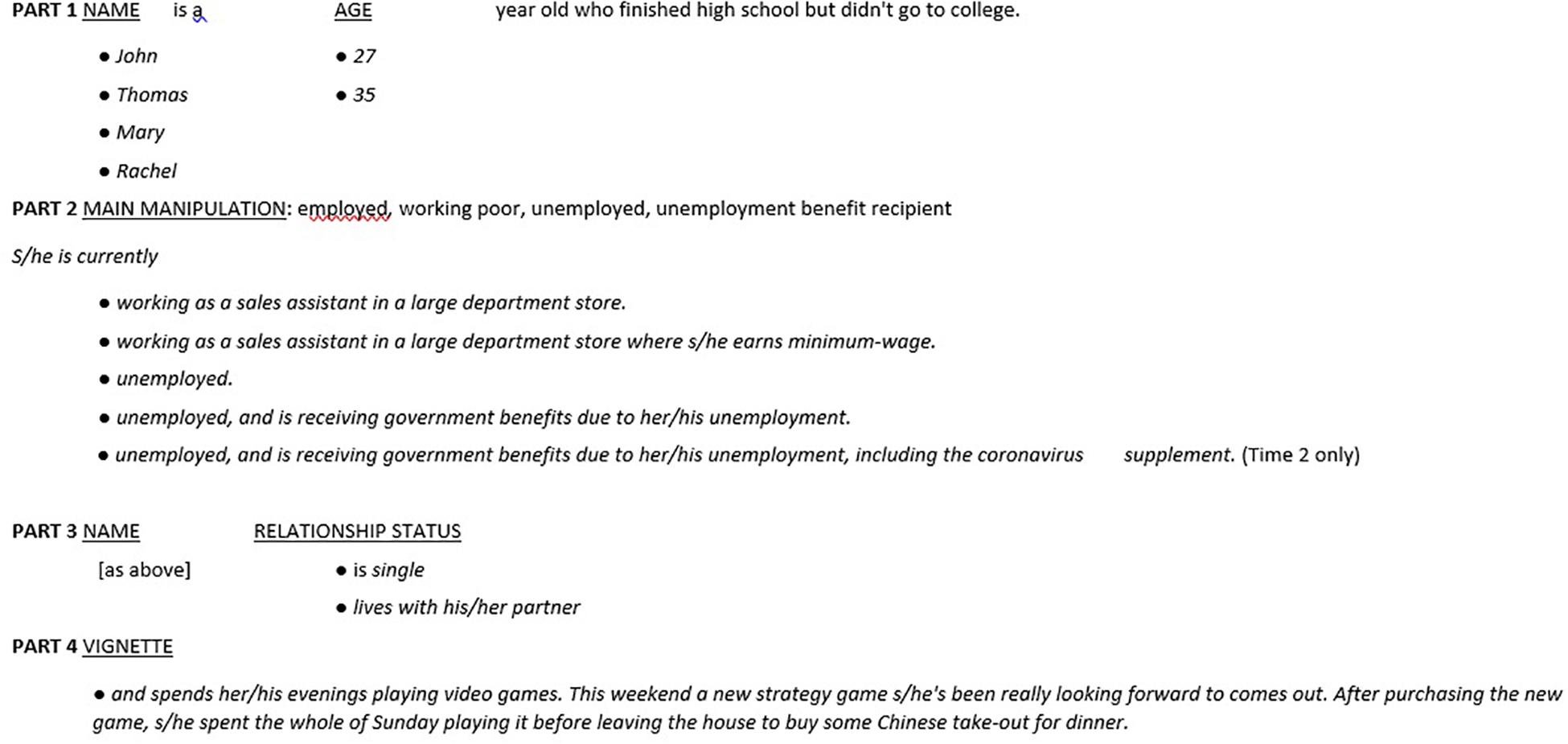

For Time 1, manipulated characteristics yielded 32 unique vignettes, comprised of four key experimental conditions (employed, working poor, unemployed, and unemployment benefits) × 2 ages × 2 genders × 2 relationship statuses. For Time 2, manipulated characteristics yielded 40 unique vignettes, comprised of five key experimental conditions (employed, working poor, unemployed, unemployment benefits, and unemployed + coronavirus supplement) × 2 ages × 2 genders × 2 relationship statuses. The vignette template construction is presented in Figure 1 including each component of the vignette that was randomly varied.

Figure 1. Outline of vignette construction in 4 parts. Bullet pointed options replace the underlined text, with gendered pronouns in each option selected to match character name.

Comprehension Checks

In both studies, participants were required to affirm consent after debriefing or had their data deleted. Participant comprehension of the vignettes was checked via three free-response comprehension questions about the character’s age and weekend activities. Participants who did not answer any questions correctly were not able to continue the study.

Outcome Measures

Personality, employability (suitability as a worker or boss), communion and agency, cognitive and emotional moral judgments, and dehumanization were included as the study outcomes. While not all personality or character dimension measures can be considered as negative or positive, higher scores were used in the study to indicate more “favorable” perceptions by the participants of the characters.

Personality

The Ten Item Personality Inventory was used to measure the Big Five ( Gosling et al., 2003 ) and adapted to other–oriented wording (i.e., “I felt like the person in the story was…”) ( Schofield et al., 2019 ). Two items measured each trait via two paired attributes. One item contained positive attributes and one contained negative attributes. Participants indicated the extent to which “I think [Name] is [attributes]” from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The order of these 10 items was randomized. Agreeableness (α = 0.54) was assessed from “sympathetic, warm” and “critical, quarrelsome” (reversed); Extraversion (α = 0.50) was assessed from “extraverted, enthusiastic” and “reserved, quiet” (reversed); Conscientiousness (α = 0.76) was assessed from “dependable, self-disciplined” and “disorganized, careless” (reversed); Openness to experience (α = 0.36) was assessed from “open to new experiences, complex” and “conventional, uncreative” (reversed); Emotional stability (α = 0.65) was assessed from “calm, emotionally stable.” and “anxious, easily upset” (reversed). The order of these 10 items was randomized.

Employability

Single item measures: “I think [Name] would be a good worker” ( Worker suitability ) and “I think [Name] would be a good boss” ( Boss suitability ) were rated on the same scale as the personality measure. The order of these two items was randomized. Higher scores indicated better employability.

Communion and Agency

Communion and agency was assessed using Bocian et al. (2018) adaptation of Abele et al. (2016) scale that measures the fundamental dimensions of communion and agency using two-subscales for each dimension. The morality and warmth subscales are seen as measures of communion (referred to as warmth in SCM; Fiske, 2018 ); while the competence and assertiveness subscales measure agency (what Fiske refers to as competence in SCM; Fiske, 2018 ). This subscale structure has been identified in multiple samples. Participants indicated the extent to which “I think [Name] [attributes]” from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much so). Morality (α = 0.92) was measured with six items, e.g., “is just,” “is fair”; Warmth (α = 0.96) with six items, e.g., “is caring,” “is empathetic”; Competence (α = 0.90) with five items, e.g., “is efficient,” “is capable”; and Assertiveness (α = 0.83) with six items, e.g., “is self-confident,” “stands up well under pressure.” These items were presented in a random order.

Dehumanization

Dehumanization was measured with a composite scale of two-items drawn from Bastian et al. (2013) . Based on prior research, we measured dehumanization with two items: “I think [Name] is mechanical and cold, like a robot” and “I think [Name] lacked self-restraint, like an animal” order of these two items was randomized. We reverse coded the two items for the analyses for consistency for the other variables, so that higher scores were indicative of more favorable perceptions.

Moral Emotions

Moral emotions were measured by four items that asked about emotional responses to the character that were framed as self-condemning or other-condemning ( Haidt, 2003 ; Giner-Sorolla and Espinosa, 2011 ). Two other-condemning items asked the participant about their own emotional response to the character in the vignette (Anger: “[Name]’s behavior makes me angry”; Disgust: “I think [Name] is someone who makes me feel disgusted,” α = 0.92). The two self-condemning items asked about the character’s emotional response (Guilt: “[Name] should feel guilty about [his/her] behavior”; Shame: “I think [Name] should feel ashamed of [him/her]self”; α = 0.95). We reverse coded the two scales to ensure consistency with other variables, with higher scores indicative of more favorable perceptions.

Analytical Strategy

With the exception of the Moral emotion (and Communion and Agency) scales that are new to this study and the previously tested Openness to Experience, our previous research has demonstrated differences between the ratings of employed and unemployed characters on the included outcome measures ( Schofield and Butterworth, 2018b ; Schofield et al., 2019 ). We undertake the analysis using a four-step process. We use mixed-effects multi-level models, with the 14 outcome measures nested within participants, and predicted by fixed (between-person) terms representing the experimental “Condition,” “Time” (pre-/COVID19) and their interaction, and controlling for measure differences and allowing for random effects at the participant level: i) We initially assessed the effect of condition in the pre-COVID19 occasion to establish the baseline pattern of results; ii) we then evaluated the interaction term and, specifically, the extent to which the baseline difference observed between employment and unemployment conditions is attenuated at Time 2 (COVID19 occasion); iii) we tested the three-way interaction between condition, occasion and measure to assess whether this two-way interaction varies across the outcome measures; and if significant iv) repeated the modeling approach using separate linear regression models for each outcome measure. Our initial model contrasts the two employed (employed and working poor) and unemployed (unemployed and benefit receipt) conditions. The second model examines the four separate vignette conditions separately, differentiating between unemployed and unemployed benefit conditions. Finally, we contrast the three unemployment benefit conditions: (1) unemployment benefit recipients at Time 1; (2) unemployment benefit recipients at Time 2; and (3) unemployment benefit recipients receiving the Coronavirus payment at Time 2. For all models, we consider unadjusted and adjusted results (controlling for participant demographics). To address a potential bias from gender differences between samples, post-stratification weights were calculated for the COVID19 sample to reflecting the gender by age distribution of the pre-COVID19 sample. All models were weighted.

The two samples from Time 1 (pre-COVID19) and Time 2 (COVID19) were comparable on all demographic variables, except for gender (χ 2 [1, 923] = 7.04, p < 0.001) and employment (χ 2 [1, 910] = 27.66, p < 0.001): The gender distribution was more balanced at Time 1 with 49.8% of males, compared to 59.5% of males at Time 2. There was also a significant increase in unemployment with 20.9% of Time 1 participants out of work compared to 39.3% of the Time 2 participants. This was likely reflective of the employment rate nearly doubling in Australia during COVID19 crisis. Bivariate correlations showed significant positive correlations between all 14 outcomes ( p ’s < 0.001), except for Extraversion that was only positively correlated with Emotional Stability, boss suitability, warmth, assertiveness, and competence ( p’ s < 0.05).

Contrasting Employed and Unemployed Characters

The results, both adjusted and unadjusted, from the initial overall multilevel model using a binary indicator of whether vignette characters were employed (those in the employed or working poor conditions) or unemployed (unemployed or welfare) and testing the interaction between vignette Condition and Time (pre-COVID19 vs COVID19) are presented in the Supplementary Table S1 . The adjusted results (holding participant age, gender, employment, and education constant) indicated that the unemployed characters were rated lower than the employed characters at Time 1 ( b = −0.57). This difference in the ratings of employed and unemployed characters was reduced in the COVID19 assessment at Time 2, declining from 0.57 to 0.26, across all the outcome measures. The addition of the three-way interaction between Condition, Time and outcome measure significantly improved overall model fit, χ 2 (52) = 482.94, p < 0.001, indicating the interaction between Condition and Time varied over measures.

A series of separate regression models considering each outcome separately (see Supplementary Table S2 ) showed a significant effect of Condition (employment rated higher than unemployment) at Time 1 (pre-COVID) for all outcomes except Openness and Extraversion. The lower ratings for unemployed relative to employed characters were significantly moderated at Time 2 on the Competence, Worker and Boss suitability, and Guilt/Shame outcomes ( p’ s < 0.05).

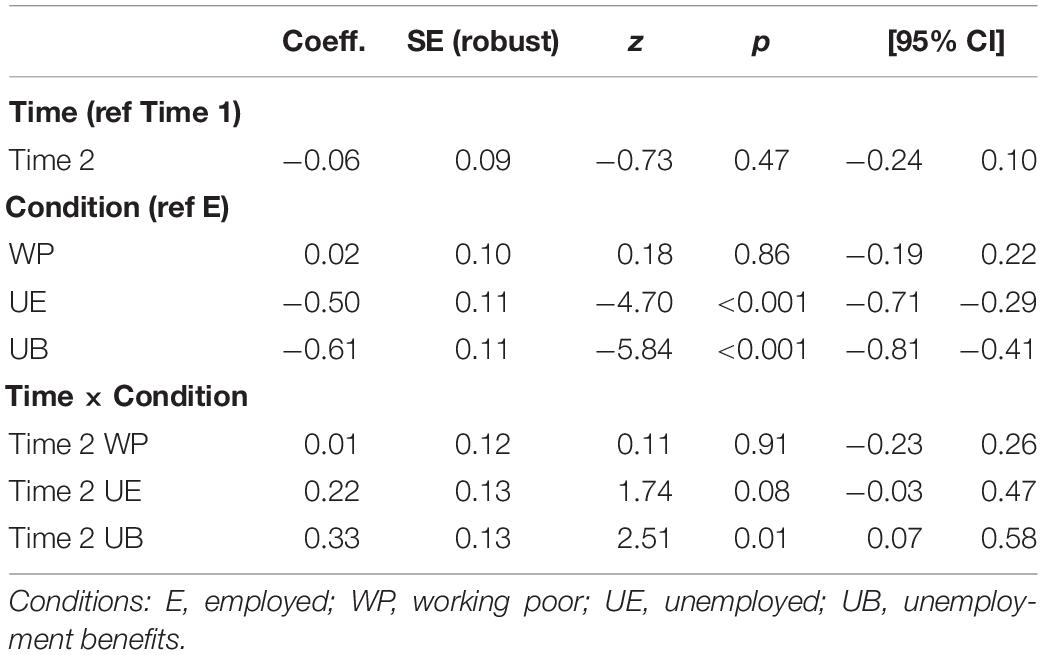

COVID19 and Perceptions of Unemployment Benefit Recipients

The next set of analyses consider the four separate vignette conditions, differentiating between the unemployed and unemployed benefit recipient conditions. The overall mixed-effects multilevel model incorporating the four distinct vignette conditions provided evidence of significant effects for Condition and Condition by Time in both adjusted and unadjusted models. The result for the adjusted model ( Table 1 ), averaged across the various outcomes, replicated the previous finding of a difference in ratings of employed and unemployed characters at Time 1 (pre-COVID19): relative to the employed condition, there was no difference in ratings of the working poor, but the unemployed and the unemployed benefit recipient characters were rated less favorably. There was some evidence of a gradient across the unemployed characters: the average rating of the unemployed condition was higher than the unemployed benefit condition, though this difference was not statistically significant. In the presence of the interaction effect, the non-significant effect of Time shows that, averaged across all the outcome measures, there was no difference in the rating of the characters in the employed condition on the pre-COVID19 and COVID19 occasions. We tested for the effect of sociodemographic characteristics as covariates in the adjusted models (employment and benefit receipt status, education, age, and gender) but found no main effects of any of the covariates except for gender: females tended to rate characters higher ( b = 0.13, 95% CI [0.04, 0.21]) compared to males. Testing the heterogeneity of these patterns across outcomes via the inclusion of a three-way interaction between vignette condition, occasion and measure significantly improved overall model fit, χ 2 (104) = 533.40, p < 0.001, prompting analysis of each outcome separately.

Table 1. Adjusted fixed effects estimates of outcomes as a function of interactions between condition and time.

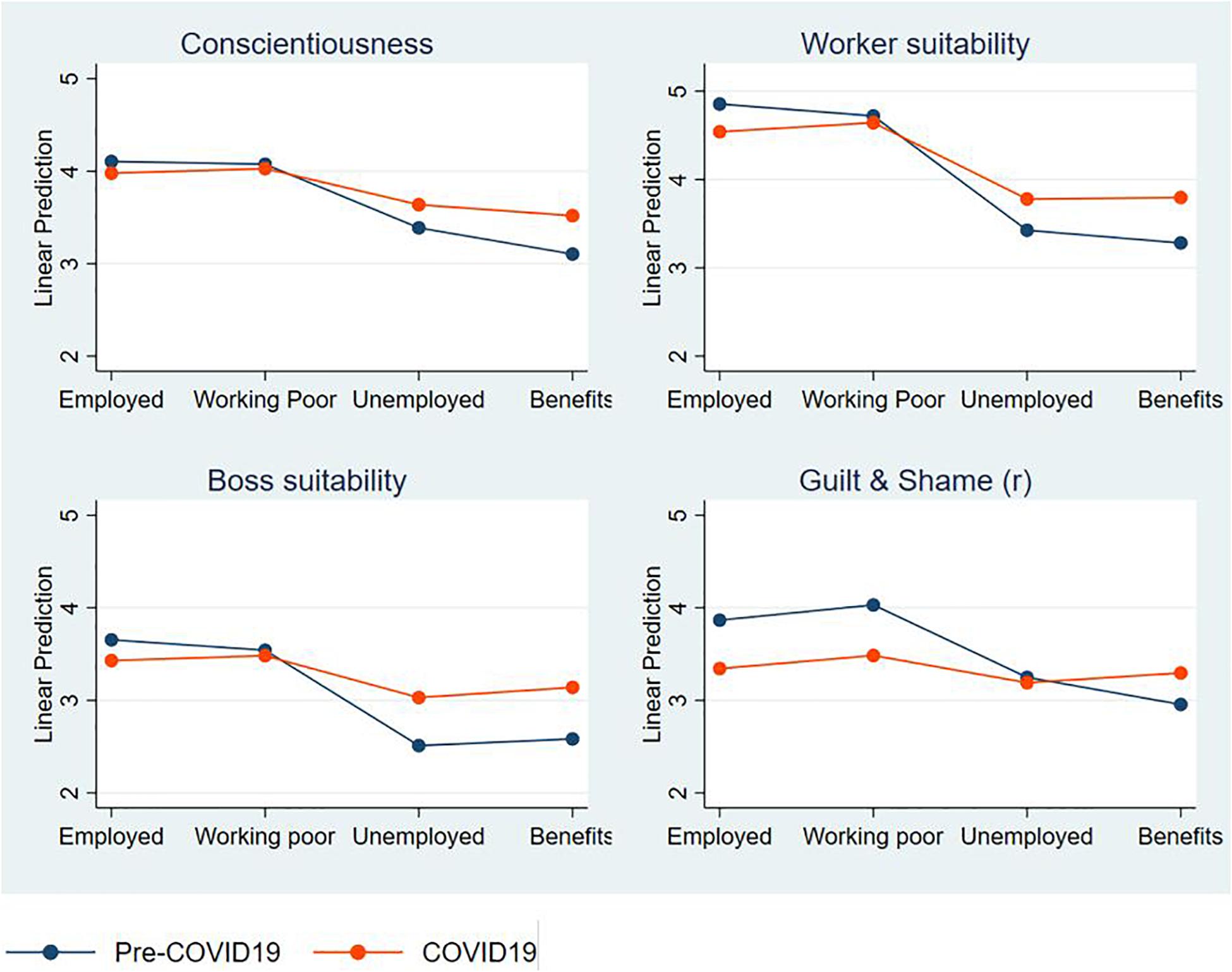

The separate linear regressions for each outcome measure ( Supplementary Table S3 ) show that ratings of unemployed benefit recipients at the Time 1 (pre-COVID19) were significantly lower than the employed characters for all outcomes except Openness and Extraversion. Statistically significant Condition by Time terms indicated that the unemployed benefit effect was moderated at Time 2 (COVID19) for the three key outcome measures identified in previous research (Conscientiousness, Worker and Boss suitability) and for the measure of Guilt and Shame. Figure 2 depicts this interaction for these four outcomes. These occurred in two profiles. For Conscientiousness, Worker and Boss suitability, COVID19 attenuated the negative perceptions of unemployed relative to employed characters, providing support for Hypothesis 2. By contrast, COVID19 has induced a new difference, such that participants thought employed characters should feel higher levels Guilt and Shame at Time 2, compared to Time 1. While the “working poor” condition was not central to the COVID19 hypotheses, we note that we found no evidence that ratings of these characters on any outcome differed from the standard employed character, or that this difference was changed in assessment at Time 2 (COVID19 occasion).

Figure 2. Interaction effect of Time (COVID19) by Condition marginal mean ratings on four outcomes: Conscientiousness, Worker suitability, Boss suitability, and Guilt and Shame (reversed).

The Impact of COVID19 on Perceptions of Unemployment Benefit-Recipients

The inclusion of the fifth COVID19-specific unemployment benefit condition did not generate more positive (or different) ratings than the standard unemployment benefit condition. Overall mixed-effects multilevel models, both adjusted and unadjusted, indicated that participants in the Coronavirus supplement condition (adjusted model: b = 0.26, 95% CI [0.06, 0.45]) and the general unemployed benefit recipient condition at Time 2 (adjusted model: b = 0.28, 95% CI [0.08, 0.48]) were both rated more favorably in comparison to unemployed benefit recipients at Time 1. There was no difference between these two Time 2 benefit recipient groups ( b = 0.03, 95% CI [−0.12, 0.19]). These results did not support hypothesis 3.

Previous research has demonstrated that people who are unemployed, and particularly those receiving unemployment benefits, are perceived more negatively and less employable than those who are employed. However, the economic shock associated with the COVID19 crisis is likely to have challenged people’s sense of their own vulnerability and risk of unemployment, and altered their perceptions of those who are unemployed and receiving government support. The broad aim of the current study was to examine the potential effect of this crisis on person perceptions tied to employment and benefit recipient status. We did this by presenting brief vignettes describing fictional characters, manipulating key experimental conditions related to employment status, and asking study participants to rate the characters’ personality and capability. We contrasted results from two cross-sectional general population samples collected before and during the COVID19 crisis.

The pre-COVID19 assessment replicated our previous findings (e.g., Schofield and Butterworth, 2018b ) showing that employed characters are perceived more favorably than those who were unemployed and receiving government benefits on measures of Conscientiousness and suitability as a worker. These findings supported Hypothesis 1. In comparison, the assessment conducted during the COVID19 crisis showed that unemployed and employed characters were viewed more similarly on these same key measures, with a significant interaction effect providing support for Hypothesis 2. Our third hypothesis, suggesting that n reference to the Coronavirus Supplement (an additional form of income support introduced during the pandemic) would enhance ratings of unemployed benefit recipients at the second assessment occasion, was not supported. We found that benefit recipients at Time 2 were rated more favorably than the benefit group at Time 1, irrespective of whether this COVID19-specific payment was referenced. This suggests the broader context in which the study was conducted was responsible for the change in perceptions.

We sampled participants from the same population, used identical experimental procedures, and found no difference over time in the ratings of employed characters on the key outcome measures of employability (Worker and Boss suitability) and Conscientiousness. The more favorable ratings of unemployed and benefit receiving characters at Time 2 is likely to reflect how the exogenous economic shock brought about by the COVID19 crisis challenged social identities and the stereotypes held of others 4 . The widespread impact and uncontrollable nature of this event are inconsistent with pre-COVID19 views that attribute ill-intent to those receiving to unemployment benefits ( Fiske et al., 2002 ; Baumberg, 2012 ; Contini and Richiardi, 2012 ; Bye et al., 2014 ). We suggest the changing context altered perceptions of the “deservingness” of people who are unemployed as unemployment in the context of COVID19 is less indicative personal failings or a result of one’s “own doing” ( Petersen et al., 2011 ; van Oorschot and Roosma, 2017 ). It is important to recognize, however, that the negative perceptions of unemployed benefit recipients were attenuated in the COVID19 assessment, but they continued to be rated less favorably than those who were employed on the key outcome measures.

In contrast to our findings on the key measures of employability and Conscientiousness, the previous and current research is less conclusive for the other outcome measures. The current study showed a broadly consistent gradient in the perception of employed and unemployed characters for all outcome measures apart from Openness and Extraversion. Findings on these other measures have been weaker and inconsistent across previous studies ( Schofield and Butterworth, 2018b ; Schofield et al., 2019 ), and the current experiment was not designed with sufficient power to demonstrate interaction effects for these measures. There was, however, one measure that showed significant divergence from the expected profile of results. A significant interaction term suggested that study participants at the Time 2 (COVID19) assessment reported that the employed characters should feel greater levels of Guilt and Shame than those who participated in the pre-COVID19 assessment. In contrast, there was consistency in the ratings of unemployed characters on this measure across the two assessment occasions. While not predicted, these results are also interpretable in the context of the pervasive job loss that accompanied the COVID19 crisis. Haller et al. (2020) , for example, argue that the highly distressing, morally difficult, and cumulative nature of COVID19 related stressors presents a perfect storm to result in a guilt and shame responses. The context of mass job losses may leave “surviving” workers feeling increasingly guilty.

The main findings of the current study are consistent with previous experimental studies that show that the stereotypes of unemployed benefit recipients are malleable ( Aarøe, 2011 ; Schofield et al., 2019 ). These previous studies, however, have demonstrated malleability by providing additional information about unemployed individuals that was inconsistent with the unemployed benefit recipient stereotype (e.g., the external causes of their unemployment). In contrast, the current study did not change how the vignette characters were presented or the experimental procedures. Rather, we assessed how the changing context in which study participants were living had altered their perceptions: suggesting the experience of COVID19 altered stereotypical views held by study participants rather than presenting information about the character that would challenge the applicability of the benefit recipient stereotype in this instance.

Perceptions and stereotypes of benefit recipients can be reinforced (and potentially generated) by government actions and policies. Structural stigma can be used as a policy tool to stigmatize benefit receipt as a strategy to reduce dependence on income support and encourage workforce participation ( Moffitt, 1983 ; Stuber and Schlesinger, 2006 ; Baumberg, 2012 ; Contini and Richiardi, 2012 ; Garthwaite, 2013 ). In the current instance, however, the Australian government acted quickly to provide greater support to Australians who lost their jobs (e.g., doubling the rate of payment, removing mandatory reporting to the welfare services) and this may have reduced the stigmatizing structural features of the income support system and contributed to the changed perceptions of benefit recipients identified in this study.

Limitations

The current study took advantage of a natural experimental design and replicated a pre-COVID19 study during the COVID19 crisis. The study is limited by the relatively small sample size at Time 1, which was not designed for current purposes but part of another study. We were not able to include most of the participants from the original Time 1 study as most of the experimental conditions described activities that were illegal/inconsistent with recommend activity at the time of the COVID19 lockdown and social restriction measures. Finally, the data collection for the current study occurred very quickly after the initial and sudden COVID19 lockdowns and economic shock, which is both a strength and a limitation for the generalizability of the results. The pattern of results using the same sampling frame offers compelling support for our hypothesis that the shared economic shock and increase in unemployment attenuates stigmatizing community attitudes toward those who need to receive benefits. Our current conclusions would be further strengthened by a subsequent replication when the public health and economic crises stabilize, to test whether pre-COVID perceptions return.

The current study provides novel information about impact of the COVID19 health and economic crisis, and the impact of the corresponding policy responses on community perceptions. This novel study shows how community perceptions of employment and benefit recipient status have been altered by the COVID19 pandemic. These results add to knowledge about the determinants of welfare stigma, particularly relating to employability, highlighting societal level contextual factors.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Melbourne University Human Research Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

AS led the review conceptualized by TS and PB. AS and PB conducted the analyses and wrote up the review. TS led the data collection, reviewed and edited the manuscript, and provided data management support. This manuscript is based on previous extensive work by TS and PB on stereotypes toward the unemployed and welfare benefit recipients. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was funded by the Australian Research Council (ARC) grant # DP16014178.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.594837/full#supplementary-material

- ^ https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/UNRATE

- ^ The Australian figure includes individuals working zero hours who had “no work, not enough work available or were stood down.” The US Bureau of Labor Statistics noted that some people on temporary layoff were not classified as such and the unemployment rate could have been almost 5 percentage points higher.

- ^ https://osf.io/wknb6

- ^ https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/our-changing-identities-under-covid-19

Aarøe, L. (2011). Investigating frame strength: the case of episodic and thematic frames. Polit. Commun . 28, 207–226. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2011.568041

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Aarøe, L., and Petersen, M. B. (2014). Crowding out culture: scandinavians and Americans agree on social welfare in the face of deservingness cues. J. Polit. 76, 684–697. doi: 10.1017/S002238161400019X

Abele, A. E., Hauke, N., Peters, K., Louvet, E., Szymkow, A., and Duan, Y. (2016). Facets of the fundamental content dimensions: agency with competence and assertiveness—Communion with warmth and morality. Front. Psychol. 7:1810. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01810

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Atitsogbe, K. A., Mama, N. P., Sovet, L., Pari, P., and Rossier, J. (2019). Perceived employability and entrepreneurial intentions across university students and job seekers in Togo: the effect of career adaptability and self-efficacy. Front. Psychol. 10:180. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00180

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2017). Characteristics of Employment. Australia: Labour Force.

Google Scholar

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2020). Employment and unemployment: International Perspective. Australia: Labour Force.

Barrick, M. R., Mount, M. K., and Judge, T. A. (2001). Personality and performance at the beginning of the new millennium: what do we know and where do we go next? Int. J. Select. Assess. 9, 9–30. doi: 10.1111/1468-2389.00160

Bastian, B., Denson, T. F., and Haslam, N. (2013). The roles of dehumanization and moral outrage in retributive justice. PLoS One 8:e61842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061842

Baumberg, B. (2012). Three ways to defend welfare in Britain. J. Poverty Soc. Just. 20, 149–161. doi: 10.1332/175982712X652050

Bocian, K., Baryla, W., Kulesza, W. M., Schnall, S., and Wojciszke, B. (2018). The mere liking effect: attitudinal influences on attributions of moral character. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 79, 9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2018.06.007

Bye, H. H., Herrebrøden, H., Hjetland, G. J., Røyset, G. Ø, and Westby, L. L. (2014). Stereotypes of norwegian social groups. Scand. J. Psychol. 55, 469–476. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12141

Chan, W., McCrae, R. R., De Fruyt, F., Jussim, L., Löckenhoff, C. E., De Bolle, M., et al. (2012). Stereotypes of age differences in personality traits: universal and accurate? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 103, 1050–1066. doi: 10.1037/a0029712

Contini, D., and Richiardi, M. G. (2012). Reconsidering the effect of welfare stigma on unemployment. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 84, 229–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2012.02.010

Cuddy, A. J., Fiske, S. T., and Glick, P. (2008). Warmth and competence as universal dimensions of social perception: the stereotype content model and the BIAS map. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 40, 61–149. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(07)00002-0

Cuesta, M. B., and Budría, S. (2017). Unemployment persistence: how important are non-cognitive skills? J. Behav. Exp. Econom. 69, 29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2017.05.006

Dhiman, M. C. (2012). Employers’ perceptions about tourism management employability skills. Anatolia 23, 359–372. doi: 10.1080/13032917.2012.711249

Digman, J. M. (1997). Higher-order factors of the big five. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 73:1246.

Fiske, S. T. (2018). Stereotype content: warmth and competence endure. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 27, 67–73. doi: 10.1177/0963721417738825

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J., Glick, P., and Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 82:878. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.878

Garthwaite, K. (2013). Fear of the brown envelope: exploring welfare reform with long-term sickness benefits recipients. Soc. Pol. Administration. 48, 782–798. doi: 10.1111/spol.12049

Giner-Sorolla, R., and Espinosa, P. (2011). Social cuing of guilt by anger and of shame by disgust. Psychol. Sci. 22, 49–53. doi: 10.1177/0956797610392925

Goldberg, L. R. (1993). The structure of phenotypic personality traits. Am. Psychol. 48:26. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.48.1.26

Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., and Swann, W. B. Jr. (2003). A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. J. Res. Personal. 37, 504–528. doi: 10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1

Haidt, J. (2003). The moral emotions. Handb. Affect. Sci. 11, 852–870.

Haller, M., Norman, S. B., Davis, B. C., Capone, C., Browne, K., and Allard, C. B. (2020). A model for treating COVID-19–related guilt, shame, and moral injury. Psychol. Trauma 12, S174–S176.

Hogan, R., Hogan, J., and Roberts, B. W. (1996). Personality measurement and employment decisions: questions and answers. Am. Psychol. 51:469. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.51.5.469

Larsen, K. (2008). Knowledge network hubs and measures of research impact, science structure, and publication output in nanostructured solar cell research. Scientometrics 74, 123–142. doi: 10.1007/s11192-008-0107-2

Löckenhoff, C. E., Chan, W., McCrae, R. R., De Fruyt, F., Jussim, L., De Bolle, M., et al. (2014). Gender stereotypes of personality: universal and accurate? J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 45, 675–694. doi: 10.1177/0022022113520075

Lowden, K., Hall, S., Elliot, D., and Lewin, J. (2011). Employers’ Perceptions of the Employability Skills of New Graduates. London: Edge Foundation.

McCrae, R. R., and Terracciano, A. (2005). Universal features of personality traits from the observer’s perspective: data from 50 cultures. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 88, 547–561. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.547

Moffitt, R. (1983). An economic model of welfare stigma. Am. Econom. Rev. 75, 1023–1035.

O’Leary, S. (2017). Graduates’ experiences of, and attitudes towards, the inclusion of employability-related support in undergraduate degree programmes; trends and variations by subject discipline and gender. J. Educ. Work 30, 84–105. doi: 10.1080/13639080.2015.1122181

O’Leary, S. (2019). Gender and management implications from clearer signposting of employability attributes developed across graduate disciplines. Stud. Higher Educ. 1–20. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2019.1640669

Pegg, A., Waldock, J., Hendy-Isaac, S., and Lawton, R. (2012). Pedagogy for Employability. York: Higher Education Academy.

Petersen, M. B., Slothuus, R., Stubager, R., and Togeby, L. (2011). Deservingness versus values in public opinion on welfare: the automaticity of the deservingness heuristic. Eur. J. Political Res. 50, 24–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2010.01923.x

Plomp, J., Tims, M., Khapova, S. N., Jansen, P. G., and Bakker, A. B. (2019). Psychological safety, job crafting, and employability: a comparison between permanent and temporary workers. Front. Psychol. 10:974.

Saad, M. S. M., and Majid, I. A. (2014). Employers’ perceptions of important employability skills required from Malaysian engineering and information and communication technology (ICT) graduates. Global J. Eng. Educ. 16, 110–115.

Saucier, G., and Goldberg, L. R. (1996). “The language of personality: lexical perspectives,” in On the Five-factor Model of Personality: Theoretical Perspectives , ed. J. S. Wiggins (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 21–50.

Schofield, T. P., and Butterworth, P. (2015). Patterns of welfare attitudes in the Australian population. PLoS One 10:0142792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142792

Schofield, T. P., and Butterworth, P. (2018a). Are negative community attitudes toward welfare recipients associated with unemployment? evidence from an australian cross-sectional sample and longitudinal cohort. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 9, 503–515. doi: 10.1177/1948550617712031

Schofield, T. P., and Butterworth, P. (2018b). Community attitudes toward people receiving unemployment benefits: does volunteering change perceptions? Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 40, 279–292. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2018.1496335

Schofield, T. P., Haslam, N., and Butterworth, P. (2019). The persistence of welfare stigma: does the passing of time and subsequent employment moderate the negative perceptions associated with unemployment benefit receipt? J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 49, 563–574. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12616

Shahidi, F., Siddiqi, A., and Muntaner, C. (2016). Does social policy moderate the impact of unemployment on health? a multilevel analysis of 23 welfare states. Eur. J. f Public Health 26, 1017–1022. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckw050

Srivastava, S. (2010). The five-factor model describes the structure of social perceptions. Psychol. Inquiry 21, 69–75. doi: 10.1080/10478401003648815

Stuber, J., and Schlesinger, M. (2006). Sources of stigma for means-tested government programs. Soc. Sci. Med. 63, 933–945. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.01.012

van Oorschot, W. (2000). Who should get what, and why? on deservingness criteria and the conditionality of solidarity among the public. Pol. Pol. 28, 33–48. doi: 10.1332/0305573002500811

van Oorschot, W., and Roosma, F. (2017). The Social Legitimacy of Targeted Welfare. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Ward, L. C., Thorn, B. E., Clements, K. L., Dixon, K. E., and Sanford, S. D. (2006). Measurement of agency, communion, and emotional vulnerability with the Personal Attributes Questionnaire. J. Pers. Assess . 86, 206–216. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8602_10

Yeves, J., Bargsted, M., Cortes, L., Merino, C., and Cavada, G. (2019). Age and perceived employability as moderators of job insecurity and job satisfaction: a moderated moderation model. Front. Psychol. 10:799. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00799

Keywords : COVID19, employability, personality, Big Five, public policy, unemployment

Citation: Suomi A, Schofield TP and Butterworth P (2020) Unemployment, Employability and COVID19: How the Global Socioeconomic Shock Challenged Negative Perceptions Toward the Less Fortunate in the Australian Context. Front. Psychol. 11:594837. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.594837

Received: 14 August 2020; Accepted: 22 September 2020; Published: 15 October 2020.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2020 Suomi, Schofield and Butterworth. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Aino Suomi, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Unemployment in the time of COVID-19: A research agenda ☆

David l. blustein.

a Boston College, United States of America

b University of Florida, United States of America

Joaquim A. Ferreira

c University of Coimbra, Portugal

Valerie Cohen-Scali

d Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers, France

Rachel Gali Cinamon

e University of Tel Aviv, Israel

Blake A. Allan

f Purdue University, United States of America

This essay represents the collective vision of a group of scholars in vocational psychology who have sought to develop a research agenda in response to the massive global unemployment crisis that has been evoked by the COVID-19 pandemic. The research agenda includes exploring how this unemployment crisis may differ from previous unemployment periods; examining the nature of the grief evoked by the parallel loss of work and loss of life; recognizing and addressing the privilege of scholars; examining the inequality that underlies the disproportionate impact of the crisis on poor and working class communities; developing a framework for evidence-based interventions for unemployed individuals; and examining the work-family interface and unemployment among youth.

This essay reflects the collective input from members of a community of vocational psychologists who share an interest in psychology of working theory and related social-justice oriented perspectives ( Blustein, 2019 ; Duffy, Blustein, Diemer, & Autin, 2016 ). Each author of this article has contributed a specific set of ideas, which individually and collectively reflect some promising directions for research about the rampant unemployment that sadly defines this COVID-19 crisis.

Our efforts cohere along several assumptions and values. First, we share a view that unemployment has devastating effects on the psychological, economic, and social well-being of individuals and communities ( Blustein, 2019 ). Second, we seek to build on the exemplary research on unemployment that has documented its impact on mental health ( Paul & Moser, 2009 ; Wanberg, 2012 ) and its equally pernicious impact on communities ( International Labor Organization, 2020b ). Third, we hope that this contribution charts a research agenda that will inform practice at individual and systemic levels to support and sustain people as they grapple with the daunting challenge of seeking work and recovering from the psychological and vocational fallout of this pandemic.

The advent of this period of global unemployment is connected causally and temporally to considerable loss of life and illness, which is creating an intense level of grief and trauma for many people. The first step in developing a research agenda for unemployment during the COVID-19 era is to describe the nature of this process of loss in so many critical sectors of life. A major research question, therefore, is to what extent does this unemployment crisis vary from previous bouts of unemployment which were linked to economic fluctuations? In addition, exploring the role of loss and trauma during this crisis should yield research findings that can inform psychological and vocational interventions as well as policy guidance to support people via civic institutions and communities.

1. Recognizing and channeling our own privilege

In Joe Pinker's (2020) Atlantic essay entitled, “ The Pandemic Will Cleave America in Two”, he highlights two distinct experiences of the pandemic. One is an experience felt by those with high levels of education in stable jobs where telework is possible. Lives are now more stressful, work has been turned upside down, childcare is challenging, and leaving the house feels ominous. The other is an experience felt by the rest of the working public – those who cannot work from home and thus are putting themselves at risk every day, whose jobs have been either lost or downsized, and who are wondering not only if they will catch the virus but whether they have the means and resources to survive. As psychologists and professors, the vast majority of “us” (those writing this essay and those reading it) are extremely fortunate to be in the first group. The pandemic has only served to exacerbate the extent of this privilege.

Given our relative position of power, what are ways we can change our research to be more meaningful and impactful to those outside of our bubble? We propose that the recent work on radical healing in communities of color – where the research is often done in collaboration with the participants and building participant agency is an explicit goal - can inform our path forward ( French et al., 2020 ; Mosley et al., 2020 ). Work has always been a domain where individuals experience distress and marginalization. However, in the current pandemic and into the unforeseeable future, this will only exponentially increase. Sure, we can do surveys about people's experiences and provide incentives for their time. And of course qualitative work will allow us to more directly connect with participants and hear their voices. But what is most needed is research where participants receive tangible benefits to improve their work lives. We, as privileged scholars, need to think about how we can use our expertise in studying work to infuse our studies with real world benefits. We see this as occurring on a spectrum in terms of scholars' time and resources available – from information sharing about resources to providing job-seeking or work-related interventions. In our view, now is the time to truly commit to using work-related research not just as a way to build scholarly knowledge, but as a way to improve lives.

2. Inequality and unemployment

Focusing research efforts on real-world benefits means acknowledging how the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed and exacerbated existing inequities in the labor market. Millions of workers in the U.S. have precarious jobs that are uncertain in the continuity and amount of work, do not pay a living wage, do not give workers power to advocate for their needs, or do not provide access to basic benefits ( Kalleberg, 2009 ). Power and privilege are major determinants of who is at risk for precarious work, with historically marginalized communities being disproportionately vulnerable to these job conditions ( International Labor Organization, 2020a ). In turn, people with precarious work experience chronic stress and uncertainty, putting them at risk for mental health, physical, and relational problems ( Blustein, 2019 ). These risk factors may further worsen the effects of the COVID-19 crisis while simultaneously exposing inequities that existed before the crises.

The COVID-19 pandemic is an opportunity for researchers to define and describe how precarious work creates physical, relational, behavioral, psychological, economic, and emotional vulnerabilities that worsen outcomes from crises like the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., unemployment, psychological distress). For example, longitudinal studies can examine how precarious work creates vulnerabilities in different domains, which in turn predict outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic, including unemployment and mental health. This may include larger scale cohort studies that examine how the COVID-19 crisis has created a generation of precarity among people undergoing the school-to-work transition. Researchers can also study how governmental and nonprofit interventions reduce vulnerability and buffer the relations between precarious work and various outcomes. For example, direct cash assistance is becoming increasingly popular as an efficient way to help people in poverty ( Evans & Popova, 2014 ). However, dominant social narratives (e.g., the myth of meritocracy, the American dream) blame people with poor quality work for their situations. Psychologists have a critical role in (a) documenting false social narratives, (b) studying interventions to provide accurate counter narratives (e.g., people who receive direct cash assistance do not spend money on alcohol or drugs; most people who need assistance are working; Evans & Popova, 2014 ), and (c) studying how to effectively change attitudes among the public to create support for effective interventions.

3. Work-family interface

Investigating the work-family interface during unemployment may appear contradictory. It can be argued that because there is no paid work, the work-family interface does not exist. But ‘work’ is an integral part of people's lives, even during unemployment; for example, working to find a job is a daunting task that is usually done from home. Thus, the work-family interface also exists during unemployment, but our knowledge about this is limited. Our current knowledge on the work-family interface primarily focuses on people who work full-time and usually among working parents with young children ( Cinamon, 2018 ). As such, focusing on the work-family interface during periods of unemployment represents a needed research agenda that can inform public policy and scholarship in work-family relationships.

The rise in unemployment due to COVID-19 relates not only to the unemployed, but also to other family members. Important research questions to consider are how are positive and negative feelings and thoughts about the absence of work conveyed and co-constructed by family members? What family behaviors and dynamics promote and serve as social capital for the unemployed and for the other members of the family? Do job search behaviors serve as a form of modeling for other family members? What are the experiences of unemployed spouses and children, and how do these experiences shape their own career development? These issues can be discerned among unemployed people of different ages, communities, and cultures.

Several research methods can promote this agenda. Participatory action research can enable vocational researchers to be proactive and involved in increasing social solidarity. This approach requires mutual collaboration between the researcher and families wherein one of the parents is unemployed. By giving them voice to describe their experiences, thoughts, ideas, and suggested solutions, we affirm inclusion of the individuals living through the new reality, thereby conveying respect and acknowledgment. At the same time, we can bring ideas, knowledge, and social connections to the families that can serve as social capital. In addition, longitudinal quantitative studies among unemployed families that explore some of the issues noted above would be important as a means of exploring how the new unemployment experience is shaping both work and relationships. We also advocate that meaningful incentives be offered to participants in all of these studies, such as online job search workshops and career education interventions for adolescents.

4. Strategies for dealing with unemployment in the pandemic of 2020

Forward-looking governments and organizations (such as universities) should begin thinking about how to deal with the immediate and long-term consequences of the economic crisis created by COVID-19, especially in the area of unemployment. Creating meaningful interventions to assist the newly unemployed will be difficult because of the unprecedented number of individuals and families that are affected and because of the diverse contextual and personal factors that characterize this new population. Because of this diversity of contextual and personal factors, different interventions will be required for different patterns of individual/contextual characteristics ( Ferreira et al., 2015 ).

In broad outline, a research program to address the diversity of issues identified above could be envisioned to consist of several distinct phases: First, it would be necessary to carefully assess the external circumstances of the unemployed individual's job loss, including the probability of re-employment, financial condition, family composition, and living conditions, among others. Second, an assessment should be made of the individual's strengths and growth edges, particularly as they impact the current situation. These assessments could be performed via paper or online questionnaire. Based on these initial assessments, the third phase would involve using statistical analyses such as cluster analysis to form distinct groups of unemployed individuals, perhaps based in part on the probability of re-employment following the pandemic. The fourth phase would focus on determining the types (and/or combinations) of intervention most appropriate for each group (e.g., temporary government assistance; emotional support counseling; retraining for better future job prospects; relocation, etc.). Because access to specific types of assistance is frequently a serious challenge, especially for underprivileged individuals, the fifth phase should emphasize facilitating individuals' access to the specific assistance they need. Finally, the sixth phase of research should evaluate the efficacy of this approach, although designing such a large research program in a crisis situation requires ongoing process evaluation throughout the design and implementation stages of the research program.

5. Unemployment among youth

As reflected in a recent International Labor Organization (2020a) report on the impact of the COVID-19 crisis, youth were already vulnerable within the workforce prior to the crisis; the recent advent of massive job losses and growing precarity of work is having particularly painful impacts on young people across the globe. The COVID-19 economic crisis with vast increases in unemployment (and competition between workers) and the probable growth of digitalization may result in a major dislocation of young workers from the labor market for some time ( International Labor Organization, 2020b ). To provide knowledge to meet this daunting challenge, researchers should develop an agenda focusing on two major components—the first is a participatory mode of understanding the experience of youth and the second is the development of evidence-based interventions that are derived from this research process.

The data gathering aspect of this research agenda optimally should focus on understanding unemployed youths' perception of their situation (opportunities, barriers, fears, and intentions) and of the new labor market. We propose that research is needed to unpack how youth are constructing this new reality, their relationship to society, to others, and to the world. This crisis may have changed their priorities, the meaning of work, and their lifestyle. For example, this crisis may have led to an awareness of the necessity of developing more environmentally responsible behaviors ( Cohen-Scali et al., 2018 ). These new life styles could result in skills development and increased autonomy and adaptability among young people. In addition, the focus on understanding youths' experience, which can encompass qualitative and quantitative methods, should also include explorations of shifts in youths' sense of identity and purpose, which may be dramatically affected by the crisis. The young people who are without work should be involved at each step of the research process in order to improve their capacities, knowledge, and agency and to ensure that the research is designed from their lived experiences.

Building on these research efforts, interventions may be designed that include individual counseling strategies as well as systemic interventions based on analyses of the communities in which young people are involved (for example, families and couples and not only individuals). In addition, we need more research to learn about the process of collective empowerment and critical consciousness development, which can inform youths' advocacy efforts and serve as a buffer in their career development ( Blustein, 2019 ).

6. Conclusion

The research ideas presented in this contribution have been offered as a means of stimulating needed scholarship, program development, and advocacy efforts. Naturally, these ideas are not intended to be exhaustive. We hope that readers will find ideas and perspectives in our essay that may stimulate a broad-based research agenda for our field, optimally informing transformative interventions and needed policy interventions for individuals and communities suffering from the loss of work (and loss of loved ones in this pandemic). A common thread in our essay is the recommendation that research efforts be constructed from the lived experiences of the individuals who are now out of work. As we have noted here, their experiences may not be similar to other periods of extensive unemployment, which argues strongly for experience-near, participatory research. We are also advocating for the use of rigorous quantitative methods to develop new understanding of the nature of unemployment during this period and to develop and assess interventions. In addition, we would like to advocate that the collective scholarly efforts of our community include incentives and outcomes that support unemployed individuals. For example, online workshops and resources can be shared with participants and other communities as a way of not just dignifying their participation, but of also providing tangible support during a crisis.

In closing, we are humbled by the stories that we hear from our communities about the job loss of this pandemic period. Our authorship team shares a deep commitment to research that matters; in this context, we believe that our work now matters more than we can imagine.

☆ The order of authorship for authors two through six was determined randomly; each of these authors contributed equally to this paper.

- Blustein D.L. Oxford University Press; NY: 2019. The importance of work in an age of uncertainty: The eroding work experience in America. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cinamon R.G. Paper presented at the Society of Vocational Psychology; Arizona: 2018, June. Life span and time perspective of the work-family interface – Critical transitions and suggested interventions. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cohen-Scali V., Pouyaud J., Podgorny M., Drabik-Podgorna V., Aisenson G., Bernaud J.L., Moumoula I.A., Guichard J., editors. Interventions in career design and education. Springer; Cham, Switzerland: 2018. [ Google Scholar ]

- Duffy R.D., Blustein D.L., Diemer M.A., Autin K.L. The psychology of working theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2016; 63 (2):127–148. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Evans D.K., Popova A. Cash transfers and temptation goods: A review of global evidence. The World Bank. 2014 doi: 10.1596/1813-9450-6886. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ferreira J.A., Reitzle M., Lee B., Freitas R.A., Santos E.R., Alcoforado L., Vondracek F.W. Configurations of unemployment, reemployment, and psychological well-being: A longitudinal study of unemployed individuals in Portugal. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2015; 91 :54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2015.09.004. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- French B.H., Lewis J.A., Mosley D.V., Adames H.Y., Chavez-Dueñas N.Y., Chen G.A., Neville H.A. Toward a psychological framework of radical healing in communities of color. The Counseling Psychologist. 2020; 48 :14–46. doi: 10.1177/0011000019843506. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- International Labor Organization World Employment and Social Outlook – Trends. 2020:2020. https://www.ilo.org/global/research/global-reports/weso/2020/lang--en/index.htm [ Google Scholar ]

- International Labor Organization. (2020b). Young workers will be hit hard by COVID-19's economic fallout. https://iloblog.org/2020/04/15/young-workers-will-be-hit-hard-by-covid-19s-economic-fallout/ .

- Kalleberg A.L. Precarious work, insecure workers: Employment relations in transition. American Sociological Review. 2009; 74 (1):1–22. doi: 10.1177/000312240907400101. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mosley D.V., Hargons C.N., Meiller C., Angyal B., Wheeler P., Davis C., Stevens-Watkins D. Critical consciousness of anti-Black racism: A practical model to prevent and resist racial trauma. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2020 doi: 10.1037/cou0000430. (Advance online publication) [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Paul K.I., Moser K. Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2009; 74 :264–282. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pinker J. The Atlantic; 2020. The pandemic will cleave America in two. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wanberg C.R. The individual experience of unemployment. Annual Review of Psychology. 2012; 63 :369–396. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Unemployment, Social Vulnerability, and Health in Europe pp 167–183 Cite as

The Effects of Youth Unemployment: A Review of the Literature

- V. L. Damstrup

317 Accesses

1 Citations

Part of the book series: Health Systems Research ((HEALTH))

Young adults and teenagers are engaged in work on a much smaller scale than older workers. Young people are engaged less in work because they are still in school, or they are involved in leisure activities. Some, on the other hand, would like to work, but find it difficult obtaining employment. The transition from school to employment is a process that involves searching and changing jobs before deciding on a more or less permanent employment. Today, more than ever, youths have a lower rate of employment, hence there has been much concern about the youth labor market.

- Young People

- Labor Force

- Vocational Training

- Young Person

- School Dropout

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Adams AV, Mangum GL (1978) The lingering crises of youth unemployment. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, Michigan

Google Scholar

Auletta K (1982) The underclass. Random House, New York

Banks E (1980) The use of the General Health Questionnaire as an indicator of mental health in occupational studies. J Occup Psychol 53: 187–194

Article Google Scholar

Berryman S (1978) Youth unemployment and career education. Publ Pol 26: 29–69

Blau FD (1979) Youth and jobs: participation and unemployment rates. Youth Soc 111: 32–52

Bonus ME (1982) Preliminary descriptive analysis of employed and unemployed youth. Center for Human Research, Ohio

Bowers N (1979) Youth and marginal: an overview of youth unemployment. Monthly Labour Review, October: 4–6

Braginsky DD, Braginsky BA (1975) Surplus people: their lost faith in self and system. Psychol Today 3: 8–72

Braverman M (1981) Youth unemployment and the work with young adults. J Library Hist 6: 355–364

Brenner H (1979) Estimating the social cost of national economic policy: implications for mental and physical health and criminal aggression. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC

Brenner SO (1984) Process homogeneity and the process of becoming socially vulnerable. Paper presented at the 3rd international conference on system science in health care, Munich, 16–20 July

Brockington D, White R (1983) United Kingdom: non-formal education in a context of youth unemployment. Prospects 13: 73–81

Bschor R (1984) Recent trends in fatalities among young Berliners: suicides, drug addicts, traffic accidents. Paper presented at the 3rd international conference on system science in health care, Munich, 16–20 July

CEDEFOP (1980) Youth unemployment and vocational training: transition from school to work. Summary of results of a CEDEFOP conference, Berlin, 11–12 November European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training

Casson M (1979) Youth unemployment. Holmes and Meir, New York

Cohn R (1978) The effect of employment status change on self attitude. Soc Psychol 41: 81–93

Coleman JC (1973) Life stress and maladaptive behaviour. Am J Occup Ther 27: 169–180

Coles R (1971) On the meaning of work. Atlantic Monthly 228: 103–104

Cooke G (1982) Special needs beyond sixteen. Spec Educ Forward Trends 9: 39–41

PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Corvalan-Vasquez O (1983) Vocational training of disadvantaged youth in developing countries. Int Labour Ref 122: 367–379

Daniel WW, Stilque E (1977) Is youth unemployment really a problem? New Soc 10: 287–289

Donovan A, Oddy M (1982) Psychological aspects of unemployment: an investigation into the emotional and social adjustment of school leavers. J Adolesc 5: 15–30

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Dussuyer I (1984) Becoming socially invulnerable: the use of social support and social networks. Paper presented at the 3rd international conference on system service in health care, Munich, 16–20 July

Earls F (1978) The social reconstruction of adolescence: toward an explanation for increasing rates of violence in youth. Perspect Biol Med 22: 65–82

Eisner V (1966) Health of enrollees in neighborhood youth corps. Pediatrics 38: 40–43

English J (1970) Not as a patient: psychological development in a job training program. Am J Orthopsychiatry 40: 142–150

PubMed Google Scholar

Feather NT, Barber JG (1983) Depressive reaction and unemployment. J Appl Psychol 92: 185–195

CAS Google Scholar

Finlay-Jones R, Eckhardt B (1981) Psychiatric disorder among the young unemployed. Aust NZ Psychiatry 15: 265–270

Article CAS Google Scholar

Fyfe J (1978) Youth unemployment: an international perspective. Int J Soc Econ 5: 51–62

Ginzberg E (1980) Youth unemployment. Sci Am 242: 531–37

Gordon M (1979) Youth education and unemployment problems: an international perspective. Carnegie Council on Policy Studies in Higher Education, New York

Gurney M (1980) Effects of unemployment on the psycho-social development of school leavers. Occup Psychol 53: 205–213

Guttentag M (1966a) The parallel institutions of the Poverty act evaluating their effect on the unemployed youth and existing institutions of America. Am J Orthopsychiatry 30: 643–651

Guttentag M (1966b) The relationship of unemployment to crime and delinquency. J Soc Issues 26: 105–114

Harris RD (1980) Unemployment and its effects on the teenager. Aust Fam Physician 9: 546–553

Husain H (1981) Employment in my practice. Br Med J 283: 26–27