- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Introduce Evidence: 41 Effective Phrases & Examples

Research requires us to scrutinize information and assess its credibility. Accordingly, when we think about various phenomena, we examine empirical data and craft detailed explanations justifying our interpretations. An essential component of constructing our research narratives is thus providing supporting evidence and examples.

The type of proof we provide can either bolster our claims or leave readers confused or skeptical of our analysis. Therefore, it’s crucial that we use appropriate, logical phrases that guide readers clearly from one idea to the next. In this article, we explain how evidence and examples should be introduced according to different contexts in academic writing and catalog effective language you can use to support your arguments, examples included.

When to Introduce Evidence and Examples in a Paper

Evidence and examples create the foundation upon which your claims can stand firm. Without proof, your arguments lack credibility and teeth. However, laundry listing evidence is as bad as failing to provide any materials or information that can substantiate your conclusions. Therefore, when you introduce examples, make sure to judiciously provide evidence when needed and use phrases that will appropriately and clearly explain how the proof supports your argument.

There are different types of claims and different types of evidence in writing. You should introduce and link your arguments to evidence when you

- state information that is not “common knowledge”;

- draw conclusions, make inferences, or suggest implications based on specific data;

- need to clarify a prior statement, and it would be more effectively done with an illustration;

- need to identify representative examples of a category;

- desire to distinguish concepts; and

- emphasize a point by highlighting a specific situation.

Introductory Phrases to Use and Their Contexts

To assist you with effectively supporting your statements, we have organized the introductory phrases below according to their function. This list is not exhaustive but will provide you with ideas of the types of phrases you can use.

Although any research author can make use of these helpful phrases and bolster their academic writing by entering them into their work, before submitting to a journal, it is a good idea to let a professional English editing service take a look to ensure that all terms and phrases make sense in the given research context. Wordvice offers paper editing , thesis editing , and dissertation editing services that help elevate your academic language and make your writing more compelling to journal authors and researchers alike.

For more examples of strong verbs for research writing , effective transition words for academic papers , or commonly confused words , head over to the Wordvice Academic Resources website.

What this handout is about

This handout will provide a broad overview of gathering and using evidence. It will help you decide what counts as evidence, put evidence to work in your writing, and determine whether you have enough evidence. It will also offer links to additional resources.

Introduction

Many papers that you write in college will require you to make an argument ; this means that you must take a position on the subject you are discussing and support that position with evidence. It’s important that you use the right kind of evidence, that you use it effectively, and that you have an appropriate amount of it. If, for example, your philosophy professor didn’t like it that you used a survey of public opinion as your primary evidence in your ethics paper, you need to find out more about what philosophers count as good evidence. If your instructor has told you that you need more analysis, suggested that you’re “just listing” points or giving a “laundry list,” or asked you how certain points are related to your argument, it may mean that you can do more to fully incorporate your evidence into your argument. Comments like “for example?,” “proof?,” “go deeper,” or “expand” in the margins of your graded paper suggest that you may need more evidence. Let’s take a look at each of these issues—understanding what counts as evidence, using evidence in your argument, and deciding whether you need more evidence.

What counts as evidence?

Before you begin gathering information for possible use as evidence in your argument, you need to be sure that you understand the purpose of your assignment. If you are working on a project for a class, look carefully at the assignment prompt. It may give you clues about what sorts of evidence you will need. Does the instructor mention any particular books you should use in writing your paper or the names of any authors who have written about your topic? How long should your paper be (longer works may require more, or more varied, evidence)? What themes or topics come up in the text of the prompt? Our handout on understanding writing assignments can help you interpret your assignment. It’s also a good idea to think over what has been said about the assignment in class and to talk with your instructor if you need clarification or guidance.

What matters to instructors?

Instructors in different academic fields expect different kinds of arguments and evidence—your chemistry paper might include graphs, charts, statistics, and other quantitative data as evidence, whereas your English paper might include passages from a novel, examples of recurring symbols, or discussions of characterization in the novel. Consider what kinds of sources and evidence you have seen in course readings and lectures. You may wish to see whether the Writing Center has a handout regarding the specific academic field you’re working in—for example, literature , sociology , or history .

What are primary and secondary sources?

A note on terminology: many researchers distinguish between primary and secondary sources of evidence (in this case, “primary” means “first” or “original,” not “most important”). Primary sources include original documents, photographs, interviews, and so forth. Secondary sources present information that has already been processed or interpreted by someone else. For example, if you are writing a paper about the movie “The Matrix,” the movie itself, an interview with the director, and production photos could serve as primary sources of evidence. A movie review from a magazine or a collection of essays about the film would be secondary sources. Depending on the context, the same item could be either a primary or a secondary source: if I am writing about people’s relationships with animals, a collection of stories about animals might be a secondary source; if I am writing about how editors gather diverse stories into collections, the same book might now function as a primary source.

Where can I find evidence?

Here are some examples of sources of information and tips about how to use them in gathering evidence. Ask your instructor if you aren’t sure whether a certain source would be appropriate for your paper.

Print and electronic sources

Books, journals, websites, newspapers, magazines, and documentary films are some of the most common sources of evidence for academic writing. Our handout on evaluating print sources will help you choose your print sources wisely, and the library has a tutorial on evaluating both print sources and websites. A librarian can help you find sources that are appropriate for the type of assignment you are completing. Just visit the reference desk at Davis or the Undergraduate Library or chat with a librarian online (the library’s IM screen name is undergradref).

Observation

Sometimes you can directly observe the thing you are interested in, by watching, listening to, touching, tasting, or smelling it. For example, if you were asked to write about Mozart’s music, you could listen to it; if your topic was how businesses attract traffic, you might go and look at window displays at the mall.

An interview is a good way to collect information that you can’t find through any other type of research. An interview can provide an expert’s opinion, biographical or first-hand experiences, and suggestions for further research.

Surveys allow you to find out some of what a group of people thinks about a topic. Designing an effective survey and interpreting the data you get can be challenging, so it’s a good idea to check with your instructor before creating or administering a survey.

Experiments

Experimental data serve as the primary form of scientific evidence. For scientific experiments, you should follow the specific guidelines of the discipline you are studying. For writing in other fields, more informal experiments might be acceptable as evidence. For example, if you want to prove that food choices in a cafeteria are affected by gender norms, you might ask classmates to undermine those norms on purpose and observe how others react. What would happen if a football player were eating dinner with his teammates and he brought a small salad and diet drink to the table, all the while murmuring about his waistline and wondering how many fat grams the salad dressing contained?

Personal experience

Using your own experiences can be a powerful way to appeal to your readers. You should, however, use personal experience only when it is appropriate to your topic, your writing goals, and your audience. Personal experience should not be your only form of evidence in most papers, and some disciplines frown on using personal experience at all. For example, a story about the microscope you received as a Christmas gift when you were nine years old is probably not applicable to your biology lab report.

Using evidence in an argument

Does evidence speak for itself.

Absolutely not. After you introduce evidence into your writing, you must say why and how this evidence supports your argument. In other words, you have to explain the significance of the evidence and its function in your paper. What turns a fact or piece of information into evidence is the connection it has with a larger claim or argument: evidence is always evidence for or against something, and you have to make that link clear.

As writers, we sometimes assume that our readers already know what we are talking about; we may be wary of elaborating too much because we think the point is obvious. But readers can’t read our minds: although they may be familiar with many of the ideas we are discussing, they don’t know what we are trying to do with those ideas unless we indicate it through explanations, organization, transitions, and so forth. Try to spell out the connections that you were making in your mind when you chose your evidence, decided where to place it in your paper, and drew conclusions based on it. Remember, you can always cut prose from your paper later if you decide that you are stating the obvious.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself about a particular bit of evidence:

- OK, I’ve just stated this point, but so what? Why is it interesting? Why should anyone care?

- What does this information imply?

- What are the consequences of thinking this way or looking at a problem this way?

- I’ve just described what something is like or how I see it, but why is it like that?

- I’ve just said that something happens—so how does it happen? How does it come to be the way it is?

- Why is this information important? Why does it matter?

- How is this idea related to my thesis? What connections exist between them? Does it support my thesis? If so, how does it do that?

- Can I give an example to illustrate this point?

Answering these questions may help you explain how your evidence is related to your overall argument.

How can I incorporate evidence into my paper?

There are many ways to present your evidence. Often, your evidence will be included as text in the body of your paper, as a quotation, paraphrase, or summary. Sometimes you might include graphs, charts, or tables; excerpts from an interview; or photographs or illustrations with accompanying captions.

When you quote, you are reproducing another writer’s words exactly as they appear on the page. Here are some tips to help you decide when to use quotations:

- Quote if you can’t say it any better and the author’s words are particularly brilliant, witty, edgy, distinctive, a good illustration of a point you’re making, or otherwise interesting.

- Quote if you are using a particularly authoritative source and you need the author’s expertise to back up your point.

- Quote if you are analyzing diction, tone, or a writer’s use of a specific word or phrase.

- Quote if you are taking a position that relies on the reader’s understanding exactly what another writer says about the topic.

Be sure to introduce each quotation you use, and always cite your sources. See our handout on quotations for more details on when to quote and how to format quotations.

Like all pieces of evidence, a quotation can’t speak for itself. If you end a paragraph with a quotation, that may be a sign that you have neglected to discuss the importance of the quotation in terms of your argument. It’s important to avoid “plop quotations,” that is, quotations that are just dropped into your paper without any introduction, discussion, or follow-up.

Paraphrasing

When you paraphrase, you take a specific section of a text and put it into your own words. Putting it into your own words doesn’t mean just changing or rearranging a few of the author’s words: to paraphrase well and avoid plagiarism, try setting your source aside and restating the sentence or paragraph you have just read, as though you were describing it to another person. Paraphrasing is different than summary because a paraphrase focuses on a particular, fairly short bit of text (like a phrase, sentence, or paragraph). You’ll need to indicate when you are paraphrasing someone else’s text by citing your source correctly, just as you would with a quotation.

When might you want to paraphrase?

- Paraphrase when you want to introduce a writer’s position, but their original words aren’t special enough to quote.

- Paraphrase when you are supporting a particular point and need to draw on a certain place in a text that supports your point—for example, when one paragraph in a source is especially relevant.

- Paraphrase when you want to present a writer’s view on a topic that differs from your position or that of another writer; you can then refute writer’s specific points in your own words after you paraphrase.

- Paraphrase when you want to comment on a particular example that another writer uses.

- Paraphrase when you need to present information that’s unlikely to be questioned.

When you summarize, you are offering an overview of an entire text, or at least a lengthy section of a text. Summary is useful when you are providing background information, grounding your own argument, or mentioning a source as a counter-argument. A summary is less nuanced than paraphrased material. It can be the most effective way to incorporate a large number of sources when you don’t have a lot of space. When you are summarizing someone else’s argument or ideas, be sure this is clear to the reader and cite your source appropriately.

Statistics, data, charts, graphs, photographs, illustrations

Sometimes the best evidence for your argument is a hard fact or visual representation of a fact. This type of evidence can be a solid backbone for your argument, but you still need to create context for your reader and draw the connections you want them to make. Remember that statistics, data, charts, graph, photographs, and illustrations are all open to interpretation. Guide the reader through the interpretation process. Again, always, cite the origin of your evidence if you didn’t produce the material you are using yourself.

Do I need more evidence?

Let’s say that you’ve identified some appropriate sources, found some evidence, explained to the reader how it fits into your overall argument, incorporated it into your draft effectively, and cited your sources. How do you tell whether you’ve got enough evidence and whether it’s working well in the service of a strong argument or analysis? Here are some techniques you can use to review your draft and assess your use of evidence.

Make a reverse outline

A reverse outline is a great technique for helping you see how each paragraph contributes to proving your thesis. When you make a reverse outline, you record the main ideas in each paragraph in a shorter (outline-like) form so that you can see at a glance what is in your paper. The reverse outline is helpful in at least three ways. First, it lets you see where you have dealt with too many topics in one paragraph (in general, you should have one main idea per paragraph). Second, the reverse outline can help you see where you need more evidence to prove your point or more analysis of that evidence. Third, the reverse outline can help you write your topic sentences: once you have decided what you want each paragraph to be about, you can write topic sentences that explain the topics of the paragraphs and state the relationship of each topic to the overall thesis of the paper.

For tips on making a reverse outline, see our handout on organization .

Color code your paper

You will need three highlighters or colored pencils for this exercise. Use one color to highlight general assertions. These will typically be the topic sentences in your paper. Next, use another color to highlight the specific evidence you provide for each assertion (including quotations, paraphrased or summarized material, statistics, examples, and your own ideas). Lastly, use another color to highlight analysis of your evidence. Which assertions are key to your overall argument? Which ones are especially contestable? How much evidence do you have for each assertion? How much analysis? In general, you should have at least as much analysis as you do evidence, or your paper runs the risk of being more summary than argument. The more controversial an assertion is, the more evidence you may need to provide in order to persuade your reader.

Play devil’s advocate, act like a child, or doubt everything

This technique may be easiest to use with a partner. Ask your friend to take on one of the roles above, then read your paper aloud to them. After each section, pause and let your friend interrogate you. If your friend is playing devil’s advocate, they will always take the opposing viewpoint and force you to keep defending yourself. If your friend is acting like a child, they will question every sentence, even seemingly self-explanatory ones. If your friend is a doubter, they won’t believe anything you say. Justifying your position verbally or explaining yourself will force you to strengthen the evidence in your paper. If you already have enough evidence but haven’t connected it clearly enough to your main argument, explaining to your friend how the evidence is relevant or what it proves may help you to do so.

Common questions and additional resources

- I have a general topic in mind; how can I develop it so I’ll know what evidence I need? And how can I get ideas for more evidence? See our handout on brainstorming .

- Who can help me find evidence on my topic? Check out UNC Libraries .

- I’m writing for a specific purpose; how can I tell what kind of evidence my audience wants? See our handouts on audience , writing for specific disciplines , and particular writing assignments .

- How should I read materials to gather evidence? See our handout on reading to write .

- How can I make a good argument? Check out our handouts on argument and thesis statements .

- How do I tell if my paragraphs and my paper are well-organized? Review our handouts on paragraph development , transitions , and reorganizing drafts .

- How do I quote my sources and incorporate those quotes into my text? Our handouts on quotations and avoiding plagiarism offer useful tips.

- How do I cite my evidence? See the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

- I think that I’m giving evidence, but my instructor says I’m using too much summary. How can I tell? Check out our handout on using summary wisely.

- I want to use personal experience as evidence, but can I say “I”? We have a handout on when to use “I.”

Works consulted

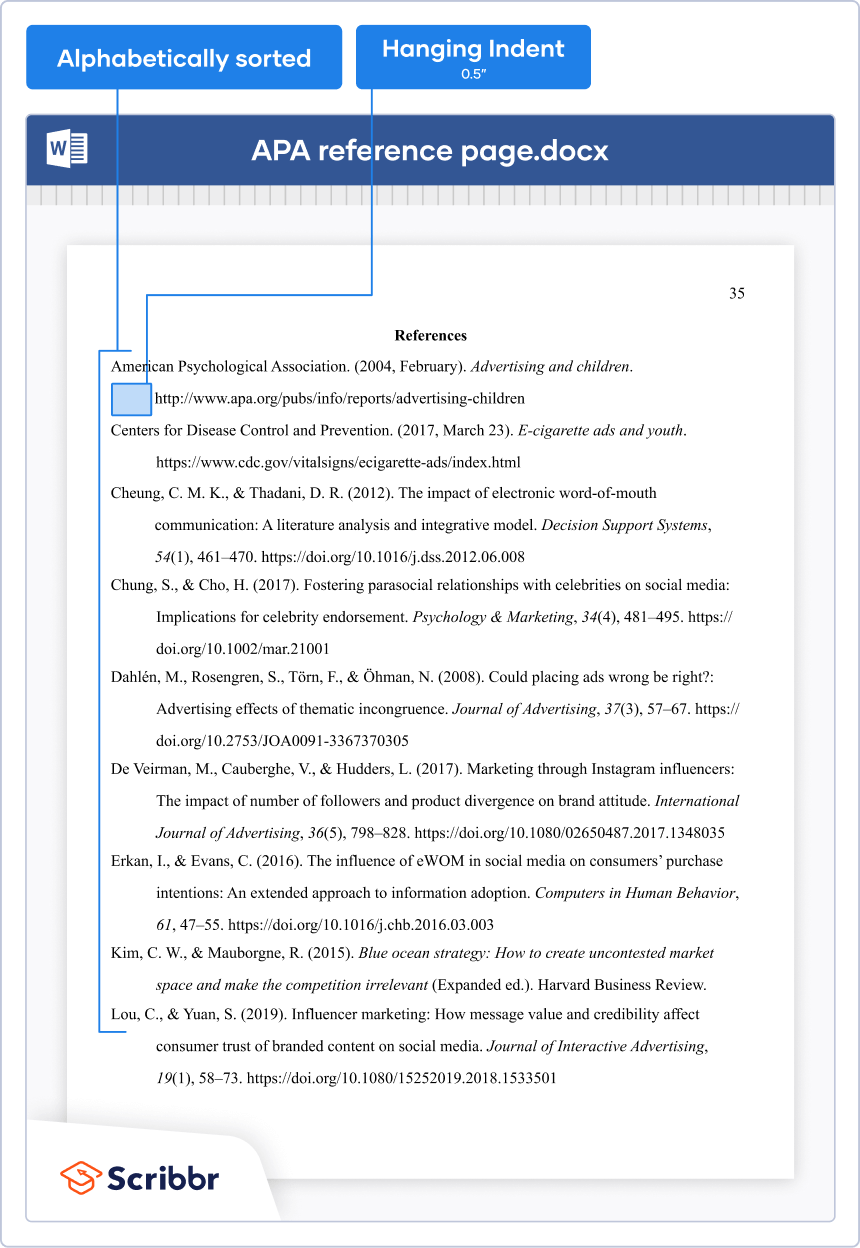

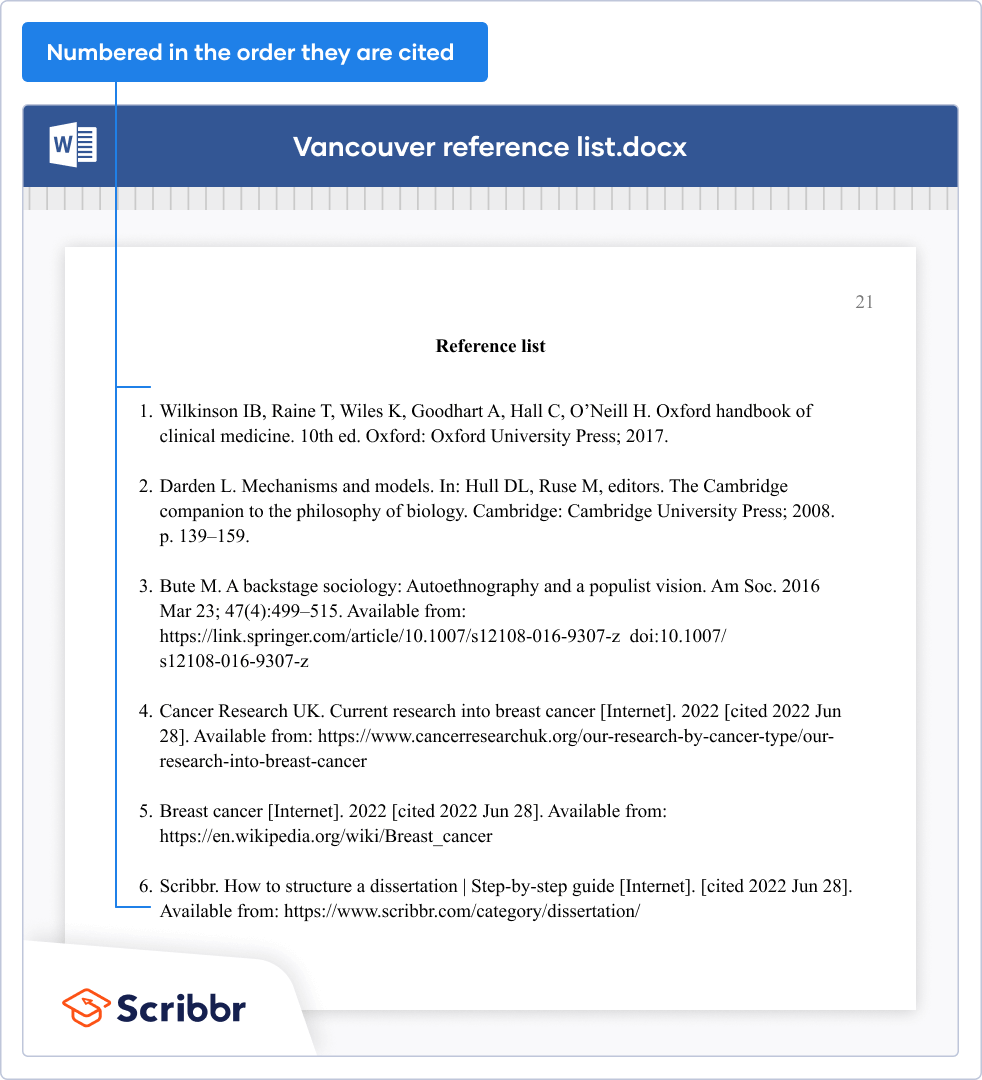

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Lunsford, Andrea A., and John J. Ruszkiewicz. 2016. Everything’s an Argument , 7th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Miller, Richard E., and Kurt Spellmeyer. 2016. The New Humanities Reader , 5th ed. Boston: Cengage.

University of Maryland. 2019. “Research Using Primary Sources.” Research Guides. Last updated October 28, 2019. https://lib.guides.umd.edu/researchusingprimarysources .

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Finance and Business

- Legal Matters

- Contracts and Legal Agreements

How to Introduce Evidence in an Essay

Last Updated: December 5, 2023

This article was co-authored by Tristen Bonacci . Tristen Bonacci is a Licensed English Teacher with more than 20 years of experience. Tristen has taught in both the United States and overseas. She specializes in teaching in a secondary education environment and sharing wisdom with others, no matter the environment. Tristen holds a BA in English Literature from The University of Colorado and an MEd from The University of Phoenix. This article has been viewed 236,644 times.

When well integrated into your argument, evidence helps prove that you've done your research and thought critically about your topic. But what's the best way to introduce evidence so it feels seamless and has the highest impact? There are actually quite a few effective strategies you can use, and we've rounded up the best ones for you here. Try some of the tips below to introduce evidence in your essay and make a persuasive argument.

Setting up the Evidence

- You can use 1-2 sentences to set up the evidence, if needed, but usually more concise you are, the better.

- For example, you may make an argument like, “Desire is a complicated, confusing emotion that causes pain to others.”

- Or you may make an assertion like, “The treatment of addiction must consider root cause issues like mental health and poor living conditions.”

- For example, you may write, “The novel explores the theme of adolescent love and desire.”

- Or you may write, “Many studies show that addiction is a mental health issue.”

Putting in the Evidence

- For example, you may use an introductory clause like, “According to Anne Carson…”, "In the following chart...," “The author states…," "The survey shows...." or “The study argues…”

- Place a comma after the introductory clause if you are using a quote. For example, “According to Anne Carson, ‘Desire is no light thing" or "The study notes, 'levels of addiction rise as levels of poverty and homelessness also rise.'"

- A list of introductory clauses can be found here: https://student.unsw.edu.au/introducing-quotations-and-paraphrases .

- For example, you may write, “In the novel, Carson is never shy about how her characters express desire for each other: ‘When they made love/ Geryon liked to touch in slow succession each of the bones of Herakles' back…’”

- Or you may write, "The study charts the rise in addiction levels, concluding: 'There is a higher level of addiction in specific areas of the United States.'"

- For example, you may write, “Carson views events as inevitable, as man moving through time like “a harpoon,” much like the fates of her characters.”

- Or you may write, "The chart indicates the rising levels of addiction in young people, an "epidemic" that shows no sign of slowing down."

- For example, you may write in the first mention, “In Anne Carson’s The Autobiography of Red , the color red signifies desire, love, and monstrosity.” Or you may write, "In the study Addiction Rates conducted by the Harvard Review...".

- After the first mention, you can write, “Carson states…” or “The study explores…”.

- If you are citing the author’s name in-text as part of your citation style, you do not need to note their name in the text. You can just use the quote and then place the citation at the end.

- If you are paraphrasing a source, you may still use quotation marks around any text you are lifting directly from the source.

- For example, you may write, “In the novel, the characters express desire for each other: ‘When they made love/ Geryon liked to touch in slow succession each of the bones of Herakles' back (Carson, 48).”

- Or you may write, "Based on the data in the graph below, the study shows the 'intersection between opioid addiction and income' (Branson, 10)."

- If you are using footnotes or endnotes, make sure you use the appropriate citation for each piece of evidence you place in your essay.

- You may also mention the title of the work or source you are paraphrasing or summarizing and the author's name in the paraphrase or summary.

- For example, you may write a paraphrase like, "As noted in various studies, the correlation between addiction and mental illness is often ignored by medical health professionals (Deder, 10)."

- Or you may write a summary like, " The Autobiography of Red is an exploration of desire and love between strange beings, what critics have called a hybrid work that combines ancient meter with modern language (Zambreno, 15)."

- The only time you should place 2 pieces of evidence together is when you want to directly compare 2 short quotes (each less than 1 line long).

- Your analysis should then include a complete compare and contrast of the 2 quotes to show you have thought critically about them both.

Analyzing the Evidence

- For example, you may write, “In the novel, Carson is never shy about how her characters express desire for each other: ‘When they made love/ Geryon liked to touch in slow succession each of the bones of Herakles' back (Carson, 48). The connection between Geryon and Herakles is intimate and gentle, a love that connects the two characters in a physical and emotional way.”

- Or you may write, "In the study Addiction Rates conducted by the Harvard Review, the data shows a 50% rise in addiction levels in specific areas across the United States. The study illustrates a clear connection between addiction levels and communities where income falls below the poverty line and there is a housing shortage or crisis."

- For example, you may write, “Carson’s treatment of the relationship between Geryon and Herakles can be linked back to her approach to desire as a whole in the novel, which acts as both a catalyst and an impediment for her characters.”

- Or you may write, "The survey conducted by Dr. Paula Bronson, accompanied by a detailed academic dissertation, supports the argument that addiction is not a stand alone issue that can be addressed in isolation."

- For example, you may write, “The value of love between two people is not romanticized, but it is still considered essential, similar to the feeling of belonging, another key theme in the novel.”

- Or you may write, "There is clearly a need to reassess the current thinking around addiction and mental illness so the health and sciences community can better study these pressing issues."

Expert Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ Tristen Bonacci. Licensed English Teacher. Expert Interview. 21 December 2021.

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/assignments/quoliterature/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/evidence/

- ↑ https://wts.indiana.edu/writing-guides/using-evidence.html

About This Article

Before you introduce evidence into your essay, begin the paragraph with a topic sentence. This sentence should give the reader an overview of the point you’ll be arguing or making with the evidence. When you get to citing the evidence, begin the sentence with a clause like, “The study finds” or “According to Anne Carson.” You can also include a short quotation in the middle of a sentence without introducing it with a clause. Remember to introduce the author’s first and last name when you use the evidence for the first time. Afterwards, you can just mention their last name. Once you’ve presented the evidence, take time to explain in your own words how it backs up the point you’re making. For tips on how to reference your evidence correctly, keep reading! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Apr 15, 2022

Did this article help you?

Mar 2, 2019

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

- Human Editing

- Free AI Essay Writer

- AI Outline Generator

- AI Paragraph Generator

- Paragraph Expander

- Essay Expander

- Literature Review Generator

- Research Paper Generator

- Thesis Generator

- Paraphrasing tool

- AI Rewording Tool

- AI Sentence Rewriter

- AI Rephraser

- AI Paragraph Rewriter

- Summarizing Tool

- AI Content Shortener

- Plagiarism Checker

- AI Detector

- AI Essay Checker

- Citation Generator

- Reference Finder

- Book Citation Generator

- Legal Citation Generator

- Journal Citation Generator

- Reference Citation Generator

- Scientific Citation Generator

- Source Citation Generator

- Website Citation Generator

- URL Citation Generator

- Proofreading Service

- Editing Service

- AI Writing Guides

- AI Detection Guides

- Citation Guides

- Grammar Guides

- Paraphrasing Guides

- Plagiarism Guides

- Summary Writing Guides

- STEM Guides

- Humanities Guides

- Language Learning Guides

- Coding Guides

- Top Lists and Recommendations

- AI Detectors

- AI Writing Services

- Coding Homework Help

- Citation Generators

- Editing Websites

- Essay Writing Websites

- Language Learning Websites

- Math Solvers

- Paraphrasers

- Plagiarism Checkers

- Reference Finders

- Spell Checkers

- Summarizers

- Tutoring Websites

Most Popular

13 days ago

Plagiarism vs Copyright

10 days ago

How to Cite Personal Communication in APA

How to cite a dissertation, how to cite page numbers in apa, how to cite journal article mla, how to cite evidence.

Image: unsplash.com

Citing textual evidence is critical to academic writing, professional communications, and even everyday discussions where arguments need to be supported by facts. Your ability to reference specific parts of a text improves credibility and strengthens your arguments, allowing you to present a well-rounded and persuasive case. For this reason, we wanted to give you a quick overview of how to cite evidence effectively, using one method in particular – the RACE strategy .

Introduction to Citing Text Evidence

The core reason for citing evidence is to lend credibility to an argument , showing the audience that the points being made are not just based on personal opinion but are backed by solid references. This practice is foundational in academic settings. There, the questions that students need to respond to are often constructed in a way that requires citing of evidence to support their answers. However, how can we make this process more quick and effectice? The answer lies in the RACE strategy, which is a special framework called to streamlines the process of citing textual evidence.

What is the RACE Strategy?

The RACE strategy stands for Restate, Answer, Cite evidence, and Explain. It is a methodical approach designed to help individuals construct well-structured answers that include textual proof. Let’s break down this method a little bit so you have some kind of impression on what we are going to talk about further.

- Restating the question or prompt in the introduction of the answer helps the writer to set the stage for a clear response.

- The direct answer, taht follows afterwards, presents the key point or thesis of the question.

- After we’e given an answer, we can move on to citing evidence, where we will integrate specific examples from the text to support the answer.

- Finally, we can move on to explaining our evidence. Here, it’s important to elaborating on how the cited examples support the argument we made.

This structured approach not only helps in organizing thoughts but also makes sure that the necessary components of a well-supported argument are present. Just like how to cite the constitution you have to be precise and factual. Let’s explore each step with actual examples to better illustrate how this strategy can help you with the process of citing textual evidence.

Restating basically means paraphrasing the original question or statement within your answer. This step demonstrates your understanding of the question and sets the stage for your response.

By answering directly, you respond to the question and therefore briefly present your main argument or thesis. You should stay clear and concise here, providing a straightforward statement of your position or understanding.

Cite Evidence

Citing evidence is where you integrate specific examples from the text to support your answer. This involves quoting or paraphrasing passages and pointing out where in the text your evidence can be found. Don’t forget to use quotation marks appropriately for direct quotes and to provide context for your citations or let a legal citation machine handle it.

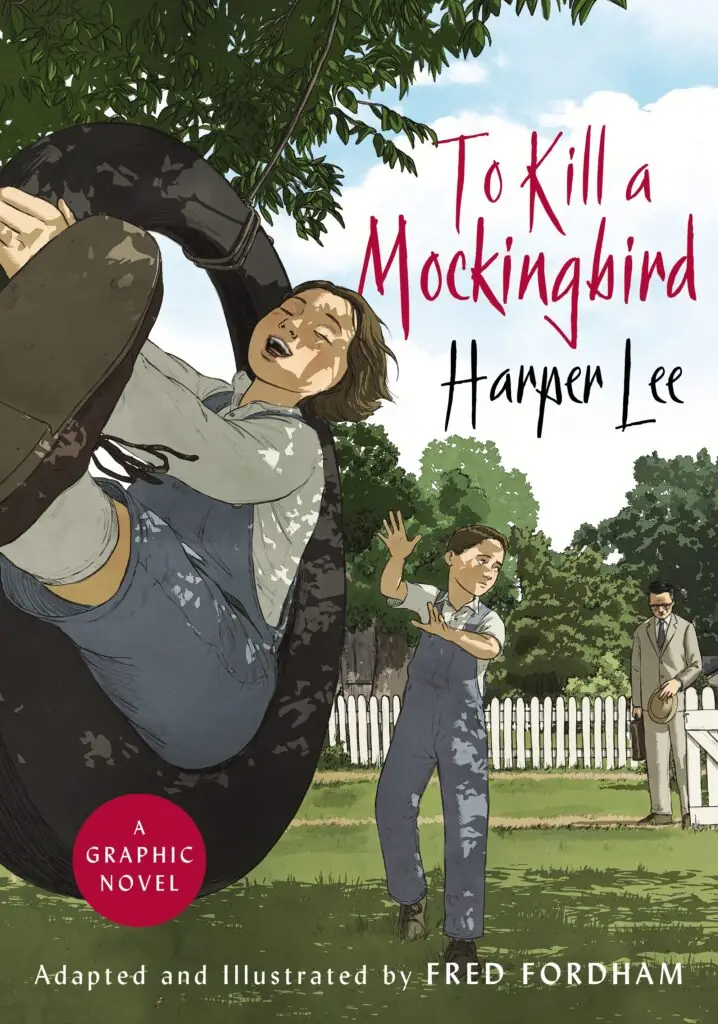

For instance, to support the theme of racial injustice, you might cite evidence by saying,

When explaining, you elaborat on how your cited evidence supports your answer. This step connects your evidence back to your main argument, demonstrating a deeper understanding of the text.

After citing evidence, an explanation could be structured the following way,

To put it all together, here’s how an integrated response using the RACE strategy might look:

Response : ⬇

“The novel ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ primarily explores themes such as racial injustice and the loss of innocence. One of the central themes is racial injustice, which is depicted through the trial of Tom Robinson and its impact on the town of Maycomb. Harper Lee illustrates this theme through the character of Atticus Finch, who states, ‘In our courts, when it’s a white man’s word against a black man’s, the white man always wins.’ (Lee, 1960, p. 295). This quote highlights the deeply ingrained racial biases within the judicial system of Maycomb, underscoring the novel’s critique of racial injustice and its effects on individuals and society as a whole.”

By following the RACE strategy and using actual examples, you can effectively structure clear and relevant responses that add depth to your argumentation. This method not only help in organizing thoughts but also in demonstrating a deep understanding of the text and its main topics.

However, there are a few nuances that you have to be aware of. The first one is the use of quotation marks. Don’t forget them when referencing direct quotes from a text, as they indicate that you took those words verbatim. Furthermore, you have to understand and use citation styles relevant to the discipline or context you write on. This will help you appropriately format your references and avoid unintentional plagiarizing. A quick tip: sentence starters and tags for dialogue can also help with introduction of quoted or paraphrased evidence effectively, as they let the reader or listener easily follow the argument’s progression.

Adapting the RACE Strategy for Distance Learning

Even in the case of distance learnign , the RACE strategy remains a valuable tool for teaching students how to cite evidence effectively. Digital resources such as Google Docs often offer collaborative platforms where teachers can share templates, sentence stems, and color-coded examples to guide students through the response building process.

Moreover, interactive activities facilitated through online tools, can further engage students in practicing citing evidence, with digital resources providing immediate feedback and opportunities for revision. This adaptation help develop the skill of citing textual evidence even in a remote learning setting.

It’s hard to argue that citing textual evidence is useful skill that can help you get far in your academic writing as well as in other more professional fields. Following the RACE strategy and using our tips on referencing, you, as students, can create well-structured and compelling responses (which no professor could argue with).

How can I use the RACE strategy to improve my essay writing?

You can use the RACE strategy to structure your paragraphs or entire essays by ensuring that each section includes a restatement of the question (if applicable), a clear answer or thesis statement, cited evidence from your sources, and an explanation of how this evidence supports your argument. This approach can enhance clarity, coherence, and persuasiveness.

What are some tips for effectively citing evidence in my writing?

Some tips for effectively citing evidence are: using direct quotes from the text with proper quotation marks, paraphrasing accurately while maintaining the original meaning, providing specific examples, and ensuring that your citations are relevant and support your argument. Always include page numbers or other locator information if available.

Is the RACE strategy useful for standardized tests or only for classroom assignments?

The RACE strategy is beneficial for a wide range of writing tasks, including standardized tests, classroom assignments, and even professional writing. Its structured approach to constructing responses makes it a valuable tool for any situation requiring evidence-based writing.

Follow us on Reddit for more insights and updates.

Comments (0)

Welcome to A*Help comments!

We’re all about debate and discussion at A*Help.

We value the diverse opinions of users, so you may find points of view that you don’t agree with. And that’s cool. However, there are certain things we’re not OK with: attempts to manipulate our data in any way, for example, or the posting of discriminative, offensive, hateful, or disparaging material.

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

More from Citation Guides

Remember Me

Is English your native language ? Yes No

What is your profession ? Student Teacher Writer Other

Forgotten Password?

Username or Email

Home / Guides / Citation Guides / Citation Basics / Citing Evidence

Citing Evidence

In this article, you will learn how to cite the most relevant evidence for your audience.

Writing for a specific audience is an important skill. What you present in your writing and how you present it will vary depending on your intended audience.

Sometimes, you have to judge your audience’s level of understanding. For example, a general audience may not have as much background knowledge as an academic audience.

The UNC Writing Center provides a general overview of questions about your audience that you should consider. Click here and read the section, “How do I identify my audience and what they want from me?”

Addressing Audience Bias

In addition to knowledge, values, and concerns, your audience may also hold certain biases , or judgments and prejudices, about a topic.

Take, for example, the topic of the Revolutionary War. Your intended audience may be British economists who see the American Revolution as a rebellion, which hindered British imperialism around the world.

When writing for this audience, you still want to present your claims, reasoning, and evidence to support your argument about the American Revolution, but you don’t want to alienate your British audience. You will need to be sensitive in how you explain American success and its impact on the British Empire.

Quotes, Paraphrases & Audience

Using quotes and paraphrases is a terrific way to both support your argument and make it interesting for the audience to read. You should tailor the use of these quotes and paraphrases to your audience.

Evidence Sources & Audience

Whether you’re quoting or paraphrasing, the source of your evidence matters to your audience . Readers want to see credible sources that they trust.

For example, military historians may feel reassured to see citations from the Journal of Military History (the refereed academic publication for the Society for Military History) in your writing about the American Revolution.

They may be less persuaded by a quote from a historical reenactor’s blog or a more general source like The History Channel . Historical fiction or historical films created for entertainment likely will not impress them at all, unless you are creating a critique of those sources.

It can sometimes be helpful to create an annotated bibliography before writing your paper since the annotations you write will help you to summarize and evaluate the relevance and/or credibility of each of your sources.

Quoting/Paraphrasing with Audience in Mind

Choosing when to use quotes or paraphrases can depend on your audience as well.

If your audience wants details, if you want to grab the attention of your audience, or if audience bias may prevent acceptance of a more generalized statement, use a quote.

If your audience is new to the topic or a more general audience, if they will want to see your conclusions presented quickly, or if a quote would disrupt the reading of your text, a paraphrase is better.

Using Quotes and Paraphrases Effectively: Example

John Luzader, who has worked with the Department of Defense and the National Park Service, can be considered an expert who understands the technical aspects of military history.

Click here to read his “Thoughts on the Battle of Saratoga.” As you read, consider whether you would quote or paraphrase this text when using it as evidence for a school newspaper article explaining why the British surrendered.

Quotes and Paraphrases Example: Explained

A high school newspaper’s audience is usually intelligent and informed but not expert. Unless it is a military academy’s newspaper, it is unlikely that the audience has enough expertise to understand specific technical terms like “redoubt,” “intervisual,” or “British right and rear.”

For this audience, Luzader’s Thoughts on the Battle of Saratoga would work better as a paraphrase:

Military historian John Luzader (2010) argues that the British position on the field at Saratoga allowed the Americans to take the earthwork fort that protected the Redcoats and form a circle around the British, forcing their defeat.

Notice that the above paraphrase uses an in-text citation, which all paraphrases should. Because Luzader’s name is included in the sentence, we only need the year of publication (2010) in parentheses.

Relevant Evidence for Claims and Counterclaims

As a writer, you need to supply the most relevant evidence for claims and counterclaims based on what you know about your audience. Your claim is your position on the subject, while a counterclaim is a point that someone with an opposing view may raise.

Pointing out the strengths and limitations of your evidence in a way that anticipates the audience’s knowledge level, concerns, values, and possible biases helps you select the best evidence for your readers.

Relevant Evidence for Counterclaims: Example

Your audience’s concerns may include a counterclaim you must address. For example, your readers may think that the American Revolution cannot be considered a world war because it was a fight between one country and its colonies.

You should acknowledge these differences in beliefs with evidence, but be sure to return to your original claim, emphasizing why it is correct. Your acknowledgment may look like this (the counterclaim is in italics):

Although the American Revolution was primarily a battle between the British empire and its rebellious North American colonies , the foreign alliances made during the American Revolution helped the colonists survive the war and become a nation. The French Alliance of 1778 shows how foreign intervention was necessary to keep the United States going. As Office of the Historian for the U.S. State Department (2017) explains, “The single most important diplomatic success of the colonists during the War for Independence was the critical link they forged with France.” These alliances with other nations, who provided financial and military support to the colonists, expanded the scope of the Revolution to the point of being a world war.

Now you know how to select the best evidence to include in your writing! Remember to consider your audience, address counterclaims while not straying from your own claim, and use in-text citations for quotes and paraphrases.

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Citation Basics

Harvard Referencing

Plagiarism Basics

Plagiarism Checker

Upload a paper to check for plagiarism against billions of sources and get advanced writing suggestions for clarity and style.

Get Started

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

Indiana University Bloomington Indiana University Bloomington IU Bloomington

- Mission, Vision, and Inclusive Language Statement

- Locations & Hours

- Undergraduate Employment

- Graduate Employment

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Newsletter Archive

- Support WTS

- Schedule an Appointment

- Online Tutoring

- Before your Appointment

- WTS Policies

- Group Tutoring

- Students Referred by Instructors

- Paid External Editing Services

- Writing Guides

- Scholarly Write-in

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Journal Article Writing Groups

- Early Career Graduate Student Writing Workshop

- Workshops for Graduate Students

- Teaching Resources

- Syllabus Information

- Course-specific Tutoring

- Nominate a Peer Tutor

- Tutoring Feedback

- Schedule Appointment

- Campus Writing Program

Writing Tutorial Services

Using evidence.

Like a lawyer in a jury trial, a writer must convince her audience of the validity of her argument by using evidence effectively. As a writer, you must also use evidence to persuade your readers to accept your claims. But how do you use evidence to your advantage? By leading your reader through your reasoning.

The types of evidence you use change from discipline to discipline--you might use quotations from a poem or a literary critic, for example, in a literature paper; you might use data from an experiment in a lab report.

The process of putting together your argument is called analysis --it interprets evidence in order to support, test, and/or refine a claim . The chief claim in an analytical essay is called the thesis . A thesis provides the controlling idea for a paper and should be original (that is, not completely obvious), assertive, and arguable. A strong thesis also requires solid evidence to support and develop it because without evidence, a claim is merely an unsubstantiated idea or opinion.

This Web page will cover these basic issues (you can click or scroll down to a particular topic):

- Incorporating evidence effectively.

- Integrating quotations smoothly.

- Citing your sources.

Incorporating Evidence Into Your Essay

When should you incorporate evidence.

Once you have formulated your claim, your thesis (see the WTS pamphlet, " How to Write a Thesis Statement ," for ideas and tips), you should use evidence to help strengthen your thesis and any assertion you make that relates to your thesis. Here are some ways to work evidence into your writing:

- Offer evidence that agrees with your stance up to a point, then add to it with ideas of your own.

- Present evidence that contradicts your stance, and then argue against (refute) that evidence and therefore strengthen your position.

- Use sources against each other, as if they were experts on a panel discussing your proposition.

- Use quotations to support your assertion, not merely to state or restate your claim.

Weak and Strong Uses of Evidence

In order to use evidence effectively, you need to integrate it smoothly into your essay by following this pattern:

- State your claim.

- Give your evidence, remembering to relate it to the claim.

- Comment on the evidence to show how it supports the claim.

To see the differences between strong and weak uses of evidence, here are two paragraphs.

Weak use of evidence

Today, we are too self-centered. Most families no longer sit down to eat together, preferring instead to eat on the go while rushing to the next appointment (Gleick 148). Everything is about what we want.

This is a weak example of evidence because the evidence is not related to the claim. What does the claim about self-centeredness have to do with families eating together? The writer doesn't explain the connection.

The same evidence can be used to support the same claim, but only with the addition of a clear connection between claim and evidence, and some analysis of the evidence cited.

Stronger use of evidence

Today, Americans are too self-centered. Even our families don't matter as much anymore as they once did. Other people and activities take precedence. In fact, the evidence shows that most American families no longer eat together, preferring instead to eat on the go while rushing to the next appointment (Gleick 148). Sit-down meals are a time to share and connect with others; however, that connection has become less valued, as families begin to prize individual activities over shared time, promoting self-centeredness over group identity.

This is a far better example, as the evidence is more smoothly integrated into the text, the link between the claim and the evidence is strengthened, and the evidence itself is analyzed to provide support for the claim.

Using Quotations: A Special Type of Evidence

One effective way to support your claim is to use quotations. However, because quotations involve someone else's words, you need to take special care to integrate this kind of evidence into your essay. Here are two examples using quotations, one less effective and one more so.

Ineffective Use of Quotation

Today, we are too self-centered. "We are consumers-on-the-run . . . the very notion of the family meal as a sit-down occasion is vanishing. Adults and children alike eat . . . on the way to their next activity" (Gleick 148). Everything is about what we want.

This example is ineffective because the quotation is not integrated with the writer's ideas. Notice how the writer has dropped the quotation into the paragraph without making any connection between it and the claim. Furthermore, she has not discussed the quotation's significance, which makes it difficult for the reader to see the relationship between the evidence and the writer's point.

A More Effective Use of Quotation

Today, Americans are too self-centered. Even our families don't matter as much any more as they once did. Other people and activities take precedence, as James Gleick says in his book, Faster . "We are consumers-on-the-run . . . the very notion of the family meal as a sit-down occasion is vanishing. Adults and children alike eat . . . on the way to their next activity" (148). Sit-down meals are a time to share and connect with others; however, that connection has become less valued, as families begin to prize individual activities over shared time, promoting self-centeredness over group identity.

The second example is more effective because it follows the guidelines for incorporating evidence into an essay. Notice, too, that it uses a lead-in phrase (". . . as James Gleick says in his book, Faster ") to introduce the direct quotation. This lead-in phrase helps to integrate the quotation with the writer's ideas. Also notice that the writer discusses and comments upon the quotation immediately afterwards, which allows the reader to see the quotation's connection to the writer's point.

REMEMBER: Discussing the significance of your evidence develops and expands your paper!

Citing Your Sources

Evidence appears in essays in the form of quotations and paraphrasing. Both forms of evidence must be cited in your text. Citing evidence means distinguishing other writers' information from your own ideas and giving credit to your sources. There are plenty of general ways to do citations. Note both the lead-in phrases and the punctuation (except the brackets) in the following examples:

Quoting: According to Source X, "[direct quotation]" ([date or page #]).

Paraphrasing: Although Source Z argues that [his/her point in your own words], a better way to view the issue is [your own point] ([citation]).

Summarizing: In her book, Source P's main points are Q, R, and S [citation].

Your job during the course of your essay is to persuade your readers that your claims are feasible and are the most effective way of interpreting the evidence.

Questions to Ask Yourself When Revising Your Paper

- Have I offered my reader evidence to substantiate each assertion I make in my paper?

- Do I thoroughly explain why/how my evidence backs up my ideas?

- Do I avoid generalizing in my paper by specifically explaining how my evidence is representative?

- Do I provide evidence that not only confirms but also qualifies my paper's main claims?

- Do I use evidence to test and evolve my ideas, rather than to just confirm them?

- Do I cite my sources thoroughly and correctly?

Produced by Writing Tutorial Services, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN

Writing Tutorial Services social media channels

Unit 4: Fundamentals of Academic Essay Writing

29 Steps for Integrating Evidence

A step-by-step guide for including your “voice”.

To integrate evidence, you need to introduce it, paraphrase (or quote in special circumstances), and then connect the evidence to the topic sentence. Below are the steps for “ICE” or the “hamburger analogy.”

Step 1 Introducing evidence: the top bun or “I”

A sentence of introduction before the paraphrase helps the reader know what evidence will follow. You want to provide a preview for the reader of what outside support you will use.

- Example from the model essay: (“I”/top bun) Peer review can increase a student’s interest and confidence in writing. (“C”/meat) Rather than relying on the teacher, the student is actively involved in the writing process (Bijami et al., 2013, p. 94).

- Notice how the introduction of increasing interest and confidence provides a hint of the evidence that will follow; it links to the idea of becoming a more independent and engaged learner.

Step 2 Paraphrasing and citing evidence: the meat or “C”

Typically, in academic writing, you will not simply paraphrase a single sentence; instead, you will often summarize information from more than one sentence – you will read a section of text, such as a part of a paragraph, a whole paragraph, or even more than one paragraph, and you will extract and synthesize information from what you have read. This means you will summarize that information and cite it.

Paraphrase/summarize the evidence and then include a citation with the following information (A more detailed explanation of documentation, including citations, can be found in Unit 44: Documentation.

- The author’s last name (but if you do not know the author’s name, use the article title).

- The publication date.

- The page number.

Formats for introducing evidence (when you know the author)

- Gambino (2015) explains how social networks help foster personal connections (p. 1).

- According to Gambino (2015), social networks help foster personal connections (p. 1).

- Social networks help foster personal connections (Gambino, 2015, p. 1).

Formats for introducing evidence (when you the author is unknown)

- Several tips for college success are explained (“Preparing for College,” 2015, p. 2).

- Example from the model essay: Rather than relying on the teacher, the student is actively involved in the writing process (Bijami et al., 2013, p. 94).

- Here we can see a paraphrase, not a direct quotation, with proper citation format.

Step 3 Connecting evidence: the bottom bun or “E”

In this step, you must explain the significance of the evidence and how it relates to your topic sentence or to previously mentioned information in the paragraph or essay. This connecting explanation could be one or more sentences. This “bottom bun” is NOT a paraphrase; instead, it is your explanation of why you chose the evidence and how it supports your own ideas.

- Example from the model essay: (“I”/top bun) Peer review can increase a student’s interest and confidence in writing . (“C”/meat) Rather than relying on the teacher, the student is actively involved in the writing process (Bijami et al., 2013, p. 94) . (“E”/bottom bun) As students take more responsibility for their writing, from developing their topic to writing drafts, they become more confident and inspired .

- Notice how the “E” or “bottom bun” elaborates on the idea of becoming an independent learner.

Step 3 Strategies : Questions to ask yourself when analyzing the function of evidence

What “move” is the “E” / bottom bun is making? (e.g. What’s the “function” of the “E” / bottom bun?”)

- Is it interpreting the evidence?

- Is it analyzing the evidence?

- Is it describing an outcome?

- Is it providing an example?

- Is it making a prediction?

- Is it evaluating the evidence?

- Is it challenging the evidence?

- Is it elaborating on evidence that came before in the paragraph/essay?

- Is it comparing the evidence with something else or another piece of evidence?

- Is it connecting the evidence to a previously stated idea in the paragraph/essay?

Choose a function: Evaluate, Compare, Analyze, Connect, Predict

Watch this video: Evidence & Citations

Watch this video on the importance of explaining your evidence and including citations.

From: Ariel Bassett

Language Stems for Integrating Evidence

The sentence stems below can help you develop your command of more complex academic language.

Stems to refer to outside knowledge and/or experts

- It is / has been believed that…

- Researchers have noted that…

- Experts point out that…

- Based on these figures… / These figures show… / The data (seems to) suggest(s)…

Stems for introducing example evidence

- X (year) illustrates this point with an example about… (p. #).

- One of example is…. (X, year, p. #).

- As an example of this/___, ….. (X, year, p. #)

- …. is an illustration / example of… (citation).

- For example, …or For instance, …

Stems to support arguments and claims

- According to X (year), …. (p. #).

- As proof of this, X (year) claims…. (p. #).

- X (year) provides evidence for/that… (p. #).

- X (year) demonstrates that… (p. #).

Stems to draw conclusions (helpful to use in the explanation / bottom bun)

- This suggests / demonstrates / indicates / shows / illustrates…

(In the above examples, you can combine the demonstrative pronoun “this” with a noun. Ex: “these results suggests…” or “this example illustrates…” or “these advantages show….”)

- This means…

- In this way,…

- It is possible that…

- Such evidence seems to suggest… / Such evidence suggests…

Stems to agree with a source (helpful to use in the explanation / bottom bun)

- As X correctly notes…

- As X rightly observes, …

- As X insightfully points out, …

Stems to disagree with a source (helpful to use in the explanation / bottom bun)

- Although X contends that…

- However, it remains unclear whether…

- Critics are quick to point out that…

Academic Writing I Copyright © by UW-Madison ESL Program is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Using Evidence: Citing Sources Properly

Citing sources properly is essential to avoiding plagiarism in your writing. Not citing sources properly could imply that the ideas, information, and phrasing you are using are your own, when they actually originated with another author. Plagiarism doesn't just mean copy and pasting another author's words. Review Amber's blog post, "Avoiding Unintentional Plagiarism," for more information! Plagiarism can occur when authors:

- Do not include enough citations for paraphrased information,

- Paraphrase a source incorrectly,

- Do not use quotation marks, or

- Directly copy and paste phrasing from a source without quotation marks or citations.

Read more about how to avoid these types of plagiarism on the following subpages and review the Plagiarism Detection & Revision Skills video playlist on this page. For more information on avoiding plagiarism, see our Plagiarism Prevention Resource Kit .

Also make sure to consult our resources on citations to learn about the correct formatting for citations.

What to Consider

Citation issues can appear when writers use too much information from a source, rather than including their own ideas and commentary on sources' information. Here are some factors to consider when citing sources:

Remember that the cited material should illustrate rather than substitute for your point. Make sure your paper is more than a collection of ideas from your sources; it should provide an original interpretation of that material. For help with creating this commentary while also avoiding personal opinion, see our Commentary vs. Opinion resource.

The opening sentence of each paragraph should be your topic sentence , and the final sentence in the paragraph should conclude your point and lead into the next. Without these aspects, you leave your reader without a sense of the paragraph's main purpose. Additionally, the reader may not understand your reasons for including that material.

All material that you cite should contribute to your main argument (also called a thesis or purpose statement). When reading the literature, keep that argument in mind, noting ideas or research that speaks specifically to the issues in your particular study. See our synthesis demonstration for help learning how to use the literature in this way.

Most research papers should include a variety of sources from the last 3-5 years. You may find one particularly useful study, but try to balance your references to that study with research from other authors. Otherwise, your paper becomes a book report on that one source and lacks richness of theoretical perspective.

Direct quotations are best avoided whenever possible. While direct quotations can be useful for illustrating a rhetorical choice of your author, in most other cases paraphrasing the material is more appropriate. Using your own words by paraphrasing will better demonstrate your understanding and will allow you to emphasize the ways in which the ideas contribute to your paper's main argument.

Plagiarism Detection & Revising Skills Video Playlist

Citing Sources Video Playlist

Related Resources

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Synthesis

- Next Page: Not Enough Citations

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

- Buy Custom Assignment

- Custom College Papers

- Buy Dissertation

- Buy Research Papers

- Buy Custom Term Papers

- Cheap Custom Term Papers

- Custom Courseworks

- Custom Thesis Papers

- Custom Expository Essays

- Custom Plagiarism Check

- Cheap Custom Essay

- Custom Argumentative Essays

- Custom Case Study

- Custom Annotated Bibliography

- Custom Book Report

- How It Works

- +1 (888) 398 0091

- Essay Samples

- Essay Topics

- Research Topics

- Uncategorized

- Writing Tips

How to Introduce Evidence in an Essay

December 28, 2023

Introducing evidence in an essay serves a crucial purpose – it strengthens your arguments and adds credibility to your claims. Without proper evidence, your essay may lack substance and fail to convince your readers. Evidence helps support your statements, providing solid proof of the validity of your ideas. It demonstrates that you have thoroughly researched your topic and have a strong basis for your arguments. Moreover, evidence adds depth to your writing and allows you to present a persuasive case. By including evidence in your essay, you show that you have considered various perspectives and have made informed conclusions. It is essential to understand the importance of evidence and its role in constructing a well-rounded and convincing essay. In the following sections, we will explore different types of evidence and learn how to effectively incorporate them into your writing.

Types of Evidence

When it comes to introducing evidence in an essay, it is important to consider the types of evidence available to you. Here are some commonly used types:

Statistical Evidence

Introducing evidence in an essay is crucial to support your ideas and arguments. One effective way of doing so is by utilizing statistical evidence. Statistics have the power to provide concrete facts and figures, making your essay more objective and credible.

By incorporating statistical evidence, you can back up your claims with well-researched data, lending an air of authority to your work. Whether you’re discussing social issues, scientific phenomena, or economic trends, statistics can showcase patterns, trends, and correlations that further strengthen your arguments.

Additionally, statistical evidence provides a numerical representation of information, making complex ideas more accessible to readers. It can engage your audience and facilitate their understanding, ensuring that your message resonates effectively.

However, it is important to ensure that your statistical evidence is reliable and obtained from reputable sources. This will boost the credibility of your essay, making it more persuasive and compelling. Remember, statistics add substance and impact to your writing, elevating it from a mere collection of words to a well-supported and convincing piece.

Expert Testimony

Introducing expert testimony in an essay can greatly enhance the credibility and persuasiveness of your arguments. Expert testimony involves quoting or referencing professionals, scholars, or individuals knowledgeable in a specific field to support your claims.

By incorporating the opinions and insights of experts, you can lend authority to your essay. Expert testimony adds a layer of validation to your arguments, demonstrating that your ideas are supported by those who possess extensive knowledge and experience in the subject matter.

Citing experts also strengthens your work by showcasing that you have done thorough research and have sought out trusted authorities in the field. This can establish your expertise as a writer and further establish your credibility with the readers.

When utilizing expert testimony, make sure to reference credible sources and provide proper attribution. This will ensure the integrity of your essay and bolster the confidence readers have in your arguments. Remember, expert testimony can provide valuable insights and earn the trust of your audience, making your essay more persuasive and impactful.

Anecdotal Evidence

Introducing anecdotal evidence in an essay allows you to connect with readers on a personal level while still conveying a persuasive message. Anecdotes are brief, relatable stories that provide real-life examples to support your arguments.

Anecdotal evidence adds a human touch to your essay, capturing the attention and interest of your audience. By sharing personal experiences, or those of others, you can create an emotional connection that resonates with readers.

These stories can be used to illustrate the impact of a particular phenomenon or to provide a compelling argument for your thesis. Anecdotes often invoke empathy and can help readers relate to the topic on a deeper level.

However, it’s crucial to use anecdotal evidence selectively and consider its limitations. While it can engage readers and appeal to their emotions, anecdotal evidence is subjective and may not represent the broader picture. Pairing anecdotal evidence with other types of evidence can strengthen your argument and ensure a more balanced and persuasive essay.

Empirical Evidence

Introducing empirical evidence in an essay involves utilizing observation, experimentation, and scientific data to support your arguments. Empirical evidence relies on systematic methods of data collection and analysis, making it a strong and reliable form of evidence.

By incorporating empirical evidence, you can establish a solid foundation for your essay. It allows you to present findings derived from thorough research, ensuring objectivity and credibility. Whether you’re discussing the effects of a medication, the impact of climate change, or the outcomes of a social program, empirical evidence provides tangible results and measurable outcomes.

Empirical evidence also lends itself to replicability, as others can evaluate and reproduce the research to validate the findings. This further strengthens the validity and persuasiveness of your essay.

When including empirical evidence, it is essential to cite the original studies or research articles, ensuring transparency and acknowledging the sources of your data. By incorporating empirical evidence in your essay, you build a persuasive argument supported by scientific rigor, enhancing the impact and credibility of your work.

Utilizing these different types of evidence allows for a well-rounded and convincing essay. It is important to select the type of evidence that best suits your argument and topic. In the following sections, we will delve into how to evaluate the credibility of evidence and effectively incorporate it into your essay.

Evaluating the Credibility of Evidence

When introducing evidence in an essay, it is crucial to evaluate its credibility to ensure the soundness of your arguments. Here are key factors to consider when assessing the reliability of evidence:

- Source credibility: Determine the expertise and authority of the source. Is it from a reputable organization, expert in the field, or peer-reviewed journal?

- Relevance: Assess the relevance of the evidence to your topic. Does it directly address your thesis or support your main points?

- Currency: Consider the recency of the evidence. Is it up-to-date or outdated? Depending on your topic, it may be necessary to prioritize recent information.

- Consistency: Look for consistency among multiple sources. Does the evidence align with other reliable sources, or is it an outlier?

- Sample size: If using statistical evidence, examine the sample size. Larger samples generally provide more representative results.

- Methodology: Evaluate the rigor of the research methods used to gather the evidence. Was it conducted using scientifically accepted practices?

- Bias: Be aware of potential bias in the evidence. Consider the funding sources, ideological leanings, or conflicts of interest that might impact the objectivity of the information.

By critically evaluating the credibility of evidence, you can ensure that your essay is well-supported and persuasive. Remember to weigh the strengths and weaknesses of different types of evidence to create a balanced and convincing argument.

Incorporating Evidence into the Essay

When writing an essay, incorporating evidence is essential to support your arguments and provide credibility to your claims. By seamlessly integrating evidence into your essay, you can enhance its overall quality and convince your readers of the validity of your ideas.

Here are some key strategies to effectively introduce evidence in your essay:

- Provide context: Start by giving your readers contextual information about the evidence. Explain the source, its significance, and how it relates to your argument. This helps your readers understand its relevance and establishes a solid foundation for your evidence.

- Use signal phrases: Use appropriate signal phrases to introduce your evidence. These phrases can indicate that you are about to present evidence, such as “According to,” “For example,” or “As evidence suggests.” Signal phrases create a smooth transition between your own ideas and the evidence you are presenting.

- Blend it into your sentence structure: Rather than dropping evidence abruptly, integrate it seamlessly into your sentence structure. This allows your evidence to flow naturally and become an integral part of your argument. This technique helps avoid the trap of using evidence as standalone sentences or paragraphs.

- Explain the significance: After presenting the evidence, take some time to explain its significance in relation to your argument. Analyze and interpret the evidence, showing your readers how it supports your main thesis and strengthens your overall stance.