- SOCIETY OF PROFESSIONAL JOURNALISTS

Caroline Hendrie joins SPJ President Ashanti Blaize-Hopkins to discuss her career, the state of the industry, and her vision for SPJ’s next chapter.

Home > Ethics > Ethics Case Studies

Ethics Ethics Case Studies

The SPJ Code of Ethics is voluntarily embraced by thousands of journalists, regardless of place or platform, and is widely used in newsrooms and classrooms as a guide for ethical behavior. The code is intended not as a set of "rules" but as a resource for ethical decision-making. It is not — nor can it be under the First Amendment — legally enforceable. For an expanded explanation, please follow this link .

For journalism instructors and others interested in presenting ethical dilemmas for debate and discussion, SPJ has a useful resource. We've been collecting a number of case studies for use in workshops. The Ethics AdviceLine operated by the Chicago Headline Club and Loyola University also has provided a number of examples. There seems to be no shortage of ethical issues in journalism these days. Please feel free to use these examples in your classes, speeches, columns, workshops or other modes of communication.

Kobe Bryant’s Past: A Tweet Too Soon? On January 26, 2020, Kobe Bryant died at the age of 41 in a helicopter crash in the Los Angeles area. While the majority of social media praised Bryant after his death, within a few hours after the story broke, Felicia Sonmez, a reporter for The Washington Post , tweeted a link to an article from 2003 about the allegations of sexual assault against Bryant. The question: Is there a limit to truth-telling? How long (if at all) should a journalist wait after a person’s death before resurfacing sensitive information about their past?

A controversial apology After photographs of a speech and protests at Northwestern University appeared on the university's newspaper's website, some of the participants contacted the newspaper to complain. It became a “firestorm,” — first from students who felt victimized, and then, after the newspaper apologized, from journalists and others who accused the newspaper of apologizing for simply doing its job. The question: Is an apology the appropriate response? Is there something else the student journalists should have done?

Using the ‘Holocaust’ Metaphor People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, or PETA, is a nonprofit animal rights organization known for its controversial approach to communications and public relations. In 2003, PETA launched a new campaign, named “Holocaust on Your Plate,” that compares the slaughter of animals for human use to the murder of 6 million Jews in WWII. The question: Is “Holocaust on Your Plate” ethically wrong or a truthful comparison?

Aaargh! Pirates! (and the Press) As collections of songs, studio recordings from an upcoming album or merely unreleased demos, are leaked online, these outlets cover the leak with a breaking story or a blog post. But they don’t stop there. Rolling Stone and Billboard often also will include a link within the story to listen to the songs that were leaked. The question: If Billboard and Rolling Stone are essentially pointing readers in the right direction, to the leaked music, are they not aiding in helping the Internet community find the material and consume it?

Reigning on the Parade Frank Whelan, a features writer who also wrote a history column for the Allentown, Pennsylvania, Morning Call , took part in a gay rights parade in June 2006 and stirred up a classic ethical dilemma. The situation raises any number of questions about what is and isn’t a conflict of interest. The question: What should the “consequences” be for Frank Whelan?

Controversy over a Concert Three former members of the Eagles rock band came to Denver during the 2004 election campaign to raise money for a U.S. Senate candidate, Democrat Ken Salazar. John Temple, editor and publisher of the Rocky Mountain News, advised his reporters not to go to the fundraising concerts. The question: Is it fair to ask newspaper staffers — or employees at other news media, for that matter — not to attend events that may have a political purpose? Are the rules different for different jobs at the news outlet?

Deep Throat, and His Motive The Watergate story is considered perhaps American journalism’s defining accomplishment. Two intrepid young reporters for The Washington Post , carefully verifying and expanding upon information given to them by sources they went to great lengths to protect, revealed brutally damaging information about one of the most powerful figures on Earth, the American president. The question: Is protecting a source more important than revealing all the relevant information about a news story?

When Sources Won’t Talk The SPJ Code of Ethics offers guidance on at least three aspects of this dilemma. “Test the accuracy of information from all sources and exercise care to avoid inadvertent error.” One source was not sufficient in revealing this information. The question: How could the editors maintain credibility and remain fair to both sides yet find solid sources for a news tip with inflammatory allegations?

A Suspect “Confession” John Mark Karr, 41, was arrested in mid-August in Bangkok, Thailand, at the request of Colorado and U.S. officials. During questioning, he confessed to the murder of JonBenet Ramsey. Karr was arrested after Michael Tracey, a journalism professor at the University of Colorado, alerted authorities to information he had drawn from e-mails Karr had sent him over the past four years. The question: Do you break a confidence with your source if you think it can solve a murder — or protect children half a world away?

Who’s the “Predator”? “To Catch a Predator,” the ratings-grabbing series on NBC’s Dateline, appeared to catch on with the public. But it also raised serious ethical questions for journalists. The question: If your newspaper or television station were approached by Perverted Justice to participate in a “sting” designed to identify real and potential perverts, should you go along, or say, “No thanks”? Was NBC reporting the news or creating it?

The Media’s Foul Ball The Chicago Cubs in 2003 were five outs from advancing to the World Series for the first time since 1945 when a 26-year-old fan tried to grab a foul ball, preventing outfielder Moises Alou from catching it. The hapless fan's identity was unknown. But he became recognizable through televised replays as the young baby-faced man in glasses, a Cubs baseball cap and earphones who bobbled the ball and was blamed for costing the Cubs a trip to the World Series. The question: Given the potential danger to the man, should he be identified by the media?

Publishing Drunk Drivers’ Photos When readers of The Anderson News picked up the Dec. 31, 1997, issue of the newspaper, stripped across the top of the front page was a New Year’s greeting and a warning. “HAVE A HAPPY NEW YEAR,” the banner read. “But please don’t drink and drive and risk having your picture published.” Readers were referred to the editorial page where White explained that starting in January 1998 the newspaper would publish photographs of all persons convicted of drunken driving in Anderson County. The question: Is this an appropriate policy for a newspaper?

Naming Victims of Sex Crimes On January 8, 2007, 13-year-old Ben Ownby disappeared while walking home from school in Beaufort, Missouri. A tip from a school friend led police on a frantic four-day search that ended unusually happily: the police discovered not only Ben, but another boy as well—15-year-old Shawn Hornbeck, who, four years earlier, had disappeared while riding his bike at the age of 11. Media scrutiny on Shawn’s years of captivity became intense. The question: Question: Should children who are thought to be the victims of sexual abuse ever be named in the media? What should be done about the continued use of names of kidnap victims who are later found to be sexual assault victims? Should use of their names be discontinued at that point?

A Self-Serving Leak San Francisco Chronicle reporters Mark Fainaru-Wada and Lance Williams were widely praised for their stories about sports figures involved with steroids. They turned their investigation into a very successful book, Game of Shadows . And they won the admiration of fellow journalists because they were willing to go to prison to protect the source who had leaked testimony to them from the grand jury investigating the BALCO sports-and-steroids. Their source, however, was not quite so noble. The question: Should the two reporters have continued to protect this key source even after he admitted to lying? Should they have promised confidentiality in the first place?

The Times and Jayson Blair Jayson Blair advanced quickly during his tenure at The New York Times , where he was hired as a full-time staff writer after his internship there and others at The Boston Globe and The Washington Post . Even accusations of inaccuracy and a series of corrections to his reports on Washington, D.C.-area sniper attacks did not stop Blair from moving on to national coverage of the war in Iraq. But when suspicions arose over his reports on military families, an internal review found that he was fabricating material and communicating with editors from his Brooklyn apartment — or within the Times building — rather than from outside New York. The question: How does the Times investigate problems and correct policies that allowed the Blair scandal to happen?

Cooperating with the Government It began on Jan. 18, 2005, and ended two weeks later after the longest prison standoff in recent U.S. history. The question: Should your media outlet go along with the state’s request not to release the information?

Offensive Images Caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad didn’t cause much of a stir when they were first published in September 2005. But when they were republished in early 2006, after Muslim leaders called attention to the 12 images, it set off rioting throughout the Islamic world. Embassies were burned; people were killed. After the rioting and killing started, it was difficult to ignore the cartoons. Question: Do we publish the cartoons or not?

The Sting Perverted-Justice.com is a Web site that can be very convenient for a reporter looking for a good story. But the tactic raises some ethical questions. The Web site scans Internet chat rooms looking for men who can be lured into sexually explicit conversations with invented underage correspondents. Perverted-Justice posts the men’s pictures on its Web site. Is it ethically defensible to employ such a sting tactic? Should you buy into the agenda of an advocacy group — even if it’s an agenda as worthy as this one?

A Media-Savvy Killer Since his first murder in 1974, the “BTK” killer — his own acronym, for “bind, torture, kill” — has sent the Wichita Eagle four letters and one poem. How should a newspaper, or other media outlet, handle communications from someone who says he’s guilty of multiple sensational crimes? And how much should it cooperate with law enforcement authorities?

A Congressman’s Past The (Portland) Oregonian learned that a Democratic member of the U.S. Congress, up for re-election to his fourth term, had been accused by an ex-girlfriend of a sexual assault some 28 years previously. But criminal charges never were filed, and neither the congressman, David Wu, nor his accuser wanted to discuss the case now, only weeks before the 2004 election. Question: Should The Oregonian publish this story?

Using this Process to Craft a Policy It used to be that a reporter would absolutely NEVER let a source check out a story before it appeared. But there has been growing acceptance of the idea that it’s more important to be accurate than to be independent. Do we let sources see what we’re planning to write? And if we do, when?

SPJ News SPJ continues to call for the release of Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich and all imprisoned journalists Region 7 Mark of Excellence Awards 2023 winners announced Region 1 Mark of Excellence Awards 2023 winners announced

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

Indiana University Bloomington Indiana University Bloomington IU Bloomington

- “Ad”mission of guilt

- “Do I stop him?”

- Newspaper joins war against drugs

- Have I got a deal for you!

- Identifying what’s right

- Is “Enough!” too much?

- Issues of bench and bar

- Knowing when to say “when!”

- Stop! This is a warning…

- Strange bedfellows

- Gambling with being first

- Making the right ethical choice can mean winning by losing

- Playing into a hoaxster’s hands

- “They said it first”

- Is it news, ad or informercial?

- Letter to the editor

- Games publishers play

- An offer you can refuse

- An oily gift horse

- Public service . . . or “news-mercials”

- As life passes by

- Bringing death close

- A careless step, a rash of calls

- Distortion of reality?

- Of life and death

- Naked came the rider

- “A photo that had to be used”

- A picture of controversy

- Freedom of political expression

- Brother, can you spare some time?

- Columnist’s crusade OK with Seattle

- Kiss and tell

- The making of a govenor

- Past but not over

- Of publishers and politics

- To tell the truth

- Truth & Consequences

- “Truth boxes”

- When journalists become flacks

- A book for all journalists who believe

- The Billboard Bandit

- Food for thought

- Grand jury probe

- Judgement on journalists

- Lessons from an ancient spirit

- Lying for the story . . .

- Newspaper nabs Atlanta’s Dahmer

- One way to a good end

- Over the fence

- “Psst! Pass it on!”

- Rules aren’t neat on Crack Street

- “Someone had to be her advocate”

- Trial by Fire

- Trial by proximity

- Using deceit to get the truth

- When advocacy is okay

- Witness to an execution

- Are we our brother’s keeper? . . . You bet we are!

- Betraying a trust

- Broken promise

- “But I thought you were . . . ”

- “Can I take it back?”

- Competitive disadvantage

- Getting it on tape

- The great quote question

- How to handle suicide threats

- Let’s make a deal!

- A phone-y issue?

- The source wanted out

- The story that died in a lie

- Thou shalt not break thy promise

- Thou shalt not concoct thy quote

- Thou shalt not trick thy source

- Too good to be true

- Vulnerable sources and journalistic responsibility

- The way things used to be . . .

- When a story just isn’t worth it

- When a story source threatens suicide

- When public should remain private

- The ethics of “outing”

- “For personal reasons”

- Intruding on grief

- Intruding on private pain

- Privacy case settled against TV station

- Seeing both sides

- Two views on “outing”

- Unwanted spotlight

- Whose right is it anyway?

- Other views on the Christine Busalacchi case

- The death of a soldier

- Firing at Round Rock

- A kinder, gentler news media

- Operation: Buy yourself a parade

- Rallying ’round the flag

- “Salute to military” ads canceled

- Tell the truth, stay alive

- The windbags of war

- Absent with no malice

- Anonymity for rape victims . . .

- An exception to the rule

- The boy with a broken heart

- Civilly suitable

- Creating a victim

- “Everyone already knew”

- An exceptional case

- Innocent victims

- Minor infraction

- Names make news

- Naming a victim

- Naming “johns”

- Profile of controversy

- What the media all missed

- Punishing plagiarizers

- Sounding an alarm on AIDS

- Suffer the children

- Anchor’s away

- The day the earth stood still

- Doing your own ethics audit

- Good guys, bad guys and TV news

- Is it just me, or . . . ?

- The Post’s exam answer story

- TV station “teases” suicide

- Yanking Doonesbury

- The year in review

- Colorado media’s option play

- Deadly lesson

- Deciding which critically ill person gets coverage

- When journalists play God . . .

- A delicate balance

- The Fallen Servant

- Handle with care

- It’s the principle, really

- Killing news

- Maybe what seems so right is wrong

- On the line

- Protest and apology after Daily Beacon story

- Red flag for badgering

- Sharing the community’s grief

- The “super-crip” stereotype

- “And then he said *&%*!!!”

- When big is not better

- When the KKK comes calling

- Not the straight story

- Agreeing to disagree

- All in the family

- Family feud

- Author! Author!

- The Bee that roared

- Brewing controversy

- Building barriers

- Other views from librarians

- The ethics of information selling

- Close to home

- Family ties

- How now, sacred cow?

- The ties that bind

- “Like any other story”

- When your newspaper is the news

- Not friendly fire

- Overdraft on credibility?

- The problem is the writing

- Written rules can be hazardous

- Project censored, sins of omission and the hardest “W” of all – “why”

- Risking the newsroom’s image

- The Media School

Ethics Case Studies

Ethics cases online.

This set of cases has been created for teachers, researchers, professional journalists and consumers of news to help them explore ethical issues in journalism. The cases raise a variety of ethical problems faced by journalists, including such issues as privacy, conflict of interest, reporter- source relationships, and the role of journalists in their communities.

The initial core of this database comes from a series of cases developed by Barry Bingham, Jr., and published in his newsletter, FineLine. The school is grateful to Bingham for his permission to make these cases available to a wider audience.

You may download cases for classes, research or personal use. Permission is granted for academic use of these cases, including inclusion in course readers for specific college courses. This permission does not extend to the republication of the cases in books, journals or electronic form.

Note: We are indebted to Professor Emeritus David Boeyink, who developed this project several years ago.

Aiding law enforcement

- “Ad”mission of guilt: Court-ordered ads raise ethical questions

- “Do I stop him?”: Reporter’s arresting question is news

- Fairness: A casualty of the anti-drug crusade

- Newspaper joins war against drugs: Standard-Times publishes photos of all suspected drug offenders

- Have I got a deal for you!: The line between cooperation and collusion

- Identifying what’s right: Photographer’s ID used in hostage release

- Is “Enough!” too much?: Editors split on anti-drug coupons

- Issues of bench and bar: In this case, a TV reporter is the judge

- Knowing when to say “when!”: Drawing the line at cooperating with authorities

- Stop! This is a warning . . . : Suppressing news at police request

- Strange Bedfellows: Federal agents in a TV newsroom

Being first

- Gambling with being first: The media drive to score on the Isiah Thomas story

- Playing into a hoaxster’s hands: How the Virginia media got suckered

- “They said it first”: Is that reason for going for the story?

Bottom-line decisions

- Is it news, ad or infomercial?: The line between news and advertising is going, going . . .

- Games publishers play: Allowing an advertiser to call the shots

- An offer you can refuse: The selling of Cybill to the Enquirer

- An oily gift horse: saying “No!” to Exxon

- Public service. . .or “news-mercials”: The blending of television news and advertising

Controversial photos

- As life passes by: A journalist’s role: watch and wait

- Bringing death close: Publishing photographs of human tragedy

- A careless step, a rash of calls: “Unusual” photo of AIDS walkathon raises hackles”

- Distortion of reality?: “Punk for Peace” photograph draws fire

- Of life and death: Photos capture woman’s last moments

- “A photo that had to be used”: Anatomy of a newspaper’s decision

- A picture of controversy: Pulitzer photos show diverse editorial standards

Covering politics

- Freedom of political expression: Do journalists forfeit their right?

- Brother, can you spare some time?: TV stations give candidates air time

- Columnist’s crusade OK with Seattle Times

- Kiss and tell: Publishing details of a mayor’s personal life

- The making of a governor: How media fantasy swayed an election

- Past but not over: When history collides with the Present

- Of publishers and politics: Byline protest threatened at Star Tribune

- To tell the truth: Why I didn’t; why I regret it

- Truth & Consequences: The public’s right to know . . . at what cost?

- “Truth boxes”: Media monitoring of TV campaign ads

- When journalists become flacks: Two views on what to do and when to do it

Getting the story

- A book for all journalists who believe: Accuracy is our highest ethical debate

- The Billboard Bandit: Did the newspaper get graffiti on its reputation

- Food for thought: You are what you eat . . . and do

- Grand jury probe: TV journalists indicted for illegal dogfight

- Judgment on journalists: Do they defiantly put themselves “above the law?”

- Lessons from an ancient spirit: Why I participated in a peyote ritual

- Lying for the story . . . :Or things they don’t teach in journalism school

- Newspaper nabs Atlanta’s Dahmer: Another predator who should’ve been stopped: Was it homophobia?

- One way to a good end: Reporter cuts corners to test capital drug program

- Over the fence: A case of crossing the line for a story

- “Psst! Pass it on!”: Why are journalists spreading rumors?

- Rules aren’t neat on Crack Street: Journalists know the rules; they also know that the rules don’t always apply when confronted with life-threatening situations

- “Someone had to be her advocate”: A newspaper’s crusade to keep a child’s death from being forgotten

- Trial by Fire: Boy “hero” story tests media

- Trial by proximity: How close is too close for a jury and a reporter?

- Using deceit to get the truth: When there’s just no other way

- When advocacy is okay: Access is an acceptable journalist’s cause

- White lies: Bending the truth to expose injustice

- Witness to an execution: KQED sues to videotape capital punishment

Handling sources

- Are we our brother’s keeper? . . . You bet we are!

- Betraying a trust: Our story wronged a naive subject

- Broken Promise: Breaching a reporter-source confidence

- “But I thought you were . . .”: When a source doesn’t know you are a reporter

- “Can I take it back?”: Why we told our source ‘yes’

- Competitive disadvantage: Business blindsided by unnamed sources

- Getting it on tape: What if you don’t tell them?

- The great quote question: How much tampering with quotations can journalists ethically do?

- Let’s make a deal!: The dangers of trading with sources

- A phone-y issue?: Caller ID raises confidentiality questions

- The source wanted out: Why our decision was ‘no’

- The story that died in a lie: Questions about truthfulness kill publication

- Thou shalt not break thy promise: Supreme Court rules on betraying sources’ anonymity

- Thou shalt not concoct thy quote: Supreme Court decides on the rules of the quotation game

- Thou shalt not trick thy source: Many a slip twixt the promise and the page

- Too good to be true: Blowing the whistle on a lying source

- Vulnerable sources and journalistic responsibility: Are we our brother’s keeper?

- The way things used to be . . . : Who says this new “objectivity” is better?

- When a story just isn’t worth it: Holding information to protect a good source

- When a story source threatens suicide: “I’m going to kill myself!”

Invading privacy

- The ethics of “outing”: Breaking the silence code on homosexuality

- “For personal reasons”: Balancing privacy with the right to know

- Intruding on grief: Does the public really have a “need to know?”

- Intruding on private pain: Emotional TV segment offers hard choice

- Seeing both sides: A personal and professional dilemma

- Two views on “outing”: When the media do it for you

- Two views on “outing”: When you do it yourself

- Unwanted Spotlight: When private people become part of a public story

- Whose right is it anyway?: Videotape of accident victim raises questions about rights to privacy

Military Issues

- The death of a soldier: Hometown decision for hometown hero

- Firing at Round Rock: Editor says “unpatriotic” story led to dismissal

- A kinder, gentler news media?: Post-war coverage shows sensitivity to families

- Operation: Buy yourself a parade: New York papers pitch in for hoopla celebrating hide-and-seek war

- Rallying ’round the flag: The press as U.S. propagandists

- “Salute to military” ads canceled

- Tell the truth, stay alive: In covering a civil war, honesty is the only policy

- The windbags of war: Television’s gung-ho coverage of the Persian Gulf situation

Naming newsmakers

- Absent with no malice: Omitting part of the story for a reason

- Anonymity for rape victims . . . : should the rules change?

- An exception to the rule: a decision to change names

- The boy with a broken heart: Special problems when juveniles are newsmakers

- Civilly suitable: If law requires less, should media reveal more?

- Creating a victim: Plot for a fair story may not be foolproof

- “Everyone already knew”: A weak excuse for abandoning standards

- An exceptional case: Hartford Courant names rape victim

- Innocent victims: Naming the guilty . . . but guiltless

- Minor infraction: A newspaper’s case for breaking the law

- Names make news: One newspaper debates when and why

- Naming a victim: When do you break your own rule?

- Naming “johns”: Suicide raises ethical questions about policy

- Profile of controversy: New York Times reporter defends story on Kennedy rape claimant

- What the media all missed: Times reporter finally sets record straight on Palm Beach rape profile

- Punishing plagiarizers: Does public exposure fit the sin?

- Sounding an alarm on AIDS: Spreading the word about someone who’s spreading the disease

- Suffer the Children: Journalists are guilty of child misuse

Other topics

- Anchor’s away: Where in the world is she? Or does it matter?

- The day the earth stood still: How the media covered the “earthquake”

- Good guys, bad guys and TV news: How television and other media promote police violence

- The Post’s exam answer story

- TV station “teases” suicide

- The year in review: 1990’s biggest ethical headaches and journalistic bloopers

Sensitive news topics

- Colorado media’s option play: Most passed; did they also fumble?

- Deadly lesson: Warning about sexual asphyxiation

- A delicate balance: Mental breakdowns & news coverage

- The Fallen Servant: When a hero is not a hero

- Handle with care: Priest murder story required extra sensitivity

- It’s the principle, really: Timing and people’s money matter, too

- Killing news: Responsible coverage of suicides

- Maybe what seems so right is wrong: A medical condition media-generated money can’t cure

- On the line: A reporter’s job vs. human decency

- Red flag for badgering: Ombudsman takes sportswriter to task

- Sharing the community’s grief: Little Rock news coverage of three teen-age suicides

- Suffer the children: Was story on molestation worth the human cost?

- The “super-crip” stereotype: Press victimization of disabled people

- “And then he said *&%*!!!”: When sexist and vulgar remarks are new

- When big is not better: Playing down a story for the community good

- When the KKK comes calling: What’s the story?

- Not the straight story: Can misleading readers ever be justified?

Workplace issues

- Agreeing to disagree: How one newspaper handles off-hour activities

- All in the family: When a journalist’s spouse creates a conflict of interests

- Family feud: Handling conflicts between journalists and partners

- Author! Author!: Ethical dilemmas when reporters turn author

- The Bee that roared: Taking a stand for editorial independence

- Brewing controversy: The commercialization of Linda Ellerbee

- Building barriers: The case against financial involvement

- Other views from librarians: When interests of client and newsroom conflict

- The ethics of information selling: Problems for library reference services

- Close to home: When your newsroom is part of the story

- Family Ties: When are relationships relationships relevant?

- How now, sacred cow?: United Way’s favored treatment by the media

- The ties that bind: Publisher’s link to United Way raises questions

- “Like any other story”: Can it be when it’s your union vs. your paper?

- When your newspaper is the news: Editors discuss their experiences

- Not friendly fire: News director at odds with CBS over story

- Overdraft on credibility?: Reporter faces conflict-of-interest charges

- Written rules can be hazardous: A lawyer views ethics codes

- Project censored, sins of omission and the hardest “W” of all – “why”

- Risking the newsroom’s image: How editors, in a good cause, can strain independence

Ethics Case Studies resources and social media channels

- Journalism and Media Ethics Cases

- Markkula Center for Applied Ethics

- Focus Areas

- Journalism and Media Ethics

- Journalism and Media Ethics Resources

For permission to reprint articles, submit requests to [email protected] .

How might news platforms and products ensure that ethical journalism on chronic issues is not drowned out by the noise of runaway political news cycles?

How can media institutions facilitate the free flow of information and promote truth during an election cycle shrouded in misinformation?

A reporter faces a choice between protecting a source or holding a source accountable for their public actions.

Should a source’s name be redacted retroactively from a student newspaper’s digital archive?

Should a student editor decline to publish an opinion piece that is culturally insensitive?

A tweet goes viral, but its news value is questionable.

What should student editors do if an opinion piece is based on factual inaccuracies?

Do student journalists’ friendships constitute a conflict of interest?

Is granting sexual assault survivors anonymity an act of journalistic compassion, or does it risk discrediting them?

Should student journalists grant anonymity to protect undocumented students?

- More pages:

HIGHLY COMMENDED FOR BEST OVERALL DIGITAL MEDIA AT THE 2022 SPA AWARDS.

Beginner’s Guide to Case Studies In Journalism

![case study in journalism Image shows a desk with a hand writing on papers. [Finding case studies journalism]](https://www.empowordjournalism.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/unseen-studio-s9CC2SKySJM-unsplash-1-scaled-e1711527418190-1035x425.jpg)

Lily Gilbey

Learning how to find case studies and implement them into your research is fundamental to creating powerful journalism.

Case studies, relaying important and interesting experiences, can bring a story to life. Including case studies in your work can also give a platform to those who deserve a safe space to tell their story.

Case Studies In Journalism

Case studies can provide human perspective and experience, which, in turn, can make stories more engaging and relatable. This human connection allows the audience to have a deeper attachment and understanding of the subject matter .

A case study can accompany a feature, personalise a news story or even be published by itself.

Personal accounts of serious matters can influence an audience’s emotional connection to the case study and spark action from readers, for example, by encouraging them to sign a petition or inspire meaningful conversations.

Case studies also allow us to diversify perspectives by enabling journalists to represent different experiences of cultures and communities, which can help shape a well-rounded and comprehensive story. This can also give a platform to those who are often underrepresented in the media and amplify marginalised voices.

Finding Case Studies

To find your case study, you must specify the topic of the story you are trying to produce. Doing this allows you to narrow down your search and relevant people with stories and experiences that align with the theme of the story.

Social media can be a valuable tool for this. Platforms like X, Facebook and LinkedIn can be useful for finding sources and reaching out to them, as long as their privacy settings allow it. Twitter Advanced Search allows you to filter tweets by location, keywords, and dates.

Resources like X’s #JournoRequest hashtag can make finding your source as simple as sending out a tweet. Individuals typically tweet a specific call for sources with certain experiences or expertise. A #JournoRequest can include your deadline, the publication and how to contact you. It also lets accounts like PR & Journo Requests and Press Plugs know you’re looking for sources. You can also ask for retweets explicitly if you’re looking for sources outside of your general algorithm.

O nline forums and communities are another great way to source case studies. A quick search of your topic on Reddit could lead you to hundreds of people with relevant and interesting stories. Reaching out to local charities and campaigns can also be a good way of finding case studies.

Lily Canter, journalist and lecturer at Sheffield University, emphasises the use of PR agencies and Press Offices in finding case studies, as they already have an established database of people who can be contacted. The Journalist Enquiry Service is also free to use, and allows you send a request to hundreds of relevant experts, charities and PRs.

Ethical Considerations Of Using Case Studies

As with all aspects of journalism, ethics are fundamental to sourcing and hearing from a case study, and o btaining informed consent is extremely important. Additionally, it is your responsibility to be fully transparent about the purpose of the story and the potential consequences it might have when it is published.

It is equally crucial to approach personal topics with sensitivity, bearing in mind that they may have the potential to trigger case studies or audiences. It is therefore important not to approach people in an intrusive way which may cause unnecessary harm.

The topic of privacy should be always discussed prior to publishing a case study, especially when dealing with sensitive stories. When necessary, you can use pseudonyms to anonymise sources.

When presenting case studies, it’s of the utmost important to remain truthful and avoid distorting the narrative, which could cause harm to your sources.

THE ART OF WRITING A STELLAR OPINION PIECE

Navigating sensitive reporting: a journalist’s guide, disability-inclusive language in journalism.

Featured image courtesy of Vlada Karpovich via Pexels . No changes or alterations have been made to this image. Image license found here .

Hi, I'm Lily, and i'm currently studying my Masters Degree in Visual Journalism. My passion for motorsport encouraged me to pursue my journalism career further through my writing.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Privacy Policy Designed using Unos . Powered by WordPress .

Privacy Overview

McCombs School of Business

- Español ( Spanish )

Videos Concepts Unwrapped View All 36 short illustrated videos explain behavioral ethics concepts and basic ethics principles. Concepts Unwrapped: Sports Edition View All 10 short videos introduce athletes to behavioral ethics concepts. Ethics Defined (Glossary) View All 58 animated videos - 1 to 2 minutes each - define key ethics terms and concepts. Ethics in Focus View All One-of-a-kind videos highlight the ethical aspects of current and historical subjects. Giving Voice To Values View All Eight short videos present the 7 principles of values-driven leadership from Gentile's Giving Voice to Values. In It To Win View All A documentary and six short videos reveal the behavioral ethics biases in super-lobbyist Jack Abramoff's story. Scandals Illustrated View All 30 videos - one minute each - introduce newsworthy scandals with ethical insights and case studies. Video Series

Case Studies UT Star Icon

Case Studies

More than 70 cases pair ethics concepts with real world situations. From journalism, performing arts, and scientific research to sports, law, and business, these case studies explore current and historic ethical dilemmas, their motivating biases, and their consequences. Each case includes discussion questions, related videos, and a bibliography.

A Million Little Pieces

James Frey’s popular memoir stirred controversy and media attention after it was revealed to contain numerous exaggerations and fabrications.

Abramoff: Lobbying Congress

Super-lobbyist Abramoff was caught in a scheme to lobby against his own clients. Was a corrupt individual or a corrupt system – or both – to blame?

Apple Suppliers & Labor Practices

Is tech company Apple, Inc. ethically obligated to oversee the questionable working conditions of other companies further down their supply chain?

Approaching the Presidency: Roosevelt & Taft

Some presidents view their responsibilities in strictly legal terms, others according to duty. Roosevelt and Taft took two extreme approaches.

Appropriating “Hope”

Fairey’s portrait of Barack Obama raised debate over the extent to which an artist can use and modify another’s artistic work, yet still call it one’s own.

Arctic Offshore Drilling

Competing groups frame the debate over oil drilling off Alaska’s coast in varying ways depending on their environmental and economic interests.

Banning Burkas: Freedom or Discrimination?

The French law banning women from wearing burkas in public sparked debate about discrimination and freedom of religion.

Birthing Vaccine Skepticism

Wakefield published an article riddled with inaccuracies and conflicts of interest that created significant vaccine hesitancy regarding the MMR vaccine.

Blurred Lines of Copyright

Marvin Gaye’s Estate won a lawsuit against Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams for the hit song “Blurred Lines,” which had a similar feel to one of his songs.

Bullfighting: Art or Not?

Bullfighting has been a prominent cultural and artistic event for centuries, but in recent decades it has faced increasing criticism for animal rights’ abuse.

Buying Green: Consumer Behavior

Do purchasing green products, such as organic foods and electric cars, give consumers the moral license to indulge in unethical behavior?

Cadavers in Car Safety Research

Engineers at Heidelberg University insist that the use of human cadavers in car safety research is ethical because their research can save lives.

Cardinals’ Computer Hacking

St. Louis Cardinals scouting director Chris Correa hacked into the Houston Astros’ webmail system, leading to legal repercussions and a lifetime ban from MLB.

Cheating: Atlanta’s School Scandal

Teachers and administrators at Parks Middle School adjust struggling students’ test scores in an effort to save their school from closure.

Cheating: Sign-Stealing in MLB

The Houston Astros’ sign-stealing scheme rocked the baseball world, leading to a game-changing MLB investigation and fallout.

Cheating: UNC’s Academic Fraud

UNC’s academic fraud scandal uncovered an 18-year scheme of unchecked coursework and fraudulent classes that enabled student-athletes to play sports.

Cheney v. U.S. District Court

A controversial case focuses on Justice Scalia’s personal friendship with Vice President Cheney and the possible conflict of interest it poses to the case.

Christina Fallin: “Appropriate Culturation?”

After Fallin posted a picture of herself wearing a Plain’s headdress on social media, uproar emerged over cultural appropriation and Fallin’s intentions.

Climate Change & the Paris Deal

While climate change poses many abstract problems, the actions (or inactions) of today’s populations will have tangible effects on future generations.

Cover-Up on Campus

While the Baylor University football team was winning on the field, university officials failed to take action when allegations of sexual assault by student athletes emerged.

Covering Female Athletes

Sports Illustrated stirs controversy when their cover photo of an Olympic skier seems to focus more on her physical appearance than her athletic abilities.

Covering Yourself? Journalists and the Bowl Championship

Can news outlets covering the Bowl Championship Series fairly report sports news if their own polls were used to create the news?

Cyber Harassment

After a student defames a middle school teacher on social media, the teacher confronts the student in class and posts a video of the confrontation online.

Defending Freedom of Tweets?

Running back Rashard Mendenhall receives backlash from fans after criticizing the celebration of the assassination of Osama Bin Laden in a tweet.

Dennis Kozlowski: Living Large

Dennis Kozlowski was an effective leader for Tyco in his first few years as CEO, but eventually faced criminal charges over his use of company assets.

Digital Downloads

File-sharing program Napster sparked debate over the legal and ethical dimensions of downloading unauthorized copies of copyrighted music.

Dr. V’s Magical Putter

Journalist Caleb Hannan outed Dr. V as a trans woman, sparking debate over the ethics of Hannan’s reporting, as well its role in Dr. V’s suicide.

East Germany’s Doping Machine

From 1968 to the late 1980s, East Germany (GDR) doped some 9,000 athletes to gain success in international athletic competitions despite being aware of the unfortunate side effects.

Ebola & American Intervention

Did the dispatch of U.S. military units to Liberia to aid in humanitarian relief during the Ebola epidemic help or hinder the process?

Edward Snowden: Traitor or Hero?

Was Edward Snowden’s release of confidential government documents ethically justifiable?

Ethical Pitfalls in Action

Why do good people do bad things? Behavioral ethics is the science of moral decision-making, which explores why and how people make the ethical (and unethical) decisions that they do.

Ethical Use of Home DNA Testing

The rising popularity of at-home DNA testing kits raises questions about privacy and consumer rights.

Flying the Confederate Flag

A heated debate ensues over whether or not the Confederate flag should be removed from the South Carolina State House grounds.

Freedom of Speech on Campus

In the wake of racially motivated offenses, student protests sparked debate over the roles of free speech, deliberation, and tolerance on campus.

Freedom vs. Duty in Clinical Social Work

What should social workers do when their personal values come in conflict with the clients they are meant to serve?

Full Disclosure: Manipulating Donors

When an intern witnesses a donor making a large gift to a non-profit organization under misleading circumstances, she struggles with what to do.

Gaming the System: The VA Scandal

The Veterans Administration’s incentives were meant to spur more efficient and productive healthcare, but not all administrators complied as intended.

German Police Battalion 101

During the Holocaust, ordinary Germans became willing killers even though they could have opted out from murdering their Jewish neighbors.

Head Injuries & American Football

Many studies have linked traumatic brain injuries and related conditions to American football, creating controversy around the safety of the sport.

Head Injuries & the NFL

American football is a rough and dangerous game and its impact on the players’ brain health has sparked a hotly contested debate.

Healthcare Obligations: Personal vs. Institutional

A medical doctor must make a difficult decision when informing patients of the effectiveness of flu shots while upholding institutional recommendations.

High Stakes Testing

In the wake of the No Child Left Behind Act, parents, teachers, and school administrators take different positions on how to assess student achievement.

In-FUR-mercials: Advertising & Adoption

When the Lied Animal Shelter faces a spike in animal intake, an advertising agency uses its moral imagination to increase pet adoptions.

Krogh & the Watergate Scandal

Egil Krogh was a young lawyer working for the Nixon Administration whose ethics faded from view when asked to play a part in the Watergate break-in.

Limbaugh on Drug Addiction

Radio talk show host Rush Limbaugh argued that drug abuse was a choice, not a disease. He later became addicted to painkillers.

U.S. Olympic swimmer Ryan Lochte’s “over-exaggeration” of an incident at the 2016 Rio Olympics led to very real consequences.

Meet Me at Starbucks

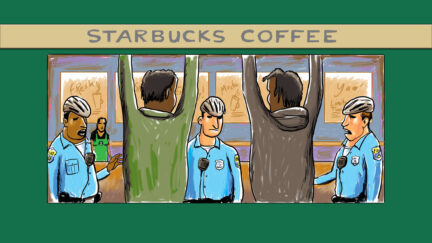

Two black men were arrested after an employee called the police on them, prompting Starbucks to implement “racial-bias” training across all its stores.

Myanmar Amber

Buying amber could potentially fund an ethnic civil war, but refraining allows collectors to acquire important specimens that could be used for research.

Negotiating Bankruptcy

Bankruptcy lawyer Gellene successfully represented a mining company during a major reorganization, but failed to disclose potential conflicts of interest.

Pao & Gender Bias

Ellen Pao stirred debate in the venture capital and tech industries when she filed a lawsuit against her employer on grounds of gender discrimination.

Pardoning Nixon

One month after Richard Nixon resigned from the presidency, Gerald Ford made the controversial decision to issue Nixon a full pardon.

Patient Autonomy & Informed Consent

Nursing staff and family members struggle with informed consent when taking care of a patient who has been deemed legally incompetent.

Prenatal Diagnosis & Parental Choice

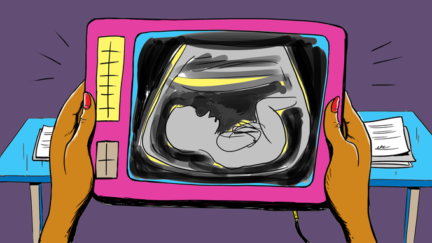

Debate has emerged over the ethics of prenatal diagnosis and reproductive freedom in instances where testing has revealed genetic abnormalities.

Reporting on Robin Williams

After Robin Williams took his own life, news media covered the story in great detail, leading many to argue that such reporting violated the family’s privacy.

Responding to Child Migration

An influx of children migrants posed logistical and ethical dilemmas for U.S. authorities while intensifying ongoing debate about immigration.

Retracting Research: The Case of Chandok v. Klessig

A researcher makes the difficult decision to retract a published, peer-reviewed article after the original research results cannot be reproduced.

Sacking Social Media in College Sports

In the wake of questionable social media use by college athletes, the head coach at University of South Carolina bans his players from using Twitter.

Selling Enron

Following the deregulation of electricity markets in California, private energy company Enron profited greatly, but at a dire cost.

Snyder v. Phelps

Freedom of speech was put on trial in a case involving the Westboro Baptist Church and their protesting at the funeral of U.S. Marine Matthew Snyder.

Something Fishy at the Paralympics

Rampant cheating has plagued the Paralympics over the years, compromising the credibility and sportsmanship of Paralympian athletes.

Sports Blogs: The Wild West of Sports Journalism?

Deadspin pays an anonymous source for information related to NFL star Brett Favre, sparking debate over the ethics of “checkbook journalism.”

Stangl & the Holocaust

Franz Stangl was the most effective Nazi administrator in Poland, killing nearly one million Jews at Treblinka, but he claimed he was simply following orders.

Teaching Blackface: A Lesson on Stereotypes

A teacher was put on leave for showing a blackface video during a lesson on racial segregation, sparking discussion over how to teach about stereotypes.

The Astros’ Sign-Stealing Scandal

The Houston Astros rode a wave of success, culminating in a World Series win, but it all came crashing down when their sign-stealing scheme was revealed.

The Central Park Five

Despite the indisputable and overwhelming evidence of the innocence of the Central Park Five, some involved in the case refuse to believe it.

The CIA Leak

Legal and political fallout follows from the leak of classified information that led to the identification of CIA agent Valerie Plame.

The Collapse of Barings Bank

When faced with growing losses, investment banker Nick Leeson took big risks in an attempt to get out from under the losses. He lost.

The Costco Model

How can companies promote positive treatment of employees and benefit from leading with the best practices? Costco offers a model.

The FBI & Apple Security vs. Privacy

How can tech companies and government organizations strike a balance between maintaining national security and protecting user privacy?

The Miss Saigon Controversy

When a white actor was cast for the half-French, half-Vietnamese character in the Broadway production of Miss Saigon , debate ensued.

The Sandusky Scandal

Following the conviction of assistant coach Jerry Sandusky for sexual abuse, debate continues on how much university officials and head coach Joe Paterno knew of the crimes.

The Varsity Blues Scandal

A college admissions prep advisor told wealthy parents that while there were front doors into universities and back doors, he had created a side door that was worth exploring.

Providing radiation therapy to cancer patients, Therac-25 had malfunctions that resulted in 6 deaths. Who is accountable when technology causes harm?

Welfare Reform

The Welfare Reform Act changed how welfare operated, intensifying debate over the government’s role in supporting the poor through direct aid.

Wells Fargo and Moral Emotions

In a settlement with regulators, Wells Fargo Bank admitted that it had created as many as two million accounts for customers without their permission.

Stay Informed

Support our work.

Digital Platforms and Journalistic Careers: A Case Study of Substack Newsletters

Table of Contents

Executive summary.

In 2018, the technology reporter Taylor Lorenz predicted journalists would adopt influencer tactics to grow their own audiences and directly distribute content to their followers. Since then, journalists have continued to experiment with using digital platforms as part of their career activities. These digital tools provide journalists with the opportunity to capitalize on and monetize their personal brands and skills. In 2020, Lorenz followed up her prediction, anticipating that we will now begin to see “the dark side of this movement.” While independence provides journalists with new career opportunities, it also presents challenges as they risk burnout, precarity, audience pressures, and backlash for their independent work.

The media is often studied as either institutional news work or social media activity. However, on digital platforms journalists increasingly blur the lines between personal and professional, institutional and independent, and reporting and commentary. Opportunities to monetize online content, connect with new audiences, and pursue creative and multimedia projects expand the ways in which journalists can piece together their careers.

Thus, questions arise about how journalists structure and conceptualize their work when working on digital platforms. Why and how do journalists use these tools? What do journalists see as the tools’ strengths and weaknesses, and how do they fit into the broader media ecosystem? In what ways do they complement or contradict journalistic norms and standards?

This report draws on a case study of journalists who use the digital newsletter platform Substack to understand how such platforms affect their work, careers, and identities. Through a combination of computational and qualitative methods, I seek to understand who uses Substack, why journalists use the platform, how they use it, and how Substack relates to the broader media ecosystem.

I identify three dominant themes that explain how journalists use and interpret Substack. Each theme carries implications for how journalists structure their careers, produce media content, and conceptualize their identity.

- Journalists who view newsletters as a career resource use Substack to enhance their work within the traditional legacy media industry. They use their newsletters to create a persona as an expert on a niche topic, publicize their work, practice professional skills, and build a loyal audience in hopes of achieving career advancements. Most in this group tend to offer their newsletters for free; however, some who view themselves as experts in the topics on which they write charge a subscription fee. They seek to continue to uphold journalistic norms of objectivity, fairness, and balance even when embracing the freedom of work on digital platforms. In this way, these writers rely on ties with institutional media outlets to which they seek to link their careers. Strong ties to the media industry and value of journalistic norms strengthen their identification as journalists as a core aspect of their sense of self.

- Alternatively, some pursue newsletters as an alternative media model . These journalists critique dominant media outlets, highlighting experiences of precarity, inefficiencies, and the ways in which norms of objectivity exclude personalized forms of information production and audience engagement. Within their newsletters, these writers strive to produce alternative stories that they feel dominant media institutions do not support or incentivize. Paid subscription models offer a new funding stream that grants writers independence to capitalize on their positionality and personal experiences as a legitimate source of content production. Thus, these journalists express broadened conceptions of their professional identity defined by innate qualities and skills as they seek to build careers unconstrained by institutional norms and barriers.

- Finally, a third subset of journalists define their newsletters as a lifeboat . For these journalists, newsletters serve as stopgaps when they lack other career opportunities and resources. These journalists are critical of the economic feasibility, informational quality, and role of technology companies in newsletter media models. In this way, they remain skeptical of Substack and do not plan to use the platform for a prolonged period. Feelings of hopelessness with the media industry led these writers to distance themselves from their professional identity as journalists.

These three themes illustrate how digital tools expand the ways in which journalists pursue careers and conceptualize their work. By highlighting the multiple ways in which a digital platform affects the careers and structure of journalism, the report emphasizes the ambiguous implications of technological change, rather than representing it as predetermining changes or affecting those who use digital tools all in the same way. 1 Lee, Kevin Woojin, and Elizabeth Anne Watkins, “From Performativity to Performances: Reconsidering Platforms’ Production of the Future of Work, Organizing, and Society.” Sociologica 14(3), 205-15. https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.1971-8853/11673 The report concludes with a discussion of the implications of the diverse uses of digital platforms for journalists on the trustworthiness and consistency of information in the public sphere.

Introduction

Ben started writing about hip-hop as a freelance journalist in 2014. He gradually built up connections with major outlets, producing articles picked up by business and culture magazines. However, Ben felt dissatisfied by the transactional nature of his work. “It didn’t really feel like I was making a true impact beyond getting an occasional check,” he explains. Ben wanted to make more of an impact with his writing. He wanted to build a relationship with his readers, rather than “writing for the editors” to make a living.

In 2017, Ben started an email newsletter focused on the artists, producers, and fans innovating the business of hip-hop. The newsletter allowed him to build an ongoing and direct relationship with his readers and capitalize on his expertise in his niche topic.

He describes his motivation to start the newsletter:

It was the opportunity to take advantage of the changing landscape in digital media, but also have an opportunity to elevate and have a proper home for the type of things that I was writing.… I saw what a few other early writers were doing in this space, where they were taking advantage of the tools and the platforms to create a home for their writing, and in many ways, being able to build a sustainable career and enterprise off that. It was taking advantage of the niche economics that I think are possible with the internet today, where because of how cheap it can be to get something started, you don’t necessarily need to have a vast user base. You can have a publication that appeals to a pretty small base, but a passionate base of readers, and then just build a business model around that.

Ben’s newsletter has grown into his full-time occupation, with more than ten thousand paying subscribers. He expresses pride in the entrepreneurialism of his pursuits and hopes to see “more independent media own their particular niches,” through which writers can “succeed to do what they want to do full-time.”

Ben’s story exemplifies how digital technologies are creating opportunities for journalists and information producers to structure their careers to produce and distribute content in new ways. Traditionally, dominant professional institutions—most notably legacy media publications and more recently digital news outlets—structured journalistic norms and dictated career success. These institutions served as gatekeepers that enabled insular professional groups to maintain control over the production and distribution of legitimate knowledge and information. 2 Karin Wahl-Jorgensen and Thomas Hanitzsch, eds., The Handbook of Journalism Studies, International Communication Association (ICA) Handbook Series (New York: Routledge, 2009). They promoted techniques, such as the norms of reporting, sourcing, and fact-checking, as methods of producing “objective” information. 3 Michael Schudson, Discovering the News (New York: Basic Books, 1981). Additionally, through the creation of explicitly professional spaces and publications, they intended to separate journalists’ professional roles as revealers or communicators of external facts from their private roles as subjective individuals with their own worldviews and values.

In contemporary media work, digital technologies and online platforms allow journalists to use a variety of tools to produce and distribute content. Digital tools offer journalists new opportunities and constraints. Online platforms challenge the clear boundaries between professional and personal forms of content production. 4 Erin Reid and Lakshmi Ramarajan, “Seeking Purity, Avoiding Pollution: Strategies for Moral Career Building,” Organization Science, November 24, 2021, orsc.2021.1514, https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2021.1514. Furthermore, digital platforms, direct distribution channels, and diverse forms of information communication—podcasts, liveblogs, newsletters, etc.—blur the line between professional journalism and the increase of other types of digital creatives and content producers. 5 Emily Bell and Taylor Owen, “The Platform Press: How Silicon Valley reengineered journalism” (Columbia Journalism Review, 2017). Digital tools thus require journalists to combine networks and strategies from professional journalism with entrepreneurship, microcelebrity, influencer culture, research, and academia. Additionally, digitization creates new incentives for news work and ways of defining success, including a focus on audience engagement, circulation metrics, and digital attention. 6 Angele Christin, Metrics at Work (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2020); Caitlin Petre, “The Traffic Factories: Metrics at Chartbeat, Gawker Media, and The New York Times,” Tow Center for Digital Journalism. A Tow/Knight Report (Columbia School of Journalism, 2015); Rebecca Jablonsky, Tero Karppi, and Nick Seaver, “Introduction: Shifting Attention,” Science, Technology, & Human Values, November 22, 2021, 016224392110588, https://doi.org/10.1177/01622439211058823. Last, as journalists engage in independent forms of online content production, technology companies serve an increasingly central role in structuring how journalists produce—and audiences access—news and information. 7 Matt Carlson, “Automating Judgment? Algorithmic Judgment, News Knowledge, and Journalistic Professionalism,” New Media, 2017, 18. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1461444817706684

Simultaneously, journalists face challenges in legacy media work due to increasing employment precarity and distrust of mainstream institutions. Dominant media outlets increasingly favor part-time, contingent, or contract-based work. 8 Chadha, Kalyani, and Linda Steiner, eds. Newswork and Precarity. London; New York: Routledge, 2022.; Cohen, Nicole S. “Entrepreneurial Journalism and the Precarious State of Media Work.” South Atlantic Quarterly 114, no. 3 (July 2015): 513–33.; Vallas, Steven P., and Angèle Christin. “Work and Identity in an Era of Precarious Employment: How Workers Respond to ‘Personal Branding’ Discourse.” Work and Occupations 45, no. 1 (February 2018): 3–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888417735662 In 2021, the Pew Research Center reported that newsroom employment has fallen 26 percent since 2008. 9 Mason Walker, “U.S. newsroom employment has fallen 26% since 2008,” Pew Research Center , July 23, 2021/. Employment precarity incentivizes or necessitates journalists to seek alternative career opportunities, such as using digital platforms. Additionally, Americans remain skeptical about journalists’ and media companies’ ability to communicate quality information. The percentage of Americans who say they have a great deal or a fair amount of trust in the mass mainstream media fell from 53 percent to 40 percent between 2002 and 2020, according to a Gallup poll. 10 Megan Brenan, “Americans Remain Distrustful of Mass Media,” Gallup.com, September 30, 2020. That distrust contributes to news consumers seeking alternative sources of content outside of standard outlets and publications.

This report focuses on journalists who write independent email newsletters on Substack within the context of the changing status and role of legacy and digital news work. I draw on fifty-two interviews with journalists who write email newsletters to offer a content analysis of their professional backgrounds and newsletter texts. I focus on how the prevalence of platform technologies and the changing role of media institutions affect the ways in which journalists navigate career opportunities, conceptualize their goals, produce content for their audiences, and define their professional identities. This includes understanding journalists’ motivation for working on digital platforms: how they distinguish career transition points and define success, produce content, perceive their audience and networks, and incorporate digital tools into their careers.

The report proceeds in three additional sections. In section one, I describe the Substack case study and outline my research methodology. Section two presents the findings of the report in two subsections. First, I use computational data to explore newsletter writers on the platform and the network structure of newsletter content. I then use my core findings to draw on qualitative data to discuss three dominant themes that emerged from my interviews and explain how interviewees use and understand Substack: using newsletters as a (i) career resource, (ii) alternative media model, or (iii) lifeboat. Each of these themes relates to distinct goals, strategies for content production, and conceptions of professional identity. Finally, the report concludes with a discussion about how the varied ways in which journalists approach and interpret newsletter production relate to phenomena such as the crises of expertise, informational distrust, and post-truth politics.

Case Study and Method

This report focuses on journalists who use or have used the newsletter platform Substack. Focusing on a single platform allows comparisons of how journalists use the same digital tool.

Substack started in 2017 as an alternative media space in reaction to critiques of institutional and social media production. The company provides the infrastructure to write and distribute digital newsletters, giving creators control over their email subscription lists, archives, and intellectual property. Substack also focuses on writing as the main output versus requiring other technical or digital skills. The company targets journalists, writers, experts, and visual-content creators geared toward discursive output, although it has been expanding its focus and functionality. Journalists who use Substack largely do so for the purpose of sharing and producing textual information.

Substack was created by media insiders with the goal of using technology and entrepreneurship to help independent writers make a living by providing a direct distribution and subscription product. In doing so, Substack seeks to present an alternative to ad-supported media. The company contrasts its platform with those of advertisement-based media models that offer incentives toward shallow “clickbait” and “fake news.” Instead, Substack frames itself as a resource for free speech, “democratizing” discourse and producing “personal” and “trustworthy” content. Substack describes itself as a “platform” that “enables” content without dictating it, in contrast to a “publisher” that maintains content moderation discretion. However, the company has attracted controversy due to questions about content moderation and responsibility and accountability for discourse that is produced and distributed using the platform. 11 Pompeo, Joe. “‘There Has to Be a Line’: Substack’s Founders Dive Headfirst Into the Culture Wars.” Vanity Fair, May 23, 2022; Navlakha, Meera. “Why Substack Creators Are Leaving the Platform, Again.” Mashable, March 9, 2022; Schulz, Jacob. “Substack’s Curious Views on Content Moderation.” Lawfare, January 4, 2021. In response to criticism over free speech and writer precarity, the company has added new features for its users, such as access to legal advice, writer office hours, and community-building resources.

As of 2021, Substack reported millions of users and more than a million paying subscribers. 12 Tiffany Hsu, “Substack’s Growth Spurt Brings Growing Pains,” The New York Times, April 13, 2022. Its top ten writers reportedly earn more than $7 million in annual revenue. The company is a venture-backed startup. Additionally, the company typically takes 10 percent of paid subscription fees, which range from approximately $5 to $50 per month but are not required. The most popular writers on Substack can make six-figure salaries and more yearly income than in standard media jobs; however, some writers often do not consider newsletter writing as a form of full-time work and thus may balance it with other professional commitments. 13 Chang, Clio. “The Substackerati.” Columbia Journalism Review, Winter 2020. Given its semiprofessional nature, Substack provides an ideal case study to understand how new career resources offered on digital platforms affect the goals, strategies, and identities of journalists.

The report includes computational and qualitative data to assess journalists on Substack. Computational data include large-scale queries of information drawn directly from the platform, such as writer topics, professional backgrounds, and network patterns. These data provide an overview of who uses the platform and the subjects they cover to help inform the subsequent thematic analysis.

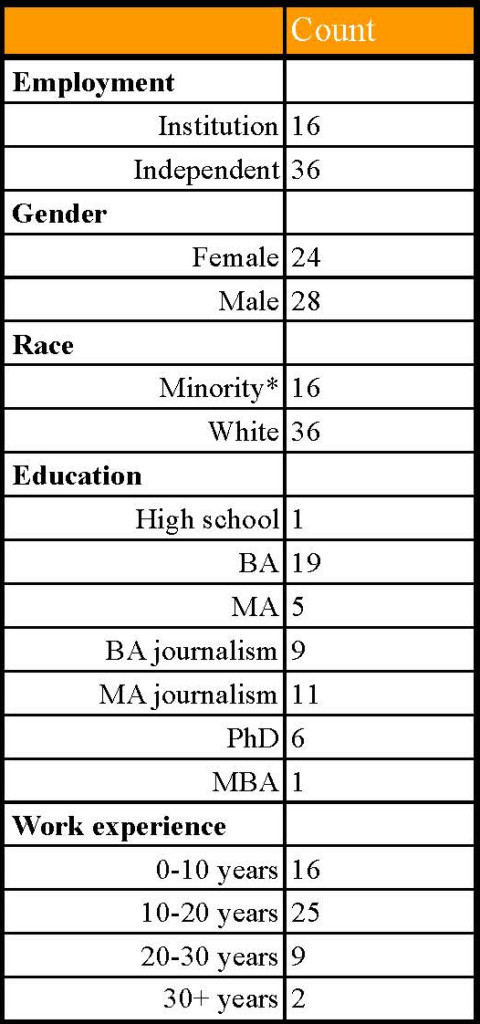

The report’s core findings are based on qualitative data from interviews with fifty-two journalists who write digital newsletters; analysis of their newsletter content, particularly About pages and initial posts that describe their newsletter’s content, purpose, and structure; and online information on their professional background, such as their LinkedIn page, Muck Rack profile, or personal website. Interview subjects were recruited from multiple points of contact to reflect a range of journalists using the platform. (See appendix A for descriptive statistics.) 14 The sample includes six writers who used Substack but switched to producing a digital newsletter on another platform. There was no discernible difference between the justifications for and use of Substack in this subset of interviewees and the larger sample.

Initial respondents were identified using searches on Google and Substack. Additional respondents were recruited using snowball sampling. Respondents were identified as journalists based on how they self-describe in their newsletter profile, or by using information about their broader professional background available online. The sample captures journalists with a variety of careers that include both independent and institutional forms of work. 15 Media ecosystems have also been shown to have a relationship to partisan identity (see Benkler, Faris, and Roberts 2018; Hemmer 2016; Lemieux and Schmalzbauer 2000; Nadler, Bauer, and Konieczna 2020). The study includes participants with a range of political viewpoints, but did not create a representative sample based on partisanship.

Professionals most strongly associated with institutions are employed by a news media company and receive a sustainable salary from their place of employment. In contrast, independent workers take on freelance work with no primary employer and/or self-describe as “independent.” Interview questions were focused on the subject’s professional life, including how they go about their work, balance professional opportunities, and describe their goals and objectives. The research uses qualitative data to illuminate the ways in which digital platforms affect the practices and understandings of journalists, but does not provide a representative or generalizable sample. Textual data, including the About pages of each newsletter and the LinkedIn, Muck Rack, or personal website of interview respondents, supplement interview data to understand respondents’ backgrounds and trajectories. Conclusions are based on how interviewees describe the goals, content, and motivations for their newsletter connected to the structure of their careers and professional identities.

The findings proceed in two subsections. First, the report draws on computational data to generate a layout of the Substack platform. The computational data provide a map of what topics newsletter writers focus on, what types of writers use the tool, and how their newsletters fit within the broader media landscape. The report then draws on qualitative interview and content analysis data focused specifically on how and why these journalists use Substack.

A Computational Layout: Writers on Substack

Using computational methods, a co-researcher, Nick Hagar, and I explore the types of writers and content available on Substack. 16 I would like to thank Nick Hagar for his assistance with computational models and analysis. Substack maintains a discovery feature that sorts newsletters by category. When this research was collected in 2021, it maintained nineteen topical categories and has since added six more. Using the search feature, we approximated the landscape of the most active newsletters on the platform and their categorical labels. 17 The newsletters that are not captured by category search appear far less active: a median of 7 total newsletter posts for general search results, compared with 42 for category search results. Newsletters sorted by category posted a median of 3 days ago, whereas in the general search sample newsletters posted a median of 58 days ago. Thus, Substack’s taxonomy offers a good representation of active newsletters on the platform. Augmenting this approach with other search functions returns small and abandoned newsletters.

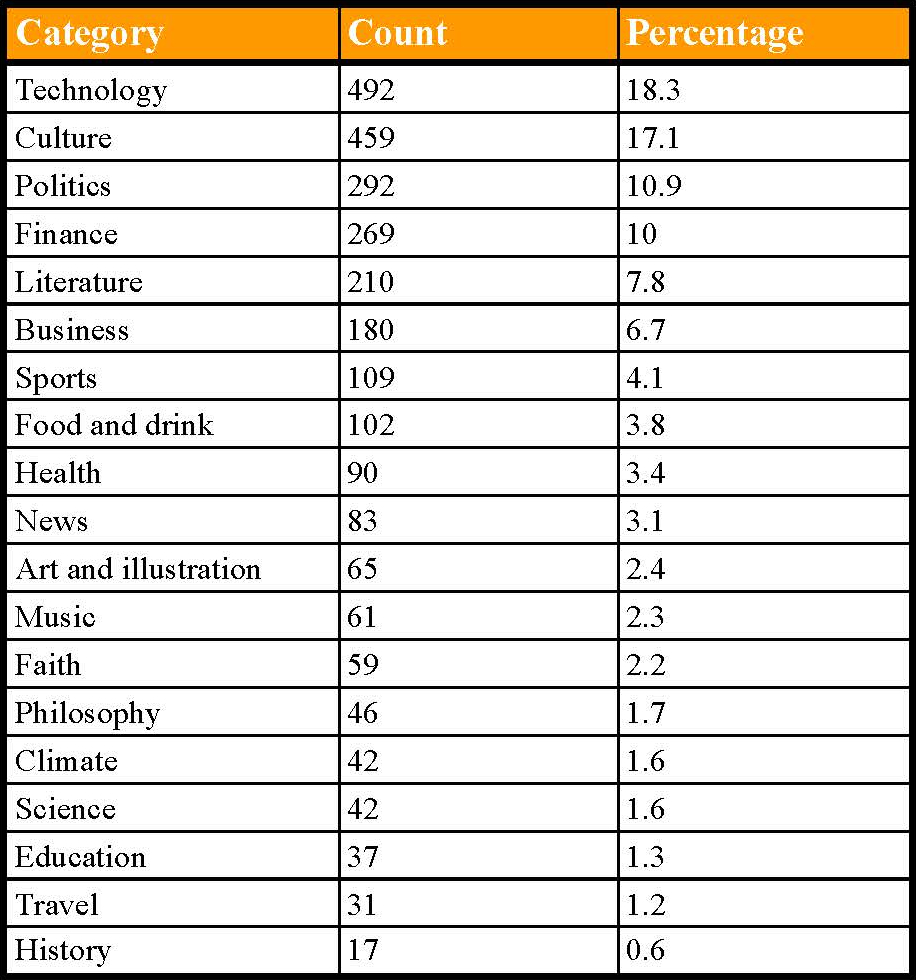

Table 1 provides an overview of how many active newsletters appear within each category through the Substack search function. At the time of our research our analysis identified 2,686 unique active newsletters, a breakdown of which is presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Active newsletters by category. Percentages are rounded to one-tenth of a percent.

Unsurprisingly, most Substack newsletters focus on broad and standard categories of media production, such as culture and politics. After 2021, the introduction of new categories of music, comics, crypto, parenting, fiction, and podcasts shows that niche sections of the platform are growing. Additionally, the prevalence of technology as the most active category points to the types of stories and topics most accessible as an independent media source. Writing about technology needs only a computer and internet connection, meaning it requires fewer resources than field reporting. Later in the report, journalists discuss their ability to establish their expertise writing about digital media, making it a lucrative category for newsletter production.

We manually classified the 2,686 active newsletters to understand the professional background of the authors on the platform. Information on authors’ professional background was gleaned from writer biographies, as well as general information available on the Web.

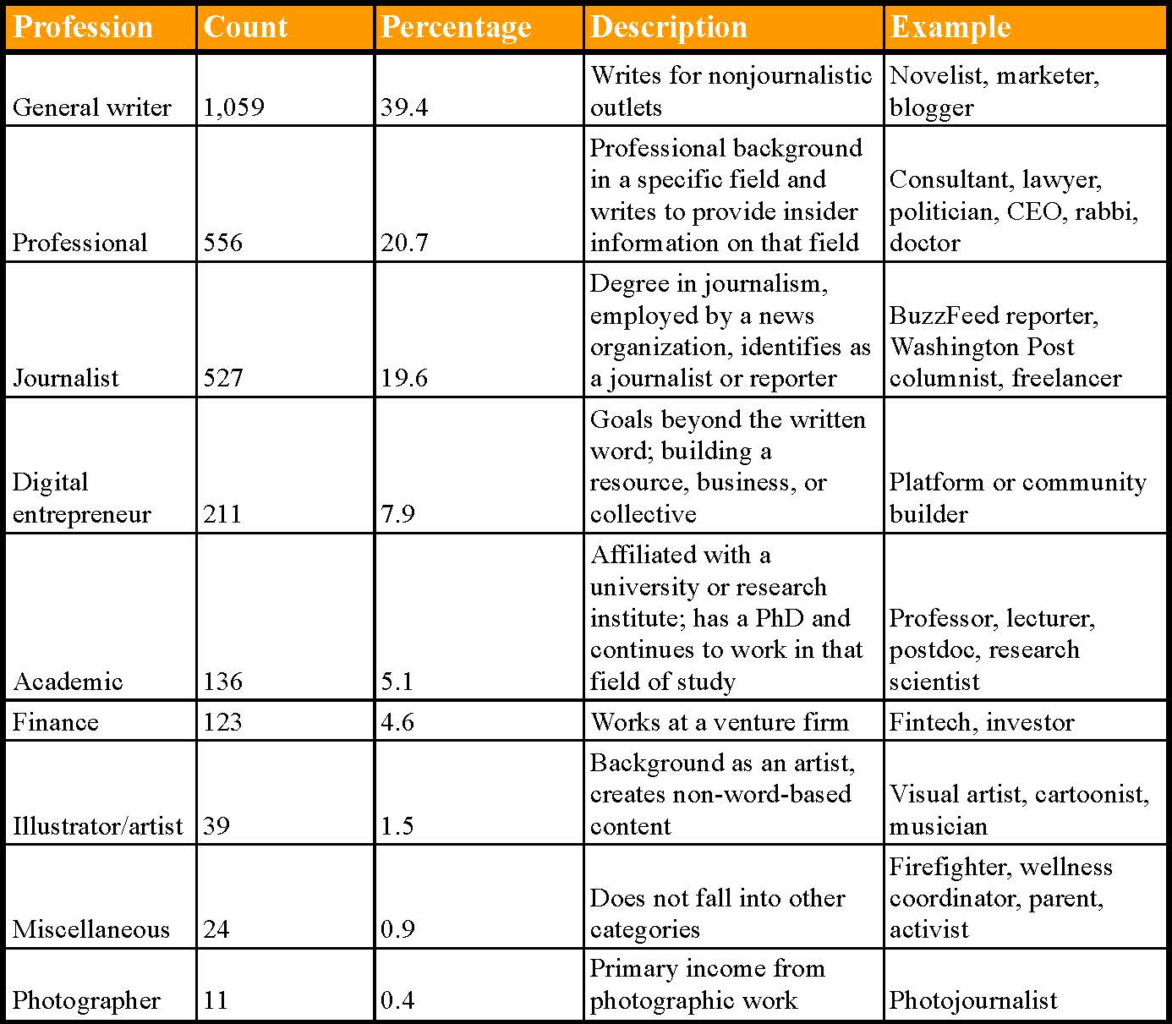

Table 2 represents the background classifications based on the nine most common professional backgrounds found on Substack.

Table 2: Substack user professional backgrounds. Percentages are rounded to nearest one-tenth of a percent.

Once again unsurprisingly, writers and discursive content creators made up most newsletter producers, as well as professionals who use newsletters to capitalize on and share specific expertise. The data suggest that journalists account for about 20 percent of content producers on Substack.

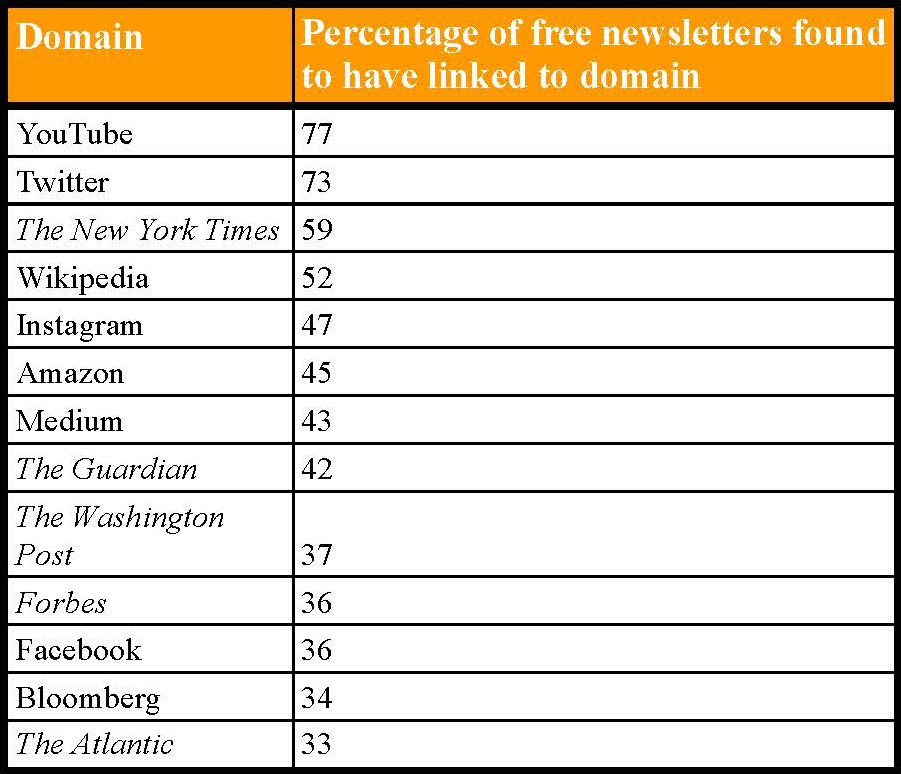

Last, we looked at the relationship between newsletters and other forms of media by comparing hyperlinking citation patterns. We include newsletters that published more than one public post between 2020 and 2021, published posts at a cadence of at least one every thirty days, and published at least one post that included a hyperlink to another webpage (all newsletters in our sample met these criteria). We were only able to access free posts, so our sample does not include paywalled content. This produced a sample of approximately 1.1 million hyperlinks across 139,353 posts from 2,553 active newsletters.

The results show that writers most commonly cite major media and platform domains such as Twitter, YouTube, and t he New York Times (Table 3). For example, 77 percent of newsletter writers in the sample have linked to YouTube, and 5 percent of writers have linked to t he New York Times . Furthermore, while there is large overlap in linking domains, at most, the same unique URL appears in only 2 percent of newsletters. The infrequency with which newsletters link to one another or to the same news story highlights the siloed nature of newsletter production on Substack. Rather than structurally representing an alternative media environment, writers arguably show a strong reliance on institutional news and established platforms.

Hyperlinking patterns in newsletters match the broader structure of digital attention and influence on the Web, relying on common platforms and domains that are viewed as legitimate, relevant, and likely to generate attention. 18 Lasorsa, Dominic L., Seth C. Lewis, and Avery E. Holton. “Normalizing Twitter: Journalism Practice in an Emerging Communication Space.” Journalism Studies 13, no. 1 (February 2012): 19–36, https://hdl.handle.net/11299/123293; Messner, Marcus, and Marcia Watson Distaso. “The Source Cycle: How Traditional Media and Weblogs Use Each Other as Sources.” Journalism Studies 9, no. 3 (June 2008): 447–63, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259563188_The_source_cycle_How_traditional_media_and_weblogs_use_each_other_as_sources; Noam, Eli M. Media Ownership and Concentration in America. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2009; Usher, Nikki, and Yee Man Margaret Ng. “Sharing Knowledge and ‘Microbubbles’: Epistemic Communities and Insularity in US Political Journalism.” Social Media + Society 6, no. 2 (April 2020), https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2056305120926639. Thus, these results indicate that newsletters may be framed as an alternative or independent career resource, but are highly referential to and dependent on dominant media and technology platforms and publications. In this way, digital newsletters represent an element of an integrated and interdependent media environment that journalists must navigate to build their careers.

Table 3: Top 12 domain hyperlinks

Journalists’ uses and interpretations of Substack