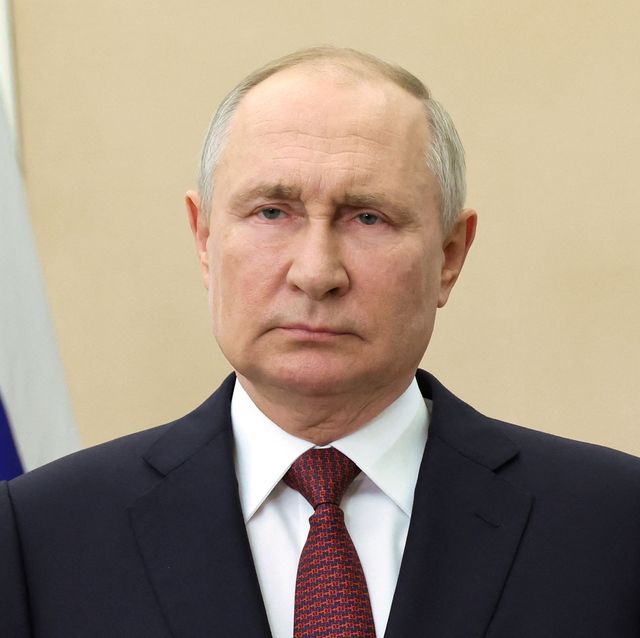

Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Putin served as president of Russia from 2000 to 2008 and was re-elected to the presidency in 2012, where he has stayed ever since. He previously served as Russia's prime minister.

1952-present

Latest News: Vladimir Putin Announces 2024 Russian Presidential Run

According to the Associated Press , the 71-year-old Putin, who was first elected president in March 2000, has twice amended the Russian constitution so that he could theoretically remain in power until 2036. He is already the longest-serving Kremlin leader since Joseph Stalin .

Quick Facts

Early life and political career, president of russia: first and second terms, third term as president, chemical weapons in syria, 2014 winter olympics, invasion into crimea, syrian airstrikes, u.s. election hacks, fourth presidential term, invasion of ukraine, seeking fifth presidential term, personal life, who is vladimir putin.

In 1999, Russian president Boris Yeltsin dismissed his prime minister and promoted former KGB officer Vladimir Putin in his place. In December 1999, Yeltsin resigned, appointing Putin president, and he was re-elected in 2004. In April 2005, he made a historic visit to Israel—the first visit there by any Kremlin leader. Putin could not run for the presidency again in 2008, but was appointed prime minister by his successor, Dmitry Medvedev. Putin was re-elected to the presidency in March 2012 and later won a fourth term. In 2014, he was reportedly nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize.

FULL NAME: Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin BORN: October 7, 1952 BIRTHPLACE: Leningrad (St. Petersburg), Russia SPOUSE: Lyudmila Shkrebneva (1983-2014) CHILDREN: Maria, Yekaterina ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Libra

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin was born in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), Russia, on October 7, 1952. He grew up with his family in a communal apartment, attending the local grammar and high schools, where he developed an interest in sports. After graduating from Leningrad State University with a law degree in 1975, Putin began his career in the KGB as an intelligence officer. Stationed mainly in East Germany, he held that position until 1990, retiring with the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Upon returning to Russia, Putin held an administrative position at the University of Leningrad, and after the fall of communism in 1991, he became an adviser to liberal politician Anatoly Sobchak. When Sobchak was elected mayor of Leningrad later that year, Putin became his head of external relations, and by 1994, Putin had become Sobchak’s first deputy mayor.

After Sobchak’s defeat in 1996, Putin resigned his post and moved to Moscow. There, in 1998, Putin was appointed deputy head of management under Boris Yeltsin’s presidential administration. In that position, he was in charge of the Kremlin's relations with the regional governments.

Shortly afterward, Putin was appointed head of the Federal Security Service, an arm of the former KGB, as well as head of Yeltsin’s Security Council. In August 1999, Yeltsin dismissed his prime minister, Sergey Stapashin, along with his cabinet, and promoted Putin in his place.

In December 1999, Boris Yeltsin resigned as president of Russia and appointed Putin acting president until official elections were held, and in March 2000, Putin was elected to his first term with 53 percent of the vote. Promising both political and economic reforms, Putin set about restructuring the government and launching criminal investigations into the business dealings of high-profile Russian citizens. He also continued Russia's military campaign in Chechnya.

In September 2001, in response to the terrorist attacks on the United States, Putin announced Russia’s support for the U.S. in its anti-terror campaign. However, when the U.S.’s “war on terror” shifted focus to the ousting of Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein , Putin joined German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder and French President Jacques Chirac in opposition of the plan.

In 2004, Putin was re-elected to the presidency, and in April of the following year made a historic visit to Israel for talks with Prime Minister Ariel Sharon—marking the first visit to Israel by any Kremlin leader.

Due to constitutional term limits, Putin was prevented from running for the presidency in 2008. (That same year, presidential terms in Russia were extended from four to six years.) However, when his protégé Dmitry Medvedev succeeded him as president in March 2008, he immediately appointed Putin as Russia’s prime minister, allowing Putin to maintain a primary position of influence for the next four years.

On March 4, 2012, Vladimir Putin was re-elected to his third term as president. After widespread protests and allegations of electoral fraud, he was inaugurated on May 7, 2012, and shortly after taking office appointed Medvedev as prime minister. Once more at the helm, Putin has continued to make controversial changes to Russia’s domestic affairs and foreign policy.

In December 2012, Putin signed into a law a ban on the U.S. adoption of Russian children. According to Putin, the legislation—which took effect on January 1, 2013—aimed to make it easier for Russians to adopt native orphans. However, the adoption ban spurred international controversy, reportedly leaving nearly 50 Russian children—who were in the final phases of adoption with U.S. citizens at the time that Putin signed the law—in legal limbo.

Putin further strained relations with the United States the following year when he granted asylum to Edward Snowden , who is wanted by the United States for leaking classified information from the National Security Agency. In response to Putin's actions, U.S. President Barack Obama canceled a planned meeting with Putin that August.

Around this time, Putin also upset many people with his new anti-gay laws. He made it illegal for gay couples to adopt in Russia and placed a ban on propagandizing “nontraditional” sexual relationships to minors. The legislation led to widespread international protest.

In September 2013, tensions rose between the United States and Syria over Syria’s possession of chemical weapons, with the U.S. threatening military action if the weapons were not relinquished. The immediate crisis was averted, however, when the Russian and U.S. governments brokered a deal whereby those weapons would be destroyed.

On September 11, 2013, The New York Times published an op-ed piece by Putin titled “A Plea for Caution From Russia.” In the article, Putin spoke directly to the U.S.’s position in taking action against Syria, stating that such a unilateral move could result in the escalation of violence and unrest in the Middle East.

Putin further asserted that the U.S. claim that Bashar al-Assad used the chemical weapons on civilians might be misplaced, with the more likely explanation being the unauthorized use of the weapons by Syrian rebels. He closed the piece by welcoming the continuation of an open dialogue between the involved nations to avoid further conflict in the region.

In 2014, Russia hosted the Winter Olympics, which were held in Sochi beginning on February 6. According to NBS Sports, Russia spent roughly $50 billion in preparation for the international event.

However, in response to what many perceived as Russia’s recently passed anti-gay legislation, the threat of international boycotts arose. In October 2013, Putin tried to allay some of these concerns, saying in an interview broadcast on Russian television that, “We will do everything to make sure that athletes, fans and guests feel comfortable at the Olympic Games regardless of their ethnicity, race or sexual orientation.”

In terms of security for the event, Putin implemented new measures aimed at cracking down on Muslim extremists, and in November 2013 reports surfaced that saliva samples had been collected from some Muslim women in the North Caucasus region. The samples were ostensibly to be used to gather DNA profiles, in an effort to combat female suicide bombers known as “black widows.”

Shortly after the conclusion of the 2014 Winter Olympics, amidst widespread political unrest in Ukraine, which resulted in the ousting of President Viktor Yanukovych, Putin sent Russian troops into Crimea, a peninsula in the country’s northeast coast of the Black Sea. The peninsula had been part of Russia until Nikita Khrushchev, former Premier of the Soviet Union, gave it to Ukraine in 1954.

Ukraine’s ambassador to the United Nations, Yuriy Sergeyev, claimed that approximately 16,000 troops invaded the territory, and Russia’s actions caught the attention of several European countries and the United States, who refused to accept the legitimacy of a referendum in which the majority of the Crimean population voted to secede from Ukraine and reunite with Russia.

Putin defended his actions, insisting that the troops sent into Ukraine were only meant to enhance Russia’s military defenses within the country—referring to Russia’s Black Sea Fleet, which has its headquarters in Crimea. He also vehemently denied accusations by other nations, particularly the United States, that Russia intended to engage Ukraine in war.

He went on to claim that although he was granted permission from Russia's upper house of Parliament to use force in Ukraine, he found it unnecessary. Putin also wrote off any speculation that there would be a further incursion into Ukrainian territory, saying, “Such a measure would certainly be the very last resort.”

The following day, it was announced that Putin had been nominated for the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize.

In September 2015, Russia surprised the world by announcing it would begin strategic airstrikes in Syria. Despite government officials’ assertions that the military actions were intended to target the extremist Islamic State, which made significant advances in the region due to the power vacuum created by Syria's ongoing civil war, Russia's true motives were called into question, with many international analysts and government officials claiming that the airstrikes were in fact aimed at the rebel forces attempting to overthrow President Bashar al-Assad's historically repressive regime.

In late October 2017, Putin was personally involved in another alarming form of aerial warfare when he oversaw a late-night military drill that resulted in the launch of four ballistic missiles across the country. The drill came during a period of escalating tensions in the region, with Russian neighbor North Korea also drawing attention for its missile tests and threats to engage the U.S. in destructive conflict.

In December 2017, Putin announced he was ordering Russian forces to begin withdrawing from Syria, saying the country’s two-year campaign to destroy ISIS was complete, though he left open the possibility of returning if terrorist violence resumed in the area. Despite the declaration, Pentagon spokesman Robert Manning was hesitant to endorse that view of events, saying, “Russian comments about removal of their forces do not often correspond with actual troop reductions.”

Months prior to the 2016 U.S. presidential election, multiple U.S. intelligence agencies unilaterally agreed that Russian intelligence was behind the email hacks of the Democratic National Committee (DNC) and John Podesta, who had, at the time, been chairman of Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton’s campaign.

In December 2016 unnamed senior CIA officials further concluded “with a high level of confidence” that Putin was personally involved in intervening in the U.S. presidential election, according to a report by USA Today . The officials further went on to assert that the hacked DNC and Podesta emails that were given to WikiLeaks just before U.S. Election Day were designed to undermine Clinton’s campaign in favor of her Republican opponent, Donald Trump . Soon after, the FBI and National Intelligence Agency publicly supported the CIA’s assessments.

Putin denied any such attempts to disrupt the U.S. election, and despite the assessments of his intelligence agencies, President Trump generally seemed to favor the word of his Russian counterpart. Underscoring their attempts to thaw public relations, the Kremlin in late 2017 revealed that a terror attack had been thwarted in St. Petersburg, thanks to intelligence provided by the CIA.

Around that time, Putin reported at his annual end-of-year press conference that he would seek a new six-year term as president in early 2018 as an independent candidate, signaling he was ending his longtime association with the United Russia party.

Shortly before the first formal summit between Presidents Putin and Trump in July 2018, the U.S. Department of Justice announced the indictments of 12 Russian operatives on charges relating to interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Regardless, Trump suggested he was satisfied with his counterpart’s “strong and powerful" denial in a joint news conference and praised Putin’s offer to submit the 12 indicted agents to questioning with American witnesses present.

In a subsequent interview with Fox News anchor Chris Wallace, Putin seemingly defended the hacking of the DNC server by suggesting that no false information was planted in the process. He also rejected the idea that he had compromising information about Trump, saying that the businessman “was of no interest for us” before announcing his presidential campaign, and notably refused to touch a copy of the indictments offered to him by Wallace.

In March 2018, toward the end of his third term, Putin boasted of new weaponry that would render NATO defenses “completely worthless,” including a low-flying nuclear-capable cruise missile with “unlimited” range and another one capable of traveling at hypersonic speed. His demonstration included video animation of attacks on the United States.

Not long afterward, a two-hour documentary, titled Putin , was posted to several social media pages and a pro-Kremlin YouTube account. Designed to showcase the president in a strong yet humane light, the doc featured Putin sharing the story of how he ordered a hijacked plane shot down to head off a bomb scare at the 2014 Sochi Olympics, as well as recollections of his grandfather's days as a cook for Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin .

On March 18, 2018, the fourth anniversary of the country’s seizure of Crimea, Russian citizens overwhelmingly elected Putin to a fourth presidential term, with 67 percent of the electorate turning out to award him more than 76 percent of the vote. The divided opposition stood little chance against the popular leader, his closest competitor notching around 13 percent of the vote.

Little was expected to change regarding Putin’s strategies for rebuilding the country as a global power, though the start of his final term set off questions about his successor, and whether he would affect constitutional change in an attempt to remain in office indefinitely.

On July 16, 2018, Putin met with President Trump in Helsinki, Finland, for the first formal talks between the two leaders. According to Russia, topics of the meeting included the ongoing war in Syria and “the removal of the concerns” about accusations of Russian attempts to influence the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

The following April, Putin met with North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un for the first time. The two leaders discussed the issue of the North Korean laborers in Russia, while Putin also offered support of his counterpart’s denuclearization negotiations with the U.S., saying Kim would need “security guarantees” in exchange for abandoning his nuclear program.

The topic of whether Putin aimed to extend his hold on power resurfaced following his state-of-the-nation speech in January 2020, which included proposals for constitutional amendments that included transferring the power to select the prime minister and cabinet from the president to the Parliament. The entire cabinet, including Medvedev, promptly resigned, leading to the selection of Mikhail V. Mishustin as the new prime minister.

Despite Putin’s earlier remarks of further incursion into Ukraine being a last resort, in the spring of 2021, Russian military forces began forming near the borders of the neighboring country for what the Kremlin claimed were training exercises. According to Reuters , more than 100,000 troops had deployed by November.

On December 17, Russia released a list of security demands that included NATO pulling back forces and weaponry from its eastern flank and ceasing further expansion, including the possible addition of Ukraine into the alliance. If the demands were not met, a “military response” was promised.

Then on February 24, 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine with missile and rocket strikes on Ukrainian cities and military installations. In a televised address, Putin—claiming that Russian speakers in Ukraine faced genocide—referred to the invasion as a “special military operation,” designed to “achieve the demilitarization and denazification" of the country. In the early hours, Russian forces took Chernobyl, site of the infamous 1986 nuclear disaster, but were held back from the capital city of Kyiv.

As the conflict dragged on with Western allies supporting Ukraine, Putin announced the “special mobilization” of more than 100,000 reserve troops in September 2022.

Ukrainian troops launched a counteroffensive in June 2023 and, as of December, the conflict is still ongoing. The U.S. estimated that August that around 500,000 Russian and Ukrainian soldiers had been wounded or killed.

In December 2023, Putin announced that he would seek a fifth term as president of Russia in the country's upcoming elections in March 2024. With a victory, he would be able to remain in power until at least 2030 and potentially run for another subsequent six-year term.

Putin is not expected to face any serious challengers and remains popular domestically. According to CNBC , a survey by Russian news agency Tass found that more than 78 percent of Russians trust Putin, and more than 75 percent approve of his activities.

In 1980, Putin met his future wife, Lyudmila, who was working as a flight attendant at the time. The couple married in 1983 and had two daughters: Maria, born in 1985, and Yekaterina, born in 1986. In early June 2013, after nearly 30 years of marriage, Russia’s first couple announced that they were getting a divorce, providing little explanation for the decision, but assuring that they came to it mutually and amicably.

“There are people who just cannot put up with it,” Putin stated. “Lyudmila Alexandrovna has stood watch for eight, almost nine years.” Providing more context to the decision, Lyudmila added, “Our marriage is over because we hardly ever see each other. Vladimir Vladimirovich is immersed in his work, our children have grown and are living their own lives.”

An Orthodox Christian, Putin is said to attend church services on important dates and holidays on a regular basis and has had a long history of encouraging the construction and restoration of thousands of churches in the region. He generally aims to unify all faiths under the government’s authority and legally requires religious organizations to register with local officials for approval.

- The path towards a free society has not been simple. There are tragic and glorious pages in our history.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Tyler Piccotti first joined the Biography.com staff as an Associate News Editor in February 2023, and before that worked almost eight years as a newspaper reporter and copy editor. He is a graduate of Syracuse University. When he's not writing and researching his next story, you can find him at the nearest amusement park, catching the latest movie, or cheering on his favorite sports teams.

Famous Political Figures

10 of the First Black Women in Congress

Kamala Harris

Deb Haaland

Why Lewis Strauss Didn’t Like Oppenheimer

Madeleine Albright

These Are the Major 2024 Presidential Candidates

Hillary Clinton

Indira Gandhi

Toussaint L'Ouverture

Kevin McCarthy

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Vladimir Putin

By: History.com Editors

Published: September 25, 2023

Vladimir Putin (1952-) is a former KGB agent who has ruled Russia for more than two decades. Intent on restoring Russian might following the collapse of the Soviet Union , he has launched several military campaigns, including an invasion of Ukraine, and helped usher in what’s often described as a new Cold War . Meanwhile, he has steadily tightened his grip on power, persecuting political opponents, shuttering independent media outlets, and otherwise dismantling the country’s nascent democracy.

Putin's Early Years and Personal Life

Much about Vladimir Putin’s personal life remains murky. Born in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) in 1952, he has recalled growing up modestly in a rat-infested communal apartment building. His parents, who lost two children prior to his birth—one of whom died during the prolonged Nazi siege of Leningrad in World War II —apparently doted on him despite working long hours. As a youth, he practiced martial arts and is reputed to have gotten into many fist fights.

In 1983, Putin married a flight attendant, Lyudmila Shkrebneva, with whom he has two daughters. (The couple divorced around 2013.) He is rumored to have fathered other children as well. Throughout his time in office, Putin has kept his family out of the public eye.

Putin as a KGB Agent

After studying law at Leningrad State University, Putin joined the KGB , the Soviet counterpart of the CIA. In the mid-1980s, he was sent to the city of Dresden in East Germany, where, in his words, he gathered “political intelligence,” in part by recruiting sources. Putin remained in Dresden during the fall of the Berlin Wall , and, with a risky bluff , purportedly prevented a crowd of protestors from storming the local KGB headquarters.

Putin's Political Rise

Putin returned to Leningrad in 1990 and claimed to have resigned from the KGB the following year. The subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union affected him deeply; he later called it the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe” of the 20th century. Around that time, he got his political start as an aide to Anatoly Sobchak , his former teacher who became his mentor and St. Petersburg’s mayor.

In 1996, Sobchak lost his bid for re-election and later fled abroad amid corruption allegations. Yet Putin continued his meteoric rise, moving to Moscow, Russia’s capital, and securing one Kremlin post after another (while also defending an economics dissertation he allegedly plagiarized ). By 1998, Putin led the KGB’s main successor organization, and the following year President Boris Yeltsin named him prime minister, the country’s second-highest office, thereby elevating him from obscurity to heir apparent.

When an ailing and increasingly unpopular Yeltsin resigned on December 31, 1999, Putin took over as acting president. (Months later, he would win election to a full term.) Helped by rising oil and gas prices, the economy improved in the early 2000s and living standards rose. Many Russians saw him as bringing order and stability after the hyperinflation, tumultuousness, and perceived lawlessness of the Yeltsin years.

Putin's Consolidation of Power

In his first address as Russia’s president, Putin promised to protect freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and property rights, and he likewise announced his commitment to democracy. Yet democratic backsliding began almost immediately under his leadership. The Kremlin brought independent television networks under state control and shut down other news outlets; abolished gubernatorial and senatorial elections; curtailed the judiciary; and restricted opposition political parties. When elections took place, outside observers noted widespread voter irregularities. Putin’s system was sometimes referred to as a “managed democracy.”

Because Russia’s constitution barred a third consecutive term, Putin stepped down in 2008, with his longtime confidante Dmitry Medvedev taking over as president. But Putin retained the role of prime minister and left little doubt about who was really in charge. When Medvedev’s term ended in 2012, the two swapped positions, and Putin once again became president. He has occupied the top job ever since, at one point signing a law that allows him to stay in power until 2036.

Putin has habitually placed his friends and old intelligence colleagues in key posts, several of whom became extravagantly wealthy, and he’s propagated a cult of personality. Perceived opponents have been called “scum” and “traitors” and dealt with harshly. Some, like oil tycoon Mikhail Khodorkovsky, have been jailed, whereas others have wound up dead. In 2006, for example, investigative journalist Anna Politkovskaya was gunned down on Putin’s birthday, and that same year Russian defector Alexander Litvinenko was assassinated in England with radioactive polonium.

More recently, opposition leader Aleksei Navalny was banned from running for president, survived an assassination attempt , and was then imprisoned on what’s widely considered to be politically motivated charges. Yet another high-profile death occurred in 2023, when Yevgeny Prigozhin was killed in a plane crash after launching a short-lived mutiny against Russia’s military leadership.

Putin's Relationship with the West

Many Western leaders originally approved of Putin, with U.S. President George W. Bush saying he had “looked the man in the eye,” found him “very straightforward and trustworthy,” and gotten a “sense of his soul.” Putin was the first foreign leader to call Bush following the terrorist attacks of September 11 , 2001. And though he opposed the Iraq War , Putin assisted in aspects of the so-called War on Terror . He moreover described Russia as a “friendly European nation” that desired “stable peace on the continent.”

Putin’s relationship with the West deteriorated, however, in part over NATO ’s 2004 expansion into seven Eastern European countries and over pro-Western revolutions that broke out in Georgia and Ukraine. Putin was furthermore irked by U.S. lobbying to bring Georgia and Ukraine into NATO and by its support for an independent Kosovo. In 2007, he accused the United States of overstepping “its national borders in every way.” Over time, Putin came to think of himself as a protector of traditional Russian values, standing up to a hypocritical and morally decadent West.

In 2014, as tensions escalated over Ukraine, Russia was expelled from the Group of Eight industrialized nations. Around that time, he granted asylum to U.S. whistleblower Edward Snowden . And, according to U.S. intelligence agencies , he interfered in the 2016 U.S. presidential election , greenlighting a computer hacking operation that infiltrated the campaign of Hillary Clinton .

Putin and U.S. President Donald Trump maintained generally friendly ties. But the U.S.-Russian relationship reached arguably its lowest point in decades following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Since then, Russia has been hit with a slew of economic sanctions, Ukraine has received much Western military assistance, and U.S. President Joe Biden has called Putin a “thug,” a “murderous dictator,” and a “war criminal.”

Putin's Wars

During his more than two decades in office, Putin has used the military in increasingly aggressive ways. Early in his tenure, he violently suppressed a separatist movement in the Russian republic of Chechnya. In 2008, he orchestrated a brief but large-scale invasion of Georgia , thus cementing Russian control of the breakaway regions Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Starting in 2015, he intervened in the Syrian civil war , among other things authorizing a prolonged bombardment of the city of Aleppo. Additionally, he has deployed Russian mercenaries in various African countries .

Putin’s most prolonged conflict has taken place in Ukraine . In 2014, when Ukrainian protestors ousted their Russian-backed president, Putin responded by annexing Crimea—which had been gifted from Russia to Ukraine during the Soviet era—and by backing a separatist insurgency in eastern Ukraine. Then, in 2022, he launched an all-out invasion of Ukraine, but failed to take Kiev, the capital. Heavy fighting has since claimed hundreds of thousands of lives . The Russian armed forces have been accused of purposely targeting civilians and committing torture and other atrocities, prompting the International Criminal Court to issue a warrant for Putin’s arrest (though he is unlikely to stand trial).

The Man Without a Face : The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin , by Masha Gessen, published by Riverhead Books, 2012. The Strongman : Vladimir Putin and the Struggle for Russia , by Angus Roxburgh, published by I.B. Tauris, 2012. First Person : An Astonishingly Frank Self-Portrait by Russia’s President Vladimir Putin , 2000. ‘The New Tsar: The Rise and Reign of Vladimir Putin,’ by Steven Lee Myers. The New York Times , November 8, 2015. The Making of Vladimir Putin. The New York Times , March 26, 2022. Putin, Vladimir. Encyclopedia Britannica

HISTORY Vault: Vladimir Putin

A gripping look at Putin's rise from humble beginnings to brutal dictatorship, and his emergence as one of the gravest threats to America's security.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Biography of Vladimir Putin: From KGB Agent to Russian President

- European History Figures & Events

- Wars & Battles

- The Holocaust

- European Revolutions

- Industry and Agriculture History in Europe

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

Early Life, Education, and Career

- Prime Minister 1999

Acting President 1999 to 2000

First presidential term 2000 to 2004, second presidential term 2004 to 2008, second premiership 2008 to 2012.

- Third Presidential Term 2012 to 2018

Fourth Presidential Term 2018

Invasion of ukraine, interference in 2016 us presidential election, personal life, net worth, and religion, notable quotes, sources and references.

- B.S., Texas A&M University

Vladimir Putin is a Russian politician and former KGB intelligence officer currently serving as President of Russia. Elected to his current and fourth presidential term in May 2018, Putin has led the Russian Federation as either its prime minister, acting president, or president since 1999. Long considered an equal of the President of the United States in holding one of the world’s most powerful public offices, Putin has aggressively exerted Russia’s influence and political policy around the world.

Fast Facts: Vladimir Puton

- Full Name: Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin

- Born: October 7, 1952, Leningrad, Soviet Union (now Saint Petersburg, Russia)

- Parents’ Names: Maria Ivanovna Shelomova and Vladimir Spiridonovich Putin

- Spouse: Lyudmila Putina (married in 1983, divorced in 2014)

- Children: Two daughters; Mariya Putina and Yekaterina Putina

- Education: Leningrad State University

- Known for: Russian Prime Minister and Acting President of Russia, 1999 to 2000; President of Russia 2000 to 2008 and 2012 to present; Russian Prime Minister 2008 to 2012.

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin was born on October 7, 1952, in Leningrad, Soviet Union (now Saint Petersburg, Russia). His mother, Maria Ivanovna Shelomova was a factory worker and his father, Vladimir Spiridonovich Putin, had served in the Soviet Navy submarine fleet during World War II and worked as a foreman at an automobile factory during the 1950s. In his official state biography, Putin recalls, “I come from an ordinary family, and this is how I lived for a long time, nearly my whole life. I lived as an average, normal person and I have always maintained that connection.”

While attending elementary and high school, Putin took up judo in hopes of emulating the Soviet intelligence officers he saw in the movies. Today, he holds a black belt in judo and is a national master in the similar Russian martial art of sambo. He also studied German at Saint Petersburg High School, and speaks the language fluently today.

In 1975, Putin earned a law degree from Leningrad State University, where he was tutored and befriended by Anatoly Sobchak, who would later become a political leader during the Glasnost and Perestroika reform period. As a college student, Putin was required to join the Communist Party of the Soviet Union but resigned as a member in December 1991. He would later describe communism as “a blind alley, far away from the mainstream of civilization.”

After initially considering a career in law, Putin was recruited into the KGB (the Committee for State Security) in 1975. He served as a foreign counter-intelligence officer for 15 years, spending the last six in Dresden, East Germany. After leaving the KGB in 1991 with the rank of lieutenant colonel, he returned to Russia where he was in charge of the external affairs of Leningrad State University. It was here that Putin became an advisor to his former tutor Anatoly Sobchak, who had just become Saint Petersburg’s first freely-elected mayor. Gaining a reputation as an effective politician, Putin quickly rose to the position of first deputy mayor of Saint Petersburg in 1994.

Prime Minister 1999

After moving to Moscow in 1996, Putin joined the administrative staff of Russia’s first president Boris Yeltsin . Recognizing Putin as a rising star, Yeltsin appointed him director of the Federal Security Service (FSB)—the post-communism version of the KGB—and secretary of the influential Security Council. On August 9, 1999, Yeltsin appointed him as acting prime minister. On August 16, the Russian Federation’s legislature, the State Duma , voted to confirm Putin’s appointment as prime minister. The day Yeltsin first appointed him, Putin announced his intention to seek the presidency in the 2000 national election.

While he was largely unknown at the time, Putin’s public popularity soared when, as prime minister, he orchestrated a military operation that succeeded resolving the Second Chechen War , an armed conflict in the Russian-held territory of Chechnya between Russian troops and secessionist rebels of the unrecognized Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, fought between August 1999 and April 2009.

When Boris Yeltsin unexpectedly resigned on December 31, 1999, under suspicion of bribery and corruption, the Constitution of Russia made Putin acting President of the Russian Federation. Later the same day, he issued a presidential decree protecting Yeltsin and his relatives from prosecution for any crimes they might have committed.

While the next regular Russian presidential election was scheduled for June 2000, Yeltsin’s resignation made it necessary to hold the election within three months, on March 26, 2000.

At first far behind his opponents, Putin’s law-and-order platform and decisive handling of the Second Chechen War as acting president soon pushed his popularity beyond that of his rivals.

On March 26, 2000, Putin was elected to his first of three terms as President of the Russian Federation winning 53 percent of the vote.

Shortly after his inauguration on May 7, 2000, Putin faced the first challenge to his popularity over claims that he had mishandled his response to the Kursk submarine disaster . He was widely criticized for his refusal to return from vacation and visit the scene for over two weeks. When asked on the Larry King Live television show what had happened to the Kursk, Putin’s two-word reply, “It sank,” was widely criticized for its perceived cynicism in the face of tragedy.

October 23, 2002, as many as 50 armed Chechens, claiming allegiance to the Chechnya Islamist separatist movement, took 850 people hostage in Moscow’s Dubrovka Theater. An estimated 170 people died in the controversial special-forces gas attack that ended the crisis. While the press suggested that Putin’s heavy-handed response to the attack would damage his popularity, polls showed over 85 percent of Russians approved of his actions.

Less than a week after the Dubrovka Theater attack, Putting clamped down even harder on the Chechen separatists, canceling previously announced plans to withdraw 80,000 Russian troops from Chechnya and promising to take “measures adequate to the threat” in response to future terrorist attacks. In November, Putin directed Defense Minister Sergei Ivanov to order sweeping attacks against Chechen separatists throughout the breakaway republic.

Putin’s harsh military policies succeeded in at least stabilizing the situation in Chechnya. In 2003, the Chechen people voted to adopt a new constitution confirming that the Republic of Chechnya would remain a part of Russia while retaining its political autonomy. Though Putin’s actions greatly diminished the Chechen rebel movement, they failed to end the Second Chechen War, and sporadic rebel attacks continued in the northern Caucasus region.

During the majority of his first term, Putin concentrated on improving the failing Russian economy, in part by negotiating a “grand bargain” with the Russian business oligarchs who had controlled the nation’s wealth since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. Under the bargain, the oligarchs would retain most of their power, in return for supporting—and cooperating with—Putin’s government.

According to financial observers at the time, Putin made it clear to the oligarchs that they would prosper if they played by the Kremlin rules. Indeed, Radio Free Europe reported in 2005 that the number of Russian business tycoons had greatly increased during Putin’s time in power, often aided by their personal relationships with him.

Whether Putin’s “grand bargain” with the oligarchs actually “improved” the Russian economy or not remains uncertain. British journalist and expert on international affairs Jonathan Steele has observed that by the end of Putin’s second term in 2008, the economy had stabilized and the nation’s overall standard of living had improved to the point that the Russian people could “notice a difference.”

On March 14, 2004, Putin was easily re-elected to the presidency, this time winning 71 percent of the vote.

During his second term as president, Putin focused on undoing the social and economic damage suffered by the Russian people during the collapse and dissolution of the Soviet Union, an event he called “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the Twentieth Century.” In 2005, he launched the National Priority Projects designed to improve health care, education, housing, and agriculture in Russia.

On October 7, 2006—Putin’s birthday— Anna Politkovskaya, a journalist and human rights activist, who as a frequent critic of Putin and had exposed corruption in the Russian Army and cases of its improper conduct in the Chechnya conflict, was shot to death as she entered the lobby of her apartment building. While Politkovskaya’s killer was never identified, her death brought criticism that Putin’s promise to protect the newly-independent Russian media had been no more than political rhetoric. Putin commented that Politkovskaya’s death had caused him more problems than anything she had ever written about him.

In 2007, Other Russia, a group opposed to Putin led by former world chess champion Garry Kasparov, organized a series of “Dissenters’ Marches” to protest Putin’s policies and practices. Marches in several cities resulted in the arrests of some 150 protestors who tried to penetrate police lines.

In the December 2007 elections, the equivalent of the U.S. mid-term congressional election, Putin’s United Russia party easily retained control of the State Duma, indicating the Russian people’s continued support for him and his policies.

The democratic legitimacy of the election was questioned, however. While some 400 foreign election monitors stationed at polling places stated that the election process itself had not been rigged, the Russian media’s coverage had clearly favored candidates of United Russia. Both the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe and the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe concluded that the elections were unfair and called on the Kremlin to investigate alleged violations. A Kremlin-appointed election commission concluded that not only had the election been fair, but it had also proven the “stability” of the Russian political system.

With Putin barred by the Russian Constitution from seeking a third consecutive presidential term, Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev was elected president. However, on May 8, 2008, the day after Medvedev’s inauguration, Putin was appointed Prime Minister of Russia. Under the Russian system of government, the president and the prime minister share responsibilities as the head of state and head of the government, respectively. Thus, as prime minister, Putin retained his dominance over the country’s political system.

In September 2001, Medvedev proposed to the United Russia Congress in Moscow, that Putin should run for the presidency again in 2012, an offer Putin happily accepted.

Third Presidential Term 2012 to 2018

On March 4, 2012, Putin won the presidency for a third time with 64 percent of the vote. Amid public protests and accusations that he had rigged the election, he was inaugurated on May 7, 2012, immediately appointing former President Medvedev as prime minister. After successfully quelling protests against the election process, often by having marchers jailed, Putin proceeded to make sweeping—if controversial—changes to Russia’s domestic and foreign policy.

In December 2012, Putin signed a law prohibiting the adoption of Russian children by U.S. citizens. Intended to ease the adoption of Russian orphans by Russian citizens, the law stirred international criticism, especially in the United States, where as many as 50 Russian children in the final stages of adoption were left in legal limbo.

The following year, Putin again strained his relationship with the U.S. by granting asylum to Edward Snowden, who remains wanted in the United States for leaking classified information he gathered as a contractor for the National Security Agency on the WikiLeaks website. In response, U.S. President Barack Obama canceled a long-planned August 2013 meeting with Putin.

Also in 2013, Putin issued a set of highly controversial anti-gay laws outlawing gay couples from adopting children in Russia and banning the dissemination of material promoting or describing “nontraditional” sexual relationships to minors. The laws brought worldwide protests from both the LGBT and straight communities.

In December 2017, Putin announced he would seek a six-year—rather than four-year—term as president in July, running this time as an independent candidate, cutting his old ties with the United Russia party.

After a bomb exploded in a crowded Saint Petersburg food market on December 27, injuring dozens of people, Putin revived his popular “tough on terror” tone just before the election. He stated that he had ordered Federal Security Service officers to “take no prisoners” when dealing with terrorists.

In his annual address to the Duma in March 2018, just days before the election, Putin claimed that the Russian military had perfected nuclear missiles with “unlimited range” that would render NATO anti-missile systems “completely worthless.” While U.S. officials expressed doubts about their reality, Putin’s claims and saber-rattling tone ratcheted up tensions with the West but nurtured renewed feelings of national pride among Russian voters.

On March 18, 2018, Putin was easily elected to a fourth term as President of Russia, winning more than 76 percent of the vote in an election that saw 67 percent of all eligible voters cast ballots. Despite the opposition to his leadership that had surfaced during his third term, his closest competitor in the election garnered only 13 percent of the vote. Shortly after officially taking office on May 7, Putin announced that in compliance with the Russian Constitution, he would not seek reelection in 2024.

On July 16, 2018, Putin met with U.S. President Donald Trump in Helsinki, Finland, in what was called the first of a series of meetings between the two world leaders. While no official details of their private 90-minute meeting were published, Putin and Trump would later reveal in press conferences that they had discussed the Syrian civil war and its threat to the safety of Israel, the Russian annexation of Crimea , and the extension of the START nuclear weapons reduction treaty.

On February 23, 2022, Putin launched an unprovoked military invasion of Ukraine, which had officially declared itself an independent country on August 24, 1991. Putin justified the act with the false narrative that Ukraine was not a real country. That it “belongs” to Russia as part of a “Great Russia” and the “Russian World,” and that there is, according to Putin, no Ukrainian people, no Ukrainian language, and no separate Ukrainian history.

After Russia launched its 2022 invasion, the United States, the European Union (EU), and other NATO member nations condemned Putin, substantially increased military, humanitarian, and economic assistance to Ukraine, and imposed a series of increasingly crippling financial and economic sanctions on Russia. In addition, hundreds of U.S. and other companies withdrew, suspended, or curtailed operations in or with Russia.

On February 8, 1994, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization ( NATO ) accepted Ukraine into its Partnership for Peace, a collaborative arrangement open to all non-NATO European countries and post-Soviet states. Russia became a NATO member in June 1994 and conducted various cooperative activities with NATO, including joint military exercises, until 2014, when NATO formally suspended ties with the country. As the Cold War ended, Russia opposed the eastern expansion of NATO. However, thirteen former Soviet partnership members eventually joined the alliance.

Ukraine is not a NATO member. However, Ukraine is a NATO partner country, which means that it cooperates closely with NATO but it is not covered by the security guarantee in the Alliance’s founding treaty.

The invasion seemed to tarnish Putin’s image among the Russian people, as young citizens, along with middle-aged and even retired people, took to the streets to speak out against a military conflict ordered by their President—a decision in which, they claimed, they had no say.

Putin responded by shutting down public dissent against the attack on Ukraine. By the end of July 2022, a total of over 7,624 protesters had been detained or arrested to 7,624 since the invasion began, according to an independent organization that tracks human rights violations in Russia.

During Putin’s third presidential term, allegations arose in the United States that the Russian government had interfered in the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

A combined U.S. intelligence community report released in January 2017 found “high confidence” that Putin himself had ordered a media-based “influence campaign” intended to harm the American public’s perception of Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton , thus improving the electoral chances of eventual election winner, Republican Donald Trump . In addition, the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is investigating whether officials of the Trump campaign organization colluded with high ranking Russian officials to influence the election.

While both Putin and Trump have repeatedly denied the allegations, the social media website Facebook admitted in October 2017 that political ads purchased by Russian organizations had been seen by at least 126 million Americans during the weeks leading up to the election.

Vladimir Putin married Lyudmila Shkrebneva on July 28, 1983. From 1985 to 1990, the couple lived in East Germany where they gave birth to their two daughters, Mariya Putina and Yekaterina Putina. On June 6, 2013, Putin announced the end of the marriage. Their divorce became official on April 1, 2014, according to the Kremlin. An avid outdoorsman, Putin publicly promotes sports, including skiing, cycling, fishing, and horseback riding as a healthy way of life for the Russian people.

While some say he may be the world’s wealthiest man, Vladimir Putin’s exact net worth is not known. According to the Kremlin, the President of the Russian Federation is paid the U.S. equivalent of about $112,000 per year and is provided with an 800-square foot apartment as an official residence. However, independent Russian and U.S. financial experts have estimated Putin’s combined net worth at from $70 billion to as much as $200 billion. While his spokespersons have repeatedly denied allegations that Putin controls a hidden fortune, critics in Russia and elsewhere remain convinced that he has skillfully used the influence of his nearly 20-years in power to acquire massive wealth.

A member of the Russian Orthodox Church, Putin recalls the time his mother gave him his baptismal cross, telling him to get it blessed by a Bishop and wear it for his safety. “I did as she said and then put the cross around my neck. I have never taken it off since,” he once recalled.

As one of the most powerful, influential, and often-controversial world leaders of the past two decades, Vladimir Putin has uttered many memorable phrases in public. A few of these include:

- “There is no such thing as a former KGB man.”

- “People are always teaching us democracy but the people who teach us democracy don't want to learn it themselves.”

- “Russia doesn’t negotiate with terrorists. It destroys them.”

- “In any case, I’d rather not deal with such questions, because anyway it’s like shearing a pig—lots of screams but little wool.”

- “I am not a woman, so I don’t have bad days.”

- “ Vladimir Putin Biography .” Vladimir Putin official state biography

- “ Vladimir Putin – President of Russia .” European-Leaders.com (March 2017)

- “ First Person: An Astonishingly Frank Self-Portrait by Russia's President Vladimir Putin .” The New York Times (2000)

- “ Putin’s Obscure Path From KGB to Kremlin .” Los Angeles Times (2000)

- “ Vladimir Putin quits as head of Russia's ruling party .” The Daily Telegraph (2002)

- “ Russian lessons .” Financial Times. September 20, 2008

- “ Russia: Bribery Thriving Under Putin, According To New Report .” Radio Free Europe (2005)

- Steele, Jonathan. “ Putin’s legacy is a Russia that doesn't have to curry favour with the west .” The Guardian, September 18, 2007

- Bohlen, Celestine (2000). “ YELTSIN RESIGNS: THE OVERVIEW; Yeltsin Resigns, Naming Putin as Acting President To Run in March Election .” The New York Times.

- Sakwa, Richard (2007). “Putin : Russia's Choice (2nd ed.).” Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 9780415407656.

- Judah, Ben (2015). “Fragile Empire: How Russia Fell in and Out of Love with Vladimir Putin.” Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300205220.

- Boris Yeltsin: First President of the Russian Federation

- Political Parties in Russia

- A Brief History of the KGB

- The "Deep State" Theory, Explained

- What Is Balkanization?

- The Truth Behind 14 Well-Known Russian Stereotypes

- The History and Geography of Crimea

- The Biggest Donald Trump Scandals (So Far)

- What Was the USSR and Which Countries Were in It?

- Causes of the Russian Revolution

- What Is an Oligarchy? Definition and Examples

- Biography of Nikita Khrushchev, Cold War Era Soviet Leader

- Saparmurat Niyazov

- Geography of Moscow, Russia

- Geography and History of Finland

- Top Books: Modern Russia - The Revolution and After

A life on the world stage, but scant biographical details: What we know of the life of Vladimir Putin

- He was born 1952 in what used to be Leningrad, USSR and is now St. Petersburg,, Russia.

- Over the last 20 years, Putin has consolidated his grip on power by transforming many Russian institutions.

- Because of his political longevity, Putin has seen five U.S. presidents come and four go.

MOSCOW – For as long as he's been in the public eye, Russian President Vladimir Putin has been a closed book, with relatively few confirmed facts about his real thinking on foreign affairs and what motivates his policy actions. His personal life, too, has been shrouded in mystery and controversy.

And now the Putin enigma is testing the world again because of fears he may launch an invasion of Ukraine, Russia's western neighbor, and what this could mean for Ukraine's fragile democracy and the broader U.S. and European security order in place on the continent for decades.

With the crisis deepening, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken are expected to meet for talks in Europe next week. But President Joe Biden, while leaving the door to diplomacy open, left no doubt Friday that he's "convinced" Putin has already made up his mind to invade.

Here are some basics of what is known about Putin. Subscribers can read a more in-depth story about Russia's longest-serving leader here .

Putin's early days

Putin was born 1952 in what used to be called Leningrad, USSR, and is now known as St. Petersburg, Russia. He served for 15 years in the KGB, the Soviet-era agency that was the counterpart to the CIA. The spy agency was a notorious symbol of the Cold War and became the focus of a slew of U.S. spy novels and movies.

During that time, in 1983, he married a flight attendant named Lyudmila. They had two daughters, Mariya and Katerina. Putin and Lyudmila divorced in 2013. He may have another child, possibly with former Russian gymnastics champion Alina Kabaeva.

By 1994, Putin had become deputy mayor in the city of his birth, and by 1998, the director of the FSB, the KBG's domestic successor. A year later, Putin was prime minister, then president – one of two positions he's held ever since.

Trouble at home

Over the last two decades, Putin has consolidated his grip on power by transforming Russia's courts, media and other governance institutions to serve the whims of one person: himself. He has spent lavishly on the the military, banned or jailed opposition politicians and journalists and cultivated support from right-wing, nationalist groups. He changed Russia's constitution so he can stay in power until 2036, perhaps even longer.

Putin has also presided over a growing Russian middle class, modernized some areas of Russia's economy such as in banking and technology and weathered successive financial crises because of Russia's enormous strategic oil and gas reserves. He has sought to crack down on dissent by banning restricting free speech on the Internet.

On the world stage

Because of his political longevity, Putin has seen five U.S. presidents come and four go. During this time there has been cooperation on trade, nuclear and ballistic missile treaties, fighting terrorism and more.

There has also been sharp divergence – on human rights, on the wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria, on the rule of law, on Moscow's apparent or at least tacit support for cyber-hackers, and on what countries such as Ukraine and Georgia, formed in the wake of the Soviet Union's break-up in 1991 , should be allowed to do in terms of carving out their own cultural and ideological destinies.

What is NATO?: Military alliance in spotlight as Russia tries to forbid Ukraine membership

Ukraine has aspirations to join the 30-nation NATO military alliance that was formed in the wake of World War II to help keep the peace in Europe. It seeks to lean west toward democracies in the European Union.

The NATO bloc's gradual encroachment east toward countries that border Russia is seen by Putin as a threat to Moscow's security and sphere of influence. It is this, partly, analysts believe, that underpinned Russia's annexation of Crimea in 2014 and Moscow's support for separatist rebels in Ukraine's Donbass region, where fighting has raged for eights years and is now the subject of an intense international spotlight because of what it could say about Putin's invasion plans.

What the people want

Ordinary Russians, meanwhile, are more afraid today than they have been for 30 years that Putin could drag their country into a full-scale war with Ukraine, according to Lev Gudkov, the director of the Levada Center, an independent research organization.

Some 62% of Russians surveyed by the Levada Center said they were worried Russia could be facing "World War III," Gudkov told USA TODAY.

In Ukraine, a survey released Friday by research firm Rating Sociological Group found that 25% of respondents saw little-to-no threat of a Russian invasion; 19% of those surveyed said there was a "high" chance Moscow could invade.

Biography Online

Vladimir Putin Biography

Vladimir Putin (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician who served as Russian President from 2000 to 2008, and from 2012 onwards. Between 2008-2012, he served as Russian Prime Minister making him the most powerful and de facto leader in Russia during this time in office. Since 2012 he has served as Russian President and has embarked on efforts to strengthen “Russia’s strategic interests” culminating in the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

Putin studied Law at Leningrad State University, writing a PhD thesis on the importance of energy policy for future Russian economic success. After graduating in 1975, he joined the KGB. He was involved in monitoring foreigners and consular officials in Leningrad. From 1985 to 1990 he was posted to Dresden, East Germany. On the collapse of the East German government, he returned to Leningrad where he was involved in surveillance of the student body.

In August 1981, there was an attempted coup by Communist hard-liners with links to military and KGB against Mikhail Gorbachev . On the second day of the putsch, Putin resigned from the KGB and sought to pursue a political career. Putin said the decision to resign from the KGB was hard, but he didn’t support the direction of the coup and the hard-liners.

In 1997, Boris Yeltsin appointed him to the position of deputy chief of the Presidential staff. In 1999, with the backing of Yeltsin, he was voted as Prime Minister of Russia. When Yeltsin, unexpectedly resigned a few months later, Putin became the default President of Russia.

During the early years of his Presidency, Putin gained substantial popular backing because of his hard-line on military issues (such as the war in Chechnya) and overseeing a return to economic stability. He cultivated a macho ‘action man’ image of fearless leader and sportsman, helped by his sporting and KGB past. This image was attractive to voters. After a decade of inflation and falling living standards, during the 2000s, Russia embarked on a sustained period of economic growth, falling unemployment and rising living standards. The strong performance of the economy was attributable to the rising price of oil and gas (increasing value of Russia’s exports) and strong macroeconomic management.

Early in his leadership, he came to an arrangement with the new Russian ‘oligarchs’ powerful businessmen who had gained control of formerly state-owned industries. Putin made a deal where they agreed to start paying tax and avoiding politics, in return for leaving them free to pursue their business interests. This helped raise revenue for the government and reduced the political influence of the Oligarchs.

In 2008, unable to run for a third term as President, he ran for Prime minister, with his dual political aid Medvedev becoming President. However, it was Putin who remained the most powerful figure.

In 2012, Putin was re-elected for a third term as President, however, for the first time, this led to widespread protests at the lack of democracy in Russia. Increasingly, Putin’s regime has been criticised for being dictatorial and avoiding a true democracy.

For example, former Russian President Gorbachev, who was initially a supporter of Putin said he was disappointed by the increased disrespect for democracy and authoritarian tendencies. In 2007, Gorbachev said Putin had ‘pulled Russia out of chaos’. But, in 2011 criticised Putin for seeking a third term as President. Gorbachev was severely critical of the 2011 elections. “The results do not reflect the will of the people,” Mr Gorbachev said at the time. “Therefore I think they [Russia’s leaders] can only take one decision – annul the results of the election and hold new ones.” ( Gorbachev calls on Putin to resign )

On July 28, 1983, Putin married Lyudmila Shkrebneva. They have two daughters, Maria Putina (born 1985) and Yekaterina (Katya) Putina (born 1986 in Dresden). Putin himself is a practising member of the Russian Orthodox Church. His religious awakening followed the serious car crash of his wife in 1993 and was deepened by a life-threatening fire that burned down their dacha in August 1996. Right before an official visit to Israel, his mother gave him his baptismal cross telling him to get it blessed “I did as she said and then put the cross around my neck. I have never taken it off since.”

Putin has been hailed by Patriarch Alexius II of the Russian Orthodox Church as instrumental in healing the 80-year schism between it and the Russian Orthodox Church outside Russia in May 2007. Putin was supportive of the Russian Orthodox church in supporting the imprisonment of members of ‘Pussy Riot’ the pop group who protested about Putin and the Church. However, the decision to imprison members of Pussy Riot was widely condemned across the world for breaching human rights.

In March 2014, in the wake of turmoil in Ukraine, Putin authorised the use of Russian troops to enter the region of Crimea. Shortly after, a referendum was organised where a majority of people voted to leave the Ukraine and rejoin Russia. There was criticism over the legitimacy of the referendum, but Crimea has effectively left Ukraine for Russia. The issue over Ukraine has led to increased tension between Russia and the West.

2016 US election

During the 2016 US election, it was alleged that Russian operators sought to influence the 2016 Presidential election by posting social media items which helped Donald Trump and hindered Hilary Clinton. Similar allegations were made with regard to the UK vote on Brexit. Although Putin denies influencing elections, there is evidence Russian foreign policy is geared towards destabilising Western democracies and weakening the NATO alliance. A long-standing grievance of Putin is the eastward expansion of NATO after the end of the cold war.

Under Trump, the NATO alliance was weakened, with Trump being the most pro-Russian president in modern times. However, later actions in the Ukraine had the effect of uniting the west and made NATO membership for Finland and Sweden appear more attractive.

2018 Russian election

In 2018, Putin won a fourth Presidential term, with 76% of the vote. Political opponents argue the system is rigged with opposition candidates placed under arrest or prevented from actively campaigning. Putin has suggested he will not run again in 2024, but his party United Russia have a powerful monopoly on local and national elections, and it is not certain when this will be ended. Putin’s regime has become increasingly authoritarian with opposition leaders being given the choice of ‘go west or go east’ – West meant to leave the country, east means to the Siberian prison camps. Notable opposition leader Alexei Navalny survived an attempted poisoning but on surviving choose to return to Europe where he was arrested on trumped up charges.

2022 Ukraine invasion

In early 2022, Russian troops massed on the border of Ukraine, with US and UK authorities warning an invasion of Ukraine was imminent. This was denied by the Kremlin but on 25 February Russian armoured units entered Ukraine. Putin claimed it was a ‘special military operation’ but heavy fighting and shelling began on Ukraine’s major cities Kyiv and Kharkiv. In response to the illegal invasion, western countries imposed severe economic sanctions on Russia, which led to a sharp drop in the Ruble and Russian stock market. Many analysts were surprised at the reckless gamble taken by Putin as it leaves the country increasingly isolated and an international pariah after being excluded from major sporting and cultural events as well as economic sanctions.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “ Biography of Vladimir Putin” , Oxford, UK. www.biographyonline.net Published 23rd May 2012. Last updated 1 March 2022.

Vladimir Putin and Russian Statecraft

Vladimir Putin and Russian Statecraft at Amazon

Related pages

- Putin quotes

- World Biography

Vladimir Putin Biography

Born: October 1, 1952 Leningrad, Russia Russian president

When Vladimir Putin was appointed prime minister of Russia, very little was known about his background. This former Soviet intelligence agent entered politics in the early 1990s and rose rapidly. By August of 1999, ailing President Boris Yeltsin (1931–) appointed him prime minister. When Yeltsin stepped down in December of 1999, Putin became the acting president of Russia, and he was elected president to serve a full term on March 26, 2000.

Early life and education

Vladimir Putin was born on October 1, 1952, in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), Russia. An only child, his father was a foreman in a metal factory and his mother was a homemaker. Putin lived with his parents in an apartment with two other families. Though religion was not permitted in the Soviet Union, the former country which was made up of Russia and other smaller states, his mother secretly had him baptized as an Orthodox Christian.

Work in the KGB

At Leningrad State University, Putin graduated from the law department in 1975 but instead of entering the law field right out of school, Putin landed a job with the KGB, the only one in his class of one hundred to be chosen. The branch he was assigned to was responsible for recruiting foreigners who would work to gather information for KGB intelligence.

In the early 1980s Putin met and married his wife, Lyudmila, a former teacher of French and English. In 1985 the KGB sent him to Dresden, East Germany, where he lived undercover as Mr. Adamov, the director of the Soviet-German House of Friendship, a social and cultural club. Putin appeared to genuinely enjoy spending time with Germans, unlike many other KGB agents, and respected the German culture.

Around the time Putin went to East Germany, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev (1931–) was beginning to introduce economic and social reforms (improvements). Putin was apparently a firm believer in the changes. In 1989 the Berlin Wall, which stood for nearly forty years separating East from West Germany, was torn down and the two united. Though Putin supposedly had known that this was going to happen, he was disappointed that it occurred amid chaos and that the Soviet leadership had not managed it better.

Russian politics

In 1990 Putin returned to Leningrad and continued his undercover intelligence work for the KGB. In 1991, just as the Soviet Union was beginning to fall apart, Putin left the KGB with the rank of colonel, in order to get involved in politics. Putin went to work for Anatoly Sobchak, the mayor of St. Petersburg, as an aide and in 1994 became deputy mayor.

During Putin's time in city government, he reportedly helped the city build highways, telecommunications, and hotels, all to support foreign investment. Although St. Petersburg never grew to become the financial powerhouse that many had hoped, its fortunes improved as many foreign investors moved in, such as Coca-Cola and Japanese electronics firm NEC.

On to the Kremlin

In 1996, when Sobchak lost his mayoral campaign, Putin was offered a job with the victor, but declined out of loyalty. The next year, he was asked to join President Boris Yeltin's "inner circle" as deputy chief administrator of the Kremlin, the building that houses the Russian government. In March of 1999, he was named secretary of the Security Council, a body that advises the president on matters of foreign policy, national security, and military and law enforcement.

In August of 1999, after Yeltsin had gone through five prime ministers in seventeen months, he appointed Putin, who many thought was not worthy of succeeding the ill president. For one thing, he had little political experience; for another, his appearance and personality seemed boring. However, Putin increased his appeal among citizens for his role in pursuing the war in Chechnya. In addition to blaming various bombings in Moscow and elsewhere on Chechen terrorists, he also used harsh words in criticizing his enemies. Soon, Putin's popularity ratings began to soar.

Acting president of Russia

In December of 1999, Russia held elections for the 450-seat Duma, the lower house of Russia's parliament (governing body). Putin's newly-formed Unity Party came in a close second to the Communists in a stunning showing. Though Putin was not a candidate in this election, he became the obvious front-runner in the upcoming presidential race scheduled for June of 2000.

On New Year's Eve in 1999, Yeltsin unexpectedly stepped down as president, naming Putin as acting president. Immediately, Western news media and the U.S. government scrambled to create a profile of the new Russian leader. Due to Putin's secretive background as a KGB agent, there was little information. His history as a spy caused many Westerners and some Russians as well to question whether he should be feared as an enemy of the free world.

In Putin's first speech as acting president, he promised, "Freedom of speech, freedom of conscience, freedom of the press, the right to private property—these basic principles of a civilized society will be protected," according to a Newsweek report. In addition, Putin removed several of Yeltsin's loyalists and relatives from his cabinet.

Elected President

On March 26, 2000, Russians elected Putin out of a field of eleven candidates. After his election, Putin's first legislative move was to win approval of the Start II arms reduction treaty from the Duma. The deal, which was negotiated seven years earlier, involved decreasing both the Russian and American nuclear buildup by half. Putin's move on this issue was seen as a positive step in his willingness to develop a better relationship with the United States. In addition, one of Putin's earliest moves involved working with a team of economists to develop a plan to improve the country's economy. On May 7, 2000, Putin was officially sworn in as Russia's second president and its first in a free transfer of power in the nation's eleven-hundred-year history.

Putin, a soft-spoken and stone-faced man, keeps his personal life very private. In early 2000, an American publishing company announced that in May it would release an English-language translation of his memoirs, First Person, which was banned from publication in Russia until after the March 26 presidential election.

Putin has made great efforts to improve relations with the remaining world powers. In July 2001, Putin met with Chinese President Jiang Zemin (1926–) and the two signed a "friendship treaty" which called for improving trade between China and Russia and improving relations concerning U.S. plans for a missile defense system. Four months later, Putin visited Washington, D.C. to meet with President George W. Bush (1946–) over the defense system. Although they failed to reach a definite agreement, the two leaders did agree to drastically cut the number of nuclear arms in each country. Early in 2002, Putin traveled to Poland and became the first Russian president since 1993 to make this trip. Representatives of the two countries signed agreements involving business, trade, and transportation.

For More Information

Putin, Vladimir. First Person. New York: PublicAffairs, 2000.

Shields, Charles J. Vladimir Putin. Philadelphia: Chelsea House, 2002.

User Contributions:

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic:.

Advertisement

New biography 'Putin' takes a deep dive into the Russian leader

Copy the code below to embed the wbur audio player on your site.

<iframe width="100%" height="124" scrolling="no" frameborder="no" src="https://player.wbur.org/hereandnow/2022/07/26/putin-book-philip-short"></iframe>

- Emiko Tamagawa

Editor's note: This segment was rebroadcasted on Dec. 26, 2022. Find that audio here .

Vladimir Putin may be the most dangerous man in the world. But longtime foreign correspondent Philip Short is taking a closer look into the Russian President’s story.

Short’s new book “Putin” examines Putin’s life and how he became the leader he is today, one that associates describe as a shapeshifter or unreliable narrator. The book also dives into Putin’s complicated relationship with the West, how he functions as a leader in Russia, and how Russia has become more authoritarian over time.

Interview Highlights

On Putin’s story working as a KGB intelligence officer in the ‘80s, where a mob allegedly threatened to storm the KGB headquarters “It's theatrical, isn't it? Moscow is silent and it's a paraphrase of [Alexander] Pushkin. He is a person who is in many respects an actor. He assumes guises. If you actually look back at what happened that day, there wasn't a mob storming the KGB headquarters. Yes, there was a crowd who were pretty angry, but they weren't going to do anything. And he dramatized that in his mind. And he said Moscow was silent.

“Actually, the local Red Army base sent in troops to help him within thirty minutes. So this is typical. You have to be very, very careful in what you believe in. One of his friends, a German businessman in St. Petersburg in the 1990s, says he's a shapeshifter. He assumes guises, he assumes images which fit with the narrative that he wants to tell and with the person he's talking to.”

On how Putin spun the narrative when discussing the story years later “The narrative essentially is one which we've heard very often since that the collapse of the Soviet Union, the humiliation of the Soviet Union, the failure of the Soviet Union to defend its friends. This was a monumental tragedy. But again, you've got to watch it rather carefully, because he's also said anyone who doesn't want the Soviet Union back again, anyone who doesn't regret the collapse of the Soviet Union doesn't have a heart. Anyone who actually thinks that it should be brought back, who think they could bring it back, doesn't have a head.”

On if Putin was open to closer relations with the U.S., NATO and Western Europe “Putin did genuinely believe that Russia's future was with the West, that Russia's future was certainly as part of Europe, and that Russia should become part of what he called the ‘civilized world,’ which was the Western led-world. So when people say he's been kind of acting from the very beginning and he was always deeply hostile to the West. That is simply not true. There's been an incremental change which has spread out. It's been a kind of tragic inevitability in many ways of what has happened over the last twenty years from really genuinely pro-Western Putin to a very hostile Putin.”

On what Putin thought about George Bush’s 2005 inaugural address, which acknowledged Central and Eastern European citizens’ right to decide their future. “[Putin] was reading it as a commitment by the United States to promote democracy in the rest of the world, but not just democracy, but the American conception of democracy. And it was one of the elements which convinced Putin that America wanted to call the shots and that Russia would absolutely have to follow both countries.

“I think it's really important to say this. Both countries, the United States and Russia, made mistakes. Things could have worked out differently. But who won the Cold War? America won the Cold War. It's always the victor in a war who determines what the subsequent evolution of events is going to be. If you look at the various things that America did, it's not just NATO's expansion, that's possibly not even the most important. But walking away from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty because it was was seen as constraining ability, America's ability to develop new weapons systems.