- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Criminal Investigation

Introduction, general overviews.

- Crime Scene Processing

- Historical Foundations

- Forensic Anthropology

- Forensic Entomology

- Forensic Nursing

- Forensic Science

- Forensic Art and Photography

- Interviewing and Interrogation

- Forensic Psychology and Profiling

- Fraud and White-Collar Crime

- Hate Crimes

- International

- Internet, Digital, and Cybercrime Investigations

- Terrorism and Homeland Security Investigations

- Victimology

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Co-Offending and the Role of Accomplices

- Eyewitness Testimony

- False and Coerced Confessions

- Interrogation

- Police Effectiveness

- Policing and Law Enforcement

- Proactive Policing

- Snitching and Use of Criminal Informants

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Education Programs in Prison

- Mixed Methods Research in Criminal Justice and Criminology

- Victim Impact Statements

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Criminal Investigation by Richard H. Ward LAST REVIEWED: 25 February 2015 LAST MODIFIED: 28 July 2015 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780195396607-0079

Criminal investigation as a discipline within the fields of law enforcement (criminal justice) that focuses on the solution of crime at the local, state, and federal levels of government, within defined jurisdictional areas that may overlap. A crime is based on a legal definition prescribed by a governmental entity, such as a state legislature or the US Congress. The field of criminal investigation encompasses a number of cognate areas that begin with the report or suspicion that a crime has occurred, an initial or preliminary evaluation to determine that a crime has occurred, and generally an assignment to an investigator, who may be a police officer, a detective, a special agent, or other investigator, depending on jurisdictional entity: police department, prosecutor, or federal agency, such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), Secret Service, or one of more than a hundred federal agencies with some form of jurisdictional responsibility for conducting criminal investigations. Rapid advances in science and technology have changed the role of the criminal investigator dramatically, leading to much higher degrees of specialization than in the past, including but not limited to such areas as forensic accounting and fraud; cyber-crime, Internet stalking and child pornography; human trafficking and the exploitation of women and children; homeland security, terrorism, and international organized crime; and theft of art and cultural objects. These types of crime have also resulted in changes to the organizational structure of larger law enforcement agencies as new units have emerged. In the past, criminal investigation units normally assigned detectives to crimes against property (e.g., burglary and robbery) and violent crimes (e.g., homicide, sexual assault). Today, specialized units frequently utilize investigators who have a much narrower perspective and particular expertise. Closely related to these areas has been the role of the private sector in criminal investigations. Most large corporations now have investigative arms that focus on criminal activity within and against the organization. Additionally, the tools, both human and scientific, have placed greater emphasis on the role of the crime laboratory (forensic science) and the utilization of technology in support of the investigative function. Perhaps the best example has been the use of DNA analysis. Advances in crime analysis using sophisticated software—such as relational databases and geospatial programs—have contributed to developing patterns, identifying suspects, and linking common elements of criminal activity. Other advances in technology, such as social media, the use of drones, and digital photography and imaging are examples. Many of these techniques are under judicial examination, particularly in the areas of surveillance, interviewing and interrogation, and analytics. Court decisions and changes in procedural aspects of criminal investigation and forensic science have also led to criticism of many past practices in such areas as interagency cooperation, evidence collection and analysis, interviewing and interrogation, electronic surveillance, and political and media influence.

In addition to general introductory criminal investigation texts, there are, within the field of criminal investigation, a number of areas involving investigative support and specialized types of investigations. Public interest, the media, and high-profile cases have contributed to a growing literature, and the expansion of investigative studies in criminal justice educational programs, as well as training programs for new and specialized areas of investigation. Several areas have produced more specific publications and are covered as subsections within this bibliographic compilation. Additionally, research on various types of crime has contributed to changes in process and procedures, as well as dispelling many long-held views on criminality and crime investigation, such as the modus operandi (method of operation) of criminals, psychological profiling, interviewing and interrogation, and the use of physical evidence. An increasing number of publications of general interest provide an overview of procedural techniques and failures in the investigative process, and a growing body of knowledge on specific types of crime and investigation has produced a rich source of literature available to researchers and criminal investigators. Introductory texts focus largely on a broad description of basic criminal investigation written almost exclusively for undergraduate courses. Each of the books below provides perceptions of the investigative function over time. O’Hara 2003 was used extensively in courses in the 1960s and offers a basic view of the way in which detectives work, and in more recent times as technical and forensics have improved, Becker 2009 ; Osterburg and Ward 2014 ; and Swanson, et al. 2008 have gained greater acceptance in the field as introductory texts. Lee and O’Neill 2002 and Saferstein 2006 emphasize forensics and the methodology involved in solving a case, whereas LaFave, et al. 2009 emphasizes the basic components of case preparation. Douglas and several others have expanded the use of forensic psychology. Rossmo 2008 makes an important contribution in illustrating the mistakes that investigators have made in various cases. The journals cited here provide an overview of the research literature available to scholars and practitioners. Increasing emphasis on the criminal intelligence function has emphasized research into techniques and policies, as well as more focused studies related to national security and terrorism.

Becker, Ronald. 2009. Criminal investigation . 3d ed. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett.

Emphasizes the role of the investigator in the investigative process, and the relationship between actors in various aspects of a case. Includes sections on underwater investigations and terrorism.

Brandl, Steven G. 2014. Criminal investigation . 3d ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Introductory text covering the key aspects of a criminal investigation and many of the drawbacks to a successful investigation. Includes a capstone case designed for students to apply what they have learned.

LaFave, Wayne R., Jerold H. Israel, Nancy J. King, and Orin S. Kerr. 2009. Principles of criminal procedure: Investigation . 2d ed. Concise Hornbook series. St. Paul, MN: West.

This classic text in the field presents the elements and processes of criminal procedure in detail, which range from initial investigations through trial. The book focuses largely on what is necessary to prepare a criminal case for the courts.

Lee, Henry, and Thomas W. O’Neill. 2002. Cracking cases: The science of solving crimes . Amherst, NY: Promethus.

Dr. Henry Lee, a noted forensic scientist, who has consulted on hundreds of high-profile murder cases, and his coauthor provide detailed information on numerous investigations and on the importance of science and observation (deduction) in reviewing criminal cases.

O’Hara, Charles E., and Gregory L. O’Hara. 2003. Fundamentals of criminal investigation . Springfield, IL: C. C. Thomas.

One of the earlier basic texts on criminal investigation; the role of the investigator is explained in detail, from the crime scene search to preparing a case for prosecution.

Osterburg, James W., and Richard H. Ward. 2014. Criminal investigation: A method for reconstructing the past . 6th ed. Albany, NY: LexisNexis-Anderson.

A comprehensive examination of basic and advanced aspects of criminal investigation, this text includes a broader selection of different types of crime investigation, and a lengthy description of forensic science applications and investigative techniques.

Rossmo, Kim. 2008. Criminal investigative failures . Boca Raton, FL: Taylor and Francis.

DOI: 10.1201/9781420047523

The author develops case studies of errors, mistakes, and false judgments associated with many aspects of the investigative process.

Saferstein, Richard. 2006. Criminalistics: An introduction to forensic science . 9th ed. Harlow, UK: Pearson-Prentice Hall.

One of the more comprehensive texts on forensic science methods and applications, designed largely for the novice or new student interested in a career as a forensic scientist.

Swanson, Charles, Neil Chamelin, Leonard Territo, and Robert Taylor. 2008. Criminal investigation . 10th ed. New York: McGraw Hill.

A popular introductory text written by authors with years of field experience, this book encompasses many of the techniques and tactics involved in general criminal investigations. A basic text of particular interest to those unfamiliar with the investigative process.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Criminology »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Active Offender Research

- Adler, Freda

- Adversarial System of Justice

- Adverse Childhood Experiences

- Aging Prison Population, The

- Airport and Airline Security

- Alcohol and Drug Prohibition

- Alcohol Use, Policy and Crime

- Alt-Right Gangs and White Power Youth Groups

- Animals, Crimes Against

- Back-End Sentencing and Parole Revocation

- Bail and Pretrial Detention

- Batterer Intervention Programs

- Bentham, Jeremy

- Big Data and Communities and Crime

- Biosocial Criminology

- Black's Theory of Law and Social Control

- Blumstein, Alfred

- Boot Camps and Shock Incarceration Programs

- Burglary, Residential

- Bystander Intervention

- Capital Punishment

- Chambliss, William

- Chicago School of Criminology, The

- Child Maltreatment

- Chinese Triad Society

- Civil Protection Orders

- Collateral Consequences of Felony Conviction and Imprisonm...

- Collective Efficacy

- Commercial and Bank Robbery

- Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children

- Communicating Scientific Findings in the Courtroom

- Community Change and Crime

- Community Corrections

- Community Disadvantage and Crime

- Community-Based Justice Systems

- Community-Based Substance Use Prevention

- Comparative Criminal Justice Systems

- CompStat Models of Police Performance Management

- Confessions, False and Coerced

- Conservation Criminology

- Consumer Fraud

- Contextual Analysis of Crime

- Control Balance Theory

- Convict Criminology

- Corporate Crime

- Costs of Crime and Justice

- Courts, Drug

- Courts, Juvenile

- Courts, Mental Health

- Courts, Problem-Solving

- Crime and Justice in Latin America

- Crime, Campus

- Crime Control Policy

- Crime Control, Politics of

- Crime, (In)Security, and Islam

- Crime Prevention, Delinquency and

- Crime Prevention, Situational

- Crime Prevention, Voluntary Organizations and

- Crime Trends

- Crime Victims' Rights Movement

- Criminal Career Research

- Criminal Decision Making, Emotions in

- Criminal Justice Data Sources

- Criminal Justice Ethics

- Criminal Justice Fines and Fees

- Criminal Justice Reform, Politics of

- Criminal Justice System, Discretion in the

- Criminal Records

- Criminal Retaliation

- Criminal Talk

- Criminology and Political Science

- Criminology of Genocide, The

- Critical Criminology

- Cross-National Crime

- Cross-Sectional Research Designs in Criminology and Crimin...

- Cultural Criminology

- Cultural Theories

- Cybercrime Investigations and Prosecutions

- Cycle of Violence

- Deadly Force

- Defense Counsel

- Defining "Success" in Corrections and Reentry

- Developmental and Life-Course Criminology

- Digital Piracy

- Driving and Traffic Offenses

- Drug Control

- Drug Trafficking, International

- Drugs and Crime

- Elder Abuse

- Electronically Monitored Home Confinement

- Employee Theft

- Environmental Crime and Justice

- Experimental Criminology

- Family Violence

- Fear of Crime and Perceived Risk

- Felon Disenfranchisement

- Feminist Theories

- Feminist Victimization Theories

- Fencing and Stolen Goods Markets

- Firearms and Violence

- For-Profit Private Prisons and the Criminal Justice–Indust...

- Gangs, Peers, and Co-offending

- Gender and Crime

- Gendered Crime Pathways

- General Opportunity Victimization Theories

- Genetics, Environment, and Crime

- Green Criminology

- Halfway Houses

- Harm Reduction and Risky Behaviors

- Hate Crime Legislation

- Healthcare Fraud

- Hirschi, Travis

- History of Crime in the United Kingdom

- History of Criminology

- Homelessness and Crime

- Homicide Victimization

- Honor Cultures and Violence

- Hot Spots Policing

- Human Rights

- Human Trafficking

- Identity Theft

- Immigration, Crime, and Justice

- Incarceration, Mass

- Incarceration, Public Health Effects of

- Income Tax Evasion

- Indigenous Criminology

- Institutional Anomie Theory

- Integrated Theory

- Intermediate Sanctions

- Interpersonal Violence, Historical Patterns of

- Intimate Partner Violence, Criminological Perspectives on

- Intimate Partner Violence, Police Responses to

- Investigation, Criminal

- Juvenile Delinquency

- Juvenile Justice System, The

- Kornhauser, Ruth Rosner

- Labeling Theory

- Labor Markets and Crime

- Land Use and Crime

- Lead and Crime

- LGBTQ Intimate Partner Violence

- LGBTQ People in Prison

- Life Without Parole Sentencing

- Local Institutions and Neighborhood Crime

- Lombroso, Cesare

- Longitudinal Research in Criminology

- Mandatory Minimum Sentencing

- Mapping and Spatial Analysis of Crime, The

- Mass Media, Crime, and Justice

- Measuring Crime

- Mediation and Dispute Resolution Programs

- Mental Health and Crime

- Merton, Robert K.

- Meta-analysis in Criminology

- Middle-Class Crime and Criminality

- Migrant Detention and Incarceration

- Mixed Methods Research in Criminology

- Money Laundering

- Motor Vehicle Theft

- Multi-Level Marketing Scams

- Murder, Serial

- Narrative Criminology

- National Deviancy Symposia, The

- Nature Versus Nurture

- Neighborhood Disorder

- Neutralization Theory

- New Penology, The

- Offender Decision-Making and Motivation

- Offense Specialization/Expertise

- Organized Crime

- Outlaw Motorcycle Clubs

- Panel Methods in Criminology

- Peacemaking Criminology

- Peer Networks and Delinquency

- Performance Measurement and Accountability Systems

- Personality and Trait Theories of Crime

- Persons with a Mental Illness, Police Encounters with

- Phenomenological Theories of Crime

- Plea Bargaining

- Police Administration

- Police Cooperation, International

- Police Discretion

- Police History

- Police Militarization

- Police Misconduct

- Police, Race and the

- Police Use of Force

- Police, Violence against the

- Policing, Body-Worn Cameras and

- Policing, Broken Windows

- Policing, Community and Problem-Oriented

- Policing Cybercrime

- Policing, Evidence-Based

- Policing, Intelligence-Led

- Policing, Privatization of

- Policing, Proactive

- Policing, School

- Policing, Stop-and-Frisk

- Policing, Third Party

- Polyvictimization

- Positivist Criminology

- Pretrial Detention, Alternatives to

- Pretrial Diversion

- Prison Administration

- Prison Classification

- Prison, Disciplinary Segregation in

- Prison Education Exchange Programs

- Prison Gangs and Subculture

- Prison History

- Prison Labor

- Prison Visitation

- Prisoner Reentry

- Prisons and Jails

- Prisons, HIV in

- Private Security

- Probation Revocation

- Procedural Justice

- Property Crime

- Prosecution and Courts

- Prostitution

- Psychiatry, Psychology, and Crime: Historical and Current ...

- Psychology and Crime

- Public Criminology

- Public Opinion, Crime and Justice

- Public Order Crimes

- Public Social Control and Neighborhood Crime

- Punishment Justification and Goals

- Qualitative Methods in Criminology

- Queer Criminology

- Race and Sentencing Research Advancements

- Race, Ethnicity, Crime, and Justice

- Racial Threat Hypothesis

- Racial Profiling

- Rape and Sexual Assault

- Rape, Fear of

- Rational Choice Theories

- Rehabilitation

- Religion and Crime

- Restorative Justice

- Risk Assessment

- Routine Activity Theories

- School Bullying

- School Crime and Violence

- School Safety, Security, and Discipline

- Search Warrants

- Seasonality and Crime

- Self-Control, The General Theory:

- Self-Report Crime Surveys

- Sentencing Enhancements

- Sentencing, Evidence-Based

- Sentencing Guidelines

- Sentencing Policy

- Sex Offender Policies and Legislation

- Sex Trafficking

- Sexual Revictimization

- Situational Action Theory

- Social and Intellectual Context of Criminology, The

- Social Construction of Crime, The

- Social Control of Tobacco Use

- Social Control Theory

- Social Disorganization

- Social Ecology of Crime

- Social Learning Theory

- Social Networks

- Social Threat and Social Control

- Solitary Confinement

- South Africa, Crime and Justice in

- Sport Mega-Events Security

- Stalking and Harassment

- State Crime

- State Dependence and Population Heterogeneity in Theories ...

- Strain Theories

- Street Code

- Street Robbery

- Substance Use and Abuse

- Surveillance, Public and Private

- Sutherland, Edwin H.

- Technology and the Criminal Justice System

- Technology, Criminal Use of

- Terrorism and Hate Crime

- Terrorism, Criminological Explanations for

- Testimony, Eyewitness

- Therapeutic Jurisprudence

- Trajectory Methods in Criminology

- Transnational Crime

- Truth-In-Sentencing

- Urban Politics and Crime

- US War on Terrorism, Legal Perspectives on the

- Victimization, Adolescent

- Victimization, Biosocial Theories of

- Victimization Patterns and Trends

- Victimization, Repeat

- Victimization, Vicarious and Related Forms of Secondary Tr...

- Victimless Crime

- Victim-Offender Overlap, The

- Violence Against Women

- Violence, Youth

- Violent Crime

- White-Collar Crime

- White-Collar Crime, The Global Financial Crisis and

- White-Collar Crime, Women and

- Wilson, James Q.

- Wolfgang, Marvin

- Women, Girls, and Reentry

- Wrongful Conviction

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.66.14.133]

- 185.66.14.133

Introduction to Criminal Investigation: Processes, Practices and Thinking

(7 reviews)

Rod Gehl, Justice Institute of British Columbia

Darryl Plecas, University of the Fraser Valley

Copyright Year: 2017

Publisher: BCcampus

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Ann Koshivas, Professor, North Shore Community College on 11/29/22

I am excited that there is a book in the OER library on criminal investigations. The principles of criminal investigation are well described and it is easy to read and understand. It is a comprehensive book for a community college criminal... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

I am excited that there is a book in the OER library on criminal investigations. The principles of criminal investigation are well described and it is easy to read and understand. It is a comprehensive book for a community college criminal investigations course. There are some parts that might be confusing because the text is based on Canadian law but the general principles are explained well and applicable to the US as well.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

As far as I can tell the book is accurate but I am not as familiar with Canadian Law and case precedents so I cannot speak as to those aspects of the book. From what I can tell, the book is accurate.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

It is a relatively new book but the law frequently changes so it will need to be updated. In addition, technological advances as they relate to criminal investigations are constantly being made so the book will need to be updated based on that as well.

Clarity rating: 5

The text is easy to read and well organized.

Consistency rating: 5

There are no issues with consistency. The book is consistent in terns of use of terminology and framework.

Modularity rating: 5

This book could easily be used to assign specific chapters. Each chapter stands alone but the content follows a logical manner in its explanation of criminal investigations.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

This book is well organized.

Interface rating: 5

The interface was fine. There was nothing confusing or distracting. It was well organized and easy to read.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

I found no major problems with grammar. The text was understandable and easy to read.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

There was nothing culturally offensive about this book.

The length of this book makes it appealing for an introductory course in criminal investigations. The author covers the areas thoroughly and is concise.

Reviewed by Richard Riner, Assistant Professor of Criminal Justice/ Criminology, Buena Vista University on 12/16/21

This is a short text, 203 pages versus 519 pages for the book I am currently using for the Criminal Investigations course. It covers the basics, but that is about all it does. The book takes a very broad look at the investigative process, which... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 3 see less

This is a short text, 203 pages versus 519 pages for the book I am currently using for the Criminal Investigations course. It covers the basics, but that is about all it does. The book takes a very broad look at the investigative process, which makes it appropriate for those with no formal introduction into police work or investigations, but for those who are familiar with the process and might be looking for an in-depth examination of specific issues that can occur within the scope of an investigation, this book does not seem to be intended for that purpose. For example, a death investigation is different enough in nature and procedure that most texts devote a chapter to examining the inherent complexities and procedural challenges that accompany the investigation into the death of another human being. This book discusses major cases, and while death investigations certainly fall within that category, there is not a lot of material devoted to them, and that material is under the topic of Forensics.

Content Accuracy rating: 4

The book was written by and for students in Canada, while my background in law enforcement in the United States. However, the fact that many current and former law enforcement officials were consulted for the creation of this book lead me to believe that form a policy and procedure standpoint the book is accurate. In order to do due diligence for this section, I researched Canadian procedures (a very educational exercise) and found everything in the book to be accurate.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 4

Because the book is written from a broader frame of reference, it's utility will outlast many books in the field. Criminal Justice is an ever-changing field, and the more specific the material the more susceptible it is to changes in the landscape with regard to policy and procedure. By staying broad in scope the book discusses issues and practices that have relevant for many years and will remain so for the foreseeable future. This book will age well.

The book is written in a straightforward language without a heavy reliance on jargon. The cases cited are not what I am used to being the book was written essentially for a Canadian audience, but the explanation of the importance and relevance of the cases would be easily understood. Anyone with an interest in investigations would be able to read this book and understand the message of the authors.

Consistency rating: 4

The voice in which the book was written remains consistent throughout. The terms used to refer to the various concepts or practices are such that once a person understands them they will be able to apply them later in the text to aid in understanding later concepts.

The text is broken down into chapters, as most texts are, but them the authors have further broken the text down into topics within each chapter. This makes locating a passage of text easily done. From an instructor stand point this is a feature I would find especially useful during the presentation of textbook material in class. Having the chapters broken down in this manner will make the task of learning easier for students as well.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 3

When teaching about the process of a criminal investigation, I find it helpful to address topic in the order that an investigator is likely to deal with them when carrying out an investigation, beginning with the initial response to the scene of the crime, and ending with testimony during the trial. This text is not organized in such a way. The order in which topics are presented is not inherently confusing, but for someone who "walks" students through the process means there would be a fair amount of jumping back and forth between chapters to approach the material chronologically.

There were no issues with navigating the book. I downloaded a PDF of the text so it could accessed offline. And while there not active links in the table of contents that a person could click to go directly to a specific chapter, finding a particular passage or topic was fairly easy. The charts that accompany the text were clear both with regard to the quality of the image and clarity of the concepts. There were not a great deal of photos in the text, perhaps only one of a photo array, but it was a good quality photo.

Grammatical Errors rating: 4

I did not notice issues with grammar within the text.

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

Since the text was created for a Canadian audience, I may not be the most qualified person to judge the cultural relevance if this particular text. However, I did not find any material that I would deem inappropriate of offensive. This text deals with material and incidents that can be upsetting or shocking to people, and does so in a manner that would not offensive to readers.

Overall, this could be a useful and instructive text for the right audience. Outside of Canada, its potential utility lessens. The text has some very good characteristics, which have been described earlier, and some that could be improves in later iterations of the text.

Reviewed by Graham Rankin, Visiting Assistant Professor, Chemistry, Western Oregon University on 7/29/21

There are extensive references including legal citations for Canadian Supreme Court decisions, and an an excellent list of study questions with answers at the end of the text. However, there is no glossary or index included which makes it more... read more

There are extensive references including legal citations for Canadian Supreme Court decisions, and an an excellent list of study questions with answers at the end of the text. However, there is no glossary or index included which makes it more difficult to find the definition of a term or individual pages where a topic is covered.

Appears to be fairly accurate. I am not familiar with Caradon law so I am assuming these sections are accurate. Because the Forensic Science chapter is very superficial some aspects, while not inaccurate, are incomplete. For instance, Ballistics is considered outmoded and Firearms Identification is preferred. Accelerant and Arson are discouraged from use as Fire Debris Analysis, Suspicious Fire and Ignitable Liquid Determination are the recommended terms. Only the jury can determine if the presence of an ignitable liquid was used by the accused as an accelerant in the commission of the crime of arson. Also Bite Mark Evidence is now considered pseudoscience and may not be presented in court.

Publication date is 2016 which is reasonably recent, however an updated edition should be considered in light of new developments in analysis of trace evidence, DNA genealogical matching, and digital evidence, especially cell phone tracing of a suspect's movements.

Clarity rating: 4

Generally very clear, except for the too brief Forensic Science chapter. Also the correct packaging of evidence needs to be included as the uniformed officer may be tasked with this at the crime scene.

With the exception of Chapter 10 it is very consistent.

Each chapter is divided into Topics with study questions at the end of each chapter.

Very good. Example forms for Crime Scene management and Evidence log are included.

Interface rating: 4

Scenarios could be expanded to encourage critical thinking by requiring the reader to formulate a hypothesis based on evidence, the test that hypothesis.

none noted.

The importance of photo and line-up procedures to include same race and general description is important for eye witness identification. Cultural issues were discussed in light of interviewing witnesses and suspects.

This text is intended for training police officers who may be involved in crime scene investigation and interviewing suspects and witnesses. In that respect it does a very good job in developing a mindset for the officer to follow in the course of his/her duties. The major downside is this is a Canadian publication and thus will need considerable additional lecture and written information relating to US federal and state legal issues especially Chapter 2. While many of the aspects of rights of the suspect are common, the legal framework and court cases will be different. The overall approach includes case scenarios and study questions at the end of each chapter. Aside from those unique to Canadian law, these are excellent and could be used in a Crime Scene Investigation course in a Criminal Justice department. Some topics in crime scene security, collection and preservation of evidence could be included in introductory courses in Forensic Science. Chapter 10 is the only chapter relating directly to Forensic Science. Some topics like Forensic Pathology are fairly detailed whereas Forensic Chemistry is a short paragraph, mostly a listing of areas of analysis, i.e. fire debris analysis, drug analysis, toxicology. As a result this text would be unsuitable as the sole text for even an Introduction to Forensic Science course.

Reviewed by paul Zipper, Adjunct Faculty, Northern Essex Community College on 4/15/21

The Text was written utilizing Canadian law. This became problematic when addressing legal concepts in the US. There was no index or glossary of terms. The text would have benefited with an index and glossary of terms at the end. read more

The Text was written utilizing Canadian law. This became problematic when addressing legal concepts in the US. There was no index or glossary of terms. The text would have benefited with an index and glossary of terms at the end.

Content Accuracy rating: 3

The major investigative steps in the book was accurate. However when delving deeper into the text, it was clear Canadian terminology and US terminology and laws are different and don't mesh seamlessly. There are minor spelling nuances between the US and Canada. We use the term "offense" Canadians use "offence" as an example.

The 11 chapters were organized and hit the major areas in Criminal Investigation. Necessary updates can fit into the current template.

Clarity rating: 1

The major investigative step are well written. However Canadian Jargon/laws/terminology do not translate into concepts found in US law.

The terminology and framework are consistent- yet not applicable to what we do in the US

Modularity found in this course is a strength. Having used the text the last several semesters, it is easy to use with a traditional 14 week semester. It also covers the major concepts in a manner that is not overwhelming to students. Each week of the semester a major concept is covered and additional case studies and article are utilized to support the chapter we are covering.

The book is well organized. It takes the students through a traditional investigative flow. It has a strong introduction and covers the necessary preliminary steps and investigator/student would need to know before moving on to the next one.

The text is free of interface issues; that being said the text would be enhanced by adding some images and charts to enhance the materials.

Minor grammatical errors

I found no material in the text that would in any way be considered insensitive or offensive.

I think this is an excellent OER. It is well organized and covers major investigative steps in an organized fashion. The major downside is the audience it was written for are Canadian Law Enforcement Officers. I am teaching college students in Massachusetts, USA. A majority of the investigative steps and concepts are transferrable to the US. However, Canadian law and criminal procedure are different than US Federal law and the laws in each of our 50 states and territories. This text works with supplemental materials from the jurisdiction it is taught in being inserted. The instructor needs to point out the differences during class discussion.

Reviewed by William Powers, Adjunct Faculty, Bristol Community College on 5/29/20

Comprehensive instructions from first responding Officer to crime scene preservation, documentation, interviews and interrogation plus (Canadian) legal aspects. read more

Comprehensive instructions from first responding Officer to crime scene preservation, documentation, interviews and interrogation plus (Canadian) legal aspects.

Written in a straight forward, unbiased, usually step by step progression.

Text is based on Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, so legal aspects are not likely to drastically change. Text can be easily edited and updated for changes and new rulings in case law.

Wording is clear, minimal use of technical terminology. The only thing I had to research was the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms for comparison to American Constitution/Bill of Rights.

Proper use of terminology, some easily understood Canadian phrasing.

Book is properly divided by chapter and sub-divided to explain more detailed subject matter.

Good progression of subject matter from Intro through legal aspects to strategic organization and tactical use of crime scene protocols.

The few charts in the book were clear and easily understood. No distortion.

Grammatical Errors rating: 3

Some grammatical and punctuation errors scattered throughout the book. Ch. 7 Topic 2 Witness Types became confusing grammatically. Poorly worded in identifying direct, indirect, circumstantial evidence and witnesses. Ch 8 Note Taking. A quote (?) was opened with parentheses, parentheses were never closed.

Examples were non-offensive.

This text will be useful to a Canadian instructor and classes of prospective Police Officers, especially those that intend to pursue careers in criminalistics. The heavy but necessary reliance on the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms limits the books usefulness in other countries. Officers in the United States will be unnecessarily confused by the mixture of Canadian rights and the American Bill of Rights/Constitution. (This reviewer is from the U.S.) I myself will explore the use of Ch 8 as a quality example of proper crime scene security. The chapter shows how a first responding Officer should establish proper limited access to the crime scene, how to use an Officer assigned to maintaining a Crime Scene Security Log to limit access to and document egress times at a scene, and use of an Exhibit Log by a Forensics team supervisor to protect evidence integrity.

Reviewed by Robert Engvall, Professor, Roger Williams University on 11/5/19

This book provides a comprehensive look at introductory criminal investigation. It does a nice job of laying a proper foundation through introducing basic concepts leading through to chapters on crime scene management and forensic sciences. read more

This book provides a comprehensive look at introductory criminal investigation. It does a nice job of laying a proper foundation through introducing basic concepts leading through to chapters on crime scene management and forensic sciences.

This book is entirely accurate in its portrayal of criminal investigation.

This book is particularly relevant given today's increasingly complicated criminal justice climate. Criminal investigations are under increased scrutiny (appropriately so) and this book introduces that important new reality.

This book is clear, concise, valuable to the reader.

This book provides consistency throughout.

Each chapter provides its own information and could easily stand alone as a section of study. The context is set appropriately in the beginning of the book and some basic concepts follow leading through to more complicated crime scene management.

Each chapter stands alone, and is clearly organized. The flow is appropriate as the book takes the reader from context to basics to more complicated and reality based principles.

The book is easy to read, easy to look at, well organized.

Grammar is fine.

The book is appropriate for today's world.

This book truly does provide a solid foundation for a criminal investigation student. It would be of value to any undergraduate criminal investigation course.

Reviewed by Michael Buerger, Professor of Criminal Justice, Bowling Green State University, Ohio on 2/1/18

The text under review is written for Canadian investigators, and rests on Canadian law and case precedents. That limits its applicability to the American market, and in some ways limits the value of an assessment by an American reviewer. Many... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

The text under review is written for Canadian investigators, and rests on Canadian law and case precedents. That limits its applicability to the American market, and in some ways limits the value of an assessment by an American reviewer. Many sections do not have direct applicability, despite the general similarities between the two systems. Even though there are clear parallels in the legal systems, Canadian case law under a national charter will not have broad applicability in the United States context. State laws, federal appellate districts, and Supreme Court decisions are all operant, and the applicable legal rules may differ between jurisdictions when there are no federal precedents (the Scenario #2 domestic violence example on page 53 is such an example, for instance). The overview in Chapter 1 is excellent, and can be applied equally to criminal investigations in any democratic context. Chapter 2’s discussion of “discretion” is a good example of that adaptability, for instance: the overall effect of the first two chapters is positive enough to make me wish there could be an American version.

The approach taken by the authors is a sensible and much-needed addition to the presentation of criminal investigations. Distinguishing between investigative tasks and investigative thinking is a recurring thematic guide, and it is articulated well throughout the book. Though the distinction might be made more explicitly, the authors recognize that criminal investigations begin with the arrival of the first responding unit, almost always a uniformed officer rather than an investigator, and they incorporate that perspective throughout. The roles described on page 13 are equally applicable to Canadian and U.S. criminal justice personnel.

Not all of the examples are as useful as they might be. The example on page 36 – “I really need some money. I’m going to rob that bank tomorrow.” – is far more explicit than the type of circumstantial evidence investigators are likely to encounter. While the statement is useful, it is unrealistically specific: improvements might include the addition of variations on the theme of such utterances, such as: “I really need some money. Maybe I should rob a bank” and “I really, really need money. I’m desperate.” The greater ambiguity embedded in those statements is a greater test of the thinking discipline that the authors promote.

Page 43: the issue of consent may be that simple in Canada, but American cases rest on whether or not the person giving consent has authority to do so: cohabitants, roommates with specific areas of privacy vs. general-use spaces, landlords rather than tenants, and similar variations are not addressed here.

The distinction between Tactical and Strategic responses is a valid one, but it is dragged out a bit more than it needs to be on pp. 48-51; it is laborious reading, leaning to the tendentious. The concept is clear, but the explanation drags. One of the issues related to that distinction is the role of first-responding patrol officers, and subsequent follow-up investigation by detectives

The discussion of the stabbing incident that occupies pages 55-57 is important for establishing the “step-down” requirement when an exigent circumstances scene is brought under control. It is described in Canadian terms, but has American analogs.

The presentations focus more on philosophy than technique, and the links between the two are not consistent throughout. While the overview of forensic evidence is a good introductory treatment, I expected at least some reference to collection techniques, since the lab work is dependent upon crime scene work.

I cannot speak to the accuracy of the Canadian legal components, but the elements that apply to the fundamental of the work are sound.

Relevance and longevity should be good. Changes in law, and changes in or addition to the forensic techniques will require periodic updating, but that should be accomplished easily.

The writing is clear, although repetitive in some places, leaning to the tendentious in a few spots. My only real concern would be that the some readers might get lost in the philosophy of thinking, to the detriment of understanding the associated techniques.

Consistency of approach and terminology, and associated linkages in different sections, is good.

Modularity rating: 4

The modules are a strength of the book; my only criticism is that they are more uneven in their content than I would expect. A number of one-short-paragraph modules are ripe for at least some further development.

The text is clear, and easy to follow.

I experienced no interface problems at all.

Allowing for the different systems of punctuation, the book is error-free in terms of grammar. There are some annoying proofreading errors that stand out, however: Page 62: a comma rather than a period at the end of the second sentence of the “Common Error #3” paragraph. Page 65: redundant “situation” in the third paragraph (lower case followed by a capitalized Boldface). Page 82, final paragraph: “articles of evid. . . ase” are proofreading errors Page 92: Need a space between “crime.” and “Understanding” Page 120, third line of the “Like photo lineups” paragraph: the semi-colon should be a comma. A comma after “suspect” in the second line would help clarify the subordinate clause issue.

Cultural references are mostly absent, and for good reason, I think. They are a larger element in investigations, more fragmented in their application, and deserve separate, free-standing treatment. I saw no references that raised red flags for offensive content.

The first “Interviewing” paragraph at the bottom of page 123, carrying over to page 124, begins with the premise that “In fact, the person is not even definable as a suspect at this point,” but immediately shifts to a previously-discussed point (perpetrators acting as witnesses or reporters in order to deflect suspicion) and remains on that point to the end. Far more persons are interviewed who do not fit this category than are those who are, and the narrow focus on “suspect” for this portion is disconcerting.

The main focus of the chapter is on offenders, which at some point the investigation must be, but the broader preliminary interview phases need better development. Chapter 7 deals more with typologies than techniques, so a broader treatment of non-suspect witness interviews (and recontact interviews) would be helpful.

Table of Contents

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Some Important Basic Concepts

- Chapter 3: What You Need To Know About Evidence

- Chapter 4: The Process of Investigation

- Chapter 5: Strategic Investigative Response

- Chapter 6: Applying the Investigative Tools

- Chapter 7: Witness Management

- Chapter 8: Crime Scene Management

- Chapter 9: Interviewing, Questioning, and Interrogation

- Chapter 10: Forensic Sciences

- Chapter 11: Summary

Ancillary Material

About the book.

Introduction to Criminal Investigation, Processes, Practices, and Thinking is a teaching text designed to assist the student in developing their own structured mental map of processes, practices, and thinking to conduct criminal investigations.

Delineating criminal investigation into operational descriptors of tactical-response and strategic response while using illustrations of task-skills and thinking-skills, the reader is guided into structured thinking practices. Using the graphic tools of a “Response Transition Matrix”, an “Investigative Funnel”, and the “STAIR Tool”, the reader is shown how to form their own mental map of investigative thinking that can later be articulated in support of forming their reasonable grounds to believe.

Chapter 1 introduces criminal investigation as both a task process and a thinking process. This chapter outlines these concepts, rules, and processes with the goal of providing practical tools to ensure successful investigative processes and practices. Most importantly, this book informs the reader how to approach the investigative process using “investigative thinking.”

Chapter 2 illustrates investigation by establishing an understanding of the operational forum in which it occurs. That forum is the criminal justice system and in particular, the court system. The investigative process exists within the statutory rules of law, including the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and case law rulings adjudicated by the courts. Considering the existence of these conditions, obligations, and case law rules, there are many terms and concepts that an investigator needs to understand to function appropriately and effectively within the criminal justice system. The purpose of this chapter is to introduce some of the basic legal parameters and concepts of criminal justice within which the criminal investigation process takes place.

Chapter 3 describes the functions and terms of “evidence”, as they relate to investigation. This speaks to a wide range of information sources that might eventually inform the court to prove or disprove points at issue before the trier of fact. Sources of evidence can include anything from the observations of witnesses to the examination and analysis of physical objects. It can even include the spatial relationships between people, places, and objects within the timeline of events. From the various forms of evidence, the court can draw inferences and reach conclusions to determine if a charge has been proven beyond a reasonable doubt.

Considering the critical nature of evidence within the court system, there are a wide variety of definitions and protocols that have evolved to direct the way evidence is defined for consideration by the court. In this chapter, we look at some of the key definitions and protocols that an investigator should understand to carry out the investigative process.

Chapter 4 breaks investigation down into logical steps, establishing a progression that can be followed and repeated to reach the desired results. The process of investigation can be effectively explained and learned in this manner. In this chapter the reader is introduced to various issues in the progression that relate to the process of investigation.

Chapter 5 examines the operational processes of investigation. In this chapter we introduce the three big investigative errors along with graphic illustrations of “The Investigative Funnel” and the “S T A I R Tool” to illustrate how each of these concepts in the investigative progression.

Chapter 6 provides the reader the opportunity to work through some investigative scenarios using the S T A I R Tool. These scenarios demonstrate the investigative awareness required to transition from the tactical investigative response to the strategic investigative response. Once in the strategic response mode the reader is challenged to practice applying theory development to conduct analysis of the evidence and information to create an investigative plan.

This chapter presents two investigative scenarios each designed to illustrate different steps of the S T A I R tool allowing the student to recognize both the tactical and the strategic investigative responses and the implications of transitioning from the tactical to the strategic response.

Chapter 7 illustrates the investigative practices of witness management. Witness statements will assist the investigator in forming reasonable grounds to lay a charge, and will assist the court in reaching a decision that the charge against an accused person has been proved beyond a reasonable doubt.

It is important for an investigator to understand these practices as they allow an investigator to evaluate witnesses and collect witness evidence that will be acceptable to the courts.

Chapter 8 describes crime scene management skills. These skills are an extremely significant task component of investigation because evidence that originates at the crime scene will provide a picture of events for the court to consider in its deliberations. That picture will be composed of witness testimony, crime scene photographs, physical exhibits, and the analysis of those exhibits, along with the analysis of the crime scene itself. From this chapter, the reader will learn the task processes and protocols for several important issues in crime scene management.

Chapter 9 examines the interviewing, questioning, and interrogation techniques police use to aid them in investigations. The courts expect police to exercise high standards using practices that focus on the rights of the accused person, and minimize any physical or mental anguish that might cause a false confession. In meeting these expectations, the challenges of suspect questioning and interrogation can be complex, and many police agencies have trained interrogators and polygraph operators who undertake the interrogation of suspects for major criminal cases. But not every investigation qualifies as a major case, and frontline police investigators are challenged to undertake the tasks of interviewing, questioning, and interrogating possible suspects daily. The challenge for police is that the questioning of a suspect and the subsequent confession can be compromised by flawed interviewing, questioning, or interrogation practices. Understanding the correct processes and the legal parameters can make the difference between having a suspect's confession accepted as evidence by the court or not.

Chapter 10 examines various forensic sciences and the application of forensic sciences as practical tools to assist police in conducting investigations. As we noted in Chapter 1, it is not necessary for an investigator to be an expert in any of the forensic sciences; however, it is important to have a sound understanding of forensic tools to call upon appropriate experts to deploy the correct tools when required.

Chapter 11 summarizes the learning objectives of this text and suggests investigative learning topics for the reader going forward. Many topics relative to investigative practices have not been covered here as part of the core knowledge requirements for a new investigator. These topics include:

Major Case Management Informant and confidential source management Undercover investigations Specialized team investigations

About the Contributors

Rod Gehl , is a retired police Inspector, and an instructor of criminal investigation for International Programs and the Law Enforcement Studies Program at the Justice Institute of British Columbia. These ongoing teaching engagements are preceded by 35 years of policing experience as criminal investigator and a leader of multi-agency major case management teams. From his experiences Rod has been a keynote speaker at several international homicide conferences and has assisted in the development and presentation of Major Case Management courses for the Canadian Police College. For his contribution to policing he has been conferred the Lieutenant Governor’s Meritorious Service Award for homicide investigation. Rod’s published research on the “The Dynamics of Police Cooperation in Multi-agency Investigations”, was followed by his article, titled, “Multi-agency Teams, A Leadership Challenge”, featured in the US Police Chief Magazine. Rod retains a licence as a private investigator and security consultant and continues to work with regulatory compliance agencies in both public and private sector organizations for the development of their investigative training and systems.

Darryl Plecas is Professor Emeritus at University of the Fraser Valley where he worked for 34 years, most recently holding the Senior University Research Chair (RCMP) and Directorship of the Centre for Public Safety and Criminal Justice Research. As Professor Emeritus he continues to co-author work with colleagues and supervises graduate students. He also serves as Associate Research Faculty at California State University – Sacramento, and as an annually invited lecturer to the Yunnan Police College in Kunming, China. He is the author or co-author of more than 200 research reports, international journal articles, books, and other publications addressing a broad range public safety issues. He is a recipient of numerous awards, including UFV’s Teaching Excellence Award, the Innovative Excellence in Teaching, Learning and Technology Award from the International Conference on College Teaching and Learning, the Order of Abbotsford, the CCSA Award of Excellence, and the British Columbia Lieutenant Governor’s Award for Public Safety. His most recent co-authored book “Evidenced Based Decision Making for Government Professionals” was awarded the 2016 Professional Development Award from the Canadian Association of Municipalities.

Contribute to this Page

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Forensic Sci Int Synerg

Psychological contributions to cold case investigations: A systematic review

This article presents a systematic review of the available literature on ‘what works’ in cold case investigations, with a specific focus on psychological evidence-based research. Long-term unsolved and cold cases present their own unique set of challenges, such as lack of hard evidence, recall accuracy, and witness credibility. Therefore, this review provides a collated base of research regarding preventative methods and investigative tools and techniques developed to highlight gaps in the literature and inform best practice in cold case investigations. The review features victim and crime characteristics that may contribute to a case becoming cold and displays contributing factors to cold case clearance. Although promising, at present, psychological research in this field is insufficient to inform evidence-based guidance. Future research should aim to explore the wider psychological and criminal justice-based literature (e.g., memory retrieval and cognitive bias) to investigate what could be applicable to cold case investigations.

1. Introduction

Over the past couple of decades, there has been an increasing fascination with cold cases in popular culture. We see this in the emergence of true crime podcasts, documentaries, best-selling books, and even CrimeCon, an annual convention for true crime fans hosted in various countries [ 75 ]. Although we are generally more aware of these types of cases, currently there is no clear, universal definition of a ‘cold case’ [ 2 , 18 ]. In the UK, a ‘long-term case’ is defined as one that is open for twenty-eight days or longer [ 24 ]. Whereas a ‘cold’ case is often used to describe a case which has not been cleared by arrest or prosecution [ 14 ]; however, there is no specified point in time whereby an unsolved long-term case becomes a cold case. With this in mind, it is generally recognized that a case becomes cold when it is deemed that no further progress can be made (i.e., when all viable leads have been exhausted [ 16 ]). This effectively recategorizes the case from a long-term active to a long-term inactive, or cold, case.

It is difficult to estimate the number of cases that are unsolved, and thus deemed cold. However, this figure is likely to be substantial. For example, in the United States, The Murder Accountability Project reports 34% (roughly 331,000) of homicides reported between 1965 and 2020 as unsolved [ 67 ]. Similarly, in England and Wales, 33% of all initially recorded homicides between April 2018 and March 2019 saw no suspects charged [ 44 ]. These figures demonstrate a high proportion of homicide cases likely to go cold. However, in the whole category of cold cases there is a breadth of other crimes that must be considered.

Research has ascertained that long-term missing person inquiries are an important contributor to cold cases [ 9 , 78 ]. In fact, it is estimated that in the United Kingdom there are over 5000 unsolved missing person cases over one year old and over 1000 unidentified body cases [ [58] , [65] ]. In addition, although sexual assault is one of the most common violent offenses [ 21 ], it is also one of the most underreported and most difficult to prosecute [ 15 ], leading to many reported cases remaining unsolved and more recently, an influx of delayed allegations. Most recent figures from the Home Office and the Ministry of Justice show a decline in the rate of resolution for these cases, with less than 2% of rape cases resulting in suspects being summonsed or charged [ 12 ]. Thus, although we are unable to provide a singular number that defines how many long-term and cold cases exist, it is evident that these cases form a large proportion of police investigations.

Compared to current and active investigations, cold cases present a unique set of challenges to investigators. New investigative leads are needed, but they are often time-critical and become more difficult to find as time passes [ 3 ]. Research has suggested that the framing of a cold case as being one that is difficult, if not impossible, to solve, can create a cognitive response in investigators based on pessimism [ 74 ]. This mindset can in turn have a detrimental impact on the motivation and effort to continue searching for more leads, resulting in unfruitful outcomes. Exacerbating this further, many police forces are under-resourced due to budget cuts, meaning that cases are prioritized according to their likelihood of resolution, with cold cases naturally scoring lower on such prioritization matrices [ 31 , 57 , 89 ].

In many criminal investigations, witness accounts play a central role in informing the police about what happened and who was involved [ 37 ]. It is therefore important to obtain reliable information promptly, that is sufficiently detailed, to develop investigative lines of enquiry that ultimately help find, arrest, and bring perpetrators to justice. Psychological research has shown that the quality of witness accounts is time-critical [ 45 ]. As the delay increases, so too does the likelihood of forgetting, meaning that potentially critical leads from witnesses become less available over time. The passing of time can also pose a serious threat to recall accuracy, as there is greater opportunity for a witness's memory to be contaminated by inaccurate information encountered between the time of the event and the time of providing an account to the police [ 32 , 59 ]. Exposure to post-event information from co-witnesses, friends, family, local or national news, and social media, can also negatively influence a witness's original memory for what happened and who was involved [ 36 ]. Furthermore, research has shown that greater emotion can increase people's susceptibility to false memories [ 49 ], suggesting that memory recall could be especially at risk of contamination from the loved ones of a cold case victim. In sum, a sizable challenge for cold-case investigators is their ability to obtain a reliable account from witnesses about a crime that happened in the past.

Although there are important obstacles to consider in cold case investigations, advances in forensic science have helped develop new methods, tools, and techniques to aid the investigation process. For example, the introduction of DNA testing was a turning point in criminal investigations, enabling suspects to be identified from biological traces such as blood, saliva, and hair [ 50 ]. More recently, genetic genealogy, using direct-to-consumer genetic testing companies such as 23andMe or AncestryDNA, has been successfully used to infer genetic relationships in both active and cold cases [ 40 ]. In recent years, psychological research has also been central to informing policy and procedures surrounding effective evidence gathering techniques such as investigative interviewing [ 62 ] and identification procedures [ 88 ]. In the context of investigative interviewing, this has led to the development of scientifically informed training and practice of core skills such as rapport building, retrieval facilitation techniques, and the use of effective questions [ 26 , 38 , 63 , 85 ]. For example, the UK based College of Policing has a ‘What Works Centre for Crime Reduction’ that collects and shares research evidence on crime reduction and supports its use in practice [ 25 ]. In short, psychological research has, and continues to, support evidence-based practice within many areas of criminal investigations. However, the current body of knowledge is yet to be collated to inform and support cold case investigations.

To understand how psychology can best contribute to the investigation of cold cases, it is imperative to start by reviewing the literature and identifying relevant empirical research. In the last few years, greater attention has been paid to how we can bridge the gap between police working on cold cases and academics researching ways to assist investigations [ 52 ], however we still know relatively little. Therefore, this article presents a systematic review of the available literature on ‘what works’ in cold case investigations, with a specific focus on psychological evidence-based research. This review is both practical and timely given the rise in the number of cold cases (34% of reported homicides between 1980 and 2000 compared to 43% of reported homicides between 2000 and 2021 [ 67 ]), and the associated challenges with cold case investigations. Furthermore, it is the first to collate, synthesize and evaluate the findings of empirical research regarding methods, investigative tools and techniques developed to prevent, solve, and inform best practice in cold case investigations.

2. Methodology

2.1. search strategy.

In January 2022, three academic databases (EThOS: e-thesis online service, PsycInfo, Web of Science) were searched to identify studies that reported on preventative methods, and investigative tools and techniques relevant to cold case investigations. The following Boolean search string was used, where all words must appear in the abstract: (“cold case*” OR “unsolved case*” OR “long-term case*” OR “long-term unsolved”) AND (“investigat*” OR “police” OR “law enforcement”). Upon finding no results in our EThOS search, we decided to exclude non-peer reviewed papers. In addition, we conducted a manual search of papers' bibliographies relevant to the topic.

2.2. Criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies

Studies were included if they examined psychologically informed preventative methods, investigative tools and/or techniques intended to prevent or improve the efficacy of cold case or long-term investigations. Both quantitative and qualitative research was included. Studies were excluded if they: (1) did not focus on cold case or long-term investigations; (2) did not come from within the field of psychology (e.g., forensic science); (3) did not include an evaluation of preventative methods, or investigative tools or techniques, and; (4) were written in languages other than English. Finally, we excluded reviews, non-peer reviewed papers, and non-empirical books and book chapters.

2.3. Search results

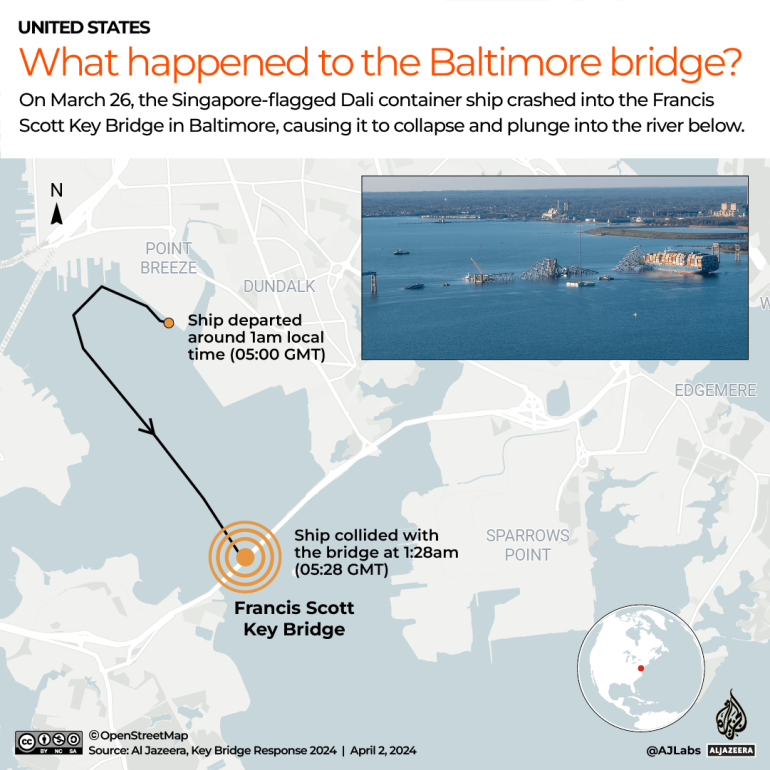

Our initial search yielded 265 results (this included 263 results from our chosen databases and two results from manual searching, no grey literature was found). Duplicates were then removed, leaving 250 articles for title and abstract screening. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart outlines the steps we followed throughout the screening process, including the number of articles we found, included, excluded and common reasons for exclusion (see Fig. 1 ).

Prisma flow chart outlining key phases.

2.4. Screening and study selection

Screening is the practice of determining eligibility by reviewing the initially identified studies against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. We used a two-step screening process that comprised: (1) title and abstract screening, and (2) full-text review. During the first step, titles that had no relevance to cold case or long-term investigations were eliminated. Abstracts were also inspected to determine whether each study reported on preventative methods, tools, and/or techniques, were psychologically informed, and were evaluated for use in cold case investigations. Studies that did not meet these criteria were removed. Studies that passed the title and abstract screening, or were deemed unclear at this stage (e.g., due to insufficient information presented in the abstract), were included in the second step of the screening process.

During the second step, articles were determined to be ineligible if the study did not investigate specific preventative methods, or investigative tools or techniques, it was not psychologically informed, and/or it did not evaluate the methods, tools, or techniques for use in cold case investigations. Twelve articles passed the second step of the screening process and were reviewed to determine their goal or focus (e.g., victim or crime characteristics) and methodological approach.

The first step of the screening process was undertaken by multiple researchers who had all received relevant training. The statistical test Cohen's Κ was performed to determine the level of agreement between researchers during the abstract screening process, and there was a substantial level of interrater agreement with the given inclusion and exclusion criteria, Κ = .681, p < .001 [ 61 ].

3. Results and discussion

Of the twelve studies that met the inclusion criteria, six were quantitative, five were qualitative, and one was mixed methods. Through a thorough review of these studies, we found that two themes of focus emerged: (1) preventative methods, 1 which comprised of six studies (five quantitative and one qualitative), and analyzed crime and victim characteristics in solved and unsolved cases to identify factors that may lead to a case going cold; and (2) investigative tools and techniques, which comprised of six studies (five qualitative and one mixed methods), and explored ‘what works’ in already cold cases.

3.1. Preventative methods

Six studies examined the solvability of cases to better understand the characteristics associated with a case being unsolved and by extension going cold. Articles in this theme examined the crime characteristics to provide insight into the qualities of the perpetrator and offense before, during, and after the crime; and/or the victim characteristics to understand what attributes of a victim are more likely to be associated with unsolved cases. Table 1 summarizes the key features of the studies included within the systematic review categorized as preventative methods. Four studies [ 17 , [19] , [20] , [21] ] examined criminal offenses with a sexual motive (sexual homicide, rape, and other sexual offenses), one focused on contract killings [ 13 ] and one [ 73 ] investigated general homicide.

Summary of key points from articles categorized within preventative methods.

3.1.1. Crime characteristics

Crimes can be split into three phases, namely pre-crime, crime, and post-crime. These phases reflect the lead-up to the crime, the crime itself, and the events after the crime, respectively. Given the complexity of the topic, most studies provided insight on more than one of these phases.

With regards to the pre-crime phase, Chopin et al. [ 21 ] examined behaviors that rape offenders utilize to avoid police detection and found that the likelihood of a case being solved increased if the victim was initially targeted by the offender and the offender used a ruse or con to approach the victim. In contrast, they found that the case was more likely to remain unsolved when the victim and offender were strangers, and the offender used a surprise attack. Chiu and Leclerc [ 19 ] performed a regression and conjunctive analysis to identify predictors of solved and unsolved sexual crimes. They discovered that the offender consuming alcohol or drugs prior to the offense was strongly associated with the solvability of the case. This is presumably due to intoxication often leading to more reckless behavior and less forensic awareness (e.g., leaving more evidence and/or witnesses). Alcohol is known to impair decision-making and can lead to taking more risks [ 39 ]. Previous research has indicated that alcohol increases the solvability to a crime due to lower forensic awareness [ 6 ]. It is possible that in sexual offenses, alcohol consumption can influence arousal to a sub-optimal level, thereby impairing their forensic awareness [ 6 ]. In the context of general homicide, the presence of known pre-crime factors, such as an argument, increases the odds of a case clearance [ 73 ]. A lack of understanding of pre-crime circumstances often indicates a lack of information or evidence. An argument before a homicide has taken place would, for example, have given a viable lead for the police to follow in the beginning stages of an investigation.

Proceeding to the crime phase, Chai et al. [ 17 ] investigated body disposal patterns in sexual homicide and examined whether offender's behaviors differ between solved and unsolved cases. Identifying behavioral patterns associated with body disposal can potentially assist police investigators in narrowing down a possible suspect list by providing information about the nature of the crime, an offender's criminal experience level, and whether there might have been a relationship between the victim and the offender (see also [ 66 ]). In this study, the only crime phase variable they found associated with unsolved cases was evidence of stabbing. In other words, a case was more likely to remain unsolved when an offender stabbed their victim in a sexual homicide. Similarly, Regoeczi et al. [ 73 ] found that homicides involving a knife were solved less frequently than homicides involving physical violence using one's own extremities. Previous research has indicated that such personal weapons (i.e., hands and feet), are often characteristic of intimate partner violence [ 77 , 79 ], which is known to have higher clearance rates [ 43 ].

With regards to the location of the crime during the crime phase, Chopin et al. [ 21 ] discovered that rape cases occurring in a residence are more likely to be solved. Instead, if a rape occurs in a deserted area, outdoors, or in a parking lot, the chances of it being solved decrease. Similar findings have been reported by Regoeczi et al. [ 73 ], whereby homicides that took place in residences were more likely to be cleared. These findings could be explained by a more significant presence of potential eyewitnesses and CCTV footage within residential areas. Chiu and Leclerc and Chopin et al. discovered that if the entire offense (including contact with the victim) took place in a single location, the offender's chances of going undetected, and therefore the case not being solved, significantly increased [ [19] , [20] , [21] ]. With regards to strategies used by offenders to avoid police detection, it was discovered that, while the same number of strategies were employed by offenders for both solved and unsolved cases, cases where offenders used a condom, wore a mask, or gloves, were more likely to remain unsolved [ 21 ]. Instead, offenders who threatened the victim or disabled the victim's phone were more likely to be identified and see their cases solved.