An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

InformedHealth.org [Internet]. Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2006-.

InformedHealth.org [Internet].

In brief: what types of studies are there.

Last Update: September 8, 2016 ; Next update: 2024.

There are various types of scientific studies such as experiments and comparative analyses, observational studies, surveys, or interviews. The choice of study type will mainly depend on the research question being asked.

When making decisions, patients and doctors need reliable answers to a number of questions. Depending on the medical condition and patient's personal situation, the following questions may be asked:

- What is the cause of the condition?

- What is the natural course of the disease if left untreated?

- What will change because of the treatment?

- How many other people have the same condition?

- How do other people cope with it?

Each of these questions can best be answered by a different type of study.

In order to get reliable results, a study has to be carefully planned right from the start. One thing that is especially important to consider is which type of study is best suited to the research question. A study protocol should be written and complete documentation of the study's process should also be done. This is vital in order for other scientists to be able to reproduce and check the results afterwards.

The main types of studies are randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort studies, case-control studies and qualitative studies.

- Randomized controlled trials

If you want to know how effective a treatment or diagnostic test is, randomized trials provide the most reliable answers. Because the effect of the treatment is often compared with "no treatment" (or a different treatment), they can also show what happens if you opt to not have the treatment or diagnostic test.

When planning this type of study, a research question is stipulated first. This involves deciding what exactly should be tested and in what group of people. In order to be able to reliably assess how effective the treatment is, the following things also need to be determined before the study is started:

- How long the study should last

- How many participants are needed

- How the effect of the treatment should be measured

For instance, a medication used to treat menopause symptoms needs to be tested on a different group of people than a flu medicine. And a study on treatment for a stuffy nose may be much shorter than a study on a drug taken to prevent strokes .

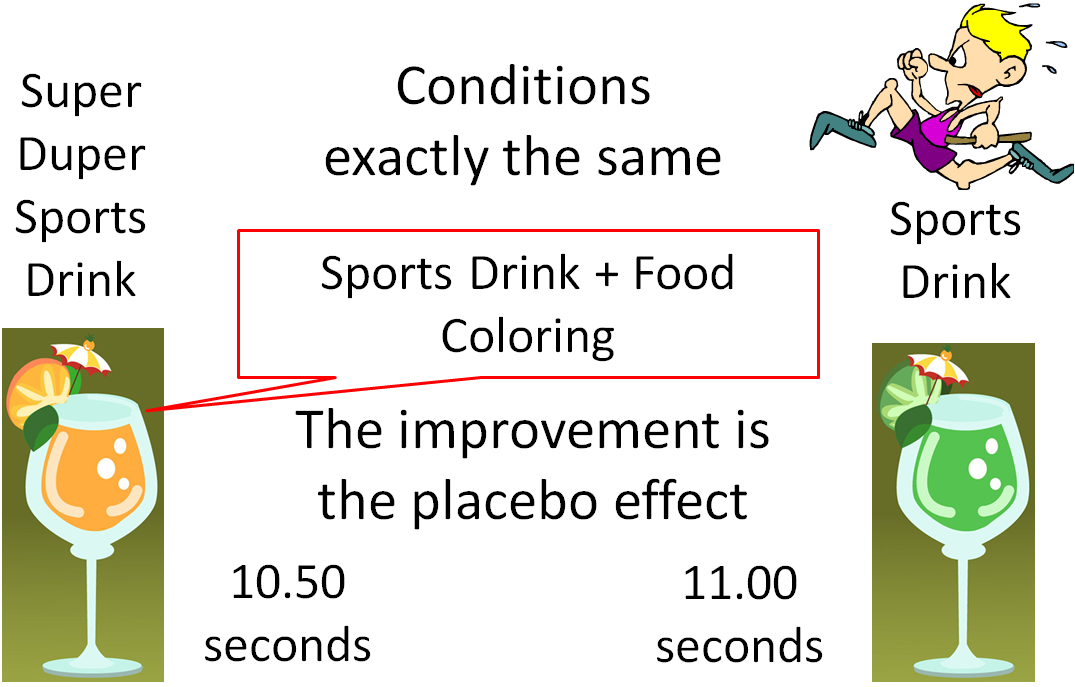

“Randomized” means divided into groups by chance. In RCTs participants are randomly assigned to one of two or more groups. Then one group receives the new drug A, for example, while the other group receives the conventional drug B or a placebo (dummy drug). Things like the appearance and taste of the drug and the placebo should be as similar as possible. Ideally, the assignment to the various groups is done "double blinded," meaning that neither the participants nor their doctors know who is in which group.

The assignment to groups has to be random in order to make sure that only the effects of the medications are compared, and no other factors influence the results. If doctors decided themselves which patients should receive which treatment, they might – for instance – give the more promising drug to patients who have better chances of recovery. This would distort the results. Random allocation ensures that differences between the results of the two groups at the end of the study are actually due to the treatment and not something else.

Randomized controlled trials provide the best results when trying to find out if there is a cause-and-effect relationship. RCTs can answer questions such as these:

- Is the new drug A better than the standard treatment for medical condition X?

- Does regular physical activity speed up recovery after a slipped disk when compared to passive waiting?

- Cohort studies

A cohort is a group of people who are observed frequently over a period of many years – for instance, to determine how often a certain disease occurs. In a cohort study, two (or more) groups that are exposed to different things are compared with each other: For example, one group might smoke while the other doesn't. Or one group may be exposed to a hazardous substance at work, while the comparison group isn't. The researchers then observe how the health of the people in both groups develops over the course of several years, whether they become ill, and how many of them pass away. Cohort studies often include people who are healthy at the start of the study. Cohort studies can have a prospective (forward-looking) design or a retrospective (backward-looking) design. In a prospective study, the result that the researchers are interested in (such as a specific illness) has not yet occurred by the time the study starts. But the outcomes that they want to measure and other possible influential factors can be precisely defined beforehand. In a retrospective study, the result (the illness) has already occurred before the study starts, and the researchers look at the patient's history to find risk factors.

Cohort studies are especially useful if you want to find out how common a medical condition is and which factors increase the risk of developing it. They can answer questions such as:

- How does high blood pressure affect heart health?

- Does smoking increase your risk of lung cancer?

For example, one famous long-term cohort study observed a group of 40,000 British doctors, many of whom smoked. It tracked how many doctors died over the years, and what they died of. The study showed that smoking caused a lot of deaths, and that people who smoked more were more likely to get ill and die.

- Case-control studies

Case-control studies compare people who have a certain medical condition with people who do not have the medical condition, but who are otherwise as similar as possible, for example in terms of their sex and age. Then the two groups are interviewed, or their medical files are analyzed, to find anything that might be risk factors for the disease. So case-control studies are generally retrospective.

Case-control studies are one way to gain knowledge about rare diseases. They are also not as expensive or time-consuming as RCTs or cohort studies. But it is often difficult to tell which people are the most similar to each other and should therefore be compared with each other. Because the researchers usually ask about past events, they are dependent on the participants’ memories. But the people they interview might no longer remember whether they were, for instance, exposed to certain risk factors in the past.

Still, case-control studies can help to investigate the causes of a specific disease, and answer questions like these:

- Do HPV infections increase the risk of cervical cancer ?

- Is the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (“cot death”) increased by parents smoking at home?

Cohort studies and case-control studies are types of "observational studies."

- Cross-sectional studies

Many people will be familiar with this kind of study. The classic type of cross-sectional study is the survey: A representative group of people – usually a random sample – are interviewed or examined in order to find out their opinions or facts. Because this data is collected only once, cross-sectional studies are relatively quick and inexpensive. They can provide information on things like the prevalence of a particular disease (how common it is). But they can't tell us anything about the cause of a disease or what the best treatment might be.

Cross-sectional studies can answer questions such as these:

- How tall are German men and women at age 20?

- How many people have cancer screening?

- Qualitative studies

This type of study helps us understand, for instance, what it is like for people to live with a certain disease. Unlike other kinds of research, qualitative research does not rely on numbers and data. Instead, it is based on information collected by talking to people who have a particular medical condition and people close to them. Written documents and observations are used too. The information that is obtained is then analyzed and interpreted using a number of methods.

Qualitative studies can answer questions such as these:

- How do women experience a Cesarean section?

- What aspects of treatment are especially important to men who have prostate cancer ?

- How reliable are the different types of studies?

Each type of study has its advantages and disadvantages. It is always important to find out the following: Did the researchers select a study type that will actually allow them to find the answers they are looking for? You can’t use a survey to find out what is causing a particular disease, for instance.

It is really only possible to draw reliable conclusions about cause and effect by using randomized controlled trials. Other types of studies usually only allow us to establish correlations (relationships where it isn’t clear whether one thing is causing the other). For instance, data from a cohort study may show that people who eat more red meat develop bowel cancer more often than people who don't. This might suggest that eating red meat can increase your risk of getting bowel cancer. But people who eat a lot of red meat might also smoke more, drink more alcohol, or tend to be overweight. The influence of these and other possible risk factors can only be determined by comparing two equal-sized groups made up of randomly assigned participants.

That is why randomized controlled trials are usually the only suitable way to find out how effective a treatment is. Systematic reviews, which summarize multiple RCTs , are even better. In order to be good-quality, though, all studies and systematic reviews need to be designed properly and eliminate as many potential sources of error as possible.

- German Network for Evidence-based Medicine. Glossar: Qualitative Forschung. Berlin: DNEbM; 2011.

- Greenhalgh T. Einführung in die Evidence-based Medicine: kritische Beurteilung klinischer Studien als Basis einer rationalen Medizin. Bern: Huber; 2003.

- Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG, Germany). General methods . Version 5.0. Cologne: IQWiG; 2017.

- Klug SJ, Bender R, Blettner M, Lange S. Wichtige epidemiologische Studientypen. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2007; 132:e45-e47. [ PubMed : 17530597 ]

- Schäfer T. Kritische Bewertung von Studien zur Ätiologie. In: Kunz R, Ollenschläger G, Raspe H, Jonitz G, Donner-Banzhoff N (eds.). Lehrbuch evidenzbasierte Medizin in Klinik und Praxis. Cologne: Deutscher Ärzte-Verlag; 2007.

IQWiG health information is written with the aim of helping people understand the advantages and disadvantages of the main treatment options and health care services.

Because IQWiG is a German institute, some of the information provided here is specific to the German health care system. The suitability of any of the described options in an individual case can be determined by talking to a doctor. informedhealth.org can provide support for talks with doctors and other medical professionals, but cannot replace them. We do not offer individual consultations.

Our information is based on the results of good-quality studies. It is written by a team of health care professionals, scientists and editors, and reviewed by external experts. You can find a detailed description of how our health information is produced and updated in our methods.

- Cite this Page InformedHealth.org [Internet]. Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2006-. In brief: What types of studies are there? [Updated 2016 Sep 8].

In this Page

Informed health links, related information.

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Recent Activity

- In brief: What types of studies are there? - InformedHealth.org In brief: What types of studies are there? - InformedHealth.org

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

Community Blog

Keep up-to-date on postgraduate related issues with our quick reads written by students, postdocs, professors and industry leaders.

Types of Research – Explained with Examples

- By DiscoverPhDs

- October 2, 2020

Types of Research

Research is about using established methods to investigate a problem or question in detail with the aim of generating new knowledge about it.

It is a vital tool for scientific advancement because it allows researchers to prove or refute hypotheses based on clearly defined parameters, environments and assumptions. Due to this, it enables us to confidently contribute to knowledge as it allows research to be verified and replicated.

Knowing the types of research and what each of them focuses on will allow you to better plan your project, utilises the most appropriate methodologies and techniques and better communicate your findings to other researchers and supervisors.

Classification of Types of Research

There are various types of research that are classified according to their objective, depth of study, analysed data, time required to study the phenomenon and other factors. It’s important to note that a research project will not be limited to one type of research, but will likely use several.

According to its Purpose

Theoretical research.

Theoretical research, also referred to as pure or basic research, focuses on generating knowledge , regardless of its practical application. Here, data collection is used to generate new general concepts for a better understanding of a particular field or to answer a theoretical research question.

Results of this kind are usually oriented towards the formulation of theories and are usually based on documentary analysis, the development of mathematical formulas and the reflection of high-level researchers.

Applied Research

Here, the goal is to find strategies that can be used to address a specific research problem. Applied research draws on theory to generate practical scientific knowledge, and its use is very common in STEM fields such as engineering, computer science and medicine.

This type of research is subdivided into two types:

- Technological applied research : looks towards improving efficiency in a particular productive sector through the improvement of processes or machinery related to said productive processes.

- Scientific applied research : has predictive purposes. Through this type of research design, we can measure certain variables to predict behaviours useful to the goods and services sector, such as consumption patterns and viability of commercial projects.

According to your Depth of Scope

Exploratory research.

Exploratory research is used for the preliminary investigation of a subject that is not yet well understood or sufficiently researched. It serves to establish a frame of reference and a hypothesis from which an in-depth study can be developed that will enable conclusive results to be generated.

Because exploratory research is based on the study of little-studied phenomena, it relies less on theory and more on the collection of data to identify patterns that explain these phenomena.

Descriptive Research

The primary objective of descriptive research is to define the characteristics of a particular phenomenon without necessarily investigating the causes that produce it.

In this type of research, the researcher must take particular care not to intervene in the observed object or phenomenon, as its behaviour may change if an external factor is involved.

Explanatory Research

Explanatory research is the most common type of research method and is responsible for establishing cause-and-effect relationships that allow generalisations to be extended to similar realities. It is closely related to descriptive research, although it provides additional information about the observed object and its interactions with the environment.

Correlational Research

The purpose of this type of scientific research is to identify the relationship between two or more variables. A correlational study aims to determine whether a variable changes, how much the other elements of the observed system change.

According to the Type of Data Used

Qualitative research.

Qualitative methods are often used in the social sciences to collect, compare and interpret information, has a linguistic-semiotic basis and is used in techniques such as discourse analysis, interviews, surveys, records and participant observations.

In order to use statistical methods to validate their results, the observations collected must be evaluated numerically. Qualitative research, however, tends to be subjective, since not all data can be fully controlled. Therefore, this type of research design is better suited to extracting meaning from an event or phenomenon (the ‘why’) than its cause (the ‘how’).

Quantitative Research

Quantitative research study delves into a phenomena through quantitative data collection and using mathematical, statistical and computer-aided tools to measure them . This allows generalised conclusions to be projected over time.

According to the Degree of Manipulation of Variables

Experimental research.

It is about designing or replicating a phenomenon whose variables are manipulated under strictly controlled conditions in order to identify or discover its effect on another independent variable or object. The phenomenon to be studied is measured through study and control groups, and according to the guidelines of the scientific method.

Non-Experimental Research

Also known as an observational study, it focuses on the analysis of a phenomenon in its natural context. As such, the researcher does not intervene directly, but limits their involvement to measuring the variables required for the study. Due to its observational nature, it is often used in descriptive research.

Quasi-Experimental Research

It controls only some variables of the phenomenon under investigation and is therefore not entirely experimental. In this case, the study and the focus group cannot be randomly selected, but are chosen from existing groups or populations . This is to ensure the collected data is relevant and that the knowledge, perspectives and opinions of the population can be incorporated into the study.

According to the Type of Inference

Deductive investigation.

In this type of research, reality is explained by general laws that point to certain conclusions; conclusions are expected to be part of the premise of the research problem and considered correct if the premise is valid and the inductive method is applied correctly.

Inductive Research

In this type of research, knowledge is generated from an observation to achieve a generalisation. It is based on the collection of specific data to develop new theories.

Hypothetical-Deductive Investigation

It is based on observing reality to make a hypothesis, then use deduction to obtain a conclusion and finally verify or reject it through experience.

According to the Time in Which it is Carried Out

Longitudinal study (also referred to as diachronic research).

It is the monitoring of the same event, individual or group over a defined period of time. It aims to track changes in a number of variables and see how they evolve over time. It is often used in medical, psychological and social areas .

Cross-Sectional Study (also referred to as Synchronous Research)

Cross-sectional research design is used to observe phenomena, an individual or a group of research subjects at a given time.

According to The Sources of Information

Primary research.

This fundamental research type is defined by the fact that the data is collected directly from the source, that is, it consists of primary, first-hand information.

Secondary research

Unlike primary research, secondary research is developed with information from secondary sources, which are generally based on scientific literature and other documents compiled by another researcher.

According to How the Data is Obtained

Documentary (cabinet).

Documentary research, or secondary sources, is based on a systematic review of existing sources of information on a particular subject. This type of scientific research is commonly used when undertaking literature reviews or producing a case study.

Field research study involves the direct collection of information at the location where the observed phenomenon occurs.

From Laboratory

Laboratory research is carried out in a controlled environment in order to isolate a dependent variable and establish its relationship with other variables through scientific methods.

Mixed-Method: Documentary, Field and/or Laboratory

Mixed research methodologies combine results from both secondary (documentary) sources and primary sources through field or laboratory research.

An abstract and introduction are the first two sections of your paper or thesis. This guide explains the differences between them and how to write them.

Statistical treatment of data is essential for all researchers, regardless of whether you’re a biologist, computer scientist or psychologist, but what exactly is it?

Scientific misconduct can be described as a deviation from the accepted standards of scientific research, study and publication ethics.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Browse PhDs Now

Stay up to date with current information being provided by the UK Government and Universities about the impact of the global pandemic on PhD research studies.

An academic transcript gives a breakdown of each module you studied for your degree and the mark that you were awarded.

Ellie is a final year PhD student at the University of Hertfordshire, investigating a protein which is implicated in pancreatic cancer; this work can improve the efficacy of cancer drug treatments.

Dr Williams gained her PhD in Chemical Engineering at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York in 2020. She is now a Presidential Postdoctoral Fellow at Cornell University, researching simplifying vaccine manufacturing in low-income countries.

Join Thousands of Students

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Research methods--quantitative, qualitative, and more: overview.

- Quantitative Research

- Qualitative Research

- Data Science Methods (Machine Learning, AI, Big Data)

- Text Mining and Computational Text Analysis

- Evidence Synthesis/Systematic Reviews

- Get Data, Get Help!

About Research Methods

This guide provides an overview of research methods, how to choose and use them, and supports and resources at UC Berkeley.

As Patten and Newhart note in the book Understanding Research Methods , "Research methods are the building blocks of the scientific enterprise. They are the "how" for building systematic knowledge. The accumulation of knowledge through research is by its nature a collective endeavor. Each well-designed study provides evidence that may support, amend, refute, or deepen the understanding of existing knowledge...Decisions are important throughout the practice of research and are designed to help researchers collect evidence that includes the full spectrum of the phenomenon under study, to maintain logical rules, and to mitigate or account for possible sources of bias. In many ways, learning research methods is learning how to see and make these decisions."

The choice of methods varies by discipline, by the kind of phenomenon being studied and the data being used to study it, by the technology available, and more. This guide is an introduction, but if you don't see what you need here, always contact your subject librarian, and/or take a look to see if there's a library research guide that will answer your question.

Suggestions for changes and additions to this guide are welcome!

START HERE: SAGE Research Methods

Without question, the most comprehensive resource available from the library is SAGE Research Methods. HERE IS THE ONLINE GUIDE to this one-stop shopping collection, and some helpful links are below:

- SAGE Research Methods

- Little Green Books (Quantitative Methods)

- Little Blue Books (Qualitative Methods)

- Dictionaries and Encyclopedias

- Case studies of real research projects

- Sample datasets for hands-on practice

- Streaming video--see methods come to life

- Methodspace- -a community for researchers

- SAGE Research Methods Course Mapping

Library Data Services at UC Berkeley

Library Data Services Program and Digital Scholarship Services

The LDSP offers a variety of services and tools ! From this link, check out pages for each of the following topics: discovering data, managing data, collecting data, GIS data, text data mining, publishing data, digital scholarship, open science, and the Research Data Management Program.

Be sure also to check out the visual guide to where to seek assistance on campus with any research question you may have!

Library GIS Services

Other Data Services at Berkeley

D-Lab Supports Berkeley faculty, staff, and graduate students with research in data intensive social science, including a wide range of training and workshop offerings Dryad Dryad is a simple self-service tool for researchers to use in publishing their datasets. It provides tools for the effective publication of and access to research data. Geospatial Innovation Facility (GIF) Provides leadership and training across a broad array of integrated mapping technologies on campu Research Data Management A UC Berkeley guide and consulting service for research data management issues

General Research Methods Resources

Here are some general resources for assistance:

- Assistance from ICPSR (must create an account to access): Getting Help with Data , and Resources for Students

- Wiley Stats Ref for background information on statistics topics

- Survey Documentation and Analysis (SDA) . Program for easy web-based analysis of survey data.

Consultants

- D-Lab/Data Science Discovery Consultants Request help with your research project from peer consultants.

- Research data (RDM) consulting Meet with RDM consultants before designing the data security, storage, and sharing aspects of your qualitative project.

- Statistics Department Consulting Services A service in which advanced graduate students, under faculty supervision, are available to consult during specified hours in the Fall and Spring semesters.

Related Resourcex

- IRB / CPHS Qualitative research projects with human subjects often require that you go through an ethics review.

- OURS (Office of Undergraduate Research and Scholarships) OURS supports undergraduates who want to embark on research projects and assistantships. In particular, check out their "Getting Started in Research" workshops

- Sponsored Projects Sponsored projects works with researchers applying for major external grants.

- Next: Quantitative Research >>

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 11:09 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/researchmethods

- Anxiety Disorder

- Bipolar Disorder

- Schizophrenia

- Adjustment Disorder

- Agoraphobia

- Antisocial Personality Disorder

- Borderline Personality Disorder

- Childhood ADHD

- Dissociative Identity Disorder

- Narcissistic Personality Disorder

- Oppositional Defiant Disorder

- Panic Attack

- Postpartum Depression

- Schizoaffective Disorder

- Seasonal Affective Disorder

- Sex Addiction

- Social Anxiety

- Specific Phobias

- Teenage Depression

- Black Mental Health

- Emotional Health

- Sex & Relationships

- Understanding Therapy

- Workplace Mental Health

- My Life with OCD

- Caregivers Chronicles

- Empathy at Work

- Sex, Love & All of the Above

- Parent Central

- Mindful Moment

- Mental Health News

- Live Town Hall: Mental Health in Focus

- Inside Mental Health

- Inside Schizophrenia

- Inside Bipolar

- ADHD Symptoms Quiz

- Anxiety Symptoms Quiz

- Autism Quiz: Family & Friends

- Autism Symptoms Quiz

- Bipolar Disorder Quiz

- Borderline Personality Test

- Childhood ADHD Quiz

- Depression Symptoms Quiz

- Eating Disorder Quiz

- Narcissim Symptoms Test

- OCD Symptoms Quiz

- Psychopathy Test

- PTSD Symptoms Quiz

- Schizophrenia Quiz

- Attachment Style Quiz

- Career Test

- Do I Need Therapy Quiz?

- Domestic Violence Screening Quiz

- Emotional Type Quiz

- Loneliness Quiz

- Parenting Style Quiz

- Personality Test

- Relationship Quiz

- Stress Test

- What's Your Sleep Like?

- Find Support

- Suicide Prevention

- Drugs & Medications

- Find a Therapist

Research 101: Understanding Research Studies

One of the secrets of science is to understand the language of science, and science’s primary language is the research study . Research studies allow scientists to communicate with one another and share results of their work. There are many different kinds of research and many varying fields of research. And although journals were designed to help professionals communicate such research findings with one another, many times professionals in one field don’t significantly interact with (or are even aware of) researchers in a different field than themselves (e.g., a neuropsychologist may not keep up on the same research findings as a neurologist). This article reviews the major types of research done in the social, behavioral and brain sciences and provides some guideposts to better evaluate the context in which to place new research.

Types of Research

The basis of a scientific research study follows a common pattern:

- Define the question

- Gather information and resources

- Form hypotheses

- Perform an experiment and collect data

- Analyze the data

- Interpret the data and draw conclusions

- Publish results in a peer-reviewed journal

While there are dozens of types of research, most research done falls into one of five categories: clinical case studies; small, non-randomized studies or surveys; large, randomized clinical studies; literature reviews; and meta-analytic studies. Studies can also occur in widely varying fields, from psychology, pharmacology and sociology (what I’ll call “behavioral and treatment studies”), to genetics and brain scans (what I’ll call “organic studies”) to animal studies. Some fields contribute results that are more instantly relevant, while others’ results may help researchers develop new tests or treatments decades from now.

Clinical Case Studies

A clinical case study involves reporting on a single case (or series of cases) that the researcher or clinician has tracked over a period of some significant time (usually months or even years). Many times, such case studies emphasize a narrative or more subjective approach, but may also include objective measures. For instance, a researcher might publish a case study about the positive effects of cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for a person with depression. The researcher measured the client’s level of depression with an objective measure such as the Beck Depression Inventory, but also describes in detail the client’s progress with specific cognitive-behavioral techniques , such as doing regular “homework” or keeping a journal of one’s thoughts.

The clinical case study is a very good research design for generating and testing hypotheses that may be used in larger studies. It is also a very good manner for disseminating the effectiveness of specific or novel techniques for individuals, or for those that may have a fairly uncommon set of diagnoses. However, generally a clinical case study’s results are not able to be generalized to a broader population. A case study is therefore of limited value to the general population.

Small Studies and Survey Research

There’s no specific criteria that differentiates a “small study” from a “large study,” but I place any non-randomized study in this category, as well as pretty much all survey research. Small studies are generally conducted on student populations (because students are often required to be a research subject for their university psychology classes), involve less than 80 to 100 participants or subjects, and often lack at least one of the core, important research components most often found in larger studies. This component can be the lack of true randomization of subjects, a lack of heterogeneity (e.g., no diversity in the population being studied), or a lack of a control group (or a relevant control group, e.g. a placebo control).

Most survey research also falls into this category, because it also lacks one of these core research components. For instance, a lot of survey research asks participants to identify themselves as having a particular problem, and if they do, then they fill out the survey. While this will almost guarantee the researchers interesting results, it’s also not very generalizable.

The upshot is that while these studies often provide interesting insights and information that can be used for future research, people shouldn’t read too much into these research findings. They are important data points in our overall understanding of the subject. When you take 10 or 20 of these data points and string them together, they should provide a fairly clear and consistent picture about the topic. If the results don’t provide such a clear picture, then there is likely more work to be done in the subject area before meaningful conclusions can be made. Literature reviews and meta-analyses (discussed below) help professionals and individuals better understand such findings over time.

Large, Randomized Studies

Large, randomized studies that draw from diverse populations and include relevant, appropriate control groups are considered the “gold standard” in research. So why aren’t they done more often? Such large studies, often done at multiple geographic locations, are very expensive to run because they include dozens of researchers, research assistants, statisticians, and other professionals as well as hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of subjects or participants. But the findings from such research are robust and can be generalized to others far more easily, so their value to research is important.

Large studies are not immune to problems found in other kinds of research. It’s just that the problems tend to have a much smaller effect, if there are any, since the number of subjects is so large and mixed (heterogeneous). When properly designed and using accepted statistical analyses, large research studies provide both individuals and professionals with solid findings that they can act upon.

Literature Reviews

A literature review is pretty much what it describes. Virtually all peer-reviewed, published research includes what might be called a “mini literature review” in its introduction. In this section of a study, the researchers review previous studies to put the current study into some context. “Research X found 123, Research Y found 456, so we hope to find 789.”

Sometimes, however, the number of studies in a particular area of study is so large and covers so many results that it’s difficult to understand exactly what our understanding is at the moment. To help give researchers a better understanding and context for future research, a literature review may be conducted and published as its own “study.” This will basically be a comprehensive, large-scale review of all studies in a particular area published within the past 10 or 20 years. The review will describe the research efforts, expand on specific findings, and may draw some general conclusions that can be gleaned from such a global review. These reviews are usually fairly subjective and are mainly for other professionals. Their use to the general public is limited and they almost never produce new findings of interest.

Meta-Analytic Studies

A meta-analysis is similar to a literature review in that it seeks to examine all previous research in a very specific topic area. However, unlike a literature review, a meta-analytic study takes the review one important step further – it actually pulls together all of the previous study’s data and analyzes it with additional statistics to draw global conclusions about the data. Why bother? Because so much research is published in many fields that it’s virtually impossible for an individual to draw any solid conclusions from the research without such a global review that pulls together all that data and statistically analyzes it for trends and solid findings.

The key to meta-analytic studies is to understand that researchers can alter the results of such a review by being particular (or not very particular) about the kinds of studies they include in their review. If, for instance, the researchers decide to include non-randomized studies in their review, they will often get different findings than if they hadn’t included them. Sometimes researchers will require certain statistical procedures to have been performed in order for the study to be included, or certain data thresholds to be met (e.g., we’ll only examine studies that had more than 50 subjects). Depending upon what criteria researchers choose to include in their meta-analysis, it will effect the results of the meta-analysis.

Meta-analytic studies, when done properly, are important contributions to our scientific knowledge and understanding. When a meta-analysis is published, it generally acts as a new foundation for other studies to build upon. It also synthesizes a great deal of previous knowledge into a more digestable Chunk of Knowledge for everyone.

Three General Categories of Research

While we’ve discussed the five general types of research in behavioral and mental health, there are also three other categories to consider.

Behavioral & Treatment Studies

Behavioral or treatment studies examine specific behaviors, treatments or therapies and see how they work on people. In psychology and sociology, most research conducted is of this nature. Such research provides direct insights into human behavior or therapeutic techniques that may be of value for treating a specific kind of disorder. This kind of research also helps us better understand a specific health or mental health concern, and how it manifests itself in a certain group of people (e.g., teenagers versus adults). This is the most “actionable” type of research – research that professionals and individuals can take action based upon its findings.

Organic Studies

Research that examines brain structures, neurochemical reactions via PET or other brain imaging techniques, gene research, or research that examines other organic structures in a human body falls under this category. In most cases, such research helps further our understanding of the human body and how it functions, but doesn’t provide immediate insight or help in dealing with a problem today, or suggest new treatments that will be readily available. For instance, researchers often publish findings about how a particular gene may be correlated with a specific disorder. While such findings may eventually lead to some sort of medical test being developed for the disorder, it may be a decade or two before a finding of this nature translates into an actual test or new treatment method.

While such research is vitally important to our eventual better understanding of how our brains and bodies function, research in this category tends not to have much importance today for people dealing with a mental disorder or mental health problem.

Animal Studies

Research is sometimes conducted on an animal to better understand how a specific organ system (such as the brain) reacts to changes, or how an animal’s behavior may be altered by specific social or environmental changes. Animal research, mostly on rats, in the 1950’s and 1960’s focused on studying animal behavior which, in psychology, led to the field of behaviorism and behavior therapy . More recently, the focus of animal studies has been on their biological makeup, to examine certain brain structures and genes related to health or mental health issues.

While certain animals have organ systems that may be very similar to human organ systems, results from animal studies are not automatically generalizable to humans. Animal studies are therefore of limited value to the general population. Research news based upon an animal study generally means any possible significant treatments from such a study are at least a decade or more away from being introduced. In many cases, no specific treatments are developed from animal studies, instead they are used to better understand how a human organ system functions or reacts to a change.

Research in the social sciences and in pharmacology is important because it helps us not only better understand human behavior (both normal and dysfunctional behavior), but also to find more effective and less time-consuming treatments to help with a person is suffering from an emotional or mental health issue.

The best kind of research – large-scale, randomized studies – are also the most rare because of their cost and the amount of resources needed to undertake them. Smaller-scale studies also contribute important data points along the way, inbetween the larger studies, while meta-analyses and literature reviews helps us gain a more global perspective and understanding of our knowledge so far.

While animal research and studies into the brain’s structures and genes are important to contributing to our overall better understanding of how our brains and bodies function, behavioral and treatment research provide concrete data that can generally be used immediately to help people improve their lives.

Last medically reviewed on May 17, 2016

Read this next

JK Rowling broke out medical science to defend her controversial stance on trans women. Responding to twitter

When we're feeling stressed, studies show that one of the best things we can do is to help someone else. Try these simple suggestions for being of…

Even before the nationwide lockdowns, there were far too many people in the U.S. with not enough to eat. The p

I suspect that when most people think about single parents, they think about single mothers. And, yes, single

In the latest example of tone-deaf celeb activism, several celebs including Julianne Moore, Sara Paulson, and

No good comes from constantly refreshing your newsfeed for the latest on COVID-19. Here are 10 things you can do that aren't related to coronavirus.

On Facebook a few days ago, a friend posted that there was no toilet paper anywhere in the town where I live.

If someone lacks food and water, we know the body will suffer. But what about when they lack a sense of belong

Are you an ABA service provider (a BCBA, BCaBA, or other clinician providing ABA services)? Does part of your

To trust someone you love is important. Otherwise, you’ll be forever doubting that person, creating serious

Research Study Types

There are many different types of research studies, and each has distinct strengths and weaknesses. In general, randomized trials and cohort studies provide the best information when looking at the link between a certain factor (like diet) and a health outcome (like heart disease).

Laboratory and Animal Studies

These are studies done in laboratories on cells, tissue, or animals.

- Strengths: Laboratories provide strictly controlled conditions and are often the genesis of scientific ideas that go on to have a broad impact on human health. They can help understand the mechanisms of disease.

- Weaknesses: Laboratory and animal studies are only a starting point. Animals or cells are not a substitute for humans.

Cross-Sectional Surveys

These studies examine the incidence of a certain outcome (disease or other health characteristic) in a specific group of people at one point in time. Surveys are often sent to participants to gather data about the outcome of interest.

- Strengths: Inexpensive and easy to perform.

- Weaknesses: Can only establish an association in that one specific time period.

Case-Control Studies

These studies look at the characteristics of one group of people who already have a certain health outcome (the cases) and compare them with a similar group of people who do not have the outcome (the controls). An example may be looking at a group of people with heart disease and another group without heart disease who are similar in age, sex, and economic status, and comparing their intakes of fruits and vegetables to see if this exposure could be associated with heart disease risk.

- Strengths: Case-control studies can be done quickly and relatively cheaply.

- Weaknesses: Not ideal for studying diet because they gather information from the past, which can be difficult for most people to recall accurately. Furthermore, people with illnesses often recall past behaviors differently from those without illness. This opens such studies to potential inaccuracy and bias in the information they gather.

Cohort Studies

These are observational studies that follow large groups of people over a long period of time, years or even decades, to find associations of an exposure(s) with disease outcomes. Researchers regularly gather information from the people in the study on several variables (like meat intake, physical activity level, and weight). Once a specified amount of time has elapsed, the characteristics of people in the group are compared to test specific hypotheses (such as a link between high versus low intake of carotenoid-rich foods and glaucoma, or high versus low meat intake and prostate cancer).

- Strengths: Participants are not required to change their diets or lifestyle as may be with randomized controlled studies. Study sizes may be larger than other study types. They generally provide more reliable information than case-control studies because they don’t rely on information from the past. Cohort studies gather information from participants at the beginning and throughout the study, long before they may develop the disease being studied. As a group, many of these types of studies have provided valuable information about the link between lifestyle factors and disease.

- Weaknesses: A longer duration of following participants make these studies time-consuming and expensive. Results cannot suggest cause-and-effect, only associations. Evaluation of dietary intake is self-reported.

Two of the largest and longest-running cohort studies of diet are the Harvard-based Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study.

If you follow nutrition news, chances are you have come across findings from a cohort called the Nurses’ Health Study . The Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) began in 1976, spearheaded by researchers from the Channing Laboratory at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, with funding from the National Institutes of Health. It gathered registered nurses ages 30-55 years from across the U.S. to respond to a series of questionnaires. Nurses were specifically chosen because of their ability to complete the health-related, often very technical, questionnaires thoroughly and accurately. They showed motivation to participate in the long-term study that required ongoing questionnaires every two years. Furthermore, the group provided blood, urine, and other samples over the course of the study.

The NHS is a prospective cohort study, meaning a group of people who are followed forward in time to examine lifestyle habits or other characteristics to see if they develop a disease, death, or some other indicated outcome. In comparison, a retrospective cohort study would specify a disease or outcome and look back in time at the group to see if there were common factors leading to the disease or outcome. A benefit of prospective studies over retrospective studies is greater accuracy in reporting details, such as food intake, that is not distorted by the diagnosis of illness.

To date, there are three NHS cohorts: NHS original cohort, NHS II, and NHS 3. Below are some features unique to each cohort.

NHS – Original Cohort

- Started in 1976 by Frank Speizer, M.D.

- Participants: 121,700 married women, ages 30 to 55 in 1976.

- Outcomes studied: Impact of contraceptive methods and smoking on breast cancer; later this was expanded to observe other lifestyle factors and behaviors in relation to 30 diseases.

- A food frequency questionnaire was added in 1980 to collect information on dietary intake, and continues to be collected every four years.

- Started in 1989 by Walter Willett, M.D., M.P.H., Dr.P.H., and colleagues.

- Participants: 116,430 single and married women, ages 25 to 42 in 1989.

- Outcomes studied: Impact on women’s health of oral contraceptives initiated during adolescence, diet and physical activity in adolescence, and lifestyle risk factors in a younger population than the NHS Original Cohort. The wide range of diseases examined in the original NHS is now also being studied in NHSII.

- The first food frequency questionnaire was collected in 1991, and is collected every four years.

- Started in 2010 by Jorge Chavarro, M.D., Sc.M., Sc.D, Walter Willett, M.D., M.P.H., Dr.P.H., Janet Rich-Edwards, Sc.D., M.P.H, and Stacey Missmer, Sc.D.

- Participants: Expanded to include not just registered nurses but licensed practical nurses (LPN) and licensed vocational nurses (LVN), ages 19 to 46. Enrollment is currently open.

- Inclusion of more diverse population of nurses, including male nurses and nurses from Canada.

- Outcomes studied: Dietary patterns, lifestyle, environment, and nursing occupational exposures that may impact men’s and women’s health; the impact of new hormone preparations and fertility/pregnancy on women’s health; relationship of diet in adolescence on breast cancer risk.

From these three cohorts, extensive research has been published regarding the association of diet, smoking, physical activity levels, overweight and obesity, oral contraceptive use, hormone therapy, endogenous hormones, dietary factors, sleep, genetics, and other behaviors and characteristics with various diseases. In 2016, in celebration of the 40 th Anniversary of NHS, the American Journal of Public Health’s September issue was dedicated to featuring the many contributions of the Nurses’ Health Studies to public health.

Growing Up Today Study (GUTS)

In 1996, recruitment began for a new cross-generational cohort called GUTS (Growing Up Today Study) —children of nurses from the NHS II. GUTS is composed of 27,802 girls and boys who were between the ages of 9 and 17 at the time of enrollment. As the entire cohort has entered adulthood, they complete annual questionnaires including information on dietary intake, weight changes, exercise level, substance and alcohol use, body image, and environmental factors. Researchers are looking at conditions more common in young adults such as asthma, skin cancer, eating disorders, and sports injuries.

Randomized Trials

Like cohort studies, these studies follow a group of people over time. However, with randomized trials, the researchers intervene with a specific behavior change or treatment (such as following a specific diet or taking a supplement) to see how it affects a health outcome. They are called “randomized trials” because people in the study are randomly assigned to either receive or not receive the intervention. This randomization helps researchers determine the true effect the intervention has on the health outcome. Those who do not receive the intervention or labelled the “control group,” which means these participants do not change their behavior, or if the study is examining the effects of a vitamin supplement, the control group participants receive a placebo supplement that contains no active ingredients.

- Strengths: Considered the “gold standard” and best for determining the effectiveness of an intervention (e.g., dietary pattern, supplement) on an endpoint such as cancer or heart disease. Conducted in a highly controlled setting with limited variables that could affect the outcome. They determine cause-and-effect relationships.

- Weaknesses: High cost, potentially low long-term compliance with prescribed diets, and possible ethical issues. Due to expense, the study size may be small.

Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews

A meta-analysis collects data from several previous studies on one topic to analyze and combine the results using statistical methods to provide a summary conclusion. Meta-analyses are usually conducted using randomized controlled trials and cohort studies that have higher quality of evidence than other designs. A systematic review also examines past literature related to a specific topic and design, analyzing the quality of studies and results but may not pool the data. Sometimes a systematic review is followed by conducting a meta-analysis if the quality of the studies is good and the data can be combined.

- Strengths: Inexpensive and provides a general comprehensive summary of existing research on a topic. This can create an explanation or assumption to be used for further investigation.

- Weaknesses: Prone to selection bias, as the authors can choose or exclude certain studies, which can change the resulting outcome. Combining data that includes lower-quality studies can also skew the results.

A primer on systematic review and meta-analysis in diabetes research

Terms of use.

The contents of this website are for educational purposes and are not intended to offer personal medical advice. You should seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The Nutrition Source does not recommend or endorse any products.

Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

Neag School of Education

Educational Research Basics by Del Siegle

Types of Research

How do we know something exists? There are a numbers of ways of knowing…

- -Sensory Experience

- -Agreement with others

- -Expert Opinion

- -Scientific Method (we’re using this one)

The Scientific Process (replicable)

- Identify a problem

- Clarify the problem

- Determine what data would help solve the problem

- Organize the data

- Interpret the results

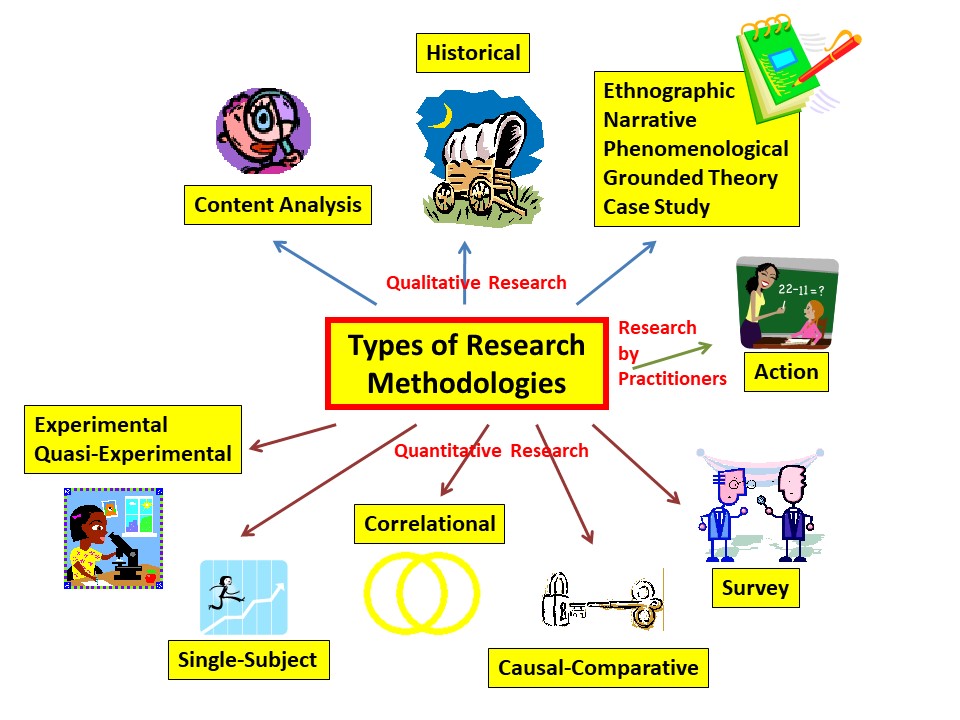

General Types of Educational Research

- Descriptive — survey, historical, content analysis, qualitative (ethnographic, narrative, phenomenological, grounded theory, and case study)

- Associational — correlational, causal-comparative

- Intervention — experimental, quasi-experimental, action research (sort of)

Researchers Sometimes Have a Category Called Group Comparison

- Ex Post Facto (Causal-Comparative): GROUPS ARE ALREADY FORMED

- Experimental: RANDOM ASSIGNMENT OF INDIVIDUALS

- Quasi-Experimental: RANDOM ASSIGNMENT OF GROUPS (oversimplified, but fine for now)

General Format of a Research Publication

- Background of the Problem (ending with a problem statement) — Why is this important to study? What is the problem being investigated?

- Review of Literature — What do we already know about this problem or situation?

- Methodology (participants, instruments, procedures) — How was the study conducted? Who were the participants? What data were collected and how?

- Analysis — What are the results? What did the data indicate?

- Results — What are the implications of these results? How do they agree or disagree with previous research? What do we still need to learn? What are the limitations of this study?

Del Siegle, PhD [email protected]

Last modified 6/18/2019

- Chamberlain University Library

- Chamberlain Library Core

Finding Types of Research

- Evidence-Based Research

On This Guide

About this guide, understand evidence-based practice, identify research study types.

- Quantitative Studies

- Qualitative Studies

- Meta-Analysis

- Systematic Reviews

- Randomized Controlled Trials

- Observational Studies

- Literature Reviews

- Finding Research Tools This link opens in a new window

Throughout your schooling, you may need to find different types of evidence and research to support your course work. This guide provides a high-level overview of evidence-based practice as well as the different types of research and study designs. Each page of this guide offers an overview and search tips for finding articles that fit that study design.

Note! If you need help finding a specific type of study, visit the Get Research Help guide to contact the librarians.

What is Evidence-Based Practice?

One of the requirements for your coursework is to find articles that support evidence-based practice. But what exactly is evidence-based practice? Evidence-based practice is a method that uses relevant and current evidence to plan, implement and evaluate patient care. This definition is included in the video below, which explains all the steps of evidence-based practice in greater detail.

- Video - Evidence-based practice: What it is and what it is not. Medcom (Producer), & Cobb, D. (Director). (2017). Evidence-based practice: What it is and what it is not [Streaming Video]. United States of America: Producer. Retrieved from Alexander Street Press Nursing Education Collection

Quantitative and Qualitative Studies

Research is broken down into two different types: quantitative and qualitative. Quantitative studies are all about measurement. They will report statistics of things that can be physically measured like blood pressure, weight and oxygen saturation. Qualitative studies, on the other hand, are about people's experiences and how they feel about something. This type of information cannot be measured using statistics. Both of these types of studies report original research and are considered single studies. Watch the video below for more information.

Study Designs

Some research study types that you will encounter include:

- Case-Control Studies

- Cohort Studies

- Cross-Sectional Studies

Studies that Synthesize Other Studies

Sometimes, a research study will look at the results of many studies and look for trends and draw conclusions. These types of studies include:

- Meta Analyses

Tip! How do you determine the research article's study type or level of evidence? First, look at the article abstract. Most of the time the abstract will have a methodology section, which should tell you what type of study design the researchers are using. If it is not in the abstract, look for the methodology section of the article. It should tell you all about what type of study the researcher is doing and the steps they used to carry out the study.

Read the book below to learn how to read a clinical paper, including the types of study designs you will encounter.

- Search Website

- Library Tech Support

- Services for Colleagues

Chamberlain College of Nursing is owned and operated by Chamberlain University LLC. In certain states, Chamberlain operates as Chamberlain College of Nursing pending state authorization for Chamberlain University.

- Clinical Trials

About Clinical Studies

Research: it's all about patients.

Mayo's mission is about the patient, the patient comes first. So the mission and research here, is to advance how we can best help the patient, how to make sure the patient comes first in care. So in many ways, it's a cycle. It can start with as simple as an idea, worked on in a laboratory, brought to the patient bedside, and if everything goes right, and let's say it's helpful or beneficial, then brought on as a standard approach. And I think that is one of the unique characteristics of Mayo's approach to research, that patient-centeredness. That really helps to put it in its own spotlight.

At Mayo Clinic, the needs of the patient come first. Part of this commitment involves conducting medical research with the goal of helping patients live longer, healthier lives.

Through clinical studies, which involve people who volunteer to participate in them, researchers can better understand how to diagnose, treat and prevent diseases or conditions.

Types of clinical studies

- Observational study. A type of study in which people are observed or certain outcomes are measured. No attempt is made by the researcher to affect the outcome — for example, no treatment is given by the researcher.

- Clinical trial (interventional study). During clinical trials, researchers learn if a new test or treatment works and is safe. Treatments studied in clinical trials might be new drugs or new combinations of drugs, new surgical procedures or devices, or new ways to use existing treatments. Find out more about the five phases of non-cancer clinical trials on ClinicalTrials.gov or the National Cancer Institute phases of cancer trials .

- Medical records research. Medical records research involves the use of information collected from medical records. By studying the medical records of large groups of people over long periods of time, researchers can see how diseases progress and which treatments and surgeries work best. Find out more about Minnesota research authorization .

Clinical studies may differ from standard medical care

A health care provider diagnoses and treats existing illnesses or conditions based on current clinical practice guidelines and available, approved treatments.

But researchers are constantly looking for new and better ways to prevent and treat disease. In their laboratories, they explore ideas and test hypotheses through discovery science. Some of these ideas move into formal clinical trials.

During clinical studies, researchers formally and scientifically gather new knowledge and possibly translate these findings into improved patient care.

Before clinical trials begin

This video demonstrates how discovery science works, what happens in the research lab before clinical studies begin, and how a discovery is transformed into a potential therapy ready to be tested in trials with human participants:

How clinical trials work

Trace the clinical trial journey from a discovery research idea to a viable translatable treatment for patients:

See a glossary of terms related to clinical studies, clinical trials and medical research on ClinicalTrials.gov.

Watch a video about clinical studies to help you prepare to participate.

Let's Talk About Clinical Research

Narrator: This presentation is a brief introduction to the terms, purposes, benefits and risks of clinical research.

If you have questions about the content of this program, talk with your health care provider.

What is clinical research?

Clinical research is a process to find new and better ways to understand, detect, control and treat health conditions. The scientific method is used to find answers to difficult health-related questions.

Ways to participate

There are many ways to participate in clinical research at Mayo Clinic. Three common ways are by volunteering to be in a study, by giving permission to have your medical record reviewed for research purposes, and by allowing your blood or tissue samples to be studied.

Types of clinical research

There are many types of clinical research:

- Prevention studies look at ways to stop diseases from occurring or from recurring after successful treatment.

- Screening studies compare detection methods for common conditions.

- Diagnostic studies test methods for early identification of disease in those with symptoms.

- Treatment studies test new combinations of drugs and new approaches to surgery, radiation therapy and complementary medicine.

- The role of inheritance or genetic studies may be independent or part of other research.

- Quality of life studies explore ways to manage symptoms of chronic illness or side effects of treatment.

- Medical records studies review information from large groups of people.

Clinical research volunteers

Participants in clinical research volunteer to take part. Participants may be healthy, at high risk for developing a disease, or already diagnosed with a disease or illness. When a study is offered, individuals may choose whether or not to participate. If they choose to participate, they may leave the study at any time.

Research terms

You will hear many terms describing clinical research. These include research study, experiment, medical research and clinical trial.

Clinical trial

A clinical trial is research to answer specific questions about new therapies or new ways of using known treatments. Clinical trials take place in phases. For a treatment to become standard, it usually goes through two or three clinical trial phases. The early phases look at treatment safety. Later phases continue to look at safety and also determine the effectiveness of the treatment.

Phase I clinical trial

A small number of people participate in a phase I clinical trial. The goals are to determine safe dosages and methods of treatment delivery. This may be the first time the drug or intervention is used with people.

Phase II clinical trial

Phase II clinical trials have more participants. The goals are to evaluate the effectiveness of the treatment and to monitor side effects. Side effects are monitored in all the phases, but this is a special focus of phase II.

Phase III clinical trial

Phase III clinical trials have the largest number of participants and may take place in multiple health care centers. The goal of a phase III clinical trial is to compare the new treatment to the standard treatment. Sometimes the standard treatment is no treatment.

Phase IV clinical trial

A phase IV clinical trial may be conducted after U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval. The goal is to further assess the long-term safety and effectiveness of a therapy. Smaller numbers of participants may be enrolled if the disease is rare. Larger numbers will be enrolled for common diseases, such as diabetes or heart disease.

Clinical research sponsors

Mayo Clinic funds clinical research at facilities in Rochester, Minnesota; Jacksonville, Florida; and Arizona, and in the Mayo Clinic Health System. Clinical research is conducted in partnership with other medical centers throughout the world. Other sponsors of research at Mayo Clinic include the National Institutes of Health, device or pharmaceutical companies, foundations and organizations.

Clinical research at Mayo Clinic

Dr. Hugh Smith, former chair of Mayo Clinic Board of Governors, stated, "Our commitment to research is based on our knowledge that medicine must be constantly moving forward, that we need to continue our efforts to better understand disease and bring the latest medical knowledge to our practice and to our patients."

This fits with the term "translational research," meaning what is learned in the laboratory goes quickly to the patient's bedside and what is learned at the bedside is taken back to the laboratory.

Ethics and safety of clinical research

All clinical research conducted at Mayo Clinic is reviewed and approved by Mayo's Institutional Review Board. Multiple specialized committees and colleagues may also provide review of the research. Federal rules help ensure that clinical research is conducted in a safe and ethical manner.

Institutional review board

An institutional review board (IRB) reviews all clinical research proposals. The goal is to protect the welfare and safety of human subjects. The IRB continues its review as research is conducted.

Consent process

Participants sign a consent form to ensure that they understand key facts about a study. Such facts include that participation is voluntary and they may withdraw at any time. The consent form is an informational document, not a contract.

Study activities

Staff from the study team describe the research activities during the consent process. The research may include X-rays, blood tests, counseling or medications.

Study design

During the consent process, you may hear different phrases related to study design. Randomized means you will be assigned to a group by chance, much like a flip of a coin. In a single-blinded study, participants do not know which treatment they are receiving. In a double-blinded study, neither the participant nor the research team knows which treatment is being administered.

Some studies use an inactive substance called a placebo.

Multisite studies allow individuals from many different locations or health care centers to participate.

Remuneration

If the consent form states remuneration is provided, you will be paid for your time and participation in the study.

Some studies may involve additional cost. To address costs in a study, carefully review the consent form and discuss questions with the research team and your insurance company. Medicare may cover routine care costs that are part of clinical trials. Medicaid programs in some states may also provide routine care cost coverage, as well.

When considering participation in a research study, carefully look at the benefits and risks. Benefits may include earlier access to new clinical approaches and regular attention from a research team. Research participation often helps others in the future.

Risks/inconveniences

Risks may include side effects. The research treatment may be no better than the standard treatment. More visits, if required in the study, may be inconvenient.

Weigh your risks and benefits

Consider your situation as you weigh the risks and benefits of participation prior to enrolling and during the study. You may stop participation in the study at any time.

Ask questions

Stay informed while participating in research:

- Write down questions you want answered.

- If you do not understand, say so.

- If you have concerns, speak up.

Website resources are available. The first website lists clinical research at Mayo Clinic. The second website, provided by the National Institutes of Health, lists studies occurring in the United States and throughout the world.

Additional information about clinical research may be found at the Mayo Clinic Barbara Woodward Lips Patient Education Center and the Stephen and Barbara Slaggie Family Cancer Education Center.

Clinical studies questions

- Phone: 800-664-4542 (toll-free)

- Contact form

Cancer-related clinical studies questions

- Phone: 855-776-0015 (toll-free)

International patient clinical studies questions

- Phone: 507-284-8884

- Email: [email protected]

Clinical Studies in Depth

Learning all you can about clinical studies helps you prepare to participate.

- Institutional Review Board

The Institutional Review Board protects the rights, privacy, and welfare of participants in research programs conducted by Mayo Clinic and its associated faculty, professional staff, and students.

More about research at Mayo Clinic

- Research Faculty

- Laboratories

- Core Facilities

- Centers & Programs

- Departments & Divisions

- Postdoctoral Fellowships

- Training Grant Programs

- Publications

Mayo Clinic Footer

- Request Appointment

- About Mayo Clinic

- About This Site

Legal Conditions and Terms

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Notice of Privacy Practices

- Notice of Nondiscrimination

- Manage Cookies

Advertising

Mayo Clinic is a nonprofit organization and proceeds from Web advertising help support our mission. Mayo Clinic does not endorse any of the third party products and services advertised.

- Advertising and sponsorship policy

- Advertising and sponsorship opportunities

Reprint Permissions

A single copy of these materials may be reprinted for noncommercial personal use only. "Mayo," "Mayo Clinic," "MayoClinic.org," "Mayo Clinic Healthy Living," and the triple-shield Mayo Clinic logo are trademarks of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.3: Types of Research Studies and How To Interpret Them

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 59269

- Alice Callahan, Heather Leonard, & Tamberly Powell

- Lane Community College via OpenOregon

The field of nutrition is dynamic, and our understanding and practices are always evolving. Nutrition scientists are continuously conducting new research and publishing their findings in peer-reviewed journals. This adds to scientific knowledge, but it’s also of great interest to the public, so nutrition research often shows up in the news and other media sources. You might be interested in nutrition research to inform your own eating habits, or if you work in a health profession, so that you can give evidence-based advice to others. Making sense of science requires that you understand the types of research studies used and their limitations.

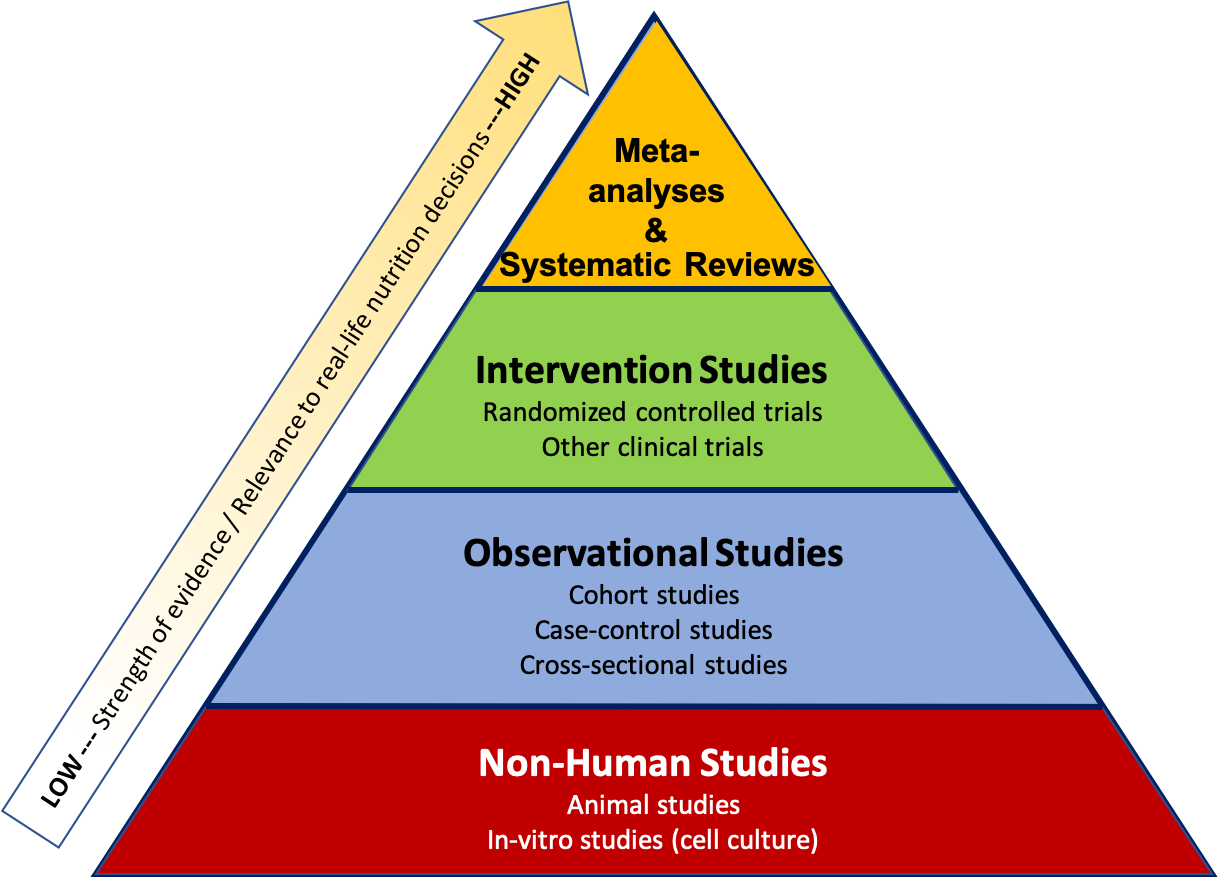

The Hierarchy of Nutrition Evidence

Researchers use many different types of study designs depending on the question they are trying to answer, as well as factors such as time, funding, and ethical considerations. The study design affects how we interpret the results and the strength of the evidence as it relates to real-life nutrition decisions. It can be helpful to think about the types of studies within a pyramid representing a hierarchy of evidence, where the studies at the bottom of the pyramid usually give us the weakest evidence with the least relevance to real-life nutrition decisions, and the studies at the top offer the strongest evidence, with the most relevance to real-life nutrition decisions .

Figure 2.1. Hierarchy of research design and levels of scientific evidence with the strongest studies at the top and the weakest at the bottom.

The pyramid also represents a few other general ideas. There tend to be more studies published using the methods at the bottom of the pyramid, because they require less time, money, and other resources. When researchers want to test a new hypothesis , they often start with the study designs at the bottom of the pyramid , such as in vitro, animal, or observational studies. Intervention studies are more expensive and resource-intensive, so there are fewer of these types of studies conducted. But they also give us higher quality evidence, so they’re an important next step if observational and non-human studies have shown promising results. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews combine the results of many studies already conducted, so they help researchers summarize scientific knowledge on a topic.

Non-Human Studies: In Vitro & Animal Studies

The simplest form of nutrition research is an in vitro study . In vitro means “within glass,” (although plastic is used more commonly today) and these experiments are conducted within flasks, dishes, plates, and test tubes. One common form of in vitro research is cell culture. This involves growing cells in flasks and dishes. In order for cells to grow, they need a nutrient source. For cell culture, the nutrient source is referred to as media. Media supplies nutrients to the cells in vitro similarly to how blood performs this function within the body. Most cells adhere to the bottom of the flask and are so small that a microscope is needed to see them. The cells are grown inside an incubator, which is a device that provides the optimal temperature, humidity, and carbon dioxide (CO2CO2) concentrations for cells and microorganisms. By imitating the body's temperature and CO2CO2 levels (37 degrees Celsius, 5% CO2CO2), the incubator allows cells to grow even though they are outside the body.