- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

A Successful International Assignment Depends on These Factors

- Boris Groysberg

- Robin Abrahams

Your marriage, your family, and your career will all benefit from advance planning.

The prospect of an international assignment can be equal parts thrilling and alarming: Will it make or break your career? What will it do to your life at home and the people you love? When you’re thinking about relocating, you start viewing questions of work and family — difficult enough under ordinary circumstances — through a kind of high-contrast, maximum-drama filter.

- BG Boris Groysberg is a professor of business administration in the Organizational Behavior unit at Harvard Business School and a faculty affiliate at the school’s Race, Gender & Equity Initiative. He is the coauthor, with Colleen Ammerman, of Glass Half-Broken: Shattering the Barriers That Still Hold Women Back at Work (Harvard Business Review Press, 2021). bgroysberg

- Robin Abrahams is a research associate at Harvard Business School.

Partner Center

- Internships

- Career Advice

7 Strategies for a Successful International Work Assignment

Published: Oct 08, 2018

International assignments are exciting for a host of reasons, but having the opportunity to live in another country while finding success in your career at the same time is particularly compelling. Working abroad allows you to gain real-world experience, advance the skills you have, and learn how to thrive in a global environment.

But living and working in a new country with a different culture is a major life change. It’s important to immerse yourself in the experience and remain positive through the ups and downs. Below are 7 tips to make the most of your journey abroad.

1. Keep an Open Mind

Social media and the internet allows us to connect with people from all over the world. Take time to learn about the history of your new home, including any local customs or laws, so you can set more realistic expectations ahead of time.

When you finally touch down in your new destination, keep an open mind. What you think you know about an area or country may end up being turned on its head once you spend more than a few days there.

For Allison Alexander, a participant in Abbott’s Finance Professional Development Program , an international assignment was the ultimate lesson in flexibility. “Going to an international role means you’re stepping into a culture and a set of expectations that are foreign to you,” she explains. “It forces you to be open to the unexpected.”

Unlike traveling for leisure, international assignments allow you to spend months or even years in a location. You can, and should, tap into the global mindset you’ve already developed while leaving room for all the surprises that will come from long-term exposure to a different culture.

2. Set Goals

Maximize the benefits of an international assignment by setting goals for yourself at the beginning. What do you hope to accomplish in the first two weeks? How can you challenge yourself once you’ve settled in? And when you leave, what are the skills you want to take with you? Having clearly defined milestones will help you stay focused on what’s important and define the steps needed to grow your career.

3. Develop Language Skills

You may not become fluent, but practicing the local language can help you build deeper connections within the community and potentially open up new work opportunities in the future. Don’t fret if you stumble through mispronunciations and tenses at first, the more you practice, the more confident you'll become, and the better you'll get.

4. Be Adventurous

When you're abroad, it's great to take advantage of travel. You have a new world at your doorstep! It's also a chance to try activities you've never tried before.

"I've been doing things I thought of all my life but could never muster enough courage to actually do," says Timir Gupta, another member of Abbott's Finance Professional Development Program, who has traveled solo, tried skydiving, and chased the northern lights. "And it's a great conversation starter during an interview," he adds.

5. Apply New Perspectives

Gaining insight into different business practices can help you learn to look at old problems in new ways when you return home. This type of creative problem solving will be an asset no matter what your next assignment is.

"When you finally make your way back to a domestic role, you've now become an expert in two completely different professional structures," says Alexander. "You've seen what works and what doesn't in a global setting, and you can lead the group on new ways of thinking that may lead to more success."

6. Expand Your Network

Get out and build connections, both at your assignment and beyond. "Because of traveling, I have friends all over the world," says Gupta. He now has connections across five continents that he can tap into when looking for a reference or career advice.

Luckily, maintaining the professional network you build abroad is now easier than ever before. Social media, LinkedIn, and apps like WhatsApp can help you stay in contact with your colleagues and mentors.

7. Market Yourself and Build Your Career

When you return home, don't forget to incorporate your experience into your personal branding. You want to make sure prospective employers know how your new skills, perspectives, and connections set you apart. Think: How can I rework my resume and reframe interview answers to showcase what I've learned?

Depending on your experience, you may even refocus your career or choose employers who will use your global mindset. If you want more opportunities to go abroad, many multinational organizations offer international assignments. With offices in more than 150 countries, Abbott has numerous internships and development programs for students in finance, information technology, engineering, manufacturing, environmental health, and quality assurance.

Look for companies expanding in emerging markets, too. This can give you the unique opportunity to get in at the ground level and learn how to evolve a product or service to match the local market.

No matter what you choose or where you go, an international assignment can provide you with the unique opportunity to grow personally and professionally—and hopefully have a little fun along the way too.

This post was sponsored by Abbott .

- Cases, Comments and Current Trends

What Motivates People to Take on Global Work?

Although travel restrictions due to the Covid-19 pandemic are taking a toll on physically mobile people such as expatriates or migrants, the number of people working across national boundaries is nowhere near stagnating. In fact, studies such as the Santa Fe Relocation Global Mobility Survey 2020/21 suggest that the nature of global mobility is evolving in ways to offer an even broader array of opportunities. For instance, the advance of hybrid forms of international assignments or global virtual team membership provide people with mobility options that do not require being physically present in other countries. It is therefore not surprising that the number of people working across borders is still growing. In this context, one question that has been appealing to both practitioners and academics but has still not been investigated sufficiently in depth is what motivates people to become involved in “global work”, or work that goes beyond national or cultural boundaries.

One might intuitively think that previous international experiences such as university study abroad programs or international assignments in multinational companies may be a trigger for future global work. However, people differ in how they make sense of their previous experiences and make decisions about their own careers. Focusing solely on previous international experience would yield an incomplete picture of global work motivations. For instance, challenges associated with global work such as intercultural frictions or potential hazards to one’s career may deter people with previous international experience from further mobility across borders. Therefore, how might previous international experiences motivate people to take on global work? To address this conundrum, my colleagues Eren Akkan, Yih-teen Lee and I embarked on a multi-year study to understand how and under which conditions previous international experiences trigger the motivation for and actual involvement in global work.

Our first finding is that people would be motivated to take on global work to the extent that their previous international experiences lead them to define themselves as suitable for future global work. We argued that those who spent longer time in culturally novel environments would retrospectively make sense of these dense, culturally novel international experiences as the basis for feeling more “global”. More specifically, dense international experiences provide the opportunity to bridge across cultures and be used to interact with people from distant cultural backgrounds. As a result, such experiences can make people feel part of a global village that goes beyond cultural boundaries, thereby becoming global citizens.

Furthermore, our results also showed that defining oneself as global by means of dense international experiences was an insufficient motivator for future global work. In fact, we observed that these individuals should also receive signals from their foreign colleagues regarding their capability to manage effectively across cultural boundaries. Such signals of cross-cultural competence should complement the feeling of being global to perceive a personal fit for future global work. In other words, a reality check is also necessary to assure these individuals of their suitability for global work, and consequently, aspire to take on future global work.

What do these findings mean for organizations? As career motivation is one important determinant of employee performance, multinational companies that rely on experience-related information in CVs and discard employees’ own perspectives may risk selecting employees that are not fit for global work. Furthermore, companies that lack rigorous mechanisms for providing intercultural competence feedback to their employees may miss the opportunity to motivate their employees for future global work. Therefore, it is crucial for organizations to thoroughly evaluate how previous international experiences influence their employees’ self-definitions and provide their employees with accurate feedback regarding their cultural competences. Implementing such evaluation and feedback mechanisms in tandem would be critical for selecting employees who are motivated to and thus more likely to succeed in global work, eventually aiding multinational organizations to effectively utilize their global workforce.

Further reading:

Akkan, E., Lee, Y.-t., & Reiche, B.S. (2022). How and when do prior international experiences lead to global work? A career motivation perspective. Human Resource Management , 61(1): 117-132.

NB: This research was supported by funding from the Spanish AEI (PID2019-103897GB-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033).

- career motivation

- employee performance

- global work

- international experience

- multinational company

- Google Plus

Post a comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Book a Speaker

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Vivamus convallis sem tellus, vitae egestas felis vestibule ut.

Error message details.

Reuse Permissions

Request permission to republish or redistribute SHRM content and materials.

Managing International Assignments

International assignment management is one of the hardest areas for HR professionals to master—and one of the most costly. The expense of a three-year international assignment can cost millions, yet many organizations fail to get it right. Despite their significant investments in international assignments, companies still report a 42 percent failure rate in these assignments. 1

With so much at risk, global organizations must invest in upfront and ongoing programs that will make international assignments successful. Selecting the right person, preparing the expatriate (expat) and the family, measuring the employee's performance from afar, and repatriating the individual at the end of an assignment require a well-planned, well-managed program. Knowing what to expect from start to finish as well as having some tools to work with can help minimize the risk.

Business Case

As more companies expand globally, they are also increasing international assignments and relying on expatriates to manage their global operations. According to KPMG's 2021 Global Assignment Policies and Practices Survey, all responding multinational organizations offered long-term assignments (typically one to five years), 88 percent offered short-term assignments (typically defined as less than 12 months), and 69 percent offered permanent transfer/indefinite length.

Managing tax and tax compliance, cost containment and managing exceptions remain the three principal challenges in long-term assignment management according to a 2020 Mercer report. 2

Identifying the Need for International Assignment

Typical reasons for an international assignment include the following:

- Filling a need in an existing operation.

- Transferring technology or knowledge to a worksite (or to a client's worksite).

- Developing an individual's career through challenging tasks in an international setting.

- Analyzing the market to see whether the company's products or services will attract clients and users.

- Launching a new product or service.

The goal of the international assignment will determine the assignment's length and help identify potential candidates. See Structuring Expatriate Assignments and the Value of Secondment and Develop Future Leaders with Rotational Programs .

Selection Process

Determining the purpose and goals for an international assignment will help guide the selection process. A technical person may be best suited for transferring technology, whereas a sales executive may be most effective launching a new product or service.

Traditionally, organizations have relied on technical, job-related skills as the main criteria for selecting candidates for overseas assignments, but assessing global mindset is equally, if not more, important for successful assignments. This is especially true given that international assignments are increasingly key components of leadership and employee development.

To a great extent, the success of every expatriate in achieving the company's goals in the host country hinges on that person's ability to influence individuals, groups and organizations that have a different cultural perspective.

Interviews with senior executives from various industries, sponsored by the Worldwide ERC Foundation, reveal that in the compressed time frame of an international assignment, expatriates have little opportunity to learn as they go, so they must be prepared before they arrive. Therefore, employers must ensure that the screening process for potential expatriates includes an assessment of their global mindset.

The research points to three major attributes of successful expatriates:

- Intellectual capital. Knowledge, skills, understanding and cognitive complexity.

- Psychological capital. The ability to function successfully in the host country through internal acceptance of different cultures and a strong desire to learn from new experiences.

- Social capital. The ability to build trusting relationships with local stakeholders, whether they are employees, supply chain partners or customers.

According to Global HR Consultant Caroline Kersten, it is generally understood that global leadership differs significantly from domestic leadership and that, as a result, expatriates need to be equipped with competencies that will help them succeed in an international environment. Commonly accepted global leadership competencies, for both male and female global leaders, include cultural awareness, open-mindedness and flexibility.

In particular, expatriates need to possess a number of vital characteristics to perform successfully on assignment. Among the necessary traits are the following:

- Confidence and self-reliance: independence; perseverance; work ethic.

- Flexibility and problem-solving skills: resilience; adaptability; ability to deal with ambiguity.

- Tolerance and interpersonal skills: social sensitivity; observational capability; listening skills; communication skills.

- Skill at handling and initiating change: personal drivers and anchors; willingness to take risks.

Trends in international assignment show an increase in the younger generation's interest and placement in global assignments. Experts also call for a need to increase female expatriates due to the expected leadership shortage and the value employers find in mixed gender leadership teams. See Viewpoint: How to Break Through the 'Mobility Ceiling' .

Employers can elicit relevant information on assignment successes and challenges by means of targeted interview questions with career expatriates, such as the following:

- How many expatriate assignments have you completed?

- What are the main reasons why you chose to accept your previous expatriate assignments?

- What difficulties did you experience adjusting to previous international assignments? How did you overcome them?

- On your last assignment, what factors made your adjustment to the new environment easier?

- What experiences made interacting with the locals easier?

- Please describe what success or failure means to you when referring to an expatriate assignment.

- Was the success or failure of your assignments measured by your employers? If so, how did they measure it?

- During your last international assignment, do you recall when you realized your situation was a success or a failure? How did you come to that determination?

- Why do you wish to be assigned an international position?

Securing Visas

Once an individual is chosen for an assignment, the organization needs to move quickly to secure the necessary visas. Requirements and processing times vary by country. Employers should start by contacting the host country's consulate or embassy for information on visa requirements. See Websites of U.S. Embassies, Consulates, and Diplomatic Missions .

Following is a list of generic visa types that may be required depending on the nature of business to be conducted in a particular country:

- A work permit authorizes paid employment in a country.

- A work visa authorizes entry into a country to take up paid employment.

- A dependent visa permits family members to accompany or join employees in the country of assignment.

- A multiple-entry visa permits multiple entries into a country.

Preparing for the Assignment

An international assignment agreement that outlines the specifics of the assignment and documents agreement by the employer and the expatriate is necessary. Topics typically covered include:

- Location of the assignment.

- Length of the assignment, including renewal and trial periods, if offered.

- Costs paid by the company (e.g., assignment preparation costs, moving costs for household goods, airfare, housing, school costs, transportation costs while in country, home country visits and security).

- Base salary and any incentives or allowances offered.

- Employee's responsibilities and goals.

- Employment taxes.

- Steps to take in the event the assignment is not working for either the employee or the employer.

- Repatriation.

- Safety and security measures (e.g., emergency evacuation procedures, hazards).

Expatriates may find the reality of foreign housing very different from expectations, particularly in host locations considered to be hardship assignments. Expats will find—depending on the degree of difficulty, hardship or danger—that housing options can range from spacious accommodations in a luxury apartment building to company compounds with dogs and armed guards. See Workers Deal with Affordable Housing Shortages in Dubai and Cairo .

Expats may also have to contend with more mundane housing challenges, such as shortages of suitable housing, faulty structures and unreliable utility services. Analyses of local conditions are available from a variety of sources. For example, Mercer produces Location Evaluation Reports, available for a fee, that evaluate levels of hardship for 14 factors, including housing, in more than 135 locations.

Although many employers acknowledge the necessity for thorough preparation, they often associate this element solely with the assignee, forgetting the other key parties involved in an assignment such as the employee's family, work team and manager.

The expatriate

Consider these points in relation to the assignee:

- Does the employee have a solid grasp of the job to be done and the goals established for that position?

- Does the employee understand the compensation and benefits package?

- Has the employee had access to cultural training and language instruction, no matter how similar the host culture may be?

- Is the employee receiving relocation assistance in connection with the physical move?

- Is there a contact person to whom the employee can go not only in an emergency but also to avoid becoming "out of sight, out of mind"?

- If necessary to accomplish the assigned job duties, has the employee undergone training to get up to speed?

- Has the assignee undergone an assessment of readiness?

To help the expatriate succeed, organizations are advised to invest in cross-cultural training before the relocation. The benefits of receiving such training are that it: 3

- Prepares the individual/family mentally for the move.

- Removes some of the unknown.

- Increases self-awareness and cross-cultural understanding.

- Provides the opportunity to address questions and anxieties in a supportive environment.

- Motivates and excites.

- Reduces stress and provides coping strategies.

- Eases the settling-in process.

- Reduces the chances of relocation failure.

See Helping Expatriate Employees Deal with Culture Shock .

As society has shifted from single- to dual-income households, the priorities of potential expatriates have evolved, as have the policies organizations use to entice employees to assignment locations. In the past, from the candidate's point of view, compensation was the most significant component of the expatriate package. Today more emphasis is on enabling an expatriate's spouse to work. Partner dissatisfaction is a significant contributor to assignment failure. See UAE: Expat Husbands Get New Work Opportunities .

When it comes to international relocation, most organizations deal with children as an afterthought. Factoring employees' children into the relocation equation is key to a successful assignment. Studies show that transferee children who have a difficult time adjusting to the assignment contribute to early returns and unsuccessful completion of international assignments, just as maladjusted spouses do. From school selection to training to repatriation, HR can do a number of things to smooth the transition for children.

Both partners and children must be prepared for relocation abroad. Employers should consider the following:

- Have they been included in discussions about the host location and what they can expect? Foreign context and culture may be more difficult for accompanying family because they will not be participating in the "more secure" environment of the worksite. Does the family have suitable personal characteristics to successfully address the rigors of an international life?

- In addition to dual-career issues, other common concerns include aging parents left behind in the home country and special needs for a child's education. Has the company allowed a forum for the family to discuss these concerns?

The work team

Whether the new expatriate will supervise the existing work team, be a peer, replace a local national or fill a newly created position, has the existing work team been briefed? Plans for a formal introduction of the new expatriate should reflect local culture and may require more research and planning as well as input from the local work team.

The manager/team leader

Questions organization need to consider include the following: Does the manager have the employee's file on hand (e.g., regarding increases, performance evaluations, promotions and problems)? Have the manager and employee engaged in in-depth conversations about the job, the manager's expectations and the employee's expectations?

Mentors play an important role in enhancing a high-performing employee's productivity and in guiding his or her career. In a traditional mentoring relationship, a junior executive has ongoing face-to-face meetings with a senior executive at the corporation to learn the ropes, set goals and gain advice on how to better perform his or her job.

Before technological advances, mentoring programs were limited to those leaders who had the time and experience within the organization's walls to impart advice to a few select people worth that investment. Technology has eliminated those constraints. Today, maintaining a long-distance mentoring relationship through e-mail, telephone and videoconferencing is much easier. And that technology means an employer is not confined to its corporate halls when considering mentor-mentee matches.

The organization

If the company is starting to send more employees abroad, it has to reassess its administrative capabilities. Can existing systems handle complicated tasks, such as currency exchanges and split payrolls, not to mention the additional financial burden of paying allowances, incentives and so on? Often, international assignment leads to outsourcing for global expertise. Payroll, tax, employment law, contractual obligations, among others, warrant an investment in sound professional advice.

Employment Laws

Four major U.S. employment laws have some application abroad for U.S. citizens working in U.S.-based multinationals:

- Title VII of the Civil Rights Act.

- The Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA).

- The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

- The Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act (USERRA).

Title VII, the ADEA and the ADA are the more far-reaching among these, covering all U.S. citizens who are either:

- Employed outside the United States by a U.S. firm.

- Employed outside the United States by a company under the control of a U.S. firm.

USERRA's extraterritoriality applies to veterans and reservists working overseas for the federal government or a firm under U.S. control. See Do laws like the Fair Labor Standards Act and the Family and Medical Leave Act apply to U.S. citizens working in several other countries?

Employers must also be certain to comply with both local employment law in the countries in which they manage assignments and requirements for corporate presence in those countries. See Where can I find international employment law and culture information?

Compensation

Companies take one of the following approaches to establish base salaries for expatriates:

- The home-country-based approach. The objective of a home-based compensation program is to equalize the employee to a standard of living enjoyed in his or her home country. Under this commonly used approach, the employee's base salary is broken down into four general categories: taxes, housing, goods and services, and discretionary income.

- The host-country-based approach. With this approach, the expatriate employee's compensation is based on local national rates. Many companies continue to cover the employee in its defined contribution or defined benefit pension schemes and provide housing allowances.

- The headquarters-based approach. This approach assumes that all assignees, regardless of location, are in one country (i.e., a U.S. company pays all assignees a U.S.-based salary, regardless of geography).

- Balance sheet approach. In this scenario, the compensation is calculated using the home-country-based approach with all allowances, deductions and reimbursements. After the net salary has been determined, it is then converted to the host country's currency. Since one of the primary goals of an international compensation management program is to maintain the expatriate's current standard of living, developing an equitable and functional compensation plan that combines balance and flexibility is extremely challenging for multinational companies. To this end, many companies adopt a balance sheet approach. This approach guarantees that employees in international assignments maintain the same standard of living they enjoyed in their home country. A worksheet lists the costs of major expenses in the home and host countries, and any differences are used to increase or decrease the compensation to keep it in balance.

Some companies also allow expatriates to split payment of their salaries between the host country's and the home country's currencies. The expatriate receives money in the host country's currency for expenses but keeps a percentage of it in the home country currency to safeguard against wild currency fluctuations in either country.

As for handling expatriates taxes, organizations usually take one of four approaches:

- The employee is responsible for his or her own taxes.

- The employer determines tax reimbursement on a case-by-case basis.

- The employer pays the difference between taxes paid in the United States and the host country.

- The employer withholds U.S. taxes and pays foreign taxes.

To prevent an expatriate employee from suffering excess taxation of income by both the U.S. and host countries, many multinational companies implement either a tax equalization or a tax reduction policy for employees on international assignments. Additionally, the United States has entered into bilateral international social security agreements with numerous countries, referred to as "totalization agreements," which allow for an exemption of the social security tax in either the home or host country for defined periods of time.

A more thorough discussion of compensation and tax practices for employees on international assignment can be found in SHRM's Designing Global Compensation Systems toolkit.

How do we handle taxes for expatriates?

Can employers pay employees in other countries on the corporate home-country payroll?

Measuring Expatriates' Performance

Failed international assignments can be extremely costly to an organization. There is no universal approach to measuring an expatriate's performance given that specifics related to the job, country, culture and other variables will need to be considered. Employers must identify and communicate clear job expectations and performance indicators very early on in the assignment. A consistent and detailed assessment of an expatriate employee's performance, as well as appraisal of the operation as a whole, is critical to the success of an international assignment. Issues such as the criteria for and timing of performance reviews, raises and bonuses should be discussed and agreed on before the employees are selected and placed on international assignments.

Employees on foreign assignments face a number of issues that domestic employees do not. According to a 2020 Mercer report 4 , difficulty adjusting to the host country, poor candidate selection and spouse or partner's unhappiness are the top three reasons international assignments fail. Obviously, retention of international assignees poses a significant challenge to employers.

Upon completion of an international assignment, retaining the employee in the home country workplace is also challenging. Unfortunately, many employers fail to track retention data of repatriated employees and could benefit from collecting this information and making adjustments to reduce the turnover of employees returning to their home country.

Safety and Security

When faced with accident, injury, sudden illness, a disease outbreak or politically unstable conditions in which personal safety is at risk, expatriate employees and their dependents may require evacuation to the home country or to a third location. To be prepared, HR should have an evacuation plan in place that the expatriate can share with friends, extended family and colleagues both at home and abroad. See Viewpoint: Optimizing Global Mobility's Emergency Response Plans .

Many companies ban travel outside the country in the following circumstances:

- When a travel advisory is issued by the World Health Organization, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, International SOS or a government agency.

- When a widespread outbreak of a specific disease occurs or if the risk is deemed too high for employees and their well-being is in jeopardy.

- If the country is undergoing civil unrest or war or if an act of terrorism has occurred.

- If local management makes the decision.

- If the employee makes the decision.

Once employees are in place, the decision to evacuate assignees and dependents from a host location is contingent on local conditions and input from either internal sources (local managers, headquarters staff, HR and the assignee) or external sources (an external security or medical firm) or both. In some cases, each host country has its own set of evacuation procedures.

Decision-makers should consider all available and credible advice and initially transport dependents and nonessential personnel out of the host country by the most expeditious form of travel.

Navigating International Crises

How can an organization ensure the safety and security of expatriates and other employees in high-risk areas?

The Disaster Assistance Improvement Program (DAIP)

Repatriation

Ideally, the repatriation process begins before the expatriate leaves his or her home country and continues throughout the international assignment by addressing the following issues.

Career planning. Many managers are responsible for resolving difficult problems abroad and expect that a well-done job will result in promotion on return, regardless of whether the employer had made such a promise. This possibly unfounded assumption can be avoided by straightforward career planning that should occur in advance of the employee's accepting the international assignment. Employees need to know what impact the expatriate assignment will have on their overall advancement in the home office and that the international assignment fits in their career path.

Mentoring. The expatriate should be assigned a home-office mentor. Mentors are responsible for keeping expatriates informed on developments within the company, for keeping the expatriates' names in circulation in the office (to help avoid the out-of-sight, out-of-mind phenomenon) and for seeing to it that expatriates are included in important meetings. Mentors can also assist the expatriate in identifying how the overseas experience can best be used on return. Optimum results are achieved when the mentor role is part of the mentor's formal job duties.

Communication. An effective global communication plan will help expatriates feel connected to the home office and will alert them to changes that occur while they are away. The Internet, e-mail and intranets are inexpensive and easy ways to bring expatriates into the loop and virtual meeting software is readily available for all employers to engage with global employees. In addition, organizations should encourage home-office employees to keep in touch with peers on overseas assignments. Employee newsletters that feature global news and expatriate assignments are also encouraged.

Home visits. Most companies provide expatriates with trips home. Although such trips are intended primarily for personal visits, scheduling time for the expatriate to visit the home office is an effective method of increasing the expatriate's visibility. Having expatriates attend a few important meetings or make a presentation on their international assignment is also a good way to keep them informed and connected.

Preparation to return home. The expatriate should receive plenty of advance notice (some experts recommend up to one year) of when the international assignment will end. This notice will allow the employee time to prepare the family and to prepare for a new position in the home office. Once the employee is notified of the assignment's end, the HR department should begin working with the expatriate to identify suitable positions in the home office. The expatriate should provide the HR department with an updated resume that reflects the duties of the overseas assignment. The employee's overall career plan should be included in discussions with the HR professional.

Interviews. In addition to home leave, organizations may need to provide trips for the employee to interview with prospective managers. The face-to-face interview will allow the expatriate to elaborate on skills and responsibilities obtained while overseas and will help the prospective manager determine if the employee is a good fit. Finding the right position for the expatriate is crucial to retaining the employee. Repatriates who feel that their new skills and knowledge are underutilized may grow frustrated and leave the employer.

Ongoing recognition of contributions. An employer can recognize and appreciate the repatriates' efforts in several ways, including the following:

- Hosting a reception for repatriates to help them reconnect and meet new personnel.

- Soliciting repatriates' help in preparing other employees for expatriation.

- Asking repatriates to deliver a presentation or prepare a report on their overseas assignment.

- Including repatriates on a global task force and asking them for a global perspective on business issues.

Measuring ROI on expatriate assignments can be cumbersome and imprecise. The investment costs of international assignments can vary dramatically and can be difficult to determine. The largest expatriate costs include overall remuneration, housing, cost-of-living allowances (which sometimes include private schooling costs for children) and physical relocation (the movement to the host country of the employee, the employee's possessions and, often, the employee's family).

But wide variations exist in housing expenses. For example, housing costs are sky-high in Tokyo and London, whereas Australia's housing costs are moderate. Another significant cost of expatriate assignments involves smoothing out differences in pay and benefits between one country and another. Such cost differences can be steep and can vary based on factors such as exchange rates (which can be quite volatile) and international tax concerns (which can be extremely complex).

Once an organization has determined the costs of a particular assignment, the second part of the ROI challenge is calculating the return. Although it is relatively straightforward to quantify the value of fixing a production line in Puerto Rico or of implementing an enterprise software application in Asia, the challenge of quantifying the value of providing future executives with cross-cultural perspectives and international leadership experience can be intimidating.

Once an organization determines the key drivers of its expatriate program, HR can begin to define objectives and assess return that can be useful in guiding employees and in making decisions about the costs they incur as expatriates. Different objectives require different levels and lengths of tracking. Leadership development involves a much longer-term value proposition and should include a thorough repatriation plan. By contrast, the ROI of an international assignment that plugs a skills gap is not negatively affected if the expatriate bolts after successfully completing the engagement.

Additional Resources

International Assignment Management: Expatriate Policy and Procedure

Introduction to the Global Human Resources Discipline

1Mulkeen, D. (2017, February 20). How to reduce the risk of international assignment failure. Communicaid. Retrieved from https://www.communicaid.com/cross-cultural-training/blog/reducing-risk-international-assignment-failure/

2Mercer. (2020). Worldwide Survey of International Assignment Policies and Practices. Retrieved from https://mobilityexchange.mercer.com/international-assignments-survey .

3Dickmann, M., & Baruch, Y. (2011). Global careers. New York: Routledge.

4Mercer. (2020). Worldwide Survey of International Assignment Policies and Practices. Retrieved from https://mobilityexchange.mercer.com/international-assignments-survey

Related Articles

Rising Demand for Workforce AI Skills Leads to Calls for Upskilling

As artificial intelligence technology continues to develop, the demand for workers with the ability to work alongside and manage AI systems will increase. This means that workers who are not able to adapt and learn these new skills will be left behind in the job market.

Employers Want New Grads with AI Experience, Knowledge

A vast majority of U.S. professionals say students entering the workforce should have experience using AI and be prepared to use it in the workplace, and they expect higher education to play a critical role in that preparation.

The Pros and Cons of ‘Dry’ Promotions

Hr daily newsletter.

New, trends and analysis, as well as breaking news alerts, to help HR professionals do their jobs better each business day.

Success title

Success caption

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, intrinsic motivation for an international assignment.

International Journal of Manpower

ISSN : 0143-7720

Article publication date: 15 August 2008

This study aims to explore how the motivational construct of intrinsic motivation for an international assignment relates to variables of interest in international expatriation research.

Design/methodology/approach

Questionnaire data from 331 employed business school alumni of a high‐ranking Canadian MBA program was analyzed. The sample consisted of respondents from a wide variety of industries and occupations, with more than half of them in marketing, administration or engineering.

Higher intrinsic motivation for an international assignment was associated with greater willingness to accept an international assignment and to communicate in a foreign language. Externally driven motivation for an international assignment was associated with perceiving more difficulties associated with an international assignment. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations for an international assignment were, however, associated with comparable reactions to organizational support.

Originality/value

Drawing from self‐determination theory, this study explores the distinction between authentic versus externally controlled motivations for an international assignment. It underscores the need to pay more attention to motivational constructs in selecting, coaching, and training individuals for international expatriation assignments. It extends a rich tradition of research in the area of motivation to the international assignment arena.

- Expatriates

- Motivation (psychology)

- Multinational companies

Haines, V.Y. , Saba, T. and Choquette, E. (2008), "Intrinsic motivation for an international assignment", International Journal of Manpower , Vol. 29 No. 5, pp. 443-461. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437720810888571

Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2008, Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Leo Packers and Movers

- International Moving

How to Prepare Employees for International Assignments

In today’s globalized world, international assignments are increasingly prevalent. These opportunities allow employees to develop skills, gain experience, and contribute to their company’s global expansion. However, these assignments can also pose challenges, requiring employees to adapt to new cultures, languages, and ways of life.

Ensuring the success of an international assignment involves proper preparation, including providing the necessary skills, knowledge, and support.

Key Steps in Preparing Employees for International Assignments

Here are key steps in preparing employees for international assignments:

1. Assess Employee Suitability

Consider factors such as language skills, cultural adaptability, and willingness to relocate to determine if an employee is suited for an international assignment.

2. Offer Cultural Training

Provide insights into the host country’s culture, customs, and business practices to foster understanding.

3. Provide Language Training

For interactions with non-native speakers, offering language training can be beneficial.

4. Assist in Relocation

Facilitate housing, transportation, and help with visa and immigration paperwork.

5. Ensure Ongoing Support

Regular check-ins and resources for handling challenges are crucial to ongoing success.

Benefits of preparing employees for international assignments include:

- Enhanced Performance: Prepared employees are better equipped to handle challenges in new cultural environments, boosting their overall success.

- Increased Confidence: Cultural training and support bolster employees’ confidence in succeeding abroad.

- Improved Cross-Cultural Collaboration: Cultural understanding leads to smoother collaboration with international colleagues.

- Quick Adaptation: Preparation speeds up employees’ acclimatization, reducing stress.

- Higher Job Satisfaction: Well-prepared employees enjoy assignments more, leading to increased job satisfaction.

- Higher ROI: Companies investing in preparation tend to yield higher assignment success rates.

By following these steps, companies can ensure employees are well-equipped for international assignments, benefiting both employees and the company.

Additional Tips for Preparing Employees for Overseas Assignments

Additional tips for preparing employees for overseas assignments:

- Realistic Expectations: Help employees understand potential challenges, aiding in expectation management.

- Stay Connected to Home Culture: Encourage maintaining ties to their home culture for a sense of identity.

- Share Experiences: Provide avenues for sharing experiences with fellow colleagues for mutual support.

These strategies empower companies to facilitate positive and successful international assignments for their employees.

Pre-Move Training

Pre-move training is a crucial component of preparing employees for international assignments. It should cover practical aspects such as visa requirements, legal obligations, and documentation. Additionally, it’s an opportunity to address employees’ questions and concerns, setting expectations for the assignment.

Your Potential Challenges

Understanding the potential challenges that employees may face during international assignments is essential. These challenges can include language barriers, cultural differences, and adapting to a new work environment. Identifying these challenges in advance allows for proactive preparation and support.

Areas for Cultural Training

Cultural training plays a pivotal role in helping employees navigate the nuances of a foreign culture. This training should encompass areas such as communication styles, social norms, and business etiquette. Cultural sensitivity training ensures that employees can integrate seamlessly into their new environment and foster positive relationships with local colleagues and clients.

Provide Support On The Ground

Supporting employees on the ground is essential for their well-being and success during international assignments. Employers can offer assistance with housing, transportation, and settling-in services. At Leo Packers and Movers, we specialize in facilitating smooth transitions by managing logistics and ensuring that employees have the support they need.

Establishing clear timelines for each phase of the international assignment is critical. This includes planning the move, pre-move training, arrival in the host country, and ongoing support. Having a well-structured timeline ensures that all aspects of the assignment are coordinated and that employees are prepared at every stage.

Preparing employees for international assignments requires careful planning and attention to detail. At Leo Packers and Movers, we understand the importance of a seamless relocation process. By providing pre-move training, addressing potential challenges, offering cultural training, and ensuring on-ground support, employers can ensure that their employees are well-prepared and equipped to thrive in their international assignments. Clear timelines help streamline the process and ensure a successful transition for everyone involved.

Embarking on an international assignment is a significant undertaking for both employees and their employers. Preparing employees adequately for the challenges of living and working in a foreign country is essential to ensure their success and well-being. At Leo Packers and Movers, we understand the intricacies of international relocation services . In this guide, we will explore the various aspects of preparing employees for international assignments, including pre-move training, potential challenges, areas for cultural training, on-ground support, and timelines.

The information provided on this website is for general informational purposes only. Service availability may vary, and we recommend consulting with us to confirm the suitability and availability of any Leo Packers and Movers services before making any requests or decisions based on the information presented here.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related News

International Moving Insurance: Types, Costs, and Expert Insights

You may have missed.

Why Hire Professional Packers & Movers for A Intercity Moving Services

Quality Packers and Movers Checklist

Moving to Bangalore? Top 10 Things You Should Know

Long-term vs. Short-term Storage Services: Which Option is Right for You?

Comparing Storage Services: Self-Storage, Warehousing, and More

The Pros and Cons of Door-to-Door Vehicle Shipping in India

- Help & FAQ

Selection for international assignments

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › peer-review

The selection of individuals to fill international assignments is particularly challenging because the content domain for assessing candidates focuses primary attention on job context rather than attempting to forecast the ability to perform specific tasks on the job or more generally, the elements listed in a technical job description. International assignment selection systems are centered on predicting to the environment in which the incumbents will need to work effectively rather than the technical or functional job they are being asked to do which in many cases is already assessed or assumed to be at an acceptable level of competence. Therefore, unlike predictors of success in the domestic context where knowledge, skills, and abilities may dominate the selection strategy, many psychological and biodata factors including personality characteristics, language fluency, and international experience take on increasing importance in predicting international assignee success. This article focuses on the predictors affecting the outcome of international assignments and the unique selection practices, which can be employed in selection for international assignments. In addition, this article discusses the practical challenges for implementing the suggestions for selecting international assignees.

All Science Journal Classification (ASJC) codes

- Applied Psychology

- Organizational Behavior and Human Resource Management

Access to Document

- 10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.02.001

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

- Link to the citations in Scopus

Fingerprint

- International Assignments Business & Economics 100%

- Job Description Medicine & Life Sciences 57%

- Predictors Business & Economics 39%

- Mental Competency Medicine & Life Sciences 35%

- Personality Medicine & Life Sciences 33%

- Biodata Business & Economics 30%

- Language Medicine & Life Sciences 29%

- Psychology Medicine & Life Sciences 25%

T1 - Selection for international assignments

AU - Caligiuri, Paula

AU - Tarique, Ibraiz

AU - Jacobs, Rick

PY - 2009/9

Y1 - 2009/9

N2 - The selection of individuals to fill international assignments is particularly challenging because the content domain for assessing candidates focuses primary attention on job context rather than attempting to forecast the ability to perform specific tasks on the job or more generally, the elements listed in a technical job description. International assignment selection systems are centered on predicting to the environment in which the incumbents will need to work effectively rather than the technical or functional job they are being asked to do which in many cases is already assessed or assumed to be at an acceptable level of competence. Therefore, unlike predictors of success in the domestic context where knowledge, skills, and abilities may dominate the selection strategy, many psychological and biodata factors including personality characteristics, language fluency, and international experience take on increasing importance in predicting international assignee success. This article focuses on the predictors affecting the outcome of international assignments and the unique selection practices, which can be employed in selection for international assignments. In addition, this article discusses the practical challenges for implementing the suggestions for selecting international assignees.

AB - The selection of individuals to fill international assignments is particularly challenging because the content domain for assessing candidates focuses primary attention on job context rather than attempting to forecast the ability to perform specific tasks on the job or more generally, the elements listed in a technical job description. International assignment selection systems are centered on predicting to the environment in which the incumbents will need to work effectively rather than the technical or functional job they are being asked to do which in many cases is already assessed or assumed to be at an acceptable level of competence. Therefore, unlike predictors of success in the domestic context where knowledge, skills, and abilities may dominate the selection strategy, many psychological and biodata factors including personality characteristics, language fluency, and international experience take on increasing importance in predicting international assignee success. This article focuses on the predictors affecting the outcome of international assignments and the unique selection practices, which can be employed in selection for international assignments. In addition, this article discusses the practical challenges for implementing the suggestions for selecting international assignees.

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=67649531910&partnerID=8YFLogxK

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/citedby.url?scp=67649531910&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.02.001

DO - 10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.02.001

M3 - Article

AN - SCOPUS:67649531910

SN - 1053-4822

JO - Human Resource Management Review

JF - Human Resource Management Review

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Sociol

How do Individuals Form Their Motivations to Expatriate? A Review and Future Research Agenda

Vilmante Kumpikaite-Valiuniene , Kaunas University of Technology, Lithuania

For two decades, individual motivations to expatriate have received substantial attention in the expatriation literature examining self-initiated and assigned expatriation. Recently, however, this literature has changed direction, demonstrating that prior to forming their actual motivations, individuals undergo a process wherein they actively form those motivations. No review has yet unraveled this motivation process, and this systematic literature review fills this gap. Using the Rubicon Action model that discusses the motivation process of expatriation, this article demonstrates that for self-initiated and assigned expatriation, individuals follow similar processes: expatriation expectations are formed; then, they are evaluated; and finally, preferences are built that result in motivations to expatriate. Findings for each stage are discussed in light of their contributions to the expatriation literature. For major gaps, new research suggestions are offered to advance our understanding of the individual motivation process that expats experience prior to forming their motivations to move abroad.

Introduction

For many countries, expatriation is of paramount importance, especially because it brings in knowledge and talent from abroad, strengthening the competitive advantages of regions and cities within countries ( Ridgway and Robson, 2018 ), and it may even improve a country’s global economic status ( Caligiuri and Bonache, 2016 ). Many countries therefore adopt national and regional strategies to attract talent, as is the case, for example, in the Gulf State of Qatar, where highly skilled expatriates are attracted from Europe, North America, Australia, Egypt, Jordan and the Philippines. The experience, skills and competencies of these expatriates are expected to benefit the country’s stakeholders ( Baruch and Forstenlechner, 2017 ). Also, China welcomes branch campuses of international universities to attract academics from the United Kingdom, Australia and Germany, thus strengthening the country’s human capital ( Cai and Hall, 2016 ). Recognizing the importance of expatriation to countries, researchers have also paid substantial attention to this topic in academic work. This research conducted over the past two decades has identified two main types of expatriation: self-initiated expatriation (SIE) and assigned expatriation (AE) ( Andresen et al., 2014 ; Pinto and Caldas, 2015 ; Farcas and Goncalves, 2017 ). Studies have sought to make better sense of these types of expatriation by studying, in particular, individual motivations to expatriate ( Suutari and Brewster, 2001 ; Hippler, 2009 ; Lee and Kuzhabekova, 2018 ; Ridgway and Robson, 2018 ). Perhaps because individual motivations to expatriate to a specific country reflect the country-level factors that attract talent ( Ridgway and Robson, 2018 ), identifying these factors may thus help countries establish effective strategies to attract more talented individuals. Overall, the research findings in this area demonstrate that individuals that undergo SIE and AE are motivated to move abroad by their desire to explore other job opportunities (e.g., Doherty et al., 2011 ; Froese, 2012 ) or have a general interest in enhancing their career ( Quantin et al., 2012 ). They may also be motivated to move abroad to live in a country that is economically and politically better developed than their home country ( Harry et al., 2017 ).

Interestingly, such motivations to expatriate are not always driven by serendipity, as extant work suggests (e.g., Doherty, 2013 ); thus, individuals may actively pursue a strategy to expatriate ( Shortland, 2018 ). This suggests that prior to actual expatriation, individuals go through a process that influences their motivation to expatriate. Confirming this thinking, Glassock and Fee (2015) demonstrate that individuals use social media to actively look for vacancies abroad, a practice that likely influences their motivation to expatriate to a specific country because social media can provide information about job markets in different countries. Likewise, Harris and Brewster (1999) and Shortland (2018) argue that managers utilize their informal networks to look for opportunities to work abroad, which also likely influences their actual motivation to move and work abroad because they can evaluate whether expatriation will benefit their careers ( Pinto and Caldas, 2015 ). Thus, not only do individuals go through a process that influences how and why specific expatriation motivations are formed, but they also seem to have an active role in guiding this process (i.e., triggering their own motivations to expatriate). While this knowledge is clearly discussed in the extant expatriation literature, no review has yet unraveled this individual motivation process (e.g., Al Ariss and Crowley-Henry, 2013 ; Doherty, 2013 ; Andresen et al., 2014 ; Caligiuri and Bonache, 2016 ; Farcas and Goncalves, 2017 ). Therefore, it is not known how and why individuals form specific motivations to expatriate and what their active role is in forming their own motivation. The purpose of this paper is to fill in this gap by systematically reviewing articles examining individuals’ motivations to expatriate via SIE and AE. By doing so, we particularly focus on 1) whether the articles discuss the process that individuals go through in forming their motivations to expatriate and 2) whether they have an active role in forming their own motivations. To unravel this motivation process, we draw upon the Rubicon model of action phases ( Heckhausen and Gollwitzer 1987 ; Heckhausen and Heckhausen, 2018 ), which discusses the entire decision-making process of individual expatriation. According to Andresen et al. (2014) , motivations are formed in this model through a series of steps: individuals actively form their expectations towards expatriation, then take an active role in evaluating their options to move as SIEs or AEs, and then actively build their preferences for moving somewhere. According to the authors, both SIEs and AEs go through the same stages, and hence, the motivation process is supposed to be the same for both groups.

This article makes two important contributions to the expatriation literature. First, it contributes to extant literature review papers on expatriation motivations by unraveling the process behind the actual motivations. We therefore provide greater understanding of the process that individuals go through when they are pushed towards expatriation ( Doherty, 2013 ; Glassock and Fee, 2015 ). Second, we aim to demonstrate that as individuals go through that process, they have an active role in forming their own motivations to expatriate. We therefore contribute to extant work that argues that motivations to expatriate are driven by more than just serendipity (e.g., Doherty, 2013 ) by providing explanations for why this is indeed the case. In the remainder of this article, we define SIE and AE and provide a brief overview of their motivations to expatriate, followed by an explanation of the motivation process in expatriation. We then discuss how we have conducted our review and present our findings. Finally, we discuss future research areas that will further enhance our understanding of how and why motivations to expatriate are formed.

Defining Self-Initiated and Assigned Expatriation

Self-initiated expatriation.

We follow Doherty (2013) and Al Ariss and Crowley-Henry (2013) , who define SIE as denoting internationally mobile individuals who have moved—through their own agency or through an organizationally supported expatriation—to another country for an indeterminate duration. SIEs are considered migrants if they decide to stay in the host country permanently ( Al Ariss and Özbilgin, 2010 ). Because motivations to undertake expatriation are also influenced by demographic characteristics (e.g., Selmer and Lauring, 2010 ; Doherty et al., 2011 ; Lauring et al., 2014 ), it is worthwhile to mention the demographic characteristics of both SIEs and AEs. SIEs tend to be represented by slightly younger individuals, who may be unmarried or married and accompanied by their spouses in their expatriation ( Suutari and Brewster, 2000 ). Individuals studied under the banner of SIEs include graduates (e.g., Suutari and Brewster, 2001 ), academics (e.g., Lee and Kuzhabekova, 2018 ), doctors (e.g., Humphries, et al., 2015 ), entrepreneurs (e.g., Selmer et al., 2018 ) and managers, technicians and other professionals ( Ewers and Shockley, 2018 ).

Assigned Expatriation

We follow the definition of AE used in prior work but emphasize that individuals do have some choice in accepting or declining job assignments and that they may also actively initiate their own AE ( Harris and Brewster, 1999 ). Hence, we define AE as denoting employees who undertake a sponsored expatriation because they have been assigned to a foreign subsidiary by their parent organization, which was either a result of their own initiative (e.g., Harris and Brewster, 1999 ) or their employer’s initiative but where they had the choice to accept or decline the offer ( Andresen et al., 2014 ; Cerdin and Selmer, 2014 ). AEs tend to be slightly older and represented more by married males who are also accompanied by their spouses and families ( Suutari and Brewster, 2000 ). Furthermore, AEs tend to be more represented by top managers ( Pinto et al., 2012 ; Pinto and Caldas, 2015 ).

Motivations to Expatriate for SIE and AE

Prior work demonstrates that the motivations of SIEs to move abroad have been largely explained by push and pull factors (e.g., Thorn, 2009 ; Doherty, 2013 ; Lee and Kuzhabekova, 2018 ). SIEs move abroad to improve their lifestyle and quality of life ( Marian, 2010 ); thus, career opportunities, cultural exposure, and economic and political factors are push factors motivating them to move abroad (e.g., Richardson and McKenna, 2002 ; Thorn et al., 2013 ), while family considerations tend to operate as pull factors towards the home context, demotivating individuals from initiating expatriation ( Jackson et al., 2005 ). AEs move abroad to fill managerial and technical positions in the host country ( Caligiuri and Bonache, 2016 ). Push factors triggering AEs to expatriate are—in addition to pressure from superiors ( Pinto et al., 2012 ; Pinto and Caldas, 2015 )—gaining new challenging international work experience, progressing in one’s career and wanting to learn more about oneself ( Hippler, 2009 ). Similar to SIEs, AEs are concerned with pursuing personal and professional development ( Baruch and Forstenlechner, 2017 ). AEs are also concerned with their partner’s and children’s attitude towards relocation; hence, family considerations tend to also operate as pull factors towards the home context, triggering individuals to decline international job offers ( Doherty et al., 2011 ; Froese, 2012 ). Indeed, Doherty and her collaborators (2011) compared the motivations of SIEs and AEs and concluded that career considerations may be important for both groups but are significantly more important to AEs because their international experience is coupled with career development and progression. For SIEs, the status of the host country is a much stronger pull factor towards expatriation, likely influencing where individuals decide to pursue their career path. Because career motivations still apply to both SIEs and AEs and because cultural, economic and political factors are country-level factors attracting expats ( Jackson et al., 2005 ; Doherty et al., 2011 ), we use the categories career, economy , politics and culture to analyze and report our findings regarding the motivations of SIEs and AEs to go abroad and the processes underlying these motivations. Our career category involves motivations related to the subjective career, which is an individual’s sense or evaluation of his or her own career needs and development ( Volmer and Spurk, 2011 ); this concept refers, for example, to career aspirations, employment security and access to learning and development ( Arthur et al., 2005 ). This category also involves motivations related to one’s objective career, which refers to visible indicators of individuals’ career positions, situations and status ( Arthur et al., 2005 ); it involves income, family situation, task attributes, mobility and job level ( van Maanen, 1977 , p. 9). Our economy category includes motivations derived from a country’s wealth level, which refers, for example, to regulations that exempt residents from paying taxes ( Humphries et al., 2015 ), leaving them with a higher net income ( Alonso-Garbayo and Maben, 2009 ). Our politics category involves motivations derived from factors relating to the politics of a country ( Thorn, 2009 ), such as immigration policies and the freedom to practice different religions ( Alonso-Garbayo and Maben, 2009 ), such as its food, language, habits and any other cultural activities.

Motivation Process

Before actual expatriation motivations are formed, both SIEs and AEs go through a similar process where expatriation expectations are determined, alternatives are evaluated and preferences are built ( Andresen et al., 2014 ). This motivation process has been explained in extant work using the Rubicon model of action phases ( Heckhausen and Gollwitzer, 1987 ; Andresen et al., 2014 ; Heckhausen and Heckhausen, 2018 ; Andresen et al., 2014 ), where in the first stage of the process, individuals start creating a diffuse idea about the benefits of moving abroad in order to address their individual motivations; this idea forms their expatriation expectations . Individuals have an active role triggering their own expectations, as individuals’ perceptions about the benefits of moving abroad develop when they are making sense of the expatriation experiences of others ( Kim, 2010 ). SIEs tend to form expectations by using input from multiple external sources, such as friends, family and the internet ( Glassock and Fee, 2015 ). On the other hand, in forming their expatriation expectations, AEs derive input and clues from colleagues who have already been sent on similar international postings ( Pinto and Caldas, 2015 ). Once expectations are formed, individuals continue in the second stage by evaluating their options to expatriate ( Andresen et al., 2014 ). This stage implies that they can consider taking the initiative to apply for a job abroad without seeking any organizational support or assistance (SIE) ( Suutari and Brewster, 2000 ). If individuals perceive that such actions will likely be unsuccessful, they may consider seeking assistance from recruitment agencies ( Farcas and Goncalves, 2017 ), use social networks (i.e., friends, family) to find a job abroad ( Baruch and Forstenlechner, 2017 ), or seek support from a company that is willing to support their expatriation ( Alonso-Garbayo and Maben, 2009 ). This company could be the individual’s current employer (AE) ( Cuhlova, 2017 ) or a company abroad seeking to recruit foreigners (SIE) (e.g., Alonso-Garbayo and Maben, 2009 ). Thus, in this stage, tools and other resources are likely used to evaluate options for expatriation.

The final stage, where preferences are built, is influenced by valence and expectancy parameters ( Vroom, 1964 ). Valence can be interpreted as the anticipated satisfaction with an outcome, whereas expectancy can be interpreted as an action or effort leading to the preferred outcome ( Vroom, 1964 ). In terms of expatriation, this definition implies that individuals prefer to expatriate to a country where they expect to have the most opportunities to address their individual and family needs. Such a country will be a preferred location if it offers more job opportunities, higher salaries and better assignment packages than other countries, as well as a safe environment to raise a family ( Jackson et al., 2005 ; Froese, 2012 ; Lee and Kuzhabekova, 2018 ; Richardson and Wong, 2018 ).

Methodology

The purpose of a systematic literature review is to develop conceptual consolidation across a fragmented field of study and to remove subjectivity by using a predefined selection algorithm ( Tranfield et al., 2003 ). In this sense, we also systematically reviewed articles about individual motivations to go abroad to unravel the individual process behind the actual motivations. In line with Tranfield et al. (2003) systematic review methodology, we also performed the three steps of data collection, data analysis and reporting the findings, which we discuss further below.

Data Collection

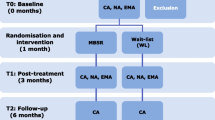

We conducted a series of searches using the ISI Web of Knowledge Database. This database has been used in prior similar work (e.g., Al-Ariss and Crowley-Henry, 2013 ; Farcas and Goncalves, 2017 ; Davda et al., 2018 ) because it includes all journals that have an impact factor and are listed in the Social Science Citation Index; hence, these journals are recognized to have an impact in the expatriation field. We found that the first article examining motivations to expatriate was published in 1994. Our initial search started in 2019 and was therefore focused on identifying articles that were published in the period between 1994 and 2019. We limited the scope of our review by using the key words “expatriate”, “migrant” and “digital nomad” combined with the additional key words “motive”, “motiv”, and “reason” because these terms are mainly used in articles studying motivations in the expatriation literature (e.g., Doherty et al., 2011 ; Harry et al., 2017 ). This search returned 919 results. Then, 148 duplicate articles were removed automatically by the web of science, leaving us with 771 articles. We then proceeded to read the abstracts of all 771 articles and excluded another 710 articles because the topics of those articles did not match the purpose of our review. The excluded articles discussed topics such as medical tourism behavior ( Mathijsen, 2019 ), psychological contract perspectives on expatriation failure ( Kumarika Perera et al., 2017 ) and cultural leadership behavior ( Kennedy, 2018 ). All remaining 61 articles were included for full text review, but only 44 articles were included in the final sample because these articles examine individual motivations to expatriate, are empirical studies (i.e., quantitative and qualitative studies) and are written in English. Therefore, literature review articles and empirical studies written in a language other than English were excluded from the final sample. In 2021, we followed the same search strategy to explore whether new articles were published between 2019 and 2021. This search added two articles to the final sample. One additional article was added as it was suggested by a reviewer. The final sample includes 47 articles. Figure 1 shows our data collection visually, and Table 1 includes a bibliography of all included articles.

Data collection.

Overview of articles included in final sample.

Data Analysis

To analyze our data, we set up a table with thematic codes that included the 1) Name (s) of the author (s); 2) Title; 3) Year of publication; 4) Journal Title; 5) Methodology; 6) Sample; 7) Expatriation type (SIE or AE) 8) Gender; 9) Occupation; (10) Motivation to expatriate; 11) Push and pull factors influencing the motivation process of all four motivations; and 12) Country, (i.e., home or host country). The motivation categories were derived from prior work examining motivations to expatriate and included, as discussed above, career, economy, politics and culture. Finally, the tables were filled in for the self-initiated and assigned expatriates separately.

Expatriation Motivations and Processes

We found thirty-four articles identifying career as a motivation to expatriate for both SIEs and AEs (SIE, N = 23; AE, N = 11). Among these articles, thirty-four discuss expatriation expectations, twenty-nine discuss how individuals expatriate (as SIE or AE), and fifteen demonstrate that individuals developed preferences to expatriate to a specific country. Below, we discuss our findings by applying them to the three stages of the motivation process.