Homework policy: examples

See examples of homework policies from primary, secondary and special schools to help you write your own. also, adapt our sample clause for handling the impact of ai tools on homework., primary school, secondary school, special school, multi-academy trust, sample ai clause.

Shadwell Primary School in Leeds has a homework policy that covers:

- When pupils take books home for reading

- How long they should spend reading at home

- English and maths homework

- Spelling and times tables expectations

- Additional half-termly homework tasks, such as a learning log and key instant recall facts

- Instances when pupils may receive additional homework

- How homework will be recorded

- Rewards and sanctions

Chelmsford County High School for Girls in Essex has a school-wide homework policy setting out:

- The importance of homework

- Types of homework that could be set

- How much time different year groups should spend on homework

North Ridge High School in Manchester has a homework policy that explains:

- How homework may differ in form, expectations and outcomes

- How long the school recommends pupils spend on homework

- The roles of the class teacher, leadership team and governing board, and parents and carers

- The homework that different Key Stages and learners will get

- Marking, feedback and pupil absence

The policy also includes a homework timetable.

STEP Academy Trust has homework policies set for its schools that are agreed by the board of trustees. Each policy has been adapted slightly for each school.

To find the homework policies , scroll down in the 'Policy' search box in the top-right corner, and select 'STEP homework policy' – you'll see a list with links to homework policies for each of the trust's schools.

The DfE has advised that you may wish to review your homework policy to consider the impact of generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools (such as ChatGPT and Google Bard) on homework and unsupervised work.

Adapt our example text below to suit your school's context and approach to AI.

Primary schools

Secondary schools.

We're working on some practical guidance to help you get to grips with AI - select 'save for later' in the top right-hand corner of this page to be updated when it's ready.

This article is only available for members

Want to continue reading?

Start your free trial today to browse The Key Leaders and unlock 3 articles.

Already a member? Log in

Start getting our trusted advice

- Thousands of up-to-the-minute articles

- Hundreds of templates, letters and proformas

- Lawyer-approved model policies

Creating a Homework Policy With Meaning and Purpose

- Tips & Strategies

- An Introduction to Teaching

- Policies & Discipline

- Community Involvement

- School Administration

- Technology in the Classroom

- Teaching Adult Learners

- Issues In Education

- Teaching Resources

- Becoming A Teacher

- Assessments & Tests

- Elementary Education

- Secondary Education

- Special Education

- Homeschooling

- M.Ed., Educational Administration, Northeastern State University

- B.Ed., Elementary Education, Oklahoma State University

We have all had time-consuming, monotonous, meaningless homework assigned to us at some point in our life. These assignments often lead to frustration and boredom and students learn virtually nothing from them. Teachers and schools must reevaluate how and why they assign homework to their students. Any assigned homework should have a purpose.

Assigning homework with a purpose means that through completing the assignment, the student will be able to obtain new knowledge, a new skill, or have a new experience that they may not otherwise have. Homework should not consist of a rudimentary task that is being assigned simply for the sake of assigning something. Homework should be meaningful. It should be viewed as an opportunity to allow students to make real-life connections to the content that they are learning in the classroom. It should be given only as an opportunity to help increase their content knowledge in an area.

Differentiate Learning for All Students

Furthermore, teachers can utilize homework as an opportunity to differentiate learning for all students. Homework should rarely be given with a blanket "one size fits all" approach. Homework provides teachers with a significant opportunity to meet each student where they are and truly extend learning. A teacher can give their higher-level students more challenging assignments while also filling gaps for those students who may have fallen behind. Teachers who use homework as an opportunity to differentiate we not only see increased growth in their students, but they will also find they have more time in class to dedicate to whole group instruction .

See Student Participation Increase

Creating authentic and differentiated homework assignments can take more time for teachers to put together. As often is the case, extra effort is rewarded. Teachers who assign meaningful, differentiated, connected homework assignments not only see student participation increase, they also see an increase in student engagement. These rewards are worth the extra investment in time needed to construct these types of assignments.

Schools must recognize the value in this approach. They should provide their teachers with professional development that gives them the tools to be successful in transitioning to assign homework that is differentiated with meaning and purpose. A school's homework policy should reflect this philosophy; ultimately guiding teachers to give their students reasonable, meaningful, purposeful homework assignments.

Sample School Homework Policy

Homework is defined as the time students spend outside the classroom in assigned learning activities. Anywhere Schools believes the purpose of homework should be to practice, reinforce, or apply acquired skills and knowledge. We also believe as research supports that moderate assignments completed and done well are more effective than lengthy or difficult ones done poorly.

Homework serves to develop regular study skills and the ability to complete assignments independently. Anywhere Schools further believes completing homework is the responsibility of the student, and as students mature they are more able to work independently. Therefore, parents play a supportive role in monitoring completion of assignments, encouraging students’ efforts and providing a conducive environment for learning.

Individualized Instruction

Homework is an opportunity for teachers to provide individualized instruction geared specifically to an individual student. Anywhere Schools embraces the idea that each student is different and as such, each student has their own individual needs. We see homework as an opportunity to tailor lessons specifically for an individual student meeting them where they are and bringing them to where we want them to be.

Homework contributes toward building responsibility, self-discipline, and lifelong learning habits. It is the intention of the Anywhere School staff to assign relevant, challenging, meaningful, and purposeful homework assignments that reinforce classroom learning objectives. Homework should provide students with the opportunity to apply and extend the information they have learned complete unfinished class assignments, and develop independence.

The actual time required to complete assignments will vary with each student’s study habits, academic skills, and selected course load. If your child is spending an inordinate amount of time doing homework, you should contact your child’s teachers.

- Homework Guidelines for Elementary and Middle School Teachers

- 6 Teaching Strategies to Differentiate Instruction

- An Overview of Renaissance Learning Programs

- Essential Strategies to Help You Become an Outstanding Student

- Classroom Assessment Best Practices and Applications

- How Scaffolding Instruction Can Improve Comprehension

- The Whys and How-tos for Group Writing in All Content Areas

- Gradual Release of Responsibility Creates Independent Learners

- Creating a Great Lesson to Maximize Student Learning

- How Much Homework Should Students Have?

- 7 Reasons to Enroll Your Child in an Online Elementary School

- Teaching Strategies to Promote Student Equity and Engagement

- Effective Classroom Policies and Procedures

- Collecting Homework in the Classroom

- 5 Types of Report Card Comments for Elementary Teachers

- Methods for Presenting Subject Matter

Frog Education

- Schools & Education

- Professional Development

- Special Projects

- Global Initiatives

The power of a good homework policy

Published 18th March 2019 by Frog Education

With the homework debate continuing to rage and be fuelled by all parties involved, could publishing a robust homework policy help take some of the headache out of home learning?

What is a homework policy.

The idea of a homework policy is for the school to officially document and communicate their process for homework. The policy should outline what is expected of teachers when setting homework and from students in completing home learning tasks. It is a constructive document through which the school can communicate to parents, teachers, governors and students the learning objectives for homework.

Do schools have to have a homework policy?

It is a common misconception that schools are required by the government to set homework. Historically the government provided guidelines on the amount of time students should spend on home learning. This was withdrawn in 2012 and autonomy was handed to headteachers and school leaders to determine what and how much homework is set. Therefore, schools are not required by Ofsted or the DfE to have a homework policy in place.

The removal of official guidelines, however, does not give pupils the freedom to decide if they complete homework or not. Damian Hinds , Education Secretary, clarified that although schools are not obliged to set homework, when they do, children need to complete it in line with their school’s homework policy; “we trust individual school head teachers to decide what their policy on homework will be, and what happens if pupils don’t do what’s set.”

The majority of primary and secondary schools do set homework. Regardless of the different views on the topic, the schools that do incorporate homework into their learning processes, must see value in it.

Clearly communicating that value will demonstrate clarity and create alliance for everyone involved – both in and outside of school. This is where the publication of a good homework policy can help. 5 Benefits of publishing a good homework policy

#1 Manages students' workload

Studies have shown a correlation between student anxiety and demanding amounts of homework. One study found that in more affluent areas, school children are spending three hours per evening on homework. This is excessive. Secondary school students’ study between eight and ten subjects, which means they will have day-to-day contact with a number of teachers. If there is no clear homework policy to provide a guide, it would be feasible for an excessive amount of homework to be set.

A homework policy that sets out the expected amount of time students should spend on homework will help prevent an overload. This makes it more realistic for children to complete homework tasks and minimise the detrimental effect it could have on family time, out-of-school activities or students’ overall health and well-being.

#2 Creates opportunity for feedback and review

The simple act of having an official document in place will instigate opportunities for regular reviews. We often consider the impact of homework on students but teachers are also working out-of-hours and often work overtime . One reason is the need to set quality homework tasks, mark them and provide valuable feedback. No-one, therefore, wants home learning to become about setting homework for homework’s sake.

A regular review of the policy will invite feedback which the school can use to make appropriate changes and ensure the policy is working for both teachers and students, and serves the school’s homework learning objectives.

#3 Connects parents with education

Parents’ engagement in children’s education has a beneficial impact on a child’s success in school. Homework provides a great way for parents to become involved and have visibility of learning topics, offer support where needed and understand their child’s progress.

A good homework policy creates transparency for parents. It helps them to understand the value the school places on homework and what the learning objectives are. If parents understand this, it will help set a foundation for them to be engaged in their child’s education.

#4 Gives students a routine and creates good habits

Whether children are going into the workplace or furthering their education at university, many aspects of a student’s future life will require, at times, work to be completed outside of traditional 9-5 hours as well as independently. This is expected at university (students do not research and write essays in the lecture theatre or their seminars) and will perhaps become more important in the future workplace with the growth of the gig economy (freelancing) and the rise of remote working .

A homework policy encourages a consistency for out-of-school learning and helps students develop productive working practices and habits for continued learning and independent working.

#5 Helps students retain information they have learned

A carefully considered and well-constructed home learning policy will help teachers set homework that is most effective for reinforcing what has been taught.

A good homework policy will indicate how to set productive homework tasks and should limit the risk of less effective homework being set, such as just finishing-off work from a lesson and repetition or memorisation tasks. What makes a good homework policy?

A good homework policy will determine how much homework is appropriate and what type is most effective for achieving a school’s learning objectives. Publishing the homework policy – although it might not unify everyone’s views on the matter – fosters good communication across the school, sets out expectations for teachers and pupils, and makes that significant connection between parents and their children’s education. But most importantly, if the policy is regularly reviewed and evaluated, it can ensure home learning remains beneficial to pupils’ progress, is of value to teachers and, ultimately, is worth the time and effort that everyone puts into it.

Frog 's Homework Solu tion

If you'd like to see better results from homework and independent learning, you should see HomeLearning in action!

- Set and mark online and offline homework in seconds - Access 300,000 curriculum-mapped quizzes using FrogPlay - Track homework setting and completions in MarkBook - Provide full visibility for parents, leaders, staff and pupils - Encourage independent learning

Get a demo of HomeLearning :

Speak to Frog

Back to Blog Listing

- Home Learning

- homework policy

Related Posts

We believe that every child can be given a unique and personal education, and that this can be delivered by today’s teachers without increasing workload through the clever use of technology.

+44 (0)1422 250800

Dean Clough Mills, Halifax HX3 5AX Find on Google Maps

Blog The Education Hub

https://educationhub.blog.gov.uk/2018/10/28/education-secretary-i-trust-head-teachers-to-decide-their-homework-policies/

Education Secretary: I trust head teachers to decide their homework policies

Education Secretary Damian Hinds has today written an op-ed for the Sunday Times setting out his position on homework, which has been followed up with a news story . He says that ultimately up to heads and school leaders to decide whether to set homework and what the consequences should be if children do not complete their homework set.

The Education Secretary said:

One of the tougher things I’ve taken on recently was solving a ‘part-whole model’, involving nine ducks and a jagged shoreline. This was, I should clarify, a piece of homework for one of my children, not something called for in my day job. Homework is a staple of school life, and of home life. Parents know this. After all, almost every one of us will have done homework ourselves as a child and most of us will be drafted in to help with it at some point as a parent, carer or grandparent. There has been some high-profile interest of late on social media suggesting that homework is bad for children, at least in the first half of schooling. There have even been subsequent questions about its legal status. Just to be clear: schools are not obliged to set homework, and some don’t. But when schools do set homework, children do need to do it. We trust individual school head teachers to decide what their policy on homework will be, and what happens if pupils don’t do what’s set. Policy and approach won’t be the same in all cases. Autonomy for schools, and the diversity that comes with it, is at the heart of this government’s approach to education. Of course, schools should, and do, communicate with parents. Parents need to know where they stand. Teachers obviously need to be realistic about expectations, and they know this. Obviously, no one wants children spending an inordinate amount of time every night doing homework. Clearly, there are other important things to do, too – like playing outside, family time, eating together. Good homework policies avoid excessive time requirements – focusing on quality rather than quantity and making sure that there is a clear purpose to any homework set. In 2011 we helped set up the Education Endowment Foundation as an independent expert body to study and advise on “what works” in education. It has established that, although there are more significant educational improvements derived from homework at secondary school, there can still be a modest but positive impact at primary level. Homework isn’t just some joyless pursuit of knowledge. It’s an integral part of learning. Beyond the chance to practice and reinforce what you’ve learned in class, it’s also an opportunity to develop independent study and application – and character traits like perseverance. Children need to know that what they do has consequences. At secondary school, if a pupil doesn’t complete their homework, they risk falling behind. They may also hold up others – clearly it is harder for the teacher to keep the whole class moving forward if some are doing the homework and others aren’t. At primary school, too, we all want our children to develop their knowledge – but we also want them to develop values. Homework set at primary school is likely to be of relatively shorter duration. But if a child is asked to do it and they don’t, for that to have no consequence would not be a positive lesson. Ultimately, of course, the responsibility for a child’s educational development is a shared one. Parental involvement makes a big difference, from the very earliest stage. In the early years parents can support their child’s development through story telling, singing or reading together. Later on, homework can give an ‘in’ for continued involvement in learning. Homework should not in general require adult help, and with today’s busy lives it certainly can be hard to find the time. But I know as a parent that we are called on as reinforcements if an assignment is especially challenging. Other times, it falls to parents just to give a nudge. I want all children to enjoy their progress through school and they will have a much better chance of doing this if they are not having to play catch-up during the day. Parents need to trust teachers, with all their experience of teaching and learning – and know that their child’s homework is not just proportionate, but will be of lasting benefit. From motivation and self-discipline to the wonder of independent learning, homework can teach children about far more than the part-whole model, some ducks and a jagged shoreline.

Follow us on Twitter and don't forget to sign up for email alerts .

Sharing and comments

Share this page, related content and links, about the education hub.

The Education Hub is a site for parents, pupils, education professionals and the media that captures all you need to know about the education system. You’ll find accessible, straightforward information on popular topics, Q&As, interviews, case studies, and more.

Please note that for media enquiries, journalists should call our central Newsdesk on 020 7783 8300. This media-only line operates from Monday to Friday, 8am to 7pm. Outside of these hours the number will divert to the duty media officer.

Members of the public should call our general enquiries line on 0370 000 2288.

Sign up and manage updates

Follow us on social media, search by date, comments and moderation policy.

- Admissions 1st year 2024

- Transfer Application Form

- Our Standards

- Contacts within the School

- Senior & Middle Leadership Team

- Board of Management

- Our Curriculum

- Programmes Offered

- Leaving Certificate

- Leaving Certificate Vocational Programme (LCVP)

- Junior Certificate

- TY Criteria

- Extra Curricular

- Tutors and Year Heads

- Mission Statement

- School Ethos

- Strategic Plan

- Inspection Reports

- State Exams

- Department Sites

- Past Pupils’ Union

- Information for 2023/2024

- Incoming First Years 2024/2025

- Student Calendar

- Important Letters

- Absences/Vsware/Uniform/School Timetable/School Map

- Vsware Payments/Financial Information/Assistance

- IPad Information

- iPad in the Home: Parenting Tips

- iPad Presentations by Wriggle

- Top 10 Simple Fixes

- Parent Teacher Student Meetings & Conferences

- Supervised Study

- Parent Information Nights

- Parents’ Council

- School Policies

- Newsletters

- Job Applications

- Online Store

Contact us today

Homework & Study Policy

Presentation Secondary School, Wexford aims to provide the best possible environment in which to facilitate the cultural, educational, moral, physical, religious, social, linguistic and spiritual values and traditions of all students. We show special concern for the disadvantaged and we make every effort to ensure that the uniqueness and dignity of each person is respected, and responded to, especially through the pastoral care system in the school.

- We strive for quality in teaching and learning. The main objective of teaching in our school is to increase the knowledge, understanding and skills of all students. Learning, the process to acquire knowledge and these skills, is built upon and shaped in the classroom learning environment.

- The Homework and Study policy is a guide for students, teachers and parents on how to improve classroom learning and fulfil students’ true potential. It is intended to foster self-discipline, independent learning and encourage students to take responsibility for their own learning. Learning is a lifelong skill and many strategies can be employed to improve learning. Homework reinforces and extends classroom learning. Assessment for Learning helps students to manage their learning. Study and revision embed that learning.

- It is essential that students engage and participate in the learning process. To assist learning students need to develop good classroom skills, learn to plan, manage and organise their work and time at home, develop strategies to improve learning and memory and refine study.

Pleas see full policy below:

homeworkpolicy

Lev Moscow offers advice for secondary school teachers

We interview Lev Moscow who, for the last 14 years, has taught history and economics at The Beacon School in New York City. Lev reflects that advisory, done well, can serve as a venue for students to explore questions of ethics, purpose and happiness. He talks about balancing the history curriculum to include non-European perspectives. Getting students to read more than a few sentences is perhaps today’s teachers’ greatest challenge and Lev explains his approach.

*References, overview and transcript below.

Lev refers to John Dewey, Tony Judt, and these resources:

- Book “Kids These Days: Human Capital and the Making of Millennials” by Malcolm Harris;

- Book “The End of Education: Redefining the Value of School” by Neil Postman.

Lev also hosts a podcast that aims to make economics accessible. It is called A Correction Podcast and you can listen to it on acorrectionpodcast.com

00:00-00:57 Intros

00:58-07:24 Advice to new teachers; advisory; Consortium schools (NYC)

07:25-10:47 Electronic technology in the classroom

10:48-12:00 Advisory and relationships

12:01:17:33 Print/reading and digital tech cultures

17:34-19:15 HS versus college cultures

19:16-21:31 Homework

21:32-27:58 Homework (continued): writing, historiography, SQR, short and long-term assignments

27:59-37:37 Language of ethics; ethics and morality; “truth” and skepticism; Dewey; existentialism

37:38-40:14 De-centering Europe in teaching modern Global History

40:15-41:00 Outro

Transcription

Click here to see the full transcription of the episode.

Education Officials and Civil Rights Advocates Testify on Condemning Antisemitism in Schools

K-12 public school officials from California, Maryland, and New York condemned antisemitism and defended their districts' policies, during a… read more

K-12 public school officials from California, Maryland, and New York condemned antisemitism and defended their districts' policies, during a hearing before the House Education and the Workforce Subcommittee on Childhood, Elementary and Secondary Education. The hearing followed multiple allegations of antisemitism in school settings after the deadly October 7, 2023, Hamas terror attacks in southern Israel. close

Javascript must be enabled in order to access C-SPAN videos.

Points of Interest

For quick viewing, C-SPAN provides Points of Interest markers for some events. Click the play button and tap the screen to see the at the bottom of the player. Tap the to see a complete list of all Points of Interest - click on any moment in the list and the video will play.

- Text type Text People Graphical Timeline

- Filter by Speaker All Speakers David Banks Mark DeSaulnier Enikia Ford Morthel Kilili Sablan Karla Silvestre Emerson Sykes Aaron Bean Jamaal Bowman Virginia Foxx Jahana Hayes Kevin Kiley Kathy Manning Lisa McClain Burgess Owens Bobby Scott Elise Stefanik Tim Walberg Brandon Williams

- Search this text

*This text was compiled from uncorrected Closed Captioning.

For quick viewing, C-SPAN provides Points of Interest markers for some events. Click the play button and move your cursor over the video to see the . Click on the marker to see the description and watch. You can also click the in the lower left of the video player to see a complete list of all Points of Interest from this program - click on any moment in the list and the video will play.

People in this video

Hosting Organization

- House Education and the Workforce Subcommittee on Early Childhood, Elementary and Secondary Education House Education and the Workforce Subcommittee on Early Childhood, Elementary and Secondary Education

Airing Details

- May 08, 2024 | 9:16pm EDT | C-SPAN 2

- May 09, 2024 | 3:19am EDT | C-SPAN 2

- May 09, 2024 | 3:09pm EDT | C-SPAN 1

- May 10, 2024 | 1:24pm EDT | C-SPAN RADIO

- May 11, 2024 | 11:20am EDT | C-SPAN RADIO

- May 11, 2024 | 1:07pm EDT | C-SPAN 1

MyC-SPAN users can download four Congressional hearings and proceedings under four hours for free each month.

Related Video

Representative Jamaal Bowman on College Protests Amid Israel-Hamas War

Representative Jamaal Bowman (D-NY) spoke in support of the college protests, amid the Israel-Hamas War.

Speaker Johnson and House Committee Chairs on Antisemitism on College Campuses

Speaker Johnson (R-LA) and House committee chairs spoke about antisemitism and protests on college campuses. They vowed …

University Presidents Testify on College Campus Antisemitism, Part 1

The presidents of Harvard University, the University of Pennsylvania, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT…

University Presidents Testify on College Campus Antisemitism, Part 2

User created clips from this video.

User Clip: K-12 Education Hearing

User Clip: Antisemitism in Schools hearing_CSPAN pt1

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- 110 Baker St. Moscow, ID 83843

- 208.882.1226

A Classical & Christ-Centered Education

Uniform Policy for 2023-24

- Letter from Board Chairman, Luke Jankovic

- 23-24 Uniform (words)

- 23-24 Uniform (pictures)

- Secondary Uniform Notes From Mrs. Miller

- Ties: Elementary ties for boys are available here (be sure to select the classic navy and gold stripe) , crossover ties for elementary girls are found here and secondary ties/scarves are available in the front office.

- Quarter Zips : These quarter zips are uniform-approved for all grades. LINK .

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

Become an FT subscriber

Try unlimited access Only $1 for 4 weeks

Then $75 per month. Complete digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Cancel anytime during your trial.

- Global news & analysis

- Expert opinion

- Special features

- FirstFT newsletter

- Videos & Podcasts

- Android & iOS app

- FT Edit app

- 10 gift articles per month

Explore more offers.

Standard digital.

- FT Digital Edition

Premium Digital

Print + premium digital, weekend print + standard digital, weekend print + premium digital.

Essential digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- Global news & analysis

- Exclusive FT analysis

- FT App on Android & iOS

- FirstFT: the day's biggest stories

- 20+ curated newsletters

- Follow topics & set alerts with myFT

- FT Videos & Podcasts

- 20 monthly gift articles to share

- Lex: FT's flagship investment column

- 15+ Premium newsletters by leading experts

- FT Digital Edition: our digitised print edition

- Weekday Print Edition

- Videos & Podcasts

- Premium newsletters

- 10 additional gift articles per month

- FT Weekend Print delivery

- Everything in Standard Digital

- Everything in Premium Digital

Complete digital access to quality FT journalism with expert analysis from industry leaders. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- 10 monthly gift articles to share

- Everything in Print

Terms & Conditions apply

Explore our full range of subscriptions.

Why the ft.

See why over a million readers pay to read the Financial Times.

International Edition

- Open access

- Published: 13 May 2024

The impact of the world’s first regulatory, multi-setting intervention on sedentary behaviour among children and adolescents (ENERGISE): a natural experiment evaluation

- Bai Li ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2706-9799 1 ,

- Selene Valerino-Perea 2 ,

- Weiwen Zhou 3 ,

- Yihong Xie 4 ,

- Keith Syrett 5 ,

- Remco Peters 1 ,

- Zouyan He 4 ,

- Yunfeng Zou 4 ,

- Frank de Vocht 6 , 7 &

- Charlie Foster 1

International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity volume 21 , Article number: 53 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

59 Altmetric

Metrics details

Regulatory actions are increasingly used to tackle issues such as excessive alcohol or sugar intake, but such actions to reduce sedentary behaviour remain scarce. World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines on sedentary behaviour call for system-wide policies. The Chinese government introduced the world’s first nation-wide multi-setting regulation on multiple types of sedentary behaviour in children and adolescents in July 2021. This regulation restricts when (and for how long) online gaming businesses can provide access to pupils; the amount of homework teachers can assign to pupils according to their year groups; and when tutoring businesses can provide lessons to pupils. We evaluated the effect of this regulation on sedentary behaviour safeguarding pupils.

With a natural experiment evaluation design, we used representative surveillance data from 9- to 18-year-old pupils before and after the introduction of the regulation, for longitudinal ( n = 7,054, matched individuals, primary analysis) and repeated cross-sectional ( n = 99,947, exploratory analysis) analyses. We analysed pre-post differences for self-reported sedentary behaviour outcomes (total sedentary behaviour time, screen viewing time, electronic device use time, homework time, and out-of-campus learning time) using multilevel models, and explored differences by sex, education stage, residency, and baseline weight status.

Longitudinal analyses indicated that pupils had reduced their mean total daily sedentary behaviour time by 13.8% (95% confidence interval [CI]: -15.9 to -11.7%, approximately 46 min) and were 1.20 times as likely to meet international daily screen time recommendations (95% CI: 1.01 to 1.32) one month after the introduction of the regulation compared to the reference group (before its introduction). They were on average 2.79 times as likely to meet the regulatory requirement on homework time (95% CI: 2.47 to 3.14) than the reference group and reduced their daily total screen-viewing time by 6.4% (95% CI: -9.6 to -3.3%, approximately 10 min). The positive effects were more pronounced among high-risk groups (secondary school and urban pupils who generally spend more time in sedentary behaviour) than in low-risk groups (primary school and rural pupils who generally spend less time in sedentary behaviour). The exploratory analyses showed comparable findings.

Conclusions

This regulatory intervention has been effective in reducing total and specific types of sedentary behaviour among Chinese children and adolescents, with the potential to reduce health inequalities. International researchers and policy makers may explore the feasibility and acceptability of implementing regulatory interventions on sedentary behaviour elsewhere.

The growing prevalence of sedentary behaviour in school-aged children and adolescents bears significant social, economic and health burdens in China and globally [ 1 ]–[ 3 ]. Sedentary behaviour refers to any waking behaviour characterised by an energy expenditure equal or lower than 1.5 metabolic equivalents (METs) while sitting, reclining, or lying [ 3 ]. Evidence from systematic reviews, meta-analyses and longitudinal studies have shown that excessive sedentary behaviour, in particular recreational screen-based sedentary behaviour, affect multiple dimensions of children and adolescents’ wellbeing, spanning across mental health [ 4 ], cognitive functions/developmental health/academic performance [ 5 ], [ 6 ], quality of life [ 7 ], and physical health [ 8 ]. In China, over 60% of school pupils use part of their sleep time to play mobile phones/digital games and watch TV programmes, and 27% use their sleep time to do homework or other learning activities [ 9 ]. Screen-based, sedentary entertainment has become the leading cause for going to bed late, which is linked to detrimental consequences for children’s physical and mental health [ 10 ]. Notably, academic-related activities such as post-school homework and off campus tutoring also contribute to the increasing amounts of sedentary behaviour. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report, China is the leading country in time spent on homework by adolescents (14 h/week on average) [ 11 ].

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated this global challenge, with children and adolescents reported to have been the most affected group [ 12 ]. Schools are a frequently targeted setting for interventions to reduce sedentary behaviour [ 13 ]. However, school-based interventions have had limited success when delivered under real-world conditions or at scale [ 14 ]. School-based interventions alone have also been unsuccessful in mitigating the trend of increasing sedentary behaviour that is driven by a complex system of interdependent factors across multiple sectors [ 13 ]. Even for parents and carers who intend to restrict screen-based sedentary behaviour and for children who wish to reduce screen-based sedentary behaviour, social factors including peer pressure often form barriers to changing behaviour [ 15 ]. In multiple public health fields such as tobacco control and healthy eating promotion, there has been a notable shift away from downstream (e.g., health education) towards an upstream intervention approach (e.g., sugar taxation). However, regulatory actions for sedentary behaviour are scarce [ 16 ]. World Health Organization (WHO) 2020 guidelines on sedentary behaviour encourage sustainable and scalable approaches for limiting sedentary behaviour and call for more system-wide policies to improve this global challenge [ 8 ]. Up-stream interventions can act on sedentary behaviour more holistically and have the potential to maximise reach and health impact [ 13 ]. In response to this pressing issue, and to widespread demands from many parents/carers, the Chinese government introduced nationwide regulations in 2021 to restrict (i) the amount of homework that teachers can assign, (ii) when (and for how long) online gaming businesses can provide access to young people, and (iii) when tutoring businesses can provide lessons [ 17 ], [ 18 ]. Consultations with WHO officials and reviewers of international health policy interventions confirmed that this is currently the only government-led, multi-setting regulatory intervention on multiple types of sedentary behaviour among school-aged children and adolescents. A detailed description of this programme is available in the Additional File 1 .

We evaluated the impact of this regulatory intervention on sedentary behaviour in Chinese school-aged children and adolescents. We also investigated whether and how intervention effects differed by sex, education stage, geographical area, and baseline weight status.

Study design

The introduction of the nationwide regulation provided a unique opportunity for a natural experiment evaluation where the pre-regulation comparator group data (Wave 1) was compared to the post-regulation group data (Wave 2). Multiple components of the intervention (see Additional File 1 ) were introduced in phases from July 2021 with all components being fully in place by September 2021 [ 17 ], [ 18 ]. This paper follows the STROBE reporting guidance [ 19 ], [ 20 ].

Data source, study population and sampling

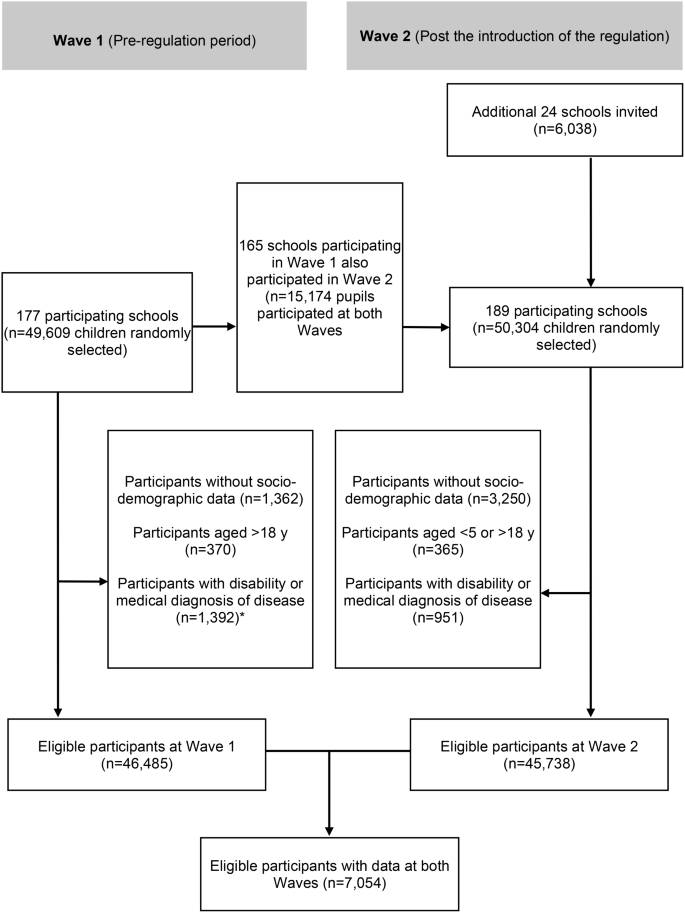

We obtained regionally representative data on 99,947 pupils who are resident in the Chinese province of Guangxi as part of Guangxi Centre for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) routine surveillance. The data, available from participants in grade 4 (aged between 9 and 10 years) and higher, were collected using a multi-stage random sampling design (Fig. 1 ) through school visits by trained health professionals following standardised protocols (see Supplementary Fig. 1 , Additional File 1 ). In Wave 1 (data collected from September to November 2020), pupils were randomly selected from schools in 31 urban/rural counties from 14 cities in Guangxi. At least eight schools, including primary, secondary, high schools, and ‘vocational high schools’, were selected from urban counties. Five schools were selected from rural counties. Approximately 80 students were randomly selected from each grade at the schools selected. The same schools were invited to participate in Wave 2 (data collected from September to November 2021), and new schools were invited to replace Wave 1 schools that no longer participated. Children with available data at both Wave 1 and Wave 2 represented approximately 10% of the sample ( n = 7,587). Paper-based questionnaires were administrated to students by trained personnel or teachers. The questionnaires were designed and validated by China National Health Commission, and have been utilised in routine surveillance throughout the country.

Flow diagram of participants included in the ENERGISE study

We used data from the age groups 7–18 years for most analyses. For specific analyses of homework and out-of-campus tutoring, we excluded high school pupils (16–18 years) because the homework and out-of-campus tutoring regulations apply to primary (7–12 years) and middle (13–15 years) school pupils only. Furthermore, participants without socio-demographic data or those who reported medical history of disease, or a physical disability were excluded. This gave us a total sample of 7,054 eligible school-aged children and adolescents with matching data (longitudinal sample).

Outcomes and subgroups

Guangxi CDC used purposively designed questions for surveillance purposes to assess sedentary behaviour outcomes (Table 1 ).

The primary outcomes of interest included: (1) total sedentary behaviour time, (2) homework time, (3) out-of-campus learning (private tutoring) time, and (4) electronic device use time (Table 1 ). We considered electronic device use time, including mobile phones, handheld game consoles, and tablets, the most suitable estimator of online game time (estimand) in the surveillance programme since these are the main devices used for online gaming in China [ 23 ]. Secondary outcomes were: (1) total screen-viewing time, (2) internet-use time, (3) likelihood of meeting international screen-viewing time recommendations, and (4) likelihood of meeting the regulation on homework time (Table 1 ).

We calculated total sedentary behaviour time as the sum of total screen-viewing time (secondary outcome), homework time, and out-of-campus learning time (Table 1 ). Total screen-viewing time represents the sum of electronic device use time per day, TV/video game use time per day, and computer use time per day (Table 1 ). Total screen-viewing time was considered as an alternative estimator of online game time (estimand) since TV/videogame console use time and computer time could also capture the small proportion of children who use these devices for online gaming (Table 1 ). The international screen-viewing time recommendations were based on the American Academy of Paediatrics guidelines [ 21 ]. We did not include internet use time (secondary outcome) in total screen-viewing time, and total sedentary behaviour time, because this measure likely overlaps with other variables.

We defined subgroups by demographic characteristics, including the child’s sex (at birth: girls or boys), date of birth, education stage [primary school or secondary school [including middle school, high school, and ‘occupational schools’]), children’s residency (urban versus rural) and children’s baseline weight status (non-overweight versus overweight/obesity). Each sampling site selected for the survey was classified by the surveillance personnel as urban/rural and as lower-, medium-, or higher-economic level based on the area’s gross domestic product (GDP) per capita. The area’s GDP per capita was measured by the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Trained personnel also measured height, and weight using calibrated stadiometers and scales. Children’s weight/height were measured with light clothing and no shoes. Measurements during both waves were undertaken when students lived a normal life (no lockdowns, school were opened normally). We classified weight status (normal weight vs. overweight/obesity) according to the Chinese national reference charts [ 24 ].

Statistical analyses

We treated sedentary behaviour values that exceeded 24-hours per day as missing. We did not exclude extreme values for body mass index from the analyses 25 . Additional information, justifications, and results of implausible and missing values can be found in the Supplementary Table 1 , Additional File 1 .

The assumptions for normality and heteroscedasticity were assessed visually by inspecting residuals. We assessed multicollinearity via variance inflation factors. The outcome variables for linear regression outcomes were transformed using square roots to meet assumptions. We reported descriptive demographic characteristics (age, sex, area of residence, socioeconomic status), weight status, and outcome variables using means (or medians for non-normally distributed data) and proportions [ 26 ]

We ran multilevel models with random effects nested at the school and child levels to compare the outcomes in Wave 1 against Wave 2. We developed separate models for each sedentary behaviour outcome variable. We treated the introduction of the nationwide regulation as the independent binary variable (0 for Wave 1 and 1 for Wave 2). We ran linear models for continuous outcomes, logistic models for binary outcomes, and ordered logistic models for ordinal outcomes in a complete case analysis estimating population average treatment effects [ 27 ]. For the main analysis, in which participants had measurements in both Waves (longitudinal sample), only those with non-missing data at both time points were included.

We estimated marginal effects for each sedentary behaviour outcome. With a self-developed directed acyclic graph (DAG) we identified age (continuous), sex (male/female), area of residence (urban/rural), and socioeconomic status (high/medium/low) as confounders (see Supplementary Figs. 2–4, Additional File 1 ).

We evaluated subgroup effects defined by child’s sex at birth (boys versus girls), child’s stage of education (primary school versus secondary school [including middle school, high school, and ‘occupational schools’]), children’s residency (rural versus urban), and children’s baseline weight status (non-overweight versus overweight/obesity). We also repeated the covariate-adjusted model with interaction terms (between Wave and sex; Wave and child stage of education; Wave and residency; and Wave and weight status). We adjusted for multiple testing using Bonferroni correction ( p 0.05 divided by the number of performed tests for an outcome). The resulting cut-off point of p < 0.005 was used to determine the presence of any interaction effects.

We also conducted exploratory analyses (including subgroup analyses) by evaluating the same models with a representative, cross-sectional sample of 99,947 pupils. This cross-sectional sample included different schools and children at Wave 1 and Wave 2. We therefore used propensity score (PS) weighting to account for sample imbalances in the socio-demographic characteristics. Propensity scores were calculated by conducting a logistic regression, which calculated the likelihood of each individual to be in Wave 2 (dependent variable). Individual’s age, sex, area of residence and the GDP per area were treated as independent variables. Subsequently, inverse probability of treatment weighting was applied to balance the demographic characteristics in the sample in Wave 1 (unexposed to the regulatory intervention) and Wave 2 (exposed to the regulatory intervention). The sample weight for individuals in Wave 1 were calculated using the Eq. 1/ (1-propensity score). The sample weight for individuals in Wave 2 were calculated using the Eq. 1/propensity score [ 28 ].

We only ran linear models for continuous outcomes since it was not possible to run PS-weighted multilevel models with this sample size in Stata. We conducted all statistical analyses in Stata version 16.0.

Participant sample

In our primary, longitudinal analyses, we analysed data from 7,054 children and adolescents. The mean age was 12.3 years (SD, 2.4) and 3,477 (49.3%) were girls (Table 2 ). More detailed information on characteristics of subgroups in the longitudinal sample are presented in the Supplementary Tables 2–5, Additional File 2 .

Primary outcomes

Children and adolescents reported a reduction in their daily mean total sedentary behaviour time by 13.8% (95% CI: -15.9 to -11.7), or 46 min, on average between Waves 1 and 2. Participants were also less likely to report having increased their time spent on homework (adjusted odd ratio/AOR: 0.39; 95% CI: 0.35–0.43) and in out-of-campus learning (AOR: 0.53; 95% CI: 0.47 to 0.59) in Wave 2 in comparison to Wave 1, respectively (Tables 3 and 4 ). We did not find any changes in electronic device use time.

Secondary outcomes

Participants reported reducing their mean daily screen-viewing time by 6.4% (95% CI: -9.6 to -3.3%), or 10 min, on average (Tables 3 and 4 ). Participants were also 20% as likely to meet international screen time recommendations (AOR: 1.20; 95% CI: 1.09 to 1.32) and were 2.79 times as likely to meet the regulatory requirement on homework time (95% CI: 2.47 to 3.14) compared to the reference group (before the introduction of the regulation).

Subgroup analyses

Most screen- and study-related sedentary behaviour outcomes differed by education stage ( p < 0.005) (see Supplementary Tables 6–13, Additional File 2 ), with the reductions being larger in secondary school pupils than in primary school pupils (Tables 3 and 4 , and Table 5 ). Only secondary school pupils reduced their total screen-viewing time (-8.4%; 95% CI: -12.4 to -4.3) and were also 1.41 times as likely to meet screen-viewing recommendations (AOR: 1.41; 95% CI: 1.23 to 1.61) at Wave 2 compared to Wave 1.

Conversely, at Wave 2, primary school pupils reported a lower likelihood of spending more time doing homework (AOR: 0.30; 95%: 0.26 to 0.34) than secondary school pupils (AOR: 0.58; 95% CI: 0.50 to 0.67) compared to their counterparts at Wave 1. At Wave 2, primary school pupils also had a higher likelihood of reporting meeting homework time recommendations (AOR: 3.61; 95% CI: 3.09 to 4.22) than secondary school pupils (middle- and high school) (AOR: 2.11; 95% CI: 1.74 to 2.56) compared to their counterparts at Wave 1 (Table 5 ). There was also a residence interaction effect ( p < 0.001) in total sedentary behaviour time, with participants in urban areas reporting larger reductions (-15.3%; 95% CI: -17.8 to -12.7) than those in rural areas (-11.2%; 95% CI: -15.0 to -7.4). There was no evidence of modifying effects by children’s sex or baseline weight status (Tables 4 and 5 ).

Findings from the exploratory repeated cross-sectional analyses were similar to the findings of the main longitudinal analyses including total sedentary behaviour time, electronic device use time, total screen-viewing time and internet use time (see Supplementary Tables 14–23, Additional File 2 ).

Principal findings

Our study evaluated the impact of the world’s first regulatory, multi-setting intervention on multiple types of sedentary behaviour among school-aged children and adolescents in China. We found that children and adolescents reduced their total sedentary behaviour time, screen-viewing time, homework time and out-of-campus learning time following its implementation. The positive intervention effects on total screen-viewing time (-8.4 vs. -2.3%), and the likelihood of meeting recommendations on screen-viewing time (1.41 vs. 1.02 AOR) were more pronounced in secondary school pupils compared with primary school pupils. Intervention effects on total sedentary behaviour time (-15.3 vs. -11.2%) were more pronounced among pupils living in the urban area (compared to pupils living in the rural area). These subgroup differences imply that the regulatory intervention benefit more the groups known to have a higher rate of sedentary behaviour [ 29 ].

Interestingly, the observed reduction in electronic device use itself did not reach statistical significance following implementation of regulation. This could be viewed as a positive outcome if this is correctly inferred and not the result of reporting bias or measurement error. International data indicated that average sedentary and total screen time have increased among children due to the COVID-19 pandemic [ 12 ]. However, such interesting finding might be explained by the absence of lockdowns in Guangxi during both surveillance waves when most school-aged students outside China were affected by pandemic mitigation measures such as online learning.

Strengths and weaknesses

Our study has several notable strengths. This is the first study to evaluate the impact of multi-setting nationwide regulations on multiple types of sedentary behaviour in a large and regionally representative sample of children and adolescents. Still, to gain a more comprehensive view of the regulatory intervention on sedentary behaviour across China, similar evaluation research should be conducted in other regions of China. Furthermore, access to a rich longitudinal dataset allowed for more robust claims of causality. The available data also allowed us to measure the effect of the intervention on multiple sedentary behaviours including recreational screen-time and academic-related behaviours. Lastly, the large data set allowed us to explore whether the effect of the regulatory intervention varied across important subgroups, suggesting areas for further research and development.

Some limitations need to be taken into consideration when interpreting our findings. First, a common limitation in non-controlled/non-randomised intervention studies is residual confounding. We aimed to limit this by adjusting our analysis for confounders known to impact the variables of interest, but it is impossible to know whether important confounding may still have been present. With maturation bias, it is possible that secular trends are the cause for any observed effects. However, this seems unlikely in our study as older children may spend more time doing homework [ 23 ] and engage more in screen-viewing activities [ 30 ]. In this study, we observed reductions in these outcomes. The use of self-reported outcomes (social desirability bias) was a limitation and might have led to the intervention effects being over-estimated [ 13 ]. However, since our data were collected as part of a routine surveillance programme, pupils were unaware of the evaluation. This might mitigate reporting bias. In addition, the data were collected in Guangxi which might not representative of the whole population in China. Another limitation is using electronic device use time as a proxy measure of online gaming time. It is possible that electronic devices can be used for other purposes. However, mobile phones, handheld game consoles and tablets are the main devices used for online gaming. In this study, electronic device use time provided a practical means of assessing the broad effects of regulatory measures on screen time behaviours, including online gaming, in a large (province level) surveillance programme. In the future, instruments specifically designed to capture online gaming behaviour should be used in surveillance and research work.

Comparisons with other studies

Neither China nor other countries globally have previously implemented and evaluated multi-setting regulatory interventions on multiple types of sedentary behaviour, which makes comparative discussions challenging. In general, results of health behaviour research over the past decades have shown that interventions that address structural and environmental determinants of multiple behaviours to be more effective in comparison with individual-focussed interventions [ 31 ]. Furthermore, the continuous and universal elements of regulatory interventions may be particularly important explanations for the observed reductions in sedentary behaviour. Standalone school and other institution-led interventions may struggle with financial and logistic costs which threaten long-term implementation [ 13 ]. In contrast, the universality element of regulatory intervention can reduce or remove peer pressures and potential stigmatisation among children and teachers that are often associated with more selective/targeted interventions [ 24 ]. Our findings support WHO guidelines for physical activity and sedentary behaviour that encourage sustainable and scalable approaches for limiting sedentary behaviour and call for more system-wide policies to improve this global challenge[ 8 ].

Implications for future policy and research

Our study has important implications for future research and practice both nationally and internationally. Within China, future research should focus on optimising the implementation of the regulatory intervention through implementation research and assess long-term effects of the regulation on both behavioral and health outcomes. Internationally, our findings also provide a promising policy avenue for other countries and communities outside of China to explore the opportunities and barriers to implement such programmes on sedentary behaviour. This exploratory process could start with assessing how key stakeholders (including school-aged children, parents/carers, schoolteachers, health professionals, and policy makers) within different country contexts perceive regulatory actions as an intervention approach for improving health and wellbeing in young people, and how they can be tailored to fit their own contexts. Within public health domains, including healthy eating promotion, tobacco and alcohol control, regulatory intervention approaches (e.g., smoking bans and sugar taxation) have been adopted. However, regulatory actions for sedentary behaviour are scarce [ 19 ]. Within the education sector, some countries recently banned mobile phone use in schools for academic purpose [ 25 ]. While this implies potential feasibility and desirability of such interventions internationally, there is little research on the demand for, and acceptability of, multi-faceted sedentary behaviour regulatory interventions for the purpose of improving health and wellbeing. It will be particularly important to identify and understand any differences in perceptions and feasibility both within (e.g., public versus policy makers) and across countries of differing socio-cultural-political environments.

This natural experiment evaluation indicates that a multi-setting, regulatory intervention on sedentary behaviour has been effective in reducing total sedentary behaviour, and multiple types of sedentary behaviour among Chinese school-aged children and adolescents. Contextually appropriate, regulatory interventions on sedentary behaviour could be explored and considered by researchers and policy makers in other countries.

Data availability

Access to anonymised data used in this study can be requested through the corresponding author BL, subject to approval by the Guangxi CDC. WZ and SVP have full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Abbreviations

Centre for disease control and prevention

Directed acyclic graph

Gross domestic product

Metabolic equivalents

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Bao R, Chen S-T, Wang Y, Xu J, Wang L, Zou L, Cai Y. Sedentary Behavior Research in the Chinese Population: a systematic scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17(10).

Nguyen P, Le LK-D, Ananthapavan J, Gao L, Dunstan DW, Moodie M. Economics of sedentary behaviour: a systematic review of cost of illness, cost-effectiveness, and return on investment studies. Prev Med. 2022;156:106964.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. In. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

Zhang J, Yang SX, Wang L, Han LH, Wu XY. The influence of sedentary behaviour on mental health among children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Affect Disord. 2022;306:90–114.

Madigan S, Browne D, Racine N, Mori C, Tough S. Association between Screen Time and children’s performance on a Developmental Screening Test. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(3):244–50.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Pagani LS, Fitzpatrick C, Barnett TA, Dubow E. Prospective Associations between Early Childhood Television Exposure and academic, psychosocial, and Physical Well-being by Middle Childhood. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(5):425–31.

Boberska M, Szczuka Z, Kruk M, Knoll N, Keller J, Hohl DH, Luszczynska A. Sedentary behaviours and health-related quality of life. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev. 2018;12(2):195–210.

Fiona CB, Salih SA-A, Stuart B, Katja B, Matthew PB, Greet C, Catherine C, Jean-Philippe C, Sebastien C, Roger C et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2020, 54(24):1451.

China Sleep Research Association. Sleep White Paper of Chine People’s Health. In. Beijing, China; 2022.

Chaput J-P, Gray CE, Poitras VJ, Carson V, Gruber R, Olds T, Weiss SK, Gorber SC, Kho ME, Sampson M, et al. Systematic review of the relationships between sleep duration and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41(6):S266–82. (Suppl. 3)).

OECD. Does Homework Perpetuate inequities in Education? OECD Publishing 2014(46):4.

Trott M, Driscoll R, Iraldo E, Pardhan S. Changes and correlates of screen time in adults and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2022, 48.

van Sluijs EMF, Ekelund U, Crochemore-Silva I, Guthold R, Ha A, Lubans D, Oyeyemi AL, Ding D, Katzmarzyk PT. Physical activity behaviours in adolescence: current evidence and opportunities for intervention. Lancet. 2021;398(10298):429–42.

Cassar S, Salmon J, Timperio A, Naylor P-J, van Nassau F, Contardo Ayala AM, Koorts H. Adoption, implementation and sustainability of school-based physical activity and sedentary behaviour interventions in real-world settings: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity. 2019;16(1):120.

Article Google Scholar

Martins J, Costa J, Sarmento H, Marques A, Farias C, Onofre M, Valeiro MG. Adolescents’ perspectives on the barriers and facilitators of physical activity: an updated systematic review of qualitative studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18(9).

Gelius P, Messing S, Tcymbal A, Whiting S, Breda J, Abu-Omar K. Policy Instruments for Health Promotion: a comparison of WHO Policy Guidance for Tobacco, Alcohol, Nutrition and Physical Activity. Int J Health Policy Manage. 2022;11(9):1863–73.

Google Scholar

The General Office of the CPC Central Committee and the General Office of the State. Council issued the opinions on further reducing the Burden of Homework and off-campus training for students in the stage of Compulsory Education. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-07/24/content_5627132.htm .

Notice of the State Press and Publication Administration on Further Strict. Management to Effectively Prevent Minors from Being Addicted to Online Games. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2021-09/01/content_5634661.htm .

Craig P, Cooper C, Gunnell D, Haw S, Lawson K, Macintyre S, Ogilvie D, Petticrew M, Reeves B, Sutton M, et al. Using natural experiments to evaluate population health interventions: new Medical Research Council guidance. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2012;66(12):1182–6.

Craig P, Campbell M, Bauman A, Deidda M, Dundas R, Fitzgerald N, Green J, Katikireddi SV, Lewsey J, Ogilvie D, et al. Making better use of natural experimental evaluation in population health. BMJ. 2022;379:e070872.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Children, adolescents, and television. Pediatrics. 2001;107(2):423–6.

Bauer CP. Applied Causal Analysis (with R). In. Bookdown; 2020.

Matthay EC, Hagan E, Gottlieb LM, Tan ML, Vlahov D, Adler NE, Glymour MM. Alternative causal inference methods in population health research: evaluating tradeoffs and triangulating evidence. SSM - Popul Health. 2020;10:100526.

Greenberg MT, Abenavoli R. Universal interventions: fully exploring their impacts and potential to produce Population-Level impacts. J Res Educational Eff. 2017;10(1):40–67.

Selwyn N, Aagaard J. Banning mobile phones from classrooms—An opportunity to advance understandings of technology addiction, distraction and cyberbullying. Br J Edu Technol. 2021;52(1):8–19.

Boushey CJ, Harris J, Bruemmer B, Archer SL. Publishing nutrition research: A review of sampling, sample size, statistical analysis, and other key elements of manuscript preparation, Part 2. J Acad Nutr Dietet. 2008;108(4):679–688.

Matthay EC, Hagan E, Gottlieb LM, Tan ML, Vlahov D, Adler NE, Glymour MM. Alternative causal inference methds in population health research:Evaluating tradeoffs nd triangulating evidence. SSM - Population Health. 2020;10:100526.

Chesnaye NC, Stel VS, Tripepi G, Dekker FW, Fu EL, Zoccali C, Jager KJ. An introduction to inverse probability of treatment weighting in observation research. Clin Kid J. 2021;15(1):14–20.

Song C, Gong W, Ding C, Yuan F, Zhang Y, Feng G, Chen Z, Liu A. Physical activity and sedentary behaviour among Chinese children agd 6-17 years: a cross-sectional analysis of 2010-2012 China National Nutrition and Health Survey. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):936.

Zhu X, Haegele JA, Tang Y, Wu X. Physical activity and sedentary behaviors of urban chinese children: grade level prevalence and academic burden associations. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:7540147.

Rutter H, Bes-Rastrollo M, de Henauw S, Lathi-Koski M, Lehtinen-Jacks S, Mullerova D, Rasmussen F, Rissanen A, Visscher TLS, Lissner L. Balancing upstream and downstream measures to tackle the obesity epidemic: a position statement from the european association for the study of obesity. Obesity Facts. 2017;10(11):61–63.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Dr Peter Green and Dr Ruth Salway for providing feedback on the initial data analysis plan, and Dr Hugo Pedder and Lauren Scott who provided feedback on the statistical analyses.

This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust through the Global Public Health Research Strand, Elizabeth Blackwell Institute for Health Research. The funder of our study had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Exercise, Nutrition and Health Sciences, School for Policy Studies, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

Bai Li, Remco Peters & Charlie Foster

Public Health Wales, Cardiff, UK

Selene Valerino-Perea

Department of Nutrition and School Health, Guangxi Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Nanning, Guangxi, China

Weiwen Zhou

School of Public Health, Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, Guangxi, China

Yihong Xie, Zouyan He & Yunfeng Zou

Centre for Health, Law, and Society, School of Law, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

Keith Syrett

Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

Frank de Vocht

NIHR Applied Research Collaboration West (ARC West), Bristol, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

BL conceived the study idea and obtained the funding with support from WZ, CF, KS, YX, YZ, ZH and RP. BL, CF, FdV and KS designed the study. WZ led data collection and provided access to the data. YX, SVP and ZH cleaned the data. SVP analysed the data with guidance from BL, FdV and CF. BL, SVP and RP drafted the paper which was revised by other authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Bai Li .

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate.

Ethics approvals were granted by the School for Policy Studies Research Ethics Committee at the University of Bristol (reference number SPSREC/20–21/168) and the Research Ethics Committee at Guangxi Medical University (reference number 0136). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant, and a parent or guardian for participants aged < 20 years.

Consent for publication

The co-authors gave consent for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Supplementary material 2, supplementary material 3, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Li, B., Valerino-Perea, S., Zhou, W. et al. The impact of the world’s first regulatory, multi-setting intervention on sedentary behaviour among children and adolescents (ENERGISE): a natural experiment evaluation. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 21 , 53 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-024-01591-w

Download citation

Received : 20 December 2023

Accepted : 04 April 2024

Published : 13 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-024-01591-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Sedentary behaviour

- Physical activity

- Regulatory intervention

- Health policy

- Screen time

- Natural experiment

- Mental health

- Health promotion

- Child health

International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity

ISSN: 1479-5868

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Who is Andrei Belousov, Putin's choice as defence minister?

- Medium Text

Sign up here.

Reporting by Reuters; editing by Guy Faulconbridge and Chris Reese

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. New Tab , opens new tab

World Chevron

North Korean leader oversees tactical missile weapons system, KCNA says

North Korean leader Kim Jong Un on Tuesday oversaw a tactical missile weapons system that will be newly installed at missile units of its army, state media KCNA reported on Wednesday.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Secondary school. Chelmsford County High School for Girls in Essex has a school-wide homework policy setting out: The importance of homework; Types of homework that could be set; How much time different year groups should spend on homework; Special school. North Ridge High School in Manchester has a homework policy that explains:

Homework is defined as the time students spend outside the classroom in assigned learning activities. Anywhere Schools believes the purpose of homework should be to practice, reinforce, or apply acquired skills and knowledge. We also believe as research supports that moderate assignments completed and done well are more effective than lengthy ...

students is a requirement of an effective school Homework Policy. In developing a policy, the school community needs to determine what communication approaches and processes will be most effective for parents/caregivers, students and teachers. The school's Homework Policy should be made available to the school community, particularly at the

St Andrew's Secondary School Homework Policy In St Andrew's Secondary School, we believe in the value of homework, that it can reinforce students' learning, provide feedback on their progress and cultivate a healthy disposition towards continual learning, when used appropriately. Since excessive homework can have an

A good homework policy creates transparency for parents. It helps them to understand the value the school places on homework and what the learning objectives are. If parents understand this, it will help set a foundation for them to be engaged in their child's education. #4 Gives students a routine and creates good habits.

Good homework policies avoid excessive time requirements - focusing on quality rather than quantity and making sure that there is a clear purpose to any homework set. ... At secondary school, if a pupil doesn't complete their homework, they risk falling behind. They may also hold up others - clearly it is harder for the teacher to keep ...

I. Philosophy. The purposes of homework are to improve the learning processes, to aid in the mastery of skills, and to create and stimulate interest on the part of the student. Homework is a shared responsibility among the teacher, student and family. The term "homework" refers to an assignment to be prepared during a period of supervised study ...

Go Deeper In "The Homework Debate: What It Means for Lower Schools," a July 22, 2019 Independent Ideas blog post, author Kelly King asks, "Does homework prepare students for middle school and beyond?" and shares how her school sought to answer that question. "To create a better policy that centers on student needs, faculty members and I decided to investigate the value of homework.

When implementing homework, the evidence suggests a wide variation in impact. Therefore, schools should consider the ' active' ingredients to the approach, which may include: Considering the quality of homework over the quantity. Using well-designed tasks that are linked to classroom learning. Clearly setting out the aims of homework to pupils.

Homework Policies for School Districts, Schools, and Classrooms. Show details Hide details. Harris Cooper. ... Effective Grading Practices for Secondary Teachers. 2015. SAGE Knowledge. Entry . Homework. Show details Hide details. Gale M. Morrison and more... Encyclopedia of School Psychology. 2005. View more.

6.9 Subject Leaders must ensure that homework is set and marked regularly, by all members of their department, in accordance with school and departmental policy. 6.10 It is the responsibility of the teaching and learning lead to ensure that an evaluation and review of school homework policy and procedures is undertaken. The

In general, homework across disciplines should not exceed 0.5 hour in kindergarten through grade three, 1 hour in grades four through six, 1.5 hours at the middle school level, and 2 hours at the high school level. To ensure that student homework falls within FCPS regulations, middle school teachers should plan for homework not to exceed 25 ...

Secondary school students should be capable of managing their workload, researching independently, and applying critical thinking skills to their assignments. Homework Policy for High School: 1. Advanced Academic Rigor: High school homework involves advanced academic rigor, often requiring critical analysis, research, and synthesis of information.

There is an underlying and ongoing issue with motivation to complete homework in my setting despite the implementation of a whole-school homework policy covering key stage 3 and 4 years of study.

The school will take responsibility for informing parents/carers and pupils of the whole school homework policy in Kings Park Secondary School. The school will inform parents/carers of: o The aims of the homework policy o The use of the pupil planner o How best they can support their childs study The Role of Staff

of the whole school policy through the use of the school website and an information booklet. The Principal will ensure that the whole school policy is embedded firmly in departmental provision and that provision is regularly monitored and reviewed. Class Teachers will issue, monitor and assess regularly, homework undertaken by pupils. It is ...

The aim of homework is to: consolidate and extend work covered in class. prepare students for new learning activities. review previous learning. develop research skills and interests. provide an opportunity for independent work and practice. enhance study skills e.g. planning, time management and self-discipline.

Homework Policy. BP 6154 Homework/Makeup Work. AR 6154 Homework/Makeup Work. Homework Policy - Palo Alto Unified School District.

The Homework and Study policy is a guide for students, teachers and parents on how to improve classroom learning and fulfil students' true potential. It is intended to foster self-discipline, independent learning and encourage students to take responsibility for their own learning. Learning is a lifelong skill and many strategies can be ...