Disability is not an obstacle to success. These inspirational leaders prove that

These leaders show that disability is no barrier to achieving incredible things Image: REUTERS/Murad Sezer

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Stéphanie Thomson

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved .chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

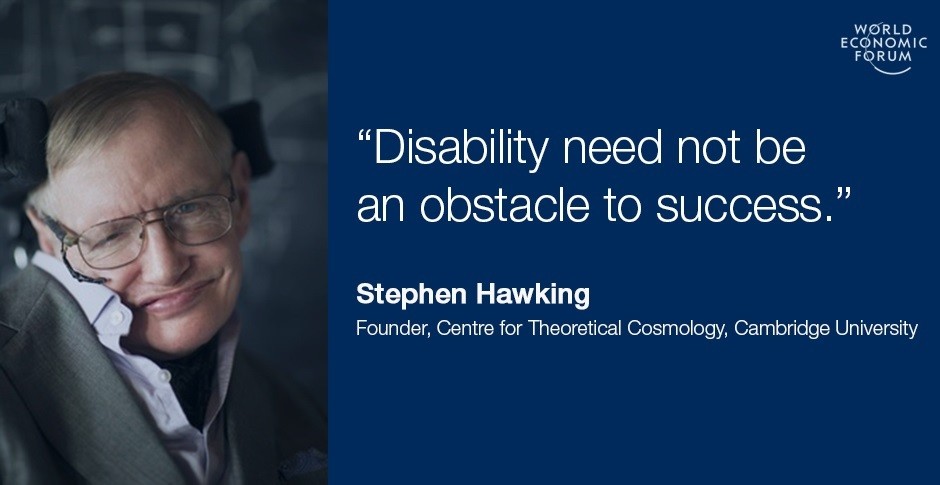

“Disability need not be an obstacle to success,” Stephen Hawking wrote in the first ever world disability report back in 2011. As one of the most influential scientists of modern times, the wheelchair-bound physicist is certainly proof of that.

So why then are public attitudes so far from the reality? Almost 40% of respondents in a survey in Britain said that disabled people aren’t as productive as others. In the same survey, a quarter of disabled people said people expected less of them because of their disability.

It is these sorts of attitudes, rather than any mental or physical impairment, that create barriers for people with disabilities. As these leaders from the world of sports, culture and business show, it’s about time we changed those outdated beliefs.

“I went blind at 22. From an athlete, I became a young man with a white cane, unsure how to live my life,” Mark Pollock, a Forum Young Global Leader explains. But very soon, he found a deeper purpose in life, and realized his disability didn’t have to stop him from achieving great things.

“I began to race in deserts, mountains, across oceans, and on the 10th anniversary of going blind, I raced over 43 days to the South Pole.”

But in 2010, an accident left him paralyzed, and once again his world changed overnight: “My new life was shattered.”

He had a choice: to let his disability define him for the rest of his life, or to continue fighting. There was only ever one way it was going to go.

“If I just sat in a wheelchair, I’d be giving up completely,” he remembers. Today, he’s working with other leaders from science, technology and communications to fund and fast-track a cure for paralysis.

Born in the US in 1880, an illness left Helen Keller both blind and deaf before her second birthday. While the services available to people with disabilities were less extensive than they are today, Keller’s mother sought out experts and ensured her daughter received the best education.

In 1904, Keller graduated from Radcliffe College, becoming the first deaf-blind person to earn a bachelor of arts. It was at university that her career as a writer and social activist started. Today, the Helen Keller archives contain almost 500 speeches and essays on topics as varied as birth control and Fascism in Europe.

She would go on to achieve international acclaim, becoming America’s first Goodwill Ambassador, and to this day she remains an inspiration to the deaf and blind .

Ralph Braun was still a young boy when he was diagnosed with muscular dystrophy, an incurable group of genetic diseases that leads to a loss of muscle mass.

A few years after his diagnosis, Ralph began to lose his ability to walk. While doctors warned him he would never be able to lead an independent life, the young boy was already proving people wrong, building the first battery-powered scooter. His passion would eventually lead him to establish wheelchair manufacturer BraunAbility.

He died in 2013, but as his company’s website notes, his legacy lives on. “Necessity is the mother of invention, and Ralph’s physical limitations only served to fuel his determination to live independently and prove to society that people with physical disabilities can participate fully and actively in life.”

Mexico’s most famous artist was born with spina bifida, a condition that can cause defects in the spinal cord. At six, she contracted polio, which left one leg much thinner than the other.

In spite of these challenges, she was an active child, but at 18 a bus accident left her with serious injuries. It was while recovering from the accident that Frida discovered her love of painting. She would go on to be one of the most famous Surrealists in the world.

Have you read?

A tipping point missed: women in global leadership, want to improve your decision-making and become a better leader some mistakes to avoid, don't miss any update on this topic.

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Leadership .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

From Athens to Dhaka: how chief heat officers are battling the heat

Angeli Mehta

May 8, 2024

This is what businesses need to be focusing on in 2024, according to top leaders

Victoria Masterson

April 16, 2024

3 ways leaders can activate responsible leadership in uncertain times

Ida Jeng Christensen

April 8, 2024

The catalysing collective: Announcing the Class of 2024

April 4, 2024

What we learned about effective decision making from Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman

Kate Whiting

March 28, 2024

Women founders and venture capital – some 2023 snapshots

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Book Reviews

In 2 essay collections, writers with disabilities tell their own stories.

Ilana Masad

Buy Featured Book

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

- Independent Bookstores

More than 1 in 5 people living in the U.S. has a disability, making it the largest minority group in the country.

Despite the civil rights law that makes it illegal to discriminate against a person based on disability status — Americans with Disabilities Act passed in 1990 — only 40 percent of disabled adults in what the Brookings Institute calls "prime working age," that is 25-54, are employed. That percentage is almost doubled for non-disabled adults of the same age. But even beyond the workforce — which tends to be the prime category according to which we define useful citizenship in the U.S. — the fact is that people with disabilities (or who are disabled — the language is, for some, interchangeable, while others have strong rhetorical and political preferences), experience a whole host of societal stigmas that range from pity to disbelief to mockery to infantilization to fetishization to forced sterilization and more.

But disabled people have always existed, and in two recent essay anthologies, writers with disabilities prove that it is the reactions, attitudes, and systems of our society which are harmful, far more than anything their own bodies throw at them.

About Us: Essays from the Disability Series of the New York Times, edited by Peter Catapano and Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, collects around 60 essays from the column, which began in 2016, and divides them into eight self-explanatory sections: Justice, Belonging, Working, Navigating, Coping, Love, Family, and Joy. The title, which comes from the 1990s disability rights activist slogan "Nothing about us without us," explains the book's purpose: to give those with disabilities the platform and space to write about their own experiences rather than be written about.

While uniformly brief, the essays vary widely in terms of tone and topic. Some pieces examine particular historical horrors in which disability was equated with inhumanity, like the "The Nazis' First Victims Were the Disabled" by Kenny Fries (the title says it all) or "Where All Bodies Are Exquisite" by Riva Lehrer, in which Lehrer, who was born with spina bifida in 1958, "just as surgeons found a way to close the spina bifida lesion," visits the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia. There, she writes:

"I am confronted with a large case full of specimen jars. Each jar contains a late-term fetus, and all of the fetuses have the same disability: Their spinal column failed to fuse all the way around their spinal cord, leaving holes (called lesions) in their spine. [...] I stand in front of these tiny humans and try not to pass out. I have never seen what I looked like on the day I was born."

Later, she adds, "I could easily have ended up as a teaching specimen in a jar. But luck gave me a surgeon."

Other essays express the joys to be found in experiences unfamiliar to non-disabled people, such as the pair of essays by Molly McCully Brown and Susannah Nevison in which the two writers and friends describe the comfort and intimacy between them because of shared — if different — experiences; Brown writes at the end of her piece:

"We're talking about our bodies, and then not about our bodies, about her dog, and my classes, and the zip line we'd like to string between us [... a]nd then we're talking about our bodies again, that sense of being both separate and not separate from the skin we're in. And it hits me all at once that none of this is in translation, none of this is explaining. "

From the cover of Resistance and Hope: Essays by Disabled People, edited by Alice Wong Disability Visibility Project hide caption

From the cover of Resistance and Hope: Essays by Disabled People, edited by Alice Wong

While there's something of value in each of these essays, partially because they don't toe to a single party line but rather explore the nuances of various disabilities, there's an unfortunate dearth of writers with intellectual disabilities in this collection. I also noticed that certain sections focused more on people who've acquired a disability during their lifetime and thus went through a process of mourning, coming to terms with, or overcoming their new conditions. While it's true — and emphasized more than once — that many of us, as we age, will become disabled, the process of normalization must begin far earlier if we're to become a society that doesn't discriminate against or segregate people with disabilities.

One of the contributors to About Us, disability activist and writer Alice Wong, edited and published another anthology just last year, Resistance and Hope: Essays by Disabled People , through the Disability Visibility Project which publishes and supports disability media and is partnered with StoryCorps. The e-book, which is available in various accessible formats, features 17 physically and/or intellectually disabled writers considering the ways in which resistance and hope intersect. And they do — and must, many of these writers argue — intersect, for without a hope for a better future, there would be no point to such resistance. Attorney and disability justice activist Shain M. Neumeir writes:

"Those us who've chosen a life of advocacy and activism aren't hiding from the world in a bubble as the alt-right and many others accuse us of doing. Anything but. Instead, we've chosen to go back into the fires that forged us, again and again, to pull the rest of us out, and to eventually put the fires out altogether."

You don't go back into a burning building unless you hope to find someone inside that is still alive.

The anthology covers a range of topics: There are clear and necessary explainers — like disability justice advocate and organizer Lydia X. Z. Brown's "Rebel — Don't Be Palatable: Resisting Co-optation and Fighting for the World We Want" — about what disability justice means, how we work towards it, and where such movements must resist both the pressures of systemic attacks (such as the threatened cuts to coverage expanded by the Affordable Care Act) and internal gatekeeping and horizontal oppression (such as a community member being silenced due to an unpopular or uninformed opinion). There are essays that involve the work of teaching towards a better future, such as community lawyer Talila A. Lewis's "the birth of resistance: courageous dreams, powerful nobodies & revolutionary madness" which opens with a creative classroom writing prompt: "The year is 2050. There are no prisons. What does justice look like?" And there are, too, personal meditations on what resistance looks like for people who don't always have the mobility or ability to march in the streets or confront their lawmakers in person, as Ojibwe writer Mari Kurisato explains:

"My resistance comes from who I am as a Native and as an LGBTQIA woman. Instinctively, the first step is reaching out and making connections across social media and MMO [massively multiplayer online] games, the only places where my social anxiety lets me interact with people on any meaningful level."

The authors of these essays mostly have a clear activist bent, and are working, lauded, active people; they are gracious, vivid parts of society. Editor Alice Wong demonstrates her own commitments in the diversity of these writers' lived experiences: they are people of color and Native folk, they encompass the LGBTQIA+ spectrum, they come from different class backgrounds, and their disabilities range widely. They are also incredibly hopeful: Their commitment to disability justice comes despite many being multiply marginalized. Artist and poet Noemi Martinez, who is queer, chronically ill, and a first generation American, writes that "Not all communities are behind me and my varied identities, but I defend, fight, and work for the rights of the members of all my communities." It cannot be easy to fight for those who oppress parts of you, and yet this is part of Martinez's commitment.

While people with disabilities have long been subjected to serve as "inspirations" for the non-disabled, this anthology's purpose is not to succumb to this gaze, even though its authors' drive, creativity, and true commitment to justice and reform is apparent. Instead, these essays are meant to spur disabled and non-disabled people alike into action, to remind us that even if we can't see the end result, it is the fight for equality and better conditions for us all that is worth it. As activist and MFA student Aleksei Valentin writes:

"Inspiration doesn't come first. Even hope doesn't come first. Action comes first. As we act, as we speak, as we resist, we find our inspiration, our hope, that which helps us inspire others and keep moving forward, no matter the setbacks and no matter the defeats."

Ilana Masad is an Israeli American fiction writer, critic and founder/host of the podcast The Other Stories . Her debut novel, All My Mother's Lovers, is forthcoming from Dutton in 2020.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

‘Nothing About Us Without Us’: 16 Moments in the Fight for Disability Rights

The disability civil rights movement has many distinct narratives, but the prevailing themes are of community, justice and equity.

By Julia Carmel

Listen to This Article

As with every other civil rights movement, the fight for disability rights is one that challenges negative attitudes and pushes back against oppression. But it is also more complex.

Often the movement has diverged into a constellation of single-issue groups that raise awareness of specific disabilities. It has also converged into cross-disability coalitions that increasingly include intersections of race, gender and sexual orientation.

Regardless, the prevailing demands of the movement are the same: justice, equal opportunities and reasonable accommodations.

Though it is difficult to distill modern disability history in one thread, here are a handful of moments that have stood out in the collective memories of disability advocates.

A Growing Spirit of Independence

The earliest disability law in the United States dates from pensions guaranteed for men wounded in the Revolutionary War.

“You tend to have a grateful nation that wants to figure out how to help them reincorporate themselves to society,” said Heather Ansley, the associate executive director of government relations for Paralyzed Veterans of America.

By the 1940s, rubella and polio were on the rise, further raising awareness of disabilities.

Summer camps and rehabilitation centers were established to provide nurturing environments. In the 1960s and ’70s, friendships were cultivated among a generation of people who would go on to become some of the foremost activists of the modern civil rights movement.

Ed Roberts was among those top activists. He was the first student who used a wheelchair to attend the University of California, Berkeley. Because there were no accessible dormitories, he lived in Cowell, the campus hospital. He inspired the blueprint for the first Center for Independent Living. There are now 403 C.I.L.s that are run by and for people with disabilities who live independently of nursing homes and other institutions.

The Rise of Representation

Portrayals of disabilities in the mainstream media have often been negative, said Adela Ruiz, a sociology professor at Monroe College. Take villain archetypes: Captain Hook was an amputee, Maleficent used a staff and the main character in the film “Joker” (2019) is depicted as a “ mentally ill loner .”

But there was also Ray Charles, who “played a big part of my growing up,” said Leroy Moore Jr.

Mr. Moore noticed a lot of Black disabled musicians — Stevie Wonder, B.B. King, Robert Winters and many more — on album covers as he rummaged through his father’s record collection. Today, he pushes for the representation of disabled musicians as a founder of Krip-Hop Nation .

“Sesame Street” also shed a positive light on disabled people.

“Linda Bove — who’s a fabulous Deaf actor — was playing Linda, the librarian, but there are also other disabled folks and disability topics popping up in ‘Sesame Street’ across the 1970s,” said Susan Burch, a professor who teaches critical disability studies at Middlebury College in Vermont. “That was a big darn deal!”

Institutionalization and Mistreatment

In 1972, the conditions at the Willowbrook State School , an institution on Staten Island in New York City, set off national outrage when the journalist Geraldo Rivera shared harrowing footage in the documentary “Willowbrook: The Last Great Disgrace.”

“It was like a badly run kennel for humans,” Mr. Rivera said while giving a speech in April 2010. “It was something that shook me to my core.”

Institutionalization and false treatments had been in practice for decades, including at the Hiawatha Asylum for Insane Indians in Canton, S.D., which closed in 1933.

“It wasn’t like, ‘Oh, this is the place where we’re going to treat mental illness,’” said Jen Deerinwater, founding executive director of Crushing Colonialism and a citizen of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. “It was, ‘We’re going to round up a bunch of Natives and throw them in this asylum and just traumatize them.’”

A video that surfaced in 2012 showed the staff of the Judge Rotenberg Educational Center in Canton, Mass., using electric shock on Andre McCollins , an autistic resident, 31 times over seven hours because he would not remove his jacket.

“They started with other forms of what they call ‘aversive punishment,’ like slapping people, pinching them; tying them down for hours at a time, subjecting them to forcible inhalation of ammonia,” said Lydia X. Z. Brown, an autistic advocate and attorney who maintains an archive of the center’s abuses .

The Food and Drug Administration announced a ban on the center’s shock devices earlier this year, but it has not gone into effect, evidence that an era of deinstitutionalization is far from over.

Education Rights and Parent Advocacy

The Education for All Handicapped Children Act (now the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act), enacted in 1975, required federally funded public schools to provide equal access to education and one free meal a day to children with disabilities.

The law was passed after parents filed a number of lawsuits that referred to the landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling.

Legislators have also used the education law as a model for other disability laws.

“If you don’t have an education, we can’t get you to get a job; we can’t have you participate in society. If you don’t have transportation, you can’t get back and forth to your job,” said Pat Wright, a disability rights activist who co-founded the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund . “So each one of those things that nondisabled kids take for granted become the linchpin of people with disabilities’ lives.”

The 504 Sit-Ins

On April 5, 1977, demonstrators marched outside government buildings in San Francisco and several other cities across the nation. Their demand: Sign the regulations enforcing Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. This provision, which had been modeled after the Civil Rights Act of 1964, prohibited recipients of federal aid from discriminating against anyone with a disability. The federal Department of Health, Education and Welfare had been tasked with writing the regulations and implementing Section 504, but it still had not been enacted four years later.

The San Francisco contingent of more than 100 people entered H.E.W.’s offices and stayed for weeks.

“It was kind of like a crescendo,” said Judy Heumann, who led the demonstration. “Like, ‘if we leave, we’ll never get back in.’”

About two dozen of the demonstrators were chosen to make their case in Washington, where they found success — the regulations were signed on April 28, 1977. It’s now considered a precursor to the A.D.A.

The Gang of 19 and ADAPT

On July 5, 1978, a group of 19 people gathered at one of the busiest intersections in Denver, at Colfax Avenue and Broadway, got out of their wheelchairs and lay down to stop traffic. Their goal was to protest the inaccessibility of the city’s public transit system.

The group had been pushing the city to install wheelchair lifts, and when a new fleet of buses was released without them, they were angry. The protest ultimately led to the creation of the Americans Disabled for Accessible Public Transit (now the American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today ), in 1983, which quickly expanded with chapters all around the country. The group then pushed for transportation provisions to be added to the A.D.A.

‘Baby Doe’ and ‘Baby Jane Doe’

In 1982, the parents of a baby with Down syndrome in Bloomington, Ind., were advised by doctors to decline surgery to treat the baby’s blocked esophagus. Disability rights activists tried to intervene, but Baby Doe, as he came to be known, starved to death before legal action could be taken.

Dr. C. Everett Koop, the surgeon general of the United States at the time, said the boy was denied food and water not because the treatment was unreasonably risky, but because the baby was intellectually disabled, a decision he did not agree with.

In 1983, another case surfaced on Long Island that came to be known as Baby Jane Doe. The baby was born with an open spinal column; her parents opted against surgery, even though it could have prolonged her life.

The Reagan administration called for the creation of “Baby Doe squads” in which government officials, including child-protective service agents, went to hospitals to inspect reports of discrimination of newborns with illnesses.

“At a time of maximum stress for parents, the squads descended on hospitals and interfered with the roles of parents, physicians, infant care review committees, hospitals and state authorities,” James H. Sammons, the executive vice president of the American Medical Association, wrote in an op-ed for The Washington Post in 1985 .

The issues raised by both cases ultimately led to the 1984 passage of the Baby Doe Amendment to the Child Abuse Law, which established guidelines for treating newborns with illnesses.

‘Deaf President Now’

On March 6, 1988, Gallaudet University in Washington, a liberal arts college for Deaf people, appointed a president who was not Deaf.

The university had, in fact, never had a Deaf president. This set off a student protest that came to be known as Deaf President Now.

It was an important moment in Deaf civil rights history because it “in some ways, led to contestations over what it means to be deaf and questions of belonging within deaf spaces,” Dr. Octavian Robinson, a historian and disability studies scholar, wrote in an email.

After several days, the university named I. King Jordan its first Deaf president.

The Capitol Crawl

In the months before the A.D.A. was signed into law by President George H.W. Bush on July 26, 1990, it was stalled in Congress.

“All the i’s have been dotted and all the t’s have been crossed,” Rep. Major R. Owens , a primary backer of the A.D.A., said of the law at the time. “There have been enough negotiations — delay is the real enemy.”

On March 12, hundreds of demonstrators on the National Mall abandoned their wheelchairs and crutches and began crawling up the marble steps to the west Capitol entrance. The Capitol Crawl, as the event came to be known, underscored the injustices of inaccessibility that the A.D.A.’s “reasonable accommodations” clause was intended to fix.

Many of the protesters were arrested, including Anita Cameron, who said she had been arrested 139 times in her fight for disability rights.

“I think on that day and at that time, more people learned about disability discrimination and equal opportunity than we can imagine,” said Lex Frieden, a disability policy expert who helped shape the A.D.A.

‘Don’t Mourn for Us’: Jim Sinclair and the Neurodiversity Movement

In 1993, Jim Sinclair, one of the founders of Autism Network International , spoke at the International Conference on Autism in Toronto, focusing on a sentiment that was often expressed by parents of autistic children — a sense of “loss” upon learning their child wasn’t “normal.”

“You didn’t lose a child to autism,” said Jim , who prefers not to use gendered pronouns or honorifics. “You lost a child because the child you waited for never came into existence. That isn’t the fault of the autistic child who does exist, and it shouldn’t be our burden.”

“Grieve if you must, for your own lost dreams,” Jim added. “But don’t mourn for us . We are alive. We are real. And we’re here waiting for you.”

The speech became a foundation for what has become known as the neurodiversity movement, a belief that cognitive differences are part of normal variations of human behavior.

“Neurodiversity affirms that everyone deserves to be accepted and included for who they are,” Sharon daVanport, the founding executive director of the Autistic Women & Nonbinary Network , wrote in an email.

Not Dead Yet: Disability and Assisted Suicide

In the 1990s, debates surrounding assisted suicide and Dr. Jack Kevorkian’s campaign to assist terminally ill people to end their lives unfurled on the national stage.

The discourse led to the founding of the disability rights group Not Dead Yet .

Tucked into the polarizing conversation was an assumption that people “don’t want to be disabled, that they feel that being disabled is undignified,” said Ms. Cameron, the director of minority outreach for Not Dead Yet. “And as a person with disabilities, I totally resent that.”

Many advocates link assisted suicide to the eugenics movements of the 1800s — which pushed for “undesirable” traits to be bred out of the gene pool — and the Buck v. Bell decision, which allowed doctors to sterilize “mental defectives” without their consent because, as Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. famously wrote , “three generations of imbeciles are enough.” The ruling still stands.

“It comes back to that fundamental belief that some people are actually more valuable than other people,” Ms. Burch said, “and that’s core to how ableism functions.”

Olmstead v. L.C.

This Supreme Court ruling played a major role in categorizing mental illness as a disability under the A.D.A.

The case involved Lois Curtis and Elaine Wilson, two women with mental and intellectual disabilities who had been treated in Georgia hospitals but were held in institutions for years, caught in a bureaucratic limbo as they waited for placements in community-based facilities.

The case against Tommy Olmstead, who was the commissioner of the Georgia Department of Human Resources, was filed in 1995 and made its way up to the Supreme Court. In 1999, the court ruled that unjustified segregation of people with disabilities constituted discrimination that violated the A.D.A.

Disability Pride

Disability pride parades are now held in several cities around the nation, challenging society’s stigma of disability while celebrating disabilities as a form of diversity. The first such parade was held in 1990 in Massachusetts, but the events became more regular after Chicago held its first parade in 2004.

“My fibromyalgia-slow-cane-using body is not something I’m going to hate,” said Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, the author of “Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice.” “I’m not just this symbol of brokenness — I’m a place of power.”

But some who are still in the throes of advocacy have found pride to be a complicated term to embrace because there is more work to be done.

“Pride is tricky,” said Eli Clare, a writer and activist who was the Chicago parade’s grand marshal in 2010. “Pride often only comes to us after we have some community and after we have some politicized framework around who we are.”

The A.D.A. and the Internet

In 2006, the National Federation of the Blind filed a class-action suit against Target Corporation saying that the company’s website was not accessible.

“Is sexism OK online? Is racism OK online?” asked Haben Girma, a disability rights lawyer who works closely with technology and policy. “Most people would answer with an immediate no. I want our society to get to the point where if one asks, ‘Is ableism OK online?’ the answer is an immediate no.”

The court held that the A.D.A. applies to websites that have a connection to a physical place of public accommodation, and that Target must modify its website.

Amid the coronavirus pandemic, as social distancing and remote work have made the internet indispensable, tech accessibility has become even more critical.

“Schools, health agencies, and hospitals have been posting videos without captions,” Ms. Girma said. “Images with critical health information, figures and charts, lack image descriptions for blind people.”

Race, Disability and Police Brutality

About 30 to 50 percent of all people killed by law enforcement officers are disabled, according to a study by the Ruderman Family Foundation . As tensions heightened in 2014 alongside the rise of Black Lives Matter, this statistic became especially apparent.

Disability was overlooked in news reports of the deaths of Sandra Bland, Eric Garner, Freddie Gray and many others, said Cyrée Jarelle Johnson, a Black disabled poet and librarian. Instead the term “underlying conditions” was used to refer to depression, asthma and high blood pressure — “a euphemism that is bent to make people feel like they’re not murdering disabled people.”

Mx. Deerinwater, of Crushing Colonialism, pointed out an even more stark statistic.

“The C.D.C. actually says that Native people have the highest rates per capita of police brutality,” Mx. Deerinwater said. “I want to say that ‘per capita’ piece is always crucial when we talk about any issue related to Natives because we’re a little less than 2 percent of the U.S. population.”

Confrontations with the police present a real concern for people like Vilissa Thompson, a social worker and the founder of the blog Ramp Your Voice!

“I’m someone who’s hard of hearing and if I cannot hear a command that’s given to me by law enforcement, that can make me appear to be noncompliant,” she said.

Creating Space for Community

Throughout the disability rights movement, the merging of communities has been the driving force behind major changes.

Organizations like the Harriet Tubman Collective and Sins Invalid have created space for art and collective liberation.

“Disability justice is about political organizing and legal change and all of that,” Ms. Piepzna-Samarasinha said, “but it’s also about creating communities where we can be all of ourselves without shame, and with joy.”

In 2016, the #CripTheVote Twitter campaign was created by Alice Wong, the founder of the Disability Visibility Project ; Andrew Pulrang, a contributing writer for Forbes.com ; and Gregg Beratan, the director of advocacy at the Center for Disability Rights .

In the past four years, they have organized 64 Twitter chats or live-tweets of events, which are all archived .

“As with most branches of disability culture,” Mr. Pulrang said, “it also helps disabled people discover that they are not alone, and that their experiences are usually not unique or strange.”

People of color and L.G.B.T.Q. voices have asserted themselves in the movement, raising awareness with hashtags like #DisabilityTooWhite .

“To me, disability justice means that we’re taking into account people of color, and people that are marginalized within the disability community,” said Mr. Moore, the founder of Krip-Hop Nation, adding, “we’re taking these principles and really living by them, not only in organizations but in our own lives.”

Julia Carmel is a news assistant on the Obituaries desk who occasionally writes about culture, queer communities and New York City. More about Julia Carmel

About the Journal

Disability Studies Quarterly ( DSQ ) is the journal of the Society for Disability Studies (SDS). It is a multidisciplinary and international journal of interest to social scientists, scholars in the humanities and arts, disability rights advocates, and others concerned with the issues of people with disabilities. It represents the full range of methods, epistemologies, perspectives, and content that the field of disability studies embraces. DSQ is committed to developing theoretical and practical knowledge about disability and to promoting the full and equal participation of persons with disabilities in society. (ISSN: 1041-5718; eISSN: 2159-8371)

Make a Submission

Dsq social media.

Tweets by @DSQJournal

DSQ Instagram

Volume 1 through Volume 20, no. 3 of Disability Studies Quarterly is archived on the Knowledge Bank site ; Volume 20, no. 4 through the present can be found on this site under Archives .

Beginning with Volume 36, Issue No. 4 (2016), Disability Studies Quarterly is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives license unless otherwise indicated.

Disability Studies Quarterly is published by The Ohio State University Libraries in partnership with the Society for Disability Studies .

If you encounter problems with the site or have comments to offer, including any access difficulty due to incompatibility with adaptive technology, please contact [email protected] .

ISSN: 2159-8371 (Online); 1041-5718 (Print)

Essay on Disabled Person

Students are often asked to write an essay on Disabled Person in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Disabled Person

Understanding disability.

Disability refers to any condition that limits a person’s physical or mental abilities. These conditions can be present from birth or occur during a person’s lifetime. Disabilities can affect a person’s mobility, senses, or cognitive abilities.

Types of Disabilities

There are many types of disabilities, such as physical, sensory, cognitive, and mental health disabilities. Physical disabilities affect a person’s movement. Sensory disabilities can affect sight, hearing, or other senses. Cognitive disabilities can affect learning, while mental health disabilities can affect emotions and behaviors.

Living with Disability

Being disabled does not mean a person can’t live a fulfilling life. With the right support, disabled people can perform many tasks and activities. They may use aids like wheelchairs, hearing aids, or special software to assist them.

Respecting People with Disabilities

It’s important to respect and understand people with disabilities. We should not define them by their disability, but see them as unique individuals. By treating them with kindness and empathy, we can help create a more inclusive society.

In conclusion, disability is a part of our diverse world. We should strive to understand and respect people with disabilities, and work towards a society that is inclusive and supportive for all.

250 Words Essay on Disabled Person

A disabled person is someone who has a physical or mental condition that limits their movements, senses, or activities. Their condition might be from birth, due to an accident, or as a result of illness. It’s important to remember that even though they may do things differently, they have the same feelings and desires as anyone else.

There are many types of disabilities. Some people might have trouble moving their body, like those with paralysis. Others might have difficulty learning, remembering, or concentrating, which is often the case with people who have conditions like ADHD or Autism. Some people might not be able to see or hear, or they could have trouble speaking or understanding language.

Challenges Faced

Disabled people often face many challenges. They might find it hard to do things that others take for granted, like walking, reading, or writing. They might also face unfair treatment or discrimination because others do not understand their disability. This can make life difficult and frustrating.

Support and Respect

It’s important to support and respect disabled people. They should be treated with kindness and understanding, just like everyone else. They can do many things if given the right tools and support. For example, a person in a wheelchair can play sports with a specially designed chair. A person who can’t see can read books using Braille.

In conclusion, a disabled person is not defined by their disability. They have unique skills, talents, and abilities. We should treat them with respect and help them overcome their challenges. Remember, everyone is different and that’s what makes us all special.

500 Words Essay on Disabled Person

Understanding disabilities.

A disabled person is someone who has a physical or mental condition that limits their movements, senses, or activities. Disabilities can be present from birth, or they can develop due to an accident or illness. It’s important to know that being disabled doesn’t mean a person is less capable or valuable. They have the same rights and deserve the same respect as everyone else.

There are many types of disabilities. Some people might have trouble moving their bodies, which is called a physical disability. Examples include people who use wheelchairs or those with conditions like cerebral palsy.

There are also mental or intellectual disabilities. These affect a person’s ability to learn or understand things. Conditions like Down syndrome or autism are examples of this.

Sensory disabilities affect a person’s senses, like sight or hearing. People who are blind, deaf, or have low vision or hearing fall into this category.

Finally, some people have invisible disabilities. These are conditions that aren’t obvious to others, like heart disease or mental health conditions.

Challenges Faced by Disabled Persons

Disabled people often face extra challenges in their daily lives. These can include physical barriers, like buildings without ramps or elevators. They may also face social barriers, like negative attitudes or stereotypes.

For example, a person in a wheelchair might not be able to enter a building if there’s no ramp. Or, a person with an invisible disability might face misunderstanding or judgement from others who don’t understand their condition.

Support for Disabled Persons

There are many ways society can support disabled people. This includes laws to protect their rights, like the Americans with Disabilities Act in the United States. This law makes it illegal to discriminate against disabled people in areas like jobs, schools, and public places.

There are also many organizations that provide support and resources for disabled people. These can include special education programs, job training, and help with daily tasks.

Respect and Inclusion

It’s important to treat disabled people with respect and include them in all parts of life. This means not making fun of them or treating them differently just because they have a disability. It also means making sure they have the same opportunities as everyone else.

Inclusion is when everyone, regardless of their abilities, is included in activities and society. This can mean making buildings accessible, providing support in schools, or ensuring equal job opportunities.

In conclusion, understanding and supporting disabled persons is a crucial part of creating a fair and inclusive society. We should all strive to understand the challenges they face and work to create a world where everyone has equal opportunities. Remember, a disability does not define a person, their abilities, and contributions do.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Dignity Of Human Life

- Essay on Dignity And Respect

- Essay on Digitization And Its Benefits

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Ableism: Bias Against People With Disabilities Essay

Ableism denotes social prejudice and bias against people with disabilities (PWD) and in favor of able-bodied individuals. People are not born with such prejudice embedded in them but learn it later in life from the community, the media, parents, and friends, to mention a few. Many people are not as skillful as they ought to be with respect to interrelations with individuals they perceive to be of a different culture or ability. At times, even people with good intentions occasionally say or behave in a prejudiced or biased approach, even unwittingly (Scott, 2016). Social influence is a great aspect that may change a person’s behavior and mindset regarding other people or a group. PWD act as a minority group that is hardly talked about but is greatly oppressed.

Generally, modern society does not appreciate the different talents and abilities of PWD but treats them like castaways. Very little attention is given to PWD, their challenges, and the oppression that they encounter. Impairments are regarded as defects that must be fixed to make people with such disabilities ‘normal’ again (Adjei, 2018). This has been a prevalent manner of thinking where being able-bodied is considered normal. Society is inclined to meeting the demands of the able-bodied while ignoring the needs of PWD.

Ableism entails the application of unsuitable words, unfairness in places of work and learning institutions, denial of service, lack of required amenities, and unequal and discourteous treatment of PWD. Even the practice of favoring the less disabled individual over the more disabled one is deemed a type of ableism.

Ableists, people who are inclined to the ideals of ableism and who practice it, may do it both intentionally and unintentionally. Even strangers, members of the family, colleagues, and peers with good intentions may unintentionally subscribe to the notions of ableists while motivating and encouraging a patient with words such as, “engage in regular exercise so that you walk again and make your life better.” Some forms of disabilities, such as mental disability, are highly stigmatized when judged against others because of the previously associated stereotypes (Silva & Howe, 2018). In this regard, people with schizophrenia and other forms of mental disorders may face stigmatization and discrimination from able-bodied individuals anchored in the mistaken notion of their being dangerous.

Attributable to the increased stigmatization against people with some forms of mental health disorders, many individuals may choose to suffer silently rather than disclose their problems to others for fear of ill-treatment and segregation. For instance, they may fear being labeled, losing their employment positions or housing, going through prejudiced treatment in the provision of necessary services after disclosure of a mental health problem, and dealing with negative attitudes from their peers and members of the community. When this happens, even able-bodied people fail to reap the benefits of the contributions by talented PWD (Goodley, 2014). The fear of being stigmatized may lead to such people not seeking the necessary mental health care until situations arise where the problem is noticed while it is too late to cure it.

In its worst occurrences, ableism may result in society going down the route of euthanasia because of disabilities being considered a departure from the norm and the belief that the continued existence of PWD is worthless. Under such circumstances, failure to provide the required support and services to people with disabilities makes their survival exceedingly hard, and they may end up committing suicide or choosing euthanasia.

On this note, there is a need for the global community to be mindful of the treatment and attitudes towards PWD and avoid practices and dialogues which are ableist (Thompson, 2015). Ableism should not be practiced by anyone in society, and diversity ought to be lionized and acknowledged as a variety of abilities. People concerned with rights advocacy ought to ensure a facilitated awareness of the distressing impacts of ableism through the inclusion of the subject in private and public discussions.

A wide pool of studies affirms that people with disabilities are discriminated against by being treated as if they were outcasts due to their alleged inabilities when judged against able-bodied individuals. However, many approaches may be employed to decrease discrimination against PWD with the application of multidimensional strategies (Berridge & Martinson, 2017). People only need to be enlightened to the fact that everyone has prejudice, but through learning and increasing knowledge, it is easy to eradicate stereotypes and treat people kindly and alike irrespective of their culture, ability, or race. This may be implemented early in children’s lives if a system of education initiates more opportunities and programs for people with disabilities and promotes enhanced intergroup affiliation.

Interrelations involving diverse individuals alter their convictions and sentiments towards one another. In this regard, if one has the chance to interact with others and value their lifestyle, understanding them and eliminating prejudice should be effortless. In ancient times, PWD experienced great discrimination in society. They were mistaken to be foolish, abnormal and were at times compelled to undergo cleansing in an effort to make themselves normal (Berridge & Martinson, 2017). In the 1950s, veterans who had taken part in the Second World War and returned with disabilities started to persuade the government to assist them through the provision of rehabilitation programs. Because the government disregarded their plea, the ex-servicemen started to make disability known across the nation.

In the course of the civil rights movements of the 1960s, activists started to collaborate with PWD and other minority groups to call for the consideration of their issues. In 1964, an act (The Civil Rights Act) was enforced to outlaw discrimination based on ethnic background, gender, and religion. However, this act failed to incorporate PWD. After much activism, only in 1990 was an act to protect the rights of PWD passed: the Americans with Disabilities Act (Thompson, 2015).

The strength of this act lies in its illegalization of prejudice against PWD and its push for equal opportunities for both able-bodied individuals and people with disabilities in the workplace, private, national, and local government services such as transportation and housing, among others.

For PWD, the ability to realize developmental objectives at times relies minimally on their disabilities and more on treatment by family members, colleagues, teachers, and other influential people. The fundamentals of transformation rest in the society’s social and environmental factors. PWD are human beings similar to their able-bodied counterparts and should be treated equally as their disabilities do not classify their skills or personalities. Some of the practices that are vital in helping to eliminate discrimination against people with disabilities include increased awareness about the challenges that they face, educating able-bodied people in the best way of treating them, enhanced interactions, and embracing diversity.

Adjei, P. B. (2018). The (em) bodiment of blackness in a visceral anti-black racism and ableism context. Race Ethnicity and Education , 21 (3), 275-287.

Berridge, C. W., & Martinson, M. (2017). Valuing old age without leveraging ableism. Generations , 41 (4), 83-91.

Goodley, D. (2014). Dis/ability studies: Theorising disablism and ableism . Abingdon, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Scott, P. S. (2016). Addressing ableism in workplace policies and practices: The case for disability standards in employment. Flinders Law Journal , 18 , 121.

Silva, C. F., & Howe, P. D. (2018). The social empowerment of difference: The potential influence of Para sport. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics , 29 (2), 397-408.

Thompson, A. E. (2015). The Americans with Disabilities Act. Jama , 313 (22), 2296-2296.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, May 7). Ableism: Bias Against People With Disabilities. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ableism-bias-against-people-with-disabilities/

"Ableism: Bias Against People With Disabilities." IvyPanda , 7 May 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/ableism-bias-against-people-with-disabilities/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Ableism: Bias Against People With Disabilities'. 7 May.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Ableism: Bias Against People With Disabilities." May 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ableism-bias-against-people-with-disabilities/.

1. IvyPanda . "Ableism: Bias Against People With Disabilities." May 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ableism-bias-against-people-with-disabilities/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Ableism: Bias Against People With Disabilities." May 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ableism-bias-against-people-with-disabilities/.

- Sexism, Racism, Ableism, Ageism, Classism

- Classism, Ableism and Sexism in the 1939 Film “The Hunchback of Notre Dame”

- Discussion: Queer People and Norms

- Diversity Groups and Convict Stereotypes

- Inequality in the United States and Worldwide

- Meaghan Daly’s Speech on Aboriginal Exclusion

- Applying a Portable Concept as a Lens

- Storytelling's Importance for Personal Problems Solving

COMMENTS

You can also find more Essay Writing articles on events, persons, sports, technology and many more. Diverse Nature of Disabilities. As discussed above, disability is a multifaceted and complex state, and may extend to: cognitive function, sensory impairment, physical, self-care limitation, and social functioning impairment.

In 1904, Keller graduated from Radcliffe College, becoming the first deaf-blind person to earn a bachelor of arts. It was at university that her career as a writer and social activist started. Today, the Helen Keller archives contain almost 500 speeches and essays on topics as varied as birth control and Fascism in Europe.

Modern societies have recognized the problems faced by these individuals and passed laws that ease their interactions. We will write a custom essay on your topic. Some people, therefore, believe that life for the disabled has become quite bearable. These changes are not sufficient to eliminate the hurdles associated with their conditions.

More than 1 in 5 people living in the U.S. has a disability, making it the largest minority group in the country. Despite the civil rights law that makes it illegal to discriminate against a ...

The disability study field includes the issues of physical, mental, and learning disabilities, as well as the problem of discrimination. In this article, we've gathered great disability essay topics & research questions, as well as disability topics to talk about. We hope that our collection will inspire you.

1333 Words6 Pages. Disabled people are people who have mental or physical limitation so they depend on someone to support them in doing their daily life needs and jobs. Although disabled people are a minority and they are normally ignored, they are still a part of the society. The statistics show that the proportion of disabled people in the ...

For example, if people treat a child with a disability as incapable of doing anything independently, he will grow up to be inhibited and unlikely to succeed. If he is treated as equal, he will develop a good self-image and achieve a lot in life. We will write a custom essay on your topic. 809 writers online. Learn More.

The Dignity of Disabled Lives. The burden of being perceived as different persists. The solution to this problem is community. Mr. Solomon is a professor of clinical psychology at Columbia ...

Living with Disability. People with disabilities can do many things. They go to school, work, and play sports. Sometimes they need tools or help to do these things. It's important to treat everyone with respect and kindness, no matter what. Support and Rights. Laws protect people with disabilities, giving them the same chances as others.

Respect for persons with disability is important for many reasons. Firstly, it helps them feel valued and included. When they are treated with respect, they feel good about themselves and their abilities. They are more likely to be confident and happy. Secondly, it helps us grow as individuals and as a society.

The Gang of 19 and ADAPT. On July 5, 1978, a group of 19 people gathered at one of the busiest intersections in Denver, at Colfax Avenue and Broadway, got out of their wheelchairs and lay down to ...

Learning about disability involves understanding the challenges people with disabilities face and reflecting on how this knowledge influences professional practice. Recognizing and addressing prejudice and discrimination based on disability are crucial to creating an inclusive environment, both in educational settings and in the wider community.

upenderjoshi28. report flag outlined. Disability is Not A Hindrance. Someone has very wisely said, "Hard things are put in our way, not to stop us, but to call out our courage and strength."People with disabilities are usually the strongest, most courageous and wonderful people. They are usually the strongest, most courageous and wonderful ...

The first treats individuals with disabilities as "objects of policy," resulting in economic and social programs important for subsistence but ultimately constraining and segregating people with disabilities. In the second, those with disabilities are treated as "rights-bearing individuals," empowered and integrated into the society.

There are many types of disabilities, such as physical, sensory, cognitive, and mental health disabilities. Physical disabilities affect a person's movement. Sensory disabilities can affect sight, hearing, or other senses. Cognitive disabilities can affect learning, while mental health disabilities can affect emotions and behaviors.

Ableism denotes social prejudice and bias against people with disabilities (PWD) and in favor of able-bodied individuals. People are not born with such prejudice embedded in them but learn it later in life from the community, the media, parents, and friends, to mention a few. Many people are not as skillful as they ought to be with respect to ...

Answer. Answer: Disability Awareness means educating people regarding disabilities and giving people the knowledge required to carry out a job or task thus separating good practice from poor. It is no longer enough just to know that disability discrimination is unlawfulRaising awareness of different types of disability and how they impact lives ...

This essay begins by discussing the situation of blind people in nineteenth-century Europe. It then describes the invention of Braille and the gradual process of its acceptance within blind education. Subsequently, it explores the wide-ranging effects of this invention on blind people's social and cultural lives.

Educate and train yourself and your team. 4. Communicate and collaborate effectively. 5. Foster a culture of inclusion. 6. Here's what else to consider. Creating an inclusive environment for ...

of mid-April had conducted 650,000 COVID-19 tests of persons with disabilities.3. In the Philippines, the Commission on Human Rights has published information to support health agencies tailor public messages for vulnerable groups of the communities, including children and people with disabilities.4. In Canada, the COVID-19 Disability Advisory ...

Taking an identity-first approach promotes autonomy among and for people with disabilities. Indeed, adopting an identity-first approach instead of a person-first approach is a way to counter the criticism that the latter can occasionally imply that there is something inherently negative about disability. The add-on phrase "with a disability ...