- Daily Crossword

- Word Puzzle

- Word Finder

- Word of the Day

- Synonym of the Day

- Word of the Year

- Language stories

- All featured

- Gender and sexuality

- All pop culture

- Grammar Coach ™

- Writing hub

- Grammar essentials

- Commonly confused

- All writing tips

- Pop culture

- Writing tips

Advertisement

Losing her speech made her feel isolated from humanity.

Synonyms: communication , conversation , parley , parlance

He expresses himself better in speech than in writing.

We waited for some speech that would indicate her true feelings.

Synonyms: talk , mention , comment , asseveration , assertion , observation

a fiery speech.

Synonyms: discourse , talk

- any single utterance of an actor in the course of a play, motion picture, etc.

Synonyms: patois , tongue

Your slovenly speech is holding back your career.

- a field of study devoted to the theory and practice of oral communication.

- Archaic. rumor .

to have speech with somebody

speech therapy

- that which is spoken; utterance

- a talk or address delivered to an audience

- a person's characteristic manner of speaking

- a national or regional language or dialect

- linguistics another word for parole

Discover More

Other words from.

- self-speech noun

Word History and Origins

Origin of speech 1

Synonym Study

Example sentences.

Kids are interacting with Alexas that can record their voice data and influence their speech and social development.

The attorney general delivered a controversial speech Wednesday.

For example, my company, Teknicks, is working with an online K-12 speech and occupational therapy provider.

Instead, it would give tech companies a powerful incentive to limit Brazilians’ freedom of speech at a time of political unrest.

However, the president did give a speech in Suresnes, France, the next day during a ceremony hosted by the American Battle Monuments Commission.

Those are troubling numbers, for unfettered speech is not incidental to a flourishing society.

There is no such thing as speech so hateful or offensive it somehow “justifies” or “legitimizes” the use of violence.

We need to recover and grow the idea that the proper answer to bad speech is more and better speech.

Tend to your own garden, to quote the great sage of free speech, Voltaire, and invite people to follow your example.

The simple, awful truth is that free speech has never been particularly popular in America.

Alessandro turned a grateful look on Ramona as he translated this speech, so in unison with Indian modes of thought and feeling.

And so this is why the clever performer cannot reproduce the effect of a speech of Demosthenes or Daniel Webster.

He said no more in words, but his little blue eyes had an eloquence that left nothing to mere speech.

After pondering over Mr. Blackbird's speech for a few moments he raised his head.

Albinia, I have refrained from speech as long as possible; but this is really too much!

Related Words

More about speech, what is speech .

Speech is the ability to express thoughts and emotions through vocal sounds and gestures. The act of doing this is also known as speech .

Speech is something only humans are capable of doing and this ability has contributed greatly to humanity’s ability to develop civilization. Speech allows humans to communicate much more complex information than animals are able to.

Almost all animals make sounds or noises with the intent to communicate with each other, such as mating calls and yelps of danger. However, animals aren’t actually talking to each other. That is, they aren’t forming sentences or sharing complicated information. Instead, they are making simple noises that trigger another animal’s natural instincts.

While speech does involve making noises, there is a lot more going on than simple grunts and growls. First, humans’ vocal machinery, such as our lungs, throat, vocal chords, and tongue, allows for a wide range of intricate sounds. Second, the human brain is incredibly complex, allowing humans to process vocal sounds and understand combinations of them as words and oral communication. The human brain is essential for speech . While chimpanzees and other apes have vocal organs similar to humans’, their brains are much less advanced and they are unable to learn speech .

Why is speech important?

The first records of the word speech come from before the year 900. It ultimately comes from the Old English word sprecan , meaning “to speak.” Scientists debate on the exact date that humanity first learned to speak, with estimates ranging from 50,000 to 2 million years ago.

Related to the concept of speech is the idea of language . A language is the collection of symbols, sounds, gestures, and anything else that a group of people use to communicate with each other, such as English, Swahili, and American Sign Language . Speech is actually using those things to orally communicate with someone else.

Did you know … ?

But what about birds that “talk”? Parrots in particular are famous for their ability to say human words and sentences. Birds are incapable of speech . What they are actually doing is learning common sounds that humans make and mimicking them. They don’t actually understand what anything they are repeating actually means.

What are real-life examples of speech ?

Speech is essential to human communication.

Dutch is just enough like German that I can read text on signs and screens, but not enough that I can understand speech. — Clark Smith Cox III (@clarkcox) September 8, 2009

I can make squirrels so excited, I could almost swear they understand human speech! — Neil Oliver (@thecoastguy) July 20, 2020

What other words are related to speech ?

- communication

- information

Quiz yourself!

True or False?

Humans are the only animals capable of speech .

Speech Production

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2015

- pp 1493–1498

- Cite this reference work entry

- Laura Docio-Fernandez 3 &

- Carmen García Mateo 4

1215 Accesses

3 Altmetric

Sound generation; Speech system

Speech production is the process of uttering articulated sounds or words, i.e., how humans generate meaningful speech. It is a complex feedback process in which hearing, perception, and information processing in the nervous system and the brain are also involved.

Speaking is in essence the by-product of a necessary bodily process, the expulsion from the lungs of air charged with carbon dioxide after it has fulfilled its function in respiration. Most of the time, one breathes out silently; but it is possible, by contracting and relaxing the vocal tract, to change the characteristics of the air expelled from the lungs.

Introduction

Speech is one of the most natural forms of communication for human beings. Researchers in speech technology are working on developing systems with the ability to understand speech and speak with a human being.

Human-computer interaction is a discipline concerned with the design, evaluation, and implementation...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

T. Hewett, R. Baecker, S. Card, T. Carey, J. Gasen, M. Mantei, G. Perlman, G. Strong, W. Verplank, Chapter 2: Human-computer interaction, in ACM SIGCHI Curricula for Human-Computer Interaction ed. by B. Hefley (ACM, 2007)

Google Scholar

G. Fant, Acoustic Theory of Speech Production , 1st edn. (Mouton, The Hague, 1960)

G. Fant, Glottal flow: models and interaction. J. Phon. 14 , 393–399 (1986)

R.D. Kent, S.G. Adams, G.S. Turner, Models of speech production, in Principles of Experimental Phonetics , ed. by N.J. Lass (Mosby, St. Louis, 1996), pp. 2–45

T.L. Burrows, Speech Processing with Linear and Neural Network Models (1996)

J.R. Deller, J.G. Proakis, J.H.L. Hansen, Discrete-Time Processing of Speech Signals , 1st edn. (Macmillan, New York, 1993)

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Signal Theory and Communications, University of Vigo, Vigo, Spain

Laura Docio-Fernandez

Atlantic Research Center for Information and Communication Technologies, University of Vigo, Pontevedra, Spain

Carmen García Mateo

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Center for Biometrics and Security, Research & National Laboratory of Pattern Recognition, Institute of Automation, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

Departments of Computer Science and Engineering, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA

Anil K. Jain

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Docio-Fernandez, L., García Mateo, C. (2015). Speech Production. In: Li, S.Z., Jain, A.K. (eds) Encyclopedia of Biometrics. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-7488-4_199

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-7488-4_199

Published : 03 July 2015

Publisher Name : Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN : 978-1-4899-7487-7

Online ISBN : 978-1-4899-7488-4

eBook Packages : Computer Science Reference Module Computer Science and Engineering

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

22 The anatomical and physiological basis of human speech production: adaptations and exaptations

Ann MacLarnon is Director of the Centre for Research in Evolutionary Anthropology at Roehampton University. She has worked on a wide variety of areas in primatology and palaeoanthropology, with an emphasis on comparative approaches. Research topics include reproductive life histories and physiology, stress endocrinology and behaviour, and aspects of comparative morphology including the brain and spinal cord. Work on this last area led to the unexpected discovery that humans evolved increased breathing control for speech.

- Published: 18 September 2012

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

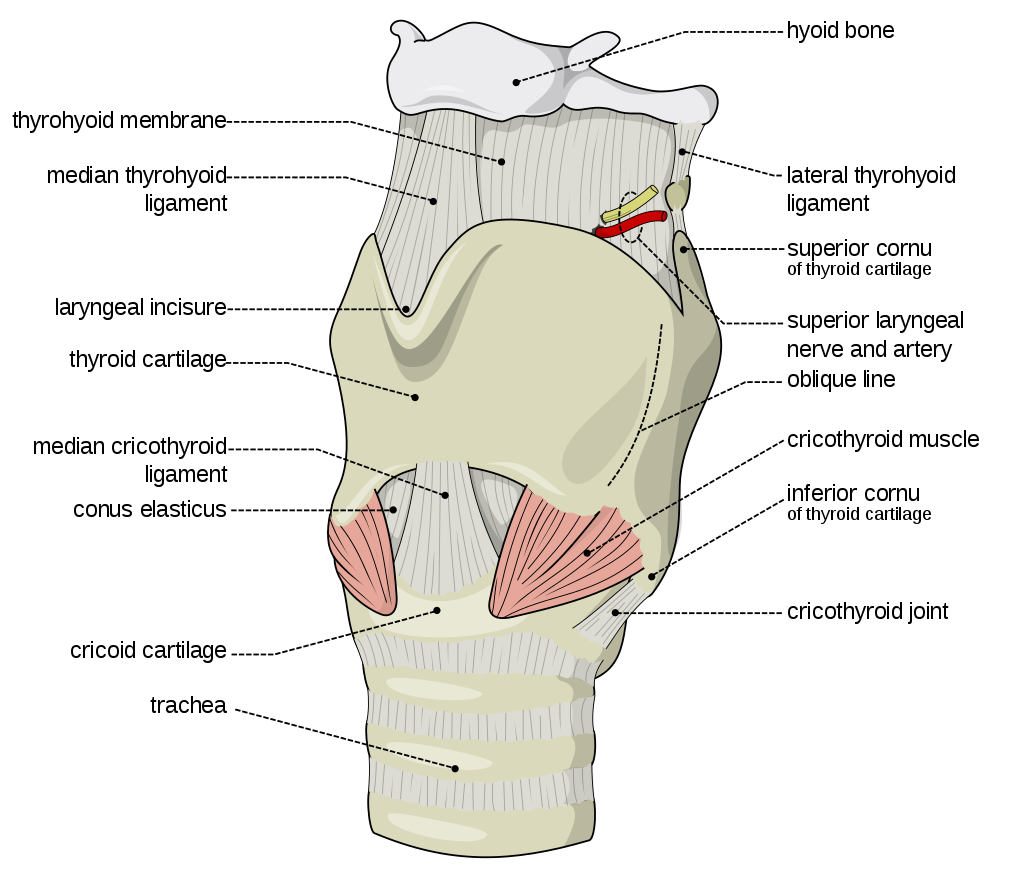

This article provides details on human speech production involving a range of physical features, which may have evolved as specific adaptations for this purpose. All mammalian vocalizations are produced similarly, involving features that primarily evolved for respiration or ingestion. Sounds are produced using the flow of air inhaled through the nose or mouth, or expelled from the lungs. Unvoiced sounds are produced without the involvement of the vocal folds of the larynx. Mammalian vocalizations require coordination of the articulation of the supralaryngeal vocal tract with the flow of air, in or out. An extensive series of harmonics above a fundamental frequency, F 0 for phonated sounds is produced by resonance. These series are filtered by the shape and size of the vocal tract, resulting in the retention of some parts of the series, and diminution or deletion of others, in the emitted vocalization. Human sound sequences are also much more rapid than those of non-human primates, except for very simple sequences such as repetitive trills or quavers. Human vocal tract articulation is much faster, and humans are able to produce multiple sounds on a single breath movement, inhalation or exhalation. The unique form of the tongue within the vocal tract in humans is considered to be a key factor in the speech-related flexibility of supralaryngeal vocal tract.

The major medium for the transmission of human language is vocalization, or speech. Humans use rapid, highly variable, extended sound sequences to transmit the complex information content of language. Speech is a very efficient communication medium: it costs little energetically, it does not require visual contact with the intended receiver(s), and it can be carried out simultaneously with separate manual and other tasks. Although the vocal communication systems of some birds and other mammals, such as cetaceans, may resemble important aspects of human speech, none is as complex, nor as capable of transmitting information, as human speech‐propelled language. Certainly, our closest relatives, the apes and other primates, demonstrate nothing close to this unique human form of communication. Human speech production involves a range of physical features which may have evolved as specific adaptations for this purpose; alternatively, they evolved as exaptations, commandeering existing features. Combining knowledge of the anatomical and physiological basis of human speech production, comparisons with other primate species, and information from the human fossil record, it is possible to form an outline framework for the evolution of human speech capabilities, the features concerned, the likely timing and sequence in which they arose, and the possible combination of adaptations and exaptations involved—the what, when, and why of speech evolution.

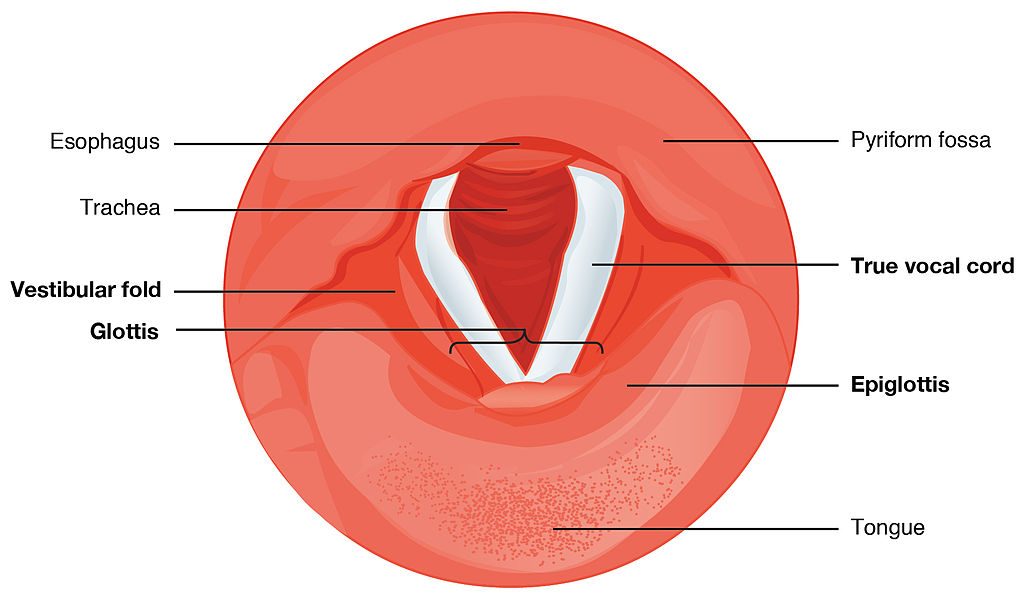

All mammalian vocalizations are produced similarly, involving features that primarily evolved for respiration or ingestion. Sounds are produced using the flow of air inhaled through the nose or mouth, or expelled from the lungs. Unvoiced sounds are produced without the involvement of the vocal folds of the larynx. They entail pressurizing the airflow by temporary restriction of the vocal tract at some point(s) along its length. The turbulence of the released air produces either an aperiodic noise, such as a burst or hiss, or, under special conditions, it may produce a periodic sound such as a whistle. For voiced or phonated sounds, the vocal folds at the glottis of the larynx (a structure which first evolved at the top of the trachea to prevent water entering the lungs in aquatic creatures) are held taut, and the air flow needs to be powerful enough to cause the vocal folds to vibrate. This cuts the air flow into a chain of ‘air puffs’, or a periodic sound wave, perceived by the ear as sound at a pitch equivalent to the air puff frequency; this is known as the fundamental frequency or F 0 , and it varies with the length and tension of the vocal folds. Voiced sounds may be modified further by so‐called gestural articulations of the supralaryngeal vocal tract produced by positions or movements of articulatory structures such as the tongue and lips, both primarily involved in ingestion. Mammalian vocalizations therefore require coordination of the articulation of the supralaryngeal vocal tract with the flow of air, in or out. For phonated sounds, an extensive series of harmonics above F 0 is produced by resonance. These series are filtered by the shape and size of the vocal tract, resulting in the retention of some parts of the series, and diminution or deletion of others, in the emitted vocalization. Unvoiced vocalizations generally have less structured acoustic features and broad bands of emitted frequencies. What distinguishes human speech from the vocalizations of other species is the extraordinary range of acoustic variation involved, produced by an enormous variety of gestural articulations of the vocal tract, together with intricate manipulations of the larynx and other respiratory structures. Rather than utilizing the air flow of both inspirations and expirations, human speech is also produced almost entirely on expired air, released in extended, highly controlled expirations.

More than 100 different sound units or phonemes found in human languages are recognized in the International Phonetic Alphabet, together with a further array of major variant types. Each sound unit is acoustically distinctive (Fant 1960 ), as depicted in spectrograms, in which emitted sound frequencies and their amplitudes are plotted against time. Phonemes vary with different relative timing of the start of phonation and of vocal tract constriction, different speeds of movement and combinations of vocal tract articulators, different intonation changes produced in the larynx or by the lungs; sounds may be breathy, creaky, nasal, or aspirated, and so the list goes on. Different languages use different subsets of phonemes.

Phonemes comprise consonants and vowels, which form the building blocks of syllables. Consonants, voiced or unvoiced, involve the complete or near complete obstruction and release of airflow through the vocal tract, which produces characteristic spectrum profiles or envelopes of sound frequencies emitted over time (Fant 1960 ). Vowels always involve phonation, and filtering through different vocal tract constrictions produced by gestures of the tongue, without complete obstruction. They are distinguished by their combinations of formants (Fant 1960 ), which are sharp peaks in the frequency ranges above F 0 emitted following filtration, known as F 1 , F 2 , etc.; typically, different vowels within a language can be characterized by the first two formants. The perception of vowels is not dependent on their absolute formant frequencies, but rather their relative values, normalized by the listener according to the typical frequency levels of a particular individual speaker, be they generally higher or lower pitched, the differences resulting from a shorter or longer vocal tract.

The range and variation of human speech sounds, the different subsets utilized in hundreds of languages, and how they are produced anatomically and physiologically, have been superbly documented in an extraordinary compendium by Ladefoged and Maddieson ( 1996 ). For consonants, they describe how nine independent, moveable, soft tissue articulators can be distinguished: lips; tongue—tip, blade, underblade, front, back, root; epiglottis; and glottis. These move to constrict or block the vocal tract at 11 main articulation points, or more accurately zones: lips, incisor teeth, different points along the palate, the velum or soft palate, and the uvula (the skin flap hanging from the velum), the pharynx or throat, the epiglottis, and the glottis. Together these produce 17 different categories of articulatory gestures, whose precise formation varies in different languages and dialects. Consonants are further differentiated into stops, nasals, fricatives, laterals, rhotics, and clicks, according to whether they involve, respectively, momentary complete stoppage of airflow by vocal tract obstruction, mouth closure and nasal‐only airflow, a turbulent airstream, midline tract closure limited with lateral airflow around the partial obstruction, tongue trills and related movements, or two points of vocal tract closure trapping air with subsequent articulator movement increasing the trapped air volume and hence decreasing pressure prior to its sudden release. Vowel production involves subtle tongue‐shaping in the oral or pharyngeal cavities, resulting in different points of vocal tract constriction, and hence different formant combinations.

It became evident early in attempts to teach apes to speak that our closest living relatives are not capable of the intricate articulatory manoeuvres of the upper respiratory tract which underlie the enormous range of human speech sounds. Recent evidence from Diana monkeys suggests that vocal tract articulation in non‐human primates may not be as severely limited as previously thought (Riede et al. 2005 ). However, it seems improbable that capabilities so useful to human communication would not have been exploited more fully if they existed in other species, and it is therefore likely that the human capacity for the production of highly varied speech sounds is unique among primates.

Human sound sequences are also much more rapid than those of non‐human primates, except for very simple sequences such as repetitive trills or quavers. Human vocal tract articulation is much faster, and humans are able to produce multiple sounds on a single breath movement, inhalation or exhalation. Most non‐human sound sequences, such as chimpanzee pant‐hoots and other vocalizations (Marler and Tenaza 1977 ), are produced on successive inspirations and expirations. Commonly each component sound of such sequences (e.g. the pant, or the hoot of the chimpanzee call) can only be produced on either an inhalation or an exhalation, which also restricts sound sequence combinations.

The laryngeal air sacs present in some non‐human primate species enable them to produce slightly more complex sound sequences on single breath movements, either through additional breath movements in and out of the sacs, or by vibration of the vocal lip at the opening of the sacs into the larynx (e.g. bitonal scream of siamangs; Haimoff 1983 ). Humans do not possess air sacs, and instead produce complex sound sequences by the intricate manipulation of airflow within individual exhalations, freed much more than any non‐human primate from the restrictions of vocalizations tied to breath movements (Hewitt et al. 2002 ). Overall, humans are able to produce sound sequences of up to about 30 sound units per second (P. Lieberman et al. 1992 ). Maximum sound production rates for non‐human primates are typically only 2–3 per second, extending to 5 per second with the involvement of air sacs (MacLarnon and Hewitt 1999 ).

Human speech also demonstrates further flexibility through an enhanced ability to control breathing, the airflow itself, compared with non‐human primates (MacLarnon and Hewitt 1999 , 2004 ). First, humans speak on very extended exhalations, interspersed with quick inhalations, compared with much more even breathing cycles during quiet breathing; non‐human primates appear not to be able to distort their breathing cycles so markedly. During normal speech, humans typically utilize exhalations of 4–5 seconds (Hoit et al. 1994 ), extending up to more than 12 seconds (Winkworth et al. 1995 ), whereas the longest calls given on single breath movements in non‐human primates are only about 5 seconds (MacLarnon and Hewitt 1999 ). Calibrating these measures, taking into account the faster quiet breathing rates of smaller animals, the maximum duration of human speech exhalations is more than 7 times that during quiet breathing. In non‐human primates, the normal maximum duration of exhalations during vocalization is only 2–3 times that during quiet breathing. The exceptions to this are species with air sacs, such as howler monkeys and gibbons, which can extend exhalations to 4–5‐fold their duration during quiet breathing. Again, humans do not possess air sacs, an apparent alternative to control of pulmonary air release for extending call exhalation length, though one that does not enable the very subtle control of respiratory airflow of human speech (Hewitt et al. 2002 ).

22.1 Sound articulation

The unique form of the tongue within the vocal tract in humans is considered to be a key factor in the speech‐related flexibility of our supralaryngeal vocal tract (P. Lieberman 1984 ). In mammals, the tongue is typically a flat muscular structure lying largely within the oral cavity, anchored posteriorly by its attachment to the hyoid bone, which lies just below oral level in the pharynx, immediately above the larynx. The primary function of the tongue is to move food around the mouth for mastication, and posteriorly for swallowing. In humans, however, the tongue is a curved structure, lying part horizontally in the oral cavity and part vertically down an extended pharynx, where it attaches to a much lower hyoid, just above a descended larynx. The horizontal (oral) and vertical (pharyngeal) portions of the human supralaryngeal tract (SVT H and SVT V ) are equal in length, compared with other species in which SVT H is substantially longer. Greatly because of its curvature, movement of the human tongue, together with jaw movements, can vary the cross‐sectional area of each of the two tubes of our vocal tract independently by a factor of approximately ten, providing a very broad range of articulatory gestures, and very variable resultant formants of emitted sound. The 1:1 ratio of SVT H :SVT V , with a sharp bend between the two, is notably important for the production of three vowels, designated phonetically [i], [u], and [a]. These vowels are particularly easily distinguished, with very low perceptual error rates, by their F1, F2 combinations, which lie at the outer limits of the acoustic vowel space, and [i], followed by [u], is the most reliable and commonly used sound unit for vocal tract normalization. The tongue positions for production of the three vowels utilize the angle at the midpoint of the human vocal tract to produce abrupt discontinuities in the cross‐sectional areas of the tube. Because the angle is sharp, the articulatory gestures involved do not have to be performed with particular accuracy for consistent, distinctive acoustic results, making these vowels marked examples of the quantal nature of human speech sounds (Stevens 1972 ). Perhaps consequently, they are the most common vowels in the world's languages (Ladefoged and Maddieson 1996 ).

Humans are not completely unique in having a descended larynx; species including dog, goat, pig, and tamarin lower the larynx during loud calls (Fitch 2001b ). Several deer have a permanently lowered larynx, which may temporarily be lowered further during male roars (Fitch and Reby 2001 ); large cats are apparently similar (Weissengruber et al. 2002 ). However, laryngeal descent is rarely accompanied by descent of the hyoid; hence the tongue remains horizontal in the oral cavity, and cannot act as a pharyngeal articulator (P. Lieberman 2007 ). Temporary laryngeal descent is also much less disruptive of other functions. In humans, because of marked, permanent laryngeal descent, simple contact between the epiglottis and velum is no longer possible, disrupting the normal mammalian separation of the respiratory and digestive tracts during swallowing, and increasing the risk of choking. Permanent laryngeal descent is thus a very different evolutionary development. Nishimura et al. ( 2006 ) have demonstrated that the larynx does descend to some extent during development in chimpanzees, followed by hyoidal descent. However, only humans have evolved permanent, major, laryngeal descent, with associated hyoidal descent, resulting in a curved tongue, and a two‐tube vocal tract with 1:1 proportions. It is not laryngeal descent per se that is crucial to human speech capabilities, but rather a suite of factors in the shape and proportions of the supralaryngeal vocal tract and tongue (P. Lieberman 2007 ).

Considerable efforts have been made to determine when the two‐tube vocal tract evolved in our ancestors, using indirect means, as its soft tissue structures do not fossilize. Reconstruction of the fossil hominin tract was first attempted by Philip Lieberman and Crelin ( 1971 ), using basicranial and mandibular characteristics, followed by Laitman and colleagues (e.g. 1979), who used the basicranial angle, or flexion of the skull base. However, Daniel Lieberman and McCarthy ( 1999 ) recently demonstrated, using radiographic series, that human laryngeal descent is not linked ontogenetically to the development of basicranial flexion. So, reconstruction of the supralaryngeal tract is not possible from basicranial form, and much previous work on the speech articulation capabilities of fossil hominins was therefore flawed, as P. Lieberman ( 2007 ) has fully accepted. In addition, D. Lieberman et al. ( 2001 ) showed that during postnatal descent of the hyoid and larynx in humans, the relative vertical positions of the hyoid, mandible, hard palate and larynx are held more or less constant. However, the ratio SVT H :SVT V changes during development, as a result of differential growth patterns of the total oral and pharyngeal lengths, and only reaches 1:1 from about 6–8 years. Together these results indicate that the descent of the hyolaryngeal structures is primarily constrained to maintain muscular function in relation to mandibular movement for swallowing; speech‐related factors are not maximized until well into childhood, matching the gradual ontogenetic development of acoustically accurate speech production (P. Lieberman 1980 ). Various possible exaptive explanations for why humans evolved their unique vocal tract configuration have been proposed. For example, obligate bipedalism required a more forward position of the spine under the skull, possibly reducing the space available in the upper throat, so squeezing the hyoid and larynx down the pharynx; increased carnivory in early Homo was associated with reduced jaw size and reduced oral cavity length, possibly requiring a compensatory increase in pharyngeal length (Negus 1949 ; Aiello 1996 ).

Recently, D. Lieberman and colleagues (e.g. 2002) have produced substantial new evidence on the integrated evolution of many modern human cranial features, providing a more comprehensive basis for exploring the evolution of the human vocal tract. They showed that a small number of developmental shifts distinguish modern human crania from those of our predecessors, including two—a more flexed basicranium and reduction in face size—which result in a shortening of SVT H , contributing to the attainment of an SVT H :SVT V ratio of 1:1. D. Lieberman ( 2008 ) suggested possible adaptational bases for these shifts, such as temporal lobe increase for enhanced cognitive processing including language, increasing basicranial flexion; increased meat consumption and technologically enhanced food processing including cooking, resulting in facial reduction; endurance running, building on obligate bipedalism, involving facial reduction for improved head stabilization; direct selection for speech capabilities, driving a decrease in oral cavity length, involving facial reduction and/or basicranial flexion, to produce a 1:1 SVT H :SVT V ratio. In other words, a suite of factors may have affected SVT H , and hence played a part in the evolution of the modern human capability for quantal speech. The other component in the evolution of a 1:1 ratio, an increase in SVT V , may have been directly selected for enhanced speech capabilities, so counterbalancing the negative impact of increased choking risk. However, this would not have been advantageous prior to substantial decrease in SVT H , because a long SVT V would require laryngeal descent into the thorax, producing muscular orientations that would compromise functional swallowing. Rather than major, coordinated shifts in both vocal tract parameters occurring with the evolution of modern humans, I think it more probable that other factors, earlier in human evolution, produced descent of the hyolaryngeal complex, and an increase in SVT V . From this exaptive basis, final reduction in SVT H, with the evolution of modern human cranial shape, could be adaptive for quantal speech. As outlined above, maintenance of functional swallowing is central to human developmental hyolaryngeal descent, which only becomes advantageous for speech articulation later in childhood. This, too, is congruent with the suggestion that hyolaryngeal descent resulted from earlier evolutionary change. The most likely candidate is the evolution of bipedalism, involving reconfiguration of neck structures, in Homo erectus . Jaw length also reduced in this species, associated with changing diet and food processing. The use of more complex vocalizations for communication may have begun to increase at the same time, alongside brain size and presumed social complexity (Aiello 1996 ).

As well as its curved shape, other features of the tongue have also been explored for their potential contribution to human speech articulation. Duchin ( 1990 ) drew attention to the greater manoeuvrability of the human tongue compared with apes. Jaw reduction produces a shorter, more controllable tongue, and hyoidal descent angles the tongue, increasing mechanical advantage. Takemoto ( 2008 ) showed that chimpanzee and human tongues have the same detailed internal topology, a muscular hydrostat formation (Kier and Smith 1985 ), which enables elongation, shortening, thinning, fattening, and twisting of the tongue for moving food around the mouth and for swallowing. However, the overall curved shape of the human tongue, compared with the flat chimpanzee form, means the same internal structures are arranged radially in humans, compared with linearly in apes, which increases the degrees of freedom for tongue deformation (Takemoto 2008 ). Hence, the dietary and other changes from early Homo through to modern humans provided the potential for enhanced control of speech articulation gestures through exaptive realignment of both external and internal tongue features.

The lips are second only to the tongue in their importance as human speech articulators. They are particularly important for the production of two major consonant groups, stops and fricatives (the former being the only consonant type to occur in all languages), and also in vowel production (Ladefoged and Maddieson 1996 ). In typical mammals, the face is dominated by a prominent snout housing major structures of the highly developed olfactory sense, which extend onto the face, in the form of the rhinarium, or wet nose. Within primates, the evolution of the haplorhines (tarsiers, monkeys, and apes) involved a shift to diurnal activity from the typical mammalian nocturnal pattern retained by strepsirhines (lemurs and lorises). With this came increased specialization of the visual sense, and an associated reduction in olfaction. The snout reduced, and the rhinarium was lost. As a result, the facial and lip muscles became less constrained and were co‐opted for facial expressions. Haplorhines evolved thicker lips (Schön Ybarra 1995 ), presumably to enhance this function. Hence, the evolution of mobile, muscular lips, so important to human speech, was the exaptive result of the evolution of diurnality and visual communication in the common ancestor of haplorhines. There is a lack of evidence as to whether there have been further adaptational developments in the lips during human evolution, or whether there have been changes in some other articulators, such as the velum or the epiglottis.

To date, there has been one attempt to investigate the comparative innervation of human vocal tract articulators. Kay et al. ( 1998 ) used the size of the hypoglossal canal in the base of the skull to estimate the relative number of nerve fibres in the hypoglossal nerve, which is a major innervator of the tongue. Their results suggested that Middle Pleistocene hominins and Neanderthals had modern human levels of tongue innervation, substantially greater than found in australopithecines and apes, and hence, they suggested, human‐like speech‐related tongue control had evolved by this time. However, DeGusta et al. ( 1999 ) demonstrated that hypoglossal canal and nerve sizes are not correlated, and Jungers et al. ( 2003 ) accepted that the canal size therefore offers no evidence about the timing of human speech evolution. Split second coordination between the highly flexible movements of the human speech articulators is required for human speech, as well as coordination with laryngeal movements affecting phonation. Different sounds result, for example, if the vocal cords start vibrating slightly before, at the same time, or slightly after an articulatory gesture. It seems likely that at least some increase in neural control has evolved in humans for speech articulation, even if empirical evidence is presently lacking.

22.2 Respiratory control

Humans have enhanced control of breathing compared with non‐human primates, which they use to extend exhalations and shorten inhalations during speech, as well as to modulate loudness. Humans are not constrained to produce vocalizations that fade as the lungs deflate. They can also vary the volume of air released through a phrase to emphasize particular words or syllables. In addition, variation in subglottal air pressure can affect intonation patterns. Enhanced breathing control therefore contributes to the human ability to produce fast sound sequences, and to generate a whole variety of language‐specific patterns and meanings, communicated through the intonation and emphasis of phrases or specific syllables. Much of this needs to be tied to cognitive intention, involving complex neural communication and feedback (MacLarnon and Hewitt 1999 ).

Control of subglottal pressure is key to human speech breathing control. During speech breathing, intercostal and anterior abdominal muscles are recruited to expand the thorax and draw air into the lungs, and to control gravitational recoil and hence the release of air as the lungs deflate. This is similar to quiet breathing, except that the diaphragm has a very limited role in speech breathing. It also differs from muscle recruitment during non‐human primate vocalizations, which does involve the diaphragm, and has only a limited role for intercostal muscles (e.g. Jürgens and Schriever 1991 ). The specific muscle movements required vary according to the volume of the lungs and other actions undertaken simultaneously (MacLarnon and Hewitt 1999 ). Overall, the fineness of control required of the intercostal muscles during human speech has been likened to that of the small muscles of the hand (Campbell 1968 ).

There is evidence, from an increase in spinal cord grey matter in the thoracic region, that humans have markedly greater innervation of the intercostal and anterior abdominal muscles compared with non‐human primates (MacLarnon 1993 ). Spinal cord dimensions are well correlated with those of its bony encasement, the vertebral canal. Evidence from fossil hominins demonstrates that enlargement of the canal, and therefore the cord, was not present in australopithecines and Homo erectus , but was present in Neanderthals and early modern humans (MacLarnon and Hewitt 1999 ). The function requiring enhanced neurological control therefore evolved in later human evolution. Of all the functions of the intercostal muscles, including maintenance of body posture for bipedal locomotion, vomiting, coughing, defecation, and breathing control, only enhanced breathing control for speech both requires substantial neurological control and fits the evolutionary timing constraints. It appears, therefore, that enhanced breathing control for speech was absent in Homo erectus , and present in the common ancestor of Neanderthals and modern humans, in the later Middle Pleistocene (MacLarnon and Hewitt 1999 , 2004 ).

As outlined above, human breathing control is not aided by the presence of air sacs, which can provide additional re‐breathed air for the extension of exhalations, without the risk of hyperventilation from excess oxygen intake (Hewitt et al. 2002 ). Larger ape species all possess laryngeal air sacs, so they were presumably lost at some point during human evolution. Air sacs abut against the hyoid bone where they produce characteristic indentions. The australopithecine hyoid from Dikika demonstrates the presence of air sacs (Alemseged et al. 2006 ), whereas hyoids from Homo heidelbergensis at Atapuerca, and a specimen from Castel di Guido dated to 400,000 years ago, as well as Neanderthals from El Sidrón and Kebara (Arensburg et al. 1990 ; Capasso et al. 2008 ; Martínez et al. 2008 ), show that air sacs had been lost by some point in the Middle Pleistocene. One possibility is that this occurred when the human thorax altered from the funnel‐shape of australopithecines, to the barrel‐shape of Homo erectus , as, in apes, air sacs extend into the thorax. It therefore quite probably occurred prior to the evolution of human speech‐breathing control, and it may also have been a necessary prerequisite stage.

The mammalian larynx, which protects the entrance to the lungs during swallowing, comprises a series of three sets of articulating cartilages connected by ligaments and membranes. Some mammal species retain a non‐valvular larynx, in which occlusion involves a simple muscular sphincter; other species have a valvular larynx, in which a mechanical valve provides for closure at the glottis. Based on the distribution of the valvular form, including its greatest development in primates, Negus ( 1949 ) proposed that the valvular larynx is a locomotor adaptation, enabling greater stabilization of the thorax in species with independent use of the forelimbs, through build up of air pressure below a closed glottis. Humans share with gibbons an extreme ability to close the glottis; other primates cannot completely close it off as the inner edges of the vocal processes of their arytenoid cartilages are curved, and when brought together, a small hiatus intervocalis always remains (Schön Ybarra 1995 ). Most likely humans lost the hiatus intervocalis independently from gibbons, as it is retained in living great apes. Gibbons may have evolved complete closure as an adaptation to brachiation. Bipedal humans use the capability of building up high subglottal pressure while lifting heavy objects with their arms, and in forceful coughing, which is particularly important with upright posture (Aiello and Dean 1990 ). In addition, for human speech, substantial subglottal air pressure is required to fuel very long exhalations. Complete glottal closure enhances the ability to control the pitch or intonation (Kelemen 1969 ), something which gibbons use in their songs, and humans use in speech, although it is unclear whether subglottal air pressure, or movements of the laryngeal cricothyroid muscle are more important in human control of intonation (Borden et al. 2003 ). Overall, humans probably lost the hiatus intervocalis as an adaptation to bipedalism, providing an exaptation for speech. Further to this, the membranous part of the vocal folds of humans is less sharp‐edged than in other primates (Negus 1929 ). This may be a direct adaptation for the production of more melodious sounds, selected for at some point after the locomotor‐associated function of the larynx altered in humans, with the evolution of exclusive bipedality in Homo erectus (Aiello 1996 ).

22.3 Evolutionary framework

Diet and technology‐related changes through human evolution, from the time of early Homo , have produced decreases in jaw and tongue length exaptive for the evolution of human speech capabilities. In addition to these, a three‐stage framework for the major features of human speech evolution can tentatively be proposed: first, the evolution of obligate bipedalism in Homo erectus produced the exaptations of laryngeal descent, and the loss of air sacs and the hiatus intervocalis; secondly, during the Middle Pleistocene, human speech breathing control evolved as a specific speech adaptation; thirdly, with the evolution of modern humans, the optimal vocal tract proportions (1:1) were evolved adaptively. Further details are summarized in Table 22.1 , together with suggested speech capabilities for each stage of the evolutionary framework.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Kathleen Gibson and Maggie Tallerman for the invitation to contribute to this volume, and for their very helpful editing. My interest in the evolution of human speech was first stimulated by stumbling on evidence for the evolution of human breathing control working with Gwen Hewitt. This paper builds on a lecture prepared for the Language Origins Society, thanks to an invitation from Bernard Bichakjian.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2.1 How Humans Produce Speech

Phonetics studies human speech. Speech is produced by bringing air from the lungs to the larynx (respiration), where the vocal folds may be held open to allow the air to pass through or may vibrate to make a sound (phonation). The airflow from the lungs is then shaped by the articulators in the mouth and nose (articulation).

Check Yourself

Video script.

The field of phonetics studies the sounds of human speech. When we study speech sounds we can consider them from two angles. Acoustic phonetics , in addition to being part of linguistics, is also a branch of physics. It’s concerned with the physical, acoustic properties of the sound waves that we produce. We’ll talk some about the acoustics of speech sounds, but we’re primarily interested in articulatory phonetics , that is, how we humans use our bodies to produce speech sounds. Producing speech needs three mechanisms.

The first is a source of energy. Anything that makes a sound needs a source of energy. For human speech sounds, the air flowing from our lungs provides energy.

The second is a source of the sound: air flowing from the lungs arrives at the larynx. Put your hand on the front of your throat and gently feel the bony part under your skin. That’s the front of your larynx . It’s not actually made of bone; it’s cartilage and muscle. This picture shows what the larynx looks like from the front.

This next picture is a view down a person’s throat.

What you see here is that the opening of the larynx can be covered by two triangle-shaped pieces of skin. These are often called “vocal cords” but they’re not really like cords or strings. A better name for them is vocal folds .

The opening between the vocal folds is called the glottis .

We can control our vocal folds to make a sound. I want you to try this out so take a moment and close your door or make sure there’s no one around that you might disturb.

First I want you to say the word “uh-oh”. Now say it again, but stop half-way through, “Uh-”. When you do that, you’ve closed your vocal folds by bringing them together. This stops the air flowing through your vocal tract. That little silence in the middle of “uh-oh” is called a glottal stop because the air is stopped completely when the vocal folds close off the glottis.

Now I want you to open your mouth and breathe out quietly, “haaaaaaah”. When you do this, your vocal folds are open and the air is passing freely through the glottis.

Now breathe out again and say “aaah”, as if the doctor is looking down your throat. To make that “aaaah” sound, you’re holding your vocal folds close together and vibrating them rapidly.

When we speak, we make some sounds with vocal folds open, and some with vocal folds vibrating. Put your hand on the front of your larynx again and make a long “SSSSS” sound. Now switch and make a “ZZZZZ” sound. You can feel your larynx vibrate on “ZZZZZ” but not on “SSSSS”. That’s because [s] is a voiceless sound, made with the vocal folds held open, and [z] is a voiced sound, where we vibrate the vocal folds. Do it again and feel the difference between voiced and voiceless.

Now take your hand off your larynx and plug your ears and make the two sounds again with your ears plugged. You can hear the difference between voiceless and voiced sounds inside your head.

I said at the beginning that there are three crucial mechanisms involved in producing speech, and so far we’ve looked at only two:

- Energy comes from the air supplied by the lungs.

- The vocal folds produce sound at the larynx.

- The sound is then filtered, or shaped, by the articulators .

The oral cavity is the space in your mouth. The nasal cavity, obviously, is the space inside and behind your nose. And of course, we use our tongues, lips, teeth and jaws to articulate speech as well. In the next unit, we’ll look in more detail at how we use our articulators.

So to sum up, the three mechanisms that we use to produce speech are:

- respiration at the lungs,

- phonation at the larynx, and

- articulation in the mouth.

Essentials of Linguistics Copyright © 2018 by Catherine Anderson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Speech in Linguistics

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

In linguistics , speech is a system of communication that uses spoken words (or sound symbols ).

The study of speech sounds (or spoken language ) is the branch of linguistics known as phonetics . The study of sound changes in a language is phonology . For a discussion of speeches in rhetoric and oratory , see Speech (Rhetoric) .

Etymology: From the Old English, "to speak"

Studying Language Without Making Judgements

- "Many people believe that written language is more prestigious than spoken language--its form is likely to be closer to Standard English , it dominates education and is used as the language of public administration. In linguistic terms, however, neither speech nor writing can be seen as superior. Linguists are more interested in observing and describing all forms of language in use than in making social and cultural judgements with no linguistic basis." (Sara Thorne, Mastering Advanced English Language , 2nd ed. Palgrave Macmillan, 2008)

Speech Sounds and Duality

- "The very simplest element of speech --and by 'speech' we shall henceforth mean the auditory system of speech symbolism, the flow of spoken words--is the individual sound, though, . . . the sound is not itself a simple structure but the resultant of a series of independent, yet closely correlated, adjustments in the organs of speech." ( Edward Sapir , Language: An Introduction to the Study of Speech , 1921)

- "Human language is organized at two levels or layers simultaneously. This property is called duality (or 'double articulation'). In speech production, we have a physical level at which we can produce individual sounds, like n , b and i . As individual sounds, none of these discrete forms has any intrinsic meaning . In a particular combination such as bin , we have another level producing a meaning that is different from the meaning of the combination in nib . So, at one level, we have distinct sounds, and, at another level, we have distinct meanings. This duality of levels is, in fact, one of the most economical features of human language because, with a limited set of discrete sounds, we are capable of producing a very large number of sound combinations (e.g. words) which are distinct in meaning." (George Yule, The Study of Language , 3rd ed. Cambridge University Press, 2006)

Approaches to Speech

- "Once we decide to begin an analysis of speech , we can approach it on various levels. At one level, speech is a matter of anatomy and physiology: we can study organs such as tongue and larynx in the production of speech. Taking another perspective, we can focus on the speech sounds produced by these organs--the units that we commonly try to identify by letters , such as a 'b-sound' or an 'm-sound.' But speech is also transmitted as sound waves, which means that we can also investigate the properties of the sound waves themselves. Taking yet another approach, the term 'sounds' is a reminder that speech is intended to be heard or perceived and that it is therefore possible to focus on the way in which a listener analyzes or processes a sound wave." (J. E. Clark and C. Yallop, An Introduction to Phonetics and Phonology . Wiley-Blackwell, 1995)

Parallel Transmission

- "Because so much of our lives in a literate society has been spent dealing with speech recorded as letters and text in which spaces do separate letters and words, it can be extremely difficult to understand that spoken language simply does not have this characteristic. . . . [A]lthough we write, perceive, and (to a degree) cognitively process speech linearly--one sound followed by another--the actual sensory signal our ear encounters is not composed of discretely separated bits. This is an amazing aspect of our linguistic abilities, but on further thought one can see that it is a very useful one. The fact that speech can encode and transmit information about multiple linguistic events in parallel means that the speech signal is a very efficient and optimized way of encoding and sending information between individuals. This property of speech has been called parallel transmission ." (Dani Byrd and Toben H. Mintz, Discovering Speech, Words, and Mind . Wiley-Blackwell, 2010)

Oliver Goldsmith on the True Nature of Speech

- "It is usually said by grammarians , that the use of language is to express our wants and desires; but men who know the world hold, and I think with some show of reason, that he who best knows how to keep his necessities private is the most likely person to have them redressed; and that the true use of speech is not so much to express our wants, as to conceal them." (Oliver Goldsmith, "On the Use of Language." The Bee , October 20, 1759)

Pronunciation: SPEECH

- Duality of Patterning in Language

- Phonology: Definition and Observations

- What Is Phonetics?

- Definition and Examples of Productivity in Language

- Spoken English

- Definition of Voice in Phonetics and Phonology

- Phonological Segments

- What Are Utterances in English (Speech)?

- Grapheme: Letters, Punctuation, and More

- What Is a Phoneme?

- Phoneme vs. Minimal Pair in English Phonetics

- Connected Speech

- What Is Graphemics? Definition and Examples

- 10 Titillating Types of Sound Effects in Language

- Assimilation in Speech

The Parts of Human Speech Organs & Their Definitions

Types of Phonetics