- Deutsch |

- Español |

- Français |

ASSESSMENT TAKER

Just enter the test ID provided and click GO.

Access dashboard, create tests, view reports, and more.

Understanding Recruitment Sources

In today’s recruiting landscape, most candidates find their way to a position through a multitude of sources, directly and indirectly. The recruiting process snakes back to student job fairs and brand marketing, leading to talent pools and finally hires. Gone are the days of knowing exactly where a company makes first contact with a candidate, of simply posting a job ad in the classifieds section of the local newspaper and getting responses only from people who saw it. Now the points of contact are more numerous and happen at different stages of the recruitment process.

Determining where candidates are finding your company and your job openings has become harder than ever, which means it’s tough to figure out what sources of recruitment you should spend more time and money on to reach the largest talent pool. The answer, albeit not ideal or straightforward, is that you should continue to focus on most of them. Candidates are reached in a myriad of ways, and to stay competitive in the recruiting market you should continue to reach them wherever they are.

Here are the top 9 recruitment sources your company should continuously leverage to reach the best talent out there.

- Job Boards. Perhaps one of the main recruitment sources, job boards have grown thanks to the ease of online job searches. Think of where your talent pool would go to find a job—if you’re looking for a graphic designer, post your job on boards that designers usually visit. Post jobs in general job boards as well, especially when looking for entry-level candidates, as they tend to go there first.

- Company Website. Posting all job opportunities on your company’s website is a given. Whether candidates arrive there directly or are directed there from another site, this is the place where all your recruiting lives. On your own website, you can post not only job openings but also FAQ’s about working at your company, like benefits offered and anything that helps your company stand out.

- ‘> Social Media. LinkedIn, Google+, Facebook, Twitter, among others—these social media networks are key recruiting sources. Nowadays most candidates are on one or all of these networks, making them a perfect place to promote your job openings. Yet social media is not just for posting jobs; it also offers an opportunity for a conversation. It’s a place where you can promote your company’s brand and contribute insightful information about your company and industry. Once you build a foundation with your followers, they’ll be more likely to come directly to you when seeking a new job.

- Referrals. One of the fastest growing recruiting sources out there is employee referrals. Tapping into your existing workforce to get new talent is a smart strategy. Consider offering referral incentives, like bonuses. Make sure your employees know that they can refer candidates to current openings. Establish a system for doing so, whether it’s having the employee submitting the candidate’s resume for him or specifically asking for an employee referral in all your job applications.

- Direct Contact. Similar to employee referrals, direct contact leverages current employees specifically going after a candidate. This usually works well with senior-level staff, since they know very well what the company is looking for and they have wide professional networks. These employees seek out candidates, cultivate relationships, and bring them in as referrals when the right time comes.

- Temp-to-Hires. Another way to bring in new employees is through temporary or part-time employment first. Portals that help you find temporary and seasonal employees can all be seen as a recruiting source. Consider offering good temps and contingent employees a permanent position in your company.

- Career Fairs. Having a company presence at career fairs puts you in the center of a pool of candidates. This works better if you’re looking for candidates with a certain skill set—like software development or graphic design—as industry-specific career fairs tend to yield more potential candidates. Also consider career fairs at colleges and universities, which offer a great opportunity to reach a pool of potential entry-level candidates.

- Agency. Depending on your company’s needs, you may require the help of a recruiting agency. Recruiting agencies can be cost-effective options for finding top candidates from wider talent pools, or to find heavily sought-after candidates in more specialized industries. When considering the services of a recruiting agency, take time to weigh the pros and cons, since for some companies it’s not worth the cost.

- Newspapers. Although they’re old school, print job ads are still playing a role in the recruiting scene, especially considering the papers’ online presence. Depending on the job and the industry, more of the candidates you’re looking for may rely on print job ads when searching for openings. More so, however, is the possibility of reaching a wider audience by posting ads in the print edition and posting them on the newspaper’s website as well.

Understanding what recruiting sources are at your disposal and how to leverage them is a key first step to maximizing your talent acquisition. Which one of these sources seems to work best for your company? Have you successfully tried others?

The Definitive Guide to Recruiting and Hiring for Healthcare

This e-book will provide an overview of the best practices for staying on top of recruiting trends for hiring and retaining the best talent for your healthcare company.

I think placing job ads on social media is one of the best ways to find the candidates. Nowadays almost everyone has a profile on Facebook, LinkedIn or Google+. It’s a great way to get personal connection with applicants and get to know them prior to having a job interview.

Very useful article! I think all the sources are good and it pretty much depends on company’s needs which source is to use at a certain moment. No doubt that it’s necessary to place a job ad on the company’s website, so that the people will be able to see what current positions a company has. Recruiting agencies can be very helpful in finding job candidates as well.

Social Media is my first choice when it comes to jobs ads. As Alan said, almost everyone has a profile on a social media platform and nowadays people are really active on these platforms. Employee referrals are a suitable choice too and if your company is looking for some interns or students, career fairs are a great opportunity to make your company more visible among them.

- Assessments

- Call Center

- Client Stories

- Customer Service

- Data Entry Testing

- Employee Relations

- Employment Assessments

- Engineering

- Featured Posts

- Government / Public sector

- Hiring Assessments

- Hospitality

- Job Skills Tests

- Leadership Skills

- Manufacturing

- Pre-Employment Tests

- Pre-Hire Assessments

- Remote Hiring

- Sales Aptitude Tests

- Skill Tests

- Soft Skills Assessment

- Software Development

- Strategic Workforce

- Team Scoring

- Transportation & Logistics

- Uncategorized

- Video Interviews

Subscribe to Our Blog

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Country * Country USA UK Canada -------------------- Afghanistan Albania Algeria American Samoa Andorra Angola Antigua and Barbuda Argentina Armenia Australia Austria Azerbaijan Bahamas Bahrain Bangladesh Barbados Belarus Belgium Belize Benin Bermuda Bhutan Bolivia Bosnia and Herzegovina Botswana Brazil Brunei Bulgaria Burkina Faso Burundi Cambodia Cameroon Cape Verde Central African Republic Chad Chile China Colombia Comoros Democratic Republic of the Congo Republic of the Congo Costa Rica Côte d'Ivoire Croatia Cuba Cyprus Czech Republic Denmark Djibouti Dominica Dominican Republic East Timor Ecuador Egypt El Salvador Equatorial Guinea Eritrea Estonia Ethiopia Fiji Finland France Gabon Gambia Georgia Germany Ghana Greece Greenland Grenada Guam Guatemala Guinea Guinea-Bissau Guyana Haiti Honduras Hong Kong Hungary Iceland India Indonesia Iran Iraq Ireland Israel Italy Jamaica Japan Jordan Kazakhstan Kenya Kiribati North Korea South Korea Kuwait Kyrgyzstan Laos Latvia Lebanon Lesotho Liberia Libya Liechtenstein Lithuania Luxembourg Macedonia Madagascar Malawi Malaysia Maldives Mali Malta Marshall Islands Mauritania Mauritius Mexico Micronesia Moldova Monaco Mongolia Montenegro Morocco Mozambique Myanmar Namibia Nauru Nepal Netherlands New Zealand Nicaragua Niger Nigeria Norway Northern Mariana Islands Oman Pakistan Palau Palestine Panama Papua New Guinea Paraguay Peru Philippines Poland Portugal Puerto Rico Qatar Romania Russia Rwanda Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Samoa San Marino Sao Tome and Principe Saudi Arabia Senegal Serbia and Montenegro Seychelles Sierra Leone Singapore Slovakia Slovenia Solomon Islands Somalia South Africa Spain Sri Lanka Sudan Sudan, South Suriname Swaziland Sweden Switzerland Syria Taiwan Tajikistan Tanzania Thailand Togo Tonga Trinidad and Tobago Tunisia Turkey Turkmenistan Tuvalu Uganda Ukraine United Arab Emirates Uruguay Uzbekistan Vanuatu Vatican City Venezuela Vietnam Virgin Islands, British Virgin Islands, U.S. Yemen Zambia Zimbabwe

- State * State Alabama Alaska Arizona Arkansas California Colorado Connecticut Delaware District of Columbia Florida Georgia Hawaii Idaho Illinois Indiana Iowa Kansas Kentucky Louisiana Maine Maryland Massachusetts Michigan Minnesota Mississippi Missouri Montana Nebraska Nevada New Hampshire New Jersey New Mexico New York North Carolina North Dakota Ohio Oklahoma Oregon Pennsylvania Rhode Island South Carolina South Dakota Tennessee Texas Utah Vermont Virginia Washington West Virginia Wisconsin Wyoming Armed Forces Americas Armed Forces Europe Armed Forces Pacific

- Yes, I would like to receive marketing communications from eSkill. I can unsubscribe anytime.

By registering, you confirm that you agree to the storing and processing of your personal data by eSkill as described in the Privacy Policy

- Hidden eSkill_Form__c

Latest Posts

- From Shop Floor to C-Suite: Building a Strong Pipeline of Manufacturing Leadership Skills April 30, 2024

- The Employer’s Guide to Developing a Skilled Manufacturing Workforce April 30, 2024

- Bridging the Skills Gap: How to Attract and Retain Top Talent in Manufacturing April 30, 2024

- The Role of Aptitude Tests for Jobs in Identifying Top Talent and Improving Job Fit April 30, 2024

- Leadership Skills Test 101 for Employers: Discovering Your Organization’s Future Leaders April 30, 2024

Stay Social

Subscribe to our newsletter for updates.

- Hidden State State

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

6.9: Introduction to the Recruitment Process

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 47046

- Nina Burokas

- Lumen Learning

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

What you’ll learn to do: Discuss the recruitment process

The essence of recruiting is expressed in researcher, advisor and bestselling author Jim Collin’s classic recommendation: “get the right people on the bus.” This analogy, presented in his 2001 bestseller Good to Great , reflects the realities of operating in a dynamic and disruptive environment. [1] In the years since, this insight has been widely recognized as a critical business success factor. Recent economic, labor and technological trends have only increased the stakes. In this section, we’ll discuss the recruitment process and the importance of employer branding.

- Collins, Jim. Good to Great. New York, New York: Harper Collins, 2001. ↵

Contributors and Attributions

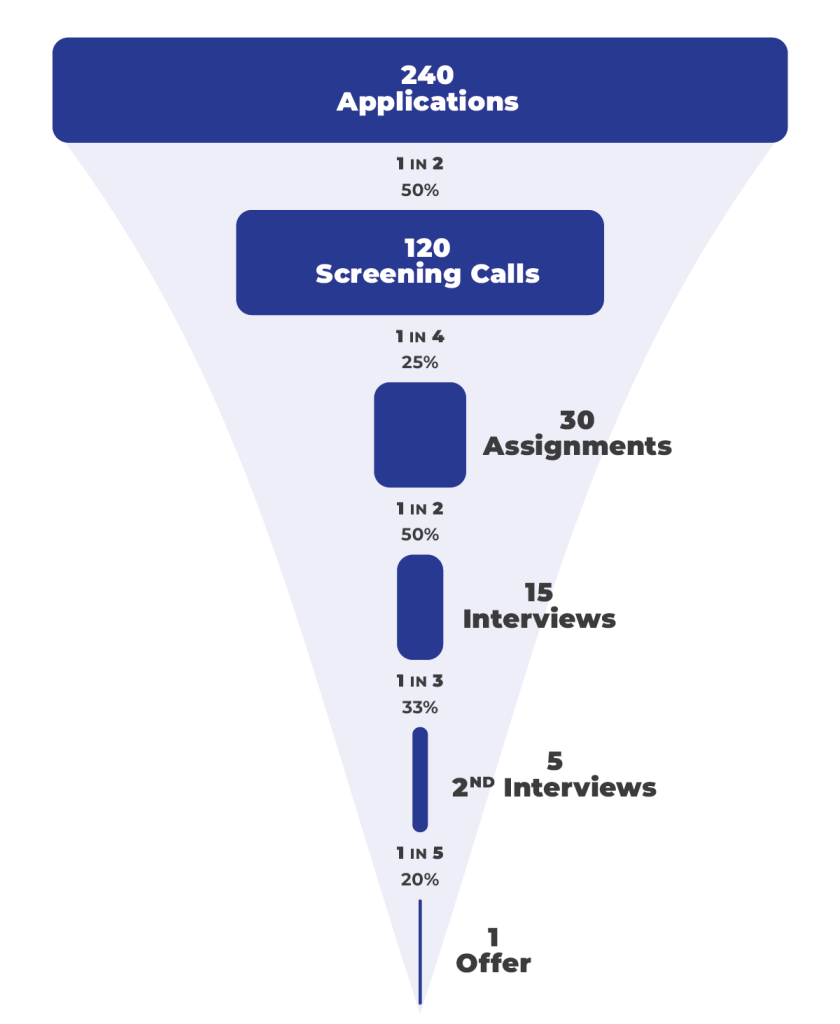

Harnessing internal and external sources of recruitment

Planning your recruitment strategy can be a daunting task in today’s competitive talent environment.Knowing where to look, which sources of recruitment to use, how to structure your job ads , and how to move your candidates through the funnel are all essential skills that you need to land your perfect hire.Fortunately, with a bit of research and even more strategic planning, you can create a recruitment system to find, screen, and hire the right talent for your organization that’s repeatable and profitable for your company.One of the first steps in this strategic planning process is to understand which recruitment sources are available to you and how to harness them as part of your overall recruitment strategy. In this article, I’ll discuss the two main sources of recruitment: internal and external .

Before we get started, you should note that no single recruitment source will necessarily be the solution to all of your recruitment problems. You should be looking at several recruitment sources to broaden your search area and get your job postings in front of as many qualified candidates as possible.

What are internal sources of recruitment?

These recruitment sources involve motivating employees within your organization to apply for vacant job postings in the company.Think of this as a promotion or lateral movement motivator for your employees. Typically, vacant job postings would be communicated to your colleagues via internal job boards, word of mouth, intranets or wikis, or any other communication channels your team uses.

Advantages of internal sources of recruitment

- Motivating skilled employees in your company with the promise of upward growth.

- Reducing employee turnover .

- Reducing recruitment and training costs.

- Guaranteeing that your vacant positions are filled with candidates who fit and understand your company culture .

- Improving overall job satisfaction and morale within your team.

- Encourages self-development of existing employees.

- Promotes training and development .

Showing your candidates that you’re willing to promote and move them into roles that will help further their careers demonstrates your commitment to them and their goals. It also means that you fill your vacancies with qualified and pre-screened candidates.

Disadvantages of internal sources of recruitment

- Less chance of new ideas and alternative solutions being introduced to existing operations and issues.

- Better quality external candidates may be overlooked.

- Promoted employees may not always hold the best qualities for their new role.

- Limiting the acquisition of fresh talent may hamper business growth.

- Less choice from a limited resource pool.

- Encourages favoritism and nepotism.

Another issue to consider with internal recruitment sources, however, is the potential tendency toward confirmation bias. Or, simply put, fewer outside voices introduced into your company to shake things up and move the dial.It’s always a good idea to take a hard look at the requirements for each job vacancy you have and, together with the hiring manager, determine if an internal or external candidate is the ideal solution.

Examples of internal sources of recruitment

Now that we’ve talked about what internal sources are and why you should use them let’s look at a selection of examples. Here’s a list of some of the most common types of internal recruitment sources you can consider for your recruitment strategy.

- Employees can be moved laterally within your organization into similar jobs or vacancies that complement their skill set. With or without a salary change, it’s a great way to re-structure your team while also reducing boredom and stagnation among your employees.

- Vacancies can be filled by promoting your most skilled employees into more senior roles. This is a great way to motivate employees, reduce turnover, and show a commitment to career growth.

- Employee referrals . Encourage your employees to refer family, friends or former co-workers who they think would be perfect for your vacant positions. This helps find qualified and vetted candidates who often have a higher likelihood to fit seamlessly into your team and culture.

Internal sources of recruitment are a fantastic way to harness the best assets you already have at your disposal: your employees. Couple these internal sources with external ones, and you’ve got yourself a robust and well-rounded recruitment strategy.

What are external sources of recruitment?

If internal recruitment sources refer to all potential candidates within your organization, then it makes sense that external recruitment sources all about motivating candidates outside of your company to apply.This is your typical candidate fishing expedition, and there are many ways to lure and catch an ideal applicant. You just need to find and deploy the right combination of external sources of recruitment.

Advantages of external sources of recruitment

- Providing a larger and more diverse pool of candidates.

- Bringing new ideas and skills into the organization.

- Promoting your employer brand and culture.

- Filling your talent pipeline with candidates for future consideration.

- Less chance of favoritism and disrupting healthy workplace atmosphere.

Disadvantages of external sources of recruitment

- Jealousy and frustration of existing employees looking for promotion .

- Lengthy and costly process.

- Finding a suitable applicant isn’t guaranteed.

- Longer periods of adjustment to a new role and organization.

- Possibilities of mismatching and choosing the wrong candidates.

Before deploying external recruitment techniques, however, it’s important that you do your homework into who your candidate is, where they’re searching for jobs, and what they’re looking for.Be sure to tailor any external sources of recruitment to a well-thought-out strategy to ensure that you’re not inundated with hundreds of unqualified candidates.Depending on the strategy, external recruitment can be a time consuming and expensive endeavor, so you want to make sure your investment will yield positive results.

Examples of external sources of recruitment

You’re likely already familiar with many external recruitment sources – these are some of the most common techniques recruiters use to find candidates. To get you thinking, here’s a list of some of the most common external sources in use today.

- Online job boards. Self-explanatory. Think of websites or any other page that lists job posting. These can either be free or paid, targeted or broad. Find out where your ideal candidates typically search for jobs and get your ads posted.

- These are similar to job board postings but are broader and don’t necessarily need to be online. Think of all the websites, newspapers, magazines, and even physical places your candidates likely visit on a daily basis and post some appealing job ads. These are typically paid placements, but the right location can yield great results if targeted properly.

- Applicant Tracking Systems (ATS) or other recruitment software . Take a deep dive into the candidate pools you’ve collected from previous search efforts to see if there are any qualified applicants you can reach out to. Use an ATS like Recruitee to search for specific parameters to narrow down your efforts.

- Educational institutions. Makes connections with universities, colleges, and trade schools and invite new graduates into your company for internship positions. These are great future high performers that you can scoop up early in their careers.

- Trade associations, conferencing, and network events. Where industries hold particular professional or trade associations, accessing a database of members could open a host of new potential hires. Trade magazines and journals are also options as fresh job role advertising opportunities. These areas are ideally placed for locating experienced and skilled candidates.

- Former employees. Don’t be afraid of rebound or boomerang employees . In today’s job market, it’s very common for people to jump from company to company to progress through their career. If you have a vacancy that might appeal to a former colleague, reach out to them to see if they’re ready to make a comeback.

- Previous applicants. A database of previously unsuccessful candidates delivers a resource pool of possible options. If they failed to win the role purely because another candidate held better qualities or credentials, they could still be perfectly suitable to fill the position.

- Rival businesses. Some of the best operatives in your industry will be working for your competitors. They might not be looking to relocate or for a better opportunity, but you won’t know unless you ask. Just because they’re not actively looking for a new challenge doesn’t mean they’re not ready for one.

- Social media. LinkedIn is a no-brainer for recruiters. Search for candidates based on job title, skill set, and location to find high potential candidates and reach out to them via InMail. Don’t be afraid to search Twitter and Facebook for industry-relevant pages and groups that you can reach out to as well.

As mentioned earlier in this article, no one source of recruitment will be the solution to all of your problems. Instead, take some time to strategically plan your recruitment process, know your candidate and deploy the sources that will yield the best bang for your effort and buck.

Brendan is an established writer, content marketer and SEO manager with extensive experience writing about HR tech, information visualization, mind mapping, and all things B2B and SaaS. As a former journalist, he's always looking for new topics and industries to write about and explore.

Get the MidWeekRead

Get the exclusive tips, resources and updates to help you hire better!

Hire better, faster, together!

Bring your hiring teams together, boost your sourcing, automate your hiring, and evaluate candidates effectively.

How to Source Candidates: A Must-Read Guide for Recruiters

Candidate sourcing is a strategic approach to identifying and engaging potential candidates. Here, we will explore the fundamentals of candidate sourcing, effective methods, and how to tailor your approach for different levels and positions.

What Is Candidate Sourcing?

Effective ways to source candidates, an overview of sourcing stats, how to source candidates (step-by-step guide), how do i source entry-level candidates, how do i source mid-level candidates, how do i source top-level candidates, how do i source executive-level candidates, do’s and don’ts of talent sourcing.

- Difference between Sourcing and Recruiting

Candidate sourcing is a proactive approach to identifying, attracting, and engaging potential candidates for positions within a company. It involves actively searching for individuals with the desired skills, experience, and qualifications, even if they are not actively seeking new employment opportunities.

Candidate sourcing aims to build a talent pool of qualified candidates for current or future job openings, ensuring a continuous flow of suitable candidates for the organization’s growth and success. This approach allows recruiters and hiring managers to connect with top-notch talent and establish relationships early on, increasing the likelihood of successful hires.

When sourcing candidates for job openings, effective strategies are crucial to attract the right talent. Here are some proven methods that recruiters and hiring managers can use to enhance their candidate sourcing efforts.

- Utilize online job boards

- Leverage social media platforms

- Engage with professional networks

- Attend career fairs and events

- Explore referrals from employees

- Implement targeted advertising

For a comprehensive talent sourcing strategy, visit [Talent Sourcing Strategy].

Understanding candidate sourcing through relevant statistics provides valuable insights for recruiters and hiring professionals. These numbers shed light on trends, behaviors, and patterns, helping formulate effective sourcing strategies. Here’s an overview of some key sourcing statistics.

Percentage of hires sourced through social media

A significant percentage of hires, approximately 70%, are sourced through various social media platforms. Recruiters actively engage with potential candidates on platforms like LinkedIn, Facebook, and X (formerly Twitter) to connect and share job opportunities.

Percentage of hires through employee referrals

Employee referrals are a highly effective sourcing method, contributing to about 30-50% of successful hires. Leveraging existing employees’ networks helps find candidates who align well with the organizational culture.

Average time to source a candidate

On average, it takes about 10 days to successfully source a candidate for a job role. Efficient sourcing processes and effective use of sourcing methods play a role in minimizing the time taken to identify suitable candidates.

Effectively sourcing candidates requires a structured process that involves several steps to identify, attract, and engage potential talent. Here’s a step-by-step guide to successfully sourcing candidates.

Understand your requirements

Begin by thoroughly understanding the job role and its requirements. Consult with the hiring team to clarify the skills, qualifications, experience, and attributes needed for the position.

Create targeted job descriptions

Craft compelling, detailed job descriptions accurately reflecting the job role and expectations. Clearly articulate the position’s responsibilities, qualifications, and benefits to attract the right candidates.

Use advanced search techniques

Employ advanced search functionalities on job portals, professional networking platforms, and applicant tracking systems (ATS). Utilize filters to narrow down the candidate pool based on specific criteria such as skills, location, experience, and education.

Engage and build relationships

Reach out to potential candidates and engage them in meaningful conversations. Introduce your organization and highlight its values, culture, and growth opportunities. Establish a positive rapport to build trust and interest.

Assess and shortlist candidates

Evaluate candidates based on their alignment with the job requirements. Consider their skills, experience, cultural fit, and enthusiasm for the role. Shortlist the most suitable candidates for further evaluation.

Conduct interviews and assessments

Arrange interviews to assess the shortlisted candidates in-depth. Conduct both technical and behavioral interviews to evaluate their capabilities, problem-solving skills, and cultural alignment. Additionally, consider using assessments to gauge specific skills.

Communicate and offer

Maintain transparent communication with the candidates throughout the process. Provide timely updates on their application status and feedback. Extend job offers to selected candidates and negotiate terms if needed.

Sourcing entry-level candidates involves targeting individuals typically new to the job market or with minimal work experience. Here are effective strategies to source entry-level candidates.

College and university partnerships

Collaborate with colleges and universities to attend career fairs, host informational sessions, or participate in campus recruiting events. Engage with students nearing graduation who are seeking entry-level opportunities.

Internship programs

Establish internship programs within your organization. Internships serve as a direct pipeline for identifying and nurturing potential entry-level talent. Offer internships to students or recent graduates to evaluate their skills and fit within the company.

Job postings on career websites

Utilize online job boards and career websites that specifically cater to entry-level positions. Post detailed job descriptions and requirements to attract recent graduates or individuals looking to start their careers.

Utilize social media

Leverage social media platforms like LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram to showcase your organization and entry-level job opportunities. Engage with relevant groups or communities to reach a broader audience of potential candidates.

Networking events and meetups

Attend industry-related networking events, career fairs, or professional meetups where entry-level job seekers may be present. Actively engage with attendees and share information about job openings within your organization.

Referrals and employee advocacy

Encourage your current employees to refer suitable candidates for entry-level positions. Offer referral incentives to motivate employees to recommend qualified individuals from their networks.

Community involvement

Get involved in community events, workshops, or volunteering opportunities. Engage with individuals eager to kick-start their careers and seek guidance or job openings.

Local job centers and organizations

Collaborate with local job centers, career counseling offices, or youth employment organizations. These entities often assist entry-level job seekers in finding suitable opportunities.

Career development webinars or seminars

Organize webinars or seminars focused on career development and invite entry-level candidates to participate. Share insights into your industry, organization, and potential career growth within your company.

Utilize alumni networks

Reach out to your organization’s alumni network or university alumni associations. Alumni may be seeking entry-level opportunities and could already possess the necessary education and skills.

Sourcing mid-level candidates involves targeting professionals with a few years of experience in their respective fields. Here are effective strategies to source mid-level candidates.

Job boards and career websites

Post job openings on specialized job boards and career websites that cater to mid-level positions. Ensure the job description highlights the level of experience and skills required.

Professional networking platforms

Utilize platforms like LinkedIn to connect with professionals with mid-level experience. Join industry-specific groups, participate in discussions, and directly reach out to potential candidates.

Industry-specific events and conferences

Attend conferences, seminars, and industry events related to your field. Engage with attendees and speakers with a few years of experience and may be looking to progress in their careers.

Utilize recruitment agencies

Partner with recruitment agencies that specialize in mid-level placements. They often have a pool of pre-screened candidates with the desired experience.

Referrals from employees

Encourage your current employees to refer mid-level professionals from their professional networks. Offer referral incentives to motivate employees to recommend qualified candidates.

Professional associations

Engage with industry-specific professional associations and societies. Many mid-level professionals are active members and attend events organized by these groups.

Alumni networks

Leverage your organization’s alumni network or alumni associations from universities. Mid-level professionals may join these networks and be interested in opportunities within your company.

Networking events

Attend networking events within your industry or related fields. These events provide an excellent platform for meeting mid-level professionals seeking new opportunities.

Headhunting and executive search firms

Collaborate with headhunters or executive search firms that specialize in mid-level placements. They have access to a network of potential candidates.

Promote job openings and company culture on social media platforms. Tailor your content to attract mid-level professionals and encourage them to apply.

Company website careers page

Ensure your company’s careers page on the website is up to date with mid-level job openings. Include detailed job descriptions and requirements to attract suitable candidates.

Sourcing top-level candidates, often in executive or leadership positions, requires a strategic and targeted approach. Here are effective strategies to source top-level candidates.

Executive search firms

Partner with specialized executive search firms with a strong network and expertise in recruiting top-level executives. These firms have access to a vast pool of high-caliber candidates.

Networking within industry events

Attend industry-specific events, conferences, and seminars where top-level professionals will likely participate. Engage in meaningful conversations and establish relationships with potential candidates.

Professional associations and organizations

Collaborate with prestigious professional associations and organizations relevant to your industry. These groups often have a membership base consisting of senior-level professionals.

LinkedIn executive search

Utilize LinkedIn’s advanced search features to identify and reach out to potential top-level candidates based on specific criteria such as industry, job title, and experience.

Industry publications and journals

Advertise job openings and opportunities in industry-specific publications, journals, or websites that top-level professionals widely read.

Alumni networks of elite universities

Tap into the alumni networks of renowned universities and institutions. Top-level professionals often maintain connections with their alma mater and could be open to new opportunities.

Collaboration with industry experts

Collaborate with well-known industry experts, consultants, or advisors with an extensive network. Seek their recommendations or introductions to top-level candidates.

Board and director networks

Engage with board and director networks that connect executives with organizations seeking board members or executives for top-level positions.

Executive development programs

Participate in or collaborate with executive development programs or workshops. These events often attract senior-level professionals looking to enhance their skills and network.

Industry thought leadership platforms

Establish a presence on thought leadership platforms and contribute insightful content. This can attract top-level professionals seeking to engage with innovative and forward-thinking organizations.

Targeted online job portals

Post job openings on specialized online job portals that focus on executive positions. Ensure the job descriptions are compelling and accurately reflect the seniority and expectations of the role.

Search within competing companies

Identify and approach professionals in competing or similar companies who may be looking for new challenges or career advancements.

Sourcing executive-level candidates who are leaders and decision-makers within an organization necessitates a targeted and strategic approach. Here are effective strategies to source executive-level candidates.

Collaborate with specialized executive search firms that focus on identifying and recruiting executives. These firms have a vast network and expertise in finding suitable executive candidates.

Industry networking events

Attend industry-specific networking events, conferences, and seminars where executives will likely be present. Engage in meaningful conversations and establish relationships with potential candidates.

Networking within professional associations

Engage with executive-level professionals through membership in professional associations related to your industry. These associations often organize events that facilitate networking with executives.

Utilize LinkedIn’s advanced search features to identify and connect with potential executive-level candidates based on specific criteria such as job title, industry, and experience.

Industry conclaves and roundtables

Participate in exclusive industry conclaves, roundtables, or invite-only events where top executives congregate. These events provide a platform to connect with potential executive talent.

Alumni networks of prestigious universities

Leverage the alumni networks of prestigious universities and institutions that produce top-notch executives. Engage with alumni who may be seeking new executive opportunities.

Collaboration with industry experts and consultants

Collaborate with industry experts, consultants, or advisors with a wide network of executive-level professionals. Seek their recommendations or introductions to potential executive candidates.

Board director networks

Engage with networks or associations focused on board members and directors. Many executive candidates are interested in board positions and have connections within such networks.

Executive education programs and workshops

Explore collaboration with executive education programs and workshops where senior executives often seek continuous learning and networking opportunities.

Targeted job portals for executives

Post executive-level job openings on specialized online job portals dedicated to senior positions. Ensure the job descriptions align with the expectations and seniority of the role.

Headhunting and talent acquisition teams

Build or collaborate with an in-house headhunting or talent acquisition team dedicated to sourcing executive talent. These teams can proactively search for and approach potential candidates.

Identify and approach executives from competing or similar companies who may be open to exploring new challenges and opportunities.

Here’s a guide outlining the do’s and don’ts to ensure an effective and ethical talent sourcing process.

Maintain professionalism

Conduct all interactions with candidates professionally and respectfully, regardless of the outcome. Uphold the organization’s reputation throughout the sourcing process.

Clearly communicate job expectations

Provide candidates with a clear understanding of the job role, responsibilities, qualifications required, and organizational culture. Transparency helps in aligning expectations.

Regularly update candidates

Keep candidates informed of their application status and the progress of the recruitment process. Timely communication reflects positively on the organization.

Leverage employee referrals

Encourage and incentivize employees to refer potential candidates. Employee referrals often yield high-quality candidates who align with the company culture.

Personalize communication

Tailor communication to each candidate, addressing their skills and experiences. Personalization shows genuine interest and enhances engagement.

Provide constructive feedback

Offer constructive feedback to candidates, especially if they are not selected. This helps candidates understand areas for improvement and fosters a positive perception of the organization.

Build a talent pipeline

Continuously engage with potential candidates, even if there are no immediate job openings. Build a talent pipeline for future opportunities within the organization.

Don’ts

Send mass emails

Refrain from sending generic, mass emails to potential candidates. Personalize communications to show genuine interest and relevance to the candidate.

Oversell the role

Avoid exaggerating the job role, organizational benefits, or growth prospects to attract candidates. Be honest and transparent in presenting the opportunities.

Skip due diligence

Make sure to complete essential background checks and verification of candidate credentials. Thorough due diligence ensures the credibility and suitability of candidates.

Neglect candidate experience

Don’t overlook the candidate’s experience during the recruitment process. A negative experience can tarnish the organization’s reputation and deter potential candidates.

Postpone feedback

Avoid delaying feedback to candidates after interviews or assessments. Prompt feedback demonstrates professionalism and respect for candidates’ time and efforts.

Difference Between Sourcing and Recruiting

Sourcing and recruiting are both crucial components of the talent acquisition process , each with distinct roles and functions. Understanding the differences between the two can aid in optimizing the hiring process. Here’s a concise comparison.

Understanding the distinction between sourcing and recruiting is essential for an effective hiring process. Check out [Talent Sourcing vs. Recruiting] for an insightful comparison.

Candidate sourcing is an art and a science. The right strategies and methods can significantly impact your organization’s ability to attract the best talent. The process involves intricate steps from sourcing to recruiting, aiming to identify and attract the best-fit candidates for various job roles.

Maintaining professionalism, clear communication, and utilizing technology are essential to a successful talent acquisition process. Furthermore, understanding the difference between sourcing and recruiting helps structure and optimize the hiring process.

In a job market that is always changing, keeping up with these methods and trends will help you understand how to source candidates in a way that will help your team grow.

This is where Joveo comes in to get your job ads in front of the right people – at the right place and time, for the right price! With our AI-driven approach and campaign automation, you can spend with precision on sources that deliver.

Discover the power of our game-changing, end-to-end talent-sourcing platform.

See us in action to boost your company’s productivity. Follow us on Twitter and LinkedIn for more hiring insights!

What are common sourcing methods?

Sourcing methods encompass various strategies to identify and engage potential candidates for job roles. Common methods include leveraging online job boards, social media platforms, employee referrals, industry events, career fairs, and collaborations with educational institutions. Each method has its own advantages and is tailored based on the organization’s hiring needs.

What are candidate sourcing tools?

Candidate sourcing tools are software or platforms designed to aid recruiters in identifying and engaging potential candidates efficiently. These tools automate candidate search, provide access to candidate databases, offer advanced search filters, and sometimes integrate with applicant tracking systems (ATS). Examples include LinkedIn Recruiter, Indeed, Glassdoor, and specialized sourcing software.

What is the most effective place to source candidates?

The most effective source of candidates often varies based on the industry, job role, and organization. However, employee referrals consistently rank among the most effective sources of candidates. Referrals tend to bring in candidates who align with the company culture and values. Social media platforms and specialized job boards also prove highly effective in candidate sourcing.

What is the process of finding candidates?

The process of finding candidates involves several key steps.

- Identify needs: Understanding the job requirements and creating a clear job description.

- Sourcing: Actively searching for potential candidates using online platforms, referrals, and networking.

- Engagement: Contacting and engaging with potential candidates to gauge their interest and suitability for the role.

- Evaluation: Assessing candidates through interviews, assessments, and background checks.

- Selection: Choosing the best-fit candidates and extending job offers.

- Onboarding: Integrating the selected candidates into the organization smoothly to begin their roles effectively.

Get the latest posts in your email

Related posts, recruitment market research: shaping the future of effective talent acquisition, harnessing the power of resume parsing for smarter hiring decisions, hiring in a heartbeat: 17 nurse recruitment strategies for success, recent articles, 10 innovative strategies to differentiate your candidate experience and attract top talent, 6 strategies for integrating candidate feedback into email communications, leading the future: top 8 ai-focused in-person conferences for talent acquisition pros, source smarter. hire faster. spend less..

- MOJO Pro: Programmatic Job Advertising

- MOJO Social: Social, Search, and Display Advertising

- MOJO CraigGenie: Craigslist Automation

- MOJO Career Site and CMS: Personalized, Dynamic Career Sites

- MOJO Apply: Job Application Optimization

- MOJO Engage CRM: Simple, High-Engagement CRM

- MOJO Go: Optimized Multi-Posting

- MOJO Unified Analytics: Actionable Insights

- Can’t Measure Employer Branding ROI

- Not Enough Great-Fit Applicants

- High Cost Per Hire

- Missing Passive Candidates

- High Application Drop Off

- Lagging on DE&I Sourcing

- Don’t Know Where You Stand

- Too Many Platforms, Too Much Info

- Global Partner Program

- Security and Compliance

Exclusive Insights: Free Report on the State of Recruitment in US Healthcare | Download Now →

Cookie Disclaimer

Privacy overview.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

11 Strategic Recruitment: A Multilevel Perspective

Stanley M. Gully, School of Management and Labor Relations, Rutgers University

Jean M. Phillips, School of Management and Labor Relations, Rutgers University

Mee Sook Kim, Rutgers University

- Published: 16 December 2013

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter examines recruitment practices through a strategic lens. To be strategic, recruitment must be integrated with other human resource management practices (horizontal alignment) as well as with the goals and strategic objectives of the firm (vertical alignment). Recruitment activities are integrated into a complex system of strategies, policies, practices, and activities that permeate all organizational levels. Understanding strategic recruitment thus requires the incorporation of strategic human resource management perspectives as well as an appreciation of levels of analysis issues. The chapter begins by reviewing the concepts of core competence, sustained competitive advantage, and the resource-based view. This foundation is used to interpret research and theory relevant to strategic recruitment. It then uses a multilevel model of strategic recruitment to examine the body of previous recruiting research to identify opportunities for future research directions. The chapter provides a number of testable propositions and suggests new directions for strategic recruitment research.

Introduction

Effective recruiting is a cornerstone of strategic human resource management systems and strategic execution. Because strategic execution relies on people to transform a strategy from an idea into real changes in services, products, markets, technologies, and prices, firms must hire people who fit the culture and have the right mix of skills to generate sustainable competitive advantage. However, if potentially strong employees are not effectively recruited then they can never be hired. And if they aren’t hired, they can’t be developed, evaluated, compensated, or motivated. Stated simply, you cannot select and manage talented employees through human resource management (HRM) systems if you do not first recruit them.

Background and Introduction

Research on recruitment in general has exploded in the last forty years, Breaugh and Starke (2000) note that the 1976 edition of the Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology contained less than one page of recruitment coverage ( Guion, 1976 ), but fifteen years later an entire chapter of the Handbook was devoted to recruitment research ( Rynes, 1991 ). A keyword search of the literature also suggests increasing research interest. Table 11.1 shows the number of times the words “recruiting, recruitment, or recruiter” were mentioned in the PsychInfo index among the top journals in management and applied psychology. References to recruiting related topics have increased dramatically since the 1970s, increasing in a nonlinear fashion.

Since the 1970s, many books (e.g., Barber, 1998 ; Breaugh, 1992 ) and research reviews have been written on recruitment related topics (e.g., Breaugh, 2012 ; Breaugh, Macan, & Grambow, 2008 ; Breaugh & Starke, 2000 ; Dineen & Soltis, 2011 ; Olian & Rynes, 1984 ; Orlitzky, 2007 ; Ryan & Delany, 2010 ; Rynes & Cable, 2003 ; Yu & Cable, 2012 ). It would be impossible for us to summarize all aspects of this broad literature. We refer interested readers to the original sources and other chapters within this handbook for quality summaries. Here we specifically address recruitment research with a strategic focus. This requires incorporation of work that falls outside the bounds of traditional recruitment research.

There is a relative dearth of recruitment research in the strategic arena. For example, a meta-analysis on high-performance work systems found fewer than five effect sizes that related any type of recruitment measure to firm level performance ( Combs, Liu, Hall, & Ketchen, 2006 ). With the exception of some key papers that have focused on the connection between recruitment and organizational level strategies (e.g., Miles & Snow, 1984 ; Olian & Rynes, 1984 ; Rynes & Barber, 1990 ), most work has concentrated on specific recruitment practices such as realistic job previews ( Phillips, 1998 ), recruitment messages ( Roberson, Collins, & Oreg, 2005 ), or job advertisement content ( Feldman, Bearden, & Hardesty, 2006 ). This is useful for building our understanding about determinants of recruitment effectiveness but it doesn’t provide a strategic and integrated perspective on recruitment.

We begin by examining what is meant by strategic recruitment. Breaugh et al. (2008) built on definitions from Barber (1998) and Ployhart (2006) to suggest that recruitment involves “…organizational actions that are intended to: (a) bring a job opening to the attention of potential job candidates; (b) influence whether these individuals apply for the opening; (c) affect whether recruits maintain interest in the position until a job offer is extended; and (d) influence whether a job offer is accepted and the person joins the organization” (pp. 45–46). Recruitment activities can also play the role of helping people who may be a poor fit to self-select out of the recruitment and selection process ( Allen & Bryant, 2012 ).

We suggest that strategic recruitment is consistent with all of these activities. How, then, is strategic recruitment different from recruitment as it is more traditionally defined? Strategy reflects an enterprise’s long-term goals and the adoption of courses of actions and allocation of resources necessary to meet these goals ( Chandler, 1962 ). Attaching the modifier “strategic” often implies firm level strategies, firm performance, and integrated HRM systems. However, HRM practices can be “strategic” across functions and levels. Accordingly, strategic execution can be overlaid as an integration of systems and processes across micro, meso, and macro levels of analysis ( Arthur & Boyles, 2007 ; Huselid & Becker, 2011 ; Molloy, Ployhart, & Wright, 2011 ; Ployhart & Moliterno, 2011 ; Wright & Boswell, 2002 ). Rather than focusing only on firm level HRM practices as the defining characteristic of strategic execution, it is useful to think of strategic recruitment as connecting practices across levels of analysis that must be carefully aligned with the goals, strategies, and characteristics of the specific firm.

Level of analysis refers to a plane of interest in a hierarchy of systems ( Rousseau, 1985 ). Employees work in teams, business units, and organizations. Characteristics and processes that exist at one level can drive systems, processes, and outcomes at another level ( Klein, Dansereau, & Hall, 1994 ; Klein & Kozlowski, 2000 ). Because the effects of recruitment on outcomes may or may not generalize across levels ( Klein et al., 1994 ; Rousseau, 1985 ), we argue individual, business unit, and organizational level factors and associated systems, practices, and activities can influence how recruitment unfolds across levels.