About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets & Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Social Impact

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Services

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

- Operations, Information & Technology

- Classical Liberalism

- The Eddie Lunch

- Accounting Summer Camp

- Videos, Code & Data

- California Econometrics Conference

- California Quantitative Marketing PhD Conference

- California School Conference

- China India Insights Conference

- Homo economicus, Evolving

- Political Economics (2023–24)

- Scaling Geologic Storage of CO2 (2023–24)

- A Resilient Pacific: Building Connections, Envisioning Solutions

- Adaptation and Innovation

- Changing Climate

- Civil Society

- Climate Impact Summit

- Climate Science

- Corporate Carbon Disclosures

- Earth’s Seafloor

- Environmental Justice

- Operations and Information Technology

- Organizations

- Sustainability Reporting and Control

- Taking the Pulse of the Planet

- Urban Infrastructure

- Watershed Restoration

- Junior Faculty Workshop on Financial Regulation and Banking

- Ken Singleton Celebration

- Marketing Camp

- Quantitative Marketing PhD Alumni Conference

- Presentations

- Theory and Inference in Accounting Research

- Stanford Closer Look Series

- Quick Guides

- Core Concepts

- Journal Articles

- Glossary of Terms

- Faculty & Staff

- Researchers & Students

- Research Approach

- Charitable Giving

- Financial Health

- Government Services

- Workers & Careers

- Short Course

- Adaptive & Iterative Experimentation

- Incentive Design

- Social Sciences & Behavioral Nudges

- Bandit Experiment Application

- Conferences & Events

- Get Involved

- Reading Materials

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Energy Entrepreneurship

- Faculty & Affiliates

- SOLE Report

- Responsible Supply Chains

- Current Study Usage

- Pre-Registration Information

- Participate in a Study

A How-To Guide for Conducting Retrospective Analyses: Example COVID-19 Study

In the urgent setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, treatment hypotheses abound, each of which requires careful evaluation. A randomized controlled trial generally provides the strongest possible evaluation of a treatment, but the efficiency and effectiveness of the trial depend on the existing evidence supporting the treatment. The researcher must therefore compile a body of evidence justifying the use of time and resources to further investigate a treatment hypothesis in a trial. An observational study can help provide this evidence, but the lack of randomized exposure and the researcher’s inability to control treatment administration and data collection introduce significant challenges for non-experimental studies. A proper analysis of observational health care data thus requires an extensive background in a diverse set of topics ranging from epidemiology and causal analysis to relevant medical specialties and data sources. Here we provide 10 rules that serve as an end-to-end introduction to retrospective analyses of observational health care data. A running example of a COVID-19 study presents a practical implementation of each rule in the context of a specific treatment hypothesis. When carefully designed and properly executed, a retrospective analysis framed around these rules will inform the decisions of whether and how to investigate a treatment hypothesis in a randomized controlled trial.

- Priorities for the GSB's Future

- See the Current DEI Report

- Supporting Data

- Research & Insights

- Share Your Thoughts

- Search Fund Primer

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Business Transformation

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships and Prizes

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication

- Deferred Enrollment

- Joint & Dual Degrees

- Entering Class Profile

- Event Schedule

- Ambassadors

- New & Noteworthy

- Ask a Question

- See Why Stanford MSx

- Is MSx Right for You?

- MSx Stories

- Leadership Development

- Career Advancement

- Career Change

- How You Will Learn

- Admission Events

- Personal Information

- Information for Recommenders

- GMAT, GRE & EA

- English Proficiency Tests

- After You’re Admitted

- Daycare, Schools & Camps

- U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

- Requirements

- Requirements: Behavioral

- Requirements: Quantitative

- Requirements: Macro

- Requirements: Micro

- Annual Evaluations

- Field Examination

- Research Activities

- Research Papers

- Dissertation

- Oral Examination

- Current Students

- Education & CV

- International Applicants

- Statement of Purpose

- Reapplicants

- Application Fee Waiver

- Deadline & Decisions

- Job Market Candidates

- Academic Placements

- Stay in Touch

- Faculty Mentors

- Current Fellows

- Standard Track

- Fellowship & Benefits

- Group Enrollment

- Program Formats

- Developing a Program

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Strategic Transformation

- Program Experience

- Contact Client Services

- Campus Experience

- Live Online Experience

- Silicon Valley & Bay Area

- Digital Credentials

- Faculty Spotlights

- Participant Spotlights

- Eligibility

- International Participants

- Stanford Ignite

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Founding Donors

- Location Information

- Participant Profile

- Network Membership

- Program Impact

- Collaborators

- Entrepreneur Profiles

- Company Spotlights

- Seed Transformation Network

- Responsibilities

- Current Coaches

- How to Apply

- Meet the Consultants

- Meet the Interns

- Intern Profiles

- Collaborate

- Research Library

- News & Insights

- Program Contacts

- Databases & Datasets

- Research Guides

- Consultations

- Research Workshops

- Career Research

- Research Data Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Research Guides

- Material Loan Periods

- Fines & Other Charges

- Document Delivery

- Interlibrary Loan

- Equipment Checkout

- Print & Scan

- MBA & MSx Students

- PhD Students

- Other Stanford Students

- Faculty Assistants

- Research Assistants

- Stanford GSB Alumni

- Telling Our Story

- Staff Directory

- Site Registration

- Alumni Directory

- Alumni Email

- Privacy Settings & My Profile

- Success Stories

- The Story of Circles

- Support Women’s Circles

- Stanford Women on Boards Initiative

- Alumnae Spotlights

- Insights & Research

- Industry & Professional

- Entrepreneurial Commitment Group

- Recent Alumni

- Half-Century Club

- Fall Reunions

- Spring Reunions

- MBA 25th Reunion

- Half-Century Club Reunion

- Faculty Lectures

- Ernest C. Arbuckle Award

- Alison Elliott Exceptional Achievement Award

- ENCORE Award

- Excellence in Leadership Award

- John W. Gardner Volunteer Leadership Award

- Robert K. Jaedicke Faculty Award

- Jack McDonald Military Service Appreciation Award

- Jerry I. Porras Latino Leadership Award

- Tapestry Award

- Student & Alumni Events

- Executive Recruiters

- Interviewing

- Land the Perfect Job with LinkedIn

- Negotiating

- Elevator Pitch

- Email Best Practices

- Resumes & Cover Letters

- Self-Assessment

- Whitney Birdwell Ball

- Margaret Brooks

- Bryn Panee Burkhart

- Margaret Chan

- Ricki Frankel

- Peter Gandolfo

- Cindy W. Greig

- Natalie Guillen

- Carly Janson

- Sloan Klein

- Sherri Appel Lassila

- Stuart Meyer

- Tanisha Parrish

- Virginia Roberson

- Philippe Taieb

- Michael Takagawa

- Terra Winston

- Johanna Wise

- Debbie Wolter

- Rebecca Zucker

- Complimentary Coaching

- Changing Careers

- Work-Life Integration

- Career Breaks

- Flexible Work

- Encore Careers

- Join a Board

- D&B Hoovers

- Data Axle (ReferenceUSA)

- EBSCO Business Source

- Global Newsstream

- Market Share Reporter

- ProQuest One Business

- Student Clubs

- Entrepreneurial Students

- Stanford GSB Trust

- Alumni Community

- How to Volunteer

- Springboard Sessions

- Consulting Projects

- 2020 – 2029

- 2010 – 2019

- 2000 – 2009

- 1990 – 1999

- 1980 – 1989

- 1970 – 1979

- 1960 – 1969

- 1950 – 1959

- 1940 – 1949

- Service Areas

- ACT History

- ACT Awards Celebration

- ACT Governance Structure

- Building Leadership for ACT

- Individual Leadership Positions

- Leadership Role Overview

- Purpose of the ACT Management Board

- Contact ACT

- Business & Nonprofit Communities

- Reunion Volunteers

- Ways to Give

- Fiscal Year Report

- Business School Fund Leadership Council

- Planned Giving Options

- Planned Giving Benefits

- Planned Gifts and Reunions

- Legacy Partners

- Giving News & Stories

- Giving Deadlines

- Development Staff

- Submit Class Notes

- Class Secretaries

- Board of Directors

- Health Care

- Sustainability

- Class Takeaways

- All Else Equal: Making Better Decisions

- If/Then: Business, Leadership, Society

- Grit & Growth

- Think Fast, Talk Smart

- Spring 2022

- Spring 2021

- Autumn 2020

- Summer 2020

- Winter 2020

- In the Media

- For Journalists

- DCI Fellows

- Other Auditors

- Academic Calendar & Deadlines

- Course Materials

- Entrepreneurial Resources

- Campus Drive Grove

- Campus Drive Lawn

- CEMEX Auditorium

- King Community Court

- Seawell Family Boardroom

- Stanford GSB Bowl

- Stanford Investors Common

- Town Square

- Vidalakis Courtyard

- Vidalakis Dining Hall

- Catering Services

- Policies & Guidelines

- Reservations

- Contact Faculty Recruiting

- Lecturer Positions

- Postdoctoral Positions

- Accommodations

- CMC-Managed Interviews

- Recruiter-Managed Interviews

- Virtual Interviews

- Campus & Virtual

- Search for Candidates

- Think Globally

- Recruiting Calendar

- Recruiting Policies

- Full-Time Employment

- Summer Employment

- Entrepreneurial Summer Program

- Global Management Immersion Experience

- Social-Purpose Summer Internships

- Process Overview

- Project Types

- Client Eligibility Criteria

- Client Screening

- ACT Leadership

- Social Innovation & Nonprofit Management Resources

- Develop Your Organization’s Talent

- Centers & Initiatives

- Student Fellowships

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

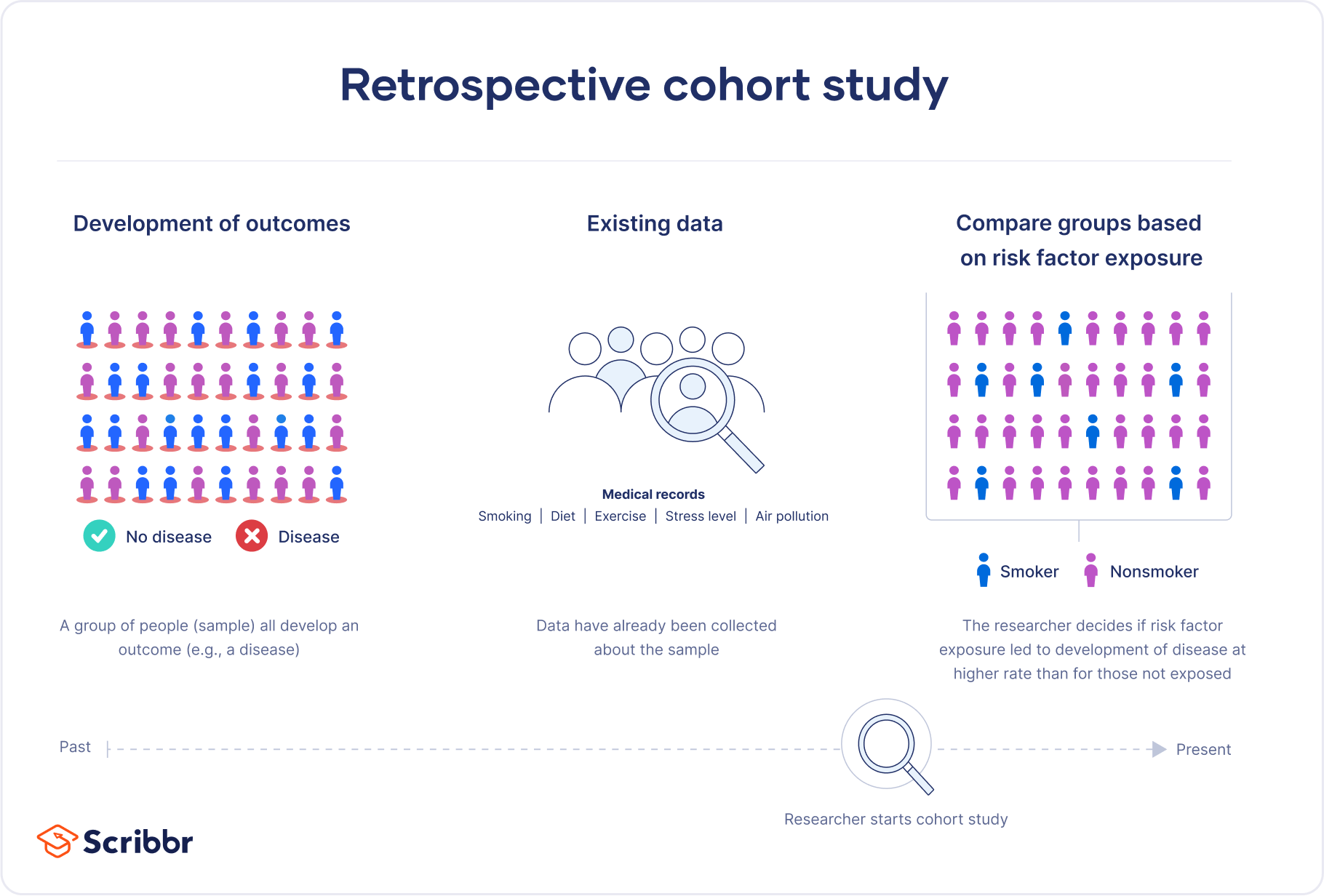

- What Is a Retrospective Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples

What Is a Retrospective Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples

Published on 10 February 2023 by Tegan George . Revised on 19 June 2023.

A retrospective cohort study is a type of observational study that focuses on individuals who have an exposure to a disease or risk factor in common. Retrospective cohort studies analyse the health outcomes over a period of time to form connections and assess the risk of a given outcome associated with a given exposure.

It is crucial to note that in order to be considered a retrospective cohort study, your participants must already possess the disease or health outcome being studied.

Table of contents

When to use a retrospective cohort study, examples of retrospective cohort studies, advantages and disadvantages of retrospective cohort studies, frequently asked questions.

Retrospective cohort studies are a type of observational study . They are often used in fields related to medicine to study the effect of exposures on health outcomes. While most observational studies are qualitative in nature, retrospective cohort studies are often quantitative , as they use preexisting secondary research data. They can be used to conduct both exploratoy research and explanatory research .

Retrospective cohort studies are often used as an intermediate step between a weaker preliminary study and a prospective cohort study , as the results gleaned from a retrospective cohort study strengthen assumptions behind a future prospective cohort study.

A retrospective cohort study could be a good fit for your research if:

- A prospective cohort study is not (yet) feasible for the variables you are investigating.

- You need to quickly examine the effect of an exposure, outbreak, or treatment on an outcome.

- You are seeking to investigate an early-stage or potential association between your variables of interest.

Retrospective cohort studies use secondary research data, such as existing medical records or databases, to identify a group of people with an exposure or risk factor in common. They then observe their health outcomes over time. Case-control studies rely on primary research , comparing a group of participants with a condition of interest to a group lacking that condition in real time.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Retrospective cohort studies are common in fields like medicine, epidemiology, and healthcare.

You collect data from participants’ exposure to organophosphates, focusing on variables like the timing and duration of exposure, and analyse the health effects of the exposure. Example: Healthcare retrospective cohort study You are examining the relationship between tanning bed use and the incidence of skin cancer diagnoses.

Retrospective cohort studies can be a good fit for many research projects, but they have their share of advantages and disadvantages.

Advantages of retrospective cohort studies

- Retrospective cohort studies are a great choice if you have any ethical considerations or concerns about your participants that prevent you from pursuing a traditional experimental design .

- Retrospective cohort studies are quite efficient in terms of time and budget. They require fewer subjects than other research methods and use preexisting secondary research data to analyse them.

- Retrospective cohort studies are particularly useful when studying rare or unusual exposures, as well as diseases with a long latency or incubation period where prospective cohort studies cannot yet form conclusions.

Disadvantages of retrospective cohort studies

- Like many observational studies, retrospective cohort studies are at high risk for many research biases . They are particularly at risk for recall bias and observer bias due to their reliance on memory and self-reported data.

- Retrospective cohort studies are not a particularly strong standalone method, as they can never establish causality . This leads to low internal validity and external validity .

- As most patients will have had a range of healthcare professionals involved in their care over their lifetime, there is significant variability in the measurement of risk factors and outcomes. This leads to issues with reliability and credibility of data collected.

The primary difference between a retrospective cohort study and a prospective cohort study is the timing of the data collection and the direction of the study.

A retrospective cohort study looks back in time. It uses preexisting secondary research data to examine the relationship between an exposure and an outcome. Data is collected after the outcome you’re studying has already occurred.

Alternatively, a prospective cohort study follows a group of individuals over time. It collects data on both the exposure and the outcome of interest as they are occurring. Data is collected before the outcome of interest has occurred.

Retrospective cohort studies are at high risk for research biases like recall bias . Whenever individuals are asked to recall past events or exposures, recall bias can occur. This is because individuals with a certain disease or health outcome of interest are more likely to remember and/or report past exposures differently to individuals without that outcome. This can result in an overestimation or underestimation of the true relationship between variables and affect your research.

No, retrospective cohort studies cannot establish causality on their own.

Like other types of observational studies , retrospective cohort studies can suggest associations between an exposure and a health outcome. They cannot prove without a doubt, however, that the exposure studied causes the health outcome.

In particular, retrospective cohort studies suffer from challenges arising from the timing of data collection , research biases like recall bias , and how variables are selected. These lead to low internal validity and the inability to determine causality.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 19). What Is a Retrospective Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 14 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/retrospective-cohort-studies/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is a case-control study | definition & examples, what is an observational study | guide & examples, what is recall bias | definition & examples.

Retrospective Research

‘Is the Use of Broad Consent for Retrospective Research on Data and Tissue Possible in the Framework of GDPR?’

- First Online: 27 December 2023

Cite this chapter

- Balázs Hohmann 7 &

- Gergő Kollár 7

97 Accesses

The study outlines the framework for the possibility of using previously collected and stored personal health data where the data subject has given broad consent to the processing of his or her data but the consent does not necessarily extend expressly in its wording to all subsequent research and health uses. In the light of the findings of the study, while, in the case of prospective research, consent can be an excellent legal basis for the data management of research activities, in the case of retrospective research, broad consent may in some cases raise more concerns about the lawfulness of data processing than dissolving. In these cases, where research is carried out on personal health data already obtained, the public interest or legitimate interests pursued by the controller may be the appropriate legal basis in the first place, provided that the conditions are met. This makes data processing more predictable, independent of the data subject’s consent, while, of course, maintaining the rights of other data subjects. Nevertheless, in the case of biobanks, consent was typically the legal basis used when the personal data were originally collected, and the study clarifies the requirements to be taken into account in this case.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation) (Text with EEA relevance), O.J. 4.5.2016 L 119/1.

Directive 95/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 October 1995 on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data.

Del Rio C, Malani PN (2020) COVID-19—new insights on a rapidly changing epidemic. Jama 323:1339–1340. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.3072

Article Google Scholar

European Commission (2012) Biobanks for Europe – a challenge for governance. Report of the Expert Group on Dealing with Ethical and Regulatory Challenges of International Biobank Research

Google Scholar

European Data Protection Board (2020) Guidelines 03/2020 on the processing of data concerning health for the purpose of scientific research in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak

Gefen G, Ben-Porat O, Tennenholtz M, Yom-Tov E (2020) Privacy, altruism, and experience: estimating the perceived value of Internet data for medical uses. In: Seghrouchni et al (eds) Companion proceedings of the web conference 2020. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, pp 552–556

Chapter Google Scholar

Kaye J, Briceño Moraia L, Curren L, Bell J, Mitchell C, Soini S, Hoppe N, Øien M, Rial-Sebbag E (2016) Consent for biobanking: the legal frameworks of countries in the BioSHaRE-EU Project. Biopreserv Biobank 14:195–200

Sim J, Wright C (2000) Research in health care: concepts, designs and methods. Nelson Thornes, Cheltenham

Staunton C, Slokenberga S, Mascalzoni D (2019) The GDPR and the research exemption: considerations on the necessary safeguards for research biobanks. Eur J Hum Genet 27:1159–1167

Steinsbekk KS, Kåre Myskja B, Solberg B (2013) Broad consent versus dynamic consent in biobank research: is passive participation an ethical problem? Eur J Hum Genet 21:897–902. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2012.282

Tang PC, Ash JS, Bates DW, Overhage JM, Sands DZ (2006) Personal health records: definitions, benefits, and strategies for overcoming barriers to adoption. J Am Med Inform Assoc 13:121–126

Wendler D (2006) One-time general consent for research on biological samples. BMJ 332(7540):544–547. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.332.7540.544

Widmer MA, Swanson RC, Zink BJ, Pines JM (2018) Complex systems thinking in emergency medicine: a novel paradigm for a rapidly changing and interconnected health care landscape. J Eval Clin Pract 24:629–634. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12862

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Law, University of Pécs, Pécs, Hungary

Balázs Hohmann & Gergő Kollár

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Balázs Hohmann .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Institute CNR-IFAC, National Research Council of Italy, Florence Research Area, Italy

Valentina Colcelli

Roberto Cippitani

Pathologisches Institut, Universitätsklinikum Mannheim GmbH, Mannheim, Germany

Christoph Brochhausen-Delius

Faculty of Law, University of Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany

Rainer Arnold

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Hohmann, B., Kollár, G. (2023). Retrospective Research. In: Colcelli, V., Cippitani, R., Brochhausen-Delius, C., Arnold, R. (eds) GDPR Requirements for Biobanking Activities Across Europe. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-42944-6_40

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-42944-6_40

Published : 27 December 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-42943-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-42944-6

eBook Packages : Law and Criminology Law and Criminology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

- Retrospective studies

- Research design

- Get an email alert for Retrospective studies

- Get the RSS feed for Retrospective studies

Showing 1 - 13 of 139

View by: Cover Page List Articles

Sort by: Recent Popular

Catheter ablation of atrial arrhythmias in cardiac amyloidosis: Impact on heart failure and mortality

Philippe Maury, Kevin Sanchis, [ ... ], Nicolas Lellouche

A retrospective comparison of the biceps femoris long head muscle structure in athletes with and without hamstring strain injury history

Gokhan Yagiz, Meiky Fredianto, [ ... ], Hans-Peter Kubis

The effect of obligatory Padua prediction scoring in hospitalized medically ill patients: A retrospective cohort study

Genady Drozdinsky, Oren Zusman, [ ... ], Anat Gafter-Gvili

Screening for the risk of canine impaction, what are the presumptive signs and how does it affect orthodontics? A cross-sectional study in France

Damien Brézulier, Steeven Carnet, Alexia Marie-Cousin, Jean-Louis Sixou

Topical gabapentin solution for the management of burning mouth syndrome: A retrospective study

Amanda Gramacy, Alessandro Villa

Contraction reserve in high resolution manometry is correlated with lower esophageal acid exposure time in patients with normal esophageal motility: A retrospective observational study

Yaoyao Lu, Linling Lv, Jinlin Yang, Zhihui Yi

2 and all-cause mortality of patients suffering from sepsis-associated encephalopathy after ICU admission: A retrospective study">Association between the first 24 hours PaCO 2 and all-cause mortality of patients suffering from sepsis-associated encephalopathy after ICU admission: A retrospective study

Honglian Luo, Gang Li, [ ... ], Wei Shen

Test cricketers score quickly during the ‘nervous nineties’: Evidence from a regression discontinuity design

Leo Roberts, Daniel R. Little, Mervyn Jackson, Matthew J. Spittal

The rupture risk factors of mirror intracranial aneurysms: A systematic review and meta-analysis based on morphological and hemodynamic parameters

Huang Yong-Wei, Xiao-Yi Wang, Zong-Ping Li, Xiao-Shuang Yin

Propensity score-matched analysis of physician-controlled wire-guided cannulation as an effective technique against difficult cannulation in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: A retrospective study

Han Jo Jeon, Jae Min Lee, [ ... ], Hong Sik Lee

Hypoxia as a potential cause of dyspareunia

Karel Hurt, Frantisek Zahalka, [ ... ], Martin Halad

Efficacy and tolerance of second-generation antipsychotics in anorexia nervosa: A systematic scoping review

Solène Thorey, Corinne Blanchet, [ ... ], Emilie Carretier

Exposure to dogs and cats and risk of asthma: A retrospective study

Yu Taniguchi, Maasa Kobayashi

Connect with Us

- PLOS ONE on Twitter

- PLOS on Facebook

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Interviews

- Research Curations

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access

- Submission Site

- Why Submit?

- About Journal of Consumer Research

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- WHAT IS THE FUTURE OF METHODOLOGY IN JCR?

Author notes

- < Previous

The Future of Consumer Research Methods: Lessons of a Prospective Retrospective

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Stacy Wood, The Future of Consumer Research Methods: Lessons of a Prospective Retrospective, Journal of Consumer Research , Volume 51, Issue 1, June 2024, Pages 151–156, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucae017

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Looking back at 50 years of Journal of Consumer Research methods and interviewing some of the field’s most respected methodologists, this article seeks to craft a core set of best practices for scholars in consumer research. From perennial issues like conceptual validity to emerging issues like data integrity and replicability, the advice offered by our experts can help scholars improve the way they approach their research questions, provide empirical evidence that instills confidence, use new tools to make research more inclusive or descriptive of the “real world,” and seek to become thought leaders.

Turning 50 is a reflective milestone for people and for journals. We can look back on fifty years of arduous labor, fruitful creation, bitter debate, and hard-won evolution. And, if we ignore theory, simply reflecting on the past, present, and future of consumer research methods , we have more than enough to consider. What does the history of consumer research methodology say about what could (or should) emerge in the next 50 years?

To begin, we can look back to the first episode of the Journal of Consumer Research ( JCR ), Volume 1(1), published in June 1974 and containing nine articles. The authors’ names are a Who’s Who list that we know primarily from legend (e.g., Katona, Day, Jacoby, Ferber), though one author, the prolific James R. Bettman, retired only this year. The methodologies used in the empirical papers are a pragmatic and effort-intensive collection: a set of four 20–30 minute interviews with 289 school-age boys (1st, 3rd, 5th grades) using independently trained interviewers and coders; personal interviews with 793 heads of household (HOH) in California with sample representative to state demographics and a second follow-up interview with 192 HOHs, a 4 × 4 experimental design of 192 “paid volunteer” Indiana housewives, a set of two interviews after 1 year of marriage and 2 years of marriage of ∼230 Illinois newlyweds, questionnaires about 25 purchases separately presented to husband–wife dyads in Belgium, and a questionnaire to 108 Indiana University students who reported being smokers. One methodological paper proposed a novel statistical analysis of consumer decision nets and verbal decision protocols. For those who believe that it used to be easy to do “just one study” for JCR in the good old days, the effort and deep care put into both the conceptual and external validity of data collection will belie that myth.

WHAT IS THE FUTURE OF METHODOLOGY IN JCR ?

The very first article in the very first issue of JCR speaks directly to our question of the future of consumer research. Fifty years ago, George Katona argued that the distinction between consumer research and traditional economic research on consumption (as would be appropriate in this then-new journal) was primarily a function of methodology . Katona (1974) sees the origin of true consumer research in the 1940s, saying “The survey method for collecting data on consumer behavior was practically unknown in economics immediately after World War II when the first surveys on the size and distribution of income, asset, and major expenditures were initiated with representative samples. Measures of both consumer attitudes and expectations were then developed” (1). While traditional economists might seek to find a single immutable human tendency underpinning a focal economic phenomenon, the consumer researcher was more interested in a wider descriptive exploration that would yield richer understanding. The consumer researcher, then, needed different data, including subjective reports of satisfaction, expectations, and perceived wealth. With different research questions, Katona explained that consumer research would focus more on micro-data and patterns of small situational moderators. He predicted that many economists would struggle to adopt behavioral research questions and methods but ended by stating “Looking back on three decades of research on consumer behavior, the proponents of behavioral studies of economic affairs have good reason for satisfaction.”

Katona argued that methodologies needed to evolve because the questions being asked about consumers were changing—a phenomenon we see today. Similarly, we can look at the “why and how” of our current labors to predict emergent methodologies and methodological issues. To this end, I conducted interviews with four consumer scholars known for their mastery of method and analysis, John Lynch, Leigh McAlister, Craig Thompson, and Rebecca Ratner, and asked them to reflect on the methodological history of JCR with an eye to the future.

Better Research Questions

A common refrain from our experts was the perennial challenge of starting with a “really good” research question. When asked, “What is the most important thing with methodology?” Leigh McAlister was quick to reply, “We are so obsessed with methodology, we’ve lost track of the questions .” The question, then, is what makes a question good? The answer, as I heard it, was less intuitive than might be expected.

First, we must distinguish between our research question as a program of work and as a particular project. For the former, our research questions are often too small. Good questions require that we sit and listen to real practitioners, that we learn how systems and supply chains work, that we actively explore the perspective from different communities’ lens, that we talk to people we disagree with, that we assume that effects will always be conditional, that we assume that effects are likely to change with time, that we wonder about downstream phenomena, and that we “get meta.” When we have that expansive expertise as our research raison d’etre , then we are better able to see what specific projects are interesting, how they could have impact, and how they might best be tested with confidence.

On the other hand, for the research question that drives any particular project, we are often much too broad. Here, we need focused purpose and focused conceptualization. A bad research question is one that posits an unreasonable generalization and then grudgingly offers a few boundary conditions. One characteristic of good questions is that they seem like something you could nail down with a few studies: (1) the population you need to study is identifiable, accessible, and compelling, (2) the context is specific and consequential, and (3) the conceptualization is clear, logical, and concrete enough to be operationalized closely.

Having invested in a broad research question for our program of study, we have the knowledge base, the long-term perspective, and the time to see the results of any single research question in a project as cumulative, adding to a more nuanced and more confident knowledge about what’s happening (and why) in our domain of interest. I know from experience that having a conceptually diverse portfolio of projects is a dangerously enticing temptation for scholars—so very interesting but requiring an exhausting amount of work to keep from doing each in a superficial way. At some point, scholars must find their one true thing—the research domain where they will invest their bounded resources, build grounded knowledge over years, and establish thought leadership. However, in a long and rich career, many of us will have more than one research focus in that span and that can help keep us motivated—what my old USC colleague, Bill Bearden, called the “fire in the belly.”

It is notable that our experts call us to consider how we choose our questions as two papers appearing in the special issue speak to the outcome. Wang et al. (2024) explore how the impact that any one paper may have is a function of its novelty in either topic, finding, or combinatorial approach—suggesting the core of what is an inherently interesting research question. Looking beyond any one paper, Pham, Wu, and Wang (2024) seek to recognize and conceptualize thought leadership as the combination of the amount of research that scholars publish and the impact of those publications. Their impact metric shows that having a clear focus on one’s work is often a common characteristic of scholars known as thought leaders. These articles offer both guidance to younger scholars seeking to build programs of research and, to more experienced scholars, a way to look at scholarly output through a new lens.

More Critical Consideration of Conceptual Validity

With an appropriately rich research question driving us and a sufficiently specific research question framing a project, are we then ready to talk about methodology? Not so fast, our experts warned; we have not yet emphasized the importance of conceptual validity ( MacKenzie 2003 ). As John Lynch said, “Validity is not a function of research technique, but a function of the inevitable incompleteness of our understanding of the phenomena we study.”

The experts note that, over the years, growing sophistication of analysis in the Journal of Consumer Research (and other journals, to be fair) has led some researchers to mistakenly believe “that fancy analytical models correct for everything.” Yet, others have outlined the danger of overemphasizing analytical sophistication to the detriment of other research basics ( Lehmann, McAlister, and Staelin 2011 ). In any study, what can we say with complete confidence about conceptual validity? We can say that we collected data in the form of specific questions or observations from a specific population under conditions that we altered in specific ways. As readers of scientific papers, we often struggle to understand exactly what these specifics were because they are re-named with conceptual labels assigned by the researcher. Thus, a researcher might require a participant to watch a clock while making a choice and then label that anything from time pressure to temporal salience to cognitive load. Perhaps, then, we need to be more descriptive about our operationalizations and, as our experts emphasize, more aware how stimulus-dependent and context-dependent our studies are. As we assess the nature of our own findings and those of others, we must try to learn from failures to replicate findings that are counter to expectations. It suggests that multi-pronged approaches are natural and necessary in any exploration. It suggests that we stop lamenting “the study didn’t work” but rather say “the study results were different and I’m going to see if I can tell why.”

Replications That Build Knowledge

By prioritizing conceptual reasoning, we accept the hard work of looking at the details of what is happening in any given study, but we also take the pressure off in different ways. Rebecca Ratner notes that “the review process exacerbates the file-drawer problem because researchers hear, ‘Don't include Study X because its findings aren't consistent and it complicates the story.’” And, while a focus on conceptual reasoning increases the difficulty in conducting and reporting replications (as we must consider whether a true conceptual replication is taking place rather than just copying stimuli), it takes the pressure off by reducing knee-jerk rejections of past work. Analyses over time allow for more data and therefore better understanding. This point echoes in our field; Sawyer and Peter (1983) wrote about the significance of significance, reminding us that using p < .05 as a certain and forever way of falsifying hypotheses is a false hope. They write, “Attention should be placed on the data themselves and their descriptions. Instead of relying solely on classical inferential statistics, researchers should make added use of replication, Bayesian statistics, meta-analysis, and strong inference to provide more meaningful examination of theoretical questions in marketing research.” This perspective is increasingly discussed in marketing ( McShane et al. 2024 ) and dominates other fields like biomedical research ( Savitz et al. 2024 ), where more studies of all sorts are simply ways to increase estimation accuracy. Ultimately, prioritizing conceptual validity is both harder and easier—it is harder to do, but easier to live with.

This echoes themes from two papers in the special issue. Eisend et al. (2024) contend that consumer research, as a distinct domain, demonstrates strong knowledge-building and is on an upward trajectory of increasingly distinct and robust effects, largely due to improvements in experimental methods and analysis. And, in moving forward, Urminsky and Dietvorst (2024) address estimation accuracy and the variability commonly observed in consumer research. They describe four types of replications that, when put into regular practice, can benefit researchers and knowledge-building.

New Populations, Methods, and Analyses

When asked what new methods and analyses are on the horizon, our experts had different perspectives. While Craig Thompson said, “new methods certainly arise over time in response to technological shifts—netnographies or more sophisticated QDA packages—but the foundational principles of anthropological, historical, and sociological analyses have remained fairly stable,” in contrast, Leigh McAlister enthused that the internet made so many more types and sources of data available and “new software fast followed” to allow better analysis of it. John Lynch and Rebecca Ratner saw some changes in field and lab studies but allowed they “weren’t that futuristic.” What then can we expect to see?

One overarching similarity our experts raised is a growing disillusionment with convenience samples, arguing that increased access to specific consumer populations suggests we should take greater care with how and where we recruit participants. There are two ways to increase the value of our participant groups; focus more tightly on the group of consumers who best illustrate our research question or cast a very wide net that captures consumer groups one would expect could differ. These strategies suggest different plans for analysis, but both serve to increase the reader’s confidence in the implications of the results. As Lynch (in a 1982 paper on external validity) argues, we don’t aim to “achieve” external validity, but rather to “assess” it by testing for background factor × treatment interactions and, for this, variation on background factors is needed.

Additionally, an increasingly networked and communication-enabled world means that we can share our findings with our participant populations and let them “speak back to the data.” Looking at JCR ’s first articles, while samples were often restricted to a convenience locale (e.g., a population of schoolboys in one town; Illinois newlyweds), they showed a depth of interaction (e.g., four interviews with each schoolboy; two surveys of the newlyweds spaced a year apart) which allowed for more of the participant’s input and interpretation to influence the researcher. That is the paradox of the new world of globally accessible data—we can use the internet to engage with a greater diversity of people, but we must be careful to not engage at the most distant or sterile remove.

If we can reach more or different people to be participants in our studies, we can also access and observe an expanded set of consumer behaviors. For example, we can study how people feel and think by looking at the language they use in public spaces; several of the experts saw textual analysis as a fast-growing and exciting research capability. We can track physiological measures to supplement or substitute for self-reports of affective and cognitive states; some experts saw the ability to better integrate physiological measures like eye-tracking or hormonal assays as a way to build new bridges between choice research and medical research. Online retail offers scope for large-scale field studies. Online choice contexts offer far more with attentional measures, process tracking, identity motivations, and following individuals across multiple platforms over time. The growth of large-scale databases (in both corporate and public policy sectors) over the last decade or two creates a promising opportunity to conduct longitudinal research without waiting years in primary research collection. A new methodological skill for the modern consumer researcher, then, is to become a better self-marketer, translator, and negotiator to those corporations and public organizations so that one is given access to existing longitudinal data. In university contexts, often the access to special populations or data is through grants and cooperative research projects that are common in other fields, but new to many in consumer research where we have long enjoyed the ability to do relatively inexpensive research under our own steam, oversight, and funding. Now, the modern consumer researcher will need methodological skills that improve interdisciplinary connections and serve to make them valued partners on multi-college grants.

Translation, Integration, and Intervention

Another new skill that consumer researchers are likely to need in the next 50 years in JCR is the ability to develop practical interfaces between real consumers/marketers and the knowledge we create. Our “job” in any one publication is to build knowledge, but there are many business school stakeholders (e.g., corporate and nonprofit partners, donors, students, administrators, society at large) who want more for their money; more so than in the past, academics are asked to take their ideas from the “bench” all the way to use. For example, the Journal of Marketing has a special issue that requires the inclusion of a web app designed for public use to help real-world marketers or consumers. This requires the ability to envision and design use-applications, but also to iterate more with practitioners to make sure our help really helps. Will this then lead to a research genre in consumer behavior akin to randomized clinical trial intervention studies? Either way, the ability to provide effective help relies on the rich breadth of knowledge advocated by our experts. As our experts agreed, if you do not know enough about the context of the domain, then you cannot understand whether any one consumer choice or behavior matters in the larger scheme. As with investigations of environmental sustainability, do our results show how shaping consumer choice is important, or rather that any attempt to ideally shape consumer choice is “a drop in the ocean”? When we try to create the intervention, we see how the importance of individual versus structural changes can shift with the cost/effort of the intervention and have a better appreciation for the constraints of the marketer acting in the real world.

Where Is Artificial Intelligence?

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a frequent topic in future-oriented discussions of business and business research. But, perhaps surprisingly, it did not emerge as a leading topic in these interviews. There is increasing research on the use of AI in the marketplace, such as consumer resistance ( Longoni, Bonezzi, and Morewedge 2019 ), but our editorial team believes that we should begin talking more comprehensively about where AI will potentially be in common use by researchers. We can see its use in background research and literature reviews. We can see its use in writing and content creation such as surveys, stimuli, and manuscripts. We can see its use in data collection, data generation, and data analysis. We can even see its use in review and publication. This expansive scope of possibilities and an uncertain timeline may be exactly why many experts are not quick to offer strong predictions, either descriptively or prescriptively. As a field, we should carefully consider a futurecast of AI in research systems and call for more editorial thinking on these issues.

Confidence versus Integrity

One thing that captures attention in the changing world of research is the issue of data integrity. JCR , like many journals, sought to increase the transparency and accountability of research published in the journal by requiring datasets be provided and open to the review team. Readers can see the current policies at https://consumerresearcher.com/research-ethics . But, though any given set of policies may evolve, our experts focused on the two key issues: integrity and confidence. In this distinction, integrity is the table-stakes of research. When a researcher’s integrity is in question, no methodology they offer will matter. This is because there are so many places where consumer research methodologies are vulnerable to bad actors. Where data can be made up or manipulated. Where studies can be analyzed and then hidden in file drawers. Where interviewees can be led. Where meanings can be misinterpreted. Where p s can be hacked. Where outliers can be cleaned from the dataset. Where hands can be waved over problematic inconsistencies. Where best practices change with new abilities. Because most of these vulnerabilities are hard to protect and harder to police, we rely necessarily on the integrity of the researcher—the core belief that the researcher is providing the most unbiased and truthful test of their research question even if that means disproving their theories or having to give up on their idea. In other words, integrity in research is the researcher’s true curiosity about the answer to their research question, convenient or inconvenient to their own ends, and their striving to do all in their abilities to provide that answer.

Confidence is a function of persuasion, as the authors attempt to make a compelling argument for the evidence presented. How confident are we, as readers, that the supporting evidence is strong and accurately interpreted? This is a high hurdle and assumes that the author is acting with integrity. If the researcher is sincere and acts with integrity, we as readers now assess whether the researcher has done a good job. For example, is the focal construct distinct from other related constructs? How has the constructed been measured? How has it been manipulated? Did the instructions prompt participants in a certain direction? Were the authors careful to create clear tests, realistic stimuli, and unbiased contexts? Were the authors careful to shape interview scripts in a way that minimized interviewer influence or social desirability? Were research populations the most relevant for the research question or were they convenience populations? What analyses were used to shape interpretation of the data and were they the most appropriate or up to date?

Thus, there are many ways that a researcher can make their empirical evidence instill confidence through thoughtful design and testing. Other means are emerging. For example, some scholars appreciate preregistration as a means to discourage questionable research practices in overfitting data—something that can give readers confidence in the analysis of the researchers. However, other scholars see preregistration as a practice privileged to researchers with the budget to conduct multiple studies or as performative virtue-signaling. Because of this debate perhaps, preregistration has not been shown to increase trust in findings ( Field et al. 2020 ). In the end, there are many aspects of consumer research analysis (no matter the specific methodology) that are not wrong but still fail to instill confidence in the reader. To this end, JCR has often published work that sets a standard, especially in new or evolving areas, for what constitutes excellent evidence in a methodological domain and these types of papers will continue to be important to our field.

A 50-year retrospective provides a trajectory that we can follow in imagining future changes in methodology. New methodologies may emerge with novel technological capabilities, but their adoption is a function of whether they better answer the questions we are currently asking about consumers. One of the best things we can do for our methodological success is to be more critical in defining our research questions—a skill that requires honing across one’s career. We are well-served by framing different questions for our program of research (pushing ourselves to embrace the rich breadth of a domain) versus a research project (pushing ourselves to focus on one important and answerable question). Next, our work profits by critically considering our construct definition (and operationalization)—this is critical, as poor construct validity cannot be overcome with novel sophisticated analyses. The good news of greater effort in conceptual clarity is that it helps take pressure off any one study and guides replication efforts to focus on increasing estimation accuracy rather than disproving famous effects. There are new types of data to explore (textual, physiological, digital), and best practices will continue to evolve—most conclusively with methodological papers published to propose and teach emerging norms. Importantly, there are new populations of consumers to study and many new means to reach them in a meaningful way. Our methods may shift in our need to be better translators of the behaviors we observe and better able to view those behaviors within the wider systematic context, where practitioners seek to solve big problems and make significant changes to consumer behaviors. Our methods may need to mimic other prescriptive sciences (e.g., public health, medicine, environmental science) if we seek to provide solutions. We must embrace our own integrity and avoid a cynical attitude toward research and the review process. JCR —as an arbiter of integrity—walks the narrow path that protects both the accuser and the accused when breaches of integrity are suspected. Ultimately, however, the larger threat to consumer research is when we fail to have confidence in the empirical support for a project because of vague, convenient, superficial, sloppy, or out-of-date practices in data collection and analysis. In the end, our methodologies lie within a scholarly toolbox that also contains our curiosity, motivation, critical thinking, integrity, and openness.

Stacy Wood ( [email protected] ) is the J. Lloyd Langdon Distinguished University Professor of Marketing at the Poole College of Management, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA.

The author thanks the panel of esteemed consumer scholars—John Lynch, Leigh McAlister, Rebecca Ratner, and Craig Thompson—who shared their experiences, expertise, and love of research in deep and wide-ranging conversations. It is hoped that readers of this article benefit from their insights as much as the author who had the privilege of hearing them firsthand.

Eisend Martin , Pol Gratiana , Niewiadomska Dominika , Riley Joseph , Wedgeworth Rick ( 2024 ), “ How Much Have We Learned about Consumer Research? A Meta-Meta-Analysis ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 51 ( 1 ), forthcoming.

Google Scholar

Field Sarahane M. , Wagenmakers E. J. , Kiers H. A. L. , Hoekstra R. , Ernst A. F. , van Ravenzwaaij D. ( 2020 ), “ The Effect of Preregistration on Trust in Empirical Research Findings: Results of a Registered Report ,” Royal Society Open Science , 7 ( 4 ), 181351 .

Katona George ( 1974 ), “ Psychology and Consumer Economics ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 1 ( 1 ), 1 – 8 .

Lehmann Donald R. , McAlister Leigh , Staelin Richard ( 2011 ), “ Sophistication in Research in Marketing ,” Journal of Marketing , 75 ( 4 ), 155 – 65 .

Longoni Chiara , Bonezzi Andrea , Morewedge Carey K. ( 2019 ), “ Resistance to Medical Artificial Intelligence ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 46 ( 4 ), 629 – 50 .

Lynch John G. ( 1982 ), “ On the External Validity of Experiments in Consumer Research ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 9 (3), 225 – 39 . https://doi.org/10.1086/208919

MacKenzie Scott B. ( 2003 ), “ The Dangers of Poor Construct Conceptualization ,” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science , 31 ( 3 ), 323 – 6 .

McShane Blake B. , Bradlow Eric T. , Lynch John G. , Meyer Robert J. ( 2024 ), “ “Statistical Significance” and Statistical Reporting: Moving beyond Binary ,” Journal of Marketing . https://doi.org/10.1177/00222429231216910

Pham Michel Tuan , Wu Alisa Yinghao , Wang Danqi ( 2024 ), “ Benchmarking Scholarship in Consumer Research: The p-Index of Thought Leadership ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 51 ( 1 ), forthcoming.

Savitz David A. , Wise Lauren A. , Bond Julia C. , Hatch Elizabeth E. , Ncube Collette N. , Wesselink Amelia K. , Willis Mary D. , Yland Jennifer J. , Rothman Kenneth J. ( 2024 ), “ Responding to Reviewers and Editors about Statistical Significance Testing ,” Annals of Internal Medicine , 177 ( 3 ), 385 – 6 . https://doi.org/ 10.7326/M23-2430

Sawyer Alan G. , Peter J. Paul ( 1983 ), “ The Significance of Statistical Significance Tests in Marketing Research ,” Journal of Marketing Research , 20 ( 2 ), 122 – 33 .

Urminsky Oleg , Dietvorst Berkeley J. ( 2024 ), “ Taking the Full Measure: Integrating Replication into Research Practice to Assess Generalizability ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 51 ( 1 ), forthcoming.

Wang Xin (Shane) , Hyun (Joseph) Ryoo Jun , Campbell Margaret C. , Inman J. Jeffrey ( 2024 ), “ Unraveling Impact: Exploring Effects of Novelty in Top Consumer Research Journals ,” Journal of Consumer Research , 51 ( 1 ), forthcoming.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1537-5277

- Print ISSN 0093-5301

- Copyright © 2024 Journal of Consumer Research Inc.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Surveys Academic Research

Retrospective Study: What it is & How to Do it

In a retrospective study , existing data are examined to identify risk factors for particular diseases. Interpretations are limited as it is impossible to go back in time and gather the missing information. Let’s talk about that.

What is a Retrospective Study?

A retrospective study is an analysis that compares two groups of individuals. A case group and a control group. Both groups are similar, but the case group has a key factor that is being studied or investigated that the control group does not.

It brings up key differences in individuals or groups of individuals based on some events/incidences. It’s a psychological approach to pinpoint key differences in individuals that are alike but differ slightly based on certain characteristics.

What is the importance of a Retrospective Study?

This study is greatly important in many aspects, be it personal development, socio-economic welfare, or professional development.

This study is also important to fixate certain characteristics within individuals by considering historical data and making rational decisions. In large organizations, this becomes very important because organizations deal with large groups of clients with almost (but not completely) alike behaviors.

This is the stage where retrospection comes into play to understand differences and similarities among clients and act accordingly.

Advantages and disadvantages of a Retrospective Study

Similar to other studies, there are benefits and drawbacks to retrospective studies. Researchers must critically evaluate the method that is used and carefully interpret the results of retrospective studies before putting them to practice.

Advantages:

- Researches have control of the number of participants in the case group and control group.

- Typically less expensive to conduct in comparison to other methods.

- Timeline of a retrospective study is quicker to complete

Disadvantages:

- Poor control over exposure factor

- If research is not thorough, there could be missing history/background and or information.

- If researchers are not careful, selection and recall bias can affect the results

How to conduct a Retrospective Study

There are certain ways to conduct a retrospective study. Most of them collect vast historical data and make sense of it statistically. Another way is by considering 2 groups with similar attributes and then conducting Surveys (That’s where QuestionPro shines!) to find out differing characteristics. In general, there are 2 parts to it:

Prospective Study

Retrospective study.

For the sake of this article, let’s just stick to the retrospective study. An organization can take many surveys and collect data from them. This data can then be processed to make important business decisions. This will help the organization understand its clients and help provide more viable products and services that would actually make a difference.

Retrospective Study Examples

These studies aim to study a situation, condition, event, or phenomenon that has already happened. This study is often used in the medical industry to study different medical conditions and illnesses. Using participants who have an existing condition compared to a group that does not have that particular condition.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, this study deals with enhancing minor differences amongst similar groups. These differences are brought up by studying and statistically sourcing historical data collected by various means. One such method to collect data and perform this study is by taking surveys.

QuestionPro has a rich arsenal of tools and products to bring the most out of such studies. These tools collect useful insights and help in procuring pinpoint differences within the most similar groups of individuals and further accelerating the study.

CREATE FREE ACCOUNT

Authors : Siddharth Kulkarni & Jenny Huang

MORE LIKE THIS

Data Information vs Insight: Essential differences

May 14, 2024

Pricing Analytics Software: Optimize Your Pricing Strategy

May 13, 2024

Relationship Marketing: What It Is, Examples & Top 7 Benefits

May 8, 2024

The Best Email Survey Tool to Boost Your Feedback Game

May 7, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Asia & Oceania

Middle east & africa.

- United States

- Asia Pacific

- Australia & NZ

- Southeast Asia

- Czech Republic

- Deutschland

- España

- Switzerland

- United Kingdom

EMEA Thought Leadership

Developing IQVIA’s positions on key trends in the pharma and life sciences industries, with a focus on EMEA.

- Middle East and Africa

Life Sciences Solutions

Healthcare solutions.

- Medical Device and Diagnostic

- U.S. Government

Bringing together unparalleled healthcare data, advanced analytics, innovative technologies, and healthcare expertise to create intelligent connections that speed the development and commercialization of innovative medicines to improve patient lives.

- Commercial Solutions

- Contract Sales and Medical Solutions

- Financial Services

- Information Solutions

- Medical Affairs

- Real World Evidence

Accelerate digital innovation to enable smarter decisions that reduce cost, modernize patient and consumer engagement, and improve health outcomes.

- Health Plans

- Hospitals and Health Systems

- Insurers and Risk

- Medical Specialty Societies

- Patient Advocacy Organizations

Medical Device and Diagnostic Solutions

Your world is unique – and quite different from pharma. In the U.S., decision-making has shifted from individual physicians to integrated networks--GPOs, IDNs and payers. These groups have heightened the focus on proving your solution’s value, demanding outcomes analyses and putting pressure on pricing.

- Hospital Procedures and Diagnosis

- Medical Device Supply Audit

- MedTech Business Insights and Trends Podcast Series

U.S. Government Solutions

For government agencies and organizations at every level—from federal or national to regional and local—Big Data can have a huge impact on public health.

U.S. PROGRESS POINT

A curation of IQVIA's best thinking on topics and trends driving change, disruption, and progress in the United States healthcare market.

Get the latest insights on our life sciences, healthcare, and medical technology solutions in the United States. Follow our blog today!

U.S. INSIGHTS LIBRARY

"Browse our library of insights and thought leadership.

ON-DEMAND WEBINARS

Visit our library of on-demand webinars.

UPCOMING EVENTS & WEBINARS

View our upcoming events and webinars.

FEATURED WEBINAR

"Top Issues for Pharma to Watch in 2022 and 2023

Get instant access

You may also be interested in.

For this browsing session please remember my choice and don't ask again.

- Biostatistics

- Data Science

- Programming

- Social Science

- Certificates

- Undergraduate

- For Businesses

- FAQs and Knowledge Base

- Test Yourself

- Instructors

Prospective vs. Retrospective

A prospective study is one that identifies a scientific (usually medical) problem to be studied, specifies a study design protocol (e.g. what you’re measuring, who you’re measuring, how many subjects, etc.), and then gathers data in the future in accordance with the design. The definition of the problem under study does not change once the data collection starts.

A retrospective study is one in which you look backwards at data that have already been collected or generated, to answer a scientific (usually medical) problem.

Prospective studies are generally regarded as cleaner and more reliable, due to several shortcomings of retrospective studies:

- Since the data are already available, the question to be answered can be influenced by the data

- Similarly, the exact data (or subset of data) used to answer the question can be drawn in a way that produces the desired answer, or a more noteworthy or interesting answer

- There is a temptation to modify the question being studied as the data are examined

Some prospective studies have retrospective aspects. Cohort and panel studies, which often follow a group over time, often collect information about the past. For example, participants may be asked if they had any medical conditions as a child, e.g. exposure to severe sunburn. However, in such cases, there is also an aspect of tracking events into the future.

A good example is a study following cigarette smokers over time, to see what medical conditions they contract during the study. This information would typically be compared to similar information from non-smokers. Although prior information from the participants might be used, the primary focus is what happens to each group during the period of the study. Sometimes called a “prospective cohort study,” these studies often fall short of the “gold standard” of a randomized trial, because the assignment to the treatment or control group is usually not random. One could not assign a person randomly to be a lifetime cigarette smoker or non-smoker. However, the outcome of interest (e.g. lung cancer) is something that develops or becomes apparent during the course of the study. Nobody is being selected on that basis, so the opportunity for selection bias is limited.

Another type of study is fully retrospective: the groups are selected on the basis of the outcome of interest. For example, one might look at a group of lung cancer patients and compare them to a group of patients without lung cancer to examine the prevalence of smoking in each group. The conclusions from such a study may not be as solid as those from prospective studies. You can demonstrate correlation, but external factors and aspects outside the scope of the study have a greater opportunity to creep in and bias the results (see selection bias ) than with a prospective study where you identify groups beforehand and then observe what happens to them. In addition to bias, there can be problems with data quality. Some records may be missing. Subjects’ recall may be faulty. Plus, you don’t have the opportunity to collect data tailored to the needs of the study that you would with a prospective study. It may, as a result, be more difficult to make the leap from correlation to causation with a retrospective study than a prospective study.

The long process of proving a relationship between cigarette smoking and lung cancer is a good case study. Rates of smoking increased dramatically in the U.S. in the 1940’s and 1950’s, as cigarettes became more widely available and advertising glamorized their use. The incidence of lung cancer (which had been at relatively low rates prior to the wars) also increased. However, strong evidence of a link between the two was lacking.

This began to change in the 1950s. Five larger retrospective studies were published in the early 1950’s that again showed a link between cigarette smoking and lung cancer. Though important, these studies still didn’t make a convincing enough case as they relied on the self-reported smoking habits of people who already had lung cancer, and compared them to those who didn’t. One potential problem with this type of study is that people with lung cancer are more likely to overestimate how much they smoked, while those who don’t have lung cancer are more likely to underestimate how much they smoked.