An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

Effects of a Physical Education Program on Physical Activity and Emotional Well-Being among Primary School Children

Irina kliziene.

1 Educational Research Group, Institute of Social Science and Humanity, Kaunas University of Technology, Kaunas 44249, Lithuania

Ginas Cizauskas

2 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering and Design, Kaunas University of Technology, Kaunas 51424, Lithuania; [email protected]

Saule Sipaviciene

3 Department of Applied Biology and Rehabilitation, Lithuanian Sports University, Kaunas 44221, Lithuania; [email protected]

Roma Aleksandraviciene

4 Department of Coaching Science, Lithuanian Sports University, Kaunas 44221, Lithuania or moc.liamg@ednargallenamor (R.A.); [email protected] (K.Z.)

5 Sports Centre, Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas 51211, Lithuania

Kristina Zaicenkoviene

Associated data.

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

(1) Background: It has been identified that schools that adopt at least two hours a week of physical education and plan specific contents and activities can achieve development goals related to physical level, such as promoting health, well-being, and healthy lifestyles, on a personal level, including bodily awareness and confidence in physical skills, as well as a general sense of well-being, greater security and self-esteem, sense of responsibility, patience, courage, and mental balance. The purpose of this study was to establish the effect of physical education programs on the physical activity and emotional well-being of primary school children. (2) Methods: The experimental group comprised 45 girls and 44 boys aged 6–7 years (First Grade) and 48 girls and 46 boys aged 8–9 years (Second Grade), while the control group comprised 43 girls and 46 boys aged 6–7 years (First Grade) and 47 girls and 45 boys aged 8–9 years (Second Grade). All children attended the same school. The Children’s Physical Activity Questionnaire was used, which is based on the Children’s Leisure Activities Study Survey questionnaire, which includes activities specific to young children (e.g., “playing in a playhouse”). Emotional well-being status was explored by estimating three main dimensions: somatic anxiety, personality anxiety, and social anxiety. The Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS) was used. (3) Results: When analysing the pre-test results of physical activity of the 6–7- and 8–9-year-old children, it turned out that both the First Grade (92.15 MET, min/week) and Second Grade (97.50 MET, min/week) participants in the experimental group were physically active during physical education lessons. When exploring the results of somatic anxiety in EG (4.95 ± 1.10 points), both before and after the experiment, we established that somatic anxiety in EG was 4.55 ± 1.00 points after the intervention program, demonstrating lower levels of depression, seclusion, somatic complaints, aggression, and delinquent behaviours (F = 4.785, p < 0.05, P = 0.540). (4) Conclusions: We established that the properly constructed and purposefully applied eight-month physical education program had positive effects on the physical activity and emotional well-being of primary school children (6–7 and 8–9 years) in three main dimensions: somatic anxiety, personality anxiety, and social anxiety. Our findings suggest that the eight-month physical education program intervention was effective at increasing levels of physical activity. Changes in these activities may require more intensive behavioural interventions with children or upstream interventions at the family and societal levels, as well as at the school environment level. These findings have relevance for researchers, policy makers, public health practitioners, and doctors who are involved in health promotion, policy making, and commissioning services.

1. Introduction

Teaching in physical education has evolved rapidly over the last 50 years, with a spectrum of teaching styles [ 1 ], teaching models [ 2 ], curricular models [ 3 ], instruction models [ 4 ], current pedagogical models [ 5 , 6 ], and physical educational programs [ 7 ]. As schools provide benefits other than academic and conceptual skills at present, we can determine new ways to meet different goals through a variety of methodologies assessing contents from a multidisciplinary perspective. Education regarding these skills should also be engaged following a non-traditional methodology in order to overcome the lack of resources in traditional approaches and for teachers to meet their required goals [ 8 ].

Schools are considered an important setting to influence the physical activity of children, given the amount of time spent at school and the potential for schools to reach large numbers of children. Schools may be a barrier for interventions to promote physical activity (PA). Children are required to sit quietly for the majority of the day in order to receive academic lessons. A typical school day is represented by approximately 6 h, which may be extended by 30 min or longer if the child is provided motorized transportation and does not actively commute to and from school. Donnelly et al. [ 9 ] found that teachers who modelled PA by active participation in physical activity across the curriculum (i.e., promoted 90 min/week of moderate to vigorous physically active academic lessons; 3.0 to 6.0 METs, ∼10 min each) had greater SOFIT (a Likert scale from one to five, anchored with lying down for one and very active for five) scores shown by their students, compared to primary students with teachers using a lower level of modelling. Some studies have proposed the use of prediction models of METs for children, including accelerometer data. In such models, the slope and intercept of ambulatory activities (e.g., walking and running) differ from those of non-ambulatory activities, such as ball-tossing, aerobic dance, and playing with blocks [ 10 , 11 ]. Wood and Hall [ 12 ] found that children aged 8–9 years engaged in significantly higher moderate to vigorous physical activities during team games (e.g., football), compared to movement activities in PE lessons (e.g., dance).

It has been identified that schools which adopt two hours a week of PE and plan specific contents and activities to achieve development goals at the physical level can promote health, well-being, and healthy lifestyles on a personal level, including bodily awareness and confidence in one’s physical skills, as well as a general sense of well-being, greater security and self-esteem, sense of responsibility, patience, courage, and mental balance at the social level, including integration within society, a sense of solidarity, social interactions, team spirit, fair play, and respect for rules and for others, as well as wider human and environmental values [ 13 , 14 ]. Physical activity programs have been identified as potential strategies for improving social and emotional well-being in at-risk youth [ 15 ]. Emotional well-being permeates all aspects of the experience of children and has emerged as an essential element of mental health and reduction of anxiety, as well as a core component of health in general. Schools have a strong effect on children’s emotional development, and as they are an ideal environment to foster children’s emotional learning and well-being, failing to optimize the opportunity to do so could impact communities in negative ways [ 16 , 17 ]. Physical activity and exercise have positive effects on mood and anxiety, and a great number of studies have described the associations between physical activity and general well-being, mood, and anxiety [ 18 ]. Physical inactivity may also be associated with the development of mental disorders: some clinical and epidemiological studies have shown associations between physical activity and symptoms of depression and anxiety in cross-sectional and prospective longitudinal studies [ 19 ]. Low physical activity levels have also been associated with an increased prevalence of anxiety [ 20 ]. Levels of physical activity lower than those recommended by the World Health Organization are classified as a lack of physical activity or physical inactivity. Current guidelines on physical activity for children and adolescents aged 5–17 years generally recommend at least 60 min daily of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activities [ 21 ].

Therefore, we formulated the following research hypothesis: The application of a physical education program can have a positive impact on the physical activity and emotional well-being among primary school students.

The purpose of this study was to establish the effect of a physical education program on the physical activity and emotional well-being of primary school children.

Novelty of the work: For the first time, PE curriculum has been developed for second grade children, a new approach to physical education methodology. For the first time, anxiety is measured between first and second grades. Physical education has been a part of school curriculums for many years, but, due to childhood obesity, focus has increased on the role that schools play in physical activity and monitoring physical fitness [ 22 , 23 ].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. participants.

The schools utilized in this study were randomly chosen from primary schools in Lithuania. Four schools were chosen from different areas of Lithuania, which are typical of the Lithuanian education system (i.e., the state system), exercising in accordance with the description of primary, basic, and secondary education programs approved by the Lithuanian Minister of Education and Science in 2015. It ought to be noted that these schools structured classes without applying selection criteria; accordingly, it very well may be said that the students in the randomly chosen classes were additionally randomly allocated to the experimental and control groups. A non-probabilistic accurate sample was utilized in the study, where subjects were incorporated relying upon the objectives of the study.

The time and place of the study, with the consent of the guardians, were settled upon ahead of time with the school administration. This study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Kaunas University of Technology, Institute of Social Science and Humanity (Protocol No V19-1253-03).

The experimental group included 45 young women and 44 young men aged 6–7 years (First Grade) and 48 young women and 46 young men aged 8–9 years (Second Grade). The control group included 43 young women and 46 young men aged 6–7 (First Grade) and 47 young women and 45 young men aged 8–9 years (Second Grade). All children went to a same school.

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. the evaluation of physical activity.

The Children’s Physical Activity Questionnaire [ 24 ] was utilized, which is based on the Children’s Leisure Activities Study Survey (CLASS) questionnaire, which includes activities explicit to small children, such as “playing in a playhouse.” The original intent of the proxy-reported CLASS questionnaire for 6–9 year olds was to evaluate the type, recurrence, and intensity of physical activity over a standard week [ 24 ].

2.2.2. The Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale

Enthusiastic well-being status was investigated by estimating three principal dimensions: somatic anxiety, personality anxiety, and social anxiety. The Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS) contains 37 items with 28 items used to measure anxiety and an additional 9 items that present an index of the child’s level of defensiveness. We were only concerned with the factor analysis of anxiety; along these lines, only those 28 items used to gauge anxiety were utilized. The RCMAS comprises three factors: (1) somatic anxiety, consisting of 12 items; (2) personality anxiety, consisting of 8 items; and (3) social anxiety, consisting of 8 items [ 25 ].

The outcomes were estimated as follows: (1) physical anxiety (more than or equal to 6.0 points—high somatic level, from 5.9 to 4.5 points—typical somatic level, and from 4.4 to 1.0 points—low somatic level); (2) personality anxiety (from 2.0 to 2.5 points—low personality anxiety level, from 2.6 to 3.5 points—typical personality anxiety level, and from 3.6 to 4.5 points—high personality anxiety level); and (3) social anxiety (more than or equal to 5.5 points—high social anxiety level, from 5.4 to 4.5 points—typical social anxiety level, and from 4.4 to 3.3 points—low social anxiety level). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the subscales ranged from 0.72 to 0.73.

2.3. Procedure

In this study, a pre-/mid-/post-test experimental methodology was utilized, in order to avoid any interruption of educational activities, due to the random selection of children in each group. The experimental group (First and Second Grades) was trialled for eight months. The technique for the physical education program was developed, and a model of educational factors that encourage physical activity for children was constructed.

Likewise, the methodical material for the physical education program [ 7 , 24 ] was prepared. The methodology depended on the dynamic exercise, intense motor skills repetition, differentiation, seating and parking reduction, and the physical activity distribution in the classroom (DIDSFA) model [ 26 , 27 ] ( Table 1 ).

Dynamic exercise, intense motor skills reiteration, differentiation, seating and parking reduction, and physical activity distribution in the classroom (DIDSFA) model—expanding dynamic learning time in primary physical education.

A physical education program was designed in order to advance physical activity to a significant degree, show development skills, and be agreeable. The suggested recurrence of physical education classes was three days out of the week. A typical DIDSFA First Grade model exercise lasted 30 min and had three sections: health fitness activities (10 min), ability fitness activities (15 min), and unwinding, focus, and reflection (5 min). The Second Grade model exercise lasted 45 min and comprised four sections: health fitness activities (20 min), ability fitness activities (20 min), and unwinding, focus, and reflection (5 min). Ten health-related activity units were designed, including aerobic dance, aerobic games, strolling/running, and jump-rope. The movements were developed by changing the intensity, length, and intricacy of the activities.

Although our primary focus was creating cardiovascular stamina, brief activities to develop stomach and chest strength, as well as movement skills, were incorporated. To improve motivation, children self-estimated and recorded their fitness levels from month to month. Four game units which developed ability-related fitness were incorporated (basketball, football, gymnastics, and athletics), and details of healthy lifestyles and unconventional physical activities were introduced. These sports and games had the potential for advancing cardiovascular fitness and speculation in the child’s community (e.g., fun transfers); unwinding, focus, and reflection improving with regular exercise; and valuable impacts for meditation or unwinding, namely through children’s yoga ( Table 2 ).

Physical education program (First and Second Grades).

During the study, physical education activities were taught through physical schooling, by preparing a textbook comprising two interrelated parts: (a) a textbook and (b) children’s notes. The textbooks were filled with logical tasks, self-evaluation, and activities relating to spatial perception and self-improvement. The methodological devices provide strategies for practicing with textbooks. The physical education pack considers a “natural” kind of integration and dynamic learning, building awareness, encouraging sensitivity to nature, and supporting healthy styles of living. The physical education pack takes into consideration a “natural” kind of integration and dynamic learning, building awareness, encouraging sensitivity to nature, and supporting healthy styles of living. The instructor’s manual has a unified structure, which makes it simple to utilize. Its proposals and advice are clear. The advanced version helps educators in their planning and execution activities.

The material seriously assesses intercultural mindfulness and sensitivity. The gender description is balanced; the two personalities highlighted in the textbook support this methodology. Vaquero-Solís et al. found that mixed procedures in their interventions, executed using a new methodology, greatly affected the participants [ 30 ]. Once each month, the standard methodology was applied, during which the change from hypothesis to practice was continuous. During the first exercise of the month, the material in the textbook was analysed for the future, and undertakings for the month were presented. The hypothesis was set up during practical sessions. During the hypothetical exercises, the children additionally had the chance to move around, practising the physical tasks given in the textbook. During the last exercise of the month, the tasks introduced in the textbook were performed; the activities of the month were rehashed, recalled, summed up, and assessed; and the assignment of children’s notes were performed. Children from the control group attended unmodified physical education exercises.

2.4. Data Analysis

Graphic statistics are presented for all methodical factors as the mean ± SD. The impact size of the Mann–Whitney U test was determined using the equation r = Z / N , where Z is the z-score and N is the total size of the sample (small: 0.1; medium: 0.3; large: 0.5). Statistical significance was defined as p ≤ 0.05 for all analyses. Analyses were carried out by utilizing the SPSS 23 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3.1. Physical Activity of 6–7- and 8–9-Year-Old Children in the Experimental Group

Analysing the physical activity pre-test results of the 6–7- and 8–9-year-old children, it turned out that both the First Grade (92.15 MET, min/week) and Second Grade (97.50 MET, min/week) children in the experimental group were physically active during physical education lessons. The analysis of physical activity types, such as cycling to school, showed no differences in age, according to the MET; however, there were differences in walking to school—First Grade (15.98 MET, min/week) and Second Grade (23.50 MET, min/week)—in terms of age, according to the MET. In the context of average physical activity, a higher indicator (805.95 MET, min/week) was detected in the First Grade of the experimental group, in comparison with the Second Grade (1072.12 MET, min/week). Statistically significant differences were found in average MET for the First Grade (931.60 MET, min/week), in comparison with the Second Grade (1211.55 MET, min/week; p < 0.05, Table 3 ). The post-test of the First Grade (115.83 MET, min/week) experimental group was carried out to analyse average physical activity, in comparison with the Second Grade experimental group (130.01 MET, min/week), during physical education lessons. In the post-test, walking to school—First Grade (16.07 MET, min/week) and Second Grade (30.37 MET, min/week)—showed differences in age, according to the MET. Statistically significant differences were found during the analysis of average MET for the First Grade (1108.41 MET, min/week), in comparison with the Second Grade (1453.62 MET, min/week; p < 0.05, Table 3 ). We found a statistically significant difference between experimental and control groups ( p < 0.05) and between pre- and post-test.

Physical activity levels determined using the MET method.

Note. *, p < 0.05 (according to the Mann–Whitney U test) between physical activity types; # , p < 0.05 (according to the Mann–Whitney U test) between experimental and control groups; $ , p < 0.05 (according to the Mann–Whitney U test) between First and Second Grades; § , p < 0.05 (according to the Mann–Whitney U test) between pre-test and post-test.

3.2. Physical Activity of 6–7- and 8–9-Year-Old Children in the Control Group

Analysing the results considering the physical activity of 6–7- and 8–9-year-old children, it turned out that in the control group, both the First Grade (91.68 MET, min/week) and Second Grade (95.87 MET, min/week) children were physically active in physical education lessons during the pre-test. The analysis of physical activity types, such as cycling to school, found no differences in age, according to the MET. We found that walking to school—First Grade (0.00 MET, min/week) and Second Grade (22.15 MET, min/week—showed differences in age, according to the MET. Statistically significant differences were found during the analysis of average MET for the First Grade in the control group (906.40 MET, min/week), compared to the Second Grade (1105.71 MET, min/week; p < 0.05, Table 4 ). The post-test results for the First Grade of the control group (98.10 MET, min/week) were determined by the analysis of average physical activity, in comparison with the Second Grade children of the same group (105.70 MET, min/week), when doing physical education lessons. Statistically significant differences were found in average MET for the First Grade (995.66 MET, min/week), in comparison with the Second Grade (1211.70 MET, min/week; p < 0.05, Table 4 ).

The physical activity level using the MET method (the pre-test/post-test results of the control group).

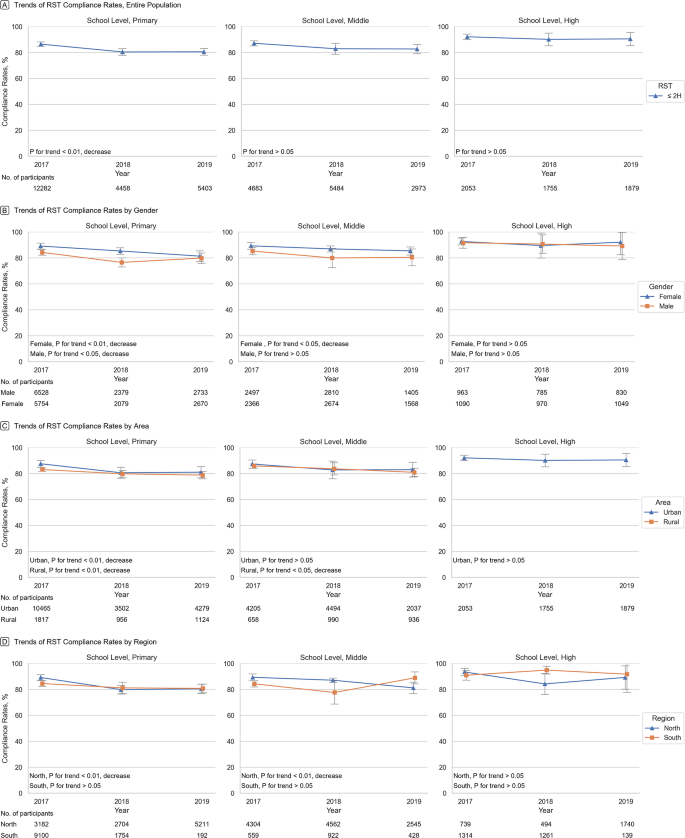

The study performed at the beginning of the experiment showed that in the pre-test, the level of somatic anxiety of the primary school children in the CG was average (4.95 ± 1.10 points). When exploring the results of the somatic anxiety in the EG (4.95 ± 1.10 points) before and after the experiment, after the intervention programme, somatic anxiety in the EG was 4.55 ± 1.00 points, indicating lower levels of depression, seclusion, somatic complaints, aggression, and delinquent behaviours (F = 4.785, p < 0.05, P = 0.540; Figure 1 a).

Pre- and post-test levels of somatic anxiety ( a ), personality anxiety ( b ), and social anxiety ( c ) in primary school children. # , p < 0.05 between experimental and control groups; $ , p < 0.05 between First and Second Grades; *, p < 0.05 between pre- and post-test.

3.3. Anxiety of 6–7-Year-Old Children (First Grade)

When dealing with the personality anxiety results, we established that in the pre- and post-tests, the results of CG students did not statistically significantly differ (3.63 ± 0.80 points and 3.48 ± 0.50 points, respectively; F = 0.139, p > 0.05, P = 0.041). When analysing EG personality anxiety results in the pre- and post-tests, after the intervention programme, the EG personality anxiety results significantly decreased (3.55 ± 1.10 points and 2.78 ± 0.90 points, respectively; F = 5.195, p < 0.05, P = 0.549; Figure 1 b).

In the pre-test, the level of social anxiety in the CG was 6.15 ± 1.30 points. The post-test CG result was statistically significantly lower (5.18 ± 1.20 points; F = 4.75, p < 0.05, P = 0.752). When analysing the levels of the social anxiety of the EG, pre- and post-test results decreased after the intervention programme (6.32 ± 1.10 points and 4.25 ± 1.40 points, respectively) and significantly differed (F = 8.029, p < 0.05, P = 0.673; Figure 1 c).

3.4. Anxiety of 8–9-Year-Old Children (Second Grade)

The research performed at the beginning of the experiment showed that in the pre-test, the level of somatic anxiety of the adolescents in the CG was average (4.63 ± 1.10 points). When exploring the somatic anxiety results in the EG (4.50 ± 0.90 points) before the experiment and after it, a decrease in somatic anxiety in the EG was established (4.10 ± 0.75 points), indicating lower levels of depression, seclusion, somatic complaints, aggression, and delinquent behaviours (F = 4.482, p < 0.05, P = 0.610; Figure 1 a).

When dealing with the personality anxiety results, we established that in the pre- and post-test, the results of CG students were not statistically significantly different (3.10 ± 0.85 points and 2.86 ± 0.67 points, respectively; F = 0.127, p > 0.05, P = 0.057). When analysing the pre- and post-test EG personality anxiety results, after the intervention programme, the EG personality anxiety results decreased (2.93 ± 0.93 points vs. 2.51 ± 1.00 points, respectively; F = 6.498, p < 0.05, P = 0.758; Figure 1 b).

In the pre-test, the level of social anxiety in the CG was 4.55 ± 1.30 points. The post-test CG result was statistically significantly lower (3.70 ± 1.40 points; F = 4.218, p < 0.05, P = 0.652). When analysing the levels of social anxiety in the EG, pre- and post-test results decreased after the intervention programme (4.65 ± 1.15 points and 3.01 ± 1.50 points, respectively) and were significantly different (F = 8.021, p < 0.05, P = 0.798; Figure 1 c).

4. Discussion

The outcomes of this study showed that the proposed procedure for a physical education program and educational model encouraging physical activity in children had an impact on three primary dimensions—somatic anxiety, personality anxiety, and social anxiety—for children aged 6–7 and 8–9 years. The procedure depended on dynamic exercise, intense motor skills reiteration, differentiation, seating and parking reduction, and physical activity dissemination in the classroom model. Following eight months of applying this study’s physical education program, anxiety decreased in the children. Schools provide an opportune site for addressing PA promotion in children. With children spending a substantial number of their waking hours during the week at school, increased opportunities for PA are needed, especially considering trends toward decreased frequency of physical education in schools [ 31 , 32 ]. Considering physical education curricula, Chen et al. [ 29 ] described the following:

- Aerobic activities: Most daily activities should be moderate- to vigorous-intensity aerobic activities, such as bicycling, playing sports and active games, and brisk walking.

- Strength training: The program should include muscle-strengthening activities at least three days a week, such as performing calisthenics, weight-bearing activities, and weight training.

- Bone strengthening: Bone-strengthening activities should also be included at least three days a week, such as jump-rope, playing tennis or badminton, and engaging in other hopping-type activities.

School-related physical activity interventions may reduce anxiety, increase resilience, improve well-being, and increase positive mental health in children and adolescents [ 33 ]. Increasing activity levels and sports participation among the least active young people should be a target of community- and school-based interventions in order to promote well-being. Frequency of physical activity has been positively correlated with well-being and negatively correlated with both anxiety and depressive symptoms, up to a threshold of moderate frequency of activity. In a multi-level mixed effects model, more frequent physical activity and participation in sport were both found to independently contribute to greater well-being and lower levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms in both sexes [ 34 ]. There does not appear to be an additional benefit to mental health associated with meeting the WHO-recommended levels of activity [ 9 ]. Physical activity interventions have been shown to have a small beneficial effect in reducing anxiety; however, the evidence base is limited. Reviews of physical activity and cognitive functioning have provided evidence that routine physical activity can be associated with improved cognitive performance and academic achievement, but these associations are usually small and inconsistent [ 35 ]. Advances in neuroscience have resulted in substantial progress in linking physical activity to cognitive performance, as well as to brain structure and function [ 36 ]. The executive functions hypothesis proposes that exercise has the potential to induce vascularization and neural growth and alter synaptic transmission in ways that alter thinking, decision making, and behaviour in those regions of the brain tied to executive functions—in particular, the pre-frontal cortices [ 37 , 38 ]. The brain may be particularly sensitive to the effects of physical activity during pre-adolescence, as the neural circuitry of the brain is still developing [ 8 ].

During their school years, about 33% of primary and secondary school students experience the adverse effects of test anxiety [ 39 ]. Anxiety is an aversive motivational state which occurs when the degree of perceived threat is viewed as high [ 40 ]. In the concept of anxiety, a frequently made differentiation is created between trait anxiety, referring to differences in personality dimensions, and state anxiety, alluding to anxiety as a transient mindset state. These two kinds of anxiety hamper performance, particularly during complex and intentionally requested assignments [ 41 ]. Mavilidi et al. [ 42 ] presented a study investigating whether a short episode of physical activity can mitigate test anxiety and improve test execution in 6th grade children (11–12 years). The discoveries of the study by the above authors expressed that, even though test anxiety was not decreased as expected, short physical activity breaks can be utilized before assessments without blocking academic performance [ 43 ].

Physical activity has been associated with physiological, developmental, mental, cognitive, and social health benefits in young people [ 36 ]. While the health benefits of physical activity are well-established, higher levels of physical activity have also been associated with enhanced academic-related outcomes, including cognitive function, classroom behaviour, and academic achievement [ 44 ]. The evidence suggests a decline in physical activity from early childhood [ 45 ]. The physical and psychological benefits of physical activity for children and adolescents include reduced adiposity and cardiometabolic risk factors, as well as improvements in musculoskeletal health and psychological well-being [ 33 , 46 , 47 ]. However, population based-studies have reported that more than half of all children internationally are not meeting the recommended levels of physical activity, with rates of compliance declining with age from the early primary school years [ 9 ]. Therefore, it is imperative to promote physical activity and intervene early in childhood, prior to such a decline in physical activity [ 48 ]. Schools are considered ideal settings for the promotion of children’s physical activity. There are multiple opportunities for children to be physically active over the course of the school week, including during break times, sport, physical education class, and active travel to and from school [ 49 ]. There exists strong evidence of the benefits of physical activity for the mental health of children and adolescents, mainly in terms of depression, anxiety, self-esteem, and cognitive functioning [ 35 ].

Physiological adaptation (e.g., hormonal regulation) of the body during physical exercise can be applied additionally to psychosocial stressors, thus improving mental health [ 48 ]. Subsequently, it has been stated that intense physical activity which improves health-related fitness may be expected to evoke neurobiological changes affecting psychological and academic performance [ 43 ].

The results of this review contribute to knowledge about the multifaceted interactions influencing how physical activity can be enhanced within a school setting, given certain contexts. Evidence has indicated that school-based interventions can be effective in enhancing physical activity, cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness, psychosocial outcomes associated with physical activity (e.g., enjoyment), and other markers of health status in children. School- and community-based physical activity interventions, as part of an obesity prevention or treatment programme, can benefit the executive functions of children, specifically those with obesity or who are overweight [ 46 ]. Considering the positive effects of physical activity on health in general, these findings may reinforce school-based initiatives to increase physical activity [ 34 ]. This involves classroom teachers incorporating physical activity into class time, either by integrating physical activity into physically active lessons, or adding short bursts of physical activity with curriculum-focused active breaks [ 50 , 51 ]. It is widely accepted that physical inactivity is an important risk factor for chronic diseases; prevention strategies should begin as early as childhood, as the prevalence of physical inactivity increases even more in adolescence [ 52 ]. A physically active lifestyle begins to form very early in childhood and has a positive tendency to persist throughout life [ 52 ].

We all have an important role to play in increasing children’s physical activity. Schools must promote and influence a healthy environment for children. Most primary school children spend an average of 6–7 h a day at school, which is most of their daytime. A balanced and adapted physical education lesson provides cognitive content and training for developing motor skills and knowledge in the field of physical activity. Our 8-month physical education program can give children the opportunity to increase physical activity and improve emotional well-being, which can encourage children to be physically active throughout life.

5. Conclusions

Low physical activity in children is a major societal problem. The growing number of children with obesity is a concern for doctors and scientists. The focus of our study was to improve emotional well-being and physical activity in children. Since elementary school children spend most of their day at school, physical education lessons are a great tool to increase physical activity. A balanced and adapted physical education lesson can help to draw children’s attention to the health benefits of physical activity. It was established that the properly constructed and purposefully applied 8-month physical education program had an impact on the physical activity and emotional well-being of primary school children (i.e., 6–7 and 8–9 year olds) in three main dimensions: somatic anxiety, personality anxiety, and social anxiety. Our findings suggest that the 8-month physical education program intervention is effective for increasing levels of physical activity. Changes in these activities may require more intensive behavioural interventions in children or upstream interventions at the family and societal level, as well as at the school environment level. These findings have relevance for researchers, policy makers, public health practitioners, and doctors who are involved in health promotion, policy making, and commissioning services.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.K. and S.S.; methodology, I.K.; software, R.A.; validation, G.C.; formal analysis, K.Z.; investigation, K.Z.; resources, I.K.; data curation, G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, I.K.; writing—review and editing, S.S.; visualization, G.C.; supervision, R.A.; project administration, R.A.; funding acquisition, K.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The time and place of the study, with the consent of the parents of the participants, were agreed upon in advance with the school administration. This study was approved by the research ethics committee of Kaunas University of Technology, Institute of Social Science and Humanity (Protocol No V19-1253-03).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Health Education Research

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction.

- < Previous

‘Physical education makes you fit and healthy’. Physical education's contribution to young people's physical activity levels

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

S. Fairclough, G. Stratton, ‘Physical education makes you fit and healthy’. Physical education's contribution to young people's physical activity levels, Health Education Research , Volume 20, Issue 1, February 2005, Pages 14–23, https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyg101

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The purpose of this study was to assess physical activity levels during high school physical education lessons. The data were considered in relation to recommended levels of physical activity to ascertain whether or not physical education can be effective in helping young people meet health-related goals. Sixty-two boys and 60 girls (aged 11–14 years) wore heart rate telemeters during physical education lessons. Percentages of lesson time spent in moderate-and-vigorous (MVPA) and vigorous intensity physical activity (VPA) were recorded for each student. Students engaged in MVPA and VPA for 34.3 ± 21.8 and 8.3 ± 11.1% of lesson time, respectively. This equated to 17.5 ± 12.9 (MVPA) and 3.9 ± 5.3 (VPA) min. Boys participated in MVPA for 39.4 ± 19.1% of lesson time compared to the girls (29.1 ± 23.4%; P < 0.01). High-ability students were more active than the average- and low-ability students. Students participated in most MVPA during team games (43.2 ± 19.5%; P < 0.01), while the least MVPA was observed during movement activities (22.2 ± 20.0%). Physical education may make a more significant contribution to young people's regular physical activity participation if lessons are planned and delivered with MVPA goals in mind.

Regular physical activity participation throughout childhood provides immediate health benefits, by positively effecting body composition and musculo-skeletal development ( Malina and Bouchard, 1991 ), and reducing the presence of coronary heart disease risk factors ( Gutin et al. , 1994 ). In recognition of these health benefits, physical activity guidelines for children and youth have been developed by the Health Education Authority [now Health Development Agency (HDA)] ( Biddle et al. , 1998 ). The primary recommendation advocates the accumulation of 1 hour's physical activity per day of at least moderate intensity (i.e. the equivalent of brisk walking), through lifestyle, recreational and structured activity forms. A secondary recommendation is that children take part in activities that help develop and maintain musculo-skeletal health, on at least two occasions per week ( Biddle et al. , 1998 ). This target may be addressed through weight-bearing activities that focus on developing muscular strength, endurance and flexibility, and bone health.

School physical education (PE) provides a context for regular and structured physical activity participation. To this end a common justification for PE's place in the school curriculum is that it contributes to children's health and fitness ( Physical Education Association of the United Kingdom, 2004 ; Zeigler, 1994 ). The extent to which this rationale is accurate is arguable ( Koslow, 1988 ; Michaud and Andres, 1990 ) and has seldom been tested. However, there would appear to be some truth in the supposition because PE is commonly highlighted as a significant contributor to help young people achieve their daily volume of physical activity ( Biddle et al. , 1998 ; Corbin and Pangrazi, 1998 ). The important role that PE has in promoting health-enhancing physical activity is exemplified in the US ‘Health of the Nation’ targets. These include three PE-associated objectives, two of which relate to increasing the number of schools providing and students participating in daily PE classes. The third objective is to improve the number of students who are engaged in beneficial physical activity for at least 50% of lesson time ( US Department of Health and Human Services, 2000 ). However, research evidence suggests that this criterion is somewhat ambitious and, as a consequence, is rarely achieved during regular PE lessons ( Stratton, 1997 ; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2000 ; Levin et al. , 2001 ; Fairclough, 2003a ).

The potential difficulties of achieving such a target are associated with the diverse aims of PE. These aims are commonly accepted by physical educators throughout the world ( International Council of Sport Science and Physical Education, 1999 ), although their interpretation, emphasis and evaluation may differ between countries. According to Simons-Morton ( Simons-Morton, 1994 ), PE's overarching goals should be (1) for students to take part in appropriate amounts of physical activity during lessons, and (2) become educated with the knowledge and skills to be physically active outside school and throughout life. The emphasis of learning during PE might legitimately focus on motor, cognitive, social, spiritual, cultural or moral development ( Sallis and McKenzie, 1991 ; Department for Education and Employment/Qualifications and Curriculum Authority, 1999 ). These aspects may help cultivate students' behavioural and personal skills to enable them to become lifelong physical activity participants [(thus meeting PE goal number 2 ( Simons-Morton, 1994 )]. However, to achieve this, these aspects should be delivered within a curriculum which provides a diverse range of physical activity experiences so students can make informed decisions about which ones they enjoy and feel competent at. However, evidence suggests that team sports dominate English PE curricula, yet bear limited relation to the activities that young people participate in, out of school and after compulsory education ( Sport England, 2001 ; Fairclough et al. , 2002 ). In order to promote life-long physical activity a broader base of PE activities needs to be offered to reinforce the fact that it is not necessary for young people to be talented sportspeople to be active and healthy.

While motor, cognitive, social, spiritual, cultural and moral development are valid areas of learning, they can be inconsistent with maximizing participation in health-enhancing physical activity [i.e. PE goal number 1 ( Simons-Morton, 1994 )]. There is no guidance within the English National Curriculum for PE [NCPE ( Department for Education and Employment/Qualifications and Curriculum Authority, 1999 )] to inform teachers how they might best work towards achieving this goal. Moreover, it is possible that the lack of policy, curriculum development or teacher expertise in this area contributes to the considerable variation in physical activity levels during PE ( Stratton, 1996a ). However, objective research evidence suggests that this is mainly due to differences in pedagogical variables [i.e. class size, available space, organizational strategies, teaching approaches, lesson content, etc. ( Borys, 1983 ; Stratton, 1996a )]. Furthermore, PE activity participation may be influenced by inter-individual factors. For example, activity has been reported to be lower among students with greater body mass and body fat ( Brooke et al. , 1975 ; Fairclough, 2003c ), and higher as students get older ( Seliger et al. , 1980 ). In addition, highly skilled students are generally more active than their lesser skilled peers ( Li and Dunham, 1993 ; Stratton, 1996b ) and boys tend to engage in more PE activity than girls ( Stratton, 1996b ; McKenzie et al. , 2000 ). Such inter-individual factors are likely to have significant implications for pedagogical practice and therefore warrant further investigation.

In accordance with Simons-Morton's ( Simons-Morton, 1994 ) first proposed aim of PE, the purpose of this study was to assess English students' physical activity levels during high school PE. The data were considered in relation to recommended levels of physical activity ( Biddle et al. , 1998 ) to ascertain whether or not PE can be effective in helping children be ‘fit and healthy’. Specific attention was paid to differences between sex and ability groups, as well as during different PE activities.

Subjects and settings

One hundred and twenty-two students (62 boys and 60 girls) from five state high schools in Merseyside, England participated in this study. Stage sampling was used in each school to randomly select one boys' and one girls' PE class, in each of Years 7 (11–12 years), 8 (12–13 years) and 9 (13–14 years). Three students per class were randomly selected to take part. These students were categorized as ‘high’, ‘average’ and ‘low’ ability, based on their PE teachers' evaluation of their competence in specific PE activities. Written informed consent was completed prior to the study commencing. The schools taught the statutory programmes of study detailed in the NCPE, which is organized into six activity areas (i.e. athletic activities, dance, games, gymnastic activities, outdoor activities and swimming). The focus of learning is through four distinct aspects of knowledge, skills and understanding, which relate to; skill acquisition, skill application, evaluation of performance, and knowledge and understanding of fitness and health ( Department for Education and Employment/Qualifications and Curriculum Authority, 1999 ). The students attended two weekly PE classes in mixed ability, single-sex groups. Girls and boys were taught by male and female specialist physical educators, respectively.

Instruments and procedures

The investigation received ethical approval from the Liverpool John Moores Research Degrees Ethics Committee. The study involved the monitoring of heart rates (HRs) during PE using short-range radio telemetry (Vantage XL; Polar Electro, Kempele, Finland). Such systems measure the physiological load on the participants' cardiorespiratory systems, and allow analysis of the frequency, duration and intensity of physical activity. HR telemetry has been shown to be a valid and reliable measure of young people's physical activity ( Freedson and Miller, 2000 ) and has been used extensively in PE settings ( Stratton, 1996a ).

The students were fitted with the HR telemeters while changing into their PE uniforms. HR was recorded once every 5 s for the duration of the lessons. Telemeters were set to record when the teachers officially began the lessons, and stopped at the end of lessons. Total lesson ‘activity’ time was the equivalent of the total recorded time on the HR receiver. At the end of the lessons the telemeters were removed and data were downloaded for analyses. Resting HRs were obtained on non-PE days while the students lay in a supine position for a period of 10 min. The lowest mean value obtained over 1 min represented resting HR. Students achieved maximum HR values following completion of the Balke treadmill test to assess cardiorespiratory fitness ( Rowland, 1993 ). This data was not used in the present study, but was collated for another investigation assessing children's health and fitness status. Using the resting and maximum HR values, HR reserve (HRR, i.e. the difference between resting and maximum HR) at the 50% threshold was calculated for each student. HRR accounts for age and gender HR differences, and is recommended when using HR to assess physical activity in children ( Stratton, 1996a ). The 50% HRR threshold represents moderate intensity physical activity ( Stratton, 1996a ), which is the minimal intensity required to contribute to the recommended volume of health-related activity ( Biddle et al. , 1998 ). Percentage of lesson time spent in health enhancing moderate-and-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) was calculated for each student by summing the time spent ≥50% HRR threshold. HRR values ≥75% corresponded to vigorous intensity physical activity (VPA). This threshold represents the intensity that may stimulate improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness ( Morrow and Freedson, 1994 ) and was used to indicate the proportion of lesson time that students were active at this higher level.

Sixty-six lessons were monitored over a 12-week period, covering a variety of group and individual activities ( Table I ). In order to allow statistically meaningful comparisons between different types of activities, students were classified as participants in activities that shared similar characteristics. These were, team games [i.e. invasion (e.g. football and hockey) and striking games (e.g. cricket and softball)], individual games (e.g. badminton, tennis and table tennis), movement activities (e.g. dance and gymnastics) and individual activities [e.g. athletics, fitness (circuit training and running activities) and swimming]. The intention was to monitor equal numbers of students during lessons in each of the four designated PE activity categories. However, timetable constraints and student absence meant that true equity was not possible, and so the number of boys and girls monitored in the different activities was unequal.

Number and type of monitored PE lessons

Student sex, ability level and PE activity category were the independent variables, with percent of lesson time spent in MVPA and VPA set as the dependent variables. Exploratory analyses were conducted to establish whether data met parametric assumptions. Shapiro–Wilk tests revealed that only boys' MVPA were normally distributed. Subsequent Levene's tests confirmed the data's homogeneity of variance, with the exception of VPA between the PE activities. Though much of the data violated the assumption of normality, the ANOVA is considered to be robust enough to produce valid results in this situation ( Vincent, 1999 ). Considering this, alongside the fact that the data had homogenous variability, it was decided to proceed with ANOVA for all analyses, with the exception of VPA between different PE activities.

Sex × ability level factorial ANOVAs compared the physical activity of boys and girls who differed in PE competence. A one-way ANOVA was used to identify differences in MVPA during the PE activities. Post-hoc analyses were performed using Hochberg's GT2 correction procedure, which is recommended when sample sizes are unequal ( Field, 2000 ). A non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA calculated differences in VPA during the different activities. Post-hoc Mann–Whitney U -tests determined where identified differences occurred. To control for type 1 error the Bonferroni correction procedure was applied to these tests, which resulted in an acceptable α level of 0.008. Although these data were ranked for the purposes of the statistical analysis, they were presented as means ± SD to allow comparison with the other results. All data were analyzed using SPSS version 11.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

The average duration of PE lessons was 50.6 ± 20.8 min, although girls' (52.6 ± 25.4 min) lessons generally lasted longer than boys' (48.7 ± 15.1 min). When all PE activities were considered together, students engaged in MVPA and VPA for 34.3 ± 21.8 and 8.3 ± 11.1% of PE time, respectively. This equated to 17.5 ± 12.9 (MVPA) and 3.9 ± 5.3 (VPA) min. The high-ability students were more active than the average- and low-ability students, who took part in similar amounts of activity. These trends were apparent in boys and girls ( Table II ).

Mean (±SD) MVPA and VPA of boys and girls of differing abilities

Boys > girls, P < 0.01.

Boys > girls, P < 0.05.

Boys engaged in MVPA for 39.4% ± 19.1 of lesson time compared to the girls' value of 29.1 ± 23.4 [ F (1, 122) = 7.2, P < 0.01]. When expressed as absolute units of time, these data were the equivalent of 18.9 ± 10.5 (boys) and 16.1 ± 14.9 (girls) min. Furthermore, a 4% difference in VPA was observed between the two sexes [ Table II ; F (1, 122) = 4.6, P < 0.05]. There were no significant sex × ability interactions for either MVPA or VPA.

Students participated in most MVPA during team games [43.2 ± 19.5%; F (3, 121) = 6.0, P < 0.01]. Individual games and individual activities provided a similar stimulus for activity, while the least MVPA was observed during movement activities (22.2 ± 20.0%; Figure 1 ). A smaller proportion of PE time was spent in VPA during all activities. Once more, team games (13.6 ± 11.3%) and individual activities (11.8 ± 14.0%) were best suited to promoting this higher intensity activity (χ 2 (3) =30.0, P < 0.01). Students produced small amounts of VPA during individual and movement activities, although this varied considerably in the latter activity ( Figure 2 ).

Mean (±SD) MVPA during different PE activities. ** Team games > movement activities ( P < 0.01). * Individual activities > movement activities ( P < 0.05).

Mean (±SD) VPA during different PE activities. ** Team games > movement activities ( Z (3) = −4.9, P < 0.008) and individual games ( Z (3) = −3.8, P < 0.008). † Individual activities > movement activities ( Z (3) = −3.3, P < 0.008). ‡ Individual game > movement activities ( Z (3) = −2.7, P < 0.008).

This study used HR telemetry to assess physical activity levels during a range of high school PE lessons. The data were considered in relation to recommended levels of physical activity ( Biddle et al. , 1998 ) to investigate whether or not PE can be effective in helping children be ‘fit and healthy’. Levels of MVPA were similar to those reported in previous studies ( Klausen et al. , 1986 ; Strand and Reeder, 1993 ; Fairclough, 2003b ) and did not meet the US Department of Health and Human Services ( US Department of Health and Human Services, 2000 ) 50% of lesson time criterion. Furthermore, the data were subject to considerable variance, which was exemplified by high standard deviation values ( Table II , and Figures 1 and 2 ). Such variation in activity levels reflects the influence of PE-specific contextual and pedagogical factors [i.e. lesson objectives, content, environment, teaching styles, etc. ( Stratton, 1996a )]. The superior physical activity levels of the high-ability students concurred with previous findings ( Li and Dunham, 1993 ; Stratton, 1996b ). However, the low-ability students engaged in more MVPA and VPA than the average-ability group. While it is possible that the teachers may have inaccurately assessed the low and average students' competence, it could have been that the low-ability group displayed more effort, either because they were being monitored or because they associated effort with perceived ability ( Lintunen, 1999 ). However, these suggestions are speculative and are not supported by the data. The differences in activity levels between the ability groups lend some support to the criticism that PE teachers sometimes teach the class as one and the same rather than planning for individual differences ( Metzler, 1989 ). If this were the case then undifferentiated activities may have been beyond the capability of the lesser skilled students. This highlights the importance of motor competence as an enabling factor for physical activity participation. If a student is unable to perform the requisite motor skills to competently engage in a given task or activity, then their opportunities for meaningful participation become compromised ( Rink, 1994 ). Over time this has serious consequences for the likelihood of a young person being able or motivated enough to get involved in physical activity which is dependent on a degree of fundamental motor competence.

Boys spent a greater proportion of lesson time involved in MVPA and VPA than girls. These differences are supported by other HR studies in PE ( Mota, 1994 ; Stratton, 1997 ). Boys' activity levels equated to 18.9 min of MVPA, compared to 16.1 min for the girls. It is possible that the characteristics and aims of some of the PE activities that the girls took part in did not predispose them to engage in whole body movement as much as the boys. Specifically, the girls participated in 10 more movement lessons and eight less team games lessons than the boys. The natures of these two activities are diverse, with whole body movement at differing speeds being the emphasis during team games, compared to aesthetic awareness and control during movement activities. The monitored lessons reflected typical boys' and girls' PE curricula, and the fact that girls do more dance and gymnastics than boys inevitably restricts their MVPA engagement. Although unrecorded contextual factors may have contributed to this difference, it is also possible that the girls were less motivated than the boys to physically exert themselves. This view is supported by negative correlations reported between girls' PE enjoyment and MVPA ( Fairclough, 2003b ). Moreover, there is evidence ( Dickenson and Sparkes, 1988 ; Goudas and Biddle, 1993 ) to suggest that some pupils, and girls in particular ( Cockburn, 2001 ), may dislike overly exerting themselves during PE. Although physical activity is what makes PE unique from other school subjects, some girls may not see it as such an integral part of their PE experience. It is important that this perception is clearly recognized if lessons are to be seen as enjoyable and relevant, whilst at the same time contributing meaningfully to physical activity levels. Girls tend to be habitually less active than boys and their levels of activity participation start to decline at an earlier age ( Armstrong and Welsman, 1997 ). Therefore, the importance of PE for girls as a means of them experiencing regular health-enhancing physical activity cannot be understated.

Team games promoted the highest levels of MVPA and VPA. This concurs with data from previous investigations ( Strand and Reeder, 1993 ; Stratton, 1996a , 1997 ; Fairclough, 2003a ). Because these activities require the use of a significant proportion of muscle mass, the heart must maintain the oxygen demand by beating faster and increasing stroke volume. Moreover, as team games account for the majority of PE curriculum time ( Fairclough and Stratton, 1997 ; Sport England, 2001 ), teachers may actually be more experienced and skilled at delivering quality lessons with minimal stationary waiting and instruction time. Similarly high levels of activity were observed during individual activities. With the exception of throwing and jumping themes during athletics lessons, the other individual activities (i.e. swimming, running, circuit/station work) involved simultaneous movement of the arms and legs over variable durations. MVPA and VPA were lowest during movement activities, which mirrored previous research involving dance and gymnastics ( Stratton, 1997 ; Fairclough, 2003a ). Furthermore, individual games provided less opportunity for activity than team games. The characteristics of movement activities and individual games respectively emphasize aesthetic appreciation and motor skill development. This can mean that opportunities to promote cardiorespiratory health may be less than in other activities. However, dance and gymnastics can develop flexibility, and muscular strength and endurance. Thus, these activities may be valuable to assist young people in meeting the HDA's secondary physical activity recommendation, which relates to musculo-skeletal health ( Biddle et al. , 1998 ).

The question of whether PE can solely contribute to young people's cardiorespiratory fitness was clearly answered. The students engaged in small amounts of VPA (4.5 and 3.3 min per lesson for boys and girls, respectively). Combined with the limited frequency of curricular PE, these were insufficient durations for gains in cardiorespiratory fitness to occur ( Armstrong and Welsman, 1997 ). Teachers who aim to increase students' cardiorespiratory fitness may deliver lessons focused exclusively on high intensity exercise, which can effectively increase HR ( Baquet et al. , 2002 ), but can sometimes be mundane and have questionable educational value. Such lessons may undermine other efforts to promote physical activity participation if they are not delivered within an enjoyable, educational and developmental context. It is clear that high intensity activity is not appropriate for all pupils, and so opportunities should be provided for them to be able to work at developmentally appropriate levels.

Students engaged in MVPA for around 18 min during the monitored PE lessons. This approximates a third of the recommended daily hour ( Biddle et al. , 1998 ). When PE activity is combined with other forms of physical activity support is lent to the premise that PE lessons can directly benefit young people's health status. Furthermore, for the very least active children who should initially aim to achieve 30 min of activity per day ( Biddle et al. , 1998 ), PE can provide the majority of this volume. However, a major limitation to PE's utility as a vehicle for physical activity participation is the limited time allocated to it. The government's aspiration is for all students to receive 2 hours of PE per week ( Department for Education and Employment/Qualifications and Curriculum Authority, 1999 ), through curricular and extra-curricular activities. While some schools provide this volume of weekly PE, others are unable to achieve it ( Sport England, 2001 ). The HDA recommend that young people strive to achieve 1 hour's physical activity each day through many forms, a prominent one of which is PE. The apparent disparity between recommended physical activity levels and limited curriculum PE time serves to highlight the complementary role that education, along with other agencies and voluntary organizations must play in providing young people with physical activity opportunities. Notwithstanding this, increasing the amount of PE curriculum time in schools would be a positive step in enabling the subject to meet its health-related goals. Furthermore, increased PE at the expense of time in more ‘academic’ subjects has been shown not to negatively affect academic performance ( Shephard, 1997 ; Sallis et al. , 1999 ; Dwyer et al. , 2001 ).

Physical educators are key personnel to help young people achieve physical activity goals. As well as their teaching role they are well placed to encourage out of school physical activity, help students become independent participants and inform them about initiatives in the community ( McKenzie et al. , 2000 ). Also, they can have a direct impact by promoting increased opportunities for physical activity within the school context. These could include activities before school ( Strand et al. , 1994 ), during recess ( Scruggs et al. , 2003 ), as well as more organized extra-curricular activities at lunchtime and after school. Using time in this way would complement PE's role by providing physical activity opportunities in a less structured and pedagogically constrained manner.

This research measured student activity levels during ‘typical’, non-intensified PE lessons. In this sense it provided a representative picture of the frequency, intensity and duration of students' physical activity engagement during curricular PE. However, some factors should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the data were cross-sectional and collected over a relatively short time frame. Tracking students' activity levels over a number of PE activities may have allowed a more accurate account of how physical activity varies in different aspects of the curriculum. Second, monitoring a larger sample of students over more lessons may have enabled PE activities to be categorized into more homogenous groups. Third, monitoring lessons in schools from a wider geographical area may have enabled stronger generalization of the results. Fourth, it is possible that the PE lessons were taught differently, and that the students acted differently as a result of being monitored and having the researchers present during lessons. As this is impossible to determine, it is unknown how this might have affected the results. Fifth, HR telemetry does not provide any contextual information about the monitored lessons. Also, HR is subject to emotional and environmental factors when no physical activity is occurring. Future work should combine objective physical activity measurement with qualitative or quantitative methods of observation.

During PE, students took part in health-enhancing activity for around one third of the recommended 1-hour target ( Biddle et al. , 1998 ). PE obviously has potential to help meet this goal. However, on the basis of these data, combined with the weekly frequency of PE lessons, it is clear that PE can only do so much in supplementing young people's daily volume of physical activity. Students need to be taught appropriate skills, knowledge and understanding if they are to optimize their physical activity opportunities in PE. For improved MVPA levels to occur, health-enhancing activity needs to be recognized as an important element of lessons. PE may make a more significant contribution to young people's regular physical activity participation if lessons are planned and delivered with MVPA goals in mind.

Armstrong, N. and Welsman, J.R. ( 1997 ) Young People and Physical Activity , Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Baquet, G., Berthoin, S. and Van Praagh, E. ( 2002 ) Are intensified physical education sessions able to elicit heart rate at a sufficient level to promote aerobic fitness in adolescents? Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport , 73 , 282 –288.

Biddle, S., Sallis, J.F. and Cavill, N. (eds) ( 1998 ) Young and Active? Young People and Health-Enhancing Physical Activity—Evidence and Implications. Health Education Authority, London.

Borys, A.H. ( 1983 ) Increasing pupil motor engagement time: case studies of student teachers. In Telema, R. (ed.), International Symposium on Research in School Physical Education. Foundation for Promotion of Physical Culture and Health, Jyvaskyla, pp. 351–358.

Brooke, J., Hardman, A. and Bottomly, F. ( 1975 ) The physiological load of a netball lesson. Bulletin of Physical Education , 11 , 37 –42.

Cockburn, C. ( 2001 ) Year 9 girls and physical education: a survey of pupil perceptions. Bulletin of Physical Education , 37 , 5 –24.

Corbin, C.B. and Pangrazi, R.P. ( 1998 ) Physical Activity for Children: A Statement of Guidelines. NASPE Publications, Reston, VA.

Department for Education and Employment/Qualifications and Curriculum Authority ( 1999 ) Physical Education—The National Curriculum for England. DFEE/QCA, London.

Dickenson, B. and Sparkes, A. ( 1988 ) Pupil definitions of physical education. British Journal of Physical Education Research Supplement , 2 , 6 –7.

Dwyer, T., Sallis, J.F., Blizzard, L., Lazarus, R. and Dean, K. ( 2001 ) Relation of academic performance to physical activity and fitness in children. Pediatric Exercise Science , 13 , 225 –237.

Fairclough, S. ( 2003 a) Physical activity levels during key stage 3 physical education. British Journal of Teaching Physical Education , 34 , 40 –45.

Fairclough, S. ( 2003 b) Physical activity, perceived competence and enjoyment during high school physical education. European Journal of Physical Education , 8 , 5 –18.

Fairclough, S. ( 2003 c) Girls' physical activity during high school physical education: influences of body composition and cardiorespiratory fitness. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education , 22 , 382 –395.

Fairclough, S. and Stratton, G. ( 1997 ) Physical education curriculum and extra-curriculum time: a survey of secondary schools in the north-west of England. British Journal of Physical Education , 28 , 21 –24.

Fairclough, S., Stratton, G. and Baldwin, G. ( 2002 ) The contribution of secondary school physical education to lifetime physical activity. European Physical Education Review , 8 , 69 –84.

Field, A. ( 2000 ) Discovering Statistics using SPSS for Windows. Sage, London.

Freedson, P.S. and Miller, K. ( 2000 ) Objective monitoring of physical activity using motion sensors and heart rate. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport , 71 (Suppl.), S21 –S29.

Goudas, M. and Biddle, S. ( 1993 ) Pupil perceptions of enjoyment in physical education. Physical Education Review , 16 , 145 –150.

Gutin, B., Islam, S., Manos, T., Cucuzzo, N., Smith, C. and Stachura, M.E. ( 1994 ) Relation of body fat and maximal aerobic capacity to risk factors for atherosclerosis and diabetes in black and white seven-to-eleven year old children. Journal of Pediatrics , 125 , 847 –852.

International Council of Sport Science and Physical Education ( 1999 ) Results and Recommendations of the World Summit on Physical Education , Berlin, November.

Klausen, K., Rasmussen, B. and Schibye, B. ( 1986 ) Evaluation of the physical activity of school children during a physical education lesson. In Rutenfranz, J., Mocellin, R. and Klint, F. (eds), Children and Exercise XII. Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL, pp. 93–102.

Koslow, R. ( 1988 ) Can physical fitness be a primary objective in a balanced PE program? Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance , 59 , 75 –77.

Levin, S., McKenzie, T.L., Hussey, J., Kelder, S.H. and Lytle, L. ( 2001 ) Variability of physical activity during physical education lesson across school grades. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science , 5 , 207 –218.

Li, X. and Dunham, P. ( 1993 ) Fitness load and exercise time in secondary physical education classes. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education , 12 , 180 –187.

Lintunen, T. ( 1999 ) Development of self-perceptions during the school years. In Vanden Auweele, Y., Bakker, F., Biddle, S., Durand, M. and Seiler, R. (eds), Psychology for Physical Educators. Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL, pp. 115–134.

Malina, R.M. and Bouchard, C. ( 1991 ) Growth , Maturation and Physical Activity . Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL.

McKenzie, T.L., Marshall, S.J., Sallis, J.F. and Conway, T.L. ( 2000 ). Student activity levels, lesson context and teacher behavior during middle school physical education. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport , 71 , 249 –259.

Metzler, M.W. ( 1989 ) A review of research on time in sport pedagogy. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education , 8 , 87 –103.

Michaud, T.J. and Andres, F.F. ( 1990 ) Should physical education programs be responsible for making our youth fit? Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance , 61 , 32 –35.

Morrow, J. and Freedson, P. ( 1994 ) Relationship between habitual physical activity and aerobic fitness in adolescents. Pediatric Exercise Science , 6 , 315 –329.

Mota, J. ( 1994 ) Children's physical education activity, assessed by telemetry. Journal of Human Movement Studies , 27 , 245 –250.

Physical Education Association of the United Kingdom ( 2004 ) PEA UK Policy on the Physical Education Curriculum . Available: http://www.pea.uk.com/menu.html ; retrieved: 28 April, 2004.

Rink, J.E. ( 1994 ) Fitting fitness into the school curriculum. In Pate, R.R. and Hohn, R.C. (eds), Health and Fitness Through Physical Education. Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL, pp. 67–74.

Rowland, T.W. ( 1993 ) Pediatric Laboratory Exercise Testing . Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL.

Sallis, J.F., McKenzie, R.D., Kolody, B., Lewis, S., Marshall, S.J. and Rosengard, P. ( 1999 ) Effects of health-related physical education on academic achievement: Project SPARK. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport , 70 , 127 –134.

Sallis, J.F. and McKenzie, T.L. ( 1991 ) Physical education's role in public health. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport , 62 , 124 –137.

Scruggs, P.W., Beveridge, S.K. and Watson, D.L. ( 2003 ) Increasing children's school time physical activity using structured fitness breaks. Pediatric Exercise Science , 15 , 156 –169.

Seliger, V., Heller, J., Zelenka, V., Sobolova, V., Pauer, M., Bartunek, Z. and Bartunkova, S. ( 1980 ) Functional demands of physical education lessons. In Berg, K. and Eriksson, B.O. (eds), Children and Exercise IX . University Park Press, Baltimore, MD, vol. 10, pp. 175–182.

Shephard, R.J. ( 1997 ) Curricular physical activity and academic performance. Pediatric Exercise Science , 9 , 113 –126.

Simons-Morton, B.G. ( 1994 ) Implementing health-related physical education. In Pate, R.R. and Hohn, R.C. (eds), Health and Fitness Through Physical Education. Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL, pp. 137–146.

Sport England ( 2001 ) Young People and Sport in England 1999 . Sport England, London.

Strand, B. and Reeder, S. ( 1993 ) Analysis of heart rate levels during middle school physical education activities. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance , 64 , 85 –91.

Strand, B., Quinn, P.B., Reeder, S. and Henke, R. ( 1994 ) Early bird specials and ten minute tickers. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance , 65 , 6 –9.

Stratton, G. ( 1996 a) Children's heart rates during physical education lessons: a review. Pediatric Exercise Science , 8 , 215 –233.

Stratton, G. ( 1996 b) Physical activity levels of 12–13 year old schoolchildren during European handball lessons: gender and ability group differences. European Physical Education Review , 2 , 165 –173.

Stratton, G. ( 1997 ) Children's heart rates during British physical education lessons, Journal of Teaching in Physical Education . 16 , 357 –367.

US Department of Health and Human Services ( 2000 ) Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health . USDHHS, Washington DC.

Vincent, W. ( 1999 ) Statistics in Kinesiology , Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL.

Zeigler, E. ( 1994 ) Physical education's 13 principal principles. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance , 65 , 4 –5.

Author notes

1REACH Group and School of Physical Education, Sport and Dance, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool L17 6BD and 2REACH Group and Research Institute for Sport and Exercise Sciences, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool L3 2ET, UK

- physical activity

- valproic acid

- physical education

- high schools

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1465-3648

- Print ISSN 0268-1153

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 17 December 2020

Physical education class participation is associated with physical activity among adolescents in 65 countries

- Riaz Uddin 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Jo Salmon 1 ,

- Sheikh Mohammed Shariful Islam 1 , 3 &

- Asaduzzaman Khan 2 , 3

Scientific Reports volume 10 , Article number: 22128 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

26 Citations

99 Altmetric

Metrics details

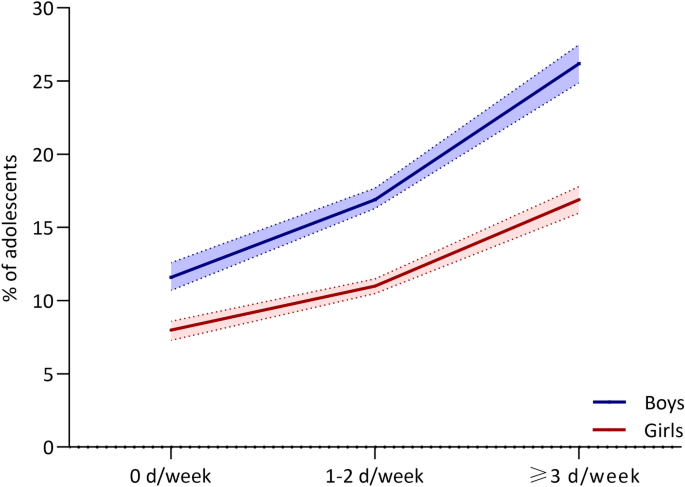

- Health services

- Paediatric research

- Public health

In this study we examined the associations of physical education class participation with physical activity among adolescents. We analysed the Global School-based Student Health Survey data from 65 countries (N = 206,417; 11–17 years; 49% girls) collected between 2007 and 2016. We defined sufficient physical activity as achieving physical activities ≥ 60 min/day, and grouped physical education classes as ‘0 day/week’, ‘1–2 days/week’, and ‘ ≥ 3 days/week’ participation. We used multivariable logistic regression to obtain country-level estimates, and meta-analysis to obtain pooled estimates. Compared to those who did not take any physical education classes, those who took classes ≥ 3 days/week had double the odds of being sufficiently active (OR 2.05, 95% CI 1.84–2.28) with no apparent gender/age group differences. The association estimates decreased with higher levels of country’s income with OR 2.37 (1.51–3.73) for low-income and OR 1.85 (1.52–2.37) for high-income countries. Adolescents who participated in physical education classes 1–2 days/week had 26% higher odds of being sufficiently active with relatively higher odds for boys (30%) than girls (15%). Attending physical education classes was positively associated with physical activity among adolescents regardless of sex or age group. Quality physical education should be encouraged to promote physical activity of children and adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Temporal dynamics of the multi-omic response to endurance exercise training

Skeletal muscle energy metabolism during exercise