World Hunger Essay: Causes of World Hunger & How to Solve It

World hunger essay introduction, history of world hunger, statistics of the world hunger, causes of the world hunger, impacts of world hunger, responses to world hunger, recommended solutions, world hunger essay conclusion.

World hunger is one of the best topics to write about. You can discuss its causes, how to solve it, and how we can create a world without hunger. Whether you need to write an entire world hunger essay or just a conclusion or a hook, this sample will inspire you.

Hunger is a term that has been defined differently by different people due to its physiological as well as its socio economic aspects. In most cases, the term hunger has been defined in relation to food insecurity. However, according to Holben (n. d. pp. 1), hunger is usually defined as a condition that is painful or uneasy emanating from lack of food.

In the same studies, hunger has yet been defined as persistent and involuntary inability to access food. Therefore, world hunger refers to a condition characterized by want and scarce food in the whole world. Technically, hunger refers to malnutrition a condition that is marked by lack of some, or all the nutrients that are necessary to maintain health of an individual.

There are two types of malnutrition which include micronutrient deficiency and protein energy malnutrition. It is important to note that world hunger generally refers to protein energy malnutrition which is caused by inadequacy of proteins and energy giving food. According to World Hunger education Service (2010 Para. 4), the recent statistics by Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) records that there is a total of about nine hundred and twenty five million people in the whole world who are described as hungry.

It is a serious condition since statistics indicate that the number has been on the increase since the mid twentieth center. With that background in mind, this paper shall focus on the problem of world hunger, history, statistics, impacts as well as solutions to the problem.

The problem of hunger has been persistent since early centuries given that people residing in Europe continent used to suffer from serious shortages of food. The problem intensified in the twentieth century due to increase of wars, plagues and other natural disasters like floods, famines and earth quakes. Consequently, a lot of people succumbed to malnutrition and death.

However, during the mid twentieth century and after the Second World War, food production increased by 69% and therefore, there was enough food to feed the population by (National Research Council (U.S.) Committee on Public Engineering Policy, 1975 pp. vii).

The situation of food adequacy which continued from the year 1954-1972 was as a result of various factors which were inclusive but not limited to better methods of farming, land reclamation, use of fertilizers, use of irrigation, as well as use of machines and other forms of skilled labor.

In 1970s, people thought that they could keep the problem of hunger under control by conserving environment, controlling population growth and technological development. Nevertheless, even with such optimism, studies of National Research Council (U.S.).

Committee on Public Engineering Policy (1975 pp. vii), record that by 1974, the condition had already grown out of hand because there was not only a high population growth rate, but energy was also extremely expensive. To make the matter worse, the same study records that a quarter of the total population in the world were already experiencing hunger.

Therefore, due to hunger, agencies which were dealing with the problem started to request for the intervention of the humanitarian relief as well as trying to solve the problem thorough the use of the green revolution. The problem of hunger contributed greatly to the technological development since by all costs, people had to survive. However, although agriculture continued to expand, the population continued to increase and that is why the problem of hunger has persisted throughout the twentieth century to the twenty first century.

As highlighted in the introductory part, nine million people in the world are malnourished but further studies indicate that the exact number is not known. It is important to note that though the problem of hunger is virtually everywhere in the world, most of the hunger stricken people are found in the developing countries.

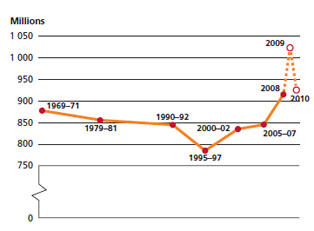

Despite the fact that the number has been on the increase since 1995, a decrease was observed in last year. The figures below clearly explain the statistical trend of world hunger from 1968 to 2009 (World Hunger Education Service, 2010 Para. 4).

Figure 1. The Number of Hunger Stricken People from 1969-2010

Source (World Hunger Education Service, 2010)

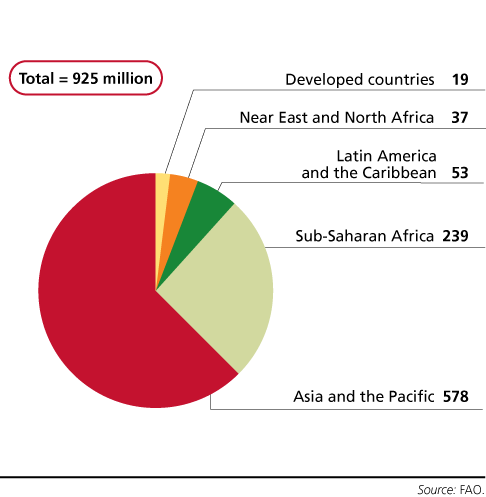

Figure 2: Distribution of Hungry People in the Whole World by Regions

Source: (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2010 pp. 2)

The above figure clearly illustrates that the problem of hunger is most common in the developing countries and less common in the developed countries. According to Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2010 pp. 2), 19 million are found in developed countries, thirty seven million in North East and North Africa, fifty three in Latin and Caribbean America, two hundred and thirty nine million in Sub Saharan Africa and five hundred and seventy eight in Asia and Pacific Region.

However, it is important to mention that the Food and Agriculture Organization arrives at the above figures by considering the total income of people and the income distribution. Therefore, the figures given are just estimates and that is the main reason why it has become increasingly difficult to get the actual number of hungry people in the whole world.

There are many causes of world hunger but poverty is the main and the same is caused by lack of enough resources as well as unequal distribution of recourses among the populations especially in the developing countries.

According to World Hunger Education Service (2010 Para 10. ), World Bank estimates that there are a bout one million, three hundred and forty five million people who are poor in the whole world since their daily expenditure is 1.25 dollars or even less. Similarly, Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that about one billion people in the whole world are under nourished.

As expected, the problem of poverty affects mostly the developing countries although there have been a lot of campaigns which have been launched with an aim of poverty reduction. Consequently in some parts Asia and China, the campaigns have been successful because the number has reduced by 19% (World Hunger Education Service, 2010 para. 12). Conversely, in some parts like the sub-Saharan Africa, the number of poor people has gone up.

Since the study has indicated that poverty is the main cause of hunger, it is important to look at the underlying cause of poverty. According to World Hunger Education Service (2010), the current economic as well as political systems in the world contribute greatly to the problem of hunger and poverty.

The main reason is due to the fact that more often than not, resources are controlled by the economic and political institutions which are controlled by the minority. Therefore, policies which emanate from poor economic systems are contributory factor to poverty and hunger.

Conflict and war is an important cause of not only poverty but also hunger. The main reason is due to the fact that conflicts lead to displacement of people and destruction of property and other resources that can be helpful in alleviating hunger. Towards the end of 2005, the number of refugees was lower compared to the current number influenced by violence and conflicts which have been taking place in Iraq as well as in Somali.

The same study clearly indicates that towards the end of the year 2008, UNHCR had recorded more than ten million refugees. A year after, internally displaced persons in the whole world had reached a total of twenty six million (World Hunger Education Service 2010 par 13). However, although it is difficult to provide the total number of internally displaced people due to conflicts, the truth is, refugees mostly suffer from poverty which exposes them to extreme hunger.

Over the last century, climate has been changing in most parts of the world, a condition which has been caused by global warming. It is a real phenomena and the effects of the same are observed in most parts of the world which are inclusive but not limited to draughts, floods, changing weather and climatic patterns as well as hurricanes (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Economic and Social Dept, 2005).

Such effects of globalization contribute greatly to hunger because they destroy the already cultivated food leading to food shortages.

Changing weather and climate patterns require a change to certain crops which is not only expensive but it also takes long to be implemented. In addition, some plants and animals have become extinct and the same contributes greatly to food shortages and hunger in general. Nonetheless, the most serious consequences of global warming are floods draughts and famines since they lead to poverty which ends up increasing people’s susceptibility to hunger. ( Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2010)

High food prices in both domestic and international markets are also a contributory factor to world hunger. Although the level of poverty is increasing because the level of income has reduced, the price of various food commodities has also gone up and therefore, it has become increasingly difficult for people to afford adequate food for their needs.

According to the studies of Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2008 pp. 24), between the year 2002 to 2007, prices of cereals such as wheat maize as well as rice increased by about fifty percent in the world market.

Nonetheless, although the world market food prices were increasing, the rate was different with domestic prices, a condition caused by the depreciating value of the US dollar while compared to other currencies in the world. However, in the year 2007 and 2008, domestic food prices in most countries also ended up increasing.

High prices in the domestic market are caused by high prices for agricultural inputs such as fertilizers and pesticides. As highlighted earlier, the need for use of advanced agricultural inputs results from the effects of global warming which is also a chief cause of world hunger and food insecurity.

There are many impacts of world hunger because food is a basic need for everyone in the society. Although impacts of hunger affect people across all the age brackets, young children are usually the worst victims. In science, the condition caused by hunger and starvation is known as under nutrition. It increases the disease burden such that in one year; under nourished children suffer from illnesses for at least five months as the condition lowers their immunity.

In most cases, undernourishment is the underlying cause of various diseases that affect children like malaria, measles, diarrhea and pneumonia. Studies of World Hunger Education Service (2010 par. 10) indicate that malnutrition is the underlying cause of more than half of all the cases of malaria diarrhea and pneumonia in young children. In measles, the same studies indicate that forty five percent of all the cases result from malnutrition.

As the problem of hunger, malnutrition is unequally distributed in the world because about thirty two percent of the stunted children live in the developing countries. Seventy percent of the total number of the malnourished children is found in Asia while Africa hosts 26% and the remaining four percent are from Caribbean and Latin America (World Hunger Education Service, 2010 par 11).

The study points out that the problem starts even before birth because in most cases, pregnant mothers are also usually undernourished. Due to this problem, in every six infants, one is usually undernourished. Apart from death, under nourishment resulting from hunger also causes blindness, difficulties in learning, stunted growth, retardation and poor health, to name just a few.

Apart from disease, poverty is also a resultant factor of hunger. In reference to the definition of hunger as an uncomfortable condition resulting from lack of food, hungry people are usually incapacitated. Since food is an important source of energy, people suffering from hunger are usually not in a position to take part in useful economic activities and a result, they are usually poor.

In addition, hunger is one of the reasons that cause people to migrate from one place to another there by causing economic constraints to the host countries. Conflicts also emanate from the same as people compete for scarce resources. A lot of humanitarian agencies use most of their funds in proving food to the people suffering from hunger either in refugee camps or in other places.

As a result, governments spend a lot of money in providing humanitarian support while the same amount of money could have been used in development projects. Impacts of hunger are mostly felt in the developing countries, Asia and Sub Saharan Africa because in most cases, the problem of hunger in such regions is usually an international problem because regional governments cannot be able to deal with it single handedly ( World Vision, 2010).

Hunger being a serious problem requires no emphasis and therefore, there are some responses which are meant to mitigate the problem. Various policies have therefore been established in all related areas. For example, there are various policies that that have been established to regulate high food prices. Such measures are inclusive but not limited to tax on imports, restricting export to maintain adequate food in the country, measures to control prices of food as well as to enhance food affordability, and stabilizing prices.

Improving and increasing agricultural produce is an important measure that has been taking place especially in the developing countries meant to increase supply and eventually curb the problem of hunger. At this point, is important to note that the number of response which have be taken to reduce or eliminate the problem of hunger vary from one region to another.

In addition, every region implements the policies that can be useful in that particular region. According to Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2010 pp.32 ), a survey conducted in the year 2007 and 2008 indicated that about 50% of all the countries reduced the tax of imports on cereals and more than fifty percent adopted measures like consumer subsidies with an aim of lowering domestic food prices.

Twenty five percent of the countries imposed restrictions on exports to minimize the outflow of food and the remaining 16% had done nothing to solve the problem of high domestic food prices. It is quite unfortunate that the regions that are mostly affected by hunger like Sub Saharan Africa; Caribbean as well Latin America has established the lowest number of policies.

Although such policies are of great help locally, they have negative impacts in the international markets. For example, due to restriction on exports, the supply of food at the international markets is usually low and as a result, the prices end up increasing. Apart from that, subsidies on imports increase government expenditure thereby straining the budget.

Therefore, it is clear that some measures of price do not control neither they end up mitigating the problem since they affect other people like farmers and traders. The main cause of the problem is due to the fact that most governments are unable to protect their economy from external influences.

While looking for the solutions to the problem, it is important to note that the demand of food will continue to increase due to various factors like urban growth and development as well as the high level of income. In that case, there is a great need for increasing food production.

In addition, the intervention should aim at not only solving the current problem but also solving any shortage that may emerge in future. Therefore, all regions and especially the sub-Saharan Africa ought to focus on increasing agricultural production. Moreover, it is necessary to come up with appropriate policies to ensure that the increase in food production will solve the problem of food insecurity (National Research Council (U.S.). Committee on Public Engineering Policy, 1975).

One of the problems that have been causing hunger especially in developing countries is inaccessibility to adequate food. As a result, the concerned stakeholders should look for ways and means of increasing food accessibility. For instance; it would be more helpful if the production of small scale farmers could increase because the problem cannot only help in lowering food prices in the global market but also in alleviating poverty and hunger in the rural areas.

Although incentives and agricultural inputs are important in increasing agricultural production in the rural areas, some other measures can still be used in the same areas. For instance, in a region like Africa, more areas can be irrigated and by so doing, agricultural production can increase as well ( Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2010).

World hunger is a real and a serious problem not only due to its grave impacts but also due to the complexity of the whole issue. A lot of people in the whole world are exposed to hunger. A critical analysis of the problem illustrates that it not only results from low food production but it is also affected by other factors such as inaccessibility of food, high food prices and some policies established by the government.

For example, the research has indicated that some polices that control the prices of food in local markets end up increasing food prices in the global market. In the view of the fact that hunger is the underlying cause of poverty, disease and eventually death, it is important for the concerned stake holders to address the issue accordingly.

As the studies of Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, (2008, p. 2) indicate, the over nine million hunger stricken people can be saved only if the stake holders that are inclusive of the government, United Nations, civil societies, donors and humanitarian agencies, general public and the private sector can join hands in combating the problem.

In order to come up with lasting solutions, their efforts should be aimed at improving the agricultural sector and establishing safety nets to protect the vulnerable population. Finally, in every challenge, there is an opportunity and in that case, the high prices of food can be used as an opportunity by small scale producers to increase their produce and get more returns and thereby reduce problems like poverty which contribute to hunger. Therefore, even though the problem is complicated, viable solutions still exist.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2010). Global hunger declining, but still unacceptably high . Web.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2008). The State of Food Insecurity in the World . Web.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Economic and Social Dept. (2005). The state of food insecurity in the world, 2005: eradicating world hunger – key to achieving the Millennium Development Goals. New York: Food & Agriculture Org.

Holben, D. H. (n. d.). The Concept and Definition of Hunger and Its Relationship to Food Insecurity . Web.

National Research Council (U.S.). Committee on Public Engineering Policy. ( 1975). World hunger: approaches to engineering actions : report of a seminar. Washington: National Academies.

World Hunger Education Service . (2010). World Hunger and Poverty Facts and Statistics 2010 . Web.

World Vision. (2010). The Global Food Crisis . Web.

Young, L. (1997). World hunger. London: Routledge.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, July 22). World Hunger Essay: Causes of World Hunger & How to Solve It. https://ivypanda.com/essays/world-hunger/

"World Hunger Essay: Causes of World Hunger & How to Solve It." IvyPanda , 22 July 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/world-hunger/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'World Hunger Essay: Causes of World Hunger & How to Solve It'. 22 July.

IvyPanda . 2018. "World Hunger Essay: Causes of World Hunger & How to Solve It." July 22, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/world-hunger/.

1. IvyPanda . "World Hunger Essay: Causes of World Hunger & How to Solve It." July 22, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/world-hunger/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "World Hunger Essay: Causes of World Hunger & How to Solve It." July 22, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/world-hunger/.

- Peter Singer in the Solution to World Hunger

- Identifying Malnutrition: Why Is It Important?

- World Hunger: Cause and Effect

- Citrus Greening Disease in The United States

- Establishment of the rye grass

- Physical Geography: Climatology and Geomorphology

- Running Speed in Dinosaurs

- The Ocean’s Rarest Mammal Vaquita – An Endangered Species

A global food crisis

Conflict, economic shocks, climate extremes and soaring fertilizer prices are combining to create a food crisis of unprecedented proportions. As many as 783 million people are facing chronic hunger. We have a choice: act now to save lives and invest in solutions that secure food security, stability and peace for all, or see people around the world facing rising hunger.

2023: Another year of extreme jeopardy for those struggling to feed their families

The scale of the current global hunger and malnutrition crisis is enormous. WFP estimates – from 78 of the countries where it works (and where data is available) – that more than 333 million people are facing acute levels of food insecurity in 2023, and do not know where their next meal is coming from. This constitutes a staggering rise of almost 200 million people compared to pre-COVID-19 pandemic levels.

At least 129,000 people are expected to experience famine in Burkina Faso, Mali, Somalia and South Sudan. Furthermore, any fragile progress already made in reducing numbers risks being lost, due to funding gaps and resulting cuts in assistance. The global community must not fail on its promise to end hunger and malnutrition by 2030.

WFP is facing multiple challenges – the number of acutely hungry people continues to increase at a pace that funding is unlikely to match , while the cost of delivering food assistance is at an all-time high because food and fuel prices have increased.

Unmet needs heighten the risk of hunger and malnutrition. Unless the necessary resources are made available, lost lives and the reversal of hard-earned development gains will be the price to pay.

The causes of hunger and famine

But why is the world hungrier than ever?

This seismic hunger crisis has been caused by a deadly combination of factors.

Conflict is still the biggest driver of hunger, with 70 percent of the world's hungry people living in areas afflicted by war and violence. Events in Ukraine are further proof of how conflict feeds hunger – forcing people out of their homes, wiping out their sources of income and wrecking countries’ economies.

The climate crisis is one of the leading causes of the steep rise in global hunger. Climate shocks destroy lives, crops and livelihoods, and undermine people’s ability to feed themselves. Hunger will spiral out of control if the world fails to take immediate climate action.

Global fertilizer prices have climbed even faster than food prices, which remain at a ten-year high themselves. The effects of the war in Ukraine, including higher natural gas prices, have further disrupted global fertilizer production and exports – reducing supplies, raising prices and threatening to reduce harvests. High fertilizer prices could turn the current food affordability crisis into a food availability crisis, with production of maize, rice, soybean and wheat all falling in 2022.

On top of increased operational costs , WFP is facing a major drop in funding in 2023 compared to the previous year, reflecting the new and more challenging financial landscape that the entire humanitarian sector is navigating. As a result, assistance levels are well below those of 2022. Almost half of WFP country operations have already been forced to cut the size and scope of food, cash and nutrition assistance by up to 50 percent.

WFP Annual Review 2022

Publication | 23 June 2023

WFP and FAO sound the alarm as global food crisis tightens its grip on hunger hotspots

Story | 21 September 2022

WFP scales up support to most vulnerable in global food crisis

Publication | 14 July 2022

Hunger hotspots

From the Central American Dry Corridor and Haiti, through the Sahel, Central African Republic, South Sudan and then eastwards to the Horn of Africa, Syria, Yemen and all the way to Afghanistan, conflict and climate shocks are driving millions of people to the brink of starvation.

Last year, the world rallied extraordinary resources – a record-breaking US$14.1 billion for WFP alone – to tackle the unprecedented global food crisis. In countries like Somalia, which has been teetering on the brink of famine, the international community came together and managed to pull people back. But it is not sufficient to only keep people alive. We need to go further, and this can only be achieved by addressing the underlying causes of hunger.

The consequences of not investing in resilience activities will reverberate across borders. If communities are not empowered to withstand shocks and stresses, this could result in increased migration and possible destabilization and conflict. Recent history has shown us this: when WFP ran out of funds to feed Syrian refugees in 2015, they had no choice but to leave the camps and seek help elsewhere, causing one of the greatest refugee crises in recent European history.

Let's stop hunger now

WFP’s changing lives work helps to build human capital, support governments in strengthening social protection programmes, stabilize communities in particularly precarious places, and help them to better survive sudden shocks without losing all their assets.

In just four years of the Sahel Resilience Scale-up, WFP and local communities turned 158,000 hectares of barren fields in the Sahel region of five African countries into farm and grazing land. Over 2.5 million people benefited from integrated activities. Evidence shows that people are better equipped to withstand seasonal shocks and have improved access to vital natural resources like land they can work. Families and their homes, belongings and fields are better protected against climate hazards. Support serves as a buffer to instability by bringing people together, creating social safety nets, keeping lands productive and offering job opportunities – all of which help to break the cycle of hunger.

As a further example, WFP’s flagship microinsurance programme – the R4 Rural Resilience initiative – protects around 360,000 farming and pastoralist families from climate hazards that threaten crops and livelihoods in 14 countries including Bangladesh, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Fiji, Guatemala, Kenya, Madagascar and Zimbabwe.

At the same time, WFP is working with governments in 83 countries to boost or build national safety nets and nutrition-sensitive social protection, allowing us to reach more people than we can with emergency food assistance.

Humanitarian assistance alone is not enough though. A coordinated effort across governments, financial institutions, the private sector and partners is the only way to mitigate an even more severe crisis in 2023. Good governance is a golden thread that holds society together, allowing human capital to grow, economies to develop and people to thrive.

The world also needs deeper political engagement to reach zero hunger. Only political will can end conflict in places like Yemen, Ethiopia and South Sudan, and without a firm political commitment to contain global warming as stipulated in the Paris Agreement , the main drivers of hunger will continue unabated.

In 2023, hunger levels are higher than ever before

Help families facing unprecedented hunger

Advanced search

- Social Justice

- Environment

- Health & Happiness

- Get YES! Emails

- Teacher Resources

- Give A Gift Subscription

- Teaching Sustainability

- Teaching Social Justice

- Teaching Respect & Empathy

- Student Writing Lessons

- Visual Learning Lessons

- Tough Topics Discussion Guides

- About the YES! for Teachers Program

- Student Writing Contest

Follow YES! For Teachers

Six brilliant student essays on the power of food to spark social change.

Read winning essays from our fall 2018 “Feeding Ourselves, Feeding Our Revolutions,” student writing contest.

For the Fall 2018 student writing competition, “Feeding Ourselves, Feeding Our Revolutions,” we invited students to read the YES! Magazine article, “Cooking Stirs the Pot for Social Change,” by Korsha Wilson and respond to this writing prompt: If you were to host a potluck or dinner to discuss a challenge facing your community or country, what food would you cook? Whom would you invite? On what issue would you deliberate?

The Winners

From the hundreds of essays written, these six—on anti-Semitism, cultural identity, death row prisoners, coming out as transgender, climate change, and addiction—were chosen as essay winners. Be sure to read the literary gems and catchy titles that caught our eye.

Middle School Winner: India Brown High School Winner: Grace Williams University Winner: Lillia Borodkin Powerful Voice Winner: Paisley Regester Powerful Voice Winner: Emma Lingo Powerful Voice Winner: Hayden Wilson

Literary Gems Clever Titles

Middle School Winner: India Brown

A Feast for the Future

Close your eyes and imagine the not too distant future: The Statue of Liberty is up to her knees in water, the streets of lower Manhattan resemble the canals of Venice, and hurricanes arrive in the fall and stay until summer. Now, open your eyes and see the beautiful planet that we will destroy if we do not do something. Now is the time for change. Our future is in our control if we take actions, ranging from small steps, such as not using plastic straws, to large ones, such as reducing fossil fuel consumption and electing leaders who take the problem seriously.

Hosting a dinner party is an extraordinary way to publicize what is at stake. At my potluck, I would serve linguini with clams. The clams would be sautéed in white wine sauce. The pasta tossed with a light coat of butter and topped with freshly shredded parmesan. I choose this meal because it cannot be made if global warming’s patterns persist. Soon enough, the ocean will be too warm to cultivate clams, vineyards will be too sweltering to grow grapes, and wheat fields will dry out, leaving us without pasta.

I think that giving my guests a delicious meal and then breaking the news to them that its ingredients would be unattainable if Earth continues to get hotter is a creative strategy to initiate action. Plus, on the off chance the conversation gets drastically tense, pasta is a relatively difficult food to throw.

In YES! Magazine’s article, “Cooking Stirs the Pot for Social Change,” Korsha Wilson says “…beyond the narrow definition of what cooking is, you can see that cooking is and has always been an act of resistance.” I hope that my dish inspires people to be aware of what’s at stake with increasing greenhouse gas emissions and work toward creating a clean energy future.

My guest list for the potluck would include two groups of people: local farmers, who are directly and personally affected by rising temperatures, increased carbon dioxide, drought, and flooding, and people who either do not believe in human-caused climate change or don’t think it affects anyone. I would invite the farmers or farm owners because their jobs and crops are dependent on the weather. I hope that after hearing a farmer’s perspective, climate-deniers would be awakened by the truth and more receptive to the effort to reverse these catastrophic trends.

Earth is a beautiful planet that provides everything we’ll ever need, but because of our pattern of living—wasteful consumption, fossil fuel burning, and greenhouse gas emissions— our habitat is rapidly deteriorating. Whether you are a farmer, a long-shower-taking teenager, a worker in a pollution-producing factory, or a climate-denier, the future of humankind is in our hands. The choices we make and the actions we take will forever affect planet Earth.

India Brown is an eighth grader who lives in New York City with her parents and older brother. She enjoys spending time with her friends, walking her dog, Morty, playing volleyball and lacrosse, and swimming.

High School Winner: Grace Williams

Apple Pie Embrace

It’s 1:47 a.m. Thanksgiving smells fill the kitchen. The sweet aroma of sugar-covered apples and buttery dough swirls into my nostrils. Fragrant orange and rosemary permeate the room and every corner smells like a stroll past the open door of a French bakery. My eleven-year-old eyes water, red with drowsiness, and refocus on the oven timer counting down. Behind me, my mom and aunt chat to no end, fueled by the seemingly self-replenishable coffee pot stashed in the corner. Their hands work fast, mashing potatoes, crumbling cornbread, and covering finished dishes in a thin layer of plastic wrap. The most my tired body can do is sit slouched on the backless wooden footstool. I bask in the heat escaping under the oven door.

As a child, I enjoyed Thanksgiving and the preparations that came with it, but it seemed like more of a bridge between my birthday and Christmas than an actual holiday. Now, it’s a time of year I look forward to, dedicated to family, memories, and, most importantly, food. What I realized as I grew older was that my homemade Thanksgiving apple pie was more than its flaky crust and soft-fruit center. This American food symbolized a rite of passage, my Iraqi family’s ticket to assimilation.

Some argue that by adopting American customs like the apple pie, we lose our culture. I would argue that while American culture influences what my family eats and celebrates, it doesn’t define our character. In my family, we eat Iraqi dishes like mesta and tahini, but we also eat Cinnamon Toast Crunch for breakfast. This doesn’t mean we favor one culture over the other; instead, we create a beautiful blend of the two, adapting traditions to make them our own.

That said, my family has always been more than the “mashed potatoes and turkey” type.

My mom’s family immigrated to the United States in 1976. Upon their arrival, they encountered a deeply divided America. Racism thrived, even after the significant freedoms gained from the Civil Rights Movement a few years before. Here, my family was thrust into a completely unknown world: they didn’t speak the language, they didn’t dress normally, and dinners like riza maraka seemed strange in comparison to the Pop Tarts and Oreos lining grocery store shelves.

If I were to host a dinner party, it would be like Thanksgiving with my Chaldean family. The guests, my extended family, are a diverse people, distinct ingredients in a sweet potato casserole, coming together to create a delicious dish.

In her article “Cooking Stirs the Pot for Social Change,” Korsha Wilson writes, “each ingredient that we use, every technique, every spice tells a story about our access, our privilege, our heritage, and our culture.” Voices around the room will echo off the walls into the late hours of the night while the hot apple pie steams at the table’s center.

We will play concan on the blanketed floor and I’ll try to understand my Toto, who, after forty years, still speaks broken English. I’ll listen to my elders as they tell stories about growing up in Unionville, Michigan, a predominately white town where they always felt like outsiders, stories of racism that I have the privilege not to experience. While snacking on sunflower seeds and salted pistachios, we’ll talk about the news- how thousands of people across the country are protesting for justice among immigrants. No one protested to give my family a voice.

Our Thanksgiving food is more than just sustenance, it is a physical representation of my family ’s blended and ever-changing culture, even after 40 years in the United States. No matter how the food on our plates changes, it will always symbolize our sense of family—immediate and extended—and our unbreakable bond.

Grace Williams, a student at Kirkwood High School in Kirkwood, Missouri, enjoys playing tennis, baking, and spending time with her family. Grace also enjoys her time as a writing editor for her school’s yearbook, the Pioneer. In the future, Grace hopes to continue her travels abroad, as well as live near extended family along the sunny beaches of La Jolla, California.

University Winner: Lillia Borodkin

Nourishing Change After Tragedy Strikes

In the Jewish community, food is paramount. We often spend our holidays gathered around a table, sharing a meal and reveling in our people’s story. On other sacred days, we fast, focusing instead on reflection, atonement, and forgiveness.

As a child, I delighted in the comfort of matzo ball soup, the sweetness of hamantaschen, and the beauty of braided challah. But as I grew older and more knowledgeable about my faith, I learned that the origins of these foods are not rooted in joy, but in sacrifice.

The matzo of matzo balls was a necessity as the Jewish people did not have time for their bread to rise as they fled slavery in Egypt. The hamantaschen was an homage to the hat of Haman, the villain of the Purim story who plotted the Jewish people’s destruction. The unbaked portion of braided challah was tithed by commandment to the kohen or priests. Our food is an expression of our history, commemorating both our struggles and our triumphs.

As I write this, only days have passed since eleven Jews were killed at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh. These people, intending only to pray and celebrate the Sabbath with their community, were murdered simply for being Jewish. This brutal event, in a temple and city much like my own, is a reminder that anti-Semitism still exists in this country. A reminder that hatred of Jews, of me, my family, and my community, is alive and flourishing in America today. The thought that a difference in religion would make some believe that others do not have the right to exist is frightening and sickening.

This is why, if given the chance, I would sit down the entire Jewish American community at one giant Shabbat table. I’d serve matzo ball soup, pass around loaves of challah, and do my best to offer comfort. We would take time to remember the beautiful souls lost to anti-Semitism this October and the countless others who have been victims of such hatred in the past. I would then ask that we channel all we are feeling—all the fear, confusion, and anger —into the fight.

As suggested in Korsha Wilson’s “Cooking Stirs the Pot for Social Change,” I would urge my guests to direct our passion for justice and the comfort and care provided by the food we are eating into resisting anti-Semitism and hatred of all kinds.

We must use the courage this sustenance provides to create change and honor our people’s suffering and strength. We must remind our neighbors, both Jewish and non-Jewish, that anti-Semitism is alive and well today. We must shout and scream and vote until our elected leaders take this threat to our community seriously. And, we must stand with, support, and listen to other communities that are subjected to vengeful hate today in the same way that many of these groups have supported us in the wake of this tragedy.

This terrible shooting is not the first of its kind, and if conflict and loathing are permitted to grow, I fear it will not be the last. While political change may help, the best way to target this hate is through smaller-scale actions in our own communities.

It is critical that we as a Jewish people take time to congregate and heal together, but it is equally necessary to include those outside the Jewish community to build a powerful crusade against hatred and bigotry. While convening with these individuals, we will work to end the dangerous “otherizing” that plagues our society and seek to understand that we share far more in common than we thought. As disagreements arise during our discussions, we will learn to respect and treat each other with the fairness we each desire. Together, we shall share the comfort, strength, and courage that traditional Jewish foods provide and use them to fuel our revolution.

We are not alone in the fight despite what extremists and anti-semites might like us to believe. So, like any Jew would do, I invite you to join me at the Shabbat table. First, we will eat. Then, we will get to work.

Lillia Borodkin is a senior at Kent State University majoring in Psychology with a concentration in Child Psychology. She plans to attend graduate school and become a school psychologist while continuing to pursue her passion for reading and writing. Outside of class, Lillia is involved in research in the psychology department and volunteers at the Women’s Center on campus.

Powerful Voice Winner: Paisley Regester

As a kid, I remember asking my friends jokingly, ”If you were stuck on a deserted island, what single item of food would you bring?” Some of my friends answered practically and said they’d bring water. Others answered comically and said they’d bring snacks like Flamin’ Hot Cheetos or a banana. However, most of my friends answered sentimentally and listed the foods that made them happy. This seems like fun and games, but what happens if the hypothetical changes? Imagine being asked, on the eve of your death, to choose the final meal you will ever eat. What food would you pick? Something practical? Comical? Sentimental?

This situation is the reality for the 2,747 American prisoners who are currently awaiting execution on death row. The grim ritual of “last meals,” when prisoners choose their final meal before execution, can reveal a lot about these individuals and what they valued throughout their lives.

It is difficult for us to imagine someone eating steak, lobster tail, apple pie, and vanilla ice cream one moment and being killed by state-approved lethal injection the next. The prisoner can only hope that the apple pie he requested tastes as good as his mom’s. Surprisingly, many people in prison decline the option to request a special last meal. We often think of food as something that keeps us alive, so is there really any point to eating if someone knows they are going to die?

“Controlling food is a means of controlling power,” said chef Sean Sherman in the YES! Magazine article “Cooking Stirs the Pot for Social Change,” by Korsha Wilson. There are deeper stories that lie behind the final meals of individuals on death row.

I want to bring awareness to the complex and often controversial conditions of this country’s criminal justice system and change the common perception of prisoners as inhuman. To accomplish this, I would host a potluck where I would recreate the last meals of prisoners sentenced to death.

In front of each plate, there would be a place card with the prisoner’s full name, the date of execution, and the method of execution. These meals could range from a plate of fried chicken, peas with butter, apple pie, and a Dr. Pepper, reminiscent of a Sunday dinner at Grandma’s, to a single olive.

Seeing these meals up close, meals that many may eat at their own table or feed to their own kids, would force attendees to face the reality of the death penalty. It will urge my guests to look at these individuals not just as prisoners, assigned a number and a death date, but as people, capable of love and rehabilitation.

This potluck is not only about realizing a prisoner’s humanity, but it is also about recognizing a flawed criminal justice system. Over the years, I have become skeptical of the American judicial system, especially when only seven states have judges who ethnically represent the people they serve. I was shocked when I found out that the officers who killed Michael Brown and Anthony Lamar Smith were exonerated for their actions. How could that be possible when so many teens and adults of color have spent years in prison, some even executed, for crimes they never committed?

Lawmakers, police officers, city officials, and young constituents, along with former prisoners and their families, would be invited to my potluck to start an honest conversation about the role and application of inequality, dehumanization, and racism in the death penalty. Food served at the potluck would represent the humanity of prisoners and push people to acknowledge that many inmates are victims of a racist and corrupt judicial system.

Recognizing these injustices is only the first step towards a more equitable society. The second step would be acting on these injustices to ensure that every voice is heard, even ones separated from us by prison walls. Let’s leave that for the next potluck, where I plan to serve humble pie.

Paisley Regester is a high school senior and devotes her life to activism, the arts, and adventure. Inspired by her experiences traveling abroad to Nicaragua, Mexico, and Scotland, Paisley hopes to someday write about the diverse people and places she has encountered and share her stories with the rest of the world.

Powerful Voice Winner: Emma Lingo

The Empty Seat

“If you aren’t sober, then I don’t want to see you on Christmas.”

Harsh words for my father to hear from his daughter but words he needed to hear. Words I needed him to understand and words he seemed to consider as he fiddled with his wine glass at the head of the table. Our guests, my grandma, and her neighbors remained resolutely silent. They were not about to defend my drunken father–or Charles as I call him–from my anger or my ultimatum.

This was the first dinner we had had together in a year. The last meal we shared ended with Charles slopping his drink all over my birthday presents and my mother explaining heroin addiction to me. So, I wasn’t surprised when Charles threw down some liquid valor before dinner in anticipation of my anger. If he wanted to be welcomed on Christmas, he needed to be sober—or he needed to be gone.

Countless dinners, holidays, and birthdays taught me that my demands for sobriety would fall on deaf ears. But not this time. Charles gave me a gift—a one of a kind, limited edition, absolutely awkward treat. One that I didn’t know how to deal with at all. Charles went home that night, smacked a bright red bow on my father, and hand-delivered him to me on Christmas morning.

He arrived for breakfast freshly showered and looking flustered. He would remember this day for once only because his daughter had scolded him into sobriety. Dad teetered between happiness and shame. Grandma distracted us from Dad’s presence by bringing the piping hot bacon and biscuits from the kitchen to the table, theatrically announcing their arrival. Although these foods were the alleged focus of the meal, the real spotlight shined on the unopened liquor cabinet in my grandma’s kitchen—the cabinet I know Charles was begging Dad to open.

I’ve isolated myself from Charles. My family has too. It means we don’t see Dad, but it’s the best way to avoid confrontation and heartache. Sometimes I find myself wondering what it would be like if we talked with him more or if he still lived nearby. Would he be less inclined to use? If all families with an addict tried to hang on to a relationship with the user, would there be fewer addicts in the world? Christmas breakfast with Dad was followed by Charles whisking him away to Colorado where pot had just been legalized. I haven’t talked to Dad since that Christmas.

As Korsha Wilson stated in her YES! Magazine article, “Cooking Stirs the Pot for Social Change,” “Sometimes what we don’t cook says more than what we do cook.” When it comes to addiction, what isn’t served is more important than what is. In quiet moments, I like to imagine a meal with my family–including Dad. He’d have a spot at the table in my little fantasy. No alcohol would push him out of his chair, the cigarettes would remain seated in his back pocket, and the stench of weed wouldn’t invade the dining room. Fruit salad and gumbo would fill the table—foods that Dad likes. We’d talk about trivial matters in life, like how school is going and what we watched last night on TV.

Dad would feel loved. We would connect. He would feel less alone. At the end of the night, he’d walk me to the door and promise to see me again soon. And I would believe him.

Emma Lingo spends her time working as an editor for her school paper, reading, and being vocal about social justice issues. Emma is active with many clubs such as Youth and Government, KHS Cares, and Peer Helpers. She hopes to be a journalist one day and to be able to continue helping out people by volunteering at local nonprofits.

Powerful Voice Winner: Hayden Wilson

Bittersweet Reunion

I close my eyes and envision a dinner of my wildest dreams. I would invite all of my relatives. Not just my sister who doesn’t ask how I am anymore. Not just my nephews who I’m told are too young to understand me. No, I would gather all of my aunts, uncles, and cousins to introduce them to the me they haven’t met.

For almost two years, I’ve gone by a different name that most of my family refuses to acknowledge. My aunt, a nun of 40 years, told me at a recent birthday dinner that she’d heard of my “nickname.” I didn’t want to start a fight, so I decided not to correct her. Even the ones who’ve adjusted to my name have yet to recognize the bigger issue.

Last year on Facebook, I announced to my friends and family that I am transgender. No one in my family has talked to me about it, but they have plenty to say to my parents. I feel as if this is about my parents more than me—that they’ve made some big parenting mistake. Maybe if I invited everyone to dinner and opened up a discussion, they would voice their concerns to me instead of my parents.

I would serve two different meals of comfort food to remind my family of our good times. For my dad’s family, I would cook heavily salted breakfast food, the kind my grandpa used to enjoy. He took all of his kids to IHOP every Sunday and ordered the least healthy option he could find, usually some combination of an overcooked omelet and a loaded Classic Burger. For my mom’s family, I would buy shakes and burgers from Hardee’s. In my grandma’s final weeks, she let aluminum tins of sympathy meals pile up on her dining table while she made my uncle take her to Hardee’s every day.

In her article on cooking and activism, food writer Korsha Wilson writes, “Everyone puts down their guard over a good meal, and in that space, change is possible.” Hopefully the same will apply to my guests.

When I first thought of this idea, my mind rushed to the endless negative possibilities. My nun-aunt and my two non-nun aunts who live like nuns would whip out their Bibles before I even finished my first sentence. My very liberal, state representative cousin would say how proud she is of the guy I’m becoming, but this would trigger my aunts to accuse her of corrupting my mind. My sister, who has never spoken to me about my genderidentity, would cover her children’s ears and rush them out of the house. My Great-Depression-raised grandparents would roll over in their graves, mumbling about how kids have it easy nowadays.

After mentally mapping out every imaginable terrible outcome this dinner could have, I realized a conversation is unavoidable if I want my family to accept who I am. I long to restore the deep connection I used to have with them. Though I often think these former relationships are out of reach, I won’t know until I try to repair them. For a year and a half, I’ve relied on Facebook and my parents to relay messages about my identity, but I need to tell my own story.

At first, I thought Korsha Wilson’s idea of a cooked meal leading the way to social change was too optimistic, but now I understand that I need to think more like her. Maybe, just maybe, my family could all gather around a table, enjoy some overpriced shakes, and be as close as we were when I was a little girl.

Hayden Wilson is a 17-year-old high school junior from Missouri. He loves writing, making music, and painting. He’s a part of his school’s writing club, as well as the GSA and a few service clubs.

Literary Gems

We received many outstanding essays for the Fall 2018 Writing Competition. Though not every participant can win the contest, we’d like to share some excerpts that caught our eye.

Thinking of the main staple of the dish—potatoes, the starchy vegetable that provides sustenance for people around the globe. The onion, the layers of sorrow and joy—a base for this dish served during the holidays. The oil, symbolic of hope and perseverance. All of these elements come together to form this delicious oval pancake permeating with possibilities. I wonder about future possibilities as I flip the latkes.

—Nikki Markman, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, California

The egg is a treasure. It is a fragile heart of gold that once broken, flows over the blemishless surface of the egg white in dandelion colored streams, like ribbon unraveling from its spool.

—Kaylin Ku, West Windsor-Plainsboro High School South, Princeton Junction, New Jersey

If I were to bring one food to a potluck to create social change by addressing anti-Semitism, I would bring gefilte fish because it is different from other fish, just like the Jews are different from other people. It looks more like a matzo ball than fish, smells extraordinarily fishy, and tastes like sweet brine with the consistency of a crab cake.

—Noah Glassman, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, Bronx, New York

I would not only be serving them something to digest, I would serve them a one-of-a-kind taste of the past, a taste of fear that is felt in the souls of those whose home and land were taken away, a taste of ancestral power that still lives upon us, and a taste of the voices that want to be heard and that want the suffering of the Natives to end.

—Citlalic Anima Guevara, Wichita North High School, Wichita, Kansas

It’s the one thing that your parents make sure you have because they didn’t. Food is what your mother gives you as she lies, telling you she already ate. It’s something not everybody is fortunate to have and it’s also what we throw away without hesitation. Food is a blessing to me, but what is it to you?

—Mohamed Omar, Kirkwood High School, Kirkwood, Missouri

Filleted and fried humphead wrasse, mangrove crab with coconut milk, pounded taro, a whole roast pig, and caramelized nuts—cuisines that will not be simplified to just “food.” Because what we eat is the diligence and pride of our people—a culture that has survived and continues to thrive.

—Mayumi Remengesau, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, California

Some people automatically think I’m kosher or ask me to say prayers in Hebrew. However, guess what? I don’t know many prayers and I eat bacon.

—Hannah Reing, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, The Bronx, New York

Everything was placed before me. Rolling up my sleeves I started cracking eggs, mixing flour, and sampling some chocolate chips, because you can never be too sure. Three separate bowls. All different sizes. Carefully, I tipped the smallest, and the medium-sized bowls into the biggest. Next, I plugged in my hand-held mixer and flicked on the switch. The beaters whirl to life. I lowered it into the bowl and witnessed the creation of something magnificent. Cookie dough.

—Cassandra Amaya, Owen Goodnight Middle School, San Marcos, Texas

Biscuits and bisexuality are both things that are in my life…My grandmother’s biscuits are the best: the good old classic Southern biscuits, crunchy on the outside, fluffy on the inside. Except it is mostly Southern people who don’t accept me.

—Jaden Huckaby, Arbor Montessori, Decatur, Georgia

We zest the bright yellow lemons and the peels of flavor fall lightly into the batter. To make frosting, we keep adding more and more powdered sugar until it looks like fluffy clouds with raspberry seed rain.

—Jane Minus, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, Bronx, New York

Tamales for my grandma, I can still remember her skillfully spreading the perfect layer of masa on every corn husk, looking at me pitifully as my young hands fumbled with the corn wrapper, always too thick or too thin.

—Brenna Eliaz, San Marcos High School, San Marcos, Texas

Just like fry bread, MRE’s (Meals Ready to Eat) remind New Orleanians and others affected by disasters of the devastation throughout our city and the little amount of help we got afterward.

—Madeline Johnson, Spring Hill College, Mobile, Alabama

I would bring cream corn and buckeyes and have a big debate on whether marijuana should be illegal or not.

—Lillian Martinez, Miller Middle School, San Marcos, Texas

We would finish the meal off with a delicious apple strudel, topped with schlag, schlag, schlag, more schlag, and a cherry, and finally…more schlag (in case you were wondering, schlag is like whipped cream, but 10 times better because it is heavier and sweeter).

—Morgan Sheehan, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, Bronx, New York

Clever Titles

This year we decided to do something different. We were so impressed by the number of catchy titles that we decided to feature some of our favorites.

“Eat Like a Baby: Why Shame Has No Place at a Baby’s Dinner Plate”

—Tate Miller, Wichita North High School, Wichita, Kansas

“The Cheese in Between”

—Jedd Horowitz, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, Bronx, New York

“Harvey, Michael, Florence or Katrina? Invite Them All Because Now We Are Prepared”

—Molly Mendoza, Spring Hill College, Mobile, Alabama

“Neglecting Our Children: From Broccoli to Bullets”

—Kylie Rollings, Kirkwood High School, Kirkwood, Missouri

“The Lasagna of Life”

—Max Williams, Wichita North High School, Wichita, Kansas

“Yum, Yum, Carbon Dioxide In Our Lungs”

—Melanie Eickmeyer, Kirkwood High School, Kirkwood, Missouri

“My Potluck, My Choice”

—Francesca Grossberg, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, Bronx, New York

“Trumping with Tacos”

—Maya Goncalves, Lincoln Middle School, Ypsilanti, Michigan

“Quiche and Climate Change”

—Bernie Waldman, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, Bronx, New York

“Biscuits and Bisexuality”

“W(health)”

—Miles Oshan, San Marcos High School, San Marcos, Texas

“Bubula, Come Eat!”

—Jordan Fienberg, Ethical Culture Fieldston School, Bronx, New York

Get Stories of Solutions to Share with Your Classroom

Teachers save 50% on YES! Magazine.

Inspiration in Your Inbox

Get the free daily newsletter from YES! Magazine: Stories of people creating a better world to inspire you and your students.

Goal 2: Zero Hunger

Goal 2 is about creating a world free of hunger by 2030.The global issue of hunger and food insecurity has shown an alarming increase since 2015, a trend exacerbated by a combination of factors including the pandemic, conflict, climate change, and deepening inequalities.

By 2022, approximately 735 million people – or 9.2% of the world’s population – found themselves in a state of chronic hunger – a staggering rise compared to 2019. This data underscores the severity of the situation, revealing a growing crisis.

In addition, an estimated 2.4 billion people faced moderate to severe food insecurity in 2022. This classification signifies their lack of access to sufficient nourishment. This number escalated by an alarming 391 million people compared to 2019.

The persistent surge in hunger and food insecurity, fueled by a complex interplay of factors, demands immediate attention and coordinated global efforts to alleviate this critical humanitarian challenge.

Extreme hunger and malnutrition remains a barrier to sustainable development and creates a trap from which people cannot easily escape. Hunger and malnutrition mean less productive individuals, who are more prone to disease and thus often unable to earn more and improve their livelihoods.

2 billion people in the world do not have reg- ular access to safe, nutritious and sufficient food. In 2022, 148 million children had stunted growth and 45 million children under the age of 5 were affected by wasting.

How many people are hungry?

It is projected that more than 600 million people worldwide will be facing hunger in 2030, highlighting the immense challenge of achieving the zero hunger target.

People experiencing moderate food insecurity are typically unable to eat a healthy, balanced diet on a regular basis because of income or other resource constraints.

Why are there so many hungry people?

Shockingly, the world is back at hunger levels not seen since 2005, and food prices remain higher in more countries than in the period 2015–2019. Along with conflict, climate shocks, and rising cost of living, civil insecurity and declining food production have all contributed to food scarcity and high food prices.

Investment in the agriculture sector is critical for reducing hunger and poverty, improving food security, creating employment and building resilience to disasters and shocks.

Why should I care?

We all want our families to have enough food to eat what is safe and nutritious. A world with zero hunger can positively impact our economies, health, education, equality and social development.

It’s a key piece of building a better future for everyone. Additionally, with hunger limiting human development, we will not be able to achieve the other sustainable development goals such as education, health and gender equality.

How can we achieve Zero Hunger?

Food security requires a multi-dimensional approach – from social protection to safeguard safe and nutritious food especially for children to transforming food systems to achieve a more inclusive and sustainable world. There will need to be investments in rural and urban areas and in social protection so poor people have access to food and can improve their livelihoods.

What can we do to help?

You can make changes in your own life—at home, at work and in the community—by supporting local farmers or markets and making sustainable food choices, supporting good nutrition for all, and fighting food waste.

You can also use your power as a consumer and voter, demanding businesses and governments make the choices and changes that will make Zero Hunger a reality. Join the conversation, whether on social media platforms or in your local communities.

Facts and Figures

Goal 2 targets.

- Despite global efforts, in 2022, an estimated 45 million children under the age of 5 suffered from wasting, 148 million had stunted growth and 37 million were overweight. A fundamental shift in trajectory is needed to achieve the 2030 nutrition targets.

- To achieve zero hunger by 2030, urgent coordinated action and policy solutions are imperative to address entrenched inequalities, transform food systems, invest in sustainable agricultural practices, and reduce and mitigate the impact of conflict and the pandemic on global nutrition and food security.

Source: The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023

2.1 By 2030, end hunger and ensure access by all people, in particular the poor and people in vulnerable situations, including infants, to safe, nutritious and sufficient food all year round.

2.2 By 2030, end all forms of malnutrition, including achieving, by 2025, the internationally agreed targets on stunting and wasting in children under 5 years of age, and address the nutritional needs of adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women and older persons.

2.3 By 2030, double the agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers, in particular women, indigenous peoples, family farmers, pastoralists and fishers, including through secure and equal access to land, other productive resources and inputs, knowledge, financial services, markets and opportunities for value addition and non-farm employment.

2.4 By 2030, ensure sustainable food production systems and implement resilient agricultural practices that increase productivity and production, that help maintain ecosystems, that strengthen capacity for adaptation to climate change, extreme weather, drought, flooding and other disasters and that progressively improve land and soil quality.

2.5 By 2020, maintain the genetic diversity of seeds, cultivated plants and farmed and domesticated animals and their related wild species, including through soundly managed and diversified seed and plant banks at the national, regional and international levels, and promote access to and fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the utilization of genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge, as internationally agreed.

2.A Increase investment, including through enhanced international cooperation, in rural infrastructure, agricultural research and extension services, technology development and plant and livestock gene banks in order to enhance agricultural productive capacity in developing countries, in particular least developed countries.

2.B Correct and prevent trade restrictions and distortions in world agricultural markets, including through the parallel elimination of all forms of agricultural export subsidies and all export measures with equivalent effect, in accordance with the mandate of the Doha Development Round.

2.C Adopt measures to ensure the proper functioning of food commodity markets and their derivatives and facilitate timely access to market information, including on food reserves, in order to help limit extreme food price volatility.

International Fund for Agricultural Development

Food and Agriculture Organization

World Food Programme

UNICEF – Nutrition

Zero Hunger Challenge

Think.Eat.Save. Reduce your foodprint.

UNDP – Hunger

Fast Facts: No Hunger

Infographic: No Hunger

Related news

UN forum in Bahrain endorses declaration on entrepreneurship and innovation for the SDGs

dpicampaigns 2024-05-15T08:00:00-04:00 15 May 2024 |

Delegates attending a UN forum in Bahrain endorsed on Wednesday a declaration calling on the international community to harness the power of entrepreneurship and innovation in pursuit of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), with a strong emphasis on including women, youth, persons with disabilities and productive families in these efforts.

UN forum in Bahrain: Innovation as the key to solving global problems

dpicampaigns 2024-05-15T16:48:52-04:00 14 May 2024 |

A major UN forum opened on Tuesday in Bahrain. Its mission: to empower entrepreneurial leaders who can build a brighter future and achieve sustainable development for all.

Media Advisory | UN to launch updated outlook for global economy

Yinuo 2024-05-13T11:31:07-04:00 13 May 2024 |

UN to launch updated outlook for global economy

PRESS BRIEFING

Thursday, 16 May 2024, 12:30 pm (EDT)

Live on UN WebTV

The report is under embargo until 16 May 2024, […]

Related videos

UN to launch updated outlook for global economy PRESS BRIEFING Thursday, 16 May 2024, 12:30 pm (EDT) Live on UN WebTV The report is under embargo until 16 May 2024, 12:30 pm EDT The [...]

Share this story, choose your platform!

Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Hunger — About World Hunger: A Global Crisis in Need of Solutions

About World Hunger: a Global Crisis in Need of Solutions

- Categories: Hunger World Food Crisis

About this sample

Words: 749 |

Published: Sep 12, 2023

Words: 749 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Table of contents

The magnitude of the problem, causes of world hunger, consequences of world hunger, addressing world hunger: potential solutions, the importance of global collaboration.

- According to the United Nations, nearly 9% of the world's population, or approximately 690 million people, suffered from chronic hunger in 2019.

- Hunger-related diseases and malnutrition are responsible for about 45% of child deaths worldwide.

- Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia are regions with the highest prevalence of hunger, where millions face food insecurity daily.

1. Poverty:

2. inequality:, 3. conflict and displacement:, 4. climate change:, 5. lack of infrastructure:, 6. food waste:, 1. malnutrition:, 2. impaired productivity:, 3. poverty trap:, 4. social unrest:, 1. poverty alleviation:, 2. food aid and assistance:, 3. climate resilience:, 4. education:, 5. reducing food waste:, 6. sustainable agriculture:.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Social Issues

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 973 words

3 pages / 1399 words

3 pages / 1429 words

2 pages / 967 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Hunger

World Hunger is a huge problem around the world that could be fixed. around the world we have 815 million deaths a year, it is also 45% of all childhood deaths. Also, you’ll need to know what other things people go through if [...]

The term food insecurity paints a vivid picture of a world marked by disparities and inequities, where the color of hunger affects millions of lives across the globe. This essay delves into the intricate web of factors [...]

Africa, a continent known for its rich cultural diversity and natural beauty, is also home to a significant challenge: widespread poverty. Despite its vast resources, Africa faces complex issues related to poverty that have [...]

World hunger remains a pressing issue that affects millions of individuals and communities around the world. According to the United Nations, more than 820 million people suffer from chronic hunger, and the COVID-19 pandemic has [...]

Statistics on child deaths due to poor nutrition Importance of nutrition for human health Overview of the worldwide issue of insufficient food intake High unemployment [...]

Hunger can be defined as a feeling of discomfort or weakness that you get when you need something to eat. Everyone feels hungry and most people are able to satisfy their craving. Hunger is also defined as a severe lack of food [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Opinion: We Can End Hunger, Here's How

The international community has embraced eliminating hunger by 2030. But with more than 600 million people still likely to suffer from hunger in 2030, we're far from reaching that goal. We're making progress against hunger, the head of the Food and Agriculture Organization writes, but not enough to end it.

Social Studies, Economics

Feeding a Family

a mother feeding her 10 children in Kenya

Photograph by Dominic Nahr

This article was originally published October 16, 2015, written by José Graziano Da Silva, UN Director General of the Food and Agriculture Organization. The international community has embraced a new goal, the eradication of hunger by 2030. That makes us the zero-hunger generation with a shared commitment to make hunger history. As we commemorate the UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s birth 70 years ago and celebrate World Food Day, we are reminded of FAO’s mission to ensure food security for all, everywhere. The zero-hunger goal requires us to accelerate our efforts to eliminate hunger and poverty. FAO monitors 129 countries and 72 of those have halved the number of people experiencing undernourishment between the years of 1991 and 2014 and have achieved the Millennium Development Goal. (Since the release of this op-ed, the UN Millemmium Development Goals, have been replaced by the UN Sustainable Development Goals or SDGs. Eliminating hunger is the second goal, or SDG 2 .) Progress, however, has been uneven: Some 800 million people continue to suffer hunger, and almost a billion live in extreme poverty. We need to break out of the cycles that trap people in poverty and hunger. In a business-as-usual scenario, more than 600 million people are still likely to be hungry in 2030. That’s a long way from zero. A Pro-Poor Posture Eradicating hunger requires commitment—political will. It will require sustained efforts in many areas, particularly pro-poor investments in rural areas, where the majority of the world’s most vulnerable live. Economic growth alone will not suffice; it needs to be socially inclusive to ensure sufficient access to food for all. Pro-poor public investments include infrastructure benefitting small family farms, ensuring sustainable agriculture, reducing post-harvest food losses, strengthening land and water rights, and making sure that the poor and marginalized —whose ranks include many women and youth—have fair access to credit, farm inputs including seed and fertilizers, and the extension services that provide training and advice to rural, small family farms. Road improvement projects in South Asia's Bangladesh, to cite an example, increased agricultural wages by 27 percent and greatly increased school enrollment for local children. Such investments can break the self-perpetuating cycle of rural poverty. Beyond Short-Term Tactics Along with more pro-poor investments, we need to promote wider and deeper use of social protection programs to lift people out of poverty permanently by ensuring people do not slip back into it. Social protection refers to programs to provide basic needs. Providing a social protection floor ensures basic needs for all. Social protection schemes can take many forms, including guaranteed employment in public works, cash or in-kind transfers to eligible beneficiaries, and school feeding programs. If well designed, they enable the poorest to undertake activities to earn more, rising above the poverty line. In 2013 alone, social protection measures took around 150 million people out of extreme poverty. The growing acceptance and proliferation of social protection in the developing world implies the recognition of their ability to immediately address poverty and hunger. Such schemes work and are affordable, especially compared to the cost and price of doing nothing. Social protection offsets income shortfalls so that vulnerable households can avoid livelihood and food security shocks (sudden, unexpected loss of food from climate change or a geopolitical crisis), which are particularly hard for rural households that are dependent on agriculture to recover from. But it can do much more: It can help millions of family farmers and rural laborers move beyond short-term survival tactics and enable them to invest more in productive activities as well as their children’s health and education. Time is money, and that is no less true for the poor. Today, we know that even relatively small monetary transfers to poor households, when regular and predictable, helps them pursue other income-generating activities. Far from creating dependency or reducing work effort, social protection strengthens livelihoods. Increasing the purchasing power of the poor also benefits the wider community by increasing business opportunities, triggering a virtuous local economic growth cycle, which is especially welcome in typically neglected rural areas. But social protection programs, on their own, will not be enough. We need to integrate them with pro-poor agricultural investment programs to derive more effective collaborations. Political commitment, partnerships, and adequate funding are key to realizing this vision. Policies and plans for rural development, poverty reduction, food security, and nutrition need to promote pro-poor investments and social protection to fight poverty and hunger, together with a broader set of interventions, notably in health and education. We know what to do. We have the tools. Now we’ve made the pledge. So we must be the zero-hunger generation.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Manager