An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMJ Case Rep

Case Report

Atypical presentation of molar pregnancy, ream langhe.

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital, Drogheda, Ireland

Bogdan Alexandru Muresan

Nor azlia abdul wahab.

The classic features of molar pregnancy are irregular vaginal bleeding, hyperemesis, enlarged uterus for gestational age and early failed pregnancy. Less common presentations include hyperthyroidism, early onset pre-eclampsia or abdominal distension due to theca lutein cysts. Here, we present a case of molar pregnancy where a woman presented to the emergency department with symptoms of acute abdomen and was treated as ruptured ectopic pregnancy. The woman underwent laparoscopy and evacuation of retained products of conception. Histological examination of uterine curettage confirmed the diagnosis of a complete hydatidiform mole. The woman was discharged home in good general condition with a plan for serial beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) follow-up. Complete follow-up includes use of contraception and follow-up after beta-hCG is negative for a year.

Molar pregnancies, a premalignant form of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia, are characterised by an overgrowth of fetal chorionic tissue within the uterus. 1 In the USA, molar pregnancy occurs in 1 in 1000–1200 pregnancies and in 1 in 600 therapeutic abortions. 2 In the UK, the incidence is estimated at 1/714 live births. Currently, there is no database that records gestational events in the Irish population. 3

Molar pregnancies are categorised as partial hydatidiform mole or complete hydatidiform mole based on genetic and histological features. 4 Complete hydatidiform moles usually occur as a result of duplication of a single sperm following fertilisation of an ‘empty’ oocyte (75%–80% of complete hydatidiform moles). They are diploid and entirely of male origin with no evidence of fetal tissues. Less commonly (20%–25%), complete hydatidiform moles can arise following dispermic fertilisation of an empty oocyte. In partial hydatidiform molar pregnancies, the trophoblast cells have two sets of paternal haploid genes and one set of maternal haploid genes (90%). They occur as a result of fertilisation of an oocyte by two sperms at the same time. In partial hydatidiform moles, there is usually evidence of fetal tissues. 4 5

Molar pregnancy is usually presented with painless vaginal bleeding, 6 or sometimes it is associated with abdominal pain and morning sickness, along with enlarged uterus for gestational age. 4 Less commonly, women might present with signs of hyperthyroidism, early onset pre-eclampsia or with acute respiratory failure or neurological symptoms. 4 Women at risk of molar pregnancy, particularly complete hydatidiform mole, are those at the extremes of the reproductive age: girls <15 years and women >45 years. 7 Furthermore, the risk of molar pregnancy is increased in women with a previous history of molar pregnancy. 8

Molar pregnancy can be strongly suggested by ultrasound. 9–11 However, the definitive diagnosis requires histological examination of products of conception. 4 In complete hydatidiform mole, the ultrasound typically shows an absent gestational sac and a complex echogenic intrauterine mass with cystic spaces. The ultrasound diagnosis of a partial hydatidiform mole is difficult as it may resemble a normal conception. 5 12

Molar pregnancy should be treated by suction evacuation for complete hydatidiform mole or medical evacuation if fetal parts are identified. 4 Following evacuation, women should be followed by weekly beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) estimation until it reaches an undetectable level. 4

Here, we present a case of molar pregnancy, where a woman presented to the emergency department (ED) with symptoms of acute abdomen and was treated as a ruptured ectopic pregnancy. However, histological examination of uterine curettage confirmed the diagnosis of a complete hydatidiform mole.

Case presentation

A 33-year-old woman with a history of sudden onset of right iliac fossa pain and mild vaginal bleeding following 8 weeks amenorrhoea and a positive pregnancy test was brought to the ED by ambulance. The woman was sixth gravid with a history of two uncomplicated vaginal deliveries and three miscarriages, which were treated by evacuation of retained products of conception (ERPC). Eight days prior to the admission, she had vaginal bleeding with passage of clots but she had not presented to the hospital. Her medical history was unremarkable. On examination she was pale, in severe pain, with a temperature of 37°C, pulse rate of 108 beats per minute and blood pressure of 123/73 mm Hg. On abdominal examination, the abdomen was observed to be very distended, tender and rigid. Vaginal examination was not carried out due to the excruciating pain. Abdominal ultrasound examination was performed with difficulty, and showed some free fluid in the abdominal cavity. Two large-bore cannula were inserted and blood was sent urgently for full blood count (FBC), serum electrolytes, renal and liver function tests (LFTs), beta-hCG titre and blood group and cross-matched of 2 units. Her blood results showed iron deficiency anaemia and haemoglobin was 6.1 g/dL.

In light of these symptoms and low haemoglobin level, 1 unit of O-negative red cells was transfused and a decision for emergency laparoscopy was made to rule out ruptured ectopic pregnancy. At the laparoscopy, both fallopian tubes were mildly dilated and blood was dripping from the fimbrial ends of the tubes, which could possibly have been retrograde bleeding from the uterine cavity. There were no tubal masses and the uterus was very bulky: approximately the size of 17 weeks gestation. In view of the bulky size and ‘spongy’ consistency of the uterus, and absence of tubal mass, a transabdominal scan was performed intraoperatively after releasing the pneumoperitoneum. This showed an enlarged uterine cavity with a snowstorm appearance, suggesting a molar pregnancy. Following this, a decision was made for ERPC under ultrasound guidance with suction curette. Endometrial tissues were sent urgently for histological examination.

On day 1 postoperative, the patient developed fever and complained of upper abdominal pain and an orange discolouration of urine. On examination, her abdomen was distended and tender in the right hypochondrial region. A septic infectious screen was performed and intravenous antibiotics were administered; 750 mg cefuroxime, 500 mg metronidazole and 4.5 g piperacillin/tazobactam 8 hourly were commenced as per unit protocol and in collaboration with the microbiologist. A further 2 units of red cells were transfused once fever subsided. The results of the blood culture revealed Gram-negative bacilli growth. Her LFTs showed elevated liver enzyme of alanine transaminase (ALT) (or serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (SGPT)) 185 IU/L and bilirubin level of 45 mg/dL. Her liver and biliary tract scan was unremarkable apart from a well-circumscribed hyperechoic lesion of 1 cm with no vascularity (probably a haemangioma).

Forty-eight hours later, her haemoglobin increased to 10 g/dL and repeated LFT showed decreased liver enzyme of ALT (SGPT) 97 IU/L, and bilirubin levels of 11 mg/dL. Her serial beta-hCG dropped from 225 000 IU/L preoperatively to 27 000 IU/L on the fourth postoperative day. Her histological examination result confirmed the diagnosis of complete hydatidiform mole. She showed significant improvement in her condition and LFT results of ALT (SGPT) 52 IU/L, and bilirubin of 6 mg/dL. She was discharged home on the fifth postoperative day with a plan for a weekly beta-hCG and LFT and a follow-up abdominal scan in 3 months’ time. The woman was debriefed about the condition, and information was supplemented with a patient information leaflet. By the third week postoperative, her LFT level return to a normal level and beta-hCG level decreased to 1300 IU/L. She will continue to be monitored weekly until her beta-hCG reaches an undetectable level.

Investigations

FBC, LFT, renal function test, beta-hCG and transabdominal ultrasound.

Differential diagnosis

Ruptured ectopic pregnancy.

Laparoscopy and ERPC.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was discharged in good condition with a plan for weekly estimation of serum beta-hCG and repeat abdominal ultrasound in 3 months. Complete follow-up includes use of contraception and follow-up after beta-hCG is negative for a year.

The classic features of molar pregnancy are irregular vaginal bleeding, hyperemesis, enlarged uterus for gestational age and early failed pregnancy. Less common presentations include hyperthyroidism, early onset pre-eclampsia or abdominal distension due to theca lutein cysts. Furthermore, women can present with acute respiratory failure or neurological symptoms such as seizures. 4 These symptoms would more commonly be associated with early pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. However, the possibility of metastatic gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD) should also be borne in mind. The particularities of the case are the presenting symptoms.

A review of the literature revealed few cases of molar pregnancies with an atypical clinical picture. A case of complete hydatidiform mole in a 20-year-old II gesta I para woman was reported. 13 The patient underwent excision of a haemorrhagic left ovarian cyst. Histopathological examination revealed a haemorrhagic corpus luteum with a single microscopic focus of detached atypical trophoblast, without chorionic villi. She then had a left salpingo-oophorectomy for persistently elevated hCG, which led to the final diagnosis of complete hydatidiform mole arising in the ovary. Short tandem genetic analysis confirmed the diagnosis of complete hydatidiform mole. 13 Another case of partial molar pregnancy was a 23-year-old primigravida woman who presented with atypical pre-eclampsia (high blood pressure 160/100 mm Hg, proteinuria of 3.4 g in 24 hours, headache, photophobia and anasarca) at 16 weeks gestation. 14 Another primigravida woman presented to ED with abdominal pain and vaginal bleeding and passing of a large, grape-like vesicular mass with multiple negative urine pregnancy tests. These negative tests, which were likely caused by the ‘high-dose hook effect’, delayed the management of the condition until the development of pulmonary choriocarcinoma at the time of diagnosis. 15

Our patient presented with severe lower abdominal pains and pelvic bleeding with a positive pregnancy test, all in the context of an un-booked pregnancy. Severe abdominal pains are not specific to the classic picture of molar pregnancy. This could be caused by the distension of the fallopian tubes and peritoneal irritation. The above symptomatology can mimic a wide range of pathologies like miscarriage, threatened miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy and placental abruption (in second trimester). A good differential diagnosis is important. In this case, the bedside transabdominal ultrasound that was performed in the ED was very difficult due to patient’s acute symptoms and lack of cooperation but was enough to raise a suspicion of haemoperitoneum, once free fluid was see in the abdominal cavity.

Intraoperative findings did not show any large lutein cyst causing the abdominal distension. There were small corpus lutea in otherwise normal ovaries. Large bowels were slightly dilated but not massively to suggest megacolon caused by Clostridium perfringens , which is known to be a gas-producing bacteria. Hence, the rigid distended abdomen at presentation of this woman was most likely from C. perfringens septicaemia, and particularly the intraoperative effect on her body.

High values of LFTs can suggest metastasis in a case of complete molar pregnancy and the patient has to be thoroughly investigated in order to outrule such complications. The patient had a chest X-ray, abdominal ultrasound scan and abdomino-pelvis CT, and metastasis were outruled. In this patient’s case, raised LFTs can be a sign of organ failure in the context of posible septicaemia.

Following the laparoscopy and uterine evacuation procedure, the patient developed fever. Blood cultures results showed Gram-negative bacilli growth, which was C. perfringens . The infection could be due to bacterial proliferation in the necrotic trophoblastic tissue or bacteria that originated from the vaginal flora and ascended into the cervix and the uterus, establishing the infection. However, C. perfringens is not a common flora in the vagina. Infection with C. perfringens is very rare. One of the sources of infection with this organism is from illegal abortion, hence this point should be explored by clinicians dealing with such a case.

There was a case report where a hysterectomy had to be performed after septicaemia with C. perfringens following suction dilatation and curettage for molar pregnancy. 16 This patient was reported to recover well after the hysterectomy. Fortunately, in our case, the patient was treated early with intravenous antibiotics and responded well to the treatment.

Molar pregnancies can present in atypical form. The diagnosis of GTD in the first trimester requires high clinical suspicion. Early diagnosis and management of the condition is associated with decreased risk of morbidity and mortality.

Learning points

- High index of suspicion is the key to diagnosing molar pregnancy, especially if it presents in atypical form.

- Early recognition of the condition saves lives and decreases morbidity.

- Molar pregnancy should be included in the differential diagnosis of vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain in the first trimester.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank the patient for her cooperation.

Contributors: RL: conception and design of study, acquisition of data. RL and AM: analysis and/or interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript. NA and EA: revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Global health

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 2018, Issue

- Atypical presentation of molar pregnancy

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Ream Langhe ,

- Bogdan Alexandru Muresan ,

- Etop Akpan ,

- Nor Azlia Abdul Wahab

- Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology , Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital , Drogheda , Ireland

- Correspondence to Dr Ream Langhe, reamlanghe{at}yahoo.co.uk

The classic features of molar pregnancy are irregular vaginal bleeding, hyperemesis, enlarged uterus for gestational age and early failed pregnancy. Less common presentations include hyperthyroidism, early onset pre-eclampsia or abdominal distension due to theca lutein cysts. Here, we present a case of molar pregnancy where a woman presented to the emergency department with symptoms of acute abdomen and was treated as ruptured ectopic pregnancy. The woman underwent laparoscopy and evacuation of retained products of conception. Histological examination of uterine curettage confirmed the diagnosis of a complete hydatidiform mole. The woman was discharged home in good general condition with a plan for serial beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) follow-up. Complete follow-up includes use of contraception and follow-up after beta-hCG is negative for a year.

- obstetrics and gynaecology

- reproductive medicine

https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2018-225545

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Background

Molar pregnancies, a premalignant form of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia, are characterised by an overgrowth of fetal chorionic tissue within the uterus. 1 In the USA, molar pregnancy occurs in 1 in 1000–1200 pregnancies and in 1 in 600 therapeutic abortions. 2 In the UK, the incidence is estimated at 1/714 live births. Currently, there is no database that records gestational events in the Irish population. 3

Molar pregnancies are categorised as partial hydatidiform mole or complete hydatidiform mole based on genetic and histological features. 4 Complete hydatidiform moles usually occur as a result of duplication of a single sperm following fertilisation of an ‘empty’ oocyte (75%–80% of complete hydatidiform moles). They are diploid and entirely of male origin with no evidence of fetal tissues. Less commonly (20%–25%), complete hydatidiform moles can arise following dispermic fertilisation of an empty oocyte. In partial hydatidiform molar pregnancies, the trophoblast cells have two sets of paternal haploid genes and one set of maternal haploid genes (90%). They occur as a result of fertilisation of an oocyte by two sperms at the same time. In partial hydatidiform moles, there is usually evidence of fetal tissues. 4 5

Molar pregnancy is usually presented with painless vaginal bleeding, 6 or sometimes it is associated with abdominal pain and morning sickness, along with enlarged uterus for gestational age. 4 Less commonly, women might present with signs of hyperthyroidism, early onset pre-eclampsia or with acute respiratory failure or neurological symptoms. 4 Women at risk of molar pregnancy, particularly complete hydatidiform mole, are those at the extremes of the reproductive age: girls <15 years and women >45 years. 7 Furthermore, the risk of molar pregnancy is increased in women with a previous history of molar pregnancy. 8

Molar pregnancy can be strongly suggested by ultrasound. 9–11 However, the definitive diagnosis requires histological examination of products of conception. 4 In complete hydatidiform mole, the ultrasound typically shows an absent gestational sac and a complex echogenic intrauterine mass with cystic spaces. The ultrasound diagnosis of a partial hydatidiform mole is difficult as it may resemble a normal conception. 5 12

Molar pregnancy should be treated by suction evacuation for complete hydatidiform mole or medical evacuation if fetal parts are identified. 4 Following evacuation, women should be followed by weekly beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) estimation until it reaches an undetectable level. 4

Here, we present a case of molar pregnancy, where a woman presented to the emergency department (ED) with symptoms of acute abdomen and was treated as a ruptured ectopic pregnancy. However, histological examination of uterine curettage confirmed the diagnosis of a complete hydatidiform mole.

Case presentation

A 33-year-old woman with a history of sudden onset of right iliac fossa pain and mild vaginal bleeding following 8 weeks amenorrhoea and a positive pregnancy test was brought to the ED by ambulance. The woman was sixth gravid with a history of two uncomplicated vaginal deliveries and three miscarriages, which were treated by evacuation of retained products of conception (ERPC). Eight days prior to the admission, she had vaginal bleeding with passage of clots but she had not presented to the hospital. Her medical history was unremarkable. On examination she was pale, in severe pain, with a temperature of 37°C, pulse rate of 108 beats per minute and blood pressure of 123/73 mm Hg. On abdominal examination, the abdomen was observed to be very distended, tender and rigid. Vaginal examination was not carried out due to the excruciating pain. Abdominal ultrasound examination was performed with difficulty, and showed some free fluid in the abdominal cavity. Two large-bore cannula were inserted and blood was sent urgently for full blood count (FBC), serum electrolytes, renal and liver function tests (LFTs), beta-hCG titre and blood group and cross-matched of 2 units. Her blood results showed iron deficiency anaemia and haemoglobin was 6.1 g/dL.

In light of these symptoms and low haemoglobin level, 1 unit of O-negative red cells was transfused and a decision for emergency laparoscopy was made to rule out ruptured ectopic pregnancy. At the laparoscopy, both fallopian tubes were mildly dilated and blood was dripping from the fimbrial ends of the tubes, which could possibly have been retrograde bleeding from the uterine cavity. There were no tubal masses and the uterus was very bulky: approximately the size of 17 weeks gestation. In view of the bulky size and ‘spongy’ consistency of the uterus, and absence of tubal mass, a transabdominal scan was performed intraoperatively after releasing the pneumoperitoneum. This showed an enlarged uterine cavity with a snowstorm appearance, suggesting a molar pregnancy. Following this, a decision was made for ERPC under ultrasound guidance with suction curette. Endometrial tissues were sent urgently for histological examination.

On day 1 postoperative, the patient developed fever and complained of upper abdominal pain and an orange discolouration of urine. On examination, her abdomen was distended and tender in the right hypochondrial region. A septic infectious screen was performed and intravenous antibiotics were administered; 750 mg cefuroxime, 500 mg metronidazole and 4.5 g piperacillin/tazobactam 8 hourly were commenced as per unit protocol and in collaboration with the microbiologist. A further 2 units of red cells were transfused once fever subsided. The results of the blood culture revealed Gram-negative bacilli growth. Her LFTs showed elevated liver enzyme of alanine transaminase (ALT) (or serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (SGPT)) 185 IU/L and bilirubin level of 45 mg/dL. Her liver and biliary tract scan was unremarkable apart from a well-circumscribed hyperechoic lesion of 1 cm with no vascularity (probably a haemangioma).

Forty-eight hours later, her haemoglobin increased to 10 g/dL and repeated LFT showed decreased liver enzyme of ALT (SGPT) 97 IU/L, and bilirubin levels of 11 mg/dL. Her serial beta-hCG dropped from 225 000 IU/L preoperatively to 27 000 IU/L on the fourth postoperative day. Her histological examination result confirmed the diagnosis of complete hydatidiform mole. She showed significant improvement in her condition and LFT results of ALT (SGPT) 52 IU/L, and bilirubin of 6 mg/dL. She was discharged home on the fifth postoperative day with a plan for a weekly beta-hCG and LFT and a follow-up abdominal scan in 3 months’ time. The woman was debriefed about the condition, and information was supplemented with a patient information leaflet. By the third week postoperative, her LFT level return to a normal level and beta-hCG level decreased to 1300 IU/L. She will continue to be monitored weekly until her beta-hCG reaches an undetectable level.

Investigations

FBC, LFT, renal function test, beta-hCG and transabdominal ultrasound.

Differential diagnosis

Ruptured ectopic pregnancy.

Laparoscopy and ERPC.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was discharged in good condition with a plan for weekly estimation of serum beta-hCG and repeat abdominal ultrasound in 3 months. Complete follow-up includes use of contraception and follow-up after beta-hCG is negative for a year.

The classic features of molar pregnancy are irregular vaginal bleeding, hyperemesis, enlarged uterus for gestational age and early failed pregnancy. Less common presentations include hyperthyroidism, early onset pre-eclampsia or abdominal distension due to theca lutein cysts. Furthermore, women can present with acute respiratory failure or neurological symptoms such as seizures. 4 These symptoms would more commonly be associated with early pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. However, the possibility of metastatic gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD) should also be borne in mind. The particularities of the case are the presenting symptoms.

A review of the literature revealed few cases of molar pregnancies with an atypical clinical picture. A case of complete hydatidiform mole in a 20-year-old II gesta I para woman was reported. 13 The patient underwent excision of a haemorrhagic left ovarian cyst. Histopathological examination revealed a haemorrhagic corpus luteum with a single microscopic focus of detached atypical trophoblast, without chorionic villi. She then had a left salpingo-oophorectomy for persistently elevated hCG, which led to the final diagnosis of complete hydatidiform mole arising in the ovary. Short tandem genetic analysis confirmed the diagnosis of complete hydatidiform mole. 13 Another case of partial molar pregnancy was a 23-year-old primigravida woman who presented with atypical pre-eclampsia (high blood pressure 160/100 mm Hg, proteinuria of 3.4 g in 24 hours, headache, photophobia and anasarca) at 16 weeks gestation. 14 Another primigravida woman presented to ED with abdominal pain and vaginal bleeding and passing of a large, grape-like vesicular mass with multiple negative urine pregnancy tests. These negative tests, which were likely caused by the ‘high-dose hook effect’, delayed the management of the condition until the development of pulmonary choriocarcinoma at the time of diagnosis. 15

Our patient presented with severe lower abdominal pains and pelvic bleeding with a positive pregnancy test, all in the context of an un-booked pregnancy. Severe abdominal pains are not specific to the classic picture of molar pregnancy. This could be caused by the distension of the fallopian tubes and peritoneal irritation. The above symptomatology can mimic a wide range of pathologies like miscarriage, threatened miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy and placental abruption (in second trimester). A good differential diagnosis is important. In this case, the bedside transabdominal ultrasound that was performed in the ED was very difficult due to patient’s acute symptoms and lack of cooperation but was enough to raise a suspicion of haemoperitoneum, once free fluid was see in the abdominal cavity.

Intraoperative findings did not show any large lutein cyst causing the abdominal distension. There were small corpus lutea in otherwise normal ovaries. Large bowels were slightly dilated but not massively to suggest megacolon caused by Clostridium perfringens , which is known to be a gas-producing bacteria. Hence, the rigid distended abdomen at presentation of this woman was most likely from C. perfringens septicaemia, and particularly the intraoperative effect on her body.

High values of LFTs can suggest metastasis in a case of complete molar pregnancy and the patient has to be thoroughly investigated in order to outrule such complications. The patient had a chest X-ray, abdominal ultrasound scan and abdomino-pelvis CT, and metastasis were outruled. In this patient’s case, raised LFTs can be a sign of organ failure in the context of posible septicaemia.

Following the laparoscopy and uterine evacuation procedure, the patient developed fever. Blood cultures results showed Gram-negative bacilli growth, which was C. perfringens . The infection could be due to bacterial proliferation in the necrotic trophoblastic tissue or bacteria that originated from the vaginal flora and ascended into the cervix and the uterus, establishing the infection. However, C. perfringens is not a common flora in the vagina. Infection with C. perfringens is very rare. One of the sources of infection with this organism is from illegal abortion, hence this point should be explored by clinicians dealing with such a case.

There was a case report where a hysterectomy had to be performed after septicaemia with C. perfringens following suction dilatation and curettage for molar pregnancy. 16 This patient was reported to recover well after the hysterectomy. Fortunately, in our case, the patient was treated early with intravenous antibiotics and responded well to the treatment.

Molar pregnancies can present in atypical form. The diagnosis of GTD in the first trimester requires high clinical suspicion. Early diagnosis and management of the condition is associated with decreased risk of morbidity and mortality.

Learning points

High index of suspicion is the key to diagnosing molar pregnancy, especially if it presents in atypical form.

Early recognition of the condition saves lives and decreases morbidity.

Molar pregnancy should be included in the differential diagnosis of vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain in the first trimester.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank the patient for her cooperation.

- Hu L , et al

- ↵ Department of Health . Diagnosis, staging and treatment of patients with gestational trophoblastic disease. National Clinical Guideline . 13 , 2015 .

- ↵ Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists . The management of gestational trophoblastic disease . London : RCOG Guidelines , 2010 .

- Cotran RS ,

- Fausto N , et al

- Sebire NJ ,

- Foskett M ,

- Fisher RA , et al

- Fisher RA ,

- Foskett M , et al

- Fowler DJ ,

- Lindsay I ,

- Seckl MJ , et al

- Paradinas F , et al

- Soto-Wright V ,

- Bernstein M ,

- Goldstein DP , et al

- Berkowitz RS , et al

- Kuroki LM ,

- Hopeman MM , et al

- Barrón Rodríguez JL ,

- Piña Saucedo F ,

- Clorio Carmona J , et al

- Hunter CL ,

- Lekovic JP ,

Contributors RL: conception and design of study, acquisition of data. RL and AM: analysis and/or interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript. NA and EA: revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent Obtained.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Advertisement

Molar Pregnancy: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Management, Surveillance

- Family Planning (A Roe and S Sonalkar, Section Editors)

- Published: 19 February 2022

- Volume 11 , pages 133–141, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Alice J. Darling ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4708-9247 1 ,

- Benjamin B. Albright 2 ,

- Kyle C. Strickland 3 &

- Brittany A. Davidson 2

495 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Purpose of Review

This review describes recommendations for the diagnosis and management of molar pregnancy, with focus on emerging evidence in recent years, particularly as it pertains to nuances of diagnosis, risk stratification, and surveillance of post-molar malignant trophoblastic disease.

Recent Findings

Topics discussed include advances in histopathologic diagnosis of molar pregnancy to standardize analysis, most recent estimations of post-molar pregnancy malignancy, and updated surveillance guidelines.

Hydatidiform molar pregnancy, resulting from an abnormal fertilization event, is the proliferation of abnormal pregnancy tissue with malignant potential. With increased availability of first trimester ultrasound, early detection of molar pregnancy has increased. While challenging to diagnose radiologically and histologically at early stages, standardization of tissue analysis allows improved detection and increased accuracy of incidence estimate for both complete and partial molar pregnancy. Treatment of molar pregnancy requires evacuation of tissue. Prophylactic chemotherapy or repeat curettage have been explored but not favored. As new molecular markers are sought, our ability to predict malignant transformation following molar pregnancies will allow for more streamlined surveillance. Recent data support a reduction in the length of surveillance following normalization of human chorionic gonadotropin levels after evacuation.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Recurrent Molar Pregnancy

Clinicopathological Study of Gestational Trophoblastic Disease (GTD) in a Tertiary Care Hospital

Evaluation of a routine second curettage for hydatidiform mole: a cohort study

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:, • of importance.

• Albright BB, Shorter JM, Mastroyannis SA, Ko EM, Schreiber CA, Sonalkar S. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia after human chorionic gonadotropin normalization following molar pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(1):12–23. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003566 . A systematic review and meta-analysis of post-molar gestational trophoblastic neoplasia incidence. This review found a very low (64/18,357, 0.35%, 95% CI 0.27-0.45%) cumulative incidence of GTN development after hCG normalization following a complete molar pregnancy. This rate was even lower for partial moles (5/14,864, 0.03%, 95% CI 0.01-0.08%) .

Article Google Scholar

Seckl MJ, Sebire NJ, Fisher RA, Golfier F, Massuger L, Sessa C. Gestational trophoblastic disease: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2013;24(6):vi39–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdt345 .

• Ngan HYS, Seckl MJ, Berkowitz RS, Xiang Y, Golfier F, Sekharan PK, et al. Update on the diagnosis and management of gestational trophoblastic disease. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;143(S2):79–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12615 . FIGO Cancer Report of 2018 reviewing Gestational Trophoblastic Disease. Includes updated FIGO guidelines-most notably removing elevated hCG at ≥6 months after uterine evacuation from GTN diagnostic criteria and specifying hCG followup intervals including reduced surveillance length after partial molar pregnancy .

Soper JT. Gestational Trophoblastic Disease: Current Evaluation and Management. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137(2):355–70. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000004240 .

Brown J, Naumann RW, Seckl MJ, Schink J. 15 years of progress in gestational trophoblastic disease: scoring, standardization, and salvage. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;144(1):200–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.YGYNO.2016.08.330 .

Lurain JR. Gestational trophoblastic disease I: epidemiology, pathology, clinical presentation and diagnosis of gestational trophoblastic disease, and management of hydatidiform mole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(6):531–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AJOG.2010.06.073 .

Seckl MJ, Sebire NJ, Berkowitz RS. Gestational trophoblastic disease. The Lancet. 2010;376(9742):717–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60280-2 .

Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP. Current management of gestational trophoblastic diseases. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112(3):654–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.YGYNO.2008.09.005 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Maisenbacher MK, Merrion K, Kutteh WH. Single-nucleotide polymorphism microarray detects molar pregnancies in 3% of miscarriages. Fertil Steril. 2019;112(4):700–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.06.015 .

Cozette C, Scheffler F, Lombart M, Massardier J, Bolze PA, Hajri T, et al. Pregnancy after oocyte donation in a patient with NLRP7 gene mutations and recurrent molar hydatidiform pregnancies. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020;37(9):2273–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-020-01861-z .

Eagles N, Sebire NJ, Short D, Savage PM, Seckl MJ, Fisher RA. Risk of recurrent molar pregnancies following complete and partial hydatidiform moles. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(9):2055–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dev169 .

Gockley AA, Melamed A, Joseph NT, Clapp M, Sun SY, Goldstein DP, et al. The effect of adolescence and advanced maternal age on the incidence of complete and partial molar pregnancy. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;140(3):470–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.YGYNO.2016.01.005 .

Savage PM, Sita-Lumsden A, Dickson S, Iyer R, Everard J, Coleman R, et al. The relationship of maternal age to molar pregnancy incidence, risks for chemotherapy and subsequent pregnancy outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33(4):406–11. https://doi.org/10.3109/01443615.2013.771159 .

Sebire NJ, Foskett M, Fisher RA, Rees H, Seckl M, Newlands E. Risk of partial and complete hydatidiform molar pregnancy in relation to maternal age. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;109(1):99–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.t01-1-01037.x .

Sato A, Usui H, Shozu M. ABO blood type compatibility is not a risk factor for gestational trophoblastic neoplasia development from androgenetic complete hydatidiform moles. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2020;83(6):e13237. https://doi.org/10.1111/aji.13237 .

Shamshiri Milani H, Abdollahi M, Torbati S, Asbaghi T, Azargashb E. Risk Factors for hydatidiform mole: is husband’s job a major risk factor?. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18(10):2657–62. https://doi.org/10.22034/apjcp.2017.18.10.2657 .

Berkowitz RS, Bernstein MR, Harlow BL, Rice LW, Lage JM, Goldstein DP, et al. Case-control study of risk factors for partial molar pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173(3 Pt 1):788–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(95)90342-9 .

Melamed A, Gockley AA, Joseph NT, Sun SY, Clapp MA, Goldstein DP, et al. Effect of race/ethnicity on risk of complete and partial molar pregnancy after adjustment for age. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;143(1):73–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.07.117 .

Sundvall L, Lund H, Niemann I, Jensen UB, Bolund L, Sunde L. Tetraploidy in hydatidiform moles. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(7):2010–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/det132 .

Sebire NJ, Savage PM, Seckl MJ, Fisher RA. Histopathological features of biparental complete hydatidiform moles in women with NLRP7 mutations. Placenta. 2013;34(1):50–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2012.11.005 .

Fisher RA, Hodges MD, Newlands ES. Familial recurrent hydatidiform mole: a review. J Reprod Med. 2004;49(8):595–601.

Google Scholar

King JR, Wilson ML, Hetey S, Kiraly P, Matsuo K, Castaneda AV et al. Dysregulation of placental functions and immune pathways in complete hydatidiform moles. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(20). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20204999 .

Fisher RA, Maher GJ. Genetics of gestational trophoblastic disease. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2021;74:29–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2021.01.004 .

Soellner L, Begemann M, Degenhardt F, Geipel A, Eggermann T, Mangold E. Maternal heterozygous NLRP7 variant results in recurrent reproductive failure and imprinting disturbances in the offspring. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017;25(8):924–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2017.94 .

Sun SY, Melamed A, Joseph NT, Gockley AA, Goldstein DP, Bernstein MR, et al. Clinical presentation of complete hydatidiform mole and partial hydatidiform mole at a regional trophoblastic disease center in the United States over the past 2 decades. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26(2):367–70. https://doi.org/10.1097/IGC.0000000000000608 .

Sun SY, Melamed A, Goldstein DP, Bernstein MR, Horowitz NS, Moron AF, et al. Changing presentation of complete hydatidiform mole at the New England Trophoblastic Disease Center over the past three decades: does early diagnosis alter risk for gestational trophoblastic neoplasia?. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;138(1):46–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.YGYNO.2015.05.002 .

Winder AD, Mora AS, Berry E, Lurain JR. The “hook effect” causing a negative pregnancy test in a patient with an advanced molar pregnancy. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2017;21:34–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gore.2017.06.008 .

Li P, Koch CD, El-Khoury JM. Perimenopausal woman with elevated serum hCG and abdominal pain. Clin Chim Acta. 2021;522:141–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2021.08.018 .

Ross JA, Unipan A, Clarke J, Magee C, Johns J. Ultrasound diagnosis of molar pregnancy. Ultrasound. 2018;26(3):153–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742271x17748514 .

Savage JL, Maturen KE, Mowers EL, Pasque KB, Wasnik AP, Dalton VK, et al. Sonographic diagnosis of partial versus complete molar pregnancy: a reappraisal. J Clin Ultrasound. 2017;45(2):72–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcu.22410 .

Ronnett BM. Hydatidiform moles: ancillary techniques to refine diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142(12):1485–502. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2018-0226-RA .

Hui P, Buza N, Murphy KM, Ronnett BM. Hydatidiform moles: genetic basis and precision diagnosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2017;12:449–85. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pathol-052016-100237 .

Madi JM, Braga A, Paganella MP, Litvin IE, Wendland EM. Accuracy of p57(KIP)(2) compared with genotyping to diagnose complete hydatidiform mole: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2018;125(10):1226–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15289 .

Zheng XZ, Qin XY, Chen SW, Wang P, Zhan Y, Zhong PP, et al. Heterozygous/dispermic complete mole confers a significantly higher risk for post-molar gestational trophoblastic disease. Mod Pathol. 2020;33(10):1979–88. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-020-0566-4 .

Lin LH, Maestá I, St Laurent JD, Hasselblatt KT, Horowitz NS, Goldstein DP, et al. Distinct microRNA profiles for complete hydatidiform moles at risk of malignant progression. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224(4):372.e1-e30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.09.048 .

Braga A, Maestá I, Rocha Soares R, Elias KM, Custódio Domingues MA, Barbisan LF, et al. Apoptotic index for prediction of postmolar gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(3):336.e1-.e12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2016.04.010 .

Padrón L, Rezende Filho J, Amim Junior J, Sun SY, Charry RC, Maestá I, et al. Manual compared with electric vacuum aspiration for treatment of molar pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;1-. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002522 .

Curry SL, Hammond CB, Tyrey L, Creasman WT, Parker RT. Hydatidiform mole: diagnosis, management, and long-term followup of 347 patients. Obstet Gynecol. 1975;45(1):1–8.

CAS Google Scholar

• Zhao P, Lu Y, Huang W, Tong B, Lu W. Total hysterectomy versus uterine evacuation for preventing post-molar gestational trophoblastic neoplasia in patients who are at least 40 years old: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-5168-x . A systematic review and meta-analysis which demonstrated a risk reduction in post-molar GTN of more than 80% in patients ≥40 years old following hysterectomy compared to those receiving uterine evacuations for molar pregnancy treatment .

Giorgione V, Bergamini A, Cioffi R, Pella F, Rabaiotti E, Petrone M, et al. Role of surgery in the management of hydatidiform mole in elderly patients: a single-center clinical experience. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27(3):550–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/igc.0000000000000903 .

Eysbouts YK, Massuger L, IntHout J, Lok CAR, Sweep F, Ottevanger PB. The added value of hysterectomy in the management of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145(3):536–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.03.018 .

Yamamoto E, Nishino K, Niimi K, Watanabe E, Oda Y, Ino K, et al. Evaluation of a routine second curettage for hydatidiform mole: a cohort study. Int J Clin Oncol. 2020;25(6):1178–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-020-01640-x .

Yamamoto E, Trinh TD, Sekiya Y, Tamakoshi K, Nguyen XP, Nishino K, et al. The management of hydatidiform mole using prophylactic chemotherapy and hysterectomy for high-risk patients decreased the incidence of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia in Vietnam: a retrospective observational study. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2020;82(2):183–91. https://doi.org/10.18999/nagjms.82.2.183 .

Wang Q, Fu J, Hu L, Fang F, Xie L, Chen H, et al. Prophylactic chemotherapy for hydatidiform mole to prevent gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2017;9:CD007289-CD. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007289.pub3 .

Jiao LZ, Wang YP, Jiang JY, Zhang WQ, Wang XY, Zhu CG, et al. Clinical significance of centralized surveillance of hydatidiform mole. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2018;53(6):390–5. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-567x.2018.06.006 .

Braga A, Biscaro A, do Amaral Giordani JM, Viggiano M, Elias KM, Berkowitz RS, et al. Does a human chorionic gonadotropin level of over 20,000 IU/L four weeks after uterine evacuation for complete hydatidiform mole constitute an indication for chemotherapy for gestational trophoblastic neoplasia?. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;223:50–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.02.001 .

Ngu SF, Ngan HYS. Surgery including fertility-sparing treatment of GTD. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2021;74:97–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2020.10.005 .

Zilberman Sharon N, Maymon R, Melcer Y, Jauniaux E. Obstetric outcomes of twin pregnancies presenting with a complete hydatidiform mole and coexistent normal fetus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2020;127(12):1450–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16283 .

Lin LH, Maestá I, Braga A, Sun SY, Fushida K, Francisco RPV, et al. Multiple pregnancies with complete mole and coexisting normal fetus in North and South America: A retrospective multicenter cohort and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145(1):88–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.01.021 .

• Albright BB, Myers ER, Moss HA, Ko EM, Sonalkar S, Havrilesky LJ. Surveillance for gestational trophoblastic neoplasia following molar pregnancy: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2021.05.031 . Cost-effectiveness analysis of post-molar GTN surveillance finding reduction or elimination of hCG surveillance would be cost effective and clinically reasonable given the rarity of malignant following hCG normalization. Additionally, found a single hCG test 3 months after uterine evacuation was a cost-effective alternative .

Massad LS, Abu-Rustum NR, Lee SS, Renta V. Poor compliance with postmolar surveillance and treatment protocols by indigent women. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(6):940–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01064-4 .

Blok LJ, Frijstein MM, Eysbouts YK, Custers J, Sweep F, Lok C, et al. The psychological impact of gestational trophoblastic disease: a prospective observational multicentre cohort study. BJOG. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16849 .

Jewell EL, Aghajanian C, Montovano M, Lewin SN, Baser RE, Carter J. Association of ß-hCG surveillance with emotional, reproductive, and sexual health in women treated for gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2018;27(3):387–93. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2016.6208 .

Stafford L, McNally OM, Gibson P, Judd F. Long-term psychological morbidity, sexual functioning, and relationship outcomes in women with gestational trophoblastic disease. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21(7):1256–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/IGC.0b013e3182259c04 .

Coyle C, Short D, Jackson L, Sebire NJ, Kaur B, Harvey R, et al. What is the optimal duration of human chorionic gonadotrophin surveillance following evacuation of a molar pregnancy? A retrospective analysis on over 20,000 consecutive patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;148(2):254–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.12.008 .

Management of Gestational Trophoblastic Disease: Green-top Guideline No. 38 - June 2020. BJOG. 2021;128(3):e1-e27. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16266 .

Horowitz NS, Eskander RN, Adelman MR, Burke W. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of gestational trophoblastic disease: a Society of Gynecologic Oncology evidenced-based review and recommendation. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;163(3):605–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2021.10.003 .

Lybol C, Sweep FC, Ottevanger PB, Massuger LF, Thomas CM. Linear regression of postevacuation serum human chorionic gonadotropin concentrations predicts postmolar gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23(6):1150–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/IGC.0b013e31829703ea .

Hardman S. Use of hormonal contraception after hydatidiform mole. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;123(8):1336. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13691 .

Gaffield ME, Kapp N, Curtis KM. Combined oral contraceptive and intrauterine device use among women with gestational trophoblastic disease. Contraception. 2009;80(4):363–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2009.03.022 .

Dantas PRS, Maestá I, Filho JR, Junior JA, Elias KM, Howoritz N, et al. Does hormonal contraception during molar pregnancy follow-up influence the risk and clinical aggressiveness of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia after controlling for risk factors? Gynecol Oncol. 2017;147(2):364–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.09.007 .

Braga A, Maestá I, Short D, Savage P, Harvey R, Seckl M. Hormonal contraceptive use before hCG remission does not increase the risk of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia following complete hydatidiform mole: a historical database review. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;123(8):1330–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13617 .

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Classifications for Intrauterine Devices. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2010. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr59e0528a6.htm . Accessed 25 Oct 2021.

Tuncer ZS, Bernstein MR, Goldstein DP, Lu KH, Berkowitz RS. Outcome of pregnancies occurring within 1 year of hydatidiform mole. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94(4):588–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0029-7844(99)00395-6 .

Joneborg U, Coopmans L, van Trommel N, Seckl M, Lok CAR. Fertility and pregnancy outcome in gestational trophoblastic disease. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2021;31(3):399–411. https://doi.org/10.1136/ijgc-2020-001784 .

Vargas R, Barroilhet LM, Esselen K, Diver E, Bernstein M, Goldstein DP, et al. Subsequent pregnancy outcomes after complete and partial molar pregnancy, recurrent molar pregnancy, and gestational trophoblastic neoplasia: an update from the New England Trophoblastic Disease Center. J Reprod Med. 2014;59(5–6):188–94.

Matsui H, Iitsuka Y, Suzuka K, Seki K, Sekiya S. Subsequent pregnancy outcome in patients with spontaneous resolution of HCG after evacuation of hydatidiform mole: comparison between complete and partial mole. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(6):1274–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/16.6.1274 .

Abu-Rustum NR, Yashar CM, Bean S, Bradley K, Campos SM, Chon HS, et al. Gestational Trophoblastic Neoplasia, Version 2.2019, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(11):1374–91. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2019.0053 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA

Alice J. Darling

Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA

Benjamin B. Albright & Brittany A. Davidson

Department of Pathology, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA

Kyle C. Strickland

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

AD: Project design, literature review, manuscript draft, critical revision, final approval. BA: Project conception and design, literature review, critical revision, final approval. KS: Collecting and preparing specimens for manuscript figure, critical revision, final approval. BD: Project conception and design, literature review, critical revision, final approval.

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval.

Not applicable, this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Family Planning

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Darling, A.J., Albright, B.B., Strickland, K.C. et al. Molar Pregnancy: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Management, Surveillance. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep 11 , 133–141 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13669-022-00327-6

Download citation

Accepted : 09 February 2022

Published : 19 February 2022

Issue Date : June 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13669-022-00327-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Molar pregnancy

- Hydatidiform mole

- Complete mole

- Partial mole

- Gestational Trophoblastic Disease

- Surveillance

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Atypical presentation of molar pregnancy

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital, Drogheda, Ireland.

- PMID: 30262528

- PMCID: PMC6169626

- DOI: 10.1136/bcr-2018-225545

The classic features of molar pregnancy are irregular vaginal bleeding, hyperemesis, enlarged uterus for gestational age and early failed pregnancy. Less common presentations include hyperthyroidism, early onset pre-eclampsia or abdominal distension due to theca lutein cysts. Here, we present a case of molar pregnancy where a woman presented to the emergency department with symptoms of acute abdomen and was treated as ruptured ectopic pregnancy. The woman underwent laparoscopy and evacuation of retained products of conception. Histological examination of uterine curettage confirmed the diagnosis of a complete hydatidiform mole. The woman was discharged home in good general condition with a plan for serial beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) follow-up. Complete follow-up includes use of contraception and follow-up after beta-hCG is negative for a year.

Keywords: obstetrics and gynaecology; pregnancy; reproductive medicine.

© BMJ Publishing Group Limited 2018. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by BMJ.

Publication types

- Case Reports

- Abdominal Pain / etiology

- Blood Transfusion

- Cholangiopancreatography, Endoscopic Retrograde

- Chorionic Gonadotropin, beta Subunit, Human / blood

- Hydatidiform Mole / complications

- Hydatidiform Mole / diagnosis*

- Hydatidiform Mole / therapy

- Laparoscopy

- Ultrasonography

- Uterine Hemorrhage / etiology

- Uterine Neoplasms / complications

- Uterine Neoplasms / diagnosis*

- Uterine Neoplasms / therapy

- Chorionic Gonadotropin, beta Subunit, Human

- Open access

- Published: 03 September 2022

Molar pregnancy with a coexisting living fetus: a case series

- Reda Hemida ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0841-0242 1 ,

- Eman Khashaba 2 &

- Khaled Zalata 3

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 22 , Article number: 681 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

4997 Accesses

5 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Coexistence of molar pregnancy with living fetus represents a challenge in diagnosis and treatment. The objective of this study to present the outcome of molar pregnancy with a coexisting living fetus who were managed in our University Hospital in the last 5 years.

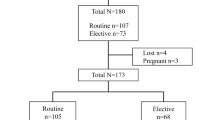

We performed a retrospective analysis of patients who presented with molar pregnancy with a coexisting living fetus to our Gestational Trophoblastic Clinic, Mansoura University, Egypt from September, 2015 to August, 2020. Clinical characteristics of the patients, maternal complications as well as fetal outcome were recorded. The patients and their living babies were also followed up at least 6 months after delivery.

Twelve pregnancies were analyzed. The mean maternal age was 26.0 (SD 4.1) years and the median parity was 1.0 (range 0–3). Duration of the pregnancies ranged from 14 to 36 weeks. The median serum hCG was 165,210.0 U/L (range 7662–1,200,000). Three fetuses survived outside the uterus (25%), one of them died after 5 months because of congenital malformations. Histologic diagnosis was available for 10 of 12 cases and revealed complete mole associated with a normal placenta in 6 cases (60%) and partial mole in 4 cases (40%). Maternal complications occurred in 6 cases (50%) with the most common was severe vaginal bleeding in 4 cases (33.3%). There was no significant association between B-hCG levels and maternal complications ( P = 0.3).

Maternal and fetal outcomes of molar pregnancy with a living fetus are poor. Counseling the patients for termination of pregnancy may be required.

Trial registration

The study was approved by Institutional Research Board (IRB), Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University (number: R.21.10.1492).

Peer Review reports

Introduction

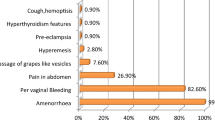

Hydatidiform mole is a rare complication of early pregnancy characterized by disordered proliferation of trophoblastic epithelium and villous edema. It includes complete (CHM) and partial (PHM) hydatidiform moles [ 1 , 2 ]. Partial hydatidiform mole arises as a result of dispermic fertilization of a haploid oocyte, which produces a triploid set of chromosomes and is commonly associated with congenital fetal malformations [ 3 ]. Hydatidiform moles are usually presented with first trimester vaginal bleeding, passage of vesicles, abdominal pain, excessive nausea and vomiting, and rapid abdominal enlargement [ 1 ]. Hyperthyroidism and preeclampsia may be present in some cases of complete hydatidiform moles [ 4 , 5 ]. Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) level is elevated but the level in CHM is higher than PHM [ 6 ].

Although complete hydatidiform moles can be easily diagnosed using routine ultrasound assessments early in the first trimester by appearance of snow-storm appearance of the placenta; PHM may mimic missed or incomplete abortion [ 7 ].

During management of molar pregnancy with a coexisting living fetus; the gynecologist should remind that there are three different types. The most common is twin pregnancy with one normal fetus with a normal placenta and a CHM; the second type is twin pregnancy with a normal fetus and placenta and a PHM; and the third, and most uncommon, is a singleton pregnancy consisting of a normal fetus and a placenta with PM changes [ 8 ]. The latter type was reported to occur in 0.005 to 0.01% of all pregnancies [ 9 ]. It is sometimes called “Sad Fetus Syndrome” [ 7 ]. Pregnancy with a PHM and a normal fetus evolves to a viable fetus in less than 25% of cases [ 8 ]. Such pregnancy has little tendency to invade the myometrium and distant metastasis [ 6 ].

Coexistence of molar changes with an apparently healthy fetus is unusual in a case of familial recurrent hydatidiform mole (FRHM). It should be differentiated from mesenchymal dysplasia by morphologic features and immunohistochemistry [ 10 ].

To the best of our knowledge, there are no available international guidelines for management of molar pregnancy with a living fetus. The available publications are mostly case reports, so the authors prepared this manuscript to present the experience of our University GTD referral clinic in the management and outcome of these rare cases.

Patients and methods

In this case series; a retrospective analysis of the patients presented with molar pregnancy with a coexisting living fetus to Gestational Trophoblastic Clinic, Mansoura University, Egypt in 5 years (from September, 2015 to August, 2020). The data of the patients were extracted from the computer and paper files. We included all cases above 18 years with diagnosed molar pregnancy with a living fetus based on clinical, ultrasound, and serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) criteria. The patients who refused to give initial permission to use their data in future research where excluded from the study.

Clinical characteristics including age, parity, obstetric history, gestational age, presenting symptoms, serum hCG on initial diagnosis, and family history, were all recorded. Mode of termination of pregnancy (miscarriage, induction of abortion, hysterotomy, vaginal, or caesarean delivery) was also reported.

Maternal complications during pregnancy, labor, and puerperium were described. Fetal outcomes (miscarriage, congenital fetal malformations, prematurity, or normal) were reported. The patients and living babies were followed up at least for 6 months after delivery .

The study was approved by Institutional Research Board (IRB), Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University (number: R.21.10.1492). The excel data and figures are anonymous.

Statistical analysis

Data entry and analysis was done using SPSS program, version 23.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) was used to analyze the findings. The qualitative data were described in number and percentage. The quantitative data with normal distribution were described in mean and the standard deviation ( \(\pm\) SD). Discrete variables were summarized in median and range. Contingency coefficient Chi square was used to compare nominal variables. The statistical significance was considered when P value was less than 0.05.

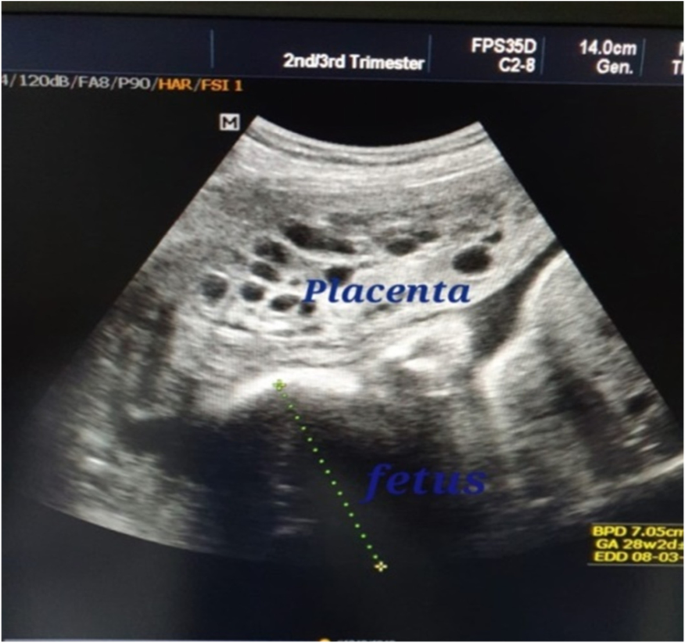

From September 2015 to August, 2020; twelve cases of molar pregnancy with living fetus were managed in our hospital. The mean maternal age was 26.0 ( \(\pm\) SD 4.1) years while median parity was 1.0 (range 0–3). Duration of pregnancy ranged from 14 to 36 weeks. The median serum hCG at time of diagnosis was 165,210.0 U/L (range 7662–1,200,000). Ultrasound reports showed well-defined multicystic snowstorm-like mass connecting with placenta (Fig. 1 ). Amniocentesis was performed in one case and revealed a normal diploid female karyotype. During antenatal follow up, the patients who had no complications and requested to undergo conservative treatment were given two injections of 12 mg of betamethasone 24 h apart from 28 weeks of gestation to prevent respiratory distress syndrome.

Ultrasound picture of pregnancy of the case (Z) at 28 weeks showing normal fetus with multiple variable-sized vesicles that cannot be separated from another placenta. The fetus is looking morphologically normal

The fetal outcomes are shown in Table 1 ; as can be noticed that fetuses survived outside the uterus in three cases (25%). The first two cases were delivered by caesarean delivery at 33 and 36 weeks of gestation after development of persistent abdominal pain and dyspnea with marked abdominal enlargement. Polyhydramnios was excluded by ultrasound examination. The third case delivered vaginally at 36 weeks of a neonate with multiple congenital anomalies namely hydrocephalus and macroglossia who died after 5 months. Seven cases continued their pregnancy beyond 20 weeks; five of them delivered prematurely (71.4%). only one case of them survived after neonatal care admission.

For the cases who were subjected to cesarean delivery or hysterectomy; the presence of multiple “grape” vesicles on the maternal surface of the placenta was observed.

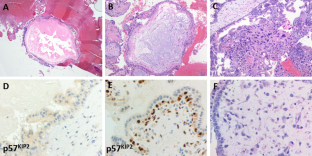

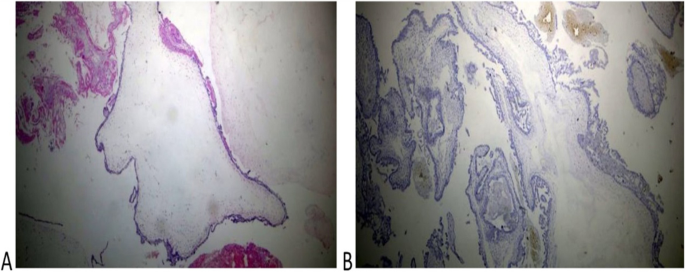

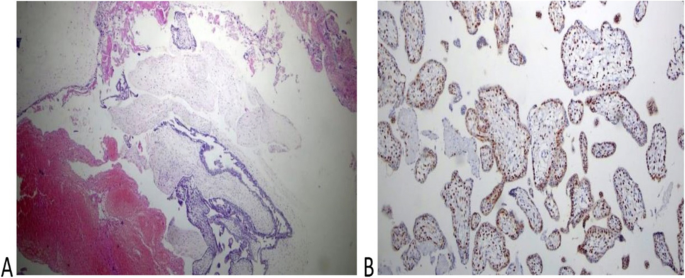

Histologic diagnosis was available for 10 of 12 cases and revealed complete mole associated with a normal placenta in 6 cases (60%) and partial mole in 4 cases (40%)( Figs. 2 and 3 ). Immunohistochemistry for P57 gene was performed on two cases (Figs. 2 and 3 ). The first delivered a phenotypically normal alive female baby and its placenta was misdiagnosed as PHM by morphological evaluation but the cytotrophoblast was negative for p57 immunestaining. The second case was diagnosed as dichorionic twins early in pregnancy that was terminated at 14 weeks of gestation because of severe vaginal bleeding. The fetus was phenotypically normal, placenta was histologically normal, and its cytotrophoblast was positive for p57. In addition, there was large amount of molar tissues that was negative for p57 immunostaining demonstrating a diagnosis of a CHM. These data suggest that this conception consists of a dichorionic twins with a living fetus with normal placenta and a CHM (Figs. 2 and 3 ).

Histopathological examination of the coexistent molar tissues of the case (Z): A Complete hydatidiform mole. The picture shows a dilated trophoblastic villous with cistern formation and trophoblastic epithelium hyperplasia (H&E × 100). B Complete hydatidiform mole. The picture shows a negative reaction to p57 IHC (Peroxidase × 100)

Histopathology of the placenta of the second twin of the case (H): A The picture shows normal trophoblastic villi (H&EX100). B P57 immunestaining of the same case shows a diffuse positive reaction in both trophoblastic and stromal cells (Peroxidase × 100)

Maternal complications occurred in 6 cases (50%) with the most common was severe uterine bleeding that was observed in 4 cases (33.3%). Other maternal complications are listed in Table 1 .

Moreover, three of our patients had familial recurrent hydatidiform mole (FRHM).Two of them are sisters. Genetic study through DNA sequencing confirmed NLRP7 mutations that were previously reported [ 11 ]. One of them experienced molar pregnancy with living fetus 3 times when she was aged 25, 27, and 28 years old.

We did not find a significant association between B-hCG level (when considered less than 500,000 and equal or more than 500,000 Unit/liter) and occurrence of maternal complications ( P = 0.3).

Coexistent molar pregnancy with a living fetus represents a diagnostic and management challenge particularly when the couple is interested to continue pregnancy. In a literature review published by Kawasaki et al. [ 8 ]; eighteen cases of molar pregnancies a coexisting living fetus were reported. The mean gestational age at delivery was 24.5 weeks, and only four fetuses could survive outside the uterus (22.2%) indicating a poor fetal outcome. On karyotyping; placenta was diploid in ten cases, indicating that they may be a CHM in a twin pregnancy or associated placental mesenchymal dysplasia that was also reported by Hojberg et al. [ 12 ].

The patients with molar pregnancy with coexistent living fetus who were managed in our university hospital in the last 5 years were presented in this report. Among the 12 reviewed pregnancies; three fetuses survived outside the uterus (25%). However, one of them died after 5 months because of congenital malformations that were reported by other authors [ 3 ]. The overall fetal survival in our series is less than reported in the literature review [ 8 ]. Moreover, Giorgione et al. [ 13 ] reported that overall neonatal survival in their series was 45% (5 of 11); the difference may be related to different patient criteria and neonatal care facilities in different hospitals. Among seven pregnancies continued beyond 20 weeks; five ended in premature deliveries (71.4%), which is much higher than the reported global incidence of prematurity allover pregnancies of 11% [ 14 ].

Amniocentesis is recommended for cases undergoing conservative treatment to exclude chromosomal abnormalities [ 15 ], however, it was performed only in one case in our series. Nine ladies refused the procedure for fear of complications while early pregnancy termination before time of amniocentesis was performed for two patients. In other series [ 13 ], prenatal invasive procedures were performed in 8 of 13 cases (62%). The acceptability of the pregnant ladies to perform prenatal invasive procedures differs from a community to another.

We reported occurrence of maternal complications in 50% of the studied cases; the commonest was severe vaginal bleeding. Although Sánchez-Ferrer et al. [ 15 ] concluded that termination of pregnancy is not indicated if the fetus is normal and continuation to birth is possible in nearly 60% of cases with no increase in maternal risks when the patient is closely monitored after birth until B-hCG is negative. The difference may be due to different number of cases in each study.

Moreover, two of the managed cases (16.7%) were complicated with early-onset preeclampsia and subsequently the pregnancy was terminated at 22 and 14 weeks of gestation. This finding was also reported by Kawasaki et al. [ 8 ]. In our series, we observed one case of complete mole that progressed to GTN (8.3%) and was successfully treated with single-agent chemotherapy, which is similar to a previous case scenario reported by Peng et al. [ 16 ].

The diagnostic challenge of a case of molar pregnancy with a coexisting living fetus is to differentiate two different conditions; singleton conception with a partial mole and dizygotic twins consisting of normal fetus with a complete mole. If the ultrasound picture of a normal fetus of an appropriate size for its gestational age together with an abnormal cystic placenta, a twin pregnancy consisting of a normal fetus and a CHM should be suspected [ 17 ]. Shaaban et al. [ 18 ] suggested that the peculiar “twin peak” sign in ultrasound, in which chorionic tissues extend into the inter-twin membrane, forming a triangular echogenic structure that intervenes the normal twin sac and the molar pregnancy, confirming the presence of a dichorionic twin gestation.

P57 immunestaining was performed in 2 cases of molar pregnancy with apparently normal fetus (Figs. 2 and 3 ) that confirmed these cases had a dichorionic twin pregnancy consisting of a complete mole with a co-twin of normal fetus and placenta. However, these cases may have been misdiagnosed as partial mole especially when the first ultrasound was done late in pregnancy. Other authors also reported cases of term deliveries of a complete hydatidiform mole with a coexisting living fetus [ 16 , 19 , 20 ].

We did not find a significant association between B-hCG level (when considered less than 500,000 and equal or more than 500,000 Unit/liter) and occurrence of maternal complications ( P = 0.3). This finding was in agree with Chale-Matsau et al. [ 21 ] who concluded that the β-hCG levels do not always correlate with disease severity and prognosis in patients with GTD.

With respect to the reported maternal and fetal complications in our study and other reports, it is necessary to fully inform the pregnant woman of the possible maternal and fetal complications, such as preeclampsia, hyperthyroidism, vaginal bleeding, and theca lutein ovarian cysts. The probability of postpartum development into persistent trophoblastic disease is also high.

The limitations of this study are its retrospective design, limited number of cases, and availability immunohistochemical study of only two cases.

Maternal and fetal outcome of molar pregnancy with a living fetus is poor. The incidence of prematurity is high (71.4%). Counseling of the patients for termination of pregnancy may be need. A global guideline for management is required.

Availability of data and materials

Original data and materials are available on request after contacting the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia

Complete hydatidiform mole

Partial hydatidiform mole

B subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin

Standard deviation

Lurain JR. Gestational trophoblastic disease I: epidemiology, pathology, clinical presentation and diagnosis of gestational trophoblastic disease, and management of hydatidiform mole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(6):531–9.

Article Google Scholar

Seckl M, Sebire N, Fisher R, Golfier F, Massuger L, Sessa C, et al. Gestational trophoblastic disease: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(suppl_6):vi39–50.

Stevens FT, Katzorke N, Tempfer C, Kreimer U, Bizjak GI, Fleisch MC, Fehm TN. Gestational Trophoblastic Disorders: An Update in 2015. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2015;75(10):1043–50.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Walkington L, Webster J, Hancock BW, Everard J, Coleman RE. Hyperthyroidism and human chorionic gonadotrophin production in gestational trophoblastic disease. Br J Cancer. 2011;104(11):1665–9.

Iriyama T, Wang G, Yoshikawa M, et al. Increased LIGHT leading to sFlt-1 elevation underlies the pathogenic link between hydatidiform mole and preeclampsia. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):10107.

Soper JT. Gestational Trophoblastic Disease: Current Evaluation and Management. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137(2):355–70.

Rathod AD, Pajai SP, Gaddikeri A. Partial mole with a coexistent viable fetus—a clinical dilemma: a case report with review of literature. J South Asian Feder Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;6:51–5.

Kawasaki K, Kondoh E, Minamiguchi S, Matsuda F, Higasa K, Fujita K, Mogami H, Chigusa Y, Konishi I. Live-born diploid fetus complicated with partial molar pregnancy presenting with pre-eclampsia, maternal anemia, and seemingly huge placenta: A rare case of confined placental mosaicism and literature review. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2016;42(8):911–7.

Smith HO, Kohorn E, Cole LA. Choriocarcinoma and gestational trophoblastic disease. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2005;32(4):661–84.

Sebire NJ, Fisher RA. Partly molar pregnancies that are not partial moles: additional possibilities and implications. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2005;8(6):732–3.

Rezaei M, Suresh B, Bereke E, Hadipour Z, Aguinaga M, Qian JH, Bagga R, Fardaei M, Hemida R, Jagadeesh S, Majewski J, Slim R. Novel pathogenic variants in NLRP7, NLRP5 and PADI6 in patients with recurrent hydatidiform moles and reproductive failure. Clin Genet. 2021;99(6):823–8.

Højberg KE, Aagaard J, Henriques U, Sunde L. Placental vascular malformation with mesenchymal hyperplasia and a localized chorioangioma. A rarity simulating partial mole. Pathol Res Pract. 1994;190(8):808–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0344-0338(11)80429-2 (discussion 814).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Giorgione V, Cavoretto P, Cormio G, Valsecchi L, Vimercati A, De Gennaro A, Rabaiotti E, Candiani M, Mangili G. Prenatal Diagnosis of Twin Pregnancies with Complete Hydatidiform Mole and Coexistent Normal Fetus: A Series of 13 Cases. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2017;82(4):404–9.

Walani SR. Global burden of preterm birth. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020;150(1):31–3.

Sánchez-Ferrer ML, Ferri B, Almansa MT, Carbonel P, López-Expósito I, Minguela A, Abad L, Parrilla JJ. Partial mole with a diploid fetus: case study and literature review. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2009;25(3):354–8.

Peng HH, Huang KG, Chueh HY, Adlan AS, Chang SD, Lee CL. Term delivery of a complete hydatidiform mole with a coexisting living fetus followed by successful treatment of maternal metastatic gestational trophoblastic disease. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;53(3):397–400.

Kutuk MS, Ozgun MT, Dolanbay M, Batukan C, Uludag S, Basbug M. Sonographic findings and perinatal outcome of multiple pregnancies associating a complete hydatiform mole and a live fetus: a case series. J Clin Ultrasound. 2014;42(8):465–71.

Shaaban AM, Rezvani M, Haroun RR, et al. Gestational Trophoblastic Disease: Clinical and Imaging Features. Radiographics. 2017;37(2):681–700.

Sasaki Y, Ogawa K, Takahashi J, Okai T. Complete hydatidiform mole coexisting with a normal fetus delivered at 33 weeks of gestation and involving maternal lung metastasis: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2012;57(7–8):301–4 (PMID: 22838245).

PubMed Google Scholar

Malhotra N, Deka D, Takkar D, Kochar S, Goel S, Sharma MC. Hydatidiform mole with coexisting live foetus in dichorionic twin gestation. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;94:301–3.

Chale-Matsau B, Mokoena S, Kemp T, Pillay TS. Hyperthyroidism in molar pregnancy: β-HCG levels do not always reflect severity. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;511:24–7.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). No funding was received.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mansoura University, 35111 Elgomhuria street, Mansoura, Egypt

Reda Hemida

Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt

Eman Khashaba

Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt

Khaled Zalata

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

R.H: Conception of Idea, collection of data, and editing manuscript. E.K: Statistical analysis and editing manuscript. K.Z: Pathology revision, preparation of figures, and revision of manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Reda Hemida .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study was approved by Institutional Research Board (IRB), Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University (number: R.21.10.1492). An informed consent for participation in the study was obtained from all participants.

All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication