October 2, 2018

Do Violent Video Games Trigger Aggression?

A study tries to find whether slaughtering zombies with a virtual assault weapon translates into misbehavior when a teenager returns to reality

By Melinda Wenner Moyer

Getty Images

Intuitively, it makes sense Splatterhouse and Postal 2 would serve as virtual training sessions for teens, encouraging them to act out in ways that mimic game-related violence. But many studies have failed to find a clear connection between violent game play and belligerent behavior, and the controversy over whether the shoot-‘em-up world transfers to real life has persisted for years. A new study published on October 1 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences tries to resolve the controversy by weighing the findings of two dozen studies on the topic.

The meta-analysis does tie violent video games to a small increase in physical aggression among adolescents and preteens. Yet debate is by no means over. Whereas the analysis was undertaken to help settle the science on the issue, researchers still disagree on the real-world significance of the findings.

This new analysis attempted to navigate through the minefield of conflicting research. Many studies find gaming associated with increases in aggression, but others identify no such link. A small but vocal cadre of researchers have argued much of the work implicating video games has serious flaws in that, among other things, it measures the frequency of aggressive thoughts or language rather than physically aggressive behaviors like hitting or pushing, which have more real-world relevance.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Jay Hull, a social psychologist at Dartmouth College and a co-author on the new paper, has never been convinced by the critiques that have disparaged purported ties between gaming and aggression. “I just kept reading, over and over again, [these] criticisms of the literature and going, ‘that’s just not true,’” he says. So he and his colleagues designed the new meta-analysis to address these criticisms head-on and determine if they had merit.

Hull and colleagues pooled data from 24 studies that had been selected to avoid some of the criticisms leveled at earlier work. They only included research that measured the relationship between violent video game use and overt physical aggression. They also limited their analysis to studies that statistically controlled for several factors that could influence the relationship between gaming and subsequent behavior, such as age and baseline aggressive behavior.

Even with these constraints, their analysis found kids who played violent video games did become more aggressive over time. But the changes in behavior were not big. “According to traditional ways of looking at these numbers, it’s not a large effect—I would say it’s relatively small,” he says. But it’s “statistically reliable—it’s not by chance and not inconsequential.”

Their findings mesh with a 2015 literature review conducted by the American Psychological Association, which concluded violent video games worsen aggressive behavior in older children, adolescents and young adults. Together, Hull’s meta-analysis and the APA report help give clarity to the existing body of research, says Douglas Gentile, a developmental psychologist at Iowa State University who was not involved in conducting the meta-analysis. “Media violence is one risk factor for aggression,” he says. “It's not the biggest, it’s also not the smallest, but it’s worth paying attention to.”

Yet researchers who have been critical of links between games and violence contend Hull’s meta-analysis does not settle the issue. “They don’t find much. They just try to make it sound like they do,” says Christopher Ferguson, a psychologist at Stetson University in Florida, who has published papers questioning the link between violent video games and aggression.

Ferguson argues the degree to which video game use increases aggression in Hull’s analysis—what is known in psychology as the estimated “effect size”—is so small as to be essentially meaningless. After statistically controlling for several other factors, the meta-analysis reported an effect size of 0.08, which suggests that violent video games account for less than one percent of the variation in aggressive behavior among U.S. teens and pre-teens—if, in fact, there is a cause-and effect relationship between game play and hostile actions. It may instead be that the relationship between gaming and aggression is a statistical artifact caused by lingering flaws in study design, Ferguson says.

Johannes Breuer, a psychologist at GESIS–Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences in Germany, agrees, noting that according to “a common rule of thumb in psychological research,” effect sizes below 0.1 are “considered trivial.” He adds meta-analyses are only as valid as the studies included in them, and that work on the issue has been plagued by methodological problems. For one thing, studies vary in terms of the criteria they use to determine if a video game is violent or not. By some measures, the Super Mario Bros. games would be considered violent, but by others not. Studies, too, often rely on subjects self-reporting their own aggressive acts, and they may not do so accurately. “All of this is not to say that the results of this meta-analysis are not valid,” he says. “But things like this need to be kept in mind when interpreting the findings and discussing their meaning.”

Hull says, however, that the effect size his team found still has real-world significance. An analysis of one of his earlier studies, which reported a similar estimated effect size of 0.083, found playing violent video games was linked with almost double the risk that kids would be sent to the school principal’s office for fighting. The study began by taking a group of children who hadn’t been dispatched to the principal in the previous month and then tracked them for a subsequent eight months. It found 4.8 percent of kids who reported only rarely playing violent video games were sent to the principal’s office at least once during that period compared with 9 percent who reported playing violent video games frequently. Hull theorizes violent games help kids become more comfortable with taking risks and engaging in abnormal behavior. “Their sense of right and wrong is being warped,” he notes.

Hull and his colleagues also found evidence ethnicity shapes the relationship between violent video games and aggression. White players seem more susceptible to the games' putative effects on behavior than do Hispanic and Asian players. Hull isn’t sure why, but he suspects the games' varying impact relates to how much kids are influenced by the norms of American culture, which, he says, are rooted in rugged individualism and a warriorlike mentality that may incite video game players to identify with aggressors rather than victims. It might “dampen sympathy toward their virtual victims,” he and his co-authors wrote, “with consequences for their values and behavior outside the game.”

Social scientists will, no doubt, continue to debate the psychological impacts of killing within the confines of interactive games. In a follow-up paper Hull says he plans to tackle the issue of the real-world significance of violent game play, and hopes it adds additional clarity. “It’s a knotty issue,” he notes—and it’s an open question whether research will ever quell the controversy.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 13 March 2018

Does playing violent video games cause aggression? A longitudinal intervention study

- Simone Kühn 1 , 2 ,

- Dimitrij Tycho Kugler 2 ,

- Katharina Schmalen 1 ,

- Markus Weichenberger 1 ,

- Charlotte Witt 1 &

- Jürgen Gallinat 2

Molecular Psychiatry volume 24 , pages 1220–1234 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

548k Accesses

102 Citations

2341 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Neuroscience

It is a widespread concern that violent video games promote aggression, reduce pro-social behaviour, increase impulsivity and interfere with cognition as well as mood in its players. Previous experimental studies have focussed on short-term effects of violent video gameplay on aggression, yet there are reasons to believe that these effects are mostly the result of priming. In contrast, the present study is the first to investigate the effects of long-term violent video gameplay using a large battery of tests spanning questionnaires, behavioural measures of aggression, sexist attitudes, empathy and interpersonal competencies, impulsivity-related constructs (such as sensation seeking, boredom proneness, risk taking, delay discounting), mental health (depressivity, anxiety) as well as executive control functions, before and after 2 months of gameplay. Our participants played the violent video game Grand Theft Auto V, the non-violent video game The Sims 3 or no game at all for 2 months on a daily basis. No significant changes were observed, neither when comparing the group playing a violent video game to a group playing a non-violent game, nor to a passive control group. Also, no effects were observed between baseline and posttest directly after the intervention, nor between baseline and a follow-up assessment 2 months after the intervention period had ended. The present results thus provide strong evidence against the frequently debated negative effects of playing violent video games in adults and will therefore help to communicate a more realistic scientific perspective on the effects of violent video gaming.

Similar content being viewed by others

Microdosing with psilocybin mushrooms: a double-blind placebo-controlled study

Anger is eliminated with the disposal of a paper written because of provocation

Persistent interaction patterns across social media platforms and over time

The concern that violent video games may promote aggression or reduce empathy in its players is pervasive and given the popularity of these games their psychological impact is an urgent issue for society at large. Contrary to the custom, this topic has also been passionately debated in the scientific literature. One research camp has strongly argued that violent video games increase aggression in its players [ 1 , 2 ], whereas the other camp [ 3 , 4 ] repeatedly concluded that the effects are minimal at best, if not absent. Importantly, it appears that these fundamental inconsistencies cannot be attributed to differences in research methodology since even meta-analyses, with the goal to integrate the results of all prior studies on the topic of aggression caused by video games led to disparate conclusions [ 2 , 3 ]. These meta-analyses had a strong focus on children, and one of them [ 2 ] reported a marginal age effect suggesting that children might be even more susceptible to violent video game effects.

To unravel this topic of research, we designed a randomised controlled trial on adults to draw causal conclusions on the influence of video games on aggression. At present, almost all experimental studies targeting the effects of violent video games on aggression and/or empathy focussed on the effects of short-term video gameplay. In these studies the duration for which participants were instructed to play the games ranged from 4 min to maximally 2 h (mean = 22 min, median = 15 min, when considering all experimental studies reviewed in two of the recent major meta-analyses in the field [ 3 , 5 ]) and most frequently the effects of video gaming have been tested directly after gameplay.

It has been suggested that the effects of studies focussing on consequences of short-term video gameplay (mostly conducted on college student populations) are mainly the result of priming effects, meaning that exposure to violent content increases the accessibility of aggressive thoughts and affect when participants are in the immediate situation [ 6 ]. However, above and beyond this the General Aggression Model (GAM, [ 7 ]) assumes that repeatedly primed thoughts and feelings influence the perception of ongoing events and therewith elicits aggressive behaviour as a long-term effect. We think that priming effects are interesting and worthwhile exploring, but in contrast to the notion of the GAM our reading of the literature is that priming effects are short-lived (suggested to only last for <5 min and may potentially reverse after that time [ 8 ]). Priming effects should therefore only play a role in very close temporal proximity to gameplay. Moreover, there are a multitude of studies on college students that have failed to replicate priming effects [ 9 , 10 , 11 ] and associated predictions of the so-called GAM such as a desensitisation against violent content [ 12 , 13 , 14 ] in adolescents and college students or a decrease of empathy [ 15 ] and pro-social behaviour [ 16 , 17 ] as a result of playing violent video games.

However, in our view the question that society is actually interested in is not: “Are people more aggressive after having played violent video games for a few minutes? And are these people more aggressive minutes after gameplay ended?”, but rather “What are the effects of frequent, habitual violent video game playing? And for how long do these effects persist (not in the range of minutes but rather weeks and months)?” For this reason studies are needed in which participants are trained over longer periods of time, tested after a longer delay after acute playing and tested with broader batteries assessing aggression but also other relevant domains such as empathy as well as mood and cognition. Moreover, long-term follow-up assessments are needed to demonstrate long-term effects of frequent violent video gameplay. To fill this gap, we set out to expose adult participants to two different types of video games for a period of 2 months and investigate changes in measures of various constructs of interest at least one day after the last gaming session and test them once more 2 months after the end of the gameplay intervention. In contrast to the GAM, we hypothesised no increases of aggression or decreases in pro-social behaviour even after long-term exposure to a violent video game due to our reasoning that priming effects of violent video games are short-lived and should therefore not influence measures of aggression if they are not measured directly after acute gaming. In the present study, we assessed potential changes in the following domains: behavioural as well as questionnaire measures of aggression, empathy and interpersonal competencies, impulsivity-related constructs (such as sensation seeking, boredom proneness, risk taking, delay discounting), and depressivity and anxiety as well as executive control functions. As the effects on aggression and pro-social behaviour were the core targets of the present study, we implemented multiple tests for these domains. This broad range of domains with its wide coverage and the longitudinal nature of the study design enabled us to draw more general conclusions regarding the causal effects of violent video games.

Materials and methods

Participants.

Ninety healthy participants (mean age = 28 years, SD = 7.3, range: 18–45, 48 females) were recruited by means of flyers and internet advertisements. The sample consisted of college students as well as of participants from the general community. The advertisement mentioned that we were recruiting for a longitudinal study on video gaming, but did not mention that we would offer an intervention or that we were expecting training effects. Participants were randomly assigned to the three groups ruling out self-selection effects. The sample size was based on estimates from a previous study with a similar design [ 18 ]. After complete description of the study, the participants’ informed written consent was obtained. The local ethics committee of the Charité University Clinic, Germany, approved of the study. We included participants that reported little, preferably no video game usage in the past 6 months (none of the participants ever played the game Grand Theft Auto V (GTA) or Sims 3 in any of its versions before). We excluded participants with psychological or neurological problems. The participants received financial compensation for the testing sessions (200 Euros) and performance-dependent additional payment for two behavioural tasks detailed below, but received no money for the training itself.

Training procedure

The violent video game group (5 participants dropped out between pre- and posttest, resulting in a group of n = 25, mean age = 26.6 years, SD = 6.0, 14 females) played the game Grand Theft Auto V on a Playstation 3 console over a period of 8 weeks. The active control group played the non-violent video game Sims 3 on the same console (6 participants dropped out, resulting in a group of n = 24, mean age = 25.8 years, SD = 6.8, 12 females). The passive control group (2 participants dropped out, resulting in a group of n = 28, mean age = 30.9 years, SD = 8.4, 12 females) was not given a gaming console and had no task but underwent the same testing procedure as the two other groups. The passive control group was not aware of the fact that they were part of a control group to prevent self-training attempts. The experimenters testing the participants were blind to group membership, but we were unable to prevent participants from talking about the game during testing, which in some cases lead to an unblinding of experimental condition. Both training groups were instructed to play the game for at least 30 min a day. Participants were only reimbursed for the sessions in which they came to the lab. Our previous research suggests that the perceived fun in gaming was positively associated with training outcome [ 18 ] and we speculated that enforcing training sessions through payment would impair motivation and thus diminish the potential effect of the intervention. Participants underwent a testing session before (baseline) and after the training period of 2 months (posttest 1) as well as a follow-up testing sessions 2 months after the training period (posttest 2).

Grand Theft Auto V (GTA)

GTA is an action-adventure video game situated in a fictional highly violent game world in which players are rewarded for their use of violence as a means to advance in the game. The single-player story follows three criminals and their efforts to commit heists while under pressure from a government agency. The gameplay focuses on an open world (sandbox game) where the player can choose between different behaviours. The game also allows the player to engage in various side activities, such as action-adventure, driving, third-person shooting, occasional role-playing, stealth and racing elements. The open world design lets players freely roam around the fictional world so that gamers could in principle decide not to commit violent acts.

The Sims 3 (Sims)

Sims is a life simulation game and also classified as a sandbox game because it lacks clearly defined goals. The player creates virtual individuals called “Sims”, and customises their appearance, their personalities and places them in a home, directs their moods, satisfies their desires and accompanies them in their daily activities and by becoming part of a social network. It offers opportunities, which the player may choose to pursue or to refuse, similar as GTA but is generally considered as a pro-social and clearly non-violent game.

Assessment battery

To assess aggression and associated constructs we used the following questionnaires: Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire [ 19 ], State Hostility Scale [ 20 ], Updated Illinois Rape Myth Acceptance Scale [ 21 , 22 ], Moral Disengagement Scale [ 23 , 24 ], the Rosenzweig Picture Frustration Test [ 25 , 26 ] and a so-called World View Measure [ 27 ]. All of these measures have previously been used in research investigating the effects of violent video gameplay, however, the first two most prominently. Additionally, behavioural measures of aggression were used: a Word Completion Task, a Lexical Decision Task [ 28 ] and the Delay frustration task [ 29 ] (an inter-correlation matrix is depicted in Supplementary Figure 1 1). From these behavioural measures, the first two were previously used in research on the effects of violent video gameplay. To assess variables that have been related to the construct of impulsivity, we used the Brief Sensation Seeking Scale [ 30 ] and the Boredom Propensity Scale [ 31 ] as well as tasks assessing risk taking and delay discounting behaviourally, namely the Balloon Analogue Risk Task [ 32 ] and a Delay-Discounting Task [ 33 ]. To quantify pro-social behaviour, we employed: Interpersonal Reactivity Index [ 34 ] (frequently used in research on the effects of violent video gameplay), Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale [ 35 ], Reading the Mind in the Eyes test [ 36 ], Interpersonal Competence Questionnaire [ 37 ] and Richardson Conflict Response Questionnaire [ 38 ]. To assess depressivity and anxiety, which has previously been associated with intense video game playing [ 39 ], we used Beck Depression Inventory [ 40 ] and State Trait Anxiety Inventory [ 41 ]. To characterise executive control function, we used a Stop Signal Task [ 42 ], a Multi-Source Interference Task [ 43 ] and a Task Switching Task [ 44 ] which have all been previously used to assess effects of video gameplay. More details on all instruments used can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Data analysis

On the basis of the research question whether violent video game playing enhances aggression and reduces empathy, the focus of the present analysis was on time by group interactions. We conducted these interaction analyses separately, comparing the violent video game group against the active control group (GTA vs. Sims) and separately against the passive control group (GTA vs. Controls) that did not receive any intervention and separately for the potential changes during the intervention period (baseline vs. posttest 1) and to test for potential long-term changes (baseline vs. posttest 2). We employed classical frequentist statistics running a repeated-measures ANOVA controlling for the covariates sex and age.

Since we collected 52 separate outcome variables and conduced four different tests with each (GTA vs. Sims, GTA vs. Controls, crossed with baseline vs. posttest 1, baseline vs. posttest 2), we had to conduct 52 × 4 = 208 frequentist statistical tests. Setting the alpha value to 0.05 means that by pure chance about 10.4 analyses should become significant. To account for this multiple testing problem and the associated alpha inflation, we conducted a Bonferroni correction. According to Bonferroni, the critical value for the entire set of n tests is set to an alpha value of 0.05 by taking alpha/ n = 0.00024.

Since the Bonferroni correction has sometimes been criticised as overly conservative, we conducted false discovery rate (FDR) correction [ 45 ]. FDR correction also determines adjusted p -values for each test, however, it controls only for the number of false discoveries in those tests that result in a discovery (namely a significant result).

Moreover, we tested for group differences at the baseline assessment using independent t -tests, since those may hamper the interpretation of significant interactions between group and time that we were primarily interested in.

Since the frequentist framework does not enable to evaluate whether the observed null effect of the hypothesised interaction is indicative of the absence of a relation between violent video gaming and our dependent variables, the amount of evidence in favour of the null hypothesis has been tested using a Bayesian framework. Within the Bayesian framework both the evidence in favour of the null and the alternative hypothesis are directly computed based on the observed data, giving rise to the possibility of comparing the two. We conducted Bayesian repeated-measures ANOVAs comparing the model in favour of the null and the model in favour of the alternative hypothesis resulting in a Bayes factor (BF) using Bayesian Information criteria [ 46 ]. The BF 01 suggests how much more likely the data is to occur under the null hypothesis. All analyses were performed using the JASP software package ( https://jasp-stats.org ).

Sex distribution in the present study did not differ across the groups ( χ 2 p -value > 0.414). However, due to the fact that differences between males and females have been observed in terms of aggression and empathy [ 47 ], we present analyses controlling for sex. Since our random assignment to the three groups did result in significant age differences between groups, with the passive control group being significantly older than the GTA ( t (51) = −2.10, p = 0.041) and the Sims group ( t (50) = −2.38, p = 0.021), we also controlled for age.

The participants in the violent video game group played on average 35 h and the non-violent video game group 32 h spread out across the 8 weeks interval (with no significant group difference p = 0.48).

To test whether participants assigned to the violent GTA game show emotional, cognitive and behavioural changes, we present the results of repeated-measure ANOVA time x group interaction analyses separately for GTA vs. Sims and GTA vs. Controls (Tables 1 – 3 ). Moreover, we split the analyses according to the time domain into effects from baseline assessment to posttest 1 (Table 2 ) and effects from baseline assessment to posttest 2 (Table 3 ) to capture more long-lasting or evolving effects. In addition to the statistical test values, we report partial omega squared ( ω 2 ) as an effect size measure. Next to the classical frequentist statistics, we report the results of a Bayesian statistical approach, namely BF 01 , the likelihood with which the data is to occur under the null hypothesis that there is no significant time × group interaction. In Table 2 , we report the presence of significant group differences at baseline in the right most column.

Since we conducted 208 separate frequentist tests we expected 10.4 significant effects simply by chance when setting the alpha value to 0.05. In fact we found only eight significant time × group interactions (these are marked with an asterisk in Tables 2 and 3 ).

When applying a conservative Bonferroni correction, none of those tests survive the corrected threshold of p < 0.00024. Neither does any test survive the more lenient FDR correction. The arithmetic mean of the frequentist test statistics likewise shows that on average no significant effect was found (bottom rows in Tables 2 and 3 ).

In line with the findings from a frequentist approach, the harmonic mean of the Bayesian factor BF 01 is consistently above one but not very far from one. This likewise suggests that there is very likely no interaction between group × time and therewith no detrimental effects of the violent video game GTA in the domains tested. The evidence in favour of the null hypothesis based on the Bayes factor is not massive, but clearly above 1. Some of the harmonic means are above 1.6 and constitute substantial evidence [ 48 ]. However, the harmonic mean has been criticised as unstable. Owing to the fact that the sum is dominated by occasional small terms in the likelihood, one may underestimate the actual evidence in favour of the null hypothesis [ 49 ].

To test the sensitivity of the present study to detect relevant effects we computed the effect size that we would have been able to detect. The information we used consisted of alpha error probability = 0.05, power = 0.95, our sample size, number of groups and of measurement occasions and correlation between the repeated measures at posttest 1 and posttest 2 (average r = 0.68). According to G*Power [ 50 ], we could detect small effect sizes of f = 0.16 (equals η 2 = 0.025 and r = 0.16) in each separate test. When accounting for the conservative Bonferroni-corrected p -value of 0.00024, still a medium effect size of f = 0.23 (equals η 2 = 0.05 and r = 0.22) would have been detectable. A meta-analysis by Anderson [ 2 ] reported an average effects size of r = 0.18 for experimental studies testing for aggressive behaviour and another by Greitmeyer [ 5 ] reported average effect sizes of r = 0.19, 0.25 and 0.17 for effects of violent games on aggressive behaviour, cognition and affect, all of which should have been detectable at least before multiple test correction.

Within the scope of the present study we tested the potential effects of playing the violent video game GTA V for 2 months against an active control group that played the non-violent, rather pro-social life simulation game The Sims 3 and a passive control group. Participants were tested before and after the long-term intervention and at a follow-up appointment 2 months later. Although we used a comprehensive test battery consisting of questionnaires and computerised behavioural tests assessing aggression, impulsivity-related constructs, mood, anxiety, empathy, interpersonal competencies and executive control functions, we did not find relevant negative effects in response to violent video game playing. In fact, only three tests of the 208 statistical tests performed showed a significant interaction pattern that would be in line with this hypothesis. Since at least ten significant effects would be expected purely by chance, we conclude that there were no detrimental effects of violent video gameplay.

This finding stands in contrast to some experimental studies, in which short-term effects of violent video game exposure have been investigated and where increases in aggressive thoughts and affect as well as decreases in helping behaviour have been observed [ 1 ]. However, these effects of violent video gaming on aggressiveness—if present at all (see above)—seem to be rather short-lived, potentially lasting <15 min [ 8 , 51 ]. In addition, these short-term effects of video gaming are far from consistent as multiple studies fail to demonstrate or replicate them [ 16 , 17 ]. This may in part be due to problems, that are very prominent in this field of research, namely that the outcome measures of aggression and pro-social behaviour, are poorly standardised, do not easily generalise to real-life behaviour and may have lead to selective reporting of the results [ 3 ]. We tried to address these concerns by including a large set of outcome measures that were mostly inspired by previous studies demonstrating effects of short-term violent video gameplay on aggressive behaviour and thoughts, that we report exhaustively.

Since effects observed only for a few minutes after short sessions of video gaming are not representative of what society at large is actually interested in, namely how habitual violent video gameplay affects behaviour on a more long-term basis, studies employing longer training intervals are highly relevant. Two previous studies have employed longer training intervals. In an online study, participants with a broad age range (14–68 years) have been trained in a violent video game for 4 weeks [ 52 ]. In comparison to a passive control group no changes were observed, neither in aggression-related beliefs, nor in aggressive social interactions assessed by means of two questions. In a more recent study, participants played a previous version of GTA for 12 h spread across 3 weeks [ 53 ]. Participants were compared to a passive control group using the Buss–Perry aggression questionnaire, a questionnaire assessing impulsive or reactive aggression, attitude towards violence, and empathy. The authors only report a limited increase in pro-violent attitude. Unfortunately, this study only assessed posttest measures, which precludes the assessment of actual changes caused by the game intervention.

The present study goes beyond these studies by showing that 2 months of violent video gameplay does neither lead to any significant negative effects in a broad assessment battery administered directly after the intervention nor at a follow-up assessment 2 months after the intervention. The fact that we assessed multiple domains, not finding an effect in any of them, makes the present study the most comprehensive in the field. Our battery included self-report instruments on aggression (Buss–Perry aggression questionnaire, State Hostility scale, Illinois Rape Myth Acceptance scale, Moral Disengagement scale, World View Measure and Rosenzweig Picture Frustration test) as well as computer-based tests measuring aggressive behaviour such as the delay frustration task and measuring the availability of aggressive words using the word completion test and a lexical decision task. Moreover, we assessed impulse-related concepts such as sensation seeking, boredom proneness and associated behavioural measures such as the computerised Balloon analogue risk task, and delay discounting. Four scales assessing empathy and interpersonal competence scales, including the reading the mind in the eyes test revealed no effects of violent video gameplay. Neither did we find any effects on depressivity (Becks depression inventory) nor anxiety measured as a state as well as a trait. This is an important point, since several studies reported higher rates of depressivity and anxiety in populations of habitual video gamers [ 54 , 55 ]. Last but not least, our results revealed also no substantial changes in executive control tasks performance, neither in the Stop signal task, the Multi-source interference task or a Task switching task. Previous studies have shown higher performance of habitual action video gamers in executive tasks such as task switching [ 56 , 57 , 58 ] and another study suggests that training with action video games improves task performance that relates to executive functions [ 59 ], however, these associations were not confirmed by a meta-analysis in the field [ 60 ]. The absence of changes in the stop signal task fits well with previous studies that likewise revealed no difference between in habitual action video gamers and controls in terms of action inhibition [ 61 , 62 ]. Although GTA does not qualify as a classical first-person shooter as most of the previously tested action video games, it is classified as an action-adventure game and shares multiple features with those action video games previously related to increases in executive function, including the need for hand–eye coordination and fast reaction times.

Taken together, the findings of the present study show that an extensive game intervention over the course of 2 months did not reveal any specific changes in aggression, empathy, interpersonal competencies, impulsivity-related constructs, depressivity, anxiety or executive control functions; neither in comparison to an active control group that played a non-violent video game nor to a passive control group. We observed no effects when comparing a baseline and a post-training assessment, nor when focussing on more long-term effects between baseline and a follow-up interval 2 months after the participants stopped training. To our knowledge, the present study employed the most comprehensive test battery spanning a multitude of domains in which changes due to violent video games may have been expected. Therefore the present results provide strong evidence against the frequently debated negative effects of playing violent video games. This debate has mostly been informed by studies showing short-term effects of violent video games when tests were administered immediately after a short playtime of a few minutes; effects that may in large be caused by short-lived priming effects that vanish after minutes. The presented results will therefore help to communicate a more realistic scientific perspective of the real-life effects of violent video gaming. However, future research is needed to demonstrate the absence of effects of violent video gameplay in children.

Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. Effects of violent video games on aggressive behavior, aggressive cognition, aggressive affect, physiological arousal, and prosocial behavior: a meta-analytic review of the scientific literature. Psychol Sci. 2001;12:353–9.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Anderson CA, Shibuya A, Ihori N, Swing EL, Bushman BJ, Sakamoto A, et al. Violent video game effects on aggression, empathy, and prosocial behavior in eastern and western countries: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2010;136:151–73.

Article Google Scholar

Ferguson CJ. Do angry birds make for angry children? A meta-analysis of video game influences on children’s and adolescents’ aggression, mental health, prosocial behavior, and academic performance. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10:646–66.

Ferguson CJ, Kilburn J. Much ado about nothing: the misestimation and overinterpretation of violent video game effects in eastern and western nations: comment on Anderson et al. (2010). Psychol Bull. 2010;136:174–8.

Greitemeyer T, Mugge DO. Video games do affect social outcomes: a meta-analytic review of the effects of violent and prosocial video game play. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2014;40:578–89.

Anderson CA, Carnagey NL, Eubanks J. Exposure to violent media: The effects of songs with violent lyrics on aggressive thoughts and feelings. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84:960–71.

DeWall CN, Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. The general aggression model: theoretical extensions to violence. Psychol Violence. 2011;1:245–58.

Sestire MA, Bartholow BD. Violent and non-violent video games produce opposing effects on aggressive and prosocial outcomes. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2010;46:934–42.

Kneer J, Elson M, Knapp F. Fight fire with rainbows: The effects of displayed violence, difficulty, and performance in digital games on affect, aggression, and physiological arousal. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;54:142–8.

Kneer J, Glock S, Beskes S, Bente G. Are digital games perceived as fun or danger? Supporting and suppressing different game-related concepts. Cyber Beh Soc N. 2012;15:604–9.

Sauer JD, Drummond A, Nova N. Violent video games: the effects of narrative context and reward structure on in-game and postgame aggression. J Exp Psychol Appl. 2015;21:205–14.

Ballard M, Visser K, Jocoy K. Social context and video game play: impact on cardiovascular and affective responses. Mass Commun Soc. 2012;15:875–98.

Read GL, Ballard M, Emery LJ, Bazzini DG. Examining desensitization using facial electromyography: violent video games, gender, and affective responding. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;62:201–11.

Szycik GR, Mohammadi B, Hake M, Kneer J, Samii A, Munte TF, et al. Excessive users of violent video games do not show emotional desensitization: an fMRI study. Brain Imaging Behav. 2017;11:736–43.

Szycik GR, Mohammadi B, Munte TF, Te Wildt BT. Lack of evidence that neural empathic responses are blunted in excessive users of violent video games: an fMRI study. Front Psychol. 2017;8:174.

Tear MJ, Nielsen M. Failure to demonstrate that playing violent video games diminishes prosocial behavior. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e68382.

Tear MJ, Nielsen M. Video games and prosocial behavior: a study of the effects of non-violent, violent and ultra-violent gameplay. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;41:8–13.

Kühn S, Gleich T, Lorenz RC, Lindenberger U, Gallinat J. Playing super Mario induces structural brain plasticity: gray matter changes resulting from training with a commercial video game. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:265–71.

Buss AH, Perry M. The aggression questionnaire. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63:452.

Anderson CA, Deuser WE, DeNeve KM. Hot temperatures, hostile affect, hostile cognition, and arousal: Tests of a general model of affective aggression. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1995;21:434–48.

Payne DL, Lonsway KA, Fitzgerald LF. Rape myth acceptance: exploration of its structure and its measurement using the illinois rape myth acceptance scale. J Res Pers. 1999;33:27–68.

McMahon S, Farmer GL. An updated measure for assessing subtle rape myths. Social Work Res. 2011; 35:71–81.

Detert JR, Trevino LK, Sweitzer VL. Moral disengagement in ethical decision making: a study of antecedents and outcomes. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93:374–91.

Bandura A, Barbaranelli C, Caprara G, Pastorelli C. Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;71:364–74.

Rosenzweig S. The picture-association method and its application in a study of reactions to frustration. J Pers. 1945;14:23.

Hörmann H, Moog W, Der Rosenzweig P-F. Test für Erwachsene deutsche Bearbeitung. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 1957.

Anderson CA, Dill KE. Video games and aggressive thoughts, feelings, and behavior in the laboratory and in life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78:772–90.

Przybylski AK, Deci EL, Rigby CS, Ryan RM. Competence-impeding electronic games and players’ aggressive feelings, thoughts, and behaviors. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2014;106:441.

Bitsakou P, Antrop I, Wiersema JR, Sonuga-Barke EJ. Probing the limits of delay intolerance: preliminary young adult data from the Delay Frustration Task (DeFT). J Neurosci Methods. 2006;151:38–44.

Hoyle RH, Stephenson MT, Palmgreen P, Lorch EP, Donohew RL. Reliability and validity of a brief measure of sensation seeking. Pers Individ Dif. 2002;32:401–14.

Farmer R, Sundberg ND. Boredom proneness: the development and correlates of a new scale. J Pers Assess. 1986;50:4–17.

Lejuez CW, Read JP, Kahler CW, Richards JB, Ramsey SE, Stuart GL, et al. Evaluation of a behavioral measure of risk taking: the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART). J Exp Psychol Appl. 2002;8:75–84.

Richards JB, Zhang L, Mitchell SH, de Wit H. Delay or probability discounting in a model of impulsive behavior: effect of alcohol. J Exp Anal Behav. 1999;71:121–43.

Davis MH. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Cat Sel Doc Psychol. 1980;10:85.

Google Scholar

Mehrabian A. Manual for the Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale (BEES). (Available from Albert Mehrabian, 1130 Alta Mesa Road, Monterey, CA, USA 93940); 1996.

Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Hill J, Raste Y, Plumb I. The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test revised version: A study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2001;42:241–51.

Buhrmester D, Furman W, Reis H, Wittenberg MT. Five domains of interpersonal competence in peer relations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;55:991–1008.

Richardson DR, Green LR, Lago T. The relationship between perspective-taking and non-aggressive responding in the face of an attack. J Pers. 1998;66:235–56.

Maras D, Flament MF, Murray M, Buchholz A, Henderson KA, Obeid N, et al. Screen time is associated with depression and anxiety in Canadian youth. Prev Med. 2015;73:133–8.

Hautzinger M, Bailer M, Worall H, Keller F. Beck-Depressions-Inventar (BDI). Beck-Depressions-Inventar (BDI): Testhandbuch der deutschen Ausgabe. Bern: Huber; 1995.

Spielberger CD, Spielberger CD, Sydeman SJ, Sydeman SJ, Owen AE, Owen AE, et al. Measuring anxiety and anger with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1999.

Lorenz RC, Gleich T, Buchert R, Schlagenhauf F, Kuhn S, Gallinat J. Interactions between glutamate, dopamine, and the neuronal signature of response inhibition in the human striatum. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36:4031–40.

Bush G, Shin LM. The multi-source interference task: an fMRI task that reliably activates the cingulo-frontal-parietal cognitive/attention network. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:308–13.

King JA, Colla M, Brass M, Heuser I, von Cramon D. Inefficient cognitive control in adult ADHD: evidence from trial-by-trial Stroop test and cued task switching performance. Behav Brain Funct. 2007;3:42.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc. 1995;57:289–300.

Wagenmakers E-J. A practical solution to the pervasive problems of p values. Psychon Bull Rev. 2007;14:779–804.

Hay DF. The gradual emergence of sex differences in aggression: alternative hypotheses. Psychol Med. 2007;37:1527–37.

Jeffreys H. The Theory of Probability. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1961.

Raftery AE, Newton MA, Satagopan YM, Krivitsky PN. Estimating the integrated likelihood via posterior simulation using the harmonic mean identity. In: Bernardo JM, Bayarri MJ, Berger JO, Dawid AP, Heckerman D, Smith AFM, et al., editors. Bayesian statistics. Oxford: University Press; 2007.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, Buchner A. G*Power3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–91.

Barlett C, Branch O, Rodeheffer C, Harris R. How long do the short-term violent video game effects last? Aggress Behav. 2009;35:225–36.

Williams D, Skoric M. Internet fantasy violence: a test of aggression in an online game. Commun Monogr. 2005;72:217–33.

Teng SK, Chong GY, Siew AS, Skoric MM. Grand theft auto IV comes to Singapore: effects of repeated exposure to violent video games on aggression. Cyber Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14:597–602.

van Rooij AJ, Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD, Shorter GW, Schoenmakers TM, Van, de Mheen D. The (co-)occurrence of problematic video gaming, substance use, and psychosocial problems in adolescents. J Behav Addict. 2014;3:157–65.

Brunborg GS, Mentzoni RA, Froyland LR. Is video gaming, or video game addiction, associated with depression, academic achievement, heavy episodic drinking, or conduct problems? J Behav Addict. 2014;3:27–32.

Green CS, Sugarman MA, Medford K, Klobusicky E, Bavelier D. The effect of action video game experience on task switching. Comput Hum Behav. 2012;28:984–94.

Strobach T, Frensch PA, Schubert T. Video game practice optimizes executive control skills in dual-task and task switching situations. Acta Psychol. 2012;140:13–24.

Colzato LS, van Leeuwen PJ, van den Wildenberg WP, Hommel B. DOOM’d to switch: superior cognitive flexibility in players of first person shooter games. Front Psychol. 2010;1:8.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hutchinson CV, Barrett DJK, Nitka A, Raynes K. Action video game training reduces the Simon effect. Psychon B Rev. 2016;23:587–92.

Powers KL, Brooks PJ, Aldrich NJ, Palladino MA, Alfieri L. Effects of video-game play on information processing: a meta-analytic investigation. Psychon Bull Rev. 2013;20:1055–79.

Colzato LS, van den Wildenberg WP, Zmigrod S, Hommel B. Action video gaming and cognitive control: playing first person shooter games is associated with improvement in working memory but not action inhibition. Psychol Res. 2013;77:234–9.

Steenbergen L, Sellaro R, Stock AK, Beste C, Colzato LS. Action video gaming and cognitive control: playing first person shooter games is associated with improved action cascading but not inhibition. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0144364.

Download references

Acknowledgements

SK has been funded by a Heisenberg grant from the German Science Foundation (DFG KU 3322/1-1, SFB 936/C7), the European Union (ERC-2016-StG-Self-Control-677804) and a Fellowship from the Jacobs Foundation (JRF 2016–2018).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Center for Lifespan Psychology, Lentzeallee 94, 14195, Berlin, Germany

Simone Kühn, Katharina Schmalen, Markus Weichenberger & Charlotte Witt

Clinic and Policlinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University Clinic Hamburg-Eppendorf, Martinistraße 52, 20246, Hamburg, Germany

Simone Kühn, Dimitrij Tycho Kugler & Jürgen Gallinat

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Simone Kühn .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary material, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Kühn, S., Kugler, D., Schmalen, K. et al. Does playing violent video games cause aggression? A longitudinal intervention study. Mol Psychiatry 24 , 1220–1234 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0031-7

Download citation

Received : 19 August 2017

Revised : 03 January 2018

Accepted : 15 January 2018

Published : 13 March 2018

Issue Date : August 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0031-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

The effect of competitive context in nonviolent video games on aggression: the mediating role of frustration and the moderating role of gender.

- Jinqian Liao

- Yanling Liu

Current Psychology (2024)

Exposure to hate speech deteriorates neurocognitive mechanisms of the ability to understand others’ pain

- Agnieszka Pluta

- Joanna Mazurek

- Michał Bilewicz

Scientific Reports (2023)

The effects of violent video games on reactive-proactive aggression and cyberbullying

- Yunus Emre Dönmez

Current Psychology (2023)

Machen Computerspiele aggressiv?

- Jan Dieris-Hirche

Die Psychotherapie (2023)

Systematic Review of Gaming and Neuropsychological Assessment of Social Cognition

- Elodie Hurel

- Marie Grall-Bronnec

- Gaëlle Challet-Bouju

Neuropsychology Review (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

The relation of violent video games to adolescent aggression: an examination of moderated mediation effect.

- 1 Research Institute of Moral Education, College of Psychology, Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing, China

- 2 The Lab of Mental Health and Social Adaptation, Faculty of Psychology, Research Center for Mental Health Education, Southwest University, Chongqing, China

To assess the moderated mediation effect of normative beliefs about aggression and family environment on exposure to violent video games and adolescent aggression, the subjects self-reported their exposure to violent video games, family environment, normative beliefs about aggression, and aggressive behavior. The results showed that there was a significant positive correlation between exposure to violent video games and adolescent aggression; normative beliefs about aggression had a mediation effect on exposure to violent video games and adolescent aggression, while family environment moderated the first part of the mediation process. For individuals with a good family environment, exposure to violent video games had only a direct effect on aggression; however, for those with poor family environment, it had both direct and indirect effects mediated by normative beliefs about aggression. This moderated mediation model includes some notions of General Aggression Model (GAM) and Catalyst Model (CM), which helps shed light on the complex mechanism of violent video games influencing adolescent aggression.

Introduction

Violent video games and aggression.

The relationship between violent video games and adolescent aggression has become a hot issue in psychological research ( Wiegman and Schie, 1998 ; Anderson and Bushman, 2001 ; Anderson et al., 2010 ; Ferguson et al., 2012 ; Greitemeyer, 2014 ; Yang et al., 2014 ; Boxer et al., 2015 ). Based on the General Aggression Model (GAM), Anderson et al. suggested that violent video games constitute an antecedent variable of aggressive behavior, i.e., the degree of exposure to violent video games directly leads to an increase of aggression ( Anderson and Bushman, 2001 ; Bushman and Anderson, 2002 ; Anderson, 2004 ; Anderson et al., 2004 ). Related longitudinal studies ( Anderson et al., 2008 ), meta-analyses ( Anderson et al., 2010 ; Greitemeyer and Mugge, 2014 ), event-related potential studies ( Bailey et al., 2011 ; Liu et al., 2015 ), and trials about juvenile delinquents ( DeLisi et al., 2013 ) showed that exposure to violent video games significantly predicts adolescent aggression.

Although Anderson et al. insisted on using the GAM to explain the effect of violent video games on aggression, other researchers have proposed alternative points of view. For example, a meta-analysis by Sherry (2001) suggested that violent video games have minor influence on adolescent aggression. Meanwhile, Ferguson (2007) proposed that publication bias (or file drawer effect) may have implications in the effect of violent video games on adolescent aggression. Publication bias means that compared with articles with negative results, those presenting positive results (such as statistical significance) are more likely to be published ( Rosenthal and Rosnow, 1991 ). A meta-analysis by Ferguson (2007) found that after publication bias adjustment, the related studies cannot support the hypothesis that violent video games are highly correlated with aggression. Then, Ferguson et al. proposed a Catalyst Model (CM), which is opposite to the GAM. According to this model, genetic predisposition can lead to an aggressive child temperament and aggressive adult personality. Individuals who have an aggressive temperament or an aggressive personality are more likely to produce violent behavior during times of environmental strain. Environmental factors act as catalysts for violent acts for an individual who have a violence-prone personality. This means that although the environment does not cause violent behavior, but it can moderate the causal influence of biology on violence. The CM model suggested that exposure to violent video games is not an antecedent variable of aggressive behavior, but only acts as a catalyst influencing its form ( Ferguson et al., 2008 ). Much of studies ( Ferguson et al., 2009 , 2012 ; Ferguson, 2013 , 2015 ; Furuya-Kanamori and Doi, 2016 ; Huesmann et al., 2017 ) found that adolescent aggression cannot be predicted by the exposure to violent video games, but it is closely related to antisocial personality traits, peer influence, and family violence.

Anderson and his collaborators ( Groves et al., 2014 ; Kepes et al., 2017 ) suggested there were major methodological shortcomings in the studies of Ferguson et al. and redeclared the validity of their own researches. Some researchers supported Anderson et al. and criticized Ferguson’s view ( Gentile, 2015 ; Rothstein and Bushman, 2015 ). However, Markey (2015) held a neutral position that extreme views should not be taken in the relationship between violent video games and aggression.

In fact, the relation of violent video games to aggression is complicated. Besides the controversy between the above two models about whether there is an influence, other studies explored the role of internal factors such as normative belief about aggression and external factors such as family environment in the relationship between violent video games and aggression.

Normative Beliefs About Aggression, Violence Video Games, and Aggression

Normative beliefs about aggression are one of the most important cognitive factors influencing adolescent aggression; they refer to an assessment of aggression acceptability by an individual ( Huesmann and Guerra, 1997 ). They can be divided into two types: general beliefs and retaliatory beliefs. The former means a general view about aggression, while the latter reflects aggressive beliefs in provocative situations. Normative beliefs about aggression reflect the degree acceptance of aggression, which affects the choice of aggressive behavior.

Studies found that normative beliefs about aggression are directly related to aggression. First, self-reported aggression is significantly correlated to normative beliefs about aggression ( Bailey and Ostrov, 2008 ; Li et al., 2015 ). General normative beliefs about aggression can predict young people’s physical, verbal, and indirect aggression ( Lim and Ang, 2009 ); retaliatory normative beliefs about aggression can anticipate adolescent retaliation behavior after 1 year ( Werner and Hill, 2010 ; Krahe and Busching, 2014 ). There is a longitudinal temporal association of normative beliefs about aggression with aggression ( Krahe and Busching, 2014 ). Normative beliefs about aggression are significantly positively related to online aggressive behavior ( Wright and Li, 2013 ), which is the most important determining factor of adolescent cyberbullying ( Kowalski et al., 2014 ). Teenagers with high normative beliefs about aggression are more likely to become bullies and victims of traditional bullying and cyberbullying ( Burton et al., 2013 ). Finally, normative beliefs about aggression can significantly predict the support and reinforcement of bystanders in offline bullying and cyberbullying ( Machackova and Pfetsch, 2016 ).

According to Bandura’s social cognitive theory ( Bandura, 1989 ), violent video games can initiate adolescents’ observational learning. In this situation, not only can they imitate the aggressive behavior of the model but also their understanding and acceptability about aggression may change. Therefore, normative beliefs about aggression can also be a mediator between violent video games and adolescent aggression ( Duan et al., 2014 ; Anderson et al., 2017 ; Huesmann et al., 2017 ). Studies have shown that the mediating role of normative beliefs about aggression is not influenced by factors such as gender, prior aggression, and parental monitoring ( Gentile et al., 2014 ).

Family Environment, Violence Video Games, and Aggression

Family violence, parenting style, and other family factors have major effects on adolescent aggression. On the one hand, family environment can influence directly on aggression by shaping adolescents’ cognition and setting up behavioral models. Many studies have found that family violence and other negative factors are positively related to adolescent aggression ( Ferguson et al., 2009 , 2012 ; Ferguson, 2013 ), while active family environment can reduce the aggressive behavior ( Batanova and Loukas, 2014 ).

On the other hand, family environment can act on adolescent aggression together with other factors, such as exposure to violent video games. Analysis of the interaction between family conflict and media violence (including violence on TV and in video games) to adolescent aggression showed that teenagers living in higher conflict families with more media violence exposure show more aggressive behavior ( Fikkers et al., 2013 ). Parental monitoring is significantly correlated with reduced media violence exposure and a reduction in aggressive behavior 6 months later ( Gentile et al., 2014 ). Parental mediation can moderate the relationship between media violence exposure and normative beliefs about aggression, i.e., for children with less parental mediation, predictability of violent media exposure on normative beliefs about aggression is stronger ( Linder and Werner, 2012 ). Parental mediation is closely linked to decreased aggression caused by violent media ( Nathanson, 1999 ; Rasmussen, 2014 ; Padilla-Walker et al., 2016 ). Further studies have shown that the autonomy-supportive restrictive mediation of parents is related to a reduction in current aggressive behavior by decreasing media violence exposure; conversely, inconsistent restrictive mediation is associated with an increase of current aggressive behavior by enhancing media violence exposure ( Fikkers et al., 2017 ).

The Current Study

Despite GAM and CM hold opposite views on the relationship between violent video games and aggression, both of the two models imply the same idea that aggression cannot be separated from internal and external factors. While emphasizing on negative effects of violent video games on adolescents’ behavior, the GAM uses internal factors to explain the influencing mechanism, including aggressive beliefs, aggressive behavior scripts, and aggressive personality ( Bushman and Anderson, 2002 ; Anderson and Carnagey, 2014 ). Although the CM considers that there is no significant relation between violent video games and aggression, it also acknowledges the role of external factors such as violent video games and family violence. Thus, these two models seem to be contradictory, but in fact, they reveal the mechanism of aggression from different points of view. It will be more helpful to explore the effect of violent video games on aggression from the perspective of combination of internal and external factors.

Although previous studies have investigated the roles of normative beliefs about aggression and family factors in the relationship between violent video games and adolescent aggression separately, the combined effect of these two factors remains unstudied. The purpose of this study was to analyze the combined effect of normative beliefs about aggression and family environment. This can not only confirm the effects of violent video games on adolescent aggression further but also can clarify the influencing mechanism from the integration of GAM and CM to a certain extent. Based on the above, the following three hypotheses were proposed:

Hypothesis 1: There is a significant positive correlation between exposure to violent video games and adolescent aggression.

Hypothesis 2: Normative beliefs about aggression are the mediator of exposure to violent video games and adolescent aggression.

Hypothesis 3: The family environment can moderate the mediation effects of normative beliefs about aggression in exposure to violent video games and adolescent aggression; exposure to violent video games, family environment, normative beliefs about aggression, and aggression constitute a moderated mediation model.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

All subjects gave informed written consent for participation in this investigation, and their parents signed parental written informed consent. The study was reviewed and approved by the Professor Committee of School of Psychology, Nanjing Normal University, which is the committee responsible for providing ethics approvals. A total of 648 Chinese middle school students participated in this study, including 339 boys and 309 girls; 419 students were from cities and towns, and 229 from the countryside. There were 277 and 371 junior and high school students, respectively. Ages ranged from 12 to 19 years, averaging 14.73 ( SD = 1.60).

Video Game Questionnaire (VGQ)

The Video Game Questionnaire ( Anderson and Dill, 2000) required participants to list their favorite five video games and assess their use frequencies, the degree of violent content, and the degree of violent images on a 7-point scale (1, participants seldom play video games, with no violent content or image; 7, participants often play video games with many violent contents and images). Methods for calculating the score of exposure to violent video games: (score of violent content in the game + score of violent images in the game) × use frequency/5. Chen et al. (2012) found that the Chinese version of this questionnaire had high internal consistency reliability and good content validity. The Chinese version was used in this study, and the Cronbach’s α coefficient of the questionnaire was 0.88.

Aggression Questionnaire (AQ)

There were 29 items in AQ ( Buss and Perry, 1992 ), including four dimensions: physical aggression, verbal aggression, anger, and hostility. The scale used 5-point scoring criteria (1, very incongruent with my features; 5, very congruent with my features). Scores for each item were added to obtain the dimension score, and dimension scores were summed to obtain the total score. The Chinese version of AQ had good internal consistency reliability and construct validity ( Ying and Dai, 2008 ). In this study, the Chinese version was used and its Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.83.

Family Environment Scale (FES)

The FES ( Moos, 1990 ) includes 90 true-false questions and is divided into 10 subscales, including cohesion, expressiveness, conflict, independence, achievement-orientation, intellectual-cultural orientation, active-recreational orientation, moral-religious emphasis, organization, and control. The Chinese version of FES was revised by Fei et al. (1991) and used in this study. Three subscales closely related to aggression were selected, including cohesion, conflict, and moral-religious emphasis, with 27 items in total. The family environment score was the sum of scores of these three subscales (the conflict subscale was first inverted). The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the questionnaire was 0.75.

Normative Beliefs About Aggression Scale (NOBAGS)

There are 20 items in the NOBAGS ( Huesmann and Guerra, 1997 ), which includes retaliation (12 items) and general (8 items) aggression belief. A 4-point Likert scale is used (1, absolutely wrong; 4, absolutely right). The subjects were asked to assess the accuracy of the behavior described in each item. High score means high level of normative beliefs about aggression. The revised Chinese version of NOBAGS consists of two factors: retaliation (nine items) and general (six items) aggression belief. Its internal consistency coefficient and test-retest reliability are 0.81 and 0.79. Confirmative factor analysis showed that this version has good construct validity: χ 2 = 280.09, df = 89, χ 2 / df = 3.15, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.04, NFI = 0.95, NNFI = 0.96, and CFI = 0.96 ( Shao and Wang, 2017 ). In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient of the Chinese version was 0.88.

Group testing was performed in randomly selected classes of six middle schools. All subjects completed the above four questionnaires.

Data Analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics 22 was used to analysis the correlations among study variables, the mediating effect of normative beliefs about aggression on the relationship between exposure to violent video games and aggression, and the moderating role of family environment in the relationship between exposure to violent video games and normative beliefs about aggression. In order to validate the moderated mediation model, Mplus 7 was also used.

Correlation Analysis Among Study Variables

In this study, self-reported questionnaires were used to collect data, and results might be influenced by common method bias. Therefore, the Harman’s single-factor test was used to assess common method bias before data analysis. The results showed that eigenvalues of 34 unrotated factors were greater than 1, and the amount of variation explained by the first factor was 10.01%, which is much less than 40% of the critical value. Accordingly, common method bias was not significant in this study.

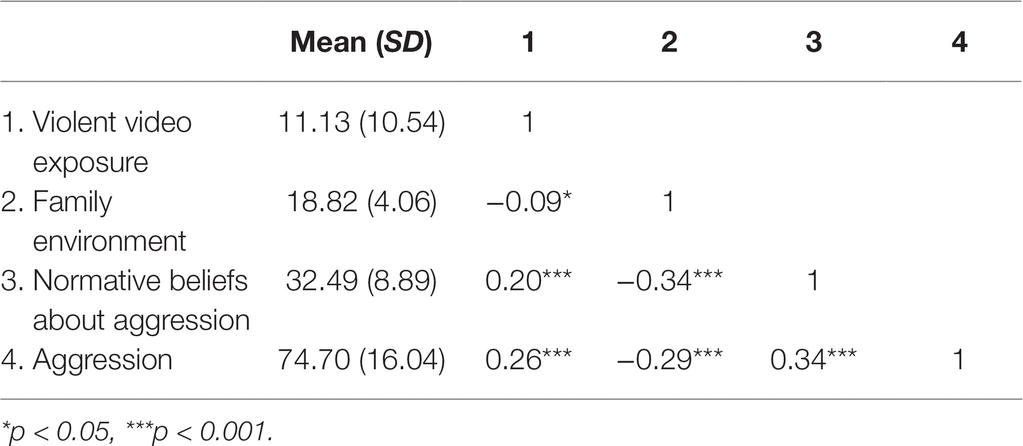

As described in Table 1 , the degree of exposure to violent video games showed significant positive correlations to normative beliefs about aggression and aggression; family environment was negatively correlated to normative beliefs about aggression and aggression; normative beliefs about aggression were significantly and positively related to aggression. The gender difference of exposure to violent video games ( t = 7.93, p < 0.001) and normative beliefs about aggression ( t = 2.74, p < 0.01) were significant, which boys scored significantly higher than girls.

Table 1 . Means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlations among study variables.

Mediating Effect Analysis

To examine the mediation effect of normative beliefs about aggression on the relationship between exposure to violent video games and aggression, gender factor was controlled firstly. Stepwise regression analysis showed that the regression of aggression to violent video games ( c = 0.28, t = 6.96, p < 0.001), the regression of normative beliefs about aggression to violent video games ( a = 0.19, t = 4.69, p < 0.001), and the regression of aggression to violent video games ( c ′ = 0.22, t = 5.69, p < 0.001) and normative beliefs about aggression ( b = 0.31, t = 8.25, p < 0.001) were all significant. Thus, normative beliefs about aggression played a partial mediating role in exposure to violent video games and aggression. The mediation effect value was 0.06, accounting for 21.43% (0.06/0.28) of the total effect.

Moderated Mediation Effect Analysis

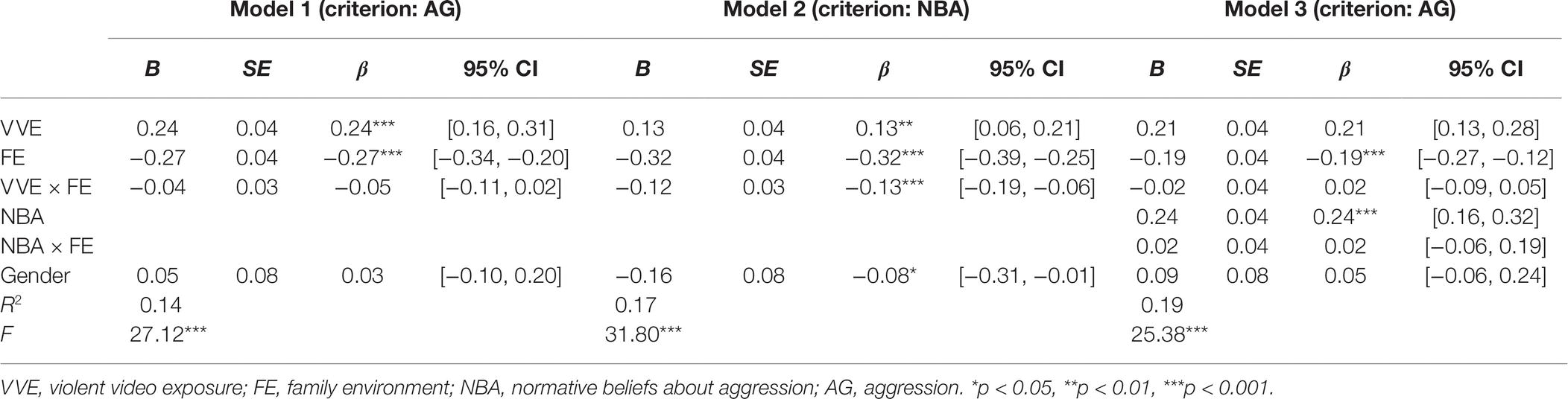

After standardizing scores of exposure to violent videogames, normative beliefs about aggression, family environment, and aggression, two interaction terms were calculated, including family environment × exposure to violent video games and family environment × normative beliefs about aggression. Regression analysis was carried out after controlling gender factor ( Table 2 ).

Table 2 . Moderated mediation effect analysis of the relationship between violent video exposure and aggression.

In the first step, a simple moderated model (Model 1) between exposure to violent video games and aggression was established. The result showed that exposure to violent video games had a significant effect on aggression ( c 1 = 0.24, t = 6.13, p < 0.001), while the effect of family environment × exposure to violent video games on aggression was not significant ( c 3 = 0.05, t = −1.31, p = 0.19), indicating that the relationship between exposure to violent video games and aggression was not moderated by family environment.

Next, a moderated model (Model 2) between exposure to violent video games and normative beliefs about aggression was established. The results showed that exposure to violent video games had a significant effect on normative beliefs about aggression ( a 1 = 0.13, t = 3.42, p < 0.001), and the effect of family environment × exposure to violent video games on normative beliefs about aggression was significant ( a 3 = −0.13, t = −3.63, p < 0.01).

In the third step, a moderated mediation model (Model 3) between exposure to violent video games and aggression was established. As shown in Table 2 , the effect of normative beliefs about aggression on aggression was significant ( b 1 = 0.24, t = 6.15, p < 0.001), and the effect of family environment × exposure to violent video games on normative beliefs about aggression was not significant ( b 2 = 0.02, t = 0.40, p = 0.69). Because both a 3 and b 1 were significant, exposure to violent video games, family environment, normative beliefs about aggression, and aggression constituted a moderated mediation model. Normative beliefs about aggression played a mediating role between exposure to violent video games and aggression, while family environment was a moderator between exposure to violent video games and normative beliefs about aggression. Mplus analysis proved that the moderated mediation model had good model fitting (χ 2 / df = 1.54, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.03, and SRMR = 0.01).

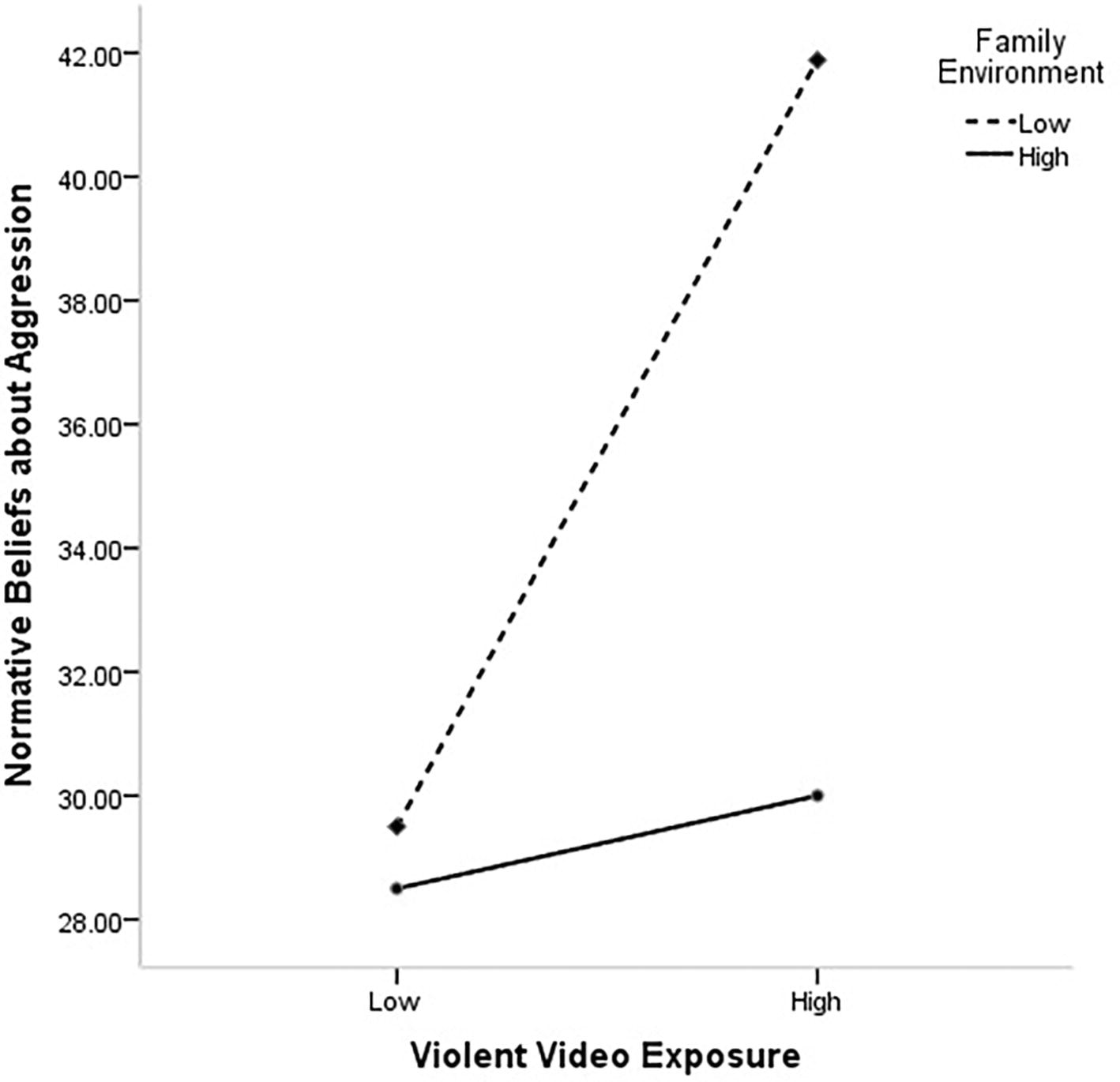

To further analyze the moderating effect of the family environment and exposure to violent video games on normative beliefs about aggression, the family environment was divided into the high and low groups, according to the principle of standard deviation, and a simple slope test was performed ( Figure 1 ). The results found that for individuals with high score of family environment, prediction of exposure to violent video games to normative beliefs about aggression was not significant ( b = 0.08, SE = 0.08, p = 0.37). For individuals with low score of family environment, exposure to violent video games could significantly predict normative beliefs about aggression ( b = 0.34, SE = 0.09, p < 0.001). Based on the overall findings, individuals with high scores of family environment showed a nonsignificant mediating effect of normative beliefs about aggression on the relation of exposure to violent video games and aggression; however, for individuals with low scores of family environment, normative beliefs about aggression played a partial mediating role in the effect of exposure to violent video games on aggression.

Figure 1 . The moderating effect of the family environment on the relationship between violent video game exposure and normative beliefs about aggression.

Main Findings and Implications

This study found a significantly positive correlation between exposure to violent video games and adolescent aggression, corroborating existing studies ( Anderson, 2004 ; Anderson et al., 2010 ; DeLisi et al., 2013 ; Greitemeyer and Mugge, 2014 ). Anderson et al. (2017) assessed teenagers in Australia, China, Germany, the United States, and other three countries and found that exposure to violent media, including television, movies, and video games, is positively related to adolescent aggression, demonstrating cross-cultural consistency; 8% of variance in aggression could be independently explained by exposure to violent media. In this study, after controlling for gender and family environment, R 2 for exposure to violent video games in predicting adolescent aggression was 0.05, indicating that 5% of variation in adolescent aggression could be explained by exposure to violent media. These consistent findings confirm the effect of exposure to violent video games on adolescent aggression and can be explained by the GAM. According to the GAM ( Bushman and Anderson, 2002 ; Anderson and Carnagey, 2014 ), violent video games can make teenagers acquire, repeat, and reinforce aggression-related knowledge structures, including aggressive beliefs and attitude, aggressive perceptual schemata, aggressive expectation schemata, aggressive behavior scripts, and aggression desensitization. Therefore, aggressive personality is promoted, increasing the possibility of aggressive behavior. The Hypothesis 1 of this study was validated and provided evidence for the GAM.

As shown above, normative beliefs about aggression had a partial mediation effect on the relationship between exposure to violent video games and aggression. Exposure to violent video games, on the one hand, can predict adolescent aggression directly; on the other hand, it had an indirect effect on adolescent aggression via normative beliefs about aggression. According to the above results, when exposure to violent video games changes by 1 standard deviation, adolescent aggression varies by 0.28 standard deviation, with 0.22 standard deviation being a direct effect of exposure to violent video games on adolescent aggression and 0.06 standard deviation representing the effect through normative beliefs about aggression. Too much violence in video games makes it easy for individuals to become accustomed to violence and emotionally apathetic towards the harmful consequences of violence. Moreover, it can make individuals accept the idea that violence is a good way of problem solving, leading to an increase in normative beliefs about aggression; under certain situational cues, it is more likely to become violent or aggressive. This conclusion is supported by other studies ( Gentile et al., 2014 ; Anderson et al., 2017 ; Huesmann et al., 2017 ). Like Hypothesis 1, Hypothesis 2 was validated the GAM.

One of the main findings of this study was the validation of Hypothesis 3: a moderated mediation model was constructed involving exposure to violent video games, family environment, normative beliefs about aggression, and aggression. Family environment moderated the first half of the mediation process of violent video games, normative beliefs about aggression, and aggression. In this study, family environment encompassed three factors, including (1) cohesion reflecting the degree of mutual commitment, assistance, and support among family members; (2) conflict reflecting the extent of anger, aggression, and conflict among family members; and (3) moral-religious emphasis reflecting the degree of emphasis on ethics, religion, and values. Individuals with high scores of family environment often help each other; seldom show anger, attack, and contradiction openly; and pay more attention to morality and values. These positive aspects would help them understand violence in video games from the right perspective, reduce recognition and acceptance of violence or aggression, and diminish the effect of violent video games on normative beliefs about aggression. Hence, exposure to violent video games could not predict normative beliefs about aggression of these individuals. By contrast, individuals with low scores of family environment are less likely to help each other; they often openly show anger, attack, and contradiction and do not pay much attention to morality and values. These negative aspects would not decrease but increase their acceptance of violence and aggression. For these individuals, because of the lack of mitigation mechanisms, exposure to violent video games could predict normative beliefs about aggression significantly.